* where Mozart was said to have played the organ.

* where Mozart was said to have played the organ.Prague, May 27, 1989

THE WEATHER REPORT in Prague that morning called for warm temperatures and sunny skies – truly a bright new day, Karl thought, feeling on the verge of a new beginning. Don’t be overconfident, he quickly cautioned himself as he rose. There was still much to do before he and the paintings would be safe.

Over a quick breakfast, Karl had the opportunity to glance through the local newspaper, Rudé Právo, or the Red Right. There on the front page was the smiling face of President Gustáv Husák. It was not surprising to see him in fashionable dress, meeting with visiting dignitaries and talking about the country’s deep interest in cooperating with its citizens and the desire for expanding freedom and democracy. This rhetoric was typical of the kind of manipulation that took place here on a daily basis. But while Husák and others were trying to put a new face on the totalitarian regime, life here was still empty and restricted. More than ever, Karl could not wait to finish up his business here and get back to Toronto.

He arrived at the Canadian embassy by mid-morning. The receptionist smiled him through the entrance and escorted him down the hallway to Richard VandenBosch’s office. Their footsteps echoed down the long, empty hall in a synchronous drumbeat, the only sounds on this quiet weekend morning, Karl noted with satisfaction. There were few staff to be seen and, more importantly, no non-embassy construction workers in the building.

Karl and Richard shook hands and exchanged warm greetings. “I’m so grateful to you and the embassy…” Karl began, but was instantly stopped by Richard’s raised hand.

“No need to thank me. Let me get my car keys and let’s go get your paintings.”

The words were music to Karl’s ears. The two men walked quickly out of the building and across the gated courtyard where embassy automobiles were parked. There were several vans, a black official-looking Tatra that was probably used to transport the ambassador, and several smaller vehicles. VandenBosch bypassed the larger cars and headed straight to one corner of the lot where a small blue Honda Civic was parked. He proceeded to unlock the driver’s door. Karl stopped dead in his tracks. The good news was that the car had diplomatic license plates. It would not be stopped driving through the city. The bad news was that there was barely enough room in this car for the two men. There was no way that the four paintings were going to fit.

“Perhaps I didn’t explain about the size of the paintings,” Karl started as he turned to face Richard. The young diplomat waited, quizzical. “They’re big,” Karl stammered. “I mean to say, they’re huge, bigger than this back seat, bigger than this car!” Unless they planned to strap the paintings to the roof, the vehicle was completely inadequate. He gestured helplessly, stretching his arms out and over his head to demonstrate the expanse of the paintings.

Richard stood rooted to the spot for another minute. Finally, he scratched his head and let out a long, low whistle. “I guess perching four priceless oil paintings on the roof of my car isn’t going to work, is it?” Karl snorted, then laughed out loud and shook his head. A moment later Richard joined in.

“Wait here,” he said, still laughing. He reentered the embassy building, emerging minutes later with a security officer who led the two men to a Volvo van. This vehicle had the same protective diplomatic license plates, but was much more suitable for their cargo. Richard smiled and winked at Karl. “I believe this one will work better.”

The two men drove in silence to Jan’s apartment. The streets were pulsing with activity. Richard expertly wove the van in and around the traffic mayhem, dodging other cars, motor scooters, and pedestrians who brazenly stepped out across the boulevards. Karl watched it all through the van window, his heart racing as rapidly as the traffic around him. No one out there knew or cared about what he and Richard VandenBosch were about to do, he realized. But Karl felt as though he were part of some kind of conspiracy plot, driving to the scene of the heist!

They parked directly in front of Jan’s apartment building and climbed the stairs to his flat. Jan opened the door after the first knock and welcomed them in. Karl quickly introduced Richard and then followed Jan down the hall to the back bedroom. Richard gasped when the blankets and bed sheets were pulled back. Even though the paintings were still wrapped in paper and tied with string, he could easily appreciate their size. “I see what you meant about the car,” he said, shaking his head. Karl nodded and motioned Jan and Richard to position themselves at the corners of the bed to begin lifting the paintings.

