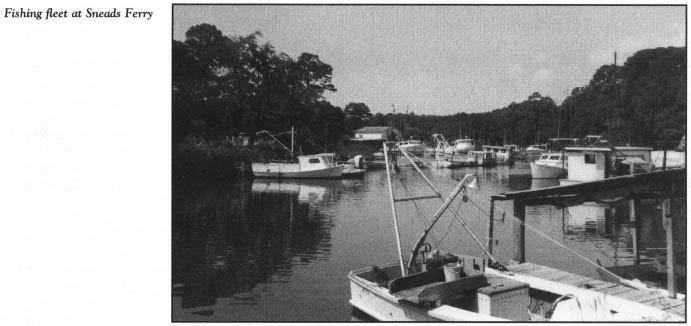

This tour begins on N.C. 172 just across the river from Camp Lejeune, on the southern side of the bridge over the New River. Drive south on N.C. 172. Just east of the highway lies the picturesque sound-side fishing community of Sneads Ferry.

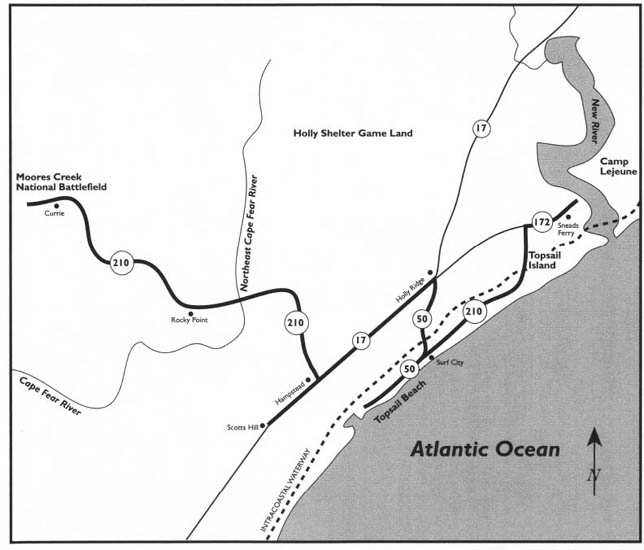

This tour begins on the mainland at Sneads Ferry, located on the southern shore of the New River. It then proceeds to Topsail Island, where it examines the entire length of the island from West Onslow Beach to Surf City to Topsail Beach. Back on the mainland, it visits Holly Ridge and skirts Holly Shelter Game Land and Angola Bay Game Land before heading to Hampstead and Scotts Hill. After approaching exclusive Figure Eight Island, it proceeds to Rocky Point and Currie, where it ends at Moores Creek National Military Park.

Among the highlights of the tour are the story of Operation Bumblebee, tales of buried treasure on Topsail Island, the story of Camp Davis, Poplar Grove Plantation, and Moores Creek National Military Park.

Total mileage: approximately 110 miles.

Approximately 1 mile south of the bridge, turn left, or east, on S.R. 1557 (Wheeler Creek Road) and proceed 0.3 mile to the intersection with S.R. 1517 (Fulchers Landing Loop Road). Bear right on S.R. 1517 and follow it as it winds its way south through Sneads Ferry.

Because of its proximity to New River Inlet, Sneads Ferry harbors a large commercial fishing fleet on its scenic waterfront.

The enormous shell mounds visible on the banks of the river are evidence that this area was an important Indian fishing site long before it was settled by people of European descent. Originally known as Lower Ferry, the village was later named for Robert W. Snead, who settled near the mouth of the river in 1760. He assumed operation of the New River Ferry from Edmund Emmett, who had established it in 1725. Snead, an attorney, gained notoriety throughout North Carolina when he shot and killed George W. Mitchell, a hero of the American Revolution, in a political quarrel at the Onslow County Courthouse. Although the cause of the confrontation has been lost to history, a superior-court trial resulted in Snead’s conviction. However, he came to his sentencing with a full pardon from Governor Richard Dobbs Spaight.

Sneads Ferry enjoyed a high volume of traffic in colonial times, because it was located on the first post road from Suffolk, Virginia, to Charleston, South Carolina. In 1775, news of the Battle of Lexington reached the area by a post rider galloping down the sandy trail.

Not until 1920 was the river ferry motorized. Nineteen years later, a drawbridge was constructed a short distance from the old ferry operation. In the 1990s, the existing high-rise bridge was constructed to replace the drawbridge.

After 1.4 miles, S.R. 1517 merges with S.R. 1515 (Sneads Ferry Road). Proceed west for 1.1 miles on S.R. 1515 to the intersection with N.C. 172. Turn south on N.C. 172 and drive 1 mile, then turn east onto N.C. 210.

