Few people can be unaware of the story about the opera singer who was able to shatter wineglasses simply by attaining a specific note with her voice. The reason why such tricks are possible is that the vocal cords are able to produce sounds that match and, if sustained, exaggerate the inherent vibrational frequency of the glass. This has the effect of causing it to oscillate or shake so violentiy that eventually it disintegrates.

It is a similar story when panes of glass vibrate as a truck, or a low-flying aircraft, is heard to pass by. The sound-waves produced by their engine, or engines, move through the air and, on reaching the pane of glass, synchronise with its inherent vibrational qualities, causing it to resonate in sympathy. Not every aircraft or truck engine will have this effect; only those with engines that match the resonant frequency, or frequency range, of the window, and this can depend on many factors, such as its size, shape, type or position. Just think of the way in which a tuning fork, when tapped and brought up close to another tuning fork of the same length, will induce the latter to hum in sympathy – this is called sympathetic vibration. Bring the same tuning fork up to a second fork with slightly different-sized prongs (and therefore with a different resonant frequency) and the second one will not respond at all.

Sympathetic vibration is completely understood by modern science; indeed, it is this very process that enables ultrasonic drills to cut so easily through quartz. Other minerals do not respond to ultra-sonics in quite the same way and so are much more difficult to drill using this process.

The Ancients would appear to have utilised the concept of sympathetic vibration to create sonic processes little understood by the modern world. We can only speculate on how this might have been achieved, although I think it is safe to assume that it involved establishing the resonant frequency of any object they intended to move. Once this was determined, a sustained sequence of sounds would presumably have been directed towards the object, either by playing musical instruments or by using the human voice. To this base chord it is likely that they would have added a sequence of harmonics – sounds based on proportionate fractions of the original note.

To establish an object’s natural resonance, the Ancients would probably have used either calculations based purely on audible sounds heard by the human ear or a predetermined knowledge of the resonant sound the object might be expected to make if manufactured to a certain size, shape and pattern. This information could then be matched against the chords produced by different instruments until the object’s exact frequency was determined. Provided that the chosen harmonics were pitched so that they did not cancel each other out, this process would have had the effect of creating a wall of sound, a kind of sonic platform, that would have greatly enhanced the oscillations or vibrations achieved within the target object. In turn, this would have caused the air particles around its surface to vibrate in a like manner, creating a kind of cushion effect that might also provide a means to counteract the effects of gravity. All this is, of course, pure speculation and does not explain how the Ancients were able to levitate stone blocks so easily.

IN PERFECT HARMONY

The resonance of an object, or indeed that of a room or building, is defined by a number of quite different factors, such as size, mass, rigidity and symmetry. Together these can greatly affect the quality, tone and availability of sympathetic vibration, something that architects of sacred buildings have been acutely aware of for thousands of years. One of the prime motives in the design of Gothic cathedrals in medieval Europe was to establish a structural resonance in perfect harmony with the human voice. Recent studies in the United Kingdom have indicated that this was also the intention of the Iron Age designers of the mysterious subterranean chambers known as fogous found in Cornwall. These have been determined to resonate sound frequencies that match the pitch produced by male vocal cords.1 The ultimate origin or purpose of this practice is unknown, although the many legends that connect the origins of stone and earthen monuments with music and dance would seem to indicate an original ceremonial function featuring both of these components.2

There seems little doubt that music and sound have played a major part in the design of sacred buildings all over the world, and this has especially been so in Egypt, where a profound understanding of sound acoustics is easily detected. Take, for instance, the King’s Chamber in the Great Pyramid. A voice sounded in here will resonate in a most extraordinary manner, leading to the conclusion that this effect was created with a specific purpose in mind. Such an assumption might help explain why the pyramid builders incorporated ‘Pythagorean’ triangles into the chamber’s overall design. This particular geometric shape, not officially discovered until the age of Pythagoras some 2000 years later, is known to produce the three most important harmonic proportions, which when brought together produce a fundamental note, or keynote, seen in the combination of the notes D, G and E to produce the keynote C.

Why incorporate such fundamental harmonics into a chamber built, according to conventional Egyptologists, merely as a tomb for a deceased Pharaoh? The answer, they would say, is simple – it is all just coincidence, without any form of hidden meaning. In which case we must now move on to another example of perfect harmonics in the Great Pyramid – the lidless, dark granite sarcophagus that sits at one end of the King’s Chamber. Whether or not this huge coffer once held the mummified body of a deceased king, it has long been known to possess acoustic properties of remarkable quality. It was Petrie who first noted this fact during his meticulous survey of the Great Pyramid in 1881. Having already established that the sarcophagus was fashioned using jewel-tipped tubular drills and 2.7-metre-long saws, Petrie made the decision to raise up the coffer in an attempt to establish its exact size. He also wanted to find out whether it might conceal the entrance into a hidden chamber, a suggestion made by some of his contemporaries.

