Toronto 1989

ON HIS RETURN, Karl dove into the task of trying to find a way to get the paintings out of the Canadian embassy in Prague and into Canada. It was a daunting proposition, and there were seemingly insurmountable obstacles at every turn. There was nothing fluid about the Czech laws. They were solid, sharp as a lethal knife, and unyielding. And while one could argue that there was a slight possibility that in relinquishing the paintings to the National Gallery and paying the tax, the government might agree to allow for their export, there was no way to know the outcome of this unless Karl openly came forward and acknowledged their existence. And once the paintings were known to the government, all control on Karl’s part would be lost.

On top of these legal certainties, Karl was also aware that any disclosure of the paintings might endanger Jan Pekárek who could be perceived as having already defied the government by harboring the paintings in the first place, and for having turned them over to Karl and not to Czech officials. And, as Karl had already resolved, he did not want to do anything to jeopardize Jan’s safety and that of his family.

As if all of this were not enough, Karl also knew that he could not disclose to the Czech government that the paintings were now being kept at the Canadian embassy. There was no question that the involvement of the embassy raised the profile of the paintings significantly. The secret police would likely be even more interested in them given that the embassy had thought them important enough to hide. Furthermore, there were possible implications for the embassy itself for having hidden the paintings. There could be consequences for the Canadian government and for those who had helped Karl in his mission – primarily Richard VandenBosch.

So there it was: a mountain of obstacles. Karl wished he could go back to Prague and carry the paintings out himself; find a way to conceal them in a case or crate. This would have been a compelling option, if it weren’t for the fact that they were so big – that and the knowledge that Phyllis would never allow him to do anything as risky as hiding the paintings in his luggage and sneaking them across the border.

For weeks, Karl tried to fashion one solution after another. Each possible alternative disintegrated in the face of the stumbling blocks. Karl rode a wave of conflicting feelings and thoughts. He was frustrated that the paintings were so close to finally being in his possession and yet were still just beyond his grasp. He was angry at a government that still seemed to haunt and stalk his family years after they had fled the country. He felt fearful that nothing would ever come of his efforts and the paintings would never be returned to him. And in the midst of this emotional torrent, he would think of his parents, who had never stopped fighting to get their family out of Czechoslovakia during the war – and particularly of his mother and her brave attempts to keep the paintings together and retrieve them. Buoyed by the memories of his parents’ strength and determination, he would once again resolve to find a way to recover the art.

“I know there has to be a way to do this; a solution somewhere in the midst of all of these barriers.” Karl voiced this one evening as he and Phyllis sat having dinner with Hana and Paul. The two couples socialized together on a weekly basis. Recently their conversations had focused on Karl’s trip to Prague and what to do about the paintings.

Hana shook her head. “I don’t know what to suggest,” she said. The truth was that Hana did not have the same burning desire to retrieve the art that Karl did. Even though she empathized with him and understood his longing, she had been largely indifferent upon discovering that the paintings had resurfaced in Prague. Perhaps it was because the events of the war and their family’s escape from Europe had happened when Hana was still quite young. Her life had been more fully formed in Canada after their escape. Any attachment to their home in Rakovník and all of their possessions there had faded soon after arriving here. She did not share Karl’s view that the paintings were a vindication of their mother’s endless efforts to reclaim their property in Prague. She had been only mildly interested in her mother’s attempts to retrieve the paintings years earlier. At any rate, she was at a loss as to how to help her brother.

“Your mother always talked about how wonderful it would be if the paintings could be returned to her – a restitution of sorts,” said Phyllis. Karl’s wife had been relieved beyond words to have him back safely. And while she empathized with his desire to regain the paintings, Phyllis’s great fear was that Karl was going to undertake another trip to Prague. His first trip there had caused Phyllis many sleepless nights. A second excursion would be her emotional undoing. And yet she knew that if her husband resolved to do something, there would be no stopping him.

