Chapter 3

Centrifugal Pumps

All types of centrifugal pumps depend on centrifugal force for their operation. Centrifugal force acts on a body moving in a circular path, tending to force it farther away from the axis or center point of the circle described by the path of the rotating body.

Basic Principles

The rotating member inside the casing of a centrifugal pump provides rapid rotary motion to the mass of water contained in the casing. That means the water is forced out of the housing through the discharge outlet by means of centrifugal force. The vacuum created thereby enables atmospheric pressure to force more water into the casing through the inlet opening. This process continues as long as motion is provided to the rotor, and as long as a supply of water is available. In the centrifugal pump, vanes or impellers rotating inside a close-fitting housing draw the liquid into the pump through a central inlet opening, and by means of centrifugal force the liquid is thrown outward through a discharge outlet at the periphery of the housing.

Figure 3-1 and

Figure 3-2 show the basic principle of centrifugal pump operation. If a cylindrical can with vanes

A and

C (for rotating the liquid when the can is rotated) is mounted on a shaft with a pulley for rotating the can at high speed, centrifugal force acts on the water (rotating at high speed) to press the water outward to the walls of the can. This causes the water to press outward sharply. Since it cannot move beyond the walls of the can, pressure forces the water upward, causing it to overflow as the water near the center of the can is drawn downward. Atmospheric pressure forces the water downward, since a vacuum is created near the center as the water moves outward toward the sides of the can. It can be noted in

Figure 3-1 that the water has been lifted a distance

DD′.

Since the water that spills over the top has a high velocity that is equal to the rim speed, the kinetic energy that has been generated is wasted, unless an arrangement is made to catch the water and an additional supply of water is provided (see

Figure 3-2). In

Figure 3-2, a receiver catches the water as it spills over, and a supply tank is connected with the hollow shaft to supply water to the can. Instead of rotating the can, only the vanes can be rotated to obtain the same result.

Figure 3-1 Basic principle of a centrifugal pump. The radial vanes A and C cause the liquid to revolve when the cylinder is rotated (left). Centrifugal force pushes the liquid outward toward the walls of the cylinder and then upward, causing it to overflow when the cylinder is rotated at high speed (right).

Pumps Having Straight Vanes

In the first practical centrifugal pump, the rotor was built with straight (radial) vanes (see

Figure 3-3). The essential parts of a centrifugal pump are:

• Impeller, or rotating member.

• Case, or housing surrounding the rotating member.

In the centrifugal pump, water enters through the inlet opening in the center of the impeller, where it is set in rotation by the revolving blades of the impeller. The rotation of the water, in turn, generates centrifugal force, resulting in a pressure at the outer diameter of the impeller; when flow takes place, the water passes outward from the impeller at high velocity and pressure into the gradually expanding passageway of the housing and through the discharge connection to the point where it is used.

Pump Having Curved Vanes

Curved vanes were first used by Appold in England in 1849.

Figure 3-4 shows the cover and inner workings of a centrifugal pump having curved vanes and casing (commonly known as a

volute pump). An inlet pipe connection (

A) to the cover directs the water to the eye (

B) of the rotating impeller. The curved vanes (

C) of the impeller direct the water from the eye to the discharge edge (

D), moving the water in a spiral path. As the impeller revolves, the water moves toward the discharge edge, and then enters the volute-shaped passageway (

E) where it is collected from around the impeller and directed to the discharge connection (

F).

Figure 3-2 A basic centrifugal pump with supply tank and receiver.

The Volute

A volute is a curve that winds around and constantly recedes from a center point. The volute is a spiral that lies in a single plane (in contrast with a conical spiral). It is the shape of the periphery of the case or housing that surrounds the impeller of a volute-type centrifugal pump.

The volute-type casings or housings form a progressively expanding passageway into which the impeller discharges the water. The volute-shaped passageway collects the water from the impeller and directs it to the discharge outlet.

Figure 3-3 A centrifugal pump showing the principle involving centrifugal force.

Figure 3-4 Basic parts of a centrifugal pump showing cover (left) and section of a centrifugal pump, commonly termed a volute pump because of the shape of its housing.

The volute-shaped housing is proportioned to produce equal flow velocity around the circumference, and to reduce gradually the velocity of the liquid as it flows from the impeller to the discharge outlet. The objective of this arrangement is to change velocity head to pressure head.

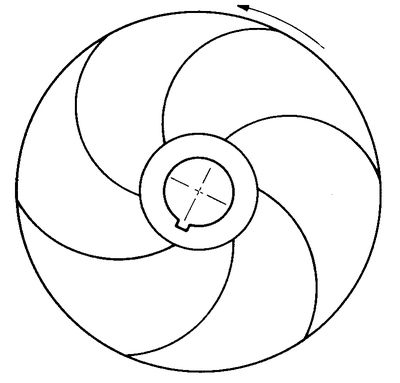

Curvature of the Impeller Vanes

If the vanes could be curved to a shape that is mathematically correct, a different curve would be required for each change in working conditions. However, this is not practical because a large number of patterns in stock would be required.

Figure 3-5 shows a simple method for describing the curve of the vanes for impellers of the larger diameters and for lifts of 60 feet or more as follows:

• Divide the circle into a number of arms (six, for example).

• Bisect each radius.

• Using the point

B as a center point and a radius

BC, describe the curves that represent the working faces of the vanes:

Figure 3-5 Layout for the curved vanes of an impeller.

Basic Classification

The centrifugal pump is a device for moving liquids and gases. The two major parts of the device are the impeller (a wheel with vanes) and the circular pump casing around it. The volute centrifugal pump is the most common type. In it, the fluid enters the pump at high speed near the center of the rotating impeller. Here it is thrown against the casing by the vanes. The centrifugal pressure forces the fluid through an opening in the casing. This outlet widens progressively in a spiral that reduces the speed of the fluid and increases the pressure. Centrifugal pumps produce a continuous flow of fluid at high pressure. The pressure can be increased by linking several impellers together in one system. In such a multistage pump, the outlet for each impeller casing serves as the inlet to the next impeller. Centrifugal pumps are used for a wide variety of purposes, such as pumping liquids for water supply, irrigation, and sewage disposal systems. Such devices are also utilized as gas compressors.

The basic designs of centrifugal pumps correspond to the various principles of operations. Centrifugal pumps are designed chiefly with respect to the following:

• Intake, as single-admission or double-admission.

• Stage operation, as single-stage or multistage.

• Output, as large-volume (low-head), medium-volume (medium-head), and small-volume (high-head).

• Impeller, as type of vanes, number of blades, housing, and so on.

Single-Stage Pump

This type of pump is adapted to installations that pump against low to moderate heads. The head generated by a single impeller is a function of its tangential speed. It is possible and, in some instances, practical to generate as much as 1000 feet of head with a single-stage impeller, but for heads that exceed 250 to 300 feet, multistage pumps are generally used. Single-admission pumps are made in one or more stages, and the double-admission pumps may be either single-stage or multistage (see

Figure 3-6).

The chief disadvantage of the single-admission pump is that the head at which it can pump effectively is limited. The double-admission single-stage pump is adapted to the elevation of large quantities of water to moderate heights. Another advantage of the double-admission type of pump is that the impeller is balanced hydraulically in an axial direction, because the thrust from one admission stream is counteracted by the thrust from the other admission stream.

Single-stage centrifugal pumps are widely used in portable pumping applications as well as in stationary pumping applications. These portable pumps can be operated by air motors, electric motors, gasoline engines, and diesel engines. Many are used in the contracting field. Stationary single-stage centrifugal pumps are very popular in home use in both shallow and deep wells for supplying the home water supply.

Figure 3-6 Single-admission (left) and double-admission (right) types of impeller for single-stage centrifugal pumps, illustrating flow path of the liquid.

Multistage Pump

The multistage centrifugal pump is essentially a high-head or high-pressure pump. It consists of two or more stages. The number of stages depends on the size of head against which the pump is to work. Each stage is essentially a separate pump. However, these stages are located in the same housing and the impellers are attached to the same shaft. Up to eight stages may be found in a single housing.

