Do you find it weird that health and happiness is even being discussed in a leadership book? Do you never even think about your own physical well-being unless you are feeling ill or especially run down? If you are aware of your own health do you still find it almost impossible to find the energy or motivation to do anything about it? Has your weight crept up over the years? Do you hear stories of CEO collapse, exhaustion and heart attacks thinking it will never happen to you? Do you think these incidents are rare or media exaggerations? Are you still enjoying your work or is it just a hard grind? Is the big salary really worth the pain? Do you even have time to enjoy that money or is the work relentless? Do you often wake up in the middle of the night worrying about work and unable to get back to sleep? Do you feel permanently under pressure, undervalued and stressed but simply accept it as the price you have to pay for your position? If so, you’re not alone.

In business two things happen when it comes to health and well-being – either we completely ignore it, assuming it’s irrelevant to business success and performance, or we know it’s important but don’t have the time or inclination to do anything about it.

Commercial life is bruising, the pressure is unrelenting and yet most CEOs and business leaders do not have the time to address the health implications of their lifestyle. Most simply dismiss the stories they read such as Lloyds Banking Group CEO António Horta-Osório stepping down for six weeks’ stress leave as a ‘one off’ or an ‘exception’. They are not. The founder of JD Wetherspoon, Tim Martin, took a sudden six-month sabbatical before returning to the pub chain in April 2004 as non-executive chairman, working three days a week. Former Barclays chief executive John Varley left Barclays for one year in 1994 because he was ‘feeling quite worn out’ and ‘needed to do something different’, and Jeff Kindler of Pfizer resigned as chief executive of the US pharmaceutical giant to ‘recharge [his] batteries’ (Treanor, 2011).

In the last decade there have been more and more cases of people keeling over at their desks. In Japan, they even have a term for it – karoshi, which literally translates as ‘death from overwork’. In China this phenomenon is known as guolaosi and countless examples of sudden death through overwork are being reported. And most disturbingly of all according to statistics published by the China Association for the Promotion of Physical Health, at least a million people in China are dying from overwork every year (Liaowang Eastern Weekly, 2006; Birchall, 2011).

Apart from the health, social and emotional cost involved, this can also be extremely detrimental to the business. If a key member of the team drops down dead or needs to take time off to recuperate following a serious illness, then clearly there are long- or short-term succession issues and the loss will be felt in the team, and on the profit and loss account. Conversely when individuals at any level are healthy and happy at work they are much more likely to unlock discretionary effort that can have a profoundly positive impact on results.

If we are not paying attention to our health then we are almost certainly eroding it. We may all think we know what to do to improve our health but it never seems quite enough to push us into consistent action. Instead our lives are characterized by coffee-laden mornings and boozy nights. Often we don’t even want to speak to anyone until we’ve had our double espresso or macchiato hit. And at the end of the day we choose to unwind with a glass of whisky or a stiff gin and tonic. A few years ago it was ‘just the one’ but these days it’s always two and sometimes more.

We still dream of our two weeks in the sun – if only so we can put the guilt on hold and convince ourselves that we’ll get serious about the changes we know we need to make when we get home. Only they never happen. Life just keeps getting in the way.

Looking back on our life and career there were some really great experiences – pay rises, product releases, profit targets reached, promotions and bonuses that felt great at the time. But those feelings of success and euphoria never seemed to last. Whatever the achievement, time soon normalized it and the treadmill began again. Besides, happiness has no real place in modern business. But how we feel on a daily basis is not just some touchy feely idea; it is probably one of the most important factors that determine our most prized asset – our health.

There is a growing interest amongst scientists and physicians in the concept of coherence and its implications for health (Ho, Popp and Warnke, 1994). As renowned sociology and expert in stress, health and well-being Aaron Antonovsky said, ‘We are coming to understand health not as the absence of disease, but rather as the process by which individuals maintain their sense of coherence (ie, sense that life is comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful) and ability to function in the face of changes in themselves and their relationships with their environment’ (Antonovsky, 1987).

So what impacts health and happiness? Well, it’s probably not what you think… There is now a considerable amount of scientific data showing that mismanaged emotion is the root cause. Mismanaged emotion is the ‘superhighway’ to disease and distress. Your emotions not only determine whether you are likely to become ill and how happy you feel but also determine whether you will do a good job and get promoted.

According to the adage, ‘You are what you eat.’ But such statements do not really recognize the profound sophistication of the human body to adapt and work with what it is given. It is amazing how well people can function despite a very poor diet. Don’t get me wrong; I am a big believer in nutritional discipline and the importance of optimizing what we eat in order to enhance energy, avoid bloating and stay trim. But we can, excuse the pun, overcook the importance of food. And, for the record, taking additional nutritional supplements won’t make much difference either because the body is often unable or unlikely to absorb most of their goodness anyway. Essentially, most supplements leave the body in much the same condition they went into the body so we are literally pouring money down the toilet! The gut is an incredibly complicated and interconnected ecosystem that is influenced and affected by the delicate balance of flora and fauna in our intestines, levels of circulating trace elements and the chemical balance in our system. It’s unrealistic to assume that bulk-manufactured supplements will deliver the right nutrients to the right systems at the right time in the right composition to make any significant difference. Eating high-quality food is by far the best way to get the nutrients we need.

Exercise is also important and I would certainly go to the gym every day if I weren’t so busy. The benefits of a regular workout are legion particularly if we are doing an exercise we love, which in my case is rowing. But there is something that in my view trumps the benefits of eating (the first ‘Big E’) and exercise (the second ‘Big E’), and that is emotion or the third ‘Big E’.

We exercise perhaps up to five times a week, if at all. We eat two or three, perhaps four times a day. Emotions, on the other hand are affecting us every second of every day. They also largely determine whether we can be bothered to exercise, and what, when and how much we eat. As psychiatrist and pioneer in the field of psychosomatic medicine Dr Franz Alexander said ‘Many chronic disturbances are not caused by external, mechanical, chemical factors, or by microorganisms, but by the continual functional stress arising from the everyday life of the organism in its struggle for existence’ (Alexander, 1939).

I appreciate that the idea of emotions being more important than exercise and eating may come as a bit of a surprise. Despite considerable scientific research documenting the connection between health and emotions, few business leaders take it seriously. If it’s not immediately dismissed as ‘new-age happy-clappy’ fiction, the ‘health piece’ is delegated to their chief medical officer or their occupational health department. Some businesses may seek to ‘tick the health box’ by installing a gym or pool, and occasionally physiotherapists or gym instructors are employed, but the health and fitness of leaders and employees are largely seen as a private matter of individual choice.

Health and happiness are simply not considered commercially relevant. But surely when a high-profile leader collapses at his or her desk or needs to take extended sick leave – that’s commercially relevant! When study after study proves categorically that happy, engaged employees work harder and longer, and provide significantly better customer service – that too is commercially relevant. Maybe it’s time to put health and happiness on the business agenda – if for no other reason than to help unlock discretionary effort!

Health: the facts and the fiction

Most executives see health and happiness as a matter of personal choice or a conversation between them and their doctor. But are doctors the right people to turn to for guidance on health and happiness? As a medical doctor myself I can assure you that doctors are not trained in illness prevention or happiness; they are trained to treat illness and disease once it has become well established. If we want to be healthy and happy well into old age, we need to appreciate how medical thinking has changed over the years so we can separate the facts from the fiction.

Up until the mid-1940s there really wasn’t that much in the way of effective medicine. If someone got toothache, pneumonia, meningitis or an STD, then they probably died from it because there were no antibiotics. As a result the biggest killer of both men and women was infectious disease. Although penicillin was discovered by Alexander Fleming in 1928 it wasn’t purified and used as a mass-produced antibiotic until 1944 – during the Second World War. Antibiotics were phenomenally successful and most of what was killing us prematurely was eradicated almost overnight. A philosophy of ‘the magic bullet’ was born and scientific medicine started to hunt for single treatments that could eradicate complex multi-factorial diseases (Le Fanu, 1999).