“Perhaps you’ve not yet exhausted every legal avenue to get the paintings out.” Paul had been sitting quietly at the table watching the exchange take place, and now leaned forward to join the conversation. “Besides, you have no other choice but to follow the law.” Paul was typically a reserved and cautious man, sometimes even appearing to be distant and aloof. In reality, he was a man of complex emotional character. Like many survivors of the Holocaust, Paul was hesitant to talk about his painful survival history, and reluctant to be outspokenly Jewish in general.

Karl frowned. He was not surprised to hear his brother-in-law make this cautious statement about following the law. He shook his head emphatically. “At this point, I’m prepared to do anything to get the paintings back,” Karl declared. “I don’t care what’s involved. I’d beg, bribe, or steal them out of the country if I could find a way.” The four of them fell silent. It was inconceivable to Karl that there wasn’t an avenue open to him, legal or otherwise. “But clearly I can’t do this on my own,” he continued. “I wouldn’t know the first thing about smuggling. Besides, I need someone who understands the political situation in Czechoslovakia.”

“Someone who would know how to get around all those rules,” added Phyllis.

“Exactly!” Karl replied, enthusiastically. “And preferably someone who understands fine art – how to transport something as delicate as the paintings. I’d be willing to pay for someone or some company who could do all of that.”

“But even if you were to find such a person who was willing to be paid to bypass the laws, how would we ever ensure that they were in this to help us and not only themselves?” Hana posed this question and Paul nodded emphatically.

Karl stood from the table and paced anxiously across the dining room. “There must be something…there must be someone,” he muttered, as much to himself as to the others.

“What we really need is an honest smuggler,” Phyllis said, glancing up from her seat at the table.

Karl came to an abrupt stop, “Yes!” he said, nodding excitedly, “Someone who would be willing to go into the country and get the paintings out for us – but someone we could trust would bring the paintings back to us and not just abscond with them.”

No one replied until Hana laughed softly. “If only there were such a person,” she said.

Over the next few weeks, Karl made attempts to locate such a person. He began by extending his net of contacts and speaking to everyone he knew who might have a link to the art world in Canada and abroad. Political and legal contacts were next – those who might have dealings in Czechoslovakia or other Communist countries. When he had exhausted that list, he moved on to merchants who had conducted business abroad and were used to transporting goods. His research extended into the area of looted art in Europe during the Second World War, and he discovered that the Third Reich had, not surprisingly, amassed hundreds of thousands of valuable objects, including paintings and sculptures, from occupied nations. In 1943, the United Kingdom had joined with sixteen other United Nations countries to try to stop this plundering. A declaration was announced at that time making it clear that harboring property of this sort would not be tolerated. To support this, a set of non-binding principles was being developed that would assist individuals or their heirs who had lost art to come forward, identify their property, and then work toward achieving a just and fair resolution. Of course, the situation in Czechoslovakia was further complicated by the presence of the Communist government, which Karl knew would never adhere to these western principles.

Karl’s days began to follow a particular routine. He would rise early, walk the dog, and have breakfast with Phyllis. And then he would head off to do his research. He was a frequent visitor at the reference library where he poured over telephone books and newspapers from every country, trying to track down possible resources. He wrote letters to every promising contact and used the services of a small downtown Toronto company that had an answering machine and fax service available for a small fee. Step by step, Karl’s list of sources began to grow. With each contact he would begin by first asking for a lawful solution to his problem of retrieving the paintings. But when that avenue failed to yield positive results, he would quickly move on to asking if anyone might know a way to work around the law.

Several leads looked promising. There was a Czech expat, whom Karl had met while purchasing a painting for his home. This man had traveled extensively, buying art at auction houses around the world. He had done a substantial amount of business in Western Europe and frequently arranged for the shipment of this art back to Canada. But after a lengthy conversation with him, Karl again realized that shipping goods of value from countries like France or Italy and trying to get art out of Czechoslovakia were two very different ventures.

Next, Karl discovered several companies that organized industrial fairs at international expositions. These companies would import and display machinery and other equipment for these trade shows. Karl wrote to each of them, setting out his situation and asking for their assistance. One by one, they responded with the same verdict: “We won’t touch this project without the Czech export stamp.” One company even responded with a lengthy fax that gave a detailed description of the steps that foreign diplomats must comply with in order to gain permission to have personal property exported. No one was immune from the scrutiny of the Czech government, and, after several months had passed, Karl realized that he was no further ahead in his efforts to regain his property.