The initial or first stage receives the water directly from the source through the admission pipe, builds the pressure up to the correct single-stage pressure, and passes it onward to the succeeding stage. In each succeeding stage, the pressure is increased or built up until the water is delivered from the final stage at the pressure and volume that the pump is designed to deliver.

Figure 3-7 shows water flow in single-admission and double-admission multistage pumps.

Stationary-mounted centrifugal pumps are found on many machine tools for delivering coolant to the cutting tools. Multiple-stage centrifugal pumps are used in home and industry where large volumes of water at high pressure are required.

Figure 3-7 Flow path of liquid from admission to discharge for single-admission (upper) and double-admission (lower) types of impellers in multistage pumps.

Impellers

The efficiency of a centrifugal pump is determined by the type of impeller. The vanes and other details are designed to meet a given set of operating conditions. The number of vanes may vary from one to eight, or more, depending on the type of service, size, and so on.

Figure 3-8 shows a single-vane

semi-open impeller. This type of vane is adapted to special types of industrial pumping problems that require a rugged pump for handling liquids containing fibrous materials and some solids, sediment, or other foreign materials in suspension.

The open type of vane is suited for liquids that contain no foreign matter or material that may lodge between the impeller and the stationary side plates. Liquids containing some solids (such as those found in sewage or drainage, where there is a limited quantity of sand or grit) may be handled by the open type of vane.

In addition to the open and semi-open types of impellers, the

enclosed or shrouded type of impeller may be used (see

Figure 3-9), depending on the service, desired efficiency, and cost. The enclosed type of impeller is designed for various types of applications. The shape and the number of vanes are governed by the conditions of service. It is more efficient, but its initial cost is also higher. Shrouded impellers do not require wearing plates. The enclosed impeller reduces wear to a minimum, ensures full-capacity operation with initially high efficiency for a prolonged period of time, and does not clog, because it does not depend on close operating clearances.

The

axial-flow type of impeller (see

Figure 3-10) is used to obtain a flow of liquid in the direction of the axis of rotation. These propeller-type impellers are designed to handle a large quantity of water at no lift and at low head in services such as irrigation, excavation, drainage, sewage, etc. The pumping element must be submerged at all times. This type of pump is not suitable for pumping that involves a lift.

The

mixed-flow type of impeller (see

Figure 3-11) is used to handle a large quantity of water at low head. High-capacity low-head pumps are designed on the mixed-flow principle to increase the rotational speeds, reduce the size and bulk of the pump, and to increase efficiency.

Figure 3-9 Several types of impellers: (a) open, (b) semi-open, and (c) enclosed.

Figure 3-10 Propeller-type impeller used to obtain axial flow.

Balancing

The centrifugal pump is inherently an unbalanced machine. These pumps are subject to end thrust, which means that some method must be devised to counteract this load. In a single-admission type of impeller, an unbalanced hydraulic thrust is directed axially toward the admission side, because the vacuum in the admission side causes atmospheric pressure to produce a thrust on the impeller. Various methods of balancing have been tried:

• Natural balancing, as by opposing impellers.

• Mechanical balancing, as by a balancing disk, and so on.

Natural Balancing

This method of balancing is generally used in double-admission, single-stage pumps and in single- and double-admission multistage pumps.

Figure 3-12 shows back-to-back single-admission impellers and a double-admission impeller. In the diagrams, the two thrusts

P and

P′ act in axial directions and oppose each other.

Figure 3-12 Natural balancing achieved in single-stage pumps by means of two back-to-back single-admission types of impellers (left) and one double-admission type of impeller (right).

The opposing-impellers method is applied to multistage pumps by various impeller arrangements. The three-stage pump arrangement (see

Figure 3-13) consists of a central double-admission impeller and two opposing single-admission end impellers. The arrows indicate the opposing thrusts.

Figure 3-13 Natural balancing achieved in a three-stage pump by means of two opposed single-admission types of impellers (left and right) and one double-admission type of impeller (center).

Opposing-impellers balancing in the five-stage pump (see

Figure 3-14) consist of a central double-admission impeller for the first stage and two pairs of opposing back-to-back impellers for the second and third stages and for the fourth and fifth stages. The method is also illustrated in the six-stage pump shown in

Figure 3-15.

Figure 3-14 Natural balancing in a five-stage pump by means of an assembly by two pairs of opposed single-admission back-to-back type impellers (left and right) and one double-admission type of impeller (center).

Figure 3-15 Natural balancing achieved in a six-stage centrifugal pump by means of an assembly of four single-admission type impellers (left and right) and one double-admission type of impeller (center).

Mechanical Balancing

The liquid enters through the eye of the impeller in an axial direction and leaves in a radial direction, thereby creating an end thrust that also results from the fact that the liquid in the clearance spaces is under pressure. These forces are not present in open impellers, since there are no shrouds upon which the forces act.

In a single-admission enclosed-impeller pump (see

Figure 3-16), the liquid from the housing, being under pressure, leaks backward through the clearance spaces

A and

D, past the sealing rings

C and

B, to the inlet. The impeller is usually cored in the rear shroud to permit the accumulating leakage to pass onward to the inlet without building up a pressure there. Therefore, forces on the two shrouds are equal to the pressure acting on the shroud areas.

Figure 3-16 Mechanical balancing in a centrifugal pump by means of a balancing disk.

Since there is a difference in pressure intensity (highest at the rim of the impeller, lowest at the sealing rings) the pressure is variable. The pressure at the holes cored through the rear shroud is not quite the same as that in the inlet chamber. Therefore, the forces on the two shrouds are different. The resultant force is usually greater in clearance space D than in space A, so the resultant force is toward the inlet end of the pump.

Since normal operating wear increases the clearances in the sealing rings, the forces are changed and their proportions are changed, the end-thrust increasing with wear. To balance this wear as nearly as possible, engineers have changed the diameter at which the sealing ring

B (see

Figure 3-16) is placed, increasing the diameter to reduce the area on which the high-pressure liquid acts. Thus, if this ring were moved outward to the rim of the impeller, the force on the rear shroud could be reduced to change the resultant end thrust to the opposite direction or away from the admission.

To provide the pump with a minimum of end thrust during its useful life, the ring is placed outward at a distance far enough to reverse the thrust while the pump is new and while the clearances in the sealing rings are small. Clearances increase with use. Thrust is reduced gradually. It finally reverses itself near the admission end. The proportions are so fixed that, by the time the thrust becomes large enough to cause an undue load on the thrust bearing on the shaft, leakage through the increased clearance spaces is sufficient to affect seriously the efficiency of the pump. Then the clearance rings can be replaced at a small cost to restore the pump to its original condition.

As previously explained, the thrust tendency is toward the admission side of the pump. The objective of the balancing disk method is to balance this thrust by providing a countering pressure in the opposite direction, which is maintained automatically in proper proportions against the balancing disk.

In

Figure 3-16, the balancing disk (

C) is keyed to the shaft behind the last-stage impeller and runs with a small clearance between it and the balance seat (

B). While in operation, the pump creates a pressure in space

A that is slightly lower than the discharge pressure of the pump. This pressure acts against the balancing disk (

C), to counterbalance the end thrust that is in the opposite direction. Since the pressure against the disk

C is greater than that of the end thrust, the complete rotating element of the pump, together with disk

C, is caused to move slightly, so that disk

C is moved away from seat

B.

This action results in a small leakage into the balance chamber (D), thereby reducing the pressure in space A, which causes the rotating element to return to a position where leakage past disk C and seat B enables the pressure in space A to balance the thrust—thrust and balance pressure are in equilibrium. The leakage between disk C and seat B is slight and not large enough to affect the efficiency or capacity of the pump for a considerable period.

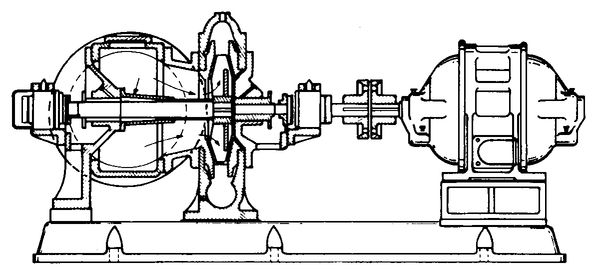

Construction of Pumps

In its primitive form, the centrifugal pump was inefficient and was intended only for pumping large quantities of water at low heads. This type of pump is now highly developed, and many types of these pumps are available for a wide variety of service requirements.

