| 2 |  |

Reinforcing the Status Quo |

In 1956 architect-planner Victor Gruen presented his well-publicized and much lauded plan for rebuilding the central business district of Fort Worth. It was the culmination of twenty years of thought by American urban leaders and planners about how to thwart commercial decentralization and reinforce the existing single-focus city. In the plan, centripetal expressways carried traffic to a highway that looped around downtown Fort Worth. At each exit of the loop ample parking garages accommodated incoming drivers who then could walk the remaining few blocks to work or shopping in the compact, pedestrian business district. Although praised as innovative, Gruen’s plan reflected the postwar desire to preserve the existing metropolis rather than radically change it. Accepting the orthodox wisdom of urban observers, Gruen posited that “just as the human body is dependent upon the heart for its life-giving beat so is the modern city dependent upon its heart—the central business district—for its very life.”1 Imagining the rebuilt Fort Worth of 1970, Gruen wrote of the office worker speeding conveniently to work in a downtown office tower, the department store executive enjoying vigorous downtown sales, and the housewife shopping downtown, lunching at a new tearoom, and taking in a movie before riding home with her husband. Fort Worth’s future downtown was, then, the idealized downtown of the past, a hub of white-collar office workers, prosperous department store moguls, and consuming middle-class housewives. The downtown of the future was a white, middle-class domain; only well-dressed white people inhabited the drawings accompanying Gruen’s text. Dark faces were absent from his vision of the future.

For Gruen and many others in the postwar years, the utopian city was nothing but a reinforced, cleansed version of the past. Policy makers and planners were not dreaming of a centerless Broadacres or a racially heterogeneous city. Instead, the desired metropolis of the future had a dominant downtown, an invisible black populace, and a female population dedicated primarily to consumption rather than production. Conservation, not revolution, was the goal of urban leaders in the late 1940s and first half of the 1950s who sought to perpetuate the existing single-focused metropolis. Moreover, the majority of Americans remained dedicated to the segregated black–white lifestyle, especially in the area of housing. Between 1945 and the mid-1950s, discourses on commercial re-vitalization dominated much of the rhetoric about cities. During the same years, maintenance of the color line, especially the line between black and white neighborhoods, produced sporadic violence, bitter attacks, and policies dedicated to keeping African Americans literally in their place. This decade witnessed an acceleration in suburbanization. But in the years immediately following World War II, massive housing subdivisions were the most notable manifestations of suburban development, perpetuating the earlier pattern of residential and industrial dispersion. The vast housing tracts renewed the suburban trend so evident in the 1920s.

Despite the designs of Gruen and others to maintain rather than revolutionize the existing metropolitan lifestyle, there was change. Efforts to recentralize and bolster the commercial core did not halt the gradual shift of retailing to the suburbs. There was incremental racial change, with some opportunities opening for urban blacks; racial boundaries were not necessarily insuperable. Moreover, the suburban migration offered portents of a new way of life. Yet the vision of Victor Gruen was not that of Frank Lloyd Wright. The metropolitan revolution would not transform America overnight. Inherited expectations held a firm grip on the American mind, and the nation would only slowly yield to the wave of centrifugal and racial change.

Bolstering the Center

During the late 1940s and the first half of the 1950s, earlier concerns about decentralization became more acute, but a growing corps of business and political leaders as well as planners seemed confident that the urban core would hold and emerge as a revitalized focus of metropolitan life. Committees and commissions mobilized the business community, mayors and highway engineers presented plans for expressways and parking garages, and planners unveiled schemes for core projects that would ensure that downtown remained the one real hub of the metropolis. Of special concern was the middle class, which was moving farther from the urban core but whose dollars and job skills were essential to downtown’s continued supremacy. The decade following World War II was a period of trepidation about the future of the central business district but also an era of high hopes and big dreams. Certainly very few policy makers had given up on downtown or accepted the notion of an alternative to the single-focused metropolitan lifestyle that had developed during the previous century.

For anxious urban leaders, Pittsburgh was the uplifting symbol of urban redemption from blight and decay. At the close of World War II, few cities had such a benighted reputation as the soot-and smoke-ridden capital of America’s steel industry. In 1946 a national magazine commented on “the multiple scuttles of soot one must devour per annum as a part of the price of living in Pittsburgh,” where conditions were “hellish, tormenting, disease-abetting and spirit-wilting.”2 Reportedly, wives of would-be junior executives opposed transferring to the Steel City because of the community’s dirt and gloom, and there were rumors that corporate headquarters were considering leaving the city. Quite simply, Pittsburgh was a prime example of what was wrong with America’s urban hubs.

During the decade following World War II, the city’s business leaders, working through the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, joined with the city’s dynamic mayor to give Pittsburgh a face-lift. Tough antismoke ordinances forced businesses, households, and railroads to rely less on sooty bituminous coal and cleared the skies over the city. By 1950, a local leader could claim that “visibility [was] up by almost 70 percent, laundry and painting bills [had] gone down, buildings [had] been cleaned, and the whole aspect of the community [was] more cheerful and bright.”3 Additionally, the Allegheny Conference and its allies in city hall combined to clear the blight-ridden Point area, the gateway to downtown Pittsburgh. At the juncture of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers, the Point was a shabby mix of railroad yards and aging warehouses; it seemed to sum up the image of Pittsburgh as an over-the-hill industrial city. During the late 1940s and first half of the 1950s, however, the state and city acting cooperatively leveled the fifty-nine-acre tract and transformed thirty-six acres into a state park on the site of the historic pre-Revolutionary forts Duquesne and Pitt. The remaining twenty-three acres became Gateway Center, where three gleaming stainless-steel office towers opened to tenants in 1952 and 1953 and during the following five years were joined by a new Hilton hotel, a state office building, and the telephone company headquarters (figure 2.1).

Meanwhile, in 1952 the forty-one-story Mellon–U.S. Steel Building opened in the heart of downtown Pittsburgh, as did a twenty-two-story hotel and the city’s first modern downtown apartment house. The following year, the thirty-one-story Alcoa Building, the nation’s first aluminum skyscraper, was dedicated, and in 1955 the completion of Mellon Square Park rounded out a decade of achievement for downtown Pittsburgh (figure 2.2). Lauded by an Allegheny Conference publication as “a crowning achievement in Pittsburgh’s Renaissance,” Mellon Square was a nine-acre park in the center of the business district resting on top of a six-level, thousand-car underground parking garage. “The Park is an array of colorful fountains, fountain pools, cascades, terrazzo walks, and inviting granite benches,” the conference boasted. “There are thousands of trees, plants, shrubs and flowers of many different varieties planted within its borders.”4 With thousands of flowers, cascading clear water, and shining aluminum and stainless-steel towers, the new core of Pittsburgh was the very antithesis of the image of the grimy old hub. It was visual proof that American cities could reverse themselves in a single decade.

FIGURE 2.1 Construction and demolition in Gateway Center, Pittsburgh, ca. 1951. (Library and Archives Division, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh)

FIGURE 2.2 Mellon Square with the Alcoa Building in the left background, Pittsburgh, 1956. (Library and Archives Division, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh)

Pittsburgh’s leaders, however, did more than clear slums and erect skyscrapers. They also sought to adapt downtown to the automobile age. The chief highway project was the Penn-Lincoln Parkway, designed to provide expressway access to the central business district. Construction also began on the double-deck Fort Pitt Bridge leading into downtown, and work on the 3,600-foot Fort Pitt Tunnel was scheduled to commence in late 1956. This tunnel would burrow under Mount Washington and funnel traffic from the southern suburbs to the central business district. In addition, the number of off-street parking spaces in downtown Pittsburgh increased by 40 percent between 1946 and 1956. In the latter year, the Allegheny Conference claimed that almost one-fourth of the central business district had been rebuilt since the end of the war, a figure indicative of Pittsburgh’s resurgence.5 With new skyscrapers, expressways, and parking garages Pittsburgh’s leaders had reinforced the urban core, ensuring that at least momentarily it would remain a suitable and convenient destination for middle-class workers and consumers.

