Neurologic Disease

NIGHT TERRORS (PAVOR NOCTURNAS)

Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

ANTI-NMDA RECEPTOR ENCEPHALITIS

INCREASED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE (ICP)

Arteriovenous Malformations (AVMs)

CLINICALLY RELEVANT TYPES OF STROKE

AGENESIS OF THE CORPUS CALLOSUM

Seizures

DEFINITION

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

The diagnosis of clinical epilepsy requires two or more unprovoked seizures.

A paroxysmal electrical discharge of neurons in the brain resulting in an alteration

of function or behavior.

A paroxysmal electrical discharge of neurons in the brain resulting in an alteration

of function or behavior.

The most common neurologic disorder in children:

The most common neurologic disorder in children:

4–10% of children.

4–10% of children.

1% of all ED visits.

1% of all ED visits.

Highest incidence: <3 years.

Highest incidence: <3 years.

ETIOLOGY

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Recurrence risk after a first unprovoked episode is 45% (27–52%).

Recurrence risk after a first unprovoked episode is 45% (27–52%).

The risk of epilepsy is >70% after two unprovoked episodes.

The risk of epilepsy is >70% after two unprovoked episodes.

Multiple etiologies have been identified for seizures. Provoked causes include:

Fever.

Fever.

Metabolic:

Metabolic:

Hypoglycemia.

Hypoglycemia.

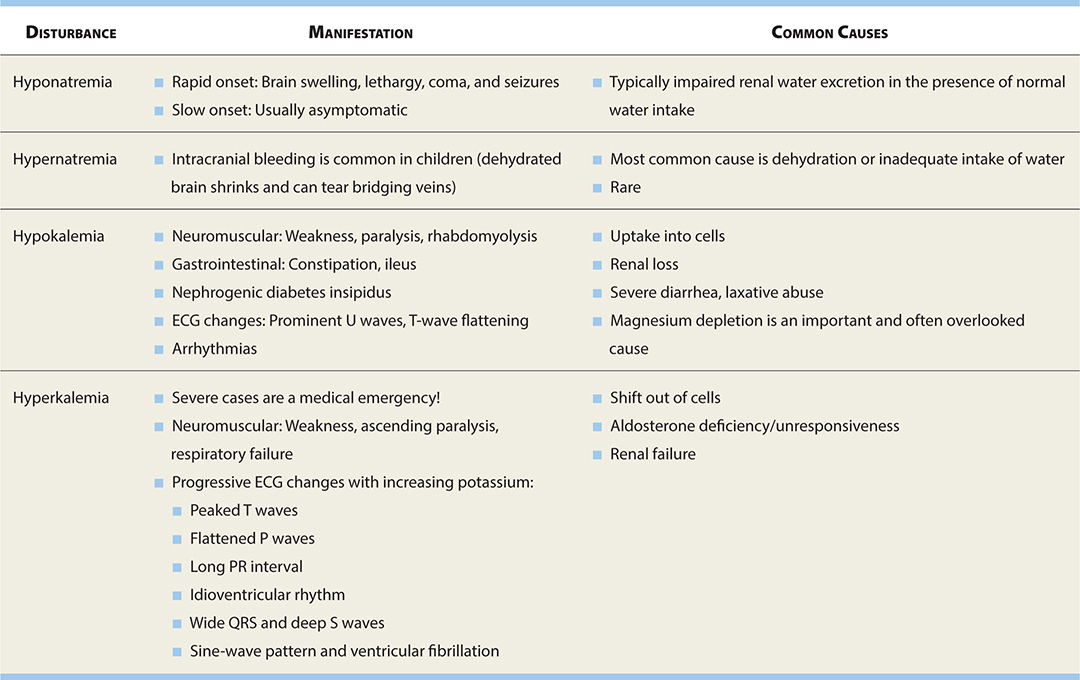

Hyponatremia.

Hyponatremia.

Hypocalcemia.

Hypocalcemia.

Inborn errors of metabolism.

Inborn errors of metabolism.

Medications and illegal drugs.

Medications and illegal drugs.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

In most children with seizures, an underlying cause cannot be determined and a diagnosis of idiopathic epilepsy is given.

Trauma (intracranial hemorrhage).

Trauma (intracranial hemorrhage).

Infections (encephalitis, meningitis, abscess).

Infections (encephalitis, meningitis, abscess).

Vascular events (strokes).

Vascular events (strokes).

Hypoxic ischemia encephalopathy.

Hypoxic ischemia encephalopathy.

Idiopathic.

Idiopathic.

TYPES OF SEIZURES

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Partial seizures: Onset in one brain region.

Generalized seizures: Onset simultaneously in both cerebral hemispheres.

See Table 17-1.

Partial (Focal) Seizures

Begin in one brain region.

1. Simple partial seizures:

Average duration is 10–20 seconds.

Average duration is 10–20 seconds.

Restricted at onset to one focal cortical region.

Restricted at onset to one focal cortical region.

Consciousness is not altered.

Consciousness is not altered.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Aura: Abnormal perception or hallucination, which occurs before consciousness is lost and for which memory is returned afterwards. In seizure, as opposed to migraine, the aura is part of the seizure.

Tend to involve the face, neck, and extremities.

Tend to involve the face, neck, and extremities.

Patients may complain of aura, which is characteristic for the brain region involved

in the seizure (i.e., visual aura, auditory aura, etc.).

Patients may complain of aura, which is characteristic for the brain region involved

in the seizure (i.e., visual aura, auditory aura, etc.).

Seizures can also be somatosensory/visual or auditory.

Seizures can also be somatosensory/visual or auditory.

2. Complex partial seizures:

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Both simple and complex partial seizures may become generalized.

Average duration is 1–2 minutes.

Average duration is 1–2 minutes.

Hallmark feature is alteration or loss of consciousness.

Hallmark feature is alteration or loss of consciousness.

Automatisms are seen in 50–75% of cases (psychic, sensory, or motor phenomena).

Automatisms are seen in 50–75% of cases (psychic, sensory, or motor phenomena).

3. Secondarily generalized seizures:

Starts as a partial seizure in a focal area of the brain and then spread to the

entire brain leading to a generalized seizure.

Starts as a partial seizure in a focal area of the brain and then spread to the

entire brain leading to a generalized seizure.

Sometimes the person does not recall the first part of the seizure.

Sometimes the person does not recall the first part of the seizure.

Occurs in >30% of people with partial epilepsy.

Occurs in >30% of people with partial epilepsy.

Generalized Seizures

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

The first step in evaluating any seizure disorder is determining the type of seizure.

Begins simultaneously in both cerebral hemispheres. Consciousness is impaired from seizure onset.

1. Typical absence seizures (formerly “petit mal”):

Generalized seizure.

Generalized seizure.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Motor activity is the most common symptom of simple partial seizures.

Characterized by sudden cessation of motor activity or speech.

Characterized by sudden cessation of motor activity or speech.

Brief stares (usually <10 seconds), rarely longer than 30 seconds.

Brief stares (usually <10 seconds), rarely longer than 30 seconds.

More common in girls. Male-to-female ratio: 2:1.

More common in girls. Male-to-female ratio: 2:1.

Onset 4-10 years.

Onset 4-10 years.

Can occur many times throughout the day.

Can occur many times throughout the day.

There is no aura.

There is no aura.

There is no postictal state.

There is no postictal state.

Seizure can be elicited by hyperventilation.

Seizure can be elicited by hyperventilation.

Childhood absence epilepsy is associated with characteristic 3-Hz spike-and-wave

pattern (Figure 17-1) on EEG.

Childhood absence epilepsy is associated with characteristic 3-Hz spike-and-wave

pattern (Figure 17-1) on EEG.

FIGURE 17-1. Absence seizure EEG. Characteristic 3-Hz spike and wave pattern.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

The presence of an aura always indicates a focal onset of the seizure. Physiologically, an aura is simply the earliest conscious manifestation of a seizure and corresponds with area of brain involved.

2. Generalized tonic-clonic (GTC, formerly “grand mal”) seizures:

Extremely common and may follow a partial seizure with focal onset.

Extremely common and may follow a partial seizure with focal onset.

Patients suddenly lose consciousness, their eyes roll back, and their entire musculature

undergoes tonic contractions, rarely arresting breathing.

Patients suddenly lose consciousness, their eyes roll back, and their entire musculature

undergoes tonic contractions, rarely arresting breathing.

Gradually, the hyperextension gives way to a series of rapid clonic jerks.

Gradually, the hyperextension gives way to a series of rapid clonic jerks.

Finally, a period of flaccid relaxation occurs, during which sphincter control

is often lost (incontinence).

Finally, a period of flaccid relaxation occurs, during which sphincter control

is often lost (incontinence).

Prodromal symptoms (not aura) often precede the attack by several hours and include

mood change, apprehension, insomnia, or loss of appetite. (Unclear if these are warning

signs or part of the cause.)

Prodromal symptoms (not aura) often precede the attack by several hours and include

mood change, apprehension, insomnia, or loss of appetite. (Unclear if these are warning

signs or part of the cause.)

Absence Versus Complex Partial Seizures

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Automatisms are a common symptom of complex partial seizures.

While examining an 8-year-old girl in your office, the child suddenly develops a

blank stare and flickering eyelids. Twenty seconds later she returns to normal and

acts as if nothing out of the ordinary has occurred. Think: Absence seizure.

While examining an 8-year-old girl in your office, the child suddenly develops a

blank stare and flickering eyelids. Twenty seconds later she returns to normal and

acts as if nothing out of the ordinary has occurred. Think: Absence seizure.

You are reviewing the history before seeing a patient. She is a 7-year-old bright

girl with no significant past medical history. The schoolteacher noted that she sometimes

does not respond when her name is called. Also, she stares in space with a blank look

momentarily. Think: Absence seizures.

You are reviewing the history before seeing a patient. She is a 7-year-old bright

girl with no significant past medical history. The schoolteacher noted that she sometimes

does not respond when her name is called. Also, she stares in space with a blank look

momentarily. Think: Absence seizures.

PEDIATRIC SEIZURE DISORDERS

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Absence Seizures

Shorter (seconds)

Shorter (seconds)

Automatism –

Automatism –

More frequent (dozens)

More frequent (dozens)

Quick recovery

Quick recovery

Hyperventilation +

Hyperventilation +

EEG: 3/sec spikes and waves

EEG: 3/sec spikes and waves

Complex Partial Seizures

Longer (minutes)

Longer (minutes)

Automatism +

Automatism +

Less frequent

Less frequent

Gradual recovery

Gradual recovery

Hyperventilation –

Hyperventilation –

EEG: Focal spikes

EEG: Focal spikes

Simple Febrile Seizure

The most common seizure disorder during childhood.

The most common seizure disorder during childhood.

Occurs in approximately 2–4% of children younger than 5 years with a peak incidence

between 12 and 18 months.

Occurs in approximately 2–4% of children younger than 5 years with a peak incidence

between 12 and 18 months.

Present as a brief tonic-clonic seizure associated with a fever.

Present as a brief tonic-clonic seizure associated with a fever.

