Analysis of pre-merger press announcements and post-merger interviews

Agyenim Boateng, George Lordofos, and Keith W. Glaister

The motivation for mergers and acquisitions (M&As) has been a topic of immense interest to academics and practitioners over the past two decades. This interest stems from the various empirical findings which suggest that more than two-thirds of all M&A deals are financial failures when measured in terms of their ability to deliver profitability (Ravenscraft and Scherer, 1987; Tetenbaum, 1999; Hudson and Barnfield, 2001). In a more board context, prior studies suggest that the ability of M&As to create value for acquiring shareholders has been mixed. One stream of research has reported significant positive returns for acquirers (see, Kang, 1993; Markides and Ittner, 1994; Kiymaz, 2003). Other studies have found negative and insignificant bidders’ returns (Eun, Kolodny and Scheraga, 1996; Datta and Puia, 1995; Aw and Chatterjee, 2004). Studies such as those by Erez-Rein et al. (2004) and Carleton (1997) have noted that M&As, generally fail to meet their anticipated goals. Despite the apparent failure of many M&As, we continue to see a rising trend in this activity. For example, UNCTAD (2006) reported that over 80 percent of world foreign direct investments (FDI) are carried out via cross-border M&As.

The above empirical evidence raises the question as to why companies persist with M&A transactions, given the solid evidence of their relative failure. The paradox of whether M&As create value for the acquiring firms is central to the study of M&As. Yet a number of the studies that have attempted to examine the motives for M&As by surveying senior managers have encountered some methodological criticism. It is argued that studies that rely on an ex post assessment of senior managers’ opinions are flawed due to self-justification or social desirability bias. The latter, defined as a tendency of the respondent to present him/herself in a favorable light (Nunnally, 1978), has been recognized as a major problem that can adversely affect the validity of studies in social science disciplines (see Neeley and Cronley, 2004; Fisher, 1993; Bruner, 2002). Researchers such as Fisher (2000) and Mick (1996) have called for increased attention to social desirability bias in design, measure construction, and analysis.

Given the high rate of failure for M&As to meet their anticipated goals, it is important to ask why a chief executive officer (CEO) should give correct answers to questions concerning the motives for M&A when the M&A has failed to deliver the anticipated outcomes of the M&A transaction. The main focus of this study is to shed light on the above question by examining the effects of social desirability bias by carrying out correlational analysis on the pre-merger and post-merger motivation for M&A in eight European countries. We do so by examining senior managers’ opinions regarding the motives for the M&A post-M&A and compare these responses with data collected from secondary sources (press reports) at the time of the M&A announcement. We undertake this procedure in order to shed light on the reliability of data provided by senior managers through interviews after the M&A.

This chapter contributes to the literature in two important ways. First, the study adds to the discussion of the effects of social desirability bias in M&A research by comparing the differences between motives given in interviews with senior managers and motives identified in press reports published at the time of the M&A announcement. Such triangulation linking data on motivation prior to and following the M&A has been reported only rarely in the finance and strategic management literature. Second, this approach provides a potentially fruitful way of shedding light on the reliability of studies that use managers’ ex post assessments of M&As, which are common in strategic management and marketing research.

The rest of the chapter is organized into four sections. The first of these briefly reviews the relevant literature and develops the hypothesis of the study. The next sets out the research method and sample characteristics. Then we present the findings and discussion. Finally, we discuss the implications for management and present our conclusions.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Literature review

Self-report questionnaires are commonly used in social science research for a number of reasons, including convenience, ease of use, and low cost. They are often also an effective way of measuring unobservable attributes, such as values, preferences, intentions, perceptions, and opinions about particular issues (Ganster, Hennessey and Luthans, 1983; De Jong, Pieters and Fox, 2010; Kim and Kim, 2016). In attempting to identify the motives for M&As, researchers commonly ask respondents to complete questionnaires containing questions with Likert-scale type responses. However, answers to questions on motives for acquisitions with Likert-scale type responses are often susceptible to social desirability bias due to the respondents’ tendency to answer in a more socially acceptable way (Fisher, 1993; Neeley and Cronley, 2004).

