Gastrointestinal Disease

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Acute Gastroenteritis and Diarrhea

AUTOIMMUNE (CHRONIC) HEPATITIS

Esophageal Atresia

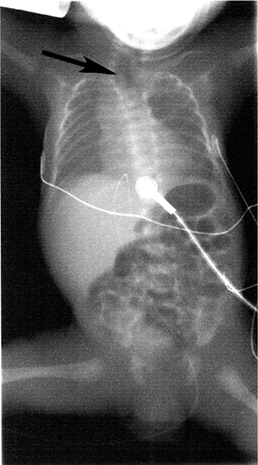

A full-term infant was noted to have copious oral secretions requiring frequent suctioning

to prevent choking. Attempts to place a nasogastric tube were unsuccessful, with the

tube curling in the esophagus. X-ray is shown in the figure. What is the likely diagnosis

and management of this condition?

A full-term infant was noted to have copious oral secretions requiring frequent suctioning

to prevent choking. Attempts to place a nasogastric tube were unsuccessful, with the

tube curling in the esophagus. X-ray is shown in the figure. What is the likely diagnosis

and management of this condition?

The nasogastric tube with the tip in the proximal esophagus and failure to advance further signifies an esophageal atresia. The most common type is where the proximal esophagus ends in a blind pouch (as in this case) and there is a distal tracheoesophageal fistula. Also evident are ribs and vertebral anomalies in this case. This could be part of VATER (vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, tracheoesophageal anomalies, renal anomalies) syndrome. Infant was noted to have a single right kidney on renal ultrasound. Management includes surgical repair of the tracheoesophageal fistula.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Esophageal atresia can be associated with the VACTERL sequence:

Vertebral

Anorectal

Cardiac

Tracheal

Esophageal

Renal

Limb anomalies

DEFINITION

The esophagus ends blindly ~10–12 cm from the nares.

The esophagus ends blindly ~10–12 cm from the nares.

Occurs in 1/3000–1/4500 live births.

Occurs in 1/3000–1/4500 live births.

In 85% of cases the distal esophagus communicates with the posterior trachea (distal

tracheoesophageal fistula [TEF]).

In 85% of cases the distal esophagus communicates with the posterior trachea (distal

tracheoesophageal fistula [TEF]).

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Suspect esophageal atresia in a neonate with drooling and excessive oral secretions.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

History of maternal polyhydramnios.

History of maternal polyhydramnios.

Newborn with ↑ oral secretions.

Newborn with ↑ oral secretions.

Choking, cyanosis, coughing during feeding (more commonly aspiration of pharyngeal

secretions).

Choking, cyanosis, coughing during feeding (more commonly aspiration of pharyngeal

secretions).

Esophageal atresia with fistula.

Esophageal atresia with fistula.

Aspiration of gastric contents via distal fistula—life threatening (chemical pneumonitis).

Aspiration of gastric contents via distal fistula—life threatening (chemical pneumonitis).

Tympanitic distended abdomen.

Tympanitic distended abdomen.

Esophageal atresia without fistula.

Esophageal atresia without fistula.

Recurrent coughing with aspiration pneumonia (delayed diagnosis).

Recurrent coughing with aspiration pneumonia (delayed diagnosis).

Aspiration of pharyngeal secretions common.

Aspiration of pharyngeal secretions common.

Airless abdomen on abdominal x-ray.

Airless abdomen on abdominal x-ray.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Inability to pass a rigid nasogastric tube from the mouth to the stomach is diagnostic of esophageal atresia.

DIAGNOSIS

Usually made at delivery.

Usually made at delivery.

Unable to pass nasogastric tube (NGT) into stomach (see coiled NGT on chest x-ray).

Unable to pass nasogastric tube (NGT) into stomach (see coiled NGT on chest x-ray).

May also use contrast radiology, video esophagram, or bronchoscopy.

May also use contrast radiology, video esophagram, or bronchoscopy.

Chest x-ray (CXR) demonstrates air in upper esophagus (see Figure 11-1).

Chest x-ray (CXR) demonstrates air in upper esophagus (see Figure 11-1).

FIGURE 11-1. Esophageal atresia. Radiograph demonstrating air in the upper esophagus (arrow) and GI tract, consistent with esophageal atresia.

TREATMENT

Surgical repair (may be done in stages).

Esophageal Foreign Body

Most commonly due to swallowing of radiopaque objects: Coins, pins, pills, screws,

and batteries.

Most commonly due to swallowing of radiopaque objects: Coins, pins, pills, screws,

and batteries.

Preexisting abnormalities (i.e., tracheoesophageal repair) result in ↑ risk of

having foreign body impaction at site of abnormality.

Preexisting abnormalities (i.e., tracheoesophageal repair) result in ↑ risk of

having foreign body impaction at site of abnormality.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

The most common site of esophageal impaction is at the thoracic inlet.

Site of impaction:

Site of impaction:

70%: Thoracic inlet (between clavicles on CXR).

70%: Thoracic inlet (between clavicles on CXR).

15%: Midesophagus.

15%: Midesophagus.

15%: Lower esophageal sphincter (LES).

15%: Lower esophageal sphincter (LES).

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Gagging/choking.

Gagging/choking.

Difficulty with secretions.

Difficulty with secretions.

Dysphagia/food refusal.

Dysphagia/food refusal.

Throat pain or chest pain.

Throat pain or chest pain.

Emesis/hematemesis.

Emesis/hematemesis.

DIAGNOSIS

History, sometime witnessed event.

History, sometime witnessed event.

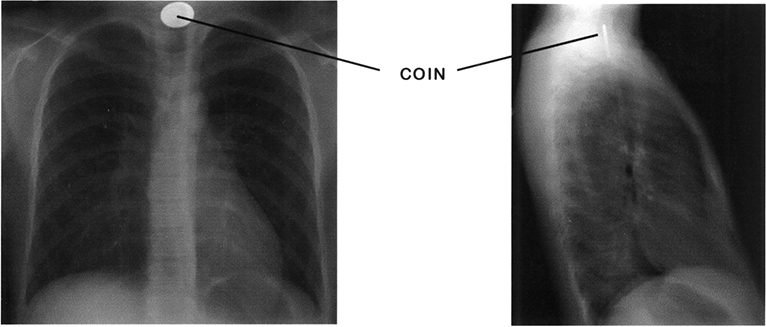

X-ray (AP/lateral CXR; see Figure 11-2).

X-ray (AP/lateral CXR; see Figure 11-2).

FIGURE 11-2. Esophageal foreign body. A coin in the esophagus will be seen flat or en face on an AP radiograph, and on its edge on a lateral view. (Used with permission from Dr. Julia Rosekrans.)

TREATMENT

Objects found within the esophagus are generally considered impacted.

Objects found within the esophagus are generally considered impacted.

Generally require endoscopic treatment if symptomatic or fail to pass to stomach

(below diaphragm on x-ray) within a few hours.

Generally require endoscopic treatment if symptomatic or fail to pass to stomach

(below diaphragm on x-ray) within a few hours.

Impacted objects, pointed objects, and batteries must be removed immediately.

Impacted objects, pointed objects, and batteries must be removed immediately.

Important to assess time of ingestion; >24 hours can → erosion or necrosis of esophageal

wall.

Important to assess time of ingestion; >24 hours can → erosion or necrosis of esophageal

wall.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Button batteries may rapidly cause local necrosis.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

An 8-month-old preterm infant has been hospitalized for 4 months in the neonatal

care unit. In the past 2 weeks, the nurses have noted that he is regurgitating several

times an hour. He makes chewing movements preceding these episodes of regurgitation.

Think: Rumination.

An 8-month-old preterm infant has been hospitalized for 4 months in the neonatal

care unit. In the past 2 weeks, the nurses have noted that he is regurgitating several

times an hour. He makes chewing movements preceding these episodes of regurgitation.

Think: Rumination.

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is common in preterm infants. Transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter is the most common mechanism implicated. Signs and symptoms include apnea, chronic lung disease, poor weight gain, and behavioral symptoms. Frequent regurgitation and feeding difficulties may occur.

DEFINITION

Passive reflux of gastric contents due to incompetent lower esophageal sphincter

(LES).

Passive reflux of gastric contents due to incompetent lower esophageal sphincter

(LES).

Approximately 1 in 300 children suffer from significant reflux and complication.

Approximately 1 in 300 children suffer from significant reflux and complication.

Functional gastroesophageal reflux is most common.

Functional gastroesophageal reflux is most common.

RISK FACTORS

Prematurity.

Prematurity.

Neurologic disorders.

Neurologic disorders.

Incompetence of LES due to prematurity, asthma.

Incompetence of LES due to prematurity, asthma.

Medications (theophylline, calcium channel blockers or β-blockers).

Medications (theophylline, calcium channel blockers or β-blockers).

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Excessive spitting up in the first week of life (in 85% of affected).

Excessive spitting up in the first week of life (in 85% of affected).

Symptomatic by 6 weeks (10%).

Symptomatic by 6 weeks (10%).

Symptoms resolve without treatment by age 2 (60%).

Symptoms resolve without treatment by age 2 (60%).

Forceful vomiting (occasional).

Forceful vomiting (occasional).

Aspiration pneumonia (30%).

Aspiration pneumonia (30%).

Chronic cough, wheezing, and recurrent pneumonia (later childhood).

Chronic cough, wheezing, and recurrent pneumonia (later childhood).

Rarely may cause laryngospasm, apnea, and bradycardia.

Rarely may cause laryngospasm, apnea, and bradycardia.

Regurgitation.

Regurgitation.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

GERD is the etiology for Sandifer syndrome (reflux, back arching, stiffness, and torticollis). Sandifer syndrome is most often confused with a neurologic or apparent life-threatening event.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical assessment in mild cases.

Clinical assessment in mild cases.

Esophageal pH probe studies and barium esophagography in severe cases.

Esophageal pH probe studies and barium esophagography in severe cases.

Esophagoscopy with biopsy for diagnosis of esophagitis.

Esophagoscopy with biopsy for diagnosis of esophagitis.

TREATMENT

Positioning following feeds—keep infant upright up to an hour after feeds.

Positioning following feeds—keep infant upright up to an hour after feeds.

In older children, mealtime more than 2 hours before sleep and sleeping with head

elevated.

In older children, mealtime more than 2 hours before sleep and sleeping with head

elevated.

