This tour begins at the intersection of N.C. 133 and N.C. 87 at Boiling Springs Lakes. Proceed south on N.C. 87 for 2.1 miles to the Nuclear Visitor Center.

This tour begins by exploring Southport, then travels by private ferry to Bald Head Island, where it ends with a walk to legendary Cape Fear.

Among the highlights of the tour are the Nuclear Visitor Center outside Southport, Waterfront Park on the Cape Fear River, the story of Fort Johnston, the homes of the Southport Historic District, “The Grove,” the story of Tony the Ghost, Old Baldy on Bald Head Island, the story of Stede Bonnet’s buried treasure, and the story of the disappearance of Theodosia Burr Alston.

Total driving mileage: approximately 10 miles.

In the 1970s, Carolina Power and Light Company completed construction of a two-unit nuclear power plant on the outskirts of Southport. Unit 2 began commercial production of electricity in 1975, and Unit 1 went on line two years later. The plant towers over the sleepy, historic village. Each night, its lights cast an eerie yellow aura in the sky over Southport.

Even before the Brunswick County plant was completed, its safety and security were challenged by various environmental groups. And since it began production of electricity, the facility has been plagued by equipment failure and safety mishaps. Concern over plant safety has forced a series of reactor shutdowns.

Despite the controversy surrounding the plant, Carolina Power and Light Company has attempted to be a good corporate citizen in the Southport area. In an effort to educate the public about nuclear energy and to allay some of the fears and misconceptions about it, the company opened the visitor center in 1972, before either of the two reactor units was completed. Each year, some ten thousand visitors tour the center, which features numerous colorful exhibits on a variety of energy-related subjects.

A model of the Brunswick County plant holds a prominent spot in the center. Although the actual plant is not open for tours, a videotaped tour can be viewed in the small theater at the center. Visitors can get a good look at the exterior of the massive facility from the observation deck.

Proceed 1.2 miles south on N.C. 87 to its intersection with N.C. 211 just north of the corporate limits of Southport. The nuclear plant on N.C. 87 and the shopping center at this intersection combine to present the deceiving appearance that Southport has exchanged its historic treasures for symbols of the modern age. Yet the real Southport will soon reveal itself. Turn left, or south, on N.C. 211 (Howe Street) and follow it for 1.6 mile to its terminus at the parking lot on the picturesque waterfront.

Southport has never been a pretentious town. Never mind that its ancient streets and its waterfront have been witness to numerous events of historic significance. Never mind that its scenic harbor is considered among the most beautiful in America. And never mind that, in recent years, the town has been consistently rated by Rand McNally among the top twenty places to retire. Life goes on for Southport’s thirty-eight hundred residents without flair or flamboyance.

The town’s beautiful waterfront is a working harbor where commercial fishing boats dock every afternoon from expeditions into the open sea, and where river pilots await calls to gently usher oceangoing vessels into the Cape Fear channel, just as their predecessors did for more than two centuries.

Southport has refused to trade its charm, its heritage, and its maritime flavor for uncontrolled growth. Visitors who come to town after a fifty-year absence will find it little changed today. A majority of the houses that line Howe Street, the main north-south thoroughfare, and Bay Street, the panoramic waterfront avenue, look much as they did a half-century ago. Moore Street, the old commercial district, remains a viable place of commerce.

From the foot of Howe Street, the waterfront is a breathtaking sight. Few coastal towns anywhere are blessed with a waterfront that can compare in charm and beauty to that of Southport, located where the waters of the mighty Cape Fear River meet the Atlantic.

Waterfront Park, a municipal park located adjacent to the Howe Street parking lot, overlooks the Cape Fear and affords visitors an opportunity to enjoy the splendor of the river. Its grassy banks and pavilions are ideal for picnics. Tall palm trees lining nearby Bay Street lend a tropical flavor to this riverfront oasis.

A popular fixture of Waterfront Park is historic Whittler’s Bench. For as long as anyone can remember, a wooden bench has been nestled under the shade of several old trees at this spot. While gazing upon the waterways of Southport, countless generations of local residents have rested here, whittled, and swapped tall tales.

Another popular attraction at the park is the City Pier. Though not as long as the ocean fishing piers on the barrier islands, this municipally owned pier is an excellent place from which to view the riverscape and the wide assortment of water traffic passing into and out of the river. On the horizon looms Bald Head Island, where Old Baldy, the oldest lighthouse in the state, towers above the island landscape. To the west, the remains of Fort Caswell and the Oak Island Lighthouse, the newest lighthouse in the state, are visible on the eastern end of Oak Island.

From large ocean liners making their way to and from the port at Wilmington to pleasure yachts plying the Intracoastal Waterway, the traffic on the Southport waterfront is always heavy. Park visitors may first notice an approaching ship as it looms over the buildings of Oak Island. As the ship makes the turn into the Cape Fear, visitors may sense that it is on a collision course with Battery Island in midriver, until it suddenly makes a course adjustment into the well-defined shipping lane.

Located along the waterfront between the picnic area and the pier is an old, crumbling rock wall now covered with masonry and debris. This wall is all that remains of the original fortifications of Fort Johnston, the first fort authorized by the colonial assembly of North Carolina. Now reduced to six acres, old Fort Johnston may well be the smallest military installation in the nation.

There is one significant reminder of the old fortress: the much-altered commandant’s house and officers’ quarters, constructed around 1800 and located across East Bay Street from the City Pier. From its commanding position on East Bay Street overlooking the river, the large brick building is one of the most imposing historic structures in Southport. Its two-story central block is joined on either side by one-story wings.

In 1990, a group of influential Southport citizens began a movement to have Fort Johnston returned to the state as a historic site, yet the old building continues to be used as living quarters for the commander and other officers of the military installation at nearby Sunny Point. At present, the public can walk upon the grounds of Fort Johnston, where several historical markers have been erected.

