Chapter 6

Bloomsbury Doorsteps

‘How you manage to leave out everything that’s dreary, and yet retain enough string for your pearls I can hardly understand.’

– Lytton Strachey writing to Virginia Woolf about her astonishing prose, 1922.

Will this bloody beast ever stay still? Edward Wolfe scooped up the yellow cat for what seemed like the hundredth time that afternoon. It was 1918, and Wolfe was in London from South Africa to study at the Slade, where he quickly met the critic Roger Fry. Bonding over a shared love of Fauvist art, Fry invited Wolfe to join his experimental Omega Workshops in Fitzroy Square.

Now Wolfe was at no. 18 Fitzroy Street in Nina Hamnett’s studio. Nina, another Omega artist, was thoroughly amused by her two visitors – the Workshops’ resident cat and this doe-eyed, dark-haired young man who was determined to sketch his still life. The resulting study shows a self-satisfied, mustard-coloured feline camouflaged by a large bunch of bananas in the foreground. Wolfe noted his victory on the back of the picture: My first studies – Edward Wolfe – painted 1918 in Nina Hamnett’s studio, Fitzroy Street.

Wolfe and Hamnett were not part of the so-called Bloomsbury Group – that loose association of privileged writers, artists and intellectuals based in London in the early 1900s – but they were in the Bloomsbury orbit. Both were beneficiaries of the sweeping influence that Roger Fry and his Bloomsbury colleagues exerted on rising young talent. To someone like Wolfe, who was unfamiliar with London, Fry’s invitation to the Omega Workshops must have been welcome indeed. As for the cat, it was no stranger to being immortalised; it had posed just as disdainfully for the sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska in 1914. Like so many other models, the cat is anonymous.

Well before Wolfe’s arrival in London, the creative footprint of the metropolis was changing shape. Chelsea’s reputation as a home base for the arts was giving way to Fitzrovia, Camden and Bloomsbury – the heart of unconventional London. The squares in this part of London had became signposts for young talent: Fitzroy, Brunswick, Tavistock, Bedford, Mecklenburgh and Gordon.

Fitzrovia would become nearly synonymous with the visual arts, but it had some competition. Clive and Vanessa Bell, Bloomsbury stalwarts, lived at no. 44 Gordon Square until 1917, their front door painted bright vermillion. In fact, the Bloomsbury Group called many places home in the first half of the twentieth century, and formed strong attachments to the studios, houses, squares and gardens where they spent their most creative years.

Town or country, location provided the essential spark that British author Rumer Godden would later describe as grit:

… something large or small, usually small, a sight or sound, a sentence or a happening that does not pass away leaving only a faint memory – if it leaves anything at all – but quite inexplicably lodges in the mind; imagination gets to work and secretes a deposit round this grit – ’secretes’ because this is usually an intensely secretive process – until it grows larger and larger and rounds into a whole.15

The Bloomsbury experience was both full of grit and surprisingly insular. The members looked to each other for inspiration; few of the artists used professional models on a regular basis. They found each other endlessly fascinating, amusing, annoying or arousing by degrees. The bonds they formed would last throughout their lives and imbue, for better or worse, the lives of their children.

The first Bloomsbury connections are generally attributed to the London-based Stephen siblings, Thoby, Adrian, Vanessa (Bell) and Virginia (Woolf). Vanessa began hosting Friday Club gatherings for artists and intellectuals in 1905 soon after her brother Thoby initiated Thursday Evenings for his writer friends from Cambridge University. Thoby died in 1906.

In this way, the Stephen sisters were instrumental in bringing together the creative community that would become the nucleus of the Bloomsbury Group. Most who attended had not yet found fame. The Club originally met at members’ homes, but quickly sought an impartial battleground as it grew. As Vanessa Bell wrote to a friend at the time, ‘We can get to the point of calling each other prigs and adulterers quite happily when the company is small & select, but it’s rather a question whether we could do it with a larger number of people who might not feel that they were quite on neutral ground.’16

Around the same time, the artist Walter Richard Sickert began holding Saturday Afternoons At Home in his Fitzroy Street studio. A spirited debate at the Friday Club could be continued on Saturdays for those willing to rise above a hangover. Sickert’s Fitzroy Street gatherings would evolve into the Camden Town Group in 1910, about two years ahead of the less formalised Bloomsbury Group.