Although the earlier pumps were adapted only to low heads, this has been overcome by connecting two or more units on a single shaft and operating them in series—passing the water through each unit in succession, with the total head pumped against divided between the units (multistage pump).

The earlier multistage assemblies were bulky, because they consisted of separate units coupled. However, several stages are now housed in a single casing or housing. The centrifugal pump usually gives best results when it is designed for specific operating conditions.

Casing or Housing

The casing is usually a two-piece casting split on a horizontal or diagonal plane, with inlet and discharge openings cast integrally with the lower portion. Centrifugal pumps are either single-inlet or double-inlet types. The double-inlet type of pump is usually preferred, because the end thrusts are equalized when variations in pressure occur on either the discharge or the inlet side.

The diagonally split casing or housing (see

Figure 3-17) permits easy removal of internal parts. The discharge and suction piping need not be disturbed.

Figure 3-18 shows the offset-volute design of casing. This type of casing also features top-centerline discharge. It also has self-venting and back pullout.

Impeller

Impeller design varies widely to meet a wide variety of service conditions. The selection of the proper type of impeller is of prime importance in obtaining satisfactory and economical pump operation.

Figure 3-17 View of a paper-stock centrifugal pump. The diagonallysplit casing permits easy removal of the interior parts without disturbing the discharge of the suction piping.

(Courtesy Buffalo Forge Company)

Figure 3-18 An offset-volute design of casing (left) and cover (right). The casing is designed for top centerline discharge, self-venting, and back pullout.

(Courtesy Buffalo Forge Company)

A high degree of efficiency can be obtained with the open-type impeller under certain conditions by carefully proportioning the curvature of the blades and by reducing the side clearances to a minimum with accurate machining of impeller edges and side plates. The open-type impeller is often used to handle large quantities of water at low heads, such as those encountered in irrigation, drainage, storage of water, and circulation of water through condensers.

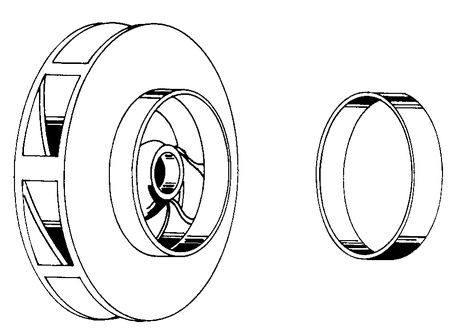

The enclosed-type impeller (see

Figure 3-19) is generally considered to be a more efficient impeller. The vanes are cast integrally on both sides and are designed to prevent packing of fibrous materials between stationary covers and the rotating impeller.

Figure 3-19 Open-type (left) and enclosed-type (right) impellers.

(Courtesy Buffalo Forge Company)

Figure 3-20 shows an enclosed-type double-inlet impeller and wearing ring. The impeller is cast in a single piece of bronze, although some liquids require that the impeller be made of chrome, Monel, nickel, or a suitable alloy.

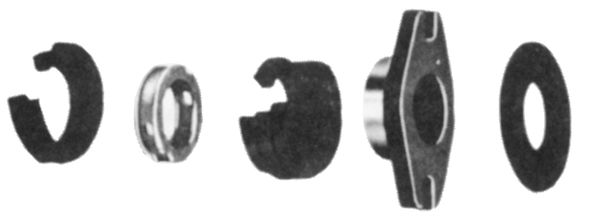

Stuffing-Box Assembly

The assembly shown in

Figure 3-21 is equipped with a five-ring packing and seal cage. The seal cage is split and glass-filled with material that is resistant to corrosion and heat. Mechanical seals can be used, and they are available in materials suitable for corrosive and non-corrosive applications.

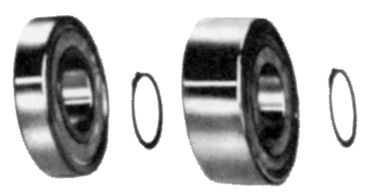

Bearings and Housings

Most pumps are equipped with ball bearings (see

Figure 3-22). Typical construction consists of single-rows of deep-grooved ball bearing of ample size to withstand axial and radial loads. The bearing housing may be of the rotating type, so that the entire rotating element can be removed from the pump without disturbing the alignment or exposing the bearings to water or dirt. The bearing housing may be positioned by means of dowel pins in the lower portion of the casing and securely clamped by covers split on the same plane as the pump casing. Then the entire bearing can be removed from the shaft without damage by using the sleeve nut as a puller. However, single ball bearings are an exception. Most pumps today are provided with double ball bearings.

Figure 3-20 Enclosed-type double-inlet impeller and wearing ring. Some liquids require that the impeller be made of special metals, such as chrome, Monel, nickel, or a suitable alloy.

(Courtesy Buffalo Forge Company)

Figure 3-21 Stuffing-box assembly for a centrifugal pump.

(Courtesy Buffalo Forge Company)

Figure 3-22 Bearings for a centrifugal pump. The outboard thrust bearing is a double-row deep-grooved ball bearing, and the inboard guide bearing is a single-row deep-grooved ball bearing.

(Courtesy Buffalo Forge Company)

Shaft Assembly

The shaft (see

Figure 3-23) is machined accurately to provide a precision fit for all parts, including the impeller and bearings. The shaft in most centrifugal pumps must be protected against corrosive or abrasive action by the liquid pumped, by such methods as using cast bronze sleeves that fit against the impeller hub and are sealed by a thin gasket.

Figure 3-23 A solid one-piece stainless-steel shaft for a centrifugal pump. The shaft is machined accurately to provide a precision fit for all parts.

(Courtesy Buffalo Forge Company)

Drive

Centrifugal pumps are driven by direct drive or by a belt and pulley. A large subbase is usually provided for direct-drive connection to an engine or motor, and the two units are connected by a suitable coupling (see

Figure 3-24). A disassembly of a dredging pump with a base or pedestal for belt-and-pulley drive is shown in

Figure 3-25.

Vertical pumps are generally made with a single inlet. Since the weight of the impeller and shaft requires a thrust bearing, this weight can be proportioned to take care of the unbalanced pressure caused by the single-inlet characteristic.

Figure 3-26 shows a vertical motor-mount dry-pit centrifugal pump. Gearing for vertical pumps is seldom advisable, except where bevel gears may be needed to transmit power from a horizontal shaft to a vertical shaft.

Figure 3-27 shows a diagram with dimensions of a horizontal angle-flow centrifugal pump. Prior to introduction of the angle-gear drive, most deep-well turbine engines were driven by electric motors. However, this development has resulted in the use of more gasoline and diesel power units.

Figure 3-24 Centrifugal pump and motor placed on a large subbase and connected by a suitable coupling for direct-drive.

(Courtesy Buffalo Forge Company)

Figure 3-25 Disassembly view showing parts of a belt-drive single-stage centrifugal pump. The parts shown are: (A) shaft; (B) shaft collar; (C) hub gland; (D) hub [lower half]; (E) hub [upper half]; (F) hub, brass; (G) hub, brass shim; (H) hub, brass adjusting screw; (I) bearing stand; (J) pillow block; (K) pillow-block cap; (L) pulley; (M) pump shell; (N) impeller; (O) pump disk; and (P) bedplate.

(Courtesy Buffalo Forge Company)

Figure 3-26 A vertical motor-mount centrifugal pump.

(Courtesy Deming Division, Crane Co.)

Installation

When the correct type of centrifugal pump has been selected for the service requirements, it must be installed properly to give satisfactory service and to be reasonably trouble-free. Several important factors must be considered for proper pump installation, depending on the size of the pump.

Location

The pump should be located where it is accessible and where there is adequate light for inspection of the packing and bearings. A centrifugal pump requires a relatively small degree of attention, but if it is inaccessible, it probably receives no attention until a breakdown requiring major repairs occurs.

Figure 3-27 Horizontal angle-type of centrifugal pump with tabulated dimension.

The height of lift must also be considered. The lift is affected by temperature, height above sea level, and pipe friction, foot valve, and strainer losses. The elevation of the pump with respect to the liquid to be pumped should be at a height that is within the practical limit of the dynamic lift.