Southport celebrated its bicentennial in 1992. However, its roots can be traced back almost 250 years, to the construction of Fort Johnston. Although the British Crown ordered the fort’s construction in 1730 to protect the Cape Fear from attack by Spanish privateers and pirates, work did not actually commence on the fortification until 1745, under the administration of Royal Governor Gabriel Johnston. Within a decade, the project was virtually complete. By that time, a small community of merchants, river pilots, and fishermen had settled in the shadows of the fort. Southport emerged from this early community.

Because the Cape Fear region was a hotbed of revolutionary fervor, Fort Johnston played a prominent role in the events leading up to the war for American independence. The culmination came on the morning of July 18, 1775, when Josiah Martin, the exiled royal governor of North Carolina, scrambled from his berth and watched in horror from the deck of the British man-of-war Cruizer as a band of patriots led by Cornelius Harnett and John Ashe raided and burned the fort.

In the years following the war, the community surrounding the ruins of the fort served as the base of operations for a new generation of river pilots, who sailed out into the ocean in search of ships bound for the Cape Fear. Once a bargain was reached for their services, the pilots guided the ships safely around the hazardous shoals and other dangers in the river.

Efforts to incorporate the community around Fort Johnston succeeded in 1792, when 150 acres were set aside for the establishment of the village of Smithville. Named for Benjamin Smith—a notable soldier, statesman, and governor—the new town became the county seat of Brunswick County.

Even though congressional authorization to reconstruct Fort Johnston was obtained in March 1794, the new fort was not completed until 1816. Twenty years later, the dire need for manpower during the Seminole uprising in Florida forced the federal government to remove the garrison from the fort. All the while, the primary occupation of Smithville residents remained river piloting. To govern themselves, to ensure the orderly dispatch of pilots, to train future pilots, and to care for the families of deceased pilots, the Pilots’ Association—the forerunner of the modern organization in Southport—was formed.

In the decade preceding the Civil War, the town began exhibiting the trappings of a well-to-do resort. Wealthy and refined people made their way to the riverfront hotels and boardinghouses that had begun to flourish. Approximately seven hundred permanent residents were living in the town on the eve of the war.

John W. Ellis, the governor of North Carolina, ordered Confederate forces to seize Fort Johnston on April 15, 1861. Until Fort Fisher surrendered on January 15, 1865, Fort Johnston and Smithville remained under Southern control. Throughout the four years of the conflict, the river town served as a vital link in the “Lifeline of the Confederacy.” Time and time again, sleek blockade runners under fire from Union warships blockading the North Carolina coast found safety in the tiny harbor at Smithville after harrowing escapes.

In the decades that followed the war, hopes ran high that Smithville would develop into a commercially important seaport. In anticipation of newfound greatness, the town changed its name to Southport in 1887. Enthusiasm for its potential as a port waned after efforts to build a railroad to the town were abandoned in the late 1880s. Nevertheless, by the turn of the century, Southport was an oasis of sophistication and modernity in an area heavily dominated by rural hamlets, farmsteads, and swamps. The town of fourteen hundred residents boasted many conveniences, such as telephone service, then reserved only for major cities.

Completion of the Intracoastal Waterway in the 1930s led to a rebirth of the tourism industry, as Southport became a favorite stopover for north-south water traffic during the summer and winter months. Over the succeeding decades, the town has reaped economic benefits as the supply town for the beach communities on nearby Oak Island.

On July 19, 1975, the reign of Smithville and Southport as the county seat of Brunswick County came to a close, when a hotly contested, sometimes bitter referendum ended in a vote to move the seat to the hamlet of Bolivia, on U.S. 17.

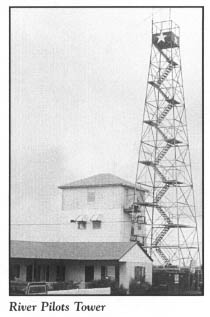

To continue the waterfront tour, leave the parking lot and drive west on Bay Street. Towering above the waterfront is the River Pilots Tower, a tall, skeletal structure resembling a forest tower, without the cabin at the top. This structure was built in the early 1940s to replace a wooden tower located near the foot of Howe Street. Before the advent of modern ship-to-shore communication, the tower was used as an observation post for the river pilots. As soon as a ship was spotted on the horizon, the watchman dispatched a pilot to meet the incoming vessel.

Two distinct harbors grace the Southport waterfront.

Located at the foot of West Bay Street and around the bend of Brunswick Street is the Old Southport Yacht Basin. This ancient port facility, which looks more like a painting by a coastal artist than a working harbor, traces its roots to pre-Revolutionary War times. Despite extensive damage suffered during Hurricanes Hazel and Diane in the 1950s, it has changed little in appearance over the years. On sunny spring days, the calm, smooth waters act as a huge mirror, casting reflections of the wide variety of boats tied to posts and piers. Few visitors disagree with travel experts who have described the yacht basin as one of the most beautiful harbors in all of coastal America.

Southport’s large commercial fishing fleet docks here. Daily catches of fish and shrimp are unloaded at the fish houses built over the water on the eastern side of the basin. A wooden boardwalk and a system of piers and walkways connected to the fish houses and the other harbor buildings offer a spectacular view of the harbor.

Of all the vessels moored at the yacht basin, the most identifiable are the pilot boats owned and operated by the Cape Fear Pilots Association. These steel-hulled vessels, painted black and white, are the latest in a line of pilot boats that have been a fixture on the Southport waterfront for about as long as the Cape Fear River has been an important artery for oceangoing traffic.

The abundance of modern navigational aids available to ship captains notwithstanding, no large ocean vessel enters or leaves the river without the assistance of one of the veteran river pilots of Southport. When a ship is ready to make its way up the river to Wilmington, one of the pilot boats carries a pilot out to meet the ship.

To reach Southport’s second harbor, follow Brunswick Street to Short Street. Turn right onto Short, then left onto West Street. Long known locally as the Small Boat Harbor, the larger of the two harbors is located at the end of West West Street.

