In the West, the Changes, or Classic of Changes (hereafter simply Changes), is best known through the translation done by the German missionary Richard Wilhelm (1873–1930).1 Wilhelm lived in China for twenty years at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, witnessing firsthand the fall of China’s last imperial dynasty, the Qing (1644–1911), and the fledgling creation of a new republican government. During this time, he came to be a fervent admirer of China’s native traditions, especially Confucian thought, and established the Confucian Society in his adopted city of Qingdao 青島 in eastern China’s Shandong province. In 1913, Wilhelm began to work with the Chinese scholar Lao Naixuan 勞乃宣 (1843–1921) on his translation of the Changes. Lao had been an official under the Qing dynasty, which had been overthrown just two years before, and had sought refuge in the German protectorate.2 There he taught Wilhelm the dominant Song-dynasty interpretation of the Changes as a guide to life, an interpretation that Wilhelm succeeded brilliantly in translating into German. The famous first words of Qian 乾 A hexagram, the first of the text, yuan heng li zhen 元亨利貞, which literally mean something like “first enjoy benefit divination,” became in Wilhelm’s German “Das Schöpferische wirkt erhabenes Gelingen, fördernd durch Beharrlichkeit,” or, in the English translation by Cary F. Baynes, “The Creative works sublime success, Furthering through perseverance.”3 The English translation, in particular, furnished with an introduction by Wilhelm’s friend C. G. Jung (1875–1961) explaining the Changes as a product of the collective unconscious, became something of a bible for the postwar counterculture generation. It is said that until the vogue of professors becoming television personalities in the 1980s, Wilhelm’s translation of the Changes was the best-selling book by any university press in America.

A hexagram, the first of the text, yuan heng li zhen 元亨利貞, which literally mean something like “first enjoy benefit divination,” became in Wilhelm’s German “Das Schöpferische wirkt erhabenes Gelingen, fördernd durch Beharrlichkeit,” or, in the English translation by Cary F. Baynes, “The Creative works sublime success, Furthering through perseverance.”3 The English translation, in particular, furnished with an introduction by Wilhelm’s friend C. G. Jung (1875–1961) explaining the Changes as a product of the collective unconscious, became something of a bible for the postwar counterculture generation. It is said that until the vogue of professors becoming television personalities in the 1980s, Wilhelm’s translation of the Changes was the best-selling book by any university press in America.

At the same time that Wilhelm was working on his Changes translation in Qingdao, a few hundred miles to the west another Western missionary interested in traditional Chinese culture was very much involved in work that would also come to transform our understanding of the Changes. James M. Menzies (1885–1957), a Canadian Presbyterian missionary living in Anyang 安陽, Henan, began collecting “dragon bones” that peasants there were busily unearthing.4 According to at least one tradition, these bones—actually pieces of the scapula bones of oxen and plastrons of turtles—had first come to the attention of the Chinese epigrapher Wang Yirong 王懿榮 (1845–1900) in 1899, the year that Richard Wilhelm had arrived in China, when Wang purchased them in a Beijing apothecary. He is supposed to have noticed writing on the bones similar to the inscriptions on ancient bronze vessels with which he was familiar, but still more ancient. He quickly purchased all the other bones that he could find in Beijing. When his collection was subsequently published, it set off a chase to find the source of the bones, which led within a few years to Anyang.5 This was significant because Anyang was known to have been the site of the last capital of the Shang dynasty (16th c.–1045 B.C.), the dynasty immediately preceding the Zhou dynasty of Wen Wang, Zhou Gong, and Confucius. Antiquarians and scholars alike descended on Anyang, setting off a digging craze among the peasants living there. For his part, Menzies explored particularly the village of Xiaotun 小屯 near Anyang, which, excavations would subsequently show, was the site of the Shang royal palace and cemeteries; during his time at Anyang, Menzies collected well over ten thousand pieces of oracle bone.6 When these and others were published,7 paleographers determined that the bones did indeed come from the Shang dynasty and that their inscriptions were records of divinations performed on behalf of the last kings of that dynasty.

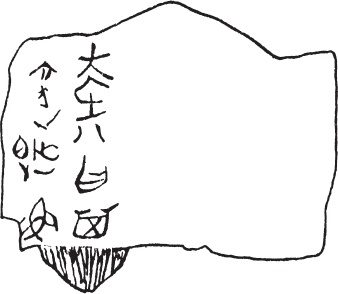

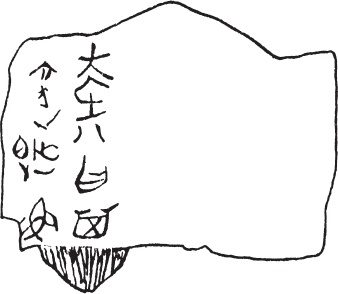

One of the most important early interpretive breakthroughs came with the identification of the character  , which appeared among the first words of almost every inscription. Scholars noted that the character was sometimes written in a more rounded form as

, which appeared among the first words of almost every inscription. Scholars noted that the character was sometimes written in a more rounded form as  , the pictograph of a cauldron, and that the word for cauldron, ding 鼎, was closely homophonous in ancient times with the word zhen 貞, ding pronounced something like *têŋ? and zhen something like *treŋ.8 The Shuo wen jie zi 說文解字, or Discussing Pictographs and Explaining Characters, the first dictionary in China, had defined zhen as “to inquire by crack making” (bu wen ye 卜問也).9 This was the same word found in the first line of the Changes, translated by Wilhelm as Beharrlichkeit, or “perseverance.” Wilhelm’s translation accorded with almost all traditional commentaries, which tended to gloss the word with yet another homophone, zheng 正, which means “upright” or “correct.” Indeed, we now know that all three of these words, zhen as well as ding, “cauldron,” and zheng, “upright,” are part of a larger word family that also includes words such as ding 丁, “nail” (originally written

, the pictograph of a cauldron, and that the word for cauldron, ding 鼎, was closely homophonous in ancient times with the word zhen 貞, ding pronounced something like *têŋ? and zhen something like *treŋ.8 The Shuo wen jie zi 說文解字, or Discussing Pictographs and Explaining Characters, the first dictionary in China, had defined zhen as “to inquire by crack making” (bu wen ye 卜問也).9 This was the same word found in the first line of the Changes, translated by Wilhelm as Beharrlichkeit, or “perseverance.” Wilhelm’s translation accorded with almost all traditional commentaries, which tended to gloss the word with yet another homophone, zheng 正, which means “upright” or “correct.” Indeed, we now know that all three of these words, zhen as well as ding, “cauldron,” and zheng, “upright,” are part of a larger word family that also includes words such as ding 丁, “nail” (originally written  or

or  , the pictographic form of a character now written 釘), ding 定, “settled” or “definite,” zheng 政, “government,” zheng 征, “punitive military campaign,” and ding 訂, “to correct a text.” All of these words share the sense of being (or making) upright, firmly placed, secure, correct. Even zhen, “to inquire by crack making,” shares this sense since divination in ancient China was not an open-ended inquiry into the future but more an assertion that one’s proposal for a future action was correct and deserving of divine assistance in its realization.10 Thus, Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 (A.D. 127–200), one of the best informed of the early commentators on the classics, combined these senses in his definition: “to inquire into the correctness” of some activity.11 The connection through this word between the Shang oracle-bone inscriptions and the text of the Changes would come to revolutionize our understanding of this most important of all Chinese texts.

, the pictographic form of a character now written 釘), ding 定, “settled” or “definite,” zheng 政, “government,” zheng 征, “punitive military campaign,” and ding 訂, “to correct a text.” All of these words share the sense of being (or making) upright, firmly placed, secure, correct. Even zhen, “to inquire by crack making,” shares this sense since divination in ancient China was not an open-ended inquiry into the future but more an assertion that one’s proposal for a future action was correct and deserving of divine assistance in its realization.10 Thus, Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 (A.D. 127–200), one of the best informed of the early commentators on the classics, combined these senses in his definition: “to inquire into the correctness” of some activity.11 The connection through this word between the Shang oracle-bone inscriptions and the text of the Changes would come to revolutionize our understanding of this most important of all Chinese texts.

The discovery of divination records from the Shang dynasty also stimulated in very large measure the development of modern archaeology in China. In 1928, the Institute of History and Philology of the newly established Academia Sinica began the first scientific excavations at Xiaotun. Continuing for a decade, these excavations turned up tens of thousands of more oracle bones and decisively confirmed that this was indeed the Shang capital.12 In addition to this general historical significance, the continued discovery of inscribed oracle bones also showed much more about Shang-dynasty divination practices. The following inscription, on a turtle shell unearthed in June 1936 from a large refuse pit at Xiaotun, includes all four parts of a complete Shang divination record: a “preface,” indicating the day of the divination and the name of the official presiding over it; the “charge” or topic being addressed to the turtle; the king’s “prognostication”; and a “verification” indicating, after the fact, what actually did happen.

