The Golden Circle is Iceland’s classic day trip. If you have just one day to see the Icelandic countryside from Reykjavík, this route offers the most satisfying variety of sightseeing and scenery per miles driven. And you’ll be in good company: Travelers dating back to the Danish king Christian IX, who visited Iceland in 1874, have followed the same route outlined in this chapter.

The Golden Circle loop includes this essential trio of sights: Þingvellir, a dramatic gorge marking the pulling apart of the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates (and also the site of the country’s annual assembly in the Middle Ages); Geysir, a bubbling, steaming hillside that’s home to Strokkur, Iceland’s most active geyser; and Gullfoss, one of Iceland’s most impressive waterfalls. You can round out the trip by adding any of several minor sights, taking a dip in a thermal bath, or going snorkeling or scuba diving at Þingvellir. This chapter explains your options and links them with driving directions.

Note that the Golden Circle loop is well-trod and extremely touristy. Long lines of tour buses and rental cars follow each other around the route each day, and you’ll see the same faces more than once. Despite the crowds, the attractions hold their appeal.

On Your Own or with an Excursion: Driving the Golden Circle in your own car offers maximum flexibility, but some may find it more relaxing to join an organized bus trip. The tour companies listed on here offer full-day Golden Circle tours (10,000-15,000 ISK depending on group size). Reykjavík Excursions and Gray Line also offer half-day trips—but these cost only slightly less, rush you through the sights, and are worth it only if you’re short on time.

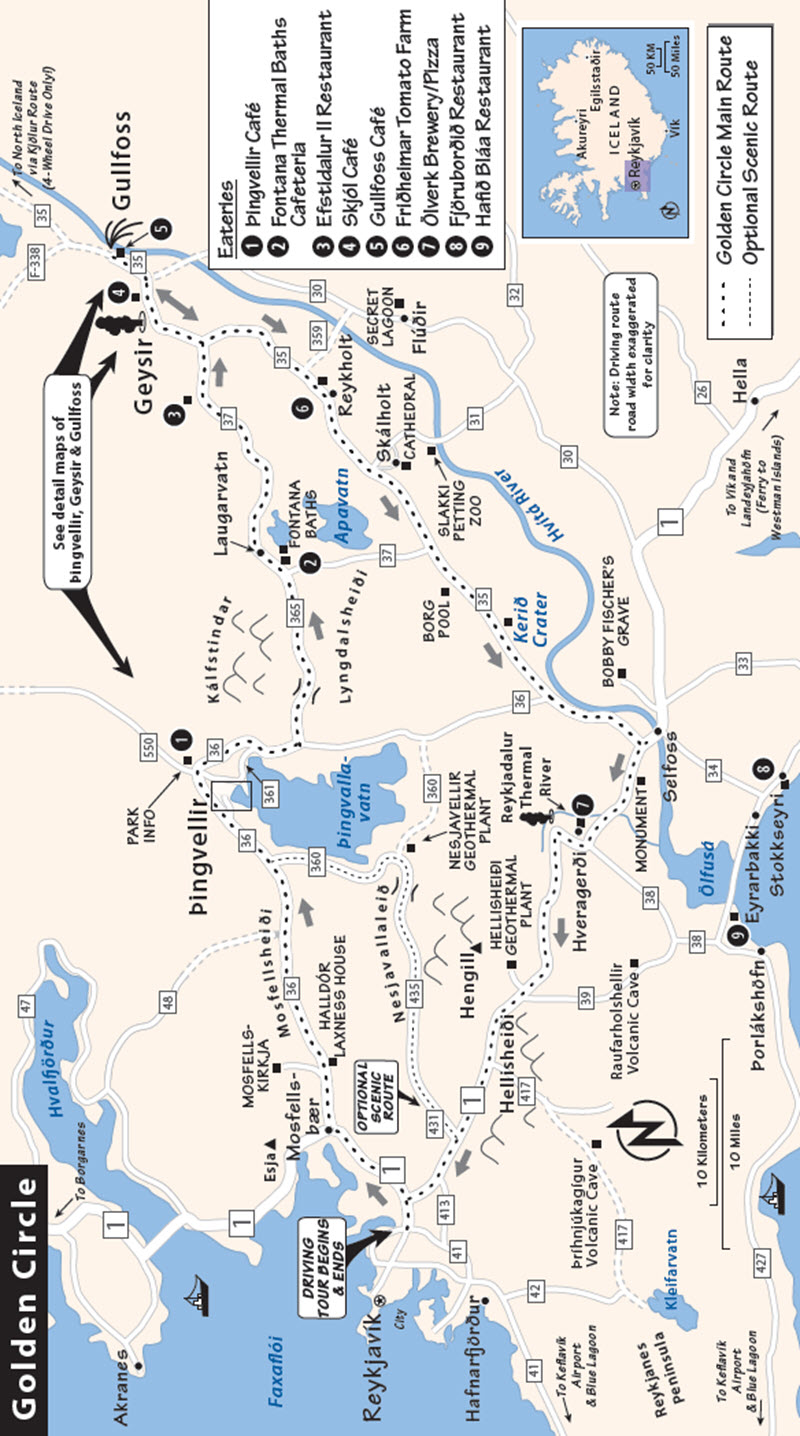

The entire circuit involves about four hours of driving, not including stops. The basic self-guided route is simple: From Reykjavík, you can take your pick for the first leg of the drive (straightforward vs. scenic), either 40 minutes or one hour to Þingvellir. After touring Þingvellir, it’s about an hour to the thermal fields at Geysir, then 10 minutes farther to the gushing Gullfoss waterfall. From there, you’ll backtrack to Geysir and circle back around to Reykjavík in about 1.75 hours, passing a few lesser sights (the most interesting of which is the Kerið crater). My suggested route goes clockwise—starting with Þingvellir—but it can also be done in the other direction.

