London police had little patience with recalcitrant nightclub owners in 1914; they were busy with suffrage protests like this one at Buckingham Palace.

‘One of the first effects of the war was to raise the price of many valuable medicines … Cocaine rose from a little over 4s. to 10s. an ounce.’

– The Globe, lamenting the wartime price of fine chemicals, 1914.

A diva, a monkey and a music-hall Botticelli walk into a bar … thus could be written the story of the club scene in London in one of its most experimental years, 1913.

The Botticelli was Lilian Shelley, a tiny, raven-haired model and chanteuse at the Cave of the Golden Calf. At 10.30 every evening, Shelley stood in a cul-de-sac with the club at her back and thought I could do this in my sleep. Behind her, the strains of a tango filtered up from the basement. In front of her lay a familiar path: down Heddon Street, right onto Regent Street, and then almost two miles to the Strand. A wave to the doorman at the Savoy hotel, and then upstairs to feed Madame Strindberg’s monkey. The things I do for that ridiculous woman!

No one would dispute that Shelley’s employer, Frida Uhl Strindberg, was a diva. It took that kind of temperament to divorce her Swedish playwright husband, August Strindberg, threaten her lover with a gun, move from Vienna to London, and open a scandalous nightclub in Mayfair. The draper’s basement she leased at nos. 3-9 Heddon Street in 1912 housed both the Cave of the Golden Calf and the Cabaret Theatre Club, the front for her nightclub memberships.

Strindberg and her collaborators were not shy. The Aims and Programme of the Cabaret Theatre Club acknowledged that the Golden Calf borrowed from the German cabaret model, while staking out a place on English soil: ‘We do not want to Continentalise, we only want to do away, to some degree, with the distinction that the word ‘Continental’ implies, and with the necessity of crossing the Channel to laugh freely, and to sit up after nursery hours.’28

The avant-garde of London were easily tempted by the hedonistic Golden Calf. The very look of the place invited pagan thoughts. Camden Group devotee Eric Gill designed the phallic bas-relief symbol of the calf at the entrance and the huge, golden statue in the hall below. Wyndham Lewis transformed the stairwell with explosive Vorticist paintings that propelled visitors downstairs with a fury. Spencer Gore and Charles Ginner painted exotic jungle murals. Jacob Epstein’s brightly plastered pillars needed only a little absinthe to come to life.

The Cave of the Golden Calf opened on 26 June 1912. It had been a rare sunny afternoon, and the weather was perfect for an evening out. Strindberg’s talent for persuasion was paying off. One by one, the cultural elite and the up-and-comers descended the stairs. They took their seats in a low-ceilinged room the likes of which London had never seen before. Some would still be there at dawn.

The Golden Calf was not Frida Strindberg’s first foray into business. She was intensely interested in commercial enterprise and the arts. Had she been born at a later time, she would have had access to the training necessary to support both passions. As it was, the Golden Calf survived only two years. Nevertheless, it was a watershed in the evolution of London nightclubs, in part because of Strindberg’s incorporation of modern art as decor.

A number of factors contributed to the club’s bankruptcy in February 1914. Strindberg cultivated the excuse that she had been overly generous in her support of the arts, but she may not have been above-board with the records. War was closing in, and the Golden Calf had become the target of repeated police raids. London police were dealing with an increase in public disturbances from the women’s suffrage movement that year, and they had little patience with Strindberg’s disrespect for licensing hours.

To make matters worse, boring businessmen and silly toffs began to filter into the club, driving away luminaries such as Ezra Pound. One of the nightclub’s most famous patrons, Augustus John, joined a friend in founding the Crab Tree Club in Greek Street. John was known to make women faint when he walked into a room – why not capitalise at his own establishment? Where the artist went, models followed.

Models didn’t kill off the Cave of the Golden Calf, but they didn’t help. Strindberg’s original idea had merit: artists’ models attracted artists, artists attracted writers, and artists and writers got press. She hired the most alluring and talented model-performers she could find for the cabarets that the Golden Calf staged on most evenings.

The problems emerged as the night wore on and the models began to compete with each other. There was a distinct lack of decorum at the club in the wee hours. In 1914, The Times reported the sad case of Mr John Bouch Hissey, a hapless petitioner for divorce. Mr Hissey had pinned up Oscar Wilde’s poem The Harlot’s House on a wall of his own home to make a point to his wife. Mrs Hissey had been widely reported in the London papers as being like ‘one of the women of the Cave of the Golden Calf ’. This was not the kind of attention Strindberg wanted.

