Natalie Witzmann and Christoph Dörrenbächer

Introduction

Mergers and acquisitions (M&As) are today’s main vehicle for corporate growth. This is the case even though 66–75 per cent of M&As fail to create any shareholder value (McKinsey, 2010: 1). Some studies even stress that 40 per cent of M&As among large firms end in what is called a ‘total failure’, in which the acquiring companies are far from recovering their capital investments (Carleton and Lineberry, 2004: 9). The high failure rate and the immense costs related to the failure of M&As are growing concerns not only for shareholders but also for stakeholders, such as employees, suppliers and community residents. Hence, there is rising interest in finding the reasons for the numerous failures. While traditional research has attempted to explain M&A success and failure by focusing on strategic and financial factors, a growing number of studies focus on cultural aspects. Here, the research suggests that corporate and national cultures of the involved firms should be adequately identified during due diligence and integrated in the post-M&A phase (Stahl, Chua and Pablo, 2012). However, in reality, cultural fit between the acquiring and the target firm seems to be one of the most neglected areas of analysis prior to closing a deal (Chakravorty, 2012). In 2007, Robert Carleton, CEO of Vector Group, stated that ‘Cultural Due Diligence will rarely be a critical factor in whether to “do the deal” or not, but rather a significant factor in making the deal work’ (cited in Garbade, 2009: 14). Likewise, many researchers argue that the right post-merger integration (PMI) management is the decisive factor in M&A success (e.g. Pablo, 1994; Birkinshaw et al., 2000).

This all leads to the questions of when and by what means cultural issues should be addressed in the M&A process – a complex procedure that encompasses pre-deal planning, deal completion as well as post-deal integration and the creation of value (KPMG, 2002). As indicated above, there is abundant literature on successful post-M&A integration (PMI) management, basically arguing that culture should be integrated carefully. Much less research has been done on cultural due diligence (CDD), with research on the interrelation between CDD and PMI management in its infancy. To address this gap, this chapter will look at the entire process of cultural integration, from pre-deal planning to post-deal implementation, placing particular emphasis on the interrelationship between CDD and PMI. Thereby, we aim to clarify the extent to which CDD is a prerequisite for a successful PMI process. This aim fits neatly into a gap in the M&A literature that has been described succinctly in the following extract from a recent overview article:

The existing body of knowledge [on M&A] is characterized by several independent streams of management research that have studied discrete variables in either the preacquisition or postacquisition stage. From the review of the literature in this article, it can be concluded that despite the considerable amount of research carried out into M&A over the past half century, there is limited and compartmentalized understanding of the complex acquisition process, since the various streams of research on acquisition activity are only marginally informed by one another.

(Gomes et al., 2013: 30; emphasis added)

The chapter starts with a short review of the literature on CDD and PMI. Then a conceptual model on the interrelation between CDD and PMI is developed and applied to a single-case: the Hewlett-Packard–Compaq merger. Following an analysis and discussion section, the chapter closes with some recommendations for further research.

Literature review

There is a far-reaching consensus in the literature that bringing together two different organisational cultures in a merger or acquisition is a great challenge. Following Schein (2003), incompatible cultures in M&As do not pose any less risk of failure than incompatibilities of the firms’ finances, products or markets. In line with that, Cartwright and Cooper (1993) identify cultural incompatibility as one of the primary reasons for the immense failure rate of M&As. Cultural incompatibility typically unfolds in the sociocultural integration process, ‘an interactive and gradual process in which individuals from two organizations learn to work together and cooperate in the transfer of strategic capabilities’ (Haspeslagh and Jemison, 1991: 106). Within this process different levels of acculturation can be achieved: assimilation, integration, deculturation and separation (Nahavandi and Malekzadeh, 1988). Another well- known taxonomy by Haspeslagh and Jemison (1991: 138–154) differentiates between absorption (acquired firm adjusts itself to acquirer’s culture), preservation (acquired organisation retains its cultural autonomy), symbiosis (best practices of both firms are combined, leading to cultural integration) and holding (firm does not seek any integration or value creation). Despite different levels of integration and acculturation that can be followed by firms involved in M&A, culture clash continues to be stated as the main reason for the failure of many M&As: ‘culture is more often a source of conflict than of synergy. Cultural differences are a nuisance at best and often a disaster’ (Hofstede quoted in The Economist, 2008).

What puzzles, however, given this and similar accounts (e.g. Carleton and Lineberry, 2004), is the fact that there has been little research into culture in the pre-merger phase – that is, the due diligence process. This is even more striking as a more forceful recognition of cultural aspects in the pre-deal phase is considered a prerequisite for a successful post-merger integration phase: ‘A culture audit of a potential or recently acquired organization is a valuable source of information, with implications not only for partner selection but also for long-term management’ (Cartwright and Cooper, 1993: 68).

Cultural due diligence

CDD aims to investigate the culture of the other party in an M&A in order ‘to gather information that will assist in decision making and risk analysis’ (Carleton and Lineberry, 2004: 51). Table 11.1 provides a few definitions from the literature.

Three basic insights emanate from these definitions: First, CDD is more than just a simple culture analysis but rather an instrument for a thorough examination and evaluation of the corporate cultures of partners engaged in a merger or an acquisition. Second, CDD serves as an early identification of potential cultural risks (Blöcher, 2004), which should decisively influence the PMI strategy (Carleton and Lineberry, 2004) or foreclose the deal in case of irreconcilable cultural differences and barriers (Schneck, 2007). Third, for these reasons, CDD should by no means play a subordinate role in comparison to the traditional due diligence areas (Schneck, 2007).

Table 11.1 Definition of the term ‘cultural due diligence’

| Author |

Definition |

|

| Marks (1999: 14) |

‘Culture due diligence helps buyers spot likely people problems at a target and determine whether potential clashes might sink the deal.’ |

| Galpin and Herndon (2007: 47) |

‘The primary value of cultural due diligence is that is raises sensitivity to and awareness of issues that should be proactively managed during integration.’ |

| Carleton and Lineberry (2004: 54) |

‘Cultural Due Diligence is a systemic and research-based methodology for significantly increasing the odds of success of mergers, acquisitions, and alliances.’ |

Carleton and Lineberry (2004: 69) emphasise that, as with ‘any sound organisational research, a CDD process [should] employ both qualitative and quantitative data collection’. They distinguish between ‘off-the-shelf’ and ‘customised’ CDD processes. ‘Off-the-shelf’ assessment models are generally based on quantitative data only. They do not differentiate between value-based and non-value-based differences, lack attention to detail and hence assume a ‘one size fits all’ (Carleton and Lineberry, 2004: 56). ‘Customised’ CDD processes, on the other hand, are seen to combine a qualitative research design, including interviews, focus groups and workplace observations, with a customised quantitative survey (Carleton and Lineberry, 2004).