Movement of the sarcophagus required the help of several fellahin who eventually were able to tilt the enormous rectangular piece of granite a full 20 centimetres off the ground. No opening was discovered beneath it, and once its exact measurements had been taken Petrie struck the empty box. It is said to have ‘produced a deep bell-like sound of extraordinary, eerie beauty’.3 As I have already pointed out, the internal volume of the coffer is precisely one half of that defined by its exterior dimensions, demonstrating the great lengths to which its manufacturers must have gone to achieve the best harmonic resonance. Is this all simply coincidence, or is it, as seems far more likely, that the pyramid builders saw an acute relationship between their own world and that of acoustics?

THUMPING AND A HUMMING

If we now leave the Giza plateau and travel south along the course of the Nile to the seemingly never-ending temple complex at Karnak, we find further evidence of the Ancient Egyptians’ profound knowledge of acoustics. Here, among the magnificent ruins, adorned from top to tail in beautifully executed friezes, there are three enormous obelisks made of the finest pink granite extracted from the famous quarries at Aswan, 186 kilometres (116 miles) upriver. Two still stand, one dating to the reign of the Eighteenth-Dynasty king Thutmose I (c. 1528–1510 BC) and the other erected during the reign of his daughter Hatshepsut (c. 1490–1468 BC). A third obelisk, which lies in a horizontal position nearby, was also raised during the reign of this much-celebrated queen. Although only the upper 9 metres of the fallen monolith remain today, it originally weighed a staggering 320 tonnes and, like its neighbour, stood a mighty 29.6 metres in height.4

These colossal obelisks are of a standard size and design for this period of Egyptian history. Their exact purpose is still unclear. They might simply have been commemorative monuments to the Pharaohs in question. On the other hand they may well have served a more functional purpose, as sundials perhaps, used by astronomer-priests to calculate celestial events in the yearly calendar. They might even have been physical representations of the so-called djed-pillar the backbone of the world, which, according to Ancient Egyptian myth, stood on the primeval mound of creation at the beginning of time.5 Whatever their outward function, their curiously offset horizontal dimensions are thought to embody specific geodetic data preserving the precise latitude and longitude of their place of erection.6

It is, however, the broken obelisk of Hatshepsut that is of interest to this debate. Until fairly recently the chances are that, on approaching it, a well-meaning, though possibly costly, Egyptian guide would appear out of nowhere and insist that you repeatedly thump the apex of its perfectly carved and highly polished pyramidion. On carrying out this simple ritual, the whole 70 or so tonnes of obelisk would, with the greatest of ease, start to emit an extremely low drone, almost as if somebody has plugged it into an electrical socket. This curious sound would continue for anything up to 30 seconds before gradually fading away to nothing.7

In spite of it being just a third of its original size, Karnak’s fallen granite obelisk can be made to give up its resonant frequency, like some giant prong of an enormous tuning fork. If these obelisks were purely commemorative monuments, then why bother to incorporate into their design such a profound knowledge of sound acoustics? Chance does not seem to be a factor here. The builders of the Eighteenth Dynasty would appear to have preserved an ancient art that may well have been linked with the concept of sonic technology.

I am not suggesting that the great obelisks of Egypt were transported or raised into position using sonic platforms, for there is ample evidence to demonstrate that more conventional means were used to transport them from the granite quarries of Aswan to their various points of destination. What I am suggesting is that the knowledge of harmonic proportion originated during a much earlier age when it was utilised for more fantastic purposes, such as the movement of enormous building-blocks and the drilling of holes through hard rock. If such speculation should prove to be correct, then the indications are that this ancient wisdom was part of a legacy passed on to dynastic Egypt by the descendants of the Sphinx-building Elder gods, the elite ruling class of predynastic times spoken of so strongly by the likes of pioneering Egyptologists such as Petrie and Emery.

Are we really to believe that the cyclopean stone blocks used in the construction of monuments such as the Great Pyramid and the Valley Temple were transported into position using sound alone? Their individual measurements vary so much that it would now be impossible to answer this question with any degree of certainty. As we have seen, a profound knowledge of sound harmonics does exist in the design of the Great Pyramid, as well as in the Egyptian obelisks, so it is strongly possible that this goes some way to support Mas’ūdi’s claim that sound vibration really was used during the age of the pyramid builders.

