seven

INSIDERS AND OUTSIDERS

IN THIS SECOND PART OF THE BOOK, WE WILL EXPLORE how the cerebral mystique constrains our culture by reducing problems of human behavior to problems of the brain. Traits we traditionally viewed as built-in features of our abstract minds we now attribute to intrinsic aspects of our neurobiology. Although this picture promotes a more scientifically informed understanding of human activity than we previously had, it also preserves an exaggerated propensity—deeply rooted in our history and customs—to think of ourselves as autonomous individuals governed from within by our own brains or minds, rather than conditioned from the outside by the environment. In this chapter, we will examine social implications of the modern brain-centered view of human nature and its tendency to disregard external causes of behavior.

How we perceive the interplay between internal and external forces that shape us is a contentious topic that has consequences throughout our culture. In political and economic circles, conservatives and liberals are defined by the conflicting values they place on internally driven individual enterprise versus externally determined societal and environmental variables. The resulting tug-of-war influences tax codes and welfare programs, putting food on the table for some and sapping the savings of others. In the arena of criminal justice, the establishment of guilt and the prescription of punishment depend on a related contrast in attitudes about the importance of personal responsibility as opposed to the circumstances that led to a crime—internal motive versus external coercion. While President Barack Obama stressed the role of interdependent social forces with the soaring pronouncement that “justice is living up to the common creed that says, I am my brother’s keeper and my sister’s keeper,” his predecessor Ronald Reagan prominently enjoined Americans to “reject the idea that every time a law’s broken, society is guilty rather than the lawbreaker.” “It is time,” Reagan declared bluntly, “to restore the American precept that each individual is accountable for his actions.” Such philosophies go hand in hand with attitudes about how to encourage achievement and initiative in many other spheres of public life. Policies regarding intellectual property and government funding, for instance, reflect the tension between incentivizing individuals and fostering productive environments.

Conflicting opinions about the causes of human behavior also parallel the timeless dispute over whether nature or nurture is dominant in human development. Although the argument over how we function in the here and now is somewhat separable from the issue of how we got to be this way, a view that emphasizes the individual mind or brain as an internal driver of our actions will generally place less weight on external factors like education or upbringing that could have shaped us in the past. Conversely, a view that emphasizes our sensitivity to external context and environment as adults will tend to place more weight on the role of nurture during childhood. These positions in turn influence parenting strategies, educational philosophies, and social priorities.

Finding objectively justified compromises between inward- and outward-looking explanations of our actions is thus a broadly significant challenge, and the key to resolving it lies in the brain. This is because the brain is an essential link in the causal chain that binds our internal biology to the environment around us; it is the great communicator that relays signals from the outside world into each person and then back out again. Without a biologically grounded view of the brain, we overlook the reciprocal intercourse between the individual and his or her surroundings, and must instead take sides between internally and externally oriented views of human behavior. In idealizing the brain, we overplay its role as a powerful internal determinant of how people act. Conversely, by ignoring the brain, we might overstate the importance of external influences and fail to recognize individual differences. But by demystifying the brain and recognizing its continuity with the universe of influences around us, we can better appreciate how brain, body, and environment collaborate to guide our actions.

In the next sections, we will see how historically varying attitudes about the causes of human behavior have indeed led to radically different conceptions of the place of the individual in society. We will see in particular that today’s brain-centered stance emerged in part as a response to a contrasting, environment-centered philosophy called behaviorism, which at its heyday in the mid-twentieth century sought to explain human activity almost solely in terms of parameters of the external environment. Our subsequent turn toward inward-looking brain-based explanations now skews how we think about a host of phenomena, ranging from criminality to creativity—bringing our attention back to the individual, as opposed to his or her surroundings. A more balanced perspective is one that reemphasizes the external context that provides input and context for brain function. This is the perspective that treats us as the biological beings we are, with brains organically embedded in an extended fabric of causes and effects.

The history of psychology has been a history of debate over whether human behavior should be analyzed from inside or outside the individual, and whether internal or external factors are more important influences in people’s lives. Over the past 150 years, competing schools of thinkers have advocated opposing views and gained dominance over each other in phases, like swings of a great pendulum, bringing both intellectual and social consequences with them. The cyclical nature of these changes evokes ideas of the great German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel and his intellectual descendant Karl Marx, who saw history as series of dialectics, or conflicts between antithetical agencies, such as slaves and masters or workers and capitalists. In the political realm, Marx predicted that the back-and-forth struggle between classes would end with the institution of perfect equality and the universal “brotherhood of man”—a vision of social harmony that certainly has not been achieved. In psychology, however, the synthesis that reconciles internally versus externally focused views of behavior may yet be possible. Reaching this requires a biologically grounded view of the brain as mediator, however, and this has been largely lacking from major strands of psychological research.

