| 1 |  |

1945 |

“In the great world drama involving the destiny of civilization which is moving toward a climax, New York has become the center—the core—of the democratic system, carrying in its vitals germs which may threaten social disintegration, but also the seed of larger and better growth.”1 So wrote Cleveland Rodgers, a New York City planning commissioner, in 1943. With London and Berlin in ruins and Paris humiliated and defeated, New York City was the hope of the world, the place where the democratic system would thrive or falter, where social disintegration would destroy civilization or yield to enlightened policy. Moreover, the same could be said of American cities in general. As the United States approached victory in World War II, there was great hope and great trepidation about the future of American cities. The United States was an urban nation, and if triumphant Americans were to succeed in their mission to sell democracy and capitalism to the largely ruined remainder of the world, the cities would have to overcome their problems and demonstrate unquestionably the nation’s greatness. With the defeat of European fascism and Japanese imperialism, New York City and its lesser urban compatriots were at the top of the world, but they had to confront their problems and create an even better future.

As war-induced prosperity dispelled the economic depression of the 1930s and American forces triumphed in the battlefield, there was a good deal of optimism that the nation’s cities were up to the challenge facing them. Despite concerns about blight and decay in the older cities and racial conflict throughout the nation, urban leaders were drafting realistic plans to remedy metropolitan ills. In a publicity booklet the Bankers Trust Company expressed the mood of 1945 when it presented New Yorkers as a people “to whom nothing is impossible.” According to the Wall Street firm, “New York has made up its mind … New York won’t wait.”2 Neither would Chicago, Saint Louis, Dallas, or Los Angeles. America’s cities were poised for action.

Downtown

At the center of the dynamic American cities of 1945 was downtown. Downtown’s dominance within the metropolis was universally recognized, and most knowledgeable observers believed that a viable city had to have one command center. A southern California economist wrote in the early 1940s: “Logically, it would seem that every metropolitan organism or area must have a focal government, social, and business center, a heart, a core, a hub from which all or most major functions are directed.” Moreover, without a healthy, beating heart, a metropolis, like a human being, would sicken and possibly die. “The degree of success attained by Southern California in economic, social, and political spheres,” the economist observed, “is directly dependent upon the soundness and strength of the metropolitan nerve center.”3 Although widespread use of automobiles in the 1920s and 1930s had threatened downtown supremacy and raised the specter of decentralization, the success of a city still seemed to depend on the success of its downtown. In the minds of most urban commentators of the mid-1940s, downtown was the heart of the city, pumping necessary vitality to all the extremities of the metropolitan region.

Basic to the circulatory system of a healthy city was the centripetal transportation system. In 1945 the arteries of transport focused on downtown and funneled millions of Americans to the urban core. Railroads still provided a major share of long-distance intercity transport, and soldiers and sailors coming back from the war generally returned via rail. The rails converged on the urban hub, bringing millions of young veterans to giant downtown terminals from which they would pour into the streets of the central business district. With a soaring vault and noble columns, Pennsylvania Station in midtown Manhattan was patterned after the great Roman Baths of Caracalla and proclaimed to incoming passengers that they had arrived at the imperial city of the Empire State, a metropolis worthy of the corporate caesars of twentieth-century America. Nearby, New York City’s Grand Central Terminal became synonymous with the bustling, jostling crowds so characteristic of the dynamic urban core. The Union Stations in Washington, D.C., Chicago, Saint Louis, Los Angeles, and other cities across the nation were likewise monumental midtown structures, great spaces that announced to travelers that they were in the heart of a vibrant metropolis. Although air terminals existed in fringe areas, the downtown rail depots were still the primary front door of the city, the place where wartime Americans arrived and departed from the metropolis.

Public transit lines also converged on the downtown, feeding a mass of humanity into the urban hub. In fact, the concentration of commerce in the downtown area was largely a product of the centripetal transit system that had developed during the century before 1945. The streetcar, subway, elevated rail, and bus lines all led to the central business district, making that area the most accessible to employees and customers dependent on transit and most desirable to businesses dependent on those workers and shoppers. As the number of automobiles soared during the 1920s, reliance on streetcars declined and the prospects for downtown-centered public transit worsened. The economic depression of the 1930s, however, slowed auto sales, and gasoline and tire rationing during World War II forced many Americans back on the trolleys and buses carrying commuters and customers downtown. The number of transit passengers soared from 13 billion in 1940 to over 23 billion in 1945.4 In 1944 the annual per capita ridership was more than 420 in cities with a population of over 500,000; the figure was 372 for cities in the 250,000 to 500,000 population category.5 The streetcar or bus was not a little-used alternative to the automobile; it was an everyday necessity. And nowhere was the web of transit lines denser than downtown. The lines were designed to carry as many people as possible to the urban core, and in 1945 they were doing so.

Among the transit passengers were millions of office workers, for downtown was the office district of the metropolis. In fact, downtown was virtually synonymous with office work; all major offices were in the central business district. Every lawyer, accountant, advertising agency, or other business service of any repute had offices downtown. Corporate headquarters clustered downtown, as did all the major banks. The economic depression of the 1930s had reinforced downtown control of finances by eliminating many of the weaker neighborhood financial institutions that had been potential competitors to the central business district banks. Many medical doctors and dentists maintained offices close to their patients in the outlying neighborhoods, but otherwise going to the office meant going downtown. In major cities throughout the nation, gender defined the ranks in the corps of office workers; an army of male managers and professionals and female secretaries migrated each day to the urban core to earn their living.

The preeminent symbols of the office culture were the soaring skyscrapers. These behemoths not only reminded observers of the monumental egos of their builders, but also were tangible evidence of the inflated property values in the urban core. So many people desired to do business in the hub of the metropolis that downtown land values far surpassed those elsewhere in the city. To make a profit from their valuable plots of land, property owners consequently had to build up rather than out. Only layer on layer of rentable space would compensate property owners for their investment in an expensive downtown lot. Vertical growth became a necessity and visibly marked downtown as the real-estate mother lode of the metropolis.

Nowhere were the skyscrapers so tall or so numerous as in New York City. It was the preeminent high-rise metropolis, where vertical movement was as significant as horizontal. In 1945 it could boast of 43,440 elevators, or 20 percent of all those in the nation. They carried 17.5 million passengers each day in trips totaling 125,000 miles, half the distance to the moon. New York’s RCA Building claimed to have the fastest elevators in the world, transporting urbanites at the rate of 1,400 feet per minute, or two floors per second.6 There were as yet no automatic elevators; instead, operators ran each car in the vertical transport system. When the city’s elevator operators went on strike for six days in September 1945, New Yorkers became especially aware of the vertical nature of their existence. The strike affected 1,612,000 workers, equal to almost one-quarter of the city’s population, most of whom were unable to get to their jobs in the city’s multistory structures. Although rain, snow, and sleet could not stay letter carriers from delivery of the mail, flights of stairs could. Thousands of parcels and letters piled up that could not be taken to offices on upper floors.7 One stenographer expressed the attitude of many when she told her boss: “I’m not going to walk up. It’s not good for my constitution.”8 The skyscraper city simply could not exist without the vertical modes of transit.

Surpassing all other office towers in New York City and the world was the Empire State Building, rising 1,250 feet and 102 stories. The Chrysler Building also exceeded the 1,000-foot mark, ranking second among the city’s skyscrapers. The most significant high-rise development, however, was Rockefeller Center in midtown Manhattan (figure 1.1). Constructed during the depressed 1930s, this complex of office towers, theaters, stores, and restaurants inspired downtown developers throughout the nation during the half century following World War II. Not only did it offer millions of square feet of leasable commercial space, but its gardens, sculpture, murals, skating rink, and giant Christmas tree display offered an oasis of civilized living in the congested core of the city. It was a landmark that many other cities would attempt to copy when redeveloping their downtowns. Yet none would match the success of Rockefeller Center.

