Language is our supreme evolutionary achievement, and this chapter is about how we can use it to sublime effect. We save our best words for our most complex thoughts, our attempts to win a sexual mate, deal with the inevitability of our own death or to persuade someone to do something they don’t want to do. It’s where language blooms in resplendent fashion. That doesn’t mean it has to be florid; it can have the simplicity of a haiku. Three hundred years ago, Alexander Pope wrote: ‘True Wit is Nature to advantage dress’d, What oft was thought but n’er so well expressed.’

A manual on how to hunt, plough, build a house, fight a war or paddle a boat can get by with pretty basic language. But courtship won’t go far if you say simply, ‘You look nice, let’s have sex.’ The same goes for death: ‘What, old dad dead?’ is a great line from The Revenger’s Tragedy, but mainly for dramatic impact. Hamlet’s ‘Oh that this too too solid flesh would melt, thaw and resolve into a dew!’ certainly has more eloquence to it. Is it better? Well, that’s very subjective, and we all have our favourites, be they poems, songs, plays, novels or the speeches of a gifted orator.

The acme of language is literature; it defines our species, gives us voice, personality and history. Quite simply, it tells our story.

Essentially, what we like as a species across all cultures and throughout our history is a good story, well told: as Joyce would have it, the right words in the right order. We return first to that village in Turkanaland in north-east Kenya we visited earlier in the book, for the Turkana can tell us something about the beginnings of storytelling.

The village is about ten miles from the Sudan border. The Toposa, mortal enemies of the Turkana, live on the other side. The Toposa are as obsessed with cattle raiding as the Turkana, and for the young men of both tribes the raids are a way of life: ritually important and essential as a means of getting cattle to pay the bride price, so they can get married. It’s also tremendously exciting. Sometimes as many as a hundred heavily armed Toposa will cross the border and launch attacks. Up until thirty years ago both Toposa and Turkana relied mainly on ancient muskets, Enfields and spears, but now Kalashnikovs have replaced them. There is not a single spear to be seen, and even young boys of fourteen have an automatic rifle slung casually over their shoulders. As the day wears on the warriors start to drink their millet beer. Drunkenness and guns are never a good combination.

Turkana warriors keeping their traditions alive

But what the alcohol does is lower the inhibitions of the young warriors, and they start to tell stories of their escapades against the Toposa. Soon a crowd gathers and, emboldened by their audience, the young men launch into a full re-enactment of their latest raid. Miming their ambush of the Toposa warriors, they tell the story of capturing a hundred head of cattle, losing a couple of their men in a firefight and then the Toposa taking back some of their cattle only to be re-ambushed. The crowd love it, as do the warriors. This act of mimesis, miming out their story – with a few embellishments – goes to the heart of storytelling. There’s also a plot, action, humour (one of the men got shot in the buttocks – very Forrest Gump) and resolution.

The story is an improvised bit of drama without any religious or moral undertones. It’s a bit like an action buddy movie – a platoon of warriors on a dangerous mission meets with adversity, overcomes it; some are wounded, but the end is a happy one because the warriors return home victorious.

The Turkana have other stories, many of them traditional myths which attempt to answer the major themes of their lives. They do have a creator figure, Akuj, and there are many stories in which he is the protagonist. Most involve rain, which is the life-or-death commodity for the Turkana. These stories, like the Judaeo-Christian Bible, try to reconcile the big issues that trouble the Turkana. In the harsh environment where they live, the Turkana believe that the unreliability of the rains which cause drought, famine and death can be alleviated by the intercession of Akuj, the bringer of rain.

Storytelling is as old as language and is rooted in our life as a social animal. It is a universal across all cultures throughout history. When the Turkana tell a story they do more than just entertain the community, they bind it together in a communal ritual. This ritual (and it’s not so different from being read a Harry Potter book, or going to the cinema to see Avatar or watching a performance of Hamlet) illustrates two of our most important traits: our ability to create imaginary worlds – fantasy – and our capacity to empathize. Empathy allows us to reach out to others and understand another’s emotions and needs whilst fantasy allows us to postulate alternatives and imagine new ways of seeing reality. Both are at the heart of good storytelling. But what could be the evolutionary advantage of being so prone to fantasy?

‘One might have expected natural selection to have weeded out any inclination to engage in imaginary worlds rather than the real one,’ says linguist Steven Pinker, but he thinks stories are in fact an important tool for learning and for developing relationships with others in one’s social group. And most scientists agree: stories have such a powerful and universal appeal that the neurological roots of both telling tales and enjoying them are probably tied to crucial parts of our social cognition. Pinker’s hypothesis is that as our ancestors evolved to live in groups, so they had to make sense of increasingly complex social relationships. Living communally requires knowing who your group members are and what they are doing and if possible what they are feeling and thinking. Storytelling is the perfect way to spread such information.

Storytelling is at the heart of the indigenous people of Australia. There were over 400 distinct Aboriginal clans when the first British settlers arrived in Australia, and each of them had their own body of stories that describe and link the eternal mythical world of what they call the ‘Dreaming’ with the everyday world of living. The stories are called ‘Songlines’.

It’s almost impossible for a non-Aborigine to understand the idea of the Dreaming which underlies the Songlines. The Dreaming is an English word that attempts to describe the entire mystical and ontological life of the Aborigines and encompasses how they are linked to the contours of the landscape in which they live. Aboriginal actor Ernie Dingo tries to explain: ‘When you talk about it, you think about it in the back of your head – “Now hang on a sec, how did that story go?” – and that moment of thought would come like a dream. So it’s going back into the past through memory, rather than in the English sense, through the history books.’

The Dreaming is an extraordinarily complex body of stories that guide the Aborigines in their quest for water, hunting, fertility. Each of the Aboriginal tribes has its own stories, and these are sung in Songlines or Dreaming Tracks, the paths created by the ancestors during the Dreaming as they criss-crossed the country. This is one from the Grampian Mountains of Victoria.

The Gariwerd Creation Story

In the time before time began Bunjil, the Great Ancestor Spirit, began to create the world around us: rivers, mountains, forest, desert. He created the animals and plants. He appointed the Bram-bram-bult brothers, the sons of Druk the frog, to finish the task of naming the animals and making the languages and laws. At the end of his time on earth Bunjil rose into the sky and became a star, where he remains.

There was a giant ferocious emu named Tchingal, who ate people. His home was in the scrub, where he was hatching a giant egg. One day, Waa the crow flew past and, feeling peckish, started to eat the egg. When Tchingal came back and saw this he was furious and chased Waa all over the place and each time he escaped Tchingal crashed into mountains creating the gaps in the rocks and the streams than run through them.

So do Aborigines sing their stories because songs tend to be more memorable?

Ernie explains, ‘It’s both a rhyme and rhythm, and the rhythm is the heartbeat. You sing this, your heartbeat can tell you how much time you’ve got to travel. So the song that you sing, if it’s a good old slow song, you know that this is a long journey, before you get to the next part of the verse. The story will stay similar to the rhythm of the walk and it tries to get your heart to pace you so that your step paces you to the next location in the song.’

Songlines explore themes of hunting and fertility and each Aborigine tribe has their own set of stories

The Songlines are a brilliant, practical way of navigating. They tell you compass points, give you landmarks (depressions in the land, for instance, are remembered in the songs as the footprints of the creator beings), and reinforce the identity of each tribe by making everyone learn by heart their collective history. They also, as any parent will know who’s tried to coax a child on a long walk, provide sufficient distraction and entertainment to make the journey more bearable.

If you like a gripping story, packed with adventure and heroic exploits, jealousy and loyalty, friendship and family, love and loss, and the yearning to find the way home, then read – no, listen to – this:

Tell me, Muse, of the man of many ways, who was driven

far journeys, after he had sacked Troy’s sacred citadel.

Many were they whose cities he saw, whose minds he learned of,

many the pains he suffered in his spirit on the wide sea,

struggling for his own life and the homecoming of his companions.

Even so, he could not save his companions, hard though

he strove to; they were destroyed by their own wild recklessness,

fools, who devoured the oxen of Helios, the Sun God,

and he took away the day of their homecoming. From some point

here, goddess, daughter of Zeus, speak and begin our story.

It’s the opening lines to the Odyssey (from a translation by Richard Lattimore), the towering epic poem of the trials and tribulations of the Greek warrior Odysseus, as he tries to sail home to Ithaca after the fall of Troy.

