And the Lord God planted a garden eastward, in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed. And out of the ground made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food; the tree of life also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of knowledge of good and evil. And a river went out of Eden to water the garden; and from thence it was parted, and became four heads.1

This is how the Bible introduces the concept of Eden in the book of Genesis. Although most biblical scholars consider this place to have been purely mythical in origin, there is every reason to believe that in ancient times Eden was a geographical locality in its own right. In the book of Ezekiel Eden is mentioned alongside ‘Haran [Harran] and Canneh’ and ‘Assur [Assyria] and Chilmad’ as ‘the traffickers of Sheba’,2 whom the author says dealt in riches such as spices, gold, precious stones and ‘choice wares, in wrappings of blue and broidered work, and in chests of rich apparel, bound with cords and made of cedar’.3

Exactly where Eden was located can be determined from the fact that four individual rivers took their source from its central region and flowed out to four separate countries, delineated, very approximately, by the cardinal points. In much later times Eden’s basic geography was expanded to place the ‘garden’ of Eden in the centre of a world watered by the four rivers of paradise, a concept also found among the rich mythology of Akkad, the Semitic-speaking kingdom that rose to prominence in northern Iraq during the second half of the third millennium BC.4

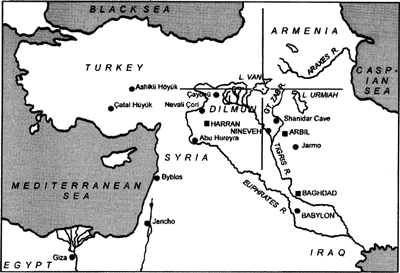

The first of these rivers is cited as the Perath (Pirat in Arabic and Turkish), known today as the Euphrates, which rises as a series of tributaries in the mountains west and north-west of Lake Van and flows out into Turkey before curving around to flow through northern Syria. It then enters Iraq and heads south-eastwards to finally empty into the Persian Gulf.

The second river cited is the Hiddekel, known since Greek times as the Tigris. This also emerges from a series of tributaries, these ones located south-west of Lake Van. They converge to form a fast-flowing river that snakes its way down through the foothills of the eastern Taurus mountains before entering the plains of northern Iraq. It then runs in a south-easterly direction, east of and roughly parallel to the Euphrates, until it too finally empties into the Persian Gulf – the land between them being known as the Fertile Crescent.

The third river is given as the Gihon, which has long been connected in Armenian tradition with the Arak, or Araxes (Arabic Gaihun).5 This rises to the north-east of Lake Van and flows in an easterly direction, through the kingdom of Armenia, the ancient land of Cush,6 into the Caspian Sea.

The fourth and final river, the Pishon, is more difficult to determine. Some scholars have seen fit to associate it with the Uizhun,7 which rises south of Lake Urmiah in western Iran and, like the Arak, flows eastwards to empty into the Caspian Sea. It is equally likely, however, that the Pishon was the Greater Zab river, which rises south-east of Lake Van and becomes a mighty watercourse that flows through Iraqi Kurdistan before joining the Tigris close to the ancient Assyrian capital of Nineveh in northern Iraq. Indeed, so strongly did the local Nestorians, or Assyrian Church, believe that the Greater Zab was the River Pishon that, as late as the early twentieth century, its Patriarch would often sign off his official letters ‘from my cell on the River of the Garden of Eden’!8

It can thus be determined that each of the rivers of paradise flows out from one of the four quarters of Eden, with the central focus being the mighty Lake Van. This is a huge inland sea some 96 kilometres (60 miles) in length and around 56 kilometres (35 miles) wide, which is today situated on the borders between Turkish Kurdistan and the former Soviet Republic of Armenia. Confirmation that Lake Van was the central focus of the land of Eden comes from an Armenian legend, which asserts that its ‘garden’, where Adam and Eve were raised, is now at the bottom of its depths, where it has lain since it was submerged at the time of the Great Flood.9