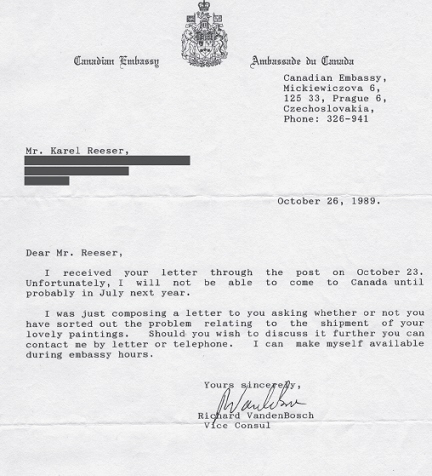

During all this time, Karl continued to have regular correspondence with Richard VandenBosch. In an early letter, Karl asked if Richard had any plans to return to Canada for a visit with his family, who resided outside of Guelph, Ontario. Karl hoped to be able to visit with him if he were planning such a trip. This would also make communication so much easier. In October 1989, VandenBosch responded, saying,

Dear Mr. Reeser,

I received your letter through the post on October 23. Unfortunately,

I will not be able to come to Canada until probably July next year.

I was just composing a letter to you asking whether or not you

have sorted out the problem relating to the shipment of your lovely

paintings. Should you wish to discuss it further you can contact me

by letter or telephone. I can make myself available during embassy

hours.

Yours sincerely,

Richard VandenBosch

Vice Consul

There were numerous letters exchanged between the two of them from May 1989 to March 1990. And over the course of this correspondence the relationship between Karl and Richard VandenBosch began to take on a whole new dimension. They were becoming friends – separated by continents, but linked nevertheless. Despite the continued formality of their greetings and salutations, their letters moved from reserved updates on Karl’s attempts to find a way to retrieve the paintings and Richard’s confirmation of these efforts, to private accounts of their lives and families. The change in tone in their letters was an unspoken acknowledgment that they had shared a personal adventure of sorts. Richard seemed to have almost as much of a stake in the paintings and their fate as Karl did. There was no doubt that he was invested in Karl and his family.

In a letter dated November 28, Richard told Karl that he and his family were planning to vacation that coming Christmas in England. He suggested that it would be lovely if Karl and Phyllis could join them. He wrote:

Just a quick note to say that I often to go Weiden, Passau, West Germany, for a quick relief from the Prague tension and I will be in England over the Christmas holidays. The embassy has my number if you require it. I would be happy to meet you around this place if you wish…

It was impossible for Karl to meet up with Richard in England. In his subsequent letter, he wrote:

Thank you for offering to meet me in England during the Christmas holidays. Aside from the fact that the time frame was just too close, I would not want to intrude at this time into what for you must be a much-needed respite from the recent tensions of Prague. I may take you up on your offer during the first half of next year, or else, wait for your anticipated visit to Canada in July…

In the letter of invitation, VandenBosch also told Karl that he had decided that, for the time being, he would hang the paintings in the embassy offices. They were so big and impressive that he thought they deserved to be displayed. Besides, he knew they would add something special to the walls of the embassy, which were quite devoid of artwork. In addition, Richard wanted to make sure that the paintings would not sustain any damage while at the embassy, and he thought that hanging them was the best way to preserve them. The painting of the children in the bathhouse was mounted on the wall of his office. Forest Fire was hung in the receptionist’s office. The housewife gazing at the sheet music went into Robert McRae’s office. The fourth painting, the Spanish dancer, was stored in an upstairs room of the embassy. Periodically, Richard would rotate the paintings so that everyone would have a chance to enjoy them. He wrote that the paintings were providing great pleasure for himself and his colleagues, though it would please him even more when he knew that the paintings were finally hanging on the walls of Karl’s home in Canada.

Karl was delighted with the news that the paintings were hanging in the embassy offices.