Despite the labels, none of these groups had hard edges; most had hangers-on and common members. Bloomsbury insisted they weren’t a group at all, although they were united by a deep intellectual interest in liberalism, pacifism, sexuality and the philosophies of G.E. Moore. They believed that their ideas were intrinsically good and valuable without the need for definition or proof.

By most accounts there were ten original members of ‘Old’ Bloomsbury (any list is subject to dispute). Joining Vanessa and Virginia as founders were eight men: the art critics Clive Bell and Roger Fry, who was also a painter; writers E.M. Forster, Lytton Strachey and Leonard Woolf; journalist Desmond MacCarthy; economist John Maynard Keynes; and the painter Duncan Grant. All but Grant knew each other through Cambridge.

The ten Bloomsbury originals were meeting regularly by 1912, along with other Friday Club members, and arranging art exhibitions. Not everyone who attended the meetings continued on with the Friday Club. The painter Henry Lamb spent more time with the Camden Town Group and its later permutation, the London Group. Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry and Duncan Grant began exhibiting with the Grafton Group in 1913, although they retained their Bloomsbury connections.

Forming part of the broader Bloomsbury constellation were others who added to the group’s mystique. There was pudgy, naïve Carrington, a mess of contradictions with her blonde pageboy and stubborn chastity. Mark Gertler, who wrote heart-wrenching letters to Carrington begging for the ‘beautiful bondage’ of her love. Nina Hamnett, who had an affair with Roger Fry, and Wyndham Lewis, who had a falling out with Fry. Adrian and Karin Stephen, Saxon Sydney-Turner, Molly MacCarthy, Katherine Mansfield – all these and more became part of the Bloomsbury periphery in different ways.

Angelica (Bell) Garnett holds a unique place in the group’s second generation. Garnett grew up thinking that Bloomsbury founder Clive Bell, Vanessa’s husband, was her father. She was devastated to learn that she was the daughter of Duncan Grant – a man whose many homosexual affairs reportedly included his cousin and fellow Bloomsbury founder Lytton Strachey. In a storyline worthy of Thomas Hardy, Angelica would go on to marry one of her biological father’s other lovers, the adventurous David ‘Bunny’ Garnett.

In posing, as in so much else, the group was complacently self-sufficient. This was emotionally satisfying, as they were often sleeping with, or pining for, each other. Strachey would sit in his lawn chair and read, oblivious to Carrington sketching away. Duncan Grant made good use of Bloomsbury subjects, but in other ways diverged from the norm. Virginia Woolf may have modelled the character of Bernard in her novel, The Waves, as a composite of Desmond MacCarthy and Roger Fry.

The Slade School of Art brought together many notable twentieth-century talents, most of them pre-fame. Front row, left to right: Dora Carrington, Barbara Hiles, Richard Nevinson, Mark Gertler, Edward Wadsworth, Adrian Allinson (with dog) and Stanley Spencer. Dorothy Brett is behind Nevinson and Gertler; Isaac Rosenberg kneels at left. Back row: David Bomberg (shirtsleeves) and Professor Fred Brown. Positions unconfirmed: Muirhead Bone, Henry Tonks, Howard Gilman, Augustus John and Paul Nash (circa 1912).

The group’s members often rivalled professional models for sheer amount of posing. Lady Ottoline Morrell – although not technically Bloomsbury – had close ties to the group. The ubiquitous Morrell is represented in almost 600 portraits (art and photography) at the National Portrait Gallery and is associated with a staggering 1,700 others. Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, Duncan Grant, Dora Carrington, John Maynard Keynes, Mark Gertler, Lytton Strachey, Virginia Woolf, Roger Fry, Wyndham Lewis, Bertrand Russell and E.M. Forster are each represented by eighteen or more portraits, some exceeding fifty.

Despite their London roots, the Bloomsbury members would become inexorably tied to Sussex. In 1916, Vanessa Bell, now separated from her husband Clive, moved to Charleston Farmhouse in East Sussex with her two small sons, Quentin and Julian, Duncan Grant and Grant’s lover David Garnett. Charleston would become the soul of Bloomsbury in the country – it brought fresh grit to the creative process. Secret gardens, mismatched lawn chairs, frenetically patterned carpets and book-strewn shelves became characters in their own right. Bloomsbury members drifted from London to Sussex and stayed for weeks or months. Bell, with her quiet humour, often served as unpretentious muse and model to this ménage.