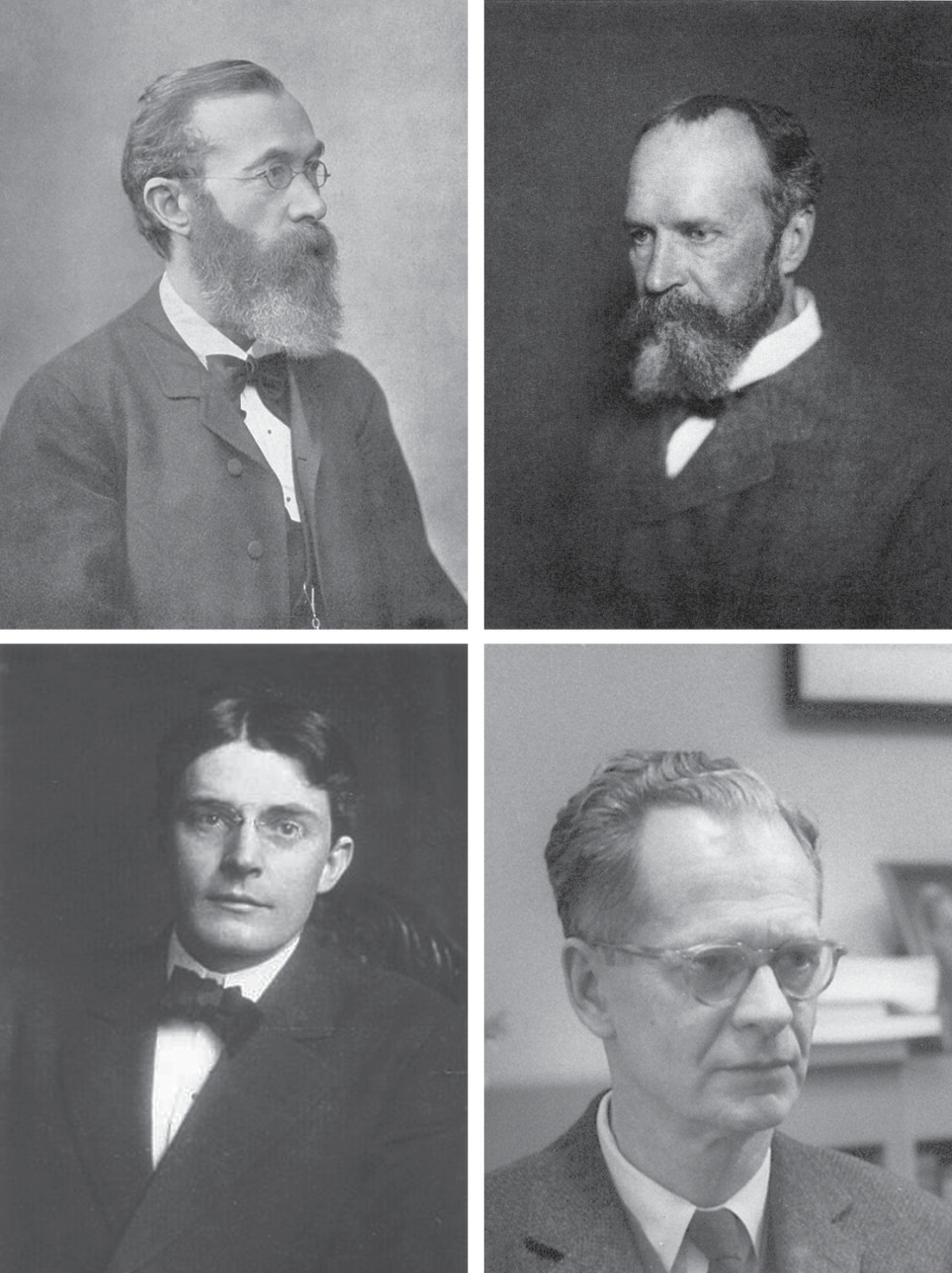

In the late nineteenth century, the study of the mind was “virtually indistinguishable from philosophy of the soul,” writes historian John O’Donnell. Even as philosophers turned to experiments, and psychology became a science, the discipline remained true to its name, from the ancient Greek word psyche, meaning “spirit.” To the so-called fathers of scientific psychology—most notably including Wilhelm Wundt in Germany and William James in the United States (see Figure 11)—the object of study was individual subjective consciousness, and the primary research method was introspection. The birth of modern psychology was thus firmly rooted in the notion of the mind as a self-contained entity to be examined from within, extending the tradition René Descartes began when he inferred his own existence from introspection with the immortal axiom “I think, therefore I am.”

Wilhelm Wundt wrote the first textbook in experimental psychology and founded what is regarded as the world’s first modern psychology laboratory at the University of Leipzig in 1879. In his youth, Wundt supposedly had a habit of daydreaming that interfered with his studies but may have prepared him for his later calling. He became interested in scientific research as a medical student under the guidance of his uncle, a professor of anatomy and physiology, and then went on to secure an enviable position as assistant to the revered physicist and physiologist Hermann von Helmholtz. As he grew more independent, Wundt brewed this mix of influences into a meticulous program of inquiry into the internal nature of the human mind.

Wundt’s research relied on introspection to dissect the structure of consciousness into fundamental elements such as feelings and perceptions, an approach that came to be known as structuralism. “In psychology,” Wundt wrote, “the person looks upon himself as from within and tries to explain the interrelations of those processes that this internal observation discloses.” In the laboratory, Wundt and his research team conducted experiments designed to probe the mental responses evoked by carefully adjusted external stimuli. In an effort to make their psychology more like physics, Wundt’s team made heavy use of precision instruments that now appear peculiar and passé. Tools of the trade included the tachistoscope, a device designed to expose a subject to visual stimuli for extremely brief periods of time; the kymograph, an automatic mechanical data recorder; and the chronoscope, an ultrafast stopwatch designed to time millisecond intervals.

In a typical experiment, Wundt’s students might record the duration of a mental process by positioning a study participant carefully in front of the tachistoscope, briefly flashing a visual stimulus, and then measuring the delay before which the subject reported his own subjective perceptions. Results would then come as a list of reaction times: thirty milliseconds for recognizing a color, fifty milliseconds for recognizing a letter, eighty milliseconds for making a choice, and so on. Broader conclusions were based on simple measurements obtained from multiple subjects under varying experimental conditions. For instance, Wundt noticed that letters written in the German gothic typeface of his time took longer to recognize than letters in Roman font, but that words in the two scripts were comprehended at the same rate; from this he inferred that the cognitive operation of reading a word does not depend on recognition of its individual letters.

Although Wundt’s experiments thus targeted the interface between worlds external and internal to the individual, his interest in the internal processes of the mind was paramount, and manipulating the external sensory world was merely a means to an end. External stimuli were a vehicle for setting mental processes in motion, and these were the true objects of study to him. According to Wundt, experimental psychology “strikes out first along that which leads from outside in,” but it “casts its attention primarily… toward the psychological side.”

Wundt also dismissed the need to study the brain and thus avoided delving into the processes by which stimuli meet and alter the mind of the individual. He associated the brain more closely with the external physical domain, connected to the universe of stimuli but distinct from the domain of inner psychological phenomena. Wundt felt that efforts to connect these two domains were largely speculative and unnecessary for understanding the mind. Consideration of brain physiology “gives up entirely the attempt to furnish any practical basis for the mental sciences,” he wrote in 1897. Views like these were energetically proselytized and elaborated by Wundt’s student Edward Titchener, an Englishman who studied in Leipzig and imported structuralism into America when he later settled at Cornell University. Titchener believed even more completely in the need to study the mind from within. “Experimental introspection is… our one reliable method of knowing ourselves,” he confidently proclaimed; “it is the sole gateway to psychology.”

William James was a contemporary of Wundt and Titchener who taught the first psychology class at Harvard University and supervised Harvard’s first doctorate in psychology. He was the scion of a wealthy and cultured New England family, but in intellectual terms a self-made man who dabbled in art, chemistry, and medicine before adopting an academic specialty that was still only partially born. Despite being brothers in arms on the same intellectual frontier, James had few kind words for the work of his noted European counterparts in the study of the mind. The hairsplitting experimental approach of Wundt and his coworkers “taxes patience to the utmost, and could hardly have arisen in a country whose natives could be bored,” James complained. Instead he advocated a more practical psychology, focused on understanding the mind and brain in terms of the functions they evolved over time to perform, rather than the components they are made of.