State funds realized from a 1959 bond issue were used to build this expansive facility. Constructed for the State Ports Authority in 1965, the marina complex was operated by the state for some fifteen years. Now privately leased and operated as Southport Marina, the Small Boat Harbor is one of the largest marinas in North Carolina. It provides a wide array of services for pleasure boaters making their way up and down the Intracoastal Waterway.

From the marina, turn around and drive east on West West Street to begin a tour of the Southport Historic District.

In 1981, following three years of arduous work by the Southport Historic Society, this district—roughly equivalent to the original city limits—was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Most of the historically significant structures within the district are Victorian buildings constructed from 1885 to 1905. Southport is considered by many architectural experts to be the best example of a Victorian coastal town in North Carolina.

Virtually all of the historic buildings lie along streets that have changed little over the past two centuries. These streets bear the names of historic figures who left their imprint on the Cape Fear area and North Carolina in general. For example, Moore Street is named for Colonel James Moore, Revolutionary War hero; Howe Street for General Robert Howe, patriot extraordinaire of Brunswick County; Rhett Street for Colonel William Rhett, the man who sailed into the Cape Fear River in 1718 and captured Stede Bonnet; Caswell Street for Richard Caswell, Revolutionary War hero and governor; and Clarendon Street for the earl of Clarendon, one of the eight Lords Proprietors of the Carolina colony, and the man for whom the early British settlement in the Cape Fear region was named.

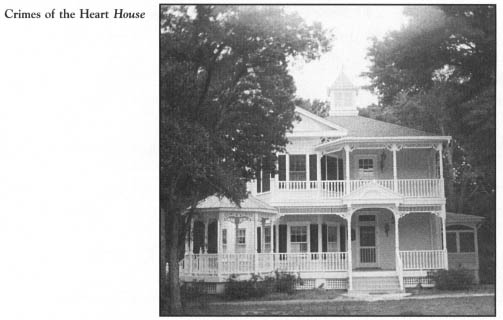

At the intersection of West Street and Caswell Avenue, turn right, or south, onto Caswell. Ironically, the magnificent Victorian house you will see on Caswell is a product of the arrival of Hollywood in Southport.

During the summer of 1986, Southport was transformed into Hazelhurst, Mississippi, as film stars Diane Keaton, Sissy Spacek, Jessica Lange, and Sam Shepard arrived in town for the filming of the blockbuster movie Crimes of the Heart. More than two hundred thousand dollars and five months of labor were necessary to convert the dilapidated early-twentieth-century house on Caswell into a showplace replete with towers, a cupola, and stained-glass windows. It was pictured in the movie as the McGrath House, the home of the central characters.

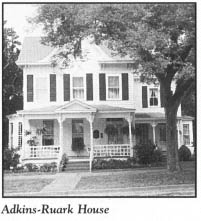

From Caswell, turn east onto Nash Street, then south onto Lord Street. At 119 North Lord Street, at the corner of Nash and Lord, stands the Adkins-Ruark House. This immaculate two-story multigabled structure, built in 1890 by river pilot E. H. Adkins, is best known for another former resident. Adkins’s grandson, Robert Ruark, the world-renowned author from Wilmington, spent much of his youth at the Southport house and visited often after he was an adult. His early years in Southport formed the basis of his widely acclaimed novel The Old Man and the Boy.

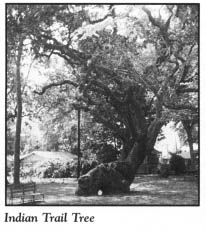

Turn right, or west, off Lord Street onto Moore Street. Keziah Park features a tranquil, well-shaded area along one of the busiest avenues of the city. Among its beautiful trees is the legendary Indian Trail Tree, reputed to be more than three hundred years old. When it was very young, this unusual live oak was bent by Indians to mark their line of travel to fishing grounds. Its unusual shape led to its listing in “Ripley’s Believe It or Not,” which reported that it is one of only five such trees in the United States.

Turn south off Moore onto Caswell Street, then east onto Bay Street. One of the most spectacular homes overlooking the waterfront is the T. M. Thompson House, at 216 West Bay Street. Built in 1868 by a blockade runner for his family, this striking two-story frame dwelling features a widow’s walk surrounding the cupola atop the hip roof.

Turn north off Bay onto Howe Street. Located at 116 North Howe, the Southport Maritime Museum opened in 1992. This museum is the realization of the dream of many civic-minded individuals and history lovers in the lower Cape Fear region.

During the early 1970s, Southport flirted with such a facility when an ill-fated museum operated on the deactivated Frying Pan Lightship. From 1967, when the city of Southport acquired her from the United States Navy, until 1981, when the deteriorating hulk was unceremoniously pulled away by tugs, the 133-foot Frying Pan Lightship was moored at the foot of Howe Street.

The new museum treats visitors to twelve attractive exhibits linked to each other through a story line. Included are displays concerning the area’s first inhabitants, early white explorers, the first area settlements, the American Revolution, the birth of Southport, the Civil War, navigational aids, shipwrecks, and fishing.

Historic Franklin Square, located on Howe Street just north of the museum, is known to many locals as “The Grove.” Stone walls constructed more than a century ago from the ballast rock used by sailing ships enclose this town green, which is shaded by a canopy of beautiful live oaks. Some of the trees, including one named “Four Sisters,” were in existence at the time the park was established for public use in 1792.

Franklin Square is the focal point of the activities associated with the North Carolina Fourth of July Festival. Now recognized as the state’s official observance of Independence Day, this annual four-day celebration dates from 1795, when officers at Fort Johnston and residents of Smithville joined forces to commemorate America’s political independence.