In my own opinion, it seems reasonable to suppose that sonic technology was merely an option alongside other, more conventional means of moving and positioning huge stone blocks of the sort incorporated so commonly into the architecture of the Giza plateau. It has always been said that given enough manpower, anything can be achieved, and this is fundamentally correct. As the Egyptian civilisation grew gradually into a huge empire of enormous might and influence, labour would have become far more plentiful. Not only was the Egyptian population increasing, but the many thousands of prisoners of war would have made it that much easier to erect great stone monuments such as the great temple at Karnak. The old ways would have been neglected and finally abandoned, their presence being found less and less in new buildings as the centuries rolled by. In the end, any remaining memory of sound technology would have served a purely symbolic or mythological purpose – the expression perhaps of an inner priesthood that kept alive this ancient wisdom in their initiations, rituals and teachings. Perhaps it was for these reasons alone that the sacred obelisks retained an understanding of harmonic proportion in their overall design.

ACOUSTIC ENTERTAINMENT

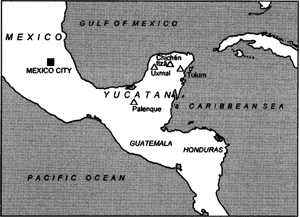

What does this new understanding of the relationship between sound and architecture in Ancient Egypt tell us about the legends of sonic technology in other parts of the world? Did the civilisations remembered as having erected walls and cities using the power of sound once possess a similar knowledge of sympathetic vibration and harmonic proportion? Amphion’s city of Thebes no longer exists, so little can be said in this respect; however, the sound acoustics of the Mayan temples of the Yucatán are singled out as among the strangest in the world. Top of the list of sites noted for its peculiarities in this respect is the huge temple complex of Chichén Itzá. Its stepped pyramid, known as the Castillo, is noted for its similarity to Djoser’s pyramid at Saqqara and for the unique lighting effects incorporated into its design. At the two equinoxes a series of shadow triangles is cast on the northern stairway that ends at the base in serpents’ heads. The triangles undulate with the movement of the sun like a snake ascending at the spring equinox and descending at the autumn equinox.

Turning to the Castillo’s apparent acoustic anomalies, researched extensively by Wayne Van Kirk of the World Forum for Acoustic Ecology,8 we find that if a person stands at the base of the Castillo and shouts, the sound will echo as a shriek that comes from the top of the structure. If someone stands on the top of the pyramid and speaks in a normal voice, he or she can be heard clearly on the ground at a distance of 150 metres away. There are no fast explanations for these acoustic properties, and it does not seem that they were created purely by chance alone.

Near the Castillo is the Great Ball Court, which consists of two temples at each end of a huge field, 160 metres in length and 68.6 metres in width. Other structures stand like terraces set within the east and west perimeter walls. A soft whisper at one end can be heard easily at the other end.9 If you then stand within a circle of stones positioned at a certain spot inside the Great Ball Court, you can have a perfect conversation with a person who stands in a similar circle of stones some 60 metres distance ‘as if they were a few feet away’.10 So popular did the Great Ball Court’s weird acoustics become that, during the 1930s, the archaeologist Sylvanus G. Morley impressed guests on moonlit nights by setting up a phonograph in the North Temple and playing Sibelius, Brahms and Beethoven to a spellbound audience who would sit on supplied cushions within the South Temple over 150 metres away.11 It would seem as if the gods themselves were providing this feast of acoustic entertainment.

Moving away from Chichén Itzá to a Mayan site on the Yucatán coast named Tulum, we find that when the wind is exactly at the right velocity and direction, its temple emits ‘a long-range whistle or howl’. A local guide explained that this curious sound acted as an early warning of ‘incoming hurricanes and big storms’.12 At Palenque, another famous Mayan site, we are told that if three people stand one each on the top of its group of three pyramids a three-way conversation can easily be held.13 Lastly, and perhaps most tellingly, is the knowledge that if a person stands at the base of the pyramid-like Temple of the Magician at Uxmal and claps his or her hands the stone structure at its top produces an inexplicable chirping sound.14 This building, as we have already seen, was said to have been built by a race of dwarfs who could just whistle and stones and logs would rise into the air.

Map of Mexico showing principal Mayan sites featured in this book.

None of these unique acoustic effects appears to be simply coincidence. It seems clear that they were purposely incorporated into the design of the buildings under question, and yet despite this their exact cause remains uncertain. One theory suggests that in the case of the Great Ball Court at Chichén Itzá, the strange sound effects could be caused by ‘the gaps which are part of the surface of the temple’s exterior walls’.15 Yet in all honesty the experts have no idea what produces these unique acoustic properties. As one Mayan scholar named Manuel Cirerol Sansores was to comment in respect of the strange sound effects noted so often at Chichén Itzá’s famous Great Ball Court:

This transmission of sound, as yet unexplained, has been discussed by architects and archaeologists. Most of them used to consider it as fanciful due to the ruined conditions of the structure but, on the contrary, we who have engaged in its reconstruction know well that the sound volume, instead of disappearing, has become stronger and clearer . . . Undoubtedly we must consider this feat of acoustics as another noteworthy achievement of engineering realised millenniums ago by the Maya technicians.16

That, like the Ancient Egyptians, the Maya were able to incorporate such a profound knowledge of sound acoustics and harmonic proportion into their temple complexes hints at an understanding of sonics over and beyond most other ancient cultures. That legends should also surround their earliest ancestors concerning the use of sonics to raise heavy objects into the air suggests that they really were the inheritors of an advanced technology that parallels the one found in Pharaonic Egypt. Where did it come from? Was it inherited from a much earlier culture, or were they able to develop it themselves over hundreds of years of experimentation? We simply do not know.