For the first time in history we believed that we finally had the upper hand over disease, and the ‘magic bullet’ approach changed the nature of medical thinking. If we could discover a pill that could cure all these infectious diseases, then surely it was just a matter of time before we found a magic bullet for the other big killers such as heart disease and cancer. And health researchers moved en masse to find those magic bullets, initially turning their attention to heart disease, which, following the advent of readily available penicillin, had been promoted from the number two killer to the number one killer – a position it’s maintained ever since (Townsend et al, 2012). In the developed world today, at least a third of all premature deaths, male and female, are caused by cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease, hypertension and stroke (World Health Organization, 2011). Traditionally, women are often more concerned with breast cancer, but actually heart disease now kills up to 10 times more women than breast cancer (British Heart Foundation website; Society of Women’s Health Research, nd).

The first sign of heart disease in 60 per cent of men is death (Society for Heart Attack Prevention and Eradication, 2013; News Medical, 2012). This stark statistic says much about people’s ability to notice an imminent disaster. Many people are pressing on unaware of the impending doom. Doctors themselves are not necessarily any better at spotting the warning signs because they’ve been trained to spot symptoms, not warning signs. Traditional medical teaching rarely focuses on the anticipation of a crisis. Rather it tends to wait until the crisis has occurred and then attempt heroic intervention. Consequently, many people who suffer a heart attack simply did not see it coming, and neither did their physician. Most people believe that heart attacks or illnesses ‘come out of the blue’. Of course they don’t; most medical conditions have been brewing for months if not years. The main problem is we just don’t see the signs or heed the signals.

In an attempt to change this so we could identify those early signs, and hopefully reduce mortality rates, the US government, specifically US health policy-makers, joined forces with the medical community to solve the mystery of heart disease by conducting a long-term research project into the causes of heart disease in an ‘average’ American. To do this they needed to identify ‘anytown USA’ that was representative of the US population (Lynch, 2000). The town they chose was Framingham.

Heart disease: the Framingham heart studies

At the time Framingham was a small, beautiful, leafy town of 28,000 working people, 20 miles from Boston. It was extremely stable socially – if someone was born in Framingham they usually lived and died there too. This was essential for the research because the study was going to monitor the health of 5,209 volunteers every two years for the next 50 years! It would have been extremely difficult to conduct this research if the subjects moved away and ended up being scattered across America. And so in 1948 a small army of medical scientists descended on the town, and research data into the causes of heart disease has been pouring out of the Framingham Heart Studies ever since. The longevity of the study and the depth of the data collected means that the findings at Framingham have influenced medical thinking in this area more than anything else – by far.

But as it turns out, Framingham was not ‘anytown USA’. Because the researchers didn’t know what they were looking for or what they would find, it didn’t occur to them that Framingham wasn’t actually representative of America. It was a small, mostly white, mostly middle-class town that enjoyed almost total employment. There was very little poverty; the divorce rate of 2 per cent was considerably lower than the national average at the time of 10 per cent. It was also incredibly socially cohesive – everyone knew everyone else in the town and there was strong social support. Framingham was – socially at least – nothing like inner city Detroit, Las Vegas or New York. And frankly, even if the researchers had realized this fact, there was absolutely no evidence to suggest these issues had any bearing on heart disease.

Ironically, the researchers had chosen a town that just happened to be naturally insulated from heart disease in the first place. As a result, the causes of heart disease in Framingham were never going to be the same as the causes of heart disease in inner city Detroit, Las Vegas, New York or just about any other large town or city in America. The researchers had inadvertently discounted a vast array of contributing factors that have struggled to become recognized as contributing factors ever since. Things like poverty, social inequality, low educational attainment, stress, social isolation, depression, anxiety and anger didn’t even exist in Framingham! So of course they didn’t find them.

It follows therefore that if many of the real driving forces for heart disease were absent from the research group, then what’s left are the ‘other’, possibly less important, contributing factors for heart disease – high blood pressure, cholesterol, age, diabetes, smoking, obesity/lack of exercise, other medical conditions and family history. And it is these other ‘causes’ that have since been written into medical law as the ‘traditional risk factors’ for heart disease. The truth however is that over half of all the incidence of heart disease can’t be explained by the standard physical risk factors (Rosenman, 1993). Doctors all over the world are scratching their heads because people are dying of heart disease every day even though they exhibit none of the so-called risk factors. The real reason they are dying is, largely, because of mismanaged emotions such as depression, anxiety, anger, hostility and cynicism brought on by poverty, social inequality, low educational attainment, stress and social isolation.

It wasn’t that Framingham was some utopian nirvana where nothing went wrong and everyone was happy, it was just that when the inevitable knocks and bumps of life occurred the inhabitants of Framingham had strong social networks to help them through. Those types of networks are not always present in large, transient cities and these real risk factors are hugely important. Ironically Framingham inadvertently discovered the antidote for heart disease – healthy emotional management that is manifest through strong social bonds and social cohesion.

Don’t get me wrong, the Framingham heart research has improved our understanding and treatment of heart disease considerably. The traditional risk factors are important but not as important as the social, educational, interpersonal or physiological factors that were almost entirely absent from Framingham.

In an effort to raise awareness of these critical but largely ignored causes of heart disease, Dr James Lynch went back and re-analysed all the data from Framingham. What he discovered was that when those original 5,209 volunteers aged between 30 and 62 were initially interviewed, the only information that was gathered was medical – height, weight, blood pressure and a host of other physical factors. The researchers neglected to record any social, educational, interpersonal or physiological data at all, and yet those are the things that probably account for most of the ‘inexplicable’ cases of heart disease where no risk factors are present.

Whilst the Framingham Heart Studies have produced incredible insights into heart disease, they have also inadvertently caused the general public and medical professionals the world over to minimize or ignore the most important risk factors in heart disease – mismanaged emotions.

Everyone knows that smoking is bad for you and we are rightly bombarded with adverts telling us to stop smoking. Everyone knows that it is especially bad after someone’s had a heart attack. In fact people are twice as likely to be dead within a year of their heart attack if they smoke. What is less well known however is that if a person is depressed after their heart attack they are four times as likely to be dead within one year (Glassman and Shapiro, 1998). But we don’t see adverts telling us to ‘Cheer up! Stop being so miserable – it’s killing you!’

Some doctors, aware of the significant link between depression and heart attack, have sought to treat heart attack patients with anti-depressants. Whilst sensible and often brave, this hasn’t always worked because the current treatment options of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) or drugs only make a difference to some patients (Antonuccio et al, 1995). As a result the medical profession has often wrongly concluded that depression is not a big deal when it comes to heart disease. It is just that the current treatments don’t address the root cause of depression, which is mismanaged emotion.

Depression is on the increase and according to a recent global analysis project, if current trends continue, depression will be the second greatest disease burden by the year 2020 and the first by 2030 (Murray and Lopez, 1996). It is now estimated that 350 million people globally are affected by depression (World Federation for Mental Health, 2012).

Mismanaged emotions such as worry, hopelessness, anxiety and depression are seriously toxic. The Harvard School of Public Health conducted a 20-year study on the effects of worry on 1,750 men. Researchers found that worrying about typical issues such as social conditions, health and personal finances – something most of us are familiar with – all significantly increased the risk of developing coronary heart disease (Kubzansky et al, 1997). In fact, hopelessness in middle-aged men is as detrimental to cardiovascular health as smoking a pack of cigarettes a day (Everson et al, 1997).

Anxiety, worry and panic have also been associated with diminished heart rate variability (HRV), which as you may remember from the previous chapter is a potent risk marker for heart disease and sudden cardiac death as well as ‘all-cause mortality’ (Dekker et al, 1997).