The Akkadians and earlier Sumerians, who held together southern Iraq with a series of city-states during the third millennium BC, possessed their own rendition of the Eden story. In the mythologies of both cultures the paradisical realm, where gods, human beings and animals lived together in peace and harmony, was known as Dilmun. Here the water-god Enki, the great civiliser, was placed with his wife, an act that initiated ‘a sinless age of complete happiness’. Dilmun was said to have been a pure, clean and ‘bright’ ‘abode of the immortals’ where death, disease and sorrow were unknown and mortals were given ‘life like a god’.10 This story seems to echo, and yet also contradict, the Genesis story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Here, after being tempted by the serpent to eat of the fruit of the ‘tree of the knowledge of good and evil’, humanity’s First Parents are expelled lest they also eat of the fruit of the ‘tree of life’ and ‘live for ever’, in other words become immortal like gods.11

Although scholars present sound evidence to demonstrate that Dilmun was the name given to the island of Bahrain in the Persian Gulf, there is also good reason to show that much earlier it was a geographical realm located in the mountains above what is today northern Iraq. For example, there is one reference to ‘the mountain of Dilmun, the place where the sun rises’.12 Since there is no ‘mountain’ in Bahrain, and in no way can this island be described as lying in the direction of the rising sun in respect to Iraq, it seems certain that there were two Dilmuns. Confirmation that the mythical location of this name was somewhere in the mountains of Kurdistan comes from the fact that the ‘tabooed’ Dilmun was referred to in ancient texts as the ‘land of cedars’.13 Noted Kurdish historian Mehrdad Izady has shown conclusively that the ‘land of cedars’, which was also seen as the abode of the gods, was placed by the ancient Akkadians and Sumerians among the mountains of the Upper Zagros, which stretched from the borders between Iraq and Iran to the very banks of Lake Van, and even further west into the eastern Taurus range.14

Mehrdad Izady has traced the origins of the mythical Dilmun, which has much in common with the biblical concept of Eden. His scholarly research associates the original Dilmun with a tribal region, located south-west of Lake Van in eastern Anatolia, known as Dilamân, or Daylamân, where the so-called Dimila, or Zâzâ, Kurds made their home.15 Ancient Church records found at Arbil (ancient Arbela) in Iraqi Kurdistan cite this same geographical region as the land of Dilamân. They assert that Beth Dailȏmâye, the ‘land of the Daylamites’, was to be found ‘north of Sanjâr’, in other words among the foothills of the eastern Taurus range, between the Upper Euphrates and the tributaries of the Tigris.16 Izady found confirmation of these assertions in ‘The Zoroastrian holy book, Bundahishn, [which] places Dilamân . . . at the headwaters of the Tigris [author’s italics]’,17 the very region in which the early neolithic peoples developed a high level of culture between 9500 and 5000 BC. It seemed no coincidence, then, that this same region was also synonymous with the biblical land of Eden.

THE ROAD TO EDEN

This, then, was the cradle of civilisation, the gateway to Eden, according to the most ancient traditions of the Hebrews, the Akkadians and the Sumerians, and it was through this very region that we would now have to travel on our journey to the district of Hilvan in the province of Sanli Urfa. North-east of here the snow-capped heights of the eastern Taurus mountains pierce the sky and enter the realms of heaven, while towards the south-east is the little-used road to Iraq. It was along this route that in April 1997 the Turks launched the latest of their so-called spring offensives against soldiers of the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK), who inhabit strongholds deep within Iraqi Kurdistan. Over 50,000 troops, 250 tanks, massive air support and a battery of heavy artillery were dispatched into Iraq to track down just 4000 freedom fighters.18

Map of the Near East showing the four rivers of paradise and the four-fold division of the biblical land of Eden. The site of Dilmun, the mythical domain of Mesopotamian tradition, is also marked.