Thickening formula with rice cereal.

Thickening formula with rice cereal.

Medications:

Medications:

Antacids, histamine-2 (H2) blockers (ranitidine), and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs; omeprazole).

Antacids, histamine-2 (H2) blockers (ranitidine), and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs; omeprazole).

Motility agents such as metoclopramide and erythromycin (stimulate gastric emptying).

Motility agents such as metoclopramide and erythromycin (stimulate gastric emptying).

Surgery—Nissen fundoplication.

Surgery—Nissen fundoplication.

Peptic Ulcer

DEFINITION

Includes primary and secondary (related to stress).

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Primary—pain, vomiting, and acute and chronic gastrointestinal (GI) blood loss.

Primary—pain, vomiting, and acute and chronic gastrointestinal (GI) blood loss.

First month of life: GI hemorrhage and perforation.

First month of life: GI hemorrhage and perforation.

Neonatal—2 months: Recurrent vomiting, slow growth, and GI hemorrhage.

Neonatal—2 months: Recurrent vomiting, slow growth, and GI hemorrhage.

Preschool: Periumbilical and postprandial pain (with vomiting and hemorrhage).

Preschool: Periumbilical and postprandial pain (with vomiting and hemorrhage).

>6 years: Epigastric abdominal pain, acute/chronic GI blood loss with anemia.

>6 years: Epigastric abdominal pain, acute/chronic GI blood loss with anemia.

Secondary:

Secondary:

Stress ulcers secondary to sepsis, respiratory or cardiac insufficiency, trauma,

or dehydration in infants.

Stress ulcers secondary to sepsis, respiratory or cardiac insufficiency, trauma,

or dehydration in infants.

Related to trauma or other life-threatening events (older children).

Related to trauma or other life-threatening events (older children).

Stress ulcers and erosions associated with burns (Curling ulcers).

Stress ulcers and erosions associated with burns (Curling ulcers).

Ulcers following head trauma or surgery usually Cushing ulcers.

Ulcers following head trauma or surgery usually Cushing ulcers.

Drug related—nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or steroids.

Drug related—nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or steroids.

Infectious––Helicobacter pylori.

Infectious––Helicobacter pylori.

DIAGNOSIS

Upper GI endoscopy.

Upper GI endoscopy.

Barium meal not sensitive.

Barium meal not sensitive.

Plain x-rays may diagnose perforation of acute ulcers.

Plain x-rays may diagnose perforation of acute ulcers.

Angiography can demonstrate bleeding site.

Angiography can demonstrate bleeding site.

H. pylori testing (hydrogen breath test, stool antigen).

H. pylori testing (hydrogen breath test, stool antigen).

TREATMENT

Antibiotics for eradication of H. pylori: Triple therapy—PPI + 2 antibiotics (amoxicillin, clarithromycin, PPI).

Antibiotics for eradication of H. pylori: Triple therapy—PPI + 2 antibiotics (amoxicillin, clarithromycin, PPI).

Antacids, sucralfate, and misoprostol.

Antacids, sucralfate, and misoprostol.

H2 blockers and PPIs.

H2 blockers and PPIs.

Give prophylaxis for peptic ulcer when child is NPO or is receiving steroids.

Give prophylaxis for peptic ulcer when child is NPO or is receiving steroids.

Endoscopic cautery.

Endoscopic cautery.

Surgery (vagotomy, pyloroplasty, or antrectomy) for extreme cases.

Surgery (vagotomy, pyloroplasty, or antrectomy) for extreme cases.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Antimicrobials: 14 days

PPIs: 1 month

Colic

DEFINITION

Rule of 3’s: Crying >3 hours/day, >3 days/week for >3 weeks between the ages of

3 weeks and 3 months.

Rule of 3’s: Crying >3 hours/day, >3 days/week for >3 weeks between the ages of

3 weeks and 3 months.

Frequent complex paroxysmal abdominal pain, severe crying.

Frequent complex paroxysmal abdominal pain, severe crying.

Usually in infants <3 months old.

Usually in infants <3 months old.

Etiology unknown. Can be related to under- or overfeeding, milk protein allergy,

parental stress, and smoking.

Etiology unknown. Can be related to under- or overfeeding, milk protein allergy,

parental stress, and smoking.

Colic is a diagnosis of exclusion. First look for other causes (hair in eye, corneal

abrasion, strangulated hernia, otitis media, sepsis, etc.).

Colic is a diagnosis of exclusion. First look for other causes (hair in eye, corneal

abrasion, strangulated hernia, otitis media, sepsis, etc.).

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Sudden-onset loud crying (paroxysms may persist for several hours).

Sudden-onset loud crying (paroxysms may persist for several hours).

Facial flushing.

Facial flushing.

Circumoral pallor.

Circumoral pallor.

Distended, tense abdomen.

Distended, tense abdomen.

Legs drawn up on abdomen.

Legs drawn up on abdomen.

Feet often cold.

Feet often cold.

Temporary relief apparent with passage of feces or flatus.

Temporary relief apparent with passage of feces or flatus.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

A head-to-toe examination is essential.

Physical examination MUST be normal.

TREATMENT

No single treatment provides satisfactory relief.

No single treatment provides satisfactory relief.

Careful exam is important to rule out other causes.

Careful exam is important to rule out other causes.

Improve feeding techniques (burping).

Improve feeding techniques (burping).

Avoid over- or underfeeding.

Avoid over- or underfeeding.

Resolves spontaneously with time.

Resolves spontaneously with time.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Parents and caretakers of children with colic are often very stressed out, putting the child at risk for child abuse.

Pyloric Stenosis

A 4-week-old male infant has a 5-day history of vomiting after feedings. Physical

exam shows a hungry infant with prominent peristaltic waves in the epigastrium. Laboratory

evaluation revealed the following: Na 129, Cl 92, HCO3 28, K 3.1, BUN 24. Think: Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.

A 4-week-old male infant has a 5-day history of vomiting after feedings. Physical

exam shows a hungry infant with prominent peristaltic waves in the epigastrium. Laboratory

evaluation revealed the following: Na 129, Cl 92, HCO3 28, K 3.1, BUN 24. Think: Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.

Pyloric stenosis is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in infants. It is more common in males (M:F 4:1). It usually presents during the third to fifth week of life. Initial symptom is nonbilious vomiting. Classic sign of olive mass is not as common since increasing awareness has resulted in ultrasound imaging and early diagnosis. Criteria for diagnosis include pyloric muscle thickness >4 mm and length of pyloric canal >14 mm. Hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis is the classic electrolyte abnormality.

DEFINITION

Most common etiology is idiopathic.

Most common etiology is idiopathic.

Not usually present at birth.

Not usually present at birth.

Associated with exogenous administration of erythromycin, eosinophilic gastroenteritis,

epidermolysis bullosa, trisomy 18, and Turner syndrome.

Associated with exogenous administration of erythromycin, eosinophilic gastroenteritis,

epidermolysis bullosa, trisomy 18, and Turner syndrome.

First-born male.

First-born male.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Typical: Projectile vomiting, palpable mass, and peristalsis—not always present.

Typical: Projectile vomiting, palpable mass, and peristalsis—not always present.

Nonbilious vomiting (projectile or not).

Nonbilious vomiting (projectile or not).

Usually progressive, after feeding.

Usually progressive, after feeding.

Usually after 3 weeks of age, may be as late as 5 months.

Usually after 3 weeks of age, may be as late as 5 months.

Hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis (rare these days due to earlier

diagnosis).

Hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis (rare these days due to earlier

diagnosis).

Palpable pyloric olive-shaped mass in midepigastrium (difficult to find).

Palpable pyloric olive-shaped mass in midepigastrium (difficult to find).

Visible peristalsis: Left to right.

Visible peristalsis: Left to right.

DIAGNOSIS

Ultrasound (90% sensitivity).

Ultrasound (90% sensitivity).

Elongated pyloric channel (>14 mm).

Elongated pyloric channel (>14 mm).

Thickened pyloric wall (>4 mm).

Thickened pyloric wall (>4 mm).

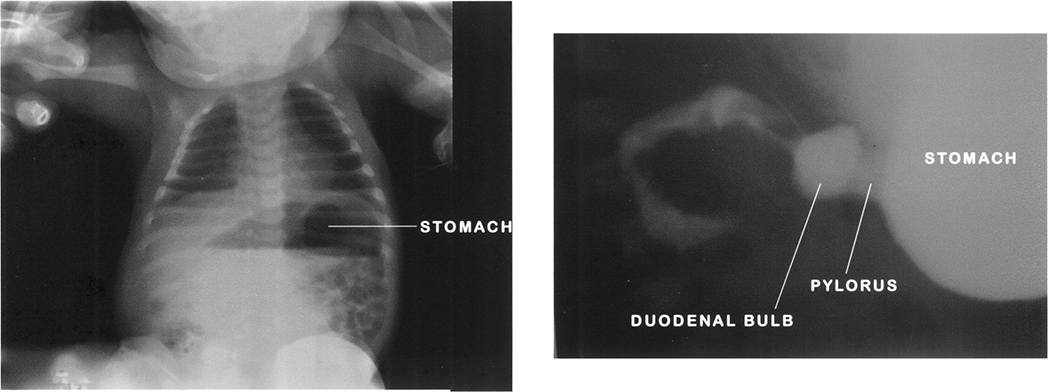

Radiographic contrast series (Figure 11-3).

Radiographic contrast series (Figure 11-3).

FIGURE 11-3. Abdominal x-ray on the left demonstrates a dilated air-filled stomach with normal caliber bowel, consistent with gastric outlet obstruction. Barium meal figure on the right confirms diagnosis of pyloric stenosis. The dilated duodenal bulb is the “olive” felt on physical exam. Note how there is a paucity of contrast traveling through the duodenum. (Used with permission from Drs. Julia Rosekrans and James E. Colletti.)

String sign: From elongated pyloric channel.

String sign: From elongated pyloric channel.

Shoulder sign: Bulge of pyloric muscle into the antrum.

Shoulder sign: Bulge of pyloric muscle into the antrum.

Double tract sign: Parallel streaks of barium in the narrow channel.

Double tract sign: Parallel streaks of barium in the narrow channel.

TREATMENT

Surgery: Pyloromyotomy is curative.

Surgery: Pyloromyotomy is curative.

Must correct existing dehydration and acid-base abnormalities prior to surgery.

