A distinguished student of William Shakespeare introduces our poem in this way:

“The Phoenix and Turtle” first appeared in a collection of poems called Love’s Martyr: Or, Rosalins Complaint by Robert Chester (1601). This quarto volume offered various poetic exercises about the phoenix and the turtle “by the best and chieftest of our modern writers.” The poem assigned to Shakespeare has been universally accepted as his and is one of his most remarkable productions.1

It is suggested in what follows how remarkable this production is:

With a deceptively simple diction, in gracefully pure tetrameter quatrains and triplets, the poem effortlessly evokes the transcendental ideal of a love existing eternally beyond death. The occasion is an assembly of birds to observe the funeral rites of the phoenix (always found alone) and the turtledove (always found in pairs). The phoenix, legendary bird of resurrection from its own ashes, once more finds life through death in the company of the turtledove, emblem of pure constancy in affection. Their spiritual union becomes a mystical oneness in whose presence Reason stands virtually speechless. Baffled human discourse must resort to paradox in order to explain how two beings become one essence, “Hearts remote yet not asunder.” Mathematics and logic are “confounded” by this joining of two spirits into a “concordant one.”

This introduction to the poem concludes with suggestions about its theological content and literary context:

This paradox of oneness echoes scholastic theology and its expounding of the doctrine of the Trinity, in terms of persons, substance, accident, triunity, and the like, although, somewhat in the manner of John Donne’s poetry, this allusion is more a part of the poem’s serious wit than its symbolic meaning. The poignant brevity of this vision is rendered all the more mysterious by our not knowing what, if any, human tragedy may have prompted this metaphysical affirmation.

This poem has been identified here as made of “gracefully pure tetrameter quatrains and triplets.” There are thirteen quatrains. These are followed by the five triplets identified as “Threnos” which Professor David Bevington explains as “lamentation, funeral song” (from the ancient Greek, threnos).2

The account of the traditional Phoenix in a standard reference work can make us wonder whether it could have ever properly been considered a “dead” bird (67):

Phoenix—a fabulous bird connected with the worship of the sun especially in ancient Egypt and in classical antiquity. It was known to Hesiod, and descriptions of its appearance and behaviour occur in ancient literature sporadically, with variations in detail, from Herodotus’ account of Egypt onward. The phoenix is said to be as large as an eagle, with brilliant scarlet and gold plumage and a melodious cry. Only one phoenix exists at any time. It is very long-lived; no ancient authority gives it a life span of less than 500 years; some say it lives for 1,461 years (an Egyptian Sothic Period); an extreme estimate is 97,000. As its end approaches the phoenix fashions a nest of aromatic boughs and spices, sets it on fire, and is consumed in the flames. From this pyre miraculously springs a new phoenix which, after embalming its [predecessor’s] ashes in an egg of myrrh, flies with them [that is, the ashes] to Heliopolis in Egypt where it deposits them on the altar in the Temple of the Sun.3

This account continues with these recollections of the Phoenix legend: “Clearly the country of the phoenix, its miraculous rebirth, its connection with fire, and other features of its story are symbolical of the sun itself, with its promise of dawn after sunset, and of new life after death.” This account concludes with what has been done with the Phoenix in the West:

[T]he Egyptians associated the phoenix with intimations of immortality, and this symbolism had a widespread appeal in late antiquity. The Latin poet Martial compared the phoenix to undying Rome, and it appears on the coinage of the Roman Empire as a symbol of the Eternal City. It is also widely interpreted as an allegory of resurrection and life after death. These were ideas which appealed to emergent Christianity; Church Fathers…used the phoenix as an illustration of Christian doctrine concerning the raising of the dead and eternal life.

The career of the Turtledove across millennia is far less spectacular than that of the Phoenix. But it, unlike the Phoenix, is sanctified by its appearance in the Bible. Thus, the “Turtle and Turtledove” entry in one dictionary of biblical terms opens with this description:

A species of pigeon. It is gentle and harmless, fit emblem of a defenseless and innocent people (Psalms 74:19). It is migratory (Jeremiah 8:7), and a herald of spring (Song of Solomon 2:12).4

But however “gentle and harmless” the turtledove may be, it could evidently be dealt with mercilessly. The entry continues thus: “Abraham sacrificed a turtledove and other victims when the Lord’s covenant was made with him (Genesis 15:9).” Perhaps this sacrifice anticipated what was attempted later by Abraham with the somewhat hapless (“gentle and harmless”?) Isaac.

