Kristan Lawson

THE PRIVATE PARTS ON THE POPE’S ALTAR

THE VATICAN, IT IS WHISPERED, harbors secrets. Forbidden archives overflowing with banned books and suppressed manuscripts—not to mention the world's biggest collection of antique porn—languish in locked storerooms hidden deep in the recesses of the Holy See's sanctum sanctorum. Or so the legends say. But these areas of the Vatican are completely off-limits to visitors, so the odds of someone like you or me ever seeing them are practically nil.

Which is a tad disappointing.

Yet the Vatican's strangest secret is not hidden at all. In fact, quite the opposite: It's smack-dab in the center of one of the most heavily visited spots in the world. Crowds of gawking tourists and pilgrims brush by it all day, sometimes briefly looking right at it but never really seeing it. Of the four million people every year who unwittingly visit the site, perhaps only a handful understand what they're looking at.

Someone—it might have been Agatha Christie—once said that the best place to hide something is in plain sight. Never has that aphorism been more successfully put to the test than in the case of the indecent carvings on Christendom's most sacred altar, which have been there for the last 400 years.

Consider this.

In the observable universe, only one planet is known to harbor life: earth. And on earth, only one species has ever attained consciousness: the human race. And the highest form of human consciousness, according to most cultures, is spirituality. And the form of spirituality with the most adherents, and by far the greatest historical importance and influence, is Christianity. And the center of Christianity is Rome. And the focal point of Christianity in Rome is the Vatican. And in the Vatican, the seat of Christendom is the Basilica of St. Peter. And the Basilica of St. Peter is so named because it was built atop the tomb of St. Peter, chief among the Apostles, Jesus’ chosen favorite, the acknowledged founder of the Christian church. And recent archaeological discoveries revealed that St. Peter is indeed buried in the exact center of the Basilica. And built directly on top of St. Peter's grave is the High Altar, also called the Papal Altar: a structure considered so holy that only the Pope himself is allowed to touch it.

Yet the Vatican's strangest secret is not hidden at all.

By this reckoning, the Papal Altar is the most sacred spot in the entire universe. Sure, other religions have their holiest of holies—Judaism's

Western Wall, Islam's Kaaba, and so on—and even Christianity has other contenders, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. But for palpable religious power, architectural magnificence, and historical import, nothing can top the High Altar of St. Peter's.

But wait—there's more. On the structures enclosing this High Altar are carvings created by the artist whom many consider the greatest sculptor of all time: Gian Lorenzo Bernini, he of the orgasmic Ecstasy of St. Theresa, among countless other masterworks.

So there you have it: the most sacred altar in the precise center of the most important church of the most significant religion in the world. Just what, exactly, did the greatest sculptor of all time carve there? Care to venture a guess?

Would you believe...female genitalia? In explicit detail? And not just once, but eight times?

WHEN YOU ENTER St. Peter's for the first time, you are overwhelmed by its sheer scale. The arched ceilings are impossibly high, the gold-and-marble walls impossibly regal, the artwork impossibly beautiful. Every niche boasts yet another larger-than-life saint, flawlessly rendered by this or that Renaissance genius. Towering Latin inscriptions loom overhead, radiating sanctity and majesty even to those who can't understand a word. Travelers and supplicants are swallowed up by the Basilica's vastness.

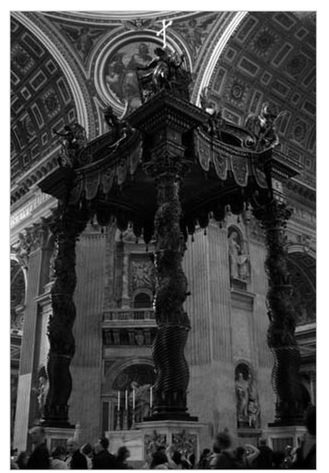

And in the center of it all, where the nave and transept meet, is something unexpected: a heavy, dark bronze canopy held up by four slender, spiraling columns which, as you approach, you slowly realize are almost ridiculously tall, reaching as high as a five-story building. This peculiar structure is the Baldacchino, the sacred canopy that covers the High Altar. A holy gazebo. St. Peter's Baldacchino is not the only one in the world; many cathedrals and large churches have their own baldacchini . Originally they were made of cloth, supported by wooden poles: simple coverings meant to demarcate hallowed ground. Over time the baldacchino —called a “baldachin” in English—evolved from a flimsy, temporary canopy into a permanent structural edifice.

