Chapter 3

The Analysis of Value

‘Let us consider the matter more closely’

1. The starting-point or object of the analysis is now the exchange relation, the relation of equality between two commodities. It will not be necessary, therefore, to take into account the money form in order to define value; this form is a developed form (its analysis will be deduced from the analysis of value: this will be the genesis of money), whereas exchange is an elementary form.

In order to understand this new starting-point, it is interesting to refer right away to the famous passage on Aristotle that occurs twenty pages further on (pp. 151–2). As we know, Aristotle was able to relate the money form of the commodity to the elementary form of the exchange relation: he understood that value appears in the purest state (we could almost say ‘in person’, if the underlying nature of value was not precisely not to show itself) in a relation of equality. This is what ‘displays Aristotle’s genius’. But certain historical circumstances, which there is no need to dwell on here, prevented him from finding ‘what was the real content of this relation’; he saw very well that the form of appearance of value had the general aspect: a = b, and he was even able to give models of this structure, but he could not say what a and b were, what they were made of. Or more exactly, he believed that he did know: he believed that a and b were as they appeared in the empirical models, that they were things. But he also saw at the same time that it was not possible to speak of equality between things: ‘Such a thing, in truth, cannot exist, says Aristotle.’ Aristotle thus held the two ends of the contradiction, he went as far as his knowledge could go: it was necessary to simultaneously assert equality between two elements, so as to have value appear, and to destroy the notion of thing (thus to introduce that of commodity), so as to maintain the assertion of equality. In order to resolve the antimony, it was enough to know that the equality was not between things, but between commodities (and for this, it was necessary to wait for ‘the commodity form to have become the general form for the product of labour’). The contradiction in terms was where Aristotle’s knowledge ended, and this is also where the analysis of value begins.

2. The difficulty that makes it necessary to begin a new analysis arises from the representation of exchange in the form of two things at once. This expression, formulated in empirical terms, has no empirical meaning. Thus, the analysis must no longer be conducted in terms of experience. A thing, all things – that means something, at a pinch; but nothing makes it possible to distinguish, i.e., ultimately to explain, the relation between two things, which, at the level of experience, can have only an illusory function. In experience, it is possible to conceive that two things stand alongside the other, that they are juxtaposed (like commodities in wealth). But they do not explicitly tolerate any relation; from the standpoint of experience, between two things and one thing there is a quantitative difference, but absolutely no qualitative difference.

Let us take ‘a given commodity’ (p. 127): it has value only if it enters into the exchange relation. The following chapter will teach us that it does not enter this by itself: it has to be brought there by its guardian, by force if need be. (Marx’s description of the market includes all kinds of things, including [in the words of the French medieval poet Guillot] ‘femmes folles de leur corps’.) Thus there is nothing natural or immediate in the relation between two commodities: it has to be produced, materially realized, in a gesture reminiscent of that of experimentation.

3. The relation between two commodities, provoked in this way, is defined as a relation of expression. If a = b, it is said, by definition, that b is the expression of a. The notions of form and expression must not be confused: the relation a = b is a form (the form of appearance of value); the terms that make up the relation are not expressions of form, but of something else that still remains to be determined.

By the fact that the two terms of the relation (two commodities) each express one another (in a non-reciprocal manner, as will later appear), the relation is itself a form of appearance. Thus, value is not in the relation, in the immediate sense of the expression; it is neither in a nor in b. By the fact that a is expressed in b, it is not a, but the entire relation that reveals the value: ‘Exchange-value has a content distinct from these various expressions’ (p. 128). Through this relation there is expression, but the terms of the relation must not be taken for the content of the relation.

The analysis of value is thus based on a material logic that makes it possible to move from concept to concept (for example, to deduce value), but it no longer has anything in common with the empirical method of decomposition nor with the formal method of contradiction, which at different moments of the exposition were able to play an analogous role.

4. The relation is not realized simply in the qualitative form a = b (a is made up of b). It is also and above all a quantitative relation: ax = by (a is so much of b). The relation is essentially the place where measurement appears: it is at this moment that the analysis undergoes a decisive mutation.