London police had little patience with recalcitrant nightclub owners in 1914; they were busy with suffrage protests like this one at Buckingham Palace.

Despite their late-night antics, or perhaps because of them, the identities of most of the artists’ models at the Golden Calf are relegated to the shadows of that hedonist basement. There were a few whose performances attracted followings to the club. Lilian Shelley, the Strindberg monkey-feeder, was the largest draw in 1913.

Shelley was a popular music-hall performer who would trill ‘My Little Popsy-Wopsy’ before trekking to the Savoy each night. The associations she made at the Golden Calf undoubtedly furthered her career, as she would go on to pose for Augustus John, Jacob Epstein and others.

Another model that performed at the club was Dolores, a Londoner who was relatively unknown in her native city. Born Norine Schofield, Dolores began using her stage name while living in Paris. There she made the acquaintance of Sarah Bernhardt and Anna Pavlova, strutted in the Folies Bergère, and sang in opera. She dressed solely in black to highlight her luminous skin.

Dolores had returned to England just as the cabaret frenzy went into full swing. She embarked on a series of failed marriages and was unable to replicate her Paris showgirl success. Like Shelley, she saw an opportunity to raise her profile by performing at nightclubs, and she favoured venues habituated by artists to further her modelling career.

The final nail in the coffin of the Cave of the Golden Calf came on 11 January 1914 in the form of a raid by Customs officers. Three months later Strindberg and club secretary George Edward Shaw were convicted of selling liquor and tobacco without a license. The prosecution noted the high price being charged for drinks after closing hours (the raid was at 4.10 in the morning), implying embezzlement. They pointed to a bottle of champagne priced at twenty-five shillings and whiskey at one and two shillings a glass, versus Shaw’s salary of £3 weekly.

Strindberg was fined £160 or two months’ imprisonment, and Shaw £40 or one month imprisonment. These were heavy penalties. By the time the ruling was issued by the court, it was moot for the club. The Cave of the Golden Calf had closed its doors for good.

****

Following the lead of the Golden Calf, a number of after-hours clubs debuted in London. Jazz was in full swing by the interwar period. The 43 was a late-night club on Gerrard Street run by the notorious Irish import Kate Meyrick. Meyrick was involved in several nightclubs, assisted by four of her eight adult children. In photographs of the Meyrick family, one of the daughters repeatedly hides her face in her fur coat.

Artists had their own preferences when it came to the club scene – the Ham-Bone Club in Soho was a particularly popular spot. It had a restaurant overlooking the dance floor below, and sported an oak beam with the inscription Hush! There is no need to be coarse. The club opened in 1922 – an occasion marked by the display of C.R.W. Nevinson’s painting Zillah, of the Hambone, a striking portrait of London stage actress Zillah Carter. Much later Nevinson would add the date 1935 to the painting, perhaps to mask the fact that it had remained unsold for over a decade. The Ham-Bone Club lasted a dozen years, and it is a measure of its notoriety that its demise merited a mention in the Brisbane, Australia, Courier-Mail.

These clubs, and dozens like them, owed a lot to Frida Strindberg’s vision. They defined the flapper era. A decade earlier however, Strindberg’s chief competition for the arts clientele she craved came in three shapes: Murray’s Cabaret on Beak Street, the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel on Percy Street, and the Café Royal on Regent Street.

The 1913 opening of Murray’s Night Club trailed the Cave of the Golden Calf by just over a year and capitalised on the cabaret boom popularised by Strindberg. Murray’s staged elaborate cabaret productions that attracted young models eager for exposure. Its proprietors rode the tango craze that was sweeping both sides of the Atlantic (‘an obsession’ declared The Sphere), and the club became known as a showplace for the newest dance steps.

The owners of Murray’s Night Club were Jack May and Ernest Cordell. Cordell was an Englishman; May was an enigma – an American from Chicago, and a rogue, genius, criminal, pioneer or vulgarian, depending on whom you asked. One thing is certain: he was a natural-born talent at the club business.

Murray’s received its share of press coverage, both positive and negative. ‘Six Lovely Peaches Grew Upon a Tree’, proclaimed a caption in The Bystander, under a photo of Murray’s cabaret girls holding hands, and ‘A Bevy of Beauty in Beak Street’. But the peaches may have fallen into Jack May’s basket at a price. There was talk that the proprietor lured young women into compromising situations, although this remained largely speculative.