New York City did not have a monopoly on skyscrapers. Each major American metropolis boasted a skyline that proclaimed the city’s success and identified to anyone approaching the urban area the location of its commercial hub. Clevelanders did not let rivals forget that their 708-foot Terminal Tower was the tallest building outside New York City. At 557 feet, the Penobscot Building was the most prominent skyscraper in Detroit. One block to the south, the exuberant Art Deco Guardian Building rose thirty-six stories, punctuating the Motor City skyline and earning the title of “cathedral of finance.”9 The Foshay Tower, Rand Tower, and Northwestern Bell Telephone Company Building provided Minneapolis with a respectable skyline advertising the city’s commercial prominence, and in Kansas City, Missouri, the Power and Light Building and Fidelity Bank and Trust Company proclaimed the metropolitan status of that midland hub. Similarly, Dallas and San Francisco could each boast of two buildings over 400 feet in height, symbols of urbanity in the South and West. Although modest by the standards of the early twenty-first century, the skylines of 1945 were clear indicators that downtown was the single dominant focus of metropolitan life.

FIGURE 1.1 The vertical city: Rockefeller Center, New York. (Library of Congress)

Perhaps second only to the office towers as commercial landmarks were the giant downtown department stores. During the 1930s and early 1940s, urbanites bought their groceries and drugs in neighborhood stores, but for department store shopping and the purchase of apparel and accessories, the central business district was the place to go. From 1935 to 1940, downtown Philadelphia accounted for 35 to 36 percent of all retail sales, but in 1935 it held a 72 percent share of the general merchandise category, the merchandise sold at department stores.10 Downtown had the greatest selection of goods and the latest fashions. For anything but the basics, smart shoppers headed to the center of the city.

Most of these smart shoppers were women. The downtown department store catered to women and did everything possible to attract their patronage. The motto of Chicago’s giant Marshall Field store was “Give the Lady What She Wants,” but every department store executive in cities across the country shared this attitude.11 With millions of American men in the military and thus unable to staff the nation’s factories and offices, the number of female workers rose markedly during World War II. Yet the traditional, and still significant, economic sphere of women was consumption rather than production. Women were the shoppers, and the downtown department store was their mecca, the place to meet friends over lunch and buy the goods their families needed. This was especially true of middle-and upper-middle-class women who donned their good clothes, complete with requisite hat and gloves, and frequently made the trek to the core of the city. A study from the mid-1930s found that more than half of the women from Cleveland’s upper-middle-class suburb of Shaker Heights went downtown at least once a week to shop.12 The great downtown department store was to many women what Wall Street was to the stockbroker, a bulwark of their existence. On the day the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, a matronly shopper from Chicago reportedly exclaimed: “Nothing is left any more, except, thank God, Marshall Field’s.”13

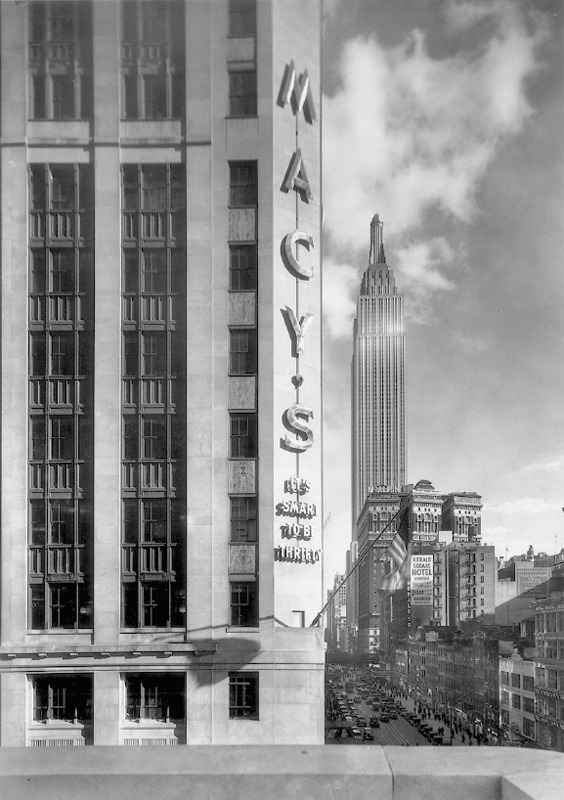

FIGURE 1.2 With the world’s largest department store and the world’s tallest building Manhattan was the unrivaled hub of the world in 1945.(Library of congress).

Marshall Field’s, however, was only one of many giant emporiums attracting shoppers to the nation’s central business districts. Macy’s in New York City was the largest department store in the nation (figure 1.2). On 6 December 1945 it recorded $ 1.1 million in sales, believed to be the largest amount for one day in any store in the world when there was no special promotion to boost business.14 Filene’s in Boston, Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia, and J. L. Hudson Company in Detroit were all renowned as downtown merchandising giants. Cleveland’s May Company claimed to be the largest department store in Ohio, with seventeen acres of floor space, although it had a number of downtown competitors, including Higbee’s, Halle Brothers, and the Bailey Company. On the West Coast, Bon Marché and Frederick and Nelson vied for business in the center of Seattle, and the Emporium was the largest store in downtown San Francisco. Although offering a more limited range of merchandise than Macy’s or Marshall Field’s, Neiman-Marcus in downtown Dallas enjoyed an enviable reputation as a purveyor of fashionable apparel and accessories. Each September throughout the war, the elegant retailer drew spectators to its annual Fashion Exposition Show. In September 1944, while American soldiers were marching toward Germany, Neiman-Marcus was informing American women that this was the year of “more hat, less shoe,” “tailored gold jewelry,” and the “flaring tunic suit.”15

Women who could not afford gold jewelry would have felt uncomfortable in the precincts of Neiman-Marcus, but most of the largest department stores attempted to cater to a wide range of income levels. The basement store or budget shop offered merchandise for bargain hunters and the less affluent, who could not afford the goods on the higher floors of the emporium. Depending on the store and the locality, African Americans might be excluded or accepted. In a study of racial segregation published in 1943, a black sociologist reported that Atlanta’s largest department store had “no restrictions on dealings with Negroes and makes no racial distinctions, except for the special rest room for Negro women which is located in the basement.” According to this researcher, “Negroes are allowed credit, may use fitting rooms, and may try on any piece of apparel.”16 Many downtown stores in the South and its border states were not so broadminded. In Baltimore, most of the principal department stores shunned African Americans. Only one downtown department store allowed blacks to try on hats and dresses. Baltimore’s May Company channeled all blacks to the basement store, not wanting them to browse or be seen on the upper floors. “I ain’t been downtown for over five years,” reported one black woman in Baltimore. “I know they don’t want Negroes, and I ain’t one to push myself on them.”17

In northern cities, the major department stores generally served African Americans, especially if they appeared able to afford the merchandise. New York City department stores had even begun to hire African American salespeople.18 In Chicago, however, a campaign in 1943 and 1944 to encourage the downtown department stores to hire black saleswomen proved largely unsuccessful.19 Throughout the United States, “untidy” women of either race might be discouraged from trying on garments, but generally the largest downtown stores drew on a wide range of clientele from throughout the metropolitan area. Even if one felt excluded and never shopped downtown, the big central stores influenced what one wore and bought. They set the style trends for stores in the neighborhoods as well as in the core. Neiman-Marcus determined what was fashionable even for women who would never enter the store.

Although the downtown giants remained dominant, there was concern about the decentralization of retailing. In the late 1920s, Marshall Field’s opened branch stores in the suburbs of Evanston, Oak Park, and Lake Forest.20 Cleveland’s Halle Brothers pioneered the creation of outlying stores, launching five branches in 1929 and 1930. During those same years, a Halle competitor, the Bailey Company, established an East Side store at 101st Street and Euclid Avenue and a West Side branch in the suburb of Lakewood.21 In the New York region in 1937, Peck and Peck launched a branch in suburban Garden City on Long Island and the next year opened a branch in the elite Connecticut suburb of Greenwich. In 1941 Bonwit Teller expanded into Westchester County, opening a store in White Plains, and the following year Best and Company tapped the increasingly lucrative suburbs with new stores in Manhasset, White Plains, and Bronxville. From 1937 through 1942, New York City retailers opened a total of twenty-four outlying branch stores.22 Moreover, immediately following the declaration of peace in 1945, Macy’s announced plans for branches in White Plains and in Jamaica on Long Island.23 Explaining these expansion plans in early 1946, the vice president of Macy’s observed that “branch units of centrally located department stores are the inevitable result of heavy traffic congestion in downtown shopping areas and the growth of population in the suburbs.”24 Most major downtown department stores had eschewed branch development, believing that branches were a nuisance to manage and only drained business from the downtown flagship store, which was the principal magnet for shoppers because of its unequaled selection of goods. Many retailers in fact were preparing to invest large amounts in their downtown outlets; in its New Year’s message for 1946, Neiman-Marcus announced plans for a $1 million expansion of its store in the heart of Dallas.25 Yet the words of Macy’s vice president were ominous for downtown retailing. At the nation’s largest department store, executives were aware that the urban core was flawed as a retailing center and that the giant emporiums had to adjust.

