The Contexts for War

We have observed that increasing human density does not promote warfare and that increased trade and intermarriage do not inhibit it. What conditions (if any) promote or intensify conflict? As noted in Chapter 8, the most common “reasons” given for wars have been retaliation for acts of violence—that is, revenge and defense—and various economic motives. If this generalization is accurate, one might expect warfare to be more frequent in situations involving at least one especially belligerent party, severe economic difficulties, and a lack of shared institutions for resolving disputes or common values emphasizing nonviolence. These conditions are found in the “bad neighborhoods” that are created by proximity to a bellicose neighbor, during hard times, and along frontiers.

In his statistical study of the Indians of western North America, Joseph Jorgensen noticed that raiding activity was clustered rather than uniformly distributed.1 Warfare was more intense in certain regions than in others, apparently because of the presence of a few very aggressive societies that frequently mounted offensive raids. The tribes that were the foci of these raiding clusters were those of the northern Pacific Northwest Coast, the Klamath-Modoc of the southernmost Plateau, the Thompson tribe of the northernmost Plateau, the Navajo-Apaches of the Southwest, and the Mohave-Yuma of the Lower Colorado River. These groups frequently raided not only their immediate neighbors, but also much more distant tribes. Records indicate that the Tlingit from Alaska’s panhandle raided as far south as Puget Sound, and the Mohave attacked groups on the coast of California. The booty acquired by these inveterate raiders varied widely: slaves on the Pacific Northwest Coast and for the Klamath-Modoc; food and portable goods for the Apaches, Thompsons, and Mohave; territory on the Northwest Coast and the Lower Colorado. Other especially bellicose groups in North America included the Iroquois, the Sioux of the northern Plains, and the Comanche of the southern Plains. During the historic period, the Iroquois raided as far afield as Delaware, the Great Lakes, and the Mississippi Valley. South American and Old World examples include the Tupinamba of Brazil, the Caribs of the Guianas, the Yanomamo of Venezuela and Brazil, some Nguni Bantu tribes (such as the Mtetwa-Zulu) in southeastern Africa, the Nuer of the Sudan, the Masai of East Africa, and the Foré and Telefolmin of New Guinea. The aggressive societies at the heart of these raiding clusters were rotten apples that spoiled their regional barrels.

An analogous pattern is recognizable in Western history—various peoples and nations that were especially belligerent for several generations. The list of such Western rotten apples could include republican Rome, Late Classical Germany, medieval (Viking) Scandinavia, sixteenth-century Spain, seventeenth-century France, revolutionary-Napoleonic France. During the nineteenth century, Canada, Mexico, and most Indian tribes west of the Appalachians had war-related reasons to regret that they were, in the words of a Mexican president, “so far from God, so near the United States.” Certainly the twentieth century would have been far less bloodstained if Germany and Japan had been less quarrelsome and covetous societies.

Evidently, then, one factor intensifying warfare is an aggressive neighbor. Most societies that are frequently attacked not only fight to defend themselves, but also retaliate with attacks of their own, thus multiplying the amount of combat they engage in. Less aggressive societies, stimulated by more warlike groups in their vicinity, become more bellicose themselves, devote more attention to military matters, and may institutionalize some aspects of war making. The military sodalities or clubs of the Pueblo tribes of the American Southwest seem to have been an institutional response to Apache-Navajo aggressiveness since they declined in importance and membership (and in some tribes disappeared altogether) after the Apacheans were pacified by the Americans. With their long experience in defending against raids, the “peaceful” Pueblos were anything but peaceable. The Spaniards found them to be tough opponents initially and valorous and effective allies later in fighting with the nomadic tribes.2

Why some societies are more inclined than others to assume the offensive is both an anthropological and a historical puzzle. In most (but not all) of the cases mentioned earlier, the aggressive groups acquired territory at the expense of more passive ones. But whether the desire for more territory causes aggressiveness or whether expansion is merely an effect of bellicosity remains a contentious subject among scholars. Many expansionist nation-states experienced a higher rate of population growth than their less warlike neighbors.3 In some tribal cases, such growth was partially due to the practice of incorporating captive women and children into the tribe, as in the case of the Sudanese Nuer.4 Nevertheless, aggressive American Indian groups should have been experiencing population declines from introduced diseases during the early historical period. Although tribal population figures are usually little more than educated guesses, it often appears that these more bellicose groups either were being less rapidly decimated than their immediate neighbors or may even have had a period of increasing population during their offensive heyday.5 For example, the estimated population of the aggressive Mohave was 3,000 in the 1770s but 4,000 in 1872—the dates that demarcate the period of their most intense raiding activity and territorial expansion. During the same period, the population of one of the Mohave’s favorite enemies, the Maricopa, declined from 3,000 to 400, primarily because of disease.

