In contrast with the remarkable archaeological discoveries of the 1970s, the 1980s were relatively uneventful. This was as true of discoveries of bamboo-strip manuscripts as it was of other types of artifacts and texts. However, as described briefly in chapter 1, toward the end of the decade a discovery was made that would usher in a new field—and virtually a new era—in the study of early Chinese paleography and texts. In January 1987, a tomb was discovered at Baoshan 包山, Hubei, with 288 bamboo strips containing records of court cases and divinations, as well as an inventory of the goods contained in the grave. Unlike so many bamboo strips found in tombs, these were remarkably well preserved, and the archaeologists published them very expeditiously in 1991.1 What was especially noteworthy about these bamboo strips is that they showed beyond question that the person in whose tomb they were found, one Shao Tuo 召 , died in 316 B.C. Dating almost one hundred years before the Qin unification of China, a political event famed for the consequences it brought for the nature of writing and the transmission of books from ancient China, the Baoshan tomb texts were the first substantial body of writing on bamboo strips from China’s Warring States period, the period of the classical philosophers.2

, died in 316 B.C. Dating almost one hundred years before the Qin unification of China, a political event famed for the consequences it brought for the nature of writing and the transmission of books from ancient China, the Baoshan tomb texts were the first substantial body of writing on bamboo strips from China’s Warring States period, the period of the classical philosophers.2

Just two years after the publication of the Baoshan bamboo strips, two other tombs in the same general area—that of the capital of the important southern state of Chu 楚—were opened, eventually revealing many more bamboo strips from the Warring States period. More important, the strips from these tombs, now generally known as the Guodian 郭店 and Shanghai Museum (Shanghai Bowuguan 上海博物館, or Shangbo 上博 for short) bamboo strips, were primarily of philosophical and historical texts. The Guodian strips were the first of these to be published, immediately prompting international acclaim.3 First to draw attention were three different texts composed entirely of passages found in the received text of the Laozi 老子.4 Other texts mentioning Confucius or deriving from his followers, including the Zi yi 緇衣, or Black Jacket, corresponding to a chapter in the Li ji 禮記, or Record of Ritual, soon attracted even more attention.5 Since the other grave goods in the Guodian tomb were similar to those in the Baoshan tomb, and since the calligraphy on its bamboo strips was similar to that on the Baoshan strips, the archaeologists concluded that the tomb must date to about the same time, toward the end of the middle Warring States period, or roughly 300 B.C. Now, just over ten years after their first publication, the Guodian bamboo strips have already taken their place alongside the Mawangdui silk manuscripts as the best known of all Chinese excavated texts.

The Shanghai Museum bamboo strips have taken a more circuitous route to their public acclaim. Unlike other archaeological discoveries in China, which are generally known by the name of the village in which they were discovered, the Shanghai Museum strips are of more or less unknown provenance. They arrived on the Hong Kong antiques market early in 1994, apparently still bearing the mud of the tomb from which they had been robbed. Shortly after learning of their availability, the late Ma Chengyuan 馬承源 (1927–2004), then the director of the Shanghai Museum, arranged to buy them, first purchasing a batch of some four hundred strips in early March of that year and then, a month later, purchasing a second batch of some eight hundred strips.6 Over the next several years, the museum undertook the task of organizing these strips for publication. The first publication came at the end of 2001, a volume containing three texts: the Kongzi Shi lun 孔子詩論, or Confucius’s Essay on the Poetry, as well as two texts also found at Guodian: another copy of the Zi yi and another text variously known as Xing zi ming chu 性自命出, or The Inborn Nature Comes from the Mandate, or as Xing qing lun 性情論, Essay on the Inborn Nature and the Emotions.7 Succeeding volumes, issued at the rate of about one a year, have regularly presented five or six different texts, including additional texts found in the Li ji,8 a narrative of China’s earliest history (entitled Rong Cheng shi 容乘氏);9 a cosmological treatise (entitled Heng Xian 恆先);10 a text presenting dialogue between several disciples of Confucius (e.g., Zai Wo 宰我, Yan Hui 顏回, Zi Gong 子貢, et al.) and their “master” (zi 子), more or less similar to the Analects (Lun yu 論語) of Confucius (entitled by the editors Dizi wen 弟子問, or The Disciples Asked);11 as well as the text that concerns us in the remainder of this chapter: the earliest manuscript of the Zhou Yi 周易, or Zhou Changes, presently extant.12 Although the Shanghai Museum manuscripts are thus far more numerous and potentially much richer in content than either the Baoshan or even the Guodian bamboo-strip texts,13 their lack of a known archaeological context, combined with the fragmentary nature of many of the texts, presents many more problems of interpretation. Unfortunately, this is true also in the case of the Zhou Yi manuscript included in this corpus.

The Shanghai Museum Zhou Yi: Physical Description

The Shanghai Museum manuscript of the Zhou Yi was edited by Pu Maozuo 濮茅左, a senior curator at the museum.14 It includes fifty-eight strips, counting fragments that can be rejoined as a single strip (there is also one fragment in the possession of the Chinese University of Hong Kong that can be rejoined with strip no. 32 of the Shanghai Museum manuscript15). Forty-two of these strips are complete or nearly so, with an average length of 43.5 cm (the strips are 0.6 cm wide and 0.12 cm thick). The strips were originally bound with three binding straps (none of which survives, though vestiges of the silk can be seen on the bamboo strips) passing through notches cut into the right side of the strips: the top one 1.2 cm from the top, the middle one 22.2 cm from the top (21 cm from the top binding strap), and the bottom 1.2 cm from the bottom (20.5 cm from the middle notch). The first character of each strip begins just below where the first binding strap passed, and the last character ends just above where the last binding strap passed, with an average of forty-two to forty-four characters per complete strip. Each hexagram text begins on a new strip: first comes the hexagram picture (gua hua 卦劃; with yang lines written as 一 and yin lines written as ハ), with the six lines segregated into two groups of three lines each, an apparent indication of trigrams that is unique among early manuscripts; the hexagram name, many of which represent variants as opposed to those found in the received text (see table 2.1 for a listing of these and their correlates in the received text); one of several different symbols (a solid red square  ; a solid black square

; a solid black square  ; a three-sided hollow red square with an inset smaller solid black square

; a three-sided hollow red square with an inset smaller solid black square  ; a three-sided hollow black square with an inset smaller solid red square

; a three-sided hollow black square with an inset smaller solid red square  ; as well, perhaps, as a solid red square with an inset hollow black square

; as well, perhaps, as a solid red square with an inset hollow black square  ; and a three-sided hollow black square

; and a three-sided hollow black square  ) never before seen in connection with Yi jing hexagrams;16 the hexagram statement; the six line statements, beginning with chu liu 初六 or chu jiu 初九 and continuing through liu er 六二, jiu san 九三, and so forth until either shang liu 上六 or shang jiu 上九; and finally the same type of symbol found after the hexagram name. After this second symbol, the remainder of the final strip of any given hexagram is left blank. The fifty-eight strips include text from thirty-four different hexagrams, with 1,806 characters, as opposed to the sixty-four hexagrams and 5,012 characters of the received text. This constitutes just over one-third (36 percent) of the text. I estimate that eighty-four complete strips of the original manuscript are missing.

) never before seen in connection with Yi jing hexagrams;16 the hexagram statement; the six line statements, beginning with chu liu 初六 or chu jiu 初九 and continuing through liu er 六二, jiu san 九三, and so forth until either shang liu 上六 or shang jiu 上九; and finally the same type of symbol found after the hexagram name. After this second symbol, the remainder of the final strip of any given hexagram is left blank. The fifty-eight strips include text from thirty-four different hexagrams, with 1,806 characters, as opposed to the sixty-four hexagrams and 5,012 characters of the received text. This constitutes just over one-third (36 percent) of the text. I estimate that eighty-four complete strips of the original manuscript are missing.

