Chapter 14

Fluid Lines and Fittings

The efficiency of a fluid power system is often limited by the lines (fluid carriers) that carry the fluid operating medium from one fluid power component to another. The purpose of these carriers is to provide leakproof passages at whatever operating pressure may be required in a system. A poorly planned system of fluid carriers for the system often results in component malfunctions caused by the following:

• Restrictions (creates a backpressure in the components)

• Loss of speeds (reduces efficiency)

• Broken carriers, especially in high-pressure systems (creates fire hazards and other problems)

Selection of the proper carrier is as important as the proper selection of the fluid components.

Fluid may be directed through either lines or manifolds. Fluid lines or piping fall into three categories:

• Rigid

• Semi-rigid, or tubing

• Flexible, or hose

In many instances, all three categories are employed in a single fluid system. The pressures involved and the fluid medium used will determine the type of carrier and the connectors and fittings.

Rigid Pipe

Steel pipe is the original type of carrier used in fluid power systems, and it is available in the following four different weights:

• Standard (STD), or Schedule 40—This pipe (seamless) is designed for test pressures of 700 psi in the 1/8-inch size to 1100 psi in the 2-inch size.

• Extra Strong (XS), or Schedule 80—This weight of pipe is used in the medium pressure range of hydraulic systems. This pipe (seamless) is designed for test pressures of 850 psi for 1/8-inch size to 1600 psi in the 2-inch size (Grade B).

• Schedule 160—This pipe is designed for test pressures up to 2500 psi.

• Double Extra Heavy (XXS)—This pipe is also used for test pressures up to 2500 psi, even though the wall thickness is somewhat heavier.

Sizes of pipe are listed by the nominal inside diameter (ID), which is actually a misnomer. The sizes are nearly equivalent to Schedule 40, but there is a difference. For example, the ID of a ¼-inch Schedule 40 pipe is 0.364 inch, and the ID of a ½-inch Schedule 40 pipe is 0.622 inch.

As the schedule number of the pipe increases, the wall thickness also increases. This means that the ID of the pipe for each nominal size is smaller, but the outside diameter (OD) of the pipe for each nominal size remains constant (see

Table 14-1).

Some of the fittings that are used with steel pipe are tees, crosses, elbows, unions, street elbows, and so on. The pipe fittings are listed in nominal pipe sizes.

Steel pipe is one of the least-expensive fluid carriers for hydraulic fluid as far as material costs are concerned, but installation costs often consume considerable time in comparison to installation costs of other types of fluid carriers. Pipe is suited for handling large fluid volumes and for running long lines of fluid carriers. Pipe is commonly used on suction lines to pumps and for short connections between two components. It is also useful on piping assemblies that are seldom disassembled. Pipe provides rigidity for holding various components in position, such as valves that are designed for in-line mounting with no other method of support. Pipe should be cleaned thoroughly before it is installed in a fluid power system.

Semi-Rigid (Tubing)

Two types of steel tubing are utilized in hydraulic systems, as recommended by the United States of America Standards Institute (USASI) hydraulic standards. These types of tubing are

seamless and

electric-welded . Tubing sizes are measured on the OD of the tubing. Seamless steel tubing is manufactured from highly ductile, dead-soft, annealed low-carbon steel, and an elongation in 2 inches of 35 percent minimum. In tubes with an OD of 3/8 inch and/or a wall thickness of 0.035 inch, a minimum elongation of 30 percent is permitted. The diameter of the tubing does not vary from that specified by more than the limits shown in

Table 14-2.

The process used for making steel tubing is the cold drawing of pierced or hot-extruded billets.

Table 14-3 shows the nominal sizes of seamless steel tubing that are readily available for hydraulic systems.

| OD, Nominal, | OD (inches) | ID (inches) |

|---|

| ¼ to ½ inch, incl. | ± 0.003 | — |

| Above ½ to 1½ inch, incl. | ± 0.005 | ± 0.005 |

| Above 1½ to 3½ inch, incl. | ± 0.010 | ± 0.010 |

Manufacturing Process

Electric-welded steel tubing is manufactured by shaping a cold-rolled strip of steel into a tube and then performing a welding and drawing operation. The chemical and physical properties of electric-welded steel tubing are similar to those of seamless steel tubing.

To use steel tubing (or any other type of tubing) in a fluid power system, it is necessary to attach some type of fitting to each end of the tubing. Numerous methods are employed to accomplish this. However, in the final analysis, the fitting holds the tubing securely, providing a leakproof assembly that can withstand the pressures for which it was designed. In some instances, the fitting is welded to the tubing. In other applications (air systems), friction between the tubing and the fitting is sufficient to hold the pressure.

