Fieldwalking & What To Look For

As mentioned in Chapter 4, perhaps you may have already taken the opportunity to conduct some limited fieldwalking (along public rights of way such as footpaths, bridleways etc) prior to asking search permission from the landowner concerned. The hints and suggestions in this chapter are relevant to all types of fieldwalking, but perhaps best suited to that done once search permission has been obtained. In such circumstances – crop conditions permitting – you are unrestricted and can wander at will.

However, when you fieldwalk, what exactly are you looking for? That could be dependent upon your particular interests, and could extend from the Bronze Age to hunting Second World War relics.

The term “fieldwalking” largely applies to agricultural land subject to ploughing, but at the same time can take in a wide variety of other terrains such as chalk pits, riverbanks, ditches, and wooded areas. Woodlands, for example, cover many medieval moated sites, and depending on the season when your search takes place many factors dealt with below could be applicable. If you discover a site of interest, and there is an adjacent river, check the exposed banks; often stones, pottery and other clues can be evident.

A small river we checked recently had occupation evidence clearly visible in its banks as well as huge worked stones lying on its bed. This certainly stimulated our interest in this newly fieldwalked area, and resulted in some very interesting finds being made.

While on the subject of rivers, study the banks for erosion on both sides as this might indicate an ancient crossing place. Often there can be traces of the trackways in the same areas, particularly if the river course is surrounded by un-ploughed ancient meadowland.

However, a field surface that has been deep ploughed, harrowed or rolled flat, will perhaps reveal the most to the keen fieldwalker, hopefully revealing the potential of metallic finds that may be associated with your discoveries.

Such surfaces may evidence pottery shards, stone scatters, odd coins, different soil colouration, tile, oyster shells and a whole host of indicators to past ancient activities.

This chapter will therefore deal for the most part with ploughed fields, but will also cover other pertinent details such as animal activity etc that we think may be helpful. Basically, when fieldwalking it can be helpful to look for features that are noticeably out of the ordinary context of your search area. For a simple example, in dark soiled fenland fields, which can be virtually stone-less, a large scatter of stones would be unusual and could indicate a building from some period. A large scatter of flints on the top of a Hertfordshire chalk slope is almost always a geological occurrence. A patch of dark soil in a light coloured soil field, or a patch of light soil in a dark coloured field, would both be of interest.

Fig. 1. A stone scatter such as this may indicate a Roman building.

However, never be too dismissive or too confident; many a Roman villa has probably been missed over the years by over-confidence, and not bothering to closely check something out.

We have found that for searching large fields a powerful pair of binoculars can be of great assistance.

If you are lucky, perhaps your earlier research has revealed a series of rectangular crop markings and you already have a firm objective to set out and look at these. There follows below a list of factors that we would pay attention to, or most certainly be looking at, to see if we could establish such a presence.

Fieldwalking is a marvellous section of research and can be extremely fulfilling. As you become more and more experienced you will find that you automatically make calculations that can make you smile as they lead you to find such a thing as a Roman farmstead. The presence of this may have been quite obvious to you, but never grow too confident for in your enthusiasm to reach this site you may have walked too fast and missed a smaller ancient farm right beneath your feet. Take your time and you should hopefully be rewarded with finds.

Experience can tell here, but it is often the metal detector that determines the final classification. For example, you have been out fieldwalking and in one area have found some grey coloured pottery fragments, one or two glossy red decorated shards, several oysters and some tiles, and a very lucky eyes-only find of a hammered coin.

This means that the site you have found could be:

- A medieval site with some traces of earlier Roman habitation.

- A Roman site with a casual hammered coin loss as the building materials were robbed out at a later stage.

- A midden showing Roman, Saxon and medieval pottery.

- A place where somebody has dumped soil from another district.

Perhaps a later metal detector search results in the recovery of over 50 late 3rd and 4th century coins, spread over this area and further afield. Here the metal detector has assisted in identification of the fieldwalking-discovered site, as to being a late Roman settlement.

Fieldwalking on its own is never easy or even conclusive, but it is always very enjoyable.

If you are fieldwalking remember to close any gates that you have opened, be aware of any livestock present, and obey any legal signs displayed. You should also take every precaution not to disturb breeding birds or wild life. As a basic rule any wild bird that ventures unnaturally close to you means that in all probability you are very near its eggs or newly hatched young. So walk carefully away. Fortunately, most fieldwalking occurs well after most of the breeding season has been completed. The following factors relating to settlement/habitation sites do not normally occur on their own, although it is likely, in some cases, that you will notice only one initially.

As you become more experienced, when you investigate a stone scatter related to a settlement etc, you will notice tiles, pottery and shells as well. Gaining fieldwalking experience will illustrate to you just how interrelated some of the features listed below can be.

Hopefully, these categories will help you to analyse just what it is you are looking at, as well as gaining the knowledge to dismiss the many misleading features and their causes. While it does not aim to provide all the answers, it is hoped it will stimulate your own path of research.

