Chapter 2

The Analysis of the Commodity and

the Appearance of Contradiction

As the title of this section indicates, this new analysis consists in distinguishing two factors ‘within’ the commodity: use-value and exchange-value (the second of which will end up simply being called ‘value’). The notion of factor is new, and must absolutely not be confused with that of form. In a note on the economist Bailey (p. 141), Marx shows that one of the essential mistakes of the economists was to confuse value with form of value. Nonetheless, these two factors are presented in the course of the analysis within relations that we have learned to consider as relations of form: ‘The commodity is first of all … [a use-value]’ (p. 125). ‘Exchange value appears first of all as …’ (p. 126). Moreover, it is the place occupied by each factor in a relation of form that will make it possible to distinguish them most clearly.

The analysis, therefore, no longer produces material, empirical elements (commodities), but factors. Is this an analysis of the same type as the previous one? In other words, is it once more one of decomposition? In this case, we would be able to make the following representation of the analysis of the commodity:

| Commodity | → | factor 1: use-value |

| → | factor 2: exchange-value |

The meaning of the notion of analysis depends on the response given to this question: if it is true, as Marx says, that he was the first to have applied the ‘analytical method’ to his object (but did this object exist before the application of this method?), it is this notion that will make it possible to define the nature and structure of the scientific exposition.

1. ‘The commodity is, first of all … a thing’ (p. 125).

The use-value, or again the thing, is therefore the form of the commodity. This form can be directly and immediately recognized, since it appears within definite outlines: there is nothing about it that is vague and indecisive: ‘it does not dangle in mid-air’ (p. 126). The thing has a determinate place in the framework of the natural diversity of needs. It can be completely studied, on the basis of different standpoints:

– the qualitative standpoint, which reveals the ‘various aspects’ of usage, and is the work of history;

– the quantitative point of view, which measures the quality of useful things, and is the role of ‘commercial routine’.1

Use-value can therefore be entirely known, since it is a matter of a material determination (‘whatever the social form’, i.e., the mode of distribution of things). We can say by definition: things have a value only for themselves, in their individuality, in the context of the pure diversity of uses.

However, in societies where ‘the capitalist mode of production prevails’, this definition may be interpreted in two different ways: things are the matter of wealth (the German text says ‘content’: Inhalt); but, at the same time, they maintain relations with a new term, the second factor, exchange-value, of which they are the ‘material support’ (Stoff).

Thus, the notion of thing, up to now simple and clear, undergoes a kind of dislocation. Use-value is indeed the form of the commodity (that which is not its exchange-value), but it is the matter both of wealth and of exchange-value. In capitalist society (‘the society that we have to study’) the thing is a form for two contents. Either the words no longer have any meaning, or this enigma must be resolved.

The thing is not doubly determined because in it, alongside its natural character, another character of different nature is manifested, but rather because it serves as matter for two things at the same time; it is related, as matter, to two essentially different categories: wealth which is an empirical category, as opposed to exchange-value which does not offer itself immediately. Thus for the first time, but it will not be the last time, the idea appears of a thing with two faces: according to whether it is related to an empirical category or not, the thing presents a different face. Can we say that the one is the mask of the other?

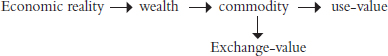

At the point that we have now reached in the analysis, we can recapitulate its course as follows:

2. Exchange-value

This does not immediately present itself in its own outlines, as those pure empirical realities that are wealth and the thing seem to do. Just as the commodity needs the contours of the thing in order to appear, so exchange-value only presents itself in a particular form: the exchange relation (two commodities together). To define value, therefore, a new notion has to be introduced, borrowed from classical economics: that of exchange:

– the commodity appears by way of the form of the thing

– value appears by way of the form of exchange.

Accordingly, in different relations of form, the two factors of the commodity occupy opposing places. Moreover, the apparent analogy between these two formal relations is in fact a dissymmetry: the thing gives the commodity clear outlines, in which there is nothing indecisive (apparently, but for the moment it is only a question of appearing); by exchange, on the other hand, value ‘appears to be something accidental and purely relative’ (p. 126).

The commodity, therefore, cannot appear as value: on the contrary, it is value that appears in the form of the exchange of commodities. We thus obtain the following definitions:

– the thing is the form of the commodity

– the exchange of commodities is the form of value

– the thing is the material support of value.

From the convergence of these definitions, the notion of value emerges as if shattered. Value was initially presented as a ‘factor of the commodity’: its relation to the commodity had to signify something. But the modalities of appearance of the commodity (the thing: ‘nothing indecisive’) and value (exchange: something arbitrary) seem to exclude any common measure between value and commodity: ‘An intrinsic exchange-value, immanent to the commodity, seems to be a contradictio in adjecto’ (p. 126). It seems that the commodity cannot appear as value.