An important feature of the manuscript, not mentioned in either the formal publication, Shanghai Bowuguan cang Zhan guo Chu zhu shu 上海博物館藏戰國楚竹書, or in my own preliminary introduction to it, is that it was obviously copied by at least two different copyists. Of the fifty-eight extant strips, forty-five (nos. 2–4, 6–7, 9–19, 28–36, 38–48, 50–58) share the same calligraphy and method of writing common graphs; we might term this Group A. However, as first pointed out by Fang Zhensan 房振三, the other thirteen strips (nos. 1, 5, 8, 20–27, 37, and 49) have a very different calligraphy and different ways of writing common graphs; we might term them Group B.17 This difference in calligraphy is particularly manifest between strip no. 48, which belongs to Group A, and strip no. 49, which belongs to Group B. As can be seen in figure 2.1, Group A features angular, narrow brush strokes, with little or no modulation in the thickness of the strokes, even at their ends. By contrast, Group B shows a bolder, more fluent calligraphic style, with rounded strokes that vary in thickness where the brush begins or stops. Differences in the writing of common graphs are also apparent in just these two strips, as for instance in the writing of qi 丌 (i.e., 其):  (no. 48) versus

(no. 48) versus  (no. 49), and liu 六:

(no. 49), and liu 六:  (no. 48) versus

(no. 48) versus  (no. 49). Elsewhere, systematic differences can be seen in the writing of bu 不:

(no. 49). Elsewhere, systematic differences can be seen in the writing of bu 不:  (Group A) versus

(Group A) versus  (Group B); li 利:

(Group B); li 利:  (Group A) versus

(Group A) versus  (Group B); and jiu 九:

(Group B); and jiu 九:  (Group A) versus

(Group A) versus  (Group B). Indeed, as He Zeheng 何澤恒 has further pointed out, within Group B there also seem to be some differences of handwriting. For instance, strips 26–27, which contain the text of Qin 欽 hexagram (which corresponds to Xian 咸 hexagram in the received text of the Zhou Yi), both feature the bold, curving calligraphy of Group B, but closer inspection reveals certain important differences, especially in the writing of the name of the hexagram:

(Group B). Indeed, as He Zeheng 何澤恒 has further pointed out, within Group B there also seem to be some differences of handwriting. For instance, strips 26–27, which contain the text of Qin 欽 hexagram (which corresponds to Xian 咸 hexagram in the received text of the Zhou Yi), both feature the bold, curving calligraphy of Group B, but closer inspection reveals certain important differences, especially in the writing of the name of the hexagram:  (no. 26, with six vertical strokes separated between top and bottom registers) versus

(no. 26, with six vertical strokes separated between top and bottom registers) versus  (no. 27, with three vertical strokes each running through a central horizontal stroke), and also in the difference between

(no. 27, with three vertical strokes each running through a central horizontal stroke), and also in the difference between  (no. 26, i.e., with an added horizontal stroke) and

(no. 26, i.e., with an added horizontal stroke) and  (no. 27) for the writing of qi 丌 (i.e., 其; though note that no. 26 includes both forms on a single strip); see figure 2.2.18

(no. 27) for the writing of qi 丌 (i.e., 其; though note that no. 26 includes both forms on a single strip); see figure 2.2.18

| NUMBER |

SHANGHAI MUSEUM MS. |

RECEIVED TEXT |

| 4 |

Mang 尨, “The Shaggy Dog” |

Meng 蒙, “Shrouded” |

| 5 |

Ru 乳, “Suckling” |

Xu 需, “Awaiting” |

| 6 |

Song 訟, “Lawsuit” |

Song 訟, “Lawsuit” |

| 7 |

Shi 帀, “Army” |

Shi 師, “Army” |

| 8 |

Bi 比, “Alliance” |

Bi 比, “Alliance” |

| 15 |

Qian  , “Modesty” , “Modesty” |

Qian 謙, “Modesty” |

| 16 |

Yu 余, “Excess” |

Yu 豫, “Relaxed” |

| 17 |

Sui  , “Following” , “Following” |

Sui 隨, “Following” |

| 18 |

Gu 蛊, “Parasite” |

Gu 蠱, “Parasite” |

| 24 |

Fu  , “Returning” , “Returning” |

Fu 復, “Returning” |

| 25 |

Wang Wang 亡忘, “Forget-Me-Not” |

Wu Wang 无妄, “Nothing Foolish” |

| 26 |

Da Du 大 , “Greater Enlargement” , “Greater Enlargement” |

Da Chu 大畜, “Greater Livestock” |

| 27 |

Yi 頤, “Jaws” |

Yi 頤, “Jaws” |

| 31 |

Qin 欽, “Careful” |

Xian 咸, “Feeling” |

| 32 |

Heng  , “Constant” , “Constant” |

Heng 恆, “Constant” |

| 33 |

Dun  , “Piglet” , “Piglet” |

Dun 遯, “Piglet” |

| 38 |

Kui 楑, “Looking Cross-Eyed” |

Kui 睽, “Strange” |

| 39 |

Jie 訐, “Criticized” |

Jian 蹇, “Lame” |

| 40 |

Jie 繲, “Disentangled” |

Jie 解, “Released” |

| 43 |

Guai 夬, “Resolute” |

Guai 夬, “Resolute” |

| 44 |

Gou 敂, “Hitting” |

Gou 姤, “Meeting” |

| 45 |

Cui  , “Roaring” , “Roaring” |

Cui 萃, “Gathering” |

| 47 |

Kun 困, “Bound” |

Kun 困, “Bound” |

| 48 |

Jing 汬, “Well Trap” |

Jing 井, “Well” |

| 49 |

Ge 革, “Rebellion” |

Ge 革, “Rebellion” |

| 52 |

Gen 艮, “Stilling” |

Gen 艮, “Stilling” |

| 53 |

Jian 漸, “Progressing” |

Jian 漸, “Progressing” |

| 55 |

Feng 豐, “Fullness” |

Feng 豐, “Fullness” |

| 56 |

Lü  , “Traveling” , “Traveling” |

Lü 旅, “Traveling” |

| 59 |

Huan  , “Dispersing” , “Dispersing” |

Huan 渙, “Dispersing” |

| 62 |

Shao Guo 少 , “Lesser Surpassing” , “Lesser Surpassing” |

Xiao Guo 小過, “Lesser Surpassing” |

| 63 |

Ji Ji 既淒, “Already Across” |

Ji Ji 既濟, “Already Across” |

| 64 |

Wei Ji 未淒, “Not Yet Across” |

Wei Ji 未濟, “Not Yet Across” |

As will become clear, the distinction between these two copyists has important implications for the analysis of the red and/or black symbols found at the beginning and end of the hexagram texts. It also raises interesting questions as to how and why the two or more different copyists worked. Were all the strips copied at the same time, with the two different copyists dividing the task of copying between them? Or were the copies made at two different times, the second copyist perhaps recopying portions of the text that had been lost or damaged? There is of course no way to be certain about either of these two possible scenarios. However, evidence that the second copyist either did not understand the nature of the red and/or black symbols or else had a different understanding of them from the first scribe perhaps suggests some temporal separation between the work of the two scribes. This of course has important implications for the question of whether the manuscript was copied expressly to be placed in the tomb or, as seems more likely, was used for some period of time before eventually being buried together with the occupant of the tomb, its likely owner.

The Red and/or Black Symbols and Their Significance

As mentioned, the most peculiar feature of the Shanghai Museum manuscript of the Zhou Yi is the symbols found immediately after the hexagram name and again after the last character of the last line statement of each hexagram. Pu Maozuo, the editor of the manuscript, contributed an appendix to explain the significance of these symbols, and several of the most detailed discussions of the manuscript published to date have also sought to find some logic behind their use.19 For this reason, it seems necessary to review here their presentations in some detail, even if such a review will almost inevitably be more or less confusing (especially without access to color printing) and even if there are serious deficiencies in the evidence available and flaws in most of the analyses. It is perhaps reasonable to begin by presenting the analysis given by Pu Maozuo.

Pu identifies six symbols. Without access to color printing, it is possible only to describe them and to use a gray scale to substitute for the red symbols in the following discussion (the order here being that used by Pu):  , a solid red square;

, a solid red square;  , a three-sided hollow red square (i.e., 匚) with an inset smaller solid black square;

, a three-sided hollow red square (i.e., 匚) with an inset smaller solid black square;  , a solid black square;

, a solid black square;  , a three-sided hollow black square with an inset smaller solid red square;

, a three-sided hollow black square with an inset smaller solid red square;  , a solid red square with an inset hollow black square; and

, a solid red square with an inset hollow black square; and  , a three-sided hollow black square. In all, there are seventeen hexagrams with symbols at both the beginning and end (in fourteen cases the symbols are identical, whereas in three cases they differ) and thirteen other hexagrams in which one or the other is visible (in all these cases, the part of the hexagram text where the other symbol would appear is missing because of a broken or missing strip). The distribution of these symbols is illustrated in table 2.2.

, a three-sided hollow black square. In all, there are seventeen hexagrams with symbols at both the beginning and end (in fourteen cases the symbols are identical, whereas in three cases they differ) and thirteen other hexagrams in which one or the other is visible (in all these cases, the part of the hexagram text where the other symbol would appear is missing because of a broken or missing strip). The distribution of these symbols is illustrated in table 2.2.