In 1624, as part of a series of renovations at the Vatican, Pope Urban VIII commissioned his favorite artist, the young Bernini, to design and build a baldacchino over the new High Altar, which itself had been installed only a few years beforehand by a previous Pope. (Interestingly, the new High Altar completely encased the previous High Altar, which in turn encased the preceding one, and so on, presumably all the way back to 326 C.E., when the first shrine was constructed on top of St. Peter's grave.) Here the Pope alone conducts the most sacrosanct of Catholic rituals, on Easter and a select few other holy days—which is why it is sometimes referred to as the Papal Altar, since no one but the Pontiff is permitted to use it.

The Vatican's High Altar with the Baldacchino. Credit: eva bd of Wikipedia

Bernini outdid himself, creating the Baldacchino to end all baldacchini (earning itself a capital “B” to distinguish it as the one and only baldacchino that mattered). Using bronze ripped from the still-standing Pantheon (the ancient Roman temple to all gods), Bernini succeeded in turning nearly 14,000 pounds of metal into an airy and frilly simulacrum of a cloth canopy. The striated columns twirl skyward, festooned with an absurd profusion of baroque details—leaves and sunbursts and cupids and doves and faux-tassels amidst a plethora of inscrutable Papal emblems. It's all so overwhelming that most modern visitors just stand and stare upward, trying to absorb the magnificence until their neck muscles give out.

While Bernini presumably was not allowed to be sexually explicit in his depiction, he did get away with a stylized representation of a woman's reproductive organs in detail that is remarkably anatomically correct.

But the Baldacchino itself, finished in 1633, is actually of little importance to this story. As far as we're concerned, it serves only one function: to distract visitors from something even more interesting below. In fact, it's because of the Baldacchino that so few notice the carvings that are the focus of this chapter. Turn your attention now to something seemingly more pedestrian: the marble bases on which the Baldacchino's four columns rest and which stand at the four corners of the High Altar's platform.

