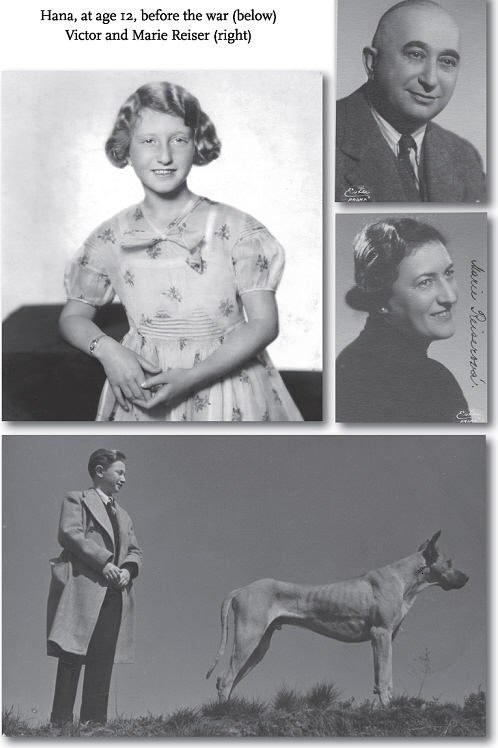

CHAPTER ONE

Rakovník, Czechoslovakia, August 1937

IT WAS EARLY MORNING in the Reiser household. The sun crept up over the wide window ledge and floated into the second floor bedroom, casting a warm glow over sixteen-year-old Karl’s face as he slept. Noises of an awakening city followed. Shopkeepers released their awnings and pulled their stalls into place on the street below. Cars honked their horns in the busy square, their engines sputtering and popping as they drove by. Voices blended into a fusion of salutations and acknowledgments. The town of Rakovník in western Czechoslovakia was coming alive. Karl resisted the urge to join in and nestled into his blankets. He had been dreaming, and for a moment he pushed his mind to go back to that place just before awakening, where fantasy and reality merged. He had imagined himself bicycling through the countryside, deep into the woods, and then past fields of sunflowers en route to the river. School had broken up for the summer vacation and Karl had dreamed of lazy adventures and swims in fresh water so cold it took his breath away.

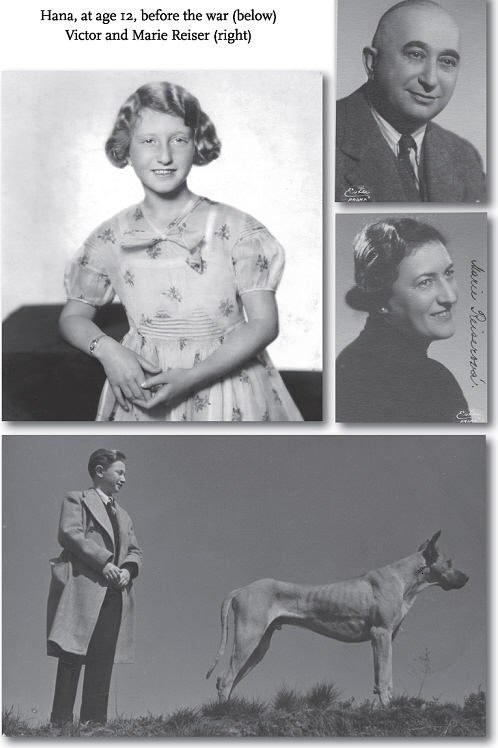

The sounds from the street below his window were daily background music to Karl’s mornings, lulling him in and out of wakefulness. But on this morning something was different, interfering with the peacefulness of the approaching day. This wasn’t a sound, but a feeling, and it was strangely wet and sloppy! The dream forgotten, Karl rolled over in bed to see the panting face of Lord, his Great Dane, licking his hand and urging him to get up. Lord’s ears perked up at the sign of movement from his young owner.

Karl reached over to pat his dog, wondering briefly how Lord had managed to get into his room, past the watchful eyes of his mother. She would not be pleased to discover the dog here. Karl groaned and rolled back over, burying himself under the covers and trying to find that quiet place where sleep might once again claim him. But Lord would have none of it. He nuzzled the bed sheets, and gave a low raspy growl.