In Vanessa Bell’s painting, Interior Scene, with Clive Bell and Duncan Grant Drinking Wine, painted at Gordon Square, the amount of detail in the room tells the viewer everything necessary about the connection between Bell’s husband and her former paramour: a shared love of books, fine wine, modern art, good conversation and cosy slippers. This same use of detail would become a hallmark of works created at Charleston Farmhouse, where the artists were responsible for much of the decor.

****

Meanwhile, back in London, the staid Georgian façade of no. 33 Fitzroy Square marked another location important to the group: Roger Fry’s experimental Omega Workshops.

Omega Workshops were a unique creative outlet that added another dimension to the Bloomsbury Group. Started by Fry in 1913, the studio functioned as an artists’ collective with an emphasis on domestic design. Radical experimentation was encouraged. The resulting textiles, furniture, screens and housewares shocked what remained of Edwardian England.

Fry’s use of a commercial venture to nurture artistic development was years ahead of its time. Goods designed and produced at the Workshops were sold to consumers brave enough to put them in their homes. The artists earned a modest income and the right to use the studio space at set times. Fry enlisted his Bloomsbury friends Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant as co-directors of Omega, and encouraged Mark Gertler, Edward Wolfe, Nina Hamnett, Wyndham Lewis, Cuthbert Hamilton and Winifred Gill to contribute.

Omega Workshops debuted to a mix of awe and ridicule. Vanessa Bell, in particular, had taken to decorative art with a vengeance. The results were astounding. Virginia Woolf described her sister’s textile colours as wrenching her eyes from their sockets, and threatened to retreat to dove grey. A kinder reviewer called them fierce and fascinating.

One biting critique focused on the depiction of the models:

… the Omega Workshops in Fitzroy Square continue to ply the brushes and bobbins of discord and disorder. Facing the door is a screen on which are painted figures distorted with the obvious intention of doing violence, not only to the generous elasticity of the human anatomy, but to man’s yet more elastic conceptions of what may be attractive. The screen is ‘anti-tradition’ and nothing else … the man who makes such a screen is, even while he denies it, shackled to the things he abhors … the screen needs a screen.17

For the six years that it lasted, Omega Workshops was a microcosm of the tangled relationships that defined the Bloomsbury Group. Bell, Grant, Garnett, Hamnett and others continued to produce work for sale during the First World War, sometimes acting as models for each other. The venture was hard-hit by the war economy, and despite Fry’s best efforts it never recovered.

The Omega Workshops experiment was yet another of Roger Fry’s profound encouragements of modern art in London. His first was the landmark exhibition of Post-Impressionist paintings that had so dismayed Henry Tonks in 1910. Tonks, who once advised Vanessa Bell to take up sewing, apparently felt that it was best not to comment on her creative output at the Workshops, at least not publicly.

****

Duncan Grant’s fascination with male and female nudes differentiates his body of work from other Bloomsbury artists. His stature as an artist and his unconventional sexuality produced a steady stream of potential subjects, mostly male. When he was starting out, however, and for specific commissions throughout his life, Grant did engage professional female models.

In 1908, a young Grant was working in his first floor studio at no. 21 Fitzroy Square in London. He had just returned from France, and was eager to paint everyone he encountered. Grant often asked friends and relatives to pose, thus saving the expense of professional models. He also worked from photography, and a substantial number of his nude photographs of both men and women still exist. This was a dangerous activity under English law at the time.

Grant soon came to realise that he had trouble capturing the essence of a posed sitter. This was driven home when Virginia Woolf sat for him with poor results. The solution came when he was allowed to sketch Woolf at work over several hours in her home. The idea of seizing the moment with a subject who paid him little or no attention fit perfectly with Grant’s exploratory style, and he developed it brilliantly throughout his career.

One artist–sitter who lived in the same avant-garde manner as Grant in London was the irrepressible Nina Hamnett. Hamnett was carefree about her body, and once danced naked on a café table in France out of sheer lack of inhibition. She was an ideal candidate to pose for some of Grant’s nude stylisations for Omega Workshops.

Hamnett would later write that, aged 16, she had seen nudes in her art school classes but had never looked at herself naked in the mirror:

… my Grandmother had always insisted that one dressed and undressed under one’s nightdress using it as a kind of tent. One day, feeling very bold, I took off all my clothes and gazed in the looking-glass. I was delighted. I was much superior to anything I had seen in the life class and I got a book and began to draw.18

One step removed from the Bloomsbury coterie, four types of women can be seen in their work: lovers, sitters for commissioned portraits, women who epitomised a social or creative force, and – to a much lesser degree – staff and strangers. Their children also served as models.

