In March 1993, peasants digging a fishpond in the village of Wangjiatai 王家台 in Hubei province exposed a group of sixteen ancient tombs. This village is in the very heartland of the ancient state of Chu 楚, which was the largest and one of the most powerful states of China for several centuries in the first millennium B.C., controlling most of what is now central China. Wangjiatai is about three miles to the south of the site of Jinan Cheng 紀南城, the longtime capital of Chu, and just half a mile north of the site of Ying 郢, established in the years after 278 B.C., when Jinan Cheng was conquered and razed by the increasingly powerful northwestern state of Qin. Over the course of the past several decades, hundreds of tombs from the fourth and third centuries B.C. have been discovered scattered outside these capitals, and residents of the area are well familiar with archaeological discoveries. The peasants immediately summoned archaeologists from the nearby Jingzhou 荊州 Museum to conduct a salvage excavation of the tombs at Wangjiatai. In one of them, numbered M15, a relatively small tomb (2.9 m x 1.8 m at the mouth, just 2.3 m x 1.2 m at the bottom), the archaeologists found inside its single coffin a wooden diviner’s board, bamboo sorting stalks placed in a bamboo canister, a number of dice, the haft of a daggeraxe, and, perhaps most important of all, a heap of bamboo strips with writing on them.1 The predominant style of writing on these bamboo strips as well as features of the associated grave goods found in the tomb allowed the archaeologists to date the tomb to the mid-third century B.C.,2 after the initial Qin conquest of the area but prior to the Qin unification of all the independent states. The contents of the tomb also suggested to them that the deceased had been a diviner, a relatively low-ranking official responsible for determining the outcome of future events. This identification was made in large part because the writing on the bamboo strips would eventually reveal, among other texts, one of the most important divination manuals from ancient China, the Gui cang 歸藏, or Returning to Be Stored, a text that fully deserves comparison with the better-known Zhou Yi.

The archaeologists lifted the entire coffin section out of the tomb in a single block and took it back to their research station at the museum. There they took more than eight hundred fragments of bamboo strips out of the mud,3 preserving them in distilled water. Because the strips were coated with mud, the archaeologists and museum staff subjected them to a weak vinegar bath until the mud began to dissolve, and then cleaned them with a soft brush, until the written characters could be read. They found that even though the bamboo strips had become thoroughly jumbled during their more than twenty-two hundred years in the tomb, they could be divided into five discrete types of texts: a daybook (rishu 日書), which, as mentioned in chapter 1, is a sort of almanac that has been found in a great number of ancient tombs from throughout the fourth through second centuries B.C. and from all over China;4 a legal code containing rules for the pricing of merchandise and regulations for scales (referred to as Xiao lü 效律);5 a text that the archaeologists refer to as Zheng shi zhi chang 政事之常, or The Norms of Government Service, written in the form of a chart with the title in the middle surrounded by three concentric squares of text, each quadrant of which elaborates the significance of the quadrant inside it;6 a Zai yi zhan 災異占, or Prognostications of Disasters and Anomalies, which is very similar to the “Wu xing zhi” 五行志, or “Record of the Five Phases,” chapters in early dynastic histories;7 and two copies, apparently similar in content though written on bamboo strips of different sizes, of a text first referred to simply as a Yi jing–like divination text but subsequently identified as the long-lost Gui cang 歸藏,8 traditionally supposed to have been the milfoil divination manual of the Shang dynasty and thus a precursor to the Zhou Yi. This last text has attracted considerable interest from the scholarly community.

In a later section of this study, I provide a detailed analysis of the entire contents of these two copies of the Gui cang, insofar as we can know of them at the present time, and in the following chapter I provide a translation of all the transcriptions that have been published to date, as well as quotations of the text preserved in medieval sources. For the moment, I quote just two fragments in order to illustrate the nature of at least a significant portion of the texts. The first is number 194; the second one is unnumbered.9

Jie “Moderation” says: In the past King Wu divined about attacking Yin and had the stalks prognosticated by Lao Qi.10 Lao Qi prognosticated and said: Auspicious …

Jie “Moderation” says: In the past King Wu divined about attacking Yin and had the stalks prognosticated by Lao Qi.10 Lao Qi prognosticated and said: Auspicious …

明夷曰昔者夏后启卜乘飞龙以登于天而攴占□□

明夷曰昔者夏后启卜乘飞龙以登于天而攴占□□

Ming Yi “Brightness Obscured” says: In the past Xia Hou Qi divined about flying on a dragon to rise into heaven and had the stalks prognosticated .. .. …

Ming Yi “Brightness Obscured” says: In the past Xia Hou Qi divined about flying on a dragon to rise into heaven and had the stalks prognosticated .. .. …

As seems to be normative in the text, these fragments begin with a hexagram picture, with the yin lines written as ∧ and the yang lines as ━. Here, the hexagram picture  , that is,

, that is,  , corresponds with the hexagram known in the Yi jing tradition as Jie 節 (i.e., 节, “Moderation”), whereas that of

, corresponds with the hexagram known in the Yi jing tradition as Jie 節 (i.e., 节, “Moderation”), whereas that of  , that is,

, that is,  , corresponds with Ming Yi 明夷 (usually understood as “Brightness Obscured”), and these are the names given to the hexagrams here as well (as will be seen, this is not always the case). After the hexagram picture and the hexagram name, there then follows the text proper of the hexagram statement. In many cases, as in both cases here, this text reports a divination performed upon the occasion of some important event in early Chinese history or mythology. Here, the first records a divination by King Wu of Zhou proposing to attack Yin or Shang, and the second concerns a divination by Qi 启 (i.e., 啓), the first king of the Xia dynasty, proposing to fly on a dragon to ascend into heaven. The divinations were then prognosticated by someone, often a legendary figure known from ancient times; in the case of the first fragment here, the prognosticator is someone named Lao Qi 老

, corresponds with Ming Yi 明夷 (usually understood as “Brightness Obscured”), and these are the names given to the hexagrams here as well (as will be seen, this is not always the case). After the hexagram picture and the hexagram name, there then follows the text proper of the hexagram statement. In many cases, as in both cases here, this text reports a divination performed upon the occasion of some important event in early Chinese history or mythology. Here, the first records a divination by King Wu of Zhou proposing to attack Yin or Shang, and the second concerns a divination by Qi 启 (i.e., 啓), the first king of the Xia dynasty, proposing to fly on a dragon to ascend into heaven. The divinations were then prognosticated by someone, often a legendary figure known from ancient times; in the case of the first fragment here, the prognosticator is someone named Lao Qi 老 , who announces the prognostication “auspicious” (more often in this text, the prognostication is “not auspicious”). As will become evident later in this study, in other fragments this prognostication is followed by a rhyming oracle, more or less similar to line statements of the Zhou Yi.

, who announces the prognostication “auspicious” (more often in this text, the prognostication is “not auspicious”). As will become evident later in this study, in other fragments this prognostication is followed by a rhyming oracle, more or less similar to line statements of the Zhou Yi.

What makes these texts particularly fascinating is that they match to a very considerable extent quotations in early medieval texts, for the most part attributed to the Gui cang. In the case of the two fragments quoted above, we have almost exact matches. The first, unattributed, was first found in the Bo wu zhi 博物志, or Record of Things at Large, of Zhang Hua 張華 (232–300), and the second in the commentary by Guo Pu 郭璞 (276–324) to the Shan hai jing 山海經, or Classic of Mountains and Seas.

武王伐殷而牧占耆老耆老曰吉

Wu Wang attacked Yin and [shepherded:] had the stalks prognosticated by Qi Lao. Qi Lao said: Auspicious.11

歸藏鄭母經曰夏后啟筮御飛龍登于天吉

The “Zheng mu jing” of the Gui cang says: “Xia Hou Qi divined by milfoil about driving a flying dragon to rise into heaven: Auspicious.”12

Although the full text of the Gui cang has long been lost, Qing-dynasty scholars reconstituted it to some extent on the basis of these medieval quotations.13 Nevertheless, even this reconstituted text was generally neglected or, worse, regarded as a late forgery. Now, with the discovery of the Wangjiatai bamboo strips, it is clear that the Gui cang, if indeed this is the name that should be given to this text,14 is not only an authentic pre-Qin text but was also an important alternative to the Zhou Yi in interpreting the results of milfoil divination.15

The Gui Cang: Textual History

The earliest mention of the Gui cang comes in the “Tai bu” 大卜 (Great Diviner) section of the “Zong bo” 宗伯 (Elder of the Ancestral Temple) chapter of the Zhou li 周禮, or Rites of Zhou. It states simply,

[大卜]掌三易之法一曰連山二曰歸藏三曰周易其經卦皆八其别皆六十有四

(The great diviner) is in charge of the methods of the three Changes; the first is called Lian shan [Linked Mountains], the second is called Gui cang [Returning to Be Stored], and the third is called Zhou Yi [Zhou Changes]; in all three cases their prime trigrams are eight, and their derivative hexagrams are sixty-four.16

Throughout the Eastern Han period, a few prominent scholars mentioned the Gui cang in very general, and sometimes contradictory, terms, presumably prompted by this mention in the Zhou li. Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 (A.D. 127–200), probably the most erudite scholar of the period, seems to state that the book was available at his time.17 At other places, both Wang Chong 王充 (A.D. 27–ca. 100) and Zheng Xuan associated the Lian shan 連山 with the Xia dynasty and the Gui cang with the Shang, a natural “Three Dynasties” deduction based on the presumed Zhou-dynasty origins of the Zhou Yi (often understood to mean Changes of the Zhou Dynasty), but neither seems to have been very confident of these attributions.18 In his typical fashion, Wang Chong ridiculed contemporary scholars, pointing out that they could not even explain the origins of the Yi jing.