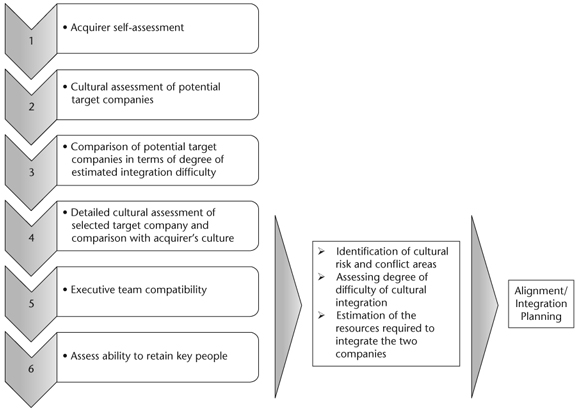

Even though the design of a CDD is, as Blöcher (2004) maintains, little standardised (but determined by the specific needs of the involved companies), Carleton and Lineberry (2004) and Schneck (2007) provide a reasonably simplified CDD process model that draws on both qualitative and quantitative data (see Figure 11.1).

The first step in a CDD process is an acquirer self-assessment (1). This is to detect prevailing problems within the acquiring firm and to provide a solid basis for a comparison with the cultures of potential target firms (2–3). If a potential target is selected, a high-level CDD assessment of the target firm is undertaken (4). Given the access problems in the pre-deal phase, a high-level CDD assessment remains more of an estimate rather than the scientific mapping of the target culture. What follows is an assessment of the executive team’s compatibility (5) and of the ability to retain key people (6). In the ‘post-letter of intent/acceptance’ phase, steps 3–6 are typically repeated in order to prepare a detailed cultural profile of the target organisation and to identify potential cultural risks and conflict areas (Zimmer, 2001). Risks and conflict areas, in turn, indicate the cultural difficulties the sociocultural PMI process is expecting.

Sociocultural post-merger integration management

A large number of theoretical and empirical studies stress the importance an effective sociocultural PMI has for the success of M&As (Cartwright and Cooper, 1993; Pablo, 1994; Quah and Young, 2005). Building on the distinction between task and human integration, Birkinshaw et al. (2000) argue that the higher the level of human integration in the early stages of the PMI, the easier and more effective the integration of tasks later. Homing in on this finding, Stahl and Voigt (2008) argue that the impact cultural differences have on the integration process, especially on human integration, should be thoroughly analysed and used in order to realise M&A synergies successfully. Despite some slight differences in definitions, these authors all agree that the lower the level of cultural integration, the higher the likelihood of post-M&A problems due to an insufficient or slow-paced task integration.

The difficulty of integrating different corporate cultures after deal is often attributed to a strong resistance to change that organisations face in general and in particular after M&As. Kotter and Schlesinger (2008) identify four common reasons for resistance to change based on their analysis of numerous successful and unsuccessful organisational changes. Parochial self-interest relates to people’s fear that the change will cause them to lose something of value. Another extremely important reason for resistance to change is misunderstanding and lack of trust. In this case,

employees do not comprehend the impact of the change and think that it might cost them more than they will benefit from it. People might also resist change when they assess the situation differently from their supervisors and perceive the costs involved as higher than the benefits, not only for themselves but for the entire organisation. The fourth reason – low tolerance for change – emerges when people fear they will fail to meet new expectations in terms of skills and behaviour initiated by the change.

Given the overarching importance of overcoming such resistance to change, the last three decades have seen a growing body of research on key success factors that positively influence post-merger human integration. The majority of authors argue that the following interdependent factors require particular attention.

Speed of integration

The optimal speed of PMI has been well debated in the literature. Some researchers argue that firms should take time in fully implementing the changes and gradually prepare the employees for the change, while other authors suggest that people are open for change right after the M&A announcement. There is often talk of the ‘first 100 days’ as a critical timeframe for post-deal success (Angwin, 2004). Feldmann and Spratt (1999: 2) argue that ‘if your transition is not progressing along a hundred-day critical path, you are behind the power curve’. Relating this statement to a human integration perspective, faster integration takes advantage of the employees’ initial enthusiasm and reduces the timeframe for employees to experience uncertainty feelings that mostly result from rumours going around the firm, which in turn exponentially increase with time if not actively addressed (Angwin, 2004). Vester (2002) points out the significance of speed during the post-merger integration process, particularly for M&As of technology firms, leading to the assumption that the business environment in which the merging organisations operate may determine the adequate speed of the integration process.

Trust

As Kotter and Schlesinger (2008) pointed out, one source of resistance to change is a lack of trust between the acquiring firm and the employees, as the latter do not understand the consequences of the change and might perceive it as harmful for themselves. The term ‘trust’ is defined as ‘a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behaviour of another’ (Rousseau et al., 1998: 395). Since the situation following the merger or acquisition announcement is highly unpredictable, especially for employees, people feel vulnerable and therefore initially tend to distrust the new organisational form (Stahl et al., 2012). The dynamic nature of trust, however, allows the acquirer to further target employees’ trust proactively through communicating shared norms, knowledge and goals among all employees (Bijlsma-Frankema, 2001).

Communication

According to Kotter and Schlesinger (2008), one of best ways to deal with resistance to change is ‘education and communication’, meaning that the people affected by the change should be educated about it beforehand, and the impacts of the change should be clearly communicated. Also, Haspeslagh and Jemison (1991: 180) advocate alleviating ‘concerns by carefully communicating and confirming what will not change to the managers and employees of the acquired firm’ before combining the two firms. Bastien’s (1987) study of behaviour and communication during M&As found that extensive formal and informal communication was crucial in order to reduce employees’ uncertainty feelings, which involve sudden switches from very positive to very negative future scenarios. In periods in which no or poor efforts for communication where made, uncertainty feelings among employees grew immediately, productivity decreased and employee turnover increased. Bastien (1987) concludes that the acquiring firm needs to understand its own and the target firm’s corporate cultures so that differing norms and practices do not evolve as sources of conflict and rejection. As Hubbard and Purcell (2001) posit, adequate expectations levels are set through effective acquirer communication, resulting in decreased uncertainty and less loss of confidence among key stakeholders.