Prior literature suggests that social desirability bias may take two forms: self-deceptive enhancement and impression management (Zerbe and Paulhus, 1987; Paulhus, 1984, 1991). Self-deceptive enhancement refers to the tendency to describe oneself in an inflated – albeit honestly held – manner and to see oneself in a positive, overconfident light. This type of bias is driven by the desire to see oneself as competent and self-reliant, to protect self-beliefs, and to hold off anxiety and depression (Kim and Kim, 2016). Paulhus (1986) argues that because of optimism and positivistic bias, the self-deceiver is more likely to say good things about him/herself, and report inflated or overconfident views of his/her skills and capabilities.

In comparison, impression management describes respondents’ attempts to distort their self-reported actions in a positive manner to maintain a favorable image (Paulhus, 1984). Impression management is associated with the desire to portray oneself in a socially conventional way (Paulhus, 1991). Respondents act in this way to save face and maintain social approval (Lalwani, Shavitt and Johnson, 2006).

The distortion occurs through both self-deception and impression management (Barrick and Mount, 1996).

Nyaw and Ng (1994) and Paulhus (1991) point out that when research does not control for social desirability bias, the validity of findings may be questioned. Social desirability bias poses a major threat to construct validity, making it unclear whether measures actually represent their intended constructs (Cote and Buckley, 1987). In short, construct invalidity directly leads to inferential problems, depending on the validity of other measures. Supporting the above line of thinking, Ganster, Hennessey and Luthans (1983) argue that social desirability bias may understate the relationship between two or more variables (suppressor effect), provide an inflated correlation between independent and dependent variables (spurious effect), or moderate the relationship between those variables (moderator effect). Fisher (1993) notes that research that does not recognize and compensate for social desirability bias may lead to unwarranted theoretical or practical conclusions.

It is pertinent to point out that social desirability bias has been found in virtually all types of self-reporting measures and across the social science literature (Zerbe and Paulhus, 1987), and M&A studies are no exception (see Bruner, 2002).

The literature suggests that attempts to check for social desirability bias after the data have been collected include social desirability response (SDR) scales, such as the Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MCSDS)1 and the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (BIDR),2 applied mostly in marketing (see Mick, 1996; Podsakoff et al., 2003; Steenkamp, De Jong and Baumgartner, 2010). However, the use of SDR scales has been challenged (Paulhus, 2002; Smith and Ellingson, 2002). Scholars point to the difficulty of separating valid personality content in the SDR measures from the bias they are meant to measure. Other researchers, such as Aguinis, Pierce and Quigley (1993), Fisher (1993), Hill, Dill and Davenport (1988), Jones and Sigall (1971), Roese and Jamieson (1993); Tourangeau and Smith (1996), suggest the use of indirect questioning and bogus pipeline techniques3 to prevent SDR from biasing the measures in the first place. While such approaches may partially alleviate SDR, the effectiveness of these techniques is limited because they may introduce other biases (indirect questions), and their implementation may be expensive and prone to ethical issues (bogus pipeline) (Tourangeau, Rips and Rasinski, 2000).

Hypothesis development

A number of studies have been conducted on the motivation for M&As by examining ex post assessments of senior managers’ opinions regarding the motives for M&As (see Walter and Barney, 1990; Mukherjee, Kiymaz and Baker, 2004). These studies have relied solely on senior managers’ opinions after the M&A has taken place. As far as we are aware, no published study has identified motives at the time of the M&A announcement and compared them with the rationales given post-merger, using both secondary and primary data sources. Comparing the motives given for M&As from data sources (press reports) available at the time of the announcement with motives given in post-merger interviews with senior managers provides a way of assessing the reliability of primary data obtained from managers post-M&A.

It is argued that studies relying on senior managers’ opinions obtained after the merger or acquisition has occurred may be flawed (Walter and Barney, 1990). Reasons given by researchers such as Goldberg (1983) suggest that managers may not provide accurate responses because of self-justification or social desirability. Another argument put forward by critics is that, due to memory decay, managers may have forgotten the real motives for the M&As and may therefore give inaccurate information (Bruner, 2002). Moreover, managers who are aware of the motives at the time of the deal may have left the company and so responses provided by current managers with limited information may be misleading or inaccurate. Such problems impair the credibility of the data collected from senior managers after the M&As have taken place.