Not only was downtown still the place to shop, but it was a destination for millions of entertainment seekers. New York City’s Theater District in midtown Manhattan was world famous, with its unequaled cluster of legitimate theaters and movie palaces, including the mammoth Roxy, with over six thousand seats.26 Other cities could boast of less famous but still significant theater areas in the central business districts. The pride of Cleveland was Playhouse Square, with five theaters built in the early 1920s, four of them showing motion pictures in 1945 and one devoted to legitimate, live theater. In these palatial settings, thousands of Clevelanders enjoyed entertainment fare from Hollywood and Broadway. The State Theater claimed to have the world’s largest theater lobby, a gargantuan corridor decorated in a mix of Roman, Greek, and baroque motifs stretching 320 feet and embellished with four allegorical murals representing the four continents of Europe, Asia, Africa, and America. Two marble staircases provided access to the mezzanine, which opened on to the 3,400-seat auditorium. In the Grand Hall of the adjacent Palace Theater, moviegoers were dazzled by the light of Czechoslovakian cut-crystal chandeliers, the richness of golden Carrara marble, and the magnificence of dual white marble staircases. The auditorium, with a seating capacity of over three thousand, was vaguely Chinese in style, the management claiming that it was modeled after the imperial palace garden in Beijing.27

Detroit also had its share of exuberant downtown movie palaces. Most notably the Fox Theater, with a seating capacity of more than five thousand, was an incongruous mix of Indian, Siamese, and Byzantine styles with gilded plaster figures of everything from elephants to Hindu goddesses encrusting the interior.28 In downtown Seattle, the exotic Coliseum and Mayflower theaters demonstrated that the metropolis of the Northwest had its share of cinema palaces. Meanwhile, in Los Angeles the downtown theater district centered on South Broadway, with the Los Angeles, Orpheum, Tower, State, Globe, Pantages, Million Dollar, and Roxie theaters vying for patronage from entertainment-hungry southern Californians.

Many neighborhood movie houses also presented Hollywood’s offerings to urbanites throughout the nation. In the largest cities, some of these matched their downtown counterparts in size and elegance. Yet most neighborhood movie houses were modest in comparison with the downtown palaces, and they were generally second-run venues. In other words, the latest offerings from Hollywood showed downtown at first-run theaters, whereas the neighborhood houses exhibited films released a few months earlier that had already played downtown. As in the case of retailing, the latest, biggest, and best were generally found in the central business district. Millions of Americans attended neighborhood theaters because they were conveniently located near their homes. Yet nowhere were there more of the latest film offerings in such a small geographic area as downtown.

Moreover, downtown was the site of the biggest and best in lodging. Tourist courts offered overnight accommodations to auto-borne travelers along the highways leading into the city. But the grim little tourist cabins did not rival the downtown hotels. If one wanted more than simply a bed and a roof over one’s head, one had to go downtown. Catering to rail-borne visitors in town to transact business in the metropolis’s unquestioned center of commerce, massive downtown hotels arose in every major city during the early twentieth century, the most elegant winning a nationwide reputation. The Waldorf Astoria in New York City, the Palmer House in Chicago, the Peabody in Memphis, the Adolphus in Dallas, and the Brown Palace in Denver were landmarks of the city center and, like the skyscraper and department stores, symbols of downtown’s supremacy. Not only did travelers stay in these and hundreds of less distinguished downtown hostelries, but scores of metropolitan organizations held their banquets in the grand hotel ballrooms. The downtown hotels were meeting places as well as shelters for out-of-town visitors. They were places to see others and to be seen.

The downtown hotels were also among the principal entertainment venues of the metropolis. Among their amenities were supper clubs offering big-band music and a variety of other performers. For example, the College Inn in Chicago’s Sherman House was the place to enjoy the best in big-band fare. In September and October 1945, it hosted first the Lionel Hampton band, followed by the Les Brown band, with singer Doris Day, and then the Louis Prima orchestra, all among the premier musical groups in the nation. Florian Zabach and his orchestra was playing at the American Room in the nearby LaSalle Hotel, and the posh Empire Room at the Palmer House was presenting its fall revue. If one sought further entertainment, one could try the Mayfair Room at the Blackstone Hotel or go across the street to the Stevens Hotel’s Boulevard Room to enjoy its show “Shapes Ahoy!” with Clyde McCoy and his orchestra.29 That same October, Chicago’s Congress Hotel opened its Glass Hat Room; according to a local columnist, it was adorned with a “large glass topper over the bar, … shimmering spun glass drapes, [and a] fan-shaped glass background for the band, tinted in changing colors by the special lighting system that ostensibly, at least, follows the mood of the music.”30

With skyscrapers, department stores, movie palaces, and great hotels, downtown was a zone of real-estate riches. The chief source of municipal revenue was the property tax, and in no other area of the metropolis was property so valuable and thus so lucrative to city government. In 1940 the central business district of Philadelphia comprised 0.7 percent of the city’s total area yet accounted for 17.4 percent of Philadelphia’s assessed value.31 Likewise, in the late 1930s, downtown Detroit contained 0.4 percent of the city’s area but 12.9 percent of its entire assessment.32 These figures were typical of the situation throughout the nation. With 1 or 2 percent of the land area in the city, the central business district paid anywhere from 12 to 20 percent of the property taxes. Not only was downtown the hub of office work, retailing, and entertainment, but it paid the bills for the city, subsidizing less fortunate areas with low property values. Downtown Saint Louis, for example, paid two and a half times more in municipal taxes than it cost in city services.33 With the profits from the central business district, Saint Louis city officials could cope with the imbalance between revenues and expenditures in the poorer residential neighborhoods. The single dominant focus of the metropolis, downtown was also the area that ensured the survival of city government. Without the central business district, there could not be a city.

The governmental institutions that benefited from downtown’s wealth were appropriately concentrated in the vital hub. County government operated from the centrally located county courthouse, and in the heart of downtown city hall was the command center for the government of the central city. Moreover, in 1945 the central cities of Boston, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Detroit, and their ilk across the nation were clearly the dominant governments of the metropolitan area. Unlike in later years, when the number of people living in suburban cities or towns far exceeded the number in the central city, in the mid-1940s the bulk of the metropolitan population remained within the central-city boundaries. According to the 1940 census, the twenty most populous central cities were home to 63.2 percent of all the residents in their metropolitan areas.34 Over 80 percent of all people in the Baltimore metropolitan area actually lived in the city of Baltimore, and more than 70 percent of the inhabitants of the Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Washington, and Milwaukee metropolitan areas resided within the municipal limits of the central city. In other words, the central-city government was more significant than it would be later in the century. It governed the great majority of metropolitan residents, and downtown’s city hall was the preeminent hub of local government.

The metropolitan lifestyle of 1945 had, then, a single focus. The city center dominated work, play, shopping, and government. Even those who could not afford to attend a show at the Empire Room, who felt excluded from Baltimore’s department stores because of race, or who did not have a white-collar job in a skyscraper could not escape the influence of the single dominant hub. Its executives dictated corporate policy affecting workers in outlying factories, its city officials determined public policy, and its department stores guided women as to what to wear and what to buy. The critics for the downtown-based metropolitan daily newspapers told urbanites what movies to attend, and the columnists kept them aware of the latest developments in the swank night clubs. Although divided socially, ethnically, and politically, the fragments of America’s metropolitan areas were drawn together by their common focus on the preeminent core. They were all satellites orbiting around a common star.