The new analysis begins with a decisive choice: the refusal to study the exchange relation as a qualitative relation, to only consider in it its quantitative content. In order to know the nature of value (to understand that it is not something arbitrary, as it shows itself in the relation), it is necessary to emerge from appearances, to reject the form of appearance of value in order to examine its content, which is ‘distinct from its various expressions’, the empirical models. Behind the ‘two things’ that form the immediate matter of the relation, a third must be sought, ‘which by itself is neither the one nor the other’: the structure of this relation.

The equality of the relation (which defines its reality) can only be constituted and determined on the basis of a measurement, or rather a possibility of measuring, in itself distinct from all particular relations (which are applications of the measurement, its ‘material supports’). The ‘objects’ that enter into the exchange relation can only be measured, which means, as we shall see, calculated, on the basis of another object ‘different from their visible aspect’.

Analysing the exchange relation between two commodities, therefore, does not mean extracting from the commodity this second factor that does not immediately appear in it, by proceeding to an empirical comparison. In order to interpret the relation, it has itself to be related to a norm of appreciation that is of a different nature.

5. It would be possible on this basis to formulate a general rule, valid not only for economic analysis: to compare objects non-empirically, it is necessary as a preliminary to determine the general form of this measurement. We come across here for the first time this requirement that is an essential aspect of the ‘Logic of Capital’, which as we know, Marx did not write. Every study of form bears at least on two distinct levels. It is not possible to make a relation of expression say what it expresses if it is examined only in its empirical reality; this leads to the elaboration of a material theory of expression that criticizes, as blindly empirical, all descriptions of meaning (therefore, all the attempts of semiology). To know what a relation expresses, it is also necessary, even first of all, to know what is expressing it. In other words, it is possible to understand how a meaning (here equality: we shall see further on that this is not neutral, reciprocal, but on the contrary polarized) passes between the terms of a relation only if we represent this relation itself as one of the terms in another relation of expression of another kind.

6. The analysis of the relation as it is immediately given cannot produce any knowledge. It has to be transformed, interpreted, reduced to an equation; it then signifies something else. We have moved from ‘what immediately presents itself’ to the conditions of this appearance.

Accordingly, value only presents itself as such (within the limits of its presentation) within the exchange relation, but it is impossible to analyse this relation in itself, unless, as Aristotle did, we stop when faced with the contradiction. The fact is that value is not in the relation like the kernel in the fruit: we only move from the commodity, or two commodities, to value, by way of the break that separates one form from another. The exchange relation is the only means of access to value, but it does not give a direct hold on it. The relation is the only path that leads to value, but the path only proceeds by the relation. When we reach the concept of value, we have to turn away from the relation itself in order to examine the conditions of its appearance. Paradoxically, the exchange relation is only the form of appearance of value inasmuch as value does not appear in it.

It is the equation that provides the means of escaping from the exchange relation and seeing the concept of value: ‘Whatever the relation of exchange between two commodities, it can always be represented by an equation.’ It is then possible to begin ‘the derivation of value by analysis of the equations in which every exchange-value is expressed’ (Postface to the Second Edition). The relation, therefore, has to be reduced to its equation in order for value then to be derived from this equation. It is not a question of deducing value from its form of appearance (a deduction which, as we have seen, is impossible). Nor of reducing the objects that empirically fill the relation to their abstract value: on this point, Marx explains himself very jovially in a letter of 25 July 1877:

Sample of the ‘great perspicacity’ of the academic socialists:

‘Not even great perspicacity such as is at the command of Marx is able to solve the task of “reducing use-values”’ (the idiot forgets that that subject under discussion is ‘commodities’) ‘i.e., vehicles for enjoyment, etc., to their opposite, to amounts of effort, to sacrifices, etc.’ (The idiot believes that in equalizing values I wish to ‘reduce’) use-values to value. ‘That is to substitute a foreign element. The equation of disparate use-values is only explicable by the reduction of the same to a common factor of use-value.’ (Why not simply to – weight?) Thus dixit Mr Knies, the critical genius of professorial political economy (MECW 45, p. 252, translation modified).

