Though major restoration work still takes place from time to time at temples, royal palaces, and historic buildings today, the residential hanok is enjoying a minor revival in popularity, with building sites popping up occasionally in older areas of Seoul and parts of the countryside. Books addressing the technical aspects of building hanok have appeared in popular stores, demonstrating that the hanok is now a contemporary lifestyle option rather than a relic from a bygone era. South Korea is also home to several hanok schools, teaching aspiring carpenter-builders the necessary skills for carrying on Korea’s architectural tradition. This chapter offers a look at the characteristic elements of Korea’s traditional architecture; the process involved in building a basic residential hanok; the principal materials used; and the architects involved.

ELEMENTS OF KOREAN ARCHITECTURE

Roof

The roof could be Korean traditional architecture’s most distinctive feature. Though widely identifiable by their rows of dark grey tiles, hanok roofs can be divided into several principle categories:

Paljak (hip-and-gable) roof: The most advanced style of hanok roof to have been developed, paljak roofs can be found on many of Korea’s best-known traditional buildings, including Geunjeongjeon Hall in Gyeongbokgung Palace. Many important buildings, including palaces, Confucian academies, and the homes of members of the traditional nobility, use this roof type. In highly stratified Joseon society, the paljak roof was reserved for the highest class.

Paljak roof

Matbae (gambrel) roof: This simple form of roof was the first to be developed in what is now considered to be Korean traditional hanok architecture. Perhaps the most important example of a building with a matbae roof is the Goryeo-era Geungnakjeon at Bongjeongsa Temple in southeastern Korea, believed to be Korea’s oldest surviving wooden hanok building. This style of roof is often found in sadang buildings, used for conducting Confucian ancestral rites.

Matbae roof

Ujingak (hipped) roof: Found mostly on private homes, the ujingak roof can also be seen on palace gates. A well-known example of this is Gwanghwamun, the recently restored main gate of Gyeongbokgung Palace in central Seoul. Most choga (thatched) roofs are also built in ujingak form.

Ujingak roof

Moim (gathered) roof: Another type of hipped roof is the moim, or “gathered” roof, where each face narrows as it rises to form a tip. This type of roof somewhat resembles the ridges and faces of an umbrella. It is found on polygonal structures such as Hyangwonjeong Pavilion in Gyeongbokgung Palace.

Moim roof

Geunjeongjeon Hall, Gyeongbokgung Palace

A Confucian shrine

Gwanghwamun Gate

Hyangwonjeong Pavilion

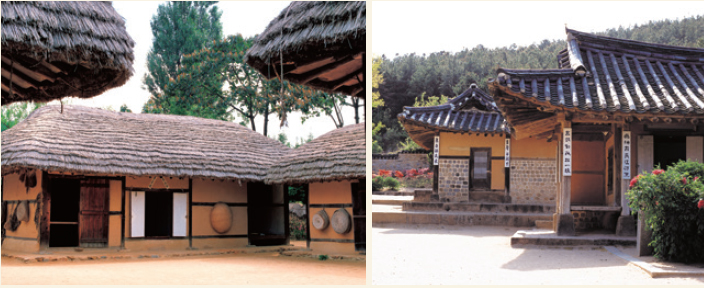

CHOGAJIP AND GIWAJIP

Choga (thatched) roofs were popular among farmers and low-income classes in traditional society. Following the autumn harvest, rice straw was cheap and abundant and therefore used as a material for thatching. Certain climbing plants, such as gourds and pumpkins, could also be grown on top of choga roofs. One major disadvantage of rice straw, however, was that it could rot and deteriorate quickly when exposed to the elements. To lay a choga roof, first, a layer of earth was spread on wooden roof boards, which was followed by a layer of clay mixed with cut grass. Next, rice straw was spread across the roof and tied down.

Giwa (tiled) roofs were more durable than choga roofs and used to signify the importance of the building, as well as the higher status of its occupants. In traditional times, Korea had plenty of clay for making tiles and plenty of firewood for fueling tile kilns; this contributed to the popularity of tiles for roofing. For aesthetic reasons, tiles were produced in a variety of shapes and sometimes imprinted with patterns. To lay a giwa roof, a thick layer of earth was first spread over the wooden roof boards that had been laid over the purlins and rafters. Alternate interconnecting vertical rows of “male” and “female” tiles were then laid over the earth.