Lydia Lopokova first sat for Duncan Grant in 1923, two years before marrying John Maynard Keynes. The Russian-born prima ballerina was a famous name in London in her own right – a cult figure who danced with Nijinsky, knew Stravinsky and posed for Picasso. She and Keynes met at a party for the Diaghilev Ballets Russes, and she spent the next five years as his lover while he sorted out his sexuality.

The Bloomsbury circle barely tolerated Lopokova at first. Lytton Strachey likened her to a half-witted canary. Vanessa Bell urged Keynes, who had been a committed homosexual up until then, to avoid the altar and keep her as a mistress. Virginia Woolf wrote that the woman who became known as the ‘Bloomsbury Ballerina’ had the soul of a squirrel.

At Charleston Farmhouse, ‘Loppy’ soldiered on in her quest to win over Keynes’s friends. When it all became too much, she would recharge by dancing naked in the fields in the dawn hours. Despite a nine-year age difference and a considerably wider social gap, she and Keynes were a true love match that lasted until his death in 1946.

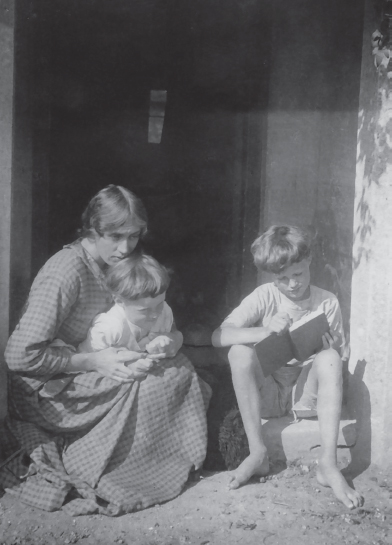

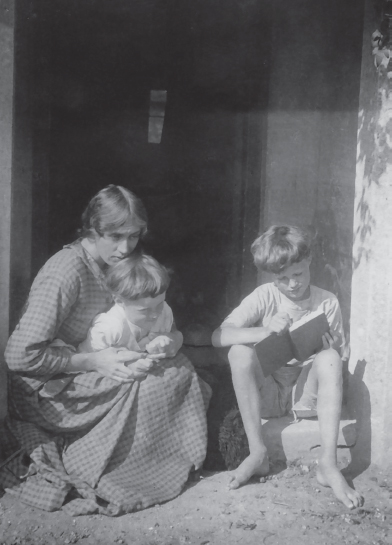

Bloomsbury matriarch Vanessa Bell with sons Quentin and Julian at Charleston (circa 1916).

Lydia Lopokova is thought to have sat for more than twenty portraits in total, including multiple works by Duncan Grant, Ambrose McEvoy and Picasso – who reportedly danced with Lopokova in front of her London house in 1951 on his final trip to England. She remains one of the most under-acknowledged models of the time.

By contrast, Sarah Margery Fry was related to Bloomsbury by blood instead of marriage. The sister of Roger Fry was an imposing presence on canvas. An infrequent sitter for the group, she had a busy professional life. She had portraits painted by her brother and by Claude Rogers, and was compellingly sketched by Charles Haslewood Shannon in 1915. Shannon was an Academy-trained portraitist in the classical style. His choice of pastels suits his subject, who seems caught between introspection and action.

Margery Fry merits attention not as a frequent sitter, but because she was a catalyst for social reform. This resonated with liberal Bloomsbury thinking. Her brother Roger felt that she had promise as a painter, but she chose to attend Oxford University instead. The progressive siblings from a Quaker household lived together for a while immediately following the First World War.

In 1921 Fry was appointed one of the first women magistrates in Britain; a year later she became education advisor to the female inmates at Holloway Prison in London. In the 1930s she travelled to China on a lecture tour and returned to London determined to raise awareness of China’s inhumane prisons and factories.