But these negative emotions are not just toxic for our physical health; they are having a considerable impact on our ability to be happy, content and fulfilled. Anxiety, hopelessness, worry, panic and even the vast majority of depression are caused primarily by our inability to regulate our own emotions. Please understand I’m not saying people who suffer from these negative emotions are making them up; I’m just saying the cause is not medical. The real problem is that, collectively, we have not been taught about emotion, how to differentiate between various emotions and how to manage them effectively. As children, when we were upset most of us were told to calm down, ‘pull yourself together’ and stop crying. Even if we were bursting with excitement or some other positive emotion we were told to calm down! We were never taught how to distinguish between upset and anger or anger and boredom or boredom and apathy, and even if we could tell the difference we were almost certainly not taught how to manage those emotions, take appropriate action or change the emotion.

As a result most people believe that emotion is something to be avoided or hidden. It’s as though emotion is considered part of our childhood that must be shed like a beloved comfort blanket or favourite toy as part of the inevitable metamorphosis from emotional child to fully functioning adult. As a result we learn to ignore and suppress emotion and proceed into adulthood with a degree of emotional literacy that can differentiate between ‘feeling good’ and ‘feeling bad’ and little else. All the negative emotions congeal into ‘bad’ and all the positive emotions congeal into ‘good’. If we experience more ‘bad’ emotion then ‘good’ emotion, then the ‘bad’ elongates into a negative mood that over time acts like grooves on an old LP record. The person then plays the same negative tune over and over again until it becomes an ingrained habit. The vast majority of people who are diagnosed with depression or anxiety disorders don’t have a medical condition (yet); their record player has just got stuck playing the emotional record of anxiety or sadness and they don’t know how to cut the power or change the record to something more upbeat and positive. And this is having a huge impact on individual happiness.

What’s more, emotional and stress-related disorders significantly impair productivity. In one study depression was identified as the most common mental health condition, responsible for 79 per cent of all time lost at work – significantly more costly to the employer than physical disease (Burton et al, 1999).

Cancer

Cancer is currently the second biggest killer, responsible for about a third of all deaths in the developed world (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). That means that heart disease and cancer collectively account for almost 70 per cent of all premature deaths! And negative emotion has been proven to drive both. Way back in 1870, Queen Victoria’s physician and surgeon, Sir James Paget, stated, ‘The cases are so frequent in which deep anxiety, deferred hope and disappointment are quickly followed by the growth and increase of cancer that we can hardly doubt that mental depression is a weighty addition to the other influences favouring the development of a cancerous constitution’ (LeShan, 1977).

Since then the evidence has been mounting and there is now significant robust scientific data that demonstrates the clear link between psychological factors and the development of tumours (Grossarth-Maticek, 1980; Pettingale et al, 1981; Levy et al, 1988). So much so that it has been said, ‘the data are now so strong that [they] can no longer be ignored by those wishing to sustain a scientific attitude towards the cancer field’ (Bolletino and LeShan, 1997). There is now zero doubt that the superhighway to disease, including cancer, is mismanaged emotions.

The big questions regarding cancer have been: ‘Can we predict who gets cancer?’ and ‘Can we predict who is then going to survive cancer?’ And in most cases, the answer to both these questions is a resounding ‘YES!’ (Nabi et al, 2008).

There was, for example, a large-scale Scandinavian trial that sought to correlate emotional outlook to cancer by researching subjects in their 50s and 60s, which is the age people tend to get cancer, and cross-referencing their results to their university entrance exams. So the researchers went back to these people’s university psychometric tests to see if there was anything about those people in their early 20s that would correlate to their propensity to get cancer 30 or 40 years later. Studying over 25,000 people they discovered that there was a direct correlation – those who were negative when they were 20 and who had remained perpetually negative throughout their life were the ones that were more likely to develop cancer (Eysenck, 1993).

Phychologist and the ‘Father of Positive Psychology’ Dr Martin Seligman and two colleagues studied members of the Harvard graduating classes of 1939 to 1944 (Goleman, 1987). Following their return from the Second World War, the men were interviewed about their war experiences and physically examined every five years. Where the post-war interviews indicated that individuals had been optimistic in college, their emotional disposition directly correlated to better health in later life. Seligman stated that, ‘The men’s explanatory style at age 25 predicted their health at 65,’ adding ‘Around age 45 the health of the pessimists started to deteriorate more quickly.’ People’s explanatory style impacts how they explain the inevitable ups and downs of life to themselves, which in turn influences their behaviour and performance. For example, pessimists interpret a failed exam or missed promotion as though it were a permanent reflection of their own personal failings that will infect all areas of their life. Optimists, who have greater emotional intelligence, will look at the same event or situation and see it as temporary, fixable and only confined to the area it originally affected.

If we are negative, if we feel that we can’t control our destiny, if we feel put upon and internalize our frustrations instead of talking about them and finding solutions then, to quote Woody Allen, we ‘will grow a tumour’. Emotional distress can influence the incidence and progression of cancer (Kiecolt-Glaser et al, 1985).

The locus of control

Our emotional well-being is also significantly influenced by how much control we feel in our lives. The original Whitehall Study (Marmot, 1991) conducted by principal investigator Sir Professor Michael Marmot discovered that there was a strong association between the ability to control our own destiny and mortality rates. After studying over 18,000 men working in the British Civil Service, Marmot found that the civil servants employed at the lowest grades or levels such as messengers and doorkeepers were three times more likely to die than those employed in the top grades or levels such as administrators. Even when Marmot controlled for the traditional risk factors, he found that those at the bottom of the organizational ladder were still twice as likely to die as those at the top. Whilst the stress may have been more significant at the top, those individuals also had more control over their day.

Ellen Langer, Professor of Psychology at Harvard, conducted a now famous study with colleague Judith Rodin in the 1970s that also demonstrated the connection between mortality and control. Nursing home residents were split into two groups. The first group were encouraged to find ways to make more decisions for themselves. They were for example allowed to choose a houseplant for their room and it was their responsibility to care for the plant. They could also choose when they had visitors or when they watched a movie. The idea was to encourage this group of residents to become more mindful and engage with the world and their own lives more fully. The second group did not receive these instructions and were not encouraged to do anything differently. They were given a houseplant but the nursing staff chose the plant, decided where it would sit in their room and took responsibility for watering the plant. Based on a variety of tests conducted at the start of the experiment and then again 18 months later, members from the first group were more cheerful, active and healthier. What was however more surprising was that less than half as many residents from the engaged group who could demonstrate personal control had died compared with those who had no control (Langer, 2010). Langer stated, ‘The message is clear – those who do not feel in control of their lives are less successful, and less psychologically and physically healthy, than those who do feel in control.’

How this works biologically is that if someone is negative or feels as though they have limited control over their life, their body creates more cortisol and cortisol suppresses the immune system. We all, for example, generate cancer cells in our body every day but if someone is cheerful, positive and emotionally coherent most of the time, then their immune system will simply flush out those potentially problematic cancer cells as part of its normal function. This doesn’t happen if someone is perpetually miserable or emotionally incoherent. Once cortisol levels have suppressed the immune system over a long period of time, the cancer cells are not adequately disposed of by the poorly functioning immune system and instead they can take hold and develop into cancer.

The emotional component is also critical for cancer survival, as evidenced by a very famous study conducted by David Spiegel and psychiatrist Fawzy I Fawzy, who recruited 86 women with advanced metastatic breast cancer of similar age. All the women received the same medical care but two-thirds were randomly assigned to group meetings of one and a half hours per week for a year. As a result these women had the opportunity to get together and talk to each other and share the difficulties they experienced first-hand, discuss their treatment, laugh and cry together through their mutually harrowing experience. The other third was the ‘control’ group and they only received the medical treatment.

Logic and common sense alone would suggest that those with social support probably did better – after all ‘a problem shared is a problem halved.’ But the results were nothing short of remarkable. The women with the social support reported less pain and lived 18 months longer than the control group, which effectively doubled their life expectancy (Watkins, 1997). So even if someone gets cancer, whether they survive or not is massively influenced by their emotional well-being and whether or not they have access to social and emotional support.