Homer’s Odyssey may be Western literature’s first – and some would say most influential – work but it was not a written creation. It was born out of, and shaped by, an ancient oral tradition which memorized and passed on stories, cultural values and information from generation to generation, long before we learned to write. It’s more song than words.

Except that, at some point, it was written down. We’re not sure when and we’re not sure by whom: probably some time around the late eighth century BC, by a man we call Homer, but who might have been more than one person, according to scholars. Around the same time, a few decades earlier, probably, Homer’s other masterpiece, the Illiad, was also written down, and together they form the bedrock of the Western literary tradition.

Homer’s epics are great yarns, wonderful stories and, far more, they create vivid worlds of complex human desires and contradictions, where people love and suffer, fight and die, live with dignity or dishonour, struggle against misfortune and tragedy and fate. The characters try to understand the world they live in, the physical and the unseen, against a backdrop of heroic deeds and all-too-human gods. Like all the best tales, they’re in essence stories of the human condition, and their depictions of the ancient world, their plots, styles, literary devices and imaginative sweep have soaked into our culture, language and art. Every epic journey, road movie, every tale of the returning warrior, every story of the absent father and the coming-of-age son, Dante’s Inferno, the epic poetry of Milton and Pope, the classical poets, the Romantics, James Joyce’s Ulysses – they all owe their inspiration and origin to Homer’s Odyssey.

The Greeks themselves considered the Illiad Homer’s greatest work; and it was the story of Achilles, and not the wanderings of Odysseus, which Alexander the Great took with him as bedtime reading on his campaigns. Both poems draw their inspiration and material from the Trojan War myths. You know the story: Helen seduced by Paris and whisked off to Troy, the face that launched a thousand ships, Agamemnon leading the Greeks against King Priam in the ten-year-long war, the burning towers of Ilium, Achilles dragging the body of Hector round the walls of the city, the Trojan horse and the fall of Troy. And then one of the Greek generals, Odysseus, gets lost on his way home. It’s the ancient world’s equivalent of the greatest road movie ever – except it was by boat.

It’s the Odyssey which has given us some of the greatest stories and adventures in literature, as Odysseus and his men meet one obstacle and disaster after another: navigating between the lethal whirlpool and rocks of Scylla and Charybdis; being captured by the one-eyed Cyclops Polyphemus, whom Odysseus blinds with a stake so that he and his men can escape clinging to the undersides of the Cyclops’ huge sheep.

Things are always going wrong, working against Odysseus getting safely home, either because of the gods or the stupidity of the men, or the weather. Like when Aeolus, the master of the winds, gives Odysseus a leather bag containing all the winds, except the west wind, to speed him home safely. The sailors think the bag’s got gold in it, and they wait until Odysseus is sleeping and then open it. All the winds fly out in a fury, and the resulting storm drives the ships back the way they had come – just as Ithaca had come into sight. Then there is the episode when Odysseus decides he wants to hear the irrisistible song of the Sirens, who would lure sailors to their death on the rocks. He gets his crew to plug their ears with beeswax and tie him to the mast, with strict orders not to untie him, no matter how much he begs. So there he is, writhing against the creaking mast, straining towards the singing

Homer’s Odyssey may be Western literature’s most influential work

Homer wrote epics full of vivid worlds and complex human desires

So they sang, in sweet utterance, and the heart within me desired to listen.

And so it goes on, twenty-four books and 12,000-odd lines of pacy, vivid poetry which have burrowed deep into our Western collective imagination in the same way as the Bible stories have done.

The mystery of who Homer was and the scholarly debates about the exact origins of these epic poems only add to the allure. There’s no trustworthy information about the life and identity of Homer which have come down to us. All we have is what we read that the ancient Greeks believed, people like Herodotus, who thought Homer lived about the ninth century BC, and Aristarchus of Alexandria, who offered a much earlier date – he believed Homer lived about 140 years after the Trojan War (which we date around 1200 BC). The Greeks believed Homer was blind, and some thought he came from Chios, others from Smyrna. They also assumed that he was a poet who wrote. There was disagreement about when the poems assumed their final shape, and whether different poets wrote the Illiad and the Odyssey – but everyone, all the way down to Alexander Pope in the eighteenth century, assumed that Homer was a poet who composed with the written word.

Scholarship over the next couple of centuries challenged this traditional view and located the poems in a pre-literate culture, with an oral composition and transmission span of generations, until they were finally written down, probably in the eighth century BC. Academics argued that Homer was, in fact, one of a long line of oral poets and that the style of oral compositions is very different from written ones. They analysed the texts and identified the repeated use of descriptive phrases – what we call Homeric epithets – like ‘divine Odysseus’, the ‘wine-dark sea’, ‘grey-eyed Athena’, ‘rosy-fingered Dawn’, and even whole repeated lines and standard set-pieces of description. They argued that these formed a vast repository of word-groups, a sort of poetic diction, which the oral poet would draw on. He would hear them and learn others from other poets, and during the live performance of his poem, which could go on for hours, he could use them when he improvised. He could draw on words and phrases which would fit the metre and rhyme, signpost the characters for the listeners, give shape and pace to the whole. The argument continued that this kind of poetic diction could only be the cumulative creation of many generations of oral poets over centuries, and was so complex that it couldn’t have been the work of a single poet.

No one today would claim that one man called Homer sat down and wrote the Illiad and the Odyssey at one sitting. But we can say that one man probably perfected what generations worked at, a magnificent poet who, perhaps over a lifetime, gathered the treasures and resources of an ancient traditional art, shaped and polished old stories, and created something vivid and new – these powerful dramas about the tragedy of Achilles and the desperate wanderings of Odysseus, which have stood the test of time and fired the imagination of succeeding generations. Whether this poet was called Homer or not doesn’t really matter. Because, whatever the origins and authorship of these epics, it’s their supreme storytelling verve, their poetry and the imaginative power driving them which still speaks to us.

Here’s another example, from the opening of the Illiad, in a modern, vernacular translation by the American scholar Stanley Lombardo:

Sing, Goddess, Achilles’ rage,

Black and murderous, that cost the Greeks

Incalculable pain, pitched countless souls

Of heroes into Hades’ dark,

And left their bodies to rot as feasts

For dogs and birds, as Zeus’ will was done.

It’s rousing stuff, with the immediate promise of action and terrible deeds, and that ringing phrase which instantly turns the spotlight on the brooding, proud figure at the centre of the drama – Achilles and his ‘black and murderous’ rage.

Stanley Lombardo is so passionate about the poetry and the music of the Illiad and the Odyssey that he travels around performing them to live audiences, just as the bards did millennia ago. Armed only with a drum, which he beats at strategic points in the action, he recites sections from the poems. ‘You experience the poetry of Homer in a different way,’ he says. He thinks that Homer came to this level of composition through performance.

The Illiad is full of passionate, rousing language

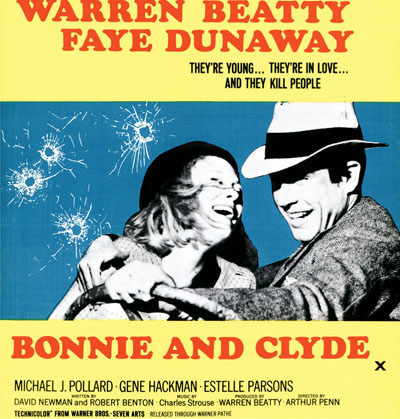

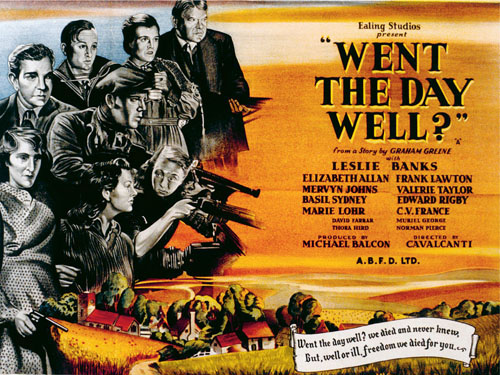

Bonnie and Clyde, a modern tragedy

The Seven Basic Plots

What makes a good story? Compulsive characters, scintillating dialogue, wonderful writing – certainly – but for most of us, the plotline is the vital ingredient in a story, the roadmap, as it were, for characters.