MULTI-FACETED STONES

Turning to the magnificent ruins of Tiahuanaco, the mysterious pre-Incan city of the Bolivian Altiplano, we find even further evidence of sound acoustics and harmonic proportion playing an apparent role in the design and construction of its enormous stone temples and palaces. These, as we have previously seen, were said to have been built, according to local legend, by the helpers of the tall, white-skinned wisdom-bringer named Ticci Viracocha, who in Aztec tradition was known as Quetzalcoatl, the great ‘feathered serpent’, and in Mayan mythology was Itzamna or Zamna (see Chapter Seventeen).

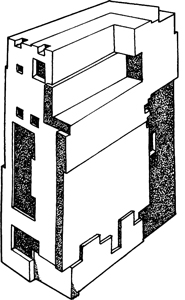

Among the megalithic temples scattered across a wide area at Tiahuanaco is a series of perfectly carved rectilinear monoliths with multi-layered, right-angled sections cut away from their sides. No scholar of pre-Columbian architecture has been able suitably to explain the purpose of these unique stones. It might be suggested that they once acted as support joints for stone or wooden cross-beams and horizontal pillars, but the lack of uniformity in their style and the absence of any surrounding buildings weighs heavily against this theory. On closer examining these monoliths, it seems more plausible that they were fashioned deliberately to define the stone blocks’ harmonic proportions, each section being cut away until the correct resonant frequency was achieved. Whatever the true purpose of these monoliths, their presence might well be linked to the stories told by the Aymara Indians of how the city’s mythical builders were able to move the stone blocks of Tiahuanaco from the local quarries to their place of destination using the sound of a trumpet. If this is so, then it would mean that the antediluvian builder-gods of the Bolivian Altiplano would seem to have possessed an understanding of acoustics similar to that present in Pharaonic Egypt and Mayan Mexico. It is therefore possible that they used these extraordinarily advanced principles to create and sustain sonic platforms on which they could induce temporary weightlessness within heavy stone blocks in order to steer them effortlessly towards their point of destination.

Multi-faceted pillar from Tiahuanaco. Evidence suggests that this stone – and many others like it at the site – was shaped with acoustic principles in mind.

EXPERIMENTS IN SOUND

Even in this knowledge, it was still all just circumstantial evidence and theory without any real proof that sound, or any other connected medium, could be used successfully to raise physical objects off the ground. I needed to further my understanding of the effects of sound on a more practical level, and so decided to organise a series of simple experiments to establish whether or not it was possible to induce temporary weightlessness in objects subjected to a barrage of sound. To this end I enlisted the help and expertise of electrical engineer Rodney Hale, who has a wide experience of working in previously uncharted areas of scientific exploration.

An eight-kilogram piece of quartz and a ten-kilogram piece of bunter sandstone were used in the initial experiments conducted at my home in Leigh-on-Sea, Essex, during the second half of 1996. Long recordings of tonal notes based on the musical chords E, G and D – which when combined together form the keynote C – were directed through loudspeakers at each of the stone blocks in the hope of obtaining a measurable variation in weight. The sounds were used individually, together and one after the after, but all to no avail.

On realising that our wall of sound was having little if any effect on either of the blocks, we used different tonal notes to reproduce their individual harmonics in the hope that this would heighten any sympathetic vibration taking place within the rock’s crystalline structure. When this proved to be too difficult, we turned our attentions to what might have seemed like a soft option – a Tibetan singing bowl! These beautiful vessels are usually made of polished brass (although some of the older ones are made of three metals beaten together) and vary in size from several centimetres upwards. When a wooden baton is rubbed around their outer rim, their unique shape allows them to produce a sustained note.

I felt sure that if we could reproduce the principal note of the singing bowl (which is one and the same as its main resonant frequency), and then build this up with its corresponding harmonics, we stood a better chance of producing a measurable weight loss. This, of course, was the intention, and even though we found a way to sample and then instantaneously feed back the singing bowl’s inherent tones through a loudspeaker positioned nearby, only a very minor weight change was recorded, and even this result was open to question.

Despite the poor success of our experiments in sound, I refused to get downhearted and vowed to continue selling sonics as a forgotten technology of immense importance to our understanding of the past. Even so, I came to realise that I needed more substantial evidence to prove the former existence of this lost science among ancient cultures. At first this had seemed most unlikely, but then somebody mentioned the name John Ernst Worrell Keely . . .