Risk of recurrence is 30% after first episode and 50% after second episode.

Risk of recurrence is 30% after first episode and 50% after second episode.

Highest recurrence if episode before 1 year of age (50%).

Highest recurrence if episode before 1 year of age (50%).

Antipyretics do not appear to prevent the onset of future febrile seizures.

Antipyretics do not appear to prevent the onset of future febrile seizures.

There are no long-term sequelae, and most children will outgrow by age 6.

There are no long-term sequelae, and most children will outgrow by age 6.

Risk of epilepsy (1–2% as opposed to 0.5–1% in the general population) not statistically

significant.

Risk of epilepsy (1–2% as opposed to 0.5–1% in the general population) not statistically

significant.

↑ risk of epilepsy (up to 13%) in the presence of:

↑ risk of epilepsy (up to 13%) in the presence of:

Abnormal neurologic examination.

Abnormal neurologic examination.

Complex febrile seizure (lasting >15 minutes, focal in nature, and/or recurrent

seizure within 24 hours).

Complex febrile seizure (lasting >15 minutes, focal in nature, and/or recurrent

seizure within 24 hours).

Family history of epilepsy.

Family history of epilepsy.

Among first-degree relatives 10–20% of parents and siblings also have had febrile

seizures. An autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance is

demonstrated in some families (19p and 8q13–21).

Among first-degree relatives 10–20% of parents and siblings also have had febrile

seizures. An autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance is

demonstrated in some families (19p and 8q13–21).

Consider meningitis or toxin exposures for a febrile seizure >15 minutes. Have

a greater consideration for spinal tap in infants <1 year of age or in those with

clinical signs of meningitis.

Consider meningitis or toxin exposures for a febrile seizure >15 minutes. Have

a greater consideration for spinal tap in infants <1 year of age or in those with

clinical signs of meningitis.

Neonatal Seizure

The most common neurologic manifestation of impaired brain function.

The most common neurologic manifestation of impaired brain function.

Occurs in 1.8–3.5 of every 1000 newborns.

Occurs in 1.8–3.5 of every 1000 newborns.

Higher incidence in low-birth-weight infants.

Higher incidence in low-birth-weight infants.

Metabolic, toxic, hypoxic, ischemic, and infectious diseases are commonly present

during the neonatal period, placing the child at an ↑ risk for seizures.

Metabolic, toxic, hypoxic, ischemic, and infectious diseases are commonly present

during the neonatal period, placing the child at an ↑ risk for seizures.

Myelination is not complete at birth; thus, GTC seizures are very uncommon in the

first month of life.

Myelination is not complete at birth; thus, GTC seizures are very uncommon in the

first month of life.

May manifest as tonic, myoclonic, clonic, or subtle (prolonged nonnutritive sucking,

nystagmus, color change, autonomic instability).

May manifest as tonic, myoclonic, clonic, or subtle (prolonged nonnutritive sucking,

nystagmus, color change, autonomic instability).

EEG may show burst suppression (alternating high and very low voltages), low-voltage

invariance, diffuse or focal background slowing, and focal or multifocal spikes.

EEG may show burst suppression (alternating high and very low voltages), low-voltage

invariance, diffuse or focal background slowing, and focal or multifocal spikes.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Benign neonatal familial convulsions (“fifth-day fits”) are a brief self-limited autosomal-dominant condition with generalized seizures beginning in the first week of life and subsiding within 6 weeks. There is a normal interictal EEG. There is a 10–15% chance of future epilepsy, but otherwise carries an excellent prognosis. Always elicit a family history in neonatal seizures usually revealed after interviewing grandparents.

Neonatal seizures are typically treated acutely with phenobarbital (drug of choice),

fosphenytoin, or benzodiazepines.

Neonatal seizures are typically treated acutely with phenobarbital (drug of choice),

fosphenytoin, or benzodiazepines.

Phenytoin not a first-line agent due to depressive effect on the myocardium and

variable metabolism in newborns.

Phenytoin not a first-line agent due to depressive effect on the myocardium and

variable metabolism in newborns.

Other antiseizure drugs, such as levetiracetam or topiramate, are being increasingly

used for treatment of neonatal seizures but are not yet considered evidence-based

first-line agents.

Other antiseizure drugs, such as levetiracetam or topiramate, are being increasingly

used for treatment of neonatal seizures but are not yet considered evidence-based

first-line agents.

Infantile Spasm

Onset: 4–7 months.

Onset: 4–7 months.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Immature neonatal brain is more excitable than older children.

Clusters of brief rapid symmetric flexor/extensor contractions of the neck, trunk,

and extremities up to 100 per day. Clusters can last <1 minute to 10–15 minutes.

Clusters of brief rapid symmetric flexor/extensor contractions of the neck, trunk,

and extremities up to 100 per day. Clusters can last <1 minute to 10–15 minutes.

Symptomatic type is most commonly seen with central nervous system (CNS) malformations,

brain injury, tuberous sclerosis, or inborn errors of metabolism, and typically has

a poor outcome.

Symptomatic type is most commonly seen with central nervous system (CNS) malformations,

brain injury, tuberous sclerosis, or inborn errors of metabolism, and typically has

a poor outcome.

Cryptogenic type has a better prognosis and children typically have an uneventful

birth history and reach developmental milestones before the onset of the seizures.

Cryptogenic type has a better prognosis and children typically have an uneventful

birth history and reach developmental milestones before the onset of the seizures.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

If you are present during a tonic–clonic seizure:

Keep track of the duration.

Keep track of the duration.

Place the patient between prone and lateral decubitus to allow the tongue and secretions

to fall forward.

Place the patient between prone and lateral decubitus to allow the tongue and secretions

to fall forward.

Loosen any tight clothing or jewelry around the neck.

Loosen any tight clothing or jewelry around the neck.

Do not try to force open the mouth or teeth!

Do not try to force open the mouth or teeth!

Treated with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in the United States.

Treated with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in the United States.

Vigabatrin (equally as effective as ACTH therapy).

Vigabatrin (equally as effective as ACTH therapy).

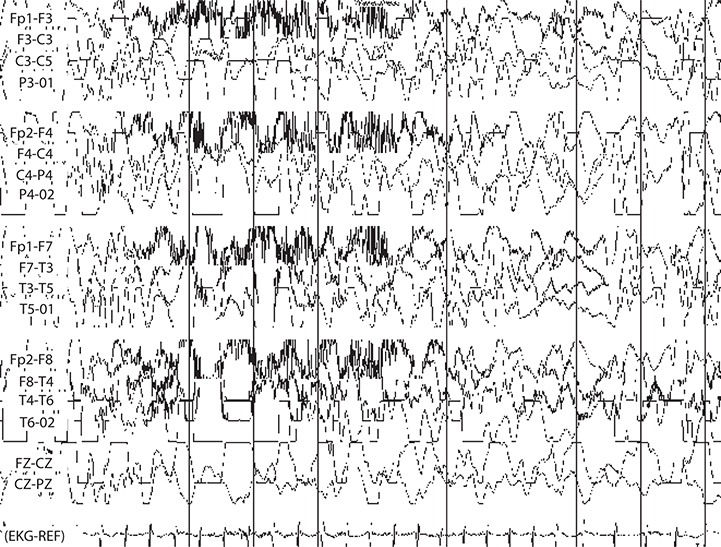

EEG has characteristic hypsarrhythmia pattern: Large-amplitude chaotic multifocal

spikes and slowing (see Figure 17-2).

EEG has characteristic hypsarrhythmia pattern: Large-amplitude chaotic multifocal

spikes and slowing (see Figure 17-2).

FIGURE 17-2. EEG demonstrating hypsarrhythmia pattern. Often seen in tuberous sclerosis, for example.

EPILEPSY

DEFINITION

A history of two or more unprovoked seizures.

A history of two or more unprovoked seizures.

After a nebulous period (on the order of 5–10 years) of seizure freedom without

the aid of antiepileptic medications or devices, the epilepsy can be considered to

have resolved, particularly if the patient fits an epilepsy syndrome that is known

typically to resolve.

After a nebulous period (on the order of 5–10 years) of seizure freedom without

the aid of antiepileptic medications or devices, the epilepsy can be considered to

have resolved, particularly if the patient fits an epilepsy syndrome that is known

typically to resolve.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

If the seizure is brief with fever and immediate complete recovery consistent with febrile seizure, then only good examination and clinically indicated laboratory evaluation are needed to find the cause of fever. CT/ EEG/LP are not routinely indicated.

Epilepsy occurs in 0.5–1% of the population and begins in childhood in 60% of the cases.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Vary depending on the seizure pattern. See above discussion of types of seizures.

Vary depending on the seizure pattern. See above discussion of types of seizures.

A seizure is defined electrographically as a hypersynchronous, hyperrhythmic, high-amplitude

signal that evolves in both frequency and space.

A seizure is defined electrographically as a hypersynchronous, hyperrhythmic, high-amplitude

signal that evolves in both frequency and space.

An aura is a stereotyped symptom set that immediately precedes the onset of a clinical

seizure and does not affect consciousness.

An aura is a stereotyped symptom set that immediately precedes the onset of a clinical

seizure and does not affect consciousness.

Physiologically, the aura is the true beginning of the seizure, and as such its

character can be quite useful for localizing seizure onset.

Physiologically, the aura is the true beginning of the seizure, and as such its

character can be quite useful for localizing seizure onset.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Etiologies of neonatal seizure:

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (35–42%)

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (35–42%)

Intracranial hemorrhage/infarction (15–20%)

Intracranial hemorrhage/infarction (15–20%)

CNS infection (12–17%)

CNS infection (12–17%)

Metabolic and inborn errors of metabolism (8–25%)

Metabolic and inborn errors of metabolism (8–25%)

CNS malformation (5%)

CNS malformation (5%)

A seizure prodrome is a set of symptoms, much less stereotyped than an aura, that

precedes a seizure by hours to days. Symptoms such as headache, mood changes, and

nausea are reported by over 50% of patients in some series.

A seizure prodrome is a set of symptoms, much less stereotyped than an aura, that

precedes a seizure by hours to days. Symptoms such as headache, mood changes, and

nausea are reported by over 50% of patients in some series.

TREATMENT

Therapy is directed at preventing the attacks.

Therapy is directed at preventing the attacks.