The Black–White City

Despite a common attraction to the dominant hub, metropolitan Americans were far from united. Most notably, they were divided by race. Historically the black population had been concentrated in the rural South. But during the three decades before 1945, an increasing number of African Americans were seeking to better their lot by migrating to cities. In 1940 blacks constituted more than 40 percent of the populations of Memphis and Birmingham, 35 percent of the residents of Atlanta, and 30 percent of the inhabitants of New Orleans. In the North, they were a less formidable contingent of the urban populace, comprising 13 percent of the populations of Philadelphia, Saint Louis, and Indianapolis and between 8 and 10 percent of the inhabitants of Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland.35

During World War II, however, the flow of black migrants became a flood as almost 1 million African Americans left farms and small towns for life in industrial centers. With industry operating at full capacity to fill the Allied war needs and millions of men and women serving in the military, urban businesses were desperate for workers. Blacks sought to take advantage of the labor shortage. Between 1940 and 1944, the nonwhite population of the Detroit area increased by 83,000, or 47 percent. An estimated 60,000 to 75,000 African Americans moved to Chicago. On the West Coast, where the black population had been relatively small before the war, the rise was even more spectacular. The number of African Americans rose 78 percent in Los Angeles, 227 percent in the San Francisco Bay area, and 438 percent in metropolitan Portland.36 In 1944 the Swedish social scientist Gunnar Myrdal titled his study of race in the United States The American Dilemma. At the close of World War II, it was becoming more specifically an urban dilemma.

The move to the city, however, did not free African Americans from the long-standing restraints of racial segregation and discrimination. In southern cities, they were required to sit at the back of streetcars and buses, the front being reserved for whites. Railroad stations had separate black and white waiting rooms, and African American children were relegated to separate educational facilities, being forbidden by law to attend school with white students. Cities maintained special African American branches of public libraries, and in Atlanta blacks were not permitted to use any books in the main city library or the other white branches, even through interlibrary loans.37 The criminal justice system was designed to keep blacks in an inferior position. African Americans generally could not serve on juries, and the white police force reportedly ignored the legal rights of black suspects. According to an African American newspaper editor, “When they arrest a Negro and take him to jail they usually beat him up. It just seems to be a practice here.”38 Houston employed five African American policemen who could hold whites but not arrest them. They were hired to patrol the black neighborhoods that white officers sought to avoid. One black leader explained: “The white police used to run in these Negro sections, but so many of them ran into bullets that they couldn’t find who fired, they had to put Negroes out in these places.”39

Racial segregation was, then, pervasive in the urban South. A 1943 study of segregation stated uncategorically, “No Negroes are accommodated in any hotel in the South that receives white patronage.” Similarly, it reported: “Cafes catering to whites frequently have a side or back entrance for Negroes, and they are served at a table in the kitchen.”40 At lunch counters serving whites, blacks could not sit down but could only order food to carry out. In theaters attended by whites, blacks were restricted to seats in the balcony, although by the 1940s there were a number of movie houses catering solely to African Americans. Southern blacks seemed to prefer attending these African American theaters rather than suffer the indignity of a seat in the balcony “crow’s roost” of a white movie house. Some Atlanta office buildings had separate elevators for blacks, as did the courthouse in Birmingham.41

Segregation was less common in the North, and blacks could sit next to whites on public transit and use the same waiting rooms as whites. In 1945 a study of black life in Chicago reported that “by 1935 discrimination against Negroes in downtown theaters was virtually non-existent and only a few neighborhood houses tried to Jim-Crow Negroes.” Yet other businesses did discriminate. The same study found that Chicago’s roller-skating rinks, dance halls, and bowling alleys enforced a strict color line, and the city’s hotel managers did not “sanction the use of hotel facilities by Negroes, particularly sleeping accommodations.”42 This was true in other cities as well. In 1942 the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers Union moved its convention site from Indianapolis to Cleveland because Indianapolis hotels refused to house black union members, and the following year the United Auto Workers Union shifted its annual meeting from Saint Louis to Buffalo because Saint Louis hotels likewise would not accommodate African American delegates.43 Hotels might make exceptions for distinguished black visitors. In 1943 New York City’s Waldorf Astoria made an exception to its usual policy of excluding blacks by accommodating the visiting president of Liberia.44 The leading hotel in Dayton allowed the famed black concert singer Marian Anderson to stay overnight, but, in the words of the manager, “it was all arranged beforehand, so that when she came in she didn’t register or come anywhere near the desk. She went right up the elevator to her room and no one knew she was around.”45

Especially embarrassing to a nation that lauded freedom and was engaged in mortal combat with racist Nazi Germany was the state of black–white relations in the capital city of Washington, D.C. Blacks were excluded from downtown hotels, restaurants, and theaters.46 The restaurant in the Capitol was off-limits to African American customers, a fact publicized in 1943 by the ejection of a group of blacks and whites representing the Greater New York Industrial Council.47 The District Medical Society refused admission to African American physicians, and most hospitals either excluded black patients or restricted them to segregated wards. Most African Americans went to the two public hospitals, the larger of the two being Gallinger Municipal. Yet the conditions at these hospitals were inferior to those at white institutions. According to a national magazine, “Gallinger Municipal Hospital puts the legs of its beds in pans of water to keep the cockroaches from snuggling up to the patients.”48 The public schools were also segregated, and those for blacks were predictably inferior. In 1946 the per-student load for black teachers was 12 to 30 percent higher than for their white counterparts. In the school year 1946/1947, the per-pupil operating expenditure for white schools was 160.21, whereas for black schools it was only $126.52. The two leading universities in the city, George Washington and Georgetown, did not admit blacks.49

No aspect of black–white relations, however, was as hotly debated as housing discrimination. Most controversy centered on racial restrictive covenants. These were agreements among homeowners or provisions in deeds that prohibited the sale or lease of property to African Americans. In the mid-1940s, they were most common in middle-income white neighborhoods around existing black areas and in newer subdivisions. Racial covenants were often products of neighborhood improvement or property owners associations dedicated to preserving housing values and the ethnic purity of their area. For example, in 1945 a committee of owners in the North Capitol area of Washington, D.C., warned of the need to adopt restrictive covenants covering all the blocks in the neighborhood so that it could “continue to be the strongest protected white section in the District of Columbia. No section of Washington is as safe from invasion as is your section,” the committee told area residents; “let’s keep it safe!”50 In a pamphlet on restrictive covenants published by Chicago’s Federation of Neighborhood Associations in 1944, the federation warned that white Chicagoans should not have to explain to returning soldiers that “at the request of a very limited number of people hereabouts, we have altered your home and neighborhood conditions while you were away fighting for America.”51 White soldiers fighting for freedom, the federation believed, should be able to return to the neighborhoods they had left a few years earlier and find them as lily white as ever. Moreover, this was a widely shared belief. In 1944 at least seventy neighborhood associations in Chicago were actively engaged in the preparation and enforcement of racial restrictive convenants.52

These associations were ready to resort to legal action to bar blacks from protected neighborhoods. In Los Angeles, suits brought against the well-known black actress Ethel Waters and Academy Award winner Hattie McDaniel publicized the plight of African Americans attempting to move into white areas. Between 1942 and 1946, more than twenty racial covenant suits were initiated in Los Angeles alone, and an estimated sixteen were pending in Chicago at the close of 1945.53

