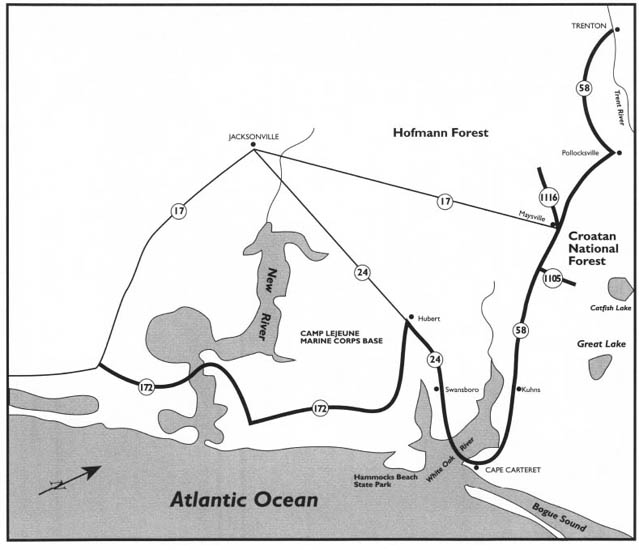

This tour begins at the intersection of N.C. 58 and N.C. 41 in downtown Trenton, the county seat of Jones County.

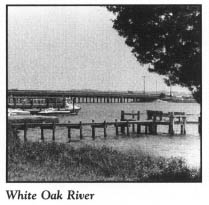

This tour begins in Trenton, the county seat of rural Jones County, and then visits the other two towns in the county, Pollocksville and Maysville. It passes through portions of Hofmann Forest and Croatan National Forest before traveling to the villages of Cape Carteret and Swansboro. Next comes a ferry ride to Hammocks Beach State Park, one of the least visited, but most intriguing, of North Carolina’s state parks. The tour concludes with a visit to mighty Camp Lejeune.

Among the highlights of the tour are the riverside towns of Jones County, Croatan National Forest, stories from remote Catfish Lake, historic Swansboro, Hammocks Beach State Park, and Camp Lejeune.

Total mileage: approximately 79 miles.

Separated from the ocean by Onslow and Carteret counties, Jones County is one of the least-visited counties of coastal North Carolina. Most people who visit do so not by choice, but because their travels on U.S. 17 take them here.

Rural in nature, the county has been blessed with, and influenced by, two coastal rivers: the Trent and the White Oak. Not surprisingly, the three incorporated towns in the county are located near the rivers. A visit to these towns—Trenton, Pollocksville, and Maysville—provides an opportunity to see small tidewater settlements that have changed little over the past century.

Trenton, with a population of five hundred, is a delightful town on the banks of the Trent River. Despite the town’s small size, an interesting historic district is to be found on the streets intersecting N.C. 58, the town’s principal street. This district, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, offers a variety of architectural styles, including Federal, Gothic Revival, and East Lake.

To enjoy the handsome ensemble of century-old commercial buildings and graceful homes in Trenton, park near the intersection of N.C. 58 and N.C. 41 and walk west on N.C. 58. The 4-block section stretching to the old high-school building at School Street contains a good selection of the town’s old houses.

After you have enjoyed this 4-block stretch, return to the intersection of N.C. 58 and N.C. 41 and turn right, or south; N.C. 58 and N.C. 41 run conjuctively heading south.

Located on the eastern side of the street, the Jones County Courthouse dominates the first block south of the intersection. Built in 1939, the two-story, rectangular, brick Colonial Revival building is distinguished by its pilastered entrance pavilion and its three-stage polygonal cupola. For many years, this courthouse was one of the few in the state to provide office space for local attorneys.

Located behind the courthouse is an old jail that is believed to be the oldest brick building in town. It was constructed between 1867 and 1873.

One block south of the intersection, turn left on Lake View Avenue. It is 1 block on Lake View to the intersection with Weber Street. Here stands Grace Episcopal Church, a tiny, strikingly beautiful building constructed in 1885. The interior of the gray frame structure still features its original hand-hewn furnishings.

Return to your car and drive south on N.C. 58.

Although not incorporated until 1874, Trenton actually dates from the creation of the county in 1779. Initially known as Trent, the town was renamed Trenton in 1784. The source of the name is subject to dispute, as is the case with many places in coastal North Carolina. Some historians contend that the town was named for Trenton, New Jersey, but a more logical source is the nearby river.

Trenton enjoyed a degree of prominence in its early years, because of its location on the stagecoach road from New Bern to Wilmington. On April 22, 1791, President George Washington stopped at Trenton. The house where he dined vanished long ago.

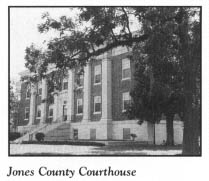

It is 0.3 mile on N.C. 58 to Brock Mill Pond, the most eye-catching feature of Trenton. This magnificent elongated pond, rimmed by moss-draped cypress trees, serves as a recreational area for boaters and water-skiers. A gristmill has operated on the pond for more than two centuries. The existing mill dates to the 1940s.