癸丑卜爭貞自今至于丁巳我

王

王 曰丁巳我毋其

曰丁巳我毋其 于來甲子

于來甲子 旬又一日癸亥

旬又一日癸亥 弗

弗 之夕

之夕 甲子允

甲子允

Crack making on guichou [day 50], Zheng determining: “From today until dingsi [day 54], we will slash Xi.” The king prognosticated and said: On dingsi we will not slash [them]; on the coming jiazi [day 1], we will slash [them].” On the eleventh day guihai [day 60], Che did not slash them. That evening cleaving into jiazi he really did slash [them].13

In this case, the divination was one of several on guichou 癸丑, the fiftieth day in the Chinese cycle of sixty, or the preceding day, renzi 壬子 (day 49), and conducted either by Zheng 爭 or another, related diviner.14 The divination proposed a Shang attack five days later, on the day dingsi 丁巳, against an enemy state named Xi  . Related inscriptions suggest that this state was located to the west of Anyang in the area of present-day Shanxi province. The Shang king, in this case King Wu Ding 武丁 (r. ca. 1200 B.C.), intervened personally to give his own interpretation of the crack that had been made in the turtleshell: that an attack on dingsi would not be successful but that one several days later, on jiazi 甲子, the first day of a new cycle of sixty, would be successful. After this follows a record verifying that the king’s prognostication was indeed correct: the Shang really did “slash” (zai

. Related inscriptions suggest that this state was located to the west of Anyang in the area of present-day Shanxi province. The Shang king, in this case King Wu Ding 武丁 (r. ca. 1200 B.C.), intervened personally to give his own interpretation of the crack that had been made in the turtleshell: that an attack on dingsi would not be successful but that one several days later, on jiazi 甲子, the first day of a new cycle of sixty, would be successful. After this follows a record verifying that the king’s prognostication was indeed correct: the Shang really did “slash” (zai  ) the enemy Xi. Not all Shang divination records are as complete as this (indeed, most are much less complete), and it is rarer still that we can reconstruct their historical context even to the degree possible here. Nevertheless, by piecing together all the many tens of thousands of divination inscriptions that have been discovered to date, it is now possible to understand at least the rationale and much of the working of Shang divination.15 As will become evident, although there were numerous developments in the conduct of divination, certain features remained constant throughout ancient Chinese history and across the various media used to divine.

) the enemy Xi. Not all Shang divination records are as complete as this (indeed, most are much less complete), and it is rarer still that we can reconstruct their historical context even to the degree possible here. Nevertheless, by piecing together all the many tens of thousands of divination inscriptions that have been discovered to date, it is now possible to understand at least the rationale and much of the working of Shang divination.15 As will become evident, although there were numerous developments in the conduct of divination, certain features remained constant throughout ancient Chinese history and across the various media used to divine.

At the same time that Academia Sinica was conducting the first systematic excavations at Anyang, evidence in the divination records there that the word zhen in the Changes originally meant something like “to divine” stimulated an entirely new approach to the Changes. In 1929, Gu Jiegang 顧頡剛 (1893–1980), already famous as the editor of the iconoclastic journal Gu shi bian 古史辨, or Discriminations of Ancient History, published an article entitled “Zhou Yi gua yao ci zhong de gushi” 周易卦爻辭中的故事, or “Stories in the Hexagram and Line Statements of the Zhou Changes,” in which he used oracle-bone inscriptions and other ancient records to reinterpret the historical context of several images in the Changes.16 Several more such studies followed over the next two decades, culminating in some sense with the publication in 1947 of Zhou Yi gu jing jin zhu 周易古經今注, or New Notes on the Ancient Classic “Zhou Changes” by Gao Heng 高亨 (1900–1986).17 These “New Changes Studies,” as they have come to be known, viewed the Changes not as the timeless wisdom text that it eventually became after the time of Confucius but attempted instead to determine how it may have been used in the actual practice of divination and what it may have meant at the time of Wen Wang and Zhou Gong.

In 1973, archaeology and the Changes intersected again with the excavation of the Handynasty Tomb 3 at Mawangdui 馬王堆 in Changsha 長沙, Hunan, and its famous library of ancient texts written on bamboo and silk. The manuscripts found there, including one of the Changes together with a number of early commentaries, most of them previously unknown, and also two copies of the Laozi 老子, or Dao De Jing

, among many other texts, made Mawangdui a name known around the world. Some of these manuscripts, especially those of the Laozi, were published very quickly.18 Unfortunately, formal publication of the Changes manuscript has been stalled for a variety of reasons; it has still not been formally published, forty years after its discovery. Nevertheless, a preliminary report on the contents of the hexagram and line statements of the classic was released in 1984, photographs of this portion of the manuscript as well as the portion bearing the most important of the commentaries, the Xi ci 繫辭, or “Appended Statements,” were published in 1992, and complete transcriptions of the rest of the manuscript were published in quasi samizdat form in 1993 and 1995.19 Each of these publications stimulated flurries of excitement concerning the Changes, first because the classic portion of the text was arranged in a very different order from that of the received text and then because the new commentary material provides new perspectives on the development of the Changes tradition.

, among many other texts, made Mawangdui a name known around the world. Some of these manuscripts, especially those of the Laozi, were published very quickly.18 Unfortunately, formal publication of the Changes manuscript has been stalled for a variety of reasons; it has still not been formally published, forty years after its discovery. Nevertheless, a preliminary report on the contents of the hexagram and line statements of the classic was released in 1984, photographs of this portion of the manuscript as well as the portion bearing the most important of the commentaries, the Xi ci 繫辭, or “Appended Statements,” were published in 1992, and complete transcriptions of the rest of the manuscript were published in quasi samizdat form in 1993 and 1995.19 Each of these publications stimulated flurries of excitement concerning the Changes, first because the classic portion of the text was arranged in a very different order from that of the received text and then because the new commentary material provides new perspectives on the development of the Changes tradition.

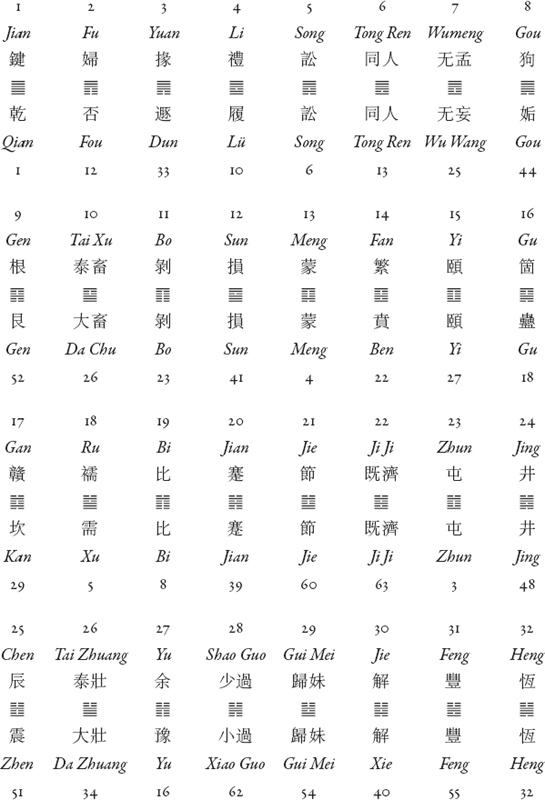

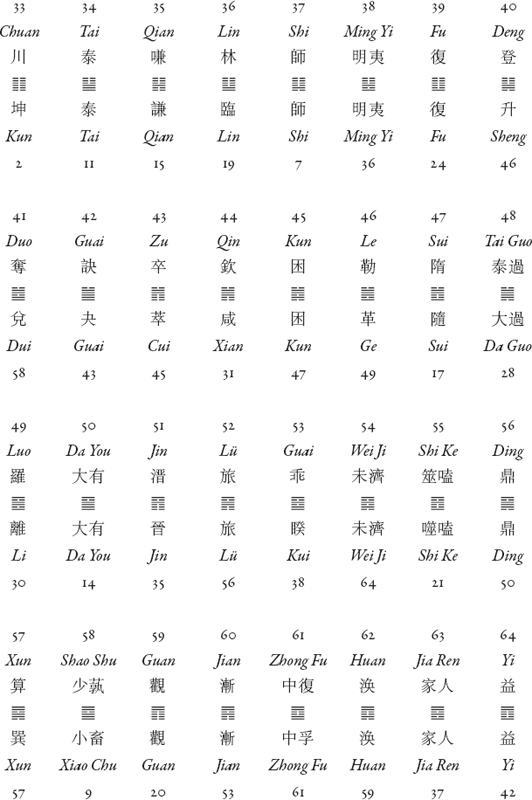

The sequence of the sixty-four hexagrams in the received text of the Changes shows no discernible logic other than that pairs of hexagrams sharing a single invertible hexagram picture—or in the eight cases where inversion produces the same hexagram picture by the conversion of all lines to their opposite—are always grouped together. Thus, Sun 損, “Decrease,” the forty-first hexagram in the received sequence, has the hexagram picture  , whereas the hexagram picture of Yi 益, “Increase,” the forty-second hexagram, is its inverse:

, whereas the hexagram picture of Yi 益, “Increase,” the forty-second hexagram, is its inverse:  . To give another example, the twenty-third hexagram in the traditional sequence, Bo 剝, “Paring,”

. To give another example, the twenty-third hexagram in the traditional sequence, Bo 剝, “Paring,”  , is paired with the twenty-fourth hexagram, Fu 復, “Return,”

, is paired with the twenty-fourth hexagram, Fu 復, “Return,”  . With hexagrams such as Qian 乾, “Vigorous,”

. With hexagrams such as Qian 乾, “Vigorous,”  , or Kan 坎, “Pit,”

, or Kan 坎, “Pit,”  , the first and twenty-ninth hexagrams, respectively, the inversion of which would produce exactly the same picture, the pairs are Kun 坤, “Compliant,”

, the first and twenty-ninth hexagrams, respectively, the inversion of which would produce exactly the same picture, the pairs are Kun 坤, “Compliant,”  and Li 離, “Fasten,”

and Li 離, “Fasten,”  , in which all lines change aspect. As many readers have noted over the millennia, the texts of these hexagram pairs are also often related, whether by complementarity or by inversion. Not only are Sun, “Decrease,” and Yi, “Increase,” obviously related by topic, but the Six in the Fifth line statement of Sun is virtually identical with the line statement of Yi’s Six in the Second line, which is the line that the fifth line of Sun becomes when inverted.

, in which all lines change aspect. As many readers have noted over the millennia, the texts of these hexagram pairs are also often related, whether by complementarity or by inversion. Not only are Sun, “Decrease,” and Yi, “Increase,” obviously related by topic, but the Six in the Fifth line statement of Sun is virtually identical with the line statement of Yi’s Six in the Second line, which is the line that the fifth line of Sun becomes when inverted.

損六五或益之十朋之龜弗克違元吉

Sun, “Decrease,” Six in the Fifth: Someone increases it, ten double strands of turtle shells. You cannot go against them. Prime auspiciousness.20

益六二或益之十朋之龜弗克違

Yi, “Increase,” Six in the Second: Someone increases it, ten double strands of turtle shells. You cannot go against them.

Similarly, the line statements of Qian, “Vigorous,” which is usually interpreted as referring to the heavens, and Kun, “Compliant,” understood to refer to the earth, seem to complement each other as an almanac of a full year.21

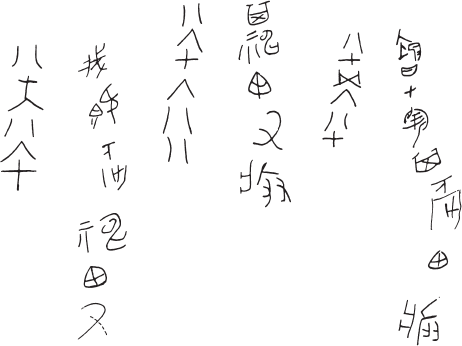

By contrast, the Mawangdui manuscript is arranged according to systematic combinations of the hexagrams’ constituent three-line graphs, usually referred to in the West as trigrams. Each of the eight trigrams forms a set of eight hexagrams all sharing the same top trigram, according to the following order (using the names of the trigrams as given in the manuscript):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jian |

Gen |

Gan |

Chen |

Chuan |

Duo |

Luo |

Suan |

| 鍵 |

根 |

贛 |

辰 |

川 |

奪 |

羅 |

筭 |

They combine in turn with trigrams of the bottom trigram in the following order (except that each of the top trigrams first combines with its same trigram):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jian |

Chuan |

Gen |

Duo |

Gan |

Luo |

Chen |

Suan |

| 鍵 |

川 |

根 |

奪 |

贛 |

羅 |

辰 |

筭 |

This gives a hexagram sequence completely different from that of the received text, as seen in table 1.1. When this sequence was first published, there was a vigorous debate as to whether the hexagram sequence of the manuscript or that of the received text represented the original or, at least, an earlier sequence.22 There is still no definitive evidence with which to resolve this debate,23 though there does seem to be a growing consensus that the Mawangdui manuscript represents primarily a sequence used by diviners of the Han dynasty (202 B.C.–A.D. 220).24

Ten years after the first publication of the hexagram and line statements portion of the manuscript, bare transcriptions of the remaining portions of the manuscript—five or six commentaries, depending on how one counts—were finally published. Only one of these commentaries, that of the Xi ci, or “Appended Statements,” was previously known, and even its contents were somewhat different from those of the received text. This publication again brought the Changes to the forefront of scholarly interest and touched off yet another vigorous debate, this one over whether this particular commentary reflects more Confucian or Daoist thought.25 The Xi ci, like the other canonical commentaries found in the received text, was traditionally supposed to have been written by Confucius. Even though the Mawangdui manuscript, like the received version of the Xi ci, includes numerous sayings explicitly attributed to Confucius, several passages of the received text were not found in the manuscript but rather in one or another of the manuscript’s other commentaries. Some scholars argued that these were precisely the passages with the strongest Confucian message and that they must have been introduced into the received text of the Xi ci some time after the imperial recognition of Confucianism in 136 B.C., thirty years after the date of the Mawangdui burial. This too is a debate for which no definitive evidence has surfaced; indeed, it is hard to imagine what sort of evidence might resolve it. Fortunately, in the years following the excavation of the Mawangdui tomb, there have been numerous other discoveries that have kept scholars occupied with other issues.

Already between the time of the opening of the Mawangdui tomb in 1973 and the first publication of the hexagram and line statements portion of its Changes manuscript in 1984, archaeologists had discovered several other sorts of textual materials that have perhaps even more bearing on the original nature of the Changes (as opposed to how the text came to be understood). First, in 1975 a tomb was opened at Shuihudi 睡虎地, Yunmeng 雲夢, Hubei, with 1,235 bamboo strips (of which fully 1,155 were intact) on which were written records of various sorts. This would prove to be but the first of many significant discoveries of tombs with texts in the present-day province of Hubei, which was the homeland of the great southern state of Chu 楚 and which, by chance, has a high water table that serves to preserve organic materials, such as bamboo-strip manuscripts, buried in ancient tombs. The texts in the tomb at Shuihudi included a hybrid public-private annals chronicling significant events in the state of Qin 秦 beginning in 305 B.C. and in the life of the deceased, a man named Xi 喜, from his birth in 262 until the last entry in 217, presumably the year of his death.26 The private entries in this annals indicate that Xi was a local magistrate, so it is fitting that the tomb also contained law codes of the state of Qin, which had previously conquered the region, as well as a text entitled Wei li zhi dao 為吏之道, or The Way of Being a Public Servant.27 However, the lengthiest single texts are two copies of a rishu 日書, or daybook or almanac that indicates auspicious days for the performance of such actions as making sacrifices, giving birth to children, digging wells, marrying, and going on military campaign, among many other specific and general topics.28 The following passages covering six different types of days give a fair indication of the nature of these texts:29

(The sequence number and name above each hexagram picture refer to the Mawangdui manuscript; those below refer to the received text.)

結日作事不成以祭閵生子毋弟有弟必死以寄二人二必奪主室

On Knot days, starting affairs will not be successful; for making sacrifices, distress; in giving birth to a son, it ought not be a younger brother, for if it is a younger brother, he will certainly die; in entrusting to others, the one entrusted will certainly take over the host’s house.

陽日百事順成邦君得年小夫四成以蔡上下羣神鄉之乃盈志

On Sunny days, the hundred affairs will all be successful; the country and district will get their harvests, and the common people will be successful all around; in sacrificing, all the higher and lower spirits will receive it and then fulfill one’s intent.

交日利以實事鑿井吉以祭門行二水吉

On Intersecting days, beneficial for solid affairs; digging a well will be auspicious; sacrificing, moving gates, and moving water will be auspicious.

害日利以除凶厲兌不羊祭門行吉以祭最眾必亂者

On Harmful days, beneficial to dispel the ominous and danger and to get rid of what is not lucky; sacrificing and moving gates will be auspicious; sacrificing in great number will certainly be disorderly.

陰日利以家室祭祀家子取婦入材大吉以見君上數達毋咎

On Shady days, beneficial to marry and start a household; sacrificial offerings, marrying a son, taking a wife, and contributing resources will be greatly auspicious; in seeing the lord or superiors, if you arrive several times, there will be no trouble.

達日利以行帥出正見人以祭上下皆吉生子男吉女必出於邦

On Arriving days, beneficial to set the army in motion and go out on campaign and to see others; in sacrificing, the high and low will all be auspicious; in giving birth to children, males will be auspicious, for females will certainly leave the country.