Without much discussion, the three men raised the top painting and carried it down the long staircase and into the parked van. Then back up the four flights of stairs to get the second painting. The men moved quickly, so Karl had little time to dwell on the knot that rested in the pit of his stomach. He was wary, glancing around and over his shoulder all the time. It was one thing to know that the informer in Jan’s building was away for the weekend. They were safe from that scrutiny. But Karl did not want to meet up with any other residents of the apartment building, either. He had no desire for anyone to snoop around or ask any questions.

An old man opened his apartment door as they passed. The resident’s expression was unreadable as he gazed passively at the three men carrying an oversized wrapped package. He looked as though he had watched events in his country for decades and had learned how not to react. Jan nodded to him and muttered a greeting. The man returned the nod and retreated into his flat.

Karl’s hands felt slippery and he quickened his step. No time to dwell on the old man. No time for fear to take over. Just get the paintings down the stairs and into the van. Every minute in the open was a moment of potential detection. No one else seemed to be around. The hallways and staircases were deserted, and the street in front of Jan’s building was equally quiet. The only pedestrians were a couple of elderly women who walked by carrying baskets of groceries. They barely lifted their chafed and wrinkled faces to acknowledge three men carefully placing oversized wrapped packages inside a parked van.

The paintings were heavy, and by the time they had finished descending the staircase for the fourth time, Karl was panting. It was close to noon and the humid air was stifling. Sweat glistened on his forehead and he reached into his pocket for a handkerchief to wipe across his brow. Jan and Richard were out of breath as well. Before closing the van door, Karl placed several more sheets and blankets from Jan’s bed around the stacked paintings to provide additional protection for the drive back to the embassy. Finally, he slammed the door shut and turned to face Jan.

“Well, that’s it, then,” he began, glancing once more down the deserted street in front of Jan’s apartment building.

Jan reached out to shake Karl’s hand. “Good luck, Karl. I hope you are able to get your paintings to Canada quickly and with no difficulty.”

“I’m so relieved that this worked out today,” Karl said.

Jan nodded. “I am too.”

There was so much more on his mind that he couldn’t bring himself to say. He still grappled with what he thought about Jan Pekárek and his motives. But, in the end, gratitude won out. He pumped Jan’s hand and muttered, “Thank you for contacting me.”

Jan nodded again and began to step back onto the sidewalk. But Karl stopped him. He reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out some papers. “Your documents,” Karl said, handing them over to Jan. “I know you wanted these back.”

Jan accepted them gratefully and handed Karl a single sheet of paper. “A receipt,” he said. “Or at least an acknowledgment that you now have all four paintings and our business is done.”

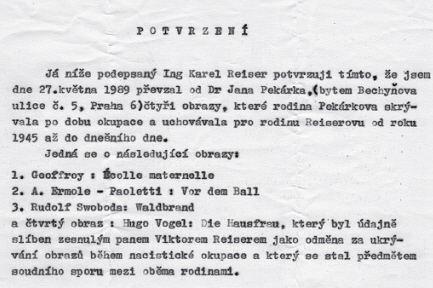

Karl quickly scanned the document. Written in Czech, it read as follows:

Receipt

The below undersigned certifies that on the 27th of May 1989,

Engineer* Karl Reiser received from Dr. Jan Pekárek, residing in

Bechynova ulice 5, four paintings which the family Pekárek hid

during the occupation for the family Reiser from 1945 until today.

The paintings are as follows:

1. Geoffroy: École maternelle

2. Antonio Ermolao-Paoletti: Woman at the Ball

3. Rudolf Swoboda: Forest Fire

The fourth painting, Die Hausfrau by Hugo Vogel, was supposedly

promised by the late Victor Reiser as a reward for hiding the

paintings during the Nazi occupation, and became the subject of a

legal dispute between our families.

The document was not signed. It was curious to Karl that Jan had chosen to include a reference to the legal clash between the families as to the ownership of the Vogel, and that he had claimed this fourth painting in writing as having been promised to his family. Karl did not comment on that. He thanked Jan for the receipt, shook hands once more, and then climbed into the van next to Richard VandenBosch.

“Next stop, the Canadian embassy,” Richard said, as he quickly edged the van into traffic.

