Iran to Pakistan

Iran

The main Alpine mountain belt turns sharply south-eastwards from Eastern Turkey into Iran, where it divides into two branches. The more southerly becomes the Zagros Range, which continues along the Iraq–Iran border and the northeast side of the Persian Gulf to the Straits of Hormuz – a distance of around 1300km (Figs 7.1, 7.2). The Zagros Range is an impressive mountain belt, rivalling the Western Alps in scale, being 400km wide in the northwest to over 600km in the southeast. Much of it is over 3000m in height, with several peaks over 4000m, the highest being Zard Kuh (4548m) in the central part of the Zagros. The southeastern end of the Zagros Range ends abruptly at the Straits of Hormuz, and east of this is a narrow arcuate mountain range facing out towards the Gulf of Oman. This region is known as the Makran and extends eastwards into southwest Pakistan.

The northern branch of the Alpine belt in Iran is the Alborz Range, which curves around the southern side of the Caspian Sea, and is much narrower, only 60–130km wide, but is even higher and contains the highest mountain in Iran, Damavand, at 5604m. The eastern end of the Alborz Range merges into a broader belt of mountains, the Kopeh Dagh, that follow the northeastern border of Iran and extend into northern Afghanistan, where they eventually join the Hindu Kush.

The Zagros and Alborz mountain ranges are separated by the vast Central Iranian Plateau, which is roughly triangular in shape, broadening to nearly 400km width in the centre. The northwestern part of the plateau is known as the Dasht-e-Kavir, or ‘Great Salt Desert’, and the southern as the Dasht-e-Lut. The whole plateau is over 400m in height, is completely enclosed by mountains, and contains many seasonal salt lakes and marshlands. A third belt of mountains runs along the Iran–Afghanistan border, forming the eastern side of the Central Iranian Plateau.

Figure 7.1 The Zagros and the Makran. Note that the Zagros Range bordering the Arabian Plate is separated from the Alborz Range in the north by the Central Iranian Plateau. The Turan Block north of the Alborz is part of the Eurasian Plate. AP, Afghan Plateau. © Shutterstock, by Arid Ocean.

Figure 7.2 Major tectonic features of Iran. HZF, High Zagros Fault; KF, Kazerun Fault; MFF, Main Frontal Flexure; MZT, Main Zagros Thrust; ZMF, Zendan-Minab Fault. As, Ashkhabad; Az, Azerbaijan; B, Bushehr; BA, Bandar Abbas; Hb, Hajiabad; Te, Tehran. D, Damavand; ZKV, Zard Kuh. After Paul et al., 2010.

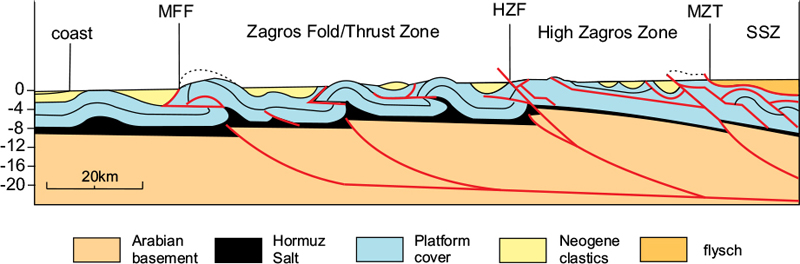

The Zagros Belt

Compared to most of the Alpine belts discussed so far, the Zagros belt is comparatively simple in its basic structure. It is the product of the collision between the Arabian Plate in the southwest and the Iranian Terrane, or microplate, in the northeast. There are three tectonic zones: the Zagros Fold-Thrust Zone on the southwest side of the belt, the High Zagros Zone in the centre, and the Sanandaz–Sirjan, or Internal, Zone to the northeast (Figs 7.2, 7.3).

The stratigraphic sequence in the Zagros belt consists of between 6 and 15km of sedimentary strata overlying a Precambrian metamorphic basement. The sedimentary sequence consists of Palaeozoic, mainly clastic, sediments overlain by Mesozoic to Palaeogene massive carbonates, then finally Miocene to Recent molasse. At the base of the sequence in the southeast is a thick layer of salt, the Hormuz Salt, which provides an important décollement surface for the larger folds and is the dominant factor controlling the fold style in the southern part of the Fold-Thrust Zone (Fig. 7.3).

