UNDER SUSPICION

By the time Franklin arrived in Philadelphia on May 5, 1775, fighting between the colonists and British soldiers had already broken out in Lexington and Concord. The year before, in order to enforce the Coercive Acts, the British Crown had replaced the much abused governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson, with a military commander in chief, Thomas Gage. Hutchinson went to England in exile, full of despair over what was happening in his beloved Massachusetts, just as his former royalist colleague was returning to the land of his birth. Because Franklin had become an international celebrity, he was interviewed by a newspaper editor upon his return—perhaps the first person in American history to be so greeted at the dock. In the news account Franklin urged Americans to stand firm and prepare for the struggle ahead. “He says we have no favours to expect from the Ministry; nothing but submission will satisfy them.” Only a “spirited opposition” could save Americans from “the most abject slavery and destruction.”1

Franklin brought with him from London his fifteen-year-old illegitimate grandson, William Temple Franklin, at last openly acknowledged as William’s son and called Temple by his family.2 Franklin moved into the Market Street house, which he had never before seen completed and which Deborah had labored to furnish in accordance with his precise instructions. He seems to have completely forgotten about Deborah, even though she had been dead for less than half a year. In no surviving document of this period does Franklin ever mention her. In fact, not a single friend or relative ever wrote him a note of sympathy or even referred to the death of his wife.3

The day after Franklin landed, May 6, the Pennsylvania Assembly elected him as one of its delegates to the Second Continental Congress, which was to meet in Philadelphia on May 10. At first Franklin tried to maintain a low profile. When he was not engaged in public business, he spent his time at home. Never a great speaker at best, he was unusually silent during the debates in the Congress. John Adams wondered what Franklin was doing in there, since “from day to day, sitting in silence, [he was] a great part of his time fast asleep in his chair.”4

Despite Franklin’s efforts to keep out of the limelight, however, he was the most famous American in the world and someone who presumably knew British officials and British ways as no other American did, and naturally everyone wanted to exploit his expertise and inventiveness for a variety of tasks. He was immediately appointed postmaster general and then assigned to a multitude of congressional committees. In between working on a petition to the king, the manufacture of saltpeter for gunpowder, and devices for protecting American trade, he found time to design the face of the proposed new currency and a model for pikes for the soldiers. He even drew up a revised version of his Albany Plan of Union for the colonies, which the Congress listened to but refused to record officially.

What impressed most delegates, however, was the intensity of Franklin’s commitment to the patriot cause. He seemed deeply angry at the Crown and British officialdom and was impatient with all efforts at reconciliation. He thought the various colonial petitions to the king were a waste of time; he fully expected a long, drawn-out war; and he believed that independence was inevitable. All this was startling to Americans who had come to believe that Franklin, because of his long residence in London, had to be more English than American. The degree of Franklin’s Revolutionary fervor and his loathing of the king surprised even John Adams, who was no slouch himself when it came to hating.5 Adams told his wife, Abigail, in July that Franklin had now shown himself to be “entirely American”; indeed, he had become the bitterest enemy of Great Britain, the firmest spokesman for separation. “He does not hesitate at our boldest Measures,” said Adams, “but rather seems to think us, too irresolute, and backward.”6 His passion for independence was all the more impressive coming from a Pennsylvanian, since that colony’s leadership was especially divided and hesitant in 1775. In fact, many Americans in the other colonies had not yet lost hope of reconciliation with Britain.

It was actually left to a former English artisan and twice-dismissed excise officer named Thomas Paine, who had only recently arrived in the colonies, to voice openly and unequivocally the hitherto often unspoken desire to be done with Britain once and for all. In his pamphlet Common Sense, published anonymously in January 1776, Paine dismissed George III as the “Royal Brute” and called for immediate American independence. When this radical pamphlet appeared anonymously, Franklin’s reputation for being an eager and passionate advocate for immediate separation from Britain was so well-known that some people attributed it to Franklin.7

No doubt some of Franklin’s displays of anger and antagonism toward Britain were calculated. There were many Americans in 1775 suspicious of Franklin’s dedication to the American cause, and he needed to overcome these suspicions. As early as 1771 Arthur Lee, a member of the well-known Lee family of Virginia, had written to Samuel Adams that Franklin was a “false” friend and should not be counted on to be a faithful agent of the Massachusetts assembly. Franklin, said Lee, who was in London at the time, was a crown officeholder whose son was royal governor of New Jersey. He had come to London to convert Pennsylvania into a royal province, which necessarily had made him something of a courtier. All these circumstances, “joined with the temporising conduct he has always held in American affairs,” meant, Lee concluded, that in any contest between British oppression and a free people Franklin could not be trusted to support America. Lee, whom Franklin would tangle with later in Paris, possessed an innately suspicious mind, and on top of that he was jealous of Franklin. Not only did he and his powerful Virginia family have land claims in the West that rivaled those of the Franklins, but he also wanted the Massachusetts agency for himself. He even offered to serve as agent without pay rather than have the American cause betrayed.8

The Massachusetts legislature did not accept Lee’s charges, but Lee’s suspicions of Franklin did not go away. He passed them on to his Virginia family, including his brother Richard Henry Lee, who became very influential in the Second Continental Congress. Samuel Adams and some other patriots still thought that Franklin had “a suspicious doubtful character,” and wrote to people who knew something of Franklin and asked about his political leanings.9 Shortly after the Congress convened, William Bradford, son of Franklin’s old printing rival and publisher of the Pennsylvania Journal, wrote his Virginia friend James Madison of the doubts some of the delegates had of Franklin’s patriotism, largely, it seems, because of rumors spread by Richard Henry Lee. “They begin to entertain a great Suspicion that Dr. Franklin came rather as a spy than as a friend,” said Bradford, “& that he means to discover our weak side & make his peace with the minister by discovering it to him.”

Madison had no way of knowing the truth of all the rumors that were floating about, “but the times are so remarkable for strange events,” he thought, “that their improbability is almost become an argument for their truth.” Even though he was hundreds of miles from Philadelphia, he was pretty certain about Franklin. “Indeed,” said Madison, “it appears to me that the bare suspicion of his guilt amounts very nearly to a proof of its reality. If he were the man he formerly was, & has even of late pretended to be, his conduct in Philada. on this critical occasion could have left no room for surmise or distrust. He certainly would have been both a faithful informer & an active member of the Congress. His behaviour would have been explicit & his Zeal warm and conspicuous.”10 That this especially clever and sagacious future framer of the Constitution could think this way tells us a great deal about the atmosphere at the time.

Franklin’s need to counter these rumors and suspicions that he was less than a patriot and maybe even a spy explains some of his Revolutionary fervor. It explains his decision to donate his entire salary as postmaster general to the assistance of disabled soldiers. He did this, he told his friend Strahan, so “that I might not have, or be suspected to have the least interested Motive for keeping the Breach [between Britain and America] open.”11 He knew that many Americans were thinking as Madison was, and he realized that he would have to make his patriotic zeal as “warm and conspicuous” as possible.

Over forty years earlier Franklin had reflected on why converts to a belief tended to be more zealous than those bred up in it. Converts, he noted in 1732, were either sincere or not sincere; that is, they changed positions either because they truly believed or because of interest. If the convert was sincere, he would necessarily consider how much ill will he would engender from those he abandoned and how much suspicion he would incite among those he was to go among. Given these considerations, he would never convert unless he were a true believer. “Therefore [he] must be zealous if he does declare.” On the other hand, “if he is not sincere, He is oblig’d at least to put on an Appearance of great Zeal, to convince the better, his New Friends that he is heartily in earnest, for his old ones he knows dislike him. And as few Acts of Zeal will be more taken Notice of than such as are done against the Party he has left, he is inclin’d to injure or malign them, because he knows they contemn and despise him.”12

Some such thinking as this explains the bizarre letter Franklin wrote on July 5, 1775, to his lifelong English friend William Strahan.