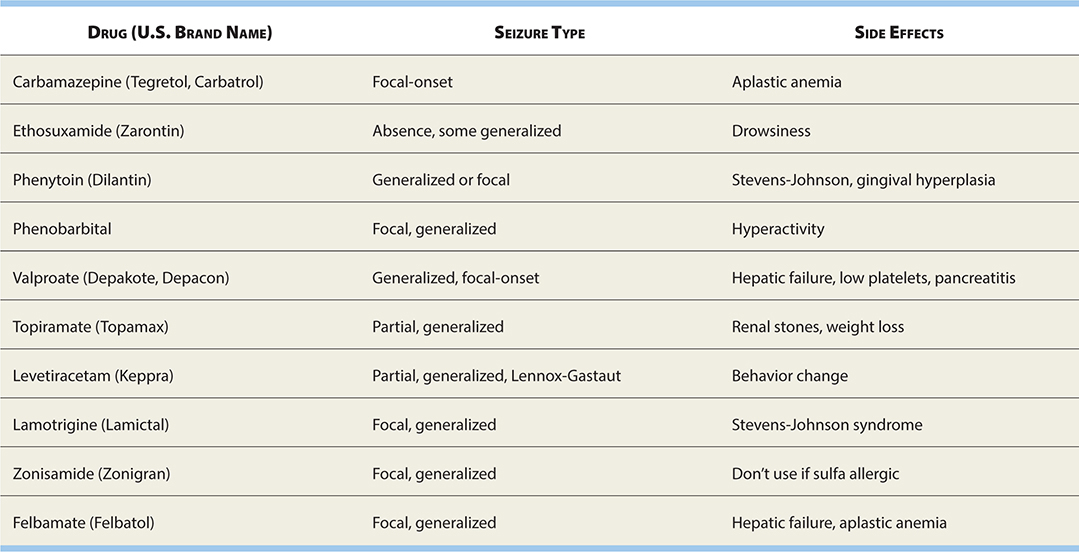

See Table 17-2 for current pharmacologic treatments for epilepsy.

See Table 17-2 for current pharmacologic treatments for epilepsy.

TABLE 17-2. Epilepsy Drugs and Their Use in Different Seizure Types

COMMON EPILEPSY SYNDROMES

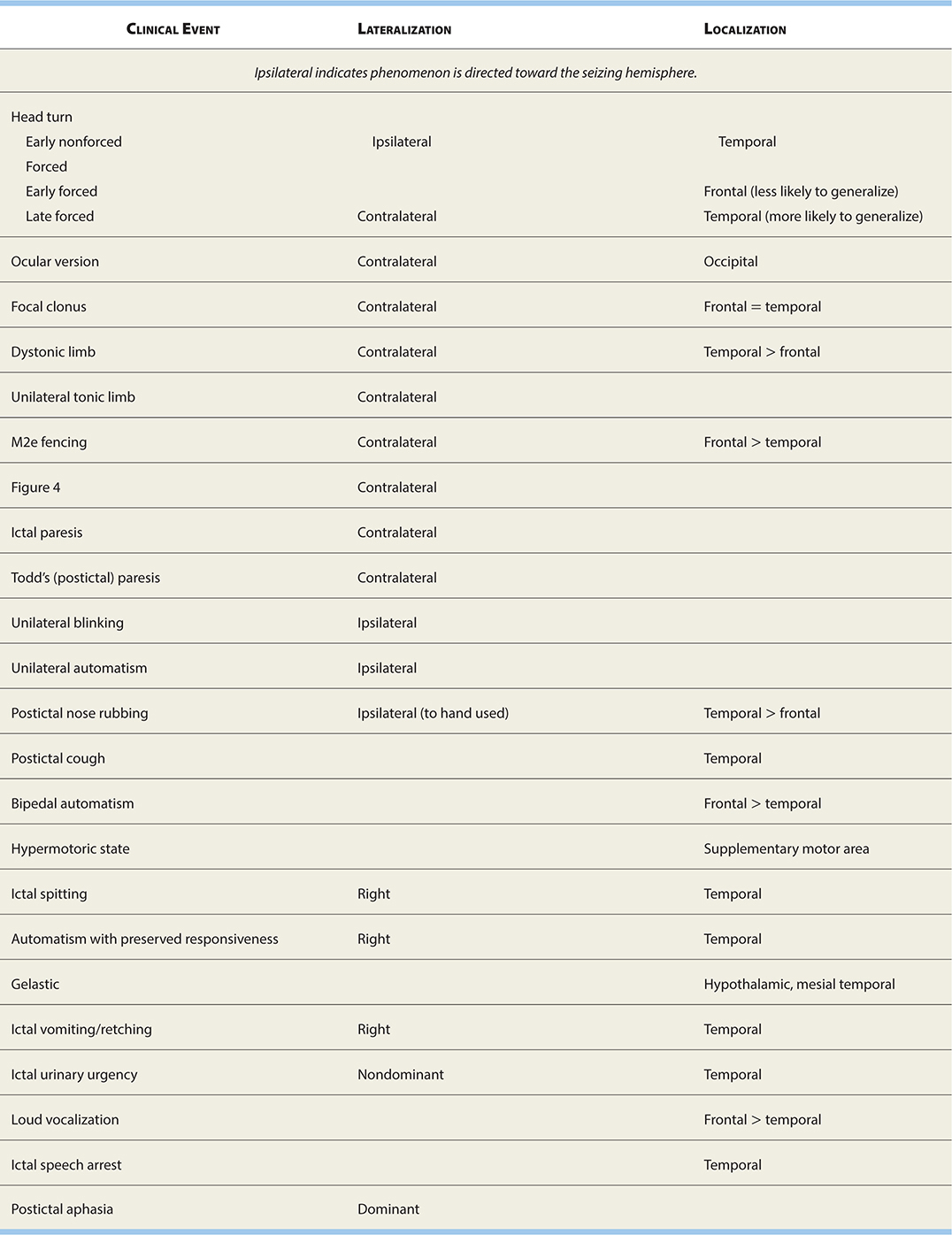

See Table 17-3 for localizing/lateralizing seizure semiologies.

TABLE 17-3. Localizing/Lateralizing Seizure Semiologies

Localization-Related Epilepsy

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Unprovoked seizure: Unrelated to current acute CNS insult such as infection, ↑ intracranial pressure (ICP), trauma, toxin, etc.

Seizures secondary to a focal CNS lesion, not necessarily visible on imaging, best

candidates for epilepsy surgery.

Seizures secondary to a focal CNS lesion, not necessarily visible on imaging, best

candidates for epilepsy surgery.

Common examples include masses (particularly cortical tubers of

Common examples include masses (particularly cortical tubers of

tuberous sclerosis [TS]), cortical dysplasia, postencephalitic gliosis, and arteriovenous

malformations (AVMs).

Benign Epilepsy with Centrotemporal spikes (BECTS)

A 5-year-old boy was noted to have facial twitching and facial drooling at a day

care center during a nap followed by generalized shaking of the body lasting 1–2 minutes.

The mother also reported noticing facial twitching during sleep. In the ED, he is

awake and his neurological examination is normal. You order an EEG, which shows centrotemporal

spikes. Think: BECTS formerly known as benign rolandic epilepsy.

A 5-year-old boy was noted to have facial twitching and facial drooling at a day

care center during a nap followed by generalized shaking of the body lasting 1–2 minutes.

The mother also reported noticing facial twitching during sleep. In the ED, he is

awake and his neurological examination is normal. You order an EEG, which shows centrotemporal

spikes. Think: BECTS formerly known as benign rolandic epilepsy.

BECTS is a partial epilepsy of childhood. The usual age of presentation is 3–13 years. Typical presentation: Seizure occurs during sleep (nighttime) with facial involvement. EEG shows central temporal spikes. Seizures typically resolve spontaneously by early adulthood.

Most common partial epilepsy.

Most common partial epilepsy.

Onset 3–13 years.

Onset 3–13 years.

Particularly nocturnal (early morning hours before awakening).

Particularly nocturnal (early morning hours before awakening).

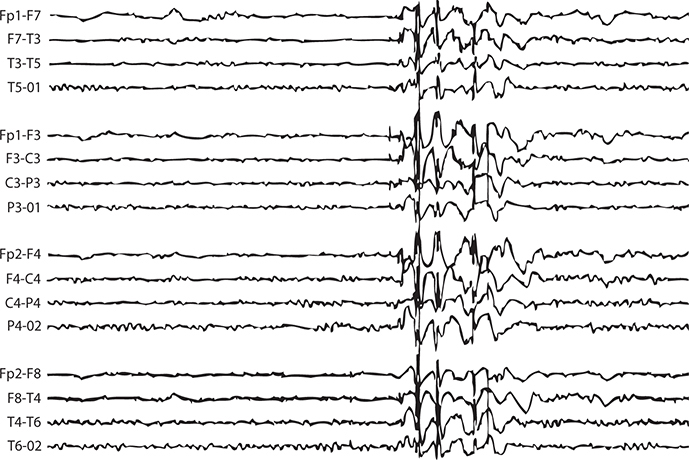

EEG: Central temporal spikes (Figure 17-3).

EEG: Central temporal spikes (Figure 17-3).

FIGURE 17-3. EEG demonstrating central temporal spikes characteristic of benign Rolandic epilepsy.

Excellent prognosis; most resolve by age 16 years.

Excellent prognosis; most resolve by age 16 years.

Treatment: Carbamazepine, phenytoin, and valproic acid.

Treatment: Carbamazepine, phenytoin, and valproic acid.

West Syndrome

Two percent of childhood epilepsies, but 25% of epilepsy with onset in the first

year of life.

Two percent of childhood epilepsies, but 25% of epilepsy with onset in the first

year of life.

Onset is at age 4–8 months.

Onset is at age 4–8 months.

Triad: Infantile spasms, mental retardation (MR), and hypsarrhythmia.

Triad: Infantile spasms, mental retardation (MR), and hypsarrhythmia.

Boys are more commonly affected but not significantly; generally poor prognosis.

Boys are more commonly affected but not significantly; generally poor prognosis.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Epilepsy History

Age, sex, handedness

Age, sex, handedness

Seizure semiology (what the seizures look like, details about right/left). If more

than one type, the pattern of progression (if any)

Seizure semiology (what the seizures look like, details about right/left). If more

than one type, the pattern of progression (if any)

Seizure duration/history of status epilepticus

Seizure duration/history of status epilepticus

Postictal lethargy or focal neurologic deficits

Postictal lethargy or focal neurologic deficits

Current frequency/tendency to cluster

Current frequency/tendency to cluster

Age at onset

Age at onset

Date of last seizure

Date of last seizure

Longest seizure-free interval

Longest seizure-free interval

Known precipitants (don’t forget to ask if the seizures typically arise out of

sleep)

Known precipitants (don’t forget to ask if the seizures typically arise out of

sleep)

History of head trauma, difficult birth, intrauterine infection, hypoxic/ischemic

insults, meningoencephalitis, or other CNS disease

History of head trauma, difficult birth, intrauterine infection, hypoxic/ischemic

insults, meningoencephalitis, or other CNS disease

Developmental history (delay strongly correlated with poorer prognosis)

Developmental history (delay strongly correlated with poorer prognosis)

Family history of epilepsy, febrile seizures

Family history of epilepsy, febrile seizures

Psychiatric history

Psychiatric history

Current AEDs

Current AEDs

AED history (maximum doses, efficacy, reason for stopping)

AED history (maximum doses, efficacy, reason for stopping)

Previous EEG, MRI findings

Previous EEG, MRI findings

Differential includes TS (largest group), CNS malformation, intrauterine infection,

inborn metabolic disorders, and idiopathic. Idiopathic group fares the best.

Differential includes TS (largest group), CNS malformation, intrauterine infection,

inborn metabolic disorders, and idiopathic. Idiopathic group fares the best.