Most writers will tell you that there are only so many storylines to be told. Some have even tried to put a number on it. Rudyard Kipling is thought to have had a list with sixty-nine basic plots; others have argued for thirty-six, twenty and – in the case of Professor William Foster-Harris – three. He suggested happy ending, unhappy ending and the ‘literary’ plot, ‘in which the whole plot is done backwards and the story winds up in futility and unhappiness’. Ronald Tobias argues that all plots can be boiled down to two – ‘plots of the body’ and ‘plots of the mind’. Some have even managed to squeeze all the stories in the world into one plotline: exposition – rising action – climax – falling action – denouement.

The most useful list – certainly the best fun at dinner parties – is probably that of journalist Christopher Booker, who proposes that all narratives in the world are variations of a basic seven plots. Here they are, along with some story suggestions to get the conversations going:

Overcoming the Monster: the hero confronts and defeats a life-threatening monster or evil force. The hero returns home victorious. Beowulf, ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ and Dracula would fit into this category, along with all the James Bond films, High Noon, Jaws and Alien.

Rags to Riches: a commonplace character, often in wretched circumstances, achieves wealth, status, beauty, happiness. ‘Cinderella’, ‘The Ugly Duckling’, ‘Aladdin’ (and a host of other fairy tales) have common links with Jane Eyre, David Copperfield and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

The Quest: the hero sets out on a hazardous journey to reach his goal, confronting dangers and temptations along the way. The Odyssey, Pilgrim’s Progress, Don Quixote, Lord of the Rings, Raiders of the Lost Ark and Watership Down (yes, rabbits can be heroic).

Voyage and Return: the hero leaves home to explore another, often magical, world and, after a dramatic escape, returns to the familiar world. The Chronicles of Narnia, Alice in Wonderland, ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’, ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’, ‘Sleeping Beauty’, The Wizard of Oz and Gulliver’s Travels. Many of the Quest stories fit this bill as well.

Rebirth: the hero is overcome by dark forces and then redeemed, often by the power of love. ‘Snow White’, Silas Marner, It’s a Wonderful Life, A Christmas Carol, Star Wars, The Grinch.

Comedy: a chaos of misunderstanding which eventually resolves itself into a happy ending. Everything from Oscar Wilde plays and Jane Austen novels to Feydeau farces and most of Shakespeare’s comedies.

Tragedy: a flawed character spirals down into evil and inevitable death or disaster. From Macbeth and King Lear to Bonnie and Clyde and Madame Bovary.

There are other genres, of course – mystery, romance, sci-fi – but most of the stories will fit into the framework of one of these seven basic plots.

Why is it that some books have us staying up all night to finish them and others stay unread after the first few pages? What is it about one story which has us quivering for more and another which has us wriggling with boredom? The secret of what makes a good story is the Holy Grail of writers, publishers and movie and TV executives. Get it right, and you’ve got a chart-topping book or film on your hands. Get it wrong, and you’ve got a flop. Nowhere is the secret of a good story more hungrily sought than in the movie business, where hundreds of millions of pounds are made or lost at the box office.

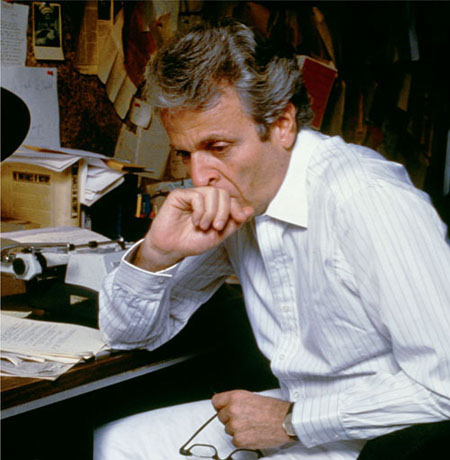

William Goldman, double Oscar-winner and considered by many to be Hollywood’s pre-eminent screenwriter, should know a thing or two about the ingredients for a good story – or perhaps not, as his most famous quote is ‘Nobody knows anything.’ Goldman described in his memoir, Adventures in the Screen Trade, how one of the highest-grossing films of all time, Raiders of the Lost Ark, was turned down by every studio in Hollywood except Paramount. And Star Wars was passed over by Universal. ‘Nobody – not now, not ever – knows the least goddamn thing about what is or isn’t going to work at the box office.’

It’s hard to believe that, after more than fifty years in the story business, Goldman doesn’t have an inkling of what works and doesn’t work. After all, he’s the screenwriter of some of the most intelligent films of the 1970s and 80s – Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Marathon Man, All the President’s Men, The Stepford Wives, The Princess Bride …

Goldman has described with real feeling the torment of writing.

‘Writing is finally about one thing: going into a room alone and doing it. Putting words on paper that have never been there in quite that way before.’ As he says, ‘The easiest thing to do on earth is not write.’ It’s reminiscent of Thomas Mann’s definition of a writer – a person for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.

So how does Goldman find inspiration for his stories? His screenplay for Marathon Man was adapted from his own novel and was made into an iconic thriller staring Dustin Hoffman and Laurence Olivier in 1976. Goldman says it was based on two ideas. The first was what would happen if someone in your family wasn’t what you thought they were. (That’s the Dustin Hoffman character, who thinks his brother is an oil man and actually he’s a spy.) As for the second idea: ‘I was walking on 47th Street in New York – the diamond district – about forty years ago, and it was a hot day, and all the people that worked in the diamond district were wearing short-sleeve shirts, and you could see all the terrible marks from the concentration camps – because they were all Jewish and they all had their tattoos – and I got the notion: what if the world’s most wanted Nazi was walking along this street?’

William Goldman at his writing desk, 1987

From these two ideas emerged a compulsive story which climaxes in a torture scene which has put a generation of filmgoers off going to the dentist. The marathon-running student, Dustin Hoffman, has his teeth drilled without anaesthetic by Laurence Olivier, the former Nazis SS dentist at Auschwitz, who repeatedly asks the clueless Hoffman, ‘Is it safe?’

Goldman may insist that a walk along New York’s 47th Street gave him the germ of his story, but the point is any one of us could have been walking along that street and noticed the tattoos. Only a very few are able to carve a story out of the scene. It’s a bit like Michelangelo contemplating his block of marble – his genius is what he takes away, revealing the statue of David inside. Goldman has a mind that makes stories.

If you read through the movie trade magazines, there’ll always be a page somewhere advertising a piece of software or a seminar or a course that claims to teach you how to write. You can actually buy an application for your computer that supposedly allows you to build a story. It’s as if you can break down a story into a knowable, quantifiable entity that can be proscribed and created according to a formula. William Goldman reckons if it were possible to pre-programme a successful story, we’d all be doing it and making a fortune. Just look at the success of the film The King’s Speech.

‘There’s no logic to it. I mean, who in the name of God thinks there’s gonna be a successful worldwide movie that wins every honour about a king who has a stammer? It’s the worst idea I ever heard but, guess what, it was a fascinating story and it works.’

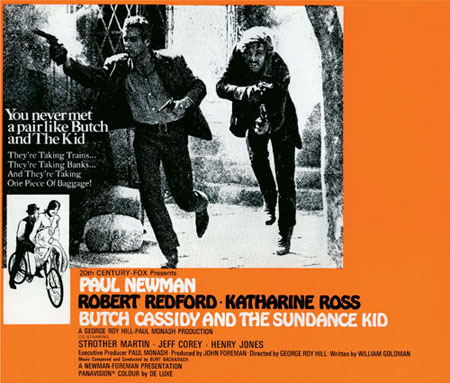

Casting is surely a vital element in the sense that it can completely alter the way you see the story. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is the most commercially successful of all the films Goldman has written screenplays for. It got him his first Oscar as well as establishing the buddy movie genre. The winning combination of actors Paul Newman and Robert Redford as the eponymous Wild West outlaws was obviously a factor, but Goldman insists that it was a piece of luck. The part of the Kid was supposed to have been played by Steve McQueen, who along with Newman was the biggest movie star in the world at the time. But they couldn’t agree on the billing – literally the size and positioning of their names – so McQueen pulled out. Jack Lemon was offered the part but declined because he didn’t like horses. Warren Beatty turned it down, as did Marlon Brando, who ‘disappeared off with the Indians’. So finally they got Robert Redford. ‘But who knows, if we’d had McQueen, if it would have been different. I don’t know, it might have been better, it might have been worse.’