An interesting ensemble of late-nineteenth-century public buildings is clustered around Franklin Square. Located on the northern side of the square, the Franklin Square Gallery is housed in a massive two-story frame building constructed in 1904 as a school building. On the southern side of the square at 203 East Nash Street, across the green from the gallery, the Masonic Lodge is a handsome two-story building erected after the Civil War. Located just across East Nash from the Masonic Lodge, the former Brunswick County Courthouse was the second courthouse located on this site. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the building, which fronts on Moore Street, was constructed in the early 1850s. It served as the house of county government until the county seat was moved to Bolivia in 1975.

Proceed to the front side of the courthouse, at 133 East Moore. The old central business district in the 100 block of East Moore contains an interesting collection of late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century commercial buildings.

Southport is proud of its old church buildings. For almost 150 years, Episcopalians have worshiped in the church located on East Moore adjacent to the old courthouse. Erected around 1860, the white, frame St. Philips Episcopal Church was used as a hospital and school during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Thereafter, significant repairs and alterations were made on the structure. Some of the fixtures, including the altar rail and baptismal font, are more than 250 years old and were inherited from the church’s namesake, the ancient church at Brunswick Town. Wooden collection plates, altar cloths, and other items were also transferred from the original St. Philips. Because of their rarity, the baptismal font and the altar cloths are locked in a vault and are used only on ceremonial occasions.

Return to Howe Street and turn south, then turn east onto Bay Street. Located at 239 East Bay, the Walker-Pyke House is believed to be the oldest home in the city. Built between 1800 and 1820, this graceful two-and-a-half-story structure features three dormer windows on its front and back sides.

The sumptuous Greek Revival house at the corner of East Bay Street and Atlantic Avenue has come full circle in its 140-year history. Now a private residence, it is still known by its former name: the Brunswick Inn.

Built by a Wilmingtonian as a summer residence, the two-story house was enlarged and converted into a resort hotel in 1882. When the Brunswick Inn closed in 1917, the original structure was returned to residential use. In recent years, it has been restored to its early elegance.

There have long been tales that ancient tunnels run beneath this house. The passageways are rumored to have been used to store the loot of pirates and the valuables of local citizens during the Civil War. Pieces of eight unearthed in the backyard of the house are evidence that the tunnels may indeed exist.

The home’s current owners, guests who have spent the night in the house, and many Southport residents are familiar with the building’s most famous link to its past: Tony the Ghost. Tony, last name unknown, was one of three musicians who lived and performed here when the building served as an inn. His harp brought great pleasure to the patrons.

The musicians saw a tragic end, drowning when a storm came up during a Cape Fear fishing trip. According to local legend, Tony’s spirit returned to the inn in search of his harp. Since that time, his beautiful music has been heard throughout the house by many people. On occasion, the music lasts all day, while at other times, it is of short duration. News reporters from Raleigh once visited the house and listened to Tony play.

Tony’s presence has been detected in other ways as well. One of the previous owners felt the ghost pass her in a doorway and heard a whoosh as it passed. Doors that mysteriously open and close are attributed to Tony. While seeking a place to live, the new Brunswick County planning director was a guest in the house for eight weeks. During his stay, he heard doors opening and closing in the middle of the night.

Another former Brunswick County official, the county manager, stayed at the house when he first arrived in town in 1979. It was on a March night during his three-month stay that he had an eerie encounter with the benevolent ghost. At the time, he was taking prescribed medications, one of which had to be consumed at night. After falling asleep in his room, he was suddenly awakened by someone shaking him. He crawled out of bed, turned on the light, and remembered he had not taken his pill. The county manager related the strange occurrence to his hostess, who then acquainted him with the story of the resident ghost.

Continue 1 block on Bay Street, turn north onto Rhett Street, proceed 1 block, and turn east onto Moore Street.

The Old Smithville Burying Ground is located at the northeastern corner of this intersection. When this shaded spot was consecrated as a burial ground in 1792, there were already numerous graves on the site, some more than thirty years old.

This ancient cemetery is graced with a wide variety of interesting, time-worn headstones, statues, and monuments. The most fascinating grave site features a monument erected in memory of the young sea pilots who drowned in two successive storms in the 1870s. Only two of the bodies were recovered. They were interred in the cemetery beneath the monument, which was purchased by the families of all the lost seamen.

Proceed east on Moore Street to Bonnet’s Creek, a historic waterway leading to the Cape Fear. In the second decade of the eighteenth century, Stede Bonnet secreted his famous pirate vessel, The Revenge, in this creek.

If you care to take a side trip aboard the Southport-Fort Fisher Ferry, continue 1 mile on Moore Street to where it intersects S.R. 1534, an 0.7-mile road leading to the ferry landing. Note that if you choose this side trip, you will also have to take a return ferry ride to Southport to complete the present tour. (For information on Fort Fisher, see The Wrightsville Beach to Pleasure Island Tour, pages 237–45.)

While waiting for ferry departure, many motorists leave their vehicles and walk to the extensive marsh area adjacent to the landing. During spring and summer, a resident alligator can often be observed swimming or sunning in the streams that meander through the marsh.

Aboard the ferry, passengers are treated to a panorama of historic sites and interesting landmarks. This ferry provides the best opportunity to see one of the least-known historic sites in the area. Few people are able to visit Price’s Creek Lighthouse, for it stands on private property owned by the Pfizer Corporation on the banks of the Cape Fear. Though the squat, unpainted brick lighthouse has long been dark and is missing its light, it is of great historic significance, as it is the only survivor of the chain of range lights constructed in the antebellum period to aid in the navigation of the river from its mouth to Wilmington.

When it was equipped with a beacon, the lighthouse stood sixteen feet tall, and its light cast rays twenty-five feet above the water. Until a direct shell hit left a gaping hole near ground level and rendered the light inoperable in early 1865, the lighthouse was a strategic Confederate signal station.

At present, access to the site is extremely limited. Permission should be obtained from its corporate owner before an on-site inspection is attempted.

During the thirty-minute trip across the river, the ferry often passes large ocean liners and other traffic from the port of Wilmington. Several spoil islands—nesting grounds for pelicans, gulls, and other coastal birds—are visible along the route.