Slave labor was used to construct the dam that created Brock Mill Pond. Early Trenton residents built their homes around this majestic body of water.

Continue following N.C. 58 as it winds lazily for 10 miles through beautiful farmland to the intersection with U.S. 17 approximately 1 mile south of Pollocksville. Turn north on U.S. 17 and proceed to Pollocksville, a picturesque town on the banks of the Trent River.

Considered the most beautiful river in America by its admirers, the Trent is unlike most other coastal rivers in North Carolina in that its banks are high above the water and are thus suitable for development. Accordingly, a number of old houses are visible along the riverbanks of Pollocksville.

The municipal dock in the heart of town affords a spectacular view of the black river. From Pollocksville, the Trent flows southeast to its confluence with the Neuse River in New Bern. In 1709, the intrepid explorer John Lawson gave the Trent its name, most likely for the river of the same name in England.

Pollocksville is believed to be the oldest town in Jones County. As early as 1779, there was a settlement here called Trent Bridge, and before 1828, a post office by that name was established. Long before U.S. 17 was conceived, the river served as the town’s avenue of commerce. A steamboat landing was located on the river before the Civil War.

Turn around and head south on U.S. 17 leaving Pollocksville. It is approximately 7 miles to the junction with N.C. 58 in Maysville, the largest town in Jones County. Situated near the banks of the beautiful White Oak River, the town has maintained a population of approximately a thousand for more than half a century.

Younger than either Trenton or Pollocksville, Maysville grew from a settlement known as Cross Point in 1829. When the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad reached the sleepy village in 1892, its economy received a welcome boost. Five years later, the town of Maysville was incorporated.

Because it is located adjacent to Croatan National Forest and Hofmann Forest, Maysville serves as an area hunting center. Guides for bear and deer hunting are available at Maysville, Trenton, and Pollocksville.

If you are interested in taking a side trip, turn west off U.S. 17 onto S.R. 1116 in Maysville. It is 9.2 miles to Hofmann Forest, located in an area of pocosins commonly associated with the Carolina bays. (For more information on Carolina bays, see The Land of Waccamaw Tour, page 328–30.)

Covering some seventy-eight thousand acres in Jones and Onslow counties, the northern half of the forest lies in the southern midsection of Jones County. The forest bears the name of Dr. Julius V. Hofmann (1882–1965), the first person to earn a Ph.D. in forestry in the United States. Hofmann established the School of Forestry at North Carolina State University. Today, the university uses a portion of the forest for research and instruction in forestry management.

Two particular areas of the forest are of special note. Ancient trees towering seventy-five feet or more thrive in the Pond Pine Area, while cypress trees, some of which are six to seven feet in diameter, thrive in the twenty-seven-acre Cypress Natural Area.

Approximately thirty thousand acres of the forest, managed by the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, have been set aside as a game area. The hunting of fox, deer, and bear is regulated. Hiking in the forest is permitted. The fire roads throughout the forest make excellent hiking routes.

Retrace your route to the junction of U.S. 17 and N.C. 58 in Maysville to complete the side trip.

Leaving Maysville, turn southeast off U.S. 17 onto N.C. 58 as the road enters Croatan National Forest. After 2.6 miles, N.C. 58 intersects S.R. 1105. Turn east on S.R. 1105 and proceed into the heart of the forest for 6.2 miles to the Craven County line. Note that the road is unpaved for the last 4 miles of the drive. Along this route, you will enjoy a spectacular view of the magnificent forest.

Lying between the Neuse and White Oak rivers, Croatan National Forest is a national treasure that sprawls over 308,234 acres in Jones, Craven, and Carteret counties. Within its boundaries is one of the most extensive pocosins in the state. Highly productive forestland covers the other half of the national forest. Blended within these two natural habitats are the associated swampland and numerous Carolina bays.

Congress passed the Weeks Act in 1911, which authorized the acquisition of the forest. The actual purchase did not occur until 1933, in response to the economic woes of the Great Depression. The tract was to be used for scientific experiments leading to the restoration of cutover and burned forestland. Its name came from the Algonquin word for the Indians’ “council town,” which was located nearby. Many famous men, including Babe Ruth, have hunted in Croatan National Forest.

Recreational opportunities are provided for the public at three primary sites. Most visitors use the Neuse River Recreation Area, located on U.S. 70 just west of Morehead City. That site offers boating and fishing on a scenic 1-mile stretch of primitive river beach. Camping is also permitted at the site. The other primary access sites—Haywood Landing and Cedar Point Tideland Trail—will be discussed later in this tour.

Of the 157,000 acres of the forest owned by the federal government, 90,000 are pocosin. Most of the remaining acreage is timberland of cypress, oak, gum, and pine. Numerous insectivorous plants are found throughout the forest.