The national media spread the Pittsburgh story to urban dwellers throughout the nation, giving hope to those seeking to preserve the traditional metropolis. In 1949 Newsweek reported that Pittsburgh was “no longer the smoky city or the tired milltown, but an industrial metropolis with a new bounce, with clear skies above it and a brand-new spirit below.”6 The same year, Architectural Forum called Pittsburgh “the biggest real estate and building story in the U.S. today.”7 In 1952 the Washington Post presented the Steel City as a model of revitalization that could teach some lessons to the nation’s capital. The Post told its readers that “the spirit of Pittsburgh’s rebirth, and it is hardly less than that, could be duplicated here.”8 At the close of the 1950s, a travel magazine summed up the urban Cinderella story when it labeled Pittsburgh “the city that quick-changed from unbelievable ugliness to shining beauty in less than half a generation.”9

Responding to the much publicized success of Pittsburgh, business leaders in other cities organized their own versions of the Allegheny Conference. In 1948 the Greater Philadelphia Movement became the voice for Philadelphia’s business elite and, together with the broader-based Citizens’ Council on City Planning, pushed for the city’s revival. In the early 1950s, Saint Louis’s twenty-five most powerful business figures formed Civic Progress, Inc., to jump-start the Missouri metropolis, and in 1954 one hundred of the largest corporations in Cleveland established the Cleveland Development Foundation “to advance urban development through joint leadership of Cleveland business.”10 The following year, the chief executives of the one hundred largest firms in the Baltimore area founded the Greater Baltimore Committee, whose statement of purpose announced: “Our watchword should be action now…. We want sound planning, but we want action to implement the plans, and we want it now, not at some future time when we may not be around to see it.”11

Leading metropolitan newspapers also called for immediate action and publicized projects that could reverse decentralization. In 1950 the St. Louis Post-Dispatch published a series of articles titled “Progress or Decay? St. Louis Must Choose.” The initial installment in the series warned that if Saint Louis remained “content to jog along without aggressive action—there lurk[ed] decay, squalor, the threat of steady decline” and the promise that it “would take a back seat among American cities.”12 Although the Post-Dispatch series discussed a long list of necessary improvements, it made clear that recentralization and reinforcement of the urban core were essential to the future of the metropolis. “Without a vigorous Downtown, St. Louis loses its chief economic reasons for existence,” the newspaper contended; “without a vigorous St. Louis, the whole metropolitan district falters and fails—economically, culturally, physically.”13 Two years later, the Washington Post copied the Post-Dispatch format in an eighteen-article series with the unoriginal title “Progress or Decay? Washington Must Choose!” The Post asked its readers: “Shall downtown Washington … continue its drift into blight, its business importance decreasing, its traffic arteries ever hardening, its slums daily growing? Or shall Washington make that massive frontal attack necessary to stop deterioration [and] to make downtown Washington a better, finer, more attractive place to live, work and shop?” Clearly the Post was on the side of progress rather than decay and was using its pages to mobilize local forces for the essential massive attack. Ending the series on an upbeat note, the newspaper concluded that “the story of the response of America’s biggest cities to the crisis of downtown blight today is a heartening one for those who believe that democracy is a living thing in our vast urban areas.”14 In other words, the signs of redemption abounded; if willing to take action, Washington residents could share in the wave bringing new life to central business districts. Like the Greater Baltimore Committee, however, the Washington Post believed in action now. Washington had to choose progress and begin at once to reinforce its faltering core.

In one city after another, then, the message was similar. Pittsburgh had acted and achieved marked change; now the other cities had to do likewise. The single-focus metropolis could survive, and swarms of middle-class Americans and their dollars could still be attracted to the core. If major cities chose progress, the middle-class housewife, white-collar office worker, and department store executive of the future would continue to find the downtown the most exciting and lucrative locale in the metropolis, the unrivaled center of metropolitan life.

Those who dreamed of revitalization shared a vision of what needed to be done. Like Pittsburgh, cities had to plan and build expressways and massive parking facilities that would draw workers and shoppers to the central business district. In the automobile age, as in the streetcar era, downtown had to remain the most accessible location in the metropolitan area. Long before the federal government elected to finance the massive 41,000-mile interstate highway program in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, cities across the nation were acting to create up-to-date highway systems. In the early 1940s, Los Angeles had already completed the Arroyo Seco and Cahuenga parkways, two links in its proposed freeway system, and by 1957 it could boast of 223 miles of limited-access highways.15 In 1946 Detroit’s city council authorized acquisition of rights-of-way for the Edsel Ford and John C. Lodge radial freeways (figure 2.3); by 1953, $105 million had been spent or committed for the expressways. As of 1953, the Detroit Municipal Parking Authority, created in 1948, was helping the central city further adapt to the automobile by maintaining four city-owned parking lots. Detroit’s mayor predicted that “highways would lure residents of neighboring areas to shop [in Detroit]” and would “retard the decentralization of business into suburban areas which pay no Detroit taxes.”16 The leaders of Kansas City, Missouri, agreed with this sentiment; that city’s master plan of 1947 proposed a system of expressways radiating from a loop highway encircling the central business district with parking lots conveniently adjoining the loop. The same year, Kansas City voters approved a $12 million highway proposal.17 Meanwhile, in 1947 Philadelphia’s city council ordered the drafting of plans for the Schuylkill Expressway, which would bring auto-borne employees and consumers from the northwestern fringe of the metropolitan area to the central business district. Six years later, construction began on this downtown feeder. During the early 1950s, Boston had begun work on the Central Artery, intended to accelerate the flow of traffic coming into the aging New England metropolis, and Bostonians were arguing over plans for the construction of a parking garage under the Boston Common.18

FIGURE 2.3 Construction of the John C. Lodge Expressway in Detroit, 1950. (Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University)

The central city, however, needed more than expressways and parking garages. It needed a revival in downtown construction and the creation of attractive new buildings where middle-class Americans could work, shop, and live. Although most cities could not match Pittsburgh’s Gateway Center, there were encouraging signs of massive private investment in other central business districts. In 1947 promoter Arthur Rubloff unveiled his plans for a $200 million project to redevelop Chicago’s upper Michigan Avenue as a magnificent mile of “office buildings, smart shops, hotels, and apartment buildings” that would enable the avenue to fulfill its “destiny and become one of the world’s most beautiful streets.” Saks Fifth Avenue and Bonwit Teller were planning to move onto the street, which during the postwar era would achieve its destiny and realize Rubloff’s dreams.19 In 1952 the Pennsylvania Railroad began demolition of its grim downtown Philadelphia viaduct in preparation for the construction of the $123 million Penn Center, a gleaming new complex of two office towers, shops, and a twenty-two-story hotel.20 In 1957 U.S. News & World Report recorded that since 1946, Dallas’s “skyline has been revolutionized. Twenty-five big office buildings have risen downtown, four more are under construction.”21 In 1954 the forty-story Republic National Bank Building was completed, and in 1955 construction began on the equally tall Southland Center. Between 1954 and 1959, office space in downtown Dallas was increasing at the rate of 1 million square feet a year.22 Meanwhile, New York developer William Zeckendorf was transforming Denver, where in the mid-1950s he built the twenty-two-story Mile High Center office building as well as one of the nation’s largest department stores, complete with underground parking for 1,200 automobiles.23

Nowhere was there such an outpouring of private investment as in Zeckendorf’s hometown. During the decade after the war, 856 new office buildings rose in Manhattan, and in the mid-1950s New York was adding new office space at the pace of about 2 million square feet a year. In 1952 the sleek, glass-skinned Lever Building opened on Park Avenue, and other glass- and-steel towers would appear along the once residential thoroughfare during the following few years. In 1953 Time proclaimed: “Manhattan, written off long ago by city planners … because of its jammed-in skyscrapers and canyon-like streets, has defied and amazed its critics with a phenomenal postwar building boom.”24 By 1957, the chair of New York’s planning commission optimistically observed: “There are indications that not only is the flow from the city to the suburbs slowing, but that the reverse flow is picking up.” He claimed that “enough of a change is taking place to make it quite clear that we are moving into a new and significant situation.”25

