While this book principally focuses on Gaza’s rich and varied everyday home cooking, there are times that call for festive and often lavish meat-based dishes. This chapter brings together these classic meals for special occasions, as well as an array of street and restaurant foods such as roast chicken and kebabs.

Kebab Mashwi • Grilled Kufta Kebab

Jaj Mashwi Bil Furun • Oven-Roasted Chicken

Jaj Mashwi El Fahem • Charcoal-Grilled Chicken

Sayniyit Jaj Bil Batata Wil Bandora • Baked Chicken with Tomatoes and Potatoes

Jaj Bil Filfil Wil Lamoon • Baked Chicken with Lemon and Chiles

Kufta al Ghaz • Stovetop Kufta

Kufta bi Saniya • Pan-Baked Kufta

Tabkeeh Laban Bil Mozat • Lamb Shank Yogurt Stew

Fatta Bil Aranib/Jaj • Buttery Rice and Griddle Bread with Chicken or Rabbit

Qidra • Spiced Rice with Lamb, Chickpeas, and Garlic

Maftool • Palestinian Couscous

Musaqa’a • Eggplant, Tomato, and Beef Timbale

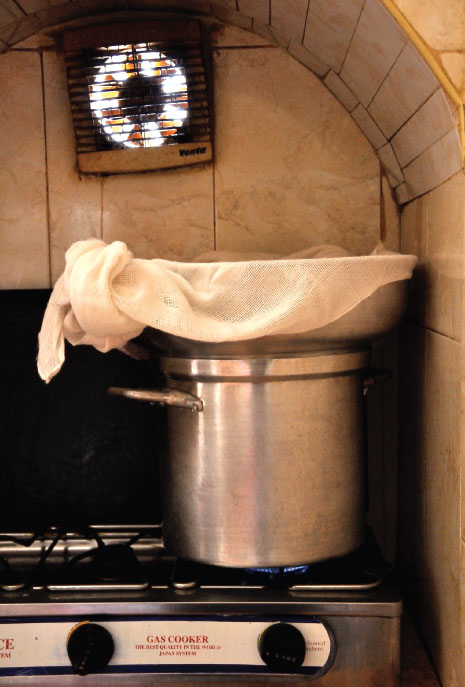

Ijrishit Bir el Sabi’ • Bir el Sabi’ Lamb and Wheat Stew

Fattit Ajir • Roasted Baby Watermelon and Vegetables Fatta

Serves 4–6

2 pounds (1 kilogram) ground beef, with some fat for taste, or 1½ pounds (750 grams) ground beef with ½ pound (250 grams) ground veal

1½ teaspoons ground cardamom

2½ teaspoons ground allspice

2 teaspoons salt

1 teaspoon black pepper

1 ounce (30 grams) lamb tail fat (optional)

1 packed cup (25 grams) parsley, chopped

2–3 hot green chile peppers

4–5 cloves garlic

1 medium onion, quartered

Place the ground meat in a large bowl. Add the spices. Run the lamb fat, parsley, chiles, garlic, and onion together through a meat grinder or pulse them gently, adding one ingredient at a time, in a food processor, beginning with the lamb fat and ending with the onions. Combine with the ground meat.

With slightly damp hands, mold a small quantity of the meat mixture around skewers, forming elongated, thin kebabs. If you are using wooden skewers, soak them in water first.

To grill: Prepare the coals, forming one large mound and one shorter one, and wait until the fire dies down and the coals are grey. Sear the kebab skewers on high heat for about 2 minutes, then transfer away from the direct heat of the coals.

Fan the flames occasionally to keep them hot. The kebabs should only cook for 6 to 8 minutes or they will dry out. You may also wish to grill separate skewers of small onions and tomatoes to serve alongside the kebabs.

Serve the kebabs with assorted pickles, Hummus Bil T’heena (page 85), Imtabbal Bitinjan (page 84), minced green salad, and Khubz Kmaj (page 100).

Few things are more enticing than the smell of kebab grilling over hot coals, luring passersby into sidewalk restaurants for a quick meal. This recipe is from Salih Atiya al-Shawa, one of Gaza City’s most well-known kebabjis. Al-Shawa says clients sometimes request that a little premium lamb tail fat be ground into the mixture, making the meat juicier, or else extra cardamom or garlic. For a small extra price, of course! If you can, try grinding the ingredients yourself at home or ask your butcher to do it for you. Use flavorful cuts of beef.

Serves 4–6

One 3 pound (1½ kilogram) chicken

1 tablespoon ground sumac

1½ teaspoons salt

½ teaspoon cardamom

2 teaspoons red pepper flakes

1 onion, grated

1 very ripe tomato, crushed

1 teaspoon tomato paste

¼ cup (60 milliliters) fresh lemon juice

¼ cup (60 milliliters) olive oil

2 tomatoes, quartered

1 potato, cut into 1 inch slices

6 cloves garlic, whole

1 large onion, quartered

2 carrots, cut into 1 inch pieces

1 summer squash, sliced

Wash the chicken well, as instructed on page 26 in the section “Common Sense,” and set it aside in a colander to drain off the bloody juices.

Rub the sumac, salt, cardamom, and pepper flakes under and over the skin of the chicken, making sure to reach inside to the thighs. Combine the onion, tomato, tomato paste, lemon juice, and olive oil and mix well. Rub this mixture all over as you did with the spices, and inside the body cavity. Set the chicken aside for at least 2 hours.

Preheat your oven to 400°F (200°C).

Set the chicken in a roasting pan with the whole garlic cloves and vegetables, then place it in the preheated oven. The roasting time will depend on the size of the chicken, but it should take about 1 hour. The chicken is done when piercing between the body and the thigh releases clear (not pink or cloudy) juice.

Whether left whole or cut into parts, spicy roast chicken is a perennial favorite in Gaza. This is an adaptation of a recipe given to us by Lulu from the Olive Roots Cooperative in Zeitun.

Serves 4–5

One 3 pound (1½ kilogram) chicken

1½ teaspoons salt

2 green chile peppers, chopped

5 cloves garlic

1 teaspoon black pepper

3 tablespoons sumac

2 tablespoons vinegar

1 tablespoon ground red pepper (cayenne or similar)

¼ cup (59 milliliters) olive oil

Wash the chicken well, as instructed in “Common Sense” (page 26). Set the chicken aside in a colander to let the bloody juices drain.

Butterfly the chicken: Start by using a pair of kitchen shears or a sharp butcher’s knife and cut out the back. Spread the chicken out and press it flat.

In a mortar and pestle, crush the garlic and chile peppers along with ½ teaspoon of salt. Mix this together with the pepper, sumac, vinegar, ground red pepper, olive oil, and remaining salt. Slather the chicken with this marinade, place it in a large bowl, and refrigerate it, covered, for several hours or overnight.

