| 6 |  |

Beyond the Black–White City |

“Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal,” concluded the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders following the riots of 1967.1 This statement summed up the prevailing vision of ethnicity in the United States during the first three decades after World War II. America was a black–white nation, a bifurcated entity divided between African Americans who, according to the commission, seemed destined to take over the central cities and whites who would create their alternative society in the suburbs. The cultural conception of race was two-toned, with a minority at one end of the color spectrum and a majority at the other. To bring together these extremes seemed imperative to the welfare of the American city. Solving the black–white racial dilemma was the great goal of American urban policy.

Other ethnic groups existed, although their presence was obscured by the prevailing black–white conceptualization of American society. In the late 1940s and the 1950s, Puerto Ricans flooded into New York City, adding a new Latin element to the metropolis. The millions of Americans who saw West Side Story on the stage or screen were aware of the Anglo–Puerto Rican clash in New York, yet in the 1960s this was a sideshow commanding far less attention than the center-stage black–white dilemma. Large numbers of Mexican Americans had long inhabited areas of the Southwest, and in a city such as San Antonio the most notable ethnic division was between Anglo and Hispanic. Moreover, there were well-known Chinatowns in San Francisco and New York City, testifying to the presence of an Asian minority. Exceptions to the prevailing black–white conception of American society, Asians, Mexicans, and Puerto Ricans were not deemed of sufficient significance to warrant a national advisory commission or extended hand-wringing over their impact on the future of the nation. For policy makers, scholars, journalists, and the American public in general, the race problem meant the antagonism between whites and blacks. Other groups were outside the dominant conceptual framework.

During the last three decades of the twentieth century, however, the ethnic composition of the nation changed markedly, giving rise to a new vision of ethnicity in metropolitan America. A massive influx of immigrants from Latin America and Asia compelled Americans to accept a more complex picture of the metropolitan population. These newcomers did not fit the old formula of a monolithic white majority versus a monolithic black minority. The two-toned society was yielding to a nation of various shades with large contingents of immigrants who did not necessarily identify with either of the two traditional players in the racial game. Some native-born Americans had trouble adjusting to the change. Whites had to recognize that the complexion of metropolitan America was growing darker. Perhaps more problematic was the struggle of blacks to accept that the complexion of the city from their standpoint was growing lighter. As Americans refashioned their cultural vision of urban ethnicity, there were new ethnic conflicts. The long-standing bifurcated concept of majority versus minority died hard, but by 2000 perceptive observers had to admit that the old black–white world of the early postwar years had passed. At the close of the century, many central cities were not growing more black, and many suburbs were not white preserves. Newcomers had created an ethnic pattern that defied the prognostications of earlier prophets.

The Newcomers

Underlying the ethnic changes in metropolitan America was a shift in immigration patterns. Owing to restrictive immigration laws, the economic depression of the 1930s, and World War II, the number of migrants to America during the period 1920 to 1960 was far below that of earlier decades. Whereas 14.7 percent of Americans were foreign-born in 1910, in 1970 the foreign-born share reached a new low of only 4.7 percent. Moreover, before the 1960s the overwhelming majority of newcomers were from Europe, federal legislation having severely limited the entry of Asians. For the 150 years from 1820 through 1969, 79.9 percent of the nation’s immigrants were from Europe, only 2.7 percent from Asia, and 7.5 percent from Latin America and the West Indies.2 During the first two decades of the postwar era, then, the number of newcomers was modest, and the share of native-born Americans was growing. In addition, the word “immigrant” conjured up images of white Europeans arriving from Poland, Germany, Ireland, or Italy. The tired, poor, huddled masses welcomed by the Statue of Liberty had come from that relatively small slice of the world between the Urals and the North Atlantic.

During the last three decades of the twentieth century, all this changed. The immigration rate soared, reaching a peak in 1990/1991. By 2000, 10.4 percent of the nation’s population was foreign-born. Moreover, most of these newcomers bore little resemblance to those who had arrived at Ellis Island in the early twentieth century. Only 12.3 percent of the more than 16 million immigrants arriving from 1981 through 2000 were from Europe; 34.7 percent were Asians; 48.9 percent were from the Americas.3

A number of factors facilitated this flow of newcomers and influenced its composition. Most notably the passage of the Hart-Celler Act in 1965 eliminated the old system of quotas, whereby the federal government had preferred northern European immigrants over newcomers from southern and eastern Europe and permitted only a small number of new residents from Asia. Rather than allocating quotas on the basis of nationality, the Hart-Celler Act established family relationship and occupational skills as the principal criteria for admission to the United States. Henceforth, the federal government would give preference to those seeking to come to the United States to reunite with family members and to those with scarce or desirable skills that could enhance the American economy or quality of life. In other words, educated professional and technical workers were preferred over the unskilled, who might well struggle to find employment and depress American wage levels. Further enhancing the flow of immigrants was America’s willingness to waive immigration restrictions for refugees from Communist regimes. As the world’s leading foe of Communism, the United States felt compelled to open its doors to victims of left-wing governments, no matter their ethnicity. An additional factor facilitating the wave of immigration was the nation’s porous borders, through which millions of illegal newcomers could pass. By 2000, there were an estimated 7 million unauthorized immigrants in the United States, almost 5 million of them having come from Mexico.4 The federal government was unable to prevent the illegal passage of Mexicans across the nation’s southern borders, and the consequence was a surge in the foreign-born population of the Southwest.

These factors resulted in an immigrant population that was highly diverse in social and educational background. Many well-educated Asians gained entry under the provisions of the Hart-Celler Act. Unlike the stereotypical immigrants of the past, they were middle class and college trained. Moreover, America’s refugee policy opened the floodgates to displaced capitalists whose entrepreneurial skills and ambitions clashed with Communist dogma. Vehement anti-Communists, these newcomers posed no threat to the nation’s prevailing ideology but instead reinforced the image of the United States as the world’s chief bulwark of capitalism. The illegal immigrants were for the most part desperately poor, compelled by economic necessity to defy the law. Because of their precarious legal status, they could be readily exploited by American employers, paid less than minimum wage, and forced to work in conditions that no native-born American would tolerate. The new immigrants thus comprised college-educated professionals as well as the poor and unschooled, the ambitious capitalist entrepreneur as well as the exploited proletariat.

On arriving in America, these varied immigrants did not disperse evenly across the nation. Instead, a few areas attracted the bulk of newcomers. Unlike those of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the immigrants of the late twentieth century were found disproportionately in the Sun Belt and were less common in the old manufacturing heartland. In 2000 the Miami–Fort Lauderdale metropolitan area was the most “foreign” region in the country; 40.2 percent of its population had been born outside the United States. The figure for Los Angeles–Riverside–Orange County was 30.9 percent, and for San Francisco–Oakland–San Jose, it was 27 percent. In contrast, the foreign-born constituted only 2.6 percent of the population in both the Pittsburgh and Cincinnati metropolitan areas. Of the older hubs of the Northeast and Midwest, only the New York City area, with 24.4 percent of its population born outside the United States, was among the principal destinations for the new immigrant population.5

Miami’s preeminence as a magnet for newcomers was owing primarily to the massive influx of Cubans, who were in the vanguard of the new immigration. From the coming of power of Fidel Castro in 1959 through 1962, 215,000 Cubans fled their homeland and arrived in the United States. Known as the Golden Exiles, these initial migrants included a disproportionate share of Cuba’s professional and managerial class and were on average far better educated than the Cuban population as a whole. Despite periodic crackdowns on migration by the Cuban government, an additional 578,500 arrived from 1963 through 1980.6 Not all settled in South Florida. A notable Cuban settlement developed along the west bank of the Hudson River in West New York and Union City, New Jersey. But Miami became the capital of Cuba in exile and the most Cuban city in the United States. By 1990, the population of the city of Miami was 62.5 percent Hispanic, including many Nicaraguan refugees from the left-wing Sandinista regime. Yet the largest contingent of Miami’s Hispanics was the Cubans, who constituted 38.9 percent of the city’s population.