Figure 14-1 shows an assembly in which a sleeve is brazed to the tubing, and the nut is then screwed onto the fitting.

Figure 14-2 shows a sleeve that digs into the tubing wall when the nut is tightened on the fitting.

Figure 14-3 shows some of the fittings that are most commonly used (such as tees, elbows, crosses, and straights).

Figure 14-1 An assembly in which a sleeve is brazed to the tubing, and the nut is then screwed onto the fitting.

(Courtesy Imperial-Eastman Corporation)

Figure 14-2 A fitting for high-pressure tubing in which the sleeve of the fitting grips the tubing.

(Courtesy Imperial-Eastman Corporation)

Figure 14-3 Tubing fittings used in fluid-power systems.

(Courtesy Imperial-Eastman Corporation)

Other Types

Following are other types of tubing employed in fluid power systems:

• Copper tubing—This type of tubing is often found on air circuits that are not subject to USASI standards. Because of the work hardening when flared, and since it is an oil-oxidation catalyst, USASI standards restrict the use of copper tubing for hydraulic service. Copper tubing can be worked easily to make bends that reduce fitting requirements.

• Aluminum tubing—Seamless aluminum tubing is approved for low-pressure systems. This tubing has fine flaring and bending characteristics.

• Plastic tubing—Plastic tubing for fluid power lines is made from several basic materials. Among these materials are nylon, polyvinyl, polyethylene, and polypropylene.

• Nylon tubing—This tubing is used on fluid power applications in the low-pressure range, up to 250 psi. It is suitable for a temperature range of minus 100°F to plus 225°F. This tubing possesses good impact and abrasion resistance. It can be stored without deteriorating or becoming brittle, and it is not affected by hydraulic fluids. One of the newer developments is the self-storing type of nylon tubing that looks like a coil spring; it is very popular for use on pneumatic tools.

• Polyvinyl chloride tubing—For air lines with pressures up to 125 psi, this type of tubing may be used. Temperatures should not exceed 100°F continuously. It may be used intermittently for temperatures up to 160°F.

• Polyethylene tubing—This is ideal tubing for pneumatic service, and it is also used for other fluids at low pressures. It possesses great dimensional stability and resists most chemicals and solvents. Polyethylene tubing is manufactured in several different colors that lend it readily to colorcoding. Tubing sizes are usually available up to and including ½-inch OD.

• Polypropylene tubing—This type of tubing is suitable for operating conditions with temperatures of minus 20°F to plus 280°F, and it can be sterilized repeatedly with steam. It possesses surface hardness and elasticity that provide good abrasion resistance. It is usually available in sizes up to and including ½-inch OD, in natural or black colors.

Installation of Tubing

Following are some precautions that should be observed when installing tubing (see

Figure 14-4):

• Avoid straight-line connections wherever possible, especially in short runs.

Figure 14-4 Correct method (a) and incorrect method (b) of installing tubing in a system.

(Courtesy of Weatherhead Co.)

• Design the piping systems symmetrically. They are easier to install and present a neater appearance.

• Care should be taken to eliminate stress from the tubing lines. Long tubing should be supported by brackets or clips. All parts installed on tubing lines (such as heavy fittings, valves, and so on), should be bolted down to eliminate tubing fatigue.

• Before installing tubing, inspect the tube to ensure that it conforms to the required specifications, that it is of the correct diameter, and that the wall thickness is not out of round.

• Cut the ends of tubes reasonably square. Ream the inside of the tube and remove the burrs from the outside edge. Excessive chamfer on the outside edge destroys the bearing of the end of the tube on the seat of the fitting.

• To avoid difficulty in assembly and disconnection, a sufficient straight length of tube must be allowed from the end of the tube to the start of the bend. Allow twice the length of the nut as a minimum.

• Tubes should be formed to assemble with true alignment to the centerline of the fittings, without distortion or tension. A tube that has to be sprung (position

A in

Figure 14-4) to be inserted into the fitting has not been properly fabricated, and when so installed and connected, places the tubing under stress.

• When assembling the tubing, insert the longer leg to the fitting as at

C (see

Figure 14-4), and then insert the other end into fitting

D. Do not screw the nut into the fitting at

C. This holds the tubing tightly, and restricts any movement during the assembly operation. With the nut free, the short leg of the tubing can be moved easily, brought to position properly, and inserted into the seat in the fitting

D. The nuts can then be tightened as required.

Flexible Piping (Hose)

Hose is employed in a fluid power system in which the movement of one component of the system is related to another component. An example of this utilization is a pivot-mounted cylinder that moves through an arc while the valve to that the cylinder is connected with fluid lines remains in a stationary position. Hose may be used in either a pneumatic or a hydraulic system.