Rapid population increases can create population pressure by increasing demand in the economy and stressing the capacity of social institutions. For instance, having greater numbers of young men and women in the society requires having larger amounts of valuable commodities available to pay bride-prices or dowries. In societies where the number of achieved (that is, not inherited) leadership or high-status roles is limited, a population boom will lead to more competition for these few positions. Since these are often achieved on the basis of wealth and/or military prowess, the resulting internal competition will encourage more raiding and plundering of other social groups. For example, each new age-grade among several East African tribes could advance in seniority, toward marriage and “elderhood,” only by raiding other tribes.6 This kind of population pressure can occur at any population density, since it is the product of relative growth and not absolute numbers or density. Population increase not only encourages aggression, but also provides a larger manpower pool to absorb the losses that more frequent combat entails and allows formation of larger war parties that are more likely to be successful.

Another relatively common factor in such cases—and one that often accompanies population growth—is the development or introduction of new technology in food production, transportation, and weaponry. The relationship between maritime technology and European expansion is obvious. The introduction of the Old World horse had similar effects on the demography and militancy of many Indian tribes in North and South America. Likewise, the development of a special assegai (sword-spear) and some tactical innovations related to its use were instrumental in the Zulu expansion.7 Although these correlations remain controversial, the relationship between the diffusion of iron technology and the Bantu expansion in Africa, or between horse riding and the spread of the Indo-Europeans in Eurasia, may be prehistoric examples of this phenomenon. Perhaps a rapid population increase provides the push and new technology the pull in making some groups more aggressive. But whatever the reason—land hunger, rapid population increases, or new technology—some societies are more aggressive than others and radiate intensified warfare within their immediate vicinity.

Of course, raiding clusters and the bellicose societies at the heart of them do not endure forever. The hyperaggressive Norsemen have become the pacific Scandinavians. Except for a small class of samurai who used only edged weapons, Japan had been a peaceful, demilitarized nation for almost 250 years before Commodore Perry released its combative genie from its self-imposed bottle. Two generations later, its bellicosity was extreme. But two generations after 1945, Japan is again demilitarized and has one of the lowest rates of violent crime in the world. Within a few generations, the fearsome Iroquois became peaceable yeoman farmers. After a traumatic defeat and temporary exile from their homeland in the 1860s, the Navaho quickly made the transition from rapacious raiders to peaceful pastoralists; the Navaho have since become world renowned for their rugs and silverwork. In time, then, aggressive groups may be pacified by defeat at the hands of equally aggressive but larger societies, or by the loss of their technological advantage when their adversaries also acquire them. Even in the absence of defeat, the zeal of expansionist societies tends to abate as they begin experiencing the diminishing returns of overextension or succumb to the attractions of consolidation and exploitation. Military ferocity is not a fixed quality of any race or culture, but a temporary condition that usually bears the seeds of it own destruction.

Some recent anthropological work argues that frontiers between different cultural groups, economic types, or ethnic stocks are among the most peaceful places on earth.8 Rather than constituting zones of tension and competition between different systems, such boundary regions (according to these accounts)are “open social systems” where the exchange of goods, labor, spouses, and information between two social realms is the order of the day. Implicitly, the anthropologists responsible for this interpretation seem to assume that these mutually beneficial exchanges discourage conflict and prevent war. The only exceptions allowed in this idyllic picture relate to frontiers shared with civilized Europeans. All other frontiers—whether static or moving, whether between cultures or language groups, whether between farmers and foragers or nomads and villagers—are represented as realms of exchange and cooperation.

Certainly, these scholars are correct in noting that even the sharpest boundaries between major cultural units seldom represent solid walls; rather, they resemble permeable tissues through which considerable exchange occurs. But due to three oversights, many anthropologists are excessively optimistic about the peacefulness of such places.