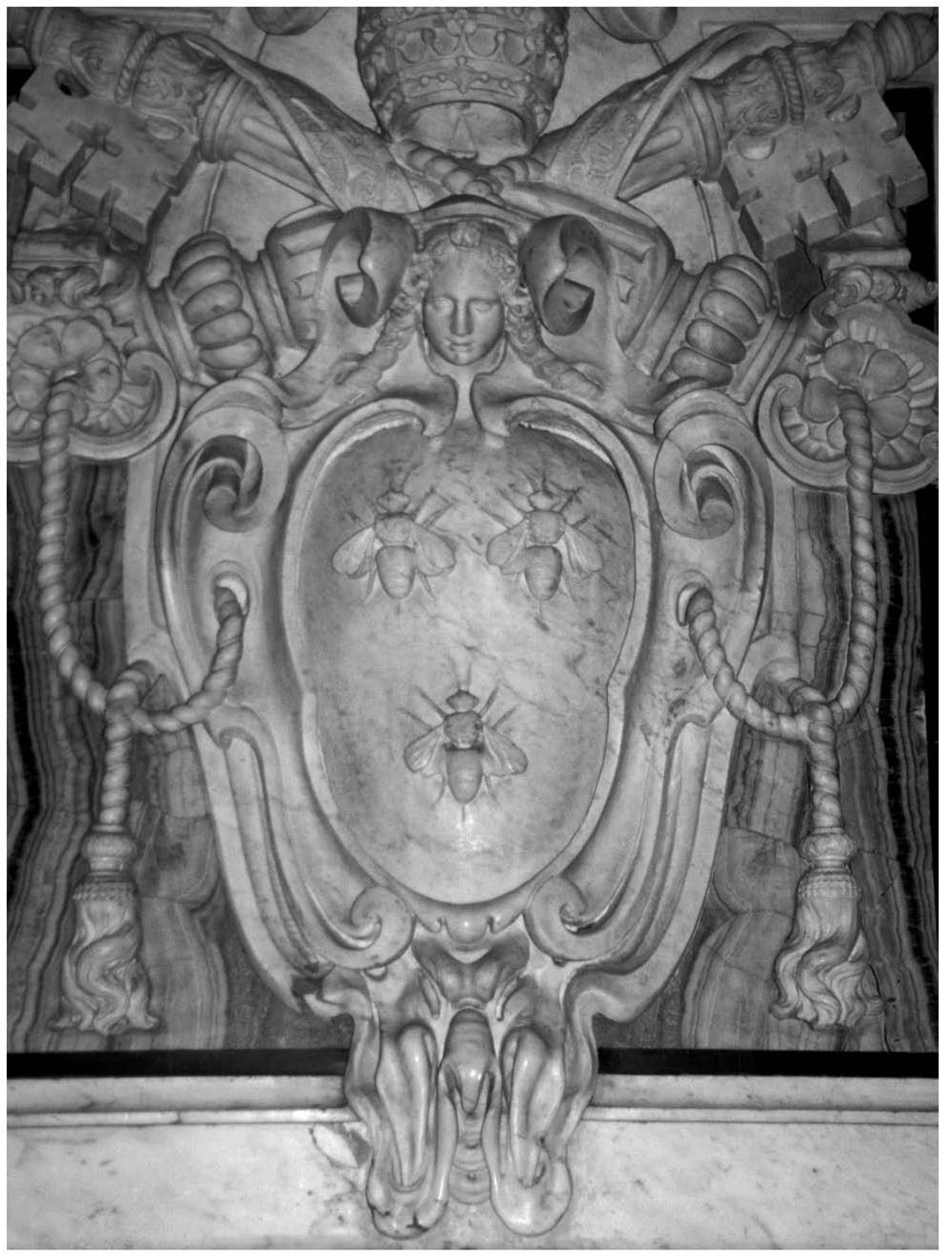

Compared to the splendor around them, the four column-bases are somewhat unremarkable at first glance. The two outward-facing sides of all four bases (hence, eight sides in total) feature figurative carvings which, upon close inspection, are all nearly identical but subtly different from each other. Take a look at the photograph on the following page (which I snapped myself) and ponder each of the elements of the series’ first carving.

Pope Urban VIII was born Maffeo Barberini, a member of Florence's powerful Barberini clan. When he was named Pope, he combined the Barberini insignia and the Papal emblems to create his own special coat of arms. The altar carvings all show a stylized version of Urban VIII’s unique coat of arms but with strange and subtle alterations. The top portion comprises the Papal emblems: a crown, specifically called the Papal Tiara, above the two crossed keys to the Kingdom of Heaven which, according to the Bible, Jesus symbolically gave to Peter while telling him: “And I also say to you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build My church, and the gates of Hades shall not prevail against it. And I will give you the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven” (Matthew 16:18-19, NKJV). Below that is a shield on which rest three bees—the Barberini insignia.

So much for what Urban VIII’s coat of arms was supposed to look like. As you can see, Bernini added two conspicuous elements: a woman's face above the bees, and what looks like convoluted bodily organs below. In each of the eight panels, the face and the organs change slightly. They're meant to illustrate, of all things, the process of giving birth.

Competing theories, as we shall see, debate the meaning of the carvings, but all of them concede that the figure's lower portion is supposed to represent a woman's “naughty parts.” In fact, the bees are also supposed to represent elements of her body. The face at the top is her face (obviously); the shield is her torso; the two top bees are her breasts; the lower bee is her navel; and the volutes at the bottom are her genitals.