Here’s a suggested plan (with stops) for those wanting to get an early-ish start and be home in time for dinner:

| 9:00 | Leave Reykjavík and head for Þingvellir national park, taking the scenic Nesjavallaleið route (1 hour) |

| 10:00 | Visit Þingvellir |

| 11:30 | Drive from Þingvellir to the village of Laugarvatn (30 minutes) and have lunch |

| 13:00 | Head to Geysir geothermal field (20 minutes), and watch Strokkur erupt a couple of times |

| 14:00 | Drive to Gullfoss (10 minutes) and visit the waterfall |

| 15:00 | Head in the direction of Selfoss (1 hour), stopping briefly at Skálholt Church and Kerið crater (or any other sight along the way that interests you—all described later) |

| 16:30 | Return to Reykjavík (about 45 minutes from Selfoss) |

This drive is peppered with additional sights and activities; you can easily alter my suggested plan to suit your interests. In addition to the sights described in this chapter, this route also passes by the Halldór Laxness house (commemorating an esteemed Icelandic author) and the Hellisheiði Power Plant (both covered in the Reykjavík chapter). Visiting every possible sight could take two or three days. Before setting out, review the possibilities, prioritize, and come up with a plan that hits what you want to see in the time you have. Here are some things to consider:

Avoiding Crowds: The geothermal field at Geysir—the smallest sight—is the most crowded spot on the route. An early start helps keep you ahead of the tour buses; in summer, when days are long, you could instead do this trip in the afternoon/evening, when crowds are lighter (see “Evening Options,” later).

Activities: Several activities along the Golden Circle require extra time—and in some cases, prebooking. To allow time for any of these, skip some of the minor sights along the drive. The Silfra fissure, at Þingvellir, provides top-notch scuba or snorkeling opportunities (book well in advance—see details on here). Several horse farms are just outside Reykjavík, making it easy to incorporate horseback riding into your Golden Circle spin (again, this should be pre-arranged—see here). There are also several thermal baths along the way (see sidebar later in this chapter).

Evening Options: In the summer, some intrepid travelers—determined to wring the absolute maximum travel experience out of every moment—set out on this loop in the late afternoon...making the most of the abundant daylight. And since the major Golden Circle sights (Þingvellir, Geysir, Gullfoss) don’t technically “close,” you can visit them essentially anytime—plus, they’re less crowded in the evening (some of the lesser sights and thermal baths do have closing times). Another fine evening activity is to have a memorable dinner in the countryside at one of my recommended restaurants—stretching your day and allowing a late return to Reykjavík.

With More Time: If you have an extra day or two, consider splitting the Golden Circle into shorter, more manageable day trips: For example, on one (highbrow) day you could do Þingvellir along with the Halldór Laxness house and the Fontana baths, and on the next (nature-focused) day you could do Geysir, Gullfoss, and the hike to the Reykjadalur thermal river.

Weather and Road Conditions: The route crosses three mountain passes (Mosfellsheiði or Nesjavallaleið, then Lyngdalsheiði, and finally Hellisheiði). These passes can be icy and slippery, especially from October to April. Check the road conditions map at Road.is before you start off. In treacherous conditions, take a bus tour and leave the driving to pros. If you do drive the Golden Circle in winter, it’s smart to set off from Reykjavík an hour before sunrise so you get maximum value out of the daylight hours.

If highway 365 (Lyngdalsheiði, between Þingvellir and Laugarvatn) is closed or in bad shape, you can avoid it by taking a long way around on lowland roads (highways 36 and 35). This adds about a half-hour to the trip, which makes it difficult to cram the entire Golden Circle into a short winter day. You may need to lower your expectations, and do only part of the circuit (either Þingvellir or Geysir/Gullfoss).

Name Note: Be aware that there are two Reykholts in Iceland: one here on the Golden Circle, and the other about 100 miles away, in West Iceland.

Below, I’ve linked the main stops with driving directions. Let’s get started.

There are two ways to get from Reykjavík to Þingvellir: through Mosfellsheiði (highway 36) or along the road called Nesjavallaleið (highway 435). Nesjavallaleið takes a little longer (one hour) and is narrow and curvy in parts (with many blind summits), but is much more scenic. Because of its high elevation, Nesjavallaleið is open only from May to September. If it’s closed, it will appear in red on the road conditions map at Road.is. The Mosfellsheiði route is kept open all year. If conditions are appropriate and you’re confident driving in Iceland, I’d definitely take Nesjavallaleið.

You’ll start this 40-minute route heading north out of Reykjavík on highway 1 toward Borgarnes and Akureyri, then turn right on highway 36 just past the town of Mosfellsbær, following the Þingvellir signs. This leads up through Mosfellsdalur (“Moss Mountain Valley”) and over a low, broad pass (900 feet above sea level) to Þingvellir.

The Mosfellsdalur valley is still rural, with several horse farms. As you drive through, look left up the hillside (or turn up the side road called Mosfellsvegur) to see the unusual church called Mosfellskirkja, designed by architect Ragnar Emilsson in the 1960s. It’s full of triangular shapes—including the bell tower and roof—as a reference to the Trinity.

Note that this route passes by the former home of Iceland’s most famous author, Halldór Laxness (open to tourists; for details see here). Otherwise, it’s a (fairly dull) straight shot to Þingvellir. When you begin to see the Þingvallavatn lake—Iceland’s largest—on your right, you know you’re getting close.

This one-hour route—more with photo stops—is much more interesting than Mosfellsheiði. It climbs high up (to about 1,500 feet) over a craggy mountain range, descends steeply past the Nesjavellir geothermal plant, and then narrows as it hugs the shore of Þingvallavatn lake. Most of Nesjavallaleið (NESS-ya-VAHT-la-laythe) was built as a service road for a giant hot water pipe that feeds Reykjavík’s heating system.

Start out by leaving Reykjavík south on highway 1 toward Selfoss. As the town thins out into countryside, turn left following a small sign for highway 435 and Nesjavellir. The road crosses the giant hot-water pipe, then curves around to follow straight along it. You’ll drive parallel to the pipe—and some high-tension wires—for quite some time. In August and September, the bracken along the sides of this road is a good place to look for blueberries and crowberries. The road rises and eventually hits a ridge, part of a volcanic system called Hengill; from here the road climbs in a series of bends. Before the crest, you can stop at a pullout in the small, mountain-ringed Dyradalur valley, with signboards and picnic benches; an important path for travelers once led through the gully you see at the end of the valley (called Dyrnar—“The Doors”).

As you come over the ridge, you’ll see the Nesjavellir geothermal power station far below you. This plant, built in the early 1990s, sends 250 gallons of boiling water through the pipe to Reykjavík every second, and also generates electricity. For a better look, take your pick of two overlooks: one at the end of a little dead-end side lane, and the other reached by short paths from a parking lot by the side of the road. (Another power plant—Hellisheiði, at the conclusion of this Golden Circle spin—has a real visitors center; see here.)