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid won Goldman his first Oscar

Very little was known about the real-life characters Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and Goldman spent years researching their lives before he wrote his screenplay, in which the two men run away to Bolivia.

‘When I tried to sell the movie, a guy in a major studio said he would buy it if they didn’t go to South America. And I said, “But they went to South America.” He said, “I don’t give a shit. All I know is that John Wayne don’t run away.” And I’ll never forget that sentence, “John Wayne don’t run away.” ’

Goldman’s experience suggests that, although the basic plotlines of stories are universal, our idea of the hero has changed. There was a time when heroes were heroes and, like John Wayne, they didn’t run away. What Goldman and his generation did in the late 1960s and early 1970s was to add a new twist – that you could have a hero who is self-deprecating and flawed and not made of granite.

Goldman remembers the thrill of discovering Homer as a child, immersing himself in the tales of the siege of Troy. And then reading Cervantes as a student and flinging his book across the room in a rage when Don Quixote dies. He’s almost apologetic in his admiration of these authors.

‘I’m gonna say something stupid … they were great at story. They really had fabulous stories to tell.’

Irishman James Joyce is acknowledged as one of the great and most original voices in world literature, but to many there’s an aura of impenetrability about his work that puts them off. Stephen Fry’s Desert Island book on Radio 4 was Joyce’s novel Ulysses and he urges anybody who’s never read it – or tried to and thought that it was too difficult – ‘just to let themselves go and swim into it, because, apart from anything else, there were never more beautiful sentences in any single book’.

Ulysses chronicles the journey of the middle-aged Jewish Dubliner Leopold Bloom through the streets of Dublin on an ordinary day, 16 June 1904. To a small but passionate group of devotees, an obsession with the book manifests itself in a rare literary curiosity: Bloomsday. Bloomsday is celebrated every year on 16 June, all over the world, often recreating events from the novel. In Dublin it’s frequently experienced as a lengthy pub crawl.

David Norris, a senator in Ireland’s parliament, the Taoseaich, is a hugely enthusiastic Joycean and Bloomsday participant. He explains why 16 June was so significant to Joyce and his wife Nora.

‘I didn’t know Joyce, I didn’t know his wife Nora, but I knew all their friends very well and I remember Maria Jolas saying that in the thirties in Paris, when Bloomsday was mentioned, Nora would adopt an insouciant look and she said, “That was the day I made a man out of Jim.” ’

So why is Ulysses lauded so highly? Partly it’s the style, the content, and the language, which is a tour de force that has never been matched since, but it’s also the humanity of the characters. The genius of the book is that Joyce manages to take examples of Homer’s epic adventures of Odysseus (Ulysses in Latin) and find in a single day in Dublin a modern equivalent of the Sirens and the Circe and the Oxen of the Sun. Not only that, but each chapter that represents one of those eighteen adventures has its own colour, atmosphere, smell and linguistic style. The novel contains everything in human life, including public masturbating and use of the c-word that caused it to be banned in the UK until the 1930s. (It was published in Paris in 1922.) It also confronts issues that we now consider to be very urgent and modern, like racism.

The primary beauty of the novel is the hero, Bloom, who is warm, frail, silly and loveable, and yet he’s bullied, treated badly, whispered about behind his back. Another wonderful thing about him is that he’s so at home with the workings of his own body. The first time you meet him he’s having a crap. Joyce describes him shitting and pissing with the same casual exactitude with which he describes him thinking, and it’s all treated as part of a continuum. And the character of Bloom, this extraordinary man who we follow over the course of twenty-four hours, grows and grows in stature and warmth and dignity. He becomes a hero out of the most ordinary material imaginable.

David Norris thinks that part of the genius of the book is in its detail. Joyce didn’t just invent one day, he investigated and researched that one day in minutest detail. So on that 16 June in 1904, there was a particular horse race that was run, and there was a particular jockey and there was a particular time when the odds on the betting were such and such. And he put that in. He mapped that day completely, perfectly, and Norris believes that’s part of the obsession we have with the book to this day. Joyce renders reality with words in a way that a painter can capture the essence of something with brush strokes. Ulysses pioneered what became known as the stream-of-consciousness novel, or in Joyce’s case, the irrational hiccups of human thinking.

Norris adds: ‘Few writers have had more grace and splendour in the way they write. It is just simply beautiful.’ He tells the story of Joyce’s great friend, Frank Budgen, who met Joyce in a café in Zurich one day and found him looking rather pleased with himself.

James Joyce, one of the most original voices in world literature

‘Good day’s work, Joyce?’ said Budgen.

‘Oh yes’, said Joyce.

‘Write a chapter, couple of pages, paragraph, a sentence?’

And Joyce replied, ‘I had the words and the sentence yesterday but I got the order right today.’

As Joyce said himself in Finnegans Wake, it’s about getting ‘the rite words in the rite order’. But what’s probably surprising for those who have been put off reading Ulysses because they think it’s too difficult or obscure (which is true of his last work, Finnegans Wake) is just how much Joyce uses the rhythms and idioms of the street and pub. He had an uncanny ear for the overheard remark.

Norris laughs. ‘Every kind of Dublin saying, like “the sock whiskey” for sore legs, for instance, is in it. Joyce collected these things, and I often think that subsequent writers must have thought it terribly unfair competition, because Joyce was so terribly greedy; he left nothing behind for other people.’

He was, to be sure, a hoarder of linguistic treasure.

Davy Bryne’s pub is one of the many that grace the pages of the book. Over delicious grilled liver providing an olfactory accompaniment altogether fitting in a novel so keen to that sense, Norris reads out a passage from the opening scene where Bloom is preparing breakfast for his wife Molly.

Mr Leopold Bloom ate with relish, the inner organs of beasts and fowls. He liked thick giblet soup, nutty gizzards, a stuffed roast heart, liverslices fried with crustcrumbs, fried hencods’ roes. Most of all he liked grilled mutton kidneys which gave to his palette a fine tang of faintly scented urine.

Kidneys were in his mind as he moved about the kitchen softly, righting her breakfast things on the humpy tray. Gelid light and air were in the kitchen, but out of doors, gentle summer morning everywhere. Made him feel a bit peckish.

The lilt of David Norris’ accent adds something to the already lyrical cadence of the writing. Does this Irishness lend to the English language another quality which has helped make Hiberno-English writers so successful? He believes it’s because of their discomfort with English. Joyce says, ‘My soul frets in the shadow of your language’ (meaning the English language). Norris cites a book by Father Peter O’Leary, in which he describes hearing two children talking in the period of the famine. One child says to the other, ‘I have no language now, Sheila.’ ‘Why, what have you got?’ she asked him back, and he says, ‘I have only English.’ And English was, of course, the language of emigration, of administration, of logic and calculation and bureaucracy, whereas Irish was the language of creation, the imagination, improvisation. You find this kind of exuberance in the Irish language, and that cannot be eradicated. So it’s as if they’re speaking Irish in their mind and translating it into English; and it’s that exuberant creative side that is the classic Hiberno-English sound.

Norris adds: ‘We tend to be a bit subversive and we’re subversive in language too; and people will deliberately use a form of a word that they know is wrong, but the sound of it appeals to them a little bit more.’

Declan Kiberd and Barry McGovern are sitting in O’Neills Bar on Suffolk Street, a stone’s throw from Trinity College Dublin, where Samuel Beckett studied. Kiberd is Professor of Hiberno-English Literature at neighbouring University College, Joyce’s alma mater, and McGovern is an actor, a stalwart of the Abbey Theatre, who created a wildly successful one-man Beckett show. Over pints of Guinness – what else? – the conversation heads into the rich waters of politics and language. Kiberd is a champion of W. B. Yeats.

‘I would say the greatness of Yeats was that he took up the oral energies of the people just when the Catholic middle class were trying to transcend them and cast them to one side, and he said no, these are beautiful and they’re important. He invented really the modern idea of Irishness and Ireland, and the brilliance of Yeats is that he was both the Irish Shakespeare and its Derek Walcott all rolled into one.’