“Shhhh,” Karl commanded, rolling over once more. “Don’t you realize you’ll be banished from the house forever?” He reached over to scratch affectionately behind Lord’s ear. Everyone, his parents included, had thought it was brazen of him to name his dog “Lord.” But Karl had insisted on the name for this majestic creature. Lord sighed and rested his head on Karl’s bed. “Those pleading eyes won’t help you,” Karl whispered. “And mother will think I’m the one who let you in here.” How did Lord get past everyone in the first place? he wondered again.

Too late to go back to sleep, Karl realized. By now, his father would be up and in his office. Mother would be busy with the household and the family servants. Perhaps she was already supervising the preparation of that evening’s dinner. With luck, there would be a roast chicken with houskové knedlíky – bread dumplings – and  – crepes filled with jam – for dessert. Any minute now, Leila, his nanny, would knock softly at Karl’s bedroom door, telling him it was time to get up and come downstairs for breakfast. Perhaps Leila would protect him from his mother’s displeasure at discovering Lord in his bedroom. Leila Adrian had been with the family for years, and she had a soft spot for young Karl, whom she had practically raised from birth. Leila was from Sudetenland, the northern part of Czechoslovakia, a region that was home to an ethnic German population that had clashed with the Czechs over the years. But that was politics, and Leila didn’t care about that. She was ferociously loyal to this family, and her love had grown over her years of devoted service. She had never married and had no children. And while she would occasionally visit her sister in their hometown of Ústí nad Labem, the Reiser family was her true family. Karl knew Leila would try to defend him, but, more than likely, he and the dog were going to be in trouble this morning.

– crepes filled with jam – for dessert. Any minute now, Leila, his nanny, would knock softly at Karl’s bedroom door, telling him it was time to get up and come downstairs for breakfast. Perhaps Leila would protect him from his mother’s displeasure at discovering Lord in his bedroom. Leila Adrian had been with the family for years, and she had a soft spot for young Karl, whom she had practically raised from birth. Leila was from Sudetenland, the northern part of Czechoslovakia, a region that was home to an ethnic German population that had clashed with the Czechs over the years. But that was politics, and Leila didn’t care about that. She was ferociously loyal to this family, and her love had grown over her years of devoted service. She had never married and had no children. And while she would occasionally visit her sister in their hometown of Ústí nad Labem, the Reiser family was her true family. Karl knew Leila would try to defend him, but, more than likely, he and the dog were going to be in trouble this morning.

Another sound drifted up from the downstairs salon. Karl listened for a moment, hearing his parents’ voices rise and fall. He sensed some kind of alarm in their tone, and wondered briefly what his father was doing here when normally he would be in his office by this time. As a commodities broker, Father bought future grain crops from large farms in the area and sold these contracts to domestic and foreign markets. His company, A. Reiser, had been started by Karl’s grandfather Abraham. But Karl’s father had taken ownership at a young age, achieving great success and making his family one of the wealthiest in Rakovník. His offices were on the ground floor of the house, though he was often away on business.

“Come, Lord,” Karl finally said. “Let’s see what’s going on. Maybe I can sneak you past Mother without her noticing.” Lord snorted an acknowledgment and Karl rolled out of bed. He paused briefly to look at his reflection in the mirror above his bookshelf. His long, thin face and lanky physique reflected back. Like his father, Karl had a strong, angular nose. His sparkling eyes were a gift from his mother. He dressed quickly, ran a brush through his thick hair – the red hair and freckles also came from his father’s side of the family – and sprinted down the long staircase to the main floor. Lord followed, sending the Oriental carpets flying as he rounded the corner at the bottom of the stairs. But Karl needn’t have worried about his dog. When he entered the living room, his parents were deep in discussion, oblivious to all other activity.

“But, Victor, who could have done such a thing?” his mother asked. She paced anxiously back and forth.

Karl’s father shook his head. “Calm down, Marie. I’m sure it’s nothing. Children. Pranksters. That’s all. You mustn’t be so upset. There’s nothing personal in this.”

“Nothing personal! How can you say it’s nothing? We’ve never been targeted like this. It’s shocking, disgusting! We are fully assimilated in this town.”

This was an understatement. There were only thirty Jewish families who lived in this town of about thirty thousand people. And though the Jewish families all knew one another, Karl and his family only saw them a couple of times a year when they met at the big synagogue on Vysoká Street for the High Holidays. These events, and the occasional Yiddish word that Victor would drop into a conversation, were the only indications of the family’s Jewish background. First and foremost, the Reisers thought of themselves as Czechs – loyal citizens of their country.