Mr. Strahan,

You are a Member of Parliament and one of that Majority which has doomed my Country to Destruction. You have begun to burn our Towns, and murder our People. Look upon your Hands! They are stained with the Blood of your Relations! You and I were long Friends: You are now my Enemy, and I am, Yours,

B. Franklin

Of course, he never sent this outrageous letter, the like of which he never wrote to any of his other British friends and correspondents. He wrote to Strahan, one of his oldest English friends, for local effect only. Since he was trying to convince his fellow Americans of his patriotism, he let people in Philadelphia see the letter, and then quietly laid it away.13 Within days he was writing his usual warm letters to Strahan.

But his fake letter to Strahan and his other displays of patriotism were effective. Bradford was soon writing Madison that the suspicions against Franklin had died away. “Whatever was his design at coming over here,” Bradford wrote on July 18, 1775, “I believe he has now chosen his side, and favors our cause.” Franklin had made his zeal for the cause very conspicuous indeed.14

A VERY PERSONAL AFFAIR

Some of Franklin’s anger and passion against British officialdom may have been calculated, but not all by any means. The Revolution was a very personal matter for Franklin, more personal perhaps than it was for any other Revolutionary leader. Because of the pride he took in his reasonableness and in his ability to control his passions, his deep anger at the British government becomes all the more remarkable, but ultimately understandable. Franklin had invested much more of himself in the British Empire than the other patriot leaders. He had had all his hopes of becoming an important player in that empire thwarted by the officials of the British government, and he had been personally humiliated by them as none of the other patriots had been. Although he kept telling his correspondents that he made “it a Rule not to mix personal Resentments with Public Business,” there is little doubt that his participation in the Revolution was an unusually private affair.15

Because he had identified himself so closely with the empire, he took every attack by the British government on the American part of that empire as a personal affront. He was hurt and bitter over the way the British ministers had treated him. He blamed them for prosecuting him “with a frivolous Chancery suit” in the name of William Whately over his role in the affair of the Hutchinson letters, a suit that his lawyer told him would certainly lead to his imprisonment if he appeared again in England. He believed that Britain’s bombardment of Falmouth (Portland), Maine, and its apparent intention to do the same to America’s other coastal towns were designed to hurt him personally; for “my American Property,” he reminded his English friends, “consists chiefly of Houses in our Seaport Towns.”16

Although legally he was still a member of the British Empire in 1775, emotionally he was not. He was way out ahead of many of his countrymen in his belief in the certainty of independence. And he had left his English friends even farther behind. Although his English friends kept imploring him to work out some kind of reconciliation, he now knew that all such efforts were futile. Of course, he continued to write warm and tender letters to Britain, yet he jarringly juxtaposed statements of affection toward his correspondents with severe criticisms of the nation of which they were a part. He began a letter to John Sargent, his banker in London, with accounts of the ways “your Ministry” had begun to burn “our Seaport Towns”; but he ended the letter with “My Love to Mrs. Sargent and your Sons . . . [and] with sincere Esteem, and the most grateful Sense of your long continu’d Friendship.” For all his English friends it was now “your Nation,” “your Ministers,” and “your Ships of War” and for his fellow Americans and himself “our Seaport Towns,” “our Sea Coast,” and “our Liberties.”17

One senses the mixed feelings he had in writing to some of his best friends about the impossibility of reconciliation. He was sad and angry at the same time, with the anger being more palpable. He saw clearly, as he said to one of his British friends in October 1775, that Britain and America were “on the high road to mutual enmity, hatred, and detestation,” and that “separation will of course be inevitable.” He had loved the empire as few Americans had. He had always thought that the fast-growing population of America meant “the Foundations of the future Grandeur and Stability of the British Empire [would] lie in America,” but he had never doubted that the empire would remain British. Now that was no longer the case. And he could not help reminding his British friends what the mother country was losing. Although “the greatest Political Structure Human Wisdom ever yet erected” was being destroyed by the stupidity of a few ministers, the most important part of that empire, America, he told his English friend and member of Parliament David Hartley, “will not be destroyed: God will protect and prosper it: You will only exclude yourselves from any share in it.”18

Since he had been personally rejected by English officialdom, he could no longer view England as the center of all civilization and virtue. Everything was now reversed. The Americans had become “a new virtuous People, who have Publick Spirit,” while the English were “an old corrupt one, who have not so much as an Idea that such a thing exists in Nature.” He was especially impressed by the devotion his fellow delegates gave to the work of the Continental Congress. Unlike the members of Parliament, the congressional delegates “attend closely without being bribed to it, by either Salary, Place or Pension, or the hopes of any.” Everywhere ordinary people were “busily employed in learning the Use of Arms. . . . The Unanimity is amazing.”19

He could scarcely believe that his formerly beloved England was waging such a ferocious war against America. In one of his most passionate exaggerations, he told his friend Jonathan Shipley that General Gage caused more destruction to Charlestown, Massachusetts, in one day than “the Indian Savages” had caused in all our wars, “from our first settlement in America, to the present time.” Dr. Johnson (who was nothing but “a Court Pensioner”) infuriated him by urging that English officials seek to excite the slaves to cut their masters’ throats and to hire the Indians to fight the Americans. “When I consider that all this Mischief is done my Country, by Englishmen and Protestant Christians, of a Nation among whom I have so many personal Friends,” he told Shipley, “I am ashamed to feel any Consolation in a prospect of Revenge.” Ashamed or not, he very much wanted revenge.

“You see I am warm,” he said, but he could not help it. Although he possessed “a Temper naturally cool and phlegmatic,” he was only responding to the temper of his fellow Americans, “which is now little short of Madness.”20 Years later, even as the peace negotiations with Britain were taking place in 1782, Franklin circulated a fictitious document describing a package sent by a Seneca Indian chief to the governor of Canada listing all the American men, women, and children his tribesmen had killed on behalf of the English. The list, together with hundreds of scalps, was to be sent to King George for his refreshment. Franklin saw nothing wrong with his hoax: “The Form may perhaps not be genuine,” he told a French friend, “but the Substance is truth.”21

Just how personal the Revolution was for Franklin is vividly revealed in his treatment of his son. Up to now Franklin and William had had the closest possible relationship. They had been partners in Franklin’s electrical experiments; in fact, William had been the only person Franklin had involved in his famous kite experiment. William had shared his father’s dreams for the British Empire and his hopes of a fortune in western land speculation. He had accompanied him to Albany in 1754 and had collaborated with him during the Seven Years War. He traveled with his father to London in 1757. They had journeyed to his father’s ancestral homes at Ecton and Banbury and collected genealogical information together. And like his father, William had become a royal officeholder and a keen supporter of royal authority. When they weren’t together, the father and son had kept constantly in touch and had looked after each other’s family. Few eighteenth-century fathers and sons had ever been closer or more intimate with one another.

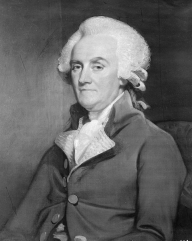

William Franklin, by Mather Brown, c. 1790

Now all this intimacy came to an end. Several days after Franklin had his office of deputy postmaster taken from him, he urged his son to give up his office as royal governor and retire to his farm. “ ’Tis an honester and a more honourable because a more independent Employment.” With barely concealed anger he told William that he would “hear from others the Treatment I have receiv’d.” Although he left William to his “own Reflections and Determinations upon it,” it was clear from a subsequent letter that he expected his son to give up his crown office in support of his father. Shortly after his return to America in 1775 Franklin met with William at the home of Joseph Galloway, who had just resigned from politics in disgust with the patriot direction of affairs. Franklin was surprised to discover that his old friend and close confidant Galloway was such a committed royalist, but it was he, not Galloway, who had changed. Franklin tried to persuade both Galloway and his son to join him in the patriot cause. When they refused, Franklin sought to cut his communications with both of them to the barest minimum. He gave up completely on William, but he kept trying with Galloway; as late as the fall of 1776 he assumed that Galloway would at least remain neutral in the conflict. As royal governor of New Jersey, William had no opportunity to remain neutral. The two times Franklin met his son again in the summer of 1775 ended in shouting matches loud enough to disturb the neighbors.22

Franklin was naturally embarrassed by the fact that his son was royal governor of New Jersey—indeed, by 1776 the only royal governor still in office in America—but his anger at his son went beyond his need to display his own American patriotism. When Governor Franklin was arrested in June 1776 and sent as a prisoner to Connecticut, Franklin said and did nothing, unaffected even by a poignant plea for help from William’s wife. After William violated his parole and made contact with the British commanders in New York, General William Howe and his brother, Admiral Lord Richard Howe, George Washington had him placed in solitary confinement in Litchfield, Connecticut, and deprived him of all writing materials. Even the pleadings of Strahan could not move Franklin to ease the conditions of his son’s confinement. “Whatever his Demerits may be in the Opinion of the reigning Powers in America,” Strahan told Franklin in 1778, “the Son of Dr. Franklin ought not to receive such Usage from them.”23 Franklin refused to lift a finger to aid his son, but others did, including Franklin’s son-in-law, Richard Bache. Eventually Congress arranged for William’s exchange, and William became a fervent loyalist leader in New York.