There is a decided (though not invariable) tendency to group these symbols with hexagrams in the sequence of the received text. Thus, Ru 孠,20 Song 訟, Shi 帀, and Bi 比 hexagrams, which correspond to the fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth hexagrams in the received sequence, are all marked with a solid red square  at both the head and tail, whereas Da You 大有 through Gu 蛊, the fourteenth through eighteenth hexagrams in the received sequence, all feature a solid black square

at both the head and tail, whereas Da You 大有 through Gu 蛊, the fourteenth through eighteenth hexagrams in the received sequence, all feature a solid black square  at the head and tail (though only the final portion of Da You and the opening portion of Gu are extant). There are three exceptions to this pattern: the three cases with mixed symbols (Da Chu 大

at the head and tail (though only the final portion of Da You and the opening portion of Gu are extant). There are three exceptions to this pattern: the three cases with mixed symbols (Da Chu 大 , Yi 頤, and Qin 欽, which correspond to hexagram numbers 26, 27, and 31 in the received sequence); hexagrams Ge 革 through Lü

, Yi 頤, and Qin 欽, which correspond to hexagram numbers 26, 27, and 31 in the received sequence); hexagrams Ge 革 through Lü  , numbers 49 through 56 in the received sequence, which have the same symbol—a hollow three-sided black square with an inset solid red square

, numbers 49 through 56 in the received sequence, which have the same symbol—a hollow three-sided black square with an inset solid red square  —as hexagrams Heng

—as hexagrams Heng  through Kui 楑, numbers 32 through 38; and Shao Guo 少

through Kui 楑, numbers 32 through 38; and Shao Guo 少 hexagram, number 62 in the received sequence (hereafter indicated as R62), which also has this same three-sided black square with an inset solid red square symbol, even though in the received sequence of hexagrams it comes between hexagrams Huan

hexagram, number 62 in the received sequence (hereafter indicated as R62), which also has this same three-sided black square with an inset solid red square symbol, even though in the received sequence of hexagrams it comes between hexagrams Huan  (R59) and Ji Ji 既淒 (R63), both of which have a different symbol (a solid red square with an inset hollow three-sided black square

(R59) and Ji Ji 既淒 (R63), both of which have a different symbol (a solid red square with an inset hollow three-sided black square  ). Pu suggests that the hexagrams with mismatched symbols must mark a transition between two different groups; thus, Da Chu (R26) with a solid black square at the head

). Pu suggests that the hexagrams with mismatched symbols must mark a transition between two different groups; thus, Da Chu (R26) with a solid black square at the head  and a hollow three-sided black square

and a hollow three-sided black square  at the tail must follow immediately after a group with solid black squares and come immediately before a group with hollow three-sided black squares (or, as he puts it, this hexagram simultaneously belongs to both groups). Similarly, Qin (R31), with a hollow three-sided black square

at the tail must follow immediately after a group with solid black squares and come immediately before a group with hollow three-sided black squares (or, as he puts it, this hexagram simultaneously belongs to both groups). Similarly, Qin (R31), with a hollow three-sided black square  at the head and a hollow three-sided black square with an inset solid red square

at the head and a hollow three-sided black square with an inset solid red square  at the tail must follow after the

at the tail must follow after the  group and come before the

group and come before the  group. On the basis of this premise, Pu concludes that there must be a sequence in which the hollow three-sided black square symbol precedes that of the hollow three-sided black square with an inset solid red square, and thus that Qin must follow after Da Chu.21 From this, he concludes that the

group. On the basis of this premise, Pu concludes that there must be a sequence in which the hollow three-sided black square symbol precedes that of the hollow three-sided black square with an inset solid red square, and thus that Qin must follow after Da Chu.21 From this, he concludes that the  group, including hexagrams from Da You (R14) through Wang Wang (R25), is concluded by Da Chu (R26), which serves as a transition to Qin (R31), which then is followed by the

group, including hexagrams from Da You (R14) through Wang Wang (R25), is concluded by Da Chu (R26), which serves as a transition to Qin (R31), which then is followed by the  group, represented in the extant manuscript by hexagrams from Heng (R32) through Shao Guo (R62). Pu explains this distribution by noting that the Zhou Yi has traditionally been divided into two scrolls (pian 篇), the first containing hexagrams Qian 乾 (R1) through Li 離 (R30) and the second Xian 咸 (R31) through Wei Ji 未濟 (R64). Since Xian is the first hexagram in this second scroll, Pu surmises that the

group, represented in the extant manuscript by hexagrams from Heng (R32) through Shao Guo (R62). Pu explains this distribution by noting that the Zhou Yi has traditionally been divided into two scrolls (pian 篇), the first containing hexagrams Qian 乾 (R1) through Li 離 (R30) and the second Xian 咸 (R31) through Wei Ji 未濟 (R64). Since Xian is the first hexagram in this second scroll, Pu surmises that the  symbol at the head of Qin (i.e., Xian) hexagram in the manuscript indicates a new scroll. By the same token, the

symbol at the head of Qin (i.e., Xian) hexagram in the manuscript indicates a new scroll. By the same token, the  symbol at the tail of Da Chu should indicate that it comes at the end of the first scroll. Pu further suggests that the four intervening hexagram texts in the received sequence, Yi 頤 no. 27, Da Guo 大過 no. 28, Kan 坎 no. 29, and Li, must have come at some other point in the text.

symbol at the tail of Da Chu should indicate that it comes at the end of the first scroll. Pu further suggests that the four intervening hexagram texts in the received sequence, Yi 頤 no. 27, Da Guo 大過 no. 28, Kan 坎 no. 29, and Li, must have come at some other point in the text.

| NUMBER |

HEXAGRAM NAME |

HEAD |

TAIL |

| 4 |

Mang 尨, “The Shaggy Dog” |

(faded) (faded) |

|

| 5 |

Ru 乳, “Suckling” |

|

|

| 6 |

Song 訟, “Lawsuit” |

|

|

| 7 |

Shi 帀, “Army” |

|

(faded) (faded) |

| 8 |

Bi 比, “Alliance” |

|

|

| 14 |

Da You 大有, “Great Offering” |

|

|

| 15 |

Qian  , “Modesty” , “Modesty” |

|

|

| 16 |

Yu 余, “Excess” |

|

|

| 17 |

Sui  , “Following” , “Following” |

|

|

| 18 |

Gu 蛊, “Parasite” |

|

|

| 25 |

Wang Wang 亡忘, “Forget-Me-Not” |

|

|

| 26 |

Da Du 大 , “Greater Enlargement” , “Greater Enlargement” |

|

|

| 27 |

Yi 頤, “Jaws” |

|

|

| 31 |

Qin 欽, “Careful” |

|

|

| 32 |

Heng  , “Constant” , “Constant” |

|

|

| 33 |

Dun  , “Piglet” , “Piglet” |

|

|

| 38 |

Kui 楑, “Looking Cross-Eyed” |

|

|

| 39 |

Jie 訐, “Criticized” |

|

|

| 40 |

Jie 繲, “Disentangled” |

|

|

| 43 |

Guai 夬, “Resolute” |

|

|

| 44 |

Gou 敂, “Hitting” |

|

|

| 45 |

Cui  , “Roaring” , “Roaring” |

|

|

| 47 |

Kun 困, “Bound” |

|

|

| 48 |

Jing 汬, “Well Trap” |

|

|

| 49 |

Ge 革, “Rebellion” |

|

|

| 52 |

Gen 艮, “Stilling” |

|

(faded) (faded) |

| 53 |

Jian 漸, “Progressing” |

|

|

| 55 |

Feng 豐, “Fullness” |

|

|

| 56 |

Lü  , “Traveling” , “Traveling” |

|

|

| 59 |

Huan  , “Dispersing” , “Dispersing” |

|

|

| 62 |

Shao Guo 少 , “Lesser Surpassing” , “Lesser Surpassing” |

|

|

| 63 |

Ji Ji 既淒, “Already Across” |

|

|

Pu proposes that the interplay between the black and the red in the symbols corresponds with the interplay between yin and yang in the hexagrams, black corresponding with yin and red with yang. According to Pu, when solid yang ( ) has spent its force, it gives rise to yin (

) has spent its force, it gives rise to yin ( ) within it. When yin matures, it reaches solidity (

) within it. When yin matures, it reaches solidity ( ), but then begins to wane and gives way to an incipient yang (

), but then begins to wane and gives way to an incipient yang ( ). The symbol

). The symbol  , a solid red square with an inset hollow three-sided black square, represents, according to Pu, “a transitional process, simultaneously indicating that events are turning within the transformation of yin and yang, that events are developing within the transformation of yin and yang, that events are entering a new cycle within the transformation of yin and yang.”22 He concludes his analysis by saying, “Because of missing strips in the Chu bamboo-strip Zhou Yi, I have made only an exploration and hypothesis of the circumstances presently available; if this is reasonable, then the Chu bamboo-strip Zhou Yi had a different sequence of hexagrams.”23 The sequence that he proposes is, as mentioned, in two scrolls: the first, Mang 尨 (R4); Ru 孠 (R5); Song 訟 (R6); Shi 帀 (R7); Bi 比 (R8); Jie 訐 (R39); Jie 繲 (R40); Guai 夬 (R43); Gou 敂 (R44); Cui

, a solid red square with an inset hollow three-sided black square, represents, according to Pu, “a transitional process, simultaneously indicating that events are turning within the transformation of yin and yang, that events are developing within the transformation of yin and yang, that events are entering a new cycle within the transformation of yin and yang.”22 He concludes his analysis by saying, “Because of missing strips in the Chu bamboo-strip Zhou Yi, I have made only an exploration and hypothesis of the circumstances presently available; if this is reasonable, then the Chu bamboo-strip Zhou Yi had a different sequence of hexagrams.”23 The sequence that he proposes is, as mentioned, in two scrolls: the first, Mang 尨 (R4); Ru 孠 (R5); Song 訟 (R6); Shi 帀 (R7); Bi 比 (R8); Jie 訐 (R39); Jie 繲 (R40); Guai 夬 (R43); Gou 敂 (R44); Cui  (R45); Kun 困 (R47); Jing 汬 (R48); Yi 頤 (R27); Da You 大有 (R14); Qian

(R45); Kun 困 (R47); Jing 汬 (R48); Yi 頤 (R27); Da You 大有 (R14); Qian  (R15); Yu 余 (R16); Sui

(R15); Yu 余 (R16); Sui  (R17); Gu 蛊 (R18); Fu

(R17); Gu 蛊 (R18); Fu  (R24); Wang Wang 亡忘 (R25); and Da Chu 大

(R24); Wang Wang 亡忘 (R25); and Da Chu 大 (R26); and the second, Qin 欽 (R31); Heng

(R26); and the second, Qin 欽 (R31); Heng  (R32); Dun

(R32); Dun  (R33); Kui 楑 (R38); Ge 革 (R49); Gen 艮 (R52); Jian 漸 (R53); Feng 豐 (R55); Lü

(R33); Kui 楑 (R38); Ge 革 (R49); Gen 艮 (R52); Jian 漸 (R53); Feng 豐 (R55); Lü  (R56); Shao Guo 少

(R56); Shao Guo 少 (R62); Huan

(R62); Huan  (R59); Ji Ji 既淒 (R63); and Wei Ji 未淒 (R64).