One striking feature of hanok is that the roof appears much bigger than the structure underneath. This is to protect the entire building in various types of weather. In summer, hanok roofs provide shade with their wide eaves and protect the walls and windows from the monsoon rain; in winter, they offer shelter from wind and snow and help provide a feeling of warmth.

Choga (left) and giwa (right) roofs

Columns

Columns can be regarded as the most important part of Korean architecture, inasmuch as they hold up the roof, walls, doors, and windows. In traditional times, a special ceremony called ipjusik (column erecting ceremony) was held on the day the columns were first put up. Great care was taken when preparing columns. During construction, they were always oriented according to the aspect of the tree before it was felled to prevent distortion of the column later on. Columns were erected with the original base of the tree at the bottom; this was based on the belief that standing columns upside-down would bring bad luck to the building. Inspecting the knots in the wood can determine the direction of growth; in the case of most columns, the lower end is also likely to be thicker.

Traditional columns can be found in round, square, hexagonal, and octagonal forms. Round and square columns, however, are the most common.

Different forms of column served as indications, to a degree, of social status. Round columns were found principally in royal palaces and Buddhist temples. During the Joseon era, royalty was the only social class permitted to use round columns.

Various techniques were traditionally used in Korea to make columns appear wider at the base than at the top, or to make them bulge in the center.

A wooden column at Muryangsujeon, Buseoksa, demonstrates baeheullim.

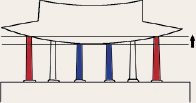

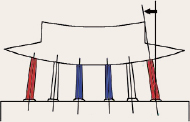

BAEHEULLIM, GWISOSEUM AND ANSSOLLIM

Korean builders employed a variety of techniques to compensate for the inadvertent optical illusions that could distort the appearance of buildings.

Baeheullim is the Korean word for entasis, the practice of making columns wider in their middle sections than at their tops and bottoms. This is generally regarded as an aesthetic device to prevent the column from looking thinner in the center and to give an impression of robust support for the heavy roof. Some have argued, however, that baeheullim may have in fact been the aesthetic by-product of making the base of the column narrower in order to reduce the amount of cumbersome preparation work needed for the foundation stone on which it would rest.

Guisoseum literally means “rising at the corners.” This term refers to the practice of making the heights of columns in a building progressively taller from the center to the corners, where they are at their tallest. This gradual height increase is of a small magnitude, barely visible to the naked eye, and varies according to the overall scale of the building. It is designed to compensate for the optical illusion that results when the columns are all of uniform height, whereby the outer edges of the building appear to sag.

Gwisoseum

Anssollim, a term that translates as “leaning inward,” describes the way columns are erected at an angle whereby they lean, very slightly, inward toward the building's center. This technique, too, is used to overcome the illusion where absolutely vertical columns at each end of the building appear to lean outward, giving an appearance of instability. This technique was used in the construction of stone pagodas as well as wooden structures.

Ansollim

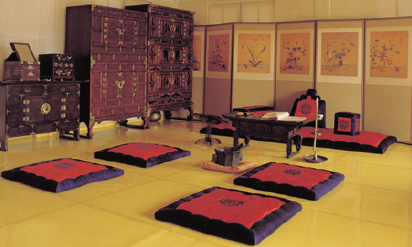

Ondol and Maru

The principal spaces in a hanok all had one of two types of floor: ondol, a type of floor heated from below by fire, or maru, a type of floor made from wooden boards with empty space beneath. Built above the ground to allow cool air to flow in from below, maru floors provided cool spaces in summer. In theory, placing a detached hanok in front of a forested mountain would allow relatively cooler air to descend from the mountain in summer and flow across the maru, creating a kind of natural air conditioning effect. This type of floor was ideal for the hot, humid parts of the southern Korean Peninsula; it was not originally a prominent feature of houses in the north.

There are several types maru that are named according to the way their floorboards are arranged. A jangmaru floor features long, parallel floorboards, while an umulmaru is made up of shorter boards, arranged side by side in rows at right angles to longer boards. Umulmaru is a type of floor unique to Korea, its structure ideal for preventing the warping that can occur due to Korea’s extreme seasonal variations in heat and humidity. It also permits the use of shorter planks.

Examples of daecheong and toetmaru

The use of different types of maru also varies according to their function and position within a hanok. The daecheong is normally the largest space in a house, situated in a central position between ondol rooms. Such a large maru space was needed to conduct jesa (Confucian ancestral rites), at which members of the extended family would gather.