Piping also affects the location of the pump. The pump should be located so that the piping layout is as simple as possible.

Foundation

The foundation should be rugged enough to afford a permanent rigid support to the entire base area of the bedplate and to absorb normal strains and shocks that may be encountered in service. Concrete foundations are usually the most satisfactory.

Foundation bolts of the specified size should be located in the concrete according to drawings submitted prior to shipment of the unit. If the unit is mounted on steelwork or other type of structure, it should (if possible) be placed directly above the main members, beams, and walls, and it should be supported in such a way that the base plate cannot be distorted or the alignment disturbed by a yielding or springing action of the structure or the base plate. The bottom portion of the bedplate should be located approximately ¾ inch above the top of the foundation to leave space for grouting.

Leveling

Pumps are usually shipped already mounted, and it is usually unnecessary to remove either the pump or the driving unit from the base plate for leveling. The unit should be placed above the foundation and supported by short strips of steel plate and wedges near the foundation bolts. A ¾-inch to 2-inch space between the base plate and the foundation should be allowed for grouting. The coupling bolts should be removed before proceeding with leveling the unit and aligning the coupling halves.

When scraped clean, the projecting edges of the pads supporting the pump and motor feet can be used for leveling, employing a spirit level. If possible, the level should be placed on an exposed part of the pump shaft, sleeve, or planed surface of the casing.

The wedges underneath the base plate can be adjusted until the pump shaft is level, and the flanges of the suction and discharge nozzles are either vertical or horizontal, as required. At the same time, the pump should be placed at the specified height and location. Accurate alignment of the unbolted coupling halves between the pump and the driver shafts must be maintained while proceeding with the leveling of the pump and base.

To check the alignment of the pump and driver shafts, place a straightedge across the top and side of the coupling, checking the faces of the coupling halves for parallelism by means of a tapered thickness gage or feeler gage at the same time (see

Figure 3-28).

Figure 3-28 Use of a straightedge and feeler gage to align the pump and driver shafts.

If the coupling halves are true circles, have the same diameter, and have flat faces, true alignment exists when the distances between the faces are equal at all points and when a straightedge lies squarely across the rim at all points. The test for parallelism is to place a straightedge across the top and side of the coupling, checking the faces of the coupling halves for parallelism by means of a tapered thickness gage or feeler gage at the same time.

Turbine Drive

If the pump is driven by a steam turbine, final alignment should be made with the driver at operating temperature. If this is impossible, an allowance in the height of the turbine and shaft while cold should be made. In addition, if the pump is to handle hot liquids, allowance should be made for elevation of the shaft when the pump expands. In any event, the alignment should be checked while the unit is at operating temperature and adjusted as required, before placing the pump in actual service. The application of heat to the steam and exhaust piping results in expansion. The turbine nozzles should not be subjected to piping strains in the installation.

Motor Drive

An allowance for heat is unnecessary for electric motors. The motor alone should be operated (if possible) before aligning the pump, so that the magnetic center of the rotor can be determined. If this is impossible, the rotor of the motor should be turned over and reversed to determine collar clearances, and then placed in the middle position for aligning. If the faces are not parallel, the thickness gage (or feelers) varies at different points. If one coupling is higher than the other, the distance can be determined by means of the straightedge and feeler gages.

Space between Coupling Faces

The clearance between the faces of the couplings of the pin-andbuffer type, and the ends of the shafts in other types of couplings, should be set so that they cannot touch, rub, or exert a force on either the pump or the driver. The amount of clearance may vary with the size and type of coupling used. Sufficient clearance for the unhampered endwise movement of the shaft of the driving element to the limit of its bearing clearance should be allowed. On motor-driven units, the magnetic center of the motor determines the running position of the half-coupling of the motor. This can be checked by operating the motor while it is disconnected.

Grouting

The grouting process involves pouring a mixture of cement, sand, and water into the voids of the stone, brick, or concrete work, either to provide a solid bearing or to fasten anchor bolts, dowels, and so on. The usual grouting mixture consists of one part cement, two parts sand, and enough water to cause the mixture to flow freely underneath the bedplate.

A wooden form is built around the outside of the bedplate to contain the grout and to provide sufficient head for ensuring a flow of the mixture beneath the entire head plate. The grout should be allowed to set for 48 hours. Then the hold-down bolts should be tightened and the coupling halves rechecked.

Inlet Piping

In a new installation, it is advisable to flush the inlet pipe with clear water before connecting it to the pump. Except for misalignment, most problems with individual centrifugal pump installations can be traced to faults in the inlet lines. It is extremely important to install the inlet piping correctly.

The diameter of the inlet piping should not be smaller than the inlet opening, and it should be as short and direct as possible. If a long inlet cannot be avoided, the size of the piping should be increased. Air pockets and high spots in an inlet line invariably cause trouble. Preferably, there should be a continual rise (without high spots) from the source of supply to the pump.

When the supply liquid is at its lowest level, the end of the pipe should be submerged to a depth equal to four times its diameter (for large pipes). Smaller pipes should be submerged to a depth of 2 to 3 feet. After installation is completed, the inlet piping should be blanked off and tested hydrostatically for air leaks before the pump is operated.

A strainer should be attached to the end of the inlet pipe to prevent lodging of foreign material in the impellers. The clear and free opening of the strainer should be equal to three or four times the area of the inlet pipe. If the strainer is likely to become clogged frequently, the inlet pipe should be placed where it is accessible. A foot valve for convenience in priming may be necessary where the pump is subjected to intermittent service. The size and type of foot valve should be selected carefully to avoid friction loss through the valve.

Discharge Piping

The discharge piping (like the inlet piping) should also be as short and as free of elbows as possible, to reduce friction. Check valves and gate valves should be placed near the pump. The check valve protects the casing of the pump from breakage caused by water hammer, and it prevents the pump operating in reverse if the driver should fail. The gate valve can be used to shut off the pump from the discharge piping when inspection or repair is necessary.

Pumps Handling High-Temperature Liquids

Special types of multistage pumps are constructed for handling high-temperature liquids, with a key and keyway on the feet and base of the lower half of the casing. One end of the pump is bolted securely, but the other end (on some units) is bolted with spring washers positioned underneath the nuts on the casing feet, permitting one end of the casing to move laterally as the casing expands. Some special types of hot-liquid multistage pumps are doweled at the inboard end, and other types are doweled at the thrust-bearing end, sometimes with the dowels placed crosswise. Dowels at the opposite end (if used) are fitted parallel to the pump shaft, to allow the casing to expand at high temperatures.

When handling hot liquids, the nozzle flanges should be disconnected after the unit has been placed in service, to determine whether the expansion is in the proper direction.

Jacket Piping

Multistage pumps use jacketed or separately-cooled thrust bearings. If hot liquids are being handled, care must be taken to be certain that the jacket or oil-cooler water piping is connected.

Drain Piping

To determine whether the water is flowing and to regulate the amount of flow, it is good practice to pipe the discharge from the jacket or cooler into a funnel connected to a drain. All drain and drip connections should be piped to a point where leakage can be disposed of.

Operation

Before starting the operation of a centrifugal pump, the driver should be tested for its direction of rotation (see

Figure 3-29), with the coupling halves disconnected. The arrow on the pump casing indicates the direction of rotation.

Figure 3-29 The direction of rotation of the impeller on a centrifugal pump.

The ball bearings should be supplied with the grade of lubricant recommended by the pump manufacturer. Oil-lubricated bearings should be filled level with the overflow.

The cooling water piping to the thrust-bearing housing also requires attention. Cooling water should not be used on bearings that are warm to the hand only. Use only sufficient water to keep the lubricant at a safe working temperature.

Periodically, the water supply should be flushed freely to remove particles of scale and similar particles that may stop the flow on a throttled valve. Final inspection of all parts should be made carefully before starting the pump. It should be possible to rotate the rotor by hand.

Priming

A centrifugal pump should not be operated until it is filled with water. If the pump is run without liquid, there is danger of damage to liquid-lubricated internal parts. Some specially-constructed types of centrifugal pumps have been designed to start dry. Liquid from an external source is used to seal the stuffing boxes and to lubricate the impeller wearing rings and shaft sleeves in the same manner as with a stuffing-box packing.