Along this route, you will be greeted by a large variety of billboards advertising the amenities of Topsail Island, located 4.2 miles east. Topsail (pronounced Tops’l) is the first barrier island south of Bogue Inlet subject to commercial development. Twenty-two miles in length, the island is the longest on the North Carolina coast south of the Outer Banks. Despite its length, Topsail is only about 0.5 mile wide and covers only 15 square miles. Its oceanfront is an uninterrupted shoreline of white, sandy beaches. Portions of the sound side offer various trees, such as live oak, holly, cedar, and pine, along with scuppernong grapevines.

An unusual feature of Topsail is that it is shared by two counties, Onslow and Pender. The county line lies in the southern half of the island, just north of Delmar Beach. Traditionally, the southern portion—the Pender County portion—has been the more developed part of the island. Although touted by local realtors as “the last frontier in North Carolina’s coastal development,” Topsail has fallen prey to large-scale development in recent years.

N.C. 210 makes its way to the island over a high-rise bridge spanning the Intracoastal Waterway. Once on the island, turn north on S.R. 1568 and proceed to the northern end of Topsail.

Until a decade ago, this 5.2-mile stretch of beach, just north of West Onslow Beach, was virtually undeveloped. Now, condominiums and a towering hotel-conference center complex dot the oceanfront at a place called North Topsail Shores. Despite problems with highway erosion on this part of the island during coastal storms, continued rapid development here is almost a certainty for the future.

The pleasant drive “up” the beach offers an excellent opportunity to contemplate the island’s storied past. From the swashbuckling adventures of Blackbeard to a secret government missile-testing project, Topsail Island has had a fascinating history. Its earliest inhabitants, at least on a temporary basis, were Indians. Remains of a prehistoric Indian fishing camp a thousand years old were found during recent archaeological digs near New River Inlet, on the northern end of the island. During these excavations, various artifacts—including arrowheads, charred fire pots, and tools made from shells—were recovered.

As early as the eighteenth century, the island was known as Topsail. Historians have concluded that the name originated during the golden age of piracy. Some of North Carolina’s most infamous pirates, including Blackbeard and Stede Bonnet, frequented Topsail during that period. In the sound and the channels behind the barrier island, the buccaneers secreted their ships and lay in wait for unwary merchant ships. After news of their acts of piracy spread up and down the eastern seaboard, pilots gave the island close scrutiny in passing, scouring the western horizon for the sight of the tops of sails over the island dunes. Thus, the name Topsail Island was born.

The first permanent settlers in present-day Pender County arrived in the latter part of the seventeenth century. Onslow County was settled in the early eighteenth century. However, these settlements were confined to the mainland along the rivers and sounds. Topsail Island did not attract a significant permanent population until after World War II.

During the Civil War, Topsail was an important source of badly needed salt. Not surprisingly, the island was the scene of a number of daring raids by Union forces seeking to destroy the saltworks, which processed the scarce commodity from salt water.

Before World War II, the only access to Topsail was by boat. In the early stages of the war, at the nearby mainland community of Holly Ridge, the federal government began constructing Camp Davis, an enormous antiaircraft training facility. As part of the massive installation, the island was considered a vital link in coastal defense and was leased by the government. Topsail was promptly connected to the mainland by a pontoon bridge. Barracks, warehouses, and other military structures were erected on the island.

At the close of the war, Camp Davis was deactivated, but the existing facilities on Topsail were immediately put to another use. The United States Navy selected the island as a testing ground for the nation’s early defense-missile project, Operation Bumblebee. Chosen because it offered an isolated area for missile tests, Topsail served as the site for the program from its infancy until it was moved to Cape Canaveral, Florida, and the Mojave Desert in California in 1948.

In 1949, when the military no longer had need of the island, it was released to its owners, who wasted no time in converting the existing structures into resort facilities. Two years later, Topsail Island had its first incorporated town: Surf City.

Although minor residential development began on the island in the 1930s, the early 1950s saw the southern half transformed into a family-oriented coastal resort. Unfortunately, Topsail had the same fate as did most of the other barrier islands along the southern half of the North Carolina coast in 1954, when Hurricane Hazel left her deadly calling card. Before the ferocious storm pounded the island, 230 buildings were standing. In the wake of the hurricane, 210 were completely demolished, while the remainder were damaged. To make matters worse, the storm stripped the island of a vast amount of sand and destroyed the only bridge to the mainland. In subsequent years, two other hurricanes, Diane and Donna, raked Topsail and caused serious damage.

The 1960s brought a much-needed reprieve from devastating storms. In 1963, Topsail gained a second incorporated town when Topsail Beach was chartered on the southern end of the island. Since that time, development has escalated rapidly. Now, “the last frontier”—the island’s northern quarter—is considered ripe for development.

From the northern end of Topsail, retrace your route on S.R. 1568 to the point where the island tour started. Here, S.R. 1568 merges into N.C. 210 on its southern route down the island.