(R59); Ji Ji 既淒 (R63); and Wei Ji 未淒 (R64).

We owe Pu Maozuo a great deal for his careful editing and presentation of the manuscript. He was faced with an entirely new type of symbol, never before seen in the long tradition of Yi jing exegesis, and it was of course his responsibility as editor of the text to try to determine what meaning it might hold. However, it seems to me that the caution expressed in his conclusion is well warranted. It is plain to see that any of the missing strips could contain evidence that would overturn, or at least complicate, Pu’s analysis. Not only are both symbols missing for thirty-four hexagrams (middle portions of some of these hexagrams are available in the manuscript) but also there are thirteen cases in which either the head or tail symbol is missing (because of a broken or missing strip); in his analysis of these symbols, Pu seems to assume that in all thirteen of these cases the symbol must match that of the surviving symbol. The three cases with mismatched symbols might suggest that other hexagrams also had symbols that did not match.

A second systematic analysis of these red and black symbols is that of Li Shangxin 李尚信. Li begins by pointing out flaws in Pu Maozuo’s presentation, including several discrepancies between descriptions given in his study of the text (shiwen 釋文) and in the appendix devoted to the symbols. He also notes that although Pu argues for a hexagram sequence different from that of the received text, the sequence he suggests is thoroughly influenced by the received sequence. Li observes simply that there is too little evidence to support Pu’s reconstruction. In its place, he proposes that the manuscript’s sequence is essentially the same as that of the received text and further suggests a model for the sequence of the symbols. According to Li, hexagrams paired by virtue of their hexagram pictures (usually by inversion of the hexagram picture, as, for example, in the case of Shi 師  R7 and Bi 比

R7 and Bi 比  R8, or in the eight cases in which such inversion results in the same hexagram picture by conversion of all six lines to their opposite form, as in the case of Qian 乾

R8, or in the eight cases in which such inversion results in the same hexagram picture by conversion of all six lines to their opposite form, as in the case of Qian 乾  R1 and Kun 坤

R1 and Kun 坤  R2) always share the same symbol. On the other hand, Li goes on to suggest that different symbols must be given to hexagrams created by converting those hexagram pictures that can be inverted (i.e., changing all six lines to their opposite form; for example, Shi 師

R2) always share the same symbol. On the other hand, Li goes on to suggest that different symbols must be given to hexagrams created by converting those hexagram pictures that can be inverted (i.e., changing all six lines to their opposite form; for example, Shi 師  can be considered to convert into Tong Ren 同人

can be considered to convert into Tong Ren 同人  R13, whereas Bi 比

R13, whereas Bi 比  would convert into Da You 大有

would convert into Da You 大有  R14) or by exchanging top and bottom trigrams of hexagram pairs that cannot be inverted (e.g., Qian 乾

R14) or by exchanging top and bottom trigrams of hexagram pairs that cannot be inverted (e.g., Qian 乾  R1 and Kun 坤

R1 and Kun 坤  R2 exchange trigrams to produce Tai 泰

R2 exchange trigrams to produce Tai 泰  R11 and Pi 否

R11 and Pi 否  R12). Unfortunately, other than the pairs Shi and Bi and Tong Ren and Da You, there are only five hexagrams in the manuscript for which the convertible hexagram is present. In three cases (Mang 尨

R12). Unfortunately, other than the pairs Shi and Bi and Tong Ren and Da You, there are only five hexagrams in the manuscript for which the convertible hexagram is present. In three cases (Mang 尨  R4 and Ge 革

R4 and Ge 革  R49; Da Chu 大

R49; Da Chu 大 R26 and Cui

R26 and Cui  R45; and Kui 楑

R45; and Kui 楑  R38 and Jie 訐

R38 and Jie 訐  R39), Li’s analysis is accurate as stated. However, a fourth case, Sui

R39), Li’s analysis is accurate as stated. However, a fourth case, Sui

R17 and Gu 蛊

R17 and Gu 蛊  R18, is unusual in that the hexagram pictures are both invertible and convertible; that both hexagrams feature symbol

R18, is unusual in that the hexagram pictures are both invertible and convertible; that both hexagrams feature symbol  , would support the first of Li’s premises while negating the second. In the last of the cases, Feng 豐

, would support the first of Li’s premises while negating the second. In the last of the cases, Feng 豐  R55, which features the symbol

R55, which features the symbol  , and Huan

, and Huan

R59, the symbol of which both Pu Maozuo and Li Shangxin describe as

R59, the symbol of which both Pu Maozuo and Li Shangxin describe as  , the symbol

, the symbol  on Huan is very similar to the symbol

on Huan is very similar to the symbol  and may just represent a slight deformation of it.24 However we interpret this particular case, Li’s analysis would seem to be susceptible to the same sort of criticism as Pu Maozuo’s: the manuscript is simply too fragmentary to allow these sorts of fine distinctions.

and may just represent a slight deformation of it.24 However we interpret this particular case, Li’s analysis would seem to be susceptible to the same sort of criticism as Pu Maozuo’s: the manuscript is simply too fragmentary to allow these sorts of fine distinctions.

It seems to me that the most reasonable analysis of these symbols published to date is also the simplest. That is the analysis of He Zeheng, whom I mentioned regarding the attention he has paid to different calligraphic hands in the production of the manuscript. He suggests that in the forty-five strips that make up what I term Group A, there are only four different symbols (following Pu Maozuo’s ordering),  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . He suggests reordering these, such that the group of hexagrams with symbol

. He suggests reordering these, such that the group of hexagrams with symbol  , the solid black square, would follow immediately after the group with

, the solid black square, would follow immediately after the group with  , the solid red square, and those with

, the solid red square, and those with  , the three-sided hollow red square with an inset smaller solid black square, would precede those with symbol

, the three-sided hollow red square with an inset smaller solid black square, would precede those with symbol  , the three-sided hollow black square with an inset smaller solid red square. Then, somewhat along the lines of Pu’s nod to the traditional division of the Zhou Yi into two scrolls, He further suggests that

, the three-sided hollow black square with an inset smaller solid red square. Then, somewhat along the lines of Pu’s nod to the traditional division of the Zhou Yi into two scrolls, He further suggests that  and

and  , the solid red and black squares, would belong exclusively to the first scroll, and

, the solid red and black squares, would belong exclusively to the first scroll, and  and

and  would belong exclusively to the second scroll. In saying this, paradoxically, He comes to the same general conclusion as Li Shangxin: that these symbols suggest that the sequence of hexagrams in the manuscript was essentially the same as found in the received text.

would belong exclusively to the second scroll. In saying this, paradoxically, He comes to the same general conclusion as Li Shangxin: that these symbols suggest that the sequence of hexagrams in the manuscript was essentially the same as found in the received text.

The Hexagram Sequence in the Shanghai Museum Manuscript

The considerable interest evinced in these analyses of the manuscript’s red and black symbols is due in large part to the radically different sequence of hexagrams found on the Mawangdui silk manuscript vis-à-vis that of the received text. In the received text, the only apparent order in the sequence of hexagrams is that they are invariably grouped in pairs. In the twenty-eight cases in which a hexagram picture can be inverted to create a different hexagram picture, the two invertible hexagrams are paired together, as in the case of Shi 師  R7 and Bi 比

R7 and Bi 比  R8 mentioned above in the discussion of Li Shangxin’s analysis of the red and black symbols. In the eight cases in which such inversion would result in the same hexagram picture (Qian 乾

R8 mentioned above in the discussion of Li Shangxin’s analysis of the red and black symbols. In the eight cases in which such inversion would result in the same hexagram picture (Qian 乾  R1, Kun 坤

R1, Kun 坤  R2, Yi 頤

R2, Yi 頤  R27, Da Guo 大過

R27, Da Guo 大過  R28, Kan 坎

R28, Kan 坎  R29, Li 離

R29, Li 離  R30, Zhong Fu 中孚

R30, Zhong Fu 中孚  R61, and Xiao Guo 小過

R61, and Xiao Guo 小過  R62), the hexagram is paired with the hexagram created by the conversion of all lines to their opposite.25 Many of these hexagram pairs are also related by their names (often being opposites of each other) and/or similar line statements. As explained in chapter 1, in the Mawangdui silk manuscript, on the other hand, the hexagrams are arranged in groups of eight, with all hexagrams in a single group sharing the same top three lines, or trigram. Thus, the first eight hexagrams of the Mawangdui manuscript are built around the trigram Qian 乾 ☰ (called Jian 鍵 in the Mawangdui manuscript). In the illustration below, above the hexagram picture I give the names and sequence numbers found in the manuscript; below it I give the names and sequence numbers found in the received text):26