The toetmaru is a narrower wooden floor that lies between the interior rooms and the ground surrounding the hanok. It is built at the same height as the interior rooms and is usually raised to a height above the ground that makes it convenient for a grown adult to sit on its edge. Shoes are removed before stepping onto the toetmaru. The jjokmaru is a narrower variation of the toetmaru, found outside some doors and windows that do not have toetmaru. Some upper-class yangban homes also featured numaru, raised maru floors that functioned like pavilions attached to the rest of the house. Like detached pavilions, numaru were normally used to entertain guests and indulge in the appreciation of scenery or composition of poetry.

Less privileged households often used deulmaru, which were simple raised wooden platform-like floor surfaces that could be moved around to convenient spots in summer, be it in the shade of a tree or next to a building.

Ondol is often cited as a truly unique feature of Korean architecture. In fact, this fire-based underfloor heating system is a source of cultural pride for Koreans, just as Korea’s unique indigenous hangeul alphabet is. It has even been cited by some Korean scholars as proof that parts of today’s northeastern China used to be the territory of earlier Korean states due to the archaeological discovery of ondol systems there.

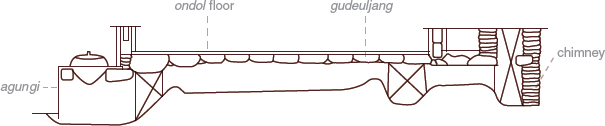

An ondol floor is made up of large stones, known as gudeuljang, covered by clay and a finish usually consisting of impervious oiled paper. Beneath the floor runs a series of flues that carry hot air and smoke from a fireplace, called an agungi, from the adjoining kitchen. The kitchen is located a few feet lower than the room and the chimney on the far side, allowing hot air to rise naturally through the flues, toward the chimney.

Agungi fireplaces in a kitchen

An ondol floor

The large stones act as storage heaters, so that a hot fire lit in the kitchen for just a few hours can be used to provide a warm floor and, hence, a warm room, throughout a cold winter’s night. Koreans often covered the floor with quilts in order to further preserve heat. The occupants of a room would place their legs under the quilt during the day, or their entire bodies at night. Ondol is thus thought to have been a contributing factor in the development of the Korean culture of sitting and sleeping directly on the floor, without chairs or beds. Flues beneath the gudeuljang were usually arranged either as parallel straight lines or in a fan-like configuration, radiating outwards from the agungi. Gudeuljang nearer the agungi generally had to be thicker than those that were further away, since the heat from the fire was greater.

Windows and Doors

The doors and windows of traditional architecture are not always as distinct as those of many Western buildings. Both are usually made of wood and translucent paper and serve to let people in and out of the building, allow air circulation, and admit light. This was accomplished in the absence of glass. Craftspeople specializing in the production of windows and doors are known as somok, as opposed to builders of the overall hanok structure, who are referred to as daemok. These respective terms roughly translate to “small carpenter” and “big carpenter.”

Hanok often featured several layers of windows, due to the limited ability of paper to contain heat and cancel noise. These came in a variety of forms, including those that were opened and closed by sliding from side to side (a form still found in most modern Korean windows); those that could be folded, lifted up outwards, and suspended horizontally from the outer ceiling or roof eaves; and other, smaller windows, usually found in auxiliary rooms such as kitchens.

Many hanok contain a variety of doors and windows.

Examples of changsal and kkotsal on windows

The most common type of window body is that made from grids of thin, interlocking lengths of wood, known as changsal. This structure combines strength with lightness, allowing the layers of paper stuck to the wooden matrix to admit light without being torn (too easily). Changsal also presents opportunities for the creation of intricate and beautiful patterns. Some hanok doors and windows even feature kkotsal, a highly decorative form that goes beyond the geometric patterns of straight pieces of wood and instead uses ornate patterns of carved flowers. Kkotsal is often found in Buddhist temple buildings.

Paper of various thicknesses is used on Korean doors and windows, sometimes in different parts of the same unit. Thicker paper admits less light and provides better protection from the elements, while thinner paper can be used to brighten the interior.

Hanok doors and windows, though not as structurally important as roofs, columns, or floors, are therefore not only vital in setting the interior atmosphere; they can also make a tremendous impression on the external view of a hanok thanks to their abundant capacity for aesthetic expression.