先問易家易本何所起造作之者為誰彼將應曰伏羲作八卦文王演為六十四孔子作彖象繫辭三聖重業易乃具足問之曰易有三家一曰連山二曰歸藏三曰周易伏羲所作文王所造連山乎歸藏周易也

Let us first ask the experts on the Changes: “How did the Changes first come about; who was it that created it?” They would then respond: “Fuxi made the eight trigrams, King Wen expanded them into sixty-four, and Confucius made the Judgment, Image, and Appended Statements commentaries. Through the combined effort of the three sages, the Changes was then complete.” But if you ask them, “There are three schools of the Changes, the first called Lian shan, the second called Gui cang, and the third Zhou Yi. Was what Fuxi made and King Wen expanded the Lian shan? What about the Gui cang and Zhou Yi?”19

The only more specific information concerning the Lian shan and Gui cang comes from the Xin lun 新論 of Huan Tan 桓譚 (ca. 43 B.C.–A.D. 28), saying that the Lian shan was stored in the Orchid Terrace (Lantai 蘭台) and included eighty thousand characters, and the Gui cang was stored with the Grand Diviner (Tai bu 太卜) and included the perhaps more believable total of forty-three hundred characters.20 Despite the precision of these locations and numbers, they are open to question. Huan Tan was a high official during the period that Wang Mang 王莽 was in power (A.D. 8–25), the only time that he would have had access to the Orchid Terrace and Grand Diviner libraries. Just before this time, his contemporaries Liu Xiang 劉向 (79–8 B.C.) and Liu Xin 劉歆 (46 B.C.–A.D. 23) were charged with organizing the imperial library. Notably, they did not include either the Lian shan or Gui cang in their catalogue, Qi lüe 七略, nor were these two texts included in the subsequent “Yi wen zhi” 藝文志 bibliographic monograph of the Han shu 漢書, or History of the Han Dynasty, which was based on the Qi lüe. Moreover, throughout the entirety of the Han dynasty, and indeed until early in the fourth century, there is not a single explicit quotation of either of these texts extant.21 As late as 282, there is some evidence to suggest that even Du Yu 杜預 (A.D. 224–284), the great commentator of the Chun qiu 春秋, or Spring and Autumn (Annals), and Zuo zhuan 左傳, or Mr. Zuo’s Tradition, had never seen the Gui cang.22

The next official bibliography, the “Jing ji zhi” 經籍志 of the Sui shu 隋書, or History of the Sui, compiled by Wei Zheng 魏徵 (A.D. 580–643), mentions the Gui cang twice.23 The first of these mentions is rather ambiguous concerning the contemporary status of the book:

歸藏漢初已亡案晉中經有之

The Gui cang was already lost at the beginning of the Han dynasty. The Central Classics of the Jin dynasty has/had it.

The Zhong jing 中經, or Central Classics, of the Jin dynasty, first completed in the 270s under the editorship of Xun Xu 荀勖 (d. 289), with the assistance of Zhang Hua, and then added to in the 280s, was a massive compendium with fair copies of all the texts in the imperial library. It established the four-part division of Chinese literature that remained normative thereafter: classics (jing 經), philosophers (zi 子), histories (shi 史), and belles lettres (ji 集). Unfortunately, much of this compendium was lost in the civil wars at the end of the Western Jin dynasty (in 304 and especially in 310);24 it is not clear whether this mention in the “Jing ji zhi” of the Sui shu was based on an existing copy of the Zhong jing text of the Gui cang or, as is perhaps more likely, on a listing of the contents of the Zhong jing or some other sort of secondary reference. The second record is less ambiguous, citing a text of the Gui cang in thirteen scrolls, with a commentary by one Xue Zhen 薛貞, identified as a general (Taiwei can jun 太尉参軍) of the Jin dynasty.25 Although I can find no other mention of this figure, given the completion of the Zhong jing shortly after the establishment of the Jin dynasty it seems likely that his commentary must have been based on the Zhong jing text.

It seems likely too that the Zhong jing text of the Gui cang was based on a bamboo-strip text discovered in a tomb in A.D. 279—the Jizhong 汲塚 tomb of Zhushu jinian 竹書紀年 (Bamboo Annals) and Mu tianzi zhuan 穆天子傳 (Biography of Son of Heaven Mu) renown. When the “tens of cartloads” of bamboo strips found in this tomb were transported to the capital at Luoyang 洛陽, the emperor, Jin Wudi 晉武帝 (r. 265–289), commanded Xun Xu, the director of the imperial library and the editor of the just completed Zhong jing, to lead a committee to put these texts in order. Among the texts found in the tomb were several divination texts, including an apparently complete manuscript of the hexagram and line statements of the Yi jing. The inventory of these texts included in the extant biography of Shu Xi 束皙 (261–300), a later editor of the Jizhong texts and perhaps the last person to work with the original bamboo strips, includes the following mention of one of these texts:

易繇陰陽卦二篇與周易略同繇辭則異

Yin Yang Hexagrams of the Lines of the Changes, in two bundles, rather similar with the Zhou Changes but with different line statements.26

An earlier biography of Shu Xi, written by Wang Yin 王隱 (284–354), seems to describe this same text but somewhat differently, stating, “Among the ancient texts there were hexagrams of the Changes, similar to the Lianshan and Gui cang” (Gu shu you Yi gua, si Lian shan Gui cang 古書有易卦似連山歸藏).27 At just about the time that Wang Yin was writing this,28 the first explicit quotations of the Gui cang begin to appear in extant literature. These are found in the commentaries to ancient literature written by Guo Pu. For instance, with respect to a reference to Qi 啟, the first ruler of the Xia dynasty, in the Shan hai jing, Guo Pu’s commentary, completed after A.D. 321, reads,

歸藏鄭母經曰夏侯啟筮御飛龍登于天吉明啟亦仙也

The “Zheng mu jing” of the Gui cang says: “Xia Hou Qi divined by milfoil about driving a flying dragon to rise into heaven: Auspicious. This shows that Qi was also an immortal.”29

A few decades before Guo Pu composed his commentaries, quotations similar to this were included in Zhang Hua’s Bo wu zhi:

武王伐殷而牧占耆老耆老曰吉桀莖伐唐而牧占營惑曰不吉

Wu Wang attacked Yin and [shepherded:] had the stalks prognosticated by Qi Lao. Qi Lao said: Auspicious. Jie [Jing:] divined by milfoil about attacking Tang and [shepherded:] had the stalks prognosticated by Ying Huo, who said: Not auspicious.30

The Bo wu zhi, probably the most famous literary compilation of its age, was presented to Jin Wudi late in his life, probably in the late 280s. Although Zhang Hua had not participated in the editing of the Jizhong bamboo-strip texts that had been taking place in the years immediately before this, he was in the capital by about 285 and doubtless had some access to the transcriptions; indeed, the Bo wu zhi includes quotations that could have come only from these texts.31 What is more, as Wang Mingqin, the editor of the Wangjiatai texts has shown, these Bo wu zhi quotations include transcription errors that could have come only from misinterpretations of archaic manuscripts. Some suggestion of this is seen even in the quotations above, with mu 牧, “to shepherd,” and jing 莖, “shaft,” obvious mistranscriptions of mei 枚, “(bamboo) stalk,” and shi 筮, “to divine (by milfoil).”32

As several scholars have argued in recent years, all this shows quite convincingly that the Gui cang, or at least a text that was subsequently identified by that name, was among the texts unearthed from the Jizhong tomb.33 In the centuries after Zhang Hua and Guo Pu first quoted it, many more passages of the text were quoted, especially in the encyclopedias that were popular in the Tang and Northern Song dynasties. For example, the Taiping yulan 太平御覽, or Imperial Conspectus of the Great Peace Reign Era, includes at least nineteen explicit quotations of the Gui cang, as well as a few other mentions of the text and at least one misattributed quotation.34 The edition and commentary of Xue Zhen is still listed as being in thirteen scrolls as late as the “Yi wen zhi” 藝文志 bibliographic treatise of the Jiu Tang shu 舊唐書, or Older History of the Tang Dynasty (compiled in 945).35 However, later bibliographies of the Northern Song dynasty, such as the Zhongxing guange shumu 中興館閣書目 (of 1178) and the “Yi wen zhi” of the Song shi 宋史, or History of the Song Dynasty, suggest that the text was by then much attenuated, listing it as being extant in three scrolls.36 Contemporary sources indicate that these three scrolls were named: “Qi mu jing” 齊母經, “Chu jing” 初經, and “Ben shi” 本蓍.37 However, not only are these names never mentioned in pre-Song sources but also the quotations attributed to them in later sources are invariably anomalous within the Gui cang tradition. Perhaps more important, not one of these quotations is at all similar to anything in the Wangjiatai manuscripts. It would seem that by then the Gui cang had been mostly lost, and that these three scrolls, whatever their origin may have been, were substituted for it.