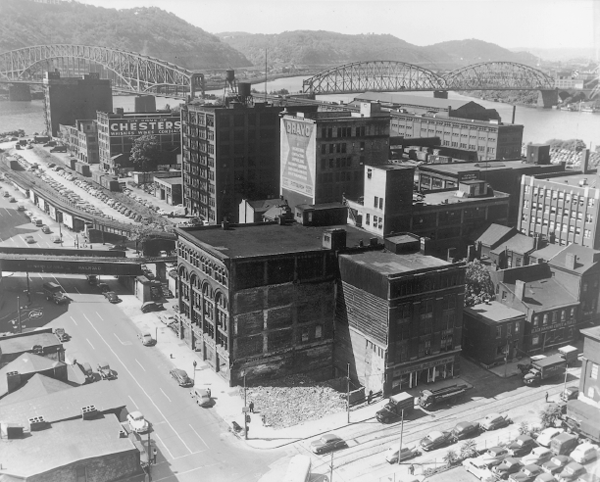

Not only did whites oppose blacks moving into existing homes, but they battled any new housing projects that might mark the beginning of an African American invasion. The Seven Mile–Fenelon Improvement Association in Detroit led opposition to black tenancy in the Sojourner Truth public-housing project being built in its area. A neighborhood pastor expressed the views of his parishioners when he told housing officials that the project would mean “utter ruin” for many mortgaged homeowners in the area, “would jeopardize the safety of many of our white girls, … [and] would ruin the neighborhood, one that could be built up in a fine residential section.”54 In the minds of many whites, black neighbors meant plummeting property values, a plague of sexual assaults, and doom for neighborhood aspirations. When in February 1942 the first black families moved into the Sojourner Truth project, a riot ensued between blacks and whites, resulting in 220 arrests and leaving 38 hospitalized (figure 1.3).55

FIGURE 1.3 Blacks being arrested during the riot at the Sojourner Truth public-housing project, Detroit, February 1942. (Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University)

Elsewhere in the Detroit area, there was resistance to any black projects in white districts. In 1944 suburban Dearborn’s white mayor, Orville Hubbard, opposed a project in his municipality, claiming that “housing the Negroes is Detroit’s problem.” He bluntly proclaimed: “When you remove garbage from your backyard, you don’t dump it in your neighbor’s.” The following year, Detroit’s working-class neighborhood of Oakland battled a proposed black public-housing project. One resident told the Detroit city council, “We have established a prior right to a neighborhood which we have built up through the years—a neighborhood which is entirely white and which we want kept white.”56

Many white New Yorkers shared this devotion to segregated neighborhoods. When in 1943 the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company announced plans for Stuyvesant Town, a giant Manhattan complex of nine thousand apartments, the company’s president made it clear that blacks would be excluded from the complex. Responding to criticism of this policy, the following year Metropolitan unveiled plans for a project in black Harlem that would consist of seven thirteen-story buildings, almost all of whose tenants would be African American. In other words, Metropolitan was dedicated to separate but equal housing for New Yorkers rather than racially integrated neighborhoods where blacks and whites might mix.57

White resistance to black neighbors and black projects resulted in serious overcrowding and deplorable housing conditions for many African American newcomers to the city. Commenting on his home in a decrepit former saloon, a black worker at one of Detroit’s major plants lamented, “It’s hell living here,” and a journalist wrote of an African American apartment building in the Motor City where the walls were “stuffed with rags and paper to keep out the weather and rodents” and “tin cans are suspended from the ceiling to catch the water that is always coming through.”58 On the West Coast, blacks ironically benefited from racism, for the evacuation and detention of Japanese Americans opened housing to wartime newcomers. Thousands of blacks moved into Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo, but the housing proved insufficient. According to one report, “At least 13,700 of these Negro families have had shelter only through doubling up, tripling up or by leading an unhappy existence in abandoned store buildings and in other places never intended for human habitation.”59 In Chicago more than 20 percent of all black households lacked a private flush toilet, and in Saint Louis 40 percent of nonwhite dwellings were without such facilities.60

Forced into an overcrowded fragment of the city by white-imposed barriers, blacks had developed communities of their own, sub centers within the metropolis where African Americans lived, shopped, played, and worshipped. In New York City, Harlem was the preeminent black community, with 310,000 African American residents; in Chicago, it was South Side Bronzeville, home to an estimated 250,000 blacks.61 Paradise Valley was the principal black neighborhood in Detroit, and Central Avenue the center of black existence in Los Angeles. In these neighborhoods, there were black churches, black newspapers, and a full range of stores and services catering to African Americans. This was black territory, and other than the white merchants operating businesses in the neighborhoods, few whites frequented these areas. White-dominated downtown was the single dominant focus of the metropolis as a whole, affecting the lives of blacks and whites alike. Yet for African Americans there were separate communities, in which they spent most of their hours and to which whites expected them to remain.

Despite the restraints imposed by whites, in 1945 most blacks probably believed they never had it so good. This was because World War II opened unprecedented job opportunities for African Americans and dispelled the endemic poverty of the economically depressed 1930s. At first, defense industries were reluctant to hire blacks, but as labor shortages developed in 1942 the racial barrier was lowered. In the summer of 1942, only 3 percent of the workers in war industries were black; by September 1944, African Americans constituted 8 percent of war workers. They were especially numerous in the shipbuilding yards, where they made up about one-eighth of the workforce.62 The burgeoning aircraft, munitions, and firearms plants as well as other war industries generally turned to black males before black females to fill their labor needs. But by 1944, thousands of African American women had left their jobs as domestic servants and found better-paying factory positions. In 1940 black females constituted 4.7 percent of all women factory operatives; by 1944 the figure was 8.3 percent.63 The change in black employment was evident in Detroit’s Chrysler plants. Before the war, black men represented 3 percent of the company’s Motor City workforce. Although Chrysler employed more than six thousand women, not one of them was black. In March 1945, however, African Americans made up 15 percent of the workforce in Chrysler’s Detroit plants, and the five thousand black women workers constituted one quarter of all female employees.64

Blacks not only found factory jobs, but also secured more of the better positions. Whereas before the war African Americans were fortunate if they could obtain the most menial of unskilled factory jobs, between 1942 and 1944 the number of blacks in skilled and semiskilled positions doubled. In 1940, 4.4 percent of black male workers had skilled manufacturing jobs as compared with 7.3 percent in 1944.65 A leading African American reported that “in World War II, the Negro achieved more industrial and occupational diversification than he had been able to secure in the preceding 75 years.”66 Change was slower and less dramatic in the South, where blacks were more likely to be found in janitorial and maintenance positions at war plants. But for many, the racial barriers in employment seemed to be crumbling.

There was, however, resistance to this change. Before 1941 in most cities, only whites were eligible for employment as bus drivers and streetcar motormen and conductors. Yet serious labor shortages during the war and pressure from the federal government compelled transit authorities to open these positions to African Americans. In some cities such as Chicago and San Francisco, this change occurred without undue delay or much conflict. Elsewhere it was more difficult. In August 1944 in Philadelphia, the proposed hiring of black operators led to an almost weeklong public transit strike by white workers. President Roosevelt authorized the army to take control of the transit system, and five thousand troops were sent to the City of Brotherly Love to force transit employees to return to work.67 In Los Angeles there were similar problems. When in February 1943 the transit company promoted two blacks to the position of mechanics’ helpers at a bus terminal, eighty white employees at the terminal struck, suspending operations until the company rescinded the promotions. Another race-related work stoppage occurred among Los Angeles transit workers a few days later.68 By 1945 in both Philadelphia and Los Angeles, blacks had won access to the better-paid transit jobs but not without conflict.

Race-related work stoppages also occurred sporadically at war plants. Before the spring of 1943, the Alabama Dry Dock and Shipping Company of Mobile had not placed any African Americans in skilled jobs. In May of that year, however, it attempted to upgrade twelve black workers to welding positions and add them to a previously all-white crew. When white workers heard of this, they went on a rampage, assaulting black workers in the shipyard and injuring an estimated fifty people. Blacks fled from the yard, and peace was restored only when the company agreed to create four separate all-black crews assigned to only the construction of ship hulls. Blacks could move up to welding jobs, but they could weld only with other blacks in segregated, Jim Crow units.69 The following month, the upgrading of three blacks to skilled positions at Detroit’s Packard Motor Company resulted in a short “hate” strike by white workers. And in July 1943 at the Bethlehem Steel Shipbuilding Company near Baltimore, white riveters staged a walkout to protest the training of blacks for skilled jobs.70 At both Packard and Bethlehem, labor union officials forced the white workers to return to their jobs, but the disruptions in America’s wartime industries were symptomatic of deep-seated racial antagonism.