The Zagros Fold-Thrust Zone

This zone is a typical thin-skinned fold-thrust belt, affecting mainly the sedimentary platform cover of the passive margin of the Arabian Plate. The zone is bounded to the northeast by the High Zagros Fault, which separates it from the High Zagros Zone. The outer margin of the Zagros Fold-Thrust Zone is defined by the Zagros Deformation Front, which lies some distance within the Arabian Platform in the northern sector and continues offshore within the Persian Gulf in the south. Between these two lineaments is the Mountain Front Flexure, which defines the outer margin of the more strongly folded part of the zone and marks the edge of the coastal plain in the north. The Fold-Thrust Zone is divided into two sectors by the N–S Kazerun Fault, a dextral wrench fault, which displaces the Mountain Front Flexure by about 150km, from the northeastern margin of the coastal plain to the coast at Bushehr.

Figure 7.3 Cross-section through the Folded Zagros Zone, from Bandar Abbas to Hajiabad. Note the role of the Hormuz salt as a décollement layer. The size of the folds is dependent on the thickness of the platform cover, which consists of c.4km of Cambrian to Eocene sediments dominated by carbonates. The section is 160km long. HZF, High Zagros Fault; MFF, Mountain Front Flexure; MZT, Main Zagros Thrust; SSZ, Sanandaj-Sirjan Zone. After Regard et al., 2010.

The southern sector of the Fold-Thrust Zone, known as the Fars Arc, faces south towards the Persian Gulf and contains some of the more spectacular fold structures of the Zagros Belt. When flying over this section of the Zagros by commercial airline, it is possible to see the individual anticlinal structures clearly, as they form prominent mountain ridges. As illustrated in Figure 7.4, these anticlines are actually anticlinal periclines, shaped like upturned canoes, and only persist for relatively short distances (e.g. 20–30km) along strike. Figure 7.3 is a cross-section through part of the Fold-Thrust Zone, showing how the shape and size of the folds are controlled by the thickness of the carbonate sequence above the basal salt layer, which acts as a décollement surface.

The High Zagros Zone

This consists of highly deformed Mesozoic metamorphic rocks and is bounded to the northeast by the Main Zagros Thrust, more precisely a reverse fault, which has been shown from seismic evidence to dip northeastwards beneath the Central Iranian Massif, and represents the plate boundary between the Arabian and Iranian plates. The zone is bounded in the southwest by the High Zagros Fault, which separates it from the Fold-Thrust Zone. The highest part of the mountain belt, which includes Zard Kuh, lies immediately northeast of this fault.

Figure 7.4 Periclinal anticlines in the Fars Arc, southern Zagros Mountains. This is a thermal image. The mountain ridges (in red) are formed along the crests of anticlines, exposing carbonate strata, the red colour indicating the presence of vegetation; the valleys (paler colour) are filled with younger sediments and are more arid. The coast of the Persian Gulf is visible at the bottom of the image. The folds are several tens of kilometres long and around 10km across. © Science Photo Library

This is the internal metamorphic complex of the orogenic belt and consists of an outer series of thrust slices containing deep-marine sediments, ophiolites and volcanics, and an inner belt of highly deformed late Palaeozoic to Mesozoic platform sediments originating on the passive margin of the Iranian Terrane. The zone is bounded on its northeast side by the Central Iranian Massif and represents that part of the Massif that lies within the Zagros tectonic belt and has been affected by the Alpine deformation.

Tectonic history

Rifting beginning in the late Permian to early Triassic resulted in the separation of the Iranian Terrane, part of the large composite Cimmerian Terrane, from the Arabian margin of Gondwana. Cimmeria moved northwards towards Eurasia during the Jurassic, driven by subduction of the Palaeo-Tethyan Ocean crust, and finally collided with the southern boundary of Eurasia during the late Triassic to early Jurassic.