Stone & Tile Scatters

Concentrated stone and/or tile scatters can be a very good indication that the area you are field-walking has seen past human activity. It is a high possibility that almost every field you check will have one or two visible fragments of tile here and there. Some of these result from the medieval/Tudor and later habit of spreading tile over fields to assist with drainage. Hopefully, after closer examination they will be discovered in association with some of the other factors outlined below. Some stone scatters can be visible for many miles dependent on the type and colour of the soil they are present on. Stone scatters can represent debris from medieval churches, Roman villas, and a whole host of other buildings and reasons.

Fig. 2. Roof and floor tiles can be found around an ancient site in large numbers.

More recent buildings tend to be associated with brick and slate or tile scatters, and glazed pottery. Sometimes a stone and tile scatter can be related to a Roman building that is some distance away. We know of one example where the building materials from a villa were robbed out. The medieval or later builders deposited these materials by the side of a road. We thought we had a good site but when no Roman coins appeared we were therefore surprised to say the least. Several hundred feet away there was a noticeable dark soil patch with some cobblestones; when detected over this revealed the villa and many of its coins and artefacts.

This relocation and re-use of building materials is also reflected in the fabric of some older churches and walls. Frequently in Norman and later times the local Roman villa site was seen as a cost saving source of building materials. You can often spot Roman tiles and fragments of Saxon gravestone etc re-used in many old church towers. A really spectacular example of this is St. Albans Abbey adjacent to the site of the Roman town of Verulamium; there are literally thousands of Roman tiles visible in its construction. There is therefore a good chance that several stray pieces of Roman tile in a church tower could represent a wealthy Roman villa nearby.

Any isolated scatters of large rounded cobblestones are also of great interest, as they can indicate the ploughed-out floors of ancient dwellings. Scatters of approximately 1 inch cubes of tile are other signs of a possible Roman building site. These tile cubes are called tesserae, and should you find smaller versions made from limestone, fired clay, granite etc, you may just have located a plough damaged mosaic site.

Huge areas of smallish rounded pebbles and gravels are, however, most likely to be glacial deposits. Beware of other geological stone scatters, such as the previously mentioned flint nodules on the crest of chalk slopes; but in all cases, if you are suspicious check it out. World War Two bombs caused large craters when they exploded, which today can still be defined in some instances by variations in soil colour or large stones being present on a field surface. These stones having been brought up from much deeper stratum by the explosion involved.

Despite all the potential pitfalls, however, when you discover your first Roman or medieval building you will notice many of the other facts listed below. One thing is for certain: having acquired the experience you will never forget it. This experience will build and develop; believe us when we say that in years to come somebody will show you something and you will know exactly what it is. Often at that point you will marvel at the fact that just five years ago you wouldn’t have had a clue. You will soon build up an idea of what stones etc are natural to your area, and this in turn will enable you to spot any abnormality all the sooner.

One site was indicated to us by the presence of fractured but worked igneous rock fragments of a type not glacially transported nor naturally occurring in the district. They were, in fact, fragments of Andernach lava used by the Romans for making querns. This triggered a fieldwalk of the surrounding area, whereupon a much dispersed Roman settlement was located. Quite incredibly, a tiny piece of stone had given us yet another Roman site to search.

When fieldwalking on Roman sites it is well worth checking on both sides of any tile fragments you find; it may be a surprise at just how many animal paw and other impressions that are evident. The most amusing example of one of these I have seen, are the tiny feet impressions of a mouse, followed by the paw imprints of a cat!

Scatters Of Pottery Shards

Pottery fragments can be found on a wide variety of settlement sites from those of a Victorian manor house to a Saxon settlement. As a simple general rule, grey brown and black gritty fabrics are old or ancient, while most glazed fragments tend to be medieval to modern. Although some late Roman pottery imported from the Rhineland, and to a smaller extent produced in Britain, was also glazed in this country it is rare to find either. Grey, sandy, gritty pottery fragments tend to be referred to as “grey ware”. It can be extremely difficult to distinguish medieval grey ware from that which is Roman. Therefore you should not definitely identify a site type without taking other factors into consideration.

Fig. 3. Fragments of Roman samian ware pottery.

Just to confuse the issue, some sites have pottery fragments from all ages over their surfaces. In this instance the metal detector will certainly assist in giving an idea of who mainly resided on such sites. Some Victorian bottle dumps have been ploughed out creating huge scatters of pottery often in association with other domestic items such as bones and ash. Apart from modern fragments, which should on the whole be easy to determine, there are also some ancient “exotics” that the inexperienced fieldwalker may accidentally dismiss as being modern. The chief one of these is called samian ware, a bright red glossy fabric often slip or mould decorated. Other Roman types may be black, grey or white with coloured slip decoration equally confusing to the beginner.

Some ancient pottery has crushed shell, calcite or egg fragments in its make up, and these inclusions can be seen as flecks of white within the matrix. Some pale fragments of Roman mortaria have small igneous rock or quartz inclusions, making them appear speckled. These inclusions, known as trituration grits were pressed into the surface before firing to assist with grinding grain.

Other ancient pottery sparkles in the light due to its clay having a high level of mica in it, or having been dusted over with it as a pre-firing preparation. Any dark pottery with wheel or star-shaped circular punch mark decorations is most likely to be Saxon.