James had no use for the gizmos and gadgets of the structuralists, but he agreed wholeheartedly with their stance that the mind should be examined from within. “Introspective Observation,” James wrote, “is what we have to rely on first and foremost and always… I regard this belief as the most fundamental of all the postulates of Psychology.” In contrast to Wundt, James pledged allegiance to a biological view of the mind by beginning his 1890 magnum opus Principles of Psychology with two chapters about the brain. But although James postulated that mental activities correspond to processes in the brain, he struggled to explain their causal relationship. “Natural objects and processes… modify the brain, but mould it to no cognition of themselves,” he asserted. The exterior world could thus influence the physiology of the nervous system, but control of conscious cognition remained within. Ultimately James cast his lot in with mind-body dualism, explaining “that to posit a soul influenced in some mysterious way by the brain-states and responding to them by conscious affections of its own, seems to me the line of least logical resistance.”

The inward-looking attitudes of James, Wundt, and Titchener permeated the psychological community of their time. Their ideas spread across a sea of copious writings; Wundt alone is said to have authored more than fifty thousand pages of text. The teachings of psychology’s founding figures also crossed literal oceans, as many of the students trained at Harvard, Leipzig, and Cornell came to populate the first psychology departments to emerge in America and Europe. While some of the second generation departed from their mentors’ dedication to introspection and the study of individual consciousness, others found ways to influence the wider world with attitudes that sprang from precisely these approaches. The public face of psychology therefore mirrored its private academic form, organized around the self-regarding mind, shaped barely if at all by its situation in society or nature.

As a result, applied psychology at the turn of the twentieth century came to be dominated by an essentialist view of human nature—the idea that human capabilities and dispositions are inborn and often immutable. The most famous realization of this attitude was the emerging industry of mental testing, which was based on the concept that intelligence is an innate quality that can be measured objectively. Charles Spearman, Edward Thorndike, and James Cattell—all protégés of Wundt and James—were active in developing the first intelligence tests and the methods for interpreting them. Thorndike’s tests in particular became widely applied in the US military.

Several psychologists of this time were also involved in a related brand of essentialism: the eugenics movement. A notable advocate of both intelligence testing and eugenics was Harvard psychologist Robert Yerkes, who had trained with Wundt’s student Hugo Münsterberg. Yerkes argued that “the art of breeding better men, imperatively demands measurement of human traits of body and mind.” Cattell was another prominent eugenicist; he had once been a research assistant to Sir Francis Galton, the British scientist and polymath who coined the term eugenics in 1883. Less controversially from today’s perspective, Cattell was also a fervent advocate for academic freedom and personal liberty, individualist causes again resonant with the psychology of the time. This activism led Cattell to campaign publicly against US conscription in World War I; in doing so, he attracted such censure that he was forced to resign his professorship at Columbia University in 1917. Even in an age where the inborn attributes of individuals were most prized, there were limits to an individual’s ability to rebel against his surroundings.

The early twentieth century was rife with rebellions and revolutions. Even before the Balkan conflicts went viral and ignited global conflagration, China had liberated itself from four millennia of dynastic rule, Irish guerillas had taken up arms against Britain, and Mexico had plunged into a decade of civil conflict. The Great War itself would see the fall of monarchies and the reorganization of class structures throughout Europe and beyond. Working men and women found ways to cast off their chains. From Talinn on the Baltic to Dubrovnik on the Adriatic, an archipelago of new nations would rise from the rubble of the continental empires. Meanwhile, Ottoman West Asia was to disintegrate into a patchwork of synthetic states that simmer with discontent to this day.

Revolution arrived in the field of psychology as well in the spring of 1913, with the publication of a polemical manifesto written by a Johns Hopkins University professor named John B. Watson (see Figure 11). The manifesto was officially entitled “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It,” and it appeared as a seemingly innocuous nineteen-page article in the journal Psychological Review. Its first paragraph, however, unleashed a volley of iconoclastic declarations trained not only on the psychology of Wundt and James but also on the primacy of humankind itself:

Psychology as the behaviorist views it is a purely objective experimental branch of natural science. Its theoretical goal is the prediction and control of behavior. Introspection forms no essential part of its methods, nor is the scientific value of its data dependent upon the readiness with which they lend themselves to interpretation in terms of consciousness. The behaviorist, in his efforts to get a unitary scheme of animal response, recognizes no dividing line between man and brute. The behavior of man, with all of its refinement and complexity, forms only a part of the behaviorist’s total scheme of investigation.

With this salvo, Watson announced his intention to invert the priorities of his field by creating the new science of behaviorism. Watson and his followers proposed that psychologists should focus solely on studying outwardly observable behavior and its dependence on environmental factors that could be manipulated experimentally. Their goal was to establish rules by which behavioral patterns could be entrained and altered from the outside, while jettisoning all speculation about what might be going on within. Instead of dissecting the hidden spaces of the psyche, behaviorism would thus simply ignore them. Earlier work that sought to analyze human behavior in terms of unverifiable psychological categories was rejected as mentalism, a putdown that subsumed the subjective psychologies of the previous age. Even earlier research on animal intelligence was considered to be too colored by mentalist analysis—prone to the sorts of anthropomorphism that might fly well in folktales but that could not be tolerated in science. In Watson’s new movement, humans and animals became equally subject to dispassionate behaviorist observation and manipulation.

Initial reaction to Watson’s rallying cry was mixed. Many members of the psychology establishment resisted the call. Titchener regarded behaviorism as a crass effort to “exchange science for a technology” concerned more with behavioral control than with understanding anything. Robert Yerkes sharply protested Watson’s efforts to “throw overboard… the method of self-observation,” while Columbia’s James Cattell—no stranger to controversy himself—accused Watson of being “too radical.” But there were many others both inside and outside the field who found Watson’s stance attractive. Historian Franz Samelson has theorized that behaviorist sentiments played well to rising interest in social control in the wake of World War I, and that Watson’s rhetoric won converts by “combining the appeals of hardheaded science, pragmatic usefulness, and ideological liberation.” And although European psychologists notably held out against behaviorism, the alternatives they offered, such as the Gestalt school of Max Wertheimer and others, proved to be less influential. Meanwhile, the patient-focused analytical psychiatry of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung caught the public’s fancy but never gained force in scientific circles. It was behaviorism that came to dominate American psychology, effectively banishing introspection, consciousness, and other internal cognitive processes from intellectual discourse for over fifty years.