The highway descends steeply into the valley, ending at a T-junction with highway 360, where you’ll turn left toward Þingvellir. (Note that if you’re doing the Golden Circle in reverse, highway 435 is signposted here only as Hengilssvæði.)

Now the road winds tightly along the shore of Þingvallavatn lake, with fine views, no guardrails, and several narrow, blind summits. You’ll pass some nice summer homes. Building here is forbidden, but houses constructed before the ban were grandfathered in. Eventually, the road leaves the lake and ends at a junction with highway 36, where you’ll turn right; from this junction, it’s another four miles to Þingvellir.

The gorge at Þingvellir (THING-VETT-leer), dear to all Icelanders, is both dramatic and historic. It’s dramatic because you can readily see the slow separation of the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates—the earth’s crust is literally being torn apart. And it’s historic because, during the Settlement Age, it was here at “Assembly Plains” (as its name means) that chieftains from the different parts of Iceland gathered annually to deal with government business (at a meeting called the AlÞingi). Today the area has been preserved as a national park. Visitors can walk along the rifts created by the separating plates, stand at the place where the original Icelanders made big decisions, hike to a picturesque waterfall, see a scant few historic buildings, and even go for a snorkel or scuba dive into a flooded gorge (book ahead).

Cost and Hours: Park—free and always open, tel. 482-2660; visitors center—free and open daily 9:00-20:00, Sept-May until 18:00, tel. 482-3613, www.thingvellir.is.

Arrival at Þingvellir: Regardless of which route you took from Reykjavík, you’ll wind up on the same road as you approach Þingvellir. You can park on either the upper (west) or the lower (east) side of the Öxará river. The two sides are no more than a half-mile apart if you use the footbridges over the river, but a five-mile drive by car. Parking is 500 ISK for the entire day (machines take credit cards; if you have trouble paying, go into the visitors center for help).

The first turnoff you’ll reach is the large P1 parking lot on the upper side, with a pay WC; on maps, this spot is sometimes called Hakið. If it’s not too crowded, it’s easiest to park here, stop in at the visitors center, get oriented at the overlook, then hike down to the sights.

If you can’t find a spot at P1, continue a few miles to the intersection with the park offices/café; turn right—onto road 361—to reach several smaller parking lots on the lower side (P2, P4, P5, and a lot for Silfra divers). This area is less congested and more convenient for picnicking. (Lot P3, which you’ll see along the main road between P1 and the others, is designed for hikers who want to take the Langistígur path, which descends into the fissure near the big Öxarárfoss waterfall.)

If you’re with a group, consider drawing straws and having the loser drop everyone off at P1 (allowing them the convenience of a one-way stroll); the driver can park at one of the lower lots and hike up to meet the group.

Length of This Visit: For a quick visit, you can enjoy the overview, hike the gorge, and see the Law Rock in less than an hour. Add a half-hour to hike up to the waterfall (about a mile one-way from P1), and a half-hour to cross the river to the church (the least interesting and most skippable).

Eating: In good weather, Þingvellir is a nice place for a picnic. There are benches, wooded areas, and free portable toilets near P2 and P5. If you want to picnic here, B.Y.O.—the visitors center (at P1) has a very basic $ snack stand with premade sandwiches. Otherwise, the only eatery nearby is the $ café at the national park office a couple of miles away, at the junction of highways 36, 361, and 550. It’s small and sometimes crowded, but acceptable in a pinch (daily 9:00-22:00, Sept-May until 18:00).

This plan assumes that you’re parking at the upper P1 lot (even if you park elsewhere, hike up here to begin your visit since it offers a nice overview). Start at the visitors center, where you’ll find a modest and free exhibit with helpful maps for getting your bearings.

• Exiting the visitors center, walk over to the overlook with the railing.

1 View Over Þingvellir: Look down at the lake and the land that’s subsided to its north. You can see how the Öxará (“Ax River”) empties into the lake. Þingvellir’s church (and some ruins of the old chieftains’ encampments) lies just across the river below you. The five-gabled farm building dates from 1930.

Directly below you is Þingvellir’s great fissure; look at how the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates are moving apart. Imagine pulling a big, chewy cookie apart very slowly; you’d start to see cracks in the dough, and eventually crumbs would start to slide into the gap. Here, you can see long, narrow fissures in the earth, running roughly north-south. The lake itself sits in the largest fissure of all. The lake bed (and the land to the north and south) basically has slid into the gap between the plates. The deepest parts of the lake bed are actually below sea level.

• Follow the boardwalk as it switchbacks down between the cliffs, descending through the little side channel that leads into...

2 Almannagjá (“Everyman’s Gorge”): As you walk, you’re tracing the boundaries of continents. To your left is America. To your right is Europe. You may see brochures claiming that at Þingvellir you can “touch America with one hand and Europe with the other,” or jump between the continents. The idea inspires fun photographs, but it’s not quite true: The whole area is shaped by the interaction between the two tectonic plates, and no single fissure forms the boundary between them.

On the left, the vertical cliff face is original rock as it was laid down by volcanic eruptions and compressed over the eons. On the right, you can see how the rock—once even with the cliff on your left—has fallen away into the gap due to the subsidence that also created the lake. On the right (fallen) side of the gorge, you can scramble out to various walkways and viewpoints.

• As you approach the valley floor, follow the boardwalks to the right to stand in the area just below the flagpole. This marks the likely location of...

3 The Law Rock (Lögberg): Within about 60 years of the first settlements, Iceland was home to somewhere between 10,000 and 20,000 people—almost all of them farmers, scattered across the island on isolated homesteads. In about A.D. 930, local chieftains (goðar) began to gather at an annual meeting called the Alþingi (“all-thing”), which took place more or less where you’re standing. For this reason, Þingvellir can be thought of as Iceland’s first capital. Today, this site remains important for Icelanders—it’s their Ancient Agora, their Roman Forum, their Independence Hall.

Gaze over the marshy delta below you, and time-travel back a thousand years. It’s the middle of June, and you’re surrounded by fellow chieftains, some having traveled on horseback more than two weeks, over challenging terrain, just to be here. Each chieftain has brought along an entourage of þingmenn (assemblymen). The field below you is dotted with temporary turf huts.

The meeting is about to begin, and you’re immersed in a hairy mosh pit of hundreds—maybe thousands—of unwashed Norsemen (and Norsewomen). The collective body odor is overwhelming. But for two weeks, you’ve all agreed to set aside your grudges and work together to find consensus on critical issues of the day. This is your one chance all year to learn the latest news and gossip. And while everyone’s here, there are sure to be some big parties, business wheeling and dealing, marriages arranged...and, quite likely, some duels. Merchants, tradesmen, and panhandlers are milling about, trying to drum up a little business. The whole event has a carnival-like bustle.