Although fearful of losses to suburban retailers, downtown department store moguls also expressed a faith in the future of the central business district and were spending millions of dollars that reinforced the centripetal pull of the urban hub. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the Jordan Marsh department store erected a new building in downtown Boston, Halle’s in Cleveland expanded its central emporium, Neiman-Marcus doubled the space of its downtown Dallas store, and Frederick and Nelson of Seattle spent $9 million to double its downtown selling space. Moreover, Business Week reported that Gimbel’s in New York City was spending $5 million on its downtown facility and Chicago’s Marshall Field Company was investing $19 million in renovations and improvements.26 A survey conducted in Columbus, Ohio, Houston, and Seattle in the early 1950s found that consumers still preferred downtown to suburban shopping centers. In sixteen of the twenty-three “shopping satisfaction factors,” downtown was the preferred destination, ranking especially high on the factors of “variety of styles and sizes” and “variety and range of prices and quality.”27 As downtown retailers constantly reminded their customers, the central business district had more of everything. To find what one wanted in clothing or furniture at a reasonable price, one still went downtown. “People still like to shop downtown,” commented a Philadelphia department store executive in 1954. “If we give them attractive stores with good stocks, they will continue to shop downtown.”28

The millions invested by private entrepreneurs in department stores and office towers seemed to prove that there was still a good deal of life in the urban core. To reinforce the private assault on decentralization, however, some downtown leaders favored federal aid to redevelop the inner city. The result was Title I of the Housing Act of 1949, which authorized the federal government to pay for two-thirds of the net cost of purchasing and clearing blighted property for the purpose of redevelopment. Localities were to provide the other third. The funding was restricted to blighted properties that were predominantly residential or would be redeveloped predominantly for residences. In other words, Congress seemed to intend that the program would encourage slum clearance and provide new housing in the urban core. Although the land could be used for low-income public housing, proponents of inner-city revitalization envisioned new apartment complexes for middle-class urbanites. These complexes would supposedly anchor the middle class in the central city and ensure that their tax and retailing dollars did not end up in suburban coffers. The goal was, then, to preserve the established focus of the metropolis. With federal help, the traditional center would supposedly remain central to metropolitan life.

During the early 1950s, Title I was of limited significance compared with such privately financed projects as Penn Center, the massive private investment in Manhattan’s office buildings, or the private and state–clocal government partnership responsible for the redevelopment of downtown Pittsburgh. From 1950 through 1956, the cost of construction begun under federal redevelopment amounted to a total of only $247 million.29 By comparison, in 1955 alone urban governments sold $310 million in highway construction bonds, and between 1945 and 1957 almost $4 billion was invested in residential and office building construction in New York City.30

Although the federal government was a late recruit to the battle against decentralization, it did generate some projects in the early 1950s and certainly heightened the expectations for a reinforced and revitalized urban core. During the first years of the Title I program, New York City and its construction czar, Robert Moses, received the lion’s share of the federal funds. A domineering, aggressive figure with a passion for reconstructing New York City, Moses quickly took advantage of the federal funds and erected apartment complexes primarily to house those who had too much money to qualify for public housing but too little cash to rent an apartment on the affluent Upper East Side of Manhattan. By the close of 1959, Moses’s Committee on Slum Clearance had completed 7,800 Title I dwelling units, providing shelter for thousands of middle-income New Yorkers who otherwise might have migrated to the suburbs, beyond the reach of the city’s tax collector and far removed from its retailers.31

Elsewhere, federally financed schemes proceeded more slowly but offered hope to those who sought to retain a middle-class presence in the inner city. In Detroit, the Lafayette Park complex of apartments and townhouses was intended to draw a more affluent population to the blighted core. As of the mid-1950s, there was still debate whether the project should include public housing for displaced black residents or be exclusively middle to upper income. An Urban Land Institute panel meeting in Detroit in 1955 recommended the latter, urging that the renewal effort “be directed towards a step-up in accommodations, not downwards to the bottom of the income group. Detroit has a great mass of good workers able to pay economic prices,” the panel commented. “These are the great, solid heart of your city’s life. Orient your program accordingly.”32 Other cities followed this same advice when developing federal renewal sites. Chicago’s Lake Meadows project on the near South Side was designed for middle-class tenants, as was Saint Louis’s downtown Plaza Square apartment complex. In Los Angeles, planners were proposing the clearance of the old wooden houses in the Bunker Hill district, adjacent to downtown, for the construction of high-rise apartments and the relocation of its low-income residents to public housing in largely Hispanic Chavez Ravine, a low-density shantytown. Land close to the urban core was supposedly too important to the economic interests of the city to remain in the hands of the poor. They had to be removed so that the core could survive as the great generator of tax dollars and prosperity. To the north, San Francisco authorities were proceeding slowly on a scheme to clear the Western Addition, an area with a large black and Japanese American population.33 As yet, there were more proposals than actual blueprints and certainly more blueprints than construction, but Title I seemed to open the door of the federal treasury to those who sought to recentralize the American metropolis. And by the mid-1950s, many urban leaders were trying to make their way through that door.

Not only were central-city leaders using private and federal funds to reinforce downtown’s dominant position, but they were mobilizing to protect major educational institutions threatened by blight and the poor African Americans that whites associated with blight. For example, in New York City’s Morningside Heights district, Columbia University’s leaders feared the encroachment of nearby Harlem and the resulting social and ethnic change that might repel both prospective students and faculty. Who, after all, would want to attend or work at a university in a slum? By 1950, about 10 percent of the neighborhood’s population was black, and another 10 percent were recent immigrants from Puerto Rico. Landlords were converting formerly middle-class apartments into single-room-occupancy hotels that attracted low-income blacks and Puerto Ricans, including prostitutes and drug addicts. In 1947 in response to the perceived threat to their neighborhood, Columbia and other nearby institutions joined to form Morningside Heights, Inc., to curb the advance of Harlem and stabilize the social and ethnic composition of the community. In its war on blight, Columbia quite simply sought to make Morningside Heights safe for white, middle-class life. Among the first projects backed by Morningside Heights, Inc., was Morningside Gardens, a Title I middle-income apartment complex that was ethnically mixed but solidly middle class.34

Meanwhile, the University of Chicago was embarking on an even more ambitious program dedicated to saving its neighborhood for the middle class. Located in the Hyde Park district on Chicago’s South Side adjacent to Bronzeville, the university was in the path of the expanding African American community; by the late 1940s, an invasion of poor blacks seemed imminent. Responding to this threat, in 1952 the university established the South East Chicago Commission, which drafted a plan for spot clearance of the area’s most blighted structures and rehabilitation or conservation of the remaining buildings. The idea was to eliminate dilapidated housing with rents affordable to low-income blacks and upgrade or preserve the remaining dwelling units for middle-class occupants. In 1955 demolition began, and the following year the commission secured approval for $26 million in federal urban renewal funds. The neighborhood was not to be lily-white; middle-class blacks were not excluded. But Hyde Park was to remain a bastion against lower-class invaders. One comedian joked: “This is Hyde Park, whites and blacks shoulder to shoulder against the lower classes.”35

In Chicago and New York City as well as Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, urban leaders were, then, attempting to hold the line against blight and the social transformation that accompanied the advance of this dread malady. Downtown had to remain a magnet for middle-class dollars, and Columbia and the University of Chicago had to remain appealing to affluent white students and faculty. Millions of dollars were being spent to ensure that the central city and its central business district remained the dominant heart of the metropolis. And so far the centrifugal forces of the automobile age had not destroyed the significance of the urban center in American life. In 1954 two urban geographers confidently observed that downtown “is so familiar to the average citizen that he is likely to take it for granted.”36 Whether the urban core would remain so familiar to the average American ten or twenty years in the future was a question that dominated the thinking of central-city leaders.

