From yes or no to why, when, and how

Florian Bauer, Andreas Strobl, and Kurt Matzler

Introduction

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) remain an essential strategy for corporate development, enabling many firms to cope with changing environments, markets, and technologies (Bauer and Matzler, 2014; Swaminathan et al., 2008; Weber and Drori, 2011). For example, in 2010 General Electric announced a plan to invest about US$30 billion over the next three years on acquisitions in order to cope with market developments. Like GE, other global players as well as medium-sized firms have spent billions of dollars on non-organic growth strategies (Jansen, 2008). This overall importance of M&A is demonstrated by the annual global transaction value that approximates the GDPs of large economies, such as Germany’s (e.g. GDP of Germany was US$3.8 billion in 2014; transaction volume in 2014 was US$3.6 billion). Even though the market for M&A is strongly cyclical – usually following global economic development – the overall importance of M&A is still increasing and we are currently entering a new boom period (Düsterhoff, 2015). One significant change since the M&A peak in 2000 is that a major part of M&A activity was among small- and medium-sized firms. After the economic downturn in 2007 and the subsequent downturn in the M&A market, M&A activity is now increasing again and cross-border deals are becoming increasingly important (Shimizu et al., 2004).

Due to their popularity, M&A transactions have received a lot of scientific and practical attention. However, despite some thousand studies and perhaps a hundred thousand papers on the topic, our understanding of the phenomenon is still limited and “M&A are still a puzzle for academics and practitioners” (Capasso and Meglio, 2005, p. 219) and their popularity is in contrast to their low success rates (Weber and Drori, 2011). While some research results seem intuitively and logically appealing, others are quite surprising, indicating a greater complexity behind the phenomenon. In a meta-analytic review of commonly analyzed success factors in M&A, namely the acquisition of conglomerates, of related firms, the method of payment, and prior acquisition experience, King and colleagues (2004) reached the conclusion that these variables only explain a minor portion of variance and that other variables influencing acquisition performance remain uncovered. Acquisition experience literature commonly draws a learning curve perspective, indicating that with an increasing amount of acquisitions, the post-merger performance (independent from its definition) increases (Kusewitt, 1985; Muehlfeld et al., 2012). It is argued that experienced acquirers can develop specific routines that make their acquisition processes more effective and thus lead to better performance (Barkema and Schijven, 2008). Even though this makes sense intuitively, the acquisition performance of experienced serial acquirers like Siemens or GE shows great variation, ranging from successful, to neutral, to value-destroying acquisitions. Siemens’ acquisition of Nixdorf (US$1,000 million) or Daimler and Chrysler (US$30,000 million) show that even highly experienced companies (so- called serial acquirers) can fail, whereas some acquisition greenhorns can succeed. The results from research reflect this variation (King et al., 2004). Some studies indicate a positive relationship between acquisition experience and performance (Barkema et al., 1996), whereas others suggest a negative (Kusewitt, 1985), a U-shaped (Haleblian and Finkelstein, 1999), an inverted U-shaped (Hayward, 2002), or a non-significant (Zollo and Singh, 2004) relationship. In the above-mentioned meta-analysis, King and colleagues (2004) conclude that there is no evidence for a significant relationship on a cumulative level. In this paper we draw a more fine- grained and nuanced perspective on acquisition experience, as we try to investigate why, when, and how acquisition experience can have beneficial or detrimental effects (see Table 13.1).

With empirical evidence from survey data of 115 acquisitions, several personal interviews with M&A managers, and acquisition consulting experience, we develop possible approaches for firms to benefit from prior experience. Further details on our research activity can be found in the box ‘About this research’. Due to confidentiality agreements, we are not allowed to give the names of any firms.