Treatment in the United States is restricted to ACTH.

Treatment in the United States is restricted to ACTH.

Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy (JME)

Onset: 12–16 years.

Onset: 12–16 years.

Characteristic history: Usually early morning on awakening, while hair combing

and tooth brushing.

Characteristic history: Usually early morning on awakening, while hair combing

and tooth brushing.

Seizures: Myoclonus, absence, GTC.

Seizures: Myoclonus, absence, GTC.

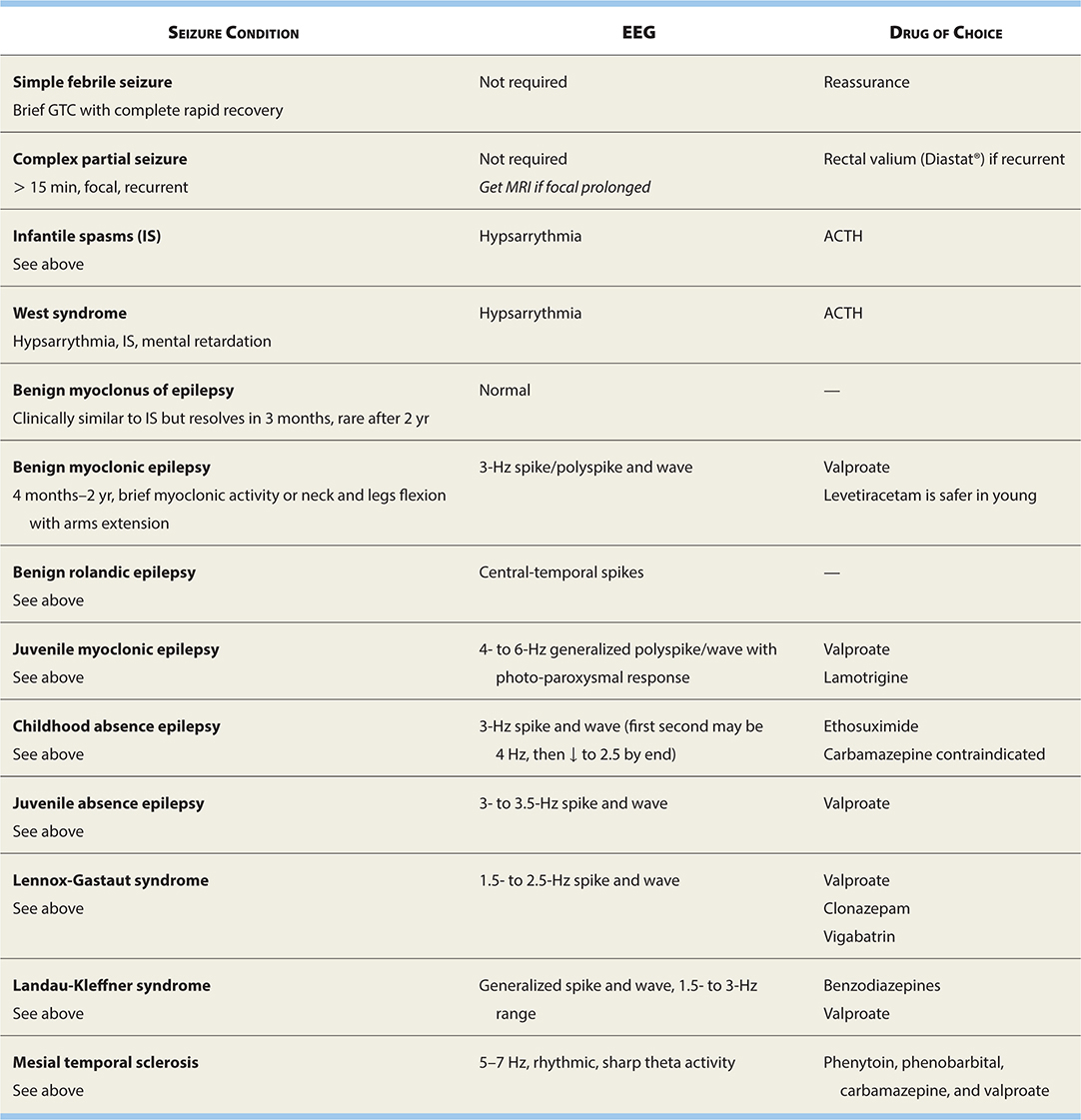

EEG: 4- to 6-Hz irregular spike-and-wave pattern (Figure 17-4 and Table 17-4).

EEG: 4- to 6-Hz irregular spike-and-wave pattern (Figure 17-4 and Table 17-4).

FIGURE 17-4. EEG demonstrating characteristic pattern of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy.

TABLE 17-4. Characteristic EEG Patterns in Various Seizure Conditions

Treatment: Valproate, lamotrigine.

Treatment: Valproate, lamotrigine.

Prognosis: Good Rx response but lifelong.

Prognosis: Good Rx response but lifelong.

High rate of recurrence if antiepileptic drug (AED) discontinued.

High rate of recurrence if antiepileptic drug (AED) discontinued.

Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE; Pyknolepsy)

See absence seizures above. GTC seizures often develop in adolescence; spontaneous

resolution is the rule, however.

See absence seizures above. GTC seizures often develop in adolescence; spontaneous

resolution is the rule, however.

Juvenile absence epilepsy (JAE): Similar to CAE except beginning in adolescence

and have more GTC seizures, sexes affected equally, EEG spike and wave often faster

than 3 Hz.

Juvenile absence epilepsy (JAE): Similar to CAE except beginning in adolescence

and have more GTC seizures, sexes affected equally, EEG spike and wave often faster

than 3 Hz.

Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome (LGS)

A generalized epilepsy syndrome.

A generalized epilepsy syndrome.

Multiple seizure types (tonic, atonic, absence, and myoclonic seizures).

Multiple seizure types (tonic, atonic, absence, and myoclonic seizures).

EEG: 1.5- to 2.5-Hz spike-and-wave pattern.

EEG: 1.5- to 2.5-Hz spike-and-wave pattern.

Cognitive impairment.

Cognitive impairment.

Infantile spasms may evolve to LGS (30%).

Infantile spasms may evolve to LGS (30%).

Seizures are frequent and resistant to treatment with AEDs.

Seizures are frequent and resistant to treatment with AEDs.

Landau-Kleffner Syndrome (LKS; Acquired Epileptic Aphasia)

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Loss of language skills in a previously normal child with seizure disorder. Think: LKS.

Language regression.

Language regression.

Aphasia (primarily receptive or expressive).

Aphasia (primarily receptive or expressive).

Seizures of several types (focal or GTC, atypical absence, partial complex).

Seizures of several types (focal or GTC, atypical absence, partial complex).

EEG: High-amplitude spike-and-wave discharges. Obtain EEG during sleep (more apparent

during non-rapid eye movement sleep).

EEG: High-amplitude spike-and-wave discharges. Obtain EEG during sleep (more apparent

during non-rapid eye movement sleep).

Differential diagnosis: Autism.

Differential diagnosis: Autism.

Treatment: Valproic acid.

Treatment: Valproic acid.

Progressive Myoclonic Epilepsies

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Evaluate patients following their first seizure (for mass, lesion, etc.) prior to diagnosing and treating epilepsy.

This group of diseases includes Unverricht-Lundborg disease, myoclonic epilepsy

with ragged-red fibers (MERRF), Lafora disease, neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, and

sialidosis/mucolipidosis, and Ramsay Hunt syndrome.

This group of diseases includes Unverricht-Lundborg disease, myoclonic epilepsy

with ragged-red fibers (MERRF), Lafora disease, neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, and

sialidosis/mucolipidosis, and Ramsay Hunt syndrome.

Begin in late childhood to adolescence, and entail progressive neurologic deterioration

with myoclonic seizures, dementia, and ataxia. Death within 10 years of onset is common,

but survival to old age occurs.

Begin in late childhood to adolescence, and entail progressive neurologic deterioration

with myoclonic seizures, dementia, and ataxia. Death within 10 years of onset is common,

but survival to old age occurs.

Mesial Temporal Sclerosis/Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

Gliotic scarring and atrophy of the hippocampal formation, creating a seizure focus.

Abnormality is often apparent on high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Gliotic scarring and atrophy of the hippocampal formation, creating a seizure focus.

Abnormality is often apparent on high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Rhythmic, 5–7 Hz, sharp theta activity.

Rhythmic, 5–7 Hz, sharp theta activity.

Phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, and valproate are equally effective. Curative

resection is often possible if refractory to treatment.

Phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, and valproate are equally effective. Curative

resection is often possible if refractory to treatment.

Rett Syndrome

DEFINITION

A neurodegenerative disorder of unknown cause.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

X-linked recessive with MECP2 gene mutation occurs almost exclusively in females. Rett syndrome does exist in males

with 47,XXY and MEP2 gene mutation. However, males with 46,XY and MECP2 gene mutation do not survive.

X-linked recessive with MECP2 gene mutation occurs almost exclusively in females. Rett syndrome does exist in males

with 47,XXY and MEP2 gene mutation. However, males with 46,XY and MECP2 gene mutation do not survive.

Prevalence: 1 in 15,000 to 1 in 22,000.

Prevalence: 1 in 15,000 to 1 in 22,000.

ETIOLOGY

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

The hallmark of Rett syndrome is repetitive hand-wringing and loss of purposeful and spontaneous hand movements.

Most cases result from defect in MECP2. Gene testing is available.

Most cases result from defect in MECP2. Gene testing is available.

CDKL5 gene mutations can also cause Rett syndrome.

CDKL5 gene mutations can also cause Rett syndrome.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Normal development until 12–18 months (can appear as early as 5 months).

Normal development until 12–18 months (can appear as early as 5 months).

The first signs are deceleration of head growth, lack of interest in environment,

and hypotonia, followed by a regression of language and motor milestones.

The first signs are deceleration of head growth, lack of interest in environment,

and hypotonia, followed by a regression of language and motor milestones.

Ataxia, hand-wringing, reduced brain weight, and episodes of hyperventilation are

typical.

Ataxia, hand-wringing, reduced brain weight, and episodes of hyperventilation are

typical.

Autistic behavior.

Autistic behavior.

PROGNOSIS

After the initial period of regression, the disease appears to plateau.

After the initial period of regression, the disease appears to plateau.

Death occurs during adolescence or the third decade of life (cardiac arrhythmias).

Death occurs during adolescence or the third decade of life (cardiac arrhythmias).

Status Epilepticus (SE)

DEFINITION

Any seizure or recurrent seizures without return to baseline lasting >20 minutes.

ETIOLOGY

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

In children under age 3, febrile seizures are the most likely etiology of status epilepticus.

Febrile seizures, idiopathic status epilepticus, and symptomatic SE.

Febrile seizures, idiopathic status epilepticus, and symptomatic SE.

Febrile SE accounts for 5% of febrile seizures and one-third of all episodes of

SE.

Febrile SE accounts for 5% of febrile seizures and one-third of all episodes of

SE.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Prolonged neural firing may result in neuronal cell death, called excitotoxicity.

