Researching Potential Sites

Aerial photography – a valuable research tool.

To find the most promising and, hopefully, most productive sites research is necessary. After you have located potentially good sites the next step, of course, is to gain permission to search them.

Naturally, the fact that you have intensively researched an interesting looking area does not mean to say that when you approach the landowner you will gain search permission. However, if you take along the results of your research when you knock on the door it can help weigh the odds in your favour. Even if you should receive a rejection your hours or days of research will be by no means wasted. The exercise will have increased your knowledge of local history, and – from the experience gained – will make the next research project that much easier.

Much of the documentary site research that you will conduct is the paper equivalent of fieldwalking. Where appropriate in this chapter, therefore, helpful hints and links to fieldwalking are included to expand the topic. The majority of these additions are based on our own experiences. There are a number of sources of invaluable information to assist you in finding promising areas worth searching. The following suggestions are the recognised areas of research that have been adopted by The Pastfinders (of which Dave and I are members). We have found them all highly effective.

Google Earth

Since the First Edition of this guide was written another research tool has made its presence greatly felt. This is Google Earth, which offers total aerial accessibility to sites. There is also a small clock icon that allows you to examine previous photographs of your sites taken in the last few years. These are often in different seasons and with different crops, so are very useful.

An example of this is part of a site we have been detecting on for years. When examined on Google Earth initially, it didn’t seem too exciting. However, looking at the 2005 period it was a different story altogether for clearly visible was a vast sprawling Iron Age settlement. Later searching uncovered numerous Celtic and Roman coins. It is worth remembering that even with Google Earth not all sites may reveal themselves so dramatically. For example try having a look at known villa or settlement sites; they might just appear as darker patches of soil or crops often offering hardly anything visible – so it’s worth looking around for similar markings. We have found over 20 previously unknown settlements by using Google Earth.

In some parts of the country using Google Earth you can go right back to 1945, although these images are in black and white and the definition is not so clear as the more modern ones. However, the 1945 photos are useful for examining development (both urban and rural) and for finding buildings no longer in existence. Look for unusually shaped woodland areas they may well be hiding a moated medieval settlement. Look for old trackways and particularly the points where they cross over. Finding tracks that exist – or crop marks pinpointing those no longer used – could they lead to an unseen area of settlement. Of course, like any research methods, there are pitfalls that could catch out the beginner. Some examples of these are:-

- A group of circular markings in a field looking like Bronze Age barrows or earlier ring ditches. In fact they are the site of a Second World War searchlight battery.

- Where gamekeepers position their rearing pens can leave marks that look very much like Roman villas.

- Where manure piles have been left for years and then moved, or where farmers spill large amounts of fertiliser, can both create false markings.

- Tracks where deer or other large animals cross cropped fields can also be misleading.

- Pylons and telegraph poles often encourage rough grassy growth beneath them. When viewed from the air they can look extremely curious – as can their shadows.

- Stubble fields after harvest are also covered in a myriad of vehicle tracks, which from high altitude can appear as settlement type markings.

However, do not worry if you do make a mistake. Metal detecting will soon show you whether your conclusions were correct or not. Also, who knows what you may find on the site anyway? The potential for this tool is limitless. Despite this modern approach and facility all the factors listed below are still extremely relevant, especially when one considers not everyone has access to a PC. Once you have located an area of interest it’s often a good idea to print off a copy so that you can show a landowner specifically where you are interested in.

Modern Ordnance Survey & Older Maps

Maps such as these can be used to examine field shapes and road patterns, and many historical sites are shown on them as well. A lane or track, for example, which has a semi-circular or basically circular route, may indicate an enclosed settlement that the road or track went around. Roman roads will deviate from straight alignment normally only as topographical requirements dictate, but we once discovered a former Roman temple opposite a small un-required deviation. In all probability the deviation may not have been temple linked, but it shows how looking for the slightly out of the ordinary features can bring rewards.

Other places worthy of investigation are crossings of ancient trackways or marked Roman roads. The most ideal modern maps for this purpose are the Ordnance Survey “Explorer” and “Pathfinder” ranges, both at a scale of 1:25000 (2.5 inches to the mile).

Please note that the green coloured cover Pathfinder range of maps is unfortunately no longer published, but copies are still worth obtaining if you encounter them second hand.

Many moated sites, coin hoard find spots, and old windmills are also marked on such maps. The surrounding areas to these should reveal finds. Look for isolated churches that may indicate a village abandoned due to the plague. Landowners re-designing their estates or areas around these churches could reveal traces of the original settlement. Small clusters of isolated ponds could be the carp ponds from a long-vanished monastic building or early manor house.

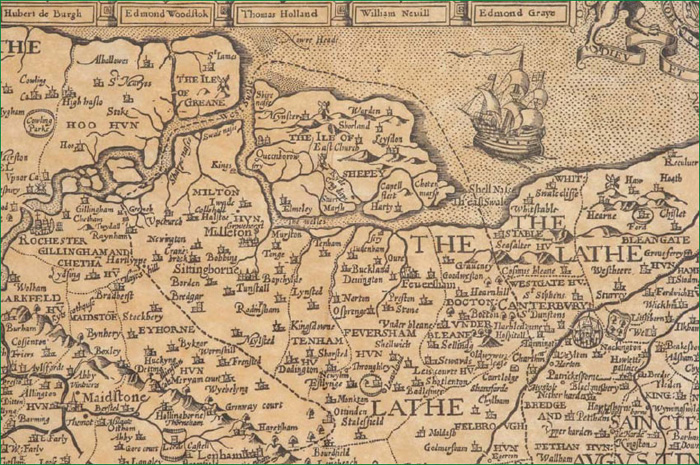

Part of John Speed’s Kent Map (with kind permission: The Old Map Company).