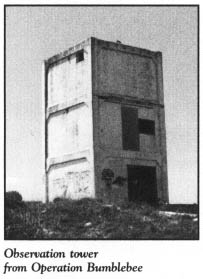

Some 1.5 miles south of the junction, a multistory rectangular structure decorated with graffiti towers over the Atlantic on an undeveloped portion of the strand. Over the past three decades, the island’s best-known landmarks have been eight of these concrete towers, arranged approximately every 2.5 miles along the strand. Ever since Topsail was opened for resort development, tourists driving the island from West Onslow Beach to Topsail Beach have been puzzled by the unusual structures.

Because the island was off-limits to civilians when the towers were erected, legends have arisen about their original purpose. One theory suggests that the towers were constructed for the observation of enemy submarines during the war. A more glamorous notion that they were part of the nation’s early space program also became popular.

In reality, the concrete platforms stand as virtually the only visible reminders of Topsail’s greatest secret. Operation Bumblebee remains shrouded in mystery, most of its details buried in military records which are either classified or almost impossible to locate.

The facts that are known about the project are fascinating. As World War II drew to a close, Topsail was selected as the site of the incubation phase of the nation’s newest secret project: ramjet propulsion and its application to defense missiles. As a result of the tests conducted on the isolated shores of Topsail, the world’s first supersonic missiles, designed to protect an entire fleet of warships, were developed.

Scientists from Johns Hopkins University, working in conjunction with the United States Navy, first came to the island in the summer of 1945 to assess the suitability of the site. By the following year, electricity, streets, and water and sewer facilities were in place on the island. Personnel, including two hundred workers employed by a defense contractor, lived in old military barracks.

The construction of the missiles took place in a building on the sound side of the island. Dollies then moved the missiles through underground tunnels to launch pads on the oceanfront.

In the fall of 1946, the first test missiles were fired. Ranging in length from three to thirteen feet, they were tracked from the eight now-famous towers. Several underground bunkers were also constructed to provide safer observation areas.

Although some area residents claim that money, politics, and the desire to market the island as a resort forced the project to be moved from Topsail in 1948, it appears that the change was dictated by increased ocean traffic in the firing range, which extended 20 miles in a northeasterly direction.

Over the decades, most of the observation towers have been converted to private residences. Another has become the entrance to a fishing pier. Several others, like the one at the present tour stop, stand as abandoned monuments to the fleeting moment when, unbeknownst to the outside world, Topsail was the place where a prototype weapon that forever changed military strategy was being developed.

There are few structures surviving from the missile project. In the 1980s, a construction crew inadvertently unearthed a hidden reminder of the abandoned testing site. While installing a new sewer line, they discovered a portion of the underground tunnel connecting the assembly area to the oceanfront launching area. The large concrete-block structure on the sound side of the island that served as the assembly building for the missiles was transformed into a nightclub several years ago.

Continue south on N.C. 210. It is approximately 7 miles from the concrete tower to Delmar Beach, located just north of the Pender County line. This small beach town is dominated by a large number of mobile homes in various states of repair.

One mile south of Delmar Beach, at the crossroads where N.C. 210 becomes N.C. 50 near the drawbridge spanning the Intracoastal Waterway, lies Surf City, the commercial hub of the island. With a permanent population in excess of five hundred, the town is the most populous place on the island.

Much of the mystique of the North Carolina coast comes from tales of buried treasure. Topsail Island, and specifically the Surf City area, is believed to be the site of a number of treasures, either ill-gotten booty hidden by pirates or the cargoes of ships that wrecked centuries ago.

Stede Bonnet—“the Gentleman Pirate”—apparently found Topsail to his liking. He sailed from Old Topsail Inlet in 1719 on an adventure that netted him a dozen ships. Speculation about the ultimate disposition of the loot taken on this spree has centered around Topsail Island. Legend has it that Bonnet’s treasure was buried on the Pender County side of the island. Two of Bonnet’s ships went down in Topsail Sound when he was double-crossed by Blackbeard.

Whether any of Topsail’s treasure has ever been recovered is unknown. This century has seen a number of serious and expensive attempts to locate it.

Perhaps the first—and undoubtedly the most extensive—effort began in 1938, when a group of men from New York City formed the Carolina Exploration Company and attempted to recover the riches of an old pirate ship. After leaving the mainland village of Hampstead, the treasure hunters moved their equipment—including a new invention, the metal detector—across the sound by boat. Once on Topsail Island, the group, armed with old maps and charts, put the metal detector to work. Signals from their equipment revealed the presence of metal beneath the sands of Topsail. Excavation rights on the island, which was virtually uninhabited at the time, were obtained from Topsail’s owner, Harvey Jones.

From their initial exploration, the New Yorkers ascertained that the ship they were seeking was much deeper under the sand than they first imagined, and that its location was ninety feet inland from the existing Topsail shore. They dug a gigantic, funnel-shaped hole measuring seventy feet across into the island. Sections of sheet metal were installed in the shaft to form a cofferdam around the digging pit.