Subduction of the Neo-Tethyan Ocean crust beneath the Iranian Terrane took place during the late Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods and reached a maximum in the late Cretaceous, resulting in the formation of a magmatic arc along the southwest edge of the Central Iranian Massif. Final collision between Arabia and the Iranian Terrane occurred in the Miocene Epoch, and convergence is still taking place at a rate of 5–10mm/a, accompanied by many major earthquakes. It has been estimated that about 59km of shortening (23%) has taken place to date across the southern part of the Zagros.

The Central Iranian Plateau

The vast region of the Central Iranian Plateau, measuring about 1100km in length and 400km across at its widest part, is completely surrounded by mountains: the Zagros in the southwest, the Alborz and Kopeh Dagh in the north, and the East Iran Belt in the east. Although much of the Plateau consists of flat arid plains with many seasonal salt lakes, there are considerable mountainous areas as well, including the peak of Kuh-e Darband, at 2499m.

In geological terms, the plateau, or Central Iranian Massif, is part of the large composite Cimmerian Terrane (Cimmeria), which is the south-eastwards continuation of the Anatolian–Tauride Zone discussed in the previous chapter, and is thought to have separated from Gondwana in the late Permian to early Triassic. It is composed of large Cenozoic sedimentary basins separated by uplifted massifs of metamorphosed basement rocks consisting of gneisses overlain by Mesozoic metasediments. The basins contain up to 4km of post-Eocene evaporites, carbonates and shales.

The Massif hosts large quantities of igneous material in two distinct categories: the earlier suite is mainly of Eocene age and is related to the north-eastwards subduction of the Neo-Tethyan ocean lithosphere; it is concentrated in the Urumiyeh–Dokhtar belt along the southwest margin of the plateau, bordering the Zagros Belt. The younger suite consists of post-collisional volcanics of Oligocene to Quaternary age scattered across the plateau.

Both the crust and mantle lithosphere of the plateau are much thinner than the adjoining mountain belts and exhibit a higher heat flow. These characteristics are attributed to a phase of mid-Miocene post-orogenic thinning and uplift, similar to that of other Alpine metamorphic core complexes, caused by the processes of trench roll-back and slab break-off described earlier.

The Northern Ranges

The Alborz

The Alborz Mountains form a well-defined, narrow, south-facing arc around the southern end of the Caspian Sea, and define the northeastern boundary of the Central Iranian Plateau. They are the Iranian continuation of the Lesser Caucasus Range of Armenia and Azerbaijan (see Fig. 6.15). The Alborz belt is mainly composed of a sedimentary sequence of Devonian to Oligocene age, dominated by Jurassic carbonates, and by late Cretaceous to Eocene volcanics resulting from the subduction of Tethyan oceanic lithosphere beneath the Iranian Terrane. This stratigraphic sequence was deformed during the Miocene collision between the Iranian Terrane and the Arabian Plate, which continued into the Pliocene.

The Kopeh Dagh

The southern part of the Kopeh Dagh Mountains, known as the Binalud Range, is the eastern extension of the Alborz Range and forms the northeastern boundary of the Iranian Plateau, separating Iran from Turkmenistan to the north. The range extends in a southeasterly direction from the end of the Alborz to the border with Afghanistan. The northern section of the Kopeh Dagh strikes north-westwards towards the Caspian Sea coast at Krasnowordsk, and if this line is continued across the Caspian Sea to Baku, it reaches the southeast end of the Greater Caucasus. This NW–SE line thus marks the geological margin of the pre-Mesozoic Eurasian continent. There are three parallel ranges within the Kopeh Dagh, each containing peaks over 3000m in height, the highest, at 3314m, in the Binalud Mountains.

The Alpine tectonic history of the Alborz–Kopeh Dagh belt commenced with the Cimmerian Orogeny in the late Triassic to early Jurassic, which resulted from the closure of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean. This was followed by a major extensional event in the mid-Jurassic producing a rift basin in which over 7km of Mesozoic sediments were deposited. The main orogenic phase, which caused the folding, thrusting and uplift of the fold belt, occurred in the late Eocene Epoch as a result of the Arabian–Iranian plate convergence further south in the Zagros. The major fold and thrust structures of the Kopeh Dagh are parallel to the suture defining the margin of Eurasia and are probably, in part, inherited from earlier Mesozoic structures. The last significant tectonic event occurred during the Pliocene, as the region was subjected to dextral wrench faulting due to the now oblique nature of the Arabian–Iranian convergence.