Wildlife abounds in the vast wilderness. Since the forest is managed as a game land, hunters must comply with all local, state, and federal game laws. At least seventy-eight species of reptiles and amphibians thrive here. One of the largest populations of American alligators in the state is found around the bay lakes of the forest. The forest’s location along the Atlantic flyway also makes it a habitat for seasonal waterfowl. Egrets, hawks, owls, bald eagles, ospreys, and red-cockaded woodpeckers are permanent residents.

Sadly, the forest is one of the last domains of the eastern black bear, once prevalent all across the coastal plain but now almost hunted to extinction. In 1982, the black-bear population was estimated to be between 750 and 1,000 in the entire state. Some authorities believe the black bear will become extinct before the turn of the century.

Within the pocosin area of the forest are five enormous Carolina Bay lakes. The largest among them is the 2,600-acre Great Lake. Though this lake measures 2.5 miles by 3.5 miles, it has a maximum depth of only five feet. The other lakes in the forest are also extremely shallow. Most are not noted for their fishing, although 106 species of fish have been recorded. The lakes are known for their large populations of snakes and alligators, some measuring fourteen feet long. These lakes lie in a remote, forbidding wilderness area virtually inaccessible to humans.

When you reach the Craven County line, you will be about as close as it is possible to get by improved road to one of the most significant of these lakes. Every year, thousands of tourists visit Croatan National Forest without knowing of the existence of the thousand-acre lake less than 2 miles due north of where S.R. 1105 hits the Craven County line. Despite its rather unsophisticated name, Catfish Lake provides a natural wilderness setting that is unequaled anywhere along the coast. In fact, it is considered to be among the wildest, most mysterious places in all of North Carolina.

Few people have ever seen Catfish Lake, because it is completely encircled by a peat-filled pocosin that makes road building to the lakeshore here virtually impossible. Near the current tour stop, a forest service road makes its way close to the lake. Throughout much of the year, even foot travel over the pocosin causes the surface of the earth to tremble for several yards in all directions. To further complicate matters, the junglelike undergrowth surrounding the lake makes a hike to this eerie place impossible except in late autumn and early winter, when the underbrush has died off and the ground is dry.

In addition to the hazardous terrain, any attempt to walk to the lake is fraught with danger because of the heavy population of wildlife: poisonous snakes and spiders, wild boar, bears, alligators, and wildcats. Any person desiring to visit should first hire an experienced guide who is thoroughly familiar with the lake and its surroundings.

As there are no well-marked trails leading to the lake, numerous experienced outdoorsmen have been hopelessly lost in the surrounding wilderness. In the 1930s, a timber estimator entered the forest in the vicinity of Catfish Lake and never returned. Four years later, while constructing a fire road, forest-service workers unearthed a human skeleton believed to be that of the unfortunate man.

The source of the lake’s waters has never been discovered.

The lake’s name is derived from the bounteous catfish thriving in its waters. A number of legends and stories have evolved concerning the fish in the lake.

It is said that a young Confederate soldier found his way into the lake wilderness after he deserted his company near Maysville. Some years later, a group of hunters found his skeleton near a rotting camp on the lakeshore. A stack of catfish bones large enough to fill a two-horse wagon was located at the camp. Apparently, the deserter had lived near the lake and fed himself with its bounty.

Folks in Maysville tell another tale about the unbelievable quantity of catfish in the lake. According to the story, a group of fishermen entered the lake with a goal of determining whether it was actually filled with fish. Arriving late in the afternoon in order to set their lines before dark, the men were delighted as they took boatload after boatload of fish and deposited them on the banks. As midnight approached, the fishermen, blessed with an enormous pile of catfish, decided to call it quits. To their chagrin, as they attempted to divide their catch among their sacks, they were surrounded by countless pairs of horrifying green eyes glowing in the light of their lanterns. These eyes belonged to dozens of ravenous wildcats attracted to the banks by the smell of the fish. The fishermen had little choice but to toss a portion of their catch to the animals to satisfy their appetite.

As the wildcats fought over the catfish, screaming fiercely, the fishermen gathered as many fish as they could hold and made a run for it. Throwing fish to the pursuing wildcats, they exhausted their supply by the time they finally reached the road and safety.

Retrace your route on S.R. 1105 from the county line back to N.C. 58. Turn south on N.C. 58 and drive 5.3 miles to the first national-forest road leading west. Turn west onto this road for a pleasant 2.2-mile drive under a canopy of towering trees to Haywood Landing, one of Croatan National Forest’s recreational sites.

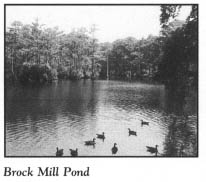

Located on the banks of the White Oak River, this landing provides a delightful spot for fishing, boating, and picnicking. It is also the best place to sample the natural splendor of the White Oak River.