TREATMENT

Initial treatment includes assessment of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems

(ABCs).

Initial treatment includes assessment of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems

(ABCs).

Obtain rapid bedside glucose level.

Obtain rapid bedside glucose level.

MANAGEMENT

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Neonatal status that is refractory to the usual measures may respond to pyridoxine. This is seen in pyridoxine dependency (due to diminished glutamate decarboxylase activity, a rare autosomal- recessive condition) or pyridoxine deficiency in children born to mothers on isoniazid.

Stabilization phase (0–5 minutes of seizure activity): Airway, breathing, circulation (ABCs); give O2; obtain IV acess, monitor vital signs, obtain rapid bedside glucose; obtain additional

labs and cultures as indicated.

Stabilization phase (0–5 minutes of seizure activity): Airway, breathing, circulation (ABCs); give O2; obtain IV acess, monitor vital signs, obtain rapid bedside glucose; obtain additional

labs and cultures as indicated.

Initial therapy phase (5–20 minutes of seizure activity): Administer a benzodiazepine (specifically IM

midazolam, lorazepam, or diazepam, OR Intranasal [IN] midazolam or buccal midazolam

if IV access not obtained). Benzodiazepines are recommended as the initial therapy

of choice, given its demonstrated efficacy, safety, and tolerability.

Initial therapy phase (5–20 minutes of seizure activity): Administer a benzodiazepine (specifically IM

midazolam, lorazepam, or diazepam, OR Intranasal [IN] midazolam or buccal midazolam

if IV access not obtained). Benzodiazepines are recommended as the initial therapy

of choice, given its demonstrated efficacy, safety, and tolerability.

Second therapy phase (20–40 minutes of seizure activity): If seizure continues, other options include

fosphenytoin, valproic acid, and levetiracetam. IV phenobarbital is an alternative

if none of the three recommended therapies are available, but can worsen respiratory

depression.

Second therapy phase (20–40 minutes of seizure activity): If seizure continues, other options include

fosphenytoin, valproic acid, and levetiracetam. IV phenobarbital is an alternative

if none of the three recommended therapies are available, but can worsen respiratory

depression.

Third therapy phase (40+ minutes of seizure activity): If seizure continues, treatment considerations

should include repeating second-line therapy or anesthetic doses of either thiopental,

midazolam, pentobarbital, or propofol (all with continuous EEG monitoring).

Third therapy phase (40+ minutes of seizure activity): If seizure continues, treatment considerations

should include repeating second-line therapy or anesthetic doses of either thiopental,

midazolam, pentobarbital, or propofol (all with continuous EEG monitoring).

Neuro-Cutaneous Syndromes

STURGE-WEBER SYNDROME

Dermato-oculo-neural syndrome.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Occurs sporadically in 1 in 50,000.

ETIOLOGY

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

If you see “port-wine stain,” think Sturge-Weber syndrome.

Abnormal development of the meningeal vasculature, resulting in hemispheric vascular

steal phenomenon and resultant hemiatrophy.

Abnormal development of the meningeal vasculature, resulting in hemispheric vascular

steal phenomenon and resultant hemiatrophy.

Facial capillary hemangioma usually accompanies in V1 distribution.

Facial capillary hemangioma usually accompanies in V1 distribution.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Cutaneous facial nevus flammeus (distribution of the trigeminal nerve) → port-wine

stain.

Cutaneous facial nevus flammeus (distribution of the trigeminal nerve) → port-wine

stain.

Ipsilateral diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the choroid → glaucoma.

Ipsilateral diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the choroid → glaucoma.

Ipsilateral meningeal hemangiomatosis (seizures and mental retardation).

Ipsilateral meningeal hemangiomatosis (seizures and mental retardation).

The lesions in the eye, skin, and brain are always present at birth.

The lesions in the eye, skin, and brain are always present at birth.

Contrast-enhanced MRI to look for meningeal angioma.

Contrast-enhanced MRI to look for meningeal angioma.

Seizures are usually refractory, and hemispherectomy improves the prognosis.

Seizures are usually refractory, and hemispherectomy improves the prognosis.

It is very unlikely to have meningeal involvement without port-wine stain, but

most children with a facial port-wine nevus do not have an intracranial angioma.

It is very unlikely to have meningeal involvement without port-wine stain, but

most children with a facial port-wine nevus do not have an intracranial angioma.

VON HIPPEL–LINDAU DISEASE

DEFINITION

A neurocutaneous syndrome (usually no cutaneous involment) affecting many organs, including the cerebellum, spinal cord, medulla, retina, kidneys, pancreas, and epididymis.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The major neurologic manifestations are:

Cerebellar/spinal hemagioblastomas: Present in early adult life with signs of ↑ ICP.

Cerebellar/spinal hemagioblastomas: Present in early adult life with signs of ↑ ICP.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Renal carcinoma is the most common cause of death associated with von Hippel–Lindau disease.

Retinal angiomata: Small masses of thin-walled capillaries in the peripheral retina.

Retinal angiomata: Small masses of thin-walled capillaries in the peripheral retina.

Multiple congenital cysts of the pancreas and polycythemia are also associated

with it.

Multiple congenital cysts of the pancreas and polycythemia are also associated

with it.

Early detection and resection is the best management.

Early detection and resection is the best management.

Photocoagulation for retinal detachment.

Photocoagulation for retinal detachment.

NEUROFIBROMATOSIS (NF)

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Both types display autosomal-recessive inheritance patterns.

Type 1: The most prevalent type (~90%) with an incidence of 1 in 4000 (chromosome 17).

Type 1: The most prevalent type (~90%) with an incidence of 1 in 4000 (chromosome 17).

Type 2: Accounts for 10% of all cases of NF, with an incidence of 1 in 40,000 (chromosome

22).

Type 2: Accounts for 10% of all cases of NF, with an incidence of 1 in 40,000 (chromosome

22).

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

About 50% of NF-1 results from new mutations. Parents should be carefully screened before counseling on the risk to future children.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Type 1

Diagnosis is made by the presence of two or more of the following:

Diagnosis is made by the presence of two or more of the following:

Six or more café-au-lait macules (must be >5 mm prepuberty, >15 mm postpuberty).

Six or more café-au-lait macules (must be >5 mm prepuberty, >15 mm postpuberty).

Axillary or inguinal freckling (Crowe sign).

Axillary or inguinal freckling (Crowe sign).

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

NF-1: Café-au-lait spots, childhood onset.

NF-2: Bilateral acoustic neuromas, teenage onset, multiple CNS tumors.

Two or more iris Lisch nodules (melanocytic hamartomas).

Two or more iris Lisch nodules (melanocytic hamartomas).

Two or more cutaneous neurofibromas.

Two or more cutaneous neurofibromas.

A characteristic osseous lesion (sphenoid dysplasia, thinning of long-bone cortex).

A characteristic osseous lesion (sphenoid dysplasia, thinning of long-bone cortex).

Optic glioma.

Optic glioma.

A first-degree relative with confirmed NF-1.

A first-degree relative with confirmed NF-1.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Café-au-lait is French for “coffee with milk,” which is the color of these lesions.

Learning disabilities, abnormal speech development, and seizures are common.

Learning disabilities, abnormal speech development, and seizures are common.

Patients are at a higher risk for other tumors of the CNS such as meningiomas and

astrocytomas (optic nerve gliomas in 20%) (but not as significantly as in NF-2).

Patients are at a higher risk for other tumors of the CNS such as meningiomas and

astrocytomas (optic nerve gliomas in 20%) (but not as significantly as in NF-2).

Risk of malignant transformation to neurofibrosarcoma is <5%.

Risk of malignant transformation to neurofibrosarcoma is <5%.

Type 2

Diagnosis is made when one of the following is present:

Diagnosis is made when one of the following is present:

Bilateral CN VIII masses (most of the cases).

Bilateral CN VIII masses (most of the cases).

A parent or sibling with the disease and either a neurofibroma, meningioma, glioma,

or schwannoma.

A parent or sibling with the disease and either a neurofibroma, meningioma, glioma,

or schwannoma.

Café-au-lait spots and skin neurofibromas are not common findings.

Café-au-lait spots and skin neurofibromas are not common findings.

Patients are at significantly higher risk for CNS tumors than in NF-1 and typically

have multiple tumors.

Patients are at significantly higher risk for CNS tumors than in NF-1 and typically

have multiple tumors.

TREATMENT

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Prenatal diagnosis and genetic confirmation of diagnosis are available in familial cases of both NF-1 and NF-2, but not new mutations.

Treatment is mainly aimed at preventing future complications and early detection of malignancies. Resection of the schwannomas can be done to preserve hearing.

TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait, with a frequency of 1:6,000.

Inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait, with a frequency of 1:6,000.

Two-thirds are new mutations.

Two-thirds are new mutations.

PATHOLOGY

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

In general, the younger that a child presents with signs and symptoms, the greater the likelihood of mental retardation.

Characteristic brain lesions consist of tubers, which are located in the convolutions

of the cerebrum, where they undergo calcification and project into the ventricles.

Characteristic brain lesions consist of tubers, which are located in the convolutions

of the cerebrum, where they undergo calcification and project into the ventricles.

There are two recognized genes: TSC1 on chromosome 9, encoding a protein called

hamartin; and TSC2 on chromosome 16, encoding a protein called tuberin.

There are two recognized genes: TSC1 on chromosome 9, encoding a protein called

hamartin; and TSC2 on chromosome 16, encoding a protein called tuberin.

Tubers may obstruct the foramen of Monro, → hydrocephalus.

Tubers may obstruct the foramen of Monro, → hydrocephalus.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Hypopigmented macules (Ash leaf skin lesions) are seen in 90% and are best viewed

under a Wood’s lamp (violet/ultraviolet light source).

Hypopigmented macules (Ash leaf skin lesions) are seen in 90% and are best viewed

under a Wood’s lamp (violet/ultraviolet light source).

CT scan shows calcified hamartomas (tubers) in the periventricular region.

CT scan shows calcified hamartomas (tubers) in the periventricular region.

Seizures and infantile spasms (IS) are common. Seizures usually present as IS before

age 1 and are difficult to control. Children develop autistic features and have developmental

disabilities and learning difficulties.

Seizures and infantile spasms (IS) are common. Seizures usually present as IS before

age 1 and are difficult to control. Children develop autistic features and have developmental

disabilities and learning difficulties.

Adenoma sebaceum—small, raised papules resembling acne that develop on the face

in butterfly pattern between 4 and 6 years of age, actually are small hamartomas.

Adenoma sebaceum—small, raised papules resembling acne that develop on the face

in butterfly pattern between 4 and 6 years of age, actually are small hamartomas.

A Shagreen patch (rough, raised, leathery lesion with an orange-peel consistency

in the lumbar region) is also a classic finding; typically does not develop until

adolescence.

A Shagreen patch (rough, raised, leathery lesion with an orange-peel consistency

in the lumbar region) is also a classic finding; typically does not develop until

adolescence.