Must correct existing dehydration and acid-base abnormalities prior to surgery.

Duodenal Atresia

DEFINITION

Failure to recanalize lumen after solid phase of intestinal development.

Failure to recanalize lumen after solid phase of intestinal development.

Several forms.

Several forms.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Bilious vomiting without abdominal distention (first day of life). Onset of vomiting

within hours of birth.

Bilious vomiting without abdominal distention (first day of life). Onset of vomiting

within hours of birth.

Can be nonbilious if the defect is proximal to the ampulla of Vater.

Can be nonbilious if the defect is proximal to the ampulla of Vater.

Scaphoid abdomen.

Scaphoid abdomen.

Placement of orogastric tube typically yields a significant amount of bile-stained

fluid.

Placement of orogastric tube typically yields a significant amount of bile-stained

fluid.

History of polyhydramnios in 50% of pregnancies.

History of polyhydramnios in 50% of pregnancies.

Down syndrome seen in 20–30% of cases.

Down syndrome seen in 20–30% of cases.

Associated anomalies include malrotation, esophageal atresia, and congenital heart

disease.

Associated anomalies include malrotation, esophageal atresia, and congenital heart

disease.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical.

Clinical.

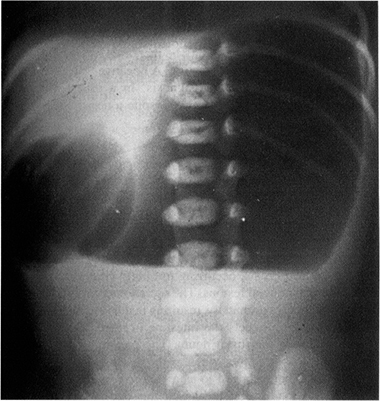

X-ray findings: Double-bubble sign (air bubbles in the stomach and duodenum) proximal

to the site of atresia (Figure 11-4).

X-ray findings: Double-bubble sign (air bubbles in the stomach and duodenum) proximal

to the site of atresia (Figure 11-4).

FIGURE 11-4. Duodenal atresia. Gas-filled and dilated stomach shows the classic “double-bubble” appearance of duodenal atresia. Note no distal gas is present. (Reproduced, with permission, from Rudolph CD, et al (eds). Rudolph’s Pediatrics, 21st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002: 1403.)

TREATMENT

Initially, nasogastric and orogastric decompression with intravenous (IV) fluid

replacement.

Initially, nasogastric and orogastric decompression with intravenous (IV) fluid

replacement.

Treat life-threatening anomalies.

Treat life-threatening anomalies.

Surgery.

Surgery.

Duodenoduodenostomy.

Duodenoduodenostomy.

Volvulus

DEFINITION

Gastric and intestinal:

Gastric and intestinal:

Gastric: Sudden onset of severe epigastric pain; intractable retching with emesis.

Gastric: Sudden onset of severe epigastric pain; intractable retching with emesis.

Intestinal: Associated with malrotation (Figure 11-5).

Intestinal: Associated with malrotation (Figure 11-5).

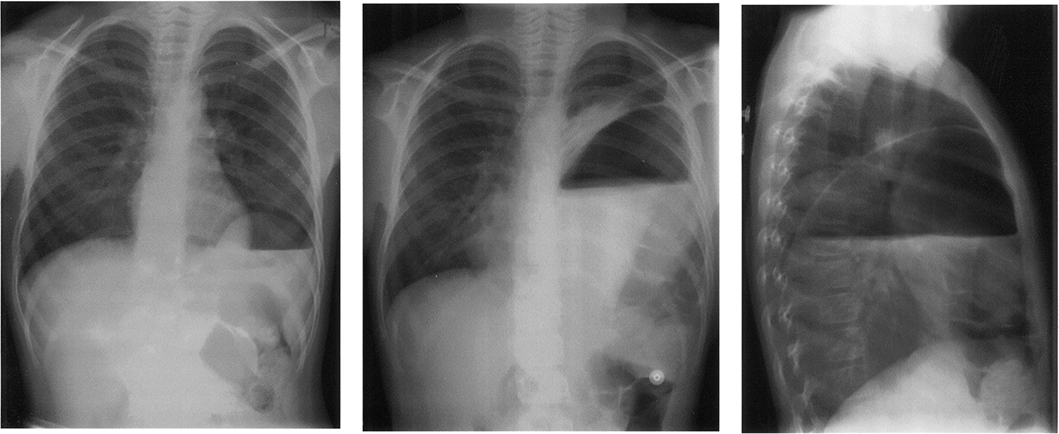

FIGURE 11-5. Volvulus. First AP view done 6 weeks prior to the second AP and corresponding lateral view. Note the markedly dilated stomach above the normal level of the left hemidiaphragm in the thoracic cavity. Also present is a large left-sided diaphragmatic hernia. (Used with permission from Dr. Julia Rosekrans.)

Volvulus occurs as a consequence of intestinal malrotation—obstruction is complete,

and compromise to the blood supply of the midgut has started.

Volvulus occurs as a consequence of intestinal malrotation—obstruction is complete,

and compromise to the blood supply of the midgut has started.

RISK FACTORS

Embryological abnormalities: Arrest of development at any stage during embryological

development of GI tract can → changes in anatomical position of organs and narrowing

of mesenteric base, resulting in ↑ risk for volvulus.

Embryological abnormalities: Arrest of development at any stage during embryological

development of GI tract can → changes in anatomical position of organs and narrowing

of mesenteric base, resulting in ↑ risk for volvulus.

Male-to-female presentation: 2:1.

Male-to-female presentation: 2:1.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Vomiting in infancy.

Vomiting in infancy.

Emesis (commonly bilious).

Emesis (commonly bilious).

Abdominal pain → acute abdomen.

Abdominal pain → acute abdomen.

Early satiety.

Early satiety.

Blood-stained stools.

Blood-stained stools.

Distention.

Distention.

A neonate with bilious vomiting must be considered at risk for having a midgut

volvulus.

A neonate with bilious vomiting must be considered at risk for having a midgut

volvulus.

DIAGNOSIS

Plain abdominal films: Characteristic bird-beak appearance.

Plain abdominal films: Characteristic bird-beak appearance.

May also see air-fluid level without beak.

May also see air-fluid level without beak.

TREATMENT

Treatment is surgical correction.

Treatment is surgical correction.

Gastric: Emergent surgery.

Gastric: Emergent surgery.

Intestinal: Surgery or endoscopy.

Intestinal: Surgery or endoscopy.

COMPLICATIONS

Perforation.

Perforation.

Peritonitis.

Peritonitis.

Intussusception

A 9-month-old female infant was brought to the ED due to vomiting and crying. She

had a “cold” 3 days ago. On arrival she was sleepy but arousable. When she woke up,

she cried and vomited. Physical examination revealed distended abdomen with an ill-defined

mass in the right upper abdomen. What is the cause of her symptoms? Intussusception.

A 9-month-old female infant was brought to the ED due to vomiting and crying. She

had a “cold” 3 days ago. On arrival she was sleepy but arousable. When she woke up,

she cried and vomited. Physical examination revealed distended abdomen with an ill-defined

mass in the right upper abdomen. What is the cause of her symptoms? Intussusception.

How she should be treated? A contrast enema should be performed to reduce the intussusception. It is both diagnostic and therapeutic. It should be performed in consultation with a pediatric surgeon caring for the child and a pediatric radiologist interpreting the study. It is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction between 5 months and 6 years of age. Most children with intussusception are under 1 year of age. The classic triad of intermittent, colicky abdominal pain; vomiting; and bloody, mucous stools occur in only 20–40%.

DEFINITION

Invagination of one portion of the bowel into itself. The proximal portion is usually drawn into the distal portion by peristalsis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Incidence: 1–4 in 1000 live births.

Incidence: 1–4 in 1000 live births.

Male-to-female ratio: 2:1 to 4:1.

Male-to-female ratio: 2:1 to 4:1.

Peak incidence: 5–12 months.

Peak incidence: 5–12 months.

Age range: 2 months to 5 years.

Age range: 2 months to 5 years.

Most common cause of acute intestinal obstruction under 2 years of age.

Most common cause of acute intestinal obstruction under 2 years of age.

Most common site is ileocolic (90%).

Most common site is ileocolic (90%).

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Intussusception is the most common cause of bowel obstruction in children ages 2 months to 5 years.

ETIOLOGY

Most common etiology is idiopathic.

Most common etiology is idiopathic.

Other causes:

Other causes:

Viral (enterovirus in summer, rotavirus in winter).

Viral (enterovirus in summer, rotavirus in winter).

A “lead point” (or focus) is thought to be present in older children 2–10% of the

time. These lead points can be caused by Meckel’s diverticulum, polyp, lymphoma, Henoch-Schönlein

purpura, cystic fibrosis.

A “lead point” (or focus) is thought to be present in older children 2–10% of the

time. These lead points can be caused by Meckel’s diverticulum, polyp, lymphoma, Henoch-Schönlein

purpura, cystic fibrosis.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Intussusception

Classic triad is present in only 20% of cases.

Classic triad is present in only 20% of cases.

Absence of currant jelly stool does not exclude the diagnosis.

Absence of currant jelly stool does not exclude the diagnosis.

Neurologic signs may delay the diagnosis.

Neurologic signs may delay the diagnosis.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Classic triad:

Classic triad:

Intermittent colicky abdominal pain.

Intermittent colicky abdominal pain.

Bilious vomiting.

Bilious vomiting.

Currant jelly stool (late finding).

Currant jelly stool (late finding).

Neurologic signs:

Neurologic signs:

Lethargy

Lethargy

Shocklike state.

Shocklike state.

Seizure activity.

Seizure activity.

Apnea.

Apnea.

Right upper quadrant mass:

Right upper quadrant mass:

Sausage shaped.

Sausage shaped.

Ill defined.

Ill defined.

Dance’s sign: Absence of bowel in right lower quadrant.

Dance’s sign: Absence of bowel in right lower quadrant.

DIAGNOSIS

Abdominal x-ray:

Abdominal x-ray:

X-ray is neither specific nor sensitive. Can be completely normal.

X-ray is neither specific nor sensitive. Can be completely normal.