R62), the hexagram is paired with the hexagram created by the conversion of all lines to their opposite.25 Many of these hexagram pairs are also related by their names (often being opposites of each other) and/or similar line statements. As explained in chapter 1, in the Mawangdui silk manuscript, on the other hand, the hexagrams are arranged in groups of eight, with all hexagrams in a single group sharing the same top three lines, or trigram. Thus, the first eight hexagrams of the Mawangdui manuscript are built around the trigram Qian 乾 ☰ (called Jian 鍵 in the Mawangdui manuscript). In the illustration below, above the hexagram picture I give the names and sequence numbers found in the manuscript; below it I give the names and sequence numbers found in the received text):26

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

| Jian |

Fu |

Yuan |

Li |

Song |

Tong Ren |

Wumeng |

Gou |

| 鍵 |

婦 |

掾 |

禮 |

訟 |

同人 |

无孟 |

狗 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 乾 |

否 |

遯 |

履 |

訟 |

同人 |

无妄 |

姤 |

| Qian |

Pi |

Dun |

Lü |

Song |

Tong Ren |

Wuwang |

Gou |

| 1 |

12 |

33 |

10 |

6 |

13 |

25 |

44 |

As mentioned in chapter 1, the initial publication of this manuscript touched off a furious debate over which sequence may have been the original sequence of the Zhou Yi. Although the Mawangdui manuscript constituted the earliest physical evidence, many scholars held that its mechanical arrangement disrupted the pairs of hexagrams, which they regarded as one of the fundamental organizing features of the text.

Thus it was that people heard with excitement the news that the Shanghai Museum had obtained a manuscript more than a century older than the Mawangdui manuscript and looked forward to its publication to resolve this debate. Alas, the physical nature of the Shanghai Museum manuscript—being copied on bamboo strips—has frustrated this hope. As noted, each hexagram begins at the top of a new strip, with the text then continuing on a second, or in some cases a third strip, with any remnant of the final strip left blank after the final red and/or black symbol. There is clear evidence that all the strips were then bound together and thus that the hexagrams certainly had a fixed sequence when the manuscript was put into the tomb. However, by the time the manuscript reached the Shanghai Museum, the binding straps had long since decomposed, and the individual strips had become jumbled. For this reason, it is now generally assumed that, with the possible exception of the evidence of the red and/or black symbols, it is impossible to determine the original sequence of the bamboo-strip manuscript and consequently that the manuscript does not provide any evidence for the original sequence of hexagrams in the Zhou Yi.

This is certainly a reasonable assumption in principle. However, several years ago I proposed that it may be possible to use some aspects of the physical nature of the bamboo strips to come to some very provisional conclusions about the sequence of the manuscript.27 If we assume that the strips were buried in a bound bundle or bundles, as the traces of the binding straps on the bamboo strips would suggest, we might also assume a greater than average possibility that contiguous strips would be preserved or lost together. Table 2.3 presents the physical circumstances and contents of the fifty-eight strips presently known.

Some observations are possible from table 2.3. First, whenever there is a break, either at the beginning or the end of a given hexagram text, the hexagram preceding or following it in the received sequence of hexagrams is missing. For instance, the manuscript includes the final strip of Mang 尨, hexagram R4 in the received sequence, but not its first strip; it does not include any of Zhun 屯 (R3). Similarly, it includes the final strip of Da You 大有 (R14) but not its beginning strip; neither does it include any text of Tong Ren 同人 (R13). It includes the first strip of Gu 蛊 (R18) but not its last strip; neither does it include any text of Lin 臨 (R19). This is true in every case in which a hexagram text is incomplete, except for the single case of Shao Guo 少 (R62) and Ji Ji 既

(R62) and Ji Ji 既 (R63); the second strip of Ji Ji is present but not its first strip, while the third of what must originally have been three strips of Shao Guo is present. As already noted, it is also the case that the symbol that comes at the end of Shao Guo seems to be out of sequence with the hexagrams that precede and follow it in the received sequence (see table 2.2).

(R63); the second strip of Ji Ji is present but not its first strip, while the third of what must originally have been three strips of Shao Guo is present. As already noted, it is also the case that the symbol that comes at the end of Shao Guo seems to be out of sequence with the hexagrams that precede and follow it in the received sequence (see table 2.2).

| STRIP NO. |

LENGTH (CM) |

HEX. NAME |

NO IN R. |

CONTENTS |

| 1 |

16.7 + 12.4 + 9.6 |

Mang 尨 |

4 |

Liu san to end |

| 2 |

23.1 + 20.4 |

Ru 孠 |

5 |

Beginning to liu si |

| 3 |

gap—20.8 |

Ru |

5 |

Last character plus symbol |

| 4 |

23.2 + 20.6 |

Song 訟 |

6 |

Beginning to jiu er |

| 5 |

43 |

Song |

6 |

Liu san to shang jiu |

| 6 |

43.3 |

Song |

6 |

Shang jiu to end |

| 7 |

43.6 |

Shi 帀 |

7 |

Beginning to liu si |

| 8 |

34.7 |

Shi |

7 |

Liu si to end |

| 9 |

43.5 |

Bi 比 |

8 |

Beginning to liu san |

| 10 |

43.7 |

Bi |

8 |

Liu san to end |

| 11 |

43.8 |

(Da You 大有) |

14 |

Liu si to end |

| 12 |

12.4 + 8.7—gap—10.8 |

Qian  |

15 |

Beginning to liu wu |

| 13 |

43.8 |

Qian |

15 |

Liu wu to end |

| 14 |

43.3 |

Yu 余 |

16 |

Beginning to liu wu |

| 15 |

43.8 |

Yu |

16 |

Liu wu to end |

| 16 |

42.7—gap |

Sui  |

17 |

Beginning to jiu si |

| 17 |

43.5 |

Sui |

17 |

Jiu si to end |

| 18 |

43.5 |

Gu 蛊 |

18 |

Beginning to jiu san |

| 19 |

gap—7—gap |

Fu  |

24 |

Liu wu |

| 20 |

29.1—gap |

Wang Wang 亡忘 |

25 |

Beginning to liu er |

| 21 |

22.1 + 6.7 + 15 |

Wang Wang |

25 |

Liu san to end |

| 22 |

43.7 |

Da Du 大 |

26 |

Beginning to liu si |

| 23 |

43.7 |

Da Du |

26 |

Liu si to end |

| 24 |

43.4 |

Yi 頤 |

27 |

Beginning to liu san |

| 25 |

43.7 |

Yi |

27 |

Liu san to end |

| 26 |

36.5—gap |

Qin 欽 |

31 |

Beginning to jiu si |

| 27 |

43.6 |

Qin |

31 |

Jiu wu to end |

| 28 |

43.6 |

Heng  |

32 |

Beginning to liu wu |

| 29 |

43.8 |

Heng |

32 |

Liu wu to end |

| 30 |

31.5 + 12 |

Dun  |

33 |

Beginning to jiu si |

| 31 |

31.1—gap |

Dun |

33 |

Jiu si to end |

| 32 |

21.8 + 9.2—gap |

Kui 楑 |

38 |

Beginning to liu san |

| 32a* |

? |

Kui |

38 |

Liu san to jiu si |

| 33 |

30.8—gap |

Kui |

38 |

Jiu si to shang jiu |

| 34 |

43.5 |

Kui |

38 |

Shang jiu to end |

| 35 |

43.6 |

Jie 訐 |

39 |

Beginning to jiu wu |

| 36 |

36—gap |

Jie |

39 |

Shang liu to end |

| 37 |

43.5 |

Jie 繲 |

40 |

Beginning to jiu si |

| 38 |

43.7 |

Guai 夬 |

43 |

Jiu er to jiu si |

| 39 |

43.7 |

Guai |

43 |

Jiu si to end |

| 40 |

13 + 30.5 |

Gou 敂 |

44 |

Beginning to jiu san |

| 41 |

43.8 |

Gou |

44 |

Jiu san to end |

| 42 |

43.6 |

Cui  |

45 |

Beginning to chu liu |

| 43 |

43.8 |

Kun 困 |

47 |

Jiu wu to end |

| 44 |

43.7 |

Jing 汬 |

48 |

Beginning to jiu er |

| 45 |

43.6 |

Jing |

48 |

Jiu er to shang liu |

| 46 |

43.5 |

Jing |

48 |

Shang liu to end |

| 47 |

43.7 |

Ge 革 |

49 |

Beginning to jiu san |

| 48 |

13.4—gap—23.8 |

Gen 艮 |

52 |

Beginning to jiu san |

| 49 |

43.8 |

Gen |

52 |

Jiu san to end |

| 50 |

12.6 + 31.1 |

Jian 漸 |

53 |

Beginning to jiu san |

| 51 |

23.1 + 20.5 |

Feng 豐 |

55 |

Jiu san to shang liu |

| 52 |

43.5 |

Feng |

55 |

Shang liu to end |

| 53 |

43.8 |

Lü  |

56 |

Beginning to jiu si |

| 54 |

43.5 |

Huan  |

59 |

Beginning to liu si |

| 55 |

gap—42.7 |

Huan |

59 |

Liu si to end |

| 56 |

31.6—gap |

Shao Guo 少 |

62 |

Liu wu to end |

| 57 |

43.6 |

(Ji Ji 既淒) |

63 |

Jiu san to end |

| 58 |

gap—21—gap |

Wei Ji 未淒 |

64 |

Chu liu to jiu si |

* This fragment is stored in the Chinese University of Hong Kong; exact measurements are not available.