Fifty percent of children also have rhabdomyomas of the heart, which may → CHF

or arrhythmias. They can be found on prenatal ultrasonography but usually regress

after birth.

Fifty percent of children also have rhabdomyomas of the heart, which may → CHF

or arrhythmias. They can be found on prenatal ultrasonography but usually regress

after birth.

Hamartomas of the kidneys and the lungs are also frequently present.

Hamartomas of the kidneys and the lungs are also frequently present.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Tuberous sclerosis is the most common cause of infantile spasms, an ominous seizure pattern in infants.

DIAGNOSIS

A high index of suspicion is needed, but all children presenting with infantile

spasms should be carefully assessed for skin and retinal lesions.

A high index of suspicion is needed, but all children presenting with infantile

spasms should be carefully assessed for skin and retinal lesions.

CT or MRI will confirm the diagnosis.

CT or MRI will confirm the diagnosis.

Genetic testing is available for mutations in TSC1 and TSC2.

Genetic testing is available for mutations in TSC1 and TSC2.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Hamartoma: A tumor-like overgrowth of tissue normally found in the area surrounding it.

SLEEP DISORDERS

Parasomnias

As a group, these disorders are:

As a group, these disorders are:

Paroxysmal.

Paroxysmal.

Predictable in their appearance in the sleep cycle.

Predictable in their appearance in the sleep cycle.

Nonresponsive to environmental manipulation .

Nonresponsive to environmental manipulation .

Characterized by retrograde amnesia.

Characterized by retrograde amnesia.

A thorough history makes the diagnosis and an extensive workup is rarely needed.

A thorough history makes the diagnosis and an extensive workup is rarely needed.

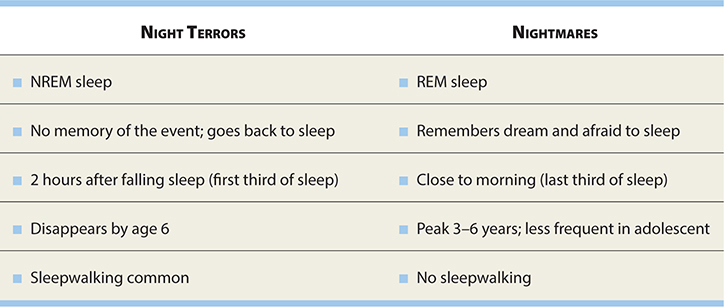

NIGHT TERRORS (PAVOR NOCTURNAS)

DEFINITION

Transient, sudden-onset episodes of terror in which the child cannot be consoled

and is unaware of the surroundings, usually lasting for 5–15 minutes.

Transient, sudden-onset episodes of terror in which the child cannot be consoled

and is unaware of the surroundings, usually lasting for 5–15 minutes.

There is total amnesia following the episodes.

There is total amnesia following the episodes.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Occur in 1–3% of the population, primarily in boys between ages 5 and 7.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Fifty percent complete recovery by age 8.

Fifty percent complete recovery by age 8.

Fifty percent are also sleepwalkers.

Fifty percent are also sleepwalkers.

Often, incontinence and diaphoresis.

Often, incontinence and diaphoresis.

Occur in stage 4 (deep) sleep, which is first third of night sleep.

Occur in stage 4 (deep) sleep, which is first third of night sleep.

DIAGNOSIS

PSG (polysomnography).

TREATMENT

Reassurance; usually self-limited and resolve by age 6.

SOMNAMBULANCE (SLEEPWALKING)

Occurs during slow-wave sleep.

Occurs during slow-wave sleep.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Night terrors, sleepwalking, and nightmares are associated with disturbed sleep, but have no known neurologic disorder.

Occurs during first third of the night.

Occurs during first third of the night.

Onset: 8–12 years.

Onset: 8–12 years.

Awakened only with difficulty and may be confused when awakened.

Awakened only with difficulty and may be confused when awakened.

Fifty percent also have night terrors.

Fifty percent also have night terrors.

INSOMNIA

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Sleep deprivation causes attention deficit, hyperactivity, and behavior disturbances in children—often mistaken for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Obstructive sleep apnea due to adenotonsillar hyperplasia is an indication for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy.

Affects 10–20% of adolescents.

Affects 10–20% of adolescents.

Depression is a common cause and should be ruled out.

Depression is a common cause and should be ruled out.

OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA (OSA)

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Since obstructive sleep apnea causes hypoxia, it may be associated with polycythemia vera, growth failure, and serious cardiorespiratory pathophysiology.

Occurs in 2–5 % of children, most often between ages 2 and 6.

Occurs in 2–5 % of children, most often between ages 2 and 6.

Characterized by chronic partial airway obstruction with intermittent episodes

of complete obstruction during sleep, resulting in disturbed sleep.

Characterized by chronic partial airway obstruction with intermittent episodes

of complete obstruction during sleep, resulting in disturbed sleep.

Snoring is the most common symptom, occurring in most of them (12% of general pediatric

population has snoring without OSA).

Snoring is the most common symptom, occurring in most of them (12% of general pediatric

population has snoring without OSA).

Symptoms: Fatigue/hyperactivity, headache, daytime somnolence.

Symptoms: Fatigue/hyperactivity, headache, daytime somnolence.

Signs: Narrow airway, tonsillar hypertrophy, often obese.

Signs: Narrow airway, tonsillar hypertrophy, often obese.

Diagnosis: History and physical examination, polysomnography (>1 apnea/hypopnea per hour).

Diagnosis: History and physical examination, polysomnography (>1 apnea/hypopnea per hour).

Coma

Consciousness refers to the state of awareness of self and environment.

Consciousness refers to the state of awareness of self and environment.

Pediatric evaluation of consciousness is dependent on both age and developmental

level.

Pediatric evaluation of consciousness is dependent on both age and developmental

level.

DEFINITION

Pathologic cause of loss of normal consciousness.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Consciousness is the result of communication between the cerebral cortex and the

ascending reticular-activating system.

Consciousness is the result of communication between the cerebral cortex and the

ascending reticular-activating system.

Coma can be caused by:

Coma can be caused by:

Lesions of the medullary reticular-activating system or its ascending projections.

Ventral pontine lesions → locked-in syndrome, which is not coma.

Lesions of the medullary reticular-activating system or its ascending projections.

Ventral pontine lesions → locked-in syndrome, which is not coma.

ETIOLOGY

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Herniation is a result of increased intracranial pressure and often leads to coma or death.

Herniation syndromes that may result in coma:

Uncal herniation: Pressure on CN 6 with diploplia and inability to abduct eye

Uncal herniation: Pressure on CN 6 with diploplia and inability to abduct eye

Central (trans-tentorial herniation): Blown (fixed and dilated) pupil, ptosis, CN 3 compression (down and out eye), ipsilateral

hemiplegia

Central (trans-tentorial herniation): Blown (fixed and dilated) pupil, ptosis, CN 3 compression (down and out eye), ipsilateral

hemiplegia

Structural causes include trauma, vascular conditions, and mass lesions involving

directly or mass effects.

Structural causes include trauma, vascular conditions, and mass lesions involving

directly or mass effects.

Metabolic and toxic causes include hypoxic-ischemic injury, toxins, infectious

causes, and seizures.

Metabolic and toxic causes include hypoxic-ischemic injury, toxins, infectious

causes, and seizures.

EVALUATION

Administer glucose via IV line so that the brain has an adequate energy supply.

Administer glucose via IV line so that the brain has an adequate energy supply.

Treat underlying cause (toxin antidote, reduce ICP, antibiotics, etc.).

Treat underlying cause (toxin antidote, reduce ICP, antibiotics, etc.).

PROGNOSIS

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Prognosis depends on the etiology of the insult and the rapid initiation of treatment!

Overall, children tend to do better than adults.

Overall, children tend to do better than adults.

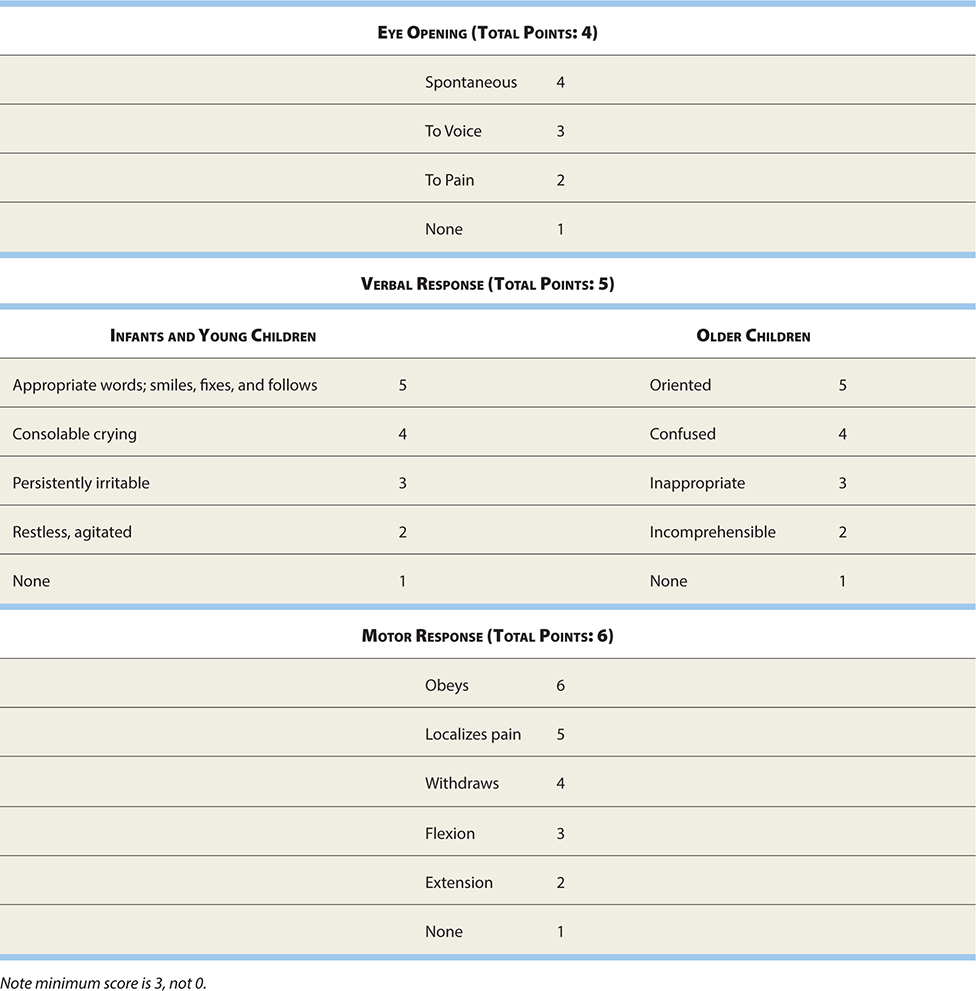

Several measurement scales have been published attempting to predict outcome. The

most widely accepted is the Glasgow Coma Scale (see Table 17-5).

Several measurement scales have been published attempting to predict outcome. The

most widely accepted is the Glasgow Coma Scale (see Table 17-5).