Ejector Method

As shown in

Figure 3-30, the pump is equipped with a discharge valve and a steam ejector. To prime, the discharge valve is closed after the steam-inlet valve has been opened; then the valve between the ejector and the pump is opened, the air in the pump and pipes is exhausted, and the water is drawn into them. Complete priming is indicated by water issuing from the ejector.

Figure 3-30 Three methods of priming centrifugal pumps: (a) ejector; (b) lift-type pump; and (c) foot valve with top discharge.

The ejector is shut off by first closing the valve between the ejector and the pump, and then closing the steam-inlet valve. If it is inconvenient to place the ejector near the pump, the air pipe can be extended, using an air pipe that is slightly larger than when the ejector is placed near the pump.

Hand-Type Lift Pump (or Powered Air Pump) Method

A check valve can be used instead of the discharge valve, and either a hand-type old-fashioned lift pump (see

Figure 3-30) or a powered air pump can be substituted for the steam ejector. A valve should be placed in the air pipe. The valve should be closed before starting. In the older installations, the kitchen-type lift pumps were often used for priming. Sometimes the kitchen-type pumps themselves require a small quantity of water to water-seal them, making them an effective air pump.

Foot-Valve and Top-Discharge Method

When the foot valve is used (see

Figure 3-30), the centrifugal pump and inlet pipe are filled with water through the discharge or top portion of the pump from either a small tank or a hand-type pump. If the inlet pipe is long, at least 5 feet of discharge head on the pump is required to prevent water from being thrown out before the water in the inlet line has begun to move, causing failure in starting. When check or discharge valves are used, a vacuum gage placed on the airpriming pump at the head of the well or pit indicates that the pump is primed. A steam-type air ejector may be operated with water if 30 to 40 pounds of water pressure is available. However, a special type of ejector is required.

For automatic priming, a pressure regulator can be connected into the discharge line. The regulator automatically starts an air pump if the main pump loses its prime. It stops the priming pump when the priming action is completed.

In the float-controlled automatic priming system (see

Figure 3-31), a priming valve is connected between the top of the casing of the pump and a float-controlled air valve. The air valve is connected to a priming switch, with the contacts in series with the control circuit of the main motor starter. A check valve in the discharge line operates a switch that shunts the priming switch.

In actual operation, the priming valve and air valve are in the indicated positions so long as the pump is not primed. When the float switch closes, the priming pump is started. It continues in operation until the main pump is primed and until the water is high enough in the float chamber to close the priming switch. The closing of the priming switch starts the main pump, and the priming pump is stopped by a contact that is opened when the pump motor control circuit is energized. When the main pump is running, the discharge check valve is held open, and the contacts on its switch are closed to complete a holding circuit for the pump motor contactor around the priming switch. This switch permits the priming switch to open, without shutting down the pump.

A number of small holes in the priming valve plunger permit air to pass freely during the priming operation. These small holes are so proportioned that the pressure developed by the pump forces the plunger to its seat, thereby cutting off communication to the priming pump when priming has been completed and the pump has started. When the priming line is sealed, the water drains from the float chamber, and the priming switch opens. However, the pump motor contactor is held closed by a circuit through the discharge-valve switch. When the float switch opens, the main pump shuts down. It should be noted that the float switch starts the priming pump when it closes, and it stops the centrifugal pump when it opens.

Figure 3-32 shows another type of automatic priming system in which a vacuum tank is used as a reserve to keep the main pump primed. This system consists of a motor-driven air pump and a vacuum tank connected between the section of the air pump and the priming connections on the centrifugal pump. The air tank serves as a reserve on the system, so that the vacuum producer needs starting only intermittently. A vacuum switch starts and stops the vacuum producer at the predetermined limits of vacuum. An air trap in the line between the pump to be primed and the vacuum tank prevents water rising into the vacuum system after the pump is primed. Air is drawn from the pump suction chamber whether the pump is idle, under vacuum, or in operation. The priming pipes and air-trap valves are under vacuum to ensure that the centrifugal pump remains primed at all times. Modifications of this type of system are used for pumps that handle sewage, paper stock, sludge, or other fluids that carry solids in suspension.

Figure 3-33 shows other diagrams of piping for priming.

Figure 3-32 Automatic priming system in which a vacuum tank is used as a reserve to keep the main pump primed.

Starting the Pump

Prior to starting a pump having oil-lubricated bearings, the rotor should be turned several times, either by hand or by momentarily operating the starting switch (with the pump filled with water), if the procedure does not overload the motor. This starts a flow of oil to the bearing surfaces. The pump can be operated for a few minutes with the discharge valve closed without overheating or damage to the pump.

Various items should be checked before starting the pump. On some installations, an extended trial run is necessary. The vent valves should be kept open to relieve pocketed air in the pump and system during these trials. This circulation of water prevents overheating the pump.

Figure 3-33 Piping for priming systems using independent priming water supply (left) and priming by extraction of air (right).

Then, to cut the pump into the lines, close the vent valves and open the discharge valve slowly. The pump is started with the discharge valve closed, because the pump operates at only 35 to 50 percent of full load when the discharge valve is closed. If the liquid on the upper side of the discharge check valve is under sufficient head, the pump can be started with the discharge valve in open position.

Gland packing should not be too tight, because heat may cause it to expand, thereby burning out the packing and scoring the shaft. A slight leakage is desirable at first; then the packing can be tightened after it has been warmed and worn. A slight leakage also indicates that the water seal is effective without undue binding, keeping the gland and shaft cool.

A specific type of packing is required for high temperatures and for some liquids (see

Figure 3-34). Graphite-type packing is recommended for either hot or cold water. Rapid wear of the sleeves may result if flax packing or metallic packing is used on centrifugal pumps with bronze shaft sleeves. Each ring of packing should be inserted separately and pushed into the stuffing box as far as the gland permits. The split openings of the successive packing rings should be positioned at 90-degree intervals.

As mentioned, the centrifugal pump should not be operated for long periods at low capacity because of the possibility of overheating. However, a pump may be operated safely at low capacity if a permanent bypass from the discharge to the inlet (equal to one-fifth the size of the discharge pipe) is installed.

To start a hot-condensate pump, open the inlet and discharge valves on the independent stuffing-box seals before operating. Usually, the air-extraction apparatus is in service before the hot-condensate pump is started, and the main turbine is heated at the same time. This provides an accumulation of water in the hot well. If allowed to collect above the level of the hot-condensate gage glass, the steam jets or other extracting apparatus do not entrain water, which renders them inoperative. As soon as a supply of condensate begins flowing to the hot well, the pump can be started and the air valves on top of the pump opened as the pump reaches full speed. Then the air valves should be closed.

Except for the bearings and the glands, a centrifugal pump does not require attention once it is operating properly. These pumps should operate for long periods without attention other than to observe that there is a drip of liquid from the glands, that the proper oil is supplied to the bearings, and that the oil is changed at regular intervals.

Stopping the Pump

Normally, when there is a check valve near the pump in the discharge line, the pump is shut down by stopping the motor, securing it until needed again by closing the valves in the following order:

1. Discharge

2. Inlet

3. Cooling water supply

4. At all points connecting to the system

Usually, when the pump is stopped in this manner, the discharge gate valve need not be opened. However, in some installations, surges in the piping may impose heavy shocks on both the lines and the pump when the flow of water under high pressure is arrested. Then it is good practice to first close the discharge gate valve, to eliminate shock.

If a pump remains idle for some time after it is stopped, it gradually loses priming, because the liquid drains through the glands. If it is necessary to keep the pump primed for emergency use, this should be kept in mind when the pump is stopped. It is not necessary to close the inlet and discharge valves, because the glands may leak because of sustained pressure on a stationary shaft. The gland nuts should not be tightened unless preparation is made to loosen them again when starting the pump.

Abnormal Operating Conditions

Centrifugal pumps should run smoothly and without vibration when they are operating properly. The bearings operate at a constant temperature, which may be affected by the location of the units. This temperature may range as low as 100°F, but the operating temperature is usually maximum temperature at minimum flow, varying with pump capacity.