The crowd quiets with the appearance of the allsherjargoði (grand chieftain)—a direct descendant of Ingólfur Árnason (who was, according to the sagas, the first Icelandic settler of Reykjavík). As the high priest of the Norse pantheon, the allsherjargoði calls the assembly to order, and sanctifies the proceedings before the gods. Then the “law speaker” (lögsögumaður) takes his position at the Law Rock and recites the guidelines for the assembly, outlines the broad strokes of Icelandic law, and recaps the highlights of last year’s session. The acoustics created by the cliff behind him help bounce his voice across the throngs; other speakers, strategically located at the back of the crowd, carefully listen to, then repeat, whatever the law speaker says.

As the Alþingi continues, the law speaker also presides over the Law Council (Lögrétta), on the opposite riverbank. A more select group of chieftains reviews and debates existing legislation, and weighs in on legal disputes, and the law speaker is responsible for memorizing whatever is decided. (Mercifully, he serves only a three-year term.) Eventually, Christianity brings literacy and the Latin alphabet, and the law speaker’s role gives way to that of a sort of “high attorney”—lögmaður.

The Alþingi gatherings took place throughout the Commonwealth Era. But things changed after 1262, when the chieftains entered into union with Norway—pledging fealty to the Norwegian king under an agreement called the Old Covenant. The Alþingi still convened annually at Þingvellir, but morphed into an appeals court; it continued this way until 1798.

Þingvellir became a national park in 1930, to celebrate the millennial anniversary of the first Alþingi. And in 1944, the modern, independent Republic of Iceland was proclaimed right here. The stands below the flag are for official ceremonies; one of the information boards at the railing displays photographs of some of these ceremonies.

By the way, those original settlers couldn’t possibly have known that the place they selected for their gathering also happened to straddle America and Europe. They chose this site mainly because it had recently been seized from a convicted murderer and designated for public use. Þingvellir is also fairly central (relatively accessible in summer from every corner of Iceland) and had ample water, grazing lands, and firewood to supply the sprawling gatherings. Its location along the cusp of continents is just one of those serendipities of history.

• Follow the wide, gravel path straight ahead, and cross the river on a small bridge over a waterfall (the bottom end of Öxarárfoss, which we’ll visit next). To your left is Drekkingarhylur (“Drowning Pool”), where women suspected of witchcraft were drowned between the late-16th and mid-18th centuries.

If you’re short on time, you could turn back here. Ideally, continue along the path. After about 300 yards, just before reaching parking lot P2, branch off on the small path to your left. Follow it for a few minutes as it crests the rise to your left. Then, a hundred yards to your left, is the large waterfall called...

4 Öxarárfoss: This is where the river—which rises up on the plateau—plunges over the cliff face into the valley. Old sagas say that the early settlers changed the course of the river to improve the water supply at Þingvellir, but no one is exactly sure whether this is true and how that might have been done.

• You’ve already seen the most interesting parts of Þingvellir—you can head back the way you came (past the P2 lot). With more time, cross the footbridges on your left (below the Law Rock) to reach the...

5 Church and Cemetery: The current church was built in 1859, but there were churches here for centuries before. The original church was supposedly built using timbers sent here from Norway’s St. Olaf (King Olav II, 995-1030). If the church is open, step inside to see the humble, painted interior (generally closed Sept-May). Local parishioners lie in the small cemetery in front of the church. The multigabled house just beyond it, called Þingvallabær, was built in 1930 as a residence for the local priest, who was also the park warden. It’s now used for ceremonial functions.

Behind the church, the round, elevated area up the stairs is a cemetery lot. This was planned as a resting place for national heroes, but the idea never took off, and only two people (well-known writers) were ever buried there.

Along the riverbank near the church, the mounds contain the remains of the temporary dwellings that were set up here each year for the annual assembly. From here, looking back the way you came, enjoy great views of the sheer cliff that defines the fissure.

• Between the church and the river, a waterside path allows further exploration. Following this path takes you to the P5 lot, where a steep shortcut (on a rocky path through the woods) leads back up to the P1 lot where you started. (Also nearby is Silfra, a favorite destination of divers—described next.) For an easier route, you can backtrack along the river, then take the bridge on your left to reach the Law Rock, then hike back up through Everyman’s Gorge.

One of the many fissures at Þingvellir, Silfra is renowned among snorkelers and scuba divers for the clarity of the water. Thanks to the purity of the glacial water that fills it, you can see underwater for more than a hundred yards.

To snorkel or dive in Silfra, you’ll need to join a tour (such as those offered by Dive.is, the largest operator). Snorkelers must be relatively fit and comfortable in the water, while divers need to be certified and experienced. There have been a few fatal accidents at Silfra in recent years (even involving snorkelers)—don’t overestimate your abilities.

The water is a constant 35-39°F, so you’ll be outfitted with some serious gear: a neoprene dry suit, hood, gloves, fins, mask, and snorkel. (The better companies have basic changing cabins in the parking lot; otherwise, there’s limited privacy.) The suit keeps your body warm enough, but expect your face to go numb and your hands to get cold. After changing into your gear, you’ll walk a few minutes to the entry stairs and descend into the fissure with your guide. A gentle drift current slowly takes you along the fissure and into a lagoon, where you’ll need to kick against the current to U-turn to the metal exit stairs. You’ll be in the water for about 30-40 minutes (prices for Dive.is: 20,000 ISK for guided snorkeling, extra 5,000 ISK for pickup in Reykjavík, 35,000 ISK for package that includes pickup, Silfra, and bus tour of Golden Circle, more for divers; tel. 578-6200, www.dive.is).

Getting There: Silfra is at the lakeshore near the east bank of the river. The entry point to Silfra is between parking lots P4 and P5. Follow the directions on here (turning off onto road 361 to reach this area) and look for the designated lot.

This section of the drive circles around the far end of the lake, where you can clearly see the intercontinental rift—as if God dropped his hoe and dredged out a tidy furrow between America and Europe.

• Leaving Þingvellir, return to highway 36 and continue east for about 10 minutes around the lake’s north shore, crossing smaller fissures. Soon you’ll pass the intersection with road 361 (a right turn here takes you back to Þingvellir’s lower parking lots) and, immediately after that, the national park office, with a café.