Kiberd warms to his theme that Yeats was the creator not only of some of the most memorable and patriotic poems, like ‘Easter 1916’, but also of a cycle of plays that invented Ireland in the same way that Shakespeare’s Tudor plays created the idea of England. But he was also postcolonial Ireland’s foremost critic, becoming extraordinarily sceptical of and disillusioned with the very country he’d helped to create. Kiberd is convinced that the Bardic idea is probably an essential role for any great writer: you don’t just praise the chieftain on good days but you are honest enough to speak the truth and say when things are not being done right.

‘And for me that’s the magnificence of Yeats, that he was both a tremendous Irish patriot and an absolute auto-critic.’

He believes that Ireland has represented itself through its writers. He tells the story of Oliver Gogarty, a member of the early Irish Senate, who stood up one day and said to the other Senators, ‘We wouldn’t be here today in a Senate of an independent Ireland, were it not for the poems of someone like W. B. Yeats.’ He was affirming that the word can become incarnate, can become an action.

W. B. Yeats captured the essence of Irishness

Easter 1916

I have met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

I have passed with a nod of the head

Or polite meaningless words,

Or have lingered awhile and said

Polite meaningless words,

And thought before I had done

Of a mocking tale or a gibe

To please a companion

Around the fire at the club,

Being certain that they and I

But lived where motley is worn:

All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born …

I write it out in a verse –

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

It becomes becomes clear in this Dublin pub that an unselfconscious delight in ideas and language are at the heart of good storytelling. There’s a great story Yeats picked up in Sligo about a man who went to a cottage and asked for a bed and breakfast, and they said, ‘Sure, but you have to tell us a story in return.’ And he had no story, so they kicked him out. He went to the next cottage, and they said, ‘Yes, you’re welcome, but tell us a story.’ No story, so he was booted out the door. So he went to a third house and he complained bitterly and described in detail his treatment in the other two houses. So the description of how he was treated for not having a story became the story itself, and he was taken in.

While it’s a particularly Irish story, it’s also a universal that any culture can understand and appreciate.

‘You make your destitution sumptuous, and that’s what Samuel Beckett did and why in some ways he is perhaps the central voice of this culture,’ Kiberd concludes.

‘In the last ditch,’ he concludes, quoting Becket, ‘all we can do is sing.’

In many ways it was a serendipitous time to be an Irish writer in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – comparable, perhaps, to being an English writer in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Just as Ireland created linguistic gold out of the cataclysmic changes after the Hunger, there’s something about the language in Elizabethan England that was growing and developing as the country found itself: the King James Bible, the outpouring of plays, the new words that were emerging and a new confidence and boldness in using them. And then, of course, there was Shakespeare.

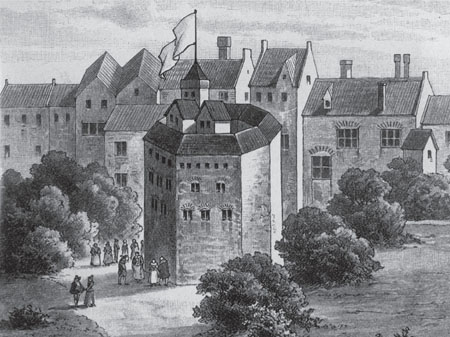

Imagine you could go back 400 years or so to wander the streets of Elizabethan London. You might pop into a tavern, hoping to bump into Shakespeare or Marlowe or Jonson or Webster, and watch as they drank and talked and scribbled, or go to the newly built Globe Theatre in Southwark on the south bank of the Thames and pay your penny to stand with the other ‘groundlings’ in the pit in front of the stage and experience for a few hours that extraordinary flowering of language and theatre that the world has never seen since. Shakespeare might be there acting in one of his own plays; and – it being 1600 – the performance on stage that night might well be his latest work, Hamlet.

There was a sort of explosion of words taking place in early modern English in the sixteenth century. What Shakespeare did was to give style and structure to the language, to mine its rich seam and to add to its vocabulary. He invented, or was the first to put in print, around 3,000 new words. You may think you don’t know any Shakespeare but of course you do. Expressions like in one fell swoop and it’s not the be all and end all; or make your hairs stand on end, cruel to be kind, method in his madness, too much of a good thing, in my heart of hearts and the long and short of it. Eaten out of house and home, love is blind, foregone conclusion – the list goes on and on, and they’re all creations of Shakespeare. Clichés today, perhaps, but genius.

Someone (Stephen Fry, as it happens) once wrote that as theatre is a rhetorical medium and film is an action medium, so the perfect film hero is Lassie. The hero doesn’t need to speak. The boy’s on the cliff edge, Lassie looks, Lassie grabs the trouser leg, pulls the boy back … you just watch the action unfold. And the perfect theatrical hero is Hamlet, because everything is expressed in language, absolutely everything. It’s rhetoric, and he does it like no one else on earth. Hamlet explores sex, life and death, hope, revenge and despair. He’s utterly contemporary.

The Globe Theatre, c.1600

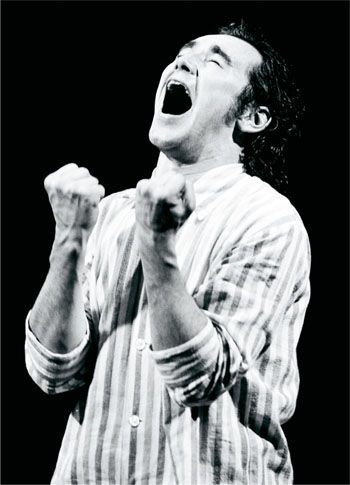

For this reason, the role of Hamlet is seen as the ultimate test for an actor, a theatrical Everest. The character is so full of complexities and the play itself is so well known that sleepless nights are spent worrying about how to bring something new to some of the most quoted lines in literature. A roll call of theatre greats have played Hamlet – John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier, Richard Burton, Peter O’Toole, Derek Jacobi, Ian McKellan. Three actors who’ve all taken the part of the Prince in the last decade talk about the role: Simon Russell Beale played the student prince at the National Theatre in 2000 to rave reviews; David Tennant, best known as BBC TV’s Dr Who, was Hamlet in a Royal Shakespeare production in 2008; and Mark Rylance has played Hamlet three times – first as a teenager, then with the RSC in 1989 and again at the Globe Theatre in 2000.

Laurence Olivier as Hamlet, 1948

‘Absolutely terrifying’ is how Simon describes performing the ‘To be, or not to be’ soliloquy for the first time on stage. ‘Apart from it being so famous, it was scary because it’s such a simple question.’ He says it took him until well through the run before he got to grips with the power of the soliloquy – its calmness and self-control.

‘I get the sense that it was a radical exploration of a single human soul in a way that hadn’t been done before.’

Stephen Fry and Simon Russell Beale in the Globe Theatre

For the Elizabethan audience, Hamlet must have seemed incredibly modern and cutting-edge. Macbeth, for instance, was set 400 years before, but Hamlet is completely different; he has a whole different set of morals and a whole new outlook on the world. The controversial American scholar Harold Bloom wrote a book called Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human in which he claimed that before Shakespeare there were no real, rounded, ambiguous, complex characters.

Some people argue the culture we live in, with the competing attractions of television and books and computer games, makes Shakespeare too boring for an awful lot of people, simply not important. Is there any argument Simon can propose that would persuade someone to feel that Shakespeare is worth trying, that he’s not an unpleasant medicine that you have to take for the good of your soul?

Simon admits first off that Shakespeare does take work – there’s no way round it. He was lucky at school because he had teachers who managed to inspire him. He admits that there are boring bits in Shakespeare – bad bits occasionally – but it’s worth the effort:‘It really does yield extraordinary riches.’

The passion which Shakespeare inspires was evident when Simon was touring with Hamlet in Eastern Europe. One day he arrived in Belgrade, where the play’s poster with his face on it had been stuck up everywhere. He went into a shoe shop, and the woman serving shouted, ‘Hamlet! Hamlet!’ when she saw him and just kept saying, ‘To be or not to be,’ over and over again. The idea of that simple little phrase being repeated everywhere they went – even in China – is rather moving.

‘Utterly terrifying, poleaxing with fear because of all the baggage that it brings with you and because of the expectation that people have.’ That’s how David Tennant remembers feeling before his opening night as Hamlet at the National Theatre in 2008. He’d wanted the part since he was an eighteen-year-old drama student and he’d seen Mark Rylance play Hamlet when the RSC came to Glasgow.