There are no bridges across the mighty Cape Fear south of Wilmington. In February 1956, a High Point businessman filed application with the North Carolina Utilities Commission to establish a ferry service between Fort Fisher and Southport. However, nothing came of the proposal, and another ten years passed before the state inaugurated the existing ferry.

During its quarter-century of service, the southernmost ferry on the North Carolina coast has steadily increased its ridership and shrugged off its image as a seasonal tourist attraction. With the exception of a temporary state budgetary crisis that threatened to halt or severely restrict the Cape Fear crossings, the viability of the ferry has never been questioned.

From Bonnet’s Creek in Southport, retrace Moore Street all the way to Howe Street. Turn right on Howe, proceed to Ninth Street, turn left, and follow Ninth to where it ends at Maple. Turn left on Maple, then right on Indigo Plantation Drive. Follow Indigo Plantation Drive to the marina on the waterfront, where Bald Head Island, Ltd., provides ferry service to Bald Head Island. Because there are no bridges to this semitropical island, access is limited to water transportation. Private boat owners can make their way to Bald Head from any of the local harbors and marinas. If you plan to take the ferry, be sure to inquire about departure times in advance.

Once visitors set foot on Bald Head Island at the large, modern marina, they marvel at the unspoiled beauty of this masterpiece of nature.

While stationed at Fort Holmes on Bald Head during the Civil War, Captain David A. Brice wrote, “Bald Head is one of the most beautiful places on the coast…. It would be murder for me to attempt a description so I will leave its beauties for you to picture.”

When Kent Mitchell, a member of the current island ownership group, first saw the island in the 1980s, he was likewise impressed: “What took my breath away was its beauty, a sense of natural wilderness.”

There is perhaps no other barrier island on the North Carolina coast that could be described in almost identical terms nearly 120 years apart.

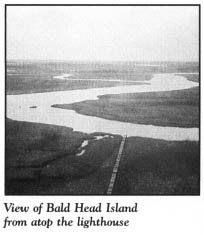

Bald Head Island’s name remains a subject of debate for geographers, cartographers, historians, and coastal authorities. Some experts limit their use of the name Bald Head to the small area of several hundred acres on the extreme southwestern portion of the complex of islands shown on many maps as Smith Island. But for area residents and most North Carolinians, Bald Head means Cape Fear, Middle Island, Bluff Island, and a long strip of barrier beach known as East Beach.

Bounded on the south and east by the Atlantic Ocean, on the north by marshlands and Corncake Inlet, and on the west by the Cape Fear River, Bald Head is a beautiful collage of beaches, dunes, maritime forests, freshwater ponds, tidal creeks, salt marshes, estuaries, and mud flats. Shaped like a triangle, the island complex contains between twelve thousand and seventeen thousand acres, depending on the height of the tide. Only about three thousand acres are highlands—the remains of a series of ridges and forested dunes. Separating these ridges and dunes are large expanses of marsh interwoven by meandering tidal creeks.

East Beach, a sea face of white, sandy beach extending 14 miles from Corncake Inlet to the mouth of the river, is by far the longest expanse of beach. West of the point of land called Cape Fear and extending to the mouth of the river, the southern beach is high and broad. It is from this beach that the island takes its name.

Transportation on Bald Head is one of the most unusual and interesting aspects of the island. With the exception of a few service vehicles, no gasoline-powered vehicles are allowed. Instead, traffic is limited to electric golf carts. The thoroughfares are not called streets, roads, or avenues. Rather, they are wynds. Although most have been paved—at great expense to the current and previous island owners—they are narrow. The speed limit on the island is eighteen miles per hour.

Since Bald Head offers no facilities for the public other than those at the marina complex, it is recommended that you tour the island by golf cart, rather than on foot. Golf carts are available for rent at the marina.

The tour of Bald Head Island begins at the Island Chandler, a large, modern complex built near the marina to meet the basic shopping needs of visitors and residents. From the Island Chandler, proceed east on North Bald Head Wynd to the Bald Head Island Lighthouse.

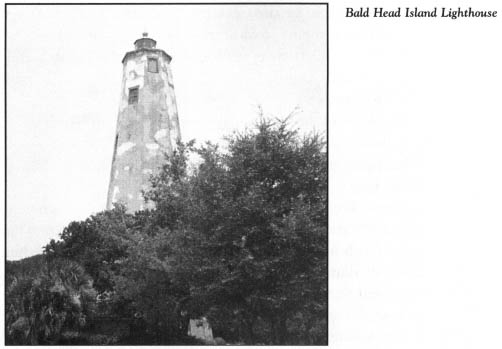

Affectionately known as “Old Baldy,” this lighthouse holds the distinction of being the oldest in the state. It was completed in 1817 to replace the island’s original lighthouse, which was erected in 1794 as the first lighthouse on the North Carolina coast.

Located on a bluff a hundred feet from the Cape Fear River, Old Baldy towers over the island as it has for more than 175 years. The final retirement of the beacon came in 1958, when the Oak Island Lighthouse was put in service just across the river.

Old Baldy is octagonal in shape, its six-story walls standing ninety feet tall and varying in thickness from two to five feet. On the exterior, the masonry covering has broken away in a number of spots, exposing the underlying brick construction. Windows are located on each story. Inside, the wooden steps have been rebuilt from top to bottom. A spectacular view awaits visitors who climb the 112 steps to the platform at the top of the lighthouse.

Because Old Baldy is located on property owned by the island developer, permission must be obtained before entering or attempting to climb the structure.

Near the lighthouse stands an old oil-storage house, located adjacent to the former site of the multistory keeper’s quarters, which vanished long ago.

Concern over the deteriorating condition of Old Baldy prompted admirers of the lighthouse to form the Old Baldy Foundation in 1985. Since that time, the foundation, in conjunction with the North Carolina Division of Archives and History, has commissioned work on the eroding exterior of the structure.