In point of fact, this genius would have been better inspired to refer to the 1844 Manuscripts, if he had known them, in which reversals of pleasures into pains are quite frequent. In the rigorous exposition of Capital there are no more dialectical reversals or naïve reductions: reduction and deduction are only valid at the price of a strict combination, the function of which is to exclude any confusion between the real and the thought.1 A long road has been travelled from the text of The Holy Family on the process of the fruit, in which Hegelian deduction is replaced and inverted to become an empirical reduction. The transition by way of the equation, which arranges and transforms reduction and deduction, places on the same level and confounds in a single critique the two traditional methods of idealist knowledge: analysis, as newly defined, is removed from both empiricism and from logical spiritualism.

7. At the conclusion of the complex reduction-deduction operation, the notion of exchange relation no longer serves any purpose and can be abandoned, as has already been done for many other notions: ‘The two objects are therefore equal to a third thing, which in itself is neither the one nor the other. Each of them, so far as it is exchange-value, must therefore be reducible to this third thing, independently of the other.’ Value is no more obtained by an empirical reduction that starts from the exchange than it is by an empirical reduction that starts from the commodity. The paradox of the analysis of exchange is that value is neither in the terms of exchange, nor in their relation. Value is not given, or revealed, or displayed: it is constructed as concept. This is the reason why the mediation of the relation loses its entire meaning at a certain moment in the analysis: exchange is simply the means for arriving at value (as Aristotle saw), but it has absolutely no function in defining this: value does not confuse its reality (as concept) with the stages of its research.

Or again: value cannot be a content common to the two objects, except by being at the same time in each object; however, it is independent of the object that supports it, it exists in its own right, ‘by itself’. Nor is it between the two like another object of the same kind (which was Aristotle’s illusion); it is an object of a different nature: a concept.

The analysis of value is not dialectical, in the Hegelian sense of the term, in that it does not depend on a ‘dialectic of commodities’ (identity, opposition, resolution in the concept, already given at the start in an undeveloped form). The movement of the analysis is not continuous, but repeatedly interrupted by the questioning of the object, the method, and the means of exposition.

8. In order to understand this differentiation within the exposition, without which no rigorous analysis would be possible, we must dwell on the example of elementary geometry, which plays a key role in Marx’s argument, as its function is to reveal the form of reasoning specially adapted to the final stage of the analysis:

An example drawn from elementary geometry will put this [the transition from exchange to value] under our eyes. In order to measure and compare the surfaces of all rectilinear figures, we break them down into triangles. The triangle is itself reduced to an expression totally different from its visible shape: half the product of the base and the height. In the same way, the exchange-values of commodities must be reduced to something that is common to them, of which they represent a greater or lesser quantity (p. 127).

The example is designed to make clear the role of the equation in the determination of the concept. The calculation of surfaces (elementary as this may be, it cannot be immediately and spontaneously revealed as an empirical given, but requires a work of knowledge) is done by two successive analyses. The first of these, an empirical breakdown analogous to that which revealed the commodity, produces a first abstraction, the triangle, the basic element of all ensembles; the problem is thus posed as one of measuring triangles. This measurement is obtained by way of a second analysis, which relates the triangle to the equation of the area, ‘an expression totally different from its visible aspect’. The measurement of the area does not follow from the empirical comparison between all things that have areas, i.e., figures. The question of greater or lesser area is only one aspect of the fundamental question that bears on the notion of area. The expression of the area is not obtained by a reduction starting from the empirical diversity of things that have areas, and conversely, these greater or lesser areas are not obtained by a deduction starting from the notion of area: the concept is the particular reality that makes it possible to account for the reality. Thus, the abstract expression is ultimately, and fundamentally, in relation with each ‘object’ taken in itself, i.e., independently of others: it is not the concept of relations between objects, i.e., an empirical concept, but the concept of each object in particular, indicated thanks to the mediation of the relation, but not produced by this. Thus the (implicit) criticism of Hegelianism is at the same time an (explicit) critique of empiricism.

The equation for the area, like that for exchange, is an idea, i.e., an ‘object’ of a quite different kind, not a content of reality but a content of thought: to take up a classification already used, a Generality III;2 we understand then that when it is said that analysis reduces real objects to a third ‘object’, the term object is used in a symbolic sense (though not an allegorical one: the concept is indeed a kind of object). In the same way as the idea of a circle has neither centre nor circumference, so the area of the triangle is not in itself triangular; in the same way, too, the notion of value is not exchangeable.