If anyone had any doubts about the existence of such antagonism, Detroit’s full-fledged race riot in June 1943 certainly dispelled them (figure 1.4). On a hot Sunday night, fighting broke out between blacks and whites at Belle Isle Park. False rumors spread through the black community that an African American women and her baby had been thrown into the Detroit River, and whites heard tales of a woman raped and killed by blacks. In the early hours of Monday morning, African Americans rampaged through Paradise Valley, looting and wrecking white-owned stores. Meanwhile, white mobs began pelting the automobiles of passing blacks with stones and attacking African Americans as they left all-night movie theaters. As the sun rose on Monday morning, whites and blacks battled at various sites in the city. On Monday afternoon, ten thousand whites congregated in the area of city hall on the northern edge of downtown, attacking any vulnerable black pedestrians and dragging them off streetcars. By midnight Monday, federal troops had been called in, and during the following few days they restored order. Thirty-four people were killed in the riots, 461 were officially reported as injured, and property damage from looting and vandalism amounted to more than $2 million.71 One nineteen-year-old white expressed the attitude of the Detroit mobs when he exclaimed: “Jesus, but it was a show! We dragged niggers from cars, beat the hell out of them, and lit the sons of bitches’ autos. I’m glad I was in it! And those black bastards damn well deserved it.”72 African Americans sharply criticized Detroit’s predominantly white police force for its failure to protect blacks adequately and for its seeming reluctance to restrain white rioters. For African Americans, it was one more example that in the black–white city the deck was stacked in favor of whites.

FIGURE 1.4 Rioters running from tear gas in Detroit during the riot of June 1943. (Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University)

The racial tension in Detroit was not an anomaly. In August 1943, a white New York City policeman shot and superficially wounded a black soldier who had interfered with the arrest of a woman in a Harlem hotel. Amid rumors that the black soldier had been killed, rioting broke out and mobs looted white-owned stores throughout Harlem. In part, this was a reaction to the high prices charged by white merchants. Writing of Harlem, one black observer reported: “For every dollar spent on food, the Negro housewife has to spend at least six cents in excess of what the housewife in any other comparable section is required to pay.”73 Five people were killed in the Harlem riot and approximately five hundred injured. Chicago escaped a full-scale riot, but Chicagoans knew that there was sufficient racial tension to spark a local version of the Detroit melee. At nearby Fort Sheridan, the army commander asked for twelve thousand tear gas and smoke grenades and ten thousand shotgun shells “for use in the event of disorders in Chicago.”74 As blacks prepared to protect themselves, the going price for revolver shells in Bronzeville rose to 12 cents each as opposed to the usual 2 cents. “Occasionally one can see a colored man carrying a rifle or a shot gun wrapped up in a newspaper or a gunny sack,” observed a Chicago sociologist during that hot summer of 1943.75

Across the country, city leaders were attempting to cool off the racial situation. During the year following the Detroit riot, at least thirty-one cities created municipal commissions to deal with racial questions. Moreover, by the fall of 1945 there were more than two hundred citizens’ committees working with these commissions to reduce tensions.76 In New York City, there was the Mayor’s Committee on Unity; in Cleveland, the Community Relations Board; and in Los Angeles, the Committee on Human Relations.77 Chicago’s municipal authorities, however, claimed to have acted first with Mayor Edward Kelly’s creation of the Mayor’s Committee on Race Relations in July 1943. In its annual report for 1944, the committee acknowledged that Chicago was a black–white city when it recognized “various group conflicts—anti-Semitism, discrimination against Mexicans, Japanese-Americans, and others—” but clearly stated that it had “given its major efforts to Negro-white relationships.”78 The black–white division was the great ethnic problem of the city and the one that demanded immediate official attention. In February 1944, Kelly also called four conferences on race relations, attended by two hundred business and labor leaders, city officials, and social workers. Then in May 1945, with the cooperation of sixty-four civic organizations, Kelly convened the Chicago Conference of Home Front Unity, where blacks and whites again discussed race relations.

Although the Chicago Mayor’s Committee claimed some achievements, it also admitted failures. Chicago’s public schools in black districts were overcrowded, and the board of education contributed to the racial segregation of the schools by issuing transfer permits to white children living in African American areas. These permits allowed them to attend predominantly white schools outside their neighborhoods. At the close of the conference in 1944, the chair of the Mayor’s Committee characterized the schools as “the least satisfactory of the basic city services.” A year later, the committee’s chair bluntly admitted that his organization’s record with regard to the schools was “nearly perfect—a perfect zero.”79 Much talk and mayoral pressure might produce a greater sensitivity to racial issues among city leaders. But the black–white divide was not to close in the mid-1940s.

Chicago-area educators needed to take action, for in the fall of 1945 racial clashes broke out in local high schools. In nearby Gary, Indiana, a fight between African American and white students at a football game led to a two-month strike at Froebel School by white pupils who demanded that all blacks be transferred from the school. Soon afterward, white students walked out of Calumet and Englewood high schools in Chicago to protest the presence of blacks in their institutions.80 Meanwhile, there was also a growing wave of attacks on blacks who dared to move into Chicago’s white neighborhoods. In June 1945 an editorial in the principal African American newspaper in Chicago announced: “Hate-crazed incendiaries carrying the faggots of intolerance have in the past several months attacked some 30 homes occupied by Negroes on the fringes of the black belt, solely because these colored citizens have desperately crossed the unwritten boundary in their search for a hovel to live in.” In this racial warfare, buildings had been “set afire, bombed, stoned and razed” and their occupants “shot and slugged.” The editorial concluded: “Today racial dynamite is scattered about the South side. It needs but a spark to explode.”81

Despite the well-meaning rhetoric of mayors’ committees and interracial conferences, the sparks of racial hatred were evident everywhere. In both southern and northern cities, the racial chasm seemed unbridgeable. The American metropolis of 1945 was a black–white city, and this fact would be basic to urban life in the decades following World War II. It would determine where and how metropolitan Americans lived. Underlying the metropolitan lifestyle were the fissures of race.

The Suburbs

Underlying the metropolitan lifestyle of 1945 were also the fissures of municipal boundaries. Many people in each major metropolitan area lived in suburban communities outside the central city. They were closely tied to the core municipality, most often working and shopping there. “A night on the town” meant a trip to the central-city downtown, for there were the bright lights and excitement of the metropolis. The outlying municipalities were thus well within the central-city orbit, but they were places apart. They had separate governments that jealously protected their prerogatives and resented the big-city threat to their autonomy. Those who scoffed at the suburbs might claim that the municipal boundaries were artificial and that all metropolitan residents were actually part of one big city. But there was a strong sense of autonomous identity in the outlying municipalities, a sense that the communities were separate entities and wanted to remain such. The suburban municipality was a place where local government could be tailored to the needs and desires of the local populace, where residents were not subject to the amalgamated, insensitive rule of the big city. Although denounced as artificial and parasitical, these suburban municipalities proliferated and survived. Very few ever relinquished their existence and consolidated with the central city. They were a fact of life in 1945 and would become increasingly so in coming decades.

Municipal boundaries did, then, make a difference. The governmental fragmentation of the metropolis placed the imprimatur of the state on the divisions within metropolitan America. It fostered metropolitan divisions along lines of class, ethnicity, and economic interest. And the government boundaries were often insuperable barriers to metropolitan cooperation. Like the fissures of race, the governmental lines were cracks in the single-focused metropolis of 1945. Along these lines the metropolis would divide in future decades as suburban municipalities and their residents grew to feel that the central city’s business was none of theirs.

Already in 1945, Americans were aware that the suburbs were of increasing significance in metropolitan life. Whereas in 1910, 76 percent of the inhabitants of the metropolitan areas containing the twenty largest cities lived in the core municipalities, thirty years later the figure was down to 63 percent.82 During the 1920s and 1930s, millions of Americans moved to the suburbs, and many more seemed poised to make the outward trek once the federal government lifted wartime restrictions on residential construction.