If Watson was the Moses of this movement, the great Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov was its burning bush. In their efforts to understand how the environment governs behavior, the behaviorists took inspiration from Pavlov’s world-renowned research on experimental manipulation of reflexes. The essential element of Pavlov’s paradigm was the stimulus-response relationship—the ability of certain environmental stimuli to elicit reproducible, virtually automatic reactions in an animal. Pavlov most notably studied the ability of food stimuli to evoke the response of salivation in dogs; this was an innate relationship that does not need to be learned. Pavlov found also, however, that new stimulus-response relationships could be artificially induced or conditioned. In a procedure now referred to as classical conditioning, Pavlov achieved this effect by pairing an arousing stimulus, such as the scent of meat, with a previously neutral stimulus, such as the ringing of a bell. After repeated tests in which the bell preceded the food, the dog would learn to salivate at the sound of the bell. In this way, the innocuous bell, a formerly unimportant part of the environment, came to exert control over an animal’s behavior.

Watson believed that such stimulus-response relationships could explain most forms of behavior, even in people, and that conditioning could entrain activities of arbitrary complexity. According to this view, the environment was a far more powerful factor than any internal quality in determining the behavior of an individual, at least within the bounds of what a given species could be capable of. In a self-acknowledged flight of hyperbole, Watson speculated that he could take any healthy infant at random “and train him to become any type of specialist [he] might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors.” This phrasing tacitly acknowledges the special sensitivity of infants to training and conditioning, a feature modern researchers now describe in terms of critical periods of early development, during which the brain may be easily reconfigured. Watson and other behaviorists were little inclined to delve into such neural processes, however; avoiding invasive techniques such as electrode recordings and microscopy of brain samples, they restricted their analysis to behavioral phenomena they could more readily observe and control.

Watson’s career was cut short after a scandalous extramarital affair with his research assistant forced him to resign his academic position in 1920, but a second generation of scientists soon emerged to reassert behaviorist perspectives in psychology. The leading spokesperson for these neobehaviorists was Burrhus Frederic (B. F.) Skinner (see Figure 11), an academic and popularizer who has been called the most influential psychologist of the twentieth century. Skinner promoted an experimental approach called operant conditioning, in which animals learn to associate their actions with intrinsically rewarding or aversive stimuli. In a typical example, a rat is placed in an unfamiliar mechanized box with a lever at one end. Every time the rat presses the lever, a food pellet is automatically dropped in for the animal to eat. At first the rat presses the lever only randomly, as part of its exploration of the box, but after a few rewards the animal learns that getting the food depends on pressing the lever. The lever pressing becomes more frequent and purposeful, and the behavior is said to have been reinforced. Using this method, animals can be trained to perform quite complex tasks, such as running mazes and making perceptual judgments. Skinner viewed operant conditioning as a teaching technique by which all sorts of human behaviors can also be established, from riding a bicycle to learning a language.

Behaviorists like Skinner wanted results not just in the lab but also in the wider world, which they pursued by exporting training methods from their laboratories. Several behaviorists developed educational strategies based on their science. A student of Skinner’s named Sidney Bijou experimented with using rewards and punishments such as the now-ubiquitous “time-out” to discipline and teach children. Bijou’s methods helped seed a more general approach known as applied behavioral analysis (ABA), which applies conditioning methods to improve behavior in contexts ranging from eating disorders to mental diseases. Offshoots of ABA remain in use today. Behaviorist principles also led to the development of so-called teaching machines. The first automatic teaching aids had been designed in the 1920s, but Skinner himself took the lead in updating and advertising the concept. Although his own efforts to commercialize a teaching machine met with only limited success, the publishing company Grolier successfully marketed a device called the MIN/MAX, which sold a hundred thousand units within its first two years. The MIN/MAX was a plastic box equipped with typewriter-like rollers, designed to present learning material to students through a little window. Students would answer questions displayed by the machine and then be “reinforced” with instant feedback as to whether their answers were correct or not—much like some of the teaching software available today.

The behaviorists’ approach of trying to influence actions by engineering the environment was carried to even greater lengths by several prominent architects and planners of the mid-twentieth century. Writing in 1923, the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier famously described houses as “machines for living in,” a behavioristic metaphor just a few years antecedent to the introduction of Skinner’s boxes. Le Corbusier and other modernist architectural trailblazers such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Walter Gropius experimented widely with open building plans and communal dwellings, through which architecture could cultivate specific patterns of domestic behavior. A number of communal settlements were also directly inspired by B. F. Skinner’s novel Walden Two, which described his conception of a behaviorist utopia. These settlements followed behaviorist policies such as a system of reinforcing labor through earned credits and a strong egalitarian ethos that ignored intrinsic differences between people.

For behaviorists, emphasis on external versus internal control of behavior went hand-in-hand with aversion to brain science. Ironically, John Watson himself had performed dissertation research on brain-behavior relationships in rats, but he later disavowed the need for special attention to the central nervous system. Instead, he advocated a more holistic biology, akin to the view I presented in Chapter 5 of this book. As Watson put it, “The behaviorist is interested in the way the whole body works” and should therefore be “vitally interested in the nervous system but only as an integral part of the whole body.” Watson contrasted this attitude with that of the introspectionists, who in his words treated the brain as a “mystery box” into which whatever could not be explained in purely mental terms was put. But Watson also insisted that the technology of his day was not up to the task of analyzing brain function, ensuring that the box would remain a mystery on his watch as well. Thirty years on, Skinner offered further reasons to neglect the brain. In his view, the nervous system was simply a causal intermediary between the environment and an individual’s behavior. In short, the brain is not where the action happens. As someone interested primarily in the prediction and control of behavior, Skinner argued that it is therefore both unnecessary and inefficient to study the brain. “We don’t need to learn about the brain,” he reportedly quipped. “We have operant conditioning.”

In the behaviorist’s worldview, the environment conditions the individual the way an artist paints her canvas. The environment determines the content, color, and consistency of the individual’s life. While today’s scientists sometimes analogize the brain to a powerful machine, the behaviorists were more likely to cast the environment as a machine, implementing or embodying rules of reinforcement to shape people born naively into the state of nature. The fatal flaw in behaviorism lay in this false dichotomy between the passive person and the active environment, a contrast that led to black-boxing of the individual as a substrate merely to be acted upon. Although each behaviorist experiment was based on careful attention to environmental factors, there was little consideration for the individual’s part in interpreting the universe, including the role of the brain. The behaviorists also had nothing to say about purely internal processes that do not result in observable actions. There was no place for an inner life of thoughts and perceptions, just as there was no place for the brain. This was behaviorism’s flavor of dualism: a separation of internal and external spaces that placed agency squarely outside the individual, inverting the dualism of predecessors like James, for whom control came from a soul or mind acting on the inside.