Tectonic summary

The Alpine orogenic belt of Iran differs in scale from the Mediterranean belts discussed in previous chapters, mainly because it resulted ultimately from the collision of two large continental plates. Consequently, whereas the Mediterranean belts have experienced histories that involved the subduction of Tethyan and Neo-Tethyan oceanic lithosphere, and the accretion of small terranes, the final collision of Africa and Eurasia has not yet occurred and there are still large marine areas within the overall belt underlain by oceanic or thinned continental crust. In contrast, the whole of the Iranian belt has experienced the effects of the final Arabian–Iranian collision, which has transmitted the contractional stress resulting from the Zagros collision through the Iranian terrane to the old Mesozoic suture zone at the Eurasian margin to form the northern fold belts. Slab roll-back at the Arabian margin has ceased, and the extensional region originally formed above the subduction zone is now an elevated plateau.

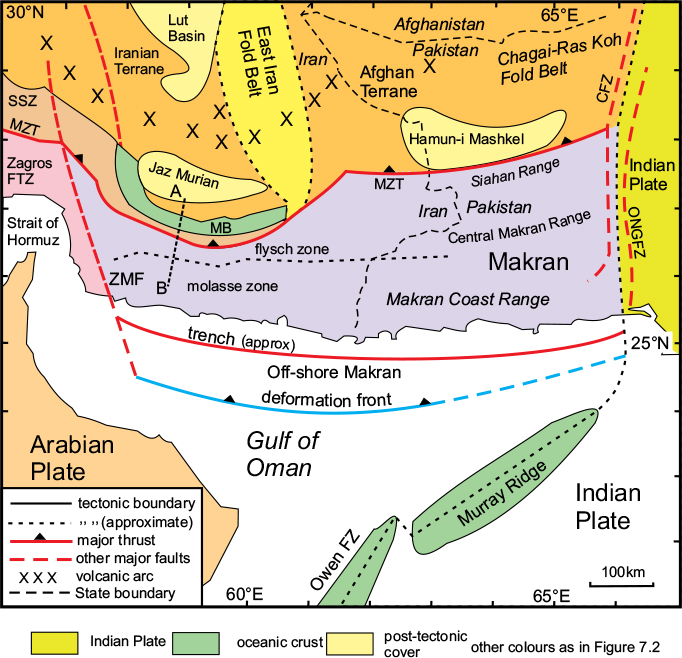

The Makran

The southern branch of the Alpine–Himalayan mountain belt continues eastwards from the Strait of Hormuz at Bandar Abbas along the northern side of the Gulf of Oman (Fig. 7.1). Here the mountain belt divides into two: a narrow northern arc, including two peaks over 3000m in height, forms the northern border of a central plateau, and a broader southern belt, known as the Makran, lies on the southern side. Topographically, the Makran belt in Iran consists of a high mountain ridge in the north, fringed by lesser hills to the south, sloping down towards the coast.

The Iranian sector of the Makran is about 550km long and extends eastwards along the north side of the Arabian Sea into the Baluchistan Province of Pakistan for a further 450km (Fig. 7.5). There are three arcuate mountain ranges within the Pakistani sector of the Makran Belt: the Siahan Range in the north, and the Makran Coast Range in the south, with the Central Makran Range between them. Only the latter two ranges include mountains over 2000m, and the belt as a whole is much less impressive than the Zagros.

Another mountain range strikes N–S along the border between Iran and Afghanistan, and sweeps round to join the Baluchistan ranges. This range, named the East Iran Belt in Figures 7.2 and 7.5, marks the boundary between the stable Iranian Massif in the west and the similar Afghan Terrane to the east in Afghanistan. A chain of late Cretaceous ophiolite outcrops and several major dextral wrench faults within this belt indicate there has been significant relative movement between the two stable blocks.