Because rumors abounded during the Revolutionary War that Franklin and his son were actually in collusion, Franklin perhaps had some reason to avoid all contact with his loyalist son. But after the peace treaty recognizing American independence was signed in September 1783, the situation was different and William wrote his father requesting reconciliation. Franklin’s reply was cool, to say the least. While he suggested that reconciliation might be possible, he wanted William to know how personal the Revolution had been to him. “Indeed,” he said, “nothing has ever hurt me so much and affected me with such keen Sensations, as to find my self deserted in my old Age by my only Son; and not only deserted, but to find him taking up Arms against me, in a Cause wherein my good Fame, fortune and Life were all at Stake.” Although Franklin acknowledged William’s claim that duty to king and country accounted for his loyalism, he really wasn’t persuaded. “There are,” he emphasized, “Natural Duties which precede political Ones, and cannot be extinguished by them.”24

In July 1785 the father and son met for several days in Southampton, England, but Franklin, anxious to protect William’s son Temple from any taint of loyalism, was in no mood for reconciliation. All he wanted was for William to sell him all his unconfiscated property in New Jersey, which would then be passed on to Temple. Franklin was all business, and he bargained hard to get the property at a price far below its current value. He also demanded that William cede to him some property in New York as compensation for a debt of £1500 that William owed him. That was the end of the matter. He never communicated with William again and indeed rarely ever mentioned him and then only coldly. In his will he left his son some worthless lands in Nova Scotia and some books and papers that William already possessed—in effect, nothing. “The part he acted against me in the late war, which is of public Notoriety,” he wrote in his will, “will account for my leaving him no more of an Estate he endeavored to deprive me of.”25

During the peace negotiations with Britain in 1782, Franklin was passionate and implacable on only one issue—that of compensation for the loyalists. If the loyalists were to be indemnified for their losses, he said, then the patriots had to be similarly compensated for all the lootings, burnings, and scalpings carried out by the British and their Indian allies. Even his two colleagues during the peace negotiations, John Adams and John Jay, were surprised at the intensity of Franklin’s bitterness toward the loyalists. It was far greater than their own.26

THE PASSIONATE REVOLUTIONARY

Franklin identified the American cause as his own, and he spared no energy on its behalf, even though he was the oldest member of the Second Continental Congress. In October 1775 as a member of a committee to investigate the military needs of the army, he traveled from Philadelphia to Cambridge to meet with George Washington, who had been appointed commander in chief. In March 1776, at the age of seventy, Franklin and several other commissioners trekked up the Hudson Valley to Canada in a fruitless effort to bring the Canadians in on the American side. No sooner had he finished serving on the committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence than he became president of the Pennsylvania convention called to write a new constitution for the state. Through the summer of 1776 he alternated his time between the Pennsylvania convention and the Congress. His most important contribution to the new state constitution was his urging the creation of a plural executive and a single-house legislature, which to many smacked of simple democracy and popular radicalism. One article of the constitution he specifically claimed. It expressed a view of government that his witnessing corrupt English politicians seeking lucrative royal offices had taught him. The article declared that there was no need in the government for “offices of profit, the usual effects of which are dependence and servility unbecoming freemen, in the possessors and expectants; faction, contention, corruption, and disorder among the people.”27

Although as a colony Pennsylvania had possessed only a single-house legislature, a government with a plural executive and a unicameral legislature was such an anomaly among all the other Revolutionary state constitutions created in 1776, nearly all of which had single governors and senates as well as houses of representatives, that it turned the radical Pennsylvania constitution into an object of heated controversy over the succeeding decade. It was “intolerable,” a monster “singular in its kind, confused, inconsistent, deficient in sense and grammar, and the ridicule of all America but ourselves, who blush too much to laugh.” Benjamin Rush thought the Pennsylvania convention must have been drunk with liberty to have produced such an “absurd” constitution, which, he said, “substituted a mob government to one of the happiest governments in the world.” But the charge that was most often hurled at the Pennsylvania constitution was that it was “an execrable democracy—a Beast without a head.”28 For most Americans in 1776 to be a simple democracy was not a good thing, which is why nearly all the state constitutions formed at the time created governors and senates to offset the democracy embodied in their houses of representatives.

Democracy in the eighteenth century was not yet the article of faith that it would become in the decades following the American Revolution. It was still a technical term of political science, meaning simply rule by the people. In traditional political thinking going back to the ancient Greeks, rule by the people alone was never highly regarded, for it could easily slip into anarchy and a takeover by a tyrant. The best constitution was one that was mixed or balanced, where the people’s rule was offset by the rule of the aristocracy and monarchy. Eighteenth-century intellectuals admired the English constitution so much because it seemed to have nicely mixed and balanced the three simple forms of government, monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, in the Crown, House of Lords, and House of Commons.

Of course, Americans in 1776 thought that the Crown had used money and influence to buy up the House of Commons and had corrupted the English constitution. They meant to prevent that corruption in their own new republican state constitutions. But most American constitution makers did not intend to abandon the idea of mixed and balanced government. John Adams, whose writings probably had the greatest influence on constitution-making in most of the states, but certainly not Pennsylvania, put the conventional wisdom best: “Liberty,” he said, “depends upon an exact Ballance, a nice Counterpoise of all the Powers of the state. . . . The best Governments of the World have been mixed.”29

Perhaps as much as anything it was Franklin’s identification with the simple, unmixed democratic constitution of Pennsylvania that sowed the seeds of John Adams’s growing enmity toward Franklin. Franklin’s later identification with France only made matters worse. When French intellectuals saw in the bicameral legislatures of the other constitutions an effort to retain an aristocratic social order in the senates, they were astonished. They asked how “the same equilibrium of powers which has been necessary to balance the enormous preponderance of royalty, could be of any use in republics, formed upon the equality of all the citizens.” For the French philosophes a state could have but a single interest. In fact, they said, that was what republicanism was all about. Believing as they did that “the representatives of a single nation naturally form a single body” and that there was no place for senates in the new egalitarian republics of the United States, the French philosophes celebrated the Pennsylvania Constitution as the only one that had refused to imitate the English House of Lords. John Adams, of course, reacted angrily to this French criticism and insisted all the more strenuously on the need for a mixed government with a single governor and a two-house legislature. Indeed, his magnum opus, the sprawling three-volume Defence of the Constitutions of the United States, was written in the white heat of his fury with this French, criticism of America’s balanced state constitutions. In his anger with the French, Adams never forgot that Franklin had favored a simple unbalanced government with a unicameral legislature. This is what gave Franklin his reputation for being a “democrat,” which for most eighteenth-century Americans remained a disparaging term.30

REBUFFING BRITISH PEACE OFFERINGS

Franklin had to interrupt his constitution-making in 1776 to deal with a peace offering brought by the British commanders, General William Howe and Admiral Lord Richard Howe. Lord Howe had been a friend of Franklin in England, and he wrote Franklin an amicable letter in July 1776 in hopes of finding the means of reconciling America and Great Britain. With the authorization of Congress, Franklin responded in the most passionate and blunt terms. It was impossible, he told Howe, that Americans would think of submission to a government that had carried on an unjust and unwise war against them “with the most wanton Barbarity and Cruelty.” He knew only too well the “abounding Pride and deficient Wisdom” of the former mother country. Britain could never see her own true interests, for she was blinded by “her Fondness for Conquest as a Warlike Nation, her Lust of Dominion as an Ambitious one, and her Thirst for a gainful Monopoly as a Commercial one.”