Retaining key people

During a merger or acquisition the internal and external environments of the involved firms inevitably become unstable and precarious, making key performers either lose their commitment to the firm or even switch to competitors. For headhunters and competitors, M&As are among the best opportunities to recruit top performers (Galpin and Herndon, 2007). Galpin and Herndon (2007: 127) put it in a nutshell: ‘Your best players will find a new team first.’ It does not seem surprising, then, that a study measuring top management turnover rates in M&As found that for at least a decade following the acquisition, target firms lose 21 per cent of their executives each year – more than double the turnover rate of non-merged firms (Krug and Shill, 2008: 17). Therefore, ‘organisations should give the retention and “rerecruitment” of top performers one of the highest priorities during a merger or acquisition’ (Galpin and Herndon, 2007: 128). The term ‘rerecruitment’ implies not only that key people should be given incentives for staying in the firm but also that actions should be taken to keep these key people motivated (Galpin and Herndon, 2007). A more recent study by Ahammad et al. (2012) identified post-acquisition autonomy granted to the acquired company as well as the acquiring firm’s engagement to the acquired firm as critical success factors in retaining key executives.

The link between cultural due diligence and sociocultural post-merger integration management

While a few studies focus on pre-deal CDD (Blöcher, 2004; Zimmer, 2001; Schneck, 2007), most studies that show an interest in cultural integration issues exclusively look at PMI management (Pablo, 1994; Stahl and Voigt, 2008; Quah and Young, 2005; Birkinshaw et al., 2000), essentially following Haspeslagh and Jemison’s (1991: 132) assertion that ‘all value creation takes place after the acquisition’. Thereby, these latter studies more or less all neglect to mention that value creation might start long before the merger or acquisition contract is signed. There are a few exceptions, such as Kotter and Schlesinger’s (2008) proposition that communication should start prior to the deal in order to prepare the people for the change. However, even these studies ignore the fact that this requires a solid understanding of the prevailing corporate cultures at both the target and the acquirer firms, which can be attained only through an in-depth cultural analysis before any attempt is made to combine the two organisations. Although still widely neglected in practice as well as in theory, recent findings indicate that attentively connecting pre- and post-merger phases may improve M&A performance in general (Weber et al., 2011). Gomes et al. (2013) see the source of the overall negligence of a holistic process approach (e.g. Jemison and Sitkin, 1986; Haspeslagh and Jemison, 1991) in the fact that advocates of this process approach have tended to focus on either one of the stages, rather than connecting the critical success factors of the pre- and post-merger stages.

Summing up, it turns out that the link between pre-deal CDD and PMI management has been largely ignored by researchers. Hence, it is the aim of this chapter to fill this gap by examining the value a CDD entails for sociocultural PMI management in depth.

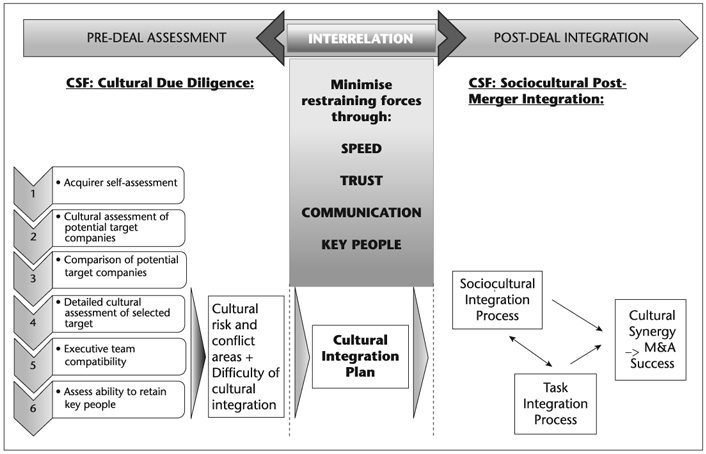

Concept and methodology

The conceptual model on which this chapter draws is shown in Figure 11.2. It posits that there is a strong interrelation between CDD and PMI and from that a significant value creation for M&As. As Lewin’s force-field theory (1963) points out, there are ‘driving’ and ‘restraining’ forces in every change process. Change, however, occurs only if the restraining forces are minimised while the driving forces are enhanced. This leads to the assumption that CDD is an indispensable step in identifying restraining forces so as to formulate a strategy of how to minimise them and as such ease the change process. Facilitators for the minimisation of the restraining forces that have been identified previously are communication, trust, speed and the retention of key people, all of which are key success factors for the PMI phase.

Hence, there are two basic propositions of the model. First, pre-deal CDD is able to identify restraining forces that potentially burden the sociocultural PMI integration process. Second, these insights allow for an enhanced fulfilment of key success factors in the sociocultural PMI process.

Given the rather piecemeal research on the subject and the need for basic theory building, this chapter follows an explorative approach that aims to elucidate and understand the interrelation between CDD and PMI by studying one case in depth – the Hewlett-Packard–Compaq merger of 2002 (Dyer and Wilkins, 1991). Following Yin (2009), single case studies hold great potential for the critical testing of a well-formulated theory proposition. A single case study then enables the researcher to determine whether the proposed theory or hypothesis can be confirmed or extended, or in contrast entirely disproved. Hence, the single case study can provide a considerable contribution to knowledge and new theory construction.

To this end, in the following sections we examine the different CDD activities of the case merger in the pre-deal phase and anaylse their value for the post-merger phase. The merger of Hewlett-Packard (HP) and Compaq (CPQ) was chosen since HP revealed detailed information about its CDD activities in this merger, which is rare. Moreover, even today it remains one of the biggest mergers in the computer industry, which led to considerable public attention, allowing use to build this study on secondary sources from business journals, academic books and newspaper articles. In addition, relevant material from the home pages of HP and Compaq was studied.

Since there is no direct knowledge on what impact HP’s CDD activities had on the rather successful sociocultural PMI, the remainder of the chapter is dedicated to study the integration management processes throughout the pre- and post-deal phases and to examine their interrelation in view of the conceptual model. In other words, we will study whether the CDD facilitated an enhanced fulfilment of key success factors of the PMI, such as speed, trust, communication and the retention of key people.