By the same token, when the beginning or final strip of a hexagram text is present, there is a much better than average chance that the preceding or following hexagram in the received sequence is also present. For example, the manuscript includes both the beginning and end of Ru 孠 (R5); it also includes the final strip of Mang 尨 (R4) and the first strip of Song 訟 (R6). The manuscript includes both the beginning and end of Qian  (R15); it also includes the end of Da You 大有 (R14) and the beginning of Yu 余 (R16). In fifty such cases, there are only ten cases in which the text that would be contiguous in the received sequence is not present. Despite the problem of double counting here (the single correlation between the end of Qian and the beginning of Yu gets counted twice, once for Qian and once for Yu), these statistics suggest to me the probability that these bamboo strips were indeed contiguous.

(R15); it also includes the end of Da You 大有 (R14) and the beginning of Yu 余 (R16). In fifty such cases, there are only ten cases in which the text that would be contiguous in the received sequence is not present. Despite the problem of double counting here (the single correlation between the end of Qian and the beginning of Yu gets counted twice, once for Qian and once for Yu), these statistics suggest to me the probability that these bamboo strips were indeed contiguous.

Refining this analysis somewhat, noting that many of the bamboo strips in the manuscript were broken at some point during their burial, we might also assume that these strips would have been broken in much the same place with other strips that were contiguous in the bundle or bundles. Evidence of this is to be seen, for instance, in the case of strips 20 and 21, the first of which is broken 29.1 cm from the top and the second of which is broken at 28.8 cm from the top (and also at 22.1 cm from the top)—these two strips contain the entirety of Wang Wang 亡忘 (R25), the contents of which show that the two strips must have been contiguous. Similar evidence can be seen in the cases of strips 30 and 31, the first of which is broken at 31.5 cm from the top and the second at 31.1 cm from the top—these two strips contain the entirety of Dun  (R33), and strips 32 and 33, the first of which is broken at 31 cm from the top and the second at 30.8 cm from the top—these are the first two strips of Kui 楑 (R38).28 In these two cases as well, the content of the strips shows that they must have been contiguous, and so the similar points of breakage are perhaps understandable.

(R33), and strips 32 and 33, the first of which is broken at 31 cm from the top and the second at 30.8 cm from the top—these are the first two strips of Kui 楑 (R38).28 In these two cases as well, the content of the strips shows that they must have been contiguous, and so the similar points of breakage are perhaps understandable.

More important, strips pertaining to more than a single hexagram might be susceptible to the same type of analysis. Thus, we might note that strips 2, 3, and 4 were all broken in roughly the same place, at about the point of the middle binding notch: strip 2 being broken 20.4 cm from the bottom, strip 3 20.8 cm from the bottom, and strip 4 20.6 cm from the bottom. The first two of these three strips would have contained the entirety of the text of Ru 孠 (R5),29 while the third contains the opening of Song 訟 (R6). The similar points of breakage suggest that these strips, and thus the two hexagrams, were contiguous in the manuscript sequence, just as they are in the received sequence.30

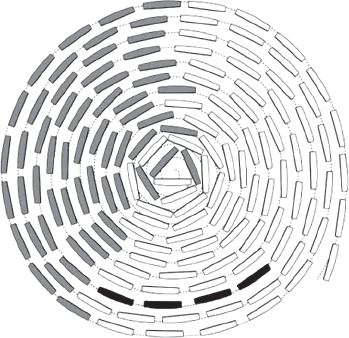

Thus, both the distribution of extant strips among the hexagrams and especially this last example of similar points of breakage of strips belonging to two different hexagrams suggested to me that the Shanghai Museum manuscript of the Zhou Yi may well have been more or less in the same sequence as that of the received text. More recently, Sun Peiyang 孫沛陽 of Peking University’s Institute of Archaeology and Museology (Kaogu Wenbo Xueyuan 考古文博學院) has proposed a much more audacious—and to my mind—much more convincing demonstration that the original sequence of hexagrams of the Shanghai Museum manuscript was the same as that of the received text.31 Sun assumes that the text of the Zhou Yi was written on 142 bamboo strips, which agrees with my own reconstruction of the original manuscript. He has reproduced these in cardboard strips 45 cm long by 0.6 cm wide and with a thickness of 0.11–0.12 cm, pasting onto 58 of these strips full-size photographs of the surviving text. He colored these strips gray and used white for the strips entirely missing from the manuscript. He then bound these all together, with thin silk thread, in the order of the received text, and rolled them into a scroll, rolling from back (i.e., what would correspond to Wei Ji 未濟 [R64] hexagram) to front, so that Qian 乾 (R1) would be the last hexagram on the outside of the scroll. This initial experiment produced a scroll that can be depicted as in figure 2.3.

This diagram is immediately suggestive, with the surviving strips (in gray) all segregated on one side of the scroll. However, Sun has proposed a slight modification. He notes that the seventy-seven strips of the Yongyuan qiwu pu 永元器物簿 discovered at Juyan about 1930, one of the only early scrolls that has survived intact, included two blank strips that mark divisions within the text.32 If the Zhou Yi manuscript were divided—as the Zhou Yi has been traditionally—into two sections, then perhaps it would have included one or more blank strips bound into the scroll. Since the Zhou Yi has traditionally been divided between Li 離 R30 and Xian 咸 R31 hexagrams, Sun placed four extra strips at that point in the scroll. This produces the schematic diagram (the four blank strips indicated in black) shown in figure 2.4.

In his discussion of this reconstruction, Sun is very careful to note its hypothetical nature. Especially problematic is the insertion of four blank strips into the middle of the scroll. Nevertheless, the result is particularly satisfying, suggesting forcefully not only that the Shanghai Museum Zhou Yi manuscript was indeed bound in the order of the received text but also that it was divided into two separate sections (though bound as a single text).

The Manuscript Text as Compared with the Received Text of the Zhou Yi

As mentioned, the manuscript contains text from thirty-four different hexagrams, with 1,806 characters, as opposed to the sixty-four hexagrams and 5,012 characters of the received text. For the one-third of the text for which there are parallels, the manuscript and received text match to a quite remarkable extent. Consider, for example, its text of Shi 帀 hexagram, which corresponds with the received text’s Shi 師, “Army,” hexagram (the seventh hexagram in the received sequence), which is written on the seventh and eighth strips of the manuscript (see figures 2.1 and 2.2). I give here the text as written on the two strips and as presented in Shanghai Bowuguan cang Zhanguo Chu zhu shu and beneath this (in gray) the received text (as found in the Shisan jing zhushu 十三经注疏 edition, minus punctuation):

7.  帀

帀 貞丈人吉亡咎初六帀出以聿不

貞丈人吉亡咎初六帀出以聿不 凶九二才帀

凶九二才帀 吉亡咎王晶賜命六晶帀或

吉亡咎王晶賜命六晶帀或 凶六四帀左

凶六四帀左 亡咎六

亡咎六

師 貞丈人吉无咎初六師出以律否臧凶九二在師中吉无咎王三錫命六三師或輿尸凶六四師左次无咎六

師 貞丈人吉无咎初六師出以律否臧凶九二在師中吉无咎王三錫命六三師或輿尸凶六四師左次无咎六 8. 五畋又 利

利 言亡咎長子

言亡咎長子 帀弟子

帀弟子 貞凶上六大君子又命啟邦丞

貞凶上六大君子又命啟邦丞 勿用

勿用

五田有禽利執言无咎長子帥師弟子輿尸貞凶上六大君有命開國承家小人勿用

With the exception of the red symbol found at the beginning of the manuscript text ( ; represented here with A; the complementary symbol that we would expect to find at the end of the text seems to have faded entirely), it can be seen that the two texts coincide almost character for character, the only obvious differences being that the received text does not have the suffix zi 子 after da jun 大君 in the Top Six line statement, and in the same line statement the manuscript writes xiao ren 小人 as the combined character (hewen 合文)

; represented here with A; the complementary symbol that we would expect to find at the end of the text seems to have faded entirely), it can be seen that the two texts coincide almost character for character, the only obvious differences being that the received text does not have the suffix zi 子 after da jun 大君 in the Top Six line statement, and in the same line statement the manuscript writes xiao ren 小人 as the combined character (hewen 合文)  . When we look more closely, we see that of the seventy-three other characters in the hexagram and line statements forty are exact matches.33 Of the variations, 亡 : 无 (four times),