Many different types of hose are used in fluid power systems, and nearly all of these types of hose have three things in common (see

Figure 14-5):

• A tube or inner liner that resists penetration by the fluid being used—This tube should be smooth to reduce friction. Some of the materials used for the tube are neoprene, synthetic rubber, and so on.

• A reinforcement that may be in the form of rayon braid, wire braid, or spiral-bound wire—The strength of the hose is determined by the number of thickness and type of reinforcement. If more than one thickness of reinforcement is used, a synthetic type of separator is utilized. A three-wire braid type of hose is made of three layers of wire braid.

• An outer cover to protect the inner portion of the hose and to enable the hose to resist heat, weather, abrasion, and so on— This cover can be made of synthetic rubber, neoprene, woven metal, or fabric.

Figure 14-5 Section of hose assembly showing the layers of material, including the inner liner, reinforcement, and outer cover.

(Courtesy Imperial-Eastman Corporation)

The nominal size of hose is specified by ID (such as

-inch, ¼-inch, 3/8-inch, ½-inch, and so on). The outside diameter of hose depends on the number of layers of wire braid, and so on. Fluid power applications may require hose with working pressure ratings ranging from approximately 300 psi to 12,000 psi.

Table 14-4 shows specifications for a typical two-wire braid hose. The hose and the couplings that are attached at each end of the hose make up the hose assembly for fluid power applications. Several methods are used to attach these couplings to the hose, including the following:

• Pressed on by mechanical crimping action. Production machines can be used to make large quantities of the assemblies.

•

Screwed on by removing the outer cover of the hose for a required distance that is marked on the shell of the fitting. The shell is then threaded onto the braid, and the male body can be screwed into the hose and shell assembly. In some types of couplings, it is unnecessary to remove the outer cover. Screwedon couplings can be disassembled and used again.

Table 14-4 Specifications for a Typical Two-Wire Brald Hose

• Clamped on by screwing the hose onto the coupling stem until it bottoms against the collar on the stem. Then, the hose clamp is attached with bolts. Some couplings require two bolts, and others require four bolts for tightening the clamp on the hose.

• Pushed on by pushing the hose onto the coupling. This type of coupling is used in low-pressure applications up to 250 psi. No tools except a knife to cut the hose to length are needed to make this type of assembly. This type of coupling is reusable.

Figure 14-6 shows various types of ends that are used on hose couplings. This permits the user a wide choice.

Hose assemblies are measured with respect to their overall length from the extreme end of one coupling to the extreme end of the other coupling (see

Figure 14-7). In applications, using an elbow coupling, the length is measured from the centerline of the sealing surface of the elbow end to the centerline of the coupling on the opposite end.

The length of a hose assembly that is to be looped can be determined from

Figure 14-8. In addition, the diameter of hose required to ensure proper performance of hose for hydraulic service can be determined in

Figure 14-9.

Figure 14-6 Common types of ends used on hose couplings.

(Courtesy Imperial-Eastman Corporation)

Figure 14-7 Method of measuring the length of a hose assembly.

(Courtesy Imperial-Eastman Corporation)

Figure 14-8 Typical dimensions for one-wire and two-wire braid hose in determining length.

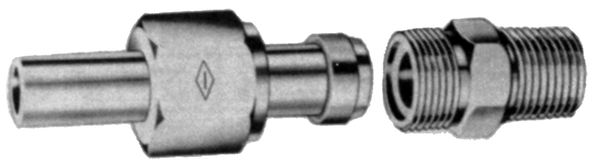

In applications in which it is desirable to disconnect one end of a hose assembly repeatedly, quick-disconnect couplings are recommended. The quick-disconnect couplings save considerable time in making or breaking the connection. When properly chosen, quick-disconnect couplings provide positive shutoff, so that the fluid is not lost.

Figure 14-10 shows a quick-disconnect coupling with double shutoff; when the coupling is disconnected, the valved-nipple and the valved-coupler prevent the escape of fluid. Quick-disconnect couplings are also furnished in various other combinations, such as a single shutoff coupling with a plain nipple and a valved-coupler, and a no-shutoff coupler with a plain nipple and a plain coupler. Quick-disconnect couplings are available in a wide range of sizes from ¼-inch to 4-inch pipe size. Larger sizes are usually available as “specials.” Various metals (such as brass, aluminum, stainless steel, and alloy steel) are used. Seals in these couplings depend on the type of service involved. The fitting connections on the ends of the couplings are available in several forms, such as female (NPT), male (NPT), hose shank, female (SAE), male flare, bulkhead, and so on.