Continuing along the east side of the lake, you’ll reach a point where highway 36 turns off to the right. Stay straight toward Laugarvatn on highway 365. This road crosses an upland heath called Lyngdalsheiði at about 750 feet above sea level (if the road is closed, see “Weather and Road Conditions” under the “Golden Circle Tips” on here for an alternate route).

On your left, enjoy some otherworldly, craggy mountain scenery—the Kálfstindar ridge. A half-hour after leaving Þingvellir, you’ll reach a roundabout. Follow signs onto route 37 toward Geysir (not Selfoss) to descend into the sleepy, unassuming village of Laugarvatn.

Set by a small lake of the same name, Laugarvatn was long the home of Iceland’s college for sports teachers (the program has now been moved to Reykjavík), and has many summer cottages owned by the country’s labor unions for use by their members. There are hot springs in and around the lake, and Fontana, a nicely designed premium bath, makes good use of them.

Fontana Thermal Baths: Sitting right along the Laugarvatn lakeshore, Fontana is one of Iceland’s few “premium” baths (and worth ▲)—a step up in comfort (and price) from municipal swimming pools, and a bit more tourist-oriented. Beyond the visitors center—with ticket desk, changing rooms, and a good cafeteria—is the outdoor bathing area, overlooking the lake. The complex has three modern, tiled pools, artfully landscaped with natural boulders, as well as a steam room (where you can hear the natural hot spring bubble beneath your feet), and a dry sauna. To cool off or get a change of pace, bathers are encouraged to take a dip in the thermal waters of the lake (4,200 ISK, mid-June-mid-Aug daily 10:00-23:00, mid-Aug-mid-June daily 11:00-22:00, tel. 486-1400, www.fontana.is).

For some, Fontana may be a good alternative to the Blue Lagoon—it’s cheaper, smaller (easier to navigate), less pretentious, much less crowded, and doesn’t require reservations. But it’s also less striking—more functional than spa-like—and lacks the Blue Lagoon’s romantic, volcanic setting. Thermal bath fans may want to do both. You can fit the Golden Circle and a leisurely soak at Fontana into a single day if you sightsee quickly and skip the minor stops.

“Thermal Bread Experience”: Fontana follows the Icelandic tradition of baking sweet, dense rye bread right in the thermal sands at its doorstep. Twice daily, you can pay to join the baker as they dig up a pot of bread, then taste it straight out of the ground (1,500 ISK, daily at 11:30 and 14:30). But note that you can eat the very same bread as part of their regular lunch buffet.

Nearby Thermal Beach: The lake in front of Fontana—heated by natural hot springs—is free to bathe in (at your own risk). Facing the lake, head right to find a small, black sand beach next to the fenced-off geothermal area (keep well clear of this area of boiling-hot water). The water near the springs is warm, but it gets colder as you go deeper. At a minimum, consider rolling up your pants and dipping your feet. On the wooden walkway between the geothermal plant and the lakeshore, notice—but don’t touch—little boiling pools in the mud.

Eating in or near Laugarvatn: This village is a good place for lunch along the Golden Circle route. One of the best options is the $$ Fontana Thermal Baths cafeteria, in the bath’s entrance lobby, and open to the public (no bath entry required). You can get unlimited soup and bread for 1,500 ISK, or spring for their full 3,500-ISK lunch buffet (more expensive at dinner, daily 12:00-14:30 & 18:00-21:00). There are a few other places to eat in town and a small grocery store.

Or consider driving 10 more minutes to $$ Efstidalur II (“Uppermost Valley”), a large, family-run restaurant located on a dairy farm just off highway 37 between Laugarvatn and Geysir. The upstairs section specializes in burgers and has pricier main courses. Downstairs is the ice cream counter, with windows overlooking the cows in the barn. It’s a popular, bustling place—family-friendly and often crowded with groups (daily 11:30-21:00, mid-Sept-mid-May until 20:00, well-signposted up a gravel driveway, tel. 486-1186, www.efstidalur.is).

• From Laugarvatn, highway 37 leads 20 minutes onwards to the geothermal field at Geysir (passing the Efstidalur II eatery described earlier). Along the way, the road changes numbers to highway 35.

When people around the world talk about geysers, they don’t realize they’re referencing a place in Iceland: Geysir (GAY-sear), which literally means “the gusher.” While the original Geysir geyser is no longer very active, the geothermal field around it still steams, boils, and bubbles nonstop, periodically punctuated by a dramatic eruption of scalding water from the one predictably active geyser, Strokkur. Watch Strokkur erupt a couple times, look at the rest of the field, use the WC, and then continue on.

Cost and Hours: Free and always open.

Safety Warning: Make sure to keep children very close; hold their hands whenever possible. Impress upon them that they should not touch any of the water, which is boiling hot, and that they must stay behind the ropes. At Strokkur, standing upwind will keep you out of any spray.