Karl had rarely seen his mother this agitated. An attractive and cultured woman, she was typically reserved and in control. But not this morning. She wrung her hands and tugged nervously at the collar of her lace blouse. Father eased his ample bulk out of an armchair and took his wife by the hand.

“And that’s why you mustn’t worry,” he said. “This is a minor incident. But I’ve called the police to report it, just to be on the safe side. Please, calm down.”

The telephone rang shrilly and Father moved to answer it. He responded in clipped sentences to the caller; perhaps a police official, Karl guessed. Mother continued to pace, ignoring Karl, who had taken a seat in the corner of the living room next to his sister, Hana. Leila stood in another corner of the room, casting nervous glances at her two young charges. Their nanny was grandmotherly in appearance, a small, gray-haired, kind woman. She too looked more troubled than Karl could ever remember.

Karl leaned over to his sister and whispered, “What’s going on?”

Hana was usually talkative, but not so this morning. She sat perched on the edge of her chair, holding her dog, Dolinka, in her lap and stroking its head. Hana shrugged. “Go outside and see for yourself,” she replied. Hana was four years younger than Karl. They were as close as a brother and sister could be, though Karl sensed at times that Hana thought of him as the favorite – the older of the two and the only boy in the family.

Karl walked out the door and onto the streets of Rakovník. The family’s three-storey house was in the main part of town, facing Husovo  the central square. Their property consisted of three buildings side by side. The first contained the grain warehouse for his father’s business, and the second housed several servants and employees. The last house on the corner was the family home. Theirs was one of several impressive buildings in this section of the city.

the central square. Their property consisted of three buildings side by side. The first contained the grain warehouse for his father’s business, and the second housed several servants and employees. The last house on the corner was the family home. Theirs was one of several impressive buildings in this section of the city.

By now, the main square was full of people and cars, everyone rushing about their business. Karl walked a few paces from his home and then turned around. He sucked in his breath at the sight that greeted him. In bold, white letters, the word  – Czech for Jew – had been painted across the brick wall of the house. The thick letters stood out on the street, emblazoned across the face of their home, their intent unmistakably menacing. Karl was not one for emotional outbursts. But this time was different. This time, he was overwhelmed with contempt for whoever had committed this crime. He stood rooted to the spot, his face flushed, his chest pounding.

– Czech for Jew – had been painted across the brick wall of the house. The thick letters stood out on the street, emblazoned across the face of their home, their intent unmistakably menacing. Karl was not one for emotional outbursts. But this time was different. This time, he was overwhelmed with contempt for whoever had committed this crime. He stood rooted to the spot, his face flushed, his chest pounding.

There was no such thing as hiding your Jewish identity in a town as small as Rakovník. You were saddled with it within a country where anti-Semitism had deep roots. In 1541, during the Habsburg dynasty, there had been a complete expulsion of the Jewish population. Over the centuries, the Jewish ghetto in Prague had been burned to the ground on several occasions, forcing Jews to rebuild their community each time. Even though his family thought of themselves as fully integrated into the Rakovník community, Karl was often bullied by his schoolmates. Not only were the Reisers Jewish, they were wealthy to boot, making Karl an easy target. As a child he frequently had been followed to school and taunted by the other children. “Hey  , did you fall asleep under a strainer?” they teased, suggesting that the sun had passed through a sieve to create the pattern of red freckles that lay across his nose and cheeks. He hated the reference, and felt self-conscious about his appearance. Nothing seemed worse than being a red-haired, freckle-faced Jewish boy living in a small town in Eastern Europe in the 1930s.

, did you fall asleep under a strainer?” they teased, suggesting that the sun had passed through a sieve to create the pattern of red freckles that lay across his nose and cheeks. He hated the reference, and felt self-conscious about his appearance. Nothing seemed worse than being a red-haired, freckle-faced Jewish boy living in a small town in Eastern Europe in the 1930s.

The worst assault had happened a year earlier when Karl was walking home from school. He could hear them approaching from behind – several boys, thugs who attended his school. But this time, the taunts were louder and more menacing than before.