Even in this quasi-official dispatch, Franklin could not help thinking of the breakdown of the empire in personal terms. He recalled that only a year and a half earlier, at Howe’s sister’s house in London, Lord Howe had given him expectations that reconciliation between Britain and her colonies might soon take place. Not only did Franklin have “the Misfortune to find those Expectations disappointed,” but he was soon “treated as the Cause of the Mischief I was labouring to prevent.” Franklin’s only “Consolation under that groundless and malevolent Treatment” was that he had “retained the Friendship of many Wise and Good Men in that Country.” His advice to Lord Howe was to resign his command and “return to a more honourable private Station.” Franklin’s angry letter shocked Howe. This was a very different Franklin from the one Howe had known eighteen months earlier in London.31

Thinking the Americans might be more open to a reconciliation following their defeat in the battle of Long Island in August 1776, Lord Howe tried once again. He asked the Continental Congress for some of its members to meet with him in a private conference on September 11. The Congress selected Franklin, John Adams, and Edward Rutledge to attend the meeting under a flag of truce. It was a loaded committee, since all three had signed the Declaration of Independence and were unlikely to retract that momentous decision. Franklin proposed that the committee meet Howe either at the New Jersey governor’s mansion at Perth Amboy, from which William had been forcibly removed as a prisoner of the patriots (a curious suggestion), or at Staten Island, which was occupied by British forces. Howe chose the latter.

On the way from Philadelphia to the meeting, the committee found the roads and inns crowded with troops and stragglers fleeing from the British forces in New York. In New Brunswick, Franklin and Adams were forced to share a room with a tiny window and a bed not much smaller than the room. This famous incident, recounted by Adams in his diary many years later, was one of Adams’s more benign memories of Franklin. The account reveals Adams’s talent as a storyteller, which under other circumstances might have made him a superb novelist.

Adams, who was just recovering from an illness, feared the night air blowing on him and shut the window. “Oh!” said Franklin, “Dont shut the window. We shall be suffocated.”

Adams answered that he was afraid of the evening air.

“The Air within this Chamber will soon be, and indeed is now worse than that without Doors,” replied Franklin. “Come! Open the Window and come to bed, and I will convince you: I believe you are not acquainted with my Theory of Colds.”

Adams opened the window and leaped into bed. He told Franklin that he had read his theory that no one ever got a cold going into a church or any other cold place. But “the Theory was so little consistent with my experience,” he said, “that I thought it a Paradox.” Adams was willing, however, to have it explained. “The Doctor then began a harangue, upon Air and cold and Respiration and Perspiration, with which I was so much amused that I soon fell asleep.”

Having the last laugh, Adams went on to point out that Franklin’s theory of colds ultimately did him in. “By sitting for some hours at a Window, with the cool Air blowing upon him,” in 1790 the eighty-four-year-old Franklin had “caught the violent Cold, which finally choaked him,” recalled Adams with more malice than he had expressed earlier in the story.32

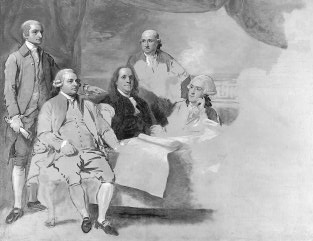

At the meeting with Howe, the admiral explained that he could not officially treat with Franklin, Adams, and Rutledge as a committee of Congress, but he could confer with them “merely as Gentlemen of great Ability, and Influence in the Country” on the means of restoring peace between Britain and the colonies. Franklin said that his lordship could regard the committee as he wished, but he and his colleagues knew only too well what they represented. This was not a very auspicious beginning, revealing as it did how much catching up to American opinion the British government still had to do. Howe went on to say that he could not admit the idea of the colonies’ independence “in the smallest degree.” He suggested that Britain and America might return to the situation prior to 1763. But the committee, with Franklin passionately and sometimes sneeringly in the lead, declared emphatically that it was too late. “Forces had been sent out, and Towns destroyed,” said Franklin. America had already declared its independence, he concluded, and “could not return again to the Domination of Great Britain.”33

THE MISSION TO FRANCE

That independence, however, still had to be won, and most Americans thought they would need help from abroad to achieve it. In several letters to English friends, Franklin suggested the possibility of America’s appealing to a foreign power for assistance. In November 1775 the Continental Congress had appointed Franklin to a Committee of Secret Correspondence, which was to seek foreign support for the war. In December, Franklin asked a European philosophe in the Netherlands to find out whether some European state might be willing to aid the Americans. At the same time France, the greatest of the continental powers, had sent an agent to America to see whether the rebels were worth supporting. On behalf of the Committee of Secret Correspondence, Franklin wrote Connecticut merchant Silas Deane in March 1776 to engage him in secretly approaching the French government in order to secure money and arms.

After the Declaration of Independence that July, America’s situation was clarified and its search for foreign aid could be more open. Congress now realized that a formal commission of delegates was needed in Paris if the United States was to persuade France to join the war as America’s ally. Unlike Adams and Jefferson, who declined to become one of the commissioners to be sent to France, Franklin had no hesitation in accepting and, in fact, may have pushed to get the appointment. In October, Congress appointed Franklin to join Deane and Arthur Lee of Virginia, who was still in London, as a three-man commission to obtain arms and an alliance. The choice of Franklin was obvious. He was an international celebrity who knew the world better than any other American.

Franklin seems to have yearned to get back to the other side of the Atlantic. Perhaps he felt he was the stranger in his own country that he predicted he might be. In a sketch written shortly after the meeting with Howe he outlined various conditions for peace that might be negotiated with Great Britain—including, of course, unconditional independence, but also Britain’s ceding to the United States for some sum of money all of Canada, the Floridas, Bermuda, and the Bahamas. One reason why such negotiations for peace with Britain were timely now, wrote Franklin, was that they might pressure the French into signing an alliance. But he added that such negotiations would also “furnish a pretence for BF’s going to England where he has many friends and acquaintance, particularly among the best writers and ablest speakers in both Houses of Parliament.” If the British balked at the terms of settlement, he wrote, then he was influential enough “to work up such a division of sentiments in the nation as greatly to weaken its exertions against the United States and lessen its credit in foreign countries.”34 Any excuse, it seemed, to get back across the Atlantic.

When people learned of Franklin’s planned mission to France, some were deeply suspicious of his motives. He was blamed once again for bringing about the Revolution, making people of the same empire “strangers and enemies of each other.” The British ambassador to France and many American loyalists thought that he was escaping America in order to avoid the inevitable collapse of the rebellion. Even his old friend Edmund Burke could not accept the news that Franklin was going on a mission to France. “I refuse to believe,” Burke wrote, “that he is going to conclude a long life which he brightened every hour it continued, with so foul and dishonorable [a] flight.”35 But Franklin was not fleeing America out of any fears for the success of the Revolution; he merely wanted to return to the Old World, where he felt more at home.

On October 26, 1776, Franklin sailed with his two grandsons, sixteen-year-old Temple, William’s illegitimate son, and seven-year-old Benjamin Franklin Bache, Sally’s boy. They arrived in France in December—after a bold and risky voyage, for, as Lord Rockingham noted, Franklin might have been captured at sea and “once more brought before an implacable tribunal.”36 That he took the voyage says a great deal about Franklin’s anger and his determination to defeat the British. It also says a great deal about his desire to experience once again the larger European world, where he had spent so much of his adult life. It would be nearly nine years before he returned to the United States.