TABLE 17-5. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)

Another scale that you should know exists is the Pediatric Cerebral Performance

Category Scale, which, unlike the Glasgow, was specifically designed for pediatric

patients.

Another scale that you should know exists is the Pediatric Cerebral Performance

Category Scale, which, unlike the Glasgow, was specifically designed for pediatric

patients.

ENCEPHALOPATHIES

CNS Infection

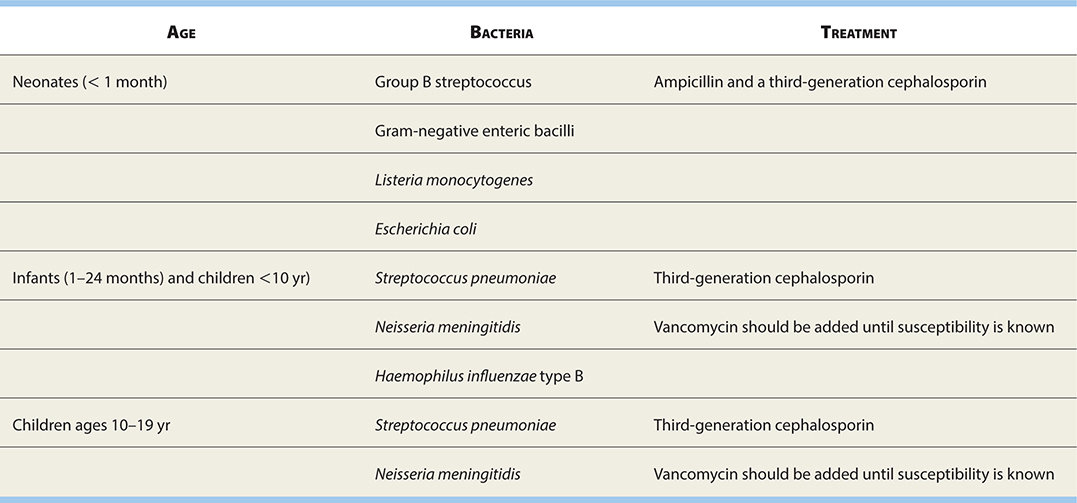

MENINGITIS

DEFINITION

Diffuse inflammation of the meninges, particularly arachnoids and pia mater.

Diffuse inflammation of the meninges, particularly arachnoids and pia mater.

Bacteria:

Bacteria:

<3 months: Group B streptococci and gram-negative organisms, Escherichia coli, Listeria.

<3 months: Group B streptococci and gram-negative organisms, Escherichia coli, Listeria.

>3 months: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and Neisseria meningitidis (two life-threatening clinical syndromes: meningococcemia and meningococcal meningitis).

>3 months: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and Neisseria meningitidis (two life-threatening clinical syndromes: meningococcemia and meningococcal meningitis).

Virus: The term aseptic meningitis is used to describe the syndrome of meningism and CSF leukocytosis usually caused

by viruses or bacteria.

Virus: The term aseptic meningitis is used to describe the syndrome of meningism and CSF leukocytosis usually caused

by viruses or bacteria.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

If immunocompromised, these signs and symptoms will be not prominent.

Fever, headache, and nuchal rigidity (most important features).

Fever, headache, and nuchal rigidity (most important features).

Photophobia or myalgia may be present.

Photophobia or myalgia may be present.

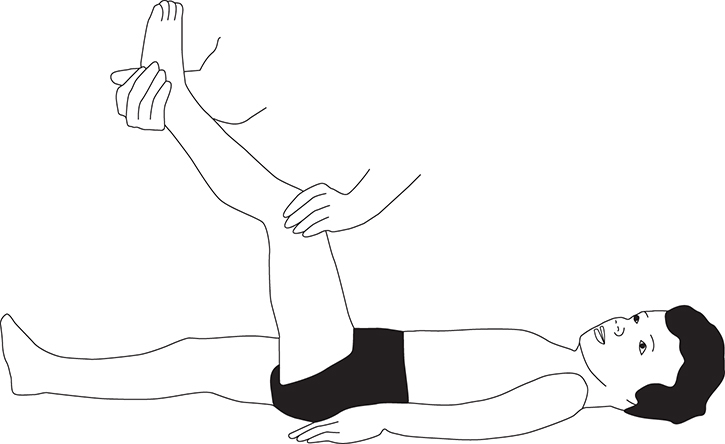

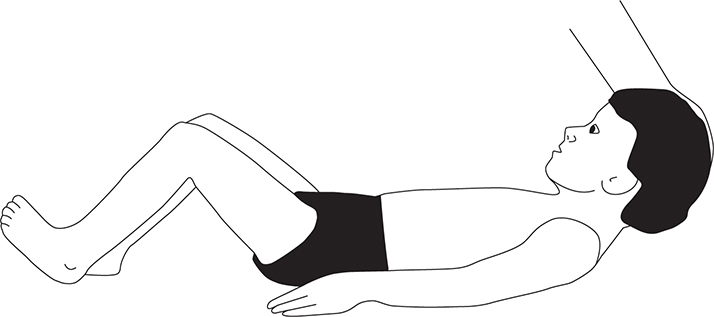

Meningism (Brudzinski and Kernig signs) (see Figures 17-5 and 17-6).

Meningism (Brudzinski and Kernig signs) (see Figures 17-5 and 17-6).

FIGURE 17-5. Kernig sign. Flex patient’s leg at both hip and knee, and then straighten knee. Pain on extension is a positive sign.

FIGURE 17-6. Brudzinski sign. Involuntary flexion of the hips and knees with passive flexion of the neck while supine.

Altered consciousness, petechial rash, seizures, cranial nerve, or other abnormal

neurological findings.

Altered consciousness, petechial rash, seizures, cranial nerve, or other abnormal

neurological findings.

DIAGNOSIS

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Take some time to familiarize yourself with Tables 17-6 and 17-7: You will be asked this!

TABLE 17-6. Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Findings in Meningitis

TABLE 17-7. Common Causes of Pediatric Bacterial Meningitis

Analysis of the CSF is not always predictive of viral or bacterial infection since there is considerable overlap in the respective CSF findings, especially at the onset of the disease (Table 17-6).

Bacterial Meningitis

See Table 17-7 for common meningitis-causing bacteria.

See Table 17-7 for common meningitis-causing bacteria.

Associated with high rate of complications and chronic morbidity and death.

Associated with high rate of complications and chronic morbidity and death.

Pathogenesis: 95% blood-borne. Organism enters the CSF, multiplies, and stimulates

an inflammatory response. Direct toxin from organism, hypotension, or vasculitis →

thrombotic event; vasogenic/cytotoxic edema causes ↑ ICP and ↓ blood flow, which all

may contribute to further damage.

Pathogenesis: 95% blood-borne. Organism enters the CSF, multiplies, and stimulates

an inflammatory response. Direct toxin from organism, hypotension, or vasculitis →

thrombotic event; vasogenic/cytotoxic edema causes ↑ ICP and ↓ blood flow, which all

may contribute to further damage.

Viral Meningitis

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Chronic meningitis: Subacute symptoms of meningitis for >4 weeks: Infectious, autoimmune, or neoplastic.

Enterovirus (85%): Echovirus, coxsackievirus, and nonparalytic poliovirus.

Enterovirus (85%): Echovirus, coxsackievirus, and nonparalytic poliovirus.

Other classic causes are herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), Epstein-Barr virus

(EBV), mumps, influenza, arboviruses, and adenoviruses.

Other classic causes are herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), Epstein-Barr virus

(EBV), mumps, influenza, arboviruses, and adenoviruses.

Clinical presentation is similar but symptoms usually are less severe than that

of bacterial meningitis.

Clinical presentation is similar but symptoms usually are less severe than that

of bacterial meningitis.

Children may not be toxic appearing.

Children may not be toxic appearing.

Children show typical viral-type infectious signs (fever, malaise, myalgia, nausea,

and rash) as well as meningeal signs.

Children show typical viral-type infectious signs (fever, malaise, myalgia, nausea,

and rash) as well as meningeal signs.

Typically is a self-limited process with complete recovery, and treatment is supportive.

Typically is a self-limited process with complete recovery, and treatment is supportive.

Fungal Meningitis

Although relatively uncommon, the classic organism is Cryptococcus.

Although relatively uncommon, the classic organism is Cryptococcus.

Encountered primarily in the immunocompromised patient (with transplants, AIDS,

or on chemotherapy).

Encountered primarily in the immunocompromised patient (with transplants, AIDS,

or on chemotherapy).

May be rapidly fatal (as quickly as 2 weeks) or evolve over months to years.

May be rapidly fatal (as quickly as 2 weeks) or evolve over months to years.

Tends to cause direct lymphatic obstruction, → hydrocephalus.

Tends to cause direct lymphatic obstruction, → hydrocephalus.

TREATMENT

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Nuchal rigidity. Think: Meningitis.

Third-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime/ceftriaxone).

Third-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime/ceftriaxone).

Add ampicillin for Listeria in neonates. Neonates can be treated with ampicillin + gentamicin or ampicillin +

cefotaxime.

Add ampicillin for Listeria in neonates. Neonates can be treated with ampicillin + gentamicin or ampicillin +

cefotaxime.

Add vancomycin, considering the increasing resistance of pneumococci to cephalosporins

and carbapenems until the sensitivities are known.

Add vancomycin, considering the increasing resistance of pneumococci to cephalosporins

and carbapenems until the sensitivities are known.

If viral etiology is suspected or CSF is not clearly differentiating between bacterial

and viral etiologies, consider adding acyclovir until viral polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) comes back negative.

If viral etiology is suspected or CSF is not clearly differentiating between bacterial

and viral etiologies, consider adding acyclovir until viral polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) comes back negative.

Steroid use is controversial.

Steroid use is controversial.

Encephalitis

DEFINITION

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Congenital syphilis may manifest around age 2 with Hutchinson’s triad:

Interstitial keratitis

Interstitial keratitis

Peg-shaped incisors

Peg-shaped incisors

Deafness (cranial nerve [CN] VIII)

Deafness (cranial nerve [CN] VIII)

A disease process in the brain primarily affecting the brain parenchyma.

A disease process in the brain primarily affecting the brain parenchyma.

Because patients often have symptoms of both meningitis and encephalitis, the term

meningoencephalitis is often applied.

Because patients often have symptoms of both meningitis and encephalitis, the term

meningoencephalitis is often applied.

ETIOLOGY

Chronic Bacterial Meningoencephalitis

1. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. bovis, and M. avium-intracellulare.

Nonspecific features develop over days to weeks. Patients have generalized complaints

of headache, malaise, and weight loss initially.

Nonspecific features develop over days to weeks. Patients have generalized complaints

of headache, malaise, and weight loss initially.

This is followed by confusion, focal neurological signs, cranial nerve palsies,

and seizures or, in advanced cases, hemiparesis, hemiplegia, or coma.

This is followed by confusion, focal neurological signs, cranial nerve palsies,

and seizures or, in advanced cases, hemiparesis, hemiplegia, or coma.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Argyll Robertson pupil is discrepancy in pupil size seen in neurosyphilis.