Happiness: the facts and the fiction

Whilst conceptually health and happiness may mean very different things, especially to busy executives who don’t consider either terribly relevant to quarterly results, in practical daily life it’s virtually impossible to separate health from happiness – the two are inextricably linked. When someone has the ‘giving-up–given-up complex’ (Engel, 1968) or experiences ‘the emotional eclipse of the heart’ (Purcell and Mulcahy, 1994), their gloomy expectation and negativity will facilitate a host of negative consequences – physically and mentally. Those that are more optimistic or are at least able to manage their emotions and use their feelings to initiate constructive action to solve their problems are almost always healthier and live longer, happier, more contented lives. That fact is unequivocal.

Interestingly, the scientific literature on the negative consequences of emotions is about 10 times larger than the evidence on the beneficial effects of positive emotions. Psychology and psychiatry, for example, are almost exclusively focused on dysfunction, studying it and treating it respectively. In fact, for decades, it was widely considered ‘a career-limiting move’ or academically inappropriate to research happiness or elevated performance from an emotional perspective.

Thankfully ‘positive psychology’ has gathered pace over the last 30 years and we now realize that we can actively alter our emotional outlook, which in turn can enhance our immune system and increase our protection and resilience against disease and illness. We also now realize that positive emotions that make us feel happy, contented and confident can be learnt, practised and incorporated into our daily lives. For years we were told that happiness and positivity were largely genetic – we were either born optimistic or we were born pessimistic. It’s not true. Optimists may have won the ‘cortical lottery’ (Haidt, 2006) because they habitually look on the bright side and more easily find the silver linings, but this ability is open to all of us. Thanks to research giants such as Abraham Maslow, Aaron Antonovsky, James W Pennebaker, Tal Ben-Shahar, Dean Ornish, Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi amongst others, we now understand that our emotional outlook is not fixed as a permanent set point but rather that we each have a range. Whether we view the glass as half-empty or half-full can be significantly altered through emotional coherence and self-management so that we habitually operate at the top end of that emotional range.

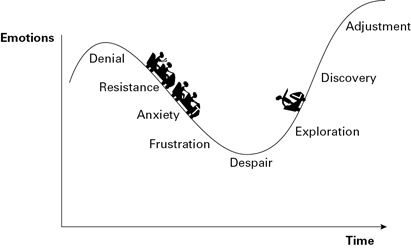

When crisis strikes – and it does for everyone at some point in life – most people will deal with crisis in one of three main ways. They will get into action and fix the problem (active coping), reappraise the situation (engage in inner emotional and cognitive work to find the silver lining) or avoid the problem (engage in distraction tactics such as alcohol or drugs so they can forget or blunt the emotional reaction) (Carver, Scheier and Weintraub, 1989; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984).

In the 1970s Holmes and Rahe developed the stress scale as a way to correlate difficult, traumatic or stressful ‘life events’ so we could better understand the effects of these events on health and happiness. Of course it was also hoped that these insights would lead to a way to help people find the right coping strategy for crisis.

Holmes and Rahe found that if someone experienced several life events such as divorce, death of a loved one, redundancy or moving house, they would be more susceptible to physical illness, disease or depression. And this became medical ‘fact’. But the ‘evidence’ that proved this ‘fact’ also clearly demonstrated something else… Some individuals were experiencing a great many of these major life events and yet they were not adversely affected, mentally or physically, over the longer term. Clearly it was not the life event that predicted illness but rather the way the individual responded to those events and what they made them mean.

The active ingredient is what is known as post-traumatic growth – the ability to find something positive and beneficial out of even the most difficult experiences. This is not optimism or pessimism per se, but the ability to manage emotion and manage meaning. Social psychologist Jamie Pennebaker’s work has shown that the event isn’t the issue; what matters is what happens after the event and what the individual makes the event mean to them as a person and their future life (Pennebaker, 1997).

When people were able to express themselves emotionally and talk about what happened within social networks or strong relationships they were largely spared the damaging effects of trauma to physical and mental well-being. (Remember this when we explore the potent impact of positive relationships for personal and professional success in Chapter 6.) Those with greater emotional coherence were also better able to put a cognitive frame around the event that allowed them to make sense of what happened and move on.

How we view the world is not set in stone. We may not always have control over situations or events but we always have control over how we interpret them, what we do about them and what we make them mean.

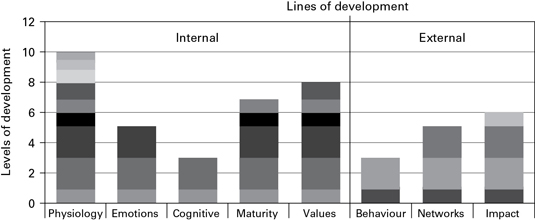

From a business perspective it has also been found that those who are mentally healthy and happy have a higher degree of ‘vertical coherence’ among their goals and aspirations (Sheldon and Kasser, 1995). In other words they have dovetailed their short-term goals into their medium-term and long-term goals so that everything they do fits together and pulls them toward a future they want. I would go so far as to extend this definition of ‘vertical coherence’ to include coherence within all the areas of vertical development – especially, in this context, emotions.

Vicious cycles caused by mismanaged emotions

Clearly it’s not the event or situation that impacts the outcome; it’s what happens emotionally as a result of those events and situations that really makes the difference between life and death, success and failure, happiness and misery. This is the distinction that is so often missing in modern medicine.

Earlier I said that the real risks of heart disease were not so much the widely publicized traditional risks of blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes etc but the relatively unknown social, educational, interpersonal or physiological risks such as poverty, social inequality, low educational attainment, stress, social isolation, depression, anxiety and anger. These things in and of themselves won’t necessarily kill us, but what these things do to our biology can.

Low educational attainment doesn’t cause heart disease but it usually leads to poverty because the individual doesn’t have the knowledge, skills or self-confidence to earn a decent living, and that creates poverty. But even then it’s still not the poverty that is creating the heart disease; it’s the fact that poverty usually creates emotional distress, worry and pressure – especially if that person has a family to support. If the poverty creates emotional incoherence in the physiology then it is probably experienced as worry, panic, anxiety and depression. The person may feel worthless, helpless and socially isolated, which further suppresses the immune system and increases cortisol levels even more, thus laying the body wide open to a host of diseases, of which heart disease and cancer are just two.

One of commonest feelings that people live with is that they are ‘not enough’: that they are deficient in some way or there is something lacking in the world around them. These feelings of deficiency may be personalized into ‘I am not a good enough husband/wife, father/mother or friend.’ Women often specialize in feeling bad about their physicality: ‘I am too fat’ or ‘my (insert appropriate body part) is too big or too small.’ Men’s specialist inadequacy is often centred on their ability to provide, or their strengths and physical ability. Why don’t I have a six pack, or better biceps? Many people don’t feel good about themselves and lead lives of quiet desperation. Whether their backside looks big in those jeans or not is largely irrelevant; it’s what that observation does to the person’s physiology that screws up their health and happiness. In the same way it’s not actually the chocolate cake that makes someone unhealthy, or the fact that they didn’t go to the gym again this week – what’s doing the most damage is the self-flagellation, guilt, self-disgust and remorse they feel after eating the chocolate cake or not going to the gym again. That’s what’s really doing the damage. It’s important to understand that how we feel about what we’re doing often has a much bigger effect on health and happiness than what we are actually doing.