“Under the law,” we are further told, the turtledove

served as a burnt offering (Leviticus 1:14) and for a sin offering; and two turtle-doves were prescribed for these two sacrifices in case a poor person was obliged to make a guilt offering, and for the purification of a woman after childbirth if she was poor, of a man or woman with an issue, and of a Nazirite (Leviticus 5:7, 11; 12:6, 8; 14:22, 30; 15:14, 29, 30; Numbers 6:10, 11). [The turtledove] was readily obtainable by the poor, for it abounds in Palestine and is easily trapped.

These, then, are the kinds of things long said about the Phoenix and the Turtledove and evidently were routinely available to Shakespeare and his contemporaries. How, then, might our most celebrated poem by Shakespeare about “these dead birds” (67) be understood?

Learned scholars seem to believe that Shakespeare considered his poetry more enduring, if not also more significant, than his plays. Efforts were evidently made by him to assure that his poems would be circulated among the more influential (as well as the more learned) readers of his day. His plays, on the other hand, seem to have been collected in print only by others.

Speculation abounds as to what personalities, and perhaps what events, are alluded to, if not even commented on, in The Phoenix and Turtle. But Shakespeare should have known that this poem might be read someday by thoughtful men and women who either would not know or would not much care about the “personalities” or events originally drawn on for its composition. How then would the poem have been intended by Shakespeare to be understood by such readers, especially by the more astute among them?

Indeed, it could be that the meaning available to a reader without knowledge of particular (or historical—that is, accidental?) allusions may even be superior. The “insider’s” knowledge of particulars may interfere with the development of a sustained understanding of what the poet most wanted to say. This may be especially so if the “informed” reader recalls inconvenient facts about any of the historical personages alluded to, facts which may get in the way of grasping the enduring meaning of the terms used and the kind of event depicted.

The reader can be expected, however, to know something of the more dramatic qualities traditionally associated with the Phoenix. Is there something divine in its reputed characteristics, especially its routines of self-destruction and immediate rebirth (or resurrection)? What do its unique attributes—that is, attributes not shared with the Turtledove or with “anyone” else—do to how thorough and enduring the love celebrated in the poem can truly be?

It might even be wondered what is being suggested by Shakespeare in this poem about the relation between the divine and the human that is at the heart of Christianity? A critical problem here may be illuminated by recalling Aristotle’s suggestions (in the Nicomachean Ethics) about the relation of honor (or love?) to virtue. Honor may be sought, it is recognized, as a means for reassuring oneself of one’s virtue.

But would that human being be significantly inferior, no matter how exalted he may be by his fellows, who has to rely upon such guidance? Would not that human being be superior who does not have to depend on what others may—or may not—happen either to know or to say about him? Related to this is what Aristotle suggests (also in the Nicomachean Ethics) about who can—and who cannot—truly be friends.

Further illumination here may be provided by considering the problem of the relation between such critically divergent lovers as Achilles’ parents, mortal Peleus and divine Thetis, as indicated in Homer’s Iliad and elsewhere. Did the immortal Thetis play the part of the Phoenix to the markedly deteriorating Peleus’ Turtledove? And, for Shakespeare, how would the critical relations between the Divine and the Human in Christianity, with its self-sacrificing yet immortal divinity, be illuminated by the periodic “flaming” associated with the Phoenix?

It may also be wondered how well the Turtledove can ever know the particular manifestation of the Phoenix that he encounters, especially if the Phoenix is indeed anything like what scholars report about her repeated incarnations. It is also reported, we have seen, that the Phoenix legend was early pressed into the service of Christian teaching.5 What comment, then, might the poet of The Phoenix and Turtle be making about critical theological doctrines of his day?

However all this may be, what can be expected of any love to be developed by and with the perpetually reincarnated Phoenix? It might even be wondered, on behalf of (or even by?) the Turtledove, what “mutual flame” had been “enjoyed” theretofore (and especially with whom) by the Phoenix, and whether any of the Phoenix’s other partners in immolation had perished before their time for this privilege. Such inquiries need not endorse (even as they are aware of) the assessment of our poet voiced by George Bernard Shaw in his preface to Man and Superman:

The truth is, the world was to Shakespeare a great “stage of fools” on which he was utterly bewildered. He could see no sense in living at all.6

Or should we not make too much of the Turtledove’s mortality? May there not be, after all, something special about this Turtledove? Is he, too, being immortalized, if only in sentiment?