We thus understand that the analysis of the relation that brings the terms together in the context of exchange itself refers to a third ‘object’, of which in the extreme case it reveals the absence: this third and new object is concealed by exchange rather than being shown by it. The reality, the practice of exchanges and markets, was not enough to create it: there could be markets and exchanges for a very long time, in very different forms, without the measure that the concept of value is for them being known and reported. Marx did not find the concept of value on a market stall, ‘under the sign of knowledge’: this business, where there would be scarcely anything to exchange, pitches its camp somewhere else than on the ground of markets. Without the rigour of scientific exposition, which alone succeeds in producing knowledge, the concept of value would have no meaning: i.e. it would not exist.3

The example of simple geometry, therefore, despite its simplicity or perhaps because of it, has a considerable importance; it defines the nature of value and confers its essential quality, that of a scientific concept. We have to signal the analogous role subsequently played by other examples: that of chemistry (p. 141) and that of the measurement of physical properties (p. 148); these will also serve to mark the relation between the concept and the reality it reflects.

9. The procedure of the exposition is neither one of empirical reduction nor one of conceptual deduction (if Marx gives the impression of following the movement of a dialectic of this kind – which we know is no more than ‘coquetry’ – it is by showing precisely how deceptive this is, not describing a real movement but the play of an illusion). 0n the basis of empirical abstractions (which orient and guide economic practice and its scientific ideologies), it is necessary to constitute this content of thought, this concrete of thought, that is the scientific concept: this content is neither absolutely derived nor absolutely deduced, but rather produced by a specific work of elaboration.

It is possible at this point to give the determinations of the concept, of that ‘something common that is specific to each object before characterizing the relations of two objects’ (p. 141: this is an ‘inherent’ property). Since the method of analysis is not the reversed figure of the real process of constitution, but repeatedly resumes the gesture of turning away from illusions (which only show themselves inasmuch as they disguise: one could rightly say that they conceal), in a genuine journey of appearances, this determination of the concept is first of all negative: ‘This something common cannot be …’ By this negation, the modes of empirical appearance are radically brushed aside.

The ‘something common’ cannot be defined on the basis of natural qualities, or of use-values. Here the example has to be set aside: in the case of simple geometry, the notion of surface area cannot be directly deduced on the basis of the diversity of areas, precisely because it serves to define this diversity. The relation between use-value and exchange-value from now on assumes a very different character: it connects the concept to its thing only in very particular conditions that require the ‘historical’ constitution of this relation to be examined. Engels adds a very important note on this point at the end of the section (p. 131). However, it is possible to remark that the relation between the concept and its thing is not the relation between exchange-value and use-value, but between value and commodity: the notion of value qualifies commodities as the notion of area qualifies areas.

The act of exchanging only manifests the appearance of value inasmuch as it ‘makes abstraction of use-value’, this being even its precondition; without this abstraction, the act of exchange would have no sense. ‘Every relation of exchange is characterized by this abstraction’: a proposition whose meaning Aristotle already understood, though he was unable to formulate it himself. Exchange manifests itself first of all (although indirectly) as the suppression of every quality, and on the basis of this disappearance it brings to light a proportion: value can only be distinguished on the basis of a quantitative (and no longer qualitative) diversity. We shall see that this is still only the most superficial aspect of the analysis; the abstract character of this quantitative relation (proportion) must not be confused with the real conclusion of the analytic reduction. To take up the example of elementary geometry, the analogy with the calculation of surface area, it is not the proportion that is the most apparent precondition for exchange to appear, the very precondition that the point is to reduce, to account for. Proportion, in its way, indicates (refers to) a concept: it is not merged with this concept. The quantity of the relation does not define value in itself, as qualitative diversity defines use (moreover, we have seen in passing that there is a quantitative perspective on use-value). Between quantity and quality there can be no real discrimination, but only a superficial opposition: the question is simply one of a provisional classification, a way of representing the distinction between use-value and exchange-value; the actual form of this distinction is to be sought elsewhere. The opposition between quantity and quality only speaks to us inasmuch as we do not take it literally.