Gates

Gates were another important feature of Korean traditional architecture. Since hanok complexes were usually surrounded by walls, gates represented one of the only visible impressions from the outside. Their various forms were used to indicate social status.

Soseuldaemun were initially used only for the homes of public officials, but were later also built also by members of the yangban aristocracy, who did not hold office. Their tiled roofs were raised higher than the adjoining tile-topped walls at either side, both indicating the status of their owners and allowing the passing of choheon, a sort of sedan chair with a single wheel used by public officials and carried by servants. Pyeongdaemun, meanwhile, were used by those that did not hold positions as public officials. Unlike soseuldaemun, pyeongdaemun did not rise above the level of their adjoining walls.

Important buildings such as palaces, government offices, public schools, and shrines featured triple gates known as sammun. In the case of palaces and other buildings used by royalty, the central gate was reserved for the monarch.

A soseuldaemun

A sammun

Gates are very important in temples, the architecture and layout of which tend to reflect Buddhist principles and beliefs. The entrance and approach to major Buddhist temples feature three main gates. The iljumun gate, which has columns and a roof but no door, indicates the beginning of the temple. It has no adjoining walls. Though the iljumun is simple in structure and has just two columns, its roof is often ornately decorated. The sacheonwangmun houses the Four Heavenly Kings of Buddhism, usually portrayed in the form of large, colorfully painted, and extremely authoritative-looking statues of these four Buddhist gods, each one of whom watches over one cardinal direction of the world. Finally, the haetalmun represents the casting off of mental pain and the gaining of enlightenment.

Lastly, the hongsalmun is a type of gate that was used to mark the entrance to sacred sites such as royal tombs. It is much lighter in design than other gates, featuring two red columns and a few simple wooden rods arranged vertically as “spikes” along the top span. The hongsalmun is said to be red because of a former belief that ghosts disliked this color.

An iljumun

A hongsalmun

Walls

Very few stone walls remain in Korea’s rural villages today. Many were destroyed through lack of appreciation before becoming valued for their aesthetic beauty and the character they lend to human landscapes. Stone walls in villages rarely exceed human height. They were built as symbolic indicators of property limits, rather than absolute physical barriers to keep out intruders. This low height allowed occupants of the houses to look out beyond the bounds of their houses and gardens to the scenery beyond—a highly important part of Korean architecture.

Most traditional Korean walls are built from stone, earth, or brick. Earth walls were the easiest to build, but the least durable. They were usually reinforced by mixing straw and sometimes other elements, such as broken tiles, into the earth. Walls featuring patterned arrangements of broken tiles driven into the earth are known as wapyeondamjang, literally meaning “tile fragment walls.” Walls featuring highly ornate patterns, sometimes even Chinese characters, were referred to as kkotdam, meaning “flower walls.”

The famous stone wall of Deoksugung Palace

Examples of patterns in traditional walls

Stone walls, meanwhile, were deliberately built with a degree of irregularity. It was believed that curves rather than straight lines provided greater strength. Gaps between stones, meanwhile, let wind and rainwater flow through, relieving any pressure that would otherwise threaten to knock the wall over.

Hedges were sometimes grown by those without the means to build walls. Thorny plants such as taengja (trifoliate orange) and cheukbaek (Thuja orientalis) were among the popular plant species used. Such hedges were known as saengultari or sanultari, meaning “living fence.” Another popular type of fence was the ssariul, made by binding together the slender but tough branches of the ssari bush (a type of shrubby bush clover).

Gardens

In traditional times, it was common for even the most ornate hanok to be surrounded—up to their outer walls—by almost empty space. These were functional yards, rather than gardens. They were used for household chores, such as threshing rice and drying chiles, and for special social occasions, such as weddings and funerals. Small terraced gardens were sometimes built in the space behind hanok, especially in palaces and large mansions.

Koreans traditionally appreciated nature in relatively unaltered forms, however. They often built pavilions in particularly attractive natural surroundings.

There are examples of famous landscaped gardens in Korea, including Soswaewon in Damyang (see more) and Seyeonjeong, the garden of scholar-poet Yun Seon-do (1587–1671), located on the southern island of Bogildo. These gardens are sparser than many of their European counterparts, with fewer trees and plants and a greater emphasis on essential features such as streams, ponds, and existing trees.

