CHAPTER ELEVEN

Keep What We’ve Got

IF THE UNITED States had built out the fleet of nuclear power plants it once planned, we would be much closer to solving climate change today. Largely because of the agitation of antinuclear groups such as Greenpeace, most of the planned nuclear power plants were never built, and quite a few that had been partly built were abandoned. A wave of new planned nuclear power plants in the early 2000s1 has also been scrapped since the 2011 Fukushima accident.

Recently, these groups have expanded their antinuclear goals and are successfully lobbying and lawyering to shut down existing nuclear power plants before the end of their useful lives. We have seen how Germany is doing this in a post-Fukushima panic and how that decision has stalled Germany’s progress in reducing CO2 emissions (see Chapter 3). The story is the same elsewhere.

With cheap fossil fuels available as an alternative—methane or coal, depending on the country—power producers can hardly be blamed for bailing out on nuclear power after facing nonstop litigation, regulation, and agitation from antinuclear groups. But in every case, nuclear power capacity has been at least partially replaced by fossil fuels, and CO2 emissions have risen as a result. Back in the 1970s, people did not understand climate change, and had far less experience with the safety of nuclear power, so antinuclear activism was more understandable. Today, the context has completely changed, but the antinuclear groups have not updated their perspective.

One of the least expensive clean-energy sources in the world is an existing nuclear power plant already generating electricity today. Nuclear power plants are expensive to build but inexpensive to operate, so once you have one working fine, it makes sense to keep using it. There are 449 power reactors operating around the world, 99 of them in the United States, where nuclear power supplies 20 percent of electricity.2 In the United States, that is more than hydropower, wind, and solar combined. Worldwide, nuclear power is second only to hydropower among carbon-free energy sources.3 A no-brainer way to combat climate change today is to start by simply not closing down existing nuclear power plants. Shutting down a leading low-carbon electricity source at this critical moment in history is a step backward in solving the climate problem.

Pressure to close existing nuclear power plants does not come from frightened residents near the plant. On the contrary, polling shows that people living closest to a plant are most supportive, with 83 percent support among those living within ten miles of a US plant and 82 percent among those living within 30–50 miles in Sweden.4 (Also, more than three-quarters of Americans who consider themselves well informed about nuclear power support it, versus about half for those who consider themselves not well informed.)5 Those who live closest understand a nuclear power plant best, benefit most from its jobs, and see they have little to fear. Those who live farther away do not understand the science and engineering, or the safety plans, and their fears fill that void.6 These fears among the uninformed public are the raw material with which well-funded antinuclear organizations fuel their campaigns to close existing plants.