Is the celebration of love here a likely, if not even a necessary, illusion that lovers are moved by, at least for awhile? It may be wondered whether the Phoenix, as lover, is somehow moved to believe either that she will truly die with the Turtledove or that the Turtledove will be resurrected with her. We can be reminded by the Aristophanes of Plato’s Symposium of the errors about the currently grasped Other that Lovers are often inclined to embrace.

Another way of putting this inquiry is to ask whether the “eternity” to which the poem refers (58) can ever mean the same for both of such birds. Might at least the Phoenix know better how things stand—and are likely to develop—between them? Should we see here, therefore, that tension between truth and love which may be anticipated even in the most celebrated or exalted manifestations of True Love?

We can wonder as well whether it is merely a matter of chance that love can be seen to be literally the central word in the text of the complete poem (33)? It can be noticed too that central to the first part of the poem (the quatrains) seem to be the words one and two (26–27), while central to the second part (the triplets, or Threnos) seems to be the word married (61). Is it suggested thereby that love should be understood as the sentiment or activity that can move a couple to marry, to be somehow united in an authoritative way?

May it be, furthermore, a matter of chance how love is regarded or what happens because of it (including, here and there, suicidal developments)? It may be critical what lovers can truly know not only about “the other” (36) but also about themselves. Do the illusions that many, if not all, lovers depend upon contribute to the “confound[ing]” of reason that is noticed in the poem (41)?

A critical illusion here, we have noted, may be the notion—insisted on at the very end of the poem—that both of these birds are “dead” (67). Should it be wondered whether the Phoenix, even if she should be resurrected after her fiery embrace of the Turtledove, somehow perishes with him? That is, did this particular encounter of lovers somehow make subsequent reincarnations by the Phoenix severely limited, a prospect that the dying Turtledove can properly anticipate with satisfaction?

Critical to how the poem should be read is how the fate of the incinerated Phoenix should be regarded. Although nothing is said explicitly in this poem about the traditional understanding of the routine revival of this unique bird after its death, such a cycle seems to be recognized in the writings of Shakespeare’s contemporaries. This may be seen as well elsewhere in Shakespeare’s own work, as in Henry VI, Part 1 (IV.vii) and Henry VI, Part 3 (V.v).

The most significant recognition of the traditional Phoenix in a work associated with Shakespeare (aside from “The Phoenix and Turtle”) is seen in Henry VIII. There, Archbishop Cranmer can prophesy, as following upon the long and successful reign anticipated for the then-infant Elizabeth (V.v.40–43):

Nor shall this peace sleep with her; but as when

The bird of wonder dies, the maiden phoenix,

Her ashes new-create another heir

As great in admiration as herself …

These lines can remind us of the longevity, and hence at least a seeming immortality, that can follow from a political allegiance for which the greatest sacrifices may be made.

The importance of political rule, in “keep[ing] the obsequy so strict,” is recognized in what is said about “the eagle, feathered king,” of our poem (11–12). May the Phoenix, at least in the form noticed in the poem, be like the eminently successful political actor who goes out in a blaze of glory, so much so as to be periodically revived among its successors? Such an actor can well have (and may even need and treasure?) a companion whose devotion is so deep and so critical as not to require any public recognition, each being “the other’s mine” (36).

The “Threnos” (or lament), it is anticipated, will be provided by “Reason,” after it has been “in itself confounded” (41). It is recognized, that is, that there are matters touched upon here that are difficult to understand, especially when the basis and extent of fidelity are considered. The illusions of perpetuity may be needed to sustain useful associations (as may be seen, perhaps, in the celebrated insistence that one’s precious way “shall not perish from the earth”).7

It is recognized as well that the lovers invoke and depend on a “logic” of their own. Sometimes, indeed, they even call into question obviously reasonable considerations that are generally accepted. What do suggestions in this poem about love, illusion, and confidence suggest about how the plays of Shakespeare should be read (and not only Romeo and Juliet and Antony and Cleopatra)?