Once again, Karl was quiet during the drive. And again, he could feel his heart pounding inside his chest. But this time, it was exploding with excitement, knowing that the paintings were with him and would soon be safe inside the embassy building. He thought again of his father, who had never lived to see the end of the war, and of his mother, who had never lived to see the paintings returned. He felt so close to fulfilling his family’s mission that he could barely breathe.

Richard parked the van behind the iron gates of the embassy courtyard, and the two men began to carry the paintings into the building. Only once they were safely inside the hallway next to Richard’s office did Karl begin to remove the string and wrapping paper. Then, they lined them up, leaning them against the walls. Finally, they stood back to view the paintings.

Richard was taken aback by how impressive they were. “These are wonderful!” he exclaimed. “Each one is special in its own right. Look at the detail on the dancer’s dress,” he said as he admired the Paoletti, “and the expression on this lady’s face.” He pointed at the housewife. He turned to the last two. “You can almost feel the heat of those flames. And the faces of these children – quite simply remarkable.”

For his part, Karl was utterly speechless. Aside from those few moments inside Jan’s darkened apartment when he had first laid eyes on the paintings after fifty years, he had not had a chance to stand back and fully admire them as he did now. And he knew that VandenBosch was right. They were remarkable, from their size, to their vibrant colors – amazingly well preserved – down to their detailed and intricate brushstrokes. They had meant little to him in Rakovník. Today was another story. Today they meant everything. And from the shadow of the dark hallway in the embassy building arose the presence of Marie and Victor. Standing in front of the paintings was a moment of victory for his entire family, and Karl wanted to savor it. You didn’t get everything, he thought silently of the war and Hitler’s reign of terror. You didn’t tear us apart as you tore apart so many others. This property, his family property, had eluded the Nazis first, and the Communists, at least for now, as well. It was a triumph.

Karl was so absorbed in staring at the paintings that he didn’t realize Richard had left him. When he finally came out of his daze, he saw Richard walking toward him down the long hallway, accompanied by another gentleman. He carried a sheet of paper in his hand.

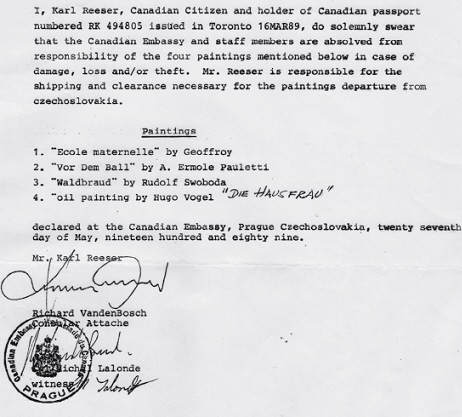

“This is Mr. Lalonde,” Richard began. “He’s a fellow Canadian, and a security officer here in the embassy.” Karl shook hands with the smiling young man. “I’ve asked him to witness this receipt acknowledging that we now have the paintings and that you will endeavor to find a way to get them out of the embassy and into Canada.”

Karl scanned the document. The receipt also released the embassy from any responsibility for the welfare of the paintings. Karl noted this, resolving once more to do everything in his power to get the paintings out of Czechoslovakia as soon as possible.

“I’m not planning on going anywhere in the near future,” Richard added. “But in case plans change, you should have this as evidence of your ownership of the paintings. Once the paper is signed and I’ve made a copy, I’ll drive you back to your hotel.”

Karl nodded, still absorbed in his memories. He signed the form which was then cosigned by Richard and witnessed by Lalonde. Before leaving, he snapped photographs of the paintings and then, with one more backward glance, he left the embassy.

Outside the InterContinental Hotel the two men turned to face one another. “I know I’ve got a lot of work to do before the paintings are out of the country,” Karl began, haltingly. “But it already feels as if they are free.”

Richard nodded. “This is a great moment for me as well,” he replied. “To know that I am a small part of the recovery of this art gives me a great sense of satisfaction.”

“I know I’ve said this before, but this would not have been possible without you.” Richard silenced him with a wave of his hand. Karl took a deep breath. “I will be in touch. As soon as I have any information regarding the transport of the paintings, I will let you know.”

“We’ll keep them safe until then,” Richard replied. “You can be sure of that.”