Vermont Yankee

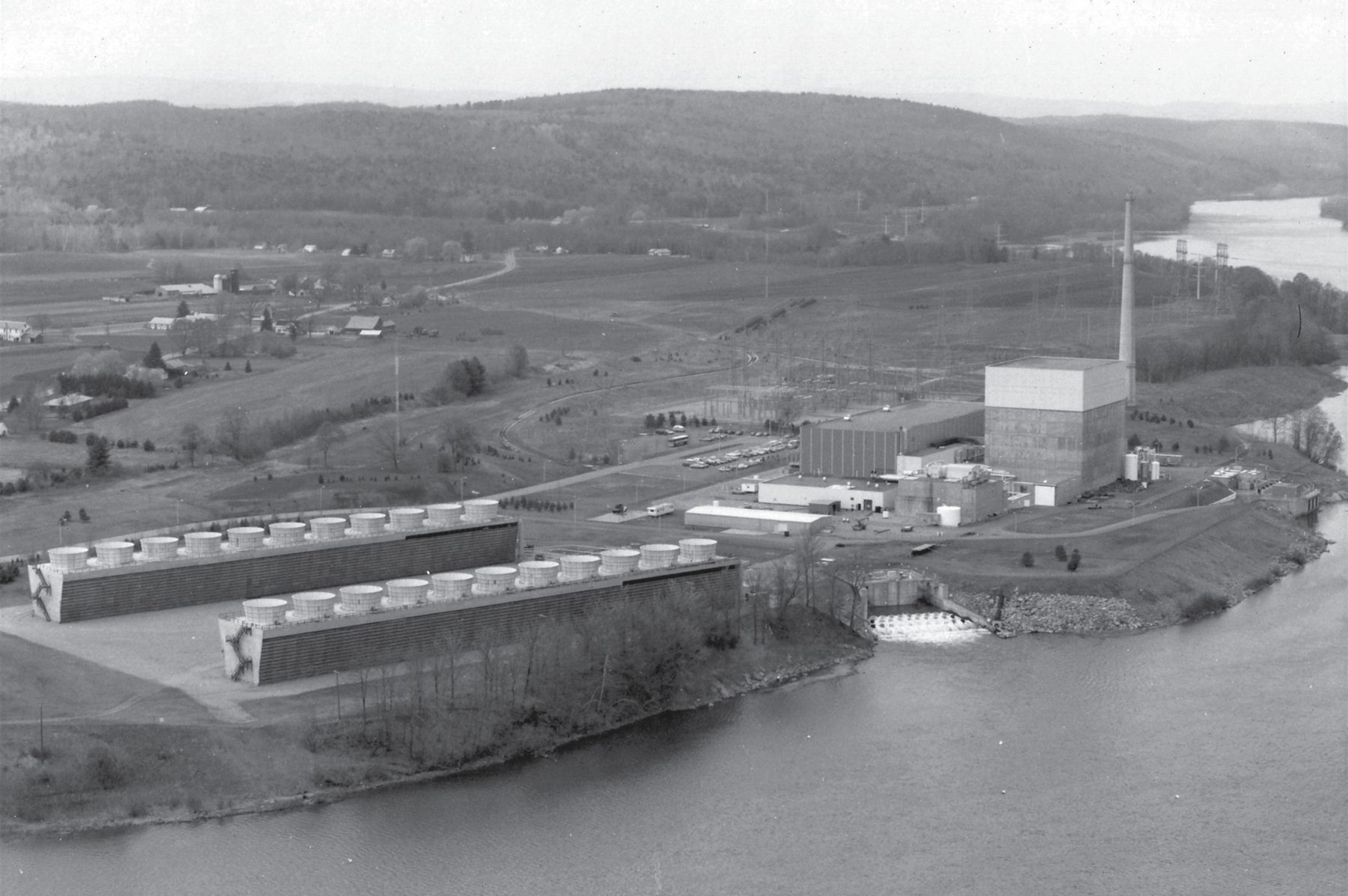

Consider Vermont and western Massachusetts, where, until recently, most of the carbon-free electricity was supplied by the Vermont Yankee power plant, located near the Massachusetts border. The region had been a hotbed of antinuclear activism ever since the movement began in the 1970s as a campaign to stop two nuclear reactors planned for a site in Massachusetts just downriver. (The utility unwisely sited the planned nuclear power plant near three hippie communes, sparking opposition that spread to neighboring towns and eventually led to the plant’s cancellation.)7

Figure 39. Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant. Photo: Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

In 2010 the Vermont Legislature passed a law against Vermont Yankee’s continued operation, and that same year a new governor was elected who had led the opposition to the plant. Despite the relicensing of the plant for twenty more years in 2011, the owner announced in 2013 that Vermont Yankee would close the next year.

Vermont Yankee had been providing electricity wholesale at about 4 cents/kWh and tried unsuccessfully to negotiate a new Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) with Vermont at 4.5 cents.8 This is not quite as cheap as methane at current low prices (since fracking). But it is far cheaper than clean alternatives such as wind and sun. In fact, at the same time, Massachusetts was negotiating an agreement for offshore wind power at almost 19 cents/kWh.9

Vermont Yankee faced competition from subsidized energy sources. Fossil fuels are subsidized and not just by being allowed to dump CO2 in the air with no charge. An estimate of US government energy subsidies up through 2003, about $650 billion, breaks down as 47 percent to oil, 13 percent each to coal and gas, 11 percent to hydropower, 10 percent to nuclear power, and 6 percent to renewables.10

In recent years, renewables have been strongly subsidized by both federal and state governments. Many states mandate that utilities include a certain amount of renewables—not a certain amount of carbon-free generation—and nuclear power is not included. For example, in Vermont in 2013, in addition to the state’s share of $15 billion in federal subsidies for renewables, state-level subsidies included customer credits, grants, loans, feed-in tariffs (price guarantees), investment-tax credits, property-tax abatements, sales-tax exemptions, and buybacks of excess capacity at peak times.11

In the context of subsidies for both fossil fuels and renewables, a plant such as Vermont Yankee has a hard road. Methane is cheap, and renewables are cool. Every move gets scrutinized by regulators and protested by activists. It doesn’t help that the companies that own nuclear power plants often also own fossil plants. (The owner of Vermont Yankee operates one-third nuclear power plants and two-thirds fossil fuel.) If they replace a nuclear power plant with a methane plant, they can compete better and sell more electricity. The Vermont state government would not sign a PPA to guarantee a steady market and price for nuclear-generated electricity. At the end of 2014, Vermont Yankee closed after forty-two years of operation, with seventeen years left on its operating license.