Gradually, old ship timbers were pulled to the surface by pressure pumps. Whether anything else was raised from the shaft is known only to the explorers, because they, like most treasure hunters, were secretive about their find. By the time the project was abandoned in 1939, it was estimated that fifty thousand dollars had been poured into the venture.

The pit, which thereafter became known to locals as “the Old Pirate Ship Treasure Pit,” soon filled with water. Later, a lead weight dropped into the mine revealed that the hunters had probed at least thirty-one feet below the water level.

Located 2 miles south of Surf City, the remains of the excavation site endured for many years.

Spanish galleons laden with gold, silver, and other precious commodities from the New World customarily sailed along the North Carolina coast on their return trip to their mother country. Such was the case on August 17, 1570, when somewhere near Topsail, a Spanish fleet of five ships bearing chests full of valuables encountered a savage hurricane. Driven close to the deadly shoals of the barrier island, the crews fought valiantly to keep their vessels afloat. However, the first of the ships to be lost, the El Salvadore, slammed ashore at Topsail with a loss of most of her crew and 240,000 pieces of eight. Within two years, the wreck was covered by more than seven feet of sand.

Approximately 1 mile south of the 1938–39 treasure hunt, a different search subsequently took place on the ocean side of the island. There, metal detectors were used in an attempt to locate the remains of the El Salvadore. This event was dubbed “the Old Spanish Galleon Treasure Hunt” by locals.

After the expensive search, the only evidence left at the scene was a round iron caisson embedded deep in the sand. Again, it is not known what the searchers discovered, but a fifty-five-foot sounding line lowered into the abandoned shaft failed to reach bottom.

With the recent development of the island, it appears that any treasure hidden under the sandy surface of Topsail will remain buried there forever.

The 8-mile stretch from Surf City to the southern end of Topsail is the final leg of the island tour. Over the past forty years, cottages of all sizes and shapes, fishing piers, motels, campgrounds, restaurants, and small shopping centers have sprung up along this route.

Follow N.C. 50 to Topsail Beach, which serves as a bookend to Surf City. Topsail Beach has a smaller permanent population than its northern neighbor, but it offers a variety of amenities for vacationers on the southern part of the island.

A tangible reminder of Operation Bumblebee is visible at the Jolly Roger Motel, located on the oceanfront in the heart of Topsail Beach. A close inspection of the motel patio reveals that it was once a concrete launching pad.

Retrace your route to Surf City and leave the island via N.C. 50. It is 6 miles west from Topsail Island to Holly Ridge, located at the intersection with U.S. 17.

Holly Ridge is a small village to which history has not been kind. Every year, untold thousands of coastal visitors pass through this Onslow County town without so much as a second thought about the place. After all, from outward appearances, Holly Ridge, with a population of less than seven hundred, seems to be nothing more than a crossroads settlement with several convenience stores and gas stations.

However, the town is not without its past glory. If you care to take a brief trip around the side roads of the community, you will notice abandoned military buildings dotting the landscape. You may be distracted by numerous paved roads which suddenly disappear into nowhere in nearby forests. Although it may seem that you have entered a twilight zone, these ghosts of the past are remnants of one of the largest military bases ever constructed in the state: Camp Davis.

Holly Ridge was established around 1890 to serve as a wood station for the railroad. The town was named for the holly that once grew in profusion in the area. Holly was once shipped from the town each Christmas season. By 1980, one lone holly tree survived, and it was in sickly condition.

Holly Ridge’s claim to fame began in 1940, when the federal government authorized the construction of an antiaircraft training base in the tiny village of twenty-eight persons. An appropriation of $9.5 million was used to begin construction of an initial complex of a thousand buildings. By the time the installation was ready for troops in April 1941, approximately $40 million had been spent on the project.

Only five voters participated in the initial municipal election in Holly Ridge in 1941, but within five months and ten days of that date, the sleepy little village was transformed into a metropolis of over twenty thousand residents.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 brought the first year of operations at the base to a chilling close. Nearly a hundred thousand people were by then living in the area.

Named in honor of a native North Carolinian, Major General Pearson Davis (1866–1937), the camp encompassed 3,200 acres extending from the Atlantic westward. An additional 50,000 acres were used for training and firing practice. The size of the facility was mind-boggling. More than 2,000 buildings were ultimately erected at the base. Among these were a large power plant, water and sewer plants, a laundry that employed 450 workers, and a 2,000-bed, 56-building hospital unit. Two airports, 3 fire stations, 223 fire hydrants, 830 street lights, 50 miles of water mains, and 30 miles of paved streets were included in the complex. To meet the demands of the military personnel, 4 movie theaters and 8 churches were built in Holly Ridge almost overnight.