Lay the chicken out flat in a grill cage and lock it. (If you don’t have a grill cage, it’s worth the investment, though you can also make this on a simple grill.) Meanwhile, prepare the coals: Pile them into a mound on one side of the grill. When the coals are red and coated in grey ash, you are ready to begin.

First, place the cage on the cooler side of the grill, away from the mound of coals, skin side up. Close the grill cover and cook the chicken for about 50 minutes. Test the doneness of the chicken by piercing the thigh with a skewer: If the juice that runs out is pink, it needs more time.

Once it is cooked through, transfer the chicken cage to the part of the grill directly over the mound of coals and flip so it is skin side down. Sear the chicken over direct heat until the skin is charred and crispy.

Serve with Khubz Saj (page 100), assorted pickles, Hummus Bil T’heena (page 85), and Imtabbal Bitinjan (page 84).

We had of lot of requests from nostalgic visitors to Gaza for this particularly delicious grilled, butterflied whole chicken, often served by small restaurants in the business districts of the city. It can also be made with chicken parts with excellent results.

Serves 5–6

One 3 pound (1½ kilogram) chicken, skinned and cut into parts

1 teaspoon salt, plus more for cleaning the chicken

½ teaspoon black pepper

1½ teaspoons allspice

½ teaspoon ground cardamom

2 medium potatoes, peeled and sliced

1 medium onion, sliced

2 tomatoes, thickly sliced

10 whole garlic cloves

2–3 green chile peppers, cut into thin strips

Olive oil

½ cup (120 milliliters) water, tomato sauce, or liquefied strained tomatoes

Preheat your oven to 375°F (190°C).

Clean the chicken well, bathing it in a bowl of cold water mixed with a fistful of flour. Rub the chicken pieces with a spent lemon rind or some vinegar and a little coarse salt, removing any veins and extra fat. Rinse the chicken and set it aside in a colander for about 10 minutes to let the bloody juices drain.

Next, rub the chicken pieces with the salt, pepper, and remaining spices, along with ½ cup (120 milliliters) of olive oil. Drizzle a little of the oil on the bottom of a baking pan, then layer the potatoes and onions on top. Transfer the chicken pieces to the pan, arranging them on top of the potatoes, followed by the tomatoes and the peppers. Scatter the garlic cloves all over.

Add ½ cup of water and the tomato sauce, or tomato water, to the pan. Cover the pan with aluminum foil and bake for approximately 40 minutes. Uncover the pan and set the oven to broil, then return it to the oven for about 5 minutes to brown. Serve with Hummus Bil T’heena (page 85), Khubz Kmaj (page 100), salad, and an assortment of pickles.

A simple but sublime preparation for baked chicken, the perfect comfort food.

Serves 5–6

One 3 pound (1½ kilogram) chicken, cut into parts

1 medium onion, julienned

1 teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon black pepper

3 green chile peppers, sliced

5 garlic cloves, crushed

Juice of two lemons

3 baking potatoes, evenly sliced

Parsley and lemon slices, for garnish

Preheat your oven to 375°F (190°C).

In a large bowl, wash your chicken with water and a fistful of flour, then rub it with a spent lemon rind or a little vinegar and some coarse salt. Rinse it clean and set it aside in a strainer for 10 minutes to let the bloody juices drain.

Season the chicken with salt and pepper. In a large skillet, warm a few glugs of olive oil (about ⅓ cup, or 80 milliliters) and pan-fry the chicken pieces, a few at a time so as not to overcrowd the pan, along with the onion until they are browned all over. Add approximately 2 cups (240 milliliters) of water to the pan. Turn the heat down to low and simmer it for about 15 minutes, skimming any scum or grease that rises to the surface.

Meanwhile, fry or oven-roast your potato slices (simply slather in olive oil and bake) and season them with salt. Set aside.

Transfer the chicken and its broth to a baking pan, along with the chile peppers, crushed garlic, and lemon juice. Arrange the potato slices all around.

Bake, covered, for about 30 to 40 minutes. Remove the chicken from the oven and transfer it to a serving dish. Garnish with chopped parsley and lemon slices.

This recipe came our way in the course of an energetic and chaotic conversation on the subject of baked chicken with the women at the Olive Roots Cooperative in Zeitun. There were as many recipes as there were cooks. And they’re all fantastic!

Serves 4–6

2 pounds (1 kilogram) lean beef

1 packed cup (25 grams) parsley

1 medium onion, chopped

½ teaspoon black pepper

1 teaspoon ground allspice

½ teaspoon ground red pepper

1½ teaspoons salt

4–5 ripe tomatoes, grated or liquefied

2–3 potatoes, peeled and thinly sliced

Olive oil

Run the meat, parsley, onions, black pepper, red pepper, and allspice together through a food grinder, or pulse the parsley and onion in a food processor one at a time, then mix them well with preground meat and spices. Form this mixture into small oblong patties.

In a wide pot, pan-fry the patties in a little olive oil, about ⅓ cup (80 milliliters), until they are slightly browned on all sides. Drain off and discard the excess fat and return the kufta to the pan. Pour the liquefied tomatoes on top.

Neatly spread an overlapping layer of sliced potatoes over the tomato. Season this with salt and pepper. Bring to a low boil and cover, lowering the heat. Allow this to simmer for about 30 minutes or until the potatoes are fully cooked.

Serve with Khubz Kmaj (page 100), assorted pickles, and Ruz Imfalfal (page 206).

Um Sultan, a magnificent cook and farmer, was appalled that we were going to cite her on such a simple recipe. Kufta is considered a lazy cook’s food, something almost effortless for an everyday meal. But it is no less delicious for all that, and with fresh tomatoes and potatoes from Um Sultan’s farm, it was divine. While urban Gazans tend to use an elaborate range of spices, rural tastes rely on farm-grown ingredients.

We arrived at the farm of Um Sultan (Nabila El-Shami) in the eastern village of Bani Suhayla just as she and her exuberant extended family had finished harvesting a field of hot red chile peppers. The sacks of peppers were carried off to a nearby factory to be turned into filfil mat’hoon, and the family reclined in the shade to rest a bit. Ruddy and energetic, Um Sultan showed us around the meticulously organized and very productive farm, with orchards, vegetable fields, and animal pens all tidily packed into a few rented acres. The family owns land near the eastern border, but their farm there was destroyed by an Israeli incursion in 2003. She told us:

First they uprooted all the olive trees around our house. Then the livestock, the pigeons, the clay oven…. They destroyed it all. I was scared for my children; they were little then. So we fled and rented this place. It’s expensive, but I have more peace of mind this way. We don’t even try to go to our land now; it’s in the buffer zone and they’re always out there with their tanks and shells….

This was not the first time the family had been forced to flee. Before 1948, they had owned farms near Yaffa. They fled to Gaza and lived in tents in the Khan Younis refugee camp until the mid-1950s, when they managed to buy land and return to the farming life:

Our grandfather was still alive then, so he taught my uncle and father [to farm]. I learned from them. Then we began going to farming cooperatives and unions, taking courses… how to manage the land, how to plan, when to harvest. It’s not like we were born with this knowledge. And then we taught it to our children.