Visitors to Miami were struck by its Latin, and specifically Cuban, flavor. In 1980 an article in the New York Times Magazine reported on “the Latinization of Miami,” informing readers that “more than half a million Cuban refugees have transformed a declining resort town into a bustling bicultural city.”7 In 1985 Time magazine described Miami’s Calle Ocho district: “Open-air markets sell plantains, mangoes and boniatos (sweet potatoes); old men play excitedly at dominoes in the main park. Little but Spanish is heard on the streets and indeed in many offices and shops. A Hispanic in need of a haircut, a pair of eyeglasses or legal advice can visit a Spanish-speaking barber, optometrist or lawyer.”8 The writer Joan Didion claimed that “the entire tone of the city, the way people looked and talked and met one another, was Cuban…. There was even in the way women dressed in Miami a definable Havana look, a more distinct emphasis on the hips and décolletage, more black, more veiling, a generalized flirtatiousness of style not then current in American cities.”9 The widespread use of Spanish testified to the strong and persistent Cuban influence. In 1980 a survey of Cuban households in Miami found that 92 percent of the respondents spoke only Spanish at home, and 57 percent of Cubans relied primarily on Spanish at work. Moreover, 64 percent listened to Spanish-language radio, and less than 20 percent read English-language newspapers.10 In 2000, forty years after Castro’s triumph, 51.5 percent of the 3.6 million people five years old and over in the Miami–Fort Lauderdale metropolitan area spoke a language other than English at home, the overwhelming majority of these communicating in Spanish.11

As the Cuban population soared, the zone of Cuban settlement spread outward through much of Miami-Dade County. The center of Cuban Miami was Little Havana, an aging, inner-city area around Calle Ocho. But there was no Cuban ghetto. Instead, the newcomers moved west from Little Havana into the suburbs of West Miami and Sweetwater as well as northwest into Hialeah. By 1980, fifteen of the twenty-seven municipalities in Dade County were at least 15 percent Hispanic, and Latins constituted 81 percent of the population of Sweetwater, 74 percent of the inhabitants of Hialeah, and 62 percent of the residents of West Miami. The exclusive suburb of Coral Gables was not off-limits to the newcomers; 30 percent of its residents were Hispanic.12

The Cuban presence in Coral Gables and other upper-middle-class areas was visible proof of the relative economic success of the immigrants. Miami’s Cubans were not an economically oppressed ethnic minority trapped on the lower rungs of the social ladder and barred from opportunities for success. Instead, they earned a reputation as ambitious entrepreneurs who buoyed rather than depressed the local economy. By the early 1980s, Dade County could claim more than 18,000 Cuban-owned businesses, including more than 60 car dealerships, around 500 supermarkets, and approximately 250 drugstores. In addition, there were sixteen Cuban American bank presidents.13 In 1990, 42 percent of all businesses in Dade County were owned by Hispanics, three-quarters of them controlled by Cubans.14 Attracted by Miami’s bicultural, bilingual environment, banks and corporations seeking to do business with Latin America established branches in the South Florida city, leading the president of Ecuador to dub Miami “the capital of Latin America.” Miami became the vital business link between Latin America and the United States, and commentators attributed this to the Cuban newcomers. In 1980 one observer noted: “It is an article of faith in Miami that without the impetus provided by the Cuban-exile community the city today would be just another Sun Belt spa well past its prime.” The same year, the city’s mayor, who was of Puerto Rican origin, confirmed this view: “Miami would not be what it is, or where it is, if it were not for the Cuban community.” Although, he claimed, “most Hispanic communities” were “not very demanding and … happy with very little,” the Cubans were “extremely competitive, … extremely aggressive. Not only do they want the best, they want it first.”15 Moreover, Cuban leaders were not modest about their contribution to the city’s economy. “We Cuban people have made Miami,” boasted one of Miami’s Cuban executives. “Thanks to the freedoms here in America, we’re combining our natural Cuban energies with American knowledge, American know-how, to create a new more passionate American.”16

Cubans were not only establishing themselves in the private sector but also taking charge of local government. As early as 1973, a Cuban was elected to Miami’s governing commission. Twelve years later, a Cuban was chosen mayor of Miami, and another was appointed city manager. By the late 1980s, the cities of West Miami, Sweetwater, Hialeah, and Hialeah Gardens also had Cuban-born mayors. And in the 1990s, a Cuban assumed the office of county executive. In 2000 a Miami Herald poll found that at least 80 percent of Miami’s non-Hispanic whites and blacks as well as 63 percent of the Cubans believed that Cubans controlled the area’s politics.17 “Nowhere else in the country, and possibly in American history, have first-generation immigrants so quickly and thoroughly appropriated political power,” concluded a scholarly analysis of Miami’s political scene.18

Although dominant in South Florida, Cubans were far outnumbered nationally by the largest contingent of Hispanic immigrants: the Mexicans. According to the Immigration and Naturalization Service, they constituted 24 percent of the newcomers arriving from 1981 through 2000, and the 2000 census reported that the almost 8 million persons of Mexican birth resident in the United States accounted for 28 percent of the nation’s foreign-born population.19 Nowhere were Mexican Americans more numerous than in the Los Angeles area. In the mid-1990s, one scholar proclaimed that “Los Angeles has become the capital of Mexican America and the single largest Mexican concentration outside of Mexico City.”20 By 2000, more than 3 million people of Mexican birth or ancestry lived in Los Angeles County, constituting 32 percent of the county’s population. They accounted for 15 percent of all Mexican Americans in the United States. Moreover, there was no sign that the latinization of Los Angeles was abating. Between 1990 and 2000, the Mexican population of the Los Angeles area rose 44 percent, as compared with a 13 percent rise in the overall number of inhabitants.21

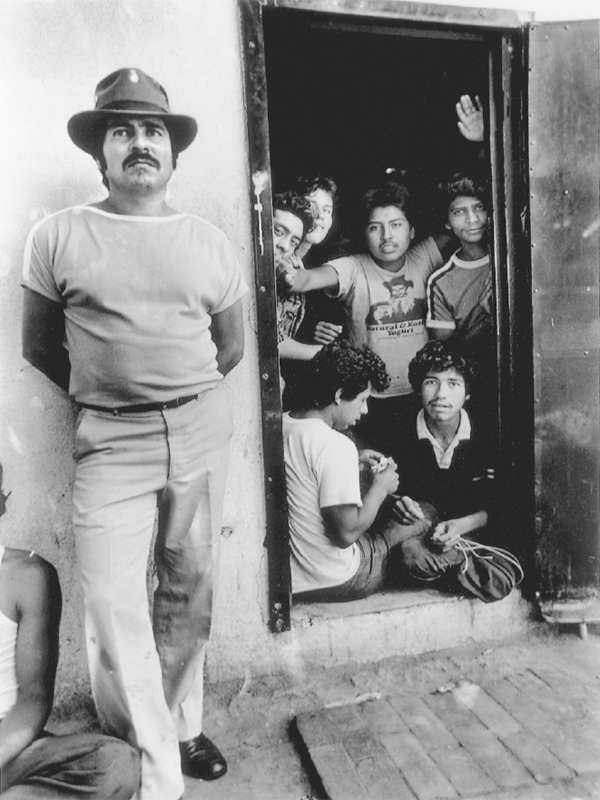

The long-standing heart of Mexican American settlement was East Los Angeles. Most of the newcomers to this area were poor, coming to the United States to better their economic condition. And many were illegal immigrants. Consequently, the old East Los Angeles barrio spreading eastward from Boyle Heights reflected the poverty of Mexico rather than the affluence that moviegoers associated with southern California. According to one observer from early 1990s, “In the bars and restaurants of Boyle Heights, bedraggled youngsters go from table to table pleading with people to buy novelties like those found in the stalls of Tijuana. Outside on the sidewalks, their mothers, often with infants in their arms, stop passers-by and beg for money.” The lack of affordable housing forced many of the newcomers to live in illegally converted garages, and the Los Angeles Times reported on 200,000 “garage people” who lived with little or no heat, plumbing, or windows (figure 6.1).22

FIGURE 6.1 Some of the fifty undocumented immigrants found in a garage in Compton, California, 1984. (Philip Kamrass, Herald Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library)

Yet the rapidly rising Mexican population was not confined to East Los Angeles. Instead, it spread through much of the region, moving into housing once occupied by other ethnic groups. For example, South Central Los Angeles, the traditional hub of black life in southern California, experienced a Latin invasion. By 1990, only 53 percent of South Central’s population was non-Hispanic black; 44 percent was Latino. The Watts neighborhood, which had lent its name to the riot of 1965, was 43 percent Hispanic.23 Meanwhile, middle-class Mexican Americans moved eastward, settling throughout the San Gabriel Valley and finding homes in the distant reaches of San Bernardino and Riverside counties. The suburbs were not off-limits to the growing Mexican American population. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, one scholarly study said of this outward flow: “In the entire history of American suburbanization … there is no comparable instance of an ethnic or linguistic group moving to the suburbs in such overwhelming numbers and density.”24