Thus, it is not strange that during the Song dynasty scholars began to express doubts about the authenticity of the Gui cang. Ouyang Xiu 歐陽修 (1007–1072) had this to say about the text extant in the Northern Song:

周之末世夏商之易已亡漢初雖有歸藏已非古經今書三篇莫可究矣

By the end of the Zhou, the Changes of the Xia and Shang were already lost. Although at the beginning of the Han there was the Gui cang, it already was not the ancient classic. There is nothing that can be found of it in the present text in three scrolls.38

It is possible that some portion of the text remained available for quotation. As noted above (n. 11), the Lu shi 路史, or Revealed History, of Luo Ping 羅萍 and Luo Bi 羅秘, completed in 1170, includes several passages attributed to the Gui cang, including one description of the contents of the text, though both this description and some of the quotations suggest that the text was either badly garbled or badly understood by the Luos.39 After this time, there is no evidence that the text survived in any form at all until scholars in the Qing period reconstituted it on the basis of quotations in earlier literature.40 Even then, what little attention these reconstituted texts attracted from scholars was for the most part to argue that the Gui cang was a medieval forgery.41

The Wangjiatai Gui Cang Texts: Physical Considerations

Although the bamboo strips of the Wangjiatai texts have developed a moldy covering that has prevented the Jingzhou Museum from making formal photographs and none of the texts has yet been fully published, nevertheless enough details about the Gui cang text have been provided to demonstrate that this is indeed a remarkably important discovery. According to the detailed overview of the discovery by the museum’s Wang Mingqin, the scholar responsible for the editing of the texts, 394 fragments have been identified as belonging to the two copies of the Gui cang, 164 of them numbered and 230 unnumbered.42 Unfortunately, according to Wang Mingqin, no single bamboo strip of this text has survived intact,43 and it has apparently not been possible to reconstruct a single complete strip. Wang states that the longest fragment has twenty-eight characters, though his transcription includes one strip, no. 213, with thirty-five characters as well as a hexagram picture and a duplication mark, and two others with more than thirty characters (no. 302 with thirty-one, and no. 560 with thirty-two). Another strip, no. 214, has twenty-nine transcribed graphs, as well as a space for one unreadable graph, the hexagram picture, three duplication marks, and a final  or 乙-shaped mark, usually indicative in these manuscripts of the end of a section or text. This would seem to suggest that this latter strip, which carries the hexagram picture and text of Zi 鼒, “The Small-Mouthed Cauldron,” hexagram (equivalent to Ding 鼎, “Cauldron,” hexagram in the Zhou Yi tradition), is complete, at least in terms of the text on it. This perhaps also suggests that, as in the case of the Shanghai Museum bamboo-strip manuscript of the Zhou Yi, each hexagram text began at the top of a new bamboo strip.44 Since the Gui cang hexagram texts are relatively short, it should have been possible in most cases to copy each such text on a single bamboo strip.

or 乙-shaped mark, usually indicative in these manuscripts of the end of a section or text. This would seem to suggest that this latter strip, which carries the hexagram picture and text of Zi 鼒, “The Small-Mouthed Cauldron,” hexagram (equivalent to Ding 鼎, “Cauldron,” hexagram in the Zhou Yi tradition), is complete, at least in terms of the text on it. This perhaps also suggests that, as in the case of the Shanghai Museum bamboo-strip manuscript of the Zhou Yi, each hexagram text began at the top of a new bamboo strip.44 Since the Gui cang hexagram texts are relatively short, it should have been possible in most cases to copy each such text on a single bamboo strip.

The two copies of the Gui cang text are differentiated by the width and thickness of the bamboo strips, one set being relatively wide and thin and the other narrower but thicker. Unfortunately, the partial transcriptions published to date provide no indication which strips belong to which text. Wang Mingqin mentions redundancies among the hexagram pictures (the fragments include a total of seventy hexagram pictures, sixteen of them duplicates, giving a total of fifty-four different hexagram pictures)45 and the hexagram names (there are seventy-six in all, with twenty-three redundancies, for a total of fifty-three different hexagram names).46 In a few cases, it is possible to compare two different versions of the same hexagram text.47

比曰比之荣

比曰比之荣 比之苍

比之苍 生子二人或司阴司阳不□姓□

生子二人或司阴司阳不□姓□ (216)

(216)Bi “Alliance48” says: Ally with them so lush, ally with them so green. Giving birth to two sons, one in charge of shade and one in charge of sunlight, not .. surname .. …

[卒]曰昔者□卜出云而攴占□

[卒]曰昔者□卜出云而攴占□

[Zu “Complete”] says: In the past .. divined about exiting the clouds, and had the stalks prognosticated .. …

[Zu “Complete”] says: In the past .. divined about exiting the clouds, and had the stalks prognosticated .. …

.. Zu “Complete” says: In the past Xian divined about exiting the clouds, and had the stalks prognosticated by Qun Jing. Qun Jing prognosticated them and said: Not auspicious. Complete …

[咸]曰

[咸]曰

[Xian “Feeling”] says …

[Xian “Feeling”] says …

□咸曰

.. Xian “Feeling” says …

Jin “Jin” says: In the past … … divined about making offering to Di at Jin’s Mound, to make it into .. …

Jin “Jin” says: In the past … … divined about making offering to Di at Jin’s Mound, to make it into .. …

[Jin “Jin”] says: In the past Xia Hou Qi divined about making offering at Jin …

亦曰昔者北□

亦曰昔者北□ (343)

(343) Ye “Night49” says: In the past Bei .. …

Ye “Night49” says: In the past Bei .. …

Ye “Night” says: In the past Great Officer Bei .. divined about welcoming Nü …

Ye “Night” says: In the past Great Officer Bei .. divined about welcoming Nü …

大□曰昔者

大□曰昔者 (408)

(408)  隆卜将云雨而攴占囷

隆卜将云雨而攴占囷 京

京 占之曰吉大山之云

占之曰吉大山之云

(196)

(196) Da .. “Greater [Strength]” says: In the past … … Long divined about leading the clouds and rain and had the stalks prognosticated by Qun Jing. Qun Jing prognosticated them and said: Auspicious. The great mountain’s clouds, [?] …

Da .. “Greater [Strength]” says: In the past … … Long divined about leading the clouds and rain and had the stalks prognosticated by Qun Jing. Qun Jing prognosticated them and said: Auspicious. The great mountain’s clouds, [?] …

壮曰昔者丰隆

壮曰昔者丰隆 (320)

(320) Zhuang “Strength” says: In the past Feng Long …

Zhuang “Strength” says: In the past Feng Long …

Based on these transcriptions, it would appear that the two texts are very similar, differing only occasionally in the graphic shape with which a word is written. For instance, in the case of Bi 比, “Alliance,” hexagram, the word rong is written 荣 (i.e., with a “grass” signific) in one text (no. 216) and 筞 (i.e., with a “bamboo” signific) in the other (no. 563); in the case of Ye 夜, “Night,” hexagram (which corresponds with Gu 蠱, “Parasite,” hexagram of the Zhou Yi), one text has the hexagram name as 亦 (no. 343), whereas the other gives it fully as 夜 (unnumbered). Only in the case of Da Zhuang 大壮, “Greater Strength,” hexagram is there a difference of more than orthographic significance: although there is a lacuna in the published transcription, it would appear that one text has the hexagram name written as Da Zhuang 大壯 or some variation of it (no. 408),50 whereas the other gives the name simply as Zhuang 壯, “Strength” (no. 320). Unfortunately, these examples are too isolated to allow any far-reaching conclusions to be drawn about the natures of the two texts (indeed, the transcription never even indicates to which text, that with narrow strips or that with thick strips, any given strip belongs).

It should perhaps be possible to use the registration numbers of the strips to gain some idea to which text they belong. Wang Mingqin says that in the process of excavating the block of mud containing the bamboo strips, three different strata were clearly observable. Moreover, even though the binding straps of the different texts had decomposed and the strips had become disordered, concentrations of different bundles of strips were nonetheless still visible. The archaeologists divided the 813 numbered strips into eight different groups (A–H), as follows:

A: nos. 1–180: containing primarily portions of the daybook, with occasional strips of the Gui cang

B: nos. 181–304: containing mainly strips of the Gui cang and the Xiao lü, with some other portions of the daybook

C: nos. 305–42: containing exclusively strips of the Gui cang

D: nos. 343–401: containing primarily portions of the daybook, with occasional strips of the Gui cang

E: nos. 402–538: strips of the Gui cang and the Xiao lü

F: nos. 539–620: containing primarily strips of the Gui cang and Zheng shi zhi chang, with occasional strips from the “Taboos” (Ji 忌) portion of the daybook

G: nos. 621–729: discrete portions of the daybook

H: nos. 730–813: composed exclusively of the Zai yi zhan

Although Wang Mingqin says that these groups are listed in descending stratigraphic sequence, the top stratum usually being the latest in the tomb, it is clear from this description that individual strips had moved around a great deal in the tomb prior to their excavation. This is apparent too from the rejoining of two fragments for Da Zhuang hexagram noted above: fragments no. 408 and no. 196 seem originally to have been (part of) a single strip; nevertheless, according to their entry numbers, they were in groups B and E, surely from two entirely different strata of the tomb. Thus, although the entry numbers may eventually prove to be helpful in understanding the contents of the various manuscripts,51 any firm conclusions will have to await the formal detailed archaeological report of the tomb. Even then, any conclusions will probably be sketchy at best.

The Gui Cang: Textual Contents

The Qing-dynasty reconstitutions of the Gui cang typically divide it into five different texts or chapters: “Qi shi” 啟筮, or “Milfoil Divinations of Qi [Lord of Xia],” “Zheng mu jing” 鄭母經, or “Classic of the Mother of Zheng,” “Qi mu jing” 齊母經, or “Classic of the Mother of Qi,” “Chu jing” 初經, or “Initial Classic,” and “Ben shi” 本蓍, or “Original Milfoil.” The first two of these names occur already in Guo Pu’s quotations of the Gui cang. Although many statements in the Gui cang, whether in the medieval quotations or in the Wangjiatai bamboo strips, concern Qi 啟, the first king of the Xia dynasty,52 and so “Milfoil Divinations of Qi” might be a natural section title, it is curious that not one of the dozen or so quotations attributed to this section concerns him at all; if there is any feature common to them, it is perhaps that they concern legendary events even before the time of this very early ruler. Ironically, one of two quotations explicitly attributed to the “Zheng mu jing” section does concern a divination of Qi. It has already been quoted above, together with a corresponding fragment from Wangjiatai (pp. 142–43). Perhaps worthy of note, the second of these quotations, also found in Guo Pu’s commentary on the Shan hai jing, is also found in the Wangjiatai bamboo strips.