If, for some reason, a pump either does not contain liquid or becomes vapor-bound, vibration will occur because of contact between the stationary and the rotating parts, and the pump may become overheated. Vapor may be blown from the glands and, in extreme instances, the thrust bearings may suddenly increase in temperature; damage may result from the rotor being forced in a single direction.

If the pump is overheated because of a vaporized condition and the rotor has not seized, open all vents and prime or flood liquid into the pump. A low-temperature liquid should not be admitted suddenly to a heated pump, because fracture or distortion of its parts may result. An overheated pump should not be used unless an emergency exists (to save a boiler from damage, for example).

Vibration also may result from excessive wear on the pump rotor or in the shaft bearings, which causes the pump and motor shafts to become misaligned. These should be corrected at the first opportunity. If a rotor has seized, it is necessary to dismantle it completely and to rectify the parts by filing, machining, and so on.

Troubleshooting

Many difficulties may be experienced with centrifugal pumps. Location of these troubles and their causes are discussed here.

Reduced Capacity or Pressure and Failure to Deliver Water

When the capacity or pressure of the pump is reduced and the pump fails to deliver water, any of the following may be the cause:

• Pump is not primed

• Low speed

• Total dynamic head is higher than the pump rating

• Lift is too high (normal lift is 15 feet)

• Foreign material is lodged in the impeller

• Opposite direction of rotation

• Excessive air in water

• Air leakage in inlet pipe or stuffing boxes

• Insufficient inlet pressure for vapor pressure of the liquid

• Mechanical defects (such as worn rings, damaged impeller, or defective casing gasket)

• Foot valve is either too small or restricted by trash

• Foot valve or inlet pipe is too shallow

Loses Water after Starting

If the pump starts and then loses water, the cause may be any the following:

• Air leak in inlet pipe

• Lift too high (over 15 feet)

• Plugged water-seal pipe

• Excessive air or gases in water

Pump Overloads Driver

If the driver is overloaded by the pump, the cause may be any of the following:

• Speed too high

• Total dynamic head lower than pump rating (pumping too much water)

• Specific gravity and viscosity of pumped liquid different from pump rating

• Mechanical defects

Pump Vibrates

The causes of pump vibration may be the following:

• Misalignment

• Foundation not rigid enough

• Foreign material causes impeller imbalance

• Mechanical defects, such as bent shaft, rotating element rubbing against a stationary element, or worn bearings

Centrifugal pumps can be operated only in one direction. The arrow on the casing indicates the direction of rotation. During pump operation, the stuffing boxes and bearings should be inspected occasionally. The pump should be disassembled, cleaned, and oiled if it is to be idle for a long period. If the pump is to be exposed to freezing temperatures, it should be drained immediately after stopping.

Pointers on Pump Operation

Various abnormal conditions may occur during pump operations. Following are some suggestions:

• If the pump discharges a small quantity of water during the first few revolutions and then churns and fails to discharge more water, air is probably still in the pump and piping, or the lift may be too great. Check for a leaky pipe, a long inlet pipe, or lack of sufficient head.

• If the pump produces a full stream of water at first and then fails, the cause is failure of the water supply, or the water level receding below the lift limit. This can be determined by placing a vacuum gage on the inlet elbow of the pump. This problem can be remedied by lowering the pump to reduce the lift.

• If the pump delivers a full stream of water at the surface or pump level, but fails at a higher discharge point, then the pump speed is too low.

• If the pump delivers a full stream of water at first and the discharge decreases slowly until no water is delivered, an air leak at the packing gland is the cause.

• If a full stream of water is delivered for a few hours and then fails, then the inlet pipe or the impeller is obstructed if the flow from the water supply is unchanged.

• If heavy vibration occurs while the pump is in operation, then the shaft has been sprung, the pump is out of alignment, or an obstruction has lodged in one side of the impeller.

• If the bearings become hot, then the belt is unnecessarily tight, the bearings lack oil, or there is an end thrust.

• If hot liquids are to be pumped, the lift should be as small as possible, because the boiling point of the liquid is lowered under vacuum and the consequent loss of priming is caused by the presence of vapor.

• If the water is discharged into a sump or tank near the end of the inlet pipe, there is great danger of entraining air into the inlet pipe.

• If a pump is speeded up to increase capacity beyond its maximum rating, a waste of power results.

• If a pump remains idle for some time, its rotor should be rotated by hand once each week. For long periods, it should be taken apart, cleaned, and oiled.

Maintenance and Repair

Liberal clearances are provided between the rotating and the stationary pump parts to allow for small machining variations, and for the expansion of the casing and rotor when they become heated. Stationary diaphragms, wearing rings, return channels, and so on (which are located in the casing or other stationary parts) are slightly smaller in diameter than the bore of the casing, which is machined with a

-inch gasket between the flanges. When the flange nuts are tightened, the casing must not bind on the stationary parts. Operating clearances (such as those at the wearing rings) depend on the actual location of the part, the type of the material, and the span of the bearing.

Lateral End Clearances

Lateral movement between the rotor and stator parts is necessary for mechanical and hydraulic considerations, and for expansion variations between the casing and the rotor. End movement is limited to

inch in small pumps and certain other types of pumps, and it may be as much as ½ inch on larger units and on those handling hot liquids. On pumps handling cold liquids, the clearance is divided equally when the thrust bearing is secured in position and the impellers are centralized. The recommendations of the pump manufacturer should be consulted for the designed lateral clearances before proceeding with an important field assembly.

Parts Renewals

Since the pump casings are made from castings, it is sometimes necessary to favor variations in longitudinal dimensions on the casings by making assembly-floor adjustments to the rotor, so that designed lateral clearances can be preserved and so that the impellers can be placed in their correct positions with respect to the diaphragms, diffusers, and return channels.

When a rotor with its diffusers is returned to the factory for repair, the repaired rotor can be placed in the pump with no adjustment if it is still possible to calibrate dimensions on the worn parts. When it is impossible to obtain complete details on the used parts, replacement parts are made to standard dimensions.

When the assembled rotor (with stage pieces, and so on) is placed in the lower portion of the casing, the total lateral clearance should be checked. With the thrust bearing assembled and the shaft in position, the total clearance should be divided properly and the impellers centered in their volutes. Final adjustments are made by manipulation of the shaft nuts.

The casing flange gaskets should be replaced with the same type and thickness of material as the original gaskets. The inner edge of the gasket must be trimmed accurately along the bore of the stuffing box. The edges must be trimmed squarely and neatly at all points. This is especially so where the gasket abuts on the outer diameter and sides of the stationary parts between the stages. It should be overlapping sufficiently for the upper portion of the casing to press the edges of the gasket against the stator parts while the casing is being tightened. This ensures proper sealing between the stages. In the trimming-operation, the gasket should first be cemented to the lower portion of the casing with shellac. Then a razor blade can be used to cut the gasket edges squarely, overlapping at the same time.

Pointers on Assembly

Unnecessary force should not be used in tightening the impeller and shaft sleeve nuts. Bending of the shaft may result, and the concentricity of the rotor parts operating in close clearances with the stator parts may be destroyed, causing rubbing and vibration.

Locking Screws

A dial test indicator should be used to determine whether the shaft has been bent when securing the safety-type locking screws.

Design considerations require that all parts be mounted on the shaft in their original order. Opposed impellers are both right-hand and left-hand types in the same casing. Diaphragms, wearing rings, and stage bushings are individually fitted, and their sealing flanges between the stages are checked for each location. Stage bushings with stop pieces are not interchangeable with each other, because the stop pieces may locate at various positions. All stationary parts assembled on the rotor (such as stuffing-box bushings, diaphragms, and so on) possess stops that consist of either individual pins or flange halves in the lower casing only, to prevent turning. These parts must be in position when lowering the rotor into the casing, so that all stops are in their respective recesses in the lower casing. Otherwise, the upper casing may foul improperly-positioned parts during the mounting procedure.

Deep-Well Pump Adjustments

Before operating these pumps, the impeller or impellers must be adjusted to their correct operating positions by either raising or lowering the shaft by means of the adjuster nut provided for the purpose. The shaft is raised to its uppermost position by turning the adjusting nut downward. Measure the distance the shaft has been raised above its lowest position, and then back off the adjusting nut until the shaft has been lowered one-third the total distance that it was raised. Lock the nut in position with the key, setscrew, or locknut provided. With either a key or a setscrew, it is usually necessary to turn the adjusting nut until it is possible to insert the key or setscrew in place through both the adjusting nut and motor clutch.