‘I saw him at that very formative age and … it sort of sang. And you suddenly realize that these plays are deeper and wider and longer and better. Utterly contemporary, which is sort of a magic trick because it remains four hundred years old, and yet it seems to keep being reborn and rediscovered.’

Accepting the role of Hamlet – ‘like keeping goal for Scotland’ – was a brave thing to do. David was at the height of his TV career playing Dr Who and was put under intense media scrutiny in the run-up to opening night. David describes the newspaper articles with critics drawing up their top ten Hamlets of all time and wondering where David would fit in the list.

‘And you think, please Lord, let me just remember the lines. And then on the first night the News 24 truck draws up outside your dressing-room window, and you think, oh so now I’m going to fail on a global scale. Terrifying but also so thrilling to have those words at your command and to have that part in your palm for even a brief time. And you think, how do I begin? And of course you just begin by not worrying about it, which sounds terribly simple and isn’t, but there’s sort of no way round it other than just going, “Well, this character happens to say these lines here and they’re the first time they’ve ever been said.” ’

David Tennant holding Yorick’s skull, donated by André Tchaikovsky

Richard Burton said it helped him to remember that there’s always someone in the audience who will never have heard a single line of Hamlet before, so this is absolutely the first time for them. For other audience members, this is not the case. One night during a performance at the Old Vic Burton heard a dull rumble coming from the stalls; it was Winston Churchill sitting in the front row, reciting the words along with him.

Another of David’s favourite scenes is Act 2, Scene 2, when Hamlet says to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, ‘I can be bounded in a nutshell and count myself the king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams’.

‘You just get the sense that he hasn’t slept for days,’ says David. ‘He wants to sleep but can’t. And if you’ve ever had those long nights of the soul … it’s just that sense which is so vivid in that speech of “all I want to do is close my eyes but I can’t because it’s terrifying when I do, because my brain is so full of demons, and I hate myself so much”.’

Shakespeare talked a lot about sleep. He probably didn’t get enough of it or maybe he simply loved to sleep. The language he used – in Julius Caesar he calls it the ‘honey-heavy dew of slumber’; in Macbeth it’s ‘sore labour’s bath … balm of hurt minds’ – isn’t that fabulous?

The most identifiably visual moment of the play is the gravediggers’ scene, when Hamlet holds up the skull of the court jester and says, ‘Alas poor Yorick, I knew him’. It’s a memento of death, just like the ‘to be’ soliloquy. ‘I think the Yorick moment is much more specific,’ says David ‘because he’s looking at the material of a human being and he’s imagining that lips hung here and he’s trying to get his head round the actuality of death.’

The skull used in David’s performance was in fact a real one, donated by a concert pianist called André Tchaikovsky, who donated his head to the RSC in his will, to be used as a Yorick.

‘The first few performances holding a real human head was terribly potent because that is exactly what it’s about – we will become inanimate matter.’

As a young boy Mark Rylance spoke too fast to be understood by anyone. He had elocution lessons to slow him down, chanting tongue twisters and reciting poems and prose out loud. Mark found that learning bits of Shakespeare by heart and speaking the lines in front of people was the first time that he was able to express a whole range of emotions and ideas. He performed his first Hamlet as a sixteen-year-old school boy, then played him again aged twenty-eight and finally at forty. He reckons that’s about 400 performances in all.

When Mark was offered the part of Hamlet at the Royal Shakespeare Company it was a huge thing for him. He told the director, Peter Gill, that he planned to go up to Stratford immediately and read the old prompt scripts of all the luminaries who’d played the part, ‘like it was some big oak tree and I hoped I might add a little twig to the tree by being aware of all the choices they’d made’. Peter Gill told him not to be a fool – they’re all dead and gone or at least not playing the part any more. ‘ “It’s you who are alive now. Make sure it’s not set in outer space, but apart from that it’s you.” I said, “Yeah, but David Warner, he has such a …” “He was only wonderful because he was of his time,” said Gill, “and you’re of our time.” And that comment comes right down to the last ten seconds before you’re about to enter to say “To be, or not to be”.’

Just like Richard Burton, Mark had encounters with members of the audience who knew the play a bit too well. He had to be careful not to make his dramatic pauses too long. ‘In Pittsburgh there was a little old lady sitting next to her husband, and I came out right next to her in my pyjamas, all tearful and crying, and I said, “To be, or not to be”. And then I thought for a moment. And she turns to her husband and says, “That is the question”. And everybody heard it and laughed a bit. But I was able to say, “That is the question!” ’

Those sort of close-hand experiences with the audience stood Mark in good stead when he was appointed the first artistic director of the newly recreated Globe Theatre in 1995. He developed strong ideas about the relationship between actors and the audience, so that by the end of his ten years there he says he thought of the audience as more like fellow players. They were bringing the most important energy of the whole evening, a desire to hear a play. Mark likens it to a moment when he was playing Hamlet and delivering the line ‘Sit still, my soul: foul deeds will rise, though all the earth o’erwhelm them, to men’s eyes’.

Mark Rylance as Hamlet

‘I remember performing the play out at Broadmoor special hospital and turning to a man and I wasn’t aware whether he was a nurse or a patient but I could see his imagination was completely with me. And in that moment between us I felt: who’s to say you’re the audience and I’m the actor? We’re in this together.’

Hamlet’s soliloquy

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die, to sleep,

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache, and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to: ’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep;

To sleep, perchance to dream – ay, there’s the rub:

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause – there’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovered country from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pitch and moment,

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.

Sir Christopher Ricks is one of the greatest literary critics of our day. He’s written seminal works on Milton, Keats, Tennyson, Beckett, T. S. Eliot, edited the Oxford Book of Verse, has been Warren Professor at Boston University since 1986 and until 2009 was Professor of Poetry at Oxford University. He’s been described as holding all of English poetry in his head. He was also my very exacting professor at Bristol in the 1970s.

Photos of Ricks’ academic subjects adorn the walls of his elegantly spacious office at Boston’s Editorial Institute, which he now runs – the haggard, intense face of Samuel Beckett, T. S. Eliot besuited and respectable, and Bob Dylan, whom he has favoured with a compelling 500-page critical work entitled Dylan’s Visions of Sin. Sir Christopher is the critics’ critic. Scholarly, yes, with an extraordinary forensic ability for close textual analysis down to the use of the comma or apostrophe, but also very funny and in his seventy-seventh year as bright and acute as ever in not letting any lazy thinking get in the way of good criticism.

Stephen Fry almost had Ricks as his supervisor when they were both at Cambridge University in the 1980s. Now, thirty years later, he finally gets the chance of a one-to-one tutorial with the Professor. The ostensible subject is Beckett and Dylan and why poetry matters, but in typical Ricksian fashion they end up dancing all over the place. Here’s a flavour of the Ricks Masterclass, kicking off with the difference between poetry and prose.

Bob Dylan, a poet songwriter

CR: I think poetry is to be distinguished always from prose. They have different systems of punctuation.

SF: That’s a really good point because it’s a game people play to try and devise the best, most compact, most necessary and sufficient definition of poetry as opposed to prose. And you said different punctuation which sounds trivial but it strikes at the heart of it in a way, doesn’t it?

CR: Well, I think that it does. The line endings are significant in poetry or verse. They carry significance.

SF: So it’s the shape on the page. T.S. Eliot said that poetry is not about expressing emotion or personality, it’s almost the opposite. And people might say, but surely poetry is the excess, the demonstration of personality and emotion?

CR: You’re right, especially in a world in which too much is being made of the idea that poetry is self-expression. Though Eliot is always resourceful enough to know that you need a multiplicity of ways of talking about things. That is, a poem is in some ways like a person. In another way it’s like a plant. In another way it’s like a beautiful building. We need all these figures of speech. The key term from him, I think, is when talking about intelligence either in criticism or in poetry – he thinks of it as judging. It’s the discernment of exactly what and how much you feel in any given situation. So it doesn’t make poetry or literature the realm of feeling as against prose as the realm of fact or proof or argumentation. I think it’s a very, very beautiful formula in what it does with both thinking and feeling.

SF: And it requires a huge amount of honesty. Direct confrontation.