Few of the many refugees originally from rural areas in Gaza have been able to obtain land and return to farming. Um Sultan is justifiably proud of her family’s accomplishment, and as she cooks she introduces each ingredient with a grin: “Fresh from our farm!”

When Laila went back to visit Um Sultan’s family in 2013 (while showing chef Anthony Bourdain around Gaza), she found the farm still prospering and employing several neighbors, but now divided into individual lots for each of the daughters of the family. Like many villages in southern Gaza, Bani Suhayla is historically a matriarchal society, with land and property passed from mothers to daughters. Despite multiple displacements and losses, Um Sultan forges ahead, brash and big-hearted, transforming her small foothold in Gaza into a legacy for her daughters.

Serves 6–7

2 pounds (1 kilogram) extra-lean ground beef

1 packed cup (25 grams) parsley

6 cloves peeled garlic

2 green chile peppers

1 medium onion

2½ teaspoons ground allspice

1 teaspoon black pepper

½ teaspoon ground nutmeg

1 teaspoon ground cardamom

2 teaspoons salt

¼ cup (25 grams) bread crumbs

2 potatoes, thinly sliced

1 onion, evenly sliced

2 tomatoes, thickly sliced

3–4 very ripe tomatoes, liquefied in a blender and whisked through a sieve or 5 tablespoons tomato paste diluted in 2 cups (480 milliliters) water

Preheat your oven to 400°F (200°C).

Wash the parsley well and remove any thick stems. Run the beef, parsley, onion, garlic, and chile peppers through a meat grinder, or pulse them in a food processor. (If using this method, use preground beef, then pulse the remaining ingredients one at a time, beginning with the parsley and proceeding to the garlic, peppers, and onions). Transfer to a bowl. Stir in the spices and then the bread crumbs and mix well, adding a little more if mixture appears too loose.

Spread the meat mixture out evenly onto a 12-inch (30 centimeter) round oiled pan or a 9 x 13 inch (22 x 33 centimeter) casserole dish, completely covering the bottom. (Alternatively, the mixture may be shaped into 2 to 3 inch—5 to 6 centimeter—oblong ovals). Using the tips of your fingers, make a spiral indentation on the surface of the meat for the fat to rise into.

Bake for about 10 minutes. Remove the pan from the oven and drain off any excess fat that has accumulated, then top the meat mixture with neatly arranged overlapping layers of sliced potatoes, onions, and tomatoes.

Douse with liquefied tomatoes or tomato sauce, and cover the pan with aluminum foil. Return it to the oven and bake for an additional 40 minutes or until the potatoes are tender.

Serve with Khubz Kmaj (page 100) or Ruz Imfalfal (page 206) and salad.

A more elaborately spiced Gaza City kufta, made in the oven. Fresh tomatoes are used in this dish in summer; canned tomato sauce or paste are substituted in the off-season.

Serves 5–6

3 pounds (1½ kilograms) lamb shanks, cut into 3 parts each

64 ounces (1¾ liters) full cream yogurt at room temperature) full cream plain or strained yogurt, left out at room temperature

2 tablespoon flour

Olive Oil

Prepare the lamb shanks according to the instructions in the Maraqa recipe (page 24).

Whisk the yogurt through a fine mesh strainer into a large pot. Sift the flour into the yogurt. Turn the stove to medium heat and cook the yogurt for about 7 minutes, whisking continuously to keep it from separating.

Once it has come to a gentle boil, gradually add about 2 cups (500 milliliters) of the reserved lamb broth to thin it out and impart flavor. Continue cooking for an additional 5 minutes or so. Add the reserved meat chunks and serve with Rabee’iya (page 208).

Yogurt-based stews are more common in northern and eastern parts of Palestine and the greater Levant, but they are also made in Gaza, especially in spring. The stew goes by many names depending on region, including laban umo and shakreeya. Ideally, the yogurt should be left out overnight to sour slightly. Do not use yogurt with thickeners such as carrageenan or gelatin, or it will separate upon cooking.

On Schnitzel

On SchnitzelMost little restaurants and fast-food joints in Gaza feature schnitzel on their menus. This may come as something of a surprise to the visitor: schnitzel? Yes, your classic pan-fried weinerschnitzel is a favorite in Gaza, one of many tastes acquired over the years through contact with Israelis. Now, with Gaza totally isolated, it is easy to forget that for decades thousands of Palestinians in Gaza went every day to work in Israel, that Israeli and Gazan entrepreneurs had partnerships, that both commerce and social relations existed (though on vastly unequal footing). Adult Gazans remember this, and many speak admiringly of aspects of Israeli society or maintain contact with Israeli business partners, employers, and friends. For the enormous population of young people who were not old enough to work or travel before Israel sealed the borders in 2000, though, this is impossible. Though their lives are completely conditioned by Israel’s political decisions, they have never laid eyes on a single Israeli except for the soldiers who come in on tanks or bulldozers, wreaking destruction and destroying livelihoods. The generation of young Israelis to which those soldiers belong has likewise never met a single Gazan Palestinian in any other context. While interpersonal relations alone will not bring an end to this decades-long colonial occupation, they are still vital for instilling a sense of the other’s humanity.

Serves 6–7

1 whole rabbit or chicken

For the stuffing

1 onion, finely chopped

⅓ cup (65 grams) short-or medium-grain rice

⅓ cup (65 grams) bulgur

¾ teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon black pepper

½ teaspoon ground cardamom

⅛ teaspoon ground nutmeg

1 teaspoon qidra spices (page 34)

1 rabbit or chicken liver, chopped

½ cup (35 grams) toasted almonds

½ cup (10 grams) chopped parsley

Olive oil

For the broth

1 medium onion, chopped

1 teaspoon peppercorns

1 teaspoon cardamom pods

1 teaspoon allspice berries

1 very small piece of cracked nutmeg

1 cinnamon stick

2 bay leaves

2–3 pearls of mastic

For the rice

1½ cup (300 grams) rice, washed well and soaked in cold water

⅛ teaspoon ground allspice

¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon

2 tablespoons chopped parsley

2 tablespoons almonds, toasted and chopped

For the bread base

Several sheets of Khubz Saj (page 102)

3–4 tablespoons butter or ghee, melted

Wash the meat carefully in a bath of cold water, a little flour, salt, and lemon juice or vinegar. Set aside to let the bloody juices drain.

Prepare the stuffing: Rub the salt into the onions with your hands and sauté them in 2 tablespoons of olive oil until translucent. Add all the other stuffing ingredients except the parsley and nuts. Add ½ cup (120 milliliters) water and cook on medium heat, stirring occasionally, until the rice is al dente. When the rice is cool enough to handle, mix in the parsley and nuts. Stuff this mixture into the cavity of the chicken or rabbit. Leave a little space for the rice to expand. Sew the cavity shut with a needle and thread or weave several toothpicks through.