Table 13.1 Why, when (1), when (2), and how does experience matter?

| Why – an experience fit perspective |

Why the transfer of experience can have beneficial, neutral, or detrimental effects. |

| When – a process perspective |

When is experience beneficial? In which phases and for which specific tasks can experience be a trigger for value creation or destruction? |

| When – a structural perspective on non-organic growth |

When do growing pains and acute abdominal pain destroy value? When should firms implement counter-measures to avoid value-destroying crisis? |

| How – an experience knowledge transition perspective |

Experience and what then? How should firms use their experience? |

About this Research

Since 2009, we have focused on the topic of M&A from various perspectives, including strategy, organization, and processes. In total we have primary survey data on more than 800 individual acquisitions, several dozen interviews with managers responsible for and affected by M&A activities, and deep insights into acquisition programs as we have observed several acquirers during their acquisitions. For this chapter, we rely on two sources. First, we collected survey data on 115 transactions carried out within the German-speaking part of Europe between 2008 and 2011. The mail and internet survey was conducted in 2014 to ensure that each integration was complete or at least close to its final stage. Second, we gained insights from two acquirers we accompanied over the course of several acquisitions; additionally, we gained insights from interviews with managers in charge of the enterprises. Both data sources give fascinating insights into the so-called ‘Champions League’ of strategic and organizational management, namely M&A. Our research effort has improved our understanding of this complex phenomenon.

Does experience matter?

Why – an experience fit perspective

M&A-experience research is usually based on a learning curve perspective and the common measurement of experience is the number of transactions. At first glance, it seems logical that firms will gather valuable experience in closing deals and integrating targets and as a consequence will improve their acquisition performance as they increase their number of acquisitions (Ellis et al., 2011). Yet, this assumption has a major weakness. It ignores the type of experience that is gained and its usefulness in subsequent acquisitions. Until now there has been little research into the value and transferability of experience from one M&A transaction to the next.

One firm we observed during its first and several subsequent acquisitions, a medium-sized hidden champion from southern Germany, made its first acquisition in China in the course of developing new geographical markets. All executives and middle-management – besides their general respect for such an important strategic move – had a lot of respect for cultural and legal differences. This was maybe due to many cautionary tales of previous investments by well-known German firms in China (e.g. Steiff’s quality issues, and violations of intellectual property rights for Stihl).

We are aware of the situation. China is different. Many firms have failed after entering this exciting, big market. They have a different culture and a different behavior.

(Sales manager of the acquiring firm)

However, the acquisition went well and a year later the firm decided to pursue another. Its experience with cultural and institutional aspects of the acquisition, as well as the integration of sales channels and harmonization of marketing and brands, was transferred to the second acquisition, and it was even more successful than the first. As a consequence, a third acquisition was planned in India and the acquirer’s experience from the first two transactions proved to be beneficial again. The management team developed fine-grained routines and confidence over their acquisition management capabilities steadily increased.

We had an acquisition blueprint, a perfect and detailed acquisition project plan, and there was an atmosphere like in Frank Sinatra’s song “New York, New York”: if we can make it there, we’ll make it anywhere.

(CEO of the acquiring firm)

A fourth acquisition targeted a domestic firm for technology and resource purposes. Compared to the previous transactions, this promised to be straightforward, given the similar legal systems and cultural backgrounds of the target and the acquirer. However,

Our domestic deal seemed like a child’s play, but, hell, it ended in disaster.

(CFO of the acquiring firm)

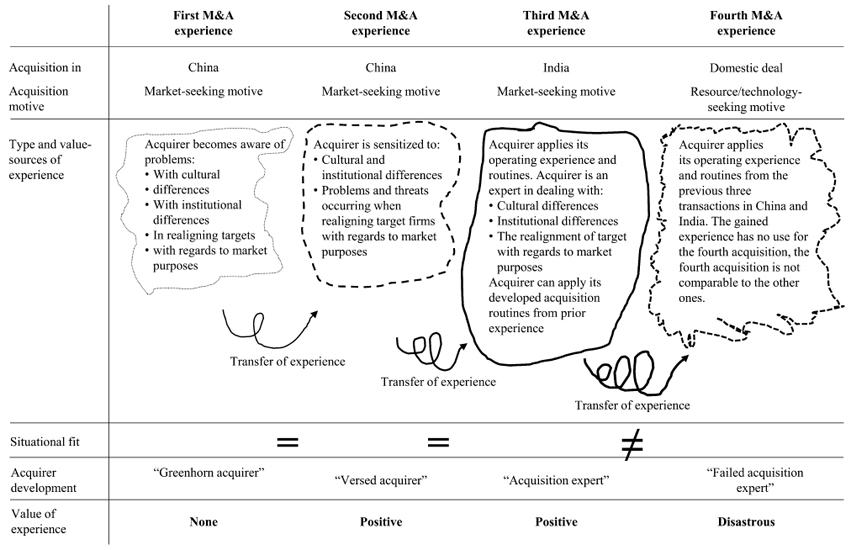

Figure 13.1 presents the company’s acquisition history.