In western Massachusetts, when Vermont Yankee went offline, electricity prices spiked. As methane filled in to produce electricity, the gas company demanded to build new methane pipelines to supply the region. Climate activists argued, correctly, that investments in that kind of fossil-fuel infrastructure, which would last for decades, would lock us into a fossil economy far into the future. They marched against the gas pipelines and had some success in delaying and canceling them. So the gas company imposed a moratorium on new gas hookups for communities along the Connecticut River. Business suffered, and new construction had to use the more expensive fossil-fuel propane instead of methane. Two years later, that’s where things still stood.

Transmission lines to bring in Canadian hydropower were another planned way to offset the loss of Vermont Yankee (and the Massachusetts coal plants that shut down). But the largest-scale attempt to add renewable electricity for Massachusetts, 1100 MW of hydropower from Canada, was rejected in 2018. After a seven-year, $250 million application process, New Hampshire regulators saw the power lines through their state as an eyesore.12

During a prolonged cold spell in December–January 2017–2018, when New England temperatures remained below freezing for weeks at a time, the grid suffered from the absence of Vermont Yankee. With methane supplies diverted to home heating needs, the grid switched to oil as the leading fuel for electric generation. Supplies of fuel oil, kept at generating stations for such a contingency, dwindled to alarmingly low levels over several weeks. Oil trucking capabilities were stretched to the maximum, and icebreakers opened routes for oil deliveries by sea. Carbon emissions rose. LNG stores supplemented pipeline gas, but supplies remained extremely tight. Natural gas prices in Massachusetts peaked briefly at twenty times the price just a month earlier. The price of electricity jumped fivefold.13 Solar power was diminished seasonally (winter) and dropped to near zero at times, owing to snow. The closing of Vermont Yankee was not the main factor in this situation but contributed to it.

Massachusetts now plans to close its last remaining nuclear power plant, Pilgrim, in 2019, with thirteen years still left on its license. Much more electricity generation will be lost with the closing of this one nuclear power plant than Massachusetts generates with all its solar, wind, and hydropower combined.14

After Vermont Yankee closed, CO2 emission rates rose across New England, reversing a decade of declines.15 Emissions for all of New England rose almost 3 percent within a year. This rise amounted to a million more tons of CO2 per year added to the atmosphere. The problem is not so much the increase but the failure to decrease. If a politically liberal, rich, and technologically advanced region such as New England cannot rapidly decarbonize, what hope is there for the world as a whole to do so?

New England still gets 30 percent of its electricity from nuclear power, but with the last plant in Massachusetts set to close in 2019, only one in Connecticut and one in New Hampshire will remain. As the last Massachusetts plant goes offline, it will be replaced with methane and oil, and emissions will again rise, or at least fail to decline.

Other US States

California, like Massachusetts, is closing all its nuclear power plants. It closed the 2 GW San Onofre plant in 2013 and missed its CO2 emissions targets as a result. Methane, again, replaced the lost capacity.16

Recently, the state announced a big agreement among the utility, the antinuclear groups, the labor unions, and the state to close the last nuclear power plant, Diablo Canyon. The plant generates 9 percent of California’s electricity and has operated successfully for thirty-one years. The agreement declares that Diablo Canyon will be replaced with clean renewable power, but this is misleading.

Figure 40. California energy mix, 2016, after the San Onofre nuclear power plant closed but with Diablo Canyon still operating. Data source: California Energy Commission.

First of all, any renewable power that is built could be replacing fossil fuels if it were not replacing nuclear power. This is the same situation we saw in Germany.

Second, despite its lofty declarations to replace Diablo with clean energy, the agreement does not specify how this will happen. It states that “the Parties cannot, and it would be a mistake to try to, specify all the necessary replacement procurement now.”17 The day that Diablo Canyon closes down, but Californians do not stop using electricity, it appears likely that methane will fill the gap.