歸藏鄭母經云昔者羿善射彃十日果畢之

The “Zheng mu jing” of the Gui cang says: “In the past Yi was good at shooting, shot at the ten suns and really netted them.”53

囗曰昔者羿卜毕十日羿果毕之思十日并出以 (470)

(470)

.. says: In the past Yi divined about netting the ten suns. Yi really did net them, hoping that the ten suns that came out together be taken …

The format of these statements is perhaps the prototypical format of the Gui cang and especially of the Wangjiatai texts. Some twenty-eight of forty hexagram statements that have enough content to determine their structure are of this sort. This has caused some to suggest that the Wangjiatai texts represent just the “Zheng mu jing” section.54 Though there seems to be little basis for this identification, this format certainly constitutes an important part of the Gui cang text.

The format begins with a hexagram name, saying that “in the past” (xizhe 昔者) someone divined (the Wangjiatai fragments consistently use the word bu 卜, which originally referred to turtle-shell divination but later could be used for any type of divination, whereas the medieval quotations of the Gui cang consistently use the word shi 筮, “milfoil divination”) about undertaking some action and then having that divination prognosticated by someone, who would pronounce it “auspicious” (ji 吉) or “not auspicious” (bu ji 不吉). After this general prognostication, there usually follow several phrases, sometimes suggesting what it would be “beneficial” (li 利) to do, sometimes a rhyming couplet or pair of couplets somewhat similar to the line statements of the Zhou Yi. Since in the following chapter I provide a complete translation of all Gui cang fragments, both those of the Wangjiatai texts and those of medieval quotations, I do not examine all the examples of this sort of statement here.

The persons said to perform the divinations include Shang Di 上帝, the god on high (Feng 丰, “Abundance”); Chi You 蚩尤, the legendary adversary of the Yellow Emperor 黄帝 (Lao 劳, “Belabored”); Nü Wa 女娲 (here written 女过), the sister/wife of Fuxi 伏羲 (Heng E 恒我); Heng E 恒我 (i.e., 姮娥), famous in mythology for having stolen the elixir of immortality from Xi Wang Mu 西王母, or the Western Queen Mother (Gui Mei 归妹, “Returning Maiden”); Jie 桀, the last king of the Xia dynasty; King Wu 武王 (Jie 节, “Moderation”), the first actual king of the Zhou dynasty; King Mu of Zhou 周穆王 (Shi 师, “Army”); the King of Chu 陼王 (Fu 复, “Returning”); the Lord of Song 宋君 (Zi 鼒, “The Small-Mouthed Cauldron”); Ping Gong 平公, presumably Song Ping Gong 宋平公 (r. 575–532 B.C.; You 右, or “Having,” or Da You 大有, “Great Having”); as well as several examples involving Xia Hou Qi, such as that in Ming Yi, “Brightness Obscured,” seen above.55 Most topics of divination concern particular events, whether legendary or historical, some well-known, such as Chi You’s “casting of the five weapons” (zhu wu bing 铸五兵), Heng E’s flight to the moon, King Wu’s attack on Yin, or King Mu’s sending out his army; others, such as the King of Chu’s “returning a white pheasant” (fu bai zhi 复白雉) or “making offering to Di” (shang Di  帝), either less well attested or less specific; and some topics having to do with nature, such as “leading the clouds and rain” (jiang yun yu 将云雨) or “exiting (or sending out) the clouds” (chu yun 出云; Zu 卒, “Complete”). The diviners are often figures known from early history, such as Wu Cang 巫苍, Gao Yao 皋陶, or Ying Huo 荧惑, but occasionally, as in the case of Da Ming 大明, they seem not to be known elsewhere. A notable feature is the propensity for their prognostications to be “not auspicious” (bu ji 不吉), though this is by no means always the case. The phrases that follow the general prognostication seem often to be related to the name of the hexagram or topic of the divination, but unfortunately there are very few complete hexagram statements that allow this relationship to be examined.

帝), either less well attested or less specific; and some topics having to do with nature, such as “leading the clouds and rain” (jiang yun yu 将云雨) or “exiting (or sending out) the clouds” (chu yun 出云; Zu 卒, “Complete”). The diviners are often figures known from early history, such as Wu Cang 巫苍, Gao Yao 皋陶, or Ying Huo 荧惑, but occasionally, as in the case of Da Ming 大明, they seem not to be known elsewhere. A notable feature is the propensity for their prognostications to be “not auspicious” (bu ji 不吉), though this is by no means always the case. The phrases that follow the general prognostication seem often to be related to the name of the hexagram or topic of the divination, but unfortunately there are very few complete hexagram statements that allow this relationship to be examined.

In the Wangjiatai texts, there seems to be only one hexagram statement that has been preserved more or less in its entirety, that for Zi 鼒, “The Small-Mouthed Cauldron,” hexagram.

鼒曰昔者宋君卜封□而攴占巫

鼒曰昔者宋君卜封□而攴占巫 苍

苍 占之曰吉鼒之

占之曰吉鼒之

鼒之

鼒之

初有吝

后果述

初有吝

后果述 (214)

(214) Zi “The Small-Mouthed Cauldron” says: In the past the Lord of Song divined about installing .. and had the stalks prognosticated by Wu Cang. Wu Cang prognosticated them and said: Auspicious. The small-mouthed cauldron’s grass snakes, the small-mouthed cauldron’s fragments. At first there is distress, later it is really in accord.

Zi “The Small-Mouthed Cauldron” says: In the past the Lord of Song divined about installing .. and had the stalks prognosticated by Wu Cang. Wu Cang prognosticated them and said: Auspicious. The small-mouthed cauldron’s grass snakes, the small-mouthed cauldron’s fragments. At first there is distress, later it is really in accord.

As noted, the  mark at the end of this statement is doubtless equivalent to the 乙 mark often used in early manuscripts to indicate the end of a particular segment of text. This suggests that with the exception of the single lacuna for the name of the person to be “installed” (feng 封), this statement is complete. It is not particularly intelligible for that completeness, but at least it shows both some relationship between the final omen statement and the hexagram name and the rhyming nature of the oracle (shu/*m-lut 述, “accord,” presumably meant to rhyme with zu/*tsût

mark at the end of this statement is doubtless equivalent to the 乙 mark often used in early manuscripts to indicate the end of a particular segment of text. This suggests that with the exception of the single lacuna for the name of the person to be “installed” (feng 封), this statement is complete. It is not particularly intelligible for that completeness, but at least it shows both some relationship between the final omen statement and the hexagram name and the rhyming nature of the oracle (shu/*m-lut 述, “accord,” presumably meant to rhyme with zu/*tsût  , “completion”).

, “completion”).

There are at least three other hexagram statements that can be reconstituted on the basis of the Wangjiatai texts combined with quotations in various medieval works.56 For instance, the hexagram statement of Shi 師, “Army,” hexagram can be reconstituted on the basis of three different Wangjiatai fragments and two different quotations in medieval literature. Wang Mingqin has rejoined the Wangjiatai fragments as follows:

师曰昔者穆天子卜出师而攴占□□□

师曰昔者穆天子卜出师而攴占□□□ (439)

(439)  龙降于天而□

龙降于天而□

远飞而中天苍

远飞而中天苍

Shi “Army” says: In the past Son of Heaven Mu divined about sending out the army and had the stalks prognosticated .. .. .. … … the dragon descended from heaven and .. … … distant; flying and piercing heaven; so green …

Shi “Army” says: In the past Son of Heaven Mu divined about sending out the army and had the stalks prognosticated .. .. .. … … the dragon descended from heaven and .. … … distant; flying and piercing heaven; so green …

The Taiping yulan contains a quotation that matches several parts of these fragments from Wangjiatai (indeed, it is doubtless the existence of the Taiping yulan quotation that has allowed Wang Mingqin to rejoin the three fragments) and completes the concluding oracle.

昔穆王天子筮出于西征不吉曰龍降于天而道里修遠飛而冲天蒼蒼其羽

In the past Son of Heaven King Mu divined by milfoil about going out on western campaign. Not auspicious. It said: The dragon descends from heaven [tian < *thin], but the road is long and far [yuan < *gwjanh]; flying and piercing heaven [tian < *thin], so green its wings [yu < *gwjagx].57

There is another point of considerable interest regarding this quotation. Wang Mingqin notes that it almost certainly includes a transcription error, showing that it derived ultimately from a paleographic original. Whereas Wangjiatai fragment no. 439 states that King Mu divined about “sending out the army” (chu shi 出师), the Taiping yulan quotation reads “going out on western campaign” (chu yu xi zheng 出于西征). The intriguing variant here is between shi 师, “army,” and yu 于, “on.” As Wang Mingqin argues, in Warring States paleographic materials, shi was usually written  , which is very similar in shape to yu 于. Syntactically, chu yu xi zheng 出于西征 is as reasonable a reading as chu shi xi zheng 出师西征 “send out the army to campaign westwardly,” likely the correct reading of its source text, but it loses the connection between the topic of the divination and the hexagram name.

, which is very similar in shape to yu 于. Syntactically, chu yu xi zheng 出于西征 is as reasonable a reading as chu shi xi zheng 出师西征 “send out the army to campaign westwardly,” likely the correct reading of its source text, but it loses the connection between the topic of the divination and the hexagram name.

Finally, the Jingdian shiwen 經典釋文 commentary of Lu Deming 陸德明 (556–627) to the Zhuangzi 莊子 cites the Gui cang by way of explaining the mention of a figure named Yu Qiang 禺强, the god of the North Pole.