Mexicans were also the leading immigrant group in the Chicago area. Although the Hispanic presence was not nearly as pronounced as in southern California, the Land of Lincoln was acquiring a Latin flavor. By 2000, there were almost 800,000 Mexican Americans among the 5.4 million people in Chicago’s Cook County. During the last decades of the twentieth century, the Lower West Side, stretching westward from the once Czech district of Pilsen, emerged as the center of the local Mexican community. Twenty-Sixth Street, the area’s chief shopping strip, was dubbed “Avenida Mexico,” and, according to one estimate, by the mid-1980s more than three-quarters of the businesses along the thoroughfare were owned by Mexican Americans. The annual Fiesta del Sol, held in August, and the Mexican Independence Day Parade in September as well as the opening of the Benito Juarez High School in 1977 were signs of the new Mexican American preeminence. The once Lithuanian Providence of God Roman Catholic Church became a Spanish-speaking parish. Nearby, the Polish St. Adalbert’s Basilica adapted by adding a picture of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and the German Lutheran St. Matthew’s Church sported the alternative name of Iglesia San Mateo, with Lutheran services in both English and Spanish.25 As in Los Angeles, Mexican Americans were not confined to older inner-city neighborhoods but spread into nearby West Side suburbs. Once a predominantly central and eastern European working-class town, by 2000 Cicero was 68 percent Mexican. Farther out, in the pre–World War II suburban bungalow belt, Mexican Americans constituted 31 percent of Berwyn’s population.

Increasing numbers translated into increasing political power for Mexican Americans. In 1981 Henry Cisneros won election as mayor of San Antonio, the first Mexican American mayor of a major city in the United States. Two years later, the Mexican American Federico Peña won the mayor’s office in Denver. During the 1990s, both Cisneros and Peña served in President Bill Clinton’s cabinet. In the Los Angeles area, the political triumphs were less dramatic, and Mexican Americans failed to acquire a proportionate share of public offices. Handicapping Mexican American office seekers was the relatively low proportion of Mexican immigrants who became citizens. In 2000 only 20 percent of American residents of Mexican birth were citizens and thus enjoyed voting rights. In contrast, 58 percent of American residents of Cuban birth were citizens.26 Yet there were victories. In 1985 a Mexican American won a seat on the Los Angeles city council, and six years later another secured a place on the powerful county board of supervisors. Finally, in 2005, a Latino was chosen mayor of Los Angeles. In California, as in Florida, Hispanics were seizing the reins of power.

Although Mexicans were the largest Hispanic group in the United States, millions of other Latin Americans migrated northward during the last three decades of the twentieth century. The largest Hispanic immigrant group in the New York City area was the Dominicans. Almost 800,000 people born in the small Caribbean nation of the Dominican Republic or of Dominican ancestry lived in the New York City area by 2000, more than double New York’s Mexican population. Washington Heights, at the northern end of Manhattan, became a Dominican enclave, although by the end of the century the Dominicans were succeeding the outward migrating Puerto Ricans in the nearby West Bronx. Between 1990 and 2000, the number of Puerto Ricans in New York City proper dropped 12 percent as this older, more established Hispanic group followed European Americans to the suburbs.27 Yet Dominicans filled the apartments left behind, participating in one more stage of the city’s seemingly endless history of ethnic succession. In 2000 the New York area was home to 247,500 Ecuadorians as well and almost an equal number of Colombians.28 These South Americans were especially numerous in the ethnically diverse borough of Queens, where they shared space with Asians and native-born European Americans.

During the 1980s, civil wars in Central America spurred the migration of Salvadorans, Guatemalans, and Nicaraguans. The Nicaraguans added to Miami’s Hispanic population, the Salvadorans constituted the largest portion of the Latino immigrants in Washington, D.C., but Los Angeles was the destination for the lion’s share of Central Americans. By 2000, the Los Angeles area was home to approximately 800,000 Central Americans, with almost 400,000 Salvadorans alone. In fact, the Los Angeles metropolitan area housed almost 50 percent of all Central Americans in the United States and nearly 60 percent of the Salvadorans. Southern California’s Central Americans were generally poor, with little schooling by United States standards, and a large share had entered the country illegally. They were disproportionately engaged in household services, and the stereotypical Salvadoran or Guatemalan immigrant woman was a servant or hotel maid. Although they were not clustered in any single ethnic ghetto, the largest concentration of Central Americans was in the Pico–Union/Westlake district, immediately to the west of downtown Los Angeles, and farther northwest in Hollywood.29 These areas housed the standard assortment of restaurants, groceries, and other enterprises catering to ethnic needs, all testifying to the burgeoning diversity of life in southern California.

Although Latin America was contributing the largest share of the nation’s new immigrants, the influx of Asians was almost as dramatic. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, there were 8.5 million persons of Asian birth residing in the United States. Like the Hispanics, they were not evenly distributed across the nation but instead heavily concentrated in California and the New York City area. In 2000 the Honolulu metropolitan area led the nation in percentage of population of Asian origin, but most Hawaiian Asians were not recent immigrants but long-standing residents. Of the metropolitan areas ranked second to nineteenth in percentage of Asian population, thirteen were in California, three were in northeastern New Jersey, one was New York City, and the other was the Seattle area. Yet there were lesser concentrations of Asian population in other parts of the country. For example, the traditionally Jewish Chicago suburb of Skokie was 21 percent Asian, stereotypical suburban Glendale Heights to the west in DuPage County was 20 percent Asian, and Asians constituted 14 percent of the population of the edge city and mall hub of Schaumburg.30

As these suburban addresses indicated, many of the Asians merged readily into American middle-class life and earned praise as a “model minority.” Although some rejected this tag as just another example of stereotyping and as a convenient means for masking the unevenness of Asian achievement and the difficulties some newcomers faced, the model image survived and found some statistical support. Data for 1990 from the Los Angeles region recorded that among persons twenty-five years or older, 40 percent of the area’s foreign-born Chinese, 54 percent of its foreign-born Filipinos, 55 percent of its Indian immigrants, and 38 percent of newcomers from Korea had a college degree or more, as compared with only 31 percent of the native-born whites and 16 percent of the native-born blacks. Of foreign-born Asians in the age category twenty-five through sixty-four, 39 percent had high-skill occupations, as compared with 44 percent for whites and 31 percent for blacks, but among native-born Asians in the Los Angeles region the share holding these elite jobs rose to 50 percent. In 1989 the median household income of Los Angeles’s foreign-born Asians was $40,000, as compared with $43,000 for whites and $26,000 for blacks; for Asians born in the United States, it was $48,000.31 These newcomers were not, then, the stereotypical downtrodden, deprived masses of American immigrant lore. On average, they were better educated than the American norm, and after one generation in the United States they surpassed by a considerable margin older settlers in household income. The relatively impressive statistics were in part owing to the preference given to the skilled and educated by the federal immigration law. Whereas millions of unschooled, unskilled, and impoverished Latin Americans entered the country illegally, relatively few Asians did so. It was easier to sneak across the Rio Grande than the Pacific Ocean, which gave Latin Americans a distinct advantage in evading American immigration law. Geography dictated that Asians conform to the federal government’s immigration standards.

Perceived as hardworking, skilled, highly intelligent, law-abiding, and ambitious by the American majority and its media, Asians were the poster children for those proclaiming the merits of the new wave of immigration and the emerging diversity and inclusiveness of the nation. In its 1985 special issue on America’s immigrants, Time magazine observed favor-ably of the newcomers: “So many of the Asians come from the middle class, or aspire to the middle class, and are driven by a stern Confucian ethic.” Moreover, it quoted a demographer who characterized the Asians as “the most highly skilled of any immigrant group our country has ever had.”32 Reporting in 1991 on the migration of local Asians to suburbia, the Chicago Tribune expressed the prevailing media view: “The common American perception of Asians as educated, hard-working professionals has ultimately worked in their favor.” When the Tribune wrote of the Asian stores along Argyle Street on Chicago’s North Side, it expanded on this favorable image. “Wander down Argyle, right into Asia, where the food is fresh and the faces friendly,” the newspaper told its readers. In the older black–white city of Chicago, minority faces were not perceived by the white majority as friendly. Here, however, was a new, and seemingly better, minority whose neighborhood was a welcoming, pleasurable destination. In the words of the Tribune Argyle was a “street of dreams.”33 Earlier minority streets had been the stuff of white nightmares.