The first problem, discussed in Chapter 8, is that exchange is an inducement to or source of war and not a bulwark against it. Precisely because frontiers display things that people need or want (such as land, labor, spouses, and various commodities) just beyond the limits of their own social unit and beyond easy acquisition by the methods normal within their own society (such as sharing, balanced reciprocity, and redistribution by leaders), the temptation to gain Them by warfare is especially strong in these regions.

The second problem for the concept of peaceful frontiers is the fact that these regions necessarily lack the very social and cultural features that prevent disputes from turning violent. Independent societies have no overarching institutions of intersocietal mediation such as headmen, councils, and chiefs. Nor are there shared cultural values emphasizing group solidarity that treat bloodshed among fellow tribesmen or countrymen as especially horrifying and super-naturally disturbing. For example, God’s Sixth Commandment to the Israelites applied only to themselves, as their later treatment of the Canaanites demonstrated. Indeed, the Sixth Commandment is more honestly and precisely translated into English in the modern Jewish Torah as “Thou shall not murder,” since murder is the killing of a countryman, not the slaying of a foreigner in war. The social-solidarity values that oppose “us” to “them” help foment the collective violence of war from disputes between individuals of different societies. For this reason, much of the “information” exchanged across social boundaries and frontiers may be acrimonious and include uncomplimentary ethnic epithets (for example, “Filthy-Lodge People,” “Nit-heads” “Grey Feces,” “Spittle,” “Bastards,” “Ferocious Rats,” or the common and unambiguous “Enemies”).9 It is not just in movie Westerns that frontiers are regions of cultural antagonism where the legal and cultural constraints on violence are lax.

Finally, frontier areas tend to be less peaceful than the interiors of social and cultural domains because they are the most exposed to raids, the first to feel the effects of enemy depredations, and the most inclined to retaliate. Because they are usually less densely settled, easier to surprise, and easier to retreat from if resistance proves too great, border regions attract raids. The greater vulnerability and volatility of frontiers explain why they have often been buffered by no-man’s-lands and why their settlements have often been protected by fortifications.

There are three major kinds of cultural frontiers: civilized-tribal; pastoral nomad-village farmer; and farmer-forager. Because civilizations produce written records, the first type of frontier has been the object of some comparative studies.10 These comparisons indicate that although warfare between civilized and tribal peoples is not inevitable (as some examples prove), it has almost invariably occurred when a frontier involving a settlement or political control has moved. Very few pastoralist-farmer frontiers have been described that were not also part of primitive-civilized boundaries or from which warfare had been eliminated by the power of a state. And such frontiers seem to have been especially tense, even after pacification. Certainly, the few unpacified herder-farmer frontiers described ethnographically—for example, that between the aggressive Masai herdsmen of East Africa and their settled Bantu neighbors—appear to have been plagued by raiding and warfare.11 Because farmer-forager interactions have been the focus of considerable archaeological discussion, the ethnography and ethnohistory of such frontiers can be used to test the peaceful-frontier concept.

Anthropologists who consider uncivilized farmer-forager frontiers peaceful invariably use as examples the relationships commonly found between certain tropical-forest hunting peoples and their village farmer neighbors—especially the relationship between Pygmy hunters and Bantu (or other Negro) farmers in central Africa. But using this well-known example first of all requires discounting the Bantu’s claim that the Pygmies are actually their dependent subjects, literally serfs or “servants.”12 It also means overlooking the implications of the Pygmies’ occasional resort to crop theft when their Bantu “masters” are not forthcoming enough. Recent evidence on the diet of Pygmies indicates that they could not survive in the tropical forest without recourse to the substantial amounts of food (approximately 65 percent of their calories) they obtain from the agriculturalists.13 This dependency is further evidenced by the fact that no Pygmy groups speak their own language but only those of their Negro patrons. Under the circumstances, it is hardly surprising that Pygmies remain at peace and socially subordinate to the Bantu; to do otherwise would result either in starvation or in destruction at the hands of the more numerous Bantu. Most, if not all, supposedly benign farmer-forager relations in the tropical forests are predicated on a similar dietary dependence of the foragers and on the social subordination that follows from it.14

Any ethnographic evidence of frequent hostilities between farmers and foragers outside the tropical forests is dismissed by peaceful-frontier advocates as being a product of the disruptions that resulted from colonization by civilized peoples. This dismissal, like others of its ilk, is difficult to refute since all evidence of the hostilities comes from the supposed disrupters.