歸藏曰昔穆王子筮卦于禺强

The Gui cang says: “In the past King-Son Mu divined the hexagram with Yu Qiang.”58

Although this quotation does not specify the hexagram to which it belongs, since Shi seems to be the only hexagram in the Gui cang that mentions King Mu, it is very likely this one. Piecing all these fragments together, and knowing the format of this type of statement, we arrive at the following complete hexagram statement:

師曰昔者穆天子卜出師(西征)而枚占于禺强,禺强占之曰:不吉。龍降于天,而道里修遠,飛而冲天,蒼蒼其羽。

師曰昔者穆天子卜出師(西征)而枚占于禺强,禺强占之曰:不吉。龍降于天,而道里修遠,飛而冲天,蒼蒼其羽。 Shi “Army” says: In the past Son of Heaven Mu divined about sending out the army (to campaign westwardly) and had the stalks prognosticated by Yu Qiang. Yu Qiang prognosticated them and said: Not auspicious. The dragon descends from heaven, but the road is long and far; flying and piercing heaven, so green its wings.

Shi “Army” says: In the past Son of Heaven Mu divined about sending out the army (to campaign westwardly) and had the stalks prognosticated by Yu Qiang. Yu Qiang prognosticated them and said: Not auspicious. The dragon descends from heaven, but the road is long and far; flying and piercing heaven, so green its wings.

Another statement that can be reconstituted by piecing together different fragments from Wangjiatai together with quotations in early and medieval texts is that of the hexagram Gui Mei 归妹, “Returning Maiden.” Two fragments from Wangjiatai read as follows:

In his commentary to the Wen xuan 文選, Li Shan 李善 (d. 689) twice quotes what is apparently the same passage from the Gui cang.

歸藏曰昔常娥以不死之藥奔月

The Gui cang says: “In the past Chang E took the medicine of immortality and fled to the moon.”59

周易歸藏曰昔常娥以西王母不死之藥服之遂奔月為月精

The Gui cang of the Zhou Yi says: “In the past Chang E took the Western Queen Mother’s medicine of immortality and ate it, and subsequently fled to the moon, becoming the essence of the moon.”60

It is clear that the Heng E 恒我 of Wangjiatai fragment no. 307 is identical with the mythological figure more commonly (though not invariably) known from the Han dynasty on as Chang E 常娥 (the “Heng,” 恒 or 姮, having been changed to “Chang,” 常 or 嫦, to avoid a taboo on the name of Liu Heng 劉恒, Han Wendi 漢文帝 [r. 179–157 B.C.]). Although it is understandable that the Wangjiatai fragments would not observe the later Han taboo, it is not clear what its observance or avoidance in these later quotations might mean. For example, “Heng E” in a Six Dynasties quotation might suggest an archaeological source, such as the Jizhong texts, that was not edited during the Han dynasty. The most complete citation of the Heng E or Chang E divination, almost surely quoted from the Gui cang, is found in the “Ling xian” 靈憲, or “Numinous Model,” of Zhang Heng 張衡 (78–139); curiously, even though this text dates to the Han dynasty, it does not observe the taboo on Liu Heng’s name, writing the protagonist’s name as Heng E, whereas a slightly later quotation of the same passage found in the Sou shen ji 搜神集, or Seeking the Spirits Collection, of Gan Bao 干寶 (fl. 320) writes her name as Chang E.

羿請不死之藥于西王母姮娥窃之以奔月將往枚筮之于有黄有黄占之曰吉翩翩歸妹獨將西行逢天晦芒毋惊毋恐後且大昌恒娥遂托身于月是為蟾蠩

Yi requested the medicine of immortality from the Western Queen Mother. Heng E stole it to flee to the moon. When she was about to go, she had the stalks divined by milfoil by You Huang. You Huang prognosticated them and said: Auspicious. So soaring the returning maiden, alone about to travel westward. Meeting heaven’s dark void; do not tremble, do not fear. Afterwards there will be great prosperity. Heng E subsequently consigned her body to the moon, and this became the frog.61

羿請无死之藥于西王母嫦娥窃之以奔月將往枚筮之于有黄有黄占之曰吉翩翩歸妹獨將西行逢天晦芒毋恐毋惊後且大昌嫦娥遂托身于月是為蟾蠩

Yi requested the medicine of immortality from the Western Queen Mother. Chang E stole it to flee to the moon. When she was about to go, she had the stalks divined by milfoil by You Huang. You Huang prognosticated them and said: Auspicious. So soaring the returning maiden, alone about to travel westward. Meeting heaven’s dark void; do not fear, do not tremble. Afterwards there will be great prosperity. Chang E subsequently consigned her body to the moon, and this became the frog.62

Aside from the inversion of the words jing 惊, “to tremble,” and kong 恐, “to fear,”63 the only difference in these two quotations is in the name Heng E or Chang E. Strangely enough, it is the putative Han-dynasty source that does not avoid the taboo on the word heng 恒, whereas the Jin-dynasty source does. What this might mean is unclear. However, Zhang Heng’s poem certainly suggests that a text of the Gui cang, or at least some portion of the materials in it, was extant to be quoted in the second century A.D. Putting all these fragments and quotations together, we thus arrive at something like the following hexagram statement for the Gui cang’s Gui Mei hexagram.

歸妹曰昔者姮娥窃毋死之藥于西王母以奔月將往枚筮之于有黄有黄占之曰吉翩翩歸妹獨將西行逢天晦芒毋恐毋惊後且大昌

歸妹曰昔者姮娥窃毋死之藥于西王母以奔月將往枚筮之于有黄有黄占之曰吉翩翩歸妹獨將西行逢天晦芒毋恐毋惊後且大昌 Gui Mei “Returning Maiden” says: In the past Heng E stole the medicine of immortality from the Western Queen Mother to flee to the moon. When she was about to go, she had the stalks divined by You Huang. You Huang prognosticated them and said: Auspicious. So soaring the returning maiden, alone leading along the western road. Meeting heaven’s dark void; do not fear, do not tremble, later there will be great prosperity.

Gui Mei “Returning Maiden” says: In the past Heng E stole the medicine of immortality from the Western Queen Mother to flee to the moon. When she was about to go, she had the stalks divined by You Huang. You Huang prognosticated them and said: Auspicious. So soaring the returning maiden, alone leading along the western road. Meeting heaven’s dark void; do not fear, do not tremble, later there will be great prosperity.

Here, the relationship between the concluding oracle and the topic of the divination is relatively clear: it begins with a mention of the name of the hexagram, alludes to both the western peregrination of Heng E and her flight to the moon, and ends with a prediction. Although this prediction would seem to be somewhat anomalous, the rhyme suggests that it is an integral part of the oracle.

| 翩翩歸妹, |

So soaring the returning maiden, |

| 獨將西行 (*grângh)。 |

Alone leading along the western road. |

| 逢天晦芒 (*mâng), |

Meeting heaven’s dark void; |

| 毋恐毋惊 (*krang), |

Do not fear, do not tremble, |

| 後且大昌 (*thang)。 |

Later there will be great prosperity. |

To conclude this examination of complete hexagram statements, the Wangjiatai manuscript hexagram statement for Ming Yi, “Brightness Obscured,” has already been examined at the beginning of this study (p. 142).

明夷曰昔者夏后启卜乘飞龙以登于天而攴占□□

明夷曰昔者夏后启卜乘飞龙以登于天而攴占□□

Ming Yi “Brightness Obscured” says: In the past Xia Hou Qi divined about flying on a dragon to rise into heaven and had the stalks prognosticated .. .. …

Ming Yi “Brightness Obscured” says: In the past Xia Hou Qi divined about flying on a dragon to rise into heaven and had the stalks prognosticated .. .. …

There I mention that it coincides neatly with a quotation of the Gui cang contained in Guo Pu’s commentary on the Shan hai jing.

歸藏鄭母經曰夏后啟筮御飛龍登于天吉

The “Zheng mu jing” of the Gui cang says: “Xia Hou Qi divined by milfoil about riding a flying dragon and ascending to heaven: Auspicious.”

In its chapter on dragons (scroll 929), the Taiping yulan also quotes this passage, adding the name of the hexagram, the diviner’s name, and the general prognostication, even if it does introduce certain obvious errors.

明夷曰昔夏啟上乘龍飛以登飛天皋陶占之曰吉

Ming Yi “Brightness Obscured” says: In the past Xia Qi went up riding a dragon flying in order to rise flying to heaven. Gao Yao prognosticated it and said: Auspicious.64

In another chapter, devoted to quotations concerning the founders of the Xia dynasty, the Taiping yulan contains the following two quotations:

歸藏曰昔夏后啟筮享神于大陵而上鈞台枚占皋陶曰不吉

The Returning to Be Stored says: “In the past Xia Hou Qi divined by milfoil about making offering to the spirits at the Great Mound and ascending the Equalizing Terrace, and had the stalks prognosticated by Gao Yao, who said: Not auspicious.”