What went wrong? Following the learning curve perspective, drawing from experience in countries (China and India) that were known to be difficult, the fourth acquisition should have been simple. Yet the opposite was the case. The transaction turned out to be a disaster. It would be easy to assume that this failure was rooted in overconfidence triggered by previous successes or due to narcissistic personalities in management seeking recognition (Billet and Qian, 2008). But if we take a closer look at the experience the company gained and then transferred to subsequent transactions, a generalization error can be detected. With its acquisitions in China, it became experienced in dealing with cultural and institutional differences, integrating sales channels, and transferring its marketing and brand reputation (with seals of quality like ‘Made in Germany’) across borders. This Chinese experience then proved valuable for the subsequent acquisition in India. Again, integrating distribution channels and transferring marketing know-how were core obstacles that had to be overcome. However, the domestic acquisition was different for several reasons. First, national/cultural or institutional differences were not an issue, so the firm’s experience in overcoming such obstacles had no value. Second, integrating sales channels and a one-way (from buyer to target) transfer of marketing and brand management practices is different from exchanging technological know-how and capabilities, which demands a bi-directional information and resource stream. Thus, during its three transnational transactions, the acquirer acted mainly as a sender, whereas during the domestic transition the acquirer suddenly had to act as both

sender and recipient simultaneously. As a consequence, the well-developed integration approaches that had worked so well in an international context with market-seeking motives now led to confused and unsatisfied employees, resistance, increased employee turnover, and ultimately a loss of know-how. “What was acquired was lost two years later,” the CEO commented.

This example demonstrates that a one-by-one transfer of routines developed through experience can be successful, problematic, or without any consequence in subsequent acquisitions, depending on the degree of fit between the initial and the subsequent transactions (Ellis et al., 2011). Thus, experience and knowledge transfer from one acquisition to the next must always take differences into account.

When (1) – a process perspective

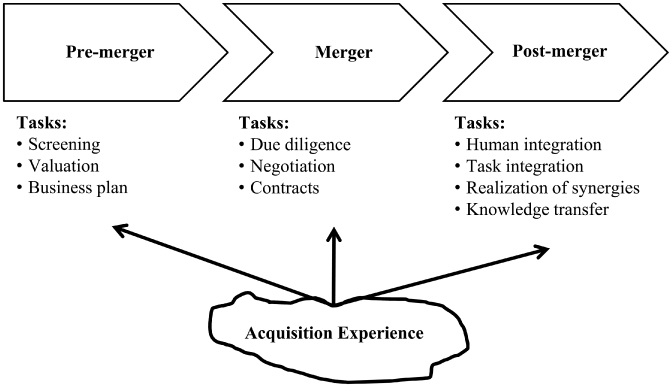

When equating acquisition experience to the number of transactions, we count an acquisition – from the initial idea to the accomplished integration (that is, between three to five years after a deal has been finalized) – as one experience “point” without understanding when – in which phases or with regards to which tasks – it matters. Here a more detailed perspective on different phases and corresponding tasks is beneficial. On a meta-level, there is general agreement that M&As consist of three phases: pre-merger; merger; and post-merger. Each of these phases consists of dozens of interrelated tasks that may not necessarily be treated as parallel activities. Each task can contribute to value creation if performed well or to value destruction if performed badly. Figure 13.2 displays the phases and some related tasks during acquisitions.

When talking about the use and the value of acquisition experience, we refer to the experience with specific tasks to be accomplished during the pre-merger, merger, or post-merger integration phase or specific routines (Barkema and Schijven, 2008). Thus, experienced acquirers perform specific acquisition-related tasks such as target screening, due diligence, or post-merger integration more efficiently and more effectively than others.