Holding the Color Line

Equally troubling to many urban Americans was the question of whether the color line would hold and white neighborhoods remain white. The migration of southern blacks to northern and western cities continued unabated during the decade following World War II as the possibility of better jobs and higher incomes attracted an unrelenting wave of African Americans. The result was a marked darkening of the complexion of America’s central cities. In New York City, the black proportion of the population rose from 6.1 percent in 1940 to 14 percent in 1960; in Newark, it soared from 10.6 to 34.1 percent; in Philadelphia, the increase was from 13 to 26.4 percent; in Detroit, the African American share went from 9.2 to 28.9 percent; and in Chicago, it rose from 8.2 to 22.9 percent. In the late 1950s, Washington, D.C., became the first major American city with a black majority; the trajectory in other cities pointed to African American majorities within the next two decades. On the West Coast, black predominance seemed less imminent, but the African American share of the populations of San Francisco and Oakland skyrocketed tenfold between 1940 and 1960, from 1.4 to 14.3 percent.

In the minds of most white urban dwellers, all these figures added up to bad news. They viewed the black migration as an invasion threatening their previously homogeneous neighborhoods and the property values of their homes. Moreover, such sentiments were not confined to the southern or border states but were also prevalent in the far northern reaches of the United States, where relatively few blacks had yet penetrated (figure 2.4). In 1946 a poll found that 60 percent of Minnesotans surveyed believed that blacks should not “be allowed to move into any residential neighborhood where there is a vacancy,” and 63 percent responded “no” to the question: “If you were selling your home and could get more from a Negro buyer, would you sell?”37 In 1951 a poll of Detroit residents found that 56 percent of the whites surveyed favored residential segregation. An African American journalist summed up the postwar attitude when he observed, “The white population … has come to believe that it has a vested, exclusive, and permanent ‘right’ to certain districts.”38

FIGURE 2.4 Antidiscrimination billboard sponsored by the Governor’s Inter-Racial Commission in Minnesota, 1948. (Minneapolis Star Journal Tribune, Minnesota Historical Society)

During most of the 1940s, racial restrictive covenants appeared to be the best defense against the perceived racial invasion. But in 1948, the United States Supreme Court, in Shelley v. Kraemer, held such covenants to be unenforceable. If courts enforced the racial restrictions, they would deprive blacks of equal protection of the laws, in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Thus white homeowners could no longer rely on the courts to evict black “invaders” from restricted properties. A serious breach had developed in the neighborhood defenses of the black–white city.

In the wake of Shelley v. Kraemer, however, the forces of segregated neighborhoods did not lay down their arms and abjectly capitulate. Instead resistance continued. Most realtors remained reluctant to sell or rent homes in white neighborhoods to blacks. Until 1950 the code of ethics of the National Association of Real Estate Boards specified that “a realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood … members of any race or nationality … whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in the neighborhood.”39 That year, the association modified this racist code, but most “reputable” realtors still deemed introducing blacks into white neighborhoods to be unethical and undesirable. “Ethical” operators steered blacks to black neighborhoods and whites to white areas.

The federal government likewise did not threaten the forces of residential segregation. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) insured residential mortgages, guaranteeing to reimburse lenders should mortgagees default on their payments. Viewing racially mixed areas as bad investments, the FHA encouraged the adoption of racial restrictive covenants throughout the 1940s and would not insure mortgages on properties in neighborhoods where both blacks and whites lived. At the close of 1949, the FHA adopted a new policy of refusing to guarantee mortgages on homes subject to racial restrictive covenants finalized after February 15, 1950, but the federal agency continued to prefer white suburban subdivisions to mixed-race areas in the central cities. As of 1952, less than 2 percent of the 3 million dwellings with FHA mortgage insurance were available to blacks.40

Racial labeling in real-estate advertisements reinforced the discriminatory practices of realtors and lenders. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, the real-estate advertisements in many metropolitan newspapers identified whether the available house or apartment was for a “colored” occupant.41 Blacks were expected to respond to only the advertisements marked “colored.” Other residences in the listings were off-limits.

Neighborhood improvement associations also remained vigilant in the battle to protect white areas. On the South Side of Chicago, the Fernwood-Bellevue Civic Association, the Calumet Civic Association, and the South Deering Improvement Association fought the movement of black tenants into previously all-white public-housing projects. In 1948 a coalition of homeowners’ associations in Detroit urged its members to “get busy on the phone” and tell real-estate brokers who sold houses to African Americans what they thought about the brokers’ willingness to accommodate race invaders. Following the Shelley v. Kraemer decision, Detroit’s Palmyra Home Owners’ Association suggested new covenants that referred vaguely to “undesirable peoples” rather than specifically mentioning race.42 In 1952 the A. P. Hill Civic Club of Memphis posted signs in the neighborhood reading “not for sale to Negroes” after some inquiries from blacks about purchasing homes in the area. Moreover, the club convinced city authorities to require developers to erect a steel fence to separate existing black and white residential zones in the North Memphis district.43 Houston’s Riverside Home Owners Protective Association organized following the purchase of a home in the neighborhood by an African American. The buyer was subjected to threatening telephone calls, and the Houston Chronicle reported that “several hundred white neighbors gathered in front of the house and a spokesman suggested ‘If you leave this neighborhood you will live longer and be happier.’”44

Meanwhile, twenty organizations in Los Angeles banded together to bring legal action intended to ensure that restrictive covenants would continue to pose some threat. In Barrows v. Jackson Mr. and Mrs. Edgar W. Barrows brought suit for damages against their neighbor Leola Jackson, who had signed a restrictive covenant in 1944 and then in 1950 sold her property to blacks. Because of the Shelley ruling, the Barrows could not oust the black purchasers from their new home, but through their suit for damages they sought to coerce Jackson and other whites to adhere to their covenants. Not only did such Los Angeles homeowners’ groups as the Vermont Square Neighbors, Harvard Neighbors Association, and Lafayette Square Improvement Association support the Barrows, but on appeal to the United States Supreme Court in 1953 they were joined by an improvement association in San Francisco, another in Kansas City, twenty-four associations in Washington, D.C., and sixteen in Saint Louis.45 Despite this showing by white homeowners’ groups across the nation, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Jackson, handing the improvement associations yet another judicial defeat.

In Atlanta, the city’s leaders sought to avoid lawsuits and neighborhood clashes by defining acceptable zones of expansion for the growing black population. In 1947 black developers and community leaders specified six areas reserved for new housing for African Americans, and white city officials privately agreed to the plan. To further avoid conflict, in 1952 Atlanta mayor William Hartsfield appointed the biracial West Side Mutual Development Committee to oversee peaceful expansion of the black population and to determine racial dividing lines. In effect, the committee was charged with partitioning the city’s west side into white and black zones. Moreover, through the construction of new roads the city sought to create more effective racial boundaries. In 1954 Hartsfield urged immediate action on an access road to serve as a racial frontier. “As you probably know,” the mayor told his construction chief, “the bi-racial committee is trying to assure residents of Center Hill and Grove Park that the proposed access road will be a boundary which will protect them as Negro citizens move farther out.” The director of the planning commission reiterated this sentiment when he observed: “If the line can be stabilized, a potentially explosive situation will have been prevented, and both racial and political attitudes will be saved strain.”46 Thus to avoid strain and maintain stability, Atlanta’s leaders believed that the residential color line had to be preserved. The result, however, was confinement for Atlanta’s blacks. Although African Americans had negotiated the right to additional territory during the postwar decade, by 1959 they constituted 35.7 percent of the city’s population but occupied only 16.4 percent of the land.47

Dedication to existing racial boundaries also thwarted the designs of public-housing officials seeking to build projects in outlying white areas. Low-rent public projects meant an influx of poor tenants, many of them black, and white homeowners were adamantly opposed to this threat to their property values and social status. In 1949 one of the major issues in Detroit’s mayoral election was the prospect of outlying public-housing projects. Conservative Albert Cobo swept to victory, and the new mayor lived up to the expectations of many white homeowners when he announced: “I WILL NOT APPROVE Federal Housing Projects in the outlying single homes areas.” According to Cobo, “When people move and invest in a single-family area, they are entitled to consideration and protection.”48 When in 1952 Cleveland housing officials proposed a project in the white Lee-Seville area, the neighborhood rose in revolt. “The community is divided, supposedly on the question of whether there should be more public housing or not,” commented the city’s public-housing director, “but the actual question is whether or not public housing should be built where both Negroes and whites could live together as American citizens should.”49 Cleveland’s city council sided with opponents to the Lee-Seville scheme and resolved that in the future it would review for approval or rejection each public-housing proposal. In the mid-1950s, Chicago’s city council took similar action to curb housing authority discretion and subjected proposed public-housing projects to the veto of the council member for the area affected.50 This spelled doom for projects in outlying white areas. When in 1956 the Philadelphia housing authority unveiled plans for twenty-one public-housing sites, including some in white neighborhoods, the uproar was predictable. Again, most of the proposed projects were never built.51 Throughout the nation, public housing was increasingly concentrated in inner-city, black neighborhoods. Massive, high-rise projects housing thousands of African Americans would become the new ghetto.