Margery Fry remained connected to the Bloomsbury Group through her brother Roger, Leonard and Virginia Woolf, and Duncan Grant. The five were lifelong friends despite having very different temperaments. After the Woolfs and Frys visited Greece together in May 1932, Virginia expressed her exasperation in a letter to her sister. She wrote that Margery and Roger would,

‘buzz and hum like two boiling pots. I’ve never heard people, after the age of 6, talk so incessantly … it’s all about facts, and information and at the most trying moment when Roger’s inside is falling down, and Margery must make water instantly or perish, one has only to mention Themistocles and the battle of Plataea for them both to become like youth at its spring.’19

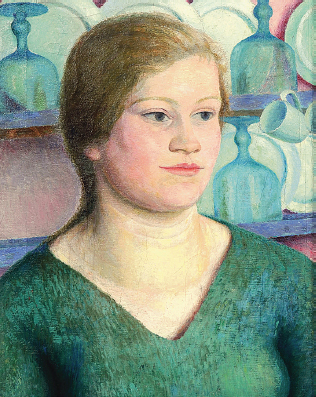

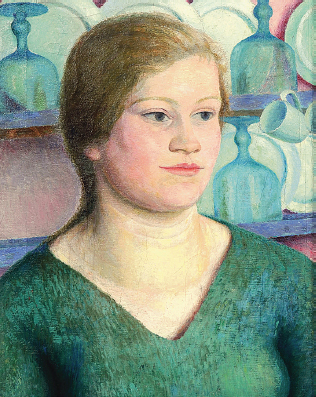

In her later years, Margery Fry’s house at no. 48 Clarendon Road in West London would become a mirror of her wide-ranging interests. Modern pictures, Duncan Grant carpets, Chinese ornaments and ancient pots lived side-by-side with her brother’s artistic endeavours and bookshelves full of Forster and Strachey. It is her fierce curiosity about the human condition, not her face or form, that qualifies her as a Bloomsbury muse.

****

For all their progressive thinking and left-leaning ideals (particularly second generation Bloomsbury), the group seldom turned to the working classes for models. Most members came from well-to-do families and retained a sense of privilege. Servants, nannies, shopkeepers and labourers were seldom portrayed in their works. The Nurse by Vanessa Bell is an exception of sorts – however, Bell chose not to pose a real nurse as a model. Instead, she used a woman associated with the Guinness dynasty.

Carrington, with her merchant father, had no such pretentions. She painted Annie Stiles (housemaid) at Tidmarsh Mill, the country house Carrington shared with Lytton Strachey from 1917 to 1924. Her painting of Mrs Box (farmer’s wife) is another exception to the Bloomsbury insularity.

Inarguably the most prominent Bloomsbury domestic worker who sat in situ is Grace Higgens (née Germany). Higgens worked primarily as a cook for Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant in London and at Charleston Farmhouse. Her relationship with Bloomsbury spans more than fifty years – first as housemaid, then as a cook and housekeeper, and occasionally as a nurse.

The high-spirited Norfolk teenager began her Bloomsbury tenure with Vanessa Bell in 1920 at no. 50 Gordon Square. Higgens became a loyal friend and travelling companion to her employer, and the moral compass of Charleston Farmhouse below stairs. After Bell’s death in 1960, Higgens stayed on another ten years to take care of Duncan Grant. She attended his funeral in 1978, watching the simple coffin pass by with his straw hat on top.

Annie Stiles: Dora Carrington painted the housemaid in the kitchen at Tidmarsh Mill (1921).

The most famous canvas of Grace Higgens still hangs in Sussex – The Kitchen (1943) by Vanessa Bell. The cook’s bent head and neutral clothing relegate her to second position behind the piled vegetables and strong diagonals of the table’s edge. Higgens is more prop than persona under Bell’s brush, but she and her surroundings are in perfect harmony, which is perhaps what the artist wanted to convey. Five years later Higgens served as the focal point in Bell’s work The Cook, although her face is in flat silhouette against a sunlit window. A third painting, Interior with a Housemaid, circa 1939, may depict Higgens as well.

Unlike some of his friends, Duncan Grant had no problem engaging with household staff. As early as 1902 he painted his own version of downstairs life, The Kitchen, in which a cook looks directly out at the viewer from deep within her domain. Higgens would sometimes model for Grant after Bell’s death, and his Seated Model, with Charleston decor in the background, may depict an older Higgens. The look on the sitter’s face seems to coincide with a diary entry from that period in which Higgens wrote: ‘Sat for my portrait after lunch. My eyes keep watering, as Mr Grant insists on me taking off my glasses, I had a peep & think I look a peevish woman.’20

Charleston Farmhouse was not much distance from Monk’s House, where Leonard and Virginia Woolf were often in residence. There were many comings and goings among the two residences and London, all of which Higgens handled with aplomb (she wrote in her diary about beating back two young men who tried to climb through Grant’s window at Charleston).