Bronze Age pottery, on the whole, is quite rare to find on any surface, as due to its poor firing it can be very delicate. Neolithic pottery too is quite an uncommon find, but can be observed scattered over areas of known flint working.

Pottery fragments in their own right can make up an interesting collection; we have some Roman examples that still have the potter’s finger print and nail marks on them.

Should you find patches of stones, burnt soil, and numerous pottery fragments a good chance is that you may have discovered a ploughed out kiln site. Be on the look out for misshapen and distorted fired fragments called “wasters”; these are classic indications that you are near to a kiln. Once you become reasonably proficient at pottery identification this will become yet another tool for you to use in possible site identification and therefore age.

Finding Freshwater & Marine Shells

Shells, particularly oysters, are always a good indication for areas of settlement. They were regarded as part of the staple diet of the poor from Roman times until relatively recently. If you find shells in an area they may well be the only obvious remaining indication of a midden. Middens are where household and general domestic rubbish has been deposited; sometimes they are near or actually in settlements, at other times they are situated a fair distance away or dispersed widely as a result of manuring. Another source of shell deposits are dried up lakes and meres. However, despite these being natural deposits of shells you should not dismiss them. Such areas have often encouraged adjacent settlement and often extensive fishing and hunting from Neolithic times to when the water was drained etc.

As a discarded oyster ages it becomes paler, with more recent shells being grey brown in col-our. Roman and medieval examples are normally snow white with a slight flakiness to their texture. The good thing about ancient oysters is that being white they show up very clearly against most soil backgrounds, and this is even more the case after rainfall.

Small types of white coloured, flattish snail shells found in soil may well indicate that your search area was a lot wetter in past centuries. Such snail shells can also be evident in the ploughed out ditches of settlements and barrows. Other shells to look out for, particularly inland, are fresh water and marine mussels as well as cockles, clams, periwinkles and limpets. It is said that the Romans introduced the edible snail to this country and, true enough, we have several Roman sites where these still abound. If you have never seen one of these creatures before, you will be surprised at their huge size compared to the garden snail. After this shock spare a thought for the possible Roman site that could well be nearby. Where these creatures have once existed and died off you can find many shells; however, like oysters the really old ancient examples are very pale, some being almost white. Texturally, these snail shells can also become quite flaky when extremely old. Look for evidence of these shells in new road cuttings, or along ancient sunken lane verges.

Fig. 4. Darkened soil may indicate an occupation site.

Areas Of Light & Dark Soil Colouration

As mentioned before, a dark area in a light soiled field, and a light area in a dark soiled field, could both be indicators of some level of soil disturbance or alteration. Sometimes you may experience both together. The most dramatic of these can be where strip lynchets have later been ploughed away. In really defined examples, the whole field can be covered in 5-15 feet thick bands of alternating light and dark soil. Such patches are fairly obvious in their appearance. However, they are not always indicative of human habitation or settlement sites. Only closer examination of their surfaces will reveal this. For example, a recently laid pipeline, or an ancient hedge that has been grubbed out may cause a single dark line in the soil. In the case of the latter, a glance at the tithe map for the area would help in confirming this.

Fig. 5. The top layers in this chalk pit revealed much evidence of Roman occupation.

Landowners who have filled in moated sites on their land have created another example of soil variation. Much of this happened in the 1960s when scheduling was not so defined, and it was undertaken to ease ploughing of a field.

Sometimes the positions of ancient kilns can appear as individual small light and dark patches. On occasion, in association with kilns, you will find areas of burned soil that have been ploughed up. Most soil varieties that have been subjected to extreme heat normally turn brick red to orange, with areas of darker carbonisation. Dependent on what the kiln’s use was, it may be surrounded by a dense mass of pottery fragments or nodules of iron slag. Some grain drying kilns have even been found in association with large amounts of carbonised cereal grains. These burned grain deposits have been at some depth; normally any burned grains found above 2 feet depth originate from the now banned stubble burning days.

Normally, old habitation sites that have richer, darker soils will be associated with more defined darker crop growth than surrounding areas. Some dark patches have also resulted from neglected chalk pits that fill up with topsoil and organic matter. A dark patch surrounded by an outer pale ring normally reveals such disused pits. Another consideration is where a farmer has allowed a manure pile to stand and mature; this can leave a dark patch in the field for many years, due to the leached nutrients.

As always, however, if you have the slightest suspicion about a feature you should in all cases investigate it. The path of an ancient, now-lost river may also appear as a white or dark line in the soil, perhaps associated with shell fragments. Some areas of Cambridgeshire are well known for these features singularly known as a “rodon”, as they are for huge pale areas associated with long dried out meres or lakes.

In many areas of Eastern England during the last part of the 19th century there was a widespread industry based on mining coprolites. These are nodules of fossilised dinosaur droppings and other organic matter high in phosphates. Mined in huge open cast pits, coprolites were extracted for use as fertiliser; these pits can still be seen as crop marks and normally slightly darker than the surrounding soils.