Sometimes defenders of the color line moved beyond appeals to city councils, lawsuits, and harassing telephone calls and resorted to violence. During the postwar decade, there were no full-scale race riots comparable to the Detroit outburst of 1943, but violence arising from fears of racial invasion was an ugly fact of urban life. This was especially true in Chicago, where working-class Catholics of southern and eastern European ancestry felt threatened by racial change. With most of their assets in their homes and limited housing options because of their modest incomes, they felt especially vulnerable. “I was born and raised on the near North Side,” testified a South Side white woman on the verge of tears. “My father had to sell his home at a big loss when the Negroes moved into the neighbor-hood. Now are we going to have the same thing happen here?”52 Blacks needed additional housing, and whites could ill afford the perceived threat to their property values. The combination was volatile.

One violent incident after another disrupted Chicago’s South Side. In December 1946, a mob estimated at between 1,500 and 3,000 persons attacked police and vandalized property at Airport Homes, a veterans’ housing project that was admitting black tenants. In August 1947, African Americans moved into the Fernwood Park public-housing project, igniting mob action by whites in the neighborhood. For three successive nights, crowds of whites gathered in the area around the project, stoned passing cars, including police cars, and attacked streetcars and buses carrying blacks. On the third night, 1,000 policemen were deployed to protect the Fernwood project and suppress a “howling screaming mob” of 1,500 to 2,000 whites.53 In July 1949, the target of violence was a two-family home purchased by a black man in the white Park Manor neighborhood. In the aftermath of the incident, a city official summed up the damage: “All of the front windows with the exception of a few basement windows had been broken, and the brick front of the house was scarred and pitted by numerous bricks thrown against it.” “We barricaded the doors with furniture and put a mattress behind it,” recounted the wife of the black owner. “We crawled around on our hands and knees when the missiles started coming in through the windows…. Then they started to throw gasoline-soaked rags stuck in pop battles.” The same year, the Englewood neighborhood exploded when rumors spread that a house was being “sold to niggers.”54

The violence did not abate in the 1950s. In 1953 whites responded violently when the first blacks moved into the Trumbull Park public-housing project. At the height of the disturbance, a mob of two thousand whites gathered, and the now all-too-common stoning of windows, cars, and buses ensued as well as the throwing of lighted torches into the apartment of the hated race invaders. When additional blacks moved into the project, several women, according to the city’s human relations commission, “literally hurled themselves, first at a truck loaded with the newcomers’ furniture, and later at a new car driven by the head of one Negro family.” One feisty “gray-haired woman of about 65 fell prostrate in front of the car…. When the halted car began to inch ahead, the woman clung to its front bumper.”55 The neighborhood newspaper fueled the anger of the Trumbull Park protesters when it editorialized: “The Negro can turn his neighborhood into a slum overnight…. Most of them live like savages…. Why don’t they stay where they belong?”56 Chicago’s endemic racial violence persisted through the mid-1950s. The Chicago Urban League reported a total of 164 incidents of racial violence in 1956 and 1957, most of them in the transitional areas where African Americans were expanding into formerly all-white neighborhoods.57

The most highly publicized racial housing incident of the early 1950s was across the city limits in the adjacent municipality of Cicero. In July 1951, Illinois’s governor had to declare martial law and dispatch the National Guard when a black man attempted to move into an apartment in the white ethnic community. From Tuesday to early Friday morning, whites attacked the offending apartment building with stones and burning torches. They ripped out walls and radiators, threw furniture out of windows, and tore trees up by their roots.58 In what proved an effective display of racial hatred, Cicero whites made clear that their town was off-limits to blacks and would remain so.

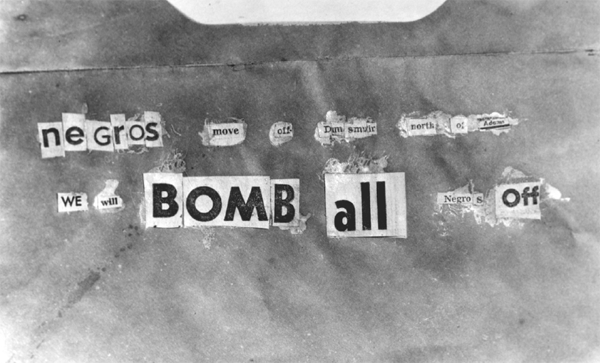

The Chicago area, however, could not claim a monopoly on racial violence. Elsewhere, attempted breaches of the color line ignited harsh defensive action. Between the autumn of 1945 and early 1950, Detroit’s Lower West Side suffered eighteen racial incidents. Neighborhood residents set fire to a house recently purchased by a black man, forced two African Americans from apartments in the area, ripped the porch from a black-owned home, and smashed thirty-five windows in two houses.59 In 1949 and 1950, a rash of dynamitings targeted the homes of African Americans who challenged the residential segregation prevailing in Birmingham, Alabama. Over a seventeen-month period in 1950 and 1951, thirteen dynamitings struck black homes in Dallas.60 In 1951 white segregationists resorted to a series of dynamitings in order to dislodge blacks from a new housing project, Carver Village, in northwest Miami. The wife of Miami’s mayor received telephone calls threatening that “if we didn’t get the Negroes out of Carver Village within a month they would bomb it to pieces.”61 Then in 1952 a number of bombings rocked the houses of African Americans in a lower-middle-class neighborhood of Kansas City, Missouri.62 Across the nation, whites were expressing a similar message (figure 2.5). They did not intend to yield their neighborhoods without resistance.

Yet gradually African Americans gained new territory, and the boundaries of the black ghetto in one city after another moved outward. Dynamitings and diatribes could not contain the black population, and racial boundaries were changing. Blacks moved farther south in Chicago and won new territory on the west side. The Bedford-Stuyvesant ghetto in Brooklyn absorbed new blocks, Cleveland’s east side African American community spread further eastward, and Atlanta’s blacks extended their west side domain. What did not change, however, were attitudes about racially mixed neighborhoods. Block by block, districts shifted from all-white to all-black as white residents yielded territory but did not shed their aversion for a racially heterogeneous lifestyle. In 1955 America’s cities were, then, as segregated residentially as in 1945. The racial geography of urban America had changed somewhat, but the color line between blacks and whites remained strong. The black–white city of 1945 was very much alive in 1955.