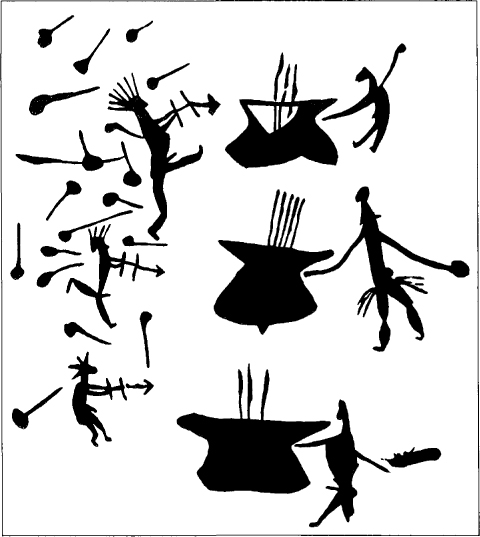

Yet it is difficult to dismiss the indications of frontier hostilities between the hunter-gatherers of southern Africa and their pastoral or farming neighbors.15 The pastoral Khoikhoi (Hottentots) of the Cape region of South Africa at first contact were already fighting with the San (Bushmen) hunter-gatherers, who were raiding their livestock. Initially, the Khoikhoi welcomed Europeans as allies in this struggle. The precontact provenance of these Khoikhoi-San hostilities is attested by rock paintings left by the San and by the derogatory Khoikhoi term San, which means something like “no-account rascal.” Moreover, when the Kalahari San of Botswana encountered expanding Bantu Tswana herders, the oral histories of both sides show that fighting and mutual raiding occurred. The Tswana term for the San was Masarwa, the Ma- prefix designating an enemy tribe (now softened by the Botswana government to Basarwa, using the Ba-prefix signifying friendly Bantu tribes). San hunter-gatherers in southeastern Africa fought with the neighboring Nguni Bantu tribes—again because of stock raiding. These San-Nguni conflicts are recorded in prehistoric San rock paintings (Figure 9.1) showing small-statured bowmen without shields (San) fighting large-statured warriors bearing shields, spears, and knobkerries (Nguni). In one early recorded incident, a Xhosa (Bantu) chief ordered his warriors to exterminate the local San because they had killed his favorite ox. In wars fought between rival Bantu tribes or clans, women and children were usually spared; but in raids on stock-stealing San bands, often all were slaughtered, without regard to sex or age. San bows and poisoned arrows fared very well in combat against Bantu shields, clubs, and spears, however, so extermination was not easy to accomplish. As a result, a certain balance of power was often established, especially in settings where rugged country gave the elusive San tactical advantages. In mountainous Lesotho, relations between the Sotho Bantu and the San were supposedly amiable until Sotho hunting with guns made game scarce and San stock raiding created conflicts. In all these cases, the dynamic behind this farmer-forager warfare was the same: Khoikhoi or Bantu retaliation for San livestock raiding, which itself was often predicated on or exacerbated by game shortages created by the hunting of the farmer-herders and by the ecological transformations induced by tillage and grazing. This hostile dynamic was finally transformed when the better-armed and horse-mounted Boers arrived on the scene. They, like the Nguni and Khoikhoi, found that The San were difficult to subdue because of their poisoned arrows and the mobility of their small bands. Indeed, the hostility of the San in the Sneeuwburg Mountains halted the expansion of the Trekboers in the northeastern Cape for thirty years and even forced the frontier back in some areas. In the end, though, when the Boers became numerous enough, their commandos (militia) simply exterminated the San.

Figure 9.1 Prehistoric rock painting showing battle between San foragers on the left and Bantu farmers on the right. The San are armed only with bows, whereas the Bantu carry oxhide shields and spears (held in reserve behind the shield) and wield knobkerries (a wooden club that could be thrown). The tadpole shapes around the San bowmen may represent thrown knobkerries. (Redrawn from Wilson and Thompson 1983)

In none of these cases were hostilities incessant, even after Europeans appeared on the scene; in fact, there is plentiful evidence of trade, intermarriage, and the incorporation of individual San as “clients” or serfs by the Khoikhoi and Bantu tribes. However, being the clients of one Khoikhoi tribe did not prevent San bands from raiding other Khoikhoi groups, so clientship did not necessarily eliminate farmer-forager hostilities.