Next, brown the whole stuffed rabbit or chicken in a large pot in 3 to 4 tablespoons of oil. Add the chopped onion and sauté it together with the meat. Add enough water to fully submerge the meat. Bring to a boil and then reduce the heat, removing any froth or scum that rises to the surface. Add the whole spices (tied in a piece of gauze or disposable teabag, for easy disposal later) and the mastic. Simmer until the meat is cooked but not falling apart, about 30 minutes. Remove the chicken or rabbit carefully and set it aside. Strain the broth and reserve it.

Cook the rice: Strain the soaking water out of the rice, then sauté for about 1 minute in 2 tablespoons of oil until the rice turns slightly translucent. Add the 3 cups (720 milliliters) of reserved broth. Bring the broth to a boil, then lower the heat and simmer, covered, for about 20 minutes or until the rice is tender to the bite.

Prepare the base of saj bread: Dip each round of bread into the reserved broth, then tear all of the bread into short strips and layer them on a tray. Grease your hand with some ghee or butter and spread it across the warm, broth-soaked bread. Top the greased bread with the cooked rice, then sprinkle it with the allspice, cinnamon, chopped parsley, and browned nuts.

On top of this bed, in the center, place the stuffed chicken or rabbit. Serve alongside small bowls of Daggit Toma u Lamoon (page 28) and separate bowls of the remaining broth. Guests can then spoon these over their food as they eat. You may also serve fatta with bowls of plain yogurt.

Often made for guests, fatta is heir to a long Arab tradition of serving roasted meat with broth-soaked bread, said to be the favorite food of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). This is Gaza’s much-loved version, although the chicken or rabbit fatta served in modern Gaza would have been an embarrassment in more prosperous days. Several of the older women we interviewed described how, in the past, a guest’s arrival warranted the slaughter of a sheep, which would be roasted whole and presented on a bed of rice and bread. Given current shortages, being served a whole chicken or rabbit constitutes an equivalent honor.

Fatta is comprised of several layers: We have divided the ingredients by layer to avoid confusion. The final result is a bed of torn griddle bread lightly soaked in broth, then covered with a layer of buttery rice and topped with stuffed meat. It is customary to eat fatta with one’s right hand, while seated on the ground: the broth-soaked bread is used to scoop up the rice.

Fatema Qaadan greets us clad in a bright orange dress that matches her henna-dyed hair, one gold tooth in her radiant smile. A widow, she lives with her teenage daughter in a single room inherited from her late husband. It is a painfully hot summer day with a strong sandy wind, and to boot, it is Ramadan, the holiest month of the Muslim calendar, in which the observant fast from dawn till sunset. No matter: in this tiny space, using a single detached gas burner, she prepares a splendid Iftar meal for us of fatta bil aranib from one of the rabbits she raises in the sandy lot abutting her room.

Because her family is small, Fatema doesn’t qualify for most of the aid distribution packages that have become the primary means of subsistence for the overwhelming majority of Palestinians here. Tired of feeling helpless, she applied to participate in a new rabbit-rearing initiative she heard about at the local community center. To the envy of her neighbors, she was awarded one of the few available grants, providing her with a breeding pair of rabbits, materials for a hutch, and a few sacks of feed. She now boasts a flourishing family of young rabbits.

Originally from the village of Beit Jirja, just outside of modern-day Ashkelon, Fatema’s family had orchards and livestock in plenty. When Beit Jirja was attacked in 1948, her parents fled with thousands of others, leaving their gold and property behind. They found refuge in the Beach Camp in Gaza City, only to flee again in 1970 when Israeli troops under the command of Ariel Sharon (who was then defense minister) besieged the camp for months, razing their entire neighborhood and killing one of Fatema’s brothers.

Her family made their new home in nearby Beit Lahiya, where she married but was widowed one year after her daughter was born. Fatema recalls:

I asked my mother to make me a thobe [a traditional Palestinian embroidered dress] for my wedding. She would sit up on the roof, sewing the dress while crying, thinking of her son, Hasan. She embroidered the pieces, red on white cloth, then gave them to me and said, “I did my part, now it’s up to you sew it together.” So I did, and it’s my pride and joy. This dress means everything to me.

She holds the dress up to her breast as though she were a new bride.

Serves 5

2 pounds (about 1 kilogram) of small quail (defrosted, if using frozen ones)

For the stuffing

1 onion, finely chopped

Reserved quail organs, rinsed and chopped

1 teaspoon salt

¾ teaspoon turmeric

½ teaspoon allspice

½ teaspoon cardamom

¼ teaspoon black pepper

¼ teaspoon nutmeg

1 cup (200 grams) medium-grain rice, rinsed well Olive oil

For the broth

1 onion, coarsely chopped

1 teaspoon cardamom pods

1 teaspoon allspice berries

1 teaspoon peppercorns

1 bay leaf

1 cinnamon stick

1 very small piece of cracked nutmeg

2–3 pearls of mastic

Salt to taste

Juice of half a lemon

Wash the quail well, rubbing them inside and out with a spent lemon rind and some salt, then bathe them in a bowl of cold water with a fistful of flour mixed in. Rinse them, then set them aside to let the bloody juices drain for about 15 minutes.

Prepare the stuffing: Rub the salt into the onions and sauté them in about ¼ cup (60 milliliters) of olive oil on medium heat until they turn lightly golden. Add the chopped organs. Cook these for about 3 minutes, stirring occasionally. Stir in the spices and rice, sautéing for about 2 minutes, until the rice is well coated and slightly translucent. When it is cool enough to handle, divide the rice mixture into equal portions and stuff it into the cavity of each quail. Leave a little space for the rice to expand. Sew the cavity shut with a needle and thread or several toothpicks.

Gently stack the quail in a large pot, then add enough water to submerge them. Bring this to a boil over medium-high heat, skimming any froth that rises to the surface. Add the chopped onion, along with the assorted whole spices (tied together in a piece of gauze or a disposable teabag) and salt, then lower the heat and simmer, partially covered, for approximately 40 minutes or until the rice is cooked through.

Turn off the heat and set the pot aside until the quail are cool to the touch, then gently remove each quail with a slotted spoon and transfer to a baking pan. Brush the surface of each quail with a little olive oil and lemon juice. Broil on high heat for about 5 minutes, until the skins are golden brown and crispy.

Transfer to a serving platter and enjoy atop a bed of buttery rice and griddle bread, as in fatta (page 20) or alongside an assortment of small dishes.

Many residents of Khan Younis in the southern Gaza Strip will cite this as one of their most beloved delicacies. Our thanks to a gentleman who approached us after a talk we gave in Somerville, Massachusetts, and drew our attention to this historic favorite, which we had not included in the first edition of this book.