“ , do Palestiny!” – Jew, go to Palestine! – one boy shouted, as Karl glanced over his shoulder and quickened his pace, anxious to get to the safety of his house. Though he was tall and muscular, Karl was not athletic, and certainly not a fighter. He would be no match for these tougher boys. The footsteps behind him came closer and then a thick, meaty hand reached out and grabbed Karl by the shoulder, spinning him around. It was over in seconds. Karl lay on the ground doubled over as the boys laughed easily and moved on. He limped home and spent the evening nursing the painful bruises on his stomach and the welts across his arms. He hid the marks from his parents, who would have been outraged by the attack. Eventually, Karl put it behind him.

, do Palestiny!” – Jew, go to Palestine! – one boy shouted, as Karl glanced over his shoulder and quickened his pace, anxious to get to the safety of his house. Though he was tall and muscular, Karl was not athletic, and certainly not a fighter. He would be no match for these tougher boys. The footsteps behind him came closer and then a thick, meaty hand reached out and grabbed Karl by the shoulder, spinning him around. It was over in seconds. Karl lay on the ground doubled over as the boys laughed easily and moved on. He limped home and spent the evening nursing the painful bruises on his stomach and the welts across his arms. He hid the marks from his parents, who would have been outraged by the attack. Eventually, Karl put it behind him.

There had been other beatings, but each time he would shake them off and let the incidents pass. And, relatively speaking, he knew that these confrontations were minor, not at all like the real dangers that existed these days in other countries where Jews were being systematically targeted. Adolf Hitler’s name had been spoken with disdain in Karl’s home for years. “A madman,” his father often said. “He’ll never last.” And yet the preceding years had seen the steady rise of anti-Semitic laws in Germany. With the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, Jews had lost their status as legal citizens there. They could no longer hold public office, and were barred from various professions and occupations.

But it seemed inconceivable that the harsh measures being implemented in Germany would ever come to Karl’s homeland. Tomáš Masaryk, their country’s beloved previous president, would never have allowed the Jews of Czechoslovakia to be targeted in that way. He respected the worth and dignity of all people, regardless of religion. And his successor, Edvard Beneš, appeared to rule with the same spirit of liberalism. Despite the hostility toward Jews that had marked the history of the Czech lands, both of these leaders expounded a democratic political philosophy that kept anti-Semitism in check. Karl could handle those occasional beatings by local thugs. However, this was an attack on his home, on his family; this was much more serious. As he stood staring at the graffiti on the wall, Karl’s mind was so preoccupied that he didn’t notice his father, who had come out of the house to join him on the sidewalk.

“In this country, I’m afraid they think they can smell a Jew. Anti-Semitism is bred here, and singling us out is sport,” his father said, breaking Karl’s concentration. It was unlike his father to speak so plainly about the centuries of political and social discrimination toward Jewish people. Usually he shrugged the history off. “History and reality are two different entities,” Victor had been fond of saying. Today, the two seemed to merge in his frank acknowledgment, taking Karl aback. “The police will do nothing about this,” his father added, gesturing toward the paint that had dripped down onto the sidewalk, leaving a line of small white puddles like stars dotting a dark sky. “They say it’s probably just some kids playing.”

“And you?” Karl asked. “What do you think?”

Once again, his father retreated to a place where he seemed willing to dismiss the vandalism. “I’m sure it’s nothing,” he said with a shrug. “Kalina, come here and help clean this off,” Father called to his chauffeur, who stood awkwardly to one side. By now there was a crowd of onlookers gathering in front of the house. “We’re not here to create a spectacle for everyone.” Kalina nodded and ran to get supplies from the garage. When he returned, Karl stepped forward to assist him.

“What do you think of this?” Karl asked as he and the chauffeur began to scrub at the paint that covered the wall.

“It’s a sign,” Kalina replied, glancing nervously at the sky and then shaking his head. Only in his early thirties, Kalina seemed much older, due in part to his many superstitions. He would spit three times if he passed a nun on the road, or if a black cat crossed in front of the car while he was driving. Karl was amused by the assortment of rituals and routines that controlled Kalina’s life. Still, Kalina was a loyal employee, and had secretly taught Karl to drive, well before the legal age. Once a year, the chauffeur would perform a general maintenance of the family automobile. He would disassemble the engine, clean the parts, and then reassemble it. Karl was fascinated with the mechanical working of the car and eagerly followed Kalina around like a puppy, lapping up as much information as he possibly could.