The two men shook hands warmly. Karl looked deep into the vice consul’s eyes, trusting what he saw – the honesty and integrity. He felt an intense solidarity with this man who, only days earlier, had been a complete stranger. It was hard to express the full extent of the appreciation he already had for everything Richard VandenBosch had done. Karl climbed out of the car. He watched it disappear from sight, and then turned to enter the hotel. People stared as the bellman held open the door. In his arms, Karl still carried the crumpled sheets and blankets that he had taken from Jan Pekárek’s bed to cushion the paintings. He planned to return them to Jan later that day. It was an enormous bundle, making it difficult to get through the door, and turning a few heads. Karl lowered his eyes, suddenly self-conscious, and focused on getting to the elevator as quickly as possible.

When he entered his hotel room, he picked up the telephone to call Phyllis in Canada. “My work is done here,” he said. “My flight leaves on Monday, so I will be home in a couple of days.”

This time, the relief in her voice was palpable. “I can’t wait to see you,” she said. “Is everything okay?”

“It’s more than okay,” Karl replied. “It’s perfect!”

It was only after Karl had locked the door to his suite and sunk down onto his bed that the full impact of the events of the previous few days began to sink in. “The paintings are safe!” He repeated this mantra over and over. And, while they were still technically inside Communist Czechoslovakia, they were on Canadian soil. And even though he had no idea at that time how he was going to get the paintings out of this country and into Canada, he knew that he had surmounted one enormous hurdle. Along with the exhilaration of having reclaimed the paintings, Karl also realized how exhausted he was. He had not allowed himself a moment to let down his guard, and the strain of having plotted and planned for the delivery of the paintings had left him drained, emotionally and physically. He lay his head down on the bed, thinking he would rest for a few minutes, and was instantly asleep.

As he lay there, dreaming about the day he would be able to enjoy the paintings from within his own home in Toronto, there was a sudden sharp rap at the door of his hotel room. Karl bolted awake. How long had he been sleeping? A few minutes? Several hours? A second sharp knock and Karl felt his mouth go dry and his heart begin to pound uncontrollably. His immediate thought was that he and the paintings had been discovered. All the pleasure and relief of the day left him. How arrogant on his part to relax, he thought, when he was still on Communist soil and still in some danger of being discovered.

When the knocking began for the third time, Karl stood up and cautiously approached the door. Blood pulsed in his veins, sending flashes of heat up to his face. He opened it a crack and peered into the hallway only to see a housekeeper standing there staring back at him. “I’ve come to check the minibar,” she said. Karl let out the breath that he had been holding and chuckled out loud as he stood aside to let her enter, admonishing himself for his paranoia. He was safe and the paintings were safe. Still, there was much to do before he could rest completely.

As soon as the housekeeper left, Karl went back down to the lobby. This last disturbing event had decided something for him. He did not want to remain in the country for one minute more than he had to. Every glance, every knock at the door, every person he passed merely heightened the anxiety he was feeling. And in his current state of apprehension, it was better to get out as quickly as he could. His flight home was scheduled to depart on Monday afternoon. He was flying on Swissair, which only flew out of Prague on weekdays. Karl had chosen this flight over Czechoslovak Airlines, which flew from Prague on weekends, because he had balked at the thought of flying on a Communist airline. But now, he didn’t care how he flew. His only desire was to leave Prague as soon as possible.

There was a desk for the Czechoslovak Airlines in the lobby of the hotel, and a helpful attendant quickly rearranged Karl’s flight so that he could leave the next day. Satisfied and relieved, he returned to his room, though not before stopping at the concierge desk to pick up another copy of the newspaper, Rudé Právo. In his room, he settled back on his bed, promising himself he would spend a few minutes reading the paper before packing his belongings for the flight home.

The newspaper carried the usual array of fanatical Communist worker resolutions and pronouncements. Karl quickly scanned the articles, paying little attention to what was reported. One item of local news, however, caught his eye. A Czechoslovak Airline plane, en route from Prague to the spa town of Karlovy Vary, had been hijacked by an armed man several days earlier. In the scuffle on board, the hijacker had discharged his gun, piercing the hull of the plane. Had it not been for the skill of the pilot, the plane would have crashed. In the end, it landed safely and the man was arrested. The pilot was being hailed as a hero. Though this incident had ended well, it left Karl shaken and in doubt once more. He didn’t know what was worse, taking his chances by staying in Prague for a couple of extra days, or risking his life on a Czech plane! Neither alternative was appealing. But surely this incident was an omen, he thought. He went back down to the lobby where he transferred his airline ticket back to the Swissair flight leaving on Monday. Under the circumstances, perhaps it was better after all to travel safely back to Canada on an airline he trusted.