Figure 14-9 Method of determining the correct size of hose.

(Courtesy Imperial-Eastman Corporation)

(Courtesy Snap-Tite, Inc.)

Figure 14-11 shows correct and incorrect installation methods for hose assemblies.

Manifolds

Manifolds are designed to eliminate piping, to reduce joints (which are often a source of leakage), to conserve space, and to help streamline equipment. Manifolds are usually one of the following types:

• Sandwich

• Cast

• Drilled

• Fabricated-tube

The sandwich type of manifold is made of flat plates in which the center plate or plates are machined for the passages, and the porting is drilled in the outer plates. The passages are then bonded together to make a leakproof assembly. A cast-type manifold is designed with cast passages and the drilled ports. The casting may be steel, iron, bronze, or aluminum, depending on the fluid medium to be used. In the drilled type of manifold, all the porting and passages are drilled in a block of metal. The fabricated-tube type of manifold is made of tubing to that the various sections have been welded. This makes an assembly that may contain welded flange connections, valve sub plates, male or female pipe connectors, and so on. These assemblies are usually produced in large quantities for use on the hydraulic systems of mobile equipment. The assemblies are held to close tolerances, because they are manufactured in fixtures. Although manifolds are used mostly on hydraulic systems, the demand for them in pneumatic systems is increasing.

Figure 14-11 Installation of hose assembly.

(Courtesy The Weatherhead Co.)

Summary

Fluid lines or piping is found in three categories: rigid, semi-rigid, or tubing (flexible or hose). In many instances, all three categories of piping are employed in a single fluid system.

The size of rigid pipe is indicated by the nominal inside diameter (ID), that is actually a misnomer. For example, the inside diameter of a ¼-inch Schedule 40 pipe is 0.364 inch, and the inside diameter of a ½-inch Schedule 40 pipe is 0.622 inch.

Two types of steel tubing are utilized in hydraulic systems, as recommended by USASI hydraulic standards: seamless and electric-welded. Tubing size is indicated by the nominal outside diameter (OD) of the tubing.

Flexible pipe (hose) is utilized in a fluid power system in which the movement of one component of the system is related to another component. The size of a hose is indicated by the nominal ID (such as

-inch, ¼-inch, and so on).

Manifolds are designed to eliminate piping, to reduce joints that are often a source of leakage, to conserve space, and to help streamline modern-day equipment. Manifolds are usually one of the following types: sandwich, cast, drilled, and fabricated-tube.

Review Questions

1. List the three types of fluid lines or piping.

2. What are the advantages of steel pipe as a fluid carrier?

3. What are three types of tubing commonly used in fluid power systems?

4. What is the chief advantage of hose in fluid power systems?

5. What is the chief advantage of manifolds in fluid power systems?

6. How may the efficiency of a fluid power system become limited?

7. What does Schedule 40 pipe mean as compared to Schedule 80?

8. Describe where XXS pipe is used.

9. What is one of the least expensive fluid carriers for hydraulic fluids?

10. What is the outside diameter of a ¾-inch pipe?

11. What is the ID of a 1-inch Schedule 80 pipe?

12. Why is copper tubing restricted for hydraulic service?

13. For what type of systems is seamless aluminum tubing used?

14. What are the types of materials used in making plastic tubing for fluid power lines?

15. What is the recommended maximum working pressure for a 1-inch ID two-wire braid hose?

16. What does NPT mean?

17. List four types of manifolds.

18. What are the two types of steel tubing used in hydraulic lines?

-inch, ¼-inch, 3/8-inch, ½-inch, and so on). The outside diameter of hose depends on the number of layers of wire braid, and so on. Fluid power applications may require hose with working pressure ratings ranging from approximately 300 psi to 12,000 psi. Table 14-4 shows specifications for a typical two-wire braid hose. The hose and the couplings that are attached at each end of the hose make up the hose assembly for fluid power applications. Several methods are used to attach these couplings to the hose, including the following:

-inch, ¼-inch, 3/8-inch, ½-inch, and so on). The outside diameter of hose depends on the number of layers of wire braid, and so on. Fluid power applications may require hose with working pressure ratings ranging from approximately 300 psi to 12,000 psi. Table 14-4 shows specifications for a typical two-wire braid hose. The hose and the couplings that are attached at each end of the hose make up the hose assembly for fluid power applications. Several methods are used to attach these couplings to the hose, including the following:

-inch, ¼-inch, and so on).

-inch, ¼-inch, and so on).