“The Germans are going to take over the country. Mark my words,” Kalina continued brusquely as he rolled up his sleeves and began to scrub the wall with sweeping brush strokes. The muscles stood out on his burly arms and sweat glistened on his forehead. But Kalina was an inconsistent forecaster, one month raging about a possible German invasion and the next month equally adamant about a Russian takeover.

With the help of strong ammonia and several steel brushes, the paint was removed in no time. But even after all traces of the graffiti were gone, Karl still felt uneasy. He was putting the pails and brushes away just as Kalina brought the car around for his father.

Father eased himself into the back seat of the black Peugeot and rolled down the window. “Karl,” he called to his son. “I have to see a client today. Go and look after your mother. She’s more worried about this than she ought to be.” With that, he gestured to the chauffeur and the car moved forward, leaving Karl alone on the street.

He glanced again at the house. Should Mother be so worried? he wondered. Shouldn’t father be more worried?

“Such a terrible thing,” Leila cried as Karl reentered the house. She spoke in German, the language in which she had been raised and the one she had taught to Karl and Hana. Leila clasped and unclasped her hands, shaking her head, and gathering her apron into a knot. “Who would do such a thing to this family?”

Leila wasn’t helping the situation, Karl thought. She was merely adding fuel to the frenzy of worry that gripped the household. He needed to escape the overheated city and his agitated family. He walked out the door, grabbed his bicycle from the garage, and rode quickly out of town and toward the pond. A long ride and swim would make him feel better.

Karl wound his way through the streets, passing the town hall, the brewery, the library, and the theater. His journey took him past the old synagogue with its twin Roman towers and matching minarets. A large stone Star of David adorned the archway over the double doors at its entrance, surrounded by stucco ornaments and gilded windows. The building dated back to 1763, and its interior always felt dark and slightly mysterious to Karl. The presiding rabbi did not live in town. He came in from Saatz* to celebrate the High Holidays and to give Jewish instruction to young boys. Karl often skipped the monthly classes. He had had a bar mitzvah of sorts, just a small service in the rabbi’s study, attended by his parents. It was a rite of passage that meant little to Karl or his family.

Close to the synagogue was the Jewish cemetery where marble and granite stones were engraved with Stars of David, crowns, and hand symbols. Here the memories were powerful. As a small boy, Karl had walked here with his father almost every Sunday to visit the graves of his grandparents. Before entering, Victor would remove a handkerchief from his pocket, tie a knot in each of the four corners, and place this makeshift skull cap on Karl’s head. Karl would place pebbles on the gravestones of his grandparents, following the biblical practice of marking graves with a pile of stones. He never fully understood what this ritual meant, though he knew it was a sign of love and respect.

In the distance, Karl could hardly miss the splendor of the lofty High Gate, which dominated the landscape. Everyone in town took pride in this majestic landmark. Built in 1517, the High Gate was really a tower constructed of rough stone and mortar in an almost perfect square. Jutting out from each of the building’s three levels, stone gutters shaped like pigs, frogs, and knights channeled water from the roof. Rakovník’s coat of arms had been carved prominently above the archway at the entrance.

Karl left the town behind him and rode south along the river Berounka, passing deep woods interspersed with large, sun-soaked meadows. Fifty kilometers to the east lay the capital city of Prague. Karl’s father did business there on an almost weekly basis, chauffeured by Kalina across the intersections of roads and railways, undulating hills and flat fields. Occasionally, Karl had joined his father on these trips. Though he reveled in the bustle of the big city, today he was grateful for the tranquility of the countryside.

The pond was quiet, just the way he had hoped it would be on this warm summer day. Karl enjoyed his time alone. He had few friends and tended to keep to himself. Perhaps it was the casual anti-Semitism that prevailed. Even the teachers couldn’t hide their contempt for the few Jewish students at the school. When teaching a lesson one day, Mr. Ulrich, the geography teacher, had posed a question and commented, “Even the Jews should be smart enough to know this.”

There was one Christian boy with whom Karl was friendly, Miloš Nigrin, the son of the local druggist. Miloš never joined in when others taunted Karl. He was a frequent guest at the Reiser dinner table and the two boys often cycled together. Karl’s other friend was George Popper, the only other Jewish boy at the school and a year ahead of Karl.