Serious complications include arachnoid fibrosis, → hydrocephalus, and arterial

occlusion, → infarcts.

Serious complications include arachnoid fibrosis, → hydrocephalus, and arterial

occlusion, → infarcts.

M. avium-intracellulare is common in AIDS patients.

M. avium-intracellulare is common in AIDS patients.

2. Neurosyphilis (tabes dorsalis).

Causative organism is Treponema pallidum.

Causative organism is Treponema pallidum.

May present with aseptic meningitis only.

May present with aseptic meningitis only.

Tertiary syphilis (late-stage syphilis) manifests with neurologic, cardiovascular,

and granulomatous lesions.

Tertiary syphilis (late-stage syphilis) manifests with neurologic, cardiovascular,

and granulomatous lesions.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

The transmission rate of syphilis from infected mother to infant is nearly 100%. Treat infant with IV penicillin G.

Congenital syphilis presents with a maculopapular rash, lymphadenopathy, and mucopurulent

rhinitis.

Congenital syphilis presents with a maculopapular rash, lymphadenopathy, and mucopurulent

rhinitis.

Routine prenatal screening for syphilis is now mandatory in most states to prevent

congenital syphilis.

Routine prenatal screening for syphilis is now mandatory in most states to prevent

congenital syphilis.

Viral Meningoencephalitis

1. Herpes simplex virus:

HSV-1: Most cases after the neonatal period.

HSV-1: Most cases after the neonatal period.

HSV-2: Usually blood-borne and results in diffuse meningoencephalitis and other

organ involvement. It is the congenitally acquired form, transmitted to 50% of babies

born to a mother with active vaginal lesions.

HSV-2: Usually blood-borne and results in diffuse meningoencephalitis and other

organ involvement. It is the congenitally acquired form, transmitted to 50% of babies

born to a mother with active vaginal lesions.

2. Herpes zoster virus:

Can occur after primary infection or as a result of reactivation later in life.

Can occur after primary infection or as a result of reactivation later in life.

Usually with a rash, but outcome is poor in those without a rash.

Usually with a rash, but outcome is poor in those without a rash.

In immunocompetent hosts, after 2–6 months of primary infection, the dormant virus

in the ganglia becomes activated in and causes large-vessel vasculitis → infarcts.

In immunocompetent hosts, after 2–6 months of primary infection, the dormant virus

in the ganglia becomes activated in and causes large-vessel vasculitis → infarcts.

In immunocompromised hosts, the dormant virus causes small-vessel vasculitis and

results in hemorrhagic infarcts of gray and white matter.

In immunocompromised hosts, the dormant virus causes small-vessel vasculitis and

results in hemorrhagic infarcts of gray and white matter.

EEG will show diffuse slowing and periodic lateralizing epileptiform discharges

(PLEDs).

EEG will show diffuse slowing and periodic lateralizing epileptiform discharges

(PLEDs).

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Acyclovir is the treatment of choice for herpetic meningitis.

3. Rabies:

Causes severe encephalitis, coma, and death due to respiratory failure.

Causes severe encephalitis, coma, and death due to respiratory failure.

Transmitted via bite or saliva from an infected animal, usually associated with

dogs, bats, skunks, raccoons, or squirrels.

Transmitted via bite or saliva from an infected animal, usually associated with

dogs, bats, skunks, raccoons, or squirrels.

The virus travels up the peripheral nerves from the bite site and enters the brain.

The virus travels up the peripheral nerves from the bite site and enters the brain.

Nonspecific symptoms (fever, malaise) and paresthesia around the bite site are

pathognomonic. This is followed by more specific neurologic symptoms of hydrophobia,

aerophobia, agitation, hypersalivation, and seizures. This proceeds to coma and death.

Nonspecific symptoms (fever, malaise) and paresthesia around the bite site are

pathognomonic. This is followed by more specific neurologic symptoms of hydrophobia,

aerophobia, agitation, hypersalivation, and seizures. This proceeds to coma and death.

Prophylaxis is indicated when there is potential exposure with rabies immunoglobulin

and rabies vaccine (multiple doses).

Prophylaxis is indicated when there is potential exposure with rabies immunoglobulin

and rabies vaccine (multiple doses).

Transverse Myelitis

DEFINITION

An acute focal infectious or immune-mediated illness causing swelling and demyelination

of the spinal cord. This most commonly affects the thoracic spinal cord (80%) followed

by cervical cord.

An acute focal infectious or immune-mediated illness causing swelling and demyelination

of the spinal cord. This most commonly affects the thoracic spinal cord (80%) followed

by cervical cord.

It is a neurological emergency and requires prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent

permanent damage.

It is a neurological emergency and requires prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent

permanent damage.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Fever, lethargy, malaise, muscle pains.

Fever, lethargy, malaise, muscle pains.

Begins acutely and progresses within 1–2 days.

Begins acutely and progresses within 1–2 days.

Back pain at the level of the involved cord and paresthesias of the legs are common.

Back pain at the level of the involved cord and paresthesias of the legs are common.

Anterior horn involvement may cause lower motor neuron dysfunction.

Anterior horn involvement may cause lower motor neuron dysfunction.

Bladder and bowel dysfunction is present.

Bladder and bowel dysfunction is present.

DIAGNOSIS

MRI: Enhanced T2 signals.

MRI: Enhanced T2 signals.

EXAM TIP

EXAM TIP

Numerous viruses as well as the rabies vaccination and smallpox vaccination have been linked to transverse myelitis.

CSF: Pleocytosis.

CSF: Pleocytosis.

Electromyogram (EMG): Anterior horn-cell dysfunction in involved segments.

Electromyogram (EMG): Anterior horn-cell dysfunction in involved segments.

TREATMENT

IV steroids, intravenous immune globulin (IVIG), may require surgical intervention.

PROGNOSIS

Most make good recovery; however, it is slow.

Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

DEFINITION

An immune-mediated demyelinating encephalopathy in which there is a sudden widespread

attack of the inflammation of the brain, spinal cord, and nerves, with destruction

of white matter.

An immune-mediated demyelinating encephalopathy in which there is a sudden widespread

attack of the inflammation of the brain, spinal cord, and nerves, with destruction

of white matter.

Two-thirds with history of an antecedent viral infection.

Two-thirds with history of an antecedent viral infection.

Some features resemble multiple sclerosis.

Some features resemble multiple sclerosis.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Abrupt onset of change in consciousness or behavior changes unexplained by fever.

Abrupt onset of change in consciousness or behavior changes unexplained by fever.

Often associated with at least one fever free day before onset of symptoms.

Often associated with at least one fever free day before onset of symptoms.

Irritability and lethargy are common first signs of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis.

Irritability and lethargy are common first signs of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis.

Fever returns and headache are present in up to half of the cases. Meningismus

is also detected in approximately one-third of the cases. Over the course of minutes

to weeks, multifocal neurologic abnormalities develop which can include weakness,

ataxia, and cranial nerve abnormalities.

Fever returns and headache are present in up to half of the cases. Meningismus

is also detected in approximately one-third of the cases. Over the course of minutes

to weeks, multifocal neurologic abnormalities develop which can include weakness,

ataxia, and cranial nerve abnormalities.

DIAGNOSIS

MRI: ADEM lesions are characteristically multiple, bilateral but asymmetric, and widespread within the CNS.

TREATMENT

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

ADEM is associated with bilateral optic neuritis and MS is usually unilateral.

First-line high-dose IV steroids, also intravenous immune globulin (IVIG).

PROGNOSIS

2–10% mortality but most recover completely or with mild sequelae.

Tetanus

A 1-week-old child born to an immunocompromised mother presents with difficulty feeding,

trismus, and other rigid muscles. Think: Tetanus.

A 1-week-old child born to an immunocompromised mother presents with difficulty feeding,

trismus, and other rigid muscles. Think: Tetanus.

Tetanus is a toxin-mediated disease characterized by severe skeletal muscle spasms. It is a serious infection in neonatal life. Initial symptoms can be nonspecific. Inability to suck and difficulty in swallowing are important clinical features followed by stiffness and seizures. Neonatal tetanus can be prevented by immunizing mothers before or during pregnancy and providing sterile care throughout the delivery.

DEFINITION

An acute illness with painful muscle spasms and hypertonia caused by the neurotoxin

produced by Clostridium tetani.

An acute illness with painful muscle spasms and hypertonia caused by the neurotoxin

produced by Clostridium tetani.

These symptoms usually start in the jaw and facial muscles and progressively involve

other muscle groups.

These symptoms usually start in the jaw and facial muscles and progressively involve

other muscle groups.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Trismus (masseter muscle spasm) is the characteristic sign and is present in 75%

of cases.

Trismus (masseter muscle spasm) is the characteristic sign and is present in 75%

of cases.

Risus sardonicus, a grin caused by facial spasm, is also classic.

Risus sardonicus, a grin caused by facial spasm, is also classic.

Dysphagia due to pharyngeal spasm develops over a few days; laryngo-spasm may result

in asphyxia.

Dysphagia due to pharyngeal spasm develops over a few days; laryngo-spasm may result

in asphyxia.

Descending paralysis and when involves the trunk and thigh, the patient may exhibit

an arched posture in which only the head and heels touch the ground.

Descending paralysis and when involves the trunk and thigh, the patient may exhibit

an arched posture in which only the head and heels touch the ground.

Late stages manifest with recurrent seizures consisting of sudden severe tonic

contractions of the muscles with fist clenching, flexion, and adduction of the upper

limb and extension of the lower limb and is associated with poor prognosis.

Late stages manifest with recurrent seizures consisting of sudden severe tonic

contractions of the muscles with fist clenching, flexion, and adduction of the upper

limb and extension of the lower limb and is associated with poor prognosis.

Autonomic dysfunction may be seen as ↑ sweating, heart rate, blood pressure, and

temperature.

Autonomic dysfunction may be seen as ↑ sweating, heart rate, blood pressure, and

temperature.

Can also present with localized spasms at the site of infection or with abdominal

pain mimicking acute abdomen.

Can also present with localized spasms at the site of infection or with abdominal

pain mimicking acute abdomen.

Incubation period varies from 2 to 14 days (average 7 days).

Incubation period varies from 2 to 14 days (average 7 days).

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is clinical: Trismus, dysphagia, ↑ rigidity, and muscle spasms.

Diagnosis is clinical: Trismus, dysphagia, ↑ rigidity, and muscle spasms.

Laboratory studies are usually normal, but a moderate leukocytosis may be present.

Laboratory studies are usually normal, but a moderate leukocytosis may be present.

CSF is normal.

CSF is normal.

Gram stain is positive in only one-third of the cases.

Gram stain is positive in only one-third of the cases.

TREATMENT

Prophylactic intubation.

Prophylactic intubation.

WARD TIP

WARD TIP

Tetanic contractions can be triggered by minor stimuli, such as a flashing light. Patients should be sedated, intubated, and put in a dark room in severe cases.

Rapid administration of human tetanus immune globulin.

Rapid administration of human tetanus immune globulin.