Higgens found the Woolfs amusing, if sometimes too eccentric, writing in her diary that the two looked like ‘absolute freaks’ riding their bicycles around the country lanes in tattered old clothes. But there was also a fondness there – when Virginia Woolf sent a postcard praising the cook’s sponge cake recipe, Higgens saved it as a keepsake.

Given Woolf ’s loathing of domestic help, her sponge cake note indicates just how valued Grace Higgens was at Charleston. There was a great divide between Woolf, who grew up in a household with servants, and those who were hired to wait on her. This was evident in Woolf ’s relationship with her own cook, Nellie Boxall. Woolf was consumed with giving Boxall the sack for eighteen years, a goal she finally achieved in 1934.

The irony of Woolf ’s domestic situation was her dependence on the servants she abhorred. These included Boxall and a fun-loving housemaid named Lottie Hope, both of whom had previously worked for Roger Fry. Woolf saw herself as a feminist and a strong, independent, modern woman, yet her mental fragility cast her servants in the role of caregivers.

By contrast, Grace Higgens truly possessed the autonomous mindset that Woolf sought her entire life. This was appealing to the Bloomsbury members, who promoted feminism and independence in all forms.

Higgens was just 20 years old when she wrote in her diary in 1924 that she had a terrific argument with Mrs Harland, the Charleston cook at the time,

about my awful Socialist views … Mrs Harland thinks, that the poorer classes, never ought to be allowed to raise themselves up … Mrs Harland also thinks that if a wealthy man offered to make advances towards a poor girl, she should be honoured & allow him to do whatsoever he liked with her, for the sake of a few miserable shillings … & also she should be able to brag about it, that she had been mistress for one night or a few weeks or months of a man with money. Also she thinks I am mad because I said if a rich or poor man wanted me he would have to marry, for if I was mistress of a man & he turned from me to another woman, I would kill him. & she also says I am mad, because I said I do not want to get married, as I would lose my independence.21

Photos exist of all three women – the combative Nellie Boxall, the lively Lottie Hope and the independent Grace Higgens – but only Higgens is known to be on canvas. It helped that she was striking in appearance. Duncan Grant found himself attracted to her more than once, although nothing ever came of it beyond the occasional posing. Nevertheless, she remains a formidable figure in Bloomsbury history and holds a singular position as a sitter.

In the early 1940s, Grant was selected to paint murals at St Michael and All Angels Church in Berwick Village, Sussex. The church was close by Charleston, and Grant made a family affair of it with Vanessa Bell. Two Bell half-siblings, Angelica and Quentin, served as models, along with Angelica’s friend Chattie Salaman. Salaman was a personable actress from an old Anglo-Saxon family who had posed for Augustus John and other artists.

Later, Vanessa Bell’s son Quentin would write about his frustration with the familial bias at Charleston. He told of committing an act of defiance as a young man while on a break from his studies at the Slade.

I felt the need for a model – models not being available in Sussex – I made my way to the Euston Road. I was in a sense venturing into enemy territory … The model was old and hideous, she had the face of a camel … Duncan remarked when he saw the thing, ‘Well, you have made her a dreaming beauty!’ I suspect it was a very bad picture.22

As an adult, Angelica Bell Garnett struggled to come to terms with her unconventional childhood.

Despite his committed relationships with men, Grant’s admiration for women and the female form never waned. Perhaps it was nurtured by his forty-year creative alliance with Vanessa Bell and the unconventional fling that produced their daughter Angelica.

In a short story, When All The Leaves Were Green, My Love, Angelica Bell would make a thinly veiled reference to her upbringing at Charleston as being like a hall of mirrors where she saw only reflections of herself. Certainly, as Charleston’s golden girl-child, she must have felt like she was the centre of an incomprehensible universe.

For her father, Charleston was a hall of Duncan Grant mirrors: a confluence of his daughter, her mother Vanessa and his other former lovers, Lytton Strachey, John Maynard Keynes and David Garnett. Quentin Bell reportedly said, looking back, ‘I love my parents – and I had more than the usual number to love.’

Angelica Bell Garnett, daughter of Bloomsbury, had four talented daughters: Henrietta, Amaryllis and the twins Nerissa and Frances. Henrietta also had a daughter. Grant could hardly escape three generations of female influence even if he wanted to.