. When we look more closely, we see that of the seventy-three other characters in the hexagram and line statements forty are exact matches.33 Of the variations, 亡 : 无 (four times),  : 師 (five times), 聿 : 律, 不 : 否,

: 師 (five times), 聿 : 律, 不 : 否,  : 臧, 才 : 在,

: 臧, 才 : 在,  : 中, 晶 : 三 (two times), 賜 : 錫,

: 中, 晶 : 三 (two times), 賜 : 錫,  : 輿 (two times),

: 輿 (two times),  : 尸 (two times),

: 尸 (two times),  : 次, 畋 : 田, 又 : 有 (two times),

: 次, 畋 : 田, 又 : 有 (two times),  : 禽,

: 禽,  : 執,

: 執,  : 帥, 啟 : 開, 邦 : 國, 丞 : 承,

: 帥, 啟 : 開, 邦 : 國, 丞 : 承,  : 家, most are clearly just graphic variants, different ways of writing the same word, not much different from the difference between English “theater” and “theatre.” For instance, in Warring States manuscripts,

: 家, most are clearly just graphic variants, different ways of writing the same word, not much different from the difference between English “theater” and “theatre.” For instance, in Warring States manuscripts,  is the standard way of writing the word shi, “army, regiment,” the conventional form of which came first to be written as 師, though it is now simplified as 师; the difference between

is the standard way of writing the word shi, “army, regiment,” the conventional form of which came first to be written as 師, though it is now simplified as 师; the difference between  and 師 is of the same order as the difference between 師 and 师. The same is true of the differences between at least 才 and 在 and 又 and 有. The difference between 晶 and 三 is of a similar nature; although in conventional Chinese orthography 晶 would ordinarily represent the word jing, “crystal,” in Warring States Chu manuscripts the word for “three” is often written with three repeated elements, such as the three “suns” (日) here. Most of the other variants are well attested in other paleographic materials or in later dictionaries as alternative forms, different spellings so to speak, for the characters found in the received text.34

and 師 is of the same order as the difference between 師 and 师. The same is true of the differences between at least 才 and 在 and 又 and 有. The difference between 晶 and 三 is of a similar nature; although in conventional Chinese orthography 晶 would ordinarily represent the word jing, “crystal,” in Warring States Chu manuscripts the word for “three” is often written with three repeated elements, such as the three “suns” (日) here. Most of the other variants are well attested in other paleographic materials or in later dictionaries as alternative forms, different spellings so to speak, for the characters found in the received text.34

The difference between 畋 and 田 might point to a different nuance, since 畋 conventionally represents the word tian, “to hunt,” whereas 田 is obviously in the same word family but usually stands specifically for tian, “fields.” However, as early as the oracle-bone inscriptions of the Shang dynasty, 田 was also used in the sense “to hunt,” perhaps derived from “to take to the fields.” The variation between the manuscript’s 亡, usually read as wang, “to die, not to exist,” and the received text’s wu 无, “not to have, not to be,” might well point to a change in the use of negatives at some point between the Warring States period and the Han dynasty, but many grammarians simply read 亡 as wu and equate the two words. Only the received text’s kai 開, “to open,” for the manuscript’s qi 啟, “to initiate,” and guo 國, “state,” for the manuscript’s bang 邦, “country,” are clearly lexical variants, and these are well-known in all ancient texts as being due to editorial changes in the Han dynasty to avoid taboos on the names of the early Han emperors Liu Bang 劉邦 (r. 202–195 B.C., posthumously known as Gao Di 高帝) and Liu Qi 劉啓 (r. 157–141 B.C., posthumously known as Jing Di 景帝).35

This is not to say, by any means, that the manuscript text is exactly the same as the received text of the Zhou Yi. Most of the variants are, of course, of the nature seen above in the case of Shi hexagram—“ancient script” (gu wen 古文) forms versus “clerical script” (li shu 隸書) forms or variants that are phonetically related, essentially different spellings of the same word (which, however, can sometimes also suggest different words). However, there are quite a few cases where we find two clearly different words. In several of these cases, it is possible to use the reading of the Shanghai Museum manuscript, especially in conjunction with other early evidence (especially the Mawangdui and Fuyang 阜陽 manuscripts), to suggest different readings from those of the received text. Here I introduce just two representative cases; others are addressed in the notes to the translation presented in the following chapter.36

Some of the most interesting differences are clearly a result of miscopying or mistranscription of archaic forms of characters. For example, the Six in the Fifth line of Kui 楑, “Look Cross-Eyed” (R38), hexagram reads as follows in the Shanghai Museum manuscript and in the received text (the received text in gray):

Six in the Fifth: Regrets gone. Ascend the ancestral temple and eat the meat offering. In going what trouble.

六五悔亡厥宗噬膚往何咎

Six in the Fifth: Regrets gone. At their ancestral temple eating flesh. In going what trouble.

Disregarding for the moment all other variants (which are possibly just graphic variants),37 let us focus just on the difference between the 陞 of the manuscript, clearly an embellished form of sheng 升, “to ascend,” and the jue 厥, “his, its” of the received text. It is hard to construe the grammar of the received text, in which it would seem that the “ancestral temple” eats the “flesh,” a difficulty not apparent in the manuscript text; in “ascend the ancestral temple and eat the meat offering,” there is no need to specify, with a pronoun, who is to perform the action. The preferability of the manuscript reading is shown by that of the Mawangdui manuscript, which reads here deng zong 登宗, “go up the ancestral temple,” sheng 升, “to ascend,” and deng 登, “to go up,” being close synonyms. As Qin Jing 秦倞 has pointed out, there is probably a graphic explanation for the reading of the received text: the archaic form of jue 厥, “his, its,” was 氒, very similar to 升, the original form of sheng, “to ascend.”38

The Shanghai Museum manuscript version of the Nine in the Fourth line of Guai 夬, “Resolute,” hexagram (R43) contains numerous variants vis-à-vis the received text.

Nine in the Fourth: The raw meat offering has no sliced meat. His movement is belabored. Losing a sheep. Regrets gone. Hearing words that are unending.

四臀无膚其行次且牽羊悔亡聞言不信

四臀无膚其行次且牽羊悔亡聞言不信Nine in the Fourth: Buttocks without flesh. His movement is labored. Leading a sheep. Regrets gone. Hearing words that are not believable.

Let us once again focus only on a single variant. This is the variation between the  羊 of the manuscript and qian yang 牽羊, “to lead a sheep,” of the received text. Pu Maozuo does not comment here on the graph

羊 of the manuscript and qian yang 牽羊, “to lead a sheep,” of the received text. Pu Maozuo does not comment here on the graph  , but at another occurrence of it (at the First Nine line statement of Kui 楑, “Look Cross-Eyed,” hexagram [R 38]), he suggests, without any elaboration, that it should be read as sang 喪, “to lose,” as does the received text.39

, but at another occurrence of it (at the First Nine line statement of Kui 楑, “Look Cross-Eyed,” hexagram [R 38]), he suggests, without any elaboration, that it should be read as sang 喪, “to lose,” as does the received text.39

First Nine: Regrets gone. Losing a horse; do not follow, it will return of itself. Seeing an ugly man; there is no trouble.

初九悔亡喪馬勿逐自復見惡人无咎

First Nine: Regrets gone. Losing a horse; do not chase it, it will return of itself. Seeing an ugly man; there is no trouble.

In the Nine in the Fourth line of Guai hexagram, both readings, sang yang 喪羊, “to lose a sheep,” and qian yang 牽羊, “to lead a sheep,” are intelligible in the context. In this case, the Mawangdui manuscript seemed to support the reading of the received text, published transcriptions of the manuscript rendering this phrase as qian yang 牽羊.40 However, Fan Changxi 范常喜 has recently challenged this reading, suggesting on the basis of the Shanghai Museum Zhou Yi manuscript and other early manuscript materials that the Mawangdui manuscript should actually be transcribed as sang yang 桑羊 but read as sang yang 喪羊, “to lose a sheep,” sang 桑, “mulberry,” and sang 喪, “to lose,” being homophonous.41 More than just homophonous, paleographic materials have long since shown that the graph for sang, 喪, “to lose,” was originally written with sang 桑, “mulberry,” as the phonetic component, adding wang 亡, “to die, not to have,” as the etymonic component. In the case of the graph in question in the Shanghai Museum manuscript, it would seem that the component transcribed as 九 by Pu Maozuo is, in fact, a simplified form of 桑, displaying only the “trunk” of the tree and leaving off the “berries.”42 Thus, it is clear here that the character  should be read as sang 喪, “to lose.” However, it is likely that some sort of variant writing of the character form eventually led to the received text’s qian 牽, “to lead.”43

should be read as sang 喪, “to lose.” However, it is likely that some sort of variant writing of the character form eventually led to the received text’s qian 牽, “to lead.”43

In addition to variations in individual characters, it is worth noting also that the manuscript occasionally differs from the received text in its use of technical divination terminology. There are six places where the manuscript contains an additional word or phrase as compared with the received text: ji 吉, “auspicious,” in the hexagram statement of Bi 比 (R8); wang bu li 亡不利, “there is nothing not beneficial,” in the Six in the Fourth line of Bi; zhen 貞, “to divine,” in the Top Six line of Heng  (R32); li jian da ren, “beneficial to see the great man,” in the hexagram statement of Huan