Not only are these the same sorts of topics addressed by the hexagram and line statements of the Changes but also several of the prognostications and injunctions seen here, such as “beneficial to dispel the ominous and danger” (li yi chu xiong li 利以除凶厲), “beneficial to marry and start a household” (li yi jia shi 利以家室), or “beneficial to set the army in motion and go out on campaign” (li yi xing shi chu zheng 利以行帥出正),30 share specific vocabulary with certain hexagram and line statements in the Changes (not to mention such common formulas as “nothing not beneficial” [wu bu li 无不利], “beneficial to have someplace to go” [li you you wang 利有攸往], etc.), as the following examples show.

謙六五不富以其鄰利用侵伐无不利

Qian, “Modesty,” Six in the Fifth: Not enriched by his neighbor. Beneficial herewith to invade and attack. There is nothing not beneficial.

謙上六鳴謙利用行師征邑國

Qian, “Modesty,” Top Six: Calling modesty. Beneficial herewith to set in motion the army and correct the city and kingdom.

大畜初九有厲利已

Da Chu, “Greater Livestock,” First Nine: There is danger. Beneficial to sacrifice.

大過九二枯楊生稊老夫得其女妻无不利

Da Guo, “Greater Surpassing,” Nine in the Second: The withered poplar grows shoots, the old man gets his woman wife. There is nothing not beneficial.

蹇利西南不利東北利見大人貞吉

Jian, “Lame”: Beneficial to the southwest, not beneficial to the northeast. Beneficial to see the great man. Determining: auspicious.

益初九利用為大作元吉无咎

Yi, “Increase,” First Nine: Beneficial herewith to undertake a great action. Prime auspiciousness. There is no trouble.

困九二困于酒食朱紱方來利用亨祀征凶无咎

Kun, “Bound,” Nine in the Second: Bound by wine and food. The country of the scarlet kneepads comes. Beneficial herewith to make offering and sacrifice. Campaigning: ominous. There is no trouble.

鼎初六鼎顛趾利出否得妾以其子无咎

Ding, “Cauldron,” First Six: The cauldron’s overturned legs. Beneficial to expel the bad, to get a wife together with her children. There is no trouble.

These examples from both the daybook and the Changes could be multiplied many times over. It seems clear that both texts derived from much the same sort of cultural context.

Two years after the discovery of the Shuihudi bamboo-strip texts, in 1977, archaeologists unearthed a very different sort of divination texts at Fengchu 鳳雛, Qishan 岐山, Shaanxi, in the middle of an area referred to as the Zhouyuan 周原, or “Plain of Zhou,” traditionally regarded as the homeland of the Zhou people (from whom the other name of the Changes, Zhou Yi 周易, or Zhou Changes, derives).31 Buried within the confines of a midsize temple or residential structure was a cache of seventeen thousand pieces of turtle shell, about three hundred of them inscribed.32 This was the first major discovery of oracle-bone inscriptions outside the Shang capital at Anyang and demonstrated beyond any doubt that turtle-shell divination was by no means practiced only by the Shang people. Although most of these inscriptions are quite fragmentary, they seem to concern activities undertaken by the first kings of the Zhou dynasty, probably in the eleventh century B.C. The following, H11:1, is a rare example of a complete divination prayer.

On guisi [day 30], performing the yi sacrifice at the temple of the accomplished and martial Di Yi, determining: “The king will sacrifice to Cheng Tang, performing a cauldron exorcism of the two surrendered women and a yi sacrifice with the blood of three rams and three sows; would that it be correct.”

Although the content of this inscription, seemingly indicating that the Zhou king directed at least some of his sacrifices to the high ancestor of the Shang kings (with whom he seems to have been related by blood), remains unique in the inventory of Zhou divination records,33 it displays a format that would remain standard for centuries to come. Like the Shang oracle-bone inscriptions, it begins with a preface indicating the time and place of the divination ritual, followed by the topic of the divination, in this case proposing the sacrifice of two women and six domesticated animals. Somewhat different from the Shang inscriptions, the divination then concludes with a formulaic prayer stating the hope that the spirits to whom the divination was directed would regard the action as correct.34

Another feature of the Zhouyuan oracle-bone inscriptions, as these divination records are usually called, bears perhaps even more directly on the origin of Changes divination. Several pieces contain sets of six numerals, which scholars now almost universally agree reflect an early form of the six-lined graphs—the hexagrams—so famous from the Changes. Since the first identification of these sets of numerals, by the Chinese scholar Zhang Zhenglang 張政烺 (1912–2005),35 scores of other examples have been discovered on various media. Zhang suggested, in line with traditional Chinese numerology, that odd numbers in these sets should be regarded as yang, and thus correspond with solid lines of Changes hexagrams, whereas even numbers should be regarded as yin, and thus correspond with broken lines. For instance, on the fragment H11:85, we find the following text:

7-6-6-7-1-8 says: It …

.. having already fished …36

According to Zhang, the two numbers “7” and the “1” should convert to yang, or solid lines, and the two numbers “6” and the “8” would convert to yin, or broken lines, producing the hexagram picture  , which in the Changes tradition corresponds with Gu 蠱, “Parasites,” hexagram (hexagram 18 in the traditional Changes sequence). Unfortunately, this—and all other Zhouyuan oracle bones with these numerical symbols—is fragmentary and provides little or no context for understanding what role it played in the divination. For example, although others read the two columns of characters together, treating the words ji yu 既漁, “having already fished,” in the second column as something akin to a line statement, not only is there no similar line statement in the received text of the Changes, but also it is not even clear that this belongs to the same divination or what the missing characters might be.37

, which in the Changes tradition corresponds with Gu 蠱, “Parasites,” hexagram (hexagram 18 in the traditional Changes sequence). Unfortunately, this—and all other Zhouyuan oracle bones with these numerical symbols—is fragmentary and provides little or no context for understanding what role it played in the divination. For example, although others read the two columns of characters together, treating the words ji yu 既漁, “having already fished,” in the second column as something akin to a line statement, not only is there no similar line statement in the received text of the Changes, but also it is not even clear that this belongs to the same divination or what the missing characters might be.37

Archaeological work has continued to the present day in the vicinity of the 1977 discovery. A pair of discoveries made in the opening years of the new millennium both bear—rather differently—on these numerical symbols. One of these discoveries is once again a piece of inscribed turtle shell that was certainly used in divination. Excavated in 2003 very near Qijia 齊家 village, just to the east of the Fengchu temple or residence that produced the first great discovery of Zhou oracle bones, it is but one of numerous new Zhou oracle-bone inscriptions that have been unearthed in recent years.38 This piece contains three separate divinations, all concerning an illness of someone apparently unnamed. Unfortunately, one of two main verbs of the inscriptions has never before been seen and is not readily interpreted, and the other verb has also been interpreted in two quite different ways; although the translations offered here should be regarded as tentative, the overall sense seems clear: these are divinations regarding someone who is ill, proposing rituals that the diviner(s) hope will bring improvement in his condition.

翌日甲寅其 甶廖

甶廖

八七五六八七

On the next day, jiayin [day 51], we will make offering; would that he improve.

8-7-5-6-8-7

其 甶又廖

甶又廖

八六七六八八

We will pray; would that there be improvement.

8-6-7-6-8-8

我既

甶又

甶又

八七六八六七

We have already made offering and prayed; would that he be blessed.

8-7-6-8-6-7

There are three things to note about the inscriptions on this single oracle bone.

First, as in the example from Fengchu translated above, all three of the divination records here are phrased as prayers to the spirits, the final formulaic phrase being initiated with the word si 甶 (i.e., 思), “to wish; would that.” As mentioned above, the realization that ancient Chinese divination, in all its forms, was phrased in the form of a prayer and conceived of as a purposeful expression of the diviner’s intention is a key to understanding how these divinations functioned. This is as true of divination with the Changes as it is of turtle-shell divination.

Second, the three records are obviously related, with the first two apparently proposing two contrasting propitiatory rituals (one, the never before seen character  , plausibly being a form of sacrifice,39 and the other

, plausibly being a form of sacrifice,39 and the other  , a character for which two different transcriptions have been proposed, apparently indicating a form of prayer40), whereas the third seems to have been produced after the first two (as shown by the word ji 既, “after; having done”). As I show below (p. 21 and n. 56), this two-step procedure seems to have been a regular feature of Zhou-dynasty turtle-shell divination and may well also have influenced Changes divination.

, a character for which two different transcriptions have been proposed, apparently indicating a form of prayer40), whereas the third seems to have been produced after the first two (as shown by the word ji 既, “after; having done”). As I show below (p. 21 and n. 56), this two-step procedure seems to have been a regular feature of Zhou-dynasty turtle-shell divination and may well also have influenced Changes divination.