The largest group of Asian immigrants was the Chinese. In 1960 there were 237,000 Chinese Americans; in 2000 there were 2.8 million. During the intervening four decades, more than 1.3 million newcomers legally entered the United States from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.34 The ouster of the Taiwan-based Republic of China from the United Nations in 1971, the fall of Saigon in 1975, the gradual establishment of relations between the United States and Communist China during the 1970s, and British plans to relinquish Hong Kong to Communist China all seemed to threaten the interests of anti-Communist Asian capitalists and encouraged an influx of Chinese immigrants to the United States, the one eminently secure bastion of anti-Communist capitalism in the world. Many of the Chinese immigrants were not wealthy, but a good portion of the newcomers had money and skills that they sought to invest and utilize in America.

The influence of the new Chinese Americans was especially evident in the suburbs of the San Gabriel Valley, east of Los Angeles, and specifically in the city of Monterey Park. This suburb had developed largely during the first two decades following World War II when thousands of middle-class, single-family homes typical of American suburbia arose to house native-born white Anglos. The community did, however, attract a number of upwardly mobile Hispanics and a few Asians, mostly Japanese Americans. In 1960 it was 85 percent non-Hispanic white, 12 percent Hispanic, and 3 percent Asian. During the 1960s, the Hispanic share increased markedly and then leveled off after 1970. Yet the Asian proportion continued to soar, reaching 34 percent in 1980 and 58 percent in 1990.35

Most of the newcomers were Chinese, and by 2000 Chinese/Taiwanese constituted over 40 percent of Monterey Park’s population. During the 1970s, Chinese American real-estate developer Frederic Hsieh promoted this immigration, advertising Monterey Park as the “Chinese Beverly Hills” in Chinese-language newspapers throughout Asia. Monterey Park was sold as the place to go for those who wanted a safe haven in North America. A brochure issued by a Taiwan-based immigrant consulting firm promised: “In Monterey Park, you can enjoy the American life quality and Taipei’s convenience at the same time.”36 This advertising attracted immigrants with cash and ambitions. “The first stop would be the Mercedes dealer and the second stop would be the real estate broker,” observed one Chinese American who served as a liaison to the newcomers. Speaking of these immigrants he claimed: “This group of businessmen—entrepreneurs—were bolder, more boisterous, more demanding and sometimes even cunning.”37

The influx of Chinese residents spawned a multitude of new businesses catering to Asians. By 1989, six of the city’s eight supermarkets were Chinese owned. In 1981 Diho, a branch of a Taiwan-based supermarket chain, opened; later the Hong Kong Supermarket welcomed its first customers on the site of a former skating rink. Indicative of the changing times, the American chain store Alpha Beta gave way to a supermarket with the name Ai Hoa, which was Chinese for “Loving the Chinese Homeland.”38 According to one student of the city, “In the new supermarkets, Chinese is the language of commerce, and the stores feature fifty-pound sacks of rice, large water tanks with live fish, and rows of imported canned goods that are generally unrecognizable to a non-Chinese shopper.”39 By the close of the century, Monterey Park was headquarters for three Chinese-language newspapers distributed internationally, could boast of numerous Chinese-owned mini-malls housing hundreds of shops, and had more than sixty Chinese restaurants. In 1977 Frederic Hsieh had told the local chamber of commerce, “You may not know it, but this [Monterey Park] will serve as the mecca for Chinese business.”40 Twenty years later, his prediction had proved remarkably accurate. Moreover, just as the Cubans were praised for rejuvenating Miami, the Chinese were widely credited with having brought new life to the commerce of Monterey Park and the surrounding San Gabriel Valley communities. “Business strips once moribund have been revitalized with an infusion of Asian (Chinese) enterprise and money,” reported the Los Angeles Times in 1987. “Lots that were vacant only a few years ago now support an odd meld of suburban mini-malls and pulsing Far East marketplaces.”41

By the 1990s, Monterey Park had won a reputation as America’s first suburban Chinatown. Nicknamed “Little Taipei,” Monterey Park was supposedly a diminutive version of Taiwan’s capital transplanted to southern California. As such, it was a comfortable and appealing environment for Chinese newcomers. Just as West Hollywood was a community designed for gays and Beverly Hills for the wealthy, Monterey Park was a preserve for Chinese Americans. One Chinese woman explained why her compatriots congregated in Monterey Park: “Living here we feel just like home. There are so many Chinese people and Chinese stores, restaurants, banks, newspapers, radios, and TV, almost everything you need.” “Want to know why I moved here?” responded another Chinese resident. “Let me tell you something: I usually have a morning walk along Monterey Park’s streets. You know what? All I see are Chinese, there are no foreigners at all!”42 In the typical amorphous American metropolitan mass of the 1990s, there was no longer a single, common focus of urban life, acknowledged by all residents. Instead, there was a multitude of fragments. And Monterey Park was the fragment for the Chinese. In fact, it was known as a center of business and residence throughout much of the Chinese world. “You’re from Los Angeles?” a Taiwan resident asked a visiting Californian. “Isn’t that near Monterey Park?”43 For the Chinese, Los Angeles was a suburb of Monterey Park.

Monterey Park, however, was not actually the Chinese Beverly Hills. That title correctly went to nearby San Marino. One of the wealthiest communities in southern California, with a median household income of $117,000 in 1999, San Marino was a quiet retreat of palatial homes and lush plantings, a symbol of material success. In 2000 almost half its thirteen thousand residents were Asian, with Chinese/Taiwanese accounting for over 40 percent of the population. San Marino dramatically demonstrated that at the close of the twentieth century, foreign-born and minority did not necessarily equate with poverty. No one could deny that many Chinese could not even afford more humble Monterey Park. Less affluent and less educated than their West Coast counterparts, New York City’s Chinese immigrants crowded into tenements in Manhattan’s Chinatown or migrated to working-class and lower-middle-class neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Queens.44 But the ethnic lifestyle of the San Gabriel Valley did challenge long-established stereotypes. At least in California, the old pattern of poor minorities confined to the central city and excluded from more affluent white suburbs no longer prevailed.

The Chinese were not the only Asians earning a reputation as entrepreneurs. From 1976 to 1990, the number of Korean immigrants averaged thirty thousand a year, the wave of newcomers peaking in 1987. As South Korea’s economy improved in the 1990s and the relative standing of the United States as a land of opportunity diminished, the influx declined, averaging only seventeen thousand annually from 1991 through 2000.45 But by the close of the century, Koreans had established a definite presence in the United States, winning a reputation as hardworking small-business owners. In 1986 an estimated 45 percent of Korean newcomers in Los Angeles and Orange counties were self-employed, the highest rate of self-employment for any minority or immigrant group (figure 6.2), and the figure for New York City’s Korean immigrants was at least as high.46 A large portion of those who were not self-employed were working in small Korean-owned businesses, preparing to strike out on enterprises of their own. Explaining this predilection for self-employment, one Korean-born lawyer observed: “One thing about Koreans is that they don’t like to be dominated by anybody.”47

On both the West and East coasts, Koreans carved out an economic niche for themselves. In New York City, they became known for their small produce stores. By the late 1990s, there were approximately two thousand Korean-owned stores specializing in fresh fruits and vegetables in the city, constituting about 60 percent of New York’s independent produce retailers. There were also about 1,500 Korean-owned dry cleaners in New York, and Koreans controlled 50 percent of the city’s manicure salons. In southern California, Koreans owned thousands of small grocery and liquor stores and operated swap meets. These meets were gatherings of small dealers who sold a wide variety of merchandise for cut-rate prices. Not confined to ethnic enterprises, southern California’s Koreans owned an estimated 550 American fast-food businesses by the mid-1990s.48 Moreover, many of these newcomers embraced a work ethic that native-born Americans often professed but seldom practiced. “We should work harder than other Americans,” remarked the Korean owner of a dry-cleaning chain in southern California. “Otherwise we cannot succeed.”49

FIGURE 6.2 Los Angeles congressman appealing to his increasingly diverse constituents in a parade through Korea Town, 1984. (Mike Sergieff, Herald Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library)

Although Korean immigrants operated businesses throughout Los Angeles and New York City, they became known specifically for their willingness to establish stores in poor black and Hispanic neighborhoods, tapping markets that non-Hispanic white entrepreneurs and major chain retailers avoided. At the beginning of 1992, Los Angeles’s Korean Times estimated that 80 percent of the businesses in the city’s principal African American area were owned by Koreans, including one thousand swap meet stores and six hundred outlets selling groceries, liquor, gasoline, and other merchandise.50 Earlier in the twentieth century, Jewish immigrants had filled the retailing needs of poor minority neighborhoods ignored by more established native-born merchants. During the last two decades of the century, Koreans supplanted the Jewish retailers in the black ghettos of Los Angeles and New York City, seeking to make a profit where few others dared to operate.