Even before he reached France, Franklin was emotionally prepared for his new role as America’s representative to the world. Back in 1757, Thomas Penn had predicted that the highest levels of English politics would eventually be closed to Franklin. Whatever Franklin’s scientific reputation meant to the intellectual members of the Royal Society or the Club of Honest Whigs, Penn said, it would count for very little in the eyes of the ruling aristocracy, the “great People” who actually exercised political power.37 As Franklin himself came to this realization by the early 1770s, he began to see the English stage on which he had been operating as more and more limited. Suddenly his reputation “in foreign courts” as a kind of ambassador of America seemed to compensate for his loss of influence in England.

During his last years in London he proudly told his son that “learned and ingenious foreigners that come to England, almost all make a point of visiting me, for my reputation is still higher abroad than here.” He pointed out that “several of the foreign ambassadors have assiduously cultivated my acquaintance, treating me as one of their corps.” Some of them wanted to learn something about America, mainly out of the hope that troubles with the American colonies might diminish some of Britain’s “alarming power.” Others merely desired to introduce Franklin to their fellow countrymen. Whatever the reasons for his extraordinary international reputation as the representative American, Franklin was well aware of it and was prepared to use it to help America.38

THE SYMBOLIC AMERICAN

In 1776 Franklin was the most potent weapon the United States possessed in its struggle with the greatest power on earth. Lord Rockingham observed at the time that the British ministers would publicly play down Franklin’s mission to France, but “inwardly they will tremble at it.”39 The British government had good reason to tremble. Franklin was eventually able not only to bring the French monarchy into the war against Britain on behalf of the new republic of the United States but also to sustain the alliance for almost a half-dozen years. Without his presence in Paris throughout that tumultuous time, the French would never have been as supportive of the American Revolution as they were. And without that French support, the War for Independence might never have been won.

The French knew about Franklin well before he arrived in 1776. The great French naturalist Comte de Buffon read his Experiments and Observations on Electricity in 1751 and urged a translation. The next year King Louis XV endorsed the publication of a translated edition of Franklin’s work and personally congratulated the author. In the years that followed, Franklin received letter after letter from French admirers of his electrical experiments. One of these admirers, Dr. Jacques Barbeu-Dubourg, began exchanging writings with Franklin. He translated many of Franklin’s essays and works, including his testimony before the House of Commons in 1766, and had them reprinted in the French monthly Ephémérides du citoyen. Readers of the journal were told that from Franklin’s statements “they will see what constitutes the superiority of intelligence, the presence of mind and the nobility of character of this illustrious philosopher, appearing before an assembly of legislators.”40 His testimony in the House of Commons was eventually published in five separate French editions.

In 1767 and again in 1769 Franklin visited France, was presented to the king, and dined with the royal family. He was especially impressed with the politeness and urbanity of the French and, as he wrote in a playful letter to Polly Stevenson, he had started to become French himself. “I had not been here Six Days before my Taylor and Peruquier had transform’d me into a Frenchman. Only think what a Figure I make in a little Bag Wig and naked Ears! They told me I was become 20 Years younger, and look’d very galante; so being in Paris where the Mode is to be sacredly follow’d, I was once very near making Love to my Friend’s Wife.”41

During his visits to France, Franklin made many friends among French intellectuals. Dubourg described him in print as “one of the greatest and the most enlightened and the noblest men the new world had seen born and the old world has ever admired.”42 In 1772 Franklin was elected a foreign associate to the French Royal Academy of Science, one of only eight foreigners so honored. The next year Dubourg published two volumes of the Oeuvres de M. Franklin, prefixed with a print of Franklin that made him look like a Frenchman, together with the line “He stole the fire of the Heavens and caused the arts to flourish in savage climes.”43 In the preface Dubourg further sharpened the image of the backwoods philosopher emerging from the land of the peaceful Quakers.

The French, of course, already had an image of America as the land of plain Quakers. Voltaire in his Lettres philosophiques (1734) had identified Pennsylvania with the Society of Friends, who were celebrated for their equality, pacifism, religious freedom, and, naturally, their absence of priests. It was as if nobody but Quakers lived in Pennsylvania. With three articles on Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and the Quakers, Diderot’s Encyclopédie further contributed to this picture of Pennsylvania as the land of freedom, simplicity, and benevolence—an image that gradually was expanded to the New World in general.44

Franklin as a Frenchman, engraving by François Martinet, 1773

Many of the French philosophes like Voltaire were struggling to reform the ancien régime, and they turned the New World into a weapon in their struggle. America in their eyes came to stand for all that eighteenth-century France lacked—natural simplicity, social equality, religious freedom, and rustic enlightenment. Not that the reformers expected France to become like America. But they wanted to contrast this romantic image of the New World with the aristocratic corruption, priestly tyranny, and luxurious materialism they saw in the ancien régime. A popular debate that arose in France—over the issue of whether the climate of the New World was harmful to all living creatures and caused them to degenerate—was fed by these political concerns.45 With this issue in mind, many of the liberal reformers were eager to emphasize the positive qualities of America. Idealizing all that was different from the luxury and corruption they saw around them, many of the liberal French philosophes created “a Mirage in the West,” a countercultural image of America with which to criticize their own society.

In addition to the philosophes, many French aristocrats were themselves critics of their society, involved in what today we might call “radical chic.” They were eager to celebrate the new enlightened values of the eighteenth century, many of which were drawn from the classical republican writings of the ancient world. French nobles invoked classical antiquity and especially republican Rome to create imagined alternatives to the decadence of the ancien régime. Of course, they did not appreciate the explosive nature of the materials they were playing with. They sang songs in praise of liberty and republicanism, praised the spartan simplicity of the ancients, and extolled the republican equality of antiquity—all without any intention of actually destroying the monarchy on which their status as aristocrats depended. The French nobles applauded Beaumarchais’s Le Barbier de Séville and Le Mariage de Figaro, and later Mozart’s operatic version, Le Nozze di Figaro, with their celebration of egalitarian and anti-aristocratic values, without any sense they were contributing to their own demise. They flocked to Paris salons to ooh and aah over republican paintings such as Jacques-Louis David’s severe classical work The Oath of the Horatii, without foreseeing that they were eroding the values that made monarchy and their dominance possible. Many of these French aristocrats, such as the Duc de La Rochefoucauld, a friend and admirer of Franklin, were passionate advocates of abolishing the very privileges to which they owed their positions and fortunes. They had no idea where all their radical chic would lead. In 1792 La Rochefoucauld was stoned to death by a frenzied revolutionary mob.46

Franklin was part of this radical chic from the beginning. The French aristocrats were prepared for Franklin, and they contributed greatly to the process of his Americanization. They helped to create Franklin the symbolic American. In this sense Franklin as the representative American belonged to France before he belonged to America itself. Because the French had a need of the symbol before the Americans did, they first began to create the images of Franklin that we today are familiar with—the Poor Richard moralist, the symbol of rustic democracy, and the simple backwoods philosopher.

The Oath of the Horatii,

by Jacques-Louis David, 1785

He was the celebrated Dr. Franklin from the moment of his arrival in France in 1776. He was invited by a wealthy merchant, Jacques Donatien Le Ray, the Comte de Chaumont, to live in the garden pavilion of his elegant Hôtel de Valentinois located on his spacious estate in Passy, a small village outside of Paris on the route to Versailles. Unlike Franklin’s London home, which had been in the midst of the crowds and bustle of the city, this house was a half mile from Paris, sitting on a bluff with terraces leading down to the Seine, with views overlooking the city. Franklin enjoyed this suburban existence; when pressed by his colleagues to move into Paris in order to save money, he refused. Chaumont was a government contractor. As an enthusiastic partisan of the United States, he refused any rent from Franklin, at least at first, and saw to it that the great man lived in relative luxury, serviced by a liveried staff of a half-dozen or more servants. In addition to the large formal gardens in which Franklin enjoyed walking, Franklin’s house had a lightning rod on the roof and a printing press in the basement. He spent his entire time in France quite comfortably ensconced in these plush surroundings. His food was ample and his wine cellar was well stocked with over a thousand bottles. He needed all these supplies, for he had a steady stream of guests.