Almost as suddenly as it came to Holly Ridge, Camp Davis left. As World War II came to an end, there was no longer a need for the enormous training facility. In October 1944, the camp was closed, only to be reopened for a short time during the summer of 1945 as an air-force convalescent hospital and redistribution center. Most of the buildings that once made up the base were subsequently torn down or removed to other locations.

Today, the seemingly endless miles of blacktop that disappear into the wilderness surrounding the village and the unmistakable military buildings on the side streets bear mute testimony to the future which Holly Ridge might have enjoyed.

At the highway intersection in Holly Ridge, turn south on U.S. 17. Two expansive game preserves comprised of pocosins, swamps, and wetlands are located south and west of Holly Ridge. A portion of the larger preserve, Holly Shelter Game Land, borders the western side of U.S. 17 on this portion of the tour.

Approximately 10 miles long and 7 miles wide, Holly Shelter covers more than 48,500 acres. A shrub pocosin virtually devoid of trees dominates the northeastern part of the preserve. In contrast, the southeastern section features higher elevations and longleaf pines. In the northwestern quadrant, Carolina bay plants such as titi thrive near bald-cypress wetlands. A significant, rare stand of Atlantic white cedar grows near Trumpeter Swamp.

To visitors and area residents alike, the Holly Shelter preserve remains a forbidding place. Stories abound about people who have vanished without trace in this immense wilderness. So remote and untouched is it that an 0-47 observation plane from Camp Davis that crashed in 1943 was accidentally discovered in 1978 by a marine colonel in a flight over the area.

Lieutenant Herbert Evans, one of the survivors of the World War II crash, was able to find his way out of the swamp only after walking for six hours through dangerous, snake-infested water that was at times waist-deep. His wife picked thorns out of his body for two months after the ordeal. Evans had this to say of Holly Shelter: “You can’t imagine what a beastly place that swamp was.” That impression has been shared by many others who ventured into the wilderness.

There is no road access to the smaller of the two preserves, Angola Bay Game Land, which lies some 8 miles north of Holly Shelter. Encompassing 21,134 acres in Pender and Duplin counties, Angola Bay is a remote, primitive area that is almost inaccessible to humans. During dry seasons, the large peat beds underlying this vast expanse are highly combustible.

Some years ago, an attempt was made to build a road through Angola Bay. A canal was dug as part of the process, and the peat and muck extracted from it were piled up to make the roadbed. Before the streams in the vicinity could be bridged, the roadbed caught fire and burned down. When the area was part of Camp Davis, roads were constructed in the great morass. To prevent them from burning, the army kept them soaked with water from dammed-up roadside canals.

Both Holly Shelter and Angola Bay are administered by the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission. The lands in the preserves have been set aside for hunting and wildlife management. Deer, bear, and alligators are prevalent in both areas, as are insectivorous plants such as Venus’ flytrap, pitcher plant, and trumpet flower.

It is 12 miles on U.S. 17 from Holly Ridge to Hampstead.

“Ocean Highway,” as U.S. 17 is called, passes through a number of small, quaint coastal villages as it runs the length of the North Carolina coast from South Mills in the north to Shallotte in the south. None of these villages is more charming than Hampstead. Adorned with huge, ancient, moss-draped oaks along the roadway, this fishing hamlet presents a visual delight to motorists.

Although the present population is less than a thousand, Hampstead’s roots can be traced to colonial times, when the village was a commercial center for fishermen, planters, and farmers. During the Civil War, salt production was important to the community, with the valuable product bringing as much as fifty dollars a bushel. Due to its proximity to the Atlantic, the Intracoastal Waterway, and Topsail Sound, the community has been able to maintain its maritime flavor in the present era.

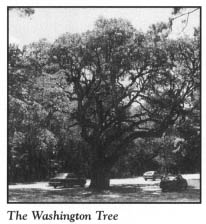

One significant part of Hampstead’s past is visible on the western side of U.S. 17. On his 1791 tour of the South, President George Washington stopped for a rest under one of the tall, sweeping oaks in the village. That tree, still standing today, has been appropriately marked by the Daughters of the American Revolution as the Washington Tree.

Hampstead hosts an annual festival to celebrate one of the most abundant food fish in North Carolina. The Hampstead Spot Festival, held during the first week in October, offers a variety of activities. Although spots were caught commercially as early as the 1930s, they did not become the largest-selling fish in the South until twenty years later. Because of the popularity of the distinctively marked fish, which have a black spot on each side near the gills, several seafood packing houses have been built in the village. In order to raise money for local projects and to call attention to Hampstead’s claim of being “the Seafood Capital of the Carolinas,” the festival was inaugurated in 1964.

Continue 4 miles south from Hampstead to Scotts Hill.