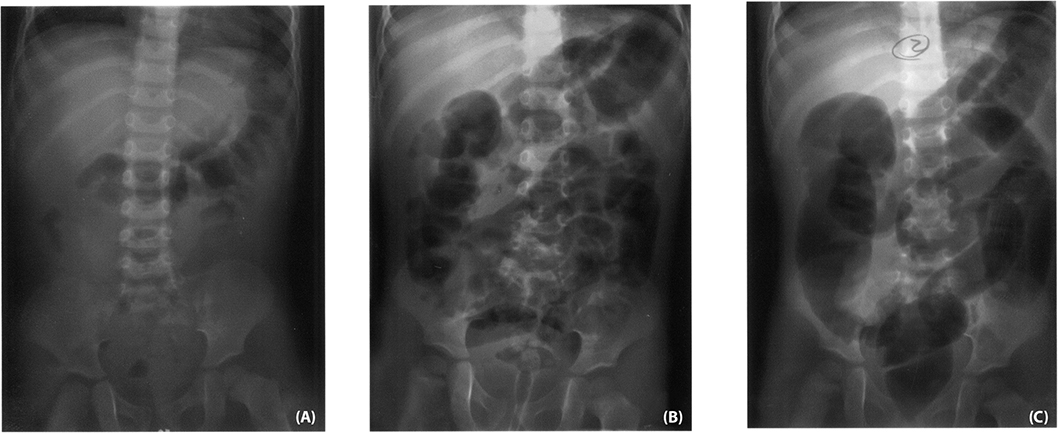

Paucity of bowel gas (Figure 11-6).

Paucity of bowel gas (Figure 11-6).

FIGURE 11-6. Intussusception. Note the paucity of bowel gas in film (A) Air enema partially reduces it in film (B) and then completely reduced it in film (C).

Loss of visualization of the tip of liver.

Loss of visualization of the tip of liver.

“Target sign”: Two concentric circles of fat density.

“Target sign”: Two concentric circles of fat density.

Ultrasound:

Ultrasound:

Test of choice.

Test of choice.

“Target” or “donut” sign: Single hypoechoic ring with hyperechoic center.

“Target” or “donut” sign: Single hypoechoic ring with hyperechoic center.

“Pseudokidney” sign: Superimposed hypoechoic (edematous walls of bowel) and hyperechoic

(areas of compressed mucosa) layers.

“Pseudokidney” sign: Superimposed hypoechoic (edematous walls of bowel) and hyperechoic

(areas of compressed mucosa) layers.

Barium enema:

Barium enema:

Not useful for ileoileal intussusceptions.

Not useful for ileoileal intussusceptions.

May note cervix-like mass.

May note cervix-like mass.

Coiled spring appearance on the evacuation film.

Coiled spring appearance on the evacuation film.

Contraindications: Peritonitis, perforation, profound shock/hemodynamic instability.

Contraindications: Peritonitis, perforation, profound shock/hemodynamic instability.

Air enema:

Air enema:

Air enema is preferred (safe, with a lower absorbed radiation).

Air enema is preferred (safe, with a lower absorbed radiation).

Often provides the same diagnostic and therapeutic benefit of a barium enema without

the barium.

Often provides the same diagnostic and therapeutic benefit of a barium enema without

the barium.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Contrast enema for intussusception can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. Rule of threes:

Barium column should not exceed a height of 3 feet.

Barium column should not exceed a height of 3 feet.

No more than 3 attempts.

No more than 3 attempts.

Only 3 minutes/attempt.

Only 3 minutes/attempt.

TREATMENT

Correct dehydration.

Correct dehydration.

NG tube for decompression.

NG tube for decompression.

Hydrostatic reduction.

Hydrostatic reduction.

Barium/air enema (see Figure 11-7).

Barium/air enema (see Figure 11-7).

FIGURE 11-7. Abdominal x-ray following barium enema in a 2-month-old boy, consistent with intussusception. Note paucity of gas in right upper quadrant and near obscuring of liver tip.

Surgical reduction:

Surgical reduction:

Failed reduction by enema.

Failed reduction by enema.

Clinical signs of perforation or peritonitis.

Clinical signs of perforation or peritonitis.

Recurrence:

Recurrence:

With radiologic reduction: 7–10%.

With radiologic reduction: 7–10%.

With surgical reduction: 2–5%.

With surgical reduction: 2–5%.

Meckel’s Diverticulum

DEFINITION

Persistence of the omphalomesenteric (vitelline) duct (should disappear by seventh week of gestation).

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Meckel’s Rules of 2

2% of population

2% of population

2 inches long

2 inches long

2 feet from the ileocecal valve

2 feet from the ileocecal valve

Patient is usually under 2 years of age

Patient is usually under 2 years of age

2% are symptomatic

2% are symptomatic

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Usually in first 2 years:

Usually in first 2 years:

Intermittent painless rectal bleeding (hematochezia—most common presenting sign).

Intermittent painless rectal bleeding (hematochezia—most common presenting sign).

Intestinal obstruction.

Intestinal obstruction.

Diverticulitis.

Diverticulitis.

Occurs on the antimesenteric border of the ileum, usually 40–60 cm proximal to

the ileocecal valve.

Occurs on the antimesenteric border of the ileum, usually 40–60 cm proximal to

the ileocecal valve.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Meckel’s diverticulum may mimic acute appendicitis and also act as lead point for intussusception.

DIAGNOSIS

Meckel’s scan (scintigraphy) has 85% sensitivity and 95% specificity. Uptake can

be enhanced with cimetidine, glucagons, or gastrin.

Meckel’s scan (scintigraphy) has 85% sensitivity and 95% specificity. Uptake can

be enhanced with cimetidine, glucagons, or gastrin.

Most common heterotopic mucosa is gastric.

Most common heterotopic mucosa is gastric.

TREATMENT

Surgical: Diverticular resection with transverse closure of the enterotomy.

Appendicitis

DEFINITION

Acute inflammation and infection of the vermiform appendix.

Acute inflammation and infection of the vermiform appendix.

Most common cause for emergent surgery in childhood.

Most common cause for emergent surgery in childhood.

Perforation rates are greatest in youngest children (can’t localize symptoms).

Perforation rates are greatest in youngest children (can’t localize symptoms).

Occurs secondary to obstruction of lumen of appendix.

Occurs secondary to obstruction of lumen of appendix.

Three phases:

Three phases:

1. Luminal obstruction, venous congestion progresses to mucosal is chemia, necrosis, and ulceration.

2. Bacterial invasion with inflammatory infiltrate through all layers.

3. Necrosis of wall results in perforation and contamination.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Classically: Pain, vomiting, and fever.

Classically: Pain, vomiting, and fever.

Initially, periumbilical pain; emesis infrequent.

Initially, periumbilical pain; emesis infrequent.

Anorexia.

Anorexia.

Low-grade fever.

Low-grade fever.

Diarrhea infrequent.

Diarrhea infrequent.

Pain radiates to right lower quadrant.

Pain radiates to right lower quadrant.

Perforation rate >65% after 48 hours.

Perforation rate >65% after 48 hours.

Rectal exam may reveal localized mass or tenderness.

Rectal exam may reveal localized mass or tenderness.

DIAGNOSIS

History and physical exam is key to rule out alternatives first.

History and physical exam is key to rule out alternatives first.

Pain usually occurs before vomiting, diarrhea, or anorexia.

Pain usually occurs before vomiting, diarrhea, or anorexia.

Atypical presentations are common—risk for misdiagnosis.

Atypical presentations are common—risk for misdiagnosis.

Most common misdiagnosis: Gastroenteritis.

Most common misdiagnosis: Gastroenteritis.

Labs helpful to rule other diagnosis but no laboratory test specific for appendicitis.

Labs helpful to rule other diagnosis but no laboratory test specific for appendicitis.

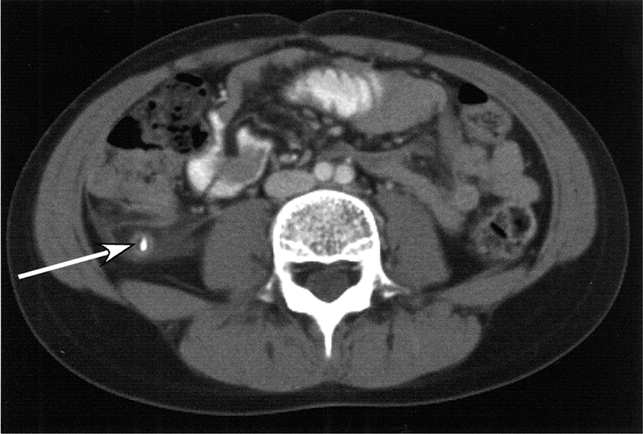

Computed tomographic (CT) scan (Figure 11-8) indicated for patients in whom diagnosis is equivocal—not a requirement for all

patients.

Computed tomographic (CT) scan (Figure 11-8) indicated for patients in whom diagnosis is equivocal—not a requirement for all

patients.

FIGURE 11-8. Abdominal CT of a 10-year-old girl demonstrating enlargement of the appendix, some periappendiceal fluid, and an appendicolith (arrow), consistent with acute appendicitis.

Higher rate of ruptured appendix on presentation in young children.

Higher rate of ruptured appendix on presentation in young children.

TREATMENT

Surgery as soon as diagnosis made.

Surgery as soon as diagnosis made.

Antibiotics are controversial in nonperforated appendicitis.

Antibiotics are controversial in nonperforated appendicitis.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics needed for cases of perforation (ampicillin, gentamicin,

clindamycin, or metronidazole × 7 days).

Broad-spectrum antibiotics needed for cases of perforation (ampicillin, gentamicin,

clindamycin, or metronidazole × 7 days).

Laparoscopic removal associated with shortened hospital stay (nonperforated appendicitis).

Laparoscopic removal associated with shortened hospital stay (nonperforated appendicitis).

Constipation

A 4-year-old girl has not had a bowel movement for a week, and this has been a recurring

problem. Various laxatives and enemas have been tried in the past. Prior to toilet

training, the girl had one bowel movement a day. Physical examination is normal except

for the presence of stool in the sigmoid colon and hard stool on rectal examination.

After removing the impaction, the next appropriate step in management would be to

administer mineral oil or other stool softener.

A 4-year-old girl has not had a bowel movement for a week, and this has been a recurring

problem. Various laxatives and enemas have been tried in the past. Prior to toilet

training, the girl had one bowel movement a day. Physical examination is normal except

for the presence of stool in the sigmoid colon and hard stool on rectal examination.