Quail-trapping season is in the fall, when the birds migrate from Europe to their wintering grounds in Africa. Many Gazans fondly remember camping out on the beach in the summer: they would rig nets along the shore in the evening and then wait until dawn, when the nets would be crowded with weary birds just landing from their flight across the Mediterranean. It is a practice that is said to date back to pharaonic times (a flock of quail succor the Israelites in the book of Exodus) but, due to massive and unregulated over-trapping around the Mediterranean, the migrating flocks have been drastically reduced. Quail are now rarely seen in Gaza at all.

You can find frozen (farm-raised, not wild) quail in many Middle Eastern markets or halal grocers. Stuffed quail may be served on its own, accompanied by one of the many autumn stews we feature in this book, or on top of a bed of buttery rice and griddle bread, like fatta (page 240).

Serves 7–8

2–3 pounds (1 to 1½ kilograms) boneless lamb or goat, trimmed of fat and cut into 2 inch (5 centimeter) pieces

2½ (450 grams) cups extra-long-grain rice

¼ cup (60 milliliters) olive oil

2½ tablespoons qidra spices (page 34)

1 teaspoon turmeric

1 tablespoon cardamom pods

2 teaspoons salt

½ teaspoon black pepper

½ teaspoon ground cardamom

¼ teaspoon ground cumin

2 whole heads of garlic, cloves unpeeled

½ cup (100 grams) dried chickpeas, soaked, or one 15 ounce (425 gram) can of chickpeas

4 tablespoons ghee

Prepare the meat according to the instructions in the Maraqa recipe (page 24). In this case, it is unnecessary to brown the meat. Strain, reserving both the broth and meat.

Soak the rice in cold water for 15 minutes, then strain it well.

In a clay pot or Dutch oven, sauté the rice in olive oil until it is well coated, about 2 minutes. Add 4 cups (about 1 liter) of strained broth along with the meat, salt, whole unpeeled garlic cloves, chickpeas, cardamom pods and all spices. Mix well and bring to a boil. Cook on medium-high heat for 5 minutes, then reduce the heat to low and cover the pot tightly.

The dish can be finished on the stovetop or in a preheated oven. If using an oven, preheat to 325°F (160°C). Tightly seal the pot with aluminum foil and bake it for about 45 minutes. Increase the oven temperature to 400°F (200°C) and bake for an additional 15 minutes or until the rice is cooked through and the broth has been absorbed. Check rice occasionally: If it seems to be drying out, add a little more broth, ¼ cup at a time. If you are finishing it on the stovetop, the rice will need approximately 25 to 30 minutes on a low flame, with the lid tightly closed.

Remove the pot from the heat and let the rice rest in the covered pot for 20 minutes. Meanwhile, melt the butter or ghee. Uncover the finished qidra and pour the melted butter or ghee over it. Carefully transfer to a serving platter or serve out of the clay pot. Serve with plain yogurt, Filfil Mat’hoon (page 28), and olives.

Qidra is a richly spiced, festive rice dish named for the hand-turned clay urn in which it is cooked. In southern Palestine it is prepared for major occasions such as weddings, birth ceremonies (aqiqa), and funerals. Traditionally it was cooked over slow-burning coals outdoors. In the city, the clay pots are taken to a community oven to be cooked, though few such ovens still remain. To serve, the urn is dramatically cracked open and the fragrant, buttery rice pours out.

Assuming there is no community stone oven where you live, a tightly sealed clay pot or a Dutch oven works well for making qidra.

While lamb is traditional, chicken or beef may be used instead.

At the end of a sandy alley near the Palestinian Sports Stadium and right behind the Holy Mary School lives the last man in Gaza City who still makes qidra as it is supposed to be made: in great handmade unglazed clay pots, tightly sealed and slowly cooked in a blazing stone oven. While Jamal does prepare the rice himself for some clients, mostly his is an oven service: the client provides and mixes the rice, spices, and meat, then Jamal takes care of the cooking.

He learned the art of the qidra oven from his father and grandfather and hopes to pass the oven on to his son. The oven was built in the early 1960s, all of stone, with intense butane heat. Jamal dexterously rotates the pots in the oven with a long hooked pole so they cook evenly. Each pot has the client’s name written on it with chalk.

Most of his clients are restauranteurs, but he also makes qidra for weddings, parties, and events. On Fridays there is a rush and the oven is full.

One of his clients comes by to pick up qidra for his restaurant. He opens each pot, smells it to make sure it is perfect, and pours a bowl of fragrant samna baladi (clarified sheep’s-milk butter) into each one before heaving the three hot urns into the trunk of his car.

Behind the oven building is an airy garden surrounded by fig and lemon trees, a big date palm, and climbing jasmine. An enormous dog—extremely uncommon in Gaza—lounges in the shade, and on the broad verandah are several birdcages with bright canaries jumping and singing. Two of Jamal’s daughters lean over the rail to say hello, pigtails bobbing.

Under the fruit trees are hundreds of clay pots of various sizes, ordered directly from a local potter. This scene, this gracious garden, this family: they feel as indigenous to this place as the red clay, and as fragile as the vessels into which the clay is shaped.

Makes 2½ pounds (1 kilogram)

2 pounds (about 1 kilogram) white flour

½ pound (250 grams) whole wheat flour

Olive oil, as needed

Water, as needed

Salt, as needed

Mix the flour and a pinch of salt on a large tray. Add cold water bit by bit, massaging the flour with your hands until a rough, dry dough is formed.

Place a sieve (a kurbala is dedicated to this specific purpose, but any wide based sieve should do) over a clean dry tray and put a handful of dough into the sieve. With an open palm, make a circular motion over the dough, pressing it against the sieve, so tiny pieces fall onto the tray below. At first this is somewhat difficult, but with practice it becomes easier. The resulting fine grain is the maftool. After each handful of dough has been pushed through the sieve, stir a few drops of olive oil into the maftool gently with your hand, making sure the grains don’t stick to each other, then pour it onto an open surface covered with a dish towel to dry a little. Repeat with the next handful of dough.

When all the maftool has been made, it is ready to either be sun-dried for later use or steamed for consumption (see “How to Steam Maftool” on page 250).

Maftool is a special source of local pride in the Gaza district. Much like Moroccan couscous (which is Berber North African in origin), it consists of tiny pearls of wheat steamed and served with a stew called yakhni. In the north, they make a slightly different version with larger, more circular grains called moghrabiya (“of Moroccan origin”).

The maftool itself can be made in quantity and sun-dried for later use or steamed immediately.

Here are two ways to make maftool, one more traditional, the other a modern labor-saving method taught to us by the ever-efficient Um Sultan. Both give excellent results. Don’t feel intimidated or let the apparent complexity of hand-rolling maftool dissuade you from trying the recipes!

If you are short on time, substitute store-bought instant Moroccan couscous (the whole-wheat varieties available in specialty grocers more closely resemble the Palestinian version) or, better yet, purchase handmade maftool sold by various Palestinian women’s cooperatives, such as Hadeel and Zaytoun in the United Kingdom or Canaan Fairtrade in the U.S. and elsewhere. Add the seasonings described in the recipes below when cooking.