CR: Great honesty, including doubts about the rhetoric of honesty. So as one says, ‘I’ll be completely honest with you,’ as though in the ordinary way I was doing no such thing.

SF: Yes quite. We’ve started with Eliot, which is for some people the start of modernism and the time when a lot of the public turned off poetry. But while we’re on the subject of him there’s a precision, an almost miraculous ability to create lines which stick in the head like music. Anybody who’s read Eliot will probably say he’s one of the easiest poets to memorize a phrase from. And I wonder where that comes from. Why, for example, ‘the young man carbuncular’ and not ‘the carbuncular young man’ in a modern poem?

CR: Well it would partly be that – the striking turn of phrase, and that is indeed a turn, isn’t it? What it’s doing is imitating languages, ancient or modern, in which an adjective comes after a noun. The human form divine becomes the young man carbuncular and so on. So there’s something about moving. You’ve got to allow a shape to it. So I think he’s always interested in resisting either the tyranny of the eye or the tyranny of the ear. Each is inclined to take over. The eye will say every time you use the word ‘image’ it’s clear that imagination is seeing things. But every time you turn to a figure of speech that comes from hearing, you seem to be deaf to this.

SF: That’s a very good example of the close attention to language that people might find astonishing in your work. You go almost to the molecular and atomic level of a sentence and into the syllables and the actual structure of words and you find in them an energy and they are often the thing that causes the whole work to show itself.

And I suppose as much as anything, the problem that poets have to confront is that they’re making their art out of something that is common to all humanity. Unlike a painter who can go to a shop and get turpentine and acrylics and canvas and brushes or a musician who has a special language of augmented sevenths and special machines made of brass and wood. There’s another Eliot phrase – ‘to purify the dialect of the tribe’. So a poet has to take the same thing I use when I order a pizza over the phone and turn that into art. And does that mean poetry has two choices? One is to embrace the everyday and the other to try and get rid of it and to find a noble and elevated language.CR: I think it’s always having to do both. I think poetry is very like ordinary life. It’s continually wanting some arrangement of things that are new and surprising to it. It’s continually interested in the fulfilment of expectations and in the arrival of surprise.

SF: Yes. You want to be surprised but you also want the comfort of reassurance that you know them.

CR: The poet Donald Davy talks about how the words of a poem should succeed one another like the events of a well-told story. They should be at once surprising and just. That is, it’s easy to be surprised if you don’t care whether the effect is a just one. It’s easy to be just if you don’t care whether it’s surprising. Bob Dylan loves rhyming ‘new’ and ‘true’ because every artist is in the business of finding something new to say that is also true. It’s easy to find something new to say. It’s easy to find something true to say but these people come up with very extraordinary things that are at once new and true.

SF: Again it suggests the Eliot line in the ‘Four Quartets’ about arriving at a place and seeing it for the first time. There is this sense in poetry and even in just great writing of being in a familiar place and being assured by the authority of a writer that you trust them and yet also being surprised by them because they make you look with new eyes and things. And is that something that you think is innate in that there is a certain class of person who can do this and they do it with words when someone else might do it with music?

CR: Dr Johnson believed that there were talents and you employed them in any way that struck you. It’s as if you were at the North Pole and you could walk south in many different directions. But what you do is essentially exactly the same, you walk south. On the other hand some people are amazingly numerate. They can look at a spreadsheet and see that the figures have been rigged and fixed. They can see that the books are being cooked. I could look at equations and symbols and numbers for ever and be blank. What about you?

SF: I’m exactly the same. I don’t understand. And as you say some people are like a spider on the web – every twitch of the filament means something to them. And they can chase it down. So yes there is the gift of language.

CR: Well, I think poets are really intelligent, and resourceful poets are much less vulnerable than you might think because their self criticism is alive to what might be the criticism of others. Pretty well all great writing has a warning about over-valuing writing in it. At some point or other Shakespeare will tell you not that plays or dramatic representations tell no truths but that you must remember they also tell lies. And so words half reveal and half conceal the truth within. And every great writer has intimated some such things at some point.

SF: I think that’s absolutely right. Language is a bit like a dress. A dress can reveal the form, can flatter the form, can exaggerate the form, can give a real sense of the beauty and elegance of a particular form but it also hides deformities. It also masks and covers nudity; covers the passionate side of us, our fleshly side. And words are constantly doing that.

There’s also this idea that there’s great literature: Leavis and his great tradition and Harold Bloom and his sense of the canon of writers, but can they include in that twentieth- and twenty-first-century figures from what is often called popular culture – like Bob Dylan who you’ve written about?CR: I think Dylan uses words with extraordinary effect. The effect is related to a different system of punctuation – the speed and pace at which it goes is determined by him, his music and his voice. He changes those and the beautiful thing he says about the songs is, my songs lead their own lives, and it’s lives in the plural not because each song has a life but because each song has lots of lives. I think again and again Dylan is very good when you can imagine an unimaginative creative writing school telling him he’d got it wrong. I think that he’s simply astonishingly imaginative with words.

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.

Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead

Scribbling on the sky the message He is Dead.

Put crepe bows round the white necks of the public doves,

Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves.

He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest,

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song;

I thought that love would last forever: I was wrong.

The stars are not wanted now; put out every one,

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun,

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood;

For nothing now can ever come to any good.

That poem was written by W. H. Auden, but you may well know it better from the film Four Weddings and a Funeral, where it was recited during the funeral of the title. It’s extraordinary how something can have such impact, be so succinct and have such emotional truth behind it.

For anyone who’s had to organize a funeral, the choice of words is one of the most difficult things to get right. In the past, the traditional funeral passages from the King James Bible had little competition. But in our more secular times many prefer not to invoke religion at all. So what do we do when we want to express the grief and love and sadness of the loss of someone? Music is integral, and, if it’s right, the emotional heft will inevitably lead to tears.

So what led Four Weddings scriptwriter Richard Curtis to choose the Auden poem for the funeral scene, a choice which catapulted sales of Auden’s poetry beyond anything he’d enjoyed while still alive?

Richard explains with his unfailing modesty that he didn’t feel up to the job.

‘Tragically in my life, in every film I’ve ever done, the single best moment in the film has nothing to do with me at all. I was writing a moving funeral scene so I thought I’d better leave it to a better man. I’d always been told I should study Auden and I didn’t understand most of his poems. And I remember being very thrilled when I came across that one. And I think it’s no coincidence that it’s in fact called ‘Funeral Blues’ and it’s a lyric; it was meant to be sung. And that is symptomatic of the fact that I’m passionate about lyrics in a way more than poems.’

It’s become the thing to choose songs rather hymns or prayers at funerals. ‘I Did It My Way’, ‘Je Ne Regrette Rien’ or ‘Angels’ may be a bit clichéd, but people clearly feel their lyrics do the job better than a poem or a reading. They can express a communal emotion that everybody can share.

Richard has a theory that we don’t have access to poems now in the way we once did. The Romantic poets were celebrities in their day. People were outraged by the work of Byron because they knew about him, he was famous. Nowadays it’s hard for a poem to break through into the popular culture, so what happened with Four Weddings was a rare example of a poem being heard by enough people to get a passionate reaction.

Poems are often perfect word for word, pop lyrics less so, although, as Richard is keen to point out, there are some wonderful wordsmiths in the world of pop lyrics. He cites Paul Simon as one lyricist who has written some extraordinary, powerful songs.

‘Every day I think of that line from “The Boxer”: “A man hears what he wants to hear and disregards the rest.” And it lodges in your head, and as you go through life you realize people are only hearing a bit of what you say because it’s the bit that suits them. Rufus Wainwright’s song “Dinner At Eight” is about him and his father, and there is no finer expression of the argument between a son and a father who abandoned him. And there are the huge, big popular ones that everybody knows. They become the fabric of your life, and those lyrics are carried around with you and reflect your moods and feelings.’

Richard is in full flow now. ‘If you pick up a poem for the first time you have to piece it together. It’s much harder. Whereas a song by Coldplay like “Fix You” has the lyrics “I will try to fix you.” It’s very direct, and the fact that the lyrics may not be as well crafted is compensated by the beauty of the tune, and is enough to turn it into something deeper. And on top of that you have the feeling that your whole generation heard that song together, so it has a binding effect. If you stood in a stadium with 45,000 other people who know those words, it’s the Nuremberg Rally of pop.’