Installing Increaser on Discharge Line

Hydraulic losses can be reduced by installing an increaser on the discharge line.

Figure 3-35 shows the hookup with the check and discharge valves. The discharge line should be selected with reference to friction losses, and it should never be smaller than the pump discharge outlet—preferably, one to two sizes larger. The pump should not be used to support heavy inlet or discharge piping. Pipes or fittings should not be forced into position with the flange bolts, because the pump alignment may be disturbed. Independent supports should be provided for all piping. When piping is subjected to temperature changes, expansion and contraction should not exert a strain on the pump casing. In hotels, apartment buildings, hospitals, and so on, where noise is objectionable, the discharge pipe should not be attached directly to the steel structural work, hollow walls, and so on, because vibration may be transmitted to the building. Preferably, the discharge line should be connected to the pump discharge outlet through a flexible connection.

Figure 3-35 Installation of a diffuser or increaser on the discharge line.

Corrosion-Resisting Centrifugal Pumps

Centrifugal pumps are designed for liquid transfer, recirculation, and other applications where no suction lift is required. These pumps produce high flow rates under moderate head conditions. However, centrifugal pumps are not recommended for pumping viscous fluids.

Table 3-1 is a viscosity chart for liquids up to 1500 Saybolt-seconds universal (ssu).

Saybolt-seconds universal (

ssu) is the time required for a gravity flow of 60 cubic centimeters. Performance decrease and horsepower adjustment are shown in the table.

These pumps are not self-priming and should be placed at or below the level of the liquid being pumped (see

Figure 3-36).

Typical Application—Plating

A typical plating-shop installation serves to show how the corrosion-resisting centrifugal pump is utilized in industry (see

Figure 3-37). There are a number of applications for this type of pump in the plating shop. The pumps are manufactured in two materials:

Figure 3-36 Connecting the pump for proper operation.

(Courtesy Sherwood)

Figure 3-37 shows a pump mounted on the end of an electric motor. The plastic pump is combined with a nonmetallic seal that offers compatibility with a wide variety of corrosive chemicals used in the plating industry.

Figure 3-37 Corrosion-resisting centrifugal pump.

(Courtesy Sherwood)

Plating

A typical plating line consists of a series of baths and rinses, each requiring circulation, transfer, and filtering pumps.

Figure 3-38 shows a single plating line, whereas most installations involve multiple lines.

Shaft Seal

Noncorrosive thermoplastic mechanical stationary shaft seals isolate all metal parts from liquid contact (see

Figure 3-39). Stainless steel components are sealed in polypropylene. The seal guarantees reliability through simplicity and balance of design.

Water Treatment

The waste-treatment system neutralizes spent plating solutions and waste acids throughout the total system.

Figure 3-38 Using the corrosion-resisting centrifugal pump in a plating plant (illisible)

Figure 3-39 Corrosion-resisting centrifugal pump seal.

(Courtesy Sherwood)

Fume Scrubbers

The actual plating process emits malodorous and noxious fumes. Removal of the most difficult fumes and odors is done by using air scrubbers. Pumps are used as circulation units in the removal of contaminant particles from fumes emitted in the process environments.

Corrosion-Resisting Pump Installation

Locate the pump as near the source to be pumped as possible. A flooded suction situation is preferred. Since this type of pump is not self-priming,

it must never be allowed to run dry. If the fluid level is below the pump, therefore, a foot valve must be installed and the pump primed prior to start-up (see

Figure 3-40).

Mount the motor base to a secure, immobile foundation. Use only plastic fittings on both the intake and discharge ports, and seal the pipe connections with Teflon tape. These fittings should be self-supported and in a neutral alignment with each port. That is, fittings must not be forced into alignment that may cause premature line failure or damage to the pump volute.

Figure 3-40 Electrical hook-up for a centrifugal pump.

(Courtesy Sherwood)

Never choke the intake. Keep both the input and discharge lines as free of elbows and valves as possible. Always use pipe of adequate diameter. This will reduce friction losses and maximize output.

All electrical wiring should meet state and local ordinances. Improper wiring may not only be a safety hazard, but may permanently damage the motor and/or pump.

Ensure that the supply voltages match the pump motor’s requirements. Check the motor wiring and connect (according to instructions on the motor) to match the supply voltage. Be sure of proper rotation. Improper rotation will severely damage the pump and void the warranty.

The power cord should be protected by conduit or by cable, and should be of the proper gage or wire size. It should be no longer than necessary. Power should be drawn directly from a box with circuit breaker protection or with a fused disconnect switch.

Always switch off the power before repairing or servicing the pump or the motor. Check for proper rotation of three-phase (3Φ) motors.

The water flush will provide decontamination of chemicals or elastomers and seal and seat faces, while providing lubrication required for start-up. Water-flushed seals are recommended for abrasive solutions, high temperature service, or when pumps may be run dry or against dead head conditions. Where conditions cause the pumped liquid to form crystals, or if the pump remains idle for a period without adequate flushing, a water flush seal system is advised.

Two methods of water flushing can be used:

• Direct Plumbing to City Water—This provides the best possible approach to flushing the seal and seat faces. Caution must be taken to conform to local city ordinances that may require backflow preventers. These are a series of check valves required to prevent contamination of city water should there be a shutoff of the water supply. Also be aware of the addition of water into the chemicals pumped where some imbalance may be created altering the chemicals’ formulation and aggressiveness.

•

Recirculation of Solution Pumped—This system takes a bleed off the pump discharge and recirculates the solution in the seal chamber. Although not nearly as effective as the direct water flush, it will provide cooling to the seal and seat faces under operation. This system is not effective where crystallization occurs or for pumps in idle conditions.

Figures 3-41 and

3-42 show the pump intake and discharge and plug locations.

Figure 3-41 Pedestal model pump, cutaway view.

(Courtesy Sherwood)

Maintenance

Lubricate the motor as per instructions on the motor. The rotary seal requires no lubrication after assembly. The pump must be drained before servicing, or if stored in below-freezing temperatures. Periodic replacement of seals may be required due to normal carbon wear.

Figure 3-42 (a) Pedestal model pump with cutaway view, and (b) Endmount model pump with cutaway view.

(Courtesy Sherwood)

Corrosion-Resisting Pump Troubleshooting

Table 3-2 shows symptoms and actions when troubleshooting corrosion-resisting pumps.

Pump-End Assembly and Disassembly

In some instances, it may become necessary to disassemble the pump (for example, for inspection).

Figure 3-43 shows an exploded view of the pump to facilitate the disassembly and reassembly if necessary.

Pump Disassembly

To disassemble the pump, follow these steps:

1. Shut off power to motor before disconnecting any electrical wiring from the back of the motor.

2. Disassemble the body-motor assembly from the volute. The volute may be left in-line if you wish.

3. Remove the cap covering the shaft at the back of the motor and with a large screwdriver, prevent the shaft from rotating while you unscrew the impeller.

4. Remove the ceramic piece from the impeller.

Table 3-2 Troubleshooting Corrosion-Resisting Pumps

| Symptom | Action |

|---|

| Motor will not rotate | Check for proper electrical connections to the motor |

| Check main power box for blown fuse, etc. |

| Check thermal overload on the motor |

| Motor hums or will not rotate at correct speed | Check for proper electrical connections to the motor and the proper cord size and length |

| Check for foreign material inside the pump |

| Remove the bracket and check for impeller rotation without excessive resistance |

| Remove the pump and check the shaft rotation for excessive bearing noise |

| Have an authorized service person check the start switch and/or start capacitor on the motor |

| Pump operates with little or no flow | Check to insure that the pump is primed |

| Check for a leaking seal |

| Check for improper line voltage to the motor or incorrect rotation |

| Check for clogged inlet port and/or impeller |

| Check for defective check valve or foot valve |

| Check inlet lines for leakage, of either fluid or air |

| Pump loses prime | Check for defective check valve or foot valve |

| Check for leaking seal |

| Check for inlet line air leakage |

| Check for low fluid supply |

| Motor or pump overheats | Check for proper line voltage and phase, also proper motor wiring |

| Check for binding motor shaft or pump parts |

| Check for inadequate ventilation |

| Check temperature of fluid being pumped—should not exceed 194°F (90°C) for extended periods |

Figure 3-43 Exploded view of corrosion-resisting centrifugal pump.