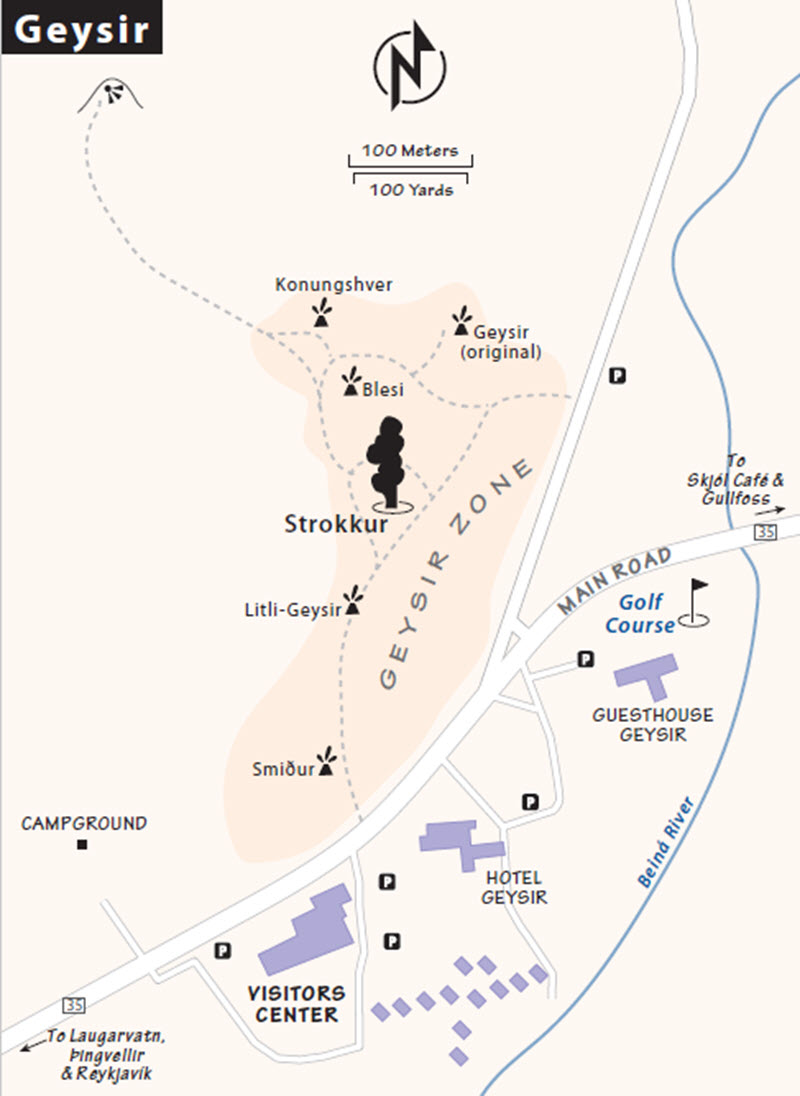

Arrival at Geysir: Approaching Geysir, you’ll see the geothermal field on your left, and a visitors complex with parking lots on your right. Park as close to the geothermal field as you can (the lots at the far end of the visitors center are closer to the best geyser action), then walk across the road and explore.

Services and Eating: Across the road from the geothermal area is a complex with a clothing and souvenir store, free WCs, a golf course, two hotels, and a handful of restaurants at different price ranges. While these are OK, I’d opt for one of the Laugarvatn eating options (described earlier), or wait for $ Skjól (“Shelter”), a café connected to a hostel and campground along highway 35 between Geysir and Gullfoss (just before the junction with highway 30). Talkative owner Jón Örvar is known for making good, affordable, splittable pizzas; he also serves other simple meals like burgers and fish-and-chips. This place attracts many hikers and outdoorsy folk (June-Aug daily 9:00-14:00 & 18:00-23:00, shorter hours off-season, mobile 899-4541, www.skjolcamping.com).

Visiting Geysir: The geothermal field itself lacks the boardwalks and other maintenance you would normally expect at a sight this popular. That’s due in part to a dispute between the government (which owns part of the site) and private landowners, who have been bickering publicly for years about whether to charge for parking and admission. Outdoor signboards explain the geology.

The area’s centerpiece is a geyser called Strokkur (“Butter Churn”), which erupts about every 10 minutes (but don’t set your watch by it). The eruptions themselves, which shoot about 50 feet in the air, are relatively short—in every sense—and won’t wow anyone who has seen Old Faithful at Yellowstone. What’s nice about Strokkur, though, is the short wait between gushes, and how close you can get. Each eruption is a little different. It’s surreal to stand around in a field with people who have come from the far reaches of the globe, just to share this experience...of staring at a hole in the ground. Everyone huddles in a big circle around Strokkur, cameras aimed and focused, waiting for the unpredictable spurt. When it finally happens, it’s over in a couple of seconds, as abruptly as it started. After each show, the crowd thins out a bit, and new arrivals shuffle in to take their place, shoulder-to-shoulder, cameras cocked, waiting...waiting...waiting.

Just a few yards up the hill above Strokkur, check out a few other fumaroles and hot pools, including Konungshver and the colorful Blesi. The miniature Litli-Geysir, along the path from the main parking lot, bubbles and boils but doesn’t erupt.

Steaming uneasily off to the side is the original “great” Geysir. This was the only one known to medieval Europeans, and is the origin of the word geyser. It was dormant for most of the 20th century, but after a nearby earthquake in 2000 it started erupting occasionally. It blows higher and longer than Strokkur, but rarely and unpredictably, so don’t expect to see anything. (Geysir is on the far side of the field if you’re coming from the main parking lot; there’s another, smaller parking lot close to it.)

For a commanding view over the Geysir area, continue past Konungshver, climb over the stile, and make your way 10 minutes up to the top of one of the rocky outcroppings that overlook the geothermal field and surrounding terrain. The snowy mass of Vatnajökull looms to the west.

• From Geysir, continue to the Gullfoss waterfall, a straight shot 10 minutes onward along highway 35.

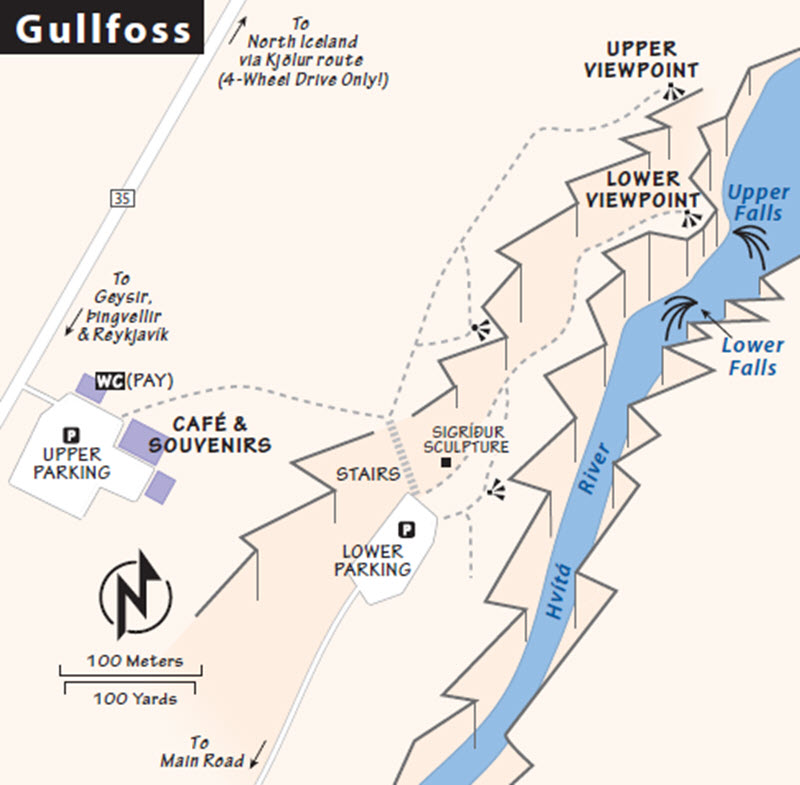

The thundering waterfall called Gullfoss (GUTL-foss, “Golden Falls”) sits on the wide, glacial Hvítá river, which drains Iceland’s interior. The waterfall has two stages: a rocky upper cascade with a drop of about 35 feet, and a lower fall where the water drops about 70 feet straight down into a narrow gorge. Somewhat unusually for a waterfall, the gorge runs transverse to the fall line, effectively carrying the water off to the side. Dress warmly: Cold winds blow down the valley, and the spray from the falls can soak you. Winter visitors should watch for slippery areas. If you have ice cleats, this is a good place to put them on.