Yet another factor to be aware of associated with signs of habitation are small depressions in fields. In many areas of settlement the residents sunk a well for their fresh water supplies. These are now mostly blocked; however, we have seen several that, after rainfall, have collapsed inwards. One example left a crater 20 feet wide by some 10 feet deep that just appeared overnight. Previously, we had frequently used this as a place to shelter for a cup of tea – so always be cautious of these types of initially small depressions!

Soil Types

Becoming familiar with soil types can also be invaluable. Combine this with your research and you will eventually make knowledgeable decisions about the potential of good search areas. Familiarising yourself with the soil types of your locality should enable you to spot both geological and settlement based variations.

The fertile rich, usually dark valley soils, encourage settlement and have done so for thousands of years. Two principle reasons for this are the high yield in crops and the ease of ploughing. Heavy hill top clays were not usually settled because it is only in the last 200-300 years that machinery has been developed able to cope with ploughing this heavy soil.

However, there are always exceptions to advice and clues and we know of at least three Roman sites situated on heavy clays. This leads us to believe that the farming activities of these sites were conducted some distance away, and to a high degree these were residential and storage areas. In relation to soil types, Ordnance Survey produce a series of maps that show geological distribution over the UK. These are immensely useful; when you have discovered a settlement on a certain soil type you can use these maps to study the extent of that soil variety and may find further settlements. This works particularly well with Roman farmsteads, as these moved around frequently due to the ignorance of soil nutrient exhaustion caused by crop growth.

Fig. 6. A freshly excavated drainage ditch.The dug out soil is ideal for detecting.

Crop Markings & Lumps, Bumps & Ridges On Meadowland

Sites of buildings, round barrows, ditches and other soil disturbances can be particularly in evidence through crop markings during long hot dry summers. Varying climatic conditions can make crop marks appear in fields, where there has been no appearance before. A few years ago, on land we were very familiar with, a whole series of Neolithic ringed enclosures just appeared, attracting the local archaeological group to trial trench them.

Aerial photographs are a good way to find similar cereal crop or grassland markings. However, this does necessarily mean that they were visible at the time the photograph was taken.

Sometimes, if you are up on high ground, you can gain a good view across low lying potential fields; using binoculars, as stated before, is highly recommended for this situation.

Dependent on whether there are walls or ditches beneath, in crops such markings will show up lighter or darker with different levels of crop growth. Sometimes you will be lucky and see clear markings. However, if using some of the photographic Web site techniques of looking at areas of known settlements or villas etc, you will be quite surprised at some that show up only as large darker areas of crop growth, with no clearly defined markings at all. This factor alone will assist you in discovering other sites.

There are several reasons why temporary false crop marks may also appear, such as where the farmer has suffered a spillage of grain; this will be defined by a much denser than normal crop growth. Equally, where a spillage of fertiliser has occurred this will have the same effect.

With experience, though, you should be fairly capable of discounting these in terms of size and shape. Remember also that animal pens and enclosures – used up until recently but then demolished – can also result in superb crop/grassland markings that are of little significance to the detectorist. On some large shooting estates the gamekeepers erect huge pheasant breeding pens. These are often relocated, but the scars left on grassland etc where they were positioned can look very much like a large Roman courtyard villa, particularly when viewed on an aerial photograph.

If you are walking in meadowland and notice that the field surface undulates in a series of lines, these are almost certainly strip lynchets. These are caused by ancient ploughing techniques building up soil lines. In this country they most likely date to the medieval period, but some Roman examples are known. These may also be known as “ridge and furrow”. As the sun sets in the late afternoon some fields can have a striped appearance, where the linear depressions fall into shadow. These lynchets are evidence of ancient agricultural work, and very much a sign that there will be some degree of nearby settlement.

Often in association with this type of earthwork you will notice other varieties of lumps, bumps, and ridges. Some of these may be drovers’ ways where herdsmen guided their livestock to market. Others may be hollow ways, which are old tracks that can have very ancient origins. Many hollow ways and tracks can be evident in areas where a later village became detached from the church. Another type of settlement indicator to be aware of is the “baulk” often associated with Iron Age settlements. In many cases this is noticeably evident where a field edge drops sharply several feet for quite a distance. The baulk can be semicircular, nearly completely circular, or simply a fairly straight linear depression. When observing such features, often something will nag at you such as, “It’s not geological in this area, it must be man-made.” Often these baulks are used as modern agricultural tracks.

Fig. 7. Ernie searching a medieval site on which the house platforms and ditches have been flooded by heavy rain.

Sites where ancient windmills once stood are still often emphasised with a slight mound, sometimes referred to as a “tump”. It is worth remembering that sometimes ancient windmills were established on an already existing feature such as a Roman or even earlier burial mound. We found a superb example of a “tump” in meadowland that was ploughed for the first time since the Second World War. Unfortunately, the top of the mound was thickly covered in flints, pottery and tile. It was impossible to detect on the immediate site due to a dense covering of collapsed building debris, but around this finds were very prolific.