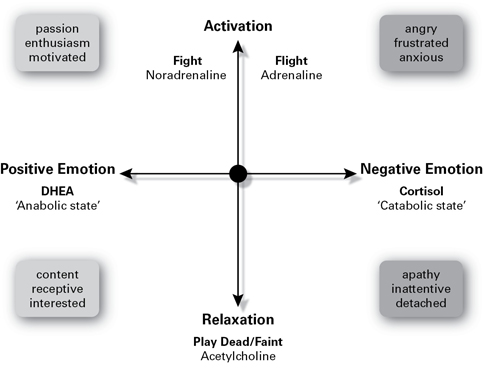

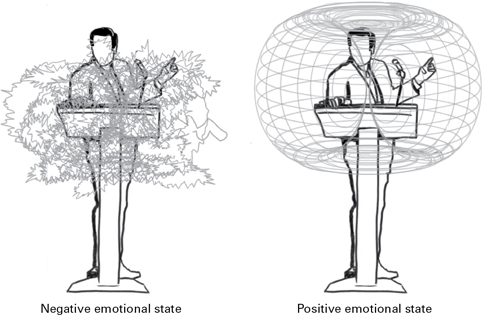

Take exercise for example. One of the primary benefits of exercise is determined by the way someone feels about the exercise. If you force yourself to go to the gym but don’t really enjoy it, then your body will react catabolically and you will be operating from the negative side of the performance grid. In other words your workout will be breaking your body down, not building it up. In contrast, if you love going to the gym the exercise will provoke an anabolic response and will be much more beneficial to you because you’re operating from the positive side of the performance grid (Figure 3.1) and you’re building your body up. In our coaching work we’ve seen many individuals who are exercising regularly but still have poor physiology, and when we have changed their exercise regime to incorporate routines that are much more enjoyable their physiology has improved significantly.

FIGURE 3.1 The performance grid

Remember, what we eat and how often we exercise are relevant to optimal health but they are nowhere near as relevant as we’ve been led to believe. Emotion is the elephant in the room. When we understand emotion and create emotional coherence so that we can differentiate between the various emotional tunes our body is playing and behave appropriately, then our health and happiness will improve dramatically.

The simple unequivocal fact about health and happiness is that emotion is the active ingredient, and developing emotional coherence will not only make you more productive but just might save your life.

Emotions and feelings: the critical difference

Most people, including medical professionals, use the words ‘emotion’ and ‘feeling’ as interchangeable terms, believing they are essentially the same thing. They are not.

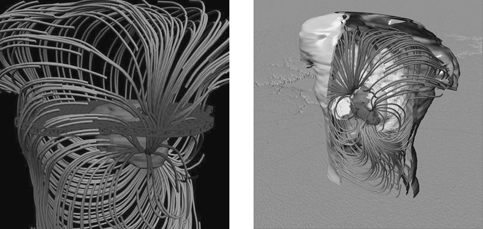

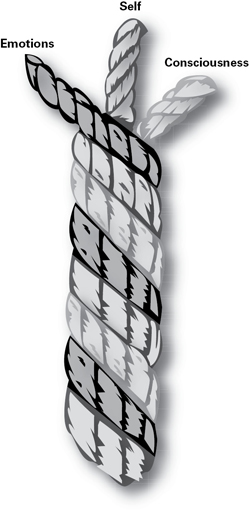

Going back to the integrated performance model (Figure 1.1) – physiology is just the raw data or the biological ‘notes’ that our body is playing. Emotion is the integration of all the various physiological signals or ‘notes’ into a tune. In contrast, a feeling is the awareness and recognition in our mind of the tune that is being played by your physical body. Or as neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux suggests, feelings are merely the ‘observation’ of the emotion (Coates, 2013).

These ‘notes’ are quite literally energy (E) in motion (e-motion). The human system is a multi-layered integrated hierarchy in a state of constant flux, with each system – heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, brain – playing a tune that contributes to the overall score of the orchestra. Our body is always playing a tune, whether we are aware of that tune or can recognize it or not. When we become aware of the tune that all our bodily systems are playing then we are ‘feeling’ the e-motion. Emotion is, therefore, the link between biology and behaviour – a fact not lost on Henry Maxey, CEO of Ruffer Investment Hedge Fund. Ruffer is an independent and privately-owned investment management firm employing over 160 people, with offices in London, Edinburgh and Hong Kong. When we interviewed Henry on his experiences with Enlightened Leadership he said:

The whole profession is about perceptions… Because it’s about perceptions, human behaviour plays a huge part, hence the importance of understanding the real drivers of behaviour, namely emotions. Since emotions play such a huge part in this job it’s very helpful to have some understanding of them, your emotional state and how that’s influencing your behaviour when you’re interacting with markets.

Learning how to create greater emotional coherence has therefore been extremely valuable. Henry was one of the very few analysts to predict the credit market collapse of 2007, successfully moving his client’s investments ahead of the turmoil and massively enhancing his firm’s reputation and profile as a result. You can read Henry’s case study at www.coherence-book.com.

Making the distinction between emotions and feelings may seem like semantics but it’s an absolutely crucial differentiation because it suddenly resolves so much of people’s misunderstanding about how we function. Moreover, differentiation is the second critical step in the evolution of anything, so if we want to develop as human beings we must elevate our ability to differentiate between different emotions, between emotions and feelings and feeling and thoughts. For us to develop as business leaders we need to improve our ability to differentiate things that are not traditionally thought of as related to business – human biology and human nature. Most of which isn’t even given a cursory nod in business school. And yet the benefits of this knowledge are phenomenal. When leaders, senior executives and employees understand that emotions and feelings are completely different phenomena, it enables them to learn how to control both and ultimately build better relationships with customers and colleagues alike.

There is little doubt that some individuals have already learnt a degree of emotional ‘self-control’ or at least they think they have. However, such self-regulation often only extends to the control of the more obvious manifestations of body language rather than the emotional energy itself. For example, an individual may be able to conceal the fact that he is feeling angry or is desperately unhappy. He may be able to stop himself from lashing out at a colleague or bursting into tears in a meeting, but this is usually no more than gross control of body language. It might look like he’s ‘got his act together’ but inside his body he is still experiencing the negative consequences of those negative emotional signals whether he actually feels the feeling or expresses those feelings or not. In other words it might look like he’s listening to Beethoven, and he may even be able to kid himself that his body is playing Beethoven, but his physiology is still reacting to what’s really going on – thrash metal at full volume.

Going back to our orchestra metaphor again, underneath the external façade of ‘controlled emotions’ is a vast number of individual musicians, each playing different ‘notes’ or sending subtle (and not so subtle) signals around the body. An examination of these uncontrolled signals can be a very revealing window on the underlying emotional state that is currently impacting the individual. Few people recognize, let alone control, the fine emotional nuances of their physiological orchestra.

And sophisticated control does not mean simply throwing a blanket over the whole orchestra; it means knowing how and when to allow the expression of each musician within the orchestra and how to bring coherence to the tune being played so as to create something genuinely astonishing. When we learn genuine control over our emotional repertoire then we alter our physiology and this can literally protect us from the illness and disease caused by mismanaged emotions. It can also protect us from poor decision making.

The business impact of conditioning

Shifts in our emotion can be triggered by the perception of anything external to us or by internal thoughts or memories. Most of what we perceive with our senses does not reach conscious awareness. We already know for example that the central nervous system is only capable of processing a tiny fraction of what it could be aware of via the five senses. The retina transmits data at 10 million bits per second, our other senses process one million bits per second and only 40 (not 40 million) bits per second reach consciousness (Coates, 2013). Our subconscious mind, ie the mind that is busy doing stuff we don’t have to think about like pumping blood or digesting food, is capable of processing 20 million environmental stimuli per second versus the rather puny 40 environmental stimuli that our conscious mind is processing (Norretranders, 1998).

So not only are we privy to a vast amount of data we are never consciously aware of but, because of a process called conditioning, any one of those millions of external cues could trigger an emotion that alters our behaviour or decision making without us knowing why.

The way we respond to the world around us is largely determined by unconscious emotional programming buried deep in our brain. Our mind is ‘conditioned’ to respond to the external world super-fast. So we are often unaware of our own emotional triggers and we may also lack awareness of the emotion itself, making it virtually impossible to distinguish between real external data and potentially erroneous data supplied by an outdated conditioned response.