Proceed west from the lighthouse complex on North Bald Head Wynd to the intersection with South Bald Head Wynd just north of the Island Chandler. Follow the latter wynd as it makes its way along the banks of the Cape Fear River.

It was along this route that the Confederate government constructed a massive earthwork fortification in 1863. Some five hundred slaves, many recruited from nearby plantations, were used to finish the project. When completed, the fort extended more than 1.5 miles from the junction of the river and the ocean to a bluff east of the lighthouse.

Named Fort Holmes for Lieutenant General Theophilus Holmes, North Carolina’s highest-ranking Confederate officer, the installation was charged with three important duties: keeping the Cape Fear open to Confederate shipping, preventing enemy landings, and lending assistance to friendly ships that encountered trouble on nearby Frying Pan Shoals.

Upon the fall of Fort Fisher in January 1865, the Southern troops abandoned Fort Holmes after destroying its guns and supplies. The fort served the war effort for a total of only 411 days.

A significant portion of the earthworks is still discernable along South Bald Head Wynd and North Bald Head Wynd. A legend handed down for generations tells of a large brass cannon that was dropped in the deepest part of Bald Head Creek by the garrison of Fort Holmes so that it would not be captured by the enemy. It has never been found.

As South Bald Head Wynd winds its way around the southwestern bend of the island at the mouth of the river, visitors come face to face with history. It was to this very place that many of the great European explorers of the sixteenth century came on their visits to the New World.

Only thirty-two years after Christopher Columbus made his historic voyage, Giovanni da Verrazano became the first European to sight the island and to sail into the mouth of the river.

In 1526, Luis Vasquez de Ayllon, a wealthy citizen of the island of Hispaniola in the West Indies, attempted to colonize the Bald Head Island area, having obtained a land grant between the Cape Fear and Savannah rivers from King Charles V of Spain. Ayllon’s greeting at Cape Fear was anything but pleasant, as the largest ship in his fleet wrecked at Bald Head—the first known shipwreck in the coastal waters of the United States. His men fabricated a replacement vessel while at Cape Fear. This ship is believed to have been the first ship constructed by Europeans in what is now the United States.

The British experience at Bald Head began with the Sir Walter Raleigh expeditions of 1584–1587. On the 1585 expedition, which brought the first colonists to the North Carolina coast, the treacherous shoals at Cape Fear almost changed the history of North Carolina and English America. When the fleet arrived on July 16, 1585, Simon Ferdinando, the captain of John White’s flagship, almost ran the ship aground at Cape Fear. Had the flagship wrecked here, it is quite probable that the first English colony in America would have settled at Bald Head Island.

South Bald Head Wynd runs parallel to the strand on the southern half of South Beach.

Sometime before 1840, Bald Head Island received its name from the Cape Fear River pilots, who put a tall dune on this part of the island to good use. To earn the honor of bringing a ship into the river, the pilots began the custom of racing to the incoming vessel. They sought the highest spot on the outermost reach of land as a vantage point from which they might glimpse the sails of approaching ships. The continued use of the tall dune as a lookout spot gradually wore down the sea oats and vegetation until the dune began looking like a big, bald head.

At the intersection of South Bald Head Wynd and Stede Bonnet Wynd, turn north onto the latter road. Though this route passes through the island’s golf course and reveals other evidence of resort living, don’t be deceived. Bald Head is one battleground where conservationists have actually won the war against future development.

Almost a century has passed since the first plans were announced for the commercial development of Bald Head. In the 1890s, an attempt by a Pennsylvania congressman to build a resort spa comparable to Atlantic City, New Jersey, never got off the drawing board.

Thomas Franklin Boyd, a native of the North Carolina foothills, made the next serious attempt to develop the island, which he renamed Palmetto Island for its profusion of palm trees. In the mid-1920s, he constructed the Boyd Hotel on a high bluff just south of the lighthouse. Boyd’s dream for the island turned into a nightmare during the Great Depression. The hotel was abandoned in the 1930s and reduced to rubble by a fire in 1941. A marker near a pile of old bricks on the roadside is all that remains of the old hotel.

For decades thereafter, the future of the island was a subject of heated controversy. Not until the 1970s, when the state of North Carolina acquired title to ten thousand acres—including extensive marshland, 6 miles of shoreline on the eastern side of the island, and numerous small islands—did conservationists and naturalists believe they had won the battle to preserve much of Bald Head in its natural state. Administered as a natural area under the auspices of the North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation, the North Carolina Division of Coastal Management, and the North Carolina Wildlife Commission, the extensive state holdings became a “day-use only” park in 1986.

Approximately two thousand acres of the island are in private ownership and are subject to development. Fortunately for conservationists, the island’s developer has proven sensitive to environmental issues and is seeking to promote orderly development.

At the intersection of Stede Bonnet Wynd and Edward Teach Wynd, turn east on Edward Teach Wynd. These two avenues bear testimony to the time when Bald Head was a pirate haven. That the island was a favorite hangout for pirates is undisputed by experts. Francis L. Hawkins, a nineteenth-century historian, concluded that the Cape Fear region was a haven for pirates “second only in importance to Providence.”

It is estimated that during the first two decades of the eighteenth century, a thousand men were using Bald Head as a base from which to launch pirate attacks on unwary ships. In a two-month period in 1718, thirteen ships fell prey to pirates operating from the island. Blackbeard used Bald Head on occasion, but it was Major Stede Bonnet who was most at home at Cape Fear.

No pirate had a stranger story than Bonnet. He was born into a respectable English family and received a good education. After a successful military career, he retired to Barbados, where he purchased a sugar plantation and assumed a place of stature in Bridgetown society. For reasons never fully explained, Bonnet, who had never been a sailor, forsook his life as a highly respected gentlemen and went a-pirating. Some historians have maintained he changed his lifestyle to escape a nagging wife.