Despite these potential problems, it may also be maintained that senior managers are responsible officials and are best placed to answer strategic questions related to M&As. Mergers and acquisitions are important strategic decisions and therefore the motives for engaging in them are likely to persist in the memories of those responsible for making those decisions. Glaister and Buckley (1996) make this argument in connection with the motives for the formation of international joint ventures. Moreover, official company minutes and records would be kept on the discussions and deliberations of senior executives relating to such crucial investment decisions. This means that if the senior managers who were responsible for taking the M&A decision have left the company, current managers should have records on which to base their answers.

In light of this discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

There will be no difference between the motives given by senior managers for the M&A published in press reports at the time of the deal announcement and the motives provided by senior managers for the same M&A obtained by direct data collection some time after the M&A has been completed.

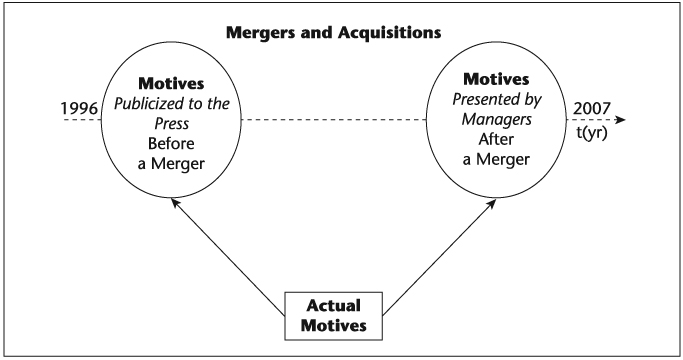

The conceptual model shown in Figure 2.1 illustrates the hypothesis that motives identified at the pre-M&A and post-M&A stages will be identical, irrespective of the time gap between the announcement of the M&A and the collection of data in interviews.

Research method

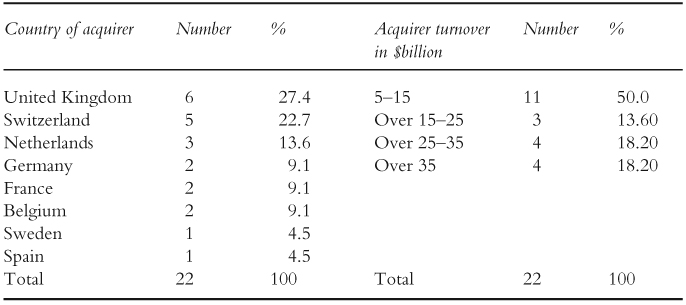

This study involves M&As from eight European countries which were initiated and completed over the period 1996–2007. The sampling frame for the study was derived from published reports of M&As in Chemical Market Reporter (6/3/2000, 19/8/2002, 23/2/2004), Chemical Engineering News (16/12/2002), the Financial Times, and Hoover’s Online. Two techniques were employed to collect the data: namely, secondary sources and interviews. First, from the press reports, we selected 22 benchmark companies that provided a good cross-section from the sampling frame. Data were collected in respect of the motives for 22 M&As which occurred in different time periods in 8 European countries from the press announcements in the Financial Times, Chemical Market Reporter, company press releases, and reports made at the time of the M&A announcement.

In the second phase of the data collection process, we used a multiple interview approach involving two senior officials of each of the 22 M&As. The design of the questions for the interviews was based on the aims of the study and literature review. The questionnaire for the interviews was divided into two main parts: the first part was concerned with the company’s background (e.g. products, markets, and size); the second part contained questions on the motives for the company’s decision to engage in the M&A. To encourage the respondents to disclose an accurate set of motives for the M&A, we assured them of confidentiality, told them that the information provided would be used only for academic purposes, and explained that the names of the managers would not be disclosed when the results were published.

Between 2000 and 2008, 44 open and semi-structured interviews, 95 percent by telephone and 5 percent personal, were conducted to elicit data from the senior managers of the same 22 benchmark companies in the 8 European countries.