史記曰昔夏后啓筮乘龍以登于天枚占于皋陶皋陶曰吉而必同與神交通以身為帝以王四鄉

The Records of the Historian says: “In the past Xia Hou Qi divined by milfoil about riding a dragon in order to rise to heaven, and had the stalks prognosticated by Gao Yao. Gao Yao said: Auspicious. Yet it must be the same, communicating with the spirits, with his body being Di, to rule over the four directions.”65

It is clear from its format that the first quotation is properly attributed to the Gui cang.66 On the other hand, it is also clear that the second quotation is misattributed. Not only does the Shi ji 史記, or Records of the Historian, not contain any passage remotely similar to this, but its similarity with the quotation in scroll 929 of the Taiping yulan as well as its format show that this quotation must come from the Gui cang; presumably the attribution was simply mistaken, either in the original compilation of the Taiping yulan or in some subsequent copying and publication.67

Though the format seen in the above complete hexagram statements, beginning with a divination about some event in the past, having it divined by some named diviner, who pronounces it either “auspicious” or “not auspicious,” and then a rhyming oracle that relates more or less directly to the topic of the divination, is certainly the most characteristic type of Gui cang hexagram statement, it is not the only type. In the Wangjiatai fragments, at least two other formats appear a few times apiece. The first of these begins with a generic divination prayer by the ruler of a state (e.g., Xia Hou Qi, the King of Yin [three times], [Song] Ping Gong) that there be no troubles or distress in his country (qi bang shang wu you jiu 亓邦尚毋有咎). Then, as in the preceding type of hexagram statement, this is followed with a prognostication in which a named diviner first pronounces the divination either “auspicious” or “not auspicious,” and finally an oracle that relates at least to the name of the hexagram. In the Wangjiatai fragments, there are at least seven such hexagram statements, of which three are relatively complete and bear scrutiny here.68

右曰昔者平公卜亓邦尚毋[有]咎而攴占神

右曰昔者平公卜亓邦尚毋[有]咎而攴占神 老

老 占曰吉有子亓□间

占曰吉有子亓□间 四旁敬□风雷不

四旁敬□风雷不 (302)

(302) You “Having” says: In the past Ping Gong divined about his country: Would that there be no trouble, and had the stalks prognosticated by Shen Lao. Shen Lao prognosticated them and said: Auspicious. There is a son, his .. midst [?]. The four sides respected .. , and wind and thunder did not …

You “Having” says: In the past Ping Gong divined about his country: Would that there be no trouble, and had the stalks prognosticated by Shen Lao. Shen Lao prognosticated them and said: Auspicious. There is a son, his .. midst [?]. The four sides respected .. , and wind and thunder did not …

Although the name of this hexagram is written as you 右, “right,” the oracle makes clear that at least the diviner here, Shen Lao 神老, interpreted the word to mean the cognate you 有, “to have,” as it does in the name of the corresponding hexagram in the Zhou Yi (i.e., Da You 大有, “Great Having”). Unfortunately, even at some thirty-two characters, the second longest of all the Wangjiatai fragments, this statement is still too fragmentary to make good sense of it.

The second example seems to be almost complete.

曰昔者殷王贞卜亓邦尚毋有咎而攴占巫咸

曰昔者殷王贞卜亓邦尚毋有咎而攴占巫咸 占之曰不吉

占之曰不吉 亓席投之

亓席投之

在北为

在北为 □

□  (213)

(213) Teng “Teng Snake” says: In the past the King of Yin determined the divination about his country: Would that there be no trouble, and had the stalks prognosticated by Wu Xian. Wu Xian prognosticated them and said: Not auspicious. Teng snake in his mat, throw it in the stream; the teng snake in the north turns into a female dog .. …

Teng “Teng Snake” says: In the past the King of Yin determined the divination about his country: Would that there be no trouble, and had the stalks prognosticated by Wu Xian. Wu Xian prognosticated them and said: Not auspicious. Teng snake in his mat, throw it in the stream; the teng snake in the north turns into a female dog .. …

At thirty-five characters, this is the longest of all Wangjiatai fragments. Unfortunately, it is not much more intelligible than the preceding statement, in part because of the hexagram name.69 The name of the hexagram here is a graph,  , unknown from any other context, and the corresponding hexagram in the Zhou Yi, Ji Ji 既濟, “Already Across,” would not seem to bear any relation to it. In the first phrase of the oracle, teng qi xi

, unknown from any other context, and the corresponding hexagram in the Zhou Yi, Ji Ji 既濟, “Already Across,” would not seem to bear any relation to it. In the first phrase of the oracle, teng qi xi  亓席, the word would seem to be acting as a verb, whereas in the third phrase, teng zai bei

亓席, the word would seem to be acting as a verb, whereas in the third phrase, teng zai bei  在北, it would seem to be a noun. Nevertheless, it is easy to see that the format of the oracle resembles line statements of the Zhou Yi.

在北, it would seem to be a noun. Nevertheless, it is easy to see that the format of the oracle resembles line statements of the Zhou Yi.

The third example is also incomplete and, since it is missing the hexagram name, is not even included in Wang Mingqin’s fullest account of the Wangjiatai manuscripts.70

One would like to know whether the final fragmentary phrase, which begins wang yong 王用, “the king herewith,” is part of the oracle or if it has some other use, such as a verification or statement of what the king did as a result of the divination. Unfortunately again, because of the broken strip at the end of the statement, there simply is not enough evidence to make a determination.

In addition to these fragments in the Wangjiatai bamboo strips, the Zhou li zhu shu 周禮注疏 quotes Jie 節, “Moderation,” hexagram of the Gui cang as reading 殷王其國常毋谷, the last three characters of which are an obvious deformation of shang wu you jiu 尚毋有咎, “would that there be no trouble” (or perhaps shang wu you lin 尚毋有吝, “would that there be no distress”). More important than anything this shows about transcription errors, it is worth noting that, as seen above, the Wangjiatai manuscripts contain a different version of Jie hexagram:

Jie “Moderation” says: In the past King Wu divined about attacking Yin and had the stalks prognosticated by Lao Qi. Lao Qi prognosticated and said: Auspicious. .. …

Jie “Moderation” says: In the past King Wu divined about attacking Yin and had the stalks prognosticated by Lao Qi. Lao Qi prognosticated and said: Auspicious. .. …

There is unfortunately no way of knowing whether the Zhou li zhu shu quotation misattributes its statement to Jie hexagram, or if perhaps a single hexagram could have two different types of statement, perhaps in different sections of the Gui cang.71 We can only hope that future discoveries will shed light on this question.

The third type of hexagram statement found in the Wangjiatai Gui cang manuscripts seems not to include the introductory narrative about a topic of divination. Instead, in several cases, after the hexagram picture and hexagram name, there comes immediately a series of phrases similar to the oracles of the other two types of hexagram statements. The following two statements are examples of this format:72

Tian Mu “The Heavenly Eye” so dawning, not beneficial for grasses or trees; so bright, raising those below .. …

Tian Mu “The Heavenly Eye” so dawning, not beneficial for grasses or trees; so bright, raising those below .. …

曰昔者赤乌止木之遽初鸣曰鹊后鸣曰乌有夫取妻存归亓家

曰昔者赤乌止木之遽初鸣曰鹊后鸣曰乌有夫取妻存归亓家 (212)

(212) Ji “Fishnet” says: In the past a red crow stopped on a tree’s perch. When it first sang out, it was said: A magpie. When it later sang out, it was said: A crow. There was a man who took a wife, but caringly returned her to her family …

Ji “Fishnet” says: In the past a red crow stopped on a tree’s perch. When it first sang out, it was said: A magpie. When it later sang out, it was said: A crow. There was a man who took a wife, but caringly returned her to her family …

Tian Mu 天目, “Heavenly Eye,” corresponds to Qian 乾 hexagram of the Zhou Yi, often understood to symbolize heaven. It seems possible that the adjectives associated with it here, zhao 朝, “dawn,” and zan 賛, “bright,” pertain to some heavenly apparition and so relate to the name of the hexagram, but it is difficult to say more than this. In the case of no. 212, if, as seems likely, the hexagram name is related to ji 罽, which the Shuo wen defines as “fishnet,” it might also be possible to relate the symbolism of the oracle to the name of the hexagram, since fish and fishing were common symbols for marriage and fertility.73 However, I see no connection between this hexagram name and statement and the hexagram name and line statements of the corresponding hexagram in the Zhou Yi, Guai  , “Resolute.”

, “Resolute.”

Based on the transcriptions published to date, there is one statement that appears to be anomalous. In the Gui cang tradition, this is an especially important hexagram, since it corresponds to Kun 坤 hexagram in the Zhou Yi and is supposed to have been the first hexagram in the Gui cang sequence. Unfortunately, not only is its format anomalous but also there are two characters that have not yet been identified with any confidence, including that for the hexagram name:  .74

.74

曰不仁昔者夏后启是以登天啻弗良而投之渊寅共工以□江□

曰不仁昔者夏后启是以登天啻弗良而投之渊寅共工以□江□ (501)

(501) Gua “Orphan” says: Not humane. In the past Xia Hou Qi divined by milfoil about rising into heaven. Di did not regard him as good and threw him into the abyss, leading Gong Gong to .. river .. …

Gua “Orphan” says: Not humane. In the past Xia Hou Qi divined by milfoil about rising into heaven. Di did not regard him as good and threw him into the abyss, leading Gong Gong to .. river .. …

Traditions concerning the Gui cang are unanimous in saying that this hexagram came at the head of the text. Some later sources write the name of the hexagram as  , others as shi

, others as shi  , which may reflect a different transcription of

, which may reflect a different transcription of  , though it is also possible, as Liao Mingchun 廖名春 has suggested, that it is instead an attempted transcription of the character

, though it is also possible, as Liao Mingchun 廖名春 has suggested, that it is instead an attempted transcription of the character  , mistaken for the hexagram name.75 Whatever the case may be in terms of the hexagram name, unless the graph 是 is to be read as shi 筮, “to divine by milfoil,” as I give here, in which case the statement would match almost all quotations of the Gui cang, the nature of the hexagram statement is different from all the other hexagram statements in the manuscripts.

, mistaken for the hexagram name.75 Whatever the case may be in terms of the hexagram name, unless the graph 是 is to be read as shi 筮, “to divine by milfoil,” as I give here, in which case the statement would match almost all quotations of the Gui cang, the nature of the hexagram statement is different from all the other hexagram statements in the manuscripts.

The Gui Cang: Historical Significance

Even without taking into account the intrinsic interest of its contents, just the textual history of the Gui cang would suffice to make it one of the most interesting texts from early China. Lost, discovered, lost again, and rediscovered (and perhaps lost again), the Gui cang has now finally achieved a celebrated place in the process of rewriting early Chinese history. This status is all the more enhanced because of its relationship with the Zhou Yi, the first of the Chinese classics. I discuss in a preliminary way this relationship elsewhere,76 but it seems appropriate to consider it again here.