Thus, the negative determination of value (‘by making abstraction of’, which is a particular way of naming the reduction) leads not to a purely quantitative study (bearing on proportions), but to the quest for a new quality: that of being, as we know, the product of labour. As mere things, ‘objects’ are differentiated by their uses, i.e. their irreducibility. If this character is set aside, then at the same time as their empirical qualities disappear, there appears, not their quantitative aspect, but another quality (of a quite different nature: not directly observable): ‘There remains only a quality …’ It will be precisely value whose substance it will then be possible to determine.

10. However, at the moment when value appears in person, substantially, we perceive that the object that it characterizes is itself ‘metamorphosed’ (an expression that recurs twice). If we look for what has been made possible by the relation between the objects, what can be done only by abstraction from their character of things, we perceive that the relation is different from how Aristotle, for example, believed. Not only is value something else, a third ‘object’, but we perceive that the relation in which it first manifested itself is also other than we believed. To understand the constitution of the relation, it is necessary to introduce a new ‘factor’ that metamorphoses the relation itself. At that point, we have passed completely to the other side of the contradiction; and at that moment too, the phantoms arise.

The object has metamorphosed. From being a thing, it has become a commodity. And this is clearly not a speculative conversion but a real transformation. According to the final text on the thing and the commodity, made clear by Engels’s note, things may very well not be commodities even while being products of labour; they have become these. On the one hand, we have moved from the idea of thing to the idea of commodity; on the other hand, things have effectively become commodities. Does this mean that the movement of exposition of concepts simply follows (or returns in the opposite direction, though this is ultimately the same thing) the process of constitution? Nothing of the kind. The real transformation and the knowledge that we acquire of this by seeing the metamorphosis are heterogeneous. To see the metamorphosis is to produce a new knowledge (by determining the substance of value); there has been no movement from the corresponding concept, whether the right way up or upside down, to the real movement, but rather the suppression of an illusion. It is to see that the reality we seek to know is not that which is manifest, that which we believe: it is not made up of things, but of phantoms.

This knowledge has come neither from a work of reality on itself, nor from a work of the idea on itself:

A. Value is not a concept obtained on the basis of ‘objects’ by making abstraction of their individuality, thanks to the privileged situation constituted by exchange (which would then be an empirical abstraction); the concept is not immediately produced by the exchange situation. The concept of value is the product of the work of knowledge, which precisely suppresses what in the relation was clearly characteristic (what distinguished it, making it visible), in order to drive out the phantoms that haunt it.

B. The concept can only be produced on the basis of concepts (by turning one’s back on empirical realities), a fact that could give rise to the belief in a speculative process. There is in fact a change at the level of the concept: not within the concept, but outside it (the transition from concept to concept); this movement is not produced by the concept, but it produces knowledge on the basis of the concept in definite material conditions. The real is not directly modified by the appearance of this new knowledge: ‘[it] retains its autonomous existence outside the head just as before’ (1857 Introduction). The idea of the thing is not a speculative stage that would lead us as if by the hand to the concept of commodity: it constitutes one of the elements of the conceptual material on which knowledge works. In the same way, the commodity is such only on the basis of the thing: but the consideration of things does not lead us to know what a commodity is, nor even that the concept of commodity has any meaning. The thing is not a blind form of the commodity; strictly speaking, it is the sign of our blindness at the moment when the commodity appears. The knowledge that we have of value is obtained only on the basis of a critique of the original concept that we have of the thing and of exchange.

The metamorphosis is thus neither empirical nor speculative, it consists simply in the fact that we have emerged from the false contradiction by suppressing it.

11. The ‘two-sided thing’, therefore, was simply a ‘first approximation’ (the same, moreover, as were the two things together: the terms of the contradiction have disappeared). The commodity is not a torn, contradictory reality, separated from its value. On the contrary, the commodity is well determined by its fundamental quality (on the basis of which a quantitative calculation is possible: the calculation of value from the quantum of labour). It is simply not such as it appears (and vice versa). Its true reality is that of being a phantom (not the product of one labour, but of labour in general). It is the phantom that must be expressed to the exclusion of any empirically observable quality, yet it is none the less a material reality.