But today, Karl was relieved and grateful that none of his fellow students were at the pond. He didn’t want conversation; he certainly didn’t want anyone to interrogate him about the graffiti – and by now word might have spread. He even wondered if some might doubt the incident had ever happened, or worse, might use it as an excuse for further assaults upon his family. Either way, all Karl wanted was peace and seclusion. In those moments of solitude, he could slip out of himself and reflect more clearly on events.

The pond was his favorite retreat. The water here was deep and clean, and the surrounding fields provided an inviting area to picnic and relax with friends and family. Flanking the field were tall pine trees that grew in a tight formation. Sparrows and robins nestled atop the swaying branches and sang their endless symphony. Each year, a competition was held here. Those who swam three times around the pond and jumped off the tall wooden diving tower at one end were awarded with flowers.

Karl was a strong and natural swimmer. He dropped his bicycle in the tall grass, stripped down to his bathing trunks, and dove in. The water was cool and refreshing. Each stroke around the perimeter of the swimming pond seemed to calm him. His arms cut silently and efficiently through the water, propelling him forward and clearing his mind.

By the time he returned home, the heat of the day had begun to recede; he was feeling refreshed and had placed the vandalism in the back of his mind. It was just another stupid kid in town doing something cowardly, Karl thought. And we’re the easy target. But when Father walked in at the end of the day, the conversation about the graffiti resumed and within minutes the good feeling from the swim was gone.

“We’re deluding ourselves if we think this is nothing,” his mother ranted, picking up where she had left off that morning. “Look at what’s happening in Germany.”

“Honestly, Marie. You’re blowing this out of proportion,” Victor replied, removing a silk handkerchief from his pocket and wiping his brow and balding head. Sweat poured from his red face. “Czechoslovakia is not Germany and it never will be! We’re a democracy. Czechs would never tolerate having the Nazis and their rules here.” Like so many others, Karl’s father held fast to the belief that if Germany threatened to invade, Britain and France would come to Czechoslovakia’s aid.

“But, Victor, how do you know that?” Mother was pacing, moving across the floor of the salon like a tiger striding back and forth in its cage. Strands of hair from her perfectly coifed bun had loosened and floated across her flushed cheeks and forehead. Her brow was furrowed and her mouth was drawn in a tight, determined line. “Germany used to be a democracy, and now the Germans are rallying behind Hitler,” she declared. “There is no protection for Jews under the law in Germany, none whatsoever.”

Victor was equally adamant. “We are more Czech than Jewish,” he insisted.

Karl watched this exchange from his chair in the corner of the room. As his eyes moved back and forth from his mother to his father, he imagined he could see their arguments flying across the room like a ping pong ball from one of the tournaments he had played in at school. As always, he was pensive during these discussions, weighing what his parents had to say, and wondering who was more right. He had listened to his parents argue about the political situation in their country many times. Mother was typically negative and apprehensive during these exchanges, while Father was quick to placate her and neutralize her anxiety.

“It’s as if it’s open season on Jews in Germany,” mumbled Marie, oblivious to her husband’s comments. “It seems that with his promise of prosperity for all German citizens, people are quick to overlook Hitler’s darker side.”

“In this country it’s different. There are still many who will stand up for their Jewish friends and neighbors,” Victor insisted.

“You’re blind, Victor,” Marie finally said, shaking her head. “Czechoslovakia will not escape Hitler’s wrath. We should think about leaving,” she announced suddenly.

Karl’s eyes shot up. This was a first. Mother was actually suggesting that the family run from their country.

“Ridiculous!” snapped his father. “There is no reason to leave. Besides, Jews are coming here to Czechoslovakia for their safety.”

“It’s true!” Karl interjected from his spot on the sidelines. “I read in the newspaper that there are Jews from Austria, Hungary, and Germany who have been flooding across our borders to escape persecution in their own homelands.” If Czechoslovakia was considered a safe haven by those from other countries, then surely it was safe for Karl and his family.

His mother shook her head. “Then they are naive if they think this country will protect them. I say we pack up the family and get out while we still can.”

“We are secure here in this community,” Victor insisted, “in a country that will defend itself, and defend us if necessary.”

It seemed as if the conversation would end there, but Marie perched herself on the edge of one of the settees. She glanced over at Karl and then turned to face her husband. “I have to tell you something, Victor,” she began. “I’ve been sending some of our money to a bank in Paris.”