He’s right, of course. Pop songs are a brilliant way of people sharing a culture. But, despite his love of popular lyrics, does Richard still read poetry? He had to read lots of it at Oxford. He laughs.

‘I think there was a six-month period in which I understood it. I tried to read something by Yeats the other day which I know used to be my favourite poem. It’s gone completely. It’s as if I’ve forgotten the language.’

Paul Simon, right, with Art Garfunkel

Music

If you’ve ever wondered why you sing in the bath (if you don’t, ignore this bit); or why you spent all those hours and hours as a teenager, shutting out the annoying world of parents and other people, glued to Radio 1 and the charts; or why the hairs on your neck prickle and your heart beats faster whenever Wagner’s music fills the air – well, if you’ve ever wondered, sorry, but nobody really knows. To be precise, scientists can’t agree on what it is about music and singing that touches us so profoundly, and whether it’s something to do with our evolution. Are we hard-wired to be musical?

Music is universal. It’s found in all cultures across the ages, and archaeologists have unearthed musical instruments dating from as far back as 34,000 BC. The mystery is why humans have been singing and making music virtually since prehistoric times. What purpose does it serve?

Evolutionary psychologists have a few theories. Some think that music originated as a way for males to impress and attract females, rather like brightly coloured birds competing with each other to produce the most elaborate and complex songs. In other words, it’s a tool of evolution and natural selection: the male with the biggest lungs and catchiest song gets the girl. Another idea is that women were the original music-makers, and it goes all the way back to the universal instinct of the mother crooning and singing to her child. Experiments show that mothers automatically make their speech more musical when they talk to their babies, more lilting and melodic, and the theory is that music perhaps evolved as a sort of prehistoric baby-pacifying tool. Human babies can’t just cling on to their mothers’ bodies the way other primates do, so perhaps the singing was a way of the mother keeping contact with her children when she had to put them down to work.

And then there’s a third theory that identifies music as a sort of social glue, a way of bonding early human communities, much in the same way that football supporters or people in church or families round the piano singing together enhances a sense of tribal identity. The evolutionary psychologists trace this back to the necessity for early tribes to work together for survival: communal singing demands coordination, bringing many voices together, and the theory goes that this is a way of practising for the kind of teamwork crucial in hunting or fighting for survival.

Interestingly, researchers at the Montreal Neurological Institute discovered, when they scanned musicians’ brains, that listening to music stimulated exactly the same part of the brain which food and sex affect. In other words, music lit up the basic, instinctual, pleasure centres of the brain.

However, others dismiss these ideas. The Harvard linguist Steven Pinker caused an uproar when he addressed a conference of cognitive psychologists in 1997 and told them that their field of music perception was, basically, a waste of time because music is just an evolutionary accident, a redundant by-product of language: ‘Music is auditory cheesecake,’ he said, ‘an exquisite confection crafted to tickle the sensitive spots of several of our mental faculties.’

For many people – whatever the neurological and evolutionary theories – music is another form of language. A way of communicating without words.

Music is universal and serves as a social glue

Much research has been done on the use of music therapy with people suffering from dementia. They find verbal communication very difficult because the disease causes aphasia and amnesia. If you can’t find the words, if you can’t remember who you are, how do you express yourself and connect yourself to the people and the frightening world around you? Music therapists use singing and music in place of words. Singing a song with someone with Alzheimer’s doesn’t put demands on them; it doesn’t require the answer to a question; it doesn’t make the world even more confusing than it is. Singing is a way of being together, of inviting the person to take part, of somehow bypassing the damaged part of the brain that can no longer form the words. It releases tension and calms anxiety because it opens a door to expression when all the other doors are barred and shut tight. Music is part of who we are. It travels further, down and down into that part of ourselves which is older, deeper, mysterious.

Auditory cheesecake indeed.

If you were to chant ‘Helps you work, rest and play’, the chances are most people will respond with ‘A Mars a day’. Or if you sing, ‘Now hands that do dishes …’, a surprising number of you will feel the urge to sing ‘with mild green Fairy Liquid’. Someone younger will have the same automatic response to ‘Just do it’, immediately associating it with Nike. For just as succinct language can have a powerful effect on us through poetry and song, so the perfectly turned phrase can enter our subconscious, influencing our actions and decision-making. Nowhere is the use of the clever slogan seen more explicitly than in the language of advertising.

From an ancient Egyptian town crier hired to shout out news of the arrival of a goods ship to a computer pop-up ad offering the secrets to a flat belly, we have always found ways of attracting the public’s attention to a product or business. Advertising may have become much more sophisticated, but wherever communities and commerce exist, so too does the advert in some shape or another.

We’re been shouting our wares and promoting our products for thousands of years. Historians reckon that outdoor shop signs were civilization’s first adverts. Five thousand years ago the Babylonians hung the symbols of their trades over their shop doors, a practice still used today in areas of poor literacy or in some of the traditional shops like barbers – the red-and-white pole – or the three golden balls of the pawnbroker. A poster found in Thebes from 1000 BC offers a gold coin for the capture of a runaway slave. The Romans advertised the latest gladiator fight on papyrus posters and seem to have introduced the world’s first billboards with their practice of whitewashing walls and painting announcements on them.

The advent of printing and spread of literacy meant advertising could expand into handbills and newspapers. A newspaper ad for toothpaste appeared in the London Gazette in 1660: ‘Most excellent and proved Dentifrice to scour and cleanse the Teeth, making them white as ivory.’

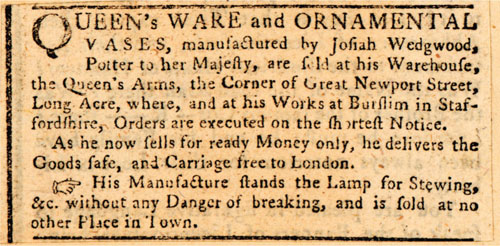

An early example of a Wedgwood ad in a newspaper, c.1769

The Industrial Revolution and the greater availability of factory-produced consumer goods brought a growing awareness amongst manufacturers that they could create a need for a product amongst the middle and lower classes able to afford luxury items. Our friend Dr Samuel Johnson wrote one of the first articles on advertising in a 1759 edition of his magazine The Idler: ‘Promise, large Promise, is the soul of an Advertisement … The trade of advertising is now so near to perfection, that it is not easy to propose any improvement.’ He wasn’t very prescient, for at that very moment one Joshua Wedgwood was founding his pottery workshop and he had very big ambitions about improving advertising technique. Wedgwood was one of the first industrialists to recognize the importance of creating a market through advertising and used newspapers ads, posters, publicity stunts, give-away promotions and money-back guarantees to persuade people of the need for a must-have Wedgwood vase or a twenty-piece dinner service.

Increased competition amongst manufacturers and a growing public sophistication opened the way for agencies in the late nineteenth century who promised to create and run advertising campaigns for the client. Advertising had become a profession. The advent of radio and television extended the mass reach of advertising, revolutionizing its persuasive potential. This is the world of advertising we’re all familiar with – the TV commercials and product placements in films and internet pop-ups.

On the reception desk of the west London ad agency Leo Burnett is a large bowl of green apples, a reminder of the humble beginnings of the founder, Mr Burnett, who established his agency in Chicago in 1935 with just one account, a staff of eight and a bowl of apples on the front desk. Legend goes that, when word got around Depression-hit Chicago that Leo Burnett was giving apples to visitors, a newspaper columnist wrote, ‘It won’t be long till Leo Burnett is selling apples on the street corner instead of giving them away.’ Leo was a wizard with visual imagery and created the iconic brands for the Jolly Green Giant canned peas and corn, Kellogg’s Tony the Tiger – ‘They’re GR-R-R-E-A-T’ – and most famously the Marlboro Man for Philip Morris, who were persuaded to repackage their woman’s cigarette as a rugged man’s smoke. Today, Leo Burnett is one of the world’s leading advertising organizations.

Don Bowen is a creative director at the agency’s London office and currently in charge of the Kellogg’s and Daz accounts. He began in the business thirty years ago as a copywriter and manages to turn on its head the adage of a picture being worth a thousand words.

‘Words are tremendously important in advertising because there have been hardly any ads where there have been only images that can make a lot of sense. The Economist has done this, once or twice, but most of the time most ads have words in them, and very often the words can be worth a thousand pictures.’