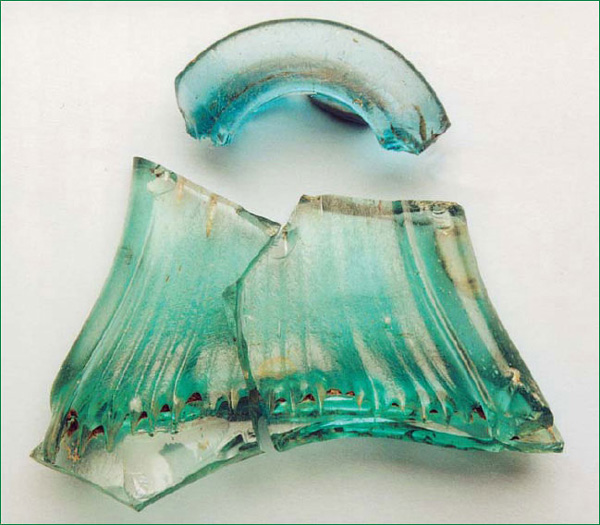

Fig. 8. Fragments of a Roman glass vessel found on a Roman villa site.

Chalk Pits & Chalk Quarries

In the past, particularly in Victorian times, the digging of chalk pits revealed many ancient habitation sites and cemeteries. Some chalk pits may even have Neolithic flint mining origins. Perhaps of more interest to the detectorist is that the Romans also excavated many such pits. This is evidenced in some areas by open pits and filled depressions alongside Roman roads; these pits once provided quarried flint for road metalling. Today, many of these pits are simply overgrown or ploughed out hollows. However, there are many pits that are still open and provide a deep cut face into the local soils.

One such pit that we investigated has a crumbling chalk face. Recently, a huge portion of this collapsed revealing a cross section through an Iron Age refuse pit. This was a real surprise as nothing from this period had been located here before. The pit itself was about 4 feet deep and consisted of layers of burnt cobblestones, broken pottery, and pig and goat bones. Some pottery still showed scorch marks from cooking and was in perfect condition. From among all this refuse we found a perfect handmade clay loom weight, still showing finger print markings from the person who had moulded it over 20 centuries before. Our next task is to locate the settlement associated with this pit.

Please use extreme care and caution when visiting such sites, and preferably go with a colleague. Exposed vertical chalk faces have a tendency to be very unstable. When quarry work is in its early stages the topsoil is often removed from huge areas. In localities where the topsoil is only a few inches in depth this means that foundations and ditches etc would actually be cut into the chalk. When these are neglected and are finally demolished or the top structures eroded away, the remaining features will often re-fill up with topsoil.

The topsoil filled sunken sections of Anglo-Saxon “Grubenhaus” style structures particularly exemplify this, as they can appear as clusters of oblong darker patches. Other features that can regularly show up in this variety of topsoil removal include postholes of timber framed buildings, and cremation cemeteries. I can remember visiting the site of such a cemetery that dated to the late Iron Age. The topsoil had been skimmed away leaving hundreds of small round dark patches at about 8 inches depth. Upon closer examination, each darker area consisted of burned bones, and scorched flints with traces of charcoal. No pottery fragments or even any associated artefacts were found on this site, so it appeared that the bodies had simply been cremated and their ashes collected and deposited into holes in the ground.

Fig. 9. Some of the pottery and building debris found on a villa site.

Therefore on a white, chalky or pale background you can on occasion clearly see outlines of buildings, ditches, barrows etc. Although we are primarily concerned with chalk here, any area subject to extreme soil removal (e.g. sand or gravel quarries) are all equally well worth investigating.

New Road Routes Involving Cuttings, Pipelines & Building Sites

Seeking permission to search these types of locations for ancient features is also very worthwhile; as always be on the lookout for anything slightly different in colour, texture etc. As already mentioned, local newspapers are the best source for keeping track of new developments.

If you locate anything that you believe may be of serious historical interest you should immediately report your findings to your local museum or archaeological unit.

Any old or ancient ditches, foundations etc that intrude into the soils, clays or chalk will almost always fill up with new topsoil as they become deserted and derelict. With regards to particularly ancient flint mines etc, later glaciation could be responsible for filling them with clays and pebbles. Concerning cuttings and new verges these can often truncate signs of ancient activity. Different deposits of soils and clays or stones may be able to help you date certain features.

Always keep an eye open for other signs of activity (i.e. tiles and oysters that may appear in the band of top soils at the uppermost section of the cutting). Also look out for areas of burned earth; if quite large these could indicate the presence of kilns. If they are smaller burned patches and widespread, they could indicate the sites of hearths or even a cemetery with, therefore, hopefully associated settlement.

Other areas worthy of searching along are new pipelines. These initially involve an often deep trench being excavated to lay the pipeline. Searching and checking the spill from these excavations can be very productive. Such a pipeline in our locality revealed the foundations of a Saxon hut as well as two Roman inhumation burials. Several basic earthenware pots accompanied the burials, as well as a wonderfully decorated samian bowl.

Drainage Ditches, River, Pond & Moat Dredgings

In areas that are prone to flooding, many farmers dredge out frequently or even excavate new ditches alongside field edges. The removed soil can be well worth examining. One such ditch we examined contained some superb examples of Roman and medieval pottery fragments. These included colossal storage jars and amphorae handles, many still with the potter’s complete fingerprints remaining on them.