That afternoon, he delivered the sheets and blankets back to Jan Pekárek’s apartment. Then, armed with his camera, he spent the final two days in Prague wandering through the old part of the city. He crossed the Charles Bridge, stopping to rub the golden toe of the statue of St. John of Nepomuk. Legend had it that this action would bring luck, and Karl closed his eyes and wished with all his might to get himself and his paintings safely out of the country. He passed a large statue of Christ encircled with Hebrew letters. The text on the crucifix had been added in 1696, placed there as punishment for a Prague Jew who had been accused of debasing the Cross. The golden letters had always been a matter of controversy for Prague’s Jewish community. Karl’s walking journey took him past the Church of St.  * where Mozart was said to have played the organ.

* where Mozart was said to have played the organ.

The St. Vitus cathedral, inside the grounds of Prague Castle, were so massive that, up close, it was hard to get a clear perspective of them. The walls rose up as a sheer edifice, overwhelming and magnificent, blackened by years of wear and disrepair, scattered with gold carvings, menacing gargoyles, and imposing statues that seemed to defy their years. Karl also passed by the famous Astronomical Clock mounted on the Old Town City Hall. The dial of the clock represented the position of the sun and moon in the sky. The clock chimed on the hour, at which time the “Walk of the Apostles” – a parade of figures moving above and across the face of the clock – took place. Four figures flanked either side of the clock, and were also set in motion hourly. The figures symbolized four sins. One figure, looking in the mirror, represented vanity; a skeleton represented death; a turbaned Turk represented threats to Christianity; and the fourth statue, a Jew holding a bag of gold, represented greed or usury. Tourists happily snapped pictures of the colorful clock and its parade of figures, seemingly unaware of the meaning behind the sculptures. Karl joined them.

This old section of the city was under restoration, and despite the seeming lack of interest in refurbishing public buildings, there were signs that the once splendid architecture of Prague was being uncovered and renewed. This was the Prague that Karl remembered from his youth, and it did his heart good to see scaffolding against the marble and brick facades, and view the workers as they cleaned and repaired previously neglected segments of the city’s fine architecture. Tourists filled the streets, along with dozens of prostitutes openly soliciting customers. As Karl strolled through the winding cobblestone lanes, he pushed all thoughts of the paintings from his mind. He would have plenty to do and think about once he returned to Toronto. For now, he took as many photographs as he could, wanting to enjoy his final moments in Prague, and to do so without apprehension or preoccupation.

On Monday, Karl checked out of his hotel, but not before there was one final incident. As he approached the front desk to settle his bill, the desk clerk asked how he would be paying, with American cash or Czech crowns. Karl, who had exchanged dollars for crowns with his schoolmate, Miloš Nigrin, replied that he would pay with Czech currency. However, as he was pulling the bills from his wallet, the desk clerk asked him to produce his official receipt from a financial institution for the monetary exchange. Of course he had none. It was the final reminder that only government exchanges were valid. After a quick and curt negotiation with the desk clerk, Karl was able to settle his bill partly with American cash, and partly with his remaining Czech crowns. He caught a bus to the airport where he faced one last anxiety-ridden hurdlepassing through security.

“What was the purpose of your visit to our country?” the guard asked brusquely, as Karl relinquished his papers and willed himself to breathe deeply and slowly.

“My high school reunion,” he replied, briefly describing the events that had formed the alibi for his visit.

“And how was it?” the guard asked, smiling now, almost friendly.

“Wonderful,” Karl lied. With that, he collected his papers, boarded the plane and flew home to Toronto and to a welcome reunion with Phyllis.

Receipt from Jan Pekárek listing three of the paintings and then specifying that the fourth was the subject of legal proceedings between the familes.

A receipt from the Canadian Embassy acknowledging the presence of the four paintings.

* This is often used as a title of respect.

* Church of St. Nicholas