In recent descriptions of these patron-client relationships between farmer-herders and foragers by historians and anthropologists, the arrangement is depicted as benign, voluntary, and mutually beneficial. But a description of San clientship by a Bantu Tswana chief has a very different tenor:

The Masarwa [that is, the San] are slaves. They can be killed. It is no crime. They are like cattle. If they run away, their masters can bring them back and do what they like in the way of punishment. They are never paid. If the Masarwa live in the veld, and I want any to work for me, I go out and take any I want.16

This quotation raises questions about another dynamic recognized by advocates of peaceful frontiers. Proponents of this theory argue that farmers and herders on thinly settled frontiers often experience labor shortages that can be intense at certain seasons (such as during the harvest) and that it was convenient for them to enlist the temporary help of the local foragers in exchange for surplus food. The Tswana chiefs description implies that it can be just as convenient for the more numerous farmers to conscript foragers by force, keep them as involuntary servants, and “pay” them bare subsistence. For the farmers, this version of farmer-forager symbiosis has the additional advantage of simultaneously eliminating potential stock rustlers and crop thieves. In an account of the first contact between his tribe and the !Kung San, a Tswana claimed that the San accepted a servile status out of fear of the Tswana and that, had these San resisted, the Tswana “would have slaughtered them.”17

But the San were not the only hunter-gatherers to harass village farmers, nor was stock theft the only torment raiders inflicted. Both foragers and pastoralists showed a propensity for stealing crops as well as livestock from settled farmers (although, when there was a choice, livestock seems to have been the preferred booty, probably because it can be taken away under its own power).18 Such thefts, however, were seldom accomplished without combat or inciting retaliatory raids. One old story among the Navajo is that the first time they ever heard this name applied to them (they call themselves Diné, or “people”) was when one band was robbing a Tewa Pueblo cornfield; the victims shouted “Navaho” when the thieves were discovered. Among the Western Apaches of Arizona, when the meat supply of a band began to run low, an older woman would complain publicly and suggest that a raid be mounted to obtain a fresh supply. The band leader would then call for volunteers, and a small party of no more than fifteen warriors would set off for an enemy settlement. Moving as unobtrusively as possible, they would attempt to drive off some of the enemy’s herds and then beat a very rapid retreat back home. The party would fight if it was caught, but it tried to avoid any contact; the object was simply to obtain food, not to inflict damage. If any raiders were killed or the victims retaliated by killing a band member, a much larger war party—up to 200 warriors—would depart, surround the offending settlement, and kill as many of its inhabitants as possible. Similarly, the Mura of central Brazil preferred to raid neighboring sedentary farmers for manioc and other crops rather than cultivate these themselves. Since pastoral and foraging groups were usually highly mobile and had such large territories to hide in, they were very difficult to catch, either to reclaim lost goods or to exact retribution. To note that foraging or pastoral nomads made exasperating adversaries for settled farmers is an understatement; to claim that They were almost never enemies is wishful thinking.

While static frontiers were often hostile, moving ones presented an even greater potential for violent conflicts, since they added further explosives to an already volatile mix. A moving cultural boundary meant that one human physical type, language, culture, or economic system was expanding at the expense of another. Of course, such spreads were sometimes accomplished through the , peaceful mechanisms of intermarriage, willing adoption of novelties, and voluntary annexation. But people tend to be attached to their traditional way of life, territory, and political independence and are seldom completely defenseless; consequently, warfare often accompanies the movement of a frontier and occasionally may be the only mechanism by which it can advance. When the movement of a frontier involves colonization by newcomers on a large scale, conditions favoring warfare reach their peak. The newcomers are at least intruding, if not trespassing; often compete with the natives for land, water, game, firewood, and other limited materials; commonly change the local ecology; are inclined to be cavalier about the property rights of the other but are fastidious about their own; and exhibit inscrutably odd customs and tastes. It is seldom long before the colonists’ behavior convinces the aborigines that the newcomers should be encouraged to be “new” someplace else. This type of moving colonist frontier is documented historically only for literate civilizations; all others are the province of archaeologists and are subject to the vagaries of their interpretive fashions. The advance and retreat of most (but not all) of these civilized settler frontiers have been accompanied by frequent warfare, as between the Romans and the Celts or Germans in western Europe, the late medieval Spanish and the Gaunche tribesmen of the Canary Islands, the medieval Japanese and Ainu tribesmen on Honshū, the modern Japanese and the Taiwanese Aborigines, and the modern Europeans and almost everyone else.19