Maftool is sometimes made with fine semolina, which is considerably more expensive in Gaza, and sometimes with a mixture of whole and white wheat flours. Feel free to use either.

Makes 2 pounds (approximately 1 kilogram)

2 pounds medium grind (#2)

white bulgur White whole-wheat flour, as needed

Salt, as needed

Olive oil, as needed

Soak the bulgur for an hour in cold water until swollen, then squeeze out any remaining water.

On a large tray, place a few handfuls of soaked bulgur. Sprinkle one generous handful of flour on top of it. Roll your hands gently over the bulgur with open palms in a circular motion for several minutes, until all the flour is clinging to the bulgur and no longer visible, and the bulgur has formed more or less regular, even little balls. This is the maftool.

Add a little salt and rub it in, then transfer the maftool to a fine sieve and shake out any remaining flour. Pass the maftool into a coarser sieve and shake it back and forth, as if winnowing. The maftool will slip through, leaving only a few oddly shaped clumps trapped in the sieve. If, like Um Sultan, you have some chickens, feed these clumps to them.

Pour a little olive oil over the winnowed maftool and with the same circular, open-palmed motion, work it into the grains until it is absorbed. Repeat this process until you’ve used up all the bulgur. Once the maftool is finished, mix it gently with your hands, again with palms open, for a few minutes. It is now ready to steam or sun-dry.

1 pound (500 grams) maftool (fresh or dried)

Olive oil, as needed

Salt, as needed

2 tablespoons dill seed

2 teaspoons red pepper flakes or 1 cup dill greens, chopped

1 small onion or 3 shallots, finely chopped

1 teaspoon cumin

2 lemons, quartered

In a two-part steamer or couscousiere, fill the bottom part with water and the lemon pieces. Bring to a boil. Meanwhile, smear the top part with oil and fill it with half the maftool. If the steamer’s holes are large, you may want to cover them with a strip of cheesecloth or other pure cotton cloth before adding the maftool. Allow this half of the maftool to steam uncovered for about half an hour.

Meanwhile, in a mortar and pestle, grind the dill seeds with ½ teaspoon of salt until fragrant. Add the onion and red pepper flakes and pound until they are coarsely mashed. Stir in the cumin and 4 tablespoons of olive oil. This dressing is called aroosit il maftool—“the bride of the maftool” for the enticing and discreet way it perfumes the grains. In Rafah, finely chopped dill greens are also added; in Gaza City, red pepper flakes are preferred. Spread a layer of the aroosit il maftool on top of the maftool in the steamer.

Cover the aroosit il maftool with the remaining maftool, and continue steaming. After 15 minutes, remove it from the heat and gently stir it with a wooden spoon to fluff the maftool, so each grain is separate.

Serves 5

3 pounds (about 1½ kilograms) chicken or turkey, cut into parts, bone-in

1 small onion, chopped

2 large onions, julienned

5 medium tomatoes, cut into vertical wedges

½ cup (100 grams) dried chickpeas, soaked overnight, or one 15 ounce (425 gram) can

6 cups (about 1¼ kilograms) butternut squash or carrots, cut into 1 inch (2½ centimeter) pieces

¼ cup (35 grams) dried sour plums or 1 teaspoon pomegranate molasses

2 teaspoons qidra spices (page 34)

1 teaspoon ground cumin

½ teaspoon turmeric

½ teaspoon black pepper

2 teaspoons salt

Olive oil, as needed

1 quantity steamed maftool (see recipe on page 249)

Wash the chicken pieces well, as instructed on page 26 in the section “Common Sense,” in a bath of cold water, vinegar, a little flour, and salt, and massage with spent lemon rinds. Rinse them well and set aside to let the bloody juices drain.

Warm some oil in a wide skillet and add the chicken or turkey pieces. Cook until it is golden brown on all sides. Add the onion, salt, and pepper and fry until the onion is translucent. Lower the flame and add water (about 7 cups, or just under 2 liters, enough to fully submerge the meat). Bring to a boil and remove any froth that rises to the top. Add the qidra spices, cumin, sour plums (or a teaspoon of pomegranate molasses), turmeric, and soaked chickpeas (if you are using dried chickpeas). Lower the heat and simmer, partially covered, for an hour. Strain and reserve the broth, and set the meat and chickpeas aside.

In a separate pot, sauté the julienned onions in 2 tablespoons of olive oil until they become slightly limp. Add the squash or carrots and tomatoes and stir for 2 minutes. Add 5 to 6 cups of the reserved broth, then cover the pot and allow it to simmer for 30 minutes or until the squash is tender. If you are using canned chickpeas, add them in the last few minutes of cooking, to heat through.

To serve, spread a bed of steamed maftool on a serving platter. Top this with the yakhni, using a slotted spoon to scoop it out of the pot, and ladle a little of the broth over this. Arrange the turkey or chicken pieces on top of the vegetables.

Serve with small bowls of extra broth and pinch-bowls of cumin, which each person may add to taste.

Abu Sultan, Um Sultan’s husband, used a freshly slaughtered turkey from their farm to make this yakhni, under the careful instruction and supervision of his wife—from whom, he says, he learned to prepare “just about everything.”

Yakhni is one of those culinary terms which reveals a whole history of relationship and exchange. From Southeast Asia to the Balkans, the term is used to refer to different dishes—always some kind of meat-based stew—in each local context. In Gaza, yakhni is always served with maftool.

Ibtisam Zimmo, from Gaza City, rest her soul, a dear family friend of Laila’s, told us that dried arasiya (native sour plums) used to be added to the broth to lend a note of sourness.

Off a dusty road on the outskirts of Rafah, Um Khalid (Nabila Qishta) welcomes us into a newly built concrete-block house with fantastic yellow loofah flowers starting to climb up the façade. Devastation and rubble surround the well-tended dooryard; the skeletons of two completely destroyed buildings loom over it. A tractor rolls by, carrying fodder to some sheep penned among the debris next door. Um Khalid explains:

My family has owned this land for a long time, but after my father died, my brothers decided it wasn’t worth the effort to continue farming it since so much of what they earned had to go toward taxes and irrigation. We couldn’t pay, and the family scattered: some to work in Saudi Arabia, others to the Emirates. The rest stayed in Khan Younis.

I got married and lived near the border here in Rafah. But then our house got demolished; it was January 20, 2004, at 7:20 PM, I’ll never forget it. When we left the house, we had nothing at all. Thank God we were all okay. It was a big house. The first time the bulldozers came was early in the morning, and all the neighbors came to our house, escaping from the demolition of their own houses. They started to tear down our house with all of us inside, but they stopped halfway through. A month later they came back and demolished it completely.

In those days, we didn’t make time-consuming foods like this (maftool). We had to buy takeout; there was no place to cook. Luckily we could afford it—not everyone could. For a long time, we were staying with friends and family members, then we rented one place and then another…. Finally, we built this house.