After removing the impaction, the next appropriate step in management would be to

administer mineral oil or other stool softener.

Constipation is a common problem in children. It is the most common cause of abdominal pain in children. Functional constipation is more common in children, and organic causes are common in neonates. The physical examination often reveals a large volume of stool palpated in the suprapubic region. The finding of rectal impaction may establish the diagnosis.

DEFINITION/SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Common cause of abdominal pain in children.

Common cause of abdominal pain in children.

Passage of bulky or hard stool at infrequent intervals.

Passage of bulky or hard stool at infrequent intervals.

During the neonatal period usually caused by Hirschsprung, intestinal pseudo-obstruction,

or hypothyroidism.

During the neonatal period usually caused by Hirschsprung, intestinal pseudo-obstruction,

or hypothyroidism.

Other causes include organic and inorganic (e.g., cow’s milk protein intolerance,

drugs).

Other causes include organic and inorganic (e.g., cow’s milk protein intolerance,

drugs).

May be metabolic (dehydration, hypothyroidism, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, psychiatric).

May be metabolic (dehydration, hypothyroidism, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, psychiatric).

TREATMENT

↑ oral fluid and fiber intake.

↑ oral fluid and fiber intake.

Stool softeners (e.g., mineral oil).

Stool softeners (e.g., mineral oil).

Glycerin suppositories.

Glycerin suppositories.

Cathartics such as senna or docusate.

Cathartics such as senna or docusate.

Nonabsorbable osmotic agents (polyethylene glycol) and milk of magnesia for short

periods only if necessary—can cause electrolyte imbalances.

Nonabsorbable osmotic agents (polyethylene glycol) and milk of magnesia for short

periods only if necessary—can cause electrolyte imbalances.

Hirschsprung’s Megacolon

A full-term male infant was noted to have progressive abdominal distention on the

second day of life, with no stool since birth. He was feeding well on demand whether

mother’s milk or infant formula. He was otherwise healthy, active, and had no signs

of infection. Abdominal x-ray is consistent with distended loops of bowel with no

evidence of free air. Contrast enema is notable for a narrowed segment of the colon

leading to a very distended loop.

A full-term male infant was noted to have progressive abdominal distention on the

second day of life, with no stool since birth. He was feeding well on demand whether

mother’s milk or infant formula. He was otherwise healthy, active, and had no signs

of infection. Abdominal x-ray is consistent with distended loops of bowel with no

evidence of free air. Contrast enema is notable for a narrowed segment of the colon

leading to a very distended loop.

The diagnosis is likely Hirschsprung disease. Hirschsprung disease results from absence of ganglion cells in the bowel wall and resultant narrowed segment of the bowel. The proximal normal bowel progressively dilates due to accumulated food. Definitive diagnosis is made by rectal biopsy, which demonstrates absent ganglion cells.

DEFINITION

Abnormal innervation of bowel (i.e., absence of ganglion cells in bowel).

Abnormal innervation of bowel (i.e., absence of ganglion cells in bowel).

↑ in familial incidence.

↑ in familial incidence.

Occurs in males more than females.

Occurs in males more than females.

Associated with Down syndrome.

Associated with Down syndrome.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Delayed passage of meconium at birth.

Delayed passage of meconium at birth.

↑ abdominal distention →↓ blood flow → deterioration of mucosal barrier → bacterial

proliferation → enterocolitis.

↑ abdominal distention →↓ blood flow → deterioration of mucosal barrier → bacterial

proliferation → enterocolitis.

Chronic constipation and abdominal distention (older children).

Chronic constipation and abdominal distention (older children).

DIAGNOSIS

Rectal manometry: Measures pressure of the anal sphincter.

Rectal manometry: Measures pressure of the anal sphincter.

Rectal suction biopsy: Must obtain submucosa to evaluate for ganglionic cells.

Rectal suction biopsy: Must obtain submucosa to evaluate for ganglionic cells.

TREATMENT

Surgery is definitive (usually staged procedures).

Imperforate Anus

DEFINITION

Absence of normal anal opening.

Absence of normal anal opening.

Rectum is blind; located 2 cm from perineal skin.

Rectum is blind; located 2 cm from perineal skin.

Sacrum and sphincter mechanism well developed.

Sacrum and sphincter mechanism well developed.

Prognosis good.

Prognosis good.

Can be associated with VACTERL anomalies.

Can be associated with VACTERL anomalies.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

First newborn examination in nursery.

First newborn examination in nursery.

Failure to pass meconium.

Failure to pass meconium.

Abdominal distention.

Abdominal distention.

DIAGNOSIS

Physical examination.

Physical examination.

Abdominal ultrasonography to examine the genitourinary tract.

Abdominal ultrasonography to examine the genitourinary tract.

Sacral radiography.

Sacral radiography.

Spinal ultrasound: Association with spinal cord abnormalities, particularly spinal

cord tethering.

Spinal ultrasound: Association with spinal cord abnormalities, particularly spinal

cord tethering.

TREATMENT

Surgery (colostomy in newborn period).

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Imperforate anus is frequently associated with Down syndrome and VACTERL.

Anal Fissure

A well-nourished 3-month-old infant is brought to the ED because of constipation,

blood-streaked stools, and excessive crying on defecation. Think: Anal fissure.

A well-nourished 3-month-old infant is brought to the ED because of constipation,

blood-streaked stools, and excessive crying on defecation. Think: Anal fissure.

Anal fissure is a painful linear tear or crack in the distal anal canal. Constipation may be exacerbated because of fear of pain with defecation. Diagnosis often can be made based on history and physical examination.

DEFINITION

Painful linear tears in the anal mucosa below the dentate line induced by constipation

or excessive diarrhea.

Painful linear tears in the anal mucosa below the dentate line induced by constipation

or excessive diarrhea.

Tear of squamous epithelium of anal canal between anocutaneous junction and dentate

line.

Tear of squamous epithelium of anal canal between anocutaneous junction and dentate

line.

Often history of constipation is present.

Often history of constipation is present.

Predilection for the posterior midline.

Predilection for the posterior midline.

Common age: 6–24 months.

Common age: 6–24 months.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Pain with defecation/crying during bowel movement.

Pain with defecation/crying during bowel movement.

↑ sphincter tone.

↑ sphincter tone.

Visible tear upon gentle lateral retraction of anal tissue.

Visible tear upon gentle lateral retraction of anal tissue.

DIAGNOSIS

Anal inspection.

TREATMENT

Sitz baths, fiber supplements, ↑ fluid intake.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

DEFINITION

Idiopathic chronic diseases include Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis (UC).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Common onset in adolescence and young adulthood.

Common onset in adolescence and young adulthood.

Bimodal pattern in patients 15–25 and 50–80 years of age.

Bimodal pattern in patients 15–25 and 50–80 years of age.

Genetics: ↑ concordance with monozygotic twins versus dizygotic (↑ for Crohn versus

UC).

Genetics: ↑ concordance with monozygotic twins versus dizygotic (↑ for Crohn versus

UC).

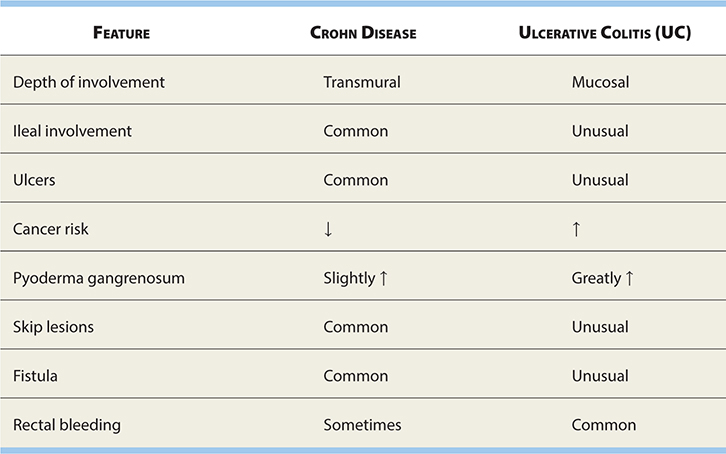

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS (TABLE 11-1)

TABLE 11-1. Crohn Disease versus Ulcerative Colitis

Crampy abdominal pain.

Crampy abdominal pain.

Extraintestinal manifestations greater in Crohn than UC.

Extraintestinal manifestations greater in Crohn than UC.

Crohn: Perianal fistula, sclerosing cholangitis, chronic active hepatitis, pyoderma

gangrenosum, ankylosing spondylitis, erythema nodosum.

Crohn: Perianal fistula, sclerosing cholangitis, chronic active hepatitis, pyoderma

gangrenosum, ankylosing spondylitis, erythema nodosum.

UC: Bloody diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss, pyoderma gangrenosum, sclerosing cholangitis,

marked by flare-ups.

UC: Bloody diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss, pyoderma gangrenosum, sclerosing cholangitis,

marked by flare-ups.

TREATMENT

Crohn disease: Corticosteroids, aminosalicylates, methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporine,

metronidazole (for perianal disease), sitz baths, anti–tumor necrosis factor-α, surgery

for complications.

Crohn disease: Corticosteroids, aminosalicylates, methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporine,

metronidazole (for perianal disease), sitz baths, anti–tumor necrosis factor-α, surgery

for complications.

UC: Aminosalicylates, oral corticosteroids, colectomy.

UC: Aminosalicylates, oral corticosteroids, colectomy.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

DEFINITION

Abdominal pain associated with intermittent diarrhea and constipation without organic basis; ~10% in adolescents.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Abdominal pain.

Abdominal pain.

Diarrhea alternating with constipation.

Diarrhea alternating with constipation.

DIAGNOSIS

Difficult to make, exclude other pathology.

Difficult to make, exclude other pathology.

Obtain CBC, ESR, stool occult blood.

Obtain CBC, ESR, stool occult blood.

TREATMENT

None specific.

None specific.

Supportive with reinforcement and reassurance.

Supportive with reinforcement and reassurance.

Address any underlying psychosocial stressors.

Address any underlying psychosocial stressors.

Acute Gastroenteritis and Diarrhea

DEFINITION

Diarrhea is the excessive loss of fluid and electrolytes in stool, usually secondary to disturbed

intestinal solute transport. Technically limited to lower GI tract.