If the two-sided thing is simply an inadequate representation, use-value and exchange-value must absolutely not be placed on the same level. There can be no contradiction between them, except by ignorance or illusion (and so the contradiction is only one of illusion). We can then return to a problem already envisaged: the ‘two factors’ of the commodity have not been obtained by differentiation within the concept.

The ‘objects’ that were presented in exchange are no more at that moment than ‘sublimates’: ‘They now only manifest one thing.’ We have reached the final precondition: labour in general that is deposited, accumulated, crystallized, sunk, in commodities. This labour is itself produced by a ‘single power’: ‘the power of the labour of the whole society, which is manifested in the entirety of values’. The analytical study started out from the simple element (value), to return to the complex and structured totality that ultimately constitutes it. And so value is defined only in relation to the entirety of values. It is thus radically distinguished from use, which is determined simply by its relation to the thing. The expression ‘value of the commodity’, therefore, acquires a new meaning, since it no longer constitutes the end-point of the analysis but only one stage of this. If the substance of value is labour in general (which must not be confused with labour ‘independent of any form of society’: p. 133), it is because the simple element of value has only a diacritical meaning, by the relations it maintains with all other values. The formal study of simple elements is thus incomplete in itself. The study of an apparent formal contradiction gives way to that of the real contradictions that constitute the capitalist mode of production.

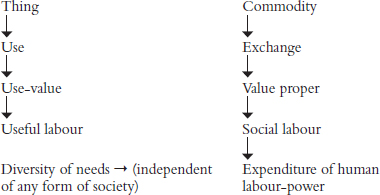

This is particularly important, as it becomes possible to display clearly the dissymmetry that exists between thing and commodity: not only the historical dissymmetry, the fact that their relation is a relation of succession, irreversible, without a possible reciprocal counterpart. The only interest of introducing into the course of the analysis the actual process of constitution of the commodity is to the extent that it is possible to show how this history is as it were deposited in the material analysed, where it is found in the dissymmetrical disposition of conditions:

Use-value is not determined under a diacritical form, but in its direct relation to the thing; it does not acquire its meaning from a structured totality, but within a radical diversity.

It is impossible, therefore, to present the distinctive characters of use-value and exchange-value in an analogous form: the commodity having its value, as the thing has its utility. Once again, there is not symmetry or reciprocity: the distinction of the two levels is not abstract (within an ideal totality, divided against itself), but real. And only the analytical method enables this distinction to be accounted for.

The ‘objects’ that fill the markets of capitalist society actually are divided: on the one hand they are useful, on the other hand they are exchanged. There can be no speculative conflict between these two aspects: there can only be a real conflict. There can also be adequate knowledge of the distinction.

It is possible to extract from this reading of the opening pages of Capital the following conclusions:

1) The critique of empiricism and the critique of speculative idealism go together.

2) The real process (appearance of the commodity in economic history) is not immediately reproduced (reflected) by the movement of analysis: yet the ‘historical’ difference that makes it possible to conceive the thing without the commodity, but not the commodity without the thing, is found again in the order of exposition that establishes the preconditions of the concepts. In the context of this dogmatic order that is specific to analysis, the commodity cannot be presented as the equivalent, or the other side, of the thing. This expresses the necessity for an order of succession that makes it possible to think the transition from the thing to the commodity, but not in the opposite direction.

Value is not to the commodity what use is to the thing, because these terms only have their meaning at levels far removed from the conceptual analysis. This formal impossibility, which defines a dogmatic order between the concepts, is thus the best way to account for the historical order. The dogmatic order is not distinguished from the historical order as thought is distinct from the real (within the real); the dogmatic order makes it possible to think the historical order.4

3) As we have noted, the concepts do not keep an immutable meaning in the course of the analysis. For example, the concept of commodity is initially something like a ‘Euclidean’ concept: the commodity appears in a form with clear outlines (the equivalent of a figure); it is thus susceptible to an empirical definition. The same does not hold for the concept of value, which is not susceptible to such a definition (it rules it out from the start): value appears in an undefined form, its concept will have to be constructed by the combination of a reduction and a deduction. But, recursively, once the substance of value is disclosed, the commodity appears as incompletely characterized by its definition (which was only a manifestation); in its empirical outlines, it is only the phantom of itself: faced with the true concept of value, it undergoes a metamorphosis. Thus, while the concepts are not each successively developed from the other, they are also not posited each alongside the other in a relation of indifference: they mutually work on and transform one another. The process of knowledge is also a material process, though not the only one.