Look out for rivers that pass through or near sites of interest. These are sometimes dredged, and numerous interesting items are often brought to the surface by this process. Such dredgings are often spread near the river but in some cases can be removed and deposited a considerable distance away.

The same principle applies to moats excavated in medieval times. Adjacent to these, and the enclosures they delineate, the soils can be totally different to those normally found in that area. This is due to the deposition of excavated soils, clays, gravels etc. Such moats that have been dredged since construction can yield some excellent metallic finds as well as un-abraded ceramics.

Many village ponds have also been dredged in recent years. The dredgings are usually dumped locally, more often than not in the corner of an agreeable farmer’s field.

One such local example, when newly deposited, yielded over 20 superb condition copper kettles, and still to this day releases good examples of white metal Victorian commemorative medallions.

Over the years we have read, seen and heard of complete Roman pots, beautiful un-patinated bronze coins, and Saxon as well as Viking artefacts coming from ditch/river based soil deposits. Such areas are always worth keeping an eye out for, as the artefacts they bring to the surface are often in wonderful condition, not having been subject to any agricultural disturbance.

Drainage ditches offer an exciting opportunity to detect at normally unavailable depths. Old drainage ditches will almost certainly have had the excavated soil spread evenly around their edges. So it`s a good idea, even if the ditch was dug over 100 years ago, to search a good 25 feet on either side where possible. Newly excavated ditches may offer the opportunity to search inside the cut or – if too deep or permission is refused – then the obvious excavated soil around them is worthy of attention. Recently a stunning gilded late Roman disc brooch was found in just this type of ditch-excavated soil. It was in such good condition as it had previously been at a depth beyond the plough and the reach of chemical effects.

Animal Presence As An Indication Of Past Human Activity

Animal presence can be a very good way of helping to assess the potential of a site. Rabbits and badgers often dig down to great depths; never miss an opportunity therefore to search the soil spill near their holes.

So far we have seen tiles, oysters, and pottery fragments evident in such soil spills. There is one thing we have noticed that we believe might be of interest to fellow detectorists. On numerous Roman and medieval sites, after ploughing and rolling, there is a great deal of mole activity. Flocks of crows, gulls and pigeons also congregate on such sites. The only reason for this seems to be that past habitation has changed the soil type into a richer organic medium. This is most likely caused by many, or even hundreds of years, deposition of waste organic matter. This, in turn, has led to a greater amount of earthworm activity than in the surrounding, often heavier soils. The moles and birds are obviously taking advantage of the increased food source. Migratory birds such as the golden plover usually have traditional drop-in sites to feed on their journey. Many such sites have been found to be ancient sites. Due to the higher concentration of worms etc the birds get a good feed for the minimum of effort.

Fig. 10. Part of a badgers’ set.

Molehills are also worth checking, as on habitation sites they are often packed with pottery, tile and decayed plaster fragments. On some Roman and medieval sites where there is extensive subterranean decayed plaster deposits, mole activity can assist in creating a much paler appearing area in the soil. This is due to plaster being brought to the surface, and in some cases further distributed by agricultural activity.

While you are out in the countryside, the calls and presence of ducks and moorhens can lead you to discover small hidden stretches of water. Some will be ditches or natural ponds, but others may be moated sites or defensive earthworks worthy of further research.

Some years ago, the spotting of several moorhens feeding alongside a wood led to us discovering a tiny moated site. Amazingly, this did not feature on any maps or records we had looked at. Therefore when I look at the marvellous finds made in the area – including four lovely hammered groats – it is to the waterfowl that I give thanks.

The Presence Of Plants & Trees

Plants and trees can often reveal soil type, and therefore can be good indicators of settlement. Recent house sites and Victorian dumps can abound in ground elder. On chalk downland the common nettle can be an indicator of activity. We know of one ancient house and several old farm sites on grassland that can almost be mapped out room by room by their associated nettle growth. Willow trees and alders indicate areas of wetland that may have been ancient ditches or moats. Sometimes ancient gnarled willow trees can still show the course of a river that has long since dried up; searching along these could reveal many finds.

The shape of some trees, such as that caused by pollarding is also indicative of human activity. Some ancient hornbeam woods, as well as willow trees, were pollarded hundreds of years ago. With such a strenuous, labour-intensive activity many losses would have occurred.

Pollarding is noticeable by a thick tree trunk, often topped in a swelling crowned with many offshoots. If your interest is in items of Georgian, Victorian or Edwardian finds look for traces of old orchards. Pears and some prunus (plum) varieties spread well and live to a great age. Even sparse evidence of such cultivated fruits may indicate the garden of a long demolished house. Many years ago the finding of a Victoria plum tree, in the middle of nowhere, made me look further. I then noticed some ancient pear trees, and a solitary walnut tree. Looking around the site, I spotted some old bricks and willow pattern china fragments below the nettle growth and even an old tin bath in the hedge. Searching around the field edges abutting this area uncovered some of the best ever Victorian and Edwardian coinage we have found. Sometimes it takes just a single slightly unusual feature to make you stop and examine the potential of the area upon which you stand.