The police definitely had an eye on May. But it is questionable how many tips from the public they acted on, versus bribes they took. Murray’s wasn’t alone in this – by late 1914, with war a reality, club owners found that it was less expensive to pay the police to look the other way when it came to things like licensing hours under the new Defence of the Realm Act.

One tipster who didn’t mince words was Captain Ernest Schiff, a dubious character himself. Schiff wrote to police accusing May of enticing girls to smoke opium, ending with, ‘He is an American and does a good deal of harm.’ It is unclear whether Schiff was inferring that opium or Americanism was May’s worst offence, but in any case nothing came of it. May’s contacts in high places served him well and Schiff himself ran afoul of the law soon afterward.

Compared to Murray’s, the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel was a much safer haven for models. The Eiffel Tower, as it was familiarly called, was located at no. 1 Percy Street just off Tottenham Court Road. Its chef and owner was Rudolph Stulik, an Austrian, and like so many other venues, the Eiffel Tower owed its metamorphosis to Augustus John.

John stumbled across Stulik in the 1890s and decreed that his restaurant would be an artists’ rendezvous. It had a French menu that featured the designs of Wyndham Lewis and art-themed dining rooms. It was also more intimate and relaxed than the nightclubs, and free of wealthy patronage. An artist who needed a meal relied on personal finances or Stulik’s generosity. Lytton Strachey, Jacob Epstein, Nina Hamnett, Marie Beerbohm and others would often end their late nights there.

The Eiffel Tower served as a kind of clubhouse for the Corrupt Coterie, a dubious group founded by the models Iris Tree and Nancy Cunard. The two women shared a flat in Fitzrovia and would organise meetings in an upstairs room at the restaurant. The Coterie was composed of well-to-do, well-educated, young people, primarily aristocrats, who were interested in modern ideas. They also engaged in questionable personal behaviour.

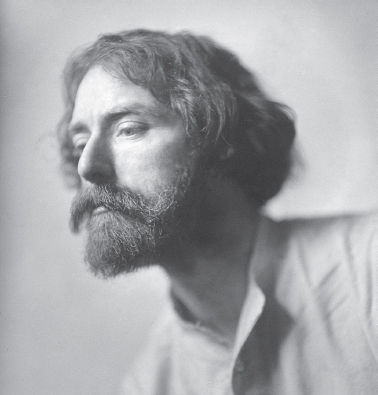

Augustus John was an eclectic genius who moved with ease among all classes.

Lady Diana Manners (later Cooper) penned this confession about her Corrupt Coterie days with a sense of regret: ‘Our pride was to be unafraid of words, unshocked by drink and unashamed of ‘decadence’ and gambling – Unlike-Other-People, I’m afraid.’29 It was an attitude that would come to define the desperate frivolity of the flapper social set. The First World War decimated the Coterie’s ranks, and the remnants became known as the Bright Young People.

Unsurprisingly, a number of Coterie members were directly involved in the arts. Marie Beerbohm was part of the large Beerbohm family of literary and stage fame, as was Iris Tree – both had experience as artists’ models. Nina Hamnett – a good friend of Marie’s – became acquainted with Marie’s sister Agnes and all three served as models for Walter Sickert, whose studio was directly across the street from Hamnett’s flat.

Sickert once caught a bleary-eyed Marie Beerbohm bringing Hamnett a half bottle of champagne to cure her hangover. The painter admonished Beerbohm in the street on the disgrace of young girls drinking in the morning – and promptly confiscated the bottle. A lecture from Sickert was a rare thing indeed; he thought nothing of serving Hamnett cigars with breakfast, or of posing a life-size dummy in a compromising position to shock visitors.

****

Absinthe, anyone? From the moment the Café Royal opened in 1865, it became known for its clientele and for the intoxicating, emerald green drizzle from its absinthe fountain. Its reputation was a two-sided coin.

Absinthe was a creative stimulus for Picasso, Van Gogh, Degas and others who produced major works under its influence. In the last half of the nineteenth century, the drink was blamed for widespread moral decay in Europe and North America. It was believed to be highly addictive and produce an effect similar to cocaine or opium. It was also cheaper than wine at the time, which contributed to its appeal.

In 1868, the American Journal of Pharmacy warned of absinthe, ‘You probably imagine that you are going in the direction of the infinite, whereas you are simply drifting into the incoherent.’ The hysteria would reach a fever pitch in the first years of the new century, but absinthe was never banned in England. The Café Royal continued to thrive, bolstered by the legendary exploits of its patrons.