And third, each of the records is paired with one of these sets of six numerals. There is now a scholarly consensus that these sets of numerals express the result of some sort of divination by sortilege, such as the sorting of milfoil stalks traditionally used in Changes divination, even if it is still unclear how the results of this sortilege divination came to be related either to those of the oracle-bone divination or to the solid and broken lines of the Changes hexagrams.41

The second discovery was actually made two years earlier than that at Qijia village. In 2001, in Xiren 西仁 village, Chang’an 長安 county, Shaanxi, archaeologists from the Shaanxi Institute of Archaeology excavated the remains of a Western Zhou pottery workshop. They recovered from it several pottery paddles, pestle-shaped pottery tools used in the making of pottery vessels. On two of these, there were numerical symbols, in one case (CHX 採集: 1) two such symbols lined up vertically next to each other and in the other case (CHX 採集: 2) four symbols arranged in a sort of ring, with two oriented vertically and two horizontally.42 The numbers on CHX 採集: 1 are particularly easy to see:

They read (from right to left) 六一六一六一, or 6-1-6-1-6-1, and 一六一六一六, or 1-6-1-6-1-6 (note that the numbers are upside down in the photograph of the paddle). Converting these numbers to the solid and broken lines of a hexagram would produce the two hexagram pictures  and

and  , which in the Changes are the hexagrams Ji Ji 既濟, “Already Across,” and Wei Ji 未濟, “Not Yet Across,” the sixty-third and sixty-fourth hexagrams in the traditional sequence. Cao Wei 曹瑋, the lead excavator of the site, interprets this pair of hexagram pictures to represent the result of a single divination performed in conjunction with the production of this or some other pottery piece, one of the symbols being the “base hexagram” (ben gua 本卦) result and one being the “changing hexagram” (zhi gua 之卦), known from later divination practice. This is unlikely, not only because there is no other early evidence that divination resulted in such changing hexagrams,43 and certainly none in which all six lines “change,” as would be the case here, but also because of the groupings of numerals on the second pottery paddle.

, which in the Changes are the hexagrams Ji Ji 既濟, “Already Across,” and Wei Ji 未濟, “Not Yet Across,” the sixty-third and sixty-fourth hexagrams in the traditional sequence. Cao Wei 曹瑋, the lead excavator of the site, interprets this pair of hexagram pictures to represent the result of a single divination performed in conjunction with the production of this or some other pottery piece, one of the symbols being the “base hexagram” (ben gua 本卦) result and one being the “changing hexagram” (zhi gua 之卦), known from later divination practice. This is unlikely, not only because there is no other early evidence that divination resulted in such changing hexagrams,43 and certainly none in which all six lines “change,” as would be the case here, but also because of the groupings of numerals on the second pottery paddle.

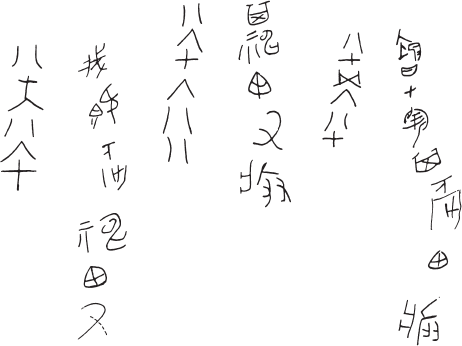

The numerical symbols engraved on the second pottery paddle are by no means as easy to see or to read as those on the first. Indeed, it is only in a line drawing that the numbers become more or less clear. What is clear is that there are four sets of six numerals (though one number of the far left-hand set has been effaced): two oriented vertically (in the rubbing) and two oriented horizontally, though the two horizontally oriented sets seem to run in opposite directions from each other (based on the orientation of the number “6” [Λ, i.e., liu 六]). Reading these from right to left produces the following “hexagrams”:

| 八八六八一八

8-8-6-8-1-8 |

|

Shi 師, “Army” |

| 八一六六六六

8-1-6-6-6-6 |

|

Bi 比, “Alliance” |

| 一一六一一一

1-1-6-1-1-1 |

|

Xiao Chu 小畜, “Lesser Livestock” |

| 一一一六一[一]

1-1-1-6-1-[1] |

|

Lü 履, “Stepping” |

These are the seventh, eighth, ninth, and tenth hexagrams in the traditional sequence of the Changes. As Li Xueqin 李學勤 has pointed out, even if one or another of these symbols was the result of an actual divination, it is almost inconceivable that a pair of divinations could produce “changing hexagrams” in exactly this sequence.44 He argues instead that both this grouping and that on the first paddle (which produces the two hexagrams Ji Ji and Wei Ji) must reflect a deliberate selection of hexagram pictures. He argues, as well, that if this is so, it provides strong evidence that the traditional sequence of the sixty-four hexagrams in the Changes was already in existence no later than the late Western Zhou, the date of the latest pieces found in this pottery workshop.

As Li says, “this kind of discovery ought to be regarded as astounding,”45 if the transcription and analysis are correct. There are reasons for skepticism: it is unclear why two of the groupings should be oriented vertically and two horizontally; it is even more unclear why the two horizontally oriented groupings of numbers should run in reverse directions; the sixth number of the last grouping of numbers has been effaced and has to be supplied by inference;46 the pieces seem to have been “collected” (caiji 採集) at the site rather than excavated in situ; and finally, it is difficult to understand why hexagram pictures should appear on the handle of a pottery paddle. Nevertheless, these two pieces do represent hard archaeological evidence of these numerical hexagram pictures that has to be taken into account in any history of the development of the Changes.

To return to the year 1977, when the first Zhouyuan oracle bones were being discovered in western China’s Shaanxi province, it was a time of other important archaeological discoveries also very much related to the Changes. In that same year, archaeologists in the eastern province of Anhui excavated a pair of Han-dynasty tomb mounds at a site called Shuanggudui 雙古堆 in the city of Fuyang 阜陽. The larger of the two mounds turned out to be the tomb of the lord of the state of Ruyin 汝陰, who is known from historical records to have died in 165 B.C. This is just three years later than the date of the Mawangdui tomb, which had been discovered four years earlier. Like the Mawangdui tomb, this tomb too was furnished with a veritable library of ancient texts, these all written on bamboo strips: an early dictionary called the Cang Jie pian 倉頡篇, a copy of the Shi jing 詩經, or Classic of Poetry, a medical text called Wan wu 萬物, or Ten Thousand Things, two different sorts of historical annals, and a daybook, as well as a text of the Zhou Yi.47 Unfortunately, the bamboo strips on which these texts were written were very badly preserved. Thus, even though a brief report of the discovery was published in 1983, with a surprisingly accurate description of most of the texts, it was not until the year 2000 that a complete transcription of the Fuyang Zhou Yi, as this text is now usually called, was finally published.48

The eight hundred fragments of which this text was constituted still represent only a small portion of the entire text,49 but they suffice to show the original nature of this manuscript. It is composed first of all of the individual hexagram and line statements of the Changes, matching the received text rather closely. Then, to each of these hexagram and line statements is attached at least one and often several formulaic divination statements of the type seen in the daybook from Shuihudi. These formulas concern personal topics, administrative topics, work-related topics, and also, of course, the weather. Even a thumbnail description such as this should suffice to suggest how important the Fuyang Zhou Yi manuscript is for understanding how the text was used in a divination context as late as the Han dynasty. In chapter 6, I describe the text in much more detail, discussing as well its significance for the history of the Changes, and in chapter 7, I provide a complete translation of the manuscript.

The archaeological discoveries of the 1970s, of which those mentioned constitute only a portion (among other notable discoveries, doubtless the best known are the terra-cotta army unearthed near the tomb of Qin Shi Huangdi 秦始皇帝, the First Emperor [r. 246/221–210 B.C.], and the Shang-dynasty tomb of Fu Hao 婦好 [d. ca. 1195 B.C.], consort of the Shang king Wu Ding), were so astounding in both their number and quality and so unprecedented compared even with the previous excavations at Anyang that scholars often use the decade as a dividing line in the study of ancient China: prior to that time studies of early China were based almost exclusively on the received literature; since then, there have been increasing calls to “rewrite” early Chinese history based on unearthed evidence.50 Fortunately, the end of the decade did not bring an end to archaeological discoveries. Indeed, with respect to manuscripts and other textual materials, the pace of discovery seems only to have accelerated.

Almost all the manuscript materials discovered in the 1970s, whether written on bamboo or silk, derived from the Han dynasty. Only the Shuihudi tomb, the occupant of which died in 217 B.C., dates to before this period, and even it came four years after the Qin unification of China in 221 B.C. Whether in terms of institutional or intellectual history, the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 B.C.) has long marked the foremost dividing line in ancient Chinese history. In short order, the Qin government instituted a centralized bureaucracy marked by unified standards for all the states that it had conquered. One of these standardizations was a unification of the writing styles that had been used in those states during the preceding centuries, known as the period of the Warring States. Another Qin attempt at intellectual unification was the infamous “burning of the books” in 213. It is now much debated just how much effect this imperial decree actually had,51 but it does seem that a great deal of China’s ancient literary heritage disappeared about this time (perhaps due as much, if not more, to the destruction caused by the civil war that brought the Qin dynasty to an end a few years later). Scholars and rulers alike in the subsequent Han dynasty made great efforts to reconstitute this literary heritage, searching among the populace for copies of ancient texts, editing them, and producing fair copies for the imperial library, rewritten in the new clerical script of the time. Despite the great debt that the Chinese literary tradition owes to these editors, modern historians have long suspected that their editorial activities had the effect of “rewriting” the texts in ways more important than just changing the style of script used.52 Thus, despite the great discoveries of the 1970s, scholars still yearned for manuscripts that came from the Warring States period. They did not have long to wait.