Our destination is the edge of the modern Ataturk reservoir, west of the town of Hilvan, created as recently as 1992, when the waters of the Upper Euphrates were dammed to create hydroelectric power for Turkey. Many such dams have been built at various places along both the Euphrates and the Tigris, and every one has succeeded in flooding important archaeological sites which are now lost for ever. The greatest loss by far is Nevali Çori (pronounced chor-ree), a site of immense archaeological significance dating back to the stage of human development known as pre-pottery neolithic B (PPNB), which in eastern Anatolia took place roughly between 8800 BC and 7600 BC.19

THE MONOLITH

I first came across Nevali Çori by chance during the autumn of 1996 when I received an informative letter from a correspondent named Mark Burkinshaw. Attached to it were various photocopies, one showing an enormous sculptured monolith standing in the middle of a sunken temple, with walls composed of packed dry stone interspersed by a series of upright pillars.20 I thought at first that I was looking at one of the carved standing stones at Tiahuanaco in Bolivia (see below). To me everything about the picture said South America. It was not until I looked more closely at the accompanying text that I realised I was looking at a site in eastern Anatolia.

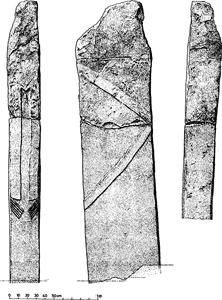

Not only were the sides of the great monolith seen in the picture precisely rectangular, but the whole thing appeared to be set into a perfectly smooth floor, which I later found was composed of a lime-based mortar known as ‘terrazzo’, something quite unique to neolithic sites in this region. Strangest of all were the extraordinary carvings on the two-metre-high erect pillar, which had quite obviously lost its uppermost section. In low relief on its two longest faces were extended arms, bent upwards so that they formed a horizontal V-shape. These terminated on the front, narrow face of the monolith in stylised hands, each with five fingers of equal length – a peculiar sight that gave the immediate impression of flippers, like those of a sea mammal such as a seal, a whale or a dolphin. Above the ‘hands’ were two long rectangular strips that ran from beyond the visible break at the top of the stone to about half-way down its length, giving the impression of extremely long hair hanging over the shoulders of a human form that had lost its head.

Most important of all was the age of this extraordinary monolithic temple. The accompanying text, taken from the book Anatolia: Cauldron of Cultures, published by Time-Life in 1995, spoke of Nevali Qori as a ‘time-machine’ over 10,000 years old! If this were correct, then it had been constructed in around 8000 BC, 5000 years before the emergence of civilisation in ancient Mesopotamia. Could this be true – a culture on the Upper Euphrates of eastern Anatolia, the unquestionable cradle of civilisation, sophisticated enough to produce carved stone pillars so beautiful that they were more in keeping with the megalithic art of Malta or Western Europe, executed many thousands of years later?

To say that the picture of Nevali Çori’s cult building fascinated me is an understatement. I could not stop staring at this compelling image which so perfectly captured the strange ambience of the location. In my opinion, there was a level of sophistication here comparable with the monuments left behind by Egypt’s Elder culture. As I was quickly to discover, even greater surprises awaited me at Nevali Çori.

HAUPTMANN’S DISCOVERY

The setdement itself was first identified during a systematic survey of occupational mounds in the Kantara valley by archaeologist Hans Georg Gebel in 1980.21 At the time he was working on excavations at another site some nine kilometres (five and a half miles) away, so was able to do litde more than report the existence of a previously unknown occupational terrace approximately ninety by forty metres in size, some three kilometres (two miles) from the southern bank of the Euphrates and east of the village of Kantara Çayi (37° 35’ N, 38° 39’ E). Three years later, in 1983, Harald Hauptmann of the University of Heidelberg began the first of several seasons of excavation at Nevali Çori, which takes its name from the surrounding terrace. He returned in 1985 and again during various subsequent seasons. He was last at Nevali Çori in 1991, when the recent completion of the Ataturk dam turned the excavations into a salvage operation to preserve whatever he could from the site. Shortly afterwards, the rising waters of the Euphrates lapped at the edge of the occupational terrace, and very quickly Nevali Çori was tens of metres beneath the Ataturk reservoir. Mercifully, the aforementioned monolith was taken down and transferred to nearby Urfa museum, where it has now been re-erected and placed on display.