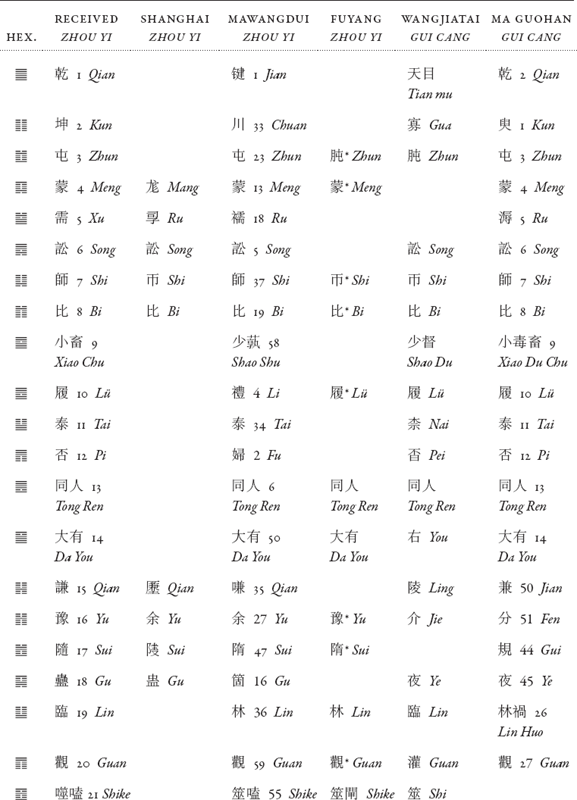

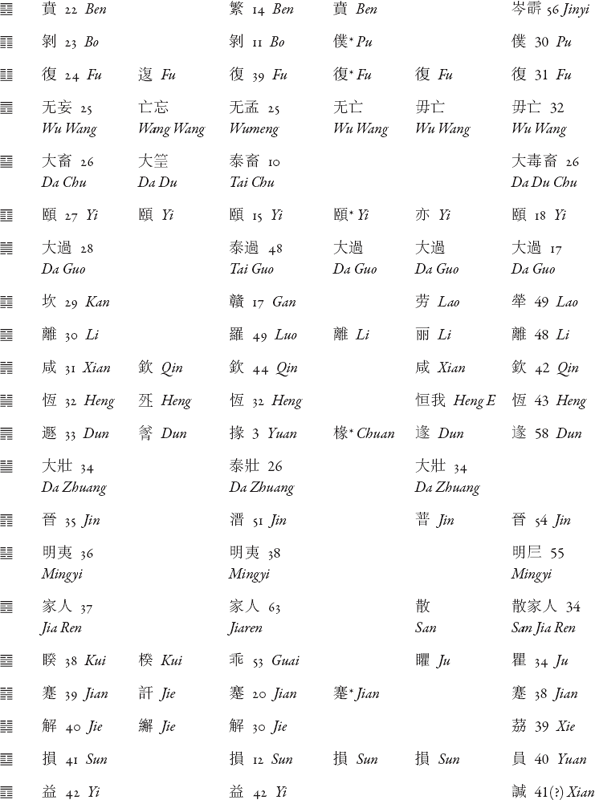

The other texts and divination materials found in the Wangjiatai tomb together with the two manuscripts of the Gui cang suggest that this manual was used by a practicing diviner. Even though they do not serve to explain how he might have used the text, much less when and how it was first composed, given what we now know about the early history of divination we can draw certain inferences about it. First, and perhaps most obvious, the Gui cang, like the Zhou Yi, is organized around the sixty-four combinations of solid and broken lines usually referred to in the West as hexagrams.77 Moreover, the names associated with these hexagrams are, for the most part, similar to those in the Zhou Yi tradition. When the Mawangdui manuscript of the Zhou Yi was discovered, scholars noticed that among its many variant hexagram names were several that were the same as or similar to names said to be found in the Gui cang.78 As mentioned, the Wangjiatai manuscripts contain fifty-four different hexagram pictures and fifty-three different hexagram names. As can be seen in table 4.1 (pp. 167–69), twenty-two of the hexagram names are identical to those of the corresponding hexagrams in the Zhou Yi, and another fifteen are either phonetically or graphically extremely similar. If we add the names of hexagrams mentioned in received sources for the Gui cang, we have another ten names that are identical. Some of the different names are probably synonymous, or at least partake of the same range of symbolic meanings.79 Although the Wangjiatai fragments often provide too little context to understand even the general meaning of the hexagram statement, something of this symbolic meaning can be seen in the four cases where I have been able to reconstruct complete or nearly complete statements. In at least three of these, some relationship seems possible between the Gui cang statement and the corresponding hexagram text in the Zhou Yi.80 The first of these is Zi 鼒, “The Small-Mouthed Cauldron,” hexagram, the only statement that is complete in the Wangjiatai manuscripts alone. This hexagram, which corresponds to Ding 鼎, “Cauldron,” hexagram of the Zhou Yi, records a divination concerning the establishment (feng 封) of someone (there is a lacuna in the text at the place of the recipient’s name). In the case of the Zhou Yi’s Ding hexagram, and indeed in early China in general, the cauldron was regarded as the symbol par excellence of governmental authority and thus perhaps carried the same symbolism as in the Gui cang. In the second case, Shi 師, “Army,” the Gui cang records a divination by King Mu of Zhou about sending out his army on campaign. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the hexagram of the same name in the Zhou Yi also has as its primary imagery a military campaign or campaigns. The third hexagram with a complete hexagram statement is Gui mei 歸妹, “Returning Maiden.” This too is the same name as found for the corresponding hexagram in the Zhou Yi. As seen in the reconstructed Gui cang hexagram statement, it concerns Heng E’s stealing the medicine of immortality from Xi Wang Mu 西王母, or the Western Queen Mother, and then fleeing to the moon, presumably without her husband, the archer Yi 羿, who had first requested the medicine. In the Zhou Yi, the various line statements of Gui mei all concern marriage, but the last of them, the Top Six line, strongly suggests a failed marriage.81

上六女承筐无實士刲羊無血无攸利

Top Six: The woman raises a basket without fruit, the man stabs the sheep without blood. There is nothing beneficial.

Could this sense also have informed the understanding of the diviner responsible for the Gui cang hexagram of the same name?

In at least two other cases, it seems that the name of a hexagram might have been original to the Gui cang, and that the similar name for the corresponding hexagram in the Zhou Yi may have been borrowed from it. In the Zhou Yi, the hexagram  is called Jin 晋, the name traditionally being understood as meaning “to advance” (perhaps as a phonetic loan for the word jin 進, “to advance”), though there is virtually no context in the hexagram text itself to support this understanding. In the Gui cang, on the other hand, the hexagram is called Jin

is called Jin 晋, the name traditionally being understood as meaning “to advance” (perhaps as a phonetic loan for the word jin 進, “to advance”), though there is virtually no context in the hexagram text itself to support this understanding. In the Gui cang, on the other hand, the hexagram is called Jin  , and it clearly refers to a place of that name.

, and it clearly refers to a place of that name.

Jin “Jin” says: In the past Xia Hou Qi divined about making offering to Di at Jin …

Another case of a hexagram in the Gui cang bearing a proper name is the name for  : Heng E 恒我, the name of the legendary figure famed for stealing the medicine of immortality.

: Heng E 恒我, the name of the legendary figure famed for stealing the medicine of immortality.

□恒我曰昔者女过卜作为缄而 (476)

(476)

.. Heng E “Heng E” says: In the past Nü Wa divined about making a binding and …

In the Zhou Yi, the corresponding hexagram is called simply Heng 恒. By no later than the time of Confucius, this hexagram of the Zhou Yi was already interpreted in the word’s abstract sense of “constancy.” The Nine in the Third line statement of the hexagram states,

九三不恒其德或承之羞貞吝

Nine in the Third: Inconstant his virtue, someone presents him disgrace. Determining: distress.

In the Analects, Confucius is quoted as saying,

子曰南人有言曰人而无恒不可以作巫醫善夫不恒其德或承之羞子曰不占而已矣

The Master said: “The people of the south have a saying, which says: ‘Someone without constancy cannot serve as a magician or a healer.’ Well put! ‘Inconstant his virtue, someone presents him disgrace.’” The Master said: “One does not just prognosticate and nothing else.”82

Assuming that it is more likely for an abstract meaning to be derived from a particular concrete reference than the other way around, the Gui cang might have given the name—Heng E in reference to the mythological figure—to this hexagram, and Confucius, or someone else, to have derived from a part of the name a general notion of “constancy.” Unfortunately, as is all too often the case, the manuscript text here is too fragmentary to allow for anything more than just a suggestion in this regard.

I have also suggested, above and in my earlier study of the Wangjiatai manuscripts, that the oracles that conclude the Gui cang hexagram statements are similar in format and function to the line statements of the Zhou Yi. If we consider just two of the statements examined above that are complete, I think this will be clear. As noted, the one complete statement in the Wangjiatai manuscripts is that for Zi 鼒 hexagram.

鼒曰昔者宋君卜封□而攴占巫

鼒曰昔者宋君卜封□而攴占巫 苍

苍 占之曰吉鼒之

占之曰吉鼒之

鼒之

鼒之

初有吝后果述

初有吝后果述 (214)

(214) Zi “The Small-Mouthed Cauldron” says: In the past the Lord of Song divined about installing .. and had the stalks prognosticated by Wu Cang. Wu Cang prognosticated them and said: Auspicious. The small-mouthed cauldron’s grass snakes, the small-mouthed cauldron’s fragments. At first there is distress, later it is really in accord.

Zi “The Small-Mouthed Cauldron” says: In the past the Lord of Song divined about installing .. and had the stalks prognosticated by Wu Cang. Wu Cang prognosticated them and said: Auspicious. The small-mouthed cauldron’s grass snakes, the small-mouthed cauldron’s fragments. At first there is distress, later it is really in accord.