In those days, a lot of internationals came through here, and some stayed with us—people involved in solidarity campaigns. Sometimes they still write…. We miss those people, they were lovely. And they really enjoyed our food! But now they can’t get through the borders.

It is not just the solidarity volunteers who cannot cross the border anymore. With the Rafah border just a few hundred meters away, one feels its closure with special intensity. Everyone is stuck, on one side or the other. Um Khalid’s eldest son, an engineer, moved back to the family home after losing his job, joining the swelling ranks of unemployed young men desperate to get out of Gaza to seek employment. He calls us every so often asking for any lead, any work, we might know of. Her daughter Fida, a writer, teacher, and activist, is on the other side: she went to the United States to promote her widely acclaimed film about Gaza, Where Should the Birds Fly, and has since been unable to return to Gaza to see her family. She is now pursuing a master’s degree in film studies in California.

Serves 5–6

1½ pounds (approximately 750 grams) eggplant

1 medium onion, chopped

½ pound (approximately 250 grams) finely minced beef (preferably sirloin tips) or boneless lamb

¾ teaspoon salt, more for sprinkling on eggplant

¼ teaspoon black pepper

½ teaspoon cardamom

1 teaspoon allspice

⅛ teaspoon nutmeg

1 onion, julienned

8 garlic cloves, split into halves

1 green or red bell pepper, sliced into 1 inch (2½ centimeter) vertical strips

2–3 hot green chile peppers, thinly sliced into vertical strips

2 large tomatoes, sliced

Salt and black pepper to taste

¼ cup (60 milliliters) hot water or tomato sauce

Olive oil

Preheat your oven to 375°F (190°C).

Partially peel the eggplant in alternating fashion (one strip peeled, the next unpeeled, and so on), then cut these into slices 1 inch (2½ centimeter) thick. If you are using thinner eggplants, peel and slice them lengthwise.

Sprinkle the eggplants generously with salt and place them in a colander for 30 minutes in a sunny location until beads of moisture appear on the surface, or else soak them in a saltwater bath (¼ cup salt (75 grams) to 4 quarts (4 liters) water) for 20 minutes.

Drain the eggplant well, pat it dry with paper towels, then fry the pieces in hot vegetable oil until they turn golden. If you prefer to avoid frying, you can oven-roast them: Toss the eggplant pieces with olive oil, then arrange them on an oiled baking pan or cookie sheet and roast them in a 400°F (200°C) oven until they are browned on the bottom. Then broil them for 5 to 10 minutes. An indoor grill or panini press also works extremely well.

Meanwhile, in a skillet, sauté the chopped onion for a few minutes until it turns translucent, then add the meat and brown it well. Season it with the salt, black pepper, cardamom, allspice, and nutmeg. Add the liquid (water or broth) and simmer for 10 minutes.

In a separate skillet, warm 2 to 3 tablespoons of olive oil, then sauté the julienned onion and the garlic until they turn deeply golden. Add the peppers and cook until they are slightly charred.

In a shallow casserole dish, arrange layers of eggplant slices, followed by layers of meat, tomato slices, pepper, and onion. Season with salt and freshly cracked black pepper. Pour in the hot water or tomato sauce. Cover with foil and bake for about 40 minutes. Remove from oven to cool.

Musaqa’a should be served cool or at room temperature, with Khubz Kmaj (page 100) or Ruz Imfalfal (page 206).

While many in the West are familiar with the heavier Greek version of this dish, moussaka, few are aware that it is originally an Arab dish, still popular in Palestine. While talking about the origins of things is a dangerous business, especially in former Ottoman lands, in this case the etymology seems pretty clear: musaqa’a comes from the Arabic for “chilled” or “cooled.” As its name indicates, the dish is served cold, a perfect slice of summer.

In Gaza, the most typical recipe uses finely chopped beef or lamb stewed with spices and then layered between the eggplants and tomatoes, though for a quicker version you can also use fried ground meat. You can also omit the meat altogether and double the quantities of vegetables for a lovely vegetarian dish.

Serves 6–8

2 pounds (1 kilogram) lamb chunks, bone-in

2 cups (400 grams) soft spring wheat berries or grade 4 (extra coarse) bulgur

2 onions, finely chopped

2 rounds Khubz Saj (page 102) or other thin bread

3 or more tablespoons ghee or butter, melted

½ cup (35 grams) sliced almonds, fried

Chopped parsley, for garnish

If you are using wheat berries, coarsely crush them in a heavy mortar and pestle or pulse them a few times in a food processor or high-powered blender.

Prepare the lamb according to the instructions in the Maraqa recipe (page 24). Skim the broth, then add the wheat or bulgur and salt along with the whole spices. Simmer on low heat until the wheat is cooked through and the meat is fork-tender, approximately 90 minutes. The wheat will have absorbed much of the water. Strain, reserving the broth, meat, and wheat.

Meanwhile, submerge the rounds of saj bread quickly into some of the reserved broth, then tear them into small strips and spread these evenly in a high-rimmed serving platter or tray. Smear the bread with melted ghee or butter, using your hand or a brush.

Spread the wheat and meat mixture on top of the torn bread, along with a few ladles of the reserved broth. Serve the remaining broth in bowls alongside the ijrisha.

Garnish with nuts and chopped parsley.

Ijrisha is the name generally used for bulgur pilaf, but in the desert oasis town of Bir el Sabi’, it was also the name of a celebrated dish made for weddings and other special occasions, taught to us by Um Hazim Al-Ajrami. In Gaza, refugees from Bir el Sabi’ still make it to celebrate their important events. As with other wheat berry-based dishes, don’t be alarmed if the kernels don’t actually appear to get crushed: the point is to release some of the natural starches. If this appears too daunting, you can substitute the largest size of bulgur instead.

Serves 6

One 3–5 pound unripe baby watermelon (1½ kilograms), calabash squash, or ash gourd of equal weight

1 large or 3 small eggplants, about 1 pound (500 grams)

3 Middle Eastern koosa (also known as grey squash)

2 teaspoons salt

5 hot green chile peppers, chopped

1 bunch green onions (scallions), chopped

1 medium-sized white onion, finely chopped

1 pound (approximately 500 grams) very ripe tomatoes, chopped

1 pound (approximately 500 grams) cucumbers, peeled and finely chopped

2 lemons, peeled, segmented, and chopped

1 bunch fresh dill (about 25 grams), chopped

1 bunch parsley (about 25 grams), chopped

1 cup (240 milliliters) tahina

Freshly squeezed juice of two lemons

½ cup (120 milliliters) high-quality extra-virgin olive oil

1 qursa or other thick flatbread (such as naan), toasted and torn into pieces

Wrap the watermelon or gourd in foil, then roast it over a gas range, on a grill, or directly over an open fire or hot coals until it is soft to the touch and charred on all sides. It may be easier to pierce the watermelon with a thick skewer or stick while it is roasting. If you are doubling the recipe, skewer the melons or gourds with a thick wire. Repeat this procedure with the eggplants and squash, skipping the foil. Set all of the vegetables aside to cool.