While specific tasks can be repeated in a similar way in every acquisition, other tasks require tailored approaches in every acquisition, and thus need to be treated like new, initial processes. While the development of business plans, target valuations (depending on the strategic rationale behind the transaction), or a due diligence request list could follow standardized routines based on prior acquisition experience, this turns out to be almost impossible when it comes to soft issues (e.g. issues related to company culture) or when humans are involved. These are usually the main differentiators between organizations and are often cited as the main obstacles (Blake and Mouton, 1985; Huselid et al., 1997; Weber et al., 2012). Even though the pre-merger and the merger phases require a lot of managerial know-how and resources, the clean-up begins on day two, immediately after the big party, when many firms are suffering from a hangover. The integration phase is decisive, as value creation or destruction takes place after closing the deal (Haspeslagh and Jemison, 1991). Many firms fail during integration or simply underestimate the required realignment efforts (Vester, 2002; Birkinshaw et al., 2000; Pablo, 1994). It is no wonder that Joe Kaeser (CEO of Siemens) aims to increase the performance of already acquired business units, where little attention has previously been paid to this. However, many individual but interrelated tasks must be performed to turn such a statement into an actual increase in performance. Integration is a highly complex, multi-dimensional (Shrivastava, 1986), long-term (e.g. Bauer and Matzler, 2014; Homburg and Bucerius, 2005, 2006) process, continuing for three to five years after the deal has been made (Homburg and Bucerius, 2006). Even though the harmonization of accounting and controlling (which is legally mandatory in most countries) as well as IT issues can be performed with well-developed routines based on experience, a standardized approach to other tasks – like human integration – can have disastrous consequences. Research results indicate that there is no generally applicable blueprint for integration strategies, and integration typologies lack empirical evidence (Angwin and Meadows, 2014). One reason might be that different acquisition motives require different levels of organizational autonomy and strategic interdependence that could occur in parallel in one acquisition (Zaheer et al., 2013). Additionally, targets usually differ from one another with regards to organizational culture, leadership-styles, and/or structures. Thus, the use of integration experience – beyond some specific tasks – is strongly case sensitive and depends on the strategic need for integration.

When (2) – much is too much – a structural perspective on non-organic growth

Firm growth goes hand in hand with structural, managerial, and organizational cultural transitions (Whetten, 1987; Flamholtz and Randle, 2007). And ggressive growth commonly leads to growing pains when non-organic growth strategies are pursued. A major issue here is that a firm’s structural growth mostly lags behind the pace of sales growth. When conducting many subsequent acquisitions, managers tend to neglect organizational structures as their focus is to grow without wasting resources on structural realignment, which is time consuming, expensive, and complex (Miles et al., 1978). Thus, structural realignment is perceived as an unaesthetic task. One Austrian firm we observed during its acquisition processes had the aim of achieving a global footprint as quickly as possible. The reasons were twofold: first, they wanted to spread their country market risk; and second, they wanted to grow. To some extent, they followed a bridgehead strategy – first entering a specific country, then starting to export to neighboring countries, and finally investing in the whole region with brownfield developments. They entered the Spanish market with the aim of developing a business division in south-west Europe (France, Spain, Portugal, and Italy) through the acquisition of the number two in the Spanish market. In a second step, headquarters managers screened the regional markets for subsequent brownfield investments. Within three years, eighteen acquisitions had been made and the target firms were mandated to the South-West Europe Division (S-WED), with its regional headquarters in the original bridgehead in Spain. Over the next three years, the division created a strong entrepreneurial spirit due to a high level of autonomy that was tolerated by the corporate headquarters, which was focusing on rapid non-organic growth in other regions at the time. The S-WED became a powerful actor in the firm’s network because it contributed a major share of European sales. As a consequence, it strived to maintain its autonomous position in the firm.

Our vision for the future is to keep autonomy for tying in with past success.