Sample

The characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 2.1. The respondents were key decision-makers involved in the M&As. An examination of the job titles of the respondents revealed: 15.6 percent were senior managers in charge of mergers and acquisitions; 25 percent were finance directors; 31.2 percent were managing directors; 18.8 percent were others, including R&D managers, vice- president, chief technology officer, and vice-chairman; and 9.4 percent were corporate communication directors. It is likely that these respondents were not only familiar with the acquisition strategy but were involved in strategic decisionmaking relating to the M&As of their respective companies. We carried out the interviews with the 44 respondents (2 from each of the 22 M&As) between 2000 and 2008 with respect to M&As that occurred between 1996 and 2007. Each interview lasted between 30 and 45 minutes and was recorded, allowing the researchers to pay more attention to the respondents and to ask supplementary questions in light of their answers.

Analysis

All the interviews and the secondary data from the press announcements were analysed by building categories. We applied the rules of ‘pattern matching’ and comparative methods to draw conclusions (Yin, 1994; Miles and Huberman, 1994). To derive further in-depth inferences, the complex relationships among the variables were studied for each M&A, using the content-analysis and explanation-building modes of analysis. The individual motives were classified and awarded scores depending on the emphasis given to them for the M&A formation at the time of announcement and during the interviews. The assigned scores were:

- 1 = not mentioned;

- 2 = important;

- 3 = very important.

A two sample t-test was implemented to test for differences in means of the importance of the motives for the M&As between the two data sources.