Joining the Koreans in the struggle for success were hundreds of thousands of Filipinos who, among the Asian newcomers, were second in number only to the Chinese. Filipino immigrants were largely concentrated in California, and Daly City, immediately south of San Francisco, became the Filipino version of Monterey Park. By 2000, a majority of the city’s 104,000 residents were Asian, and more than 30 percent of the total was Filipino. “Over the past two decades, Filipino immigrants have flocked to Daly City, transforming the bedroom community into a mini-metropolis with a distinctly Pacific flavor,” reported one observer in 1996. “Filipino restaurants dot the city’s shopping strips,” he noted; “bagoong, tinapa, daing, kamote, and kamoteng kahoy—staple foods in rural Philip-pines—are readily available in dozens of Oriental stores.” If Monterey Park was “Little Taipei,” Daly City was “Little Manila,” a hub of transplanted Filipino life in northern California. “When people talk of Daly City, they talk of Filipinos,” commented a prominent local Filipino American. “I’ve seen Filipino movies in which a character would say: ‘If I go to America, I’d go to Daly City.’” Suburban Daly City represented making it for many Filipinos who had spent their first years in America in the crowded central-city neighborhoods of San Francisco. “This city has been good to us,” asserted a boosterish Filipino American realtor. “We can raise our children well, acquire property, and not be exposed to hostility and discrimination. We’re free to pursue our American dream.”51

Also pursuing that dream was a wave of newcomers from India. Whereas Filipinos preferred the West Coast, the largest concentration of Indians was in the New York City area, especially in the borough of Queens, where one could shop at the India Sari Palace, bank at a branch of the State Bank of India, worship at a Hindu temple or a Sikh gurdwara, and watch devotees accompany a Hindu deity’s chariot through the streets during the festival of Ganesh Chaturthi. Generally well educated and members of India’s upper or middle classes, the immigrants had high expectations for material success, and many realized their goals. By the close of the century, an increasing number were moving to the suburbs of Long Island and northern New Jersey, drawn by the opportunity of owning a home and sending their children to better schools than the central city afforded. Suburban Long Island movie theaters ran films from Bombay, and as many as fifteen thousand South Asians jammed the Coliseum in Long Island’s Nassau County several times each year to see live performances by Bombay movie stars.52 Although admitting that some Indian immigrants were limited to “mundane or even menial jobs,” a student of the South Asian newcomers concluded that “overall this is an immigrant group whose education, hard work and ambition have boosted them to middle- or upper-middle-class status within U.S. society.”53

The one Asian group that offered less statistical support for the notion of the model minority was the Southeast Asians from Indochina. Largely impoverished refugees fleeing the Communist takeover of the area in the 1970s, these newcomers on average had less education and less financial resources than the Indians, Filipinos, Koreans, or Chinese. The United States government attempted to distribute Indochinese refugees throughout the nation, but a disproportionate share settled in California, with the largest concentration in Orange County, south of Los Angeles (figure 6.3). A “Little Saigon” with numerous businesses catering to Vietnamese newcomers developed in the city of Westminster, and the proliferation of small Vietnamese-owned businesses contributed to the prevailing stereotype of Asians as successful entrepreneurs. Although the Indochinese ranked behind their fellow Asian immigrants in terms of household income and college education, some believed that they were on the way to prosperity. In 1990 a study of southern California’s Southeast Asians reported that “the number one concern of the refugees in Orange County is unemployment” but concluded that the immigrants “have already contributed to the booming Orange County economy by providing a labor force that is hard working, thrifty, competitive, and with strong family values. Employers surveyed about their experience of having Southeast Asians as employees are overwhelmingly positive.”54

FIGURE 6.3 Example of southern California’s growing cultural diversity: Vietnamese ceremony, 1980s. (Dean Musgrove, Herald Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library)

Vietnamese, Indians, Filipinos, Koreans, Chinese, Dominicans, Salvadorans, Mexicans, Cubans all joined blacks and non-Hispanic whites to form what New York City’s mayor David Dinkins celebrated as a “gorgeous mosaic.” Metropolitan America could no longer be viewed as simply black and white; it was rich in various hues with a mix of people from throughout the world. The result was a new amalgam quite different from that existing in America’s urban centers in 1945. Nowhere was this gorgeous mosaic more evident than in the Elmhurst–Corona district of Queens in Dinkins’s own city. In the late 1990s, an anthropologist reported: “On a heavily Latin American block of Roosevelt Avenue in Elmhurst, an Indian, a Chinese, and a Korean store coexisted with seven Colombian, Dominican, and Argentinean firms; and facing William Moore Park in Corona, one Jewish, one Korean, two Greek, and two Dominican stores were scattered among fourteen Italian businesses.” Moreover, “at La Gran Victoria, a Dominican Chinese restaurant in Corona Plaza, a Chinese waiter speaking fluent Spanish served four young Latin Americans who ordered Chinese dishes, and nothing from the comidas criollos side of the menu.” In addition, he recorded that the Chinese-owned Century 21 Sunshine Realty employed speakers of “Mandarin, Taiwanese, Cantonese, Hakka, Spanish, Italian, German, Polish, Korean, and ‘Indian,’” and the Colombian-owned Wood-side Realty Corporation could deal with customers in Spanish, Hebrew, Korean, and Mandarin as well as English.55

Such a babel of tongues confirmed New York City’s long-standing reputation as a port of entry for America’s immigrants. In the late twentieth century, however, Dinkins’s gorgeous mosaic was not only found in the central city but in once homogeneous suburbs. A study published in 1989 found that the most ethnically diverse city in the United States was not New York or Chicago but the upper-middle-class Los Angeles suburb of Cerritos, a community especially notable for its wide range of Asian nationalities.56 Nor did suburban communities grow any less diverse during the following decade. In 2003 USA Today carried a front-page story that proclaimed “‘New Brooklyns’ Replace White Suburbs.” “A whole class of traditional, white-bread suburb has turned into a new kind of city” reminiscent of Brooklyn in the past, incubators for hardworking immigrants on the path to middle-class life. According to the newspaper, Anaheim, California; Irving, Texas; and Pembroke Pines, Florida—all distant geographically from Ellis Island and in lifestyle from the old immigrant hub on Manhattan’s Lower East Side—were the crucibles for the American future where the promise of the gorgeous mosaic was being realized.57

In the last decades of the twentieth century, then, the ethnic portrait of metropolitan America was changing markedly. The signs of change were everywhere. Our Lady of Guadalupe was receiving a place of honor in a Polish basilica, the Ai Hoa market was supplanting the Alpha Beta, South Central Los Angeles was turning from black to brown, and residents were speaking Chinese in San Marino and Spanish in Coral Gables. Immigrants from Taiwan dreamed not of the Statue of Liberty but of Monterey Park, and Daly City was the focus of Filipino aspirations. Americans had moved beyond the black–white city.

The Uneasy Transition

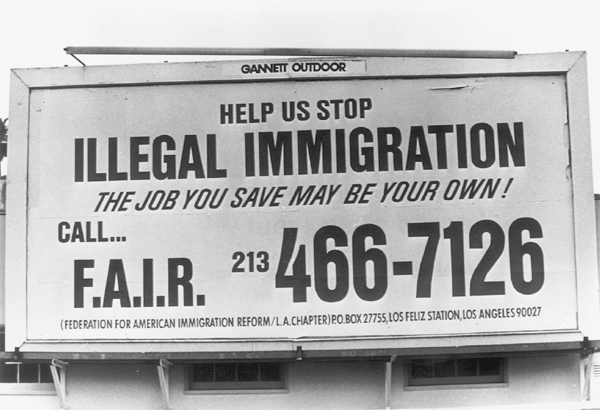

Not everyone, however, was happy about the changes occurring in metropolitan America. For some native-born Americans, both black and white, the new ethnic diversity was troubling and even threatening. As neighborhoods changed and foreign tongues and different complexions became commonplace in nearby shopping streets, some Americans felt that they were losing hold of their communities and becoming aliens in places where they had lived all their lives. Unfamiliar sights, sounds, smells, and manners offended their sensibilities. A number of the native-born also perceived the newcomers as economic competitors. Given the widespread perception that many of the immigrants were hardworking go-getters, employers might naturally prefer the newcomers to native-born job seekers (figure 6.4). Moreover, the sight of successful, well-heeled “foreigners” cruising the streets in Mercedeses could prove disturbing to native-born residents who had never been able to rise one rung on the economic ladder and feared slipping even lower. Altogether, the strangeness of the newcomers could prove unsettling, and their success raised doubts that the fulfillment of the American dream was reserved only for Americans.