Field Surface Flooding

On both meadowland and ploughed land, we have noticed that areas where collections of individual small houses or a villa etc have stood tend to be marginally shallower than the surrounding levels. Sometimes these shallow basins are only noticeable if you crouch down and look sideways along the field contours. It seems that after a while animal and human activity compacts the floors and surrounding paddocks etc.

Many of these sites are obvious in wintertime where, with severe rainfall, shallow flood pools are often to be found exactly where the buildings stood. Of course, after flooding other factors become enhanced such as pottery, tile and stone scatters. Other features prone to surface flooding which reveals their presence are old boundary/defensive ditches, Roman canals, strip lynchets, ploughed out tracks, and the sites of ancient filled in ponds. Medieval moated sites mainly exist these days hidden away in small areas of woodland and meadow. Even though they can be dry most of the year, a few hours of rainfall can refill them again, making them temporarily more obvious – particularly when partially obscured by summer undergrowth. In times of extreme flooding, ancient river routes may re-appear as may long ago drained lakes and meres. Both can be well worth recording and searching at a later date.

Fig. 11. A major excavation on a P51 Mustang crash site.

Worked Flints, Glass & Bones

Almost every landowner or seasoned detectorist I know has found at least one example of a worked flint. Fieldwalking will obviously allow a good chance to experience and collect a huge variety of non-metallic items. Not long ago I saw the most beautiful Palaeolithic hand axe simply picked up by a farmer as he walked over his land after a recent rain shower. This same farmer also has one of the best private collections of fossils that I know of, ranging from dinosaur vertebrae to a section of mammoth tusk.

Glass is another substance that is often encountered. Whether it derives from a Victorian bottle dump, is a fragment of Saxon bead, or part of a Roman window, glass is a good indicator of activity. With glass there is no real rule of age by colour; more often it is texture and bubble formation that helps to date it.

It’s quite amazing on old dumpsites and edges of large houses how many relatively recent Sunday joint bones one can encounter. Meat consumption for humans goes back probably well over a million years, and therefore butchered bones are a vital clue in the search for habitation. Bones – unlike the sun bleached white oyster shells – are prone to colouration and chemical change influenced by the soil type they are deposited in. Bones from acidic peat soils can be brown to almost black, and on occasion can be very hard to date scientifically due to mineral absorption. Examples found on agricultural soils are slightly easier to date. In our experience we have found that bones relating to medieval and Roman sites are mostly creamy white and have a hard calcite-like texture. The human bones I found in association with an Iron Age cremation actually “chink” when moved as if made from stone. Iron Age sites that we detect upon have widespread scatters of pig and goat bones, while most Roman sites we know of seem to be strewn with horse bones, and strangely these are mainly sections of broken rib. One such bone found still bore the knife marks from when the animal was butchered.

Fieldwalking & Crashed Wartime Aircraft

It may be that your particular interest is in finding relics and artefacts in association with crashed wartime aircraft. This still represents a large section of metal detecting activity in the UK. In searching for the whereabouts of such an incident, many previously mentioned factors and information sources can be used, but there are also a number of different issues to consider as will be outlined briefly.

Most wartime crashes were photographed and there are a number of sources where you can still obtain copies of the prints. The presence of a photograph can be invaluable in pinpointing exactly where an aircraft came down. With all historical incidents traced by using contemporary photographs, don’t forget to take your own modern day shots of the same scene if possible. Comparing photographs to see how much or how little a scene has changed can be fascinating, and will be of great interest to future researchers.

Fig. 12. An overgrown bomb crater from an American 100lb bomb.

In 2011, after I had completed some 30 years of research, the family of an RAF crewman who had been involved in shooting down a massive German Heinkel He 177 made contact with me all the way from New Zealand. When I had been researching this crash I simply could not locate a wartime photograph of it. The relatives informed me that four photographs were in the RAF man`s log book. They emailed me copies and it was the very aircraft I was researching; I even recognised the oak tree in the background. This resulted in a very successful excavation of the exact crash site in August 2011, thus allowing several artefacts from an extremely rare type of aeroplane to be excavated and fully conserved.

I know of many detectorists who have actually discovered the site of such a crash through searching an area for un-related artefacts such as Roman coins. If you are seriously thinking about taking up this side of metal detecting as your main interest, there are several things to consider. Firstly, all wartime relics associated with crashed aircraft technically belong to the Crown (even German ones) pursuant to the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986.

No one minds you accidentally stumbling across a such a crash site and finding a few scraps of alloy etc; however, if you are considering a serious excavation based upon your metal detector finds you will need to apply for a licence from the Ministry of Defence. All such buried remains are subjected to the Protection of Military Remains Act; therefore this licence must be obtained before any excavations are progressed.

Obviously, the first consideration in location is to attempt to see if any local residents remember the incident. If they do, they may know precisely where your aircraft crashed, or at least an approximate area. Even an approximation places you a great deal further ahead in your research than previously. You may be surprised at how many artefacts were “liberated” from crash sites that remain tucked away in drawers or barns even today. So get yourself known by local people and if you are successful you will begin to be shown many such items.