I read with much pleasure that two of my paintings are hanging in your offices.* At one time, all of the paintings had beautiful, ornately carved gilded frames. If there was some way of framing these paintings while they are in your custody, I would gladly assume the cost, and then perhaps all of them could be utilized to full advantage. But I would, of course, not want the paintings to leave the safety of the embassy.

I suppose that it comes across that the turn of events relative to these paintings has great meaning for me. It started fifty years ago when my mother hid them from the Nazis. Incredibly, two generations later, an honest grandson of the original custodian has surrendered them. The fact that now, half a century later, these paintings grace the Canadian embassy, is a sort of a triumph for me: made possible by your understanding and actions taken during the few hours I spent with you last May. As this year draws to a close, I want to express my admiration and appreciation for your role. I presume that Ambassador Mawhinney and First Secretary McRae had prior knowledge in this matter, and I would like you to express to them my sentiments and greetings.

With best wishes for 1990, sincerely,

Karl Reeser

Though the many letters that passed between Karl and Richard had a warm nature, they also all alluded to the increasing tension and political unrest in Prague. Indeed, the situation in all of the Soviet Bloc countries was undergoing a dramatic change in the fall of 1989. Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev was struggling with a faltering economy, the Iron Curtain was eroding, and countries on both sides of the divide were calling for reunification.

“It’s happening all over,” Karl proclaimed one night as he sat with Phyllis drinking tea and discussing these significant world events. “If someone like Andrei Sakharov can be elected to the new parliament of the Soviet Union, then anything is possible.” Karl was referring to the dissident and Nobel laureate who had once been exiled from the country for his political views. “And look at what’s happening in Czechoslovakia. Everyone thought that the student protests would end in violence, but instead of sending in the tanks, the Communists are resigning. They’re even beginning to remove the barbed wire from the border with West Germany and Austria. It’s being hailed as the most peaceful revolution in history.”

“Let’s just wait and see,” Phyllis replied. Her voice was soft and somber. “Everyone believes that Václav Havel will become the next president, but he has his work cut out for him.” The noted playwright and dissident was being hailed as the future savior of a new democratic Czechoslovakia, but Phyllis’s view remained dark. “The country has lived in a fog of lies and meaningless rhetoric for decades. Communism has ruined the nation, quite apart from the extinction of civil liberties. The spirit of the citizens has been broken, industry is a mess, and technology is archaic. And then there’s the history of harassment. The secret police aren’t going to disappear just because the government has a new name.”

Karl interjected. “You’re right, of course. But it is a beginning – something to be optimistic about, wouldn’t you agree with that?”

Phyllis was quiet and eventually she rose, cleared the dishes, and left the room. But when Karl read of the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, he was even more optimistic about the possibility of change within his former homeland. That wall, which had stood as a physical and political symbol of oppression for thirty years, was opened up in a single night. The events which followed in Czechoslovakia were immediate and rapid. On November 17, more than fifty thousand students who were part of the Socialist Union of Youth turned out for a mass demonstration. The date was significant, as it marked the fiftieth anniversary of the murder of a Czech student, Jan Opletal, by Nazi soldiers during the Second World War. His death was commemorated annually in what was known as International Students’ Day. On that day in 1989, armed forces were on alert for what they anticipated would be an all-out riot. The students, and others who joined them, marched toward Wenceslas Square, where they were surrounded and eventually beaten by riot police. But the regime’s decision to use force against the protesters would have consequences, and this demonstration was only the beginning. Within days, more peaceful marches were held and the numbers of protesters grew to over two hundred thousand. On November 27, a general strike was called, with workers demanding a new government. Millions of Czechs and Slovaks walked off their jobs. Under this intense pressure, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia announced that it would relinquish power and step down. Gustáv Husák resigned on December 10, and on December 29, 1989, Václav Havel became the new president of Czechoslovakia. His political party, known as the Civic Forum, became a voice for revolutionary change in the country. In his “Declaration of the Civic Forum” speech, Havel proclaimed:

The situation is open now, there are many opportunities before us, and we have only two certainties.