Few rivers in all of North Carolina can compare in beauty with the White Oak. Rising in the black, peaty soil of southern Jones County and northern Onslow County, the river slowly winds for 20 snakelike miles along the Jones County-Onslow County line and the Carteret County-Onslow County line until it empties into the Atlantic through Bogue Inlet. On John Lawson’s map of 1709, the river appeared as the Weetock, while on the Moseley map of 1733, it was shown as the Weitock. By 1780, the river was shown as White Oak on the Collett map.

Rich in tannic acid, the White Oak is a black-water river, as distinguished from the brown-water rivers of the North Carolina mountains. It begins as small rivulets flowing from the pocosins within Hofmann Forest. The water changes from fresh to brackish to salty as it nears the ocean. Side creeks flow into the river along its route.

Much of the land along the banks is swampland. Lofty cypress trees mix with lush, exotic vegetation such as wild rice, swamp rose, wild camellias, and duck potatoes. On the bluffs, hardwood forests of oak, hickory, and maple provide a beautiful spectacle during autumn, when their leaves turn from green to various shades of purple, rust, and gold.

Animal life along the river is also varied and interesting. Deer frequently graze quietly on the banks, where raccoons and opossums may also be observed. The summer months bring forth many water snakes and some alligators, although the latter are rarely seen. The riverbanks provide habitat for numerous species of birds. Hawks fly above the forests, and woodpeckers break the silence of this natural paradise as they work on trees. As darkness descends upon the river, numerous owls make their presence known.

Retrace your route to N.C. 58. Turn south on N.C. 58 and drive 2.5 miles to Kuhns, a small crossroads community in the northwestern corner of Carteret County.

National-forest roads leading east from Kuhns make Great Lake the most accessible of the lakes in Croatan National Forest. This rural outpost on the fringe of the forest was named for William Kuhns, a German native who settled in the area in the distant past and engaged in lumbering along the White Oak River.

Continue south from Kuhns on N.C. 58. After approximately 3.7 miles, turn right, or west, onto S.R. 1106. Proceed 1.7 miles on S.R. 1106 to the Crystal Coast Amphitheater, constructed in 1985 on the banks of the White Oak.

During its premiere season and for one season thereafter, this two-thousand-seat facility was the home of the outdoor drama Blackbeard’s Revenge. Based on a plot by North Carolina playwright Stuart Aronson, the drama highlighted the early career of Blackbeard. After its second season, the pirate adventure gave way to a religious passion play, Worthy Is the Lamb, which continues to run each summer season from mid-June until late August.

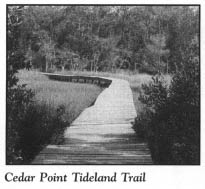

Return to N.C. 58 and continue 3.5 miles south from the amphitheater, where a sign on the western side of N.C. 58 will direct you to Cedar Point Tideland Trail, another of the recreational areas in Croatan National Forest. One of the two planned camping sites in the forest, Cedar Point has fifty camping spaces, drinking water, and restrooms.

Because Cedar Point is located at the mouth of the White Oak, its interpretive nature trail provides a rare opportunity to see the natural forces at work at an estuary. Winding its way through tidal marshes covered by boardwalks and through hardwood forests, the trail features strategically placed wildlife-viewing blinds.

From Cedar Point, return to N.C. 58. Proceed south on N.C. 58 for 0.8 mile to the intersection with N.C. 24 at the community of Cape Carteret. With a population of nearly fifteen hundred, this town serves as the commercial hub of the resorts just across Bogue Sound on Bogue Banks. Incorporated in 1959, Cape Carteret was established by the developers of Emerald Isle Beach.

Turn west onto N.C. 24. The 5-mile drive from Cape Carteret to Swansboro is a scenic one. Lining the road are numerous antique shops. During the summer months, roadside fruit-and-vegetable stands featuring Bogue Sound watermelons attract large numbers of motorists.

If you care to make a brief side trip, turn off N.C. 24 onto S.R. 1214 approximately 1 mile south of Cape Carteret. Approximately 0.1 mile east of the intersection, an unpaved road leads to an unusual octagonal house constructed in 1856. This house is privately owned and is not open to the public.

As N.C. 24 nears the White Oak River, the antique shops and roadside markets give way to vacation cottages and fish houses. From the bridge crossing the river, you will be treated to a postcard panorama of the beautiful river and the Swansboro waterfront. You may also catch a glimpse of Russells Island, formerly known as Huggins Island. Located on the waterfront just south of the bridge, the island appeared on early maps as Stones Island. This island has an interesting history.

During the final months of 1861, a Confederate earthwork fort—Fort Huggins—was constructed on the island to guard Bogue Inlet and the access channels to Swansboro. The fort contained underground bunkers and barracks for the two-hundred-man garrison that arrived in January 1862. Two months later, the fort was abandoned when its guns and men were needed for the defense of New Bern.