The case study: cultural integration at the HP–Compaq merger

The HP–Compaq deal is known as the biggest IT merger in history (Smith, 2002), involving 150,000 people in 160 countries (Business Week, 2001). The two companies were not in favourable market positions and there was no way for them to compete with major rivals, such as IBM and Dell, aside from this merger (Beer, 2002). Despite some strong opposition from one major shareholder (the son of HP’s co-founder, Walter Hewlett), the merger was agreed in March 2002. The new HPQ (HP–Compaq) reached a combined revenue of $87 billion based on the numbers of the last four quarters at that time, putting it neck and neck with IBM for the title of largest technology company in the world (Business Week, 2001). HP and Compaq further expected to reach cost synergies of about $2.5 billion by 2004 through the merger (Lohr and Gaither, 2001), which would be achieved through the laying off of 15,000 employees (Kinsman, 2002), among other things.

Looking back at the HP–Compaq merger ten years later, Carly Fiorina, former CEO of HPQ, regards it as definitely successful. In an interview on Bloomberg TV in 2011, she said:

If you look at the numbers there is no question [that this merger was the right move]. We went from a lagging PC business to the leader in the world in terms of revenue, market share and profitability … And we improved the growth rate and the profitability of our already-leading printing business. So, yes, it was a huge success.

This assessment still holds true today. Even though the company has experienced some trouble in recent years, it is still number two (behind Apple) in the highly competitive computer hardware business (Bloomberg Business Week, 2014). Referring back to McKinsey’s estimate that 66–75 per cent of M&As fail to achieve the anticipated synergies (McKinsey, 2010: 1), it seems that HP and Compaq have done a good job in merging and integrating two large technology companies with strongly established and quite different cultures.

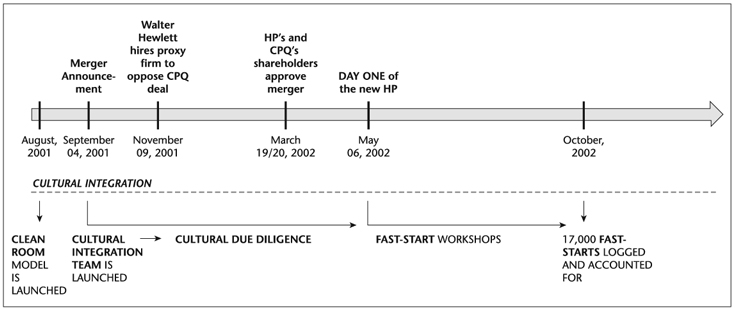

Figure 11.3 provides a timeline of the merger and the main cultural integration activities that took place first in what has been labelled the ‘Clean Room’, then in the cultural integration team and finally in the so-called fast-start programme.

The Clean Room

In August 2001, one month before the merger was announced, the companies’ CEOs Carly Fiorina (HP) and Michael Capellas (Compaq) decided each selected a senior executive from their respective companies to be in charge of the integration effort (Burgelman and Meza, 2004). Fiorina chose executive vice-president Webb McKinney, while Capellas appointed Jeff Clarke, Compaq’s chief financial officer (Burgelman and McKinney, 2006). Together, McKinney and Clarke headed the ‘Clean Room’, in which a Clean Team was able to concentrate exclusively on the merger integration, away from the day-to-day distractions of the still operating – and competing – companies (Burgelman and Meza, 2004). The term ‘Clean Room’ originated in the health and computer chip industry, where work is done in separate, spotlessly clean environments in order to avoid contamination. In the M&A context, ‘contamination’ means the flow of confidential information merging companies are not allowed to exchange due to competition rules (Koob, 2006). Hence Clean Room members were permitted to ask their non-Clean Room colleagues for information, but they were forbidden to discuss any integration matters with them (Allen, 2012).

The Clean Room model enabled the merging companies to work on integration plans even though the deal still lay ahead (Koob, 2006). With an initially small, dedicated thirty-person team of project managers, OD experts, consultants and analysts (Burgelman and Meza, 2004), Clarke and McKinney began the integration work (Allen, 2012). During the following six months, the Clean Team ultimately grew to about 2,500 people (Allen, 2012), who all ceased working on daily business operations and instead focused exclusively on the immense integration workload (Burgelman and Meza, 2004). The key objective of the Clean Team’s work was to enable the merged company to ‘open its doors and hit the ground running on day

one’ (Allen, 2012: 51). By March 2002, the Clean Team had already worked an estimated 1.3 million hours on creating a road map for how to mesh the two long-term competitors into a single firm (Lohr, 2002).

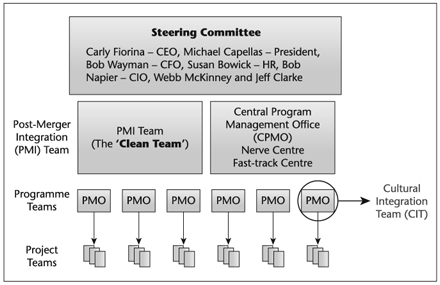

Within the Clean Room environment, small, discrete post-merger integration teams were formed according to a ‘Noah’s Ark’ model – a buddy system that was designed to avoid a potential us-versus-them mentality (Burgelman and Meza, 2004). The underlying idea was to match each HP manager with a Compaq counterpart, with these pairs working under the central Post-Merger Integration Office (Central Programme Management Office; CPMO), as illustrated in Figure 11.4 (Allen, 2012). In order to discuss and review their integration plans and proceedings, the Clean Teams met every week in person. Within the Clean Room, an ‘adopt-and-go’ approach was applied. This essentially meant identifying and selecting the best practices among both firms throughout the merged company (Tam, 2002). This encompassed business models, processes, products, as well as cultural cornerstones, such as corporate values and objectives. Anything that was not identified as best practice was to be eliminated (Harvey, 2002; Allen, 2012; Burgelman and Meza, 2004). Technically, the adopt-and-go approach operated a traffic light system for the 10,000-plus adopt-and-go decisions that had to be made: completed or ahead-of-schedule projects were marked green; projects that were on track were yellow; and those that were behind schedule were red. This approach allowed the combined firms to move fast once the merger received clearance (Allen, 2012). Clarke argued that the adopt-and-go strategy later prevented ‘politicking’ among employees, as they were aware that the Clean Room decisions were not up for discussion, only for execution (Burgelman and McKinney, 2006: 24). In order to supplement the adopt-and-go approach, Susan D. Bowick, HP’s executive vice-president of human resources and workforce development, introduced the ‘launch-and-learn’ approach, which legitimised fast decision-making to achieve good – but not necessarily perfect – decisions (Burgelman and McKinney, 2006: 25). Finally, this fast decision-making was supported by the principle of ‘getting the dead moose on the table’, which entailed frank discussions among the teams in order to solve emerging conflicts before the integration of the merging firms took place (Burgelman and Meza, 2004; Burgelman and McKinney, 2006; Allen, 2012).