(S-WED executive)

This fairy tale of endless growth and success turned into a nightmare a few years later. The first indication of the upcoming storm came during 2012’s annual budget meeting, attended by divisional executives, the CEO, the CFO, and the COO at the firm’s headquarters in Austria. As a marginal side-note, the S-WED executive requested €10 million for an acquisition. The board members were blind-sided and demanded more information and some time to make a decision. However, the S-WED executive replied: “A ‘no’ is not acceptable. We have already signed a non-disclosure agreement, and have agreed on a transaction plan and a non-binding offer. What do you want from us? Shall we grow and develop or not?” Six months later, headquarters was in charge of the transaction process after reevaluating the target and renegotiating the deal. In an interview, the S-WED executive expressed his dismay at this course of events: “I lost face. No partner or employee will trust me in the future. My reputation is busted. The next time I buy a pencil, will the guys from headquarters come and tell me that I do not have their approval to spend ten cents?”

A major problem for this fast-growing firm was that its structures remained the same for a decade. While investing heavily in non-organic growth, headquarters missed the opportunity to establish clear responsibilities and realign and adapt the firm’s organizational structures to meet the needs of the emerging organization. What ensued was a painful but necessary restructuring process at the cost of S-WED’s autonomy.

How – an experience knowledge transition perspective

When talking about experience and its relationship to performance, the literature tends to oversimplify (Ellis et al., 2011). Acquisition experience can be transferred in either explicit or implicit acquisition knowledge. While explicit acquisition knowledge consists of recorded lessons learned, procedural instructions, and/or standardized management techniques (Dierkes et al., 2001; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Lam, 2000), tacit acquisition knowledge is rooted in individuals and its is not – or hardly – recordable (Nonaka and Van Krogh, 2009; Lam, 2000). Anyway, explicit and tacit acquisition knowledge are not opposite ends of a spectrum (Lam, 2000), and the interaction between and combination of the two are necessary (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995) to increase the likelihood to acquisition success.

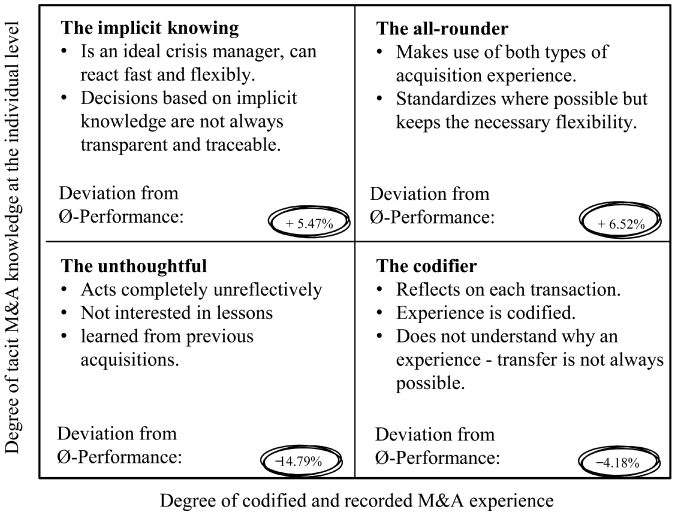

Figure 13.3 The effects of codified and recorded experience and tacit acquisition knowledge on M&A performance

Based on the results of a survey of 115 acquisitions, we developed four different types of acquirer with regards to their acquisition knowledge transition behavior (see Figure 13.3). To identify the different types of acquirer, acquisition knowledge transition was investigated along the dimension of degree of tacit M&A knowledge transition at the individual level and degree of codified and recorded M&A experience. Interestingly, from a statistical standpoint, the four types do not differ significantly in terms of previous M&A activity. The unthoughtful acquirer has never transformed its acquisition experience into either explicit or tacit acquisition knowledge. This unreflected approach causes strong negative effects (14.79 percent lower than other acquirers’ M&A performance). While inexperienced acquirers thoroughly analyze, plan, and manage their acquisitions, unthoughtful acquirers do not care and act impulsively.

Anyway, codification is not the ultimate route to success. Transforming acquisition experience only into explicit, codified knowledge limits managerial possibilities and required degrees of freedom in decision-making. As M&A processes are project management to its fullest extent, there is a clear need for flexibility to react quickly when unpredictable events and situations arise, whereas the strict application of rules destroys value, as is indicated by the codifier type’s negative deviation from average performance. In contrast to the codifier, the implicit knowing type can react quickly. This makes them ideal crisis managers that should be given sufficient scope for decision-making. However, although the results indicate above-average performance, their decisions lack transparency and could therefore cause organizational resistance. All-rounders achieve the best performance, as they balance codified and tacit acquisition knowledge. They implement transparent and standardized processes where possible, but allow for quick and unconventional decisions and solutions.