Isolated large trees, copses and field corners near farms and villages are also easily spotted on such maps. Such places are where picnickers and farm labourers of the past may have taken their work breaks. Also look for rivers and spring sites that could have supplied water to a nearby settlement.

A number of websites are available that allow you to look at old maps of your area. These can be invaluable for locating lost footpaths, and many show windmill sites etc that do not always feature on more modern versions.

Tithe maps are an excellent source to study field shapes prior to Enclosure actions of the last 400 years. The majority of these often tiny individually held tithe plots have long since disappeared.

Study the contour lines on maps to locate rises in land; in flattish countryside hills and slopes have attracted people for many millennia.

Landowners themselves can often be an invaluable source of old maps. Many of these were drafted specifically for the estate in question and can show the area in astounding detail.

Libraries, Museums, County Halls, Churches & Public Records Offices

Many libraries stock a good selection of general, and more local books and records; some even stock old aerial photographs. These are mostly 1940s and 50s RAF exposures, but some sources also have Luftwaffe photographs as the German air force extensively photographed the UK during reconnaissance in the early years of the Second World War.

Aerial photographs are as good as maps, with the added bonus that they can show you crop markings and other potential sites not usually detailed on maps. However, one should always use caution, as there are quite a number of pitfalls in site interpretation from aerial photographs (see also Google Earth). One example we have encountered is Second World War ploughed out bomb craters and search light battery sites that can look like Bronze Age and earlier ring ditches. But if you are interested in searching for Second World War artefacts, then perhaps it’s just as appropriate to consider the reverse.

Yet another factor that can easily fool the inexperienced and experienced alike is a geological fault that can occur on some chalk hills. This is where soil slips from the peak downwards; in severe cases this can form a band of rings around the hilltop. Natural occurrences such as these are easily mistaken for ditches associated with Bronze Age or other settlements.

Regarding aerial photographs there are again a number of very good web sites that cover most of the UK, and the potential of these, as said previously, is phenomenal. Your local museum will also be a rich source of information. Many museums now have excellent relationships with detectorists, and quite a few stock an excellent display of published books and pamphlets on local history. Most museum staff will only be too pleased to put you in contact with county archaeological departments, Finds Liaison Officers, and local historians. Some museums also stock records of archaeological digs and investigations going back decades, many beyond living memory.

Public Records are a rich source of research information and hold a wide variety of records that may be useful to you, such as Tithe Maps.

Churches may be the centre of a local magazine publication that contains many interesting facts and details about villages etc. Some churches will also house the parish records, which can be viewed by appointment. Parish records for the years 1939-50 can be very rewarding to look at. The principle reason for this is that huge areas of pasture and virtually any available plot of land were put to the plough or the spade to increase this country’s food production. Consequently more artefacts, coin hoards and sites of historical interest were uncovered than ever before, and many were reported in the local parish records.

County Halls can also sometimes be good sources of information. One we know of houses a comprehensive record of all known crop markings in that county. All of these sources are extremely good for research and gathering information; how you use it will undoubtedly be reflected in your future finds rate.

Local Newspapers

These can be very good for articles on local archaeological discoveries and more often than not individual metal detector finds. If you are new to the hobby the article may include a contact name or group who you could approach.

Local newspapers are as always a good way of getting to know what’s going on in your area. Such local newspapers also carry articles and notices in relation to new developments such as roadways and housing estates. Both sites could be worth obtaining permission to search on. Should these new developments be in areas of historic interest, find out if there is any rescue work going on. Perhaps the group doing this would welcome somebody to help metal detect the spoil. One such notice relating to a new bypass in our district led us to gain permission to briefly search the cuttings made along its route. Most of these were dug into chalk, so any interesting soil disturbances showed up clearly. When we arrived we noticed a series of circular clay patches full of round pebbles. Numerous worked flints and cores were scattered about and inside these circular patches. We later discussed the finds and concluded that most likely the new road cutting had truncated some prehistoric flint mines. Later when glaciation occurred after their excavation, these holes became filled with clays and thousands of pebbles as the huge ice mass ground and slid its way over them.

Talking To Local People

It’s a very good idea to talk to local people about your new hobby. For instance, somebody might remember their grandfather ploughing up some coins before the war. Developing a network of people, who are aware of your interests, will help your research. Public houses can be very good nodal points for meeting people and asking who owns such and such bit of land etc.

If you are lucky people will start to contact you, telling you when a certain field is ploughed, or that Mr. Smith has a collection of coins from his garden etc. Agricultural workers in many cases will be aware of features that are of interest to you, due to the nature of their work.

Is there a local historian who might be able to assist you? You might even hear of other local detectorists, who – if they care about the hobby – will I am sure help you with the early stages of research. (Although don’t expect that they will always tell you where all their wonderful Roman denarii came from; sites like these you will have to find for yourself.)

Finally, if these people are helping you and they are in turn interested in history etc, do inform them of what you are finding. Your finds rate in a certain area may be directly connected to a bit of information given to you. We share knowledge related to this hobby with a wide variety of people and organisations including schools, other detecting groups, history societies and museums. In turn, a reciprocal flow of information comes back.

Fieldwalking

Fieldwalking is the final part of site research (dealt with in greater detail in Chapter 6). There are no hard and fast rules to the order in which you conduct site research and permission seeking. When you have conducted all your documentary research, it could be that the areas you are interested in have rights of way across them. If this is the case you could have a look at a site before asking permission. Who knows, you may even spot a scatter of pottery or oyster shells. Even better, you might meet the landowner or a farm worker and outline your interests to them.

It is important to remember that despite land having public rights of way across it, until you have secured the landowner’s permission you must not use your detector to search.