Diarrhea is the excessive loss of fluid and electrolytes in stool, usually secondary to disturbed

intestinal solute transport. Technically limited to lower GI tract.

Gastroenteritis is an inflammation of the entire (upper and lower) GI tract, and thus involves both

vomiting and diarrhea.

Gastroenteritis is an inflammation of the entire (upper and lower) GI tract, and thus involves both

vomiting and diarrhea.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

↑ susceptibility seen in young age, immunodeficiency, malnutrition, travel, lack

of breast-feeding, and contaminated food or water.

↑ susceptibility seen in young age, immunodeficiency, malnutrition, travel, lack

of breast-feeding, and contaminated food or water.

Most common cause of diarrhea in children is viral: (1) rotavirus, (2) enteric

adenovirus, (3) Norwalk virus.

Most common cause of diarrhea in children is viral: (1) rotavirus, (2) enteric

adenovirus, (3) Norwalk virus.

Bacterial: (1) Campylobacter, (2) Salmonella and Shigella species and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli.

Bacterial: (1) Campylobacter, (2) Salmonella and Shigella species and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli.

Children in developing countries often also get infected by bacterial and parasitic

pathogens:

Children in developing countries often also get infected by bacterial and parasitic

pathogens:

Enterotoxigenic E. coli number one in developing countries.

Enterotoxigenic E. coli number one in developing countries.

Parasitic causes: (1) Giardia and (2) Cryptosporidium.

Parasitic causes: (1) Giardia and (2) Cryptosporidium.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Acute diarrhea is usually caused by infectious agents, whereas chronic persistent diarrhea may be secondary to infectious agents, infection of immunocompromised host, or residual symptoms due to intestinal damage.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Important to obtain information regarding frequency and volume.

Important to obtain information regarding frequency and volume.

General patient appearance important (well appearing versus ill appearing).

General patient appearance important (well appearing versus ill appearing).

Associated findings include cramps, emesis, malaise, and fever.

Associated findings include cramps, emesis, malaise, and fever.

May see systemic manifestations, GI tract involvement, or extraintestinal infections.

May see systemic manifestations, GI tract involvement, or extraintestinal infections.

Extraintestinal findings include vulvovaginitis, urinary tract infection (UTI),

and keratoconjunctivitis.

Extraintestinal findings include vulvovaginitis, urinary tract infection (UTI),

and keratoconjunctivitis.

Systemic manifestations: Fever, malaise, and seizures.

Systemic manifestations: Fever, malaise, and seizures.

Inflammatory diarrhea: Fever, severe abdominal pain, tenesmus. May have blood/mucus

in stool.

Inflammatory diarrhea: Fever, severe abdominal pain, tenesmus. May have blood/mucus

in stool.

Noninflammatory diarrhea: Emesis, fever usually absent, crampy abdominal pain,

watery diarrhea.

Noninflammatory diarrhea: Emesis, fever usually absent, crampy abdominal pain,

watery diarrhea.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Diarrhea and emesis—noninflammatory

Diarrhea and emesis—noninflammatory

Diarrhea and fever—inflammatory process

Diarrhea and fever—inflammatory process

Diarrhea and tenesmus—large colon involvement

Diarrhea and tenesmus—large colon involvement

DIAGNOSIS

Examine stool for mucus, blood, and leukocytes (colitis).

Examine stool for mucus, blood, and leukocytes (colitis).

Fecal leukocyte: Presence of invasive cytotoxin organisms (Shigella, Salmonella).

Fecal leukocyte: Presence of invasive cytotoxin organisms (Shigella, Salmonella).

Patients with enterohemorrhagic E. coli and Entamoeba histolytica: Minimal to no fecal leukocytes.

Patients with enterohemorrhagic E. coli and Entamoeba histolytica: Minimal to no fecal leukocytes.

Obtain stool cultures early.

Obtain stool cultures early.

Clostridium difficile toxins: Test if recent antibiotic use.

Clostridium difficile toxins: Test if recent antibiotic use.

Proctosigmoidoscopy: Diagnosis of inflammatory enteritis.

Proctosigmoidoscopy: Diagnosis of inflammatory enteritis.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Diarrhea is a characteristic finding in children poisoned with bacterial toxin of Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Staphylococcus aureus, and Vibrio parahemolyticus, but not Clostridium botulinum.

TREATMENT

Rehydration.

Rehydration.

Oral electrolyte solutions (e.g., Pedialyte®).

Oral electrolyte solutions (e.g., Pedialyte®).

Oral hydration for all but severely dehydrated (IV hydration).

Oral hydration for all but severely dehydrated (IV hydration).

Rapid rehydration with replacement of ongoing losses during first 4–6 hours.

Rapid rehydration with replacement of ongoing losses during first 4–6 hours.

Do not use soda, fruit juices, gelatin, or tea. High osmolality may exacerbate

diarrhea.

Do not use soda, fruit juices, gelatin, or tea. High osmolality may exacerbate

diarrhea.

Start food with BRAT diet.

Start food with BRAT diet.

Antidiarrheal compounds are not indicated for use in children.

Antidiarrheal compounds are not indicated for use in children.

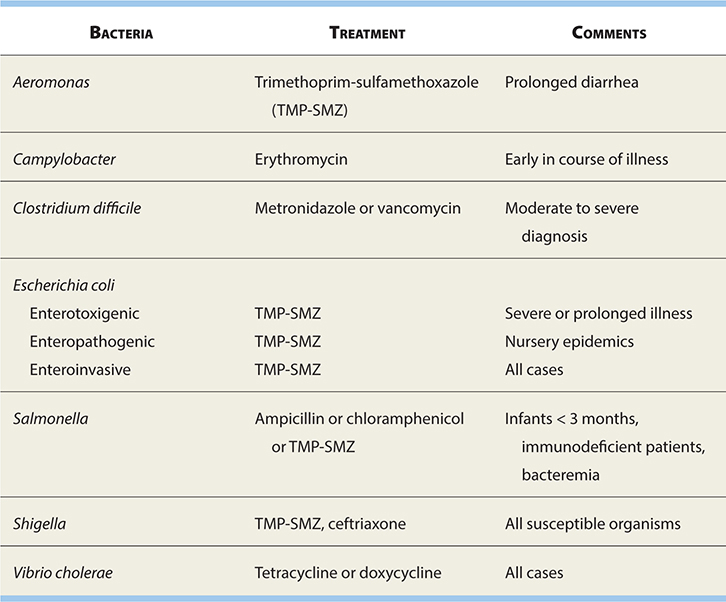

See Table 11-2 for antibiotic treatment of enteropathogens (wait for diagnosis via stool culture,

empiric antibiotics generally not indicated).

See Table 11-2 for antibiotic treatment of enteropathogens (wait for diagnosis via stool culture,

empiric antibiotics generally not indicated).

TABLE 11-2. Antimicrobial Treatment for Bacterial Enteropathogens

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

BRAT Diet for Diarrhea

Bananas

Rice

Applesauce

Toast

Prevention

Hospitalized patients should be placed under contact precautions (hand washing,

gloves, gowns, etc.).

Hospitalized patients should be placed under contact precautions (hand washing,

gloves, gowns, etc.).

Education.

Education.

Exclude infected children from child care centers.

Exclude infected children from child care centers.

Report cases of bacterial diarrhea to local health department.

Report cases of bacterial diarrhea to local health department.

Vaccines for cholera and Salmonella typhi are available.

Vaccines for cholera and Salmonella typhi are available.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Do not treat E. coli O157:H7 with antibiotics, as there is a higher incidence of hemolytic uremic syndrome with treatment.

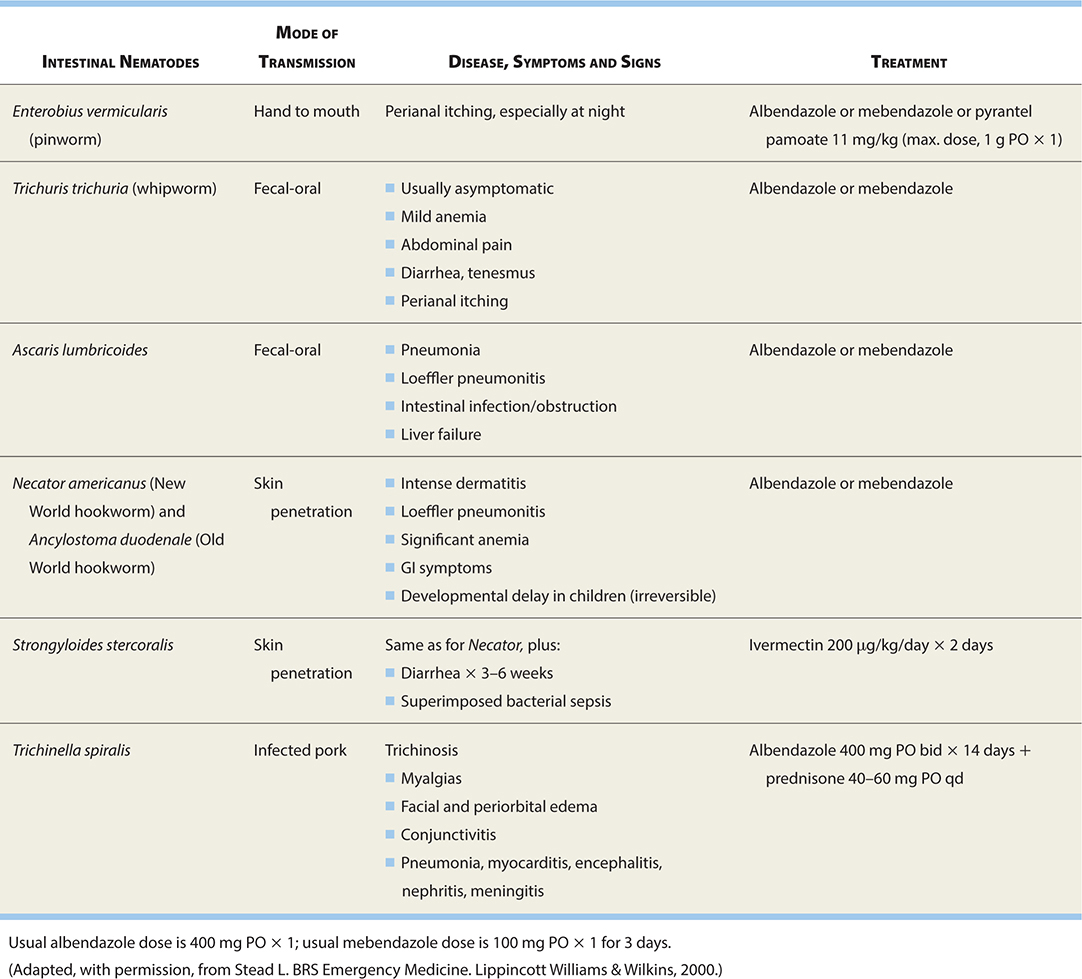

Intestinal Worms

See Table 11-3 for common intestinal worm infestations.