Victor’s jaw dropped and for once he seemed at a loss for words.

“I’ve been doing it for several months now,” she continued.

“But how?” sputtered Victor.

Marie sat up straighter and thrust her chin forward defiantly. “I’ve been buying up foreign currency and transferring it to the Crédit Lyonnais.”

Victor was furious. “But Marie, this is an illegal activity!” Foreign currency exchanges were not permitted unless they were declared to the government.

“I don’t care,” replied Marie. “I’m creating a nest egg, a safety net for our family in the event that we need to get out of Czechoslovakia. And judging from recent events, this may happen sooner than you think.” She leaned forward now, pleading with her husband. “Don’t you see, Victor? We’ll have money waiting for us outside these borders.”

Karl gazed at his mother. It was so unlike her to take a stand like this against Father – to do something without his consent.

“Don’t you realize that you are putting us in grave danger?” Victor asked. By now his father’s face had turned such a deep shade of crimson that Karl feared he might pass out if further provoked.

Marie was undeterred. “I’m glad I’ve done it,” she replied. “And I plan to send some of our belongings as well – clothing and household goods. I’ll send them to Mr. Kolish, that associate of yours in Holland. He can keep some things for us in case we need them. I won’t stand back and watch this country and our lives fall apart,” she added firmly. “If no one else is going to plan for this family, then I will.”

Karl in Rakovnik with his dog. Lord.

* Now known as Žatec in the Czech Republic.

– crepes filled with jam – for dessert. Any minute now, Leila, his nanny, would knock softly at Karl’s bedroom door, telling him it was time to get up and come downstairs for breakfast. Perhaps Leila would protect him from his mother’s displeasure at discovering Lord in his bedroom. Leila Adrian had been with the family for years, and she had a soft spot for young Karl, whom she had practically raised from birth. Leila was from Sudetenland, the northern part of Czechoslovakia, a region that was home to an ethnic German population that had clashed with the Czechs over the years. But that was politics, and Leila didn’t care about that. She was ferociously loyal to this family, and her love had grown over her years of devoted service. She had never married and had no children. And while she would occasionally visit her sister in their hometown of Ústí nad Labem, the Reiser family was her true family. Karl knew Leila would try to defend him, but, more than likely, he and the dog were going to be in trouble this morning.

– crepes filled with jam – for dessert. Any minute now, Leila, his nanny, would knock softly at Karl’s bedroom door, telling him it was time to get up and come downstairs for breakfast. Perhaps Leila would protect him from his mother’s displeasure at discovering Lord in his bedroom. Leila Adrian had been with the family for years, and she had a soft spot for young Karl, whom she had practically raised from birth. Leila was from Sudetenland, the northern part of Czechoslovakia, a region that was home to an ethnic German population that had clashed with the Czechs over the years. But that was politics, and Leila didn’t care about that. She was ferociously loyal to this family, and her love had grown over her years of devoted service. She had never married and had no children. And while she would occasionally visit her sister in their hometown of Ústí nad Labem, the Reiser family was her true family. Karl knew Leila would try to defend him, but, more than likely, he and the dog were going to be in trouble this morning. the central square. Their property consisted of three buildings side by side. The first contained the grain warehouse for his father’s business, and the second housed several servants and employees. The last house on the corner was the family home. Theirs was one of several impressive buildings in this section of the city.

the central square. Their property consisted of three buildings side by side. The first contained the grain warehouse for his father’s business, and the second housed several servants and employees. The last house on the corner was the family home. Theirs was one of several impressive buildings in this section of the city. – Czech for Jew – had been painted across the brick wall of the house. The thick letters stood out on the street, emblazoned across the face of their home, their intent unmistakably menacing. Karl was not one for emotional outbursts. But this time was different. This time, he was overwhelmed with contempt for whoever had committed this crime. He stood rooted to the spot, his face flushed, his chest pounding.

– Czech for Jew – had been painted across the brick wall of the house. The thick letters stood out on the street, emblazoned across the face of their home, their intent unmistakably menacing. Karl was not one for emotional outbursts. But this time was different. This time, he was overwhelmed with contempt for whoever had committed this crime. He stood rooted to the spot, his face flushed, his chest pounding.