Cost and Hours: Free and always open, tel. 486-6500, www.gullfoss.is.

Arrival at Gullfoss: Two different viewing areas—connected by a wooden staircase—let you admire the falls; each has its own free parking lot and viewpoints. Both are equally worth seeing, but if you’re short on time, focus on the lower one—which lets you get up close and feel the spray. To quickly hit the lower viewpoint, as you approach the area, just after the blue P sign, watch for the unmarked right turn to the lower parking lot. With more time, continue to the official, well-signed upper parking lot, with pay WC, café, and gift shop (with free WCs for customers).

Eating: The large $ café by the upper parking lot serves soup (their bottomless bowl of lamb soup is popular), salad, and sandwiches (daily 9:00-21:30, Sept-May 10:00-18:00).

Visiting the Waterfall: From the upper parking lot, boardwalks lead along the edge of the plateau, high above the falls, to a couple of good upper viewpoint spots. On a clear day, you can see glaciers in the distance. The view upriver gives a sense of Iceland’s vast, lonely interior Highlands.

From here, stairs lead down to the lower viewpoint. This area gets you close to the falls. It’s closed in winter, when ice can make it dangerous (don’t try it). A narrow trail leads through the spray from the falls to a level area between the upper and lower stages of the waterfall. If you walk out here with children, keep them close.

It would be easy to dam or divert the river above the falls for electricity generation. In the early 1900s, British investors tried to buy the waterfall, but their plans fell through. The government acquired the land and the falls have been left in their natural state. Near the base of the staircase, look for the relief sculpture of Sigríður Tómasdóttir, a local farmer who helped thwart plans for the dam.

This stretch features a few mildly interesting stops to consider on the way (all described next)—but if you’re in a hurry, these are skippable. It’s about one hour from Gullfoss to Selfoss, then another 45 minutes back to Reykjavík (without stops).

For a late lunch, consider $$ Friðheimar (“Peaceful Homes”), a very popular, borderline-pretentious tomato farm 30 minutes from Gullfoss, offering lunch daily (12:00-16:00) right in the greenhouse, surrounded by rows of tomato plants, with pots of fresh basil on each table. The brief menu is all tomato: tomato soup with bread, fresh pasta with tomato sauce, and tomato ice cream or cheesecake with green tomato sauce (popular with tour groups—reservations strongly recommended, along highway 35 in the village of Reykholt—just north of junction with highway 31, tel. 486-8894, www.fridheimar.is).

• From Gullfoss, turn back along highway 35 and pass by Geysir again. Shortly after Geysir, make a left turn to stay on highway 35 toward Reykholt and Selfoss. Your next big stop along the route is the Kerið crater (see here), about 45 minutes from Gullfoss. Along the way, consider the detours described next.

The next three sights—a thermal pool, a church, and a petting zoo—are short detours from highway 35 and the main Golden Circle route.

Claiming to be the “oldest swimming pool in Iceland” (from 1891), the Secret Lagoon is a big, rustic, three-foot-deep, 100°F pool in front of a dilapidated old house (with a modern entrance/changing facility). The pool is surrounded by an evocative thermal landscape; a boardwalk leads around the pool, past steaming and simmering crevasses. Greenhouses stand nearby. Compared to the over-the-top-romantic Blue Lagoon, or even Reykjavík’s municipal swimming pools (which are one-third the price), this is a very straightforward experience: Its proximity to the Golden Circle and clever marketing make it more popular than it probably should be. On the other hand, the bathers here seem very happy—sipping drinks, bobbing on colorful pool noodles, happy to enjoy this après-Golden Circle hangout. Far from “secret” (it’s included on several day tours from Reykjavík), the pool can get quite crowded with a younger clientele. It’s smart to reserve ahead online—when it’s full, it’s full.

Cost and Hours: 2,800 ISK, daily 10:00-22:00, Oct-April 11:00-20:00, last entry one hour before closing, tel. 555-3351, www.secretlagoon.is.

Getting There: The Secret Lagoon is a 10-minute drive off the main Golden Circle route. From highway 35, just before the village of Reykholt, turn left at highway 359, signed Flúðir. Follow this about five miles into the small village of Flúðir, watching on your left for the turnoff to Hvammur and Gamla Laugin. The Secret Lagoon is tucked amid the big greenhouses, on your right.

This church was the old seat of the bishopric of southern Iceland. The current church was built in the 1960s and is flanked by a retreat center run by Iceland’s Evangelical Lutheran state church. Unless you’re heavily into Icelandic history, this is a low-key site—worth a few minutes only if you want to mix something non-geological into your day.

Cost and Hours: Church entry-free, 300 ISK donation requested if visiting crypt—OK to put foreign bills in the box; daily 9:00-18:00, pay WC in complex next to church, tel. 486-8870, www.skalholt.is.

Getting There: About 30 minutes south of Gullfoss on highway 35, detour left onto highway 31 for a couple of minutes, following Skálholt signs through farm fields. The church is just over the hill, overlooking a lake-and-mountain panorama.

Visiting the Church: As you drive up, you can see from the rich farmland around the church how it was able to support a medieval religious community. Almost nothing is left of the original buildings, many of which were destroyed by earthquakes in the late 18th century. It’s peaceful here, and tour buses bypass the place. The locally designed stained-glass windows in the church are very colorful.

If you visit, be sure to go downstairs to the crypt, with a small exhibit of historical and archaeological artifacts. There’s also a period sketch of the 18th-century church, which survived the earthquakes but was torn down soon after. From the crypt, you can exit directly outdoors through the only original part of the building, a short tunnel (a feature also found in some other medieval Icelandic buildings). An old-style, turf-roofed wooden chapel on the grounds is usually open (but empty).