Plate-tectonic context

The western end of the arcuate Makran belt joins the eastern end of the Fars Arc, and the cusp where the two arcs meet, at the Strait of Hormuz, marks the point where the Arabian–Iranian plate boundary changes from a collisional suture to a subduction zone (Figs 7.1, 7.5). The Makran thus represents an accretionary complex resulting from the subduction of the oceanic part of the Arabian Plate beneath the Iranian and Afghan continental terranes to the north. A broad zone of dextral wrench faults, the Zendan–Minab fault system, links the end of the Main Zagros Thrust with the Makran Trench, which lies offshore in the Gulf of Oman. The individual structures of the Zagros Belt end at this lineament and are replaced by the separate fold-thrust structures of the Makran belt.

The Iranian Makran

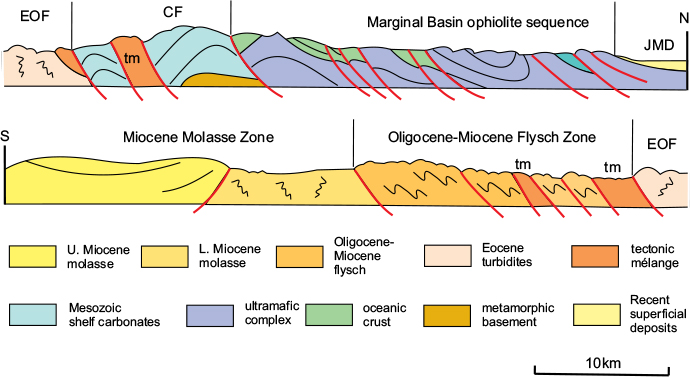

The on-shore sector of the Iranian Makran occupies a 150km-wide belt between the Jaz Murian Depression at the southern end of the Central Iranian Plateau and the coast, and can be divided into five tectonic zones (Figs 7.5, 7.6). From north to south, these are as follows.

Figure 7.5 Main tectonic features of the Makran. CFZ, Chaman Fault zone; MB, marginal basin; MZT, Main Zagros Thrust; ONGFZ, Ornach-Nal Ghazaband Fault zone; Owen FZ, Owen Fracture Zone; ZMF, Zendan-Minab Fault zone; Zagros FTZ, Zagros Fold-thrust Zone. After McCall et al., 1982.

Figure 7.6 Structure of the onshore Makran. North–south section across the Iranian Makran along line A–B of Fig. 7.5 showing the main tectonic units. JMD, Jaz-Murian Depression; MB, Marginal Basin sequence; CF, Carbonate Fore-arc Zone; EOF, Eocene–Oligocene Flysch Zone; OMF, Oligocene–Miocene Flysch Zone; TM, tectonic mélange. After McCall et al., 1982.

1The marginal basin, containing Jurassic to Palaeocene ophiolites and deep-marine sediments.

2The carbonate fore-arc: a narrow zone of Palaeozoic metamorphic basement, known as the Bajgan-Durkan, the eastward continuation of the Sanandaz–Sirjan zone of the Zagros, with a Mesozoic platform cover.

3The ophiolitic tectonic mélange zone, marking the continuation of the suture between the Arabian and Iranian plates (the Main Zagros Thrust).

4The inner flysch zone, containing thick Eocene to Oligocene flysch.

5The outer flysch zone, containing Oligocene to Miocene flysch.

6The molasse zone, containing Miocene to early Pliocene shallow-marine molasse.

The structure of zones 4–6 of the on-shore Makran, south of the suture zone, is dominated by steep north-dipping reverse faults separating south-facing overfolds, which is typical of a subduction–accretion complex.