(Courtesy Sherwood)

5. Detach the body from the motor.

6. Remove the carbon-graphite seal from the body by pressing out from the back. Do not dig out from the front.

Pump-End Assembly

To assemble the pump-end assembly, follow these steps:

1. Clean and inspect all pump parts: O-ring, seal seats, motor shaft, and so on.

2. Apply lubricant to the body bore hole and O-ring for seal installation.

3. Press the carbon graphite seal into the body while taking care not to damage the carbon graphite face.

4. Place the slinger (rubber washer) over the motor shaft and mount the body to the motor.

5. Carefully grease the boot or O-ring around the ceramic piece and press it into the impeller. If the ceramic piece has an O-ring, the marked side goes in.

6. Sparingly lubricate carbon-graphite and ceramic sealing surfaces with lightweight machine oil. Do not use silicon lubricants or grease.

7. Thread the impeller onto the shaft and tighten. If required, remove the motor end-cap and use a screwdriver on the back of the motor shaft to prevent shaft rotation while tightening. Replace the motor end-cap.

8. Electrically, connect the motor so that the impeller will rotate counterclockwise (CCW) facing the pump with the motor toward the rear. Incorrect rotation will damage the pump and void the warranty.

Note

For three-phase power, electrically check the rotation of the impeller with the volute disassembled from the bracket. If the pump-end is assembled and the rotation is incorrect, serious damage to the pump-end assembly will occur and invalidate the warranty. If the rotation is incorrect, simply exchange any two leads to reverse the direction of rotation.

9. Seat the O-ring in the volute slot and assemble the volute to the body.

10. Install the drain plug in the volute drain hole.

Good Safety Practices

Following are some good safety tips:

• When wiring a motor, follow all local electrical and safety codes, as well as the National Electrical Code (NEC) and the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA).

• Always disconnect the power source before performing any work on or near the motor or its connected load. If the power disconnect point is out of sight, lock the disconnect in the open position and tag it to prevent unexpected application of power. Failure to do so could result in electrical shock.

• Be careful when touching the exterior of an operating motor. It may be hot enough to be painful or cause injury. With modern motors, which are built to operate at higher temperatures, this condition is normal if operated at rated load and voltage.

• Do not insert any object into the motor.

• Pump rotates in one direction only—counterclockwise from the pump inlet end.

• Protect the power cable from coming in contact with sharp objects.

• Do not kink the power cable and never allow the cable to contact oil, grease, hot surfaces, or chemicals.

• Ensure that the power source conforms to the requirements of your equipment.

• Do not handle the pump with wet hands or when standing in water because electrical shock could occur. Disconnect the main power before handling the unit for any reason.

• The unit should run counterclockwise as viewed facing the shaft end. Clockwise rotation can result in damage to the pump motor, property damage, and/or personal injury.

Impeller Design Considerations

Experience has been an important factor in determining the design of centrifugal impellers. Fundamentally, the centrifugal pump adds energy in the form of velocity to an already-flowing liquid; pressure is not added in the usual sense of the word. Kinetic energy is involved in all basic considerations of the centrifugal pump.

The design of the impeller of a centrifugal pump is based ultimately on the performance of other impellers. The general effect of altering certain dimensions is a result of modifying or changing the design of impellers that have been tested.

Calculations applicable to centrifugal pumps are based on the impeller diagram shown in

Figure 3-44, in which the following symbols are used:

V2 is tangential velocity at outer periphery

V1 is tangential velocity at inner periphery

Figure 3-44 Impeller illustrating basis of calculations.

Z2 is relative velocity of water at outlet

Z1 is relative velocity of water at inlet

C2 is absolute velocity of water at outlet

J 2 is radial velocity of water at outlet

J 1 is radial velocity of water at inlet

W is tangential velocity of water at outlet

d2 is outlet angle of impeller

d1 is inlet angle of impeller

Velocity of Impeller

In the

Figure 3-44, water enters the impeller inlet with a radial velocity

J1, and it leaves the impeller at an absolute velocity

C2. The inner peripheral velocity

V1 and the outer peripheral velocity

V2 are in

feet per second. If the theoretical head

H (in feet) represents the head against which the pump delivers water (with no losses), then:

in which the following is true:

g is the force of gravity = 32.2 feet per second

If the head H against which the pump must work and the diameter of the impeller are known, the speed of the pump can be calculated by the preceding formulas.

Problem

If a pump with an impeller diameter of 10¾ inches is required to pump against a head of 100 feet, what is the required speed of the pump?

Solution

By substituting in the previous formula:

Since the tangential velocity V2 at the outer periphery of the impeller is 80.25 feet per second, this is equal to 4815 feet per minute (80.25 × 60). Since the circumference (πd) of a 10¾-inch diameter impeller is 33.8 inches (3.14 × 10¾, or 2.8 feet, the impeller must rotate at a speed of 4815 feet per minute; this is equal to 1720 revolutions per minute (4815 ÷ 2.8).

Total Hydraulic Load or Lift

As mentioned, the lift is the vertical distance measured from the level of the water to be pumped to the centerline of the pump inlet. If the water level is above the centerline of the pump, the pump is operating under inlet head, or negative lift. Under conditions of negative lift, the inlet head must be subtracted from the sum of the remaining factors.

The discharge head, in contrast to the inlet head, is the vertical distance measured between the centerline of the pump discharge opening and the level to which the water is elevated.

The loss of head because of friction must be considered. This loss can be obtained from

Table 3-3. Other data for centrifugal pump calculations are given in

Tables 3-4,

3-5,

3-6,

3-7, and

3-8.

Velocity Head

The equivalent distance (in feet) through which a liquid must fall to acquire the same velocity is called

velocity head. The velocity head can be determined from the following formula:

in which

Where D equals the diameter of the pipe in inches.

The following example is used to illustrate calculation of the total hydraulic head that a pump may work against, using gage readings.

Problem

Assuming that the distance

A (see

Figure 3-45) or vertical distance from the centerline of the gage connection in the inlet pipe to the centerline of the pressure gage is 2 feet. The discharge pressure gage reading is 40 pounds. The vacuum gage reading is 15 inches (when discharging 1000 gallons of water per minute). The discharge pipe is 6 inches in diameter (at gage connection) and the inlet pipe is 8 inches in diameter (at gage connection). Calculate the total hydraulic load or lift.

Table 3-3 Loss of Head Because of Friction in Pipes †

Table 3-4 Electric Current Consumption for Pumping

| Percent Efficiency of Pump, Motor, and Transformer | Consumption in Kilowatt-Hours per 24-hour Period (100 gallons/minute; 100 feet high) |

|---|

| 30 | 149.2 |

| 34 | 132.0 |

| 38 | 118.0 |

| 42 | 107.0 |

| 45 | 100.0 |

| 50 | 89.0 |

| 55 | 81.0 |

| 60 | 75.0 |

| 65 | 69.0 |

| 70 | 64.0 |

| 75 | 59.0 |

Table 3-5 Weight and Volume of Water (Standard Gallons)

| Imperial, or English | U.S. |

|---|

| Cubic inches/gallon | 277.274 | 231.00 |

| Pounds/gallon | 10.00 | 8.3311 |

| Gallons/cubic foot | 6.232102 | 7.470519 |

| Pounds/cubic foot | 62.4245 | 62.4245 |

Solution

40 (psi) × 2

.31 feet = 92

.40 feet

15-inch vacuum (

Table 3-7) = 17.01 feet

Distance (see

Figure 3-37) = 2.00 feet

Velocity head in 6-inch pipe minus velocity

Head in 8-inch pipe, or (1

.99 − 0

.63) = 1

.36 feet

Total hydraulic load or lift = 112.77 feet

(2.31 feet = height of water column exerting 1 psi)

Table 3-6 Gallons of Water Per Minute Required to Feed Boilers (30 pounds, or 3.6 gallons, of water per horsepower, evaporated from 100° to 70 pounds per square inch of steam pressure)