Slakki is a combination petting zoo and indoor minigolf complex, housed partly in cute buildings meant to look like a typical old-style Icelandic farm. It’s best for little kids between ages two and seven. There’s a decent café, tiny playground, and good photo ops, and kids can get to know a big, noisy, green parrot. Families with small children could make this their main target for a Golden Circle day trip...and still manage to glimpse some of the better-known sights on the way.

Cost and Hours: Adults-1,000 ISK, kids-500 ISK, daily 11:00-18:00 in summer, May and Sept Sat-Sun only, closed Oct-April, off Skálholtsvegur in the hamlet of Laugarás, tel. 486-8783.

Getting There: The zoo is less than a mile past Skálholt Church along highway 31.

• To continue to the Kerið crater on highway 35, after passing Skálholt, drive about 15 minutes, then watch for the little Kerið sign, which comes up very quickly (you might see an Icelandic flag and people hiking along a ridge on your left as you approach).

The most worthwhile stop on the way back to Reykjavík is a volcanic cone, from an eruption about 6,500 years ago, that has collapsed and filled with water—creating a tiny crater lake. It’s right next to (but not visible from) the road. It’s vividly colorful: red walls draped with green vegetation, overlooking deep aquamarine-blue water. You can see it in a single glance, take a half-hour to walk around the rim, or descend 150 feet down a set of stairs to the surface of the lake.

As Kerið (KEH-rithe) is on private land, it’s unusual among Iceland’s outdoor sights in charging admission (which caused a great stir when it was announced). But it’s cheap, and the owners have improved the parking lot and pathways; most visitors find it worth the cost.

Cost and Hours: 400 ISK when staffed, not staffed at night or in darkness, mobile tel. 823-1336, www.kerid.is.

Nearby: About five minutes north of the crater is the Borg public swimming pool, in the Borg sports complex at the junction of highways 35 and 354, between Skálholt and Kerið—look for the water slide just past the main turnoff into the hamlet of Borg (1,000 ISK; June-late-Aug Mon-Fri 10:00-22:00, Sat-Sun until 19:00; otherwise Mon-Thu 14:00-22:00, Sat-Sun 11:00-18:00, closed Fri; tel. 480-5530, www.gogg.is).

• As you head south from Kerið toward Selfoss on highway 35, you’ll drive past a dramatic slope on your right. Look at the mountainside to see the huge boulders that have slid down the slope over the ages—and see if you can spot the one lonely summer house taking its chances among them. About 15 minutes after Kerið, you’ll reach...

Selfoss (pop. 7,000) is the largest town in southern Iceland, and set next to rapids on the Ölfusá river. (The water that flows over Gullfoss winds up here.) The Golden Circle route bypasses the town center, which is fine as there’s not much to see, but you can easily drive across the bridge if you need to stop for supplies. Chess fans enjoy visiting the grave of troubled grandmaster Bobby Fischer in the Laugardælakirkja churchyard a mile northeast of Selfoss.

Eating near Selfoss: If you’re in the mood for langoustine-by-the-sea, it’s about a 15-minute detour to two humar-focused restaurants: Fjöruborðið, in the seaside village of Stokkseyri, and Hafið Bláa. For locations, see map on here.

• It’s a 45-minute drive from Selfoss back to Reykjavík. At the main roundabout in Selfoss, turn right onto highway 1. Soon after leaving Selfoss, on the left you’ll see 52 white crosses at the base of a conical hill (Kögunarhóll). These commemorate motorists and pedestrians killed on this busy, poorly lit road—statistically one of Iceland’s most dangerous—between 1972 and 2006. Consider this a sobering reminder to drive with extra caution.

In a few minutes, you’ll approach the small town of Hveragerði. While the town itself (pop. 2,000) is dreary, it sits at the mouth of a valley with evocative hillsides and offers an opportunity to hike to a thermal river (Reykjadalur); the town also has a great brewery/pizzeria (both described later). To stop at these, turn off highway 1 and follow the main drag all the way through Hveragerði. You’ll come out at the upper end of town and keep going, following Reykjadalur signs about 2.5 miles, until the road dead-ends at the Reykjadalur parking lot, with a little café and basic WCs.

This natural thermal area—literally “Steamy Valley”—is aptly named. For outdoorsy hiker/bathers, Reykjadalur (RAKE-yah-dah-lrr) is worth ▲▲. The hike to the river is just over two miles one way along a well-maintained path, with a 600-foot elevation gain (allow at least three hours total for this experience).

Stepping out of your car at the end-of-the-road parking lot, you’re surrounded by steaming hillsides. From here, cross the bridge, then hike approximately one hour up the valley. Eventually you’ll reach some basic changing cabins next to a hot stream. The water is shallow—you’ll need to lie down to be submerged—but wonderfully warm. Reykjadalur is far from undiscovered, so you’ll likely have plenty of company. Relax and enjoy the experience...but remember it’s an hour’s hike back down to your car. The little café in the parking lot, Dalakaffi, is a nice place for cake and coffee (Sun-Fri 13:00-18:00, Sat from 11:00, www.dalakaffi.is).

Warning: Stay on marked paths at all times. This entire area is very geologically active, and anyone wandering off the path could end up stepping into a hidden, underground pool of boiling water.

Eating in Hveragerði: The main reason to visit nearby Hveragerði is to eat at $$ Ölverk (“Beerworks”), a wonderful little microbrewery/pizzeria tucked in a dreary strip mall a couple of blocks into town. In addition to a chalkboard menu of their own beers, and some others by local brewers, they dish up tasty pizzas from a brick oven. Casual and family-friendly, it works well for an easygoing, memorable dinner on your way back to Reykjavík (daily 11:30-23:00, take the main road through Hveragerði and watch for the pizzeria on your right at Breiðumörk 2b, tel. 483-3030, www.olverk.is).

• Leaving Hveragerði, the road climbs steeply in a series of wide bends to a high upland plateau (1,200 feet) called...

This plateau separates southern Iceland from the Reykjavík area. The weather can be dodgy up here, so check the road conditions in advance. About halfway across the plateau, you’ll see pipes and steam from Hellisheiðarvirkjun, a geothermal plant owned by the Reykjavík energy utility; if it’s not too early or late in the day, you could stop at the visitors center (see here). From here, it’s less than 30 minutes—across a lunar landscape—to Reykjavík. On your way into town, consider stopping in the suburb of Hafnarfjörður for dinner (see recommendations in the Reykjavík chapter).