Comparable prehistoric frontiers do give evidence that violence was common or at least expected.20 The conflicts already in existence at the dawn of historical records between the Khoikhoi or Bantu and the San in southern Africa and between the Navaho—Apache and the Pueblos in the American Southwest have already been mentioned. In eastern North America, the intrusion of Mississippian peoples into various regions between A.D. 900 and 1400 was marked by the fortification of almost all new settlements in these areas. The retreat of these Mississippians from northeastern Illinois in the face of the expansion of Oneota settlements was marked by a high level of violent death and fortified villages. A concentration of fortified settlements and The horrific Crow Creek massacre occurred on or near a fluctuating frontier between Middle Missouri (proto-Mandan) and Coalescent (proto-Arikara) farmers between A.D. 1300 and 1500. The abandonment of some areas in northwestern New Mexico by Anasazi farmers between A.D. 1050 and 1300 was immediately preceded by frequent fortification and destruction of settlements as well as other indications of violence. There is also considerable indication of violence on the periphery of the shrinking area of Hohokam occupation in Arizona during this same period. Hostile frontiers, then, are not unusual in the later prehistory of the best-studied regions of North America.

Far earlier in western Europe, some 7,000 to 6,000 years ago, colonizing Early Neolithic farmers appear to have encountered, or expected to encounter, a hostile reception from the indigenous Mesolithic hunter-gatherers.21 The farmers of the Impressed Ware (or Cardial) culture founded settlements at favorable locations along the Mediterranean coasts and often fortified these sites with ditches. The local foragers, whose sites were less substantial and unfortified, adopted (perhaps by looting) ceramics and livestock from these settlers. At one Cardial site in southern France, archaeologists found a few skulls with cut-marks from decapitation. These skulls differed in physical type from that of the Cardial farmers, but resembled the type of Mesolithic foragers farther to the north. It therefore appears that the Cardial farmers at least occasionally killed foragers and kept their heads as trophies. The colonization of Germany and the Low Countries by farmers of the Linear Pottery culture was accompanied by fortified border villages (Figure 9.2) and, in Belgium at least, a 20- to 30-kilometer (12- to 18-mile) no-man’s-land between these defended sites and the settlements of Final Mesolithic foragers (Figure 9.3). In one of these border villages, most of the houses had been burned, after which the village was fortified. As the trophy heads at Ofnet and the mass grave at Talheim demonstrate, neither the indigenous foragers nor the invading Linear Pottery farmers were peaceful among themselves; thus it is unlikely that they treated each other less violently. Because human remains from this period and area are extremely rare (the soils did not preserve them well), no direct evidence yet exists of farmers killed with Mesolithic weapons or vice versa. Nevertheless, the fortification of pioneer and border settlements does imply that hostilities were expected on these earliest European farmer-forager frontiers. From both the Old World and the New World, evidence suggests that prehistoric frontiers, like more recent examples, were far from placid.

Figure 9.2 Distribution of LBK or Linear Pottery (Early Neolithic) enclosures relative to the limits of LBK expansion at two stages. The frontier distribution of the Most Ancient enclosures is very clear, while the pattern for the Early and Late periods is less clear because two periods are combined. (Hockmann 1990; drawn by Ray Brod, Department of Geography, University of Illinois at Chicago)

In a recent cross-cultural study of the circumstances surrounding preindustrial warfare, Carol and Melvin Ember noted that the nonindustrial societies most frequently embroiled in warfare were those that “have had a history of expectable but unpredictable disasters” (droughts, floods, insect infestations, and so on).22 These disasters do not include anticipatable chronic food shortages, such as the “hungry season” endured by many hunter-gatherers and subsistence farmers in higher latitudes during the late winter and early spring. The clear implication is that the most war-prone groups go to war to recoup losses due to natural calamities, to replace deteriorating pastures and fields by means of territorial expansion, and to cushion the effects of expected future losses.