And look closely at those genitals. While Bernini presumably was not allowed to be sexually explicit in his depiction, he did get away with a stylized representation of a woman's reproductive organs in detail that is remarkably anatomically correct. What's especially noteworthy is that the vagina is depicted in what looks like a cut-away view; the top wall is not shown, revealing the interior vaginal canal. To the sides of the vagina are folds representing the labia minora and labia majora. And at the top is a protuberant nub that could represent the clitoral hood.

Through the course of the eight panels, a series of changes takes place in each of the elements as the pregnancy progresses. In the first panel, the woman's face is young and smiling. With each successive scene, her mouth opens, and she begins to either grimace or scream in pain. Her “belly” (the shield with the bees) swells and broadens. And her vagina opens up and spreads. In the final panel, a baby's face replaces hers, and the belly and genitals return to normal.

BERNINI’S SCULPTURAL SERIES, therefore, unquestionably shows a woman's pregnancy, labor, and childbirth. But why? And why, of all places, on the High Altar of Christendom?

The first carving of the series. Credit: Kristan Lawson.

It's almost impossible to find photos of them in any book about Bernini or St. Peter's Basilica, no matter how comprehensive.

The answer to that question is not easy to find. Biographies of Bernini make only passing reference to the altar carvings; some don't mention them at all. It's almost impossible to find photos of them in any book about Bernini or St. Peter's Basilica, no matter how comprehensive. One of the difficulties is that we don't know for sure whose hands actually carved the designs. Bernini was the man in charge, and he certainly was a master sculptor. But he was helped by a small army of assistants, including his rival, Francesco Borromini, and Bernini's brother-in-law, Agostino Radi, both of whom conceivably could have actually wielded the chisel to render Bernini's design, as a few scholars have speculated. Even so, the general consensus is that Bernini either did the actual carving himself or made the design and assigned its rendering to an underling.

Most catalogs of the artwork on display in the Vatican similarly gloss over these particular carvings, a few mentioning them briefly as being merely the Papal coat of arms. Guidebooks point visitors to the Baldacchino above but almost universally ignore the altar carvings. One is tempted to speculate that this silence is intentional, a suppression of the embarrassing evidence. But here and there, in obscure sources (mostly in Italian), the carvings are mentioned, and answers are given. The problem is, they don't all agree on the details—though one thing on which they almost all do agree is that the carvings indeed depict a woman's genitalia.

In my survey of rare, old sources, I eventually uncovered no fewer than four different explanations as to the origins of Bernini's design. The first theory is the most commonly cited, though it's not completely clear which of the four is most likely to be true.

Theory 1: The carvings depict the troubled pregnancy of the Pope's niece.

Pope Urban VIII had a niece who was experiencing a difficult pregnancy. Everyone expected it to end badly, for her to die in childbirth. In desperation, Urban VIII made a public vow to God that he would bequeath improvements to the High Altar if God would intervene and allow mother and child to survive the birth. Miraculous or not, the birth went smoothly, and Urban VIII followed through on his promise. He hired Bernini to create a new baldacchino. But it was Bernini, aware of the circumstances of his commission, who came up on his own with the idea of depicting the successful pregnancy on the column's bases and revealed them as a surprise to the delighted Pope.

While this charming story seems on the surface the most likely to be the real explanation behind the carvings, a few troubling details cast doubt. First off, the mysterious niece is never named—which is odd, since the Barberini family was very well-known, and if Maffeo Barberini had a brother, who had a daughter, we almost certainly would know their names. Secondly, one needs to keep in mind exactly where this is: the High Altar in the Vatican. Would a Pope really allow such a personal, trivial, and (some would say) obscene artwork to be permanently displayed at such a high-profile sacred location? If there's no greater significance to the story beyond that of some relative of a Pope having a baby, it seems quite odd that it would be immortalized on the most important altar in the Catholic world. Why not depict the Virgin Mary's pregnancy, if a pregnancy is to be depicted at all? Why not depict the martyrdom of St. Peter? Or Jesus? Or any other significant religious scene? What's so important about little Miss Barberini that she trumped the Savior of mankind?