What is abundantly clear from Hauptmann’s excavations at Nevali Çori is that from the very earliest occupation of the site which began, according to carbon-14 dating, in around 8400 BC,22 whoever settled here already understood the basic principles of agriculture. Cereals were cultivated and animals domesticated at the very earliest stages of its development. From then on the site was occupied at various times right down to the middle of the sixth millennium BC. Yet despite this extremely long occupation, it is Nevali Çori’s earliest phases, during the pre-pottery neolithic period, that are of special interest to the archaeological world.23

Why exactly Nevali Çori was built where it was is unclear today. There were obviously agricultural considerations involved in the decision, although it is clear that this was no simple farming community. Of the 22 dwellings uncovered, only one appears to have been used for domestic accommodation.24 Many of the site’s rectangular-shaped, grid-planned buildings were used for storage purposes alone. One seems to have acted as a workshop for the making of flint implements, while others bore evidence of cultic use in the form of buried skulls25 (see Chapter Seventeen).

Nevali Çori’s primary function would appear to have been as a religious centre, focused around a rectangular stone structure which Hauptmann named the ‘cult building’. All that remained of its earliest building phase was a piece of wall just four metres long. However, several superb sculptures from this period of occupation were preserved by the inhabitants and later incorporated into the subsequent buildings constructed on the same site.26 The next cult house, known as Building II, was built some time around 8100 BC, with its rear end partially set into the rock-face, giving the whole thing a cave-like feel.27 Inside an earthen bank, four walls were constructed of dry stone which rose to a height of 2.8 metres and were as much as half a metre thick.28

Hauptmann noted that the walls of Building II had originally been covered with a limestone mortar, and here and there traces remained of a grey-white plaster that bore evidence of black and red paint, showing that the walls had once been decorated with murals, presumably of a religious or symbolic nature.29

TEMPLES AND BIRDS

As already noted, Nevali Çori’s cult building possessed a hard terrazzo floor, which must have given it the appearance of a building thousands of years ahead of its time. Into the walls themselves were positioned 13 upright stone pillars located at regular intervals. Each one was originally capped with a T-shaped capital, a fact that led Hauptmann to conclude that they had acted purely as supports for a roof.30 Flanking the steps that formed the entrance down into the south-western quarter of the building were two huge standing stones, while in the wall on the opposite side Hauptmann found a niche for a cult statue. Most important were the various stone statues found at this level. One was a broken limestone sculpture of a bird found Vailed up’ in Building II, implying that it was in secondary use and had almost certainly come from an earlier phase of construction, plausibly that of Building I. In my opinion, it has a clear snake-like head that resembles the stylised features of the Aztec god Quetzalcoad, the feathered serpent. Its beak is broken, but despite this its large eyes, rounded breast and stylised wings are so beautifully executed that this statue would not look out of place in a modern art gallery.31

The third and final phase of Nevali Çori’s cult house, Building III, seems to have been constructed in around 8000 BC. A bench-like platform, topped with enormous stone slabs, was added to three out of four of the interior walls (the exception being the south-western section within which the stepped entrance was located), considerably reducing the size of the terrazzo floor.32 Twelve slim pillars – carved on their widest faces with arms, bent and hunched at the elbows, that ended on their front narrow face with five-fingered hands – replaced the thirteen standing stones of the second phase.33 Matching these ‘support’ pillars, as Hauptmann refers to them, were two (not one, as I had first presumed) three-metre-tall rectilinear monoliths on which were also carved anthropomorphic forms in low relief.34 These formed an enormous gateway and stood one each side of the centre of the building, their front narrow faces directed towards the south-west.