Woodland Crash Sites

Due to the inaccessibility of most types of woods during the Second World War (and ever since), it is still possible to find quite large pieces of aircraft in them. However, with increased interest in such relics the amount of these pieces available diminishes with each passing year. If you know that the particular aircraft you are interested in crashed in a wood, several factors need to be taken into consideration. For example, are there any small to medium sized areas of different plant or tree growth? Often a burning aircraft will seriously affect the stability of soil. Due to the presence of oils and other pollutants it might take years for growth to recover.

Fig. 13. General aircraft crash site debris found by fieldwalking.

In mature woodlands observe any large gaps in the canopy. In and around these areas try to examine the ground for fragments of metal, rubber etc. Patches of blue crystalline powder are a good indication that you are in the right area, as this is probably aluminium oxide. This results from aluminium that has been weathered or buried for quite a time. Also examine tree trunks and large branches for any obvious structural damage (however, remember that the 1987 storm/hurricane damage is still very much in evidence, so be careful in your conclusions). In some cases severe tree damage may actually be in association with fragments of aircraft metal actually protruding from these areas. I once saw a section of propeller blade projecting from the trunk of a mature beech tree, and at the time of observation the crash had happened 52 years before. If you are lucky, therefore, and sharp-eyed you may still find such graphic evidence.

It can also be very revealing to pass the search head of a detector up and down tree trunks in both actual and suspected crash site areas, but do not damage living trees. While the bark of most coniferous trees heals well from small wounds, the inner wood does not. If there are any dead conifers in the area you are investigating try peeling away some bark; the tiniest abrasion caused by impacting metal etc will show up on the inner wood surface really well.

Metal detecting on a local B17 crash site within woodland revealed hundreds of fragments of airframe, along with crumpled cockpit instruments. Of all the numerous finds the most poignant was a twisted and crushed Lieutenant`s cap badge. This was later shown to an eyewitness, who found it astounding that 59 years later he was able to handle such an emotive artefact from an event he had seen as an 11-year-old boy.

Crash Sites On Arable Land

If when wandering a field you come across a profusion of twisted aluminium, once molten metal globules, Perspex, rubber, bullet cases etc, the chances are that you have discovered the site of an aircraft crash. Dating the crash can be reasonably well ascertained from the items that you may find. Bullet cases, for example, are quite often dated although you need to be aware the bullets may have been in storage for some time before use. Sometimes serial numbers can be found on maker’s and manufacturer’s plates. Small stamps applied to spars and other parts of the airframe etc can often tell you who the manufacturer was, and may also bear dates.

Fig. 14. An SC50 German bomb from a Dornier 17 crash site – found by a metal detectorist.

Similar factors discussed previously also apply to air crashes such as differences in soil coloration, stone scatters, and perhaps crop marks. Where the soil has been burned this may show up as a darker patch. I know of a local Lancaster crash where you can still see the difference in soil where the four engines impacted the ground. If the aircraft penetrated the surface and either it or on board bombs/fuel tanks exploded, this will bring up different strata of stones or soils. These can remain visible for many years, and may encourage a different level of crop growth or weed infestation. Even today on some crash sites, particularly in heavy clay districts, it is possible to take a pinch of soil and still smell grease and aviation spirit in it.

In some ploughed fields with chalky soils, grease from aero-engines etc degrades into a bright purple or pink substance, which is highly visible. Check any ditches alongside known crash sites, as in the last 60 years many large parts of aircraft have been ploughed up and removed to adjacent ditches. Numerous finds are made in such places. I was recently investigating the crash site of a B24 Liberator and in a nearby ditch spotted 5 feet of stainless steel belt linkage once connected to one of the 0.50in calibre machine guns. This aircraft had exploded with such violence it had blown away a huge section of hawthorn hedge; this has never grown back.

In the course of detecting anywhere, always be cautious of large unidentified buried or partially buried metal objects that you uncover as many wartime bombs, grenades and rockets remain undiscovered. The larger bombs are either accidentally dropped Allied bombs, deliberately dropped enemy ones, or those from both sides still trapped in underground lying aircraft wreckage. Obviously, the chance of this type of find increases around Kent, outer London and other heavily bombed areas. Should you find any unexploded ordnance, mark the spot and then inform the landowner and the police as soon as possible.

Always treat anything suspicious with the respect it deserves, as some old explosives deteriorate and become highly unstable. In reporting the find you have carried out an act beneficial to the public, as the dangerous item will be disposed of.

Crash sites themselves should always be treated with the greatest of respect, particularly where human lives have been lost. Should you find personal items or effects, such as human bones or rings, wristwatches, identity tags etc you should notify the police and the Ministry of Defence as soon as possible. Even after 60 years such finds are still possible. I recently saw the wallet from a P47 Pilot killed in 1943. This came from a licensed excavation, based on a previous metal detector assessment. Remarkably, when opened there were still photographs of his girlfriend and two penny postage stamps inside, as well as his car keys.

Although this is only a small section on aircraft crashes we hope that it has maybe broadened your horizons into yet another aspect of the fascinating hobby of metal detecting.