When Major General Thomas G. Stevenson and his Union forces invaded Swansboro on August 19, 1862, they burned the underground bunkers and barracks. Two months later, in an attempt to impress his superiors, Union naval officer William B. Cushing—who later made a name for himself when he destroyed the Confederate ram Albemarle at Plymouth in 1864—boasted that he had destroyed Fort Huggins. However, the fort had been laid to ruin several months before Cushing ever set his eyes on it.

Following the war, the island was used for farming. Despite the years of cultivation, the earthworks were left relatively undisturbed. In 1962, archaeologist Stanley South excavated an underground bunker at the fort. Remains of charred timbers were also found. Although the fort is now overgrown with vegetation, its earthworks are remarkably intact. A state historical marker erected near the bridge commemorates the fort.

Acclaimed by its residents as “the Friendly City by the Sea,” the charming port town of Swansboro has greeted visitors to the western banks of the White Oak for more than 250 years.

At Bicentennial Park, located on the northern side of U.S. 58 at the foot of the bridge, a handsome statue of Otway Burns, Swansboro’s most famous son, welcomes visitors. Burns was born in the village in 1775. From 1810 to 1819, he operated a shipyard on the eastern side of Main Street between Front Street and the river. It was at that spot that the most historic event in the ancient port town’s history took place. In 1818, Burns completed work on the Prometheus, thereby giving Swansboro the distinction of being the construction site of the first steamboat built in the state.

To sample the salty atmosphere that pervades old Swansboro, turn left, or east, off N.C. 24 onto Front Street. Park on the street near where Front ends at Church Street after 3 blocks. Swansboro is best enjoyed on foot.

Visitors will be disappointed if they expect to see the site of historic events that shaped the destiny of the state or grand buildings of bygone eras. Swansboro is not Edenton, New Bern, or Wilmington, nor does it pretend to be. Rather, it is an unpretentious fishing village that has preserved its maritime heritage.

Despite Swansboro’s small population, estimated at approximately thirteen hundred, few towns provide a better view of what coastal North Carolina must have looked like many, many years ago. As visitors walk along Front and Water streets, located on a bluff just above the river, they travel down lanes that have witnessed more than two and a half centuries of American history. Not only is Swansboro the oldest town in Onslow County, it is also one of coastal North Carolina’s oldest communities.

From your car, walk back east along Front Street.

The waterfront has been the focal point of activity in the downtown area ever since the town was founded. Long gone are the large sailing vessels that carried cargo to and from distant ports, but in their place are many commercial fishing boats and pleasure craft that dock on the waterfront and along the causeway of N.C. 24.

Turn right off Front Street onto Main Street, which soon dead-ends at a spot where a municipal wharf existed throughout much of the town’s history. Here stood the original wharf where trade flourished during the third quarter of the eighteenth century, and from which the town took its first name, Week’s Wharf.

Along the ancient streets of Swansboro are some historic structures little altered over the past two centuries. This treasure trove of commercial and residential buildings is concentrated along four downtown streets. The fine ensemble of commercial buildings now houses an assortment of cafes and quaint antique and gift shops.

Return to Front Street and turn right. Constructed around 1840, the Robert Spence McLean Store building, at 116 Front, is situated on lot No. 5 of the original town layout. During the Civil War, the Confederate post office was housed in this building. It was raided for tobacco and other items by Union troops on several occasions.

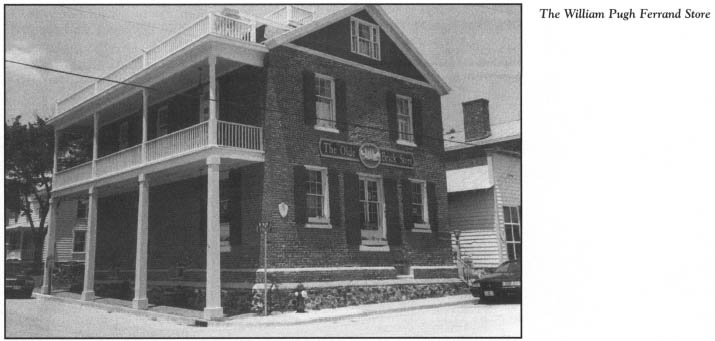

Located just down the street at 122 Front, the William Pugh Ferrand Store, known as “the Old Brick Store,” was erected in 1839, replacing a store that burned the year before.

Beautiful, century-old homes lining the quiet streets back of the waterfront help to preserve the “Down East” atmosphere of Swansboro. Most of the houses are two-story, white frame structures with well-tended yards displaying evidence of the seafaring lifestyle of the residents: stacks of crab pots, drying nets, hunting decoys, and small boats.

Return to Main Street and turn right. After 2 blocks, turn left on Elm Street, which boasts an impressive array of homes dating back more than two hundred years.