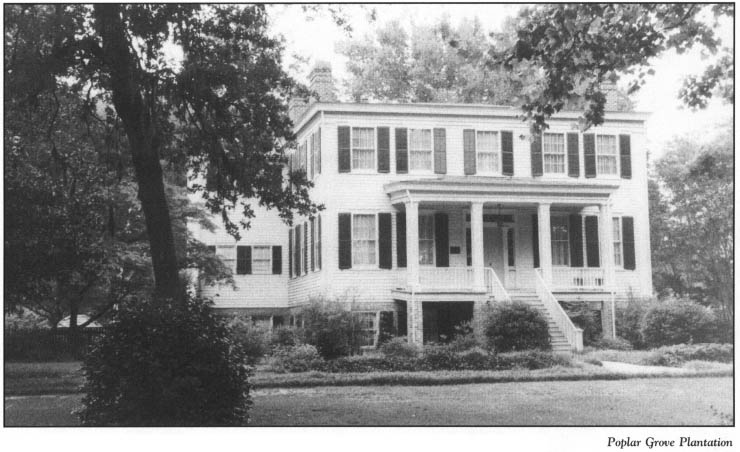

Located on the eastern side of U.S. 17 in the village is Poplar Grove Plantation. Purchased in 1795 by James Foy, Jr., the son of a Revolutionary War patriot, this is one of the oldest peanut-producing plantations in the state. At one time, the estate stretched from Topsail Sound to the present route of U.S. 17 and covered more than 835 acres.

After passing through six generations of the Foy family, the plantation manor house and the adjacent fifteen acres have been opened to the public by a nonprofit corporation, Poplar Grove Foundation, Inc. The plantation is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Without question, the centerpiece of the plantation is the Greek Revival manor house. Joseph M. Foy built the multistory frame structure in 1850 to replace the original plantation house, which had burned a year earlier. The wood used in the present house was hand-hewn and pegged, and the bricks in the foundation and chimney were made on the grounds. Situated among stately oaks festooned with Spanish moss, the house boasts many of the features found in fine Wilmington homes of the same period. The furnishings and exhibits in the house date to the early and middle years of the nineteenth century. The three floors contain four rooms each, arranged around a central hallway connected to the next floor by a straight stairway.

Tours of the house and its outbuildings provide visitors with a glimpse of what plantation life was like in the antebellum South. In 1860, the prosperous plantation yielded more than five thousand bushels of peanuts. Raiding Union forces looted horses and food in 1862.

During your tour of the manor house, you may hear the tale of one member of the Foy family who still considers the plantation her home. Aunt Nora, the wife of Joseph M. Foy, is the subject of a colorful ghost story.

Nora moved into the house as a young bride after the Civil War. A windowpane bears her name, along with that of her husband, etched there on their wedding day. Nora later served as the local postmistress. Before her death in 1923, she apparently became a colorful character, prone to cracking jokes and smoking a pipe. Since her death, her presence lingers. She has been heard walking about in her upstairs room. Members of the plantation staff refer to her as Aunt Nora. They have reported tricks she has played on them. Around the Christmas season, a mysterious glow sometimes emanates from the window of her room after all the lights of the house have been turned out.

Complementing the fine manor house and outbuildings are the beautiful gardens and grounds of the estate. Stately oaks, sycamores, and poplars lend their shade to the plantation, while seasonal flowers are ablaze with color throughout the year.

Continue in your original direction on U.S. 17. Three miles south of Poplar Grove, you will notice a sign for Figure Eight Island. Turn east onto Porters Neck Road. After 1.1 miles on Porters Neck, turn south onto Edgewater Club Road, which terminates near the Intracoastal Waterway after 1.4 miles. Across the bridge lies magnificent, 5-mile-long Figure Eight Island. Blessed with maritime forests and high, rolling sand dunes covered with sea oats, Figure Eight Island is one of the most beautiful developed barrier islands on the North Carolina coast.

Unless you are an owner of property on the island or an invited guest, your chance of visiting this, the most exclusive of all the developed barrier islands in the state, is remote at best. Security is tight, and the bridge is manned by tenders around the clock.

Some 250 homes have been constructed on the island, and they are among the most beautiful on the entire coast. Most have been placed well back from the beach in forested areas. Prior to construction, all building and site plans must be reviewed and approved by an architectural review board. The resulting homes are aesthetically pleasing structures that carry price tags upwards of a million dollars. At the elegant Figure Eight Yacht Club, members dine in luxurious surroundings. The island has no hotels.

James Moore, the brother of “King” Roger Moore of Orton Plantation in Brunswick County, was the first recorded owner of the island. In 1755, Cornelius Harnett, Jr., the famous Cape Fear patriot, acquired it. It is highly probable that neither of these owners ever walked on the island.

In 1795, after Harnett’s death, the island was purchased at an auction of his estate by James Foy. Thus, Figure Eight became part of Poplar Grove Plantation. It remained in the Foy family for the next 160 years and was known for a time as Foy Island or Woods Beach. Legend has it that the present name came from mariners who perceived that they were sailing in a figure eight as they navigated their vessels through the channel.