This work has to bring concepts from their original state as ideological concepts borrowed from more or less scientific theories (Generalities I) to the state of scientific concepts (Generalities III). Certain concepts undergo this mutation; others, which are useful for a while or at the start, are eliminated along the way.

This mutation is also due to the work of concepts that do not directly pertain to the science of history. These concepts, which describe the form of reasoning and genuinely do the work of analysis (Generalities II), come from very different domains:

| – general scientific methodology | analysis abstraction |

| – the tradition of logic and philosophy | form expression contradiction |

| – mathematical practice | equation reduction measurement |

The function of these concepts is to transform (by analysing them) the concepts that give content to economic theory.

It appears that these concepts themselves undergo a transformation in the course of exposition. They completely change their meaning. As we have seen, the analysis is repeatedly redefined, inasmuch as it takes place at different levels. In the same way, the notion of form is employed in at least two incompatible uses: the commodity appears as a thing (form is the form of appearance that gives the first clear outlines to the commodity); value appears in the exchange relation of commodities, or rather apropos this relation. This form of appearance is particularly precarious, as it is accompanied by a contradiction; which is why it is necessary to return, by reduction, to another term that is the true form of value, this time not directly apparent: the value equation (to make it appear in its phantom outlines).

The concepts that ‘work’ others are thus themselves worked. We can ask what they are worked by: if they are themselves Generalities I that tend to become Generalities III, what concepts play the role of Generalities II for them? The answer to this question is simple: it is other concepts, the ‘concepts of content’, that hold this place of formal concepts and put the former to the test. Thus the work of knowledge is conducted in two directions at the same time (in which respect it is genuinely dialectical). The text of Capital, as we have seen at the start, is written on two levels: that of scientific theory in general (form of reasoning) and that of the practice of a particular science. According to whether one reads it from the position of one standpoint or the other, the concepts have a different action:

4) The scientific exposition is organized in a systematic manner, but this does not mean that it refers to a homogeneous and coherent order. The connections between the concepts are neither unambiguous nor equivalent: they are also established at distinct levels. The relations between the terms of the discourse, therefore, are not those of strict concordance: their value is above all by the fruitful tension that certain discordances realize (e.g., the contradiction in terms). We can understand, therefore, why the transition between concepts and propositions, though rigorously demonstrated, does not obey the mechanical model of deduction (a relation between equivalent or identical elements): it is on the basis of the conflict that opposes several kinds of concepts and makes them work that new knowledges are produced.

We understand then why the representation of scientific effectiveness as ordering is quite insufficient. Knowledge does not consist in substituting order for disorder, in the arrangement of an initial disorder. An image of this kind, while it certainly represents one essential aspect of spontaneous scientific practice (the ideal of taxonomy), does not correspond to the material reality of scientific work. The idea of an immediate object of science, disordered and given, is false: it is knowledge that constructs its content, i.e., its order; it is knowledge that defines its starting-point and its instruments.5 The essential thing is that the order it establishes is neither stuck to a reality ‘to be ordered’, nor is it definitive. On the contrary, it is always provisional; it has constantly to be worked, confronted with other type of orders. What defines the unending process of knowledge is the transition from one order to another, by successive breaks.

The opposition between order and disorder is too poor to account for such an activity. The different orders, related among themselves by an unceasing conflict, are in themselves so many disorders (insufficient, defective, provisional); the real effort of knowledge consists in establishing in the site and place of the real disorder (or rather elsewhere) a disorder of thought suited to measuring it. True rationality and true logic are those of diversity and inequality. Producing scientific knowledge means acting with disorder as if it were an order, using it as an order: this is why the structure of science is never transparent, but opaque, divided, incomplete, material.