The most recent US nuclear reactors under construction, in South Carolina, were set to replace the current coal generation supplying electricity to that state. However, under the pressure of cost overruns, regulatory gum-ups, delays, and political pressures, the plants were canceled in 2017, with billions of dollars lost. (Two reactors at a plant in Georgia remain under construction.)

On Long Island, in 1989, the $6 billion Shoreham nuclear power plant was completed and set to open but instead closed when political opposition forced its cancellation and replacement with fossil fuels. The fossil fuel that replaced Shoreham has, in the intervening years, contributed on the order of 80 million tons of CO2 to the atmosphere.18 That’s the weight of about 40 million Ford Explorers, also known as a lot of CO2.

Several US states have recently decided to give subsidies to existing nuclear power plants similar to the credits given to renewables. Illinois, New York, and New Jersey have saved large nuclear power plants in this way, and Connecticut is moving in the same direction. New York’s action, however, is a mixed bag, as it saves several reactors upstate but shuts down the 2 GW twin reactors at Indian Point that have powered New York City for decades.19

Nationally, a capacity of 5 GW, more than the Swedish power station at Ringhals (see Chapter 1), was lost to nuclear power plant retirements in 2013–2017. The US government expects a similar decrease in the next nine years.20

Other Countries

Alarmingly, the trend to shut down existing perfectly good nuclear power plants seems to be spreading around the world. Since the Fukushima accident in 2011, politicians in many countries have concluded that opposition to nuclear power and fears of disaster are forces they do not wish to stand up against. Sadly, there is almost no public opposition or political price to pay for approving a new methane gas power plant or, in many countries, a new coal plant.