(R32); li jian da ren, “beneficial to see the great man,” in the hexagram statement of Huan  hexagram (R57); hui wang 悔亡, “regrets gone,” in the First Six line of Huan; and li she da chuan 利涉大川, “beneficial to ford the great river,” in the Nine in the Third line of Wei Ji 未淒 (R64). There are also almost twice as many places in which the received text includes similar technical divination terms or phrases of which the manuscript shows no trace.44 This may reflect a sort of process of composition for the text of the Zhou Yi as seen, for instance, in the additional divination terms in the Fuyang Zhou Yi manuscript,45 though it must also be admitted that the great majority of the received text’s divination phrases are seen in the Shanghai Museum manuscript, showing that even in this perhaps most fluid of aspects, the text was already more or less fixed by no later than 300 B.C.

hexagram (R57); hui wang 悔亡, “regrets gone,” in the First Six line of Huan; and li she da chuan 利涉大川, “beneficial to ford the great river,” in the Nine in the Third line of Wei Ji 未淒 (R64). There are also almost twice as many places in which the received text includes similar technical divination terms or phrases of which the manuscript shows no trace.44 This may reflect a sort of process of composition for the text of the Zhou Yi as seen, for instance, in the additional divination terms in the Fuyang Zhou Yi manuscript,45 though it must also be admitted that the great majority of the received text’s divination phrases are seen in the Shanghai Museum manuscript, showing that even in this perhaps most fluid of aspects, the text was already more or less fixed by no later than 300 B.C.

Toward a New Way of Reading the Zhou Yi

The text of Shi hexagram examined above is generally representative of the Shanghai Museum manuscript and of its relationship with the received text of the Zhou Yi. Nevertheless, before coming to the conclusion that the manuscript offers nothing new in terms of how to read and understand the Zhou Yi, especially in its earliest contexts, it would be well to consider a few other portions of the manuscript as well. For instance, the very first strip in the manuscript (actually composed of three separate fragments, 16.7 cm, 12.4 cm, and 9.6 cm long, with another section about 5 cm long at the top of the strip missing) carries the text that corresponds to the top four line statements of Meng 蒙 hexagram, the third hexagram in the received text. Let us once again place the manuscript text above the received text, in gray.

As one can see at a glance, the manuscript contains a character for every one of the thirty-six characters in the received text, of which twenty are either identical or essentially so. There are also eleven variants: 晶 : 三, 又 : 有, 躳 : 躬, 亡 : 无, 卣 : 攸,  : 利 (three times), 尨 : 蒙 (three times), 僮 : 童,

: 利 (three times), 尨 : 蒙 (three times), 僮 : 童,  : 擊,

: 擊,  : 寇 (two times), and 御: 禦. Of these, 晶 as opposed to san 三, “three,” 又 as opposed to you 有, “to have,” and 亡 as opposed to wu 无, “not to have,” have already been seen above in the case of Shi hexagram. 躳 : 躬, 卣 : 攸,

: 寇 (two times), and 御: 禦. Of these, 晶 as opposed to san 三, “three,” 又 as opposed to you 有, “to have,” and 亡 as opposed to wu 无, “not to have,” have already been seen above in the case of Shi hexagram. 躳 : 躬, 卣 : 攸,  : 利, 僮 : 童, and

: 利, 僮 : 童, and  : 寇 are simple graphic variants, essentially different ways of spelling the same words: gong, “body, person”; you, a preverbal nominalizing particle; li, “benefit”; tong, “youth”; and kou, “bandit,” respectively.46 The variants

: 寇 are simple graphic variants, essentially different ways of spelling the same words: gong, “body, person”; you, a preverbal nominalizing particle; li, “benefit”; tong, “youth”; and kou, “bandit,” respectively.46 The variants  as opposed to ji 擊 and 御 as opposed to yu 禦 may well also be simple graphic variants, in both cases the character of the received text having an additional classifier or signific, specifying the meaning of the characters (thus, ji, “to hit,” and yu, “to drive off, to resist,” respectively). However, in these cases, it would also be possible to imagine other meanings for the manuscript. Thus, 御 can be understood perfectly well without any additional signific, writing the word yu, “to drive, to control,” while

as opposed to ji 擊 and 御 as opposed to yu 禦 may well also be simple graphic variants, in both cases the character of the received text having an additional classifier or signific, specifying the meaning of the characters (thus, ji, “to hit,” and yu, “to drive off, to resist,” respectively). However, in these cases, it would also be possible to imagine other meanings for the manuscript. Thus, 御 can be understood perfectly well without any additional signific, writing the word yu, “to drive, to control,” while  might also be expanded to xi 繫, “to tie” (i.e., adding a “silk” signific, 糹). Nevertheless, these sorts of variation are of the same order as seen in the case of Shi hexagram and probably would not cause us to reconsider how to read the received text of this hexagram. However, the final variation, that between 尨 and 蒙, is of a different nature. In conventional script, 尨 is the standard graph for the word mang, “long-haired dog,” whereas 蒙 is used to write a series of words pronounced meng: “type of plant, dodder”; “lush, luxuriant”; “to cover”; “to wear on the head”; “to trick”; “occluded”; “ignorant”; “confused”; “youth.” In the Zhou Yi tradition, the character, which is also the name of this hexagram,47 is variously explained as “youth” or “ignorance,” with many commentators combining the two meanings (i.e., “the ignorance of youth” or “Youthful Folly”).48 What could a “long-haired dog” have to do with “the ignorance of youth”?

might also be expanded to xi 繫, “to tie” (i.e., adding a “silk” signific, 糹). Nevertheless, these sorts of variation are of the same order as seen in the case of Shi hexagram and probably would not cause us to reconsider how to read the received text of this hexagram. However, the final variation, that between 尨 and 蒙, is of a different nature. In conventional script, 尨 is the standard graph for the word mang, “long-haired dog,” whereas 蒙 is used to write a series of words pronounced meng: “type of plant, dodder”; “lush, luxuriant”; “to cover”; “to wear on the head”; “to trick”; “occluded”; “ignorant”; “confused”; “youth.” In the Zhou Yi tradition, the character, which is also the name of this hexagram,47 is variously explained as “youth” or “ignorance,” with many commentators combining the two meanings (i.e., “the ignorance of youth” or “Youthful Folly”).48 What could a “long-haired dog” have to do with “the ignorance of youth”?

Pu Maozuo notes that the Jingdian shiwen 經典釋文 of Lu Deming 陸德明 (556–627) indicates meng 蒙 as an alternative pronunciation of 尨49 and thus assumes that both 尨 and 蒙 stand for the same word, which he regards as meng, “youth, ignorance.” There is no question that mang 尨 and meng 蒙 were sufficiently similar in pronunciation that 尨 could be used to write meng 蒙,50 no different from writing “red” for “read” in “she read the book.”51 If so, despite this variation in the character, the manuscript should be understood as writing the same word as the received text. Nevertheless, despite the long-standing tradition that in this hexagram of the Zhou Yi that word should be meng, “youth, ignorance, Youthful Folly,” it stands to reason that the opposite could also be true; that is, 蒙 might also be used to write mang 尨. In fact, this is an argument that has been made recently by Ōno Yūji 大野裕司.52 He notes that in line statements of this hexagram such as kun mang/meng 困尨/蒙 and ji mang/meng 擊尨/蒙, “long-haired dog” makes better sense as an object of the verbs kun 困, “to latch, to bind,” and ji 擊, “to hit,” than does “the ignorance of youth.” Even in the Six in the Fifth line statement, tong mang/meng 僮尨/蒙, tong 僮, “young, youth,” could describe a long-haired puppy just as well as a child, ignorant or otherwise. Examining the other line statements in the received text of this hexagram, which, however, have not survived in the manuscript, the case for reading meng 蒙 as “the ignorance of youth” becomes even more strained. The First Six and the Nine in the Second lines read as follows:

發蒙利用刑人用說桎梏以往吝

Lifting [literally, “shooting”] the meng. Beneficial herewith to punish a man, and herewith to remove the fetters in order to go. Distress.

包蒙吉納婦吉子克家

Wrapping the meng. Auspicious. Taking a wife: auspicious; a son can marry.

Later commentators have naturally read the fa 發, literally, “to shoot, to propel,” of the first line in its extended sense of “to develop” and thus interpret the image as an injunction in favor of education (“develop the ignorant youth”).53 Although this makes good sense in a Confucian context, does it make sense in the context of the rest of the line statement, with its injunctions regarding punishment? Another variation in the early textual history of the Zhou Yi with respect to the second of these line statements might well bring us back to reading mang or meng as a hairy dog: instead of bao meng 包蒙, “to wrap the meng,” the Jingdian shiwen quotes the text of Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 (127–200) as reading biao meng 彪蒙, the original meaning of biao 彪 being “stripes (of a tiger).”54 Although this line is missing from the Shanghai Museum manuscript, if it too were to read biao mang 彪尨, might we then read it as “a striped long-haired dog”?