FIGURE 6.4 Anti–illegal immigration billboard in Los Angeles. (Michael Edwards, Herald Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library)

Among non-Hispanic whites, anti-immigrant sentiment focused on the newcomers’ refusal to give up their native languages. Miami was the scene of one of the earliest English-only battles. In 1973 the Dade County Commission decided to adopt a bilingual policy, publishing official documents in both English and Spanish, hiring Spanish-speaking personnel to serve Hispanics, and posting signs that offered information in both languages. In 1980, however, an Anglo group called Citizens of Dade United led a referendum campaign to eliminate bilingualism in the county. If adopted, the referendum measure would prohibit “the expenditure of county funds for the purpose of utilizing any language other than English, or promoting any culture other than that of the United States.” Moreover, it required that “all county government meetings, hearings, and publications shall be in the English language only.” One of the leaders of the referendum campaign, a multilingual Russian Jewish immigrant, explained that because of the prevalence of Spanish she “didn’t feel like an American anymore” in Dade County.58 “How come the Cubans get everything?” she asked, and she made it clear that she wanted Miami to return to “the way it used to be.”59

Other non-Hispanics agreed. One English speaker complained: “Our people can’t get jobs because they can’t speak Spanish.” Another laid it on the line: “Hey, buddy, if you want to speak Spanish, go back to Cuba.” The Spanish-American League Against Discrimination led the fight against the proposal, and a spokesperson for the United Cuban-Americans of Dade County protested: “There are 200,000 Cubans here who can’t speak English, but they pay taxes and they buy Coca-Cola.”60

On election day, however, the antibilingual forces triumphed as the electorate split along ethnic lines. An estimated 71 percent of the non-Hispanic whites supported the measure, whereas 80 percent of Hispanics casting ballots voted against it.61 Yet the victory was largely symbolic; it did not halt the widespread use of Spanish in the Miami area or return Dade County to the way it used to be. In 1986 a Miami Herald columnist observed: “A good many Americans have left Miami because they want to live someplace where everybody speaks one language: theirs.”62

Language also became the crux of controversy between non-Hispanic whites and Asians in Monterey Park. In 1985 the National Municipal League and USA Today named Monterey Park an “All-American” city in recognition of its ethnic inclusiveness and its efforts to incorporate immigrants into the community. Yet beneath the facade of harmony were interethnic tensions that manifested themselves in complaints about the proliferation of business signs in Chinese. Critics of Chinese signage claimed that if storeowners failed to include an English translation on their signs, then firefighters and police would not know where to answer a call. Monterey Park’s city attorney, however, claimed that “the police and fire know what is there, no matter what language you put on it” and argued that “it was just absolute nonsense to suppose that there was some public welfare reason for the fight that went on; it was political.” Although the Chinese American mayor acceded to pressure and proposed an ordinance requiring an English translation on Chinese signs, some residents felt that this was not enough, presenting arguments that supported the city attorney’s contention that public safety was not the principal concern. In a letter to the local newspaper, Frank Acuri expressed the anger of many residents when he said the proposed signage ordinance did not “address the real issues. The problem is that Asian businesses are crowding out American businesses in Monterey Park…. Stores that post signs that are 80 percent Chinese characters make us feel like strangers in our own land…. I will go a step further than the proposed law and say that all signs must be completely in English.”63

Acting on his sentiments, Acuri and another resident, Barry Hatch, organized a petition campaign to make English the official language of Monterey Park. Acuri claimed to enjoy diversity, but he complained that “now all of a sudden, to have a group come to our city, which in this case is Chinese people, with enough money so they can buy our city, buy our economy and force their language and culture down out throats, this is what’s disturbing to people in Monterey Park.” Hatch concurred: “When we look up and see all these Chinese characters on signs—why, it feels foreign to us. It is one bold slap in the face, which says to us, ‘Hey, you’re not wanted.’”64 Eventually, the city council passed a resolution that favored making English the official language of the United States. Reacting to the English-only sentiment, a group of Asians, Hispanics, and Anglos joined together in the Coalition for Harmony in Monterey Park and forced the council to rescind the measure.

Monterey Park was not the only community embroiled in battles over Chinese signs. By 1994, ten cities in the San Gabriel Valley had taken measures to require English on business signs.65 The Chinese could and did continue to expand their commercial role in the valley, but sensitive city officials preferred that they not advertise their takeover too blatantly. They could profit but should avoid slapping those like Barry Hatch in the face.

Led by the Japanese American former United States senator from California S. I. Hayakawa, an organization called U.S. English promoted the English-only cause nationwide, seeking a federal constitutional amendment to make English the nation’s single official language. Colorado governor Richard Lamm vigorously supported the effort, claiming: “We should be a rainbow but not a cacophony. We should welcome different people but not adopt different languages.” No federal amendment was adopted, but Californians acted to make English the official language of their state. In 1986 they approved Proposition 63 by a 3 to 1 margin; it directed the legislature to “take all steps necessary to insure that the role of English as the common language of the state of California is preserved and enhanced” and prohibited any law that “diminishes or ignores the role of English.”66 The New York Times editorialized that the Proposition 63 campaign “smacked of a mean-spirited, nativist irritation over the influx of Mexicans and Asians.”67 Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley warned that the proposition could “stir hatred and animosity. It could tear us apart as a people.”68 Eight years later, Californians adopted the equally divisive Proposition 187, which cut off state services to illegal immigrants. Aimed especially at the many illegal newcomers from Latin America, the proposition won support from two-thirds of the state’s non-Hispanic whites, whereas Hispanics opposed it by a 3 to 1 margin.69

In California, Florida, and elsewhere, the non-Hispanic white reaction to the newcomers was not, then, altogether positive. English-only campaigns reflected anxiety about ethnic change and a perceived cultural threat deeper than just Chinese characters on business signs. Despite the laudatory talk about model minorities and their contributions to American society, the influx of hardworking Asians and enterprising Cubans was deemed by some as a threat to the comforting homogeneity of their white, English-speaking world. Yet when compared with earlier white opposition to the arrival of blacks in their neighborhoods, the response to the Asians and Hispanics was relatively mild. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, barrages of stones and bottles welcomed “race invaders” in the white areas of Chicago and Detroit. By comparison, a 1986 account of Chicago’s Lower West Side reported that “by and large, the transition from an Eastern European neighborhood to a predominantly Hispanic one has been peaceful.”70 Whites required Chinese storeowners to include English translations on their business signs; whites did not burn down their stores or attack their homes. Violent mob action did not greet Cuban newcomers to Hialeah or Coral Gables or accompany the latinization of Anaheim or the Filipino migration to Daly City.

Moreover, white reaction to the newcomers did not replicate earlier attitudes of the black–white city. In Miami and southern California, many non-Hispanic whites were resentful not of the inferiority of the immigrant groups or of their depressing effect on property values. Instead they resented the pretensions or manifestations of superiority among some of the newcomers. Cubans were seen as getting it all; Chinese-only signs advertised to Anglos that their patronage was not desired; repeated complaints of too many Asians in Mercedeses expressed bitterness that the American dream was being realized by non-Americans while still proving elusive to the native-born. Everyone recognized, and some complained, that the Chinese inflated property values in the San Gabriel Valley, and Cubans were widely viewed as having boosted the fortunes of Miami. Poor Mexican and Central American immigrants might be criticized as relatively unschooled burdens on the native-born, middle-class taxpayers, but the newcomers of the late twentieth century were not seen uniformly as weighing down the nation’s standard of living or draining the public treasury.