After legitimately purchasing a ship, which he named The Revenge, Bonnet recruited a crew of seventy men from the grog shops of Bridgetown. Initial successes at sea were followed by a 1717 cruise with Blackbeard that ended when Bonnet was double-crossed by his partner in crime. This incident etched a streak of cruelty in Bonnet. No longer were his ways those of a refined gentleman. Instead, torture became his modus operandi. Unfortunate victims “walking the plank” have long been a stock scene in Hollywood pirate films. It is believed that Bonnet was the only pirate of the golden age of piracy to actually force prisoners to walk the plank.

Not only did Bonnet take on a vicious nature, he also changed his name to Captain Thomas. Likewise, he gave his vessel a new name: the Royal James. About this time, he began making Bald Head Island—with its meandering waterways, dangerous shoals, and complex of small islands—a favorite hiding place.

All the time Bonnet was frequenting the Cape Fear region, the citizens of South Carolina, particularly those from the Charleston area, were clamoring for action against him. Colonel William Rhett, the receiver general of South Carolina, volunteered to command an expedition to eradicate the menace at Cape Fear.

No sooner had Rhett’s two vessels attempted to negotiate entry into the Cape Fear River on September 25, 1718, than they both ran aground on sand bars. To Rhett’s relief, the ships were not damaged. All he had to do was stay put until midnight, when the two ships would be refloated by the high tide.

While waiting for the tide, the South Carolinians saw several pirate ships in the river, one of them the Royal James. Bonnet’s ship and the two other vessels in his fleet had been in the river since early August. Bonnet had sought refuge on an island in the river and gone about repairing his leaking vessel. He had found the sandy beach an excellent place to careen his sloop—a process whereby the ship was lifted to one side as the tide went out, allowing the pirates to effect repairs below the water line.

It is believed that when Rhett’s vessels were refloated, they caught Bonnet in a vulnerable position. After Bonnet and Rhett maneuvered their ships for hours trying to achieve an advantage, Rhett gained the upper hand. Unwilling to fight to an almost certain death, Bonnet surrendered unconditionally.

Bonnet was transported back to Charleston, where he was executed on December 10, 1718, thereby ending the unfettered reign of pirates on the North Carolina coast.

Since his demise, Bald Head Island has been rumored to be the site of one of the richest buried treasures in history. According to legend, Bonnet ordered his chief mate, a man named Herriot, to bury some three million Spanish milled dollars and pieces of eight on Bald Head before his execution. After the death of Bonnet and his fellow pirates, no person alive knew the location of the treasure.

Numerous efforts have been made to find it. A Wilmington newspaper ran a story on May 15, 1888, that told of a Southport river pilot who had discovered a substantial number of Spanish coins on Bald Head. A nor’easter the previous winter had apparently exposed the coins, one of which bore the date 1713. Because of corrosion, the dates on the other coins could not be determined. Quite possibly, the pilot may have found some of Bonnet’s treasure.

If it ever existed, most of the treasure at Bald Head probably remains buried somewhere on the island. As development continues and sand is dug and moved, workers, residents, or visitors may one day discover a cache hidden on the island for more than 275 years.

Edward Teach Wynd merges into Muscadine Wynd just north of the former site of a Coast Guard station erected on the island in 1914. The maritime forests that line Muscadine Wynd and the other roads cover much of the island. Teeming with unusual plants and animals, these forests, unlike any others in North Carolina, are dominated by live oak, loblolly pine, and sabal palmetto. One live oak measures seventeen and a half feet in circumference and is estimated to be more than three hundred years old. The palm trees grow naturally nowhere else in the state. They attest to the semi-tropical climate of the island.

It was one of these ancient forests that provided the setting for one of the most bizarre tales from the long history of Bald Head. More often than not, the fine distinction between truth and legend is blurred by time. And thus it is with one of coastal North Carolina’s greatest mysteries: the disappearance of Theodosia Burr Alston.

This intriguing mystery remains a significant part of the history of two distinct areas of the coast: the Outer Banks and Bald Head Island. While both places lay claim to the site of the mystery, there are certain uncontroverted facts related to the incident.

Theodosia Burr Alston was the wife of Joseph Alston, the governor of South Carolina, and the daughter of Aaron Burr, the third vice president of the United States. She was known as a woman of great beauty, intelligence, and refinement. On the last day of 1812, she boarded a small pilot ship, The Patriot, at Georgetown, South Carolina, on a trip to New York for a reunion with her father, who had recently returned from self-imposed exile in England after his famous duel with Alexander Hamilton. Whether because of storm or piracy, The Patriot never arrived in New York. Rather, it drifted ashore at Nags Head in early 1813, devoid of passengers and crew.

At this point, truth meets legend. Exactly what happened to Theodosia continues to be a source of dispute.

Some have speculated that pirates killed Theodosia and plundered The Patriot while the ship was off Nags Head. To substantiate their claim, they point to a portrait of a young woman that now hangs in a private gallery in New York. The painting was taken off The Patriot by Outer Bankers after the vessel drifted ashore at Nags Head. In 1869, this oil portrait was given to Dr. William G. Pool, an Elizabeth City physician, as compensation for medical treatment rendered to a Nags Head woman. News accounts of the intriguing painting subsequently brought a descendant of the Burr family and the daughter of the portraitist to Elizabeth City. They concurred that the portrait was that of Theodosia Burr Alston.

Yet another piece was added to the puzzle in 1910, when J. A. Elliott of Norfolk uncovered a story concerning the body of a young woman of obvious refinement that had washed ashore at Cape Henry, Virginia, in early 1813. The farmer who discovered the unidentified body buried the woman on his farm.

Adherents of the Bald Head legend claim that The Patriot became stranded on the shoals of the Cape Fear region. While the helpless ship foundered, the pirates of Bald Head moved in. After plundering the ship, the raiders threw the crew and passengers of The Patriot overboard, save the beautiful Theodosia Burr Alston. Her striking beauty apparently led the cutthroats to spare her life.