The Clean Team was closely linked to the Steering Committee, which consisted of a small group of high-ranking senior executives (as illustrated in Figure 11.4) who made quick decisions and had the authority to insist on their execution (without running into lengthy discussions).

Cultural integration team

Within the Clean Team and as a sub-PMI team, the Cultural Integration Team (CIT; see Figure 11.4) was established to ensure an effective and fast cultural integration of the two companies (Burgelman and Meza, 2004; Allen, 2012). The CIT, consisting of HP and Compaq employees as well as some external consultants from Mercer Delta, was introduced immediately after the merger announcement (Tam, 2002). While the Clean Room itself was developing a new corporate culture through jointly planning the ‘new HP way’, the CIT was launched solely to examine the cultural differences between the two firms. It did this by conducting an extensive CDD throughout both companies (Allen, 2012). The CDD consisted of 127 individual executive interviews and 138 focus groups that in turn assembled 1,500 managers and individual contributors in 22 countries (Stachowicz-Stanusch, 2009). A large-scale survey was rejected after due consideration as this might have confused employees and could have created uncertainty feelings among the personnel (Allen, 2012). In line with that, Elise Walton, then senior partner at Mercer Delta and a CIT consultant, explained that ‘qualitative data was much more valuable [as] we were able to do a content analysis of all comments and the output was immediately useful’ (quoted in Allen, 2012: 52).

The CDD assessment revealed many differences between the two strongly established corporate cultures. The major cultural differences are summarised in Table 11.2.

The CDD data was then included in Clean Room decisions, especially concerning human resources, organisational design and structure, staffing of key positions, reward and compensation plans, as well as executive selection (Allen, 2012). Hence, by April 2002, HP announced the names of 150 senior managers who would be in charge of key positions in the new HP’s four business lines and international corporate functions. In order to ensure a strong integration effort, pre-merger HP and Compaq both offered retention bonuses to about 8,200 key people, of which only 10 per cent were in executive positions (Burgelman and Meza, 2004). These retention bonuses amounted to 50 per cent of the recipients’ salaries plus ‘target bonuses’ and were paid in two rates, one upon deal closure and the second after the first year (Fried, 2002).

Table 11.2 Differences in HP’s and Compaq’s corporate cultures

| Hewlett-Packard’s corporate culture |

Compaq’s corporate culture |

|

| • Culture of consideration, thoughtfulness, and planning |

• Culture of ready, shoot and aim |

| • More careful culture |

• Quicker to act due to fewer discussions |

| • Voicemail culture |

• Email culture |

| • Impulsive managers |

• Bureaucratic managers |

| • More internally focused |

• More externally focused |

| • Rather systematic |

• Rather spontaneous |

| • Relies on organisation’s rich history as a source of knowledge |

• Focuses on future possibilities and learn as they go |

| • Review of events so as to find best practices |

• Trial and error; forges ahead without looking back |

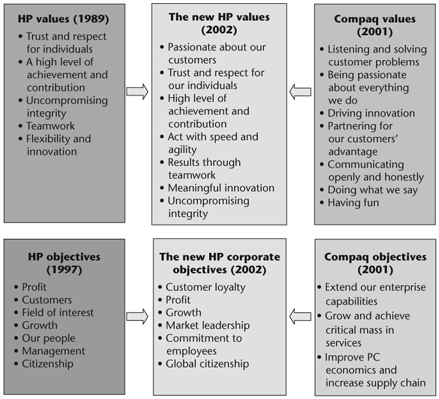

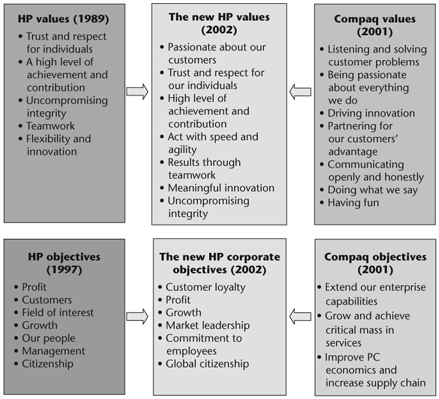

For the design and launch of the new HPQ culture, the CIT implemented a so-called ‘living systems’ approach that preferred a communicative and participative form over a top-down method of change (Maturana and Varela, 1980). In line with that, questions such as ‘Which values and objectives of the two companies should be preserved?’ and ‘What should be created?’ were asked in order to generate an evolutionary set of cultural cornerstones (Allen, 2012). Then the adopt-and-go approach was applied to pick the best of what existed between the two corporate cultures (see Figure 11.5). Paul Brandling, a long-standing HPQ employee, noted that the underlying bedrock values were teamwork, trust and respect, speed and agility. He further argued that, given that the two corporate cultures would accept those, ‘they will start to shape attitudes and behaviours which eventually flesh out into culture’ (quoted in Boyd, 2002: 2).

Once the new cultural cornerstones were agreed, the CIT started to share them in interactive sessions with the various Clean Teams (marketing, HR, etc.) (Allen, 2012). These sessions included a ‘mirror exchange’ exercise in which HP and former Compaq employees had to describe one another, for instance through the use of sports analogies (Tam, 2002). Along with this exercise, the CIT created an employee website that featured a monthly ‘culture-in-action’ story, illustrating the pre-merger cultures while at the same time highlighting the preserved cultural values. These activities were designed to foster employee engagement and create a mutual cultural awareness and understanding among the two workforces (Allen, 2012).

The Fast-Start programme

The CIT also introduced a ‘Fast-Start’ programme, an integration workshop programme that aimed to accelerate the work of the newly integrated teams. In April 2002, before the Fast-Start programme was initiated and before merger day one, HP held a two-day ‘Leadership Readiness Summit’ with 300 Compaq and HP leaders to launch the new approach (Tam, 2002). The leaders were supplied with all of the necessary material and knowledge to share within their respective offices (Allen, 2012). Fast-Start consisted of ten modules that newly assigned managers had to walk through in their teams’ kick-off meetings, which were attended by HP and former Compaq employees (Stachowicz-Stanusch, 2009). These modules could be completed either in two consecutive full days or split into two-hour sessions over one or two weeks (Allen, 2012), but they had to be completed within the teams’ first thirty days (Stachowicz-Stanusch, 2009). The completion of the Fast-Start programme was mandatory for all levels of the firm and its results were tied to the new HPQ balanced scorecard and manager compensation (Tam, 2002). The major objectives of these Fast-Start sessions were to accelerate HPQ’s cultural integration and to establish the team cohesion that would drive execution and bring forth the newly combined corporate culture (Stachowicz-Stanusch, 2009). By October 2002, more than 17,000 Fast-Start sessions had taken place (Allen, 2012).