FIGURE 2.5 Threatening note found at the site of a home bombing in Los Angeles, 1952. (Herald Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library)

While the residential walls between black and white remained strong, there was only modest improvement in job opportunities for African Americans. In most cities, blacks remained barred from positions in which they would have to interact with white consumers. Fearful of offending customers, many employers confined blacks to out-of-sight janitorial, stock-handling, and maintenance duties. Thus investigators working for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People reported that in Washington, D.C., “occupations such as laundry truck drivers, ticket sellers in bus and railroad stations, desk clerks in hotels, and distributors of bakery and milk products” were as off-limits to African Americans in 1957 as in 1946. Those employees who delivered laundry, milk, and baked goods to Washington housewives and sold tickets and lodging to travelers in depots and hostelries had to be white. Moreover, other than the city’s one black-owned bank, no financial institution in Washington employed an African American teller.63 In 1951 an investigation of a major San Francisco bank found that there was only one black woman among the five hundred employees. The San Francisco investigators also found that blacks were notably absent from the serving staff of a popular restaurant chain but were employed as dishwashers, “cleanup men,” and kitchen helpers.64 As late as 1959, there were only eighty-six blacks among the twelve hundred employees of Detroit’s major clothing stores for men, and no African American held a managerial or sales position.65

In the postwar decade, blacks continued to find unskilled and semiskilled factory jobs, but skilled and managerial positions were difficult to obtain in the nation’s manufacturing sector. As of 1954, the automobile industry could claim only forty-three African Americans in managerial jobs. Whereas some companies were willing to hire blacks, others excluded them and specified their preference for whites in job listings with employment services. For example, in June 1948, 65 percent of the job orders placed with the Michigan State Employment Service included racial preferences. The same year, an investigation of employment practices in Michigan found that “discrimination in hiring is on the increase…. Despite a serious labor shortage in Detroit, employers refused to employ qualified non-white workers.”66

The job situation was not totally static. In 1948 Atlanta hired its first black policemen, although they were assigned to only African American neighborhoods and could not arrest whites.67 By 1950, four department stores in Saint Paul, Minnesota, had broken precedent and employed eight black saleswomen. “It is becoming possible,” the director of the local Urban League noted optimistically, “to match Negroes to jobs best suited for them.” By 1952, an African American was on the research staff of the leading newspaper in nearby Minneapolis.68 Because firefighters had to share living quarters while on duty, racial integration of fire departments proceeded slowly. But in 1955 San Francisco hired its first black firefighter.69 With racial barriers largely intact, however, black hirings were often token and provided few opportunities for the mass of African American job seekers.

The postwar decade also witnessed some desegregation of public facilities. In 1949 Saint Louis opened its public swimming pools to African Americans. At Fairgrounds Park, however, a gang of young whites attacked black swimmers as a crowd of an estimated two thousand whites heckled African Americans who sought to use the pool. After a two-year court battle, in 1954 Kansas City, Missouri, opened the formerly white-only Swope Park swimming pool to African Americans. Mitigating this integration victory was the reluctance of whites to patronize the desegregated pool, with attendance falling to one-third its normal level during the first summer of integration.70 In Washington, D.C., blacks were gradually admitted to white facilities. In 1949 the Roman Catholic Church instructed Washington’s parochial schools to desegregate. Two years later, the lunchroom of the Hecht Company department store opened to blacks. Within a few months, other department stores and drugstores in the downtown shopping area followed suit and admitted African Americans to their lunch counters and restaurants. In the early 1950s, the National Theatre, Washington’s only venue for Broadway productions, opened its doors to black patrons. Then in 1952 the District Medical Association agreed to admit African American members, and gradually private hospitals granted staff privileges to a few black physicians.71

In 1954 the United States Supreme Court, in Brown v. Board of Education, held that the segregation of blacks and whites in the public schools was unconstitutional. Since dual school systems were the norm in border and southern states, the Brown ruling seemed to promise dramatic change in cities below the Mason-Dixon Line. Yet in the mid-1950s, only communities in the border states took steps to dismantle their systems of separate black and white schools. In the cities of the Deep South, such as Atlanta, construction of separate schools for blacks and whites continued, and not until the early 1960s did the Georgia metropolis make even a token effort to desegregate its schools.72 Just as Shelley v. Kraemer did not destroy the racial barriers in housing, Brown v. Board of Education did not suddenly end racial separation in schooling.

In the black–white cities of the mid-1950s, racial customs thus prevailed over judicial doctrine; life did not conform to the law. The color line held, and the lives of blacks and whites too often did not intersect amicably. They shared a city with a still dominant single hub, but they did not share the neighborhoods or necessarily the facilities within that city. The Supreme Court made high-minded pronouncements, but the way of life in the black–white city responded slowly to demands for change.

The Suburban Migration

While racial boundaries were holding and central-city boosters were attempting to preserve the magnetic pull of the urban core, a vast outward migration was under way along the metropolitan fringe. In sprawling cities such as Los Angeles, where the expansive San Fernando Valley remained largely undeveloped at the close of World War II, many of the migrants were moving into new houses within the central-city limits. But in other cities, especially in the Northeast and Midwest, where there was little vacant land in the core municipality, the migrants were pouring beyond the municipal limits and adding to the metropolitan population outside the reach of big-city mayors and council members. In 1940 only 32 percent of Americans in metropolitan districts lived outside the central city; by 1950, this was up to 41.5 percent, and ten years later the figure was 48.5 percent. In the single decade of the 1950s, this suburban population soared 56.3 percent as compared with a central-city increase of only 17.4 percent.

Virtually everyone during the postwar decade seemed to want a house in suburbia, a fact not ignored by Hollywood. In the 1946 Academy Award–winning film The Best Years of Our Lives, a returning GI reveals that his dream while overseas was “to have my own home. Just a nice little house with my wife and me out in the country, in the suburbs anyway.”73 In the 1947 Christmas classic Miracle on 34th Street, the little girl in the story wants Santa to bring her a home in the suburbs with a backyard swing. The following year, Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House told of an advertising executive who seeks to fulfill his dream of a new home outside the city. The ex-GI, the young child, and the Madison Avenue executive all yearn for a suburban house, a place with grass, trees, breathing space, a swing, and the natural advantages unavailable in the city.

Housing construction figures reflected this yearning as millions of Americans moved into new single-family dwellings (figure 2.6). In 1947 the number of new housing starts rose above 1.2 million, double the figure for 1940, and remained above that mark throughout the rest of the 1940s and 1950s. It peaked at 1,952,000 in 1950, more than double the prewar record set in 1925. With low-interest, long-term mortgages insured by the FHA and Veterans Administration, millions of World War II veterans could now escape the central city and afford a house in suburbia. In 1945 a Saturday Evening Post survey found that only 14 percent of the respondents wanted a “used” house or an apartment.74 An overwhelming majority of Americans dreamed of a new house, and at a rapid pace builders were realizing that dream for many eager buyers.

FIGURE 2.6 Housing tract under construction to meet the postwar housing shortage in southern California. (Herald Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library)

This housing boom and the burst of new suburban customers were perhaps the greatest phenomenon of the postwar decade. In 1953 Fortune breathlessly informed its readers in the business community of “the lush new suburban market” that was “made to order for the comprehending marketer.”75 A year later, the sales manager for Sears Roebuck seconded Fortune’s enthusiasm when he told an advertising convention: “This movement to the suburbs means more automobiles, more mileage per car and more multiple-car families…. I will leave it to your imagination to think what it means in terms of automotive home workshops, sporting goods, lawnmowers, garden tools, casual clothing.” He concluded: “Man, oh man, think what this means in the sale of goods!”76 In 1955 U.S. News & World Report summed up the suburban boom of recent years when it wrote of “the rush to the suburbs.” “No matter where you look, you find suburbs mushrooming,” reported the magazine.77 The order of the age was suburban growth that, in turn, spawned new markets and exciting opportunities for profit.

Although many Americans viewed the suburban migration of the decade following World War II as an unprecedented phenomenon transforming the nation, in fact it was a continuation of the fast-paced suburbanization of the 1920s, which had been interrupted by the economic depression of the 1930s and World War II. During the 1920s, a suburban rush had also fueled a building boom, and millions of suburban-bound Americans had purchased new automobiles and radios from happy retailers. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, as in the 1920s, the most significant construction projects along the metropolitan fringe were housing subdivisions. Suburbia in 1950, as in 1930, was primarily a residential refuge. In other words, the suburban boom of the postwar decade was as much a continuation of the past as a departure. The rush to the suburbs was accelerating, with more new homes produced and more lawnmowers sold than ever before. But the outward migration to new homes did not mark a sudden rejection of the concept of the single-focused metropolis or a desire to shed the pattern of metropolitan existence prevailing before 1945. The suburban migration was not a revolution; it instead accelerated the existing pattern of evolution.