TABLE 11-3. Common Intestinal Worms

Pseudomembranous Colitis

DEFINITION

Major cause of iatrogenic diarrhea.

Major cause of iatrogenic diarrhea.

Rarely occurs without antecedent antibiotics (usually) penicillins, cephalosporins,

or clindamycin.

Rarely occurs without antecedent antibiotics (usually) penicillins, cephalosporins,

or clindamycin.

Antibiotic disrupts normal bowel flora and predisposes to C. difficile diarrhea.

Antibiotic disrupts normal bowel flora and predisposes to C. difficile diarrhea.

Stool should be tested for C. difficile toxins if there is a recent history of antibiotic use.

Stool should be tested for C. difficile toxins if there is a recent history of antibiotic use.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

The most frequent symptom of infestation with Enterobius vermicularis is perineal pruritus. Can diagnose with transparent adhesive tape to area (worms stick).

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Classically, blood and mucus with fever, cramps, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting days or weeks after antibiotics.

DIAGNOSIS

Recent history of antibiotic use.

Recent history of antibiotic use.

C. difficile toxin in stool of patient with diarrhea.

C. difficile toxin in stool of patient with diarrhea.

Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

TREATMENT

Discontinue antibiotics.

Discontinue antibiotics.

Oral metronidazole or vancomycin × 7–10 days.

Oral metronidazole or vancomycin × 7–10 days.

Abdominal Hernias

UMBILICAL

DEFINITION

Occurs because of imperfect closure of umbilical ring.

Occurs because of imperfect closure of umbilical ring.

Common in low-birth-weight, female, and African-American infants.

Common in low-birth-weight, female, and African-American infants.

Soft swelling covered by skin that protrudes while crying, straining, or coughing.

Soft swelling covered by skin that protrudes while crying, straining, or coughing.

Omentum or portions of small intestine involved.

Omentum or portions of small intestine involved.

Usually 1–5 cm.

Usually 1–5 cm.

TREATMENT

Most disappear spontaneously by 1 year of age.

Most disappear spontaneously by 1 year of age.

Strangulation rare.

Strangulation rare.

“Strapping” ineffective.

“Strapping” ineffective.

Surgery not indicated unless symptomatic, strangulated, or grows larger after age

1 or 2.

Surgery not indicated unless symptomatic, strangulated, or grows larger after age

1 or 2.

INGUINAL

DEFINITION

Most common diagnosis requiring surgery.

Most common diagnosis requiring surgery.

Occurs in 10–20/1,000 live births (50% <1 year).

Occurs in 10–20/1,000 live births (50% <1 year).

Indirect > direct (rare) > femoral (even more rare).

Indirect > direct (rare) > femoral (even more rare).

Indirect secondary to patent processus vaginalis.

Indirect secondary to patent processus vaginalis.

↑ incidence with positive family history.

↑ incidence with positive family history.

Embryology: Patent processus vaginalis.

Embryology: Patent processus vaginalis.

Incidence: 1–5%.

Incidence: 1–5%.

Males > females 8–10:1.

Males > females 8–10:1.

Preemies: 20% males, 2% females.

Preemies: 20% males, 2% females.

Premature infants have ↑ risk for inguinal hernia.

Premature infants have ↑ risk for inguinal hernia.

Sixty percent right (delayed descent of the right testicle), 30% left, 10% bilateral.

Sixty percent right (delayed descent of the right testicle), 30% left, 10% bilateral.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

In inguinal hernia, processus vaginalis herniates through abdominal wall with hydrocele into canal.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Infant with scrotal/inguinal bulge on straining or crying.

Infant with scrotal/inguinal bulge on straining or crying.

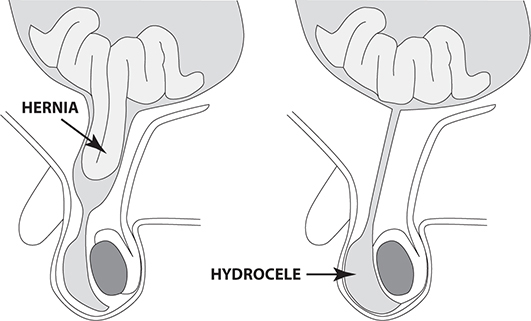

Do careful exam to distinguish from hydrocele (see Figure 11-9).

Do careful exam to distinguish from hydrocele (see Figure 11-9).

FIGURE 11-9. Inguinal hernia (slippage of bowel through inguinal ring) vs. hydrocele (collection of fluid in scrotum adjacent to testes).

Bulge in groin ± scrotum, incarceration.

Bulge in groin ± scrotum, incarceration.

TREATMENT

Surgery (elective).

Surgery (elective).

Avoid trusses or supports.

Avoid trusses or supports.

Contralateral hernia occurs in 30% after unilateral repair.

Contralateral hernia occurs in 30% after unilateral repair.

Antibiotics only in at-risk children (e.g., congenital heart disease).

Antibiotics only in at-risk children (e.g., congenital heart disease).

Prognosis excellent (recurrence <1%, complication rate approximately 2%, infection

approximately 1%).

Prognosis excellent (recurrence <1%, complication rate approximately 2%, infection

approximately 1%).

Complications include incarceration.

Complications include incarceration.

Therapy: Incarceration––sedation and manipulation 90–95% reduced. Immediate operation

if not reduced. Repair soon after diagnosis especially infants since 60% progress

to incarceration by 6 months.

Therapy: Incarceration––sedation and manipulation 90–95% reduced. Immediate operation

if not reduced. Repair soon after diagnosis especially infants since 60% progress

to incarceration by 6 months.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Inguinal hernia ↑ with straining; hydrocele remains unchanged.

Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

A 15-year-old girl with spots on her lips has some crampy abdominal pain associated

with bleeding. Think: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

A 15-year-old girl with spots on her lips has some crampy abdominal pain associated

with bleeding. Think: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is multiple GI hamartomatous polyps + mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation. There is a higher risk of intestinal and extraintestinal malignancies.

DEFINITION

Mucosal pigmentation of lips and gums with hamartomas of stomach, small intestine,

and colon.

Mucosal pigmentation of lips and gums with hamartomas of stomach, small intestine,

and colon.

Rare; low malignant potential.

Rare; low malignant potential.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Deeply pigmented freckles on lips and buccal mucosa at birth.

Deeply pigmented freckles on lips and buccal mucosa at birth.

Bleeding and crampy abdominal pain.

Bleeding and crampy abdominal pain.

DIAGNOSIS

Genetic and family studies may reveal history.

TREATMENT

Excise intestinal lesions if significantly symptomatic.

Gardner Syndrome

DEFINITION

Multiple intestinal polyps, tumors of soft tissue and bone (especially mandible).

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Dental abnormalities.

Dental abnormalities.

Pigmented lesions in ocular fundus.

Pigmented lesions in ocular fundus.

Intestinal polyps (usually early adulthood) with high malignant potential.

Intestinal polyps (usually early adulthood) with high malignant potential.

DIAGNOSIS

Genetic counseling.

Genetic counseling.

Colon surveillance in at-risk children.

Colon surveillance in at-risk children.

TREATMENT

Aggressive surgical removal of polyps.

Carcinoid Tumors

DEFINITION

Tumors of enterochromaffin cells in intestine—usually appendix.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

May cause appendicitis.

May cause appendicitis.

May cause carcinoid syndrome (↑ serotonin, vasomotor disturbances, or bronchoconstriction)

if metastatic to the liver.

May cause carcinoid syndrome (↑ serotonin, vasomotor disturbances, or bronchoconstriction)

if metastatic to the liver.

TREATMENT

Surgical excision.

Familial Polyposis Coli

DEFINITION/ETIOLOGY

Autosomal dominant.

Autosomal dominant.

Large number of adenomatous lesions in colon.

Large number of adenomatous lesions in colon.

Secondary to germ-line mutations in adenopolyposis coli (APC) gene.

Secondary to germ-line mutations in adenopolyposis coli (APC) gene.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Highly variable.

Highly variable.

May see hematochezia, cramps, or diarrhea.

May see hematochezia, cramps, or diarrhea.

Extracolonic manifestations possible.

Extracolonic manifestations possible.

DIAGNOSIS

Consider family history (strong).

Consider family history (strong).

Colonoscopy with biopsy (screening annually after 10 years old if positive family

history).

Colonoscopy with biopsy (screening annually after 10 years old if positive family

history).

TREATMENT

Surgical resection of affected colonic mucosa.

Juvenile Polyposis Coli

DEFINITION

Most common childhood bowel tumor (3–4% of patients <21 years).

Most common childhood bowel tumor (3–4% of patients <21 years).

Characteristically, mucus-filled cystic glands (no adenomatous changes, no potential

for malignancy).

Characteristically, mucus-filled cystic glands (no adenomatous changes, no potential

for malignancy).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Most commonly between 2 and 10 years; less common after 15 years; rarely before 1 year.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Bright-red painless bleeding with bowel movement.

Bright-red painless bleeding with bowel movement.

Iron deficiency.

Iron deficiency.

DIAGNOSIS

Colonoscopy.

Colonoscopy.

May use barium enema (not best test).

May use barium enema (not best test).

TREATMENT

Surgical removal of polyp.

Malabsorption

SHORT BOWEL SYNDROME

DEFINITION

Occurs with loss of at least 50% of small bowel (with or without loss of large

bowel).

Occurs with loss of at least 50% of small bowel (with or without loss of large

bowel).

↓ absorptive surface and bowel function.

↓ absorptive surface and bowel function.

ETIOLOGY

May be congenital (malrotation, atresia, etc.).

May be congenital (malrotation, atresia, etc.).

Most commonly secondary to surgical resection.

Most commonly secondary to surgical resection.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Malabsorption and diarrhea.