Findings

Motivation for M&As: secondary data and primary data compared

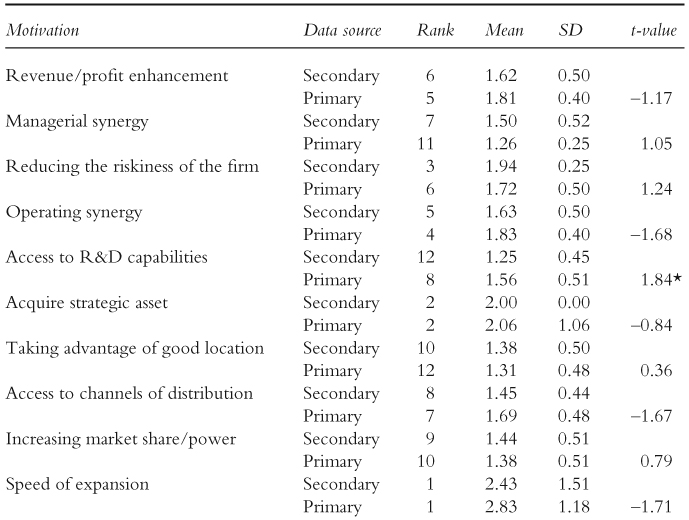

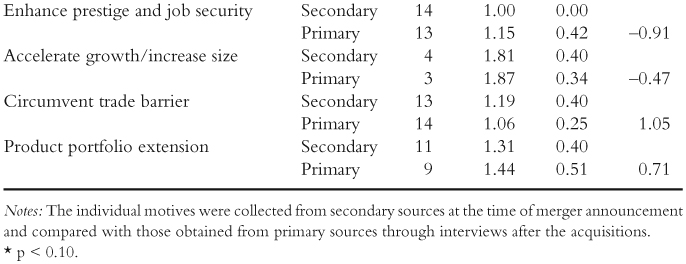

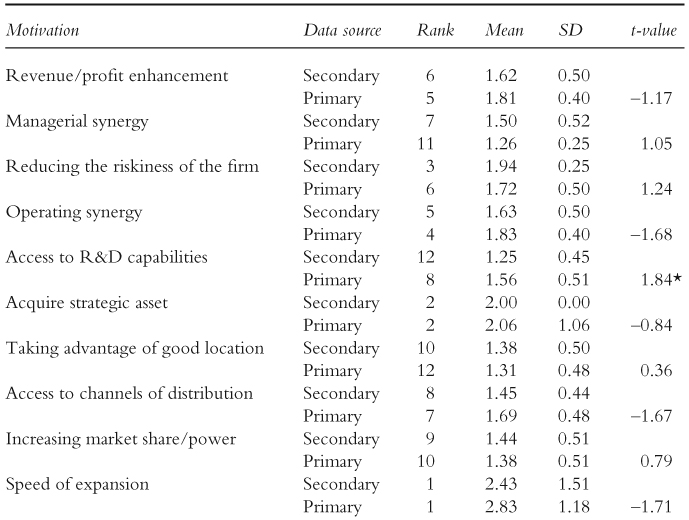

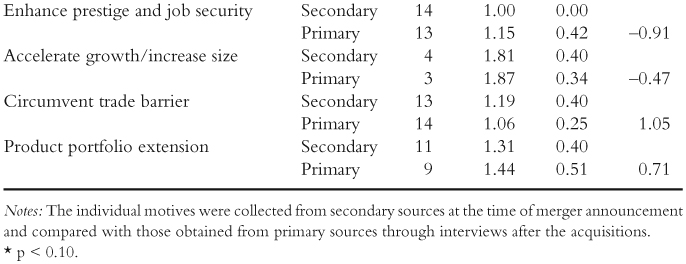

The analysis of the differences between secondary data (press) and primary data (post-merger interviews) is shown in Table 2.2. The rank order of the motivation for M&A formation based on the mean measure of the importance of 14 motives is also shown Table 2.2. For the full set of motives for mergers and acquisitions from secondary data, the median measure is exceeded by seven motives: speed of expansion (2.43); acquire strategic asset (2.00); reduce riskiness of the firm (1.94);

Table 2.2 Motives for M&As in European firms: secondary data versus primary data

accelerate growth/increase size (1.81); operating synergy (1.63); revenue/profit enhancement (1.62); and managerial synergy (1.50). For the primary data, the median measure is exceeded by eight motives: speed of expansion (2.83); acquire strategic asset (2.06); accelerate growth/increase size (1.87); operating synergy (1.83); revenue/profit enhancement (1.81); reduce riskiness of the firm (1.72); access to channels of distribution (1.69); and access to R&D capabilities (1.56). Both data sources indicate that ‘faster entry into new market’ and acquiring strategic assets are the highest-ranked motives.

The t-test results indicate that there is only one significant difference (p < 0.10) between the mean scores of the motives announced in the press prior to the merger deals and the information provided by senior managers in interviews after the deals. This renders strong support to our hypothesis. Moreover, this finding provides strong justification for relying on information provided by senior managers during interviews regarding the motives for mergers and acquisitions.

Conclusions and implications

The past four decades have witnessed an increasing volume of cross-border M&A activity. Commensurate with the rising volume of M&As has been the number of studies attempting to explain why M&As take place against a backdrop of prior studies that suggest the failure rate of M&As ranges between 46 and 82 percent (see Kitching, 1967; Jensen and Ruback, 1983; Hunt, 1990; Jarrell and Poulsen, 1984). Most prior studies have investigated the motives for M&As using data based on the opinions of senior managers (see Walter and Barney, 1990; Ingham, Kran and Lovestam, 1992; Brouthers, Hastenburg and Van den Ven, 1998; Boateng and Bjortuft, 2003). In contrast, this study uses data collected from secondary sources (press reports) at the time of merger announcements and then compares them with data based on the opinions of senior managers interviewed after the M&A deals. Such triangulation is rarely tested empirically in the finance and strategic management literature. We find that, with the exception of one motive, there are no significant differences between the means of the motives from each data source. This finding, therefore, renders support for our hypothesis.

The conclusion to be drawn is that primary data based on the ex post assessment of the opinions of senior managers are valid and reliable. This is contrary to the views of some critics who have claimed that studies using data from such sources are flawed. The implications of this research are that studies relying on ex post assessment of senior managers’ opinions relating to the motives for M&A formation are sound and that such studies are unlikely to suffer from social desirability bias.

Notes

References

Aguinis, H. and Handelsman, M. M. (1997). Ethical issues in the use of the Bogus Pipeline, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27 (7), 557–573.

Aguinis, H. and Henle, C. A. (2001). Empirical assessment of the ethics of the Bogus Pipeline