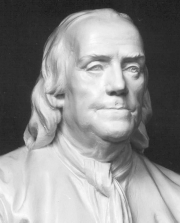

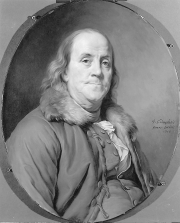

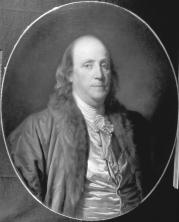

LEFT: Franklin, engraving by Augustin de Saint-Aubin, 1777, after a drawing by Charles-Nicholas Cochin

RIGHT: To the Genius of Franklin,etching by Marguerite Gérard, after a design by Jean-Honoré Fragonard, 1778

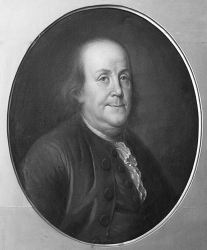

LEFT: Franklin, porcelain medallion, Sèvres ware, 1778

RIGHT: Franklin, French school, c. 1783

The great man is “much sought after and entertained,” noted an observer, “not only by his learned colleagues, but by everyone who can gain access to him.” The nobility lionized him. They addressed him simply as “Doctor Franklin, as one would have addressed Plato or Socrates.”47 The French placed crowns upon his head at ceremonial occasions, wrote poems in his honor, and did their hair à la Franklin. Wherever he traveled in his carriage, crowds gathered and, amid acclamations, gave way to him in the most respectful manner, “an honour,” noted Silas Deane, “seldom paid to the first princes of the blood.” Only three weeks after his arrival, it was already the mode of the day, said another commentator, “for everyone to have an engraving of M. Franklin over the mantelpiece.”48 Indeed, the number of Franklin images that were produced is astonishing. His face appeared everywhere—on statues and prints and on medallions, snuffboxes, candy boxes, rings, clocks, vases, dishes, handkerchiefs, and pocketknives. Franklin told his daughter that the “incredible” numbers of images spread everywhere “have made your father’s face as well known as that of the moon.”49

Not only did Jean-Antoine Houdon and Jean-Jacques Caffiéri mold busts of Franklin, in marble, bronze, and plaster, but every artist, it seemed, wanted to do his portrait. Jean-Baptiste Greuze and J. F. de L’Hospital painted him, and Joseph-Siffred Duplessis did at least a dozen portraits of him (see pages ref). The Duplessis portrait of 1778 portrayed Franklin in a fur collar and was repeatedly engraved and copied by numerous other artists; it became the most widely recognizable image of Franklin.50 “I have at the request of friends,” Franklin complained, “sat so much and so often to painters and Statuaries, that I am perfectly sick of it.”51 No man before Franklin, it has been suggested, ever had his likeness reproduced at one time in so many different forms.52 Apparently King Louis XVI became so irritated with Franklin’s image everywhere that he presented one of Franklin’s admirers in his court with a porcelain chamber pot with the American hero’s face adorning the bottom.53

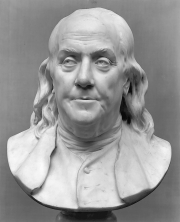

LEFT: Franklin, bust by Jean-Jacques Caffiéri, 1777

RIGHT: Franklin, bust by Jean-Antoine Houdon, 1778

LEFT: Franklin, by Joseph-Siffred Duplessis, 1778

RIGHT: Franklin, by Jean-Baptiste Greuze, 1777

Franklin, by J. F. de L’Hospital, 1778

To the French, Franklin personified not only republican America but the Enlightenment as well. As a Freemason, he was a member of that eighteenth-century international fraternity that transcended national boundaries. In 1777 he was made a member, and later grand master, of the Masonic Lodge of the Nine Sisters, the most eminent lodge in France. Although many monarchists were suspicious of Freemasonry and discouraged their friends from joining the order, the lodge nevertheless contained many distinguished artists and intellectuals. Franklin used his association with them to further the American cause. He suggested to a fellow lodge member, La Rochefoucauld, for example, that he translate the American state constitutions into French. When this was done, Franklin presented copies to every ambassador in Paris and spread copies throughout Europe.

Since he was the American Enlightenment personified, it was necessary that he meet his European counterpart—Voltaire. When Voltaire returned to France in 1778 after twenty-eight years in exile, he met with Franklin several times. The most public of these meetings took place at the Academy of Science in April 1778. Since both the old philosophes were at the meeting, the rest of those in attendance called for them to be introduced. But, according to John Adams, who witnessed the occasion, bowing to one another was not enough. Even after Franklin and Voltaire took each other’s hands, the crowd cried for more. They must embrace “à la francoise.” “The two Aged Actors upon this great Theater of Philosophy and frivolity,” recalled Adams sardonically, “then embraced each other by hugging one another in their Arms and kissing each other’s cheeks, and then the tumult subsided. And the Cry immediately spread through the whole Kingdom and I suppose over all Europe. . . . How charming it was! Oh! it was enchanting to see Solon and Sophocles embracing!”54

Franklin’s genius was to understand how the French saw him and to exploit that image on behalf of the American cause. Since Franklin was from Pennsylvania, people assumed he was a simple Quaker, and he played the part to perfection. He dressed plainly in white and brown linen, declared one observer, “glasses on his head, a fur cap, which he always wears on his head, no powder, but a neat appearance.” Instead of the short sword worn by most aristocrats, “he carries as his only defense a cane in his hand.”55 Franklin knew very well the political significance of what he was doing. After describing to an English friend his simple dress with his “thin grey strait Hair, that peeps out under my only Coiffure, a fine Fur Cap which comes down my Forehead almost to my Spectacles,” he remarked, “Think how this must appear among the Powder’d Heads of Paris.”56

In French eyes Franklin came to symbolize America as no single person in history ever has. He realized that he was “much respected, complimented and caress’d by the [French] People in general,” and that “some in Power” paid him a particular “Deference,” which, he said, was probably why his colleagues “cordially hated and detested” him so much.57 Indeed, it seemed he could do no wrong in France.

When Franklin was received by Louis XVI at Versailles, he violated almost every rule of this, the most ornate and ritual-bound court in all of Europe. While his American colleagues wore the elaborate court dress prescribed by the royal chamberlain, Franklin appeared in his simple rustic dress; and the French courtiers loved it. He could have been taken “for a big farmer,” said one observer, “so great was his contrast with the other diplomats, who were all powdered, in full dress, and splashed all over with gold and ribbons.”58 The French turned everything about Franklin into a sign of Quaker or republican simplicity. They fell over themselves in enthusiasm for this village philosopher. To his French admirers even Franklin’s deficiencies became great virtues. Was he quiet in large gatherings? This only demonstrated his republican reticence. Did he speak and write rather poor ungrammatical French? This only showed that he spoke and wrote from the heart.

Even when he fooled the best of the French intellectuals with one of his literary tricks, he was celebrated. No less a personage than the philosophe Abbé Raynal, for example, fell for Franklin’s famous Polly Baker hoax, which was first published in a London paper in 1747. In his account Franklin had Polly, a prostitute, defend herself in a speech before a court in Connecticut for giving birth to five successive illegitimate children. She was doing nothing more, she said, than her duty—“the Duty of the first and great Command of Nature, and of Nature’s God, Encrease and Multiply. A Duty, from the steady Performance of which, nothing has ever been able to deter me; but for its Sake, I have hazarded the Loss of the Publick Esteem, and frequently incurr’d Publick Disgrace and Punishment; and therefore ought, in my humble Opinion, instead of a Whipping, to have a Statue erected in my Memory.” According to Franklin, Polly’s speech so moved her judges that they dispensed with her punishment; it even “induced one of her Judges to marry her the next Day.”