The first significant discovery of textual material from the Warring States period came in January 1987, from tomb 2 at Baoshan 包山, in Hubei province near the former capital of the southern state of Chu 楚. The 288 bamboo-strip documents in the tomb show that this was the tomb of one Shao Tuo 召 , a local magistrate who died in 316 B.C.53 The greater part of the strips record court cases over which he presided and thus provide rare information about the history of law in ancient China.54 However, there is also a considerable corpus, fifty-four strips, that record divinations that were performed and prayers that were offered on behalf of Shao Tuo during the last years of his life. Although many of these divinations used turtle shells, five of them used some method that produced a result expressed as a pair of hexagrams. With both methods, the record of the divination is essentially identical, beginning with the date of the divination, the name of the diviner presiding, and the divination material he used. This was followed by the topic, or “charge,” of the divination proper, expressed as a desire that the matter would result in success. The divination officer then prognosticated the result, invariably interpreting the auspices as indicating that though the long-term prognosis was auspicious, in the short term there were problems requiring sacrificial propitiation. The record of these sacrifices was accompanied by yet another prayer for their success and a final prognostication, invariably “auspicious,” offered by a different person. The following example is illustrative:

, a local magistrate who died in 316 B.C.53 The greater part of the strips record court cases over which he presided and thus provide rare information about the history of law in ancient China.54 However, there is also a considerable corpus, fifty-four strips, that record divinations that were performed and prayers that were offered on behalf of Shao Tuo during the last years of his life. Although many of these divinations used turtle shells, five of them used some method that produced a result expressed as a pair of hexagrams. With both methods, the record of the divination is essentially identical, beginning with the date of the divination, the name of the diviner presiding, and the divination material he used. This was followed by the topic, or “charge,” of the divination proper, expressed as a desire that the matter would result in success. The divination officer then prognosticated the result, invariably interpreting the auspices as indicating that though the long-term prognosis was auspicious, in the short term there were problems requiring sacrificial propitiation. The record of these sacrifices was accompanied by yet another prayer for their success and a final prognostication, invariably “auspicious,” offered by a different person. The following example is illustrative:

大司馬悼愲將楚邦之師以救郙之歲荆尸之月己卯之日陳乙以共命為左尹 貞出入侍王自荆尸之月以就集歲之荆尸之月盡集歲躬身尚毋有咎一六六八六六 一六六一一六占之恒貞吉少有憂于宫室以其故敚之舉禱宫行一白犬酉飤甶攻敘于宫室五生占之曰吉

貞出入侍王自荆尸之月以就集歲之荆尸之月盡集歲躬身尚毋有咎一六六八六六 一六六一一六占之恒貞吉少有憂于宫室以其故敚之舉禱宫行一白犬酉飤甶攻敘于宫室五生占之曰吉

In the year that the Great Supervisor of the Horse Dao Hua led the army of the Chu state to relieve Fu, in the Jingshi month, on the day jimao, Chen Yi used the Proffered Command to divine on behalf of Commander of the Left Tuo: “Coming out and going in to serve the king, from the Jingshi month all the way until the next Jingshi month throughout the entire year, would that his person not have any trouble.” 1-6-6-8-6-6 1-6-6-1-1-6 He prognosticated it: “The long-term divination is auspicious, but there is a little worry in the palace chamber. For this reason propitiate it, raising up prayers in the palace, moving one white dog and ale to drink; would that this dispel the trouble in the palace chamber.” Wu Sheng prognosticated it, saying: “Auspicious.”55

This divination record reveals much: again that divination was phrased as a prayer to the spirits seeking their aid in arriving at some desired result; that the results could be expressed in the form of hexagrams known from the Changes tradition; and that the results required prognostication. On the other hand, there is also much about which this record does not inform us. Why was the result expressed in the form of a pair of hexagrams? And why was it necessary, as it seems to have been, to perform two divinations and two prognostications, and how and why did the second differ from the first? And did the diviner consult a book in arriving at his prognostication, and if so did it bear any resemblance to the received Changes? Elsewhere I have offered certain hypotheses that may help to answer the first two of these questions, but since the evidence remains unclear, it seems desirable for now to leave them as open questions.56 However, with respect to the final pair of questions, some evidence has recently become available that might point the way to some answers.

In July 1994, a cache of more than fifteen hundred bamboo strips was unearthed from a large tomb at Geling 葛陵 village, fifteen miles northwest of Xincai 新蔡, Henan. The first report on the tomb was released only in 2002, followed quickly by the formal site report in 2003.57 It shows that this was the tomb of a local lord named Cheng, Lord of Pingye 平夜君成, many of the records in the tomb recording divinations about him. The date of his death is still under debate, but the most probable date seems to be 398 B.C.,58 more than half a century earlier than even the Baoshan strips and thus reaching back near the early stage of the Warring States period. Among the texts are the following bamboo strips, unfortunately all fragmentary, that share common physical characteristics and the same handwriting. Song Huaqiang 宋華強, who has studied these strips in detail, believes that they derive from a single act of divination, apparently concerning a trip by Cheng to the Chu capital of Ying 郢, perhaps to respond to some rumor or allegation against him.59 The first two strips begin like the divination records from Baoshan, but the latter two seem to quote material very similar to line statements that we find in the Changes. Indeed, the word in the last strip translated here as “oracle” (zhou 繇) is the same word used to refer to the hexagram lines and line statements of the Changes.60

齊客陳異致福于王之歲獻馬之月乙丑之日…

The year that the Qi envoy Chen Yi presented blessings to the king, the Xianma month, the yichou day …

… 衤筮為君貞居郢還返至于東陵尚毋有咎占曰兆无咎有祟 …

… X divining by milfoil on behalf of the lord, determined: “Residing in Ying and returning as far as Dongling, would that there not be any trouble.” Prognosticating, he said: In the result there is no trouble, [but] there is a curse …

… (

) This is to stab and wound your mouth. Still this is not a great shame. Don’t worry; there is no trouble. …

) This is to stab and wound your mouth. Still this is not a great shame. Don’t worry; there is no trouble. …

… 其繇曰氏日末兑大言 二小言惙二若组若结终以 …

二小言惙二若组若结终以 …

… its oracle says: This day’s end is Dui: major sayings so sincere, minor sayings so worrisome. Orderly and knotlike, in the end use to …61

It would seem that the text of the third strip translated above represents the divination official’s extemporaneous prognostication of the hexagram result, beginning with a rhyming couplet that first describes the omen of the result and then provides his assessment of its significance. This is followed by his advice to the person for whom the divination was being performed: “don’t worry” (wu xu 毋卹62) and “there is no trouble” (wu jiu 无咎). Both these phrases occur formulaically in the received text of the Changes (wu jiu, “there is no trouble,” occurring ninety-three times); indeed, they both occur in both the Nine in the Third line statement of Tai 泰, “Greatness,” and the First Six of Cui 萃, “Assembled,” hexagrams:

泰九三无平不陂无往不復艱貞无咎勿恤其孚于食有福

Tai, “Greatness,” Nine in the Third: There is no flat that does not slope, there is no going that does not return. Determining about difficulty: there is no trouble. Don’t worry about his trust; in food there are blessings.

萃初六有孚不終乃亂乃萃若號一握為笑勿恤往无咎

Cui, “Assembled,” First Six: There is trust unending, then disordered then assembled, like a scream once grasped becomes a laugh. Don’t worry. Going: there is no trouble.

I suspect that we see in this Xincai divination record something of the process by which the Changes line statements were originally produced.63 This is a topic that I explore in more detail in chapter 6 in the context of the Fuyang Zhou Yi manuscript.

On the other hand, as Song Huaqiang 宋華強 has argued, the “oracle” quoted on the fourth strip,

氏日末兑大言 二小言惙二若组若结终以 …

二小言惙二若组若结终以 …

This day’s end is Dui: major sayings so sincere, minor sayings so worrisome. Orderly and knotlike, in the end use to …,

may have been taken from a divination manual similar to, though obviously not the same as, the Changes.64 It begins with a phrase introducing the omen followed by a couplet that indicates its auspices for the situation being divined, differentiated by being “greater” (da 大) and “lesser” (xiao 小), and then perhaps followed by a sort of verification (initiated by the word zhong 终, “in the end”). Although this oracle is not found in the received text of the Changes, its format is more or less similar to some line statements of that text, as in the following examples:

坎六三來之坎坎險且枕入于坎窞勿用

Kan, “Pit,” Six in the Third: Bringing it bam-bam: Steep and deep, entering into the pit opening. Do not use it.

遯九四好遯君子吉小人否

Dun, “Piglet,” Nine in the Fourth: A good piglet. For a nobleman auspicious, for a little man not.