Conditioning is an automatic survival and learning mechanism that starts soon after we are born and long before we are able to speak. The purpose of this automatic response is to evaluate threats to our survival and trigger a response that keeps us alive. And it’s made possible by the body’s emotional early-warning system – the amygdala.

Neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux from the Center for Neural Science at New York University was one of the first academics to highlight the key role – and shortcomings – of the amygdala in decision making. It is the amygdala that is often to blame when, feeling threatened, we blurt out something stupid in a meeting or get caught off guard by a journalist. In certain situations, the old maxim ‘think before you act’ is actually a biological impossibility.

Before LeDoux’s research it was thought that the sensory signals received via the five senses travelled first to the thalamus, where they were translated into the language of the brain. Most of the message then travelled to the neocortex so an appropriate response could be initiated. If there was an emotional component to those signals, a further signal was then passed from the neocortex to the amygdala for emotional perspective but the neocortex was considered to be the boss. We now know that this is completely incorrect.

Instead there is a neural emergency exit connecting the thalamus to the amygdala, which means that a smaller portion of the original message goes directly across a single synapse to the amygdala – bypassing the thinking brain altogether and initiating action before the rational brain even knows what’s going on. This allows for a faster response when our survival may be threatened. And all this happens in a fraction of a second below conscious awareness, and what becomes an emotional trigger largely comes down to individual conditioning.

Human beings are born with only two fears – falling and loud noises. Everything else, whether that is fear of failure, fear of success, fear of death, clowns, heights or spiders, we’ve learnt from someone else or from experience. As we grow up, we absorb a massive amount of information largely through conditioning and there are two types of conditioned learning. If we burn our hand on a hotplate we don’t ever do it again because the experience is sufficiently painful that the conditioning is immediate. Such experiences are called single-trial conditioning and, as the name would suggest, they teach us very quickly. When an experience is painful, either physically or emotionally, then we can learn that lesson with only a single exposure to the event or situation.

However, most learning is not that intense and involves ‘multiple-trial learning’ where we have to repeat the experience over and over again until it becomes a conditioned reflex or response. It was famous physiologist Ivan Pavlov who first discovered this innate biological response.

Working with dogs, Pavlov noticed that if he gave his dogs food while also making a sound such as blowing a whistle or ringing a bell, then over time the dogs would make an association between the two separate stimuli (being fed and the sound of the bell). With repetition it was therefore possible to get the dogs to salivate just by ringing the bell. Clearly there is no logical connection between salivating and the sound of a bell, and this highlights the often inaccurate and unsophisticated nature of the conditioning process. It matches stimuli that don’t necessarily belong together and the subsequent presence of one or more of those stimuli can then trigger an emotional response that doesn’t match the situation.

Part of the reason conditioning is so inaccurate is that the system is designed around survival not sophistication. A conditioned response is often blunt and can mean that we occasionally use a sledgehammer to crack a nut. Say someone ate a poisonous mushroom as a child and was violently ill for 24 hours; the conditioned response to that event would have been single exposure and the child’s brain would have immediately scanned the situation to establish the characteristic of the event so as to ensure it never happened again. Even after the child grows up and learns that there are many different types of mushrooms that are tasty they probably won’t ever eat mushrooms again, even if they don’t remember the mushroom incident that created the conditioning in the first place. Their rational, intelligent adult brain will not be able to override the ‘danger-danger’ siren that is being set off by the amygdala to save them from eating a dodgy mushroom. The amygdala’s mission is to detect danger. Precision decision making is the domain of the frontal cortex but the amygdala engages far faster than the frontal cortex. Plus, when we are making all these early pairings through the process of conditioning, our frontal lobes are not fully developed, which further reinforces the inaccuracy of the conditioning process.

The amygdala has a comparative function that means that it is constantly comparing current reality with all previous experience from the day we were born. So every new incident, event or situation is unconsciously compared to all the data we possess to ascertain if there is any danger. So every new client we meet, or every executive we interview for a position, will be compared to everyone in our amygdala’s vast rolodex of names and events to see if there are any correlations that could spell trouble. And if it finds a match the amygdala will trigger a biological response that will cause us to get nervous, irritated or uncomfortable in some way. If we don’t have a sophisticated understanding and awareness of the emotional signals created by our body, then we can miss these messages or completely misinterpret them. Neither is great. With greater emotional awareness, literacy and self-management, we are better able to avoid poor decisions based on imprecise interpretation of a conditioned response we don’t remember, a response that has absolutely no real bearing on current reality. Conditioning acts like the strings on a puppet and emotion pulls the strings. The trouble is, we think we are pulling the strings based on rational, verifiable data – we’re not. Without conscious intervention, a huge number of our so-called ‘decisions’ are actually subliminal, amygdala-based knee-jerk reactions to long-forgotten events, designed to protect us from things we are scared of or have been trained to be scared of. And it’s all happening below conscious awareness.

Imagine four-year-old William has colic and doesn’t sleep for more than 20 minutes at a time. This goes on for weeks on end and his parents are at the end of their tether. Exhausted and bewildered William’s mother finally loses her temper one evening and screams at William, ‘For God sake go to sleep!’ Of course that makes William scream even louder because he feels threatened – his primary carer is angry and he senses danger to his survival. William’s amygdala then springs into action and goes into situation assessment mode so that it can log all the features and characteristics of the moment for future reference so that he can avoid this type of threat in the future. For example, his amygdala might log that his mum is wearing a yellow shirt, that his favourite blanket is on the floor not in his cot and that the bedside light is on. So William’s amygdala stores upset = yellow shirt = dropped blanket = light. It’s pre-verbal so this isn’t conscious or stored as words, but that’s essentially the message.

Fast forward 50 years and William is a CEO interviewing candidates for a new commercial director position. It’s late afternoon in winter and as William’s secretary shows the last candidate into his office she flicks on the light and a man in a yellow shirt walks in. William immediately feels uncomfortable. What he doesn’t appreciate is that his amygdala has matched ‘light’ and ‘yellow shirt’ and triggered an emotional response even though he has no conscious memory of the colic episode. Assuming William is not emotionally literate he will take an instant dislike to the candidate and dismiss him immediately and simply go through the motions of the interview. Or he will misinterpret his discomfort as something else and then justify and rationalize that initial conditioned response as ‘gut instinct’, ‘intuition’ or ‘business experience’. Either way his ‘decision’ is not based on real data and due interview process of a viable candidate; it is based on an erroneous survival-based conditioned response created when he was four years old and feeling a bit poorly!

As bizarre as this may sound, it is happening all the time – inside and outside business. And the only thing that could rein this conditioning in and facilitate consistently better decision making is emotional awareness. Unfortunately we are so disconnected from our emotions, especially at work, that we’re often not even aware of these shifts in energy. We certainly can’t ascribe an accurate feeling to the emotion, which means that we almost certainly don’t have the cognitive ability to ask ourselves whether the conclusion we’ve just jumped to is actually based on anything solid or not. This is why the emotional line of development is so important for Enlightened Leadership. It allows us to wrestle back power from the hyper-vigilant, neurotically over-protective amygdala and apply some common sense and logic to the situation so that perfectly capable candidates in yellow shirts don’t get thrown out without due consideration.

In addition, it has been demonstrated that what we ‘think’ we are capable of is often nothing more than a conditioned response or habit (Ikai and Steinhaus, 1961). In other words, we need to learn how to tap into our innate emotional signals so we can stop jumping to erroneous conclusions based on long-forgotten events and misperceived threats. And so we can tap into our true potential instead of an outdated idea of that potential. We need to become more ‘response-able’ rather than reactive. We can’t stop the e-motion happening (at least, not without a lot of practice) but we can learn to intervene and manage the response.