BUILDING A HANOK

1. Determining site and aspect: Korean building tradition holds that choosing a site according to geomantic principles is so important as to constitute “half the building job.” Put very simply, the ideal site is on a south-facing slope with a mountain behind and water in front. Needless to say, this is easier to achieve outside of urban areas. Once the site has been chosen, the aspect of the hanok must be determined. As already mentioned, most aspects are southerly, perhaps turned to the southeast or southwest to avoid prevailing winds. In some cases, other aspects may be chosen in order to afford views of important mountains in other directions.

2. Groundbreaking and foundation laying: Once the site is chosen, the ground is prepared and the foundation established for the all-important wooden columns. Hanok floor plans were principally determined by establishing the distance between columns to create kan.

3. Cutting timber: This is perhaps the most important and laborious stage of constructing a hanok. Modern power tools have alleviated some of the tedium of bark stripping, planing, meticulous measurement and cutting, and repetitive yet ornate carving, but high levels of skill are still required. Master builder Shin Eung-soo has described the task as “a fight between the wood and the carpenter.”

4. Putting up columns and assembly: The base of columns is often carved to mesh exactly with the irregular surface of foundation stones by way of a skilled process known as deombeong jucho (see more). When this is done sufficiently well, columns stand straight and stable without additional support. Precut beams, purlins, and other components are then added.

5. Sangnyangsik: The sangnyangsik is a ceremony that accompanies the raising of the crucial ridge beam into place. The homeowner, carpenters, and other construction workers conduct a rite for the gods of earth and houses, write the Chinese characters for “dragon” and “turtle,” the date, and a short supplication on the beam, and then raise it. A party ensues.

6. Completion and moving in: Following the sangnyangsik, the roof, walls, and inner building work are completed and the owner eventually moves in.

MATERIALS

Wood

Pine was considered the best wood for building. Other trees were often collectively referred to as jammok (miscellaneous wood). Red pine, regarded as the best of all the pine varieties, was the only wood used in palace construction; Buddhist temples and homes of the elite sometimes also made use of other types of wood, such zelkova, oak, poplar, nut pine, and fir. As with many edible plants in Korea, the use of trees and their timber varied according to their place of origin. Red pines from the deep valleys of Gangwon-do Province with tall, straight trunks relatively free from knots, were considered the very best for construction. Outstanding trees are still harvested from this area for the reconstruction of major landmarks such as palace buildings and Seoul’s Sungnyemun Gate. During the Joseon period, several forests were designated off-limits for civilians in order to protect the supply of timber for royal coffin making, the construction of palaces and other important buildings, naval ships, and other purposes. Paulownia wood, which grows predominantly in the southern regions of the Korean Peninsula, was valued for its resistance to rotting and splitting even when wet.

GEUMSAN: FORBIDDEN FORESTS

With the establishment of the Joseon Dynasty in the late 14th century, the royal court introduced a policy ensuring that firewood collection areas and other mountains, forests, streams, and marshes be accessible to the general public. Certain forests, however, were designated geumsan (literally “forbidden mountains”; the terms for mountain and forest were used somewhat interchangeably in traditional Korea). These included the mountains around Seoul, the deforestation of which would increase the new capital's susceptibility to natural disasters and interfere with pungsu principles. Forests outside the capital were also declared geumsan in order to protect valuable timber resources needed by the new state for the construction of palaces and the building of various ships and boats.

Geumsan fell into one of three categories: gwanbang, protected in the interests of national defense; yeonhae, coastal geumsan designated in the interests of construction, shipbuilding, and royal coffin making; and taebong, where enclosures were built for storing the placentas of royal family members. Historical records offer only partial information about geumsan, but several carved stone notices on mountains designated as such have been discovered, primarily in mountainous eastern Gangwon-do Province.

Stone

Wooden columns rested upon wider foundation stones known as juchutdol. These were usually made of granite and categorized in terms of value and suitability according to provenance. Stone from places such as Pocheon, Gapyeong, Hwangdeung, and Geochang was well-regarded, with Ganghwa aeseok (said to be named for the way its color resembled mugwort) among the most popular of all for its color and grain.

Earth and Plaster

Walls were applied in several layers, starting with a mixture of clay, water, and straw (the latter to prevent structural integrity) and followed by one or more outer layers mixed from various clays, sand, and lime or loam. Lime, produced by burning limestone, was an important building material due to its strong adhesive properties.