The philosopher John Searle mocked the behaviorist stance with a joke about two rigidly objective behaviorists taking stock after making love: “It was great for you, how was it for me?” says one to the other. There are no subjective feelings for these two—only observable behavior. Behaviorism’s greatest failure was not in the bedroom, however. As behaviorist psychologists sought increasingly to explain high-level human activities in terms of low-level conditioning, they ran into increasingly serious problems with their theory itself.

In 1959, the behaviorist framework received a mortal wound. In that year, a young linguist named Noam Chomsky published one of the most spectacular takedowns in the history of science, aimed straight at B. F. Skinner. Chomsky’s critique was ostensibly a review of Skinner’s book Verbal Behavior, which attempted to explain human language in terms of operant conditioning. Skinner had contended that verbal conversation can be explained by the kinds of stimulus-response relationships that form during conditioning. In Skinner’s view, reinforcement links various utterances to complex stimuli in the real world; stimuli thus come to determine the specifics of what is said in any given context. Chomsky scornfully dismissed this notion as simplistic and vague. Rather than limiting his critique to the contents of Skinner’s book, however, Chomsky examined each of behaviorism’s building blocks in a broader sense, deflating the approach as a whole and not only its application to language. His review of Verbal Behavior became a major landmark in psychology, akin to Watson’s manifesto.

Chomsky argued that outside of the highly controlled environment of the behaviorist’s laboratory, the concepts of stimulus, response, and reinforcement are all so poorly defined as to be practically meaningless. Situations where multiple stimuli are present and multiple activities are being performed pose particular problems. For instance, if a crying baby girl gets a cookie after wetting her diaper while playing with toys in her crib as grandpa sings to her, what determines which of the girl’s myriad actions is reinforced or which stimuli become associated with the rewarding cookie? Chomsky also noted numerous examples of activities that are performed without any apparent reinforcement at all, such as the ceaseless toiling of scholars over research projects of little interest to others, with no obvious reward in the offing. How can behaviorism explain what keeps these eggheads energized? To be fair to Skinner (and reflecting on my own experiences as an academic), there are probably still external motivations that can be invoked, but Chomsky was trying to make a more general point. He insisted that actions we perform for little or no reward can only properly be explained with reference to internal cognitive factors—in other words, variants of mentalism that behaviorists regarded as anathema. Conversely, Chomsky concluded that “the insights that have been achieved in the laboratories of the reinforcement theorist… can be applied to complex human behavior only in the most gross and superficial way.”

Chomsky’s excoriation of Skinner helped catalyze a wholesale reorientation of psychology back toward studying processes internal to individuals, an upheaval known as the cognitive revolution. In another swing of the great pendulum, the taboos of behaviorism were lifted, and the mind became kosher again. Several of the ideas that characterized psychology in the days before Watson underwent a resurgence following the cognitive revolution. First and foremost was the notion that the mind, rather than the environment, is the main force in people’s lives. Psychologist Steven Pinker summarizes the cognitivist view as one in which “the mind is connected to the world by the sense organs, which transduce physical energy into data structures in the brain, and by motor programs, by which the brain controls the muscles.” Like the commanding officer we encountered in Chapter 5, mental activity realized inside the brain guides actions based on the input it receives, exercising authority, adaptability, and autonomy.

Another old idea that resurfaced with the cognitive revolution was the concept of the mind as a parcellated apparatus, replete with numerous innate components specialized for performing different tasks. This balkanization of the mind evoked the central tenets of Wundt’s structuralism but deviated sharply from the behaviorist view of individuals as “blank slates” ready to be conditioned by the external world. Chomsky himself championed the thesis that the brain contains a language organ—a neural mechanism common to all people, without which verbal communication would not be possible. Cognitive psychologists theorize that the mind and brain also contain separate modules for many other functions, such as recognizing objects, arousing emotions, storing and recalling memories, solving problems, and so on. Pinker notes the similarity of this picture to traditional Western concepts of mental and spiritual life as well. “The theory of human nature coming out of the cognitive revolution has more in common with the Judeo-Christian theory of human nature… than with behaviorism,” he writes. “Behavior is not just emitted or elicited.… It comes from an internal struggle among mental modules with differing agendas and goals.”

After the cognitive revolution, advances in knowledge conspired with newfound emphasis on the internal qualities of individuals to promote a convergence of psychology with neuroscience. Researchers and laypeople alike came to equate mental functions with brain processes. The advent of functional brain imaging methods in the 1980s and 1990s particularly facilitated this connection and allowed neuroscientists to test hypotheses about the modularity of mental and neural organization together. In the era of cognitive science, resurgent appreciation for the complexity of the mind harmonized perfectly with the blossoming of research into what seemed like an infinitely complex organ of the mind. An equally important convergence occurred at the border between psychology and the emerging field of computer science. It was at this interface that computational theories of mental function arose, forwarded by such figures as the perceptual psychologist David Marr. Marr famously characterized the mind as an information-processing device based on the computational conversion of inputs to outputs using algorithms implemented in physical hardware. Captivated by such descriptions, many psychologists and neuroscientists of the time began to claim that “the mind is the software of the brain,” extending the computational model of mental processing into the full-blown metaphor for biological function discussed in Chapter 2.

The mystique of the brain reached its apogee during this time, and it is easy to see why. Currents of the cognitive revolution exalted the brain even as they undercut the significance of the wider world. Neuroscience became a hot topic, while behaviorism became a bad word, associated both with scientific superficiality and with the state-sponsored behavioral control of places like Stalinist Russia. With behaviorism dethroned, people came to think foremost of the brain when striving to get to the root of mental properties ranging from artistic genius to drug addiction, and it was correspondingly less common to consider extracerebral influences.

Some commentators have begun to use the word neuroessentialism to describe this phenomenon. “Many of us overtly or covertly believe… that our brains define who we are,” explains philosopher Adina Roskies in her definition of the neologism. “So in investigating the brain, we investigate the self,” she writes. This idea that the central nervous system constitutes our essence as individuals echoes the earlier essentialist attitudes of people like Wundt and James, who conceived of the mind as a set of inborn attributes, or of Yerkes and Cattell, who advocated the measurement and breeding of innate qualities as part of the intelligence testing and eugenics movements of the early twentieth century. The similarity between old and new views may indeed explain why modern psychology and neuroscience appear to be so compatible with traditional Western concepts of the soul.