It was the remaining portion of one of these two monoliths that had so fascinated me in the picture included in the Time-Life publication Anatolia: Cauldron of Cultures. The weathered apex of this particular stone was found by Hauptmann lying face down at a higher level, indicating that, unlike its lower section, it had been exposed to the elements for some considerable time, perhaps even thousands of years. Curiously, the remaining monolith had been inserted just five centimetres into the terrazzo floor, which makes very little sense whatsoever. If we recall that this slim carved pillar was originally three metres in height, then it does not take a genius to work out that a depth of just five centimetres would have made it so unstable that someone merely leaning on it would have pushed it over. Hauptmann believes the monoliths were capped with lintel stones and were simply decorative roof supports without any obvious mystical significance. As we shall see in Chapters Eighteen and Nineteen, it seems more likely that, in the minds of the priesthood at Nevali Çori, they served a very important religious function.

Side-plan of the remaining monolith at Nevali Çori, eastern Turkey, courtesy of Harald Hauptmann.

Also found in Building III was a carved clean-shaven head, 37 centimetres in height and shaped like an egg! Although the face is missing, it still bears carefully executed ears and, most extraordinary of all, a long single ‘plait’ or pony-tail that flows down from the crown to the neck and must also represent a curling snake. This astonishing piece of sculpture is unlike anything else that has been found at any other neolithic site in the Old World. It was positioned in the north-east wall, facing south-west, and appears to have been taken from a full-sized statue belonging either to Building I or Building II.35 Hauptmann believes that this skull-like form represents a ‘heavenly celestial being’,36 although in my opinion it represents either an ancestor spirit or a member of a priestly caste. If this is correct, then it might well imply that members of the community sported bald heads with pony-tails. Its distinctive egg shape and curling snake device also appear significant, since both the egg and the serpent were universal symbols of fertility, wisdom and first creation.

In addition to the shaven head, Building III also produced a 23-centimetre-high limestone statuette of a bird-man with an extremely elongated head, almost the shape of a hammer. On its back were large closed wings and the stumps of arms, confirming that it is a human dressed as a bird.37 It was found face down in a recess within the wall, and once again it seems to have been preserved from an earlier building phase.

The subsequent levels of occupation are not so interesting to our debate. They have, however, produced various curious statues that could conceivably have been purloined from the first three levels, c. 8400–7600 BC. These include a composite figure that shows ‘two female figures crouching back to back surmounted by a bird’,38 as well as a mysterious female head marked with hatching to represent feathers.39 This seems to have once formed part of a kind of totem pole composed of different carved forms, more in keeping with North America than eastern Anatolia.

HUMAN SACRIFICE

Something a little more disturbing found to be present at Nevali Çori is the clear evidence of human sacrifice. In one of the buildings, designated House 21, Hauptmann found a female burial with flint tips still embedded in the skeleton’s neck and upper jaws, as if the woman had been repeatedly struck with stone projectiles. Hauptmann admitted that the evidence pointed towards the deliberate killing of the individual; moreover, that the house in question could well have been a ‘sacrificial building’ used specifically for this purpose.40 This is obviously a chilling prospect, especially as we have accredited the incoming wisdom-bringers of the early neolithic peoples with a high level of sophistication and technological know-how.

It would be easy to dismiss the discovery of a sacrificial victim at Nevali Çori as an isolated incident. Unfortunately, however, there is firm evidence of an even more vicious sacrificial cult at Çayonii, just 100 kilometres (60 miles) away to the north-east. Here we find a large number of rectangular stone buildings with grid-plan foundations, like those found at Nevali Çori, as well as other buildings with special functions. One, for instance, has a terrazzo floor, while another – the so-called Flagstone Building -has a floor made entirely from large polished flagstones into which were set megalithic stones (further standing stones were set up in rows nearby),41 giving it an appearance not unlike the interior design of Giza’s Valley Temple.