Figure 11.5 The values and objectives of the new HP – integrating the best of both cultures

Analysis and discussion

HPs cultural integration strategy

According to Nahavandi and Malekzadeh’s (1988) acculturation model, HP’s and Compaq’s acculturation mode could be identified as ‘integration’. This implies that HP as well as Compaq cherished and wished to preserve their own cultures while at the same time perceiving the other firm’s corporate culture as very attractive. In the HPQ merger this degree of congruence regarding acculturation preferences led to low acculturative stress and hence to a higher likelihood of achieving cultural synergy. The acculturation congruence in the HPQ merger was a given as both companies were willing to adopt some cultural values and objectives from the other firm while also giving up some of their own, as required by the adopt-and-go approach. Further, HP’s extensive efforts concerning its CDD activities and the associated integration mode were in line with Blöcher’s (2004) empirical study, which revealed that a CDD is typically applied by acquirers who strive for a high degree of integration.

Likewise, the type of cultural integration strategy adopted by HP and Compaq strongly matches Haspeslagh’s and Jemison’s (1991) cultural integration model. More specifically, the integration strategy can be identified as a ‘symbiosis merger’ in which the best practices of both firms are combined, leading to cultural integration. According to Haspeslagh and Jemison (1991), a truly symbiotic merger can be achieved only when both organisations adopt the original characteristics of the partner firm. The intention to achieve symbiosis is recognisable, for instance, in HP’s adopt-and-go approach and in the Noah’s Ark model. The intention was to retain an optimal interaction between the merging organisations through an evolutionary change process. The key here is that the change process was evolutionary rather than revolutionary. Following O’Toole (cited in Carleton and Lineberry, 2004: 19), ‘anthropology indicates that culture changes in one of two basic ways, revolution and evolution, and attempts at revolutionary culture change always fail; it is the shared experience and common history of a group over time that changes the culture’. In line with this, HP’s new cultural cornerstones were designed according to an evolutionary set of cultural values and objectives, also influenced by its adopt-and-go approach.

As already indicated, the remarkable effort HP put into its CDD procedure shows a high desire for cultural integration. The various CDD activities within the Clean Room laid the perfect foundation to ensure timely cultural integration, while the Clean Teams developed a new culture, particularly the CIT, which focused exclusively on examining the various cultural factors and helped to create the necessary cultural awareness and understanding between the two corporate cultures.

The link between CDD and PMI

In order to examine the actual value of the CDD for the PMI in the HP–Compaq case, we will now analyse the extent to which the CDD facilitated an enhanced fulfilment of the PMI key success factors: communication, trust, speed and retention of key people.

Communication

Following Kotter and Schlesinger (2008), communication is one of the best ways to deal with resistance to change. HP’s early integration efforts and the Clean Room itself were indicators for a timely communication between the merging companies. The launch of the Clean Room and its Clean Teams, consisting of both Compaq and HP employees, allowed the firms to communicate ten months before the deal was finalised. This resolved the many feelings of uncertainty among the two workforces, which were due to the merger’s public discussion following a fierce proxy battle launched by a major shareholder (the son of HP’s co-founder, Walter Hewlett). In particular, the Clean Room’s dialogic approach largely averted dangerous communication holes in that situation, which can instantly lead to increased uncertainty, employee turnover and lower productivity (Bastien, 1987). Remaining uncertainty was tamed by introducing the principle of ‘getting the dead moose on the table’. This principle turned implicit communication into a transparent, two-way communication that engendered trust and mutual understanding among the employees. The same effect was provoked by the CIT’s ‘mirror exchange’ exercise. Through an informal and reflective communication exercise, crucial insights for the operations of the new HPQ teams in the post-merger phase could be gained. Finally, the Fast-Start programme clearly communicated the new cultural model that resulted from the Clean Room’s work to all levels of the newly combined workforce.

Trust

Another key success factor in the PMI that potentially reduces employees’ resistance to change is trust (Stahl et al., 2012). As just discussed, HP’s integration efforts displayed a high degree of communication that fought initial distrust resulting from the public debate about the merger. Moreover, the Noah’s Ark model contributed to the creation of trust between members of the integration teams within the Clean Room. Also, decisions taken by the Clean Teams were trusted in the two organisations as they were co-decided by colleagues. Finally, the launch-and-learn approach created trust in that it foresaw that decisions that turn out to have too many negative effects might be changed as part of the learning process (Kotter and Schlesinger, 2008). Overall, trust among the partners was generated in the pre-deal phase with considerable positive effects for an accelerated integration process in the PMI phase.

Speed

For the HP–Compaq merger, which occurred within the extremely fast-moving high-technology industry, the speed of integration was even more important than usual (Burgelman and Meza, 2004). The adopt-and-go approach substantially accelerated the decision-making process among the various integration teams. This strategy stopped politicking and contentious debate and as such facilitated high execution speed. Especially, the traffic light system simplified the 10,000-plus adopt-and-go decisions and was a critical success factor for achieving high integration speed. Similarly, the launch-and-learn approach encouraged the Clean Teams to make decisions that were ‘fast and good enough’ (Burgelman and McKinney, 2006: 25). Hence, employees did not waste time trying to achieve perfect solutions. Moreover, the Clean Room’s operating principle of ‘getting the dead moose on the table’ reduced conflict and the time needed to resolve such conflicts. Taken together, all of these pre-deal integration activities contributed to ‘the fact that the new HP was ready to operate as one from the first day the merger took effect’ (Burgelman and Meza, 2004: 20). Given HP’s extensive pre-deal integration efforts and the Fast-Start programme, HP was able to take full advantage of the famous first hundred days and initial employee enthusiasm.