According to Michael Gerber of E-Myth fame (Gerber, 1995), the E stood for Entrepreneur and he proposed that in order to be successful entrepreneurs needed to systemize their business. That’s probably true but what I’m suggesting is that the real E-myths that are holding business back are the universal dismissal of E-motion as a business tool and the fact that intellect is viewed as considerably more important – especially in business.

Business is often perceived as the cool, rational pursuit of profit. In the history of commerce it’s been largely a male-dominated sport and even today if you look at the statistics for women in senior roles the percentage is very small (Grant Thornton, 2012). The vast majority of businesses are still run by men. Most cultures still condition their sons to be the strong, show-no-emotion protectors who provide for the family. What we instinctively assume about business is therefore mainly dominated by our outdated and inaccurate assumptions about men. Emotion is seen as a demonstration of weakness preserved for the ‘weaker sex’ and is often cited as the whispered although invalid justification for why women shouldn’t be in business in the first place. Men are rational, socialized from a very early age to dismiss emotion and feeling entirely – or so the story goes.

This is so ingrained into our collective psyche that if we ask a man what he feels, he will tell us what he thinks. If we ask a male CEO how he is feeling after the dismissal of a colleague for example, he will tell us how the decision was necessary and how the business is going to move forward. He often doesn’t even understand the question, and if he does he is so used to ignoring and suppressing his feelings that he often has no lexicon to answer the question! The challenge for men is their lack of emotional awareness.

For women, it’s slightly different because they tend to be more aware of their emotions in the first place. This awareness is facilitated by their direct experience of strong physical and emotional tides on a monthly basis. The challenge for women is therefore not lack of awareness but potentially lack of control over their emotions. Women can sometimes be more easily overwhelmed as the energy bubbles to the surface more readily, and certainly this is a widely perceived ‘female’ issue, especially in business. As a result men and women struggle in this endless dance where a woman’s lack of control reinforces the male belief that emotions are unhelpful and the men’s overt control reinforces the female belief that men lack empathy and have the emotional capacity of a stick insect. The truth however is that it is emotional mismanagement that is unhelpful, not emotions themselves, and that is true for both sexes.

Emotional suppression is every bit as toxic and unhelpful as emotional excess and over expression. Unfortunately this misdiagnosis of emotions – rather than emotional mismanagement – as the problem creates a vicious cycle where men justify their lack of awareness, fearing that if they paid attention to emotions they could become overwhelmed, lose control and make poor decisions. So they dismiss the whole topic of emotions, which then makes women even more irritated, triggering even more upset that further solidifies the unhelpful stereotypes and maintains the endless dance.

This blanket dismissal or ridicule of emotion is also further compounded by the fact that we prize cognition significantly more than emotion. For many centuries it’s been intelligence, creativity and thought that has been valued above all else. Consider the intellectual transformation brought about during the Renaissance between the 14th and the 17th centuries, the Age of Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries, or the New Thought Movement of the early 19th century. Thought has been king for a very long time. In business strategy, analysis, customer insight, like-for-like sales figures, process reengineering and a whole manner of other fields, rational pursuits are highly prized. Relationship dynamics, sensitivity, emotion and feelings are less explored if not taboo.

In the workplace we often hear how a certain individual is ‘highly intelligent’ or ‘super smart’. That’s a compliment. When someone is described as ‘emotional’ however it is never a compliment and such a statement is most often directed toward a female executive. Ironically, if a male executive does occasionally express emotion it is more often regarded in a positive light such as ‘aggressive’ or ‘passionate’.

This supposed difference between men and women is simply not true. Every human being – male or female – has emotion. Everyone has physiology that is in a constant state of flux, and this energy in motion creates signals that are being sent continuously and simultaneously around the body across multiple biological systems. The fundamentals of the physiological reaction to the world are therefore no different between the sexes; the triggers and intensity of emotions and the degree of self-regulation vary by person, but the fact that emotions occur every second of every day is true of men and women. The only thing that is different is the weight of thousands of years of gender-based expectations that can be manifested as unhealthy biases inside and outside business. This in turn has created a mistaken belief that emotions are commercially irrelevant and do not belong in a modern business context.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Why emotions are important in business

In 1776 Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations – a treatise on economics and business that is still used to this day. In it Smith talks about the division of labour. Everyone in a business was to have a particular job and they did only that job. People were rewarded for doing the tasks they were assigned and punished if they didn’t. Simple – and during the Industrial Revolution, very effective. But getting people to do what you want them to do is not just about reward and punishment. In fact social science has conclusively proven that reward and punishment only works for very specific types of tasks – known as algorithmic tasks. These are tasks that follow a set path to a set outcome and as such are often monotonous and boring. For everything else, known as heuristic tasks or those that require creativity, innovation and trial and error to perfect, reward and punishment do not work and can often elicit the very behaviour you are trying to stamp out (Pink, 2009). A hundred years ago most people spent most of their time doing algorithmic tasks; today technology and innovation have replaced many of those jobs and according to McKinsey and Co this type of work will account for only 30 per cent of job growth now and into the future (Johnson, Manyika and Yee, 2005).

Regardless of what we might want to believe, people are people and not machines, so treating them like machines is no longer effective. And people have emotions, so to ask them to leave their emotions at the door is like asking them to stop their heart beating while they are in the office because the noise is a little distracting. Besides, negating emotion in the work place is not commercially smart because it renders employees incapable of making good decisions, unable to work hard, unlock their discretionary effort or feel a sense of fulfilment. Plus, it facilitates terrible customer service. If we are serious about securing a commercial edge over our competitors then we really must understand how central emotions are to human functioning and the development of potential.

It was MIT management professor Douglas McGregor who really started to question this ‘leave emotion at the door’ approach to business back in 1960. Drawing on the work of motivation luminaries such as Harry Harlow and Abraham Maslow, McGregor refuted the notion that people, men included, were basically walking machines that needed to be programmed to do a job and kept in line. McGregor believed that the productivity and performance problems that plague business – then and now – are caused by a fundamental error in our understanding of human behaviour. He described two very different types of management – Theory X and Theory Y (McGregor, 1960). Theory X assumes people are lazy and to make them conform you need a command and control approach. Emotion has no place in Theory X and if anything is considered a show of weakness. Theory Y on the other hand assumes that work is as universal and necessary as rest and play, and when you bring people together toward a shared vision that everyone is emotionally connected to, then truly amazing things are possible. McGregor’s insights, made all the more palatable because he had real leadership experience as well as a Harvard PhD in psychology, did help to shift work practices a little but for the most part Theory X is still the predominant management style in modern business. We still seem reluctant to embrace the very thing that makes us human in the first place – emotions.

I think that the biggest reason we cling on to Theory X in some form or another is because the alternative is terrifying. Theory Y requires that we break down the barriers and start really communicating with each other. It means facing the messy and unpredictable side of humanity and if we don’t even appreciate our own emotions and how we feel on a daily basis, ‘feelings’ can seem like an alien and unfathomable black hole. It’s just too hard! So instead we try to ignore the fact that business is first and foremost a collection of human beings. It’s like owning a Formula One team but refusing to hire mechanics to look under the shiny red exterior!

In her case study at www.coherence-book.com, Orlagh Hunt, one of the best HR directors (HRD) in the FTSE, reflects on her time as Group HRD for RSA and discusses the critical importance of embracing the human element of business – and that means emotion. With a 300-year heritage, RSA is one of the world’s leading multinational insurance groups, employing around 23,000 people, serving 17 million customers in around 140 countries. Talking about her time with RSA, Orlagh said:

In theory we worked together, but our old way of operating had been all about driving individual performance. That was how our performance management and people management processes were set up. But to think bigger you need to have more collaboration and innovation and that requires different ways of working… Individually, for members of the executive team, it was very much about being open. We needed to stop the sense that you have to have all the answers just because you’re in a senior position. That means being open to including more people in decision making… Moving our leadership style on in that way was very important.