It is in this way that contradiction makes its appearance in Capital: simply in so far as it is the appearance of a contradiction. At the same time that the contradiction is formulated (it is what structures the expression: value of the commodity), the knowledge is given that the contradiction is an apparent one. The aim of the analysis is to go beyond contradiction; and to do so, it will have not to resolve it (an apparent contradiction does not have to be resolved), but to suppress it.2

At the point where we now are, the exposition has succeeded in showing the following difficulty: there are two incompatible ways of empirically presenting the commodity. It is this difficulty that will lead the analysis further, and necessitate the transformation of the concept of commodity.

The commodity is two things at once: the commodity in itself, in its immanence to itself, its interiority, flawless in its outlines, is known as the thing; the commodity, confronted with itself or rather with its double, in the decisive experience that exchange is for it, reveals itself to be indwelled by something foreign and strange, which does not belong to it but to which it belongs, and which is called value. At the point when the commodity is abolished as such, or at least its form of appearance is abolished (by exchange, it is as if replaced: substituted by a strange double), at the point that the commodity disappears because it no longer has a proper form, it appears to be the form of something else. It is here, with the contradictio in adjecto, that a new phase of the analysis begins: the analysis of value based on the distinction between value and the form of value. Value, accordingly, is not an empirical form as the commodity is; a new form of analysis has thus to be substituted for the analysis of the commodity.

To sum up: starting from economic concepts such as they were ‘spontaneously’ defined, in the context of the use that these definitions permitted, it has appeared to be impossible to speak of the value of the commodity; paradoxically, these words cannot be uttered except in the context of an aberrant formulation. A rigorous use of the concepts brought to light their insufficiency: and it is this insufficiency that has to be suppressed, at the same time as the formal contradiction, in a new phase of the analysis, in a new analysis.

It is now possible to answer the question posed at the start: the analysis of the commodity into factors is not a mechanical analysis, a breakdown into elements. The analysis has only made it possible to divide the concept because it was conducted at a double level:

factor 2 / / commodity → factor 1

It is possible to speak of the use-value of a commodity; it is not possible to speak of the value of a commodity (for the moment). Depending on whether it is related to one or the other of its factors, the concept of commodity acquires a different significance; we could say that in the one case it is developed in interiority (the commodity in itself, in its outlines), in the other case in exteriority (the commodity divided in the context of exchange). The contradiction, therefore, is not in the concept, deduced from the concept: it results from the two possible ways of treating the concept, from the possibility of applying to it two different analyses, at different levels. The contradiction here is a formal one, since it pertains to the mode of presentation of the concept. The contradiction between the terms, which is not even a contradiction between concepts but rather a difference, a break in the treatment of these concepts, properly belongs to the process of exposition and in no way refers to a real process: we could even say that if refers to the specific way that the process of exposition has of excluding the real process. Accordingly, the formal contradiction is a contradiction between the different forms of the concept, these forms being determined by different levels of the conceptualization. We should not conclude from this that the contradiction is artificial, resulting from an artifice of exposition; on the contrary, it indicates a necessary moment in the constitution of knowledge.3

This analysis reveals, like the previous one, how the concepts that sustain the scientific exposition are not of the same kind. Thus, they do not directly proceed from one another: rather than deduced from one another, they are rubbed against one another. It is this disparity that makes it possible to advance in knowledge, producing a new knowledge. If there is a logic of exposition, it is the inexorable one that directs this work of the concepts. This logic of exposition that constitutes its own material leads to the concepts being repeatedly defined; the exposition passes from concept to concept, new not only in their content but also in their form. What determines a moment in the exposition, an analysis, are the conflicts between the concepts, the breaks between the levels of argumentation: these ‘defects’ lead the exposition to its conclusion, to the final break, which obliges it to be resumed at a different level, proceeding to a new analysis.

This is why the formal contradiction will not have to be resolved: in a reprise, the exposition will establish it elsewhere than on the terrain of this contradiction. It is then said that the commodity is a thing with a double face (the two factors), inasmuch as it is two things at the same time (in the experience of exchange). If there is a further analysis, it can no longer bear on the commodity conceived as an abstract unity: its minimum object will now be two commodities. This mutation of the object also shows that there is not a continuous deepening of the analysis, in a purely speculative movement of the Hegelian type. The insufficient standpoint is exchanged for a different one, incompatible with the former (and which absolutely cannot be taken as complementary to it): to speak of two commodities is to do exactly the opposite of what was done in speaking of a commodity, since it is to make abstraction of use-value (see p. 128: ‘once the use-value is set aside’). We see what extraordinary conditions are required in order for one of the two factors of the commodity to be studied by itself.