Implications

Experience can have a significant impact during acquisitions, but the acquisition experience–performance relationship is more complex than is often assumed. Acquisition experience can be both a blessing and a curse at the same time. In this section, we outline the implications of this for future research and practice.

Research implications

Recent research on acquisition experience has adopted a transfer theory perspective by arguing that not all acquisitions are alike (Ellis et al., 2011; Bower, 2001; Haleblian and Finkelstein, 1999). Our case example shows that transferring experience can have beneficial, neutral, or even detrimental effects. Thus, the situational fit between initial acquisition experience and a subsequent transaction is decisive (Haleblian and Finkelstein, 1999; Hayward, 2002). Our case demonstrated that there is no overall acquisition experience but rather specific experience with regards to specific tasks (Barkema and Schijven, 2008; Hayward, 2002). While task integration-related experiences can be transferable, human-related experiences are often untransferable. Anyway, acquisition experience is not easy to capture (Hayward, 2002); and even when it is captured, this is mostly done through simple proxies (Lord and Ranft, 2000), such as the number of acquisitions in a specific timeframe before the initial observation (Ellis et al., 2011; Haleblian and Finkelstein, 1999). However, secondary data might not provide the necessary richness of information, as acquisitions are not comparable. Thus, an in-depth analysis is needed to understand which routines can be transferred for which specific tasks without modification and which tasks need individual considerations for each acquisition. Consequently, a primary data research approach would be beneficial.

Another issue derives from the fact that we do not know how firms proceed with their experiences. The separation of explicit and tacit M&A knowledge was valuable as it showed diverging effects. Simple codification disregards heterogeneous circumstances, while the application of tacit knowledge leads to less transparency. Firms and managers that apply both types of knowledge have the highest probability of succeeding. Analysis of how firms assess their experience and how they transfer it into explicit and tacit knowledge could be a fruitful stream for improving our understanding of the effect of acquisition experience.

Finally, we believe that a process learning perspective would be useful. Acquisitions are not static events. Many parallel processes must be managed between target screening and final integration. The current research broadly ignores this complexity (Meglio and Risberg, 2010), but it would be valuable to understand the effects of experience during the process.

In addition to these implications for researchers, our work has several implications for managers.

Managerial implications

Managers must be aware of the various effects of acquisition experience. Our research reveals that firms can make use of this experience and avoid traps if it is utilized carefully. First, a situational fit of previous and subsequent acquisitions is a decisive antecedent if experience is transferable in a beneficial way. Next to organizational issues such as target size, age, and structure, managers should concentrate on the strategic rationale of the acquisition. If individual acquisitions are not comparable, managers should treat eahc of them as a discrete process and not in a “we have always done it this way” manner. Second, experience should not be assessed solely in terms of the number of previous acquisitions, as experience is not necessarily relevant to the whole M&A project. Rather, experience matters only with respect to specific tasks, and top performers have well-developed routines for some tasks but display flexibility with respect to others in the M&A process. Managers would be well advised to reflect on their past acquisitions to identify which tasks belong in which category. Third, non-organic growth can be beneficial as it allows for quick growth, market entry, and technology gain, but organizations are complex systems and if specific issues are changed or adapted, other things have to be changed or adapted, too. To avoid growing pains, managers should pay attention to and address the time-consuming, expensive, and unaesthetic task of structural realignment. Growing through acquisitions is merely the qualification for the Champions League. True champions achieve sustainable advantages as they prepare their organizations for managing growth. Fourth, experience can matter, but firms need to transform their acquisition experience into acquisition knowledge. In doing so, they should be aware that checklists, recorded lessons learned, procedural instructions, and/or standardized management techniques are not always the best options. They can alleviate the organizational pain that is often associated with non-organic growth strategies by providing guidelines during the process. M&A management is the epitome of project management, and unforeseeable events happen on a daily basis. Thus, firms must allow their managers to be flexible in their decision-making. Top-performing acquirers always establish a balance between standardized processes and flexibility.