家人九三家人嗃嗃悔厲吉婦子嘻嘻終吝

Jia Ren, “Family People,” Nine in the Third: Family people ha-ha. Regret; danger; auspicious. Wives and children, hee-hee. In the end, distress.

夬九三壯于頄有凶君子夬夬獨行遇雨若濡有慍无咎

Guai, “Resolute,” Nine in the Third: Wounded on the forehead. It is ominous. The nobleman is so resolute: Moving alone and meeting rain, if wet he will get steamed up. There is no trouble.

節六三不節若則嗟若无咎

Jie, “Moderation,” Six in the Third: If not moderately, then sighingly. There is no trouble.

It is worth noting that Dui 兑, the omen mentioned, is the name of one of the eight trigrams ( ) and sixty-four hexagrams (

) and sixty-four hexagrams ( ). In the Changes tradition at least, this trigram is associated with the mouth and speech.65 This perhaps explains why “sayings” (yan 言) are mentioned here, and perhaps also why this oracle might give rise to the extemporaneous prognostication given in the third of the Xincai strips: “This is to stab and wound your mouth” (shi ce chuang er kou 是

). In the Changes tradition at least, this trigram is associated with the mouth and speech.65 This perhaps explains why “sayings” (yan 言) are mentioned here, and perhaps also why this oracle might give rise to the extemporaneous prognostication given in the third of the Xincai strips: “This is to stab and wound your mouth” (shi ce chuang er kou 是 而口).

而口).

Even though these Xincai bamboo strips were discovered in 1994, they became available to the scholarly world only in 2002 with the publication of the excavation’s first site report. In the years between their discovery and first publication, several other sites in Hubei, near where the Baoshan strips had been found, were excavated and the texts in them published, truly launching the study of Warring States bamboo strips. Indeed, the year before, 1993, was a year of very great significance in the study of ancient Chinese texts and thought. There were three discoveries of texts from the fourth and third centuries B.C., all three astounding in different ways.

The first of the discoveries to come to widespread public attention came from a tomb in the village of Guodian 郭店, like that of Baoshan just outside the Warring States capital of the southern state of Chu. In August 1993, tomb robbers dug down to the wooden planks covering the outer coffin of the tomb before apparently giving up their efforts. Archaeologists from the nearby Jingmen 荊門 City Museum went to the site, determined that no harm had been done, and filled in the tomb. However, two months later, robbers struck the tomb again, this time opening a shaft into the tomb chamber itself and taking out some of the grave goods and damaging many of the rest. Fortunately, the archaeologists returned to the tomb and were able to salvage much of its contents, including a large cache (804 strips) of bamboo strips, most of which were intact, even if at first blackened and rather in a jumble.66 Unlike the Baoshan strips discovered six years earlier, these strips bore philosophical texts, including what was announced first to be three early copies of the Laozi, after the Changes probably the next most studied and discussed text in the Chinese philosophical tradition. An international conference greeted the publication of these strips less than five years later,67 and for two or three years it seemed that every scholar in China and many also in the West thought of nothing else. Even from the vantage point of ten years’ distance, that enthusiasm does not seem to have been misplaced, even though the Guodian strips probably raised more new questions than they answered old ones. When the strips had been published, it turned out that whereas the Laozi texts were indeed interesting,68 most scholars focused more on the other fifteen or so texts that seem to provide evidence of the development of the Confucian tradition during the crucial period between the death of Confucius (479 B.C.) and the time of Mencius 孟子 (ca. 320–310 B.C.).69 Although none of the Guodian texts quotes the Changes directly,70 two of them do mention it in important ways. The text Liu de 六德, or Six Virtues, lists the Yi along with the Shi 詩 (Poetry), Shu 書 (Documents), Li 禮 (Rites), Yue 樂 (Music), and Chun qiu 春秋 (Springs and Autumns), obviously understanding them as the “six classics,” and the text known as Yu cong I 語叢 (Thicket of Sayings), apparently in a similar context, says of the Yi that it “is that by which the way of heaven and the way of man are brought together” (Yi suo yi hui tian dao ren dao ye 易所以會天道人道也).71 It is clear from this that already by the late fourth century B.C., the Changes was regarded by some at least as an integral part of the classics.

At about the same time the archaeologists were salvaging the Guodian tomb, tomb robbers apparently struck at another tomb, probably in the same general area. One can only say “apparently” and “probably” because archaeologists seem never to have found the tomb. Instead, the bamboo strips from it appeared early in 1994 in the Hong Kong antique market, where they were purchased on behalf of the Shanghai Museum. The Shanghai Museum is the oldest and arguably the most important museum in China and was led at the time by a particularly vibrant director, Ma Chengyuan 馬承源 (1927–2004). The museum organized a team of scholars to edit these strips, which turned out to be similar to but even more extensive than the Guodian strips. Nine volumes have been published to date, at the rate of about one a year, each volume touching off a new spate of studies.72 Among the strips published in the third volume, in 2003, was a copy of the Changes.73 Although the manuscript is fragmentary, with only about a third of the received text available, it is clear that the hexagram and line statements portion of the text was complete—essentially in the form in which we know it today.

As is the case with virtually all early manuscripts of texts with transmitted counterparts, there are in the Shanghai Museum manuscript a great many graphic variants vis-à-vis the received text. There is still no consensus as to what value to assign to these variants. Many of the earliest studies of the text have taken the position that the readings of the received text are “correct,” and that most of the manuscript differences are tantamount to spelling errors. Others would argue that as the earliest text of the Changes that we have, the manuscript’s readings should always have priority. Probably the correct approach lies somewhere between these two extremes, with the received text sometimes superior, the manuscript sometimes superior, and very often with both versions having something to recommend them. As I argue in chapter 2, in which I give a detailed presentation of the manuscript and its historical significance, the enigmatic images of the Changes may not be amenable to traditional textual criticism, the diviners and exegetes responsible for its creation and transmission having reveled in the multiple possibilities inhering in the early form of the Chinese script.

Much of the interest in the Shanghai Museum manuscript of the Changes to date has concerned one of two questions, which may well be interrelated. First is the question of the sequence of hexagrams in it, a question that has loomed large in Changes studies ever since the Mawangdui manuscript was discovered with its radically different arrangement. A crucial feature of the Shanghai Museum manuscript is that each hexagram begins on a new bamboo strip, with the text then continuing onto one or two (or in one case three) more strips, with any space leftover on the last strip left blank. Given this format it would have been difficult to determine the original sequence of the hexagrams even under ideal archaeological circumstances. As noted, the circumstances of the Shanghai Museum manuscripts were far from ideal. By the time the strips had passed from the hands of the tomb robbers to the Hong Kong antiques merchants and finally to the Shanghai Museum, not only were they completely disordered but also many of them had been lost or broken. Nevertheless, I have suggested, and suggest again in chapter 2, that it may be possible to use the physical characteristics of the manuscript to gain some idea of its original arrangement and have concluded that the sequence of hexagrams in this manuscript was probably very similar to, if not identical with, that of the received text.74 Indeed, with one notable exception, there seems to be a growing consensus that this was the case.

The exception to this consensus is the editor of the manuscript, Pu Maozuo 濮茅左, a senior curator at the Shanghai Museum. He has presented a totally different arrangement of the text based on a feature of the manuscript never before seen in the Changes tradition: red and/or black symbols found at the beginning and end of the hexagram texts. There appear to be six such symbols: a solid red square  ; a three-sided hollow red square (by which I mean a right-facing U shape, similar to 匚) with an inset smaller solid black square

; a three-sided hollow red square (by which I mean a right-facing U shape, similar to 匚) with an inset smaller solid black square  ; a solid black square

; a solid black square  ; a three-sided hollow black square with an inset smaller solid red square

; a three-sided hollow black square with an inset smaller solid red square  ; a solid red square with an inset hollow black square

; a solid red square with an inset hollow black square  ; and a three-sided hollow black square

; and a three-sided hollow black square  . In most cases in which both the first and last strips of a hexagram survive in the manuscript, the symbols at the beginning and end of the text are identical. However, in three cases, the symbol at the end is different from that at the beginning. In the Shanghai Museum publication of the manuscript, Pu Maozuo devotes a special appendix to explaining the significance of the symbols, suggesting that red is a manifestation of the yang, or “sunny,” characteristic and black that of the yin, or “shady,” characteristic.75 With respect to the hexagrams in which the symbols differ, he suggests that they mark transitional stages in the respective growth and decline of the yin and yang. Ingenious though this explanation is, it has now been demonstrated conclusively that the strips that display this difference were written in a different hand from that of the other strips of the manuscript.76 This would seem to obviate any comparison between the symbols in the two different groups. At this point, it seems still premature to say just what these symbols were meant to represent and what, if anything, they suggest about the sequence of the hexagrams. It does seem safe to say, though, that the Shanghai Museum manuscript of the Changes will command the attention of people interested in the Changes for years to come. Chapter 2 presents, first, a detailed overview of the manuscript’s discovery and editing, its physical nature, and a comparison of its text with that of the received text; in chapter 3, I give a complete transcription and translation of the text, together with the received text and a translation of it as well.