Tiles

Tiled roofs are often the most visible part of Korean traditional buildings, to the extent that the word hanok actually means “Korean roof.” After apparently arriving in Korea in around 200–100 BC, roof tiles reached a peak of ornate excellence during Unified Silla. They are made by baking sheets of clay wrapped around round molds at around 800–1000°C. Kilns were wood-fueled, round, elongated tunnels, half-buried in the ground. On traditional tiled roofs, concave “female” and round “male” tiles are arranged in alternate, interlocking furrows and ridges running down from the roofline to the eaves. Other tiles are used to cap the ends of roof ridges and tile rows.

Thatch

It must be remembered that the majority of Koreans in premodern times could not afford tiled roofs and instead used rice straw for thatching. Several bundles of straw were spread across the roof, and then held down by a grid-like net of rice straw rope that was tied or weighed down on top of the thatch. Such roofs were vulnerable to damage from wind, rain and fire—some historical accounts claim that they were replaced on an annual basis, making their long-term costs similar to that of the longer-lasting tile roofs. One advantage of straw thatch was that it was far lighter than tiles, allowing the use of thinner timber in supporting structures. Millet straw, reeds, and other grasses and grain stems were sometimes used.

Decorated “male” and “female” end tiles on the roof of Gakhwangjeon at Hwaeomsa Temple

CONTINUITY

After being marginalized and in many cases actively destroyed during Korea’s rapid period of industrialization, traditional building began enjoying a slow return to popularity from the 1990s onwards. Many Koreans hold the view that living in a structure made from natural materials such as wood and hwangto, Korea’s trademark red clay, brings health benefits. Rediscovered appreciation for traditional culture and aesthetics has also brought some limited benefits to traditional builders, but negative perceptions of traditional houses as cold and inconvenient places to live remain prevalent.

Other obstacles to furthering the building of hanok are the lack of suitable timber available in Korea, necessitating imports from countries and regions such as New Zealand, Southeast Asia, and North America, as well as the overall high cost of construction.

Nonetheless, as mentioned above, hanok construction has been growing, albeit from a very small base. Wood-based construction showed some dramatic year-on-year increases in the 2000s, although this was not accounted for by hanok alone. Increasing demand for such buildings has been accompanied by a need for more builders, leading to a greater number of institutions offering education and training in traditional building techniques.

Perhaps most interesting of all is the question of how the essential elements of hanok can be retained and adapted to create well-insulated, modern, reasonably priced, and systematically evolved dwellings that are unmistakably Korean yet indisputably contemporary, thereby unlocking much of Korean traditional architecture from the past.

ARCHITECTS

The professional title “architect” did not exist in Korea until the “modern” era, which is generally considered to have begun between the late 19th century and the end of Japan’s forced occupation of Korea (1945). Before this time, as in medieval Europe, the roles of architect and master craftsman were more or less inseparable. The basic design of premodern buildings, whether palaces, temples, schools, or private homes, were remarkably similar in terms of their basic elements, to the extent that the often considerable knowledge of materials, measurements, angles, carpentry, and stonemasonry possessed by craftsmen was sufficient enough for them to build sophisticated, structurally sound structures without additional input from engineers.

Some historians argue that Neo-Confucian scholars in the Joseon era (1392–1910) effectively played the role of architect in designing many of the most outstanding historical buildings that remain with us today. Examples include Dosan Seodang, designed by Toegye Yi Hwang; Dasan Chodang and Suwon Hwaseong, planned by 18th century silhak scholar Dasan Jeong Yak-yong; and Namgan Jeongsa, the work of Uam Song Si-yeol. In the case of many of the buildings in Yi Hwang’s hometown, Andong, records indicate that Yi drew plans and supervised construction himself.

In terms of construction, the fact that Korean buildings were predominantly comprised of wooden structures meant that carpenters played the most important role. Carpenter-monks—some with obviously extraordinary levels of skill—are mentioned in historical accounts of the construction of major temple buildings. Still today, it is master carpenters that assume the highest position in projects to reconstruct or restore historical buildings and structures. Carpenters were responsible for identifying, securing, and felling suitable trees, and drying, cutting, and assembling the wood. The literacy rate in premodern Korean society was low, so there are hardly any surviving accounts of their work written directly by craftsmen such as carpenters and stonemasons, who were not part of the literate class. Skills were passed on from master to apprentice verbally or by visual example, as testified by the few carpenter-builders alive today who learned by this method.

Joseon-era scholar Song Si-yeol