Although Franklin may have been merely poking fun at the double standard for women, the story seems to have been widely taken as an authentic account of an event. It was kept alive by many subsequent reprintings in both America and Britain. No one was more bamboozled by “The Speech of Miss Polly Baker” than Abbé Raynal. Raynal picked it up from an English publication and, believing it to be a true story, inserted it in his immensely popular Histoire philosophique et politique des établissements et du commerce des Européens dans les deux Indes (1770). The ever earnest abbé thought the story was meant to show the puritanical severity of New England’s laws, which made it enormously appealing to all those enlightened French intellectuals eager to show their sympathy for the oppressed of the world. Only during Franklin’s mission in France did Raynal discover that the story was made up. Franklin told Raynal that as a young printer he had had the habit of creating “anecdotes and fables and fancies,” and that Polly Baker’s speech was one of those. Surprised, the abbé quickly recovered. “Oh, very well, Doctor, I had rather relate your stories than other men’s truths.”59

To the infatuated French all Franklin’s writings seemed praiseworthy. In 1777 his The Way to Wealth was translated as La Science du Bonhomme Richard, ou moyen facile de payer les impôts. It became the most widely read American work in France, going through four editions in two years and five others over the next two decades.60 Although Franklin viewed his work as a hodgepodge of borrowed proverbial wisdom, and sometimes satirized his own prudential advice, the French in their passion for Franklin described his Bonhomme Richard maxims as sublime philosophy worthy of Voltaire and Montaigne. Timeworn adages such as “One Today is worth two Tomorrows” and “Laziness travels so slowly, that Poverty soon overtakes him” were extolled as serious moral philosophy.61

Indeed, French excitement over the proverbs of Bonhomme Richard reveals some of what we might call the early beginnings of modern French structuralism and deconstruction. In his eulogy on Franklin’s death, the Marquis de Condorcet, the French philosophe and Masonic friend of Franklin, expressed a peculiar form of Gallic logic. Bonhomme Richard, said Condorcet, was a “unique work in which one cannot help recognizing the superior man without it being possible to cite a single passage where he allows his superiority to be perceived.” Condorcet, who died in prison during the French Revolution while writing about the perfectibility of mankind, declared that there was nothing in the thought or style of Franklin’s work that showed anything above “the least developed intelligence.” But, said Condorcet, in an argument worthy of Jacques Derrida, “a philosophic mind” could discover the “noble aims and profound intentions” behind the maxims and proverbs.62

Although The Way to Wealth may have been his best-selling work in France, Franklin was anything but a bourgeois businessman to the French. He understood the French aristocrats’ love of honor and liberality and, despite being a former artisan from the lowest rungs of the social ladder, he knew how to deal with them. He tried to tell the American foreign secretary Robert R. Livingston the way to approach the French. “This is really a generous Nation, fond of Glory and particularly that of protecting the Oppress’d.” The French nobility, “who always govern here,” was not really concerned with trade. To tell these French aristocrats that “their Commerce will be advantag’d by our Success, and that it is their Interest to help us, seems as much to say, Help us and we shall not be obliged to you.”63 Franklin knew better. The French foreign minister, the Comte de Vergennes, noted that all the Americans had “a terrible mania for commerce.” But not Franklin: “I believe,” said Vergennes, “his hands and heart are equally pure.”64

Although Franklin never liked snobbery, was always eager to defend obscure but honest men, and often ridiculed the idea of aristocracy and claims of blood, he was eager to share the French aristocracy’s contempt for commerce, which he generally equated with “Cheating.” Of course, by commerce he meant the kind of international trade that great wholesale merchants and nations engaged in; he did not generally mean the kind of buying and selling that he had done as a tradesman in Philadelphia. But he was no defender of rapacious moneymaking. His severest criticism of a nation was to say, as he did of Holland in 1781, that it had “no other Principles or Sentiments but those of a Shopkeeper.”65

Precisely because he had begun his career as a tradesman, he seems to have had a much greater need than the other Founders to show the world that he was truly genteel and “free from Avarice.” All these condemnations of commerce and shopkeepers suggest something of the emotional price Franklin paid for his remarkable rise. But they also reveal the peculiar way this former tradesman who had become the representative American endeared himself to the French.66

THE PROBLEMS OF THE MISSION

Symbol or no symbol, Franklin faced extraordinary difficulties and very unpromising circumstances in Paris, difficulties and circumstances that make the achievements of his mission all the more remarkable. In 1776 he seemingly had everything against him. The British immediately expressed dismay at his presence in France, and Louis XVI was not at all happy to have his monarchy encouraging republican rebels against another king. Queen Marie-Antoinette was especially opposed to aiding the Americans, and some members of the ministry agreed with her. Franklin and his fellow commissioners knew that their task was to bring France into the war on America’s side. But the French government did not believe itself ready yet for open war with England. As the commissioners reported in the spring of 1777, France wanted to avoid offering “an open Reception and Acknowledgement of us, or entering into any formal Negotiation with us, as Ministers from the Congress.”67 Indeed, out of fear of precipitating a premature war with Britain, France initially put all sorts of restrictions on American behavior, including preventing Americans from enlisting French officers and forbidding American privateers to sell captured prizes in French ports. The French were willing to open their ports to American commerce and to supply arms and money, however, as long as no one talked about it.

France’s hesitation was quite understandable. Ever since independence the Continental army had been in pell-mell retreat from the British forces, and the prospect of sustaining the Revolution seemed doubtful. Even in these difficult circumstances the United States was prepared to offer the French very little. The most the new republic would promise was that if French aid to the United States led France into war with Great Britain, America would not assist Britain in such a war.

Congress offered little guidance; indeed, Franklin and his colleagues essentially had to teach themselves diplomacy. With no word from Congress for months, the commissioners had no knowledge of what was going on in America. “Our total Ignorance of the truth or Falsehood of Facts, when Questions are asked of us concerning them,” they complained, “makes us appear small in the Eyes of the People here, and is prejudicial to our Negotiations.”68 Added to this confusion was the extraordinary number of solicitors the commissioners, especially Franklin, had to deal with. The esteemed doctor was overwhelmed with correspondents and visitors at the very time he was trying to win over the French while struggling with a foreign language and different social customs. His grasp of French was never strong. Once, at a public gathering where there were many speeches, Franklin had a hard time understanding what was being said; but he followed the lead of one of his lady friends and applauded when she did. Later his grandson told him that he had been applauding praises of himself, and more vigorously than anyone.69

Everybody interested in America, it seemed, wanted him for something or other—merchants and traders looking to make money from an American deal, inventors and savants seeking his blessing, and especially French and other European officers eager to be recommended for commissions in the American army. “These Applications,” he wrote to one of his French friends, “are my perpetual Torment. People will believe, notwithstanding my continually repeated Declarations to the Contrary, that I am sent hither to engage Officers. In Truth, I never had such Orders. . . . You can have no Conception how I am harass’d. All my Friends are sought out and teiz’d to teaze me; Great Officers of all Ranks in all Departments, Ladies great and small, besides profess’d Sollicitors, worry me from Morning to Night.”70

All this pestering would have taxed the energies of a young man, but Franklin by eighteenth-century standards was an old man, suffering from a variety of maladies—gout, painful bladder or kidney stones, a chronic skin disease, and swollen joints. He had gained weight and walked with more and more difficulty. The sea voyage had been especially difficult and, as he later recalled, had “almost demolish’d” him.71 Indeed, the French thought him much older than he was.

If these difficulties were not enough, the Paris in which Franklin was expected to operate was a hotbed of espionage and counterespionage. The most ingenious spy novelist could scarcely have invented the Parisian world of these years. Every nation had agents in Paris, even the Americans. In fact, at the outset the American commissioners themselves may well have been involved in secretly releasing information to the British. Before the French formally allied with the Americans, the situation was very complicated. The British were warning the French that they could not tolerate much longer France’s supplying arms to the American rebels. The commissioners thus had a vested interest in manipulating the information to be revealed to the British in order to precipitate a British declaration of war against France or, after war broke out, to influence British opinion against continuing the war against the Americans. It was all these attempts to manipulate information that led some people at the time and some subsequent historians to believe that Franklin was spying on behalf of the British.72

The British, however, had such an extensive network of spies in Paris keeping watch on Franklin, whom George III called “that insidious man,” that they may not have needed Franklin’s help as a spy.73 Franklin never suspected that Paul Wentworth, a wealthy émigré from New Hampshire, ran the British network and had several other Americans working for him. Nor did Franklin realize that the secretary of the American legation, Massachusetts-born Edward Bancroft, was also a spy in the pay of the English government.