The cerebral mystique and the scientific dualism we considered in Part 1 promote neuroessentialism by emphasizing soul-like qualities of the brain—its inscrutability, its power, and perhaps even its potential for immortality. The biochemical continuity and causal connections among brain, body, and environment are lost, and the brain alone comes to occupy the role of commander and controller. As a result, the divide between internal and external influences remains almost as stark as in the days of the earlier -isms, when the brain was largely ignored.

We have now seen how the cognitive revolution and the rise of neuroscience carried the brain to its central place as an explanatory factor in our lives. The neuroessentialist attitude that our key characteristics are determined by our brains reflects the continuing backlash against behaviorism and its emphasis on the environment. Like behaviorism, however, the modern brain-centered perspective often fails to produce an integrated picture of how internal and external factors combine to guide human activity. Instead, it encourages a focus on the role of the brain to the exclusion of other factors that influence what people think and do. We can appreciate this most clearly by considering a specific example of neuroessentialism in action.

The world’s most notorious icon of neuroessentialism spent its golden years steeping placidly in a jar of formaldehyde, secluded from civilization in a brain bank at the University of Texas at Austin. The specimen’s peaceful retirement belied a violent past, however; this past was stamped indelibly into its stripes of gray and white matter like stains and creases on an old piece of newspaper. For a start, the famous brain was far from intact. Soon after the organ had been extracted from its natural habitat, a pathologist’s knife sliced it into fillets, unkindly exposing its inner structures for an autopsy. Many of the cuts revealed gross disfigurations. The left frontal and temporal lobes, once seats of cognitive and sensory prowess behind the eye and ear, were brutally lacerated. Shards of bone had sheared across the tissue, forced through by the impact of hot lead bullets on the once protective skull. In another part of the brain, near a pinkish blotch called the red nucleus, the tissue had been pried apart by another kind of bullet—a malignant tumor the size of a walnut that would have meant certain death to its bearer, had metal projectiles not arrived first. The story of this tumor and the organ that harbored it illustrates how the problem of reconciling the agencies that act inside versus outside the individual remains unresolved even now.

The forlorn brain’s original owner, a former marine and trained sniper named Charles Whitman, had committed one of the worst mass murders in American history. In the early hours of August 1, 1966, he stabbed his mother and his wife to death. Later in the morning, he transported a small arsenal of weaponry to the top of the 307-foot Main Building on the UT Austin campus and unleashed a fusillade that killed or wounded forty-eight people in and around the tower. Two hours into the rampage, Whitman was finally cornered by Austin police and felled by two blasts from Officer Houston McCoy’s shotgun. To the public, not accustomed to outbreaks of military-style violence in civilian settings, the massacre was deeply unsettling. “In many ways Whitman forced America to face the truth about murder and how vulnerable the public could be in a free and open society,” writes author Gary Levergne in his book A Sniper in the Tower.

But it was Whitman’s brain that soon claimed center stage. In the months before the murders, Whitman had experienced painful headaches and also began seeking help from a psychiatrist. In a suicide note, he speculated that he was suffering from a mental disorder and urged investigators to perform a thorough autopsy to determine what could be wrong with him. When postmortem examination revealed the tumor near Whitman’s hypothalamus and amygdala, brain regions involved in emotional regulation, some seized on it as a possible explanation for his inexplicable act of destruction. Many of Whitman’s friends and family were particularly ready to believe that the brain tumor had changed his personality for the worse—that his diseased brain had made him commit the heinous crime.

Amygdala expert Joseph LeDoux thinks that the mere possibility of tumor-induced behavioral effects might have been enough to reduce the murderer’s sentence, if he had survived to trial. Neuroscientist David Eagleman goes much further; he argues that cases like Whitman’s uproot our notion of criminal responsibility, because they demonstrate the causal role of brain biology in behavior. We do not control our biology, so how can we be held responsible for it? Eagleman predicts that soon “we will be able to detect patterns at unimaginably small levels of the microcircuitry that correlate with behavioral problems.” Eagleman’s speculation is not too tendentious. In one of the most talked-about applications of neuroimaging technology, it has already become possible to look at criminals’ brains in situ. “Lawyers routinely order scans of convicted defendants’ brains and argue that a neurological impairment prevented them from controlling themselves,” writes judicial scholar Jeffrey Rosen. The movement has gone so far, he explains, that “a Florida court has held that the failure to admit neuroscience evidence during capital sentencing is grounds for a reversal.”

These perspectives powerfully illustrate the influence of neuroessentialism, expressed here in the notion that there could be inherent and perhaps immutable properties of a person’s brain that are enough to explain the nature of his or her acts, whether criminal or otherwise. The consequences of this conclusion are far-reaching. If our brains give rise to actions that are beyond our conscious control, then how can we continue to hold individuals accountable for what they do? Rather than judging the person guilty or innocent of his crimes, we should judge the brain guilty or innocent. Rather than punishing the perpetrator for biology beyond his control, we should remedy whatever fault we can find in his brain, or failing that, we should prescribe imprisonment merely as a means of protecting society, just as we might impound an unroadworthy car. Stanford neurobiologist Robert Sapolsky quips that “although it may seem dehumanizing to medicalize people into being broken cars, it can still be vastly more humane than moralizing them into being sinners.”

Charles Whitman’s brain, lazing quietly in a closet in Austin, served as a tangible symbol of these ideas—until one day it vanished. The murderer’s cerebral matter had been part of a collection of around two hundred neurological specimens bequeathed to UT Austin in the late 1980s. Roughly thirty years later, photographer Adam Voorhes and journalist Alex Hannaford sought out the brain in connection with a book about the collection. Their research prompted the revelation that about half of the specimens, including Whitman’s, had gone missing. “It’s a mystery worthy of a hard-boiled detective novel: 100 brains missing from campus, and apparently no one really knows what happened to them,” wrote Hannaford in the pages of the Atlantic. Amid widespread media attention, UT researchers struggled to find an explanation and soon reported that the lost brains had probably been disposed of as biological waste in 2002.

The strange disappearance of Whitman’s brain inspires a thought experiment to probe the limitations of neuroessentialism: Let us ask ourselves what would have happened if the brain had been erased even more completely from the picture. What if Whitman’s brain had vanished before the doctors got to it, and its malignant growth, or indeed any other neural abnormality, could not be invoked in order to rationalize his crime?