To conclude, an oversimplistic appraisal of acquisition experience can lead to disastrous results. Firms and managers must be aware of the complex interdependencies of acquisition experience. Additionally, those that rely solely on their experience will fail, as experience must be transformed in acquisition knowledge. Once again, the reality is more complex than is often assumed, and firms should reflect on their past acquisitions to identify those tasks that can be standardized and those that need to be addressed on an individual basis. Careful assessment of each individual acquisition is crucial, too. We trust that our research will help firms and managers to appreciate the complex nature of acquisition experience, and allow them to make the most of that experience.

References

Angwin, D., and Meadows, M. (2014). New integration strategies for post-acquisition management. Long Range Planning, 48(4), pp. 235–251.

Barkema, H. G., and Schijven, M. (2008). How do firms learn to make acquisitions? A review of past research and an agenda for the future. Journal of Management, 30(4), pp. 594–634.

Barkema, H. G., Bell, J., and Pennings, J. M. (1996). Foreign entry, cultural barriers, and learning. Strategic Management Journal, 17, pp. 151–166.

Bauer, F., and Matzler, K. (2014). Antecedents of M&Amp;A success: The role of strategic complementarity, cultural fit, and degree and speed of integration. Strategic Management Journal, 35(2), pp. 269–291.

Bijlsma-Frankema, K. (2001). On managing cutural integration and cultural change processes in mergers and acquisitions. Journal of European Industrial Training, 25, pp. 192–207.

Billet, M., and Qian, Y. (2008). Are overconfident CEOs born or made? Evidence of self-attribution bias from frequent acquirers. Management Science, 54(6), pp. 1037–1051.

Birkinshaw, J., Bresman, H., and Hakanson, L. (2000). Managing the post-acquisition integration process: How human integration and task integration processes interact to foster value creation. Journal of Management Studies, 37(3), pp. 365–425.

Blake, R., and Mouton, J. (1985). How to achieve integration on the human side of the merger. Organization Dynamics, 13(3), pp. 41–56.

Bower, J. (2001). Not all M&Amp;As are alike – and that matters. Harvard Business Review, 79, pp. 92–102.

Capasso, A., and Meglio, O. (2005). Knowledge transfer in mergers and acquisitions: How frequent acquirers learn to manage the integration process. In A. Capasso, G. B. Dagnino, and A. Lanza (eds.), Strategic capabilities and knowledge transfer within and between organizations (pp. 199–225). Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Chakravorty, J. (2012). Why do mergers and acquisitions quite often fail? Advances in Management, 5(5), pp. 21–28.

Cording, M., Christman, P., and King, D. (2008). Reducing causal ambiguity in acquisition integration: Intermediate goals as mediators of integration decisions and acquisition performance. Academy of Management Journal, 51(4), pp. 744–767.

Dierkes, M., Berthoin Antal, A., Child, J., and Nonaka, I. (2001). Handbook of organizational learning and knowledge. New York: Oxford University Press.

Düsterhoff, H. (2015). Wende ja, welle nein: Jahresrückblick auf das deutsche M&Amp;A – Geschehen 2014. M&Amp;A Review, 26(2), pp. 73–81.

Ellis, K., Reus, T., Lamont, B., and Ranft, A. (2011). Transfer effects in large acquisitions: How size specific experience matters. Academy of Management Journal, 6, pp. 1261–1276.

Finkelstein, S., and Halebian, J. (2002). Understanding acquisition performance: The role of transfer effects. Organization Science, 13(1), pp. 36–47.

Flamholtz, E., and Randle, Y. (2007). Growing pains: Transitioning from an entrepreneurship to a professionally managed firm. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Haleblian, J., and Finkelstein, S. (1999). The influence of organizational acquisition experience on acquisition performance: A behavioral learning perspective. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, pp. 29–56.

Haspeslagh, P. C., and Jemison, D. B. (1991). Managing acquisitions. New York: The Free Press.