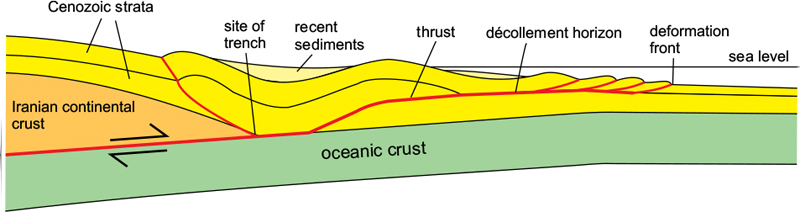

Figure 7.7 The Makran accretionary prism: a much simplified illustration of the structure. Note that the thrust-generated folding has progressed seawards from the original site of the trench and has also elevated the on-shore Makran. The thrusts have utilised a décollement horizon within the sedimentary sequence. After Platt et al., 1985.

The offshore sector of the Makran consists of a series of anticlinal ridges separated by narrow elongate basins (Fig. 7.7). The original topographic trench has been completely obscured by a 6–7km-thick pile of sediments that cover the oceanic crust. However, only the uppermost 2½km of sediment has apparently been involved in the folding that must overlie a décollement layer.

The subduction zone has been shown to dip north at a very shallow angle of c.10° and the subduction-related volcanic arc, consisting of a chain of Cenozoic volcanoes, lies 400–500km north of the coast. The estimated convergence rate is about 50mm/a, and the zone is still seismically active.

Tectonic History

The marginal (back-arc) basin now represented by the ophiolite complex developed on the southern side of the Central Iranian Plateau during the Jurassic, and remained active until the Palaeocene in response to the subduction of Arabian oceanic crust beneath the Iranian micro-plate. The development of this basin resulted in the isolation of the narrow Bajgan-Dur-kan basement terrane on its southern side. A subduction-related volcanic arc was created along the southern part of the Central Iranian Plateau.

The accretionary complex developed throughout the Cenozoic, forming two thick flysch sequences: Eocene to Oligocene, and Oligocene to Miocene, with an estimated total thickness of over 10,000m. A major compressional event in the late Miocene caused folding and thrusting throughout the on-shore Makran, including the closure and disruption of the back-arc basin, and the uplift of the Palaeogene flysch sequences. This event was probably related to the collision between the Arabian Plate and Iran in the Zagros Belt to the west, which also resulted in a change in convergence direction across the plate boundary.

Convergence continued in the Makran through the Pliocene and into the Pleistocene. The deformed Palaeogene sequences in the southern part of the zone were overlain by shallow-marine clastic sediments of molasse type. Sedimentation continued off-shore into the Gulf of Oman and was gradually added to the increasing accretionary prism. Deformation has continued to the present day in the offshore Makran as the deformation front, which is still active, migrated southwards to its present position about 150km from the coast.

Afghanistan

The northern part of Afghanistan consists of a large area of elevated ground, over 1000m in height, crossed by many individual mountain ranges that increase in height and coalesce eastwards towards the impressive Hindu Kush Range in the northeastern corner of the country (Figs 7.1, 7.8). Much of the Hindu Kush is over 2000m in height and includes the Kuh-i-Baba Range, at over 5000m, west of Kabul. The highest point in the Hindu Kush is the peak of Tirich Mir (7708m) which is situated across the border in Pakistan. Here, the eastern end of the Hindu Kush Range merges with the Pamir Mountains of Tajikistan, and from there the mountain belt continues south-eastwards as the Karakoram Range. These mountains are the eastern continuation of the northern ranges of Iran described above, and define the northern margin of the Alpine–Himalayan orogenic belt. North of these mountains is the low-lying desert region of Turkmenistan, which extends west towards the Caspian Sea and northwards into Uzbekistan.

South of the mountains is the flat and relatively featureless region known as the Helmand Basin, which consists mostly of arid desert, and continues southwards into the northern Makran.