In the mid-1950s, after the devastation caused by Hurricane Hazel, the value of coastal property in the Cape Fear area plummeted. In 1955, Figure Eight was sold by the Foy family and the Hutaff family—who had earlier obtained the southern portion of the island—to two Wilmington businessmen. The purchase price of a hundred thousand dollars pales in comparison with the current price of a single oceanfront lot, which is more than twice that amount. Since 1971, the island has been sold several times to corporate developers.

Retrace your route to Hampstead. Turn west off U.S. 17 onto N.C. 210 for a drive through the Pender County countryside. As is evident from the farmland on both sides of the highway, Pender is an agricultural county. However, much of its land is very flat and poorly drained.

Twelve miles northwest of Hampstead, N.C. 210 crosses the Northeast Cape Fear River at a point called Rocky Point. In 1663, Barbadian explorers gave the place its name in honor of the unusual outcropping of rock in an otherwise flat area. Rocks have been quarried from this massive outcropping for more than 125 years. When New Inlet was closed after the Civil War, stone quarried from Rocky Point was used in the project. (For more information on the closing of New Inlet, see The Wrightsville Beach to Pleasure Island Tour, pages 244–45.)

Continue 2.2 miles to the community bearing the name of the outcrop. Settled in the second half of the eighteenth century, Rocky Point was the home of many distinguished North Carolina families during the colonial period: the Lillingtons, the Swanns, the Ashes, and the Moores.

It is approximately 14 miles from Rocky Point to Currie, the small crossroads village that is home to Moores Creek National Military Park. To reach the eighty-six-acre complex, continue 1 mile past Currie on N.C. 210.

In order to preserve the site of what some experts consider the first decisive patriot victory of the American Revolution, the North Carolina General Assembly purchased the battlefield in 1898 and created a state park. By an act of the United States Congress on June 2, 1926, Moores Creek National Military Park was established when North Carolina donated the site.

Rising in northwestern Pender County, Moores Creek flows in a southeasterly direction until it merges into the Black River, a tributary of the mighty Cape Fear. During the eighteenth century, the creek was also known as Widow Moores Creek, because it flowed past land owned by the widow Elizabeth Moore.

On February 27, 1776, a bitterly cold day, this creek was the scene of a short battle that helped determine the fate of the young American nation. The Battle of Moores Creek Bridge was the first battle of the American Revolution fought in North Carolina, and it resulted in a decisive victory for North Carolina patriots over North Carolina loyalists.

Revolutionary fervor in the colony caused Royal Governor Josiah Martin to flee North Carolina in mid-1775. In January 1776, while in exile, Martin formulated a plan to reestablish royal control of the colony. On January 10, he issued a call for loyal subjects to assist in putting down the rebellion.

Within a month, some sixteen hundred Highland Scots, Regulators, and Tories assembled at Cross Creek (present-day Fayetteville). These troops, under the command of General Donald MacDonald and Lieutenant Colonel Donald McLeod, were to march to Brunswick Town on the Cape Fear River, where they would meet up with a British expeditionary force from Ireland and New England. Together, these forces would be of sufficient number to bring the colony back in line.

Months before Martin’s call for troops, North Carolina had raised two regiments for the Continental Army, along with several battalions of militiamen. While the loyalists were making their plans upriver, Colonel James Moore, the commander of patriot forces in southeastern North Carolina, was designing a grand strategy to foil the enemy’s scheme.

When MacDonald’s loyalists began their march toward the coast, their route was blocked by Moore’s troops. MacDonald quickly changed his course by crossing the Cape Fear en route to a point known as Corbetts Ferry on the Black River, where he hoped he could slip past Colonel Richard Caswell’s militiamen approaching from New Bern. From Corbetts Ferry, MacDonald planned to lead his men over the bridge at Moores Creek and on to Wilmington.

The loyalists reached Corbetts Ferry first, so Moore dispatched Caswell and his patriot troops to Moores Creek. Additional men under Colonel Alexander Lillington were sent to reinforce Caswell’s forces.

On the night before the battle, Lillington camped on the eastern side of Moores Creek with approximately 150 men, while Caswell camped on the western side with some 800 men. Colonel Moore and 1,000 troops were located halfway between Moores Creek and Wilmington.

The loyalist force of 1,500 men camped 6 miles from Caswell on the same side of the creek. Cognizant of Caswell’s exposed position, General MacDonald convened a council of his officers, at which it was decided that an attack should be launched. When MacDonald suddenly fell ill, command was turned over to Colonel McLeod.