Figure 9.3 Distribution of LBK or Linear Pottery farming settlements versus Final Mesolithic foragers campsites, ca. 5000 B.C., in northeastern Belgium. Notice the no-man’s-land to the north where no major geographical barrier (such as the deep valley of the Meuse) intervenes. (Redrawn after Keeley and Cahen 1989 by Ray Brod, Department of Geography, University of Illinois at Chicago)

Droughts figure frequently in examples of disaster-driven warfare.23 The various nomadic raiders who preyed on the Pueblos of the American Southwest were especially active during dry years. As noted earlier, the Hopi anticipated trading rather than raiding from approaching Apaches only if (rare) rain clouds were visible in the direction from which the Apaches were approaching. Offensive raiding by the Maricopa of Arizona was associated with low-water stages on the Colorado and Gila rivers. A similar correlation with dry spells is attested for the raids of Libyan and Asiatic Bedouin pastoralists on the Faiyum and Nile Delta frontiers of ancient Egypt. The increase in fighting among South African Bantu tribes in the early nineteenth century seems to have resulted in part from years of decreasing rainfall following forty years of better conditions during which both human and cattle populations had increased. The coincident emergence and expansion of the Zulu state under such overcrowded conditions set off a confused and sanguinary period of forced migrations by marauding bands of refugees known as the Mfecane. A similarly bellicose time of troubles, accompanied by political consolidation, apparently occurred in parts of the American Southwest during a long drought in the twelfth century.24 It is hardly surprising that—seeing their crops wither, their herds dwindle, and their families go hungry—men would fight to obtain means of subsistence from someone else. During the warfare and attendant suffering of the Bantu Mfecane and various prehistoric southwestern droughts, some desperate people were apparently even driven to cannibalism.25

In fact, it is becoming increasingly certain that many prehistoric cases of intensive warfare in various regions corresponded with hard times created by ecological and climatic changes.26 The extreme violence noted in South Dakota just after A.D. 1300 follows a late-thirteenth-century climate change that caused the migration of Coalescent farmers from the west-central Plains into the region occupied by Middle Missouri villagers. The bones of the slaughtered Coalescent villagers at Crow Creek bore evidence that the villagers had been ill-nourished for a prolonged period before their deaths. Judging from the proportion of skeletons with embedded projectile points, the most violent periods in the later prehistory of the Santa Barbara Channel region in California are related to “warm-water events” that disrupted the productivity of coastal waters and caused widespread dietary deficiencies. Certain pathologies (such as ricketts) possibly related to inadequate diet were also common in the Late Paleolithic Qadan cemeteries, including the often-mentioned one at Gebel Sahaba.

No type of economy or social organization is immune to natural disasters or to the impetus they give to warfare; foragers, farmers, bands, and states all can suffer them. Because of their smaller territories, slimmer subsistence margins, and more limited transportation systems, however, smaller-scale societies are more susceptible to injury from these disasters than are large states and empires. In the latter, a famine in one area can be ameliorated with supplies transported from more favored areas or taken from centralized food reserves. In a small society, the needed supplies may be too distant for practical transportation by human, animal, or canoe. Moreover, these supplements must be obtained by trade with outsiders who may not be particularly charitable, and trade itself (as we have seen) is a rich source of incitements to war. It should be said that larger, denser, and more technically sophisticated societies have a greater capacity to create their own disasters through deforestation, overgrazing, soil salinization, the introduction of new pests, and even foolish economic policies. But whatever their source, hard times create a very strong temptation for needy people to take—or try to take—what they lack from others.

What makes disaster-driven warfare especially bitter is that the defenders, while usually somewhat better off than the attackers, commonly are suffering to some degree from the same natural adversities. In such dire circumstances, any group that yields an acre of land or a bushel of corn may risk its own survival; war does become a struggle for existence. Of course, not all wars occur under these conditions, and sometimes people are simply too weakened by famine to fight. But natural disasters are clearly predicaments that increase the frequency and intensity of war.