Theory 2: The carvings depict the scandalous pregnancy of Pope Joan, history's only female Pope.

The legend of Pope Joan—which has been popularized recently in TV specials and books—tells of a young woman from England who disguised herself as a man, traveled to Germany (or in some versions, Greece) in the ninth century, became a famous ecclesiastical scholar, and was eventually elected Pope in 853 C.E. Serving under the name John VIII, she reigned for only two years, as in 855 she gave birth in public after going into labor while riding a

horse. Her true gender thereby revealed, she was stoned to death by outraged Romans.

The existence of Pope Joan is still debated, though most scholars insist that her story is nothing more than a legend; detailed, reliable chronologies of the succession of ninth-century Popes leave no room for the two-year reign of a “secret” Pontiff, male or female. Even so, the Catholic Church itself seemed for centuries to accept the story as possibly true, and it wasn't until the fifteenth century that it officially repudiated the fable. By 1624, when these carvings were made, the Church's unequivocal position was that no such person as Pope Joan ever existed. Why then portray her in the most obvious place imaginable?

(Interestingly, Pope Joan lives on in our culture as the High Priestess in the tarot deck. In the first tarots, the High Priest and High Priestess cards were called the Pape and Papesse—the Pope and Popess. The very concept of a “Popess” was based on the legend of Pope Joan.)

The Pope Joan theory might be the most colorful explanation, but it is also the least likely. Nowhere else in any Catholic iconography is Pope Joan depicted. The Church even had previously removed and destroyed the only other statue elsewhere in Rome that was rumored (probably falsely) to portray her. Why would it then put her right in the middle of St. Peter's, even as some kind of not-so-”secret” clue about the existence of this historical embarrassment?

Theory 3: The carving is an allegorical representation of the Church giving birth to Truth.

This theory is put forth by Catholic writers fishing around for a respectable, nonsexual interpretation of Bernini's creation. It doesn't actually show a real woman's body, they say, but rather just a symbol of how the Catholic Church is the mother of Truth. Alternately, a few writers claim that the scene shows how humanity (represented by the young woman) suffers while awaiting salvation (the birth).

Nice try, but I’m not buying it. The face of the woman and her distorted expressions are too personalized, too specific to be merely an allegorical figure, which are almost always idealized, symmetrical, and glamorous. (The Statue of Liberty is perhaps the most famous statue of an allegorical figure.) Why would Bernini portray the Catholic Church or humanity in general as a grimacing girl?

Theory 4: The carvings celebrate the “Sacred Feminine” that secretly lies at the heart of Christian theology.

This is the theory that everyone wants to be true. And by “everyone,” I mean feminists, neo-pagans, postmodern intellectuals, conspiracy theorists, The Da Vinci Code fans, and anybody who likes “weird stuff.” The unambiguous maleness of the deity in Judeo-Christian beliefs has often bothered critics of monotheism, who argue that before the religion of Abraham arose, humans saw God or the gods as having both male and female aspects. This ur-Goddess, as championed by followers of anthropologists such as Marija Gimbutas, was a pancultural counterpart to and companion of the male figure we now know as “God.” As this theory holds, the three main monotheistic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and, later, Islam—came along and quashed this divine feminine, creating a patriarchal culture and all the subsequent misery of the modern world. But hidden within the masculine theology is a buried thread of the Sacred Feminine, for those who care to look.

Here we could spin off into Holy Blood, Holy Grail territory and speculate about Sophia, the feminine counterpart to Christ in Gnostic beliefs, and all the cryptic clues to the real meaning of Christianity, but no—hang on a minute. Let's go back to Bernini's sculpture. It's just a girl. And Bernini almost undoubtedly devised the design himself—Urban VIII was no artist. What would the conversation have been between the two?