The greatest symbol of this quickening migration was Levittown, the massive 17,447-house community erected by Levitt and Sons on Long Island between 1947 and 1951. William Levitt, the mastermind of the project, was proclaimed the Henry Ford of housing because of his skill at mass-producing dwelling units. Describing how “each crew did its special job, then hurried on to the next site,” Time reported that “new houses rose faster than Jack ever built them; a new one was finished every 15 minutes.”78 This fast-paced routine produced a four-room house on a sixty- by hundred-foot lot. During the first two years of construction, the houses were look-alike Cape Cod–style cottages, but in 1949 Levitt introduced his ranch-style model. Both the Cape Cod and ranch-style houses consisted of a living room, a kitchen (with a Bendix automatic washing machine), two bedrooms, and a bath downstairs and an unfinished second-floor attic that could later be converted into two additional bedrooms (figure 2.7). The houses sold for $6,990 at first; later Levitt and Sons raised the price to $7,990. But even at the latter price veterans could buy a home with no down payment and carrying charges of only $58 a month.79 “No longer must young married couples plan to start living in an apartment, saving for the distant day when they can buy a house,” Time told its readers. “Now they can do it more easily than they can buy a $2,000 car on the installment plan.”80

FIGURE 2.7 Owners have remodeled the attics of their homes in Levittown, New York, adding needed bedrooms, 1950s. (Library of Congress)

Thousands of New Yorkers recognized this fact and flocked to the Levitt and Sons sales office. A postwar housing shortage had forced many young families to move in with their parents or in-laws or crowd into cramped, run-down apartments. For these poorly housed Americans, Levitt’s suburbia represented a release from urban misery. In 1949 Levitt and Sons informed prospective purchasers that the first 350 in line on Monday, 7 March, would be able to buy one of the latest batch of Levittown houses. At 11:00 Friday night, the first applicant for a house showed up to form a line that had grown to almost fifty home-hungry buyers by Saturday morning; by Sunday morning, nearly three hundred were camping out in sleeping bags and on lawn chairs awaiting the Monday sale. The New York Times reported that one waiting veteran heard the news that his wife had just given birth to twins at a local hospital. “Unperturbed, he received the congratulations of his companions and kept right on standing in line.”81 On 15 August 1949 Levitt and Sons sold 650 houses in only five hours, the seemingly insatiable yearning for suburbia enriching the Levitts at the rate of $1,000 per house.82

Spurred by the success of his Long Island development, William Levitt launched two additional giant housing projects during the following decade. In 1951 he opened the sales office for Levittown, Pennsylvania, twenty-two miles northeast of Philadelphia, and over the next five years built 17,311 houses for 67,000 residents. In what one observer called a “struggle against monotony,” at the Pennsylvania project the same floor plan was “enclosed by four different types of exteriors, painted in seven varieties of color so that your shape of Levittown house occurs in the same color only once every twenty-eight times.”83 Then in 1955 Levitt announced his purchase of almost all the land in Willingboro Township, New Jersey, where he would build a third Levittown. Although the lots and houses were slightly larger, the new Levittowns offered much the same product as their older Long Island counterpart. In each of the Levittowns young families would be able to buy affordable homes along the metropolitan fringe and become suburbanites.

The new communities were religiously diverse, welcoming Catholics, Protestants, and Jews whose ancestors had come from all corners of Europe. Moreover, both white- and blue-collar families moved into the developments, creating an occupational mix. Yet in some ways the residents of the Levittowns were very similar to one another. They were overwhelmingly young, married couples with small children or the prospect of offspring in the near future. In 1951, 46 percent of the population of Levittown, New York, were between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-six, and 41 percent were under ten years old.84 A remarkable 30 percent were under the age of five. Pregnancy was so common that it was called “the Levittown Look.”85 According to Time, “In front of almost every house along Levittown’s 100 miles of winding streets sits a tricycle or a baby carriage. In Levittown, all activity stops from 12 to 2 in the afternoon; that is nap time.” There were virtually no teenagers or senior citizens. “Everyone is so young that sometimes it’s hard to remember how to get along with older people,” observed one Levittowner.86 In addition, 95 percent of the adults were married; single, divorced, or widowed individuals were rare. Fifty-four percent of employed Long Island Levittowners worked in New York City, the majority of these earning their living in Manhattan. And 53 percent of the Levittowners of 1951 had moved from New York City to the suburban development, with only 18 percent coming from suburban Nassau County, the site of Levittown, and 17 percent coming from out of state.87 Levitt’s Long Island development was, then, a community of suburban pioneers, newcomers from the big city who were beginning their families on the metropolitan frontier. The husband most often still commuted to work in the city, and the wife stayed at home with small children or awaited the imminent prospect of birth.

Although some of the migrants to Levittown found it difficult to adjust to the new community and its little, look-alike houses, the prevailing sentiment was favorable. One veteran who had shared a one-room apartment with his wife and a relative before moving to Levittown commented: “That was so awful I’d rather not talk about it. Getting into this house was like being emancipated.”88 The wife of another former GI wrote to a local newspaper: “Too bad there aren’t more men like Levitt & Sons…. I hope they make a whopper of a profit.”89 With considerable hyperbole but some truth, Levitt himself observed: “In Levittown 99% of the people pray for us.”90 For some residents, the Levittown cottages were the first step on the path to upward mobility and were readily superseded by more expensive homes as soon as their bank accounts permitted. But a large number expressed their fondness for the community and faith in its future by remaining there and investing in their mass-produced houses. A 1956 survey found that of the 1,800 families who had migrated to Levittown in 1947, 500 still resided there.91 Alterations and home improvements were major industries in the community, and in 1957 a commentator reported that “it is hard in Levittown today to find a house with an unaltered exterior—and rare to find two in a row with the same alterations.” Moreover, the value of Levittown houses, “increased by a demand that cannot be met,” had “been raised by these improvements,” so that by 1957 altered houses were selling for as much as $21,000.92 Demonstrating the satisfaction of most homeowners, a 1957 survey found that 94 percent of Levittowners would recommend the Long Island community to their friends.93

Levittown, however, was not a harmonious utopia without conflict and problems. Given the large number of children in the community, the schools were predictably the chief focus of controversy. Between 1947 and 1957, the enrollment in School District Five, the largest of the four districts in Levittown, soared from 47 pupils attending a three-room schoolhouse to 16,300 students in fourteen buildings costing almost $23 million.94 In 1953 one commentator reported that “three years ago in Levittown the schools had 3,000 children—and they were being taught in Quonset huts…. This year they have roughly 9,000 children—and are managing to absorb them only by holding split sessions.” He concluded: “No school system can indefinitely survive the impact of these gigantic waves of children.”95 To finance this expansion, the property tax rate rose from 73 cents per $100 of assessed valuation for the school year 1947/1948 to $6.06 per $100 for 1957/1958, the second highest rate of the sixty-two districts in Nassau County. “Many residents who left New York City because of high taxes, and because they wished to live and raise their families in a suburban atmosphere,” observed one Long Island publication in 1955, “are beginning to wonder if they have merely leapt from the frying pan into the fire.”96