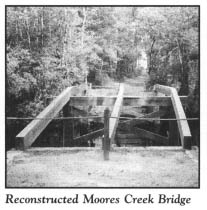

At one o’clock in the morning on February 27, McLeod and his army began their slow march through the swamps in the bone-chilling cold. About an hour before first light, they reached Caswell’s camp, which to their surprise was abandoned. During the night, Caswell had withdrawn his forces to the other side of the creek, but campfires had been left burning so as to deceive the enemy. After crossing the creek, Caswell removed the planks from the bridge and greased the girders. At his new position, he threw up a breastwork and placed artillery to cover the road and bridge.

The loyalists regrouped at Caswell’s abandoned camp and waited for day-light to pursue the rebels, whom they thought were in retreat. However, approximately a thousand patriots were waiting, anxious to fight, on the opposite side of the dismantled bridge.

At sunrise, musket fire suddenly interrupted the calm. When the attack began, the loyalists yelled, “King George and broadswords!” While 500 men, broadswords in hand, rushed the bridge, bagpipes played in the background. A small contingent of men made their way across the slippery remnants of the bridge, but they were annihilated as they approached the patriot breastwork. Loyalist losses totaled 80 killed or wounded, while the patriots lost one man, who died from wounds four days later. The battle was over in three minutes. Within two weeks, the retreating loyalists were captured, along with 1,600 rifles, 150 swords, and 15,000 pounds in gold.

One immediate result of the victory was the permanent end of royal authority in North Carolina. Even more significantly, the victory prompted North Carolina to become the first colony to direct its delegates to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia to vote for independence.

Because of the loyalist defeat at Moores Creek Bridge, the British invasion of North Carolina was thwarted until the waning stages of the war. Historian Edward Channing summed up the importance of the battle when he wrote, “Had the South been conquered in the first half of 1776, it is entirely conceivable that rebellion would never have turned into revolution…. At Moore’s Creek and at Sullivan’s Island [in South Carolina], the Carolinians turned aside the one combination of circumstances that might have made British conquest possible.”

The patriot victory at Moores Creek was a story of heroes.

Richard Caswell was later rewarded for his contribution to the victory when he became the first elected governor of the independent state of North Carolina.

There was also a little-known hero, Private John Colwell. While the patriots were reloading their rifles, the loyalist troops who had made it over the bridge were fast approaching. A wet fuse on the patriot cannon had foiled several attempts at firing. As the enemy neared, Private Colwell pulled a red-hot stick from the campfire and lit the fuse. The resulting cannon blast decided the battle.

There was also a heroine.

As Ezekial Slocumb marched from his farm with eighty men to join Colonel Caswell’s forces, he took with him a great wool coat which his young wife, Mary “Polly” Slocumb, had made for him. A terrible dream disturbed Polly’s sleep on the second night after Ezekial left. In the nightmare, she saw a bloody body wrapped in the coat she had made. In desperation, she informed her servant, “Something dreadful has happened to Ezekial. Keep the baby, I’m going to find him.”

Polly hurried to the barn, where she mounted her fastest horse and sped off into the night. Having covered 30 miles before daylight, she continued until she heard the cannon fire at Moores Creek Bridge. While she paused to rest under a tree, her dream became reality, as she noticed a bloody soldier in a nearby ditch covered with her husband’s cloak. When Polly reached the man, she pulled back the cloak and cleaned the blood from the soldier’s face. The man was not Ezekial! Still, Polly lingered to provide him water and comfort.

Soon, she was caught up in rendering aid to the wounded soldiers around the battlefield. She obtained water from a nearby stream and fashioned bandages from strips torn from her petticoat. A bloody and battered Ezekial was astonished to find his wife on the battlefield, where she remained into the night. Finally, about midnight, Polly mounted her trusty horse for the 50-mile ride through the swamps to her home.

Today, a monument honoring Mary “Polly” Hooks Slocumb stands in the park.

Tours of the park begin at the visitor center, which offers an audiovisual program covering the historical background of the battle. Interesting exhibits and dioramas are laid out in the museum.

On the battlefield itself, the Battlefield Trail complex begins with the History Trail, located west of the visitor center. This route winds for 1 mile through Spanish moss-laden pines and hardwoods to the bridge, located about 0.4 mile from the trailhead. Numerous historical monuments and markers have been erected along the way. Constructed in 1857, the Patriot Monument, or Grady Monument, is the oldest stone monument in the park. It honors Private John Grady, the only patriot killed in the battle.

Near the bridge, a boardwalk crosses the creek to a trail that leads to Richard Caswell’s campsite. This route makes its way through terrain often blanketed with the yellow of Carolina jasmine and the blue of clematis. Pitcher plants, sundews, and Venus’ flytraps may also be found along the trail.

Near the visitor center, Tarheel Trail, a circular trail 0.3 mile in length, branches off from History Trail. Along this path, exhibits chronicle the history of naval stores, the chief industry of the Cape Fear region at the time of the battle.

Although no camping is allowed in the park, there is a sheltered area for picnics on the grounds.

The tour ends here, at Moores Creek National Military Park.