Retention of key people

Although HP was initially able to retain key people through bonuses and financial rewards, about two years after the merger many key executives who were involved in the integration work had resigned or retired. Just six months after the merger, Michael Capellas, former CEO of Compaq and HPQ’s COO, left the newly merged company; he was not replaced by another president (DiCarlo, 2002). Soon afterwards, in November 2003, Jeff Clarke, one of the leaders of the Clean Room and former CFO of Compaq, unexpectedly resigned from HPQ. Susan Bowick, executive vice-president of HR, resigned at around the same time, and Webb McKinney also announced his early retirement (Lohr, 2003b). In 2005, following some harsh criticism, HP’s CEO Carly Fiorina was forced out by the company’s board of directors (La Monica, 2005). The reasons for these and other key resignations were manifold. Some executives apparently lost interest once most of the work was accomplished (Allen, 2012). Others seized opportunities to accept more attractive job offers at other companies (Lohr, 2003a). Unsurprisingly, the departures of key people who had steered the integration work led to a fading of the integration effort. Nevertheless, the cultural integration that had been achieved by that time was already rather high.

Summing up, even though the final key success factor (the retention of key people) was not enhanced through CDD, it can still be concluded that the CDD created substantial value for the PMI. During the CDD, restraining forces to the PMI could be identified and the enhanced attainment of key success factors such as communication, speed and trust significantly promoted the subsequent integration activities. As a result, the CDD can be seen as a prerequisite for a successful PMI leading to cultural synergy and in turn increasing the potential success of the merger.

Conclusion

Given the large number of M&As and their persistently high failure rate (McKinsey, 2010), researchers and M&A experts have devoted considerable effort to trying explain the recurring failures. Most of these studies, however, have neglected the fact that value creation in M&As is a dynamic process ranging from extensive pre-merger planning to a well-organised post-merger implementation of the cultural integration plan. To fill that gap, this chapter has examined the interrelationship of the pre-deal CDD and the sociocultural PMI through an in-depth literature review and a case study. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to address this relationship. It therefore fills an important gap in the body of research on cultural aspects of mergers and acquisitions. At the same time it proposes a variable to be tested in research on cultural aspects of post-merger integration problems (Weber et al., 2009, 2011). In addition, this chapter adds to the more general literature on the link between pre-acquisition and post-acquisition stages in M&As, a field of research that is still in its infancy (Gomes et al., 2013). Here, our proposition that the CDD is a prerequisite for the sociocultural PMI and hence for the successful creation of cultural synergy can be confirmed, in that the case study showed that the attainment of almost all key success factors was enhanced through a pre-deal CDD.

The first limitation of our study relates to the well-known problem of statistical generalisation of single case studies. Second, our findings are limited because we draw on secondary data. Even though the size and the overall importance of the merger in the industry provided a solid amount of authentic, reliable and representative textual data that allowed for a triangulation of content, original data might have provided further interesting explanations on issues that have been barely or not at all reported. Given these limitations, further research should build on this chapter and seek to confirm the positive relationship between cultural CDD and a successful PMI that we found for a larger number of cases, applying either a case comparison or a survey approach. This would also facilitate examination of the research question with a broader set of data sources, including primary sources gained through participant observation or interviews.

Finally, in addition to some general recommendations that have been mentioned by other studies (e.g. on maintaining leadership attention on cultural matters throughout the whole process), two important practical lessons can be learned from our case study. First, managers concerned with integration processes should be aware that cultural integration facilitates and accelerates the operational integration. Therefore, especially if the business environment is a fast-changing one, integration speed is essential and cultural integration should by no means play a subordinate role. Second, managers should ensure a timely cultural integration through a ‘clean room’ environment, foster employee engagement throughout the integration work and invest in a thorough CDD to reveal critical cultural gaps that may lead to conflict.

References

Ahammad, F. M., Glaister K. W., Weber, Y. and Tarba, S. Y. (2012) ‘Top management retention on cross-border acquisitions: The roles of financial incentives, acquirer’s commitment and autonomy’, European Journal of International Management, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 458–480.

Allen, A. M. (2012) ‘Culture Integration in a “clean room”: Reflections about the HP–Compaq merger 10 years later’, OD Practitioner, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 50–54.

Angwin, D. (2004) ‘Speed in M&Amp;A integration: The first 100 days’, European Management Journal, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 418–430.

Bastien, D. T. (1987) ‘Common patterns of behavior and communication in corporate mergers and acquisitions’, Human Resource Management, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 17–33.

Beer, M. (2002) ‘HP readies layoffs during Compaq merger’, Agence France Press, 8 May.

Bijlsma-Frankema, K. (2001) ‘On managing cultural integration and cultural change processes in mergers and acquisitions’, Journal of European Industrial Training, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 192–207.

Birkinshaw, J., Bresman, H. and Håkanson, L. (2000) ‘Managing the post-acquisition integration process: How the human integration and task integration processes interact to foster value creation’, Journal of Management Studies, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 395–425.

Blöcher, A. (2004) Cultural Due Diligence: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Erfassung und Bewertung von Unternehmenskulturen bei Unternehmenszusammenschlüssen, Aachen: Shaker Verlag.

Bloomberg Business Week (2014) ‘Computer hardware industry leaders’, March 2014. Available at: http://investing.businessweek.com/research/stocks/financials/ratios.asp?ticker=HPQ (accessed 6 March 2014).

Bloomberg TV (2011) ‘Carly Fiorina, former chairman and CEO, Hewlett-Packard’, 22 August.

Boyd, T. (2002) ‘HP contemplates cultural divide’, Australian Financial Review, 11 May.

Burgelman, R. A. and McKinney, W. (2006) ‘Managing the strategic dynamics of acquisition integration: Lessons from HP and Compaq’, California Management Review, vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 6–27.

Burgelman, R. A. and Meza, P. (2004) ‘HP and Compaq combined: In search of scale and scope’, Stanford Graduate School of Business, 15 July.

Business Week (2001) ‘The key players in the HP–Compaq merger’, 24 December.

Carleton, J. R. and Lineberry, C. S. (2004) Achieving Post-Merger Success: A Stakeholder’s Guide to Cultural Due Diligence, Assessment, and Integration, San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Cartwright, S. and Cooper, C. L. (1993) ‘The role of culture compatibility in successful organisational marriage’, Academy of Management Executive, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 57–70.

Chakravorty, J. N. (2012) ‘Why do mergers and acquisitions quite often fail?’, Advances in Management, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 21–28.

DePamphilis, D. M. (2010) Mergers, Acquisitions, and Other Restructuring Activities: An Integrated Approach to Process, Tools, Cases, and Solutions, 5th edition, London: Elsevier.

DiCarlo, L. (2002) ‘Michael Capellas’s Next Move’, Forbes, 11 November.

Dyer, W. G. and Wilkins, A. L. (1991) ‘Better stories, not better constructs, to generate better theory: A rejoinder to Eisenhardt’, Academy of Management Review, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 613–619.