The concluding stanzas of our poem include these ominous lines:

Truth may seem, but cannot be;

Beauty brag, but ’tis not she,

Truth and beauty buried be. (62–65)

Even more ominous, perhaps, is the recognition (in the seventh stanza of the poem) that “Number there in love was slain.” (28) Can there be, without a proper grasp of number, a reliable ability to figure out both how things are and (perhaps even more critical) how they should be?

1. David Bevington, The Complete Works of Shakespeare, Sixth Edition (Longman, 2009) 1698. Most of the line and other citations in this text as well as notes have been supplied by the editors.

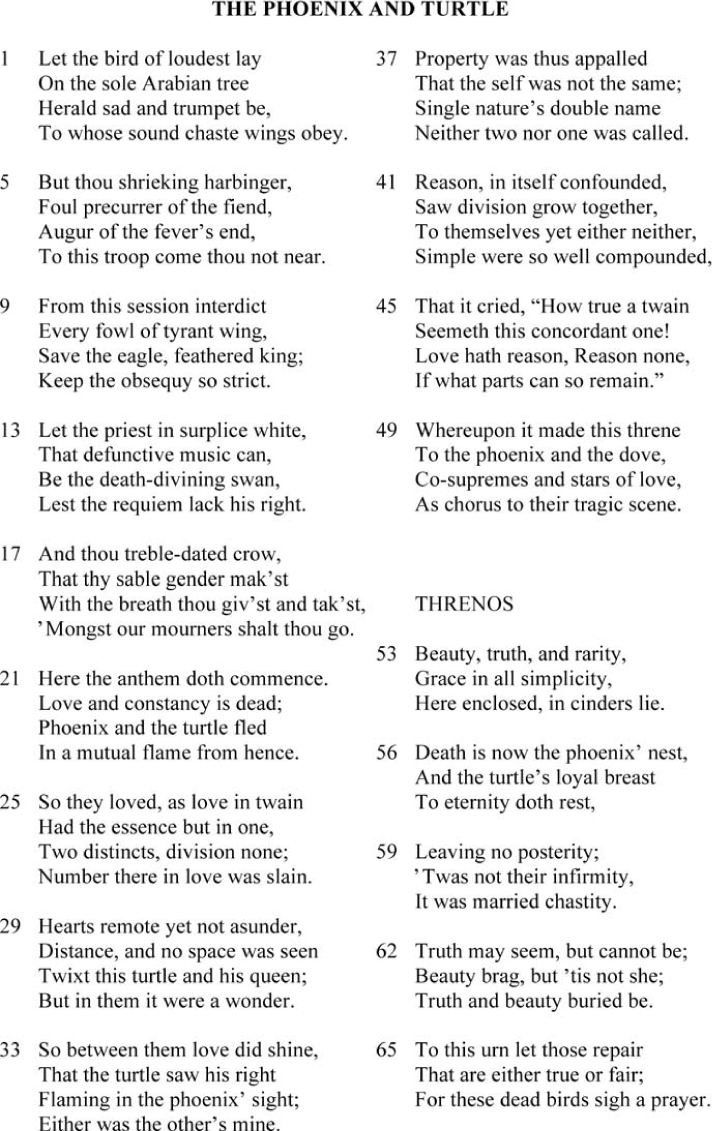

2. The full text of Shakespeare’s “The Phoenix and Turtle” as it appears in the Bevington edition is printed at the end of this chapter. Unless otherwise indicated all parenthetical references herein are to the line numbers of the poem.

3. “Phoenix” entry, Encyclopedia Britannica, Revised Fourteenth Edition (online).

4. The Westminster Dictionary of the Bible (Westminster Press, 1924) 615.

5. “Phoenix” entry, The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Revised Third Edition (Oxford University Press, 2003) 1174: The phoenix was “a potent symbol for both pagans and Christians.”

6. George Bernard Shaw, Epistle Dedicatory to Man and Superman (Penguin Classics, 2000) 30.

7. On Lincoln’s reading of Shakespeare, see George Anastaplo, Abraham Lincoln: A Constitutional Biography (Rowman and Littlefield, 1999); and “Shakespeare’s Politics Revisited,” in Perspectives on Politics in Shakespeare, eds. Murley and Sutton (Lexington, 2006) 197–242. For additional materials bearing on the discussion here, see: www.anastaplo.wordpress.com.