The first is the certainty that there is no return to the previous totalitarian system of government, which led our country to the brink of an absolute spiritual, moral, political, economic, and ecological crisis.

Our second certainty is that we want to live in a free, democratic, and prosperous Czechoslovakia, which must return to Europe, and that we will never abandon this ideal, no matter what transpires in these next few days.11

This overthrow of the Communist government became known as the Velvet Revolution, one that had miraculously happened quickly and without bloodshed. Graffiti appeared on the walls of buildings in Prague that said “Poland, ten years; Hungary, ten months; East Germany, ten weeks; Czechoslovakia, ten days.”12

In Prague, a dissident was hurriedly released from jail so he could join the cabinet as the minister responsible for, among other things, the secret police! The unattainable was being achieved, and Karl watched these events unfold with great anticipation. A revolution was taking place inside his former homeland, and a peaceful one at that. A new democratic government was on the horizon, and with it, the promise of a complete restructuring of the political and social agenda.

Surely this would also eventually result in a lifting of the regulations governing the export of goods. Perhaps if he just waited a little longer, the paintings might become accessible to him without all this scheming and planning. More than fifty years had passed since his family had had possession of the paintings. Surely Karl could wait a few more months. How jubilant it would have made his parents to think that the country might be opening up now, providing a route to regaining their property as it woke from its long coma.

But any hope of an immediate change in Czechoslovakia’s policy of investigating and persecuting its citizens faded when Karl became suspicious that his mail was being opened and inspected. A letter which had been sent from his old friend, Miloš Nigrin, arrived with tape sloppily applied across the seal. And Miloš subsequently wrote to say that he too had received a letter from Karl which had been delivered opened. When Miloš went to the post office to casually inquire about this, he was told that the letter had indeed been inspected by the secret police. This sent Karl into a frenzy of worry. “No wonder everyone is paranoid there,” he fumed bitterly to Phyllis as he held up the letter from Miloš, the evidence of what he believed to be police tampering. “Each time the citizens think they can taste freedom, the Communist goons remind them that they’re still being watched – we’re all being watched.” His voice rose and shook with a sudden ferocity. Perhaps Phyllis had been right to be so circumspect about the news emerging from the country. Change would not happen so quickly.

“But what do you think it means?” Phyllis asked. “Are they really suspicious of you or is this just what they do to everyone?”

“Who knows?” Karl replied, shaking his head. “I’m most concerned about Miloš. He has nothing to do with this; he doesn’t even really know why I was in Prague in the first place. I don’t want him implicated in something that is my affair and mine alone. But if State Security is indeed suspicious of the business I was conducting while in Prague, then Miloš could be targeted just for having been seen with me when I was there. It’s absurd!”

“And what about Jan?”

“Of course! He’s just as vulnerable. More so!” Karl squeezed his eyes shut and shook his head, more convinced than ever that someone must have become suspicious when they saw him, Jan, and Richard carry the paintings out of Jan’s apartment and into the waiting van – maybe the old man who had poked his head out the door of his flat, or the old women walking by on the street. They had appeared to be harmless, but no one, he reminded himself, no one could be trusted in a country that hunted for traitors and trained its citizens to do the same. And if Jan were arrested, it would be a short path to the whereabouts of the paintings. Ranting didn’t help, Karl knew. But he felt so powerless and deceived. What good was a new democratic government when, at the end of the day, it still resorted to its old tricks? A wolf in sheep’s clothing, that’s what you could expect from Czechoslovakia, old or new.

Karl became increasingly concerned about the frank correspondence he had been having with Richard VandenBosch, in which they had both openly discussed the paintings, their current whereabouts, and the plans for their future. When he received a letter from Richard that appeared to have been opened and then resealed with tape, he knew with certainty that his mail was being scrutinized. His subsequent letter to VandenBosch cautioned him as follows:

Many thanks for your letter…which by the way arrived resealed with transparent tape. I mention this, because I experienced repeated instances of non-delivery of mail to two of the persons with whom I met while I was in Prague last May. That is one of the reasons why I would like to meet with you privately, even if it must wait until you visit Canada in July of next year. If by chance you may be somewhere in Central Europe before then, I could probably arrange to meet you there…