In fact, not only did Franklin not suspect Bancroft, but he had great affection for him. Franklin had successfully sponsored Bancroft for membership in the Royal Society and had introduced him to many of his friends in London. Bancroft had been present in the Cockpit during Wedderburn’s diatribe against Franklin, and he had been one of the few defenders of Franklin in the London press during the affair of the Hutchinson letters—something that was bound to win Franklin’s heart. Even though some Americans suspected that Bancroft might be a spy, Franklin trusted him completely.

Bancroft was actually a double agent who sometimes spied on behalf of the American cause, but most of his spying was done for the English. He supplied Wentworth with regular reports on the American negotiations with France and Spain, the commissioners’ correspondence with Congress, the names of ships and captains employed by the commissioners, and news of sailings and prizes seized by privateers. Bancroft wrote his reports in invisible ink and dropped them off in a sealed bottle in the hollow of a tree on the south side of the Tuileries, where they were picked up every Tuesday evening at nine thirty.74

Despite being surrounded by spies, Franklin was not at all worried and, in fact, blithely dismissed the possibility of spies having any harmful effects on his mission. As long as he was involved “in no Affairs that I should blush to have made publick; and to do nothing but what Spies may see and welcome,” he could not care less about spies. “If I was sure . . . that my Valet de Place was a Spy, as probably he is, I think I should not discharge him for that, if in other Respects I lik’d him.”75 These facetious remarks that confused his own moral behavior with state affairs involving American lives and property reveal once again how much Franklin tended to see the Revolution in personal terms.76 He did have one fright, however, when he thought a spy had tried to poison him; he knew the Paris chief of police well enough to have the suspected culprit locked up in the Bastille.77

Not only did Franklin have to convince the French to support America, but he also had to persuade his countrymen to trust France, and that turned out to be much the harder task. As former Englishmen, Americans had always known France as England’s traditional enemy. Indeed, by the eighteenth century the English had come to define much of their national identity by their differences from the French, from the extent of their liberties and their consumption of beef to their religious views—especially their religious views. France was Roman Catholic, and to be English was to be Protestant. Although Americans were now fighting England, it would not be easy for them to shed their inherited English dislike of France and fear of Catholicism. Besides, they had just fought a long and costly war against the French and their Indian allies, and the memory of that war lingered. For Franklin to get his fellow Americans to trust the French as much as he came to trust them remained his greatest challenge throughout his nearly eight-year-long mission—one he was never entirely successful in meeting.

THE BURDEN OF HIS FELLOW COMMISSIONERS

The character of his two fellow commissioners, Deane and Lee, did not help matters any. Deane had been in Paris since the spring of 1776 seeking aid secretly from the French government. He had joined up with Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, a man of many talents who had strong connections to the French court. Between writing Le Barbier de Séville and Le Mariage de Figaro, Beaumarchais organized a fictitious trading company to act as a front for the French government’s supplying of arms to the Americans. Beaumarchais seems to have hoped to make money out of this gunrunning enterprise, but whether Deane hoped to is not clear; Deane’s accounts turned out to be such a mess that no one at the time or ever since has been able to untangle them. At any rate Beaumarchais lost a fortune in the business, and Deane was eventually accused of embezzlement and profiteering by his fellow commissioner Arthur Lee.

Lee was a very difficult man, a superpatriot mistrustful of everyone who did not think as he did, including his two fellow commissioners.78 He was unable to relate to the Comte de Vergennes, the French foreign minister, with whom the commission had to deal. Lee distrusted France and missed no opportunity to let Vergennes know how fortunate the French were in being able to help the Americans. France, of course, wanted revenge against Britain for its defeat in the Seven Years War, but there were other things France might have done besides going to war with Britain in support of America, including trying to recover its lost territory in North America.79 Lee never appreciated that, but Franklin did.

Because Franklin did get along with Vergennes and refrained from vigorously pressing him for an alliance, Lee assumed that Franklin had been taken in by the French or, worse, had shifted his allegiance to France. Lee, of course, had been suspicious of Franklin back in London in the early 1770s, and thus he had his eye on the old man from the moment they got together in Paris.

To complicate the situation further, Congress in July 1777 appointed Lee’s brother William as minister to Berlin and Vienna and Ralph Izard, a wealthy South Carolina planter, as minister to Tuscany. Because none of these European states wished to recognize the new republic—in a monarchical world, governments that did away with kings were not very welcome, especially if their rebellion did not succeed—William Lee and Izard had their credentials as ministers refused. Instead, the two disgruntled ministers settled in Paris and convinced themselves that they too should be members of the commission to France. They sniped and quarreled and made life miserable for Franklin. They complained that they could not get Franklin to attend meetings or sign papers, saying that the only thing he was punctual for was his dinner. They charged him with withholding information and ignoring them and with collaborating with Deane in a system of “disorder, and dissipation in the conduct of public affairs.” Finally, because Franklin was haughty and self-sufficient and “not guided by principles of virtue and honor,” they charged him with being “an improper person to be trusted with the management of the affairs of America.”80

Although Izard thought Franklin was more dangerous than Deane, because “he had more experience, Art, cunning and Hypocricy,” Arthur Lee tended to mistrust Deane more.81 He thought that Deane had creamed off profits for himself during the time he was supplying arms for the American cause. With the aid of Richard Henry Lee, his brother in the Continental Congress, he launched a campaign against Deane that eventually resulted in Congress’s recalling the Connecticut merchant in November 1777 to answer the charges of embezzlement and other matters. The accusations against Deane divided the Congress between those zealous patriots like Richard Henry Lee and Samuel Adams, who saw wickedness and corruption everywhere, and those more worldly moderates like Robert Morris and John Jay, who realized that financing a revolution required that some people make money. Many of these kinds of important urbane people supported Deane, and Franklin was one of them.

Franklin liked Deane, and he endorsed him in a letter to the Congress. He told Henry Laurens, the president of the Congress, in March 1778 that there must be some mistake in the Congress’s recalling of Deane, perhaps “the Effect of some Misrepresentation from an Enemy or two” in France. He had lived intimately with Deane for fifteen months, and he found him to be “a faithful, active and able Minister, who to my Knowledge has done in various ways great and important Services to his Country.”82

Since Franklin got along so well with Deane, Lee assumed that Franklin had to be in cahoots with him. “I am more and more satisfied that the old doctor is concerned in the plunder,” he wrote to his brother Richard Henry Lee in Congress that September, “and that in time we shall collect the proofs.”83 Deane’s subsequent actions only deepened Lee’s suspicion of Franklin. Deane eventually became so angry at the shabby way he was being treated that he publicly denounced the Congress, repudiated the Revolution, and settled in England. Since Franklin had defended Deane, the Lees and other zealous patriots such as Samuel Adams had grounds for questioning Franklin’s patriotism.84

Despite the Lee faction’s criticism, Franklin carried out his duties brilliantly. He bore his colleagues’ malice and abuse with silence and restraint. He sloughed off the charges that he was lazy and spent too much time dining and seeing people. He knew that diplomacy was not simply a matter of writing letters and shuffling papers. He knew too that the French feared that the Anglo-Saxons might get back together, and he skillfully played on these fears. He encouraged concessions from the British government and simply allowed these to spur Vergennes, who was always worried about a British-American rapprochement, into increased activity on behalf of the Americans. All the while Franklin charmed the French and put the best face he could on the course of events as he waited for an American victory. When told in the summer of 1777 that General William Howe had taken Philadelphia, he replied: “You mean, Sir, Philadelphia has taken Sir Wm. Howe.”85 With the news of the defeat and surrender of British troops at Saratoga that October, he at last had a substantial American victory to convince the French that the American cause was worth supporting with an open military alliance. With the prospect of France’s entering the war openly on behalf of the Americans, the alarmed British were now prepared to offer the colonists everything they had wanted short of independence.

THE FRENCH ALLIANCE