Malabsorption and diarrhea.

Steatorrhea (fatty stools): Voluminous foul-smelling stools that float.

Steatorrhea (fatty stools): Voluminous foul-smelling stools that float.

Dehydration.

Dehydration.

↓ sodium and potassium.

↓ sodium and potassium.

Acidosis (secondary to loss of bicarbonate).

Acidosis (secondary to loss of bicarbonate).

TREATMENT

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

Give small feeds orally.

Give small feeds orally.

Metronidazole empirically to treat bacterial overgrowth.

Metronidazole empirically to treat bacterial overgrowth.

CELIAC DISEASE

A 5-year-old girl presents with a protuberant abdomen and wasted extremities. Think: Gluten-induced enteropathy.

A 5-year-old girl presents with a protuberant abdomen and wasted extremities. Think: Gluten-induced enteropathy.

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder. The disease primarily affects the small intestine. Gluten is the single major factor that triggers celiac disease. Gluten-containing foods include rye, wheat, and barley. Common presentation: diarrhea, borborygmus, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Other systems, including skin, liver, nervous system, bones, reproductive system, and endocrine system, may also be affected. Serologic marker: Serum immunoglobulin A (IgA) endomysial antibodies and IgA tissue transglutaminase (tTG) antibodies.

DEFINITION

Sensitivity to gluten in diet.

Sensitivity to gluten in diet.

Most commonly occurs between 6 months and 2 years.

Most commonly occurs between 6 months and 2 years.

ETIOLOGY

Factors involved include cereals, genetic predisposition, and environmental factors.

Factors involved include cereals, genetic predisposition, and environmental factors.

Associated with HLA-B8, -DR7, -DR3, and -DQW2.

Associated with HLA-B8, -DR7, -DR3, and -DQW2.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Diarrhea.

Diarrhea.

Failure to thrive.

Failure to thrive.

Vomiting.

Vomiting.

Pallor.

Pallor.

Abdominal distention.

Abdominal distention.

Large bulky stools.

Large bulky stools.

DIAGNOSIS

Anti-endomysial and anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies (check total lgH level

at the same time).

Anti-endomysial and anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies (check total lgH level

at the same time).

Biopsy: Most reliable test.

Biopsy: Most reliable test.

TREATMENT

Dietary restriction of gluten (must avoid barley, ryes, oats, and wheat).

Dietary restriction of gluten (must avoid barley, ryes, oats, and wheat).

Corticosteroids used rarely (very ill patients with profound malnutrition, diarrhea,

edema, and hypokalemia).

Corticosteroids used rarely (very ill patients with profound malnutrition, diarrhea,

edema, and hypokalemia).

TROPICAL SPRUE

DEFINITION

Generalized malabsorption associated with diffuse lesions of small bowel mucosa.

Generalized malabsorption associated with diffuse lesions of small bowel mucosa.

Seen in people who live or have traveled to certain tropical regions—some Caribbean

countries, South America, Africa, or parts of Asia.

Seen in people who live or have traveled to certain tropical regions—some Caribbean

countries, South America, Africa, or parts of Asia.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Fever, malaise, and watery diarrhea, acutely.

Fever, malaise, and watery diarrhea, acutely.

After 1 week, chronic malabsorption and signs of malnutrition including night blindness,

glossitis, stomatitis, cheilosis, muscle wasting.

After 1 week, chronic malabsorption and signs of malnutrition including night blindness,

glossitis, stomatitis, cheilosis, muscle wasting.

DIAGNOSIS

Biopsy shows villous shortening, ↑ crypt depth, and ↑ chronic inflammatory cells in lamina propria of small bowel.

TREATMENT

Antibiotics × 3–4 weeks.

Antibiotics × 3–4 weeks.

Folate.

Folate.

Vitamin B12.

Vitamin B12.

Prognosis excellent.

Prognosis excellent.

LACTASE DEFICIENCY

DEFINITION

↓ or absent enzyme that breaks down lactose in the intestinal brush border.

ETIOLOGY

Congenital absence reported in few cases.

Congenital absence reported in few cases.

Usual mechanism relates to developmental pattern of lactase activity.

Usual mechanism relates to developmental pattern of lactase activity.

Autosomal recessive.

Autosomal recessive.

Also ↓ because of diffuse mucosal disease (can occur post viral gastroenteritis).

Also ↓ because of diffuse mucosal disease (can occur post viral gastroenteritis).

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Seen in response to ingestion of lactose (found in dairy products).

Seen in response to ingestion of lactose (found in dairy products).

Explosive watery diarrhea with abdominal distention, borborygmi, and flatulence.

Explosive watery diarrhea with abdominal distention, borborygmi, and flatulence.

Recurrent, vague abdominal pain.

Recurrent, vague abdominal pain.

Episodic midabdominal pain (may or may not be related to milk intake).

Episodic midabdominal pain (may or may not be related to milk intake).

TREATMENT

Eliminate milk from diet.

Eliminate milk from diet.

Oral lactase supplement (Lactaid) or lactose-free milk.

Oral lactase supplement (Lactaid) or lactose-free milk.

Yogurt (with lactase enzyme–producing bacteria tolerable in such patients).

Yogurt (with lactase enzyme–producing bacteria tolerable in such patients).

Hyperbilirubinemia

Physiology: See Gestation and Birth chapter.

DEFINITION

Elevated serum bilirubin.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Common and in most cases benign.

Common and in most cases benign.

If untreated, severe indirect hyperbilirubinemia neurotoxic (kernic-terus).

If untreated, severe indirect hyperbilirubinemia neurotoxic (kernic-terus).

Jaundice in first week of life in 60% of term and 80% of preterm infants—results

from accumulation of unconjugated bilirubin pigment.

Jaundice in first week of life in 60% of term and 80% of preterm infants—results

from accumulation of unconjugated bilirubin pigment.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Jaundice at birth or in neonatal period.

Jaundice at birth or in neonatal period.

May be lethargic and feed poorly.

May be lethargic and feed poorly.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Indirect hyperbilirubinemia, reticulosis, and red cell destruction suggest hemolysis.

Indirect hyperbilirubinemia, reticulosis, and red cell destruction suggest hemolysis.

Direct hyperbilirubinemia may indicate hepatitis, cholestasis, inborn errors of

metabolism, cystic fibrosis, or sepsis.

Direct hyperbilirubinemia may indicate hepatitis, cholestasis, inborn errors of

metabolism, cystic fibrosis, or sepsis.

If reticulocyte count, Coombs’, and direct bilirubin are normal, then physiologic

or pathologic indirect hyperbilirubinemia is suggested.

If reticulocyte count, Coombs’, and direct bilirubin are normal, then physiologic

or pathologic indirect hyperbilirubinemia is suggested.

DIAGNOSIS

Direct and indirect bilirubin fractions.

Direct and indirect bilirubin fractions.

Hemoglobin.

Hemoglobin.

Reticulocyte count.

Reticulocyte count.

Blood type.

Blood type.

Examine peripheral smear.

Examine peripheral smear.

TREATMENT

Goal is to prevent neurotoxic range.

Goal is to prevent neurotoxic range.

Phototherapy.

Phototherapy.

Exchange transfusion.

Exchange transfusion.

Treat underlying cause.

Treat underlying cause.

GILBERT SYNDROME

Benign condition caused by missense mutation in transferase gene resulting in low enzyme levels with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Children with cholestatic hepatic disease need replacement of vitamins A, D, E, and K (fat soluble).

CRIGLER-NAJJAR I SYNDROME

DEFINITION

Autosomal recessive, secondary to mutations in glucuronyl transferase gene.

Autosomal recessive, secondary to mutations in glucuronyl transferase gene.

Parents of affected children show partial defects but normal serum bilirubin concentration.

Parents of affected children show partial defects but normal serum bilirubin concentration.

Complete absence of the enzyme uridine diphosphate glycosyltransferase.

Complete absence of the enzyme uridine diphosphate glycosyltransferase.

Much rarer than Gilbert syndrome.

Much rarer than Gilbert syndrome.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

In homozygous infants, will see unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in first 3 days

of life.

In homozygous infants, will see unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in first 3 days

of life.

Kernicterus common in early neonatal period.

Kernicterus common in early neonatal period.

Some treated infants survive childhood without sequelae.

Some treated infants survive childhood without sequelae.

Stools pale yellow.

Stools pale yellow.

Persistence of ↑ levels of indirect bilirubin after first week of life in absence

of hemolysis suggests this syndrome.

Persistence of ↑ levels of indirect bilirubin after first week of life in absence

of hemolysis suggests this syndrome.

DIAGNOSIS

Based on early age of onset and extreme level of bilirubin in absence of hemolysis.

Based on early age of onset and extreme level of bilirubin in absence of hemolysis.

Definitive diagnosis made by measuring glucuronyl transferase activity in liver

biopsy specimen.

Definitive diagnosis made by measuring glucuronyl transferase activity in liver

biopsy specimen.

DNA diagnosis available.

DNA diagnosis available.

TREATMENT

Maintain serum bilirubin <20 mg/dL for first 2–4 weeks of life.

Maintain serum bilirubin <20 mg/dL for first 2–4 weeks of life.

Repeated exchange transfusion.

Repeated exchange transfusion.

Phototherapy.

Phototherapy.

Treat intercurrent infections.

Treat intercurrent infections.

Hepatic transplant.

Hepatic transplant.

CRIGLER-NAJJAR II SYNDROME

DEFINITION

Autosomal dominant with variable penetrance.

Autosomal dominant with variable penetrance.

May be caused by homozygous mutation in glucuronyl transferase isoform I activity.

May be caused by homozygous mutation in glucuronyl transferase isoform I activity.

↓ enzyme uridine diphosphate glycosyltransferase.

↓ enzyme uridine diphosphate glycosyltransferase.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in first 3 days of life.

Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in first 3 days of life.

Concentration remains ↑ after third week of life.

Concentration remains ↑ after third week of life.

Kernicterus unusual.

Kernicterus unusual.

Stool normal.

Stool normal.

Infants asymptomatic.

Infants asymptomatic.

DIAGNOSIS

Concentration of bilirubin nearly normal.

Concentration of bilirubin nearly normal.

↓ bilirubin after 7- to 10-day treatment with phenobarbital may be diagnostic.

↓ bilirubin after 7- to 10-day treatment with phenobarbital may be diagnostic.

TREATMENT