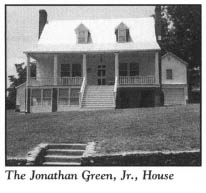

Located at 114 Elm, the Jonathan Green, Jr., House was constructed by the son of one of the original settlers of the town. Thought to be the oldest house in Onslow County, it is definitely the oldest in Swansboro. Evidence indicates that the house was constructed before the lots in the town were laid out in 1769 and 1770.

The exact date of the first European settlement in the Swansboro area is unknown, but it is certain that the shores of the White Oak at or near the modern town were settled by the first decade of the eighteenth century.

In 1711, the Indians living on the river aided the Tuscaroras in their rampage at New Bern and in the surrounding area, including the site of Swansboro. William Bartram, the father of noted botanist John Bartram, was murdered by the marauding Indians in the morning hours of September 22, 1711, at his home 4 miles east of Swansboro.

Once the threat of Indian violence ended, the White Oak River area was reopened for land grants in 1713. Soon thereafter, settlers from New England, Maryland, Virginia, northeastern North Carolina, and Carteret County began pouring into the region. Two brothers from Falmouth, Massachusetts—Jonathan and Isaac Green—are believed to have been the first white settlers on the exact site of Swansboro. They purchased land here in 1730. Jonathan and his wife, Grace, constructed a plantation house near the mouth of the river. Five years later, Jonathan died. His widow subsequently married Theophilus Weeks.

Theophilus Weeks is known as “the Founder of Swansboro.” He was also a native of Falmouth, Massachusetts, and most likely moved with the Greens to the area. After his marriage to Grace Green, Weeks moved to her plantation. In 1757, he was appointed inspector of exports for Bogue Inlet, a position he held until his death in 1772.

In 1769, Weeks began laying out streets and lots after deciding to establish a town on his plantation lands. Although the new town initially grew slowly, it was the only village on the North Carolina coast between Beaufort and Wilmington. Leading citizens of the area became associated with the port as it began to attract a growing trade in naval stores.

In its infancy, the town was known by various names: Week’s Wharf, Week’s Point, New Town, and Bogue, the most popular name during the American Revolution. As the Revolutionary War was drawing to a close, the North Carolina General Assembly incorporated the town on May 6, 1783, and named it Swannsborough, in honor of Samuel Swann, an early Onslow County statesman. Recognizing the commercial importance of the town, the general assembly enacted legislation in 1786 that created the port of Swannsborough the following year.

According to the 1800 census, forty-nine people lived within the town limits. Trade was brisk. Stores and other commercial facilities were constructed on the waterfront throughout the first half of the century.

However, the port never recovered from the effects of the Civil War. Following the war, much of the ocean shipping traffic shifted to the deepwater ports of the coast.

The local economy was bolstered by area lumbermills, many of which operated until the Great Depression. In the town’s charter of 1895, the modern spelling of Swansboro was adopted.

Over the past half-century, commercial fishing, boat building, and tourism have allowed Swansboro to enter the modern age without destroying its character.

From the Jonathan Green, Jr., House, continue west to the 200 block of Elm Street, which offers a couple of interesting historic houses.

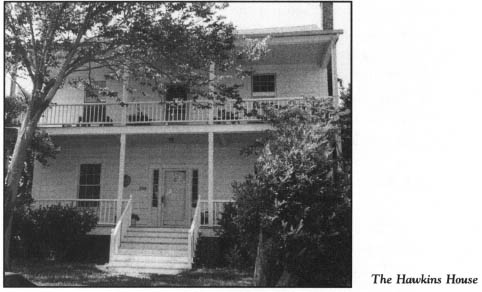

Located at 208 Elm, the Hawkins House was built between 1830 and 1840. While home on furlough to visit his parents, a young Confederate soldier was captured in one of the upstairs bedrooms by Union forces during their occupation of the town in 1862.

Constructed in 1826, the Bazel Hawkins House, at 224 Elm, once stood at the corner of Water and Spring streets. This two-story frame structure was moved to its present site when its original location was purchased by a lumber company.

Retrace your route to where you parked your car on Front Street to resume the driving tour.

Drive back east on Front Street to Moore Street and turn left. After 2 blocks, Moore merges into Elm. Turn left, or south, off Elm onto N.C. 24 and proceed 1.9 miles through the modern commercial district of Swansboro to the entrance to Hammocks Beach State Park. Turn east on S.R. 1511 for a 2.1-mile drive to the ferry landing.

The adage “Half the fun is getting there” holds particularly true for this state park. Covered pontoon boats, each with a capacity of thirty-six passengers, ferry visitors from the mainland to the park from Memorial Day to Labor Day. Each one-way trip takes approximately twenty-five minutes, as the boats slowly wind their way through a maze of beautiful marsh islands. This ride provides a refreshing opportunity to relax and enjoy the magnificence of the unspoiled North Carolina coast. As with most state-operated ferries, you can expect waiting lines at the mainland ferry landing during peak vacation periods. Because access is limited to watercraft, visitors can reach the island only by private boat during the off-season.