The relationship between the Café Royal and its most famous patron, Oscar Wilde, was tinged bright green at every turn. One story has Wilde being guided out of the Café Royal’s bar area at closing time and hallucinating that stems of tulips were brushing his pant legs. In reality, a green-aproned waiter was ushering Wilde past red velvet chairs.

Following Oscar Wilde’s footsteps into the Café Royal was a parade of famous patrons. Augustus John, Walter Sickert, Aubrey Beardsley, Noel Coward, D.H. Lawrence, Virginia Woolf and the Duke of York barely scratch the surface. Wilde didn’t live to see the Café Royal at the height of its twentieth century fame (he died in 1900), but he may well have been thinking of his favourite haunt when he wrote that there are three things the English public never forgives: youth, power and enthusiasm.

What made the Café Royal truly unique in the early twentieth century was the collision between high society, high commerce and bohemia. The atmosphere was an intoxicating mix of philosophers, socialists, immigrants, politicians, business titans, royalty, towering creative talents and unapologetic eccentrics. It was see-and-be-seen, and the models came in flocks.

Nina Hamnett, painted by Roger Fry in 1917, was a Café Royal habitué.

Hamnett wrote about the lengths she and a friend would go to every evening to be seen, nursing a fourpenny coffee for hours before walking home to Camden Town because they lacked bus fare. The painter Henry Lamb met his wife, Nina Forrest, in the Café Royal, renamed her Euphemia and encouraged her over-the-top affairs as a model. Bloomsbury’s David Garnett wrote that in the Café Royal he had found a world where respectability was a dubious virtue.

The tête-à-têtes of the Café Royal were the subject of some excellent paintings, most notably by William Orpen, Charles Ginner, Harold Gilman and Doris Zinkeisen. There has been some speculation that the man speaking with a dishevelled Augustus John in Orpen’s painting, The Café Royal, London, is meant to symbolise the coming together of bohemia and the business class. While that was true of the Regent Street establishment, the dapper man in Orpen’s painting is more properly identified as the artist James Pryde, a friend of John.

When the Café Royal began to close early for wartime licensing hours in 1914, the artists continued their evenings at the more accommodating Eiffel Tower. Hamnett recalled the chanteuse Lilian Shelley coming to the restaurant as a guest of Horace Cole, a famous prankster. By that time, Shelley was established as both a performer and an artists’ model:

‘She was the craziest and most generous creature in the world. If she had a necklace or a bracelet on and anyone said that they liked it, she would say, Have it!’30 When Orpen painted his interior scene of the Café Royal in 1912, he sat Shelley, whom Augustus John called Bill, in the rear centre frame.

Of the many other clubs that opened and closed from 1913 to 1930, the Cave of Harmony has a unique history. Its name connects nineteenth-century Victorian rakes to twentieth-century nonconformists.

The Cave of Harmony was actually two different clubs. The first operated in a cellar in Gower Street in the mid-1800s. It became notorious for indecencies and a fair share of ruffians; then it got an upgrade of sorts in the last half of the century. Its clientele toward the end had a strong whiff of privilege, including Members of Parliament and young bucks out for a good time. Eventually the club and the name disappeared from the London scene, to be resurrected in the 1920s.

The second Cave of Harmony was the purview of the bohemian actress Elsa Lanchester and her partner, Harold Scott. Lanchester (née Elizabeth Sullivan) came from Socialist stock and grew up in an environment that encouraged a free spirit.

Lanchester and Scott opened the Cave of Harmony nightclub in 1924 at no. 107 Charlotte Street, Fitzrovia. Soon the artists and models came, and with them Evelyn Waugh, H.G. Wells, Aldous Huxley and others. The late hours and loud music caused problems with the neighbours, and everyone was happier when the Cave of Harmony relocated to the Seven Dials area of Covent Garden. Lanchester closed the club in late 1928.

By and large, the club made good on the claim in its tenancy application: it was ‘for theatrical and artistic people who would present no trouble’. The divide between unconventional mores and proper English behaviour was narrowing, and Lanchester epitomised that bridge.

As one journalist was inspired to pen in genuine admiration of her audacity: ‘I may be fast, I may be loose, I may be easy to seduce. I may not be particular to keep the perpendicular. But all my horizontal friends are Princes, Peers and Reverends. When Tom or Dick or Bertie call, you’ll find me strictly vertical!’31