Hayward, M. (2002). When do firms learn from their acauisition experience? Evidence from 1990–1995. Strategic Management Journal, 23(1), pp. 21–39.

Homburg, C., and Bucerius, M. (2005). A marketing perspective on mergers and acquisitions: How marketing integration affects postmerger performance. Journal of Marketing, 69, pp. 96–113.

Homburg, C., and Bucerius, M. (2006). Is speed of integration really a success factor of mergers and acquisitions? An analysis of the role of internal and external relatedness. Strategic Management Journal, 27, pp. 347–367.

Huselid, M., Jackson, S., and Schuler, R. (1997). Technical and strategic human resource management effectivness as determinants of firm performance. Academy of Management Journal, 40(1), pp. 171–188.

Jansen, S. A. (2008). Mergers and acquisitions. 5th edition. Wiesbaden: Gabler Verlag.

King, D. E., Dalton, D. R., Daily, C. M., and Covin, J. G. (2004). Meta-analyses of post-acquisition performance: Indications of unidentified moderators. Strategic Management Journal, 25, pp. 187–200.

Kusewitt, J. J. (1985). An exploratory study of strategic acquisition factors relating to performance. Strategic Management Journal, 6, pp. 151–169.

Lam, A. (2000). Tacit knowledge, organizational learnuing and societal institutions: An integrated framework. Organization Studies, 21(3), pp. 487–513.

Lord, M., and Ranft, A. (2000). Organizational learning about new international markets: Exploring the internal transfer of local market knowledge. Journal of International Business Studies, 31(4), pp. 573–589.

Meglio, O., and Risberg, A. (2010). Mergers and acquisitions: Time for a methodological rejuvenation in the field? Scandinavian Journal of Management, 26, pp. 87–95.

Miles, R., Snow, C., Meyer, A., and Coleman Jr., H. (1978). Organizational strategy, structure, and processes. Academy of Management Review, 3(3), pp. 546–562.

Muehlfeld, K., Sahib, P., and Van Witteloostuijn, A. (2012). Contextual theory of organizational learning from failures and successes: A study of acquisition completion in the global newspaper industry, 1981–2008. Strategic Management Journal, 33, pp. 938–964.

Nonaka, I., and Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nonaka, I., and Von Krogh, G. (2009). Tacit knowledge and knowledge conversion: Controversy and advancement in organizational knowledge creation theory. Organization Science, 20(3), pp. 635–652.

Pablo, A. (1994). Determinants of acquisition integration level: A decision making perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 37(4), pp. 803–836.

Shimizu, K., Hitt, M., Vaidyanath, D., and Pisano, V. (2004). Theoretical foundations of cross-border mergers and acquisitions: A review of current research and recommendations for the future. Journal of International Management, 10, pp. 307–353.

Shrivastava, P. (1986). Postmerger integration. Journal of Business Strategy, 7(1), pp. 65–76.

Swaminathan, V., Murshed, F., and Hulland, J. (2008). Value creation following merger and acquisition announcements: The role of strategic emphasis alignment. Journal of Marketing Research, 45, pp. 33–47.

Vester, J. (2002). Lessons learned about integrating acquisitions. Research Technology Management, 45, pp. 33–41.

Weber, Y. T. (2011). A model of the influence of culture on integration approaches and international mergers and acquisitions performance. International Studies of Management and Organization, 41(3), pp. 9–24.

Weber, Y., and Drori, I. (2011). Integrating organizational and human behaviour perspectives in mergers and acquisitions. International Studies of Management and Organization, 41 (3), pp. 73–95.

Weber, Y., Rachman-Moore, D., and Tarba, S. (2012). HR practices during post-merger conflict and merger performance. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 12(1), pp. 73–99.

Whetten, D. (1987). Organizational growth and decline processes. Annual Review of Sociology, 13, pp. 335–358.

Zaheer, A., Castaner, X., and Souder, D. (2013). Synergy sources, target autonomy, and integration in acquisitions. Journal of Management, 39(3), pp. 604–632.

Zollo, M., and Singh, H. (2004). Deliberate learning in corporate acquisitions: Post-acquisition strategies and integration cpability in US bank mergers. Strategic Management Journal, 25, pp. 1233–1256.