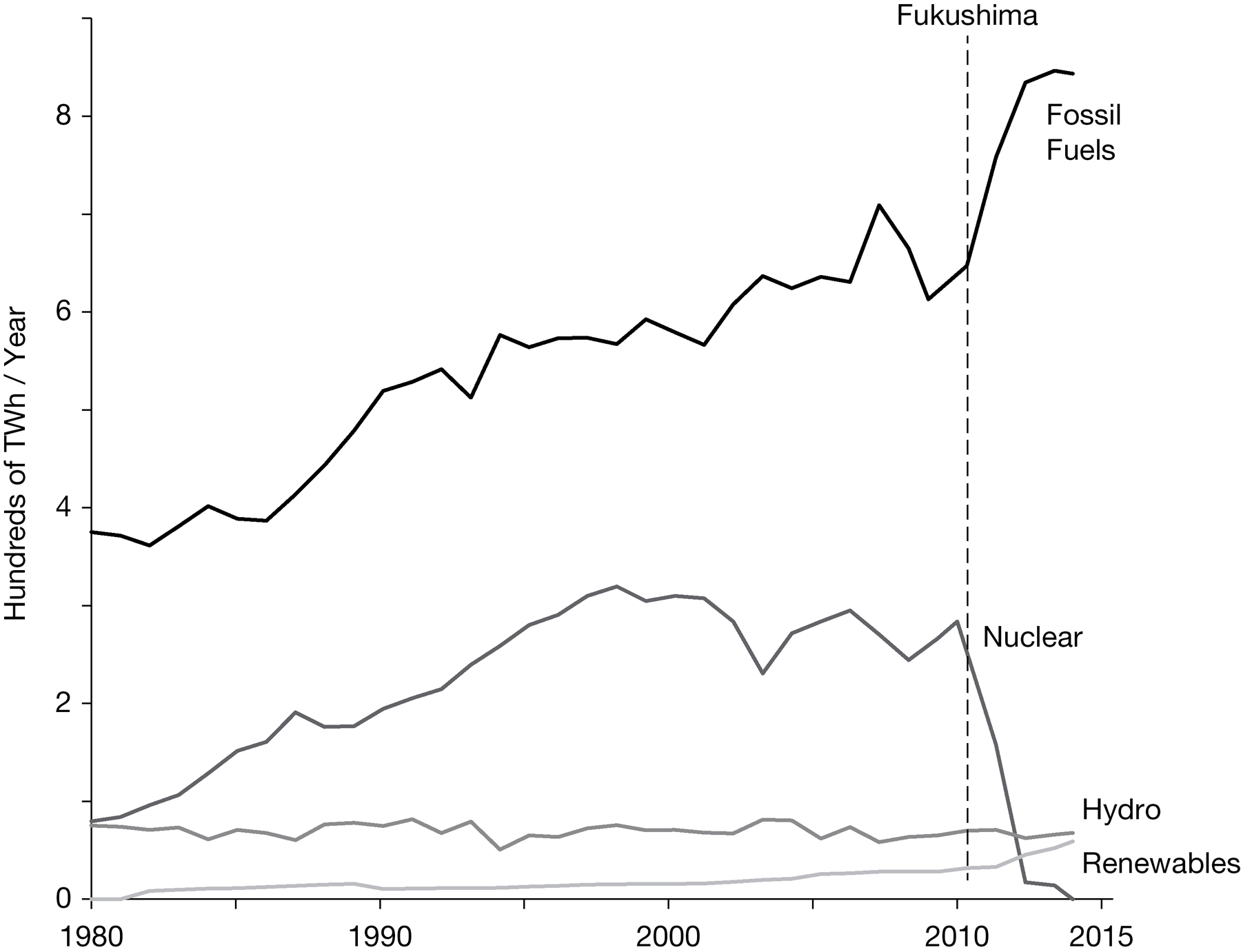

Figure 41. Japan’s electricity production mix, 1980–2014. Renewables include wind, solar, geothermal, and biomass. Data source: US Energy Information Administration.

Japan is an extreme case. Six years after the Fukushima accident, it has forty-two usable nuclear reactors sitting idle with a capacity of around 40 GW, the equivalent of about ten Ringhals plants.21 This massive electric capacity has been replaced by imported coal, oil, and gas, with new coal plants now planned.22 Japan has blown through its carbon emission goals with little prospect of meeting its commitments. The country could save a lot of money and a lot of CO2 by restarting its reactor fleet. By early 2018, more than six years after the earthquake/tsunami, about half of Japan’s reactors had applied for permission to restart operations, but only five were back on the grid.

France had planned to cut its nuclear power production from 75 percent of all electricity to 50 percent by 2025 in response to post-Fukushima antinuclear activism. However, in late 2017, the French environment minister announced a delay in that action for a decade. The minister, a leading French environmentalist, declared that France’s priority must be to first shut down coal and other fossil-fuel plants to reduce carbon emissions.23 These statements were followed up by French president Emmanuel Macron, who argued that France would not follow Germany’s example by phasing out nuclear power, because his priority was to cut carbon emissions and shut down polluting coal-fired production. Vive la France!24

South Korea, one of the most successful nuclear power producers in recent years, has also flirted with a nuclear power shutdown recently. Decades ago, the country began by importing nuclear technology and then trained a generation of its own scientists and engineers to become self-reliant. With a standardized Korean design, it cranked out nuclear power plants very successfully and generated electricity at less than 5 cents/kWh.25 But before South Korea’s 2017 presidential election, Greenpeace and others heavily publicized a feature film about a nuclear power disaster, complete with a lot of explosions and deaths. This campaign moved public opinion to some extent, and a new president was elected who favored phasing out South Korea’s nuclear power plants.26

The president halted construction on two nuclear power plants that had already received more than $1 billion in spending, and he appointed a citizens jury of almost five hundred people from all backgrounds to recommend future actions regarding nuclear power. In October 2017, the jury recommended, and the president accepted, restarting construction on the two reactors. However, it favored a longer-term policy of phasing out nuclear power. Six additional reactors that had been planned, but have not yet begun construction, remain canceled.27 If South Korea sticks with its phaseout plan, nuclear power will be replaced with methane, costing billions of dollars a year and making it impossible for South Korea to meet its Paris climate commitments as older nuclear power plants retire around 2030.28

Even in Sweden, political winds are blowing against nuclear power. A new government took over that included the Green Party in its coalition, and several reactors are being retired ahead of their useful lives.29 If Sweden followed Germany and rapidly shut down its nuclear power stations, the results would be dramatic. According to a recent study, even with Sweden’s extensive hydropower, the intermittent nature of wind and solar would force the country to install a large amount of excess capacity. To meet demand of about 150 terawatt-hours per year, wind and solar production of more than 400 TWh would be needed, along with grid upgrades. The cost of electricity would increase fivefold. Alternatively, the amount of new wind and solar could be cut in half—still greatly increasing electricity costs—by using fossil fuel as backup for the intermittent sources. But this would increase carbon emissions.30

A better solution would be to increase Sweden’s nuclear power output to decarbonize its transportation fleet and export clean energy to northern Europe’s grid to displace German and Polish coal.