Although the two characters  and

and  are unknown, and my translations something of an educated guess, the overall format is clear enough. It would be natural to compare the final couplet, chu you lin hou guo shu 初有吝后果述, “at first there is distress, later it is really in accord,” with such phrases in the Zhou Yi as wu chu you zhong 无初有終, “there is no beginning but there is an end” (both the Six in the Third line of Kui 睽 and Nine in the Fifth line of Xun 巽) or chu ji zhong luan 初吉終亂, “at first auspicious, in the end disordered” (hexagram statement of Ji Ji 既濟), or even with the line statement of the Top Six line of Mingyi:

are unknown, and my translations something of an educated guess, the overall format is clear enough. It would be natural to compare the final couplet, chu you lin hou guo shu 初有吝后果述, “at first there is distress, later it is really in accord,” with such phrases in the Zhou Yi as wu chu you zhong 无初有終, “there is no beginning but there is an end” (both the Six in the Third line of Kui 睽 and Nine in the Fifth line of Xun 巽) or chu ji zhong luan 初吉終亂, “at first auspicious, in the end disordered” (hexagram statement of Ji Ji 既濟), or even with the line statement of the Top Six line of Mingyi:

上六不明晦初登于天後入于地

Top Six: Not bright or dark: At first rising into the heavens, later entering into the earth.

As noted (p. 153), this oracle portion of Zi’s hexagram statement, unclear as it is, was obviously intended to rhyme:

鼒之  (*m-lai) (*m-lai) |

The small-mouthed cauldron’s grass snakes, |

鼒之  (*m-tsut) (*m-tsut) |

the small-mouthed cauldron’s fragments. |

| 初有吝 (*rəns) |

At first there is distress, |

| 后果述 (*m-lut) |

later it is really in accord. |

This is a feature that marks many of the oracles of the Gui cang. Above (pp. 154, 156) I have reconstructed the hexagram statements for Shi and Gui Mei hexagrams in their entirety. Their oracles also seem to feature rhyming couplets, with the statement for Gui Mei adding a fifth phrase that shares in the same rhyme.

| 龍降于天 (*thîn), |

The dragon descends from heaven, |

| 而道里修遠 (*wan?), |

but the road is long and far; |

| 飛而冲天 (*thîn), |

flying and piercing heaven, |

| 蒼蒼其羽 (*wa?)。 |

so green its wings. |

| 翩翩归妹 (*məs), |

So soaring the returning maiden, |

| 独将西行 (*grâŋ)。 |

alone leading along the western road. |

| 逢天晦芒 (*maŋ), |

Meeting heaven’s dark void; |

| 毋恐毋惊 (*raŋ), |

do not fear, do not tremble, |

| 后且大昌 (*thaŋ)。 |

later there will be great prosperity. |

Pairs of rhyming couplets can also be found occasionally in the Zhou Yi, most notably in the Nine in the Second line of Zhong fu 中孚, or “Inner Sincerity,” hexagram, which I display in the same way:

| 鳴鶴 (*gâuk) 在陰, |

A calling crane in the shade, |

| 其子和 (*wâi) 之。 |

Its young harmonize with it. |

| 我有好爵 (*tsiauk), |

We have a fine chalice, |

| 吾與爾靡 (*mai) 之。 |

I will together with you drain it. |

The Nine in the Third line statement of Ding hexagram has also sometimes been seen to have this structure because of the near rhyme between hui 悔, *hməh, “regret,” and the end words of the first three lines (ge 革, *krək, “leather; to strip,” sai 塞, *sək, “to block,” and shi 食, *m-lək, “to eat”).

九三鼎耳革其行塞雉膏不食方雨虧悔終吉

Nine in the Third: The cauldron’s ears are stripped [*krək]: Its movement blocked [*sək], The pheasant fat inedible [*m-lək], The region’s rains diminished; regret [*hməh], in the end auspicious.

However, as I indicate with the punctuation in my translation of this line statement, hui, “regret,” is a technical divination term that has been attached to—but is not formally part of—the oracle, which in its fullest form in the Zhou Yi comprises just a single couplet resuming and commenting on a single (usually) four-character phrase that describes an omen. Several excellent examples are to be found in other line statements of Ding hexagram.83

初六鼎顛趾利出否得妾以其子无咎

First Six: The cauldron’s overturned legs [*drə?]: Beneficial to expel the bad [*prə?], to get a wife with her children [*tsə?]. There is no trouble.

九二鼎有實我仇有疾不我能即吉

Nine in the Second: The cauldron has substance [*m-lit]: My enemy has an illness [*dzit], that cannot approach me [*tsit]. Auspicious.

九四鼎折足覆公餗其形渥凶

Nine in the Fourth: The cauldron’s broken leg [*tsok]: Overturns the duke’s stew [*sôk], its form glossy [*?rôk]. Ominous.

The two-couplet format of the Gui cang oracles, though apparently serving the same function as these line statements of the Zhou Yi, is actually structurally more reminiscent of poems in the Guo Feng 國風, or Airs of the States, section of the Shi jing. In these poems, an opening couplet describing some natural portent evokes (xing 興) a corresponding couplet describing the consequences for the poet. The final stanza of Tao yao 桃夭, or “Juicy Is the Peach” (Mao 6), or the first stanza of Que chao 鵲巢, or “The Magpie’s Nest” (Mao 12), are just two of scores of similar examples:

| 桃之夭夭其葉蓁蓁 |

|

The peach is so very juicy, Its leaves they are so very lush [*tsrin]. |

| 之子于歸宜其家人 |

|

This child on her way to marry, Is right for her family’s man [*nin]. |

| 維鵲有巢維鳩居之 |

|

It’s the magpie that has a nest, It’s the cuckoo that dwells [*ka?] in it. |

| 之子于歸百兩御之 |

|

This child on her way to marry, A hundred carts are driving [*ŋah] her. |

As much as the xing motif can help us to understand how the Gui cang’s oracles function, so too, I would contend, can the Gui cang oracles help us better to understand how these Shi jing poems should be understood. But that, perhaps, is a topic for another book.

Especially in the very incomplete form in which they have been published to date, the Wangjiatai texts of the Gui cang perhaps raise more questions than they answer about the performance of divination in the past and the production and nature of divination texts. But by providing indubitable evidence that there were available systems of divination alternative to the system of the Zhou Yi, they dramatically enrich the sorts of questions that we can ask, not only of the Gui cang itself but, and perhaps especially, of the Zhou Yi as well.84

节曰昔者武王卜伐殷而攴占老

节曰昔者武王卜伐殷而攴占老 占曰吉

占曰吉 (194)

(194) Jie “Moderation” says: In the past King Wu divined about attacking Yin and had the stalks prognosticated by Lao Qi.10 Lao Qi prognosticated and said: Auspicious …

Jie “Moderation” says: In the past King Wu divined about attacking Yin and had the stalks prognosticated by Lao Qi.10 Lao Qi prognosticated and said: Auspicious … 节曰昔者武王卜伐殷而攴占老

节曰昔者武王卜伐殷而攴占老 占曰吉

占曰吉 (194)

(194) Jie “Moderation” says: In the past King Wu divined about attacking Yin and had the stalks prognosticated by Lao Qi.10 Lao Qi prognosticated and said: Auspicious …

Jie “Moderation” says: In the past King Wu divined about attacking Yin and had the stalks prognosticated by Lao Qi.10 Lao Qi prognosticated and said: Auspicious … 明夷曰昔者夏后启卜乘飞龙以登于天而攴占□□

明夷曰昔者夏后启卜乘飞龙以登于天而攴占□□

Ming Yi “Brightness Obscured” says: In the past Xia Hou Qi divined about flying on a dragon to rise into heaven and had the stalks prognosticated .. .. …

Ming Yi “Brightness Obscured” says: In the past Xia Hou Qi divined about flying on a dragon to rise into heaven and had the stalks prognosticated .. .. … , that is,

, that is,  , corresponds with the hexagram known in the Yi jing tradition as Jie 節 (i.e., 节, “Moderation”), whereas that of

, corresponds with the hexagram known in the Yi jing tradition as Jie 節 (i.e., 节, “Moderation”), whereas that of  , that is,

, that is,  , corresponds with Ming Yi 明夷 (usually understood as “Brightness Obscured”), and these are the names given to the hexagrams here as well (as will be seen, this is not always the case). After the hexagram picture and the hexagram name, there then follows the text proper of the hexagram statement. In many cases, as in both cases here, this text reports a divination performed upon the occasion of some important event in early Chinese history or mythology. Here, the first records a divination by King Wu of Zhou proposing to attack Yin or Shang, and the second concerns a divination by Qi 启 (i.e., 啓), the first king of the Xia dynasty, proposing to fly on a dragon to ascend into heaven. The divinations were then prognosticated by someone, often a legendary figure known from ancient times; in the case of the first fragment here, the prognosticator is someone named Lao Qi 老

, corresponds with Ming Yi 明夷 (usually understood as “Brightness Obscured”), and these are the names given to the hexagrams here as well (as will be seen, this is not always the case). After the hexagram picture and the hexagram name, there then follows the text proper of the hexagram statement. In many cases, as in both cases here, this text reports a divination performed upon the occasion of some important event in early Chinese history or mythology. Here, the first records a divination by King Wu of Zhou proposing to attack Yin or Shang, and the second concerns a divination by Qi 启 (i.e., 啓), the first king of the Xia dynasty, proposing to fly on a dragon to ascend into heaven. The divinations were then prognosticated by someone, often a legendary figure known from ancient times; in the case of the first fragment here, the prognosticator is someone named Lao Qi 老 , who announces the prognostication “auspicious” (more often in this text, the prognostication is “not auspicious”). As will become evident later in this study, in other fragments this prognostication is followed by a rhyming oracle, more or less similar to line statements of the Zhou Yi.