Many white Anglo complaints also focused on the self-imposed cultural segregation of the newcomers and their unwillingness to integrate into American society. A Westminster, California, city council member denied Vietnamese military veterans permission to parade, telling them: “It’s my opinion that you’re all Americans and you’d better be Americans. If you want to be South Vietnamese, go back to South Vietnam.”71 Vietnamese veterans should not march separately but join in the American parade; Chinese should advertise in English like good Americans; Cubans should speak English and give up their obsession with returning some day to a liberated Cuba. The white, native-born population believed that immigrants should speak English and become like “us.” This was a different message from that prevailing in the black–white city of 1945. Blacks were expected to remain apart; in the minds of many whites, blacks did not have the innate capacity to become like “us.”

Compared with the white, Anglo response, the African American reaction to the newcomers was often more troubled and sometimes violent. The poor Latin immigrants threatened to take low-skill jobs away from blacks, and the entrepreneurial Asians and Cubans often worked their way into the middle class by profiting from businesses in black neighborhoods. The newcomers too often seemed like both competitors and exploiters, getting ahead at the expense of the native-born minority that had long suffered white oppression. Moreover, the concept of model minorities, widely disseminated by the media, was a veiled insult to African Americans. It implied that some minorities familiar to white Americans were not model, and everyone knew which one minority was deemed less than model. When the model attributes—hard work, ambition, higher education, and strong family ties—were listed, they seemed to describe everything the stereotypical black welfare mother of white imagination was not. And when Koreans, Indians, and Cubans boasted of having worked their way to success despite their minority status and alien origins, it appeared to be an unspoken challenge to the long-standing black minority to energize itself and do likewise. There were new minorities on the block who were seemingly showing up the old minority, and the resulting black resentment was understandable.

Black-Cuban hostility was a major theme in the history of late-twentieth-century Miami. In the minds of many blacks, the influx of Cubans deprived African Americans of the opportunity to get better jobs or develop businesses because Anglo employers and bankers preferred hiring and lending to white Cubans rather than to black Americans. It was reported that in 1960, blacks owned 25 percent of the gas stations in Dade County and Cubans owned 12 percent. By 1979, the figure for blacks was 9 percent and for Cubans 48 percent.72 Cuban businesses proliferated, seemingly depriving blacks of the opportunity for enterprise and upward mobility. “The only things blacks have in Miami are several hundred churches and funeral homes,” complained one observer in the early 1980s. “After a generation of being Southern slaves, blacks now face a future as Latin slaves.”73 In the 1990s, a local black civil rights leader expressed his exasperation with the economic consequences of the takeover by Spanish-speaking Cubans: “There have been enough people brought to the country that have the jobs now, that the African American used to have and could have. But because No. 1, he doesn’t speak Spanish, it’s difficult to get the job…. It excludes me from work in my own community—in my own country.”74 A resident of Miami’s black slums reiterated this sentiment: “They bring everybody to Miami. Nicaraguans, Cubans, Haitians. And we’re still on the bottom. We can’t even get to the first step to make it to the top.”75

The animosity between blacks and Cubans was evident in the local media. In 1990 the African American Miami Times editorialized about the “Cuban Mafia” who controlled Miami, “bullying and threatening all those who do not toe the line.”76 A survey of the Miami Times editorials from the early 1960s to the early 1990s found that only 11 percent of the newspaper’s references to Cubans were positive, 60 percent were negative, and the remainder neutral.77 The African American newspaper did not always side against the newcomers. It opposed the 1980 English-only initiative as racist, although in 1988 it refused to denounce a proposed Florida constitutional amendment that would declare English the state’s official language. A 1980 Miami Herald poll demonstrated that anti-Cuban feelings were stronger among blacks than among non-Hispanic whites. When asked whether the influx of Cubans before 1980 had a positive or negative effect on Miami, only 29 percent of the Anglos answered negatively, as compared with 45 percent of the black respondents.78

Local African Americans seemed especially exasperated that Cubans showed relatively little concern for race relations and few of the signs of racial guilt that blacks expected from white people in the post–civil rights era. “[Native whites] are racists by tradition and they at least know what they’re doing is not quite right,” commented one black Miamian. “Cubans don’t even think there is anything wrong with it. That is the way they’ve always related, period.”79 In the 1980s, one observer of Miami concluded that “in South Florida, one almost has the feeling that the Cubans wonder what these black people are doing in this second Havana,” and a 1990s study of Cuban–black relations reported that “the Spanish-language daily press is marked by a lack of interest toward blacks.”80 In 1993, after the black Miami Times criticized Cubans for their insensitivity toward African Americans, the newsletter of an organization of Hispanic county employees explained Cubans’ refusal to bear the burden of racial guilt: “It may be okay with Anglos, since, historically, they are guilty of enslaving and degrading blacks for centuries; they owe blacks. But folks, we Hispanics owe blacks nothing.” It asked: “What are we guilty of? Of hard work, not only as bankers and entrepreneurs, but also as humble laborers and peddlers? Keep it clear in your head that we have never coerced assistance from anyone, but would much rather roam the streets of Miami selling limes, onions, flowers, peanuts, etc. Some folks should try this, it is hard work, but not bad.”81 In other words, blacks should stop blaming innocent Cubans, get off the welfare rolls, and get to work. It was a message that did nothing to heal ethnic wounds in South Florida.

By 1993, these wounds were festering, owing to a number of well-publicized clashes between the newcomers and the old-time minority. In 1980 rioting swept through the black Miami neighborhood of Liberty City after the acquittal of white police officers charged with the fatal beating of a black man. Although the outbreak was not specifically aimed at Hispanics, the rioters did not discriminate between Anglos and Cubans. “During the riot, we hit everybody, Anglo, Cuban, it didn’t matter,” a black leader admitted.82 Then, in 1982, a Cuban American police officer shot and killed an African American in the black ghetto of Overtown, touching off three days of rioting. And in 1989 a Hispanic officer shot and killed an African American motorcyclist, again resulting in three days of rioting by local blacks. Although the officer was actually Colombian, for blacks it was just one more example of Cuban oppression. “What I want to know is how come it’s always the Cubans that’s shooting the niggers,” asked a local African American. A black former police officer admitted: “The Cu-bans will shoot a nigger faster’n a cracker will.”83

Then, in 1990, the black South African leader and renowned foe of racial apartheid Nelson Mandela visited Miami and ignited a clash that widened the chasm between blacks and Cubans. Mandela had expressed support for Cuban Communist leader Fidel Castro and had personally thanked Castro for his support for the battle against apartheid. This incensed Miami’s Cuban community, and five Cuban American mayors from Dade County, including the mayor of Miami, signed a statement condemning Mandela. The Miami City Commission also refused to adopt a resolution honoring the black foe of racial oppression. “We’re really disappointed by these actions that serve not only to exacerbate deep wounds but to further entrench the racial polarization that has our city in its grip,” observed the publisher of the black Miami Times. A black civil rights leader proclaimed: “We’re tired of this racism, and we’re not going to tolerate it anymore.”84 Local African American leaders called on national organizations to boycott Miami as a conference and convention site. Over the next two and a half years, the city lost an estimated $50 to $60 million in convention business owing to the boycott, the cost of the bitter rift between the Hispanic and African American communities.

In southern California, the rift was perhaps not so pronounced, but there was tension owing in part to competition between blacks and Latinos for low-skilled jobs. Moreover, it seemed that the newcomers had an advantage in the contest for employment. By the early 1990s, Los Angeles janitorial firms had largely replaced their unionized black workers with nonunion immigrants. A 1992 article in Atlantic Monthly commented on the “almost total absence of black gardeners, busboys, chambermaids, nannies, janitors, and construction workers in a city with a notoriously large pool of unemployed, unskilled black people.” It claimed that “if Latinos were not around to do that work, nonblack employers would be forced to hire blacks—but they’d rather not. They trust Latinos. They fear or disdain blacks.” The article concluded that “to Anglos, Latinos, even when they are foreign, seem native and safe, while blacks, who are native, seem foreign and dangerous.”85 Employing sophisticated statistical analysis, a scholarly study published in 1996 came to much the same conclusion, finding that “both Latino immigration and racism play significant roles in disadvantaging African Americans in terms of joblessness and earnings.”86

Even more important than scholarly conclusions was the widespread perception among the black community that Hispanics were a threat. Indicative of this was the conflict over the much publicized 1992 campaign of African American Danny Bakewell to shut down Los Angeles construction projects that failed to employ blacks. In response to this crusade, His-panic Xavier Hermosillo organized teams of undercover construction workers armed with video cameras who taped Bakewell’s efforts to replace Hispanics with blacks.87 Seemingly any employment for Latin newcomers was deemed a loss for African Americans, and Bakewell sought to stanch this flow of jobs to nonblacks.