Now, more than ever he needed to get the paintings out of the country. But a plan still eluded him. He even asked VandenBosch for help in locating someone to assist him. Richard replied by saying:

I must apologize for my tardy reply to you in recommending any lawyers. The Canadian embassy from time to time uses the lawyers at Advokatni Poradna 1, Narodni 32 (dum Chicago), Prague 1… Unfortunately, we cannot attest to their competency in this field. I hope this will be of some help…

This did not appear promising. But that same letter contained some news which was even more distressing. In it, VandenBosch indicated that, in light of the changing political scene in Czechoslovakia and elsewhere, the embassy would be undergoing a massive staff turnover in the coming months. He personally would remain in Prague for another year. But the changeover in staff would probably necessitate the removal of the paintings from the embassy and their relocation elsewhere. His letter had a tenor of urgency when he wrote:

On another note, have you had any success in obtaining exit permission for your paintings? The staff will be changed over this summer and will probably result in the removal of your paintings elsewhere for storage. I would be somewhat relieved if they could be in your possession before this summer. I shall be here for a further year and, if possible, shall be available to assist you…

“The paper says that Prague citizens are popping champagne and dancing with joy on Wenceslas Square.”

Karl, Phyllis, Hana, and Paul had once more gathered for dinner in the Reeser home. Their conversation was filled with news of the changing political events in Czechoslovakia and other countries. Phyllis held a copy of the Toronto Star in her hands and was pointing to a column which declared:

Sirens wailed, horns honked and bells pealed…in Prague and other cities to mark a dramatic opposition victory that ended the Communists’ 41-year domination of the government.13

“The people there have been deprived of political expression for so long they don’t know what to do with themselves,” she said. “These are extraordinary events! The entire Communist party leadership structure has collapsed. And not just in Czechoslovakia. Gorbachev is signaling that he is willing to end the Communist party monopoly on power in the Soviet Union. Hungary and even Bulgaria are hinting at free elections. Lithuania and Estonia will follow suit. You must admit, it sounds like a hopeful future.”

Hana nodded, though she remained silent.

Karl frowned. This time he was not being quite so optimistic. “I’m concerned about the men who will replace those who have resigned. The Communist party veterans are not going to walk away so easily. They’ll want a place in this new government. And, as you have suggested more than once, a Communist with a new title is still a Communist.”

He spat the words out and then went on to detail the letters that he and Richard VandenBosch were exchanging. “With the fall of the Communist government, the entire Canadian embassy is restructuring. The paintings may have to be moved elsewhere. I still don’t trust that a new government will be any more likely to open up the borders to allow valuable property to be exported. And I’m terrified that if our artwork is moved, it will be exposed in public and subject to investigation.” He went on to describe how his recent letters had been opened and likely inspected by whatever was left of the secret police. “Nothing is changing quickly, in spite of what we read of free and open elections.”

There was a long moment of silence at the table as each person digested this pronouncement. Finally, Karl spoke. “At least VandenBosch is getting to enjoy the paintings. I just wish they were hanging on our walls.” Another long pause, and then, once again, he voiced the need for an honest smuggler.

At this, Hana sat up in her chair. “Oh, how could I have forgotten to tell you this,” she said, suddenly animated. Hana explained that she had told some Czech friends about the paintings and the problems her family was facing getting them out of Prague. “Someone mentioned a contact, a man who has brought art from Czechoslovakia to Canada on several occasions.”

Karl was out of his seat in a flash. “Who is he?” he demanded. “How do I get in touch with him?”

“I’ll find out his name and how to contact him,” Hana replied. “My friend was a bit vague with the information, but I’ll follow up.”

A day later, Hana telephoned Karl. “His name is Theofil Krái,” she said. “That’s all I have — a name and not much information. But you won’t believe this. He lives here in Toronto and practically around the corner from your house!”

One of the many letters sent from Richard VandenBosch in Prague to Karl in Toronto.

* VandenBosch later confirmed that three paintings were hanging in the embassy offices.