Squeezed between heavily developed Bogue Banks and bomb-scarred Brown’s Island, 3.5-mile-long Bear Island—or Hammocks Beach State Park, as the entire island is called today—is a paradise for conservationists and nature lovers. Upon reaching the ferry landing, you will discover the picturesque landscape of a unique place: a publicly accessible island that remains close to its natural state. Trees, including water oak and cedar, line the sound side of the island.

From the ferry landing, you can reach the ocean strand by taking a 0.5-mile hike through an area of spectacular grass-topped dunes. Many of the dunes are thirty feet high, and some reach sixty feet, providing exceptional views of the sea and sound. The tall dunes on the eastern half of the island are highly visible. Unfortunately, they are smothering the maritime forest there.

Visitors are rewarded for their trek across the sandy backbone of the island. Blessed with more than 3 miles of ocean frontage, Hammocks Beach State Park has been called one of the most beautiful and unspoiled beaches on the Atlantic coast.

Of the wildlife on the island, the most interesting is the endangered loggerhead turtle, which comes ashore to use the beach as a nesting area. Signs have been placed on the strand to warn humans of the nesting grounds. Since the park is considered a prime nesting area for the turtle, it is often closed on summer nights during full moon-high tide periods, the optimum time for egg laying.

The state of North Carolina has done an admirable job of providing visitor amenities on the island while maintaining it as a wilderness area. A large bathhouse designed to blend with the island environment contains shower rooms, restrooms, a refreshment stand, and a shelter that provides refuge from inclement weather. Picnic tables are located adjacent to the bathhouse. Nothing else has been constructed on the island to interfere with its natural state.

A number of activities are available to visitors. One of the prime attractions is a protected swimming beach with seasonal lifeguards. Fishing, shelling, and bird-watching are other popular activities. Primitive overnight camping is allowed, but campers are required to register with park rangers. Hiking is a very popular attraction, with more then 3.8 miles of trail available. Various free nature programs and hikes are offered by rangers.

Before the park opened in 1961, the island, described by a former owner as a place “where every day is Sunday,” had a long recorded history. In fact, it was one of the first barrier islands mentioned in the Colonial Records of North Carolina.

Tobias Knight, the colony’s secretary of state, acquired the entire island by land patent. While it was in his ownership, Knight was alleged to have associated with Blackbeard and other North Carolina pirates. Tales of pirate treasure buried on the island abound to this day.

In addition to being known as Bear Island or Bear Beach, the island is still known locally as Heady’s Beach, in honor of Daniel Heady, a former owner. How the name Bear Island came about remains a subject of dispute. Some contend that it came from nearby Bear Creek, while a local legend contends that Daniel Boone’s bear-hunting success on the island resulted in the name. Supposedly, the famous trailblazer killed ninety-six bears on the island in one season.

After an attack by Spaniards at Bear Inlet in 1747, the colonial assembly provided a short-lived fort at Bear Island. For the next 150 years, Bear Island was put to various uses by whalers, fishermen, and even a nudist colony. A noted New York brain surgeon purchased the island in 1914 and in so doing changed the course of its history. Dr. William Sharpe, a pioneer in neurosurgery, owned Bear Island for the next forty-five years.

Sharpe’s love affair with the North Carolina coast began in 1911, when he arrived with some friends on a duck-hunting trip. On that expedition, he began a long friendship with a black guide, John Hurst. Dr. Sharpe employed Hurst to locate some land for use as a “retreat that would be beautiful, isolated, and have an abundance of fish and game,” as the physician put it.

It took Hurst three years to find a place where Sharpe could escape the rigors of his profession. Known as “the Hammocks,” Sharpe’s estate consisted of forty-eight hundred acres on a mainland peninsula and Bear Island.

Shortly after he acquired his retreat, the physician named John Hurst and his wife, Gertrude, caretakers. Soon, Sharpe reported receiving unsigned letters containing threats from local residents upset that a black man had been appointed manager of the property. Through a notice in area newspapers offering a $5,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of any person damaging the island or its occupants, Sharpe ended the threats. Nevertheless, he continued to have his share of troubles with his island paradise.

Near the site of the present-day ferry landing, the doctor built a home secluded from the outside world. Stories circulated about strange operations that Dr. Sharpe was performing. Rumors abounded that he was conducting medical experiments involving the crossbreeding of humans and animals.

A serious threat to the doctor’s isolation came in 1937, when the state declared its intent to construct a road to the island. When Sharpe’s appeals to Raleigh were unsuccessful, he obtained a personal meeting with his old college roommate, President Franklin D. Roosevelt. After the meeting, the road project was halted.

Sharpe chronicled his ownership of Bear Island in his autobiography, Brain Surgeon.