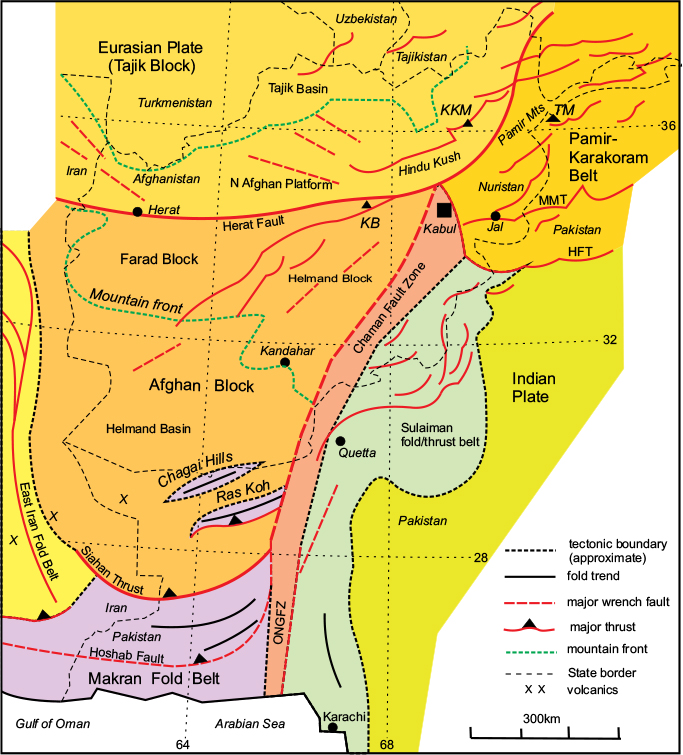

Figure 7.8 Major tectonic features of Afghanistan and adjacent areas. HFT, Himalayan Frontal Thrust; MMT, Main Mantle Thrust; ONGFZ, Ornach–Nal–Ghazaband Fault Zone. Cities: Jal, Jalalabad; Mountains: KB, Kuh-i-Baba; KKM, Kuh-e Khrajeh Mohammad; TM, Tirich Mir. Colours as in Figures 7.2 and 7.5. After Mahmood & Gloaguen, 2012.

The Afghan Block

Most of Afghanistan lies within the Afghan Block – a terrane which, like the Iranian Terrane, is sandwiched between the Zagros–Makran belt in the south and the Eurasian Plate in the north (Fig. 7.5). The Afghan Block is part of the Cimmerian Super-terrane, and consists of Palaeozoic basement of Gondwanan origin overlain by Jurassic and Cretaceous sedimentary cover. The western boundary of the block is defined by the East Iran Fold Belt, which is a complex zone of dextral wrench faulting produced by relative movements between the stable Iranian and Afghan blocks during the Alpine collision with Arabia. The eastern boundary of the Afghan Block is a major sinistral fault zone that is part of the western transform boundary of the Indian Plate. The northern part of this fault zone is known as the Chaman Fault Zone and the southern as the Ornach–Nal–Ghazaband Fault Zone. East of the fault zone is the complex Sulaiman fold-thrust belt involving the sedimentary cover of the Indian Plate, discussed in the next chapter.

The northern boundary of the Afghan Block is defined by the Herat Fault system, which traverses northern Afghanistan from the Iranian border west of Herat, eastwards to the Hindu Kush mountains north of Kabul, and from there turns north-eastwards into Tajikistan. This zone marks the suture between the Afghan Block and the Tajik Block to the north, which is part of the Eurasian Plate. It resulted from the subduction of Palaeo-Tethys Ocean crust beneath Eurasia during Triassic and Jurassic times, followed by collision at the beginning of the Cretaceous. The Afghan Block itself is an amalgamation of four separate terranes during the early Cretaceous: the Farad Block and the Helmand Block form the main part of the Afghan Block plus two small terranes, the Pamir and Nuristan Blocks, in the northeast corner. The suture zones between these terranes became reactivated during the Alpine compressional event in the Makran Belt and were also affected by the oblique convergence of the Indian Plate. The result of these two processes was the creation of the 700km-wide zone of mountains in eastern Afghanistan, where the northern and southern branches of the Alpine–Himalayan orogenic belt meet at the Chaman Fault Zone (see Fig. 7.8).

The Chagai Fold Belt

There are two small isolated mountain ranges in the southern part of the Afghan Block, near the Afghanistan–Pakistan border, the Chagai and Ras Koh Hills. These are essentially broad anticlines that are related to the Neogene deformation further south in the Makran, but are separated from the remainder of the Makran structures by the broad Hamun-i-Mashkel depression (see Figs 7.3, 7.5).