Using a mortar and pestle, crush the hot peppers with the salt until they are well mashed. Add the tomatoes and pound until uniform and thick. The tomatoes can also be mashed by hand or pulsed in a food processor a few times.

Peel the cooled melon, squash, and eggplants and discard the charred skin. Chop them roughly, then mix the chopped pulp of these vegetables with the chile-tomato mixture, using your hands, in a large bowl until well combined. Add the scallions, cucumbers, onion, lemon segments, dill, and parsley and mix well.

In a separate bowl, combine the tahina and the lemon juice, thinning it with a little extra juice if necessary. Stir this, along with the olive oil, into the vegetable mash.

Add the torn pieces of toasted bread (enough so that the bread makes up roughly half of the dish) and knead the entire mixture well by hand until the bread has absorbed the liquids from the salad. Transfer and arrange on a large round platter, then drizzle it generously with olive oil.

Serve with small quartered white onions, olives, and assorted pickled vegetables.

For the qursa

3 cups (380 grams) flour

⅔ cup warm water (160 milliliters), more as needed

½ teaspoon salt

3 tablespoons warmed olive oil, plus more for drizzling

Knead together all ingredients until the dough is elastic and no longer sticky, for about 5 minutes. Form the dough into a ball, then flatten using the palm of your hand into a single 1-inch-thick disk. Drizzle both sides with olive oil. Bake on a grill rack, preferably on a wood-fired grill; alternately, cook in a frying pan on a stovetop or in the oven until well browned. A traditional qursa is placed directly on the grey embers of an open fire and covered in sand, which is then scraped off, along with any charred bits, before using.

This unusual dish is a specialty of the southern Gaza Strip and neighboring Sinai. Fattit ajir is a family affair (specifically a men’s affair) that can take more than half the day to prepare, as Laila discovered when visiting the Sheikh family, descendants of refugees from Bir el Sabi’ now living in Bani Suhayla. The dish is enjoyed out in the open in late spring or early summer, when baby watermelons are in season. The recipe calls for skewering young, unripe watermelons on a wire and fire-roasting them until charred, then mashing the pulp together with an array of vegetables, olive oil, and torn pieces of thick, unleavened fire-baked bread. The final dish is served in a large tray on the ground, and family members gather around to eat together using their hands.

If you cannot find unripe watermelon, use a small out-of-season melon or one that has white or pale green patches on its side. Use this part of the melon with its rind, wrapping it in foil. Otherwise, calabash squash or winter melon may be substituted.

The bread traditionally used is made from unleavened dough shaped into a thick disk, or qursa, which is then wrapped in newspapers or foil and buried in low-burning embers in the ground. Any thick, unleavened, and well-toasted flatbread can be substituted, though making your own qursa is relatively simple (we provide the recipe). Here, we have scaled down the recipe to serve just six, though traditionally fattit ajir would be made for a whole clan

While a large majority of Gazans are stricken with systematic unemployment and acute poverty, shops are still stocked with consumer goods, and there are still restaurants and cafés operating, some of them quite elegant. With the borders closed, industry ruined, and exports impossible, who is buying these goods at inflated prices? Where is the money coming from? The Gazan economy is so bizarre that it is worth taking a moment to trace the cash flows.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), which provides all services to the Palestinian refugee population, is one of the principal employers in Gaza, paying decent salaries to 11,000 people. These individuals in turn support many unemployed family members. The United States is the main UNRWA donor, followed by various European countries and Japan. No one in Gaza fails to note the irony of such a massive U.S. expenditure to feed and educate the same people it also pays (by way of aid to Israel) to bomb and imprison: “They feed us with one hand and strangle us with the other” is the common refrain.

The next main employer is the government, although one of the peculiarities of Gaza is that it is not entirely clear just who that is, and whoever it is can only barely be called a “government,” since the powers accorded to Palestinian self-rule by the Oslo Accords are so limited. That said, between 2007 and 2014, the Hamas party ruled in Gaza, with its corresponding body of civil servants, ministry workers, police, and so on. During that same period, the Fatah Party-led Palestinian Authority (based in Ramallah, in the West Bank) did not acknowledge the Hamas government’s legitimacy and maintained its own parallel government—with all the corresponding employees.

In 2014, a Consensus Government was forged under the leadership of Ramallah-based prime minister Rami Hamdallah in an effort to bridge the growing rift between the two territories, although this unity government’s actual presence and role in Gaza now is unclear. Suffice it to say that at least one and possibly two governments are paying salaries with funds drawn principally from international donors: the United States and Europe in the case of the Palestinian Authority, Qatar in the case of Hamas. Support from Iran, while still trickling in, has been reduced dramatically since 2011, when Palestinian factions refused to take sides in the ongoing war in Syria.

Lastly, as a sort of shadow structure to make up for the absence of any kind of economy besides aid and governance, there are all the many internationally funded nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) operating in Gaza to assist the hundreds of thousands of impoverished Gazans who are not refugees and therefore are not entitled to UNRWA services. These NGOs employ thousands of Gazans, as well as some international workers (at much higher salaries).

These systems—all of which compete for competencies that would normally belong to the state—are the principal means by which currency enters Gaza. Some additional money enters through remittances from Palestinians living abroad who send money transfers to their families in Gaza. Then this cash circulates: employees and their families shop for goods and services, sustaining a whole commercial and service sector as well as local market agriculture.

Many other places in the world have also seen their productive sectors destroyed and now survive only on government employment, remittances, and aid, but we don’t hear about them so often in the news; they don’t have highly publicized flotillas attempting to change their situation. Gazans themselves are quick to recognize this. Much of the formerly colonized world has been de-developed; what is peculiar about Gaza is how clearly, rapidly, and violently the process has occurred. Processes like what has happened in Gaza have happened elsewhere, from Dakar to Detroit, but seldom in such an explicitly intentional and violent manner.

What adds insult to injury is the fact that all of this is so very profitable for its perpetrators: Economists estimate that every dollar of aid that enters Gaza ends up in Israeli pockets, with a 120 percent increase in value. Gazan fruit trees are destroyed; then Israeli fruit is sent in and sold at inflated prices, with Gaza serving as a very profitable dumping ground for Israeli agricultural products. Houses are demolished, then aid organizations are obliged to buy reconstruction material from Israeli enterprises. This goes for most agricultural and all manufactured products. Since the borders are closed and Gazan manufacturing has been systematically destroyed by direct bombardment and by a ban on the import of materials and machinery, Gaza depends entirely on Israel to send in consumer products, which it does to the enormous benefit of its own export market. So all the millions of dollars being poured into Gaza by the international community to keep Gazans alive and relatively complacent serve as an indirect subsidy for Israel.