The answer is that we would be forced to look elsewhere for factors that could have contributed to the events—and we would easily find them in the records of the case. We would perceive, for instance, an atmosphere of social tension running throughout Whitman’s life. We would recognize the killer’s difficult relationship with his father, a martinet who beat Whitman’s mother and wrecked their marriage just months before the shooting. We would witness Whitman’s repeated career rejection—how he was forced to terminate his academic studies because of poor performance and later faced a humiliating court-martial and demotion in the marines. We would observe Whitman’s record of substance abuse (he had a jar of amphetamine with him on the day of the shootings). We would register the ease with which Whitman procured his weaponry, and we would appreciate his immersion in violent culture. We would see that Whitman had physical stature and strength without which he would not have been able to commit his acts. We might even note the scalding 99-degree Fahrenheit temperatures recorded around the time of the murders, which could have played a part in exposing the murderer’s latent aggression. In short, numerous circumstances around the killer could have contributed to his crime just as surely as his brain did.

The case of the Texas Tower murders is emblematic of the dichotomy that still persists between internal and external explanations of human behavior. There are two accounts of the perpetrator’s actions, one narrated from the inside and the other from the outside. One is a subjective story that could have been told by the nineteenth-century fathers of psychology we met earlier in the chapter—just substitute “brain” for “mind,” and it all falls into place. The other is a tale that sounds more like something John Watson or B. F. Skinner would have come up with. The narratives do not differ in the extent to which they assign moral responsibility to Charles Whitman. Whether the tragedy of August 1966 grew from a seed in Whitman’s brain or from a seminal event in the environment around him does not affect the amount of metaphysical blame we can place on his shoulders—in either case, he is a pawn in nature’s great game of life and death. The internally and externally centered accounts do differ, however, in the extent to which they focus our analysis on this one man and his internal makeup, versus the society and environment around him. They differ in the causes they lead us to consider paramount, and they differ in the ways they instruct us about how to prevent future calamities. Most importantly, they differ in the extent to which they spur us to think of justice and transgression as a matter of individuals’ actions or as a matter of the interactions that affect them. Neuroessentialism focuses our attention directly on the individual and his brain, but in doing so, we miss the other half of the picture.

If we cast our net more broadly, we can find further examples of neuroessentialism in numerous walks of life. In each context, describing a phenomenon in predominantly neural terms tends to blind us to alternative narratives built from external factors that act around the brain rather than within it. When we strive for explanations centered on the brain alone, we fall for what the philosopher Mary Midgley calls “the lure of simplicity.” We conceive of the brain as a colossus among causes, a plenary speaker rather than a panelist in the broader conversation among internal and external voices that might all deserve a hearing. The cerebral mystique prompts us to privilege the brain, in each situation making us less likely to consider the importance of body, environment, and society—even if we tacitly admit that they all play a role. This in turn affects how we understand and treat a range of social and behavioral problems in the real world.

Why are teenagers different from adults? We have all noticed the emotionally volatile and often reckless conduct of many adolescents, compared with adults. “Youth is hot and bold,” wrote the Bard of Avon, while “Age is weak and cold; Youth is wild and Age is tame.” Cognitive neuroscientist Sarah-Jayne Blakemore argues that immature brain biology may explain stereotypical adolescent traits such as heightened risk taking, poor impulse control, and self-consciousness. The teenage brain is not just a less experienced version of the adult model; evidence from neuroimaging studies shows both structural and dynamic differences between the brains of teenagers and grown-ups. “Regions within the limbic system have been found to be hypersensitive to the rewarding feeling of risk-taking in adolescents compared with adults,” Blakemore explains, “and at the very same time, the prefrontal cortex… which stops us taking excessive risks, is still very much in development in adolescents.”

Accounting for the immature behavior of teenagers in terms of the immaturity of their brains could be a risky business as well, however. For one thing, it goes without saying that a teenager’s biology differs from an older person’s in ways that go far beyond the nervous system. Regardless of brain disparities, hormonal and other bodily influences dramatically affect how teens feel about themselves and how they react to situations. We might also note that modern-day late teens were in the prime of life by the standards of prehistoric times, when evolution picked us apart from our apish ancestors and life expectancy was probably well under thirty. Today’s late adolescent brain would have come across as comparatively grown-up back in 50,000 BCE. The most radical differences between contemporary adolescents and their late Paleolithic counterparts are cultural rather than physiological. This suggests that what makes teenagers seem immature now might also have more to do with culture than with biology. In our place and time, teenagers inhabit a vastly different world from adults. They have a quality and quantity of social interaction that few adults experience, their lives are scripted and controlled in ways few adults would embrace, and their daily goals are very different from those of their parents or grandparents. Disentangling the consequences of brain biology from these environmental factors is next to impossible. But if we are trying to understand and possibly correct the special foibles of our teenage relatives or friends, it seems simplistic to focus mainly on the idiosyncrasies of their brains.

What makes someone a drug addict? Addictive drugs are not just more potent versions of other things we enjoy, like good food or sunny days; they actually penetrate into the brain and directly change the behavior of brain cells. The past two decades have seen tremendous progress in elucidating which brain processes are involved in susceptibility to narcotics, some of which I work on in my own lab. Stressing the centrality of brain biology, the US National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) now defines addiction as “a chronic, relapsing brain disease that is characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use, despite harmful consequences.” Part of NIDA’s objective in describing addiction in this way is to try to mitigate the moral stigma associated with substance abuse. Explaining addiction in terms of subconscious brain functions seems to relieve the addict of guilt—just as evidence of brain pathology apparently exonerates criminals like Charles Whitman.

But it is not necessary to blame brain biology in order to forgive the addict. External social and environmental variables such as peer pressure and weak family structure are well-known risk factors for addiction, as is being male or growing up poor. A person stuck in such conditions can barely be blamed more for his or her situation than a person with brain disease can be blamed for having an illness. Meanwhile, characterizing addiction as a brain disease may constrain the available avenues for treating it. Sally Satel and Scott Lilienfeld argue that the brain disease model “diverts attention from promising behavioral therapies that challenge the inevitability of relapse.” Psychiatrist Lance Dodes advances a similar point, emphasizing the environmental stimuli that contribute to drug use. He writes that “addictive acts occur when precipitated by emotionally significant events… and they can be replaced by other emotionally meaningful actions.” At an even broader level, addiction calls for solutions that involve social and cultural elements in a way that other noninfectious diseases like cancer do not. Efforts to reduce poverty, keep families together, and improve school settings might turn out to be as influential as efforts to combat addiction-related processes within the brain itself, for example using brain medicines. Addiction is a multidimensional phenomenon, and it is important to maintain sensitivity to dimensions that extend beyond the head.