It is, however, Çayönü’s so-called Skull Building that is of the greatest interest. This stone structure – which is 7.9 by 7 metres in size and has a round apse at one end that gives it the uncanny appearance of a ruined eleventh-century Norman church – possesses very dark secrets indeed. Here, in two small antechambers, archaeologists unearthed some 70 skulls, all of which had been slightly charred,42 while overall excavations in the Skull Building revealed the bones of no fewer than 295 individuals.43 In all likelihood they featured in some kind of localised ancestor worship, although no one can be certain.

More difficult to explain was the unexpected discovery at Çayönü of a large chamber that was found to contain an enormous one-tonne cut and polished stone block, which almost certainly acted as an offering table. Nearby, excavators found a large flint knife, which would eventually lead them to a macabre realisation. Microscopic analysis of the altar stone’s smooth surface revealed a high residue of blood that was found to come from aurochs, sheep and human beings 44 There can be litde doubt what this implies. The Skull Building was not only used for strange ancestral rites but also human sacrifice,45 an element of their society never dwelled on by the archaeological world. It would seem that although the neolithic peoples of Nevali Çori and Çayönü lived extraordinarily advanced lifestyles, comparable with a world that existed on the plains of Mesopotamia thousands of years later, the ruling priesthood led a somewhat amoral lifestyle more in keeping with the civilisations of Meso-America, c. AD 1000, than with the earliest communities of eastern Anatolia, c. 8000 BC.

I can recall when I first set eyes on the picture of the towering monolith in the centre of the cult building at Nevali Çori. Despite its stark simplicity, the structure exuded a feeling of absolute dread. There seemed to be some kind of subtle relationship between this monument and the compelling art of South America, in particular that of the Chavin culture of Peru and the Tiahuanacan culture of the Bolivian Altiplano. Here, in Tiahuanaco, thought to have been built somewhere between 15,000 and 10,000 BC,46 we find mega-lithic temples closely resembling the one at Nevali Çori. As at Çayönü, these were accompanied by rows of standing stones, as well as carved stone pillars of unusual quality and design.

One carved monolith, known locally as El Fraile (the Friar), stood in the south-west corner of the Temple of the Sun in a section of the ruins known as the Kalasasaya,47 the enclosure walls of which greatly resemble those of Nevali Çori. Chiselled from a solid block of red sandstone, this two-metre-tall figure has an anthropomorphic head and low-relief arms that hug its sides and end on the front face of the pillar in hands that clutch strange objects. In the right hand is what appears to be a wavy-line blade, like an Indonesian kris, while in its left hand is something akin to a vase (perhaps a locally made keru).48 More peculiarly, from the waist downwards El Fraile sports a garment meant to represent fish scales, each one individually carved into a tiny fish head.49 Adding to the effect is a waistband decorated ‘with stilized crustaceans’, identified as a type of crab known as hyalela, found in nearby Lake Titicaca.50 There seems little question that this monument represents some kind of fish-man, a connection made all the more poignant by the existence of archaic local folk-tales recorded by archaeologist Arthur Posnansky which spoke of ‘gods of the lake with fish tails, called “Chullua” and “Umantua” ’ 51

Somehow there appeared to be some kind of subde relationship between South America’s carved statues, such as Tiahuanaco’s El Fmile, and the remaining monolith at Nevali Çori. What’s more, the link seemed both cultural and aquatic in nature. Other examples of sculpted art from Nevali Çori also seem to possess pre-Columbian influences. But how could this be so? Nevali Çori lay on a completely different continent, many thousands of miles away from the Americas.

It was a problem without any obvious answers. For the moment it seemed more important to establish who exactly the prime movers were at sites such as Nevali Çori and Çayönü. I needed to know who built Nevali Çori’s cult temple with its finely carved monoliths. Who officiated at its ceremonies and rites, which would seem to have included human sacrifice? Who was behind the sudden emergence of the extraordinary technology found in association with the earliest neolithic sites of eastern Anatolia, and how might any of this link back to the Egyptian Elder culture?