Despite prevailing stereotypes, the satellite communities did not conform to one uniform way of life. There was not, nor would there ever be, a single suburban lifestyle. Some suburbs were upper-class retreats with meticulously manicured estates, and others were industrial communities with factories and working-class ethnic populations. There were suburbs where wives in station wagons met their husbands at the commuter rail station each weekday evening, but there were also communities of modest bungalows or medium-priced neocolonial homes where husbands would rely on the streetcar to take them to their downtown destinations. Those living in fringe communities were a diverse lot, and the outlying municipalities existed for a variety of reasons. What they had in common was political independence from the city and a desire to retain it. Through independence they could pursue their particular diverse destinies, with minimal interference from the central city or from one another.

One of the most famous suburbs, and one that conformed to many people’s vision of suburbia, was Scarsdale, New York, a community of thirteen thousand affluent residents. Located in Westchester County nineteen miles north of Manhattan’s Grand Central Terminal, Scarsdale was known as “the richest town in America,” its residents having a median annual income in 1949 of $9,580, more than twice that of the nearby suburban communities of Rye and Mamaroneck and more than three times that of Manhattan.83 Its homes were generally eight-to twelve-room, two-story manses in the fashionable Tudor or colonial-revival styles (figure 1.5). Scarsdale was a community for wealthy commuters to New York City, and its residents wanted it to remain just that.

To preserve their way of life, Scarsdale residents created neighborhood associations. According to one reporter of the local scene, the oldest neighborhood group, the Heathcote Association, was formed in 1904 “so that residents building there would be secure in the ownership of large parcels with a substantial investment in dwellings.” The more recently organized Secor Farms Property Owners Association was created “to foster economy and efficiency in government [and] to stimulate public interest in civic affairs” but also “to procure high quality in building construction even to the approval of plans for new houses.”84 Reinforcing the efforts of the Secor Farms group to ensure an upscale residential environment was the village’s zoning code. In 1944 a prospective developer sought an amendment to the zoning ordinance to build rental units on a twenty-six-acre estate. Numerous residents and neighborhood associations protested this zoning exception, which might open the door to multiple-family dwellings, and the developer withdrew the proposal.85 The same year, a group of homeowners petitioned the village’s governing board to find “some means … to protect our section against the creation of low-cost homes.”86 Stirred to action by this potential threat to the Scarsdale way of life, the board embarked on the drafting of a new and more restrictive zoning code.

FIGURE 1.5 Home in Scarsdale, New York, in the early 1940s. (Library of Congress)

In this protected world apart, club life flourished. For devotees of patrician sports, the Scarsdale Golf Club and Fox Meadow Tennis Club offered exclusive links and courts. The Woman’s Club served female Scarsdale. According to its constitution, this organization sought “to bring together all women interested in the welfare of the village … and to foster a general public and democratic spirit” among the affluent few who could afford life in this plutocratic democracy. There were various sections in the club, each catering to some interest of the female population. For example, the American Home Section sought “to bring to its members new and stimulating ideas in the field of home decoration, gracious entertaining and personal grooming.”87

The pride of both males and females in Scarsdale was the school system. Tailored to suit the class aspirations of upper-crust Scarsdale, the school system prepared its students for a college education, preferably at one of the nation’s elite institutions of higher learning. In the early postwar years, over 90 percent of the graduates of Scarsdale High School went on to college. Between 1946 and 1951, twenty-nine Scarsdale graduates went to Cornell, whereas Yale and Dartmouth could each claim twenty-six of the suburb’s finest. Among women’s colleges, Mount Holyoke led with thirty-four Scarsdale women, and Smith followed with twenty-three.88 The school system was handsomely funded and offered the best facilities, for it was a vital element in perpetuating the class standing of Scarsdale families from one generation to the next (figure 1.6).

Scarsdale’s citizenry was not willing to allow partisan politics to interfere in the governance of their vaunted schools or protected village. Rejecting party contention between Republicans and Democrats such as existed in America’s big cities, the suburbanites chose to vest the authority to nominate village board candidates in a nonpartisan committee consisting of the president of the Town Club (the leading civic organization), the president of the Woman’s Club, representatives of the neighborhood associations, and some at-large representative citizens. For school board positions, the nominating committee included the president of the Parent-Teacher Council instead of spokespersons for the neighborhood groups. The slate nominated by these committees would run unopposed. Scars-dale residents thus sought to eliminate the unseemly competition of big-city politics and substitute a consensual slate chosen by upstanding civic leaders who nominated only those supposedly best suited for office. One did not run for office; instead, the best citizens were asked to do their civic duty and serve selflessly for the welfare of the community.

FIGURE 1.6 Schools were the pride of Scarsdale, as is evident in the library of the Quaker Ridge Elementary School. (Library of Congress)

Other elite suburbs adopted similar schemes for nonpartisan, consensual rule by the most esteemed citizens. On Long Island, Garden City operated under the “Gentleman’s Agreement,” which provided that the municipality’s four property owners’ associations select the nominees for the municipal board. As in Scarsdale, those chosen ran unopposed. “On the theory that municipal housekeeping of a village has nothing to do with political issues,” observed the municipal report for 1946, “the nominees usually are chosen from a list of civic-minded men who, regardless of party affiliation, have served their apprenticeship by years of work in the Property Owners’ Associations of their sections and who have thereby won the respect and trust of their neighbors.” Serving without pay, Garden City’s officers could “act with complete disinterestedness for the good of the Village as a whole.”89 A number of suburban communities accepted the reasoning of Garden City’s leaders. In nearby Lawrence, New York, the Independent Village Nominating Committee chose the sole slate of candidates appearing on the ballot. Across the Hudson River in suburban Leonia, New Jersey, nonpartisan representatives of civic organizations composed the Civic Conference, which selected the municipal officers.90 In the Chicago suburb of Hinsdale, the Community Caucus served this function, and beginning in 1944 in nearby Clarendon Hills a similar caucus identified those who were worthy to govern the community, thus saving the citizenry from a contested election.

Residents of Scarsdale and other suburbs were dedicated to preserving their peculiar governmental systems and the prerogatives of their enclaves. Fearing the growing power of Westchester County, in 1940 a Scarsdale defender proclaimed: “We must never lose sight of the fact that in our country we succeed best in government in small units…. We must cling to our Scarsdale idea of service by the best people of the Village; we must keep our slogan: The Village that never holds a political election.”91 Scarsdale’s cosmopolitan male executives commuted to Manhattan, where they ruled the corporate world and pulled the strings of international finance, but at home they cherished small-town government untarnished by the influences of the big city and based on a simple faith in the wisdom of civic-minded neighbors. Although Scarsdale matrons shopped along Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, kept apace of the world’s art and fashions, and prided themselves on a woman’s club featuring speakers on world affairs, their ideal community had to remain apart from the sordid realities of urban politics and the bitter socioeconomic and political competition that had plunged the globe into two world wars. Scarsdale was truly a world apart, an insulated enclave where residents had fashioned a better existence.

Few communities could match Scarsdale as upper-crust retreats, but across the nation there were versions of the New York suburb. In the Cleveland area, the elite found solace in Shaker Heights; in metropolitan Saint Louis, there was Ladue; the Miami area boasted of Coral Gables; Dallas’s wealthy purchased homes in Highland Park; and southern California’s Beverly Hills was known throughout the world. In the late 1930s Shorewood, north of Milwaukee, claimed to be the “Model Twentieth Century Village” where “every foot of land was restricted, either by deed stipulation or village ordinance.” A community guide published by Shore-wood’s municipal government boasted that the village gave “an impression of shade and affluence,” and its school system was “one of the most elaborate in the country for a village of Shorewood’s size.” A Wisconsin Scarsdale, “the village has no factories and wants none, limits its business area to a small shopping district, and self-consciously devotes its civic energies to making itself a pleasant place in which residents may live and spend their leisure.”92

Yet not all the communities beyond the central-city boundaries were Scars dales or Shore woods. Many were working-class, industrial suburbs that contrasted sharply with the upper-crust retreats but shared with their more affluent counterparts a desire for political autonomy. Few municipalities were more different from Scarsdale than Hamtramck, Michigan. Surrounded by Detroit, although politically independent of the Motor City, Hamtramck was a community of approximately fifty thousand residents, most of them of Polish ancestry. The median family income was about one-third that in Scarsdale, and the homes were primarily one-or two-family frame cottages on narrow lots with small yards. As late as 1950, only 51 percent of the houses in the frigid Michigan suburb had central heating. In 1940 there were sixty-one manufacturing concerns in town, employing 27,434 wage earners.93 Chief among these factories was the huge Dodge-Chrysler plant along the community’s southern boundary.