. In most cases in which both the first and last strips of a hexagram survive in the manuscript, the symbols at the beginning and end of the text are identical. However, in three cases, the symbol at the end is different from that at the beginning. In the Shanghai Museum publication of the manuscript, Pu Maozuo devotes a special appendix to explaining the significance of the symbols, suggesting that red is a manifestation of the yang, or “sunny,” characteristic and black that of the yin, or “shady,” characteristic.75 With respect to the hexagrams in which the symbols differ, he suggests that they mark transitional stages in the respective growth and decline of the yin and yang. Ingenious though this explanation is, it has now been demonstrated conclusively that the strips that display this difference were written in a different hand from that of the other strips of the manuscript.76 This would seem to obviate any comparison between the symbols in the two different groups. At this point, it seems still premature to say just what these symbols were meant to represent and what, if anything, they suggest about the sequence of the hexagrams. It does seem safe to say, though, that the Shanghai Museum manuscript of the Changes will command the attention of people interested in the Changes for years to come. Chapter 2 presents, first, a detailed overview of the manuscript’s discovery and editing, its physical nature, and a comparison of its text with that of the received text; in chapter 3, I give a complete transcription and translation of the text, together with the received text and a translation of it as well.

The third of the great textual discoveries of 1993 was actually made before those of Guodian and the Shanghai Museum tombs, and a brief report of it was issued in short order.77 In March 1993, peasants digging a fishpond in the village of Wangjiatai 王家台, also in Hubei province, exposed a group of sixteen ancient tombs. Unlike Guodian, which lies to the north of the site of Jinan Cheng 紀南城, the Warring States capital of Chu, Wangjiatai lies just to the north of the site of Ying 郢, a new city established after 278 B.C. when Jinan Cheng was razed after being conquered by the northwestern state of Qin; the tombs uncovered there date to the half century or so after this date. The peasants immediately summoned archaeologists from the nearby Jingzhou Museum to conduct a salvage excavation of the tombs. In one of them, numbered M15, the archaeologists found inside its single coffin a wooden diviner’s board, bamboo sorting stalks placed in a bamboo canister, a number of dice, the haft of a dagger-axe, and, perhaps most important of all, a heap of bamboo strips with writing on them. Among the texts discovered were another daybook similar to that found in the contemporary tomb at Shuihudi; a text, to which the excavators gave the title Zai yi zhan 災異占, or Prognostications of Disasters and Anomalies; and two copies, apparently similar in content though written on bamboo strips of different sizes, of a text that the excavators first described simply as a divination text similar to but different from the Changes. When the brief report of this discovery was issued, in 1995, other scholars immediately identified this latter text as the long-lost Gui cang 歸藏, or Returning to Be Stored, traditionally supposed to have been the milfoil divination manual of the Shang dynasty and thus a precursor to the Changes.

The Gui cang was first mentioned in several Han-dynasty texts, though even then the imperial library apparently did not have a copy of it, and it is doubtful that many, if any, scholars of the time had actually seen it; certainly none ever quoted it, at least by name. This situation changed suddenly toward the end of the third and beginning of the fourth centuries, when first Zhang Hua 張華 (232–300) and then several other scholars quoted numerous passages from the text. Interestingly, Zhang Hua, probably the most erudite scholar of his day, did not attach a title to his quotations, and the quotations reveal a number of mistakes of the sort made by people unfamiliar with ancient script, suggesting perhaps that he was working with an ancient manuscript. Indeed, there is good reason to suspect that the text had just been unearthed in the first of the great Chinese discoveries of texts in tombs. In A.D. 279, a tomb in Jijun 汲郡, present-day Jixian 汲縣, Henan province, was broken into by tomb robbers. It is said that these robbers used some of the bundles of bamboo strips they found in the tomb as torches to light their way in quest of the tomb’s valuables.78 Nevertheless, when the imperial authorities arrived, they found that the tomb still contained “several tens of cartloads” of texts written on bamboo strips. These were taken to the imperial capital at Luoyang 洛陽, where a committee headed by Xun Xu 荀勖 (d. 289), the director of the imperial library, set to work transcribing them and trying to reconstitute the original texts. Of the eighteen or nineteen different texts in the tomb, only one was surely known to the editors: a copy of the hexagram and line statements of the Changes, said by one eyewitness to have been “just the same” (zheng tong 正同) as the received text. Three other texts were related to the Changes. One was called by one group of early editors Yi yao yin yang gua 易繇陰陽卦, or Yin-Yang Hexagrams of Yi Oracles. This text is described in the standard historical account of the discovery in almost the same terms used in the initial Wangjiatai site report for its text: “rather similar to the Zhou Yi but with different line statements” (yu Zhou Yi lüe tong yao ci ze yi 與周易略同繇辭則異).79 This is almost certainly the text that Zhang Hua quoted just a few years later, and which by the early fourth century would be identified as the Gui cang.

As shown in chapter 4, the Wangjiatai manuscripts are remarkably similar to the medieval quotations of the Gui cang; there can be no doubt that they come from the same book. Even though these texts are fragmentary, in this case even less well preserved than is typically the case with unearthed manuscripts, nevertheless by combining the Wangjiatai fragments with the medieval quotations, it is possible to arrive at a good sense of what the original text must have looked like. The text for Shi 師, “Army,” hexagram provides a good example of the Gui cang’s format.

師曰昔者穆天子卜出師西征而枚占于禺强禺强占之曰不吉龍降于天而道里修遠飛而冲天蒼蒼其羽

師曰昔者穆天子卜出師西征而枚占于禺强禺强占之曰不吉龍降于天而道里修遠飛而冲天蒼蒼其羽

Shi, “Army,” says: In the past Son of Heaven Mu divined about sending out the army to campaign westwardly and had the stalks prognosticated by Yu Qiang. Yu Qiang prognosticated them and said: Not auspicious. The Dragon descends from heaven, but the road is long and far; flying and piercing heaven, so green its wings.80

Shi, “Army,” says: In the past Son of Heaven Mu divined about sending out the army to campaign westwardly and had the stalks prognosticated by Yu Qiang. Yu Qiang prognosticated them and said: Not auspicious. The Dragon descends from heaven, but the road is long and far; flying and piercing heaven, so green its wings.80

Several points arise from even this single example. First, the names of the hexagrams in the Gui cang are, for the most part, identical to those in the Changes.81 Second, unlike the Changes, in which there are both hexagram statements and line statements for each of the six lines of a hexagram, the Gui cang includes only a single hexagram text. Most of these hexagram texts begin with the record of a divination conducted upon some occasion in history, as here in which King Mu of the Zhou dynasty (r. 956–918 B.C.) divined about sending his army on campaign. It is worth noting that this particular record shows that the traditional ascription of the Gui cang to the Shang dynasty is certainly erroneous; indeed, there are even later personages mentioned in the text, suggesting that its final redaction could not date any earlier than the middle of the Spring and Autumn period. The results of this divination are then prognosticated by some named diviner, often, as here in the case of Yu Qiang 禺强,82 a figure from high antiquity. As here, the prognostications in this text are often “not auspicious” (bu ji 不吉). Finally, also as here, comes a rhyming oracle, quite similar in format to some line statements of the Changes.

As an alternative divination manual to the Changes, the Gui cang not only provides still further information about the nature of divination in ancient China but also may well help to explain something of the development of the Changes itself. It too is a text that will surely command increasing attention in the years to come.83 I fully expect that the complete translation of the Gui cang fragments that I offer in chapter 5 will be but the first of numerous attempts to recover the text.

One of the most important things about the Gui cang is that it reminds us forcefully that the Changes was not the only divination text available in ancient China. In this respect, it is perhaps interesting to note that another text discovered in the tomb in Jijun in the late third century A.D., the Mu tianzi zhuan 穆天子傳 or Biography of Son of Heaven Mu, preserves a complete account of one divination with wording strikingly similar to several of the texts studied here. Although it is not explicitly related to the Gui cang, it mentions a milfoil divination that results in a hexagram, Song 訟, “Lawsuit,” the name of which is common to both the Changes and the Gui cang. The oracle quoted (and referred to as a zhou 繇) is not found in the received text of the Changes but does more or less resemble texts from the Gui cang. Whether it actually derives from the Gui cang or not, it may still help us to understand further the full context of divination and its interpretation, including how the final prognostications were made.

丙辰天子南遊于黃室之丘以觀夏侯啟之所居乃囗于啟室天子筮獵苹澤其卦遇訟 逢公占之曰訟之繇藪澤蒼蒼其中囗宜其正公戎事則從祭祀則熹田獵則獲囗飲逢公酒賜之駿馬十六絺紵三十箧逢公再拜稽首賜筮史狐 …

逢公占之曰訟之繇藪澤蒼蒼其中囗宜其正公戎事則從祭祀則熹田獵則獲囗飲逢公酒賜之駿馬十六絺紵三十箧逢公再拜稽首賜筮史狐 …