“Gian Lorenzo, I want you to build a big bronze canopy over the new Papal Altar.”

“Sure thing, Maffeo—whatever you say.”

“Oh, and while you're at it—on the bases of the canopy's columns, could you carve eight depictions of the Divine Goddess that lies at the heart of Christianity, a forbidden secret that we've been trying to suppress for 1,600 years? I want to make sure everyone knows about this.”

“Can I show her genitals in explicit detail?”

“Of course! What good is Sacred Femininity without some nice genitals?”

But ponder this: In Islam, the only site that is comparable to the High Altar is the Kaaba, a tall, brickwork cube housing what is believed to be a meteorite. It is considered the holiest site in the world. The

hajj—the pilgrimage to Mecca—revolves around

the Kaaba, which every able-bodied Muslim must see at least once in his or her lifetime. When Muslims around the world “turn toward Mecca” to pray five times a day, they are specifically turning toward the Kaaba. The meteorite—called the Black Stone, or al-Hajar-ul-Aswad—is visible through a small window on the outer southeastern corner of the Kaaba. And here's the kicker: The window and its silver frame are in a distinctly vaginal shape—a circular hole in the center, with tapering, curved lines above and below, accentuated by being exposed in a gap in the Kaaba's cloth covering, which also looks quite crotch-like. How oddly coincidental is it that the two holiest sites of the two largest patriarchal, monotheistic religions both have symbolic female genitalia on them?

Also intriguing is the theory that the organic convolutions in the High Altar carvings start out representing female genitalia, but as the pregnancy nears its conclusion, they morph into the face of a “Green Man” (a pagan life-spirit occasionally found on churches starting in the medieval era, most commonly in the Celtic parts of Europe). With a little imagination, it is easy to visualize a foliate face in the penultimate of the eight carvings. The Divine Feminine, in this theory, is shown giving birth to Life itself.

SO THERE YOU HAVE IT. Four theories, none of them satisfactory.

1 But the sculptures are undeniably there, in plain view, begging for some kind of expla-nation. Of the four possibilities given in the literature, the first very well might be the most likely: that the carvings simply portray a real young woman, a relative of the Pope, going through her pregnancy. Adding to this likelihood is Urban VIII’s notorious nepotism: He gave lucrative Church positions and assignments to his family members and was not above turning the Papacy into a private Barberini fiefdom. It's entirely within what we know of Maffeo Barberini's character to have been so crass as to immortalize a minor family incident in the most conspicuous place imaginable. Or at least, he wouldn't have complained if young Bernini tried to curry papal favor by flattering the Barberinis unbidden.

Whatever the origin and rationale for the explicit carvings around the High Altar, the one indisputable fact is simply that they exist, which by itself is bizarre in the extreme.

The next time you visit the Vatican, remember: Look for the genitals.

A later carving in the series. Credit: Kristan Lawson.

1 Mention should be made here of the only scholarly article ever written in English about the carvings: “The Stemme on Bernini's Baldacchino in St. Peter's: A Forgotten Compliment” by Philipp Fehl (

Burlington Magazine, CXVIII, 1976, pages 484-91). (The word

stemme means “coat of arms” in Italian.) Fehl goes into as much detail as is known about the official history of the carvings but dismisses the possibility that the convolutions at the bottom represent genitalia. In fact, the entire article is devoted to disparaging that concept, brushing it aside as a “cicerone's tale” (i.e., a story told by travel guides meant to titillate the visitor). Instead, Fehl claims, the lower portion is “the distorted face of a flayed satyr.” While it is true that the carving in the second-to-last of the eight panels does indeed acquire a jaw and look rather like a face, as mentioned above, it more resembles a “Green Man.” And the other seven lack the jaw or facial structure that one would expect in the skinless head of a satyr, or any head. But in his attempt to sanitize the meaning of the carvings, Fehl introduced something even more bizarre than a woman's private parts: Why would an image as grotesque as a “satyr's flayed face” be on Christianity's High Altar? Is a horror show an improvement over a peep show?