By the late 1940s, he was an old man. Having enjoyed many years at his paradise, he decided to make a gift of the island to the Hursts. Mrs. Hurst, a former schoolteacher, prevailed upon him to donate the land instead to the North Carolina Teachers Association, the segregated black teachers’ group in the state. For approximately a decade, the black teachers used the island as a retreat, and other segregated black groups such as the Boy Scouts and the New Farmers of America visited the island for recreation. During that time, Bear Island fulfilled Sharpe’s dream of a “refuge and a place of enjoyment for some of the people whom America treated so badly.” Indeed, for a number of years, the island was one of the rare places on the coast open to blacks.

Access was always a problem in maintaining the island as a black retreat. Money was not forthcoming for a bridge. As racial barriers began to crumble in the early 1960s, most of the once-segregated associations and groups no longer existed as separate entities. Accordingly, Bear Island was presented to the state on May 3, 1961.

Attendance during the park’s premiere season was only four thousand, the lowest of all the parks in the state system. Although attendance has increased steadily since that time, the park remains one of North Carolina’s least-visited state parks, due in part to its limited access.

Even though Bear Inlet separates the island from the Marine Corps bombing range on Brown’s Island (Shacklefoot Island), the impact of the nearby military activities has been felt and seen at the park. A number of inadvertent bombings of Hammocks Beach have been reported in the past. In 1972, a 250-pound bomb was dropped on the island by a marine plane. Two years later, twenty-eight rockets were fired at the park by an off-course marine helicopter. No injuries resulted from either incident.

After visiting the park, return to N.C. 24 and continue in your original direction for 4.6 miles to the intersection with N.C. 172 at the community of Hubert, located on the boundary of Camp Lejeune Marine Corps Base. For a drive through the sprawling military complex, turn south on N.C. 172.

Four miles south of the intersection, marine sentries guard the entrance to the base. Although this 16.7-mile route follows a state-maintained road, windshield permits, provided by sentries, are required for all nonmilitary through traffic. Take care on the thirty-minute drive to follow the state highway or marked detours. During special maneuvers, portions of N.C. 172 are closed, and the resulting detours give motorists a better view of the installation. Extreme care must be taken to obey all traffic laws on the base, since violations are subject to trial in federal court.

Camp Lejeune stretches from the Atlantic Ocean inland to Jacksonville. Covering some 110,000 acres (172 square miles), it is known as the world’s most complete amphibious marine training base. Home to approximately 41,000 military personnel spread among five marine and two navy commands, the massive complex is used as a training and support base for marine expeditionary and amphibious operations. It also provides specialized engineering and supply schools for the Marine Corps.

With more than 6,000 buildings and 400 miles of roads, the installation is a city in itself. Its 205-bed naval hospital is the largest naval hospital in the South. Among the base holdings are Brown’s Island, Onslow Beach, and much of the New River. Brown’s Island is approximately the same length as adjacent Hammocks Beach State Park. Subject to repeated target practice, Brown’s Island is scarred with craters. Separated from Brown’s Island by Brown’s Inlet, Onslow Beach is an 11-mile-long barrier island used as a training ground for amphibious landings.

As war clouds were growing in Europe and the Pacific in early 1941, the United States recognized that the Marine Corps had outgrown its facilities at Parris Island, South Carolina, and Quantico, Virginia. As a result, the construction of a new base in Onslow County, North Carolina, was approved in February 1941. Defense Department officials selected the site because it met the needs of the marines: it had isolated surf and beach areas for training, a large, remote, undeveloped tract of land, a good climate, and a strategic location.

Originally known as New River Marine Base, the installation began as a tent city quickly assembled in 1941. Later, the base was renamed in honor of Lieutenant General John Archer Lejeune (1867–1942), commandant of the United States Marine Corps during World War I.

As the nation plunged deeper into World War II, the base played a vital role in training and supplying marines for the European and Pacific theaters. Veterans of the Pacific war zone were brought to Camp Lejeune to instruct new recruits and draftees in ship-to-shore assault. Others who trained here during the war included medics, Seabees, Coast Guard personnel, and women marines. Fittingly enough, Eugenia Lejeune, daughter of Commandant Lejeune, was commissioned at the base in November 1943.

Continue on N.C. 172 to the bridge over the New River, located just past the southern sentry station.

Twisting through the heart of Onslow County, the New River is an exceptionally beautiful coastal river. Approximately 40 miles in length, it rises in the northwestern part of the county. It is the only significant coastal river in the state that has both its headwaters and mouth in the same county.

Local tradition holds that the river was at one time a long lake in a swampy area. It became the New River when it overflowed into the Atlantic as a result of torrential rains.

After it leaves Jacksonville, where it dramatically widens on its course to the sea, the New River and its shoreline are owned almost entirely by the federal government as part of Camp Lejeune, thus depriving the public of enjoying their striking natural beauty. This bridge is one of the best places to view the New River.

The tour ends here, just beyond the boundary of Camp Lejeune.