Sometime later, the ransacked and abandoned ship was set adrift by the tides, only to be carried to its final resting place at Nags Head. Meanwhile, Theodosia was carried to the pirate leader in the forests at Bald Head. He recognized her to be the first lady of South Carolina and realized her enormous ransom potential.

Until arrangements could be made to contact Governor Alston for a payoff, Theodosia was placed in the custody of three pirates. Rum being their weakness, they were soon intoxicated, and Theodosia escaped into the night. One tale contends that after she committed suicide, her lifeless body was found by a search party of pirates. Outraged by the incompetence of his subordinates, the pirate chieftain ordered the threesome beheaded. A divergent tale has it that the search party found Theodosia alive and returned her to the pirate camp, where she died in captivity.

Yet another twist to the Bald Head story was given credibility by two men who were hanged in Norfolk after the ill-fated voyage of The Patriot At their trial, the men testified that they were members of the band of pirates responsible for the pillaging of The Patriot at Bald Head. They bore witness to Theodosia’s death.

Regardless of how Theodosia may have met her demise at Bald Head, various accounts of her ghost persist to this day. Before the development of Bald Head, the apparition was seen roaming over the island in a relentless search for a way to escape. In more recent times, her ghost, attired in an elegant emerald-green dress, has been observed walking on the island.

Not only has the ghost of the beautiful lady continued to haunt the island, but so have those of the trio of pirates assigned to guard her. In the distant past, their headless ghosts were observed pursuing the ghost of the young woman. When the Coast Guard manned a station on the island, guardsmen often walked the beach on single-man patrols each night. More than once, stunned sentries returned to the station with tales of headless pirates joining them on patrol.

Many years have passed since the last guardsmen patrolled the beaches of Bald Head, but sightings of the headless pirates have continued. Lovers strolling on the moonlit beaches or through the magnificent maritime forests have been startled by ghosts, who often tap young women on the shoulder in hopes that they might be the elusive Theodosia.

Like many other fascinating mysteries of the North Carolina coast, that of Theodosia Burr Alston may never be explained.

Muscadine Wynd ends at Federal Road, an extension of North Bald Head Wynd. Proceed east on Federal Road as it makes its way to the southeastern tip of the island: Cape Fear. This ancient route was cut through virgin stands of oak, palmetto, pine, and yaupon at the turn of the twentieth century to provide a straight path for a tramway, which supplied materials for the construction of the Cape Fear Lighthouse, formerly located near the southeastern tip of the island.

Even though Old Baldy was constructed on one of the highest parts of the island, its usefulness was limited to guiding traffic into and out of the Cape Fear River. Accordingly, navigational assistance was needed for ocean traffic plying the Atlantic shipping lanes off Bald Head Island. Because of the great expanse of Frying Pan Shoals, which begin at the southeastern tip of the island and extend 30 miles into the Atlantic, navigational experts reasoned that a lighthouse should be located at Cape Fear.

To meet this critical need, a tall, skeletal structure was erected near the point in 1903. In stark contrast to the romantic, dignified sentinels that guard the coast at Cape Lookout, Cape Hatteras, Bodie Island, and Corolla, the Cape Fear Lighthouse was not a thing of beauty.

After more than a half-century of continuous service, the 161-foot lighthouse was retired on May 15, 1958—not because it was inadequate, but because a new, more efficient lighthouse had been constructed at Oak Island. After defying a demolition team’s effort to reduce it to rubble, the tower succumbed to sixty-two sticks of dynamite on September 12, 1958. Nothing remains of the structure except its foundation.

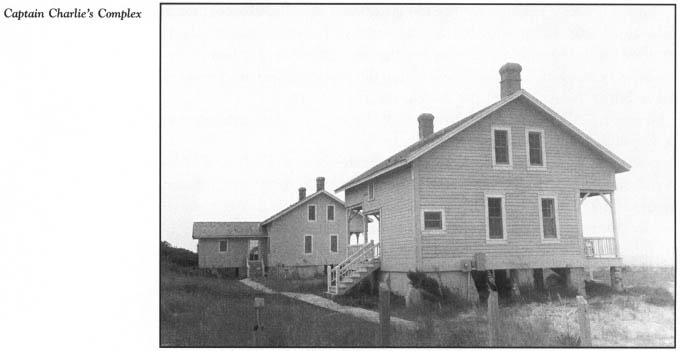

A short side road leads from the foundation to three white frame dwellings known as Captain Charlie’s Complex. Named for Captain Charles Norton Swan, the longtime keeper of the Cape Fear Lighthouse, the houses were built for the families of the keeper and his two assistants. Two of them are available for vacation rental. The entire complex is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A number of paintings by well-known North Carolina artist Bob Timberlake have featured these venerable structures.

Federal Road ends at a gazebo on East Beach. Continue down the beach to the point. This is Cape Fear, an awe-inspiring sight. So terrifying, so menacing, so forbidding is the place that it could have no other name. No one before or since has more eloquently described Cape Fear than George Davis, native son and attorney general of the Confederacy:

A naked, bleak elbow of sand jutting far out into the ocean. Immediately in its front are the Frying Pan Shoals pushing out still farther twenty miles to the south. Together they stand for warning and woe…. The kingdom of silence and awe, disturbed by no sound save the seagull’s shriek and the breaker’s roar…. Imagination cannot adorn it. Romance cannot hallow it. Local pride cannot soften it. There it stands today, bleak and threatening, and pitiless…. And its nature, its name, is now, always has been, and always will be the Cape of Fear.

The tour ends at Cape Fear. Were it possible to make your way here at both sunrise and sunset on the same day, you would be rewarded with a breathtaking experience: due to its unique geographic orientation, Cape Fear allows visitors to see the sun both rise and set on the Atlantic.

Retrace your route to the ferry landing on Bald Head to return to Southport and your car.