What makes someone an outstanding artist, scientist, or entrepreneur? The hero of Mel Brooks’s 1974 comedy Young Frankenstein believes that his man-made monster can become a genius by receiving the transplanted brain of the great German “scientist and saint” Hans Delbrück. But is having a great brain really what it takes to become a great contributor to society? We saw in Chapter 1 that researchers have struggled for over a hundred years to relate extraordinary personal achievements to characteristics of the brain. Science writer Brian Burrell tells us that “none of the studies of… ‘elite’ brains have been able to conclusively pinpoint the source of mental greatness,” but this does not stop people from continuing the search today. Modern researchers apply neuroimaging tools to locate what psychologist and US National Medal of Science winner Nancy Andreasen calls “unique features of the creative brain.” In her own work, Andreasen has discovered patterns of brain function that appear to distinguish writers, artists, and scientists from ostensibly less creative professionals. Other researchers have examined fMRI-based correlates of improvisation, innovative thinking, and additional hallmarks of creativity.

While few scientists would dispute the notion that brain biology underlies differences in many cognitive abilities, we also know that culture, education, and economic status contribute enormously to the expression of such abilities in creative acts. According to studies of creativity in identical twins, evidence for a genetic role—which would determine inborn aspects of brain structure—is ambiguous at best. Meanwhile, a country with one of the most ethnically and presumably neurally heterogeneous populations in the world (the United States) is also one with by far the largest number of Nobel laureates. This kind of statistic casts doubt on the notion that a single brain type or set of characteristics is what fosters creativity in multiple walks of life. In other words, there can be no such thing as a “creative brain.”

Psychologist Kevin Dunbar has studied creativity in molecular biology labs and found that new ideas were most likely to come from group discussions involving diverse input, as opposed to from individual scientists working with their brains in relative isolation. In some cases, the principle that creativity comes from the convergence of disparate ideas creates entire fields that seem innovative, like nanotechnology or climate science. Even when individuals are working on their own, the insights they have may be prompted by exposure to a diversity of environmental stimuli. “A change in perspective, in physical location,… forces us to reconsider the world, to look at things from a different angle,” writes journalist Maria Konnikova, who has made a study of creative processes. She explains that sometimes “that change in perspective can be the spark that makes a difficult decision manageable, or that engenders creativity where none existed before.” In contrast, the conception that creative acts arise from a “creative brain” reduces the trove of biological and environmental influences down to a neuroessentialist nugget. If we are trying to understand or encourage creativity in our society, attending to the world around the brain may be just as important as cultivating the brain itself.

Where does morality come from, and what makes people perceive actions as right or wrong? One of the most fascinating manifestations of neuroessentialism lies in the resurgent movement to describe morality in terms of innate mechanisms in the brain. In 1819 Franz Gall had placed an organ of “moral sense” above the forehead, near the meeting of the brain’s left and right frontal lobes. Reflecting a more recent view, Leo Pascual, Paulo Rodrigues, and David Gallardo-Pujol of the University of Barcelona explain that “morality is a set of complex emotional and cognitive processes that is reflected across many brain domains.” Functional neuroimaging studies point to relationships between moral reasoning and activation of areas associated with a potpourri of processes, from empathy and emotion to memory and decision making. Such findings jibe with our intuitions about the complexity that underlies many moral problems, and they also give physical homes to the various considerations we tend to weigh.

But framing moral processing foremost in neural terms serves once again to distract from the importance of environmental and social influences. Like other choices we make, ethical decisions are highly dependent on intangible external factors, as well as on bodily states. Extracerebral factors that interact with our emotions can affect our moral calculus—for instance, by biasing us toward or against aggressive behavior. Our internal moral compass is even more dramatically swayed by social cues. Most obviously, we tend to let our guard down when we feel that nobody is looking. Conversely, we may be more likely to perform questionable actions when they seem to be socially accepted. This was stunningly demonstrated by Yale University’s Stanley Milgram, who showed in a 1963 study that two-thirds of a randomly recruited group of forty male subjects were willing to administer painful 450-volt electric shocks to strangers when encouraged to do so by an experimenter in a laboratory setting. Psychologist Joshua Greene, who leads Harvard’s Moral Cognition Lab, notes that the neural mechanisms involved in moral choices are “not specific to morality at all.” In fact, what places a choice in the moral domain at all is precisely its dependence on external context and on the culturally conditioned judgments of others about what constitutes right and wrong behavior. We risk losing sight of this if we boil moral reasoning down to brain processes independent of the external features that feed into them.

The question of what makes individuals the way they are is analogous to a central issue addressed by historians: What made events unfold the way they did? The Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle gave a stark answer to this question, writing that “the history of what man has accomplished in this world, is at bottom the History of the Great Men who have worked here.” Gazing across the cultural landscape that surrounded him in 1840, it seemed to Carlyle that “all things that we see standing accomplished in the world are properly the outer material result, the practical realization and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt in the Great Men sent into the world.” This was the Great Man theory of history—the hypothesis that the minds of a few notable people transformed civilizations around them and determined the course of events. In Carlyle’s metaphor, the likes of the poets Dante and Shakespeare, the scholars Johnson and Rousseau, and the tyrants Cromwell and Napoleon were nothing less than beacons of light, “shining by the gift of Heaven,” and bestowing “native original insight, of manhood and heroic nobleness,” on the dim multitudes around them.

In a culture now swayed by the cerebral mystique, light shines not from the Great Men of the past but from our brains. It is a picture that William James himself evoked when he wrote that all of humankind’s inventions “were flashes of genius in an individual head, of which the outer environment showed no sign.” A line connects James’s words to the luminescent brain images in today’s pop neuroscience articles, and to the reduction of problems of the modern world to problems of the brain. But rebutting the neuroessentialist thesis that the brain is an autonomous, internal engine of our actions is an equally extreme antithesis: the behaviorist’s view of human endeavors as explained primarily by the environment.

Today we can bring the sparring sides together. With the cognitive rebellion against behaviorism receding into the past, and with growing understanding of the ways in which the brain interacts with its surroundings, we need no longer see the internally and externally weighted views of human nature as necessarily opposed. In the age of neuroscience, we can doubt neither the life of our minds nor the central role of our brains in it. But at the same time, we cannot doubt that external forces extend their fingers into the remotest regions of our brains, feeding our thoughts with a continuous influx of sensory input from which it is impossible to hide. We also cannot deny that each of our acts is guided by the minute contours of our surroundings, from the shapes of the door handles we use to the social structures we participate in. Science teaches us that the nervous system is completely integrated into these surroundings, composed of the same substances and subject to the same laws of cause and effect that reign at large—and that our biology-based minds are the products of this synthesis. Our brains are not mysterious beacons, glowing with inner radiance against a dark void. Instead, they are organic prisms that refract the light of the universe back out into itself. It is in the biological milieu of the brain that the inward-looking world of Wundt and today’s neuroessentialists melts without boundary into the extroverted world of Watson and Skinner. They are one and the same.