Not only were the high taxes unexpected, but Levittowners had to adapt to a new sense of authority over their schools. In the giant, heavily bureaucratized, and highly centralized school system of New York City, where the board of education was not elected but appointed by the mayor, professional administrators ruled the educational process, and parents had little voice or clout. But in Levittown, mothers and fathers enthusiastically filled the ranks of the Parent-Teacher Associations and attended school board meetings, especially the annual budget meetings. In 1954 and 1955, a civil war erupted when the schools included in their classroom exercises the playing of a recording of “The Lonesome Train,” a cantata that described the return of Lincoln’s body to Illinois for burial. Claiming that it was written by “known Communists,” one group of parents wanted the cantata banned, whereas another faction defended it.97 A PTA president who opposed the ban remembered that she “organized meetings and marches. The meetings were held on Friday nights and went on till early the next morning.”98 In May 1957, the fire department broke up a controversial school board meeting, claiming that the disorderly gathering was a fire hazard. When the meeting reconvened three days later at 7:30 in the evening, three thousand Levittowners crowded into the building, and not until 6:15 the next morning did the gathering adjourn after approval of a new school budget.99 Underlying the school clashes were religious divisions. Jewish Levittowners generally supported a liberal curriculum and hefty spending; Catholic parents more often opposed what they perceived as radical influences and extravagant budgets.100

One group that the Levittowners of the late 1940s and early 1950s did not have to cope with was blacks. William Levitt restricted sale of houses to Caucasians, claiming that the prospect of racially integrated neighborhoods would deter buyers. “We can solve a housing problem, or we can try to solve a racial problem,” Levitt contended. “But we cannot combine the two.”101 In 1949 a black veteran, James Mayweathers, waited in line from 7:00 A.M. Saturday to 7:30 A.M. Sunday to apply for the purchase of a Levitt house. On Sunday morning, Levitt informed him that blacks were not permitted to buy the new dwellings. The NAACP, the local of the United Automobile Workers Union, and the American Jewish Congress were among the groups to protest Levitt’s discriminatory policy, but the developer remained dedicated to a whites-only policy.102

In 1957 the race issue exploded in Levittown, Pennsylvania, when the African American Myers family moved into a house at the corner of Deep green and Daffodil lanes. On the night of 13 August, two hundred people gathered outside the house; a barrage of stones ensued, smashing the living-room picture window. Later that week, the county sheriff declared the situation out of control as crowds formed before the house each night, and he asked for help from a state police detachment. The following week, state troopers wielding riot clubs broke up a group of four hundred people who had gathered to protest the sale of the house to the Myers family, and the Levittown Betterment Committee formed with the purpose of preserving the racial purity of the community. In September, the protests continued as automobiles filled with demonstrators drove by the Myers home late at night blowing their horns and playing the car radios as loudly as possible. Foes of integration gathered in an adjacent house flying the Confederate flag, sang “Old Black Joe,” and played recordings of “Old Man River.”103

Although most suburban subdivisions were off-limits to black purchasers, a few developers catered to African Americans. Thomas Romana’s Ronek Park on Long Island offered one thousand small Levitt-type homes to buyers “regardless of race, creed or color,” a cue to any alert home seeker that the development was in fact intended for blacks.104 Suburbia, then, was not to deviate from the color line that prevailed in the central city. On the metropolitan fringe, as in the core city, there were to be white neighborhoods and black neighborhoods, but integrated living was rare.

The Levittowns attracted unequaled media and scholarly attention during the postwar years, but they were not the only mammoth housing developments arising along the metropolitan fringe. South of Chicago, American Community Builders (ACB), headed by former Federal Public Housing Authority commissioner Philip Klutznick, built Park Forest, a town of 31,000 residents. Like Levittown, it catered to the young families of veterans, although ACB first built rental garden apartments and then added thousands of single-family houses priced from $12,500 to $14,000. Klutznick was more idealistic than the pragmatic Levitt and sought not only to make money, but to fashion a model community. “We aren’t interested in houses alone,” Klutznick claimed. “We are trying to create a better life for people. In our view, we will have failed if all we do is produce houses.”105 With this in mind, he encouraged the first residents to incorporate Park Forest as a municipality so that they could participate democratically in the development of the community and not remain subject to the paternalistic rule of the developer. Klutznick dreamed of “a people’s village, not a developer’s fiefdom.” This did not necessarily benefit him. “As the resident president of ACB,” he later noted, “I was the natural object of protest movements.”106

Not only were the Park Forest houses more expensive than those in Levittown, but the residents had a higher educational status and tended to be upwardly mobile white-collar workers. A 1950 survey found that the average adult male in Park Forest had more than four years of college education, and one observer reported that “the first wave of colonists was heavy with academic and professional people—the place, it appeared, had an extraordinary affinity for Ph.D.s”107 But like Levittown, it also had an extraordinary affinity for children. In 1950 half the residents were under fourteen years old, and the high birth rate earned Park Forest the nickname “Fertile Acres.”108 One early resident reminisced about the swarms of children he encountered on his first night in the community: “It seemed that they were all outside that night—60 noisy, running, screaming children swirling around us—it was incredible.”109

The West Coast counterpart to Park Forest and the Levittowns was Lakewood, located south of Los Angeles. In 1950 three partners bought 3,375 acres of southern California farmland and launched the giant housing development. By February 1952, an Associated Press story reported that “almost 8,000 homes have been completed by assembly-line methods,” and “beans and sugarbeets have been replaced by broad boulevards and quiet side streets, green lawns and frame homes.” The developer offered seven basic floor plans, and the two- and three-bedroom houses sold for from $9,195 to $12,000. A veteran could acquire a two-bedroom model for a down payment of only $195. As an added attraction, each house came with an electric garbage-disposal unit, and the community boasted of being a “garbage-free city.”110 In 1954 Lakewood incorporated as a municipality, adopting the motto “Lakewood—Tomorrow’s City Today.”111 Three years later, it had an estimated 85,000 residents, most of them young couples with an abundance of children. Lakewood, like Park Forest and the Levittowns, definitely appeared to be tomorrow’s city, a community of the young who were investing in the latest ranch-style houses and garbage disposals.

Because of their size, their rapid growth, and their large numbers of young people, seemingly representing the nation’s future, the Levittowns, Park Forest, and Lakewood became well-known examples of the suburban trend; both in the 1950s and in later decades, they were viewed as stereotypical postwar suburbs. Yet not all suburban migrants of the late 1940s and early 1950s were Levittowners seeking moderately priced, four-room, mass-produced houses. In fact, smaller developments in every price range were springing up along the metropolitan fringe throughout the nation. At the same time Levitt was selling his diminutive ranch models for $7,990, for $15,950 Pine Ridge Homes was offering its three-bedroom (“one paneled in knotty pine”) and two-bath ranch houses in Long Island’s “fine residential village of Flower Hill … only 19 miles from midtown New York.”112 On Long Island’s south shore, Sam Harris was marketing the “Merrick Ranger,” a three-bedroom, two-bath ranch house costing $16,990 and located in his “magnificent Merrick Oaks development,” with its “thousands of towering, stately oak, beech and pine trees … framed by winding roads, paved sidewalks and curbs.”113 In an eight-hour period in 1949, developer Sam Berger sold 155 houses of the $13,500 to $16,000 price range in Great Neck, Long Island.114 In 1947 the New York Times reported “a noticeable tendency in recent weeks toward the erection of residences definitely in the ‘luxury’ class.” For example, two developers were subdividing a north shore Long Island estate into lots of an acre or more for sixty-six homes starting at $30,000, and in Englewood, New Jersey, the developer of South Hills Estates claimed to be responding to “an acute demand for $40,000 to $50,000 homes.”115

Exclusive Scarsdale did not escape the wave of suburban newcomers, its population increasing over 36 percent in the 1950s. Yet Scarsdale was not Levittown and did not intend to be. In the fall of 1949, residents of the exclusive suburb became aware that a developer was preparing to build a subdivision of forty-six ranch houses with the same basic plan in their community. The village building inspectors temporarily halted the project by revoking the building permits, but many Scarsdale residents sought a permanent end to the threat from what one local leader called “the hit-and-run builders of look-alike houses.” Consequently, in April 1950 the village board adopted an ordinance “to regulate similarity of appearance in any neighborhood.” By forbidding repetition in the length and height of roofs, the placements of windows, doors, and porches, and the widths of houses in a single neighborhood, the board outlawed the look-alike models associated with large-scale builders such as Levitt.116 By law, Scars-dale was in effect restricted to expensive, custom-built homes.