Economist, The (2008) ‘Guru Geert Hofstede’, 28 November. Available at: www.economist.com/node/12669307 (accessed 26 August 2016).

Feldmann, M. L. and Spratt, M. F. (1999) A Summary of Five Frogs on a Log: A CEO’s Field Guide to Accelerating the Transition in Mergers, Acquisitions, and Gut-Wrenching Change, New York: HarperCollins

Fried, I. (2002) ‘Global 2000: HP deal: Some get layoffs, others bonuses’, CNET News, 14 January.

Galpin, T. J. and Herndon, M. (2007) The Complete Guide to Mergers and Acquisitions: Process Tools to Support M&Amp;A Integration at Every Level, 2nd edition, San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Garbade, M. J. (2009) International Mergers & Acquisitions, Cooperations and Networks in the E-Business Industry, München: GRIN Verlag.

Gomes, E., Angwin, D., Weber, Y. and Tarba, S. Y. (2013) ‘Critical success factors through the mergers and acquisitions process: Revealing pre- and post-M&Amp;A connections for improved performance’, Thunderbird International Business Review, Vol. 55, pp. 13–36.

Harvey, F. (2002) ‘No culture clash seen for HP: “Adapt and go” system’, National Post (Canada), 28 May.

Haspeslagh, P. C. and Jemison, D. B. (1991) Managing Acquisition: Creating Value through Company Renewal, New York: The Free Press.

Hubbard, N. and Purcell, L. (2001) ‘Managing employee expectations during acquisitions’, Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 11, pp. 17–33.

Jemison, D. and Sitkin, S. B. (1986) ‘Corporate acquisitions: A process perspective’, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 11, pp. 145–163.

Kinsman, M. (2002) ‘Merger imperils “HP Way” ’, Copley News Service, 8 April.

Koob, J. (2006) ‘Clean teams: The fast track to M&Amp;A integration and value’, Marsh & McLennan Companies. Available at: www.mmc.com/views/viewpoint/Koob2006.php (accessed 27 December 2012).

Kotter, J. P. and Schlesinger, L. A. (2008) ‘Choosing strategies for change’, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 86, Nos. 7/8, pp. 130–139.

KPMG (2002) ‘Unlocking shareholder value: The keys to success’, Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions and Alliances. Available at: www.imaa-institute.org/docs/M&Amp;Amp;a/kpmg_01_Unlocking%20Shareholder%20Value%20-%20The%20Keys%20to%20Success.pdf (accessed 27 August 2012).

Krug, J. A. and Shill, W. (2008) ‘The big exit: Executive churn in the wake of M&Amp;As’, Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 29. No. 4, pp. 15–21.

La Monica, P. R. (2005) ‘Fiorina out, HP stock soars’, CNN Money, 10 February.

Lewin, K. (1963) Feldtheorie in den Sozialwissenschaften, Wabern-Bern: Verlag Hans Huber Bern.

Lohr, S. (2002) ‘Assembling a big merger: Hewlett’s Man For the Details’, New York Times, 25 March.

Lohr, S. (2003a) ‘Force in Hewlett–Compaq merger resigns’, New York Times, 26 November.

Lohr, S. (2003b) ‘Key executive in HP– Compaq deal resigns’, International Herald Tribune, 26 November.

Lohr, S. and Gaither, C. (2001) ‘A family struggle, a company’s fate’, New York Times, 2 December.

Marks, M. L. (1999) ‘Adding cultural fit to your diligence checklist’, Mergers & Acquisitions: The Dealermaker’s Journal, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 14–20.

Maturana, H. R. and Varela, F. J. (1980) Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living, Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

McKinsey (2010) ‘A new generation of M&Amp;A: A McKinsey perspective on the opportunities and challenges’. Available at: http://bit.ly/VP7bXF (accessed 16 September 2012).

Nahavandi, A. and Malekzadeh, A. R. (1988) ‘Acculturation in mergers and acquisitions’, Academy of Management Review, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 79–90.

Pablo, A. L. (1994) ‘Determinants of acquisition integration level: A decision-making perspective’, Academy of Management Journal, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 803–836.

Quah, P. and Young, S. (2005) ‘Post-acquisition management: A phases approach for cross-border M&Amp;As’, European Management Journal, Vol. 23. No. 1, pp. 65–75.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S. and Camerer, C. (1998) ‘Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust’, Academy of Management Review, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 393–404.

Schein, E. H. (2003) Organisationskultur: The Ed Schein Corporate Culture Survival Guide, Bergisch Gladbach: Edition Humanistische Psychologie.

Schneck, O. (2007) ‘Cultural Due Diligence: Warum Unternehmensübernahmen scheitern’, Kredit & Rating Praxis, Vol. 4, pp. 23–29.

Smith, M. (2002) ‘Erskine workers await fate in wake of HP merger’, The Herald, 8 May.

Stachowicz-Stanusch, A. (2009) ‘Culture due diligence based on HP/Compaq Merger case study’, Journal of Intercultural Management, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 64–81.

Stahl, G. K. and Voigt, A. (2008) ‘Do cultural differences matter in mergers and acquisitions? A tentative model and examination’, Organization Science, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 160–176.

Stahl, G. K., Chua, C. H. and Pablo, A. L. (2012) ‘Does national context affect target firm employees’ trust in acquisitions?’, Management International Review, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 395–423.

Tam, P. (2002) ‘HP designs workshops to break postmerger ice’, Wall Street Journal, 11 July.

Vester, J. (2002) ‘Lessons learned about integration acquisitions’, Research Technology Management, Vol. 45, pp. 33–41.

Weber, Y., Tarba, S.Y. and Reichel, A. (2009) ‘International mergers and acquisitions performance revisited: The role of cultural distance and post-acquisition integration approach implementation’, Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions, Vol. 8, pp. 1–18.

Weber, Y., Tarba, S.Y. and Reichel, A. (2011) ‘A model of the influence of culture on integration approaches and international mergers and acquisitions performance’, International Studies of Management and Organization, Vol. 41, No.3, pp. 9–24.

Weber, Y., Tarba, S.Y. and Rozen Bachar, Z. (2011) ‘Mergers and acquisitions performance paradox: The mediating role of integration approach’, European Journal of International Management, Vol. 5, pp. 373–393.

Yin, R. K. (2009) Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th edition, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Zimmer, A. (2001) Unternehmenskultur und Cultural Due Diligence bei Mergers & Acquisitions, Aachen: Shaker Verlag.