Tied to the clash over jobs was discontent over the distribution of political power. Control of city hall meant public-sector jobs as well as public programs sensitive to the needs of the dominant ethnic group. This became the crux of controversy between African Americans and Hispanics in the black-dominated suburb of Compton. By the 1990s, a majority of the children in Compton’s schools were Latino, but the blacks who controlled the school board were reluctant to spend money on bilingual education. “This is America,” remarked one black school trustee. “Because a person does not speak English is not a reason to provide exceptional resources at public expense.” Black youths fought Latino teenagers in the city’s public schools, a videotape showed a black Compton police officer beating a Hispanic youth, and African American officials refused to share a sufficient portion of public-sector jobs with the lighter-skinned invaders from south of the border. One local Hispanic claimed: “A few years ago the white man was doing this to the black man and now black men are doing this to brown people.” A black pastor agreed: “We are today the entrenched group trying to keep out intruders, just as whites were once the entrenched group and we were the intruders.”88

Many black leaders were sensitive to Hispanic concerns in southern California and supposed manifestations of discrimination against the newcomers. The black president of the Los Angeles Urban League condemned Proposition 187, telling African American voters: “There are black people and other minority people who are at odds over jobs. But if you’re black and you vote for 187, you’re not just voting against Hispanics, but you’re also voting for the kind of thing that has been used against blacks since time began.”89 The local chair of the NAACP also declared that he would vote against 187. But he recognized correctly that a large number of blacks would support the initiative. Given the “long-running tensions between the black and Latino communities,” the NAACP leader argued, “many black people don’t care that Proposition 187 is being financed by racist organizations…. If the initiative creates a McCarthyite police state, the attitude is, ‘So be it.’”90

The sharpest conflict, however, arose between African Americans and Asians, specifically Koreans. The Asian newcomers became leading retailers in black neighborhoods, and tension between customers and merchants was manifest in cities across the country. A survey of newspapers in thirty-nine American cities found reports of forty black-led boycotts of Korean-owned stores in thirteen of the cities during the 1980s and first half of the 1990s. These included the boycott of a flea market in Miami, a minimart in Philadelphia, a beauty shop in Indianapolis, and a shopping center in Dallas. Moreover, there were reports of sixty-six violent incidents between African Americans and Koreans in sixteen cities, including thirty-two shootings. In twenty-six cases, an African American shot a Korean, and in the remaining six incidents a Korean was the shooter.91 Often the boycotts and violence arose from a scuffle between a Korean shopkeeper and a black customer who was suspected of shoplifting. But African Americans also complained of poor merchandise, high prices, and generally rude treatment by Korean retailers. And many blacks regarded the Koreans as economic parasites draining the African American community of cash and contributing little in return.

In 1990, for example, a conflict between Korean merchants and black customers in Chicago’s Roseland district raised many concerns commonly expressed in other cities as well. A flier distributed among African Americans bore the headline, “Lets Take Control of Our Community!” Referring to Korean storeowners, it asked: “Why don’t they: Treat us with respect. Bank in our banks. Provide substantial employment. Donate to our community activities.” Reiterating this, one black resident complained: “They take out money but they don’t put anything back into the community.” Another expressed the widespread resentment of suspicious Korean merchants who seemed to regard every black person as a likely shoplifter. “The worst thing is being watched like a hawk the whole time you’re in the stores. I don’t want to be followed around like I’m some thief.”92

The most highly publicized boycotts of Korean businesses were in New York City, revealing the ugly tensions underlying Gotham’s gorgeous mosaic. As early as 1981, New York’s black newspaper, the Amsterdam News, wrote of the “anti-Korean hysteria” among Harlem’s African American storekeepers, noting that “the situation is tense among both sides of the business community, and is seen in some circles as by far the most explosive issue to come out of the Black community since the Harlem riots of 1943.” The next year, the Afrikan Nationalist Pioneer Movement initiated a “Buy Black” campaign aimed at ridding Harlem of Korean merchants.93 The first boycott of a Korean store in Harlem began in October 1984 and lasted for more than three months. Demonstrators handed out fliers calling on blacks to “Boycott all Korean merchants.”94 The most notable boycott, however, was the campaign against the Red Apple and Church Fruits stores in Brooklyn in 1990/1991. Lasting for 505 days, it brought the black–Asian conflict to the attention of all New Yorkers and widened the division between militants on both sides. Although the protest arose from a tussle between Korean store employees and a black woman suspected of shoplifting, a boycott flier made it clear that there were larger issues at stake. “The question for Black folks to consider is this: ‘Who is going to control the economic life of the Black community?’’’ the flier explained. “People understand that this struggle we are presently engaged in is a continuation of our historical struggle for self-determination.”95

For Koreans, however, it was a struggle to maintain their right to do business in whatever neighborhood they desired. Around seven thousand Koreans, or approximately 15 percent of the Koreans in New York City, participated in a “peace rally” calling for an end to the boycott. Reminding Koreans of their own past oppression, speakers at the rally compared the boycott with the Japanese occupation of Korea during the first half of the twentieth century. The underlying message was that just as they had liberated themselves from the Japanese, they would overcome the black boycott leaders. Polls showed that only a minority of black New Yorkers supported the boycott, yet in the public’s mind the clash was a clearly defined battle between Asians and blacks. A New York Times editorial headlined “These Boycotts Are Racist, and Wrong” summed up prevailing opinion among both white and Asian New Yorkers.96

In Los Angeles, there were fewer and less protracted boycotts, yet no one could ignore the signs of deep anger and bitterness between blacks and Asians. In March 1991, a Korean storekeeper in the South Central district shot and killed a fifteen-year-old black girl, Latasha Harlins, after a fight over a container of orange juice that Harlins was supposedly stealing. In November, a white judge sentenced the Korean woman to five years’ probation and ordered her to pay a $500 fine and Harlins’s funeral expenses. The light penalty for what many blacks regarded as simple murder outraged the African American community. One Korean American remarked: “That probation decision just drove a deep wedge right between the black and Korean communities. There was no middle ground; you were either for us or you were against us.”97

Adding to the tense conditions was the release of the song “Black Korea” by Los Angeles rapper Ice Cube. Expressing rage at Asian store owners, Ice Cube rapped:

Don’t follow me, up and down your market

Or your little chop suey ass’ll be a target

of the nationwide boycott.

Then he went further, yelling:

Pay respect to the black fist

or we’ll burn your store, right down to a crisp

And then we’ll see ya!

Cause you can’t turn the ghetto—into Black Korea.98

Having already suffered fire bombings and fatal attacks from black robbers, Korean merchants reacted strongly to Ice Cube’s lyrics. “This is a life-and-death situation,” commented the executive director of the Korean American Grocers’ Association. “What if someone listened to the song and set fire to a store?”99

The following spring, a number of blacks did act out Ice Cube’s lyrics and wreak havoc on Korean-owned businesses. In April 1992, a jury acquitted four white police officers who had been videotaped beating black motorist Rodney King. The Rodney King verdict, coming just months after the light sentence imposed in the Harlins case, ignited three days of violent rage. Surpassing in violence the Watts riot of 1965, the Los Angeles uprising of 1992 resulted in more than fifty deaths, over fourteen thousand arrests, and about $1 billion in property damage (figure 6.5). Both blacks and Latinos participated in the rioting, the number of Hispanics arrested actually exceeding the number of African Americans; but the black participants seemed to be more violent, whereas the Latinos were more often looters seeking free merchandise. The chief victims were Korean Americans. Although Koreans accounted for only 1.6 percent of Los Angeles County’s population, they bore the lion’s share of property loss. Korean stores suffered an estimated $359 million in damage. According to city government records, one-third of the businesses damaged within the city of Los Angeles were owned by Koreans, and about three-quarters of the stores on the State Insurance Commission’s list of damaged properties were Korean-owned.100 Most agreed that rioters specifically targeted the businesses of the hated Koreans. “There is no doubt that in the violence following the verdict Korean merchants were, in fact, targeted for destruction,” commented a leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. “There was a nasty anti-Asian, anti-Korean mood circulating throughout the streets of L.A. We can’t deny it and we have to deal [with] that, straight up.”101