By the 1940s, Hamtramck’s schools were in deplorable condition, owing in part to the corruption of the local school board. At the beginning of the decade, the indignant state superintendent of public instruction felt compelled to withhold any further distribution of state funds to the sorry school system, and the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools threatened to revoke the high school’s accreditation. In 1945 the state audited the school system accounts and found wrongful expenditures of approximately $250,000, including spending for lavish junkets by school board members to Chicago and San Francisco.94

The mayor and city council members were even more notorious. During the Prohibition era, their willingness to protect bootleggers, gamblers, and prostitutes was well known, and many ended their terms of office in jail. “Because of chiseling of a few, cheap, grafting politicians, Hamtramck, down the years, has become a by-word of shame and reproach,” noted a Detroit observer in 1946. “Smart alecks say, ‘The first qualification for public office in Hamtramck is a prison term.’”95 Detroit journalists delighted in reporting the odious political high jinks of Hamtramck until finally in early 1947 one Detroit newspaper called on its competitors to “Lay Off Hamtramck.” “Hamtramck is not spotless, certainly,” editorialized the Detroit Times, “but neither is it a Gemorrah [sic].”96 Neither was it a Scarsdale.

Hamtramck was not an anomaly. Its counterpart in the Chicago region was Cicero, a suburb with a large eastern European, especially Czechoslovak, population and many industries, including the mammoth Hawthorne Works of Western Electric. During Prohibition, its working-class, ethnic population was more tolerant of alcohol than were the reform-minded do-gooders in the city of Chicago. Consequently, gangster Al Capone took refuge in Cicero, and it became renowned as a place where one could obtain the sinful pleasures forbidden in more reputable communities. Modest one- and two-family homes prevailed, although there were numerous small apartment houses. For those who were a bit more affluent, there was the Chicago suburb of Berwyn, with its acres of look-alike brick bungalows built on small lots in the 1920s. Nearby Elmwood Park offered abundant brick bungalows in a community just one step higher on the economic ladder. In the Chicago region and elsewhere, there were not just rich and poor suburbs but suburbs to serve each gradation of the socioeconomic scale.

This was true in the Los Angeles area, where the community of South Gate housed working-class suburbanites. It consisted of an array of modest frame homes, many of them self-built by their owners, who could not afford professional contractors. In 1940, 64 percent of its employed residents held working-class jobs, as compared with only 34 percent in Beverly Hills. By the late 1930s, the South Gate area had won the appellation “Detroit of the Coast,” and many of its residents worked in the nearby General Motors assembly plant or the Firestone tire factory. Among South Gate’s recent migrants were many Okies and Arkies, down-at-the-heels newcomers from Oklahoma and Arkansas seeking a decent wage.97

Nearby Vernon represented yet another variety of suburb: the community with many factories and few residents. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, there had been a steady migration of heavy industry to outlying sites, and especially favored were municipalities offering low taxes and few restrictions on industries. Among the communities with fewer than one thousand residents and tens of thousands of industrial employees were Vernon, just southeast of Los Angeles; Bedford Park, southwest of Chicago and the site of the giant Clearing Industrial District; and Cuyahoga Heights, beyond the southern boundary of Cleveland. Just as Scarsdale was tailor-made for upper-crust New Yorkers who wanted the best schools and the most stringent protection for residential property, these enclaves of industry were an ideal fit for manufacturers seeking to escape the exactions and regulations imposed by the big city.

During World War II, the outward migration of heavy industry accelerated with giant war plants proliferating along the metropolitan fringe. Aircraft plants flourished on suburban Long Island, east of New York City, and the Atlanta area’s largest defense employer was Bell Aircraft, located not in the city of Atlanta but in outlying Marietta. Chrysler built its great tank works in Warren, immediately north of Detroit, and Henry Ford created his sprawling airplane factory at Willow Run, twenty-five miles west of the Motor City’s downtown. In the Chicago area, only three of the eight major war plants were inside the central-city limits.98 In 1945 many light-manufacturing plants still clustered near the central-city core, but the sub-urbanization of industry had advanced to the point where millions of metropolitan Americans earned their living beyond the big-city boundaries.

Adding to the variety of suburbs were a few all-black communities. In 1944 Lincoln Heights, north of Cincinnati, incorporated as a municipality, creating a fragment of black power in the Queen City area.99 Robbins, south of Chicago; Brooklyn, Illinois; and Kinloch, Missouri, in the Saint Louis metropolitan area, were other examples of black municipalities along the fringe. Composed of modest frame structures, these communities bore no resemblance to Scarsdale or Shorewood. But like their more affluent counterparts, these black suburban municipalities enhanced the opportunity for a fragment of American society to determine its own governmental destiny; they offered an alternative to the white-dominated regimes of other suburban municipalities and of the big city. This was evident in an incident involving Robbins. When some black businessmen were denied service at a restaurant in a white suburb because of their race, they went to nearby Robbins and swore out a warrant for the restaurant manager’s arrest for violating Illinois’s civil rights law. An African American deputy served the warrant and brought the manager to Robbins, where he was incarcerated until he could raise the bail.100 White suburban authorities and police officers in the white-dominated central city could not be counted on to enforce the law so vigorously. Robbins, however, was a community where African Americans could secure their legal rights. Just as white ethnics could find refuge in Hamtramck and Cicero from the moral codes imposed on them by teetotalers, blacks could go to Robbins to seek imposition of the civil right laws too often ignored by white authorities.

America’s suburbs were, then, a diverse lot, but Scarsdale, Hamtramck, and Robbins all shared a degree of political autonomy that boded ill for a unified metropolitan life. Suburban municipalities added the force of law to the social, cultural, and ethnic rifts dividing metropolitan America. They still paled in comparison with the central city, and the big-city downtown remained a dominant focus affecting the lives of all disparate suburbanites. If, however, the suburbs continued to proliferate and the gravitational pull of the central city diminished, the prognosis for metropolitan unity was poor.

The Future

In 1945 urban observers were more focused on the future than perhaps at any time in American history. They realized there were serious urban problems that they would have to confront at war’s end. The nation’s major cities were showing signs of age, and to the humiliation of local boosters Boston, Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Saint Louis had all declined in population between 1930 and 1940. During the 1930s and first half of the 1940s, economic depression and the war effort had slowed new construction and prevented needed repairs. The result was physical decay and acres of new slums. Moreover, in the two decades before the war, the automobile had loosened the bonds tying the metropolis together and weakened the central business district. Observers knew that once rationing of gasoline and tires ended and manufacturers resumed production of automobiles, Americans would eschew public transit and move into the driver’s seat in increasing numbers.

Among the foremost concerns generated by the automobile was decentralization. During the first half of the 1940s, urban experts repeatedly commented on the automobile-induced outward migration of population and business and warned of the dire consequences. In 1940 the distinguished planner Harland Bartholomew announced that “the whole financial structure of cities, as well as the investments of countless individuals and business firms, is in jeopardy because of what is called ‘decentralization.’” The following year, a major Cincinnati real-estate broker identified as the nation’s chief urban problem “the undue acceleration of population flight away from city centers causing rot and decay at their cores.”101 At the beginning of the decade, the Urban Land Institute, the research arm of the National Association of Real Estate Boards, issued a report, Decentralization: What Is It Doing to Our Cities? that explained the numerous “adverse results of decentralization.” In 1941 the American Institute of Appraisers added lectures on “the disintegration and decentralization of urban communities” to its summer courses. The same year, a transportation consultant summed up the issue troubling many: “The basic question is whether we can retain the city as a central market place, and at the same time decentralize residences to the extent that everyone lives out in the suburbs or country.”102