And the effort paid off; by looking under the hood of the team dynamic and really seeking to understand human behaviour in a more sophisticated way, RSA achieved significant wins:

We moved to a more human and engaging leadership style that supported the organic growth phase and teed up opportunities for us to think differently about how ambitious our strategy could be… The outcome has been that the organization moved from failing to being well respected on the FTSE. Not only that, but the organization has seen benefits in terms of significant levels of organic growth despite a difficult economic environment, world class levels of employee engagement (as measured by Gallup) and it achieved sixth place in The Sunday Times Best 100 Big Companies to work for scheme in 2012.

Emotions must be understood if the leadership journey is to be successfully navigated. Of course it is possible to be a powerful business figure with low levels of emotional and social intelligence (ESQ). But individuals who become more emotionally and socially intelligent will significantly improve results. Emotional mastery can:

- improve clarity of thought and ability to learn;

- improve the quality of decision making;

- improve relationships at work to avoid ‘leadership by numbers’;

- facilitate effective management of change;

- increase leadership presence;

- improve health and well-being;

- increase enjoyment and quality of life;

- ignite meaning, significance and purpose;

- improve motivation and resilience;

- expand sense of self.

Improve clarity of thought and ability to learn

We’ve all found ourselves in the middle of a heated argument saying something stupid, only to think of the most brilliant comeback five minutes after the other person has stormed out the room. Unfortunately it’s impossible to think of smart comebacks or great ideas when our internal emotional signals are going haywire – even if we look the picture of indifference on the outside. Whether we feel the emotion or not doesn’t alter the fact that the emotion is present. And it’s already impacting our clarity of thought and the outcome.

We will explore this idea in more detail in the next chapter, but ultimately chaotic physiology and turbulent emotions cause the frontal lobes to shut down. So the clear thinking that we believe we are engaged in is actually just the emotional early-warning system of the amygdala, not the neocortex. Emotion is constantly influencing our clarity of thought and ability to learn; the only real question is whether that influence is unconscious and potentially negative or consciously managed and positive.

There are millions of bits of information from the internal and external world that are competing to get into our conscious awareness. Unless you learn emotional mastery and self-management so that you take conscious control of that filtering process, what you become aware of will largely be determined by long-forgotten conditioning and the hyper-vigilant and over-protective amygdala. Plus it takes at least 500 milliseconds longer for the information to reach the frontal cortex and a thought to emerge than it does to activate the emotional early-warning system of the amygdala. That’s why we said something stupid in the argument – our amygdala reacted before our thinking, rational frontal cortex even knew what was going on.

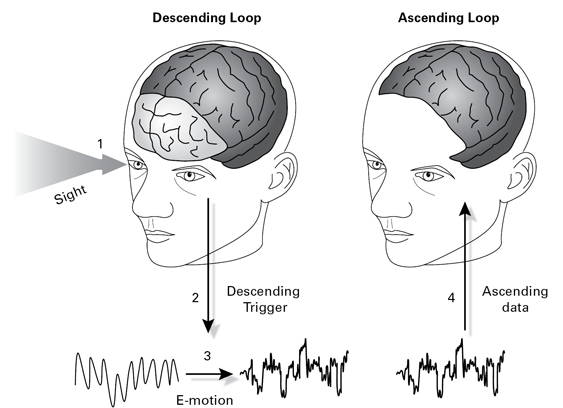

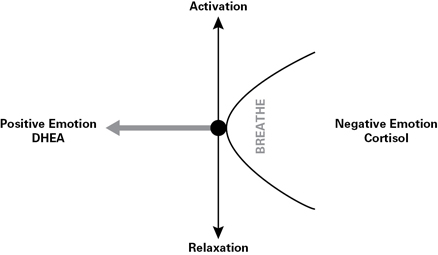

This process is incredibly fast. If the amygdala detects danger, real or perceived, it will send a signal to our heart and cause it to speed up. This is the ‘descending loop’ of the construction of a feeling. The heart rate can jump from 70 to 150 beats per minute – within one beat. This change in the energy of the heart (e-motion) is then sent back into our amygdala, the anterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus and the motor cortex. This is the ‘ascending loop’ of the construction of a feeling (Figure 3.2).

FIGURE 3.2 Construction of a feeling

In that half a second our physiology has already changed; the emotion emerged and whether we were aware of that emotion as a feeling or not it has already initiated a response that the neocortex is not yet even aware of.

This biological phenomenon means that we are all living half a second behind reality, and also explains why feeling dominates thinking and not the other way around. Feeling is faster than thought and sets the context in which thoughts even occur. Thoughts are slower and they are emergent phenomena that do not occur independently of changes in our emotion. The thought wouldn’t have emerged had our physiology and emotion not changed first.

This mechanism can be useful in alerting us to danger, but without greater emotional intelligence our amygdala can become ‘trigger happy’ and that’s not that useful in business. In fact it can be extremely costly. If we are aware of only a tiny fraction of what we could potentially be aware of, it makes sense to develop a much greater awareness of our internal data. By doing so we are able to make better decisions and accurately determine what’s really commercially relevant instead of making knee-jerk emotional reactions that can pollute our thinking and hamper performance.

Learning to induce an appropriate emotional state is also key for optimal learning. In the training and development industry this is called ‘learner readiness’ but it is little more than common sense. If we are spending a fortune on internal training that isn’t working then at least part of the reason is down to emotion. If trainees are in a negative emotional state, if they are hostile or resentful at having to be in the training in the first place or they think the course is a waste of time, then they won’t learn and they certainly won’t implement. When their physiology is chaotic they are generating much higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol. Cortisol is well known to inhibit learning and memory.

As an Enlightened Leader we can help to shift the emotional response of the people around us, which can improve their ability to learn and enhance their performance.

Improve the quality of decision making

All commercial success ultimately depends on the quality of decision making. Most executives, particularly male executives, believe that decisions are a logical process. You analyse the data, determine the best option and make the decision. Unfortunately this is not how decisions are actually made.

In the mid-19th century there was a breakthrough in the neuroscientific understanding of decision making, although this breakthrough wasn’t fully understood until 20 years ago. It all started with Phineas Gage, who was a railway construction foreman in the United States in the 1840s (Damasio, 2000). Rather than weave the railway around a rock formation, it was easier to blast through the rock. Gage, an explosives expert, was employed for that task. The process involved drilling a hole in the rock, half filling it with gunpowder, inserting a fuse and filling the rest of the hole with sand. The sand would then be ‘tamped in’ very carefully with a ‘tamping rod’ to pack the sand and explosive in place, before finally lighting the fuse. Unfortunately, on 13 September 1848 25-year-old Gage suffered a traumatic brain injury. Momentarily distracted, he started tamping before the sand was packed in and a spark from the tamping rod ignited the gunpowder, sending the six-foot-long iron tamping rod straight through his brain to land 80 feet away. Amazingly Gage survived – conscious and talking just a few minutes after the accident (Damasio, 2006). You can see an astonishing picture of him after the accident on the Phineas Gage Wikipedia page.

Antonio Damasio has written extensively on the consequences of Gage’s injury and its implications for decision making. Based on medical records at the time and brain reconstructions, Damasio suggests that the iron pole cut through his brain and disconnected the logic centres located in his frontal cortex from the emotional centres located further back including in his amygdala. Prior to the accident, the railway company that employed Gage considered him to be one of the most capable men in their business. However, after the accident his character changed completely and although he could answer basic logic problems he was unable to make decisions, or he would make decisions and abandon them almost immediately.

Gage’s inability to make effective decisions led neuroscientists to realize that decision making requires emotion. In order to decide anything we have a ‘feeling’ first and then we simply look for rational data to support that initial feeling. So all decisions we ever make are really just feelings justified by logic. Quite simply, we can’t exclude feelings from the decision-making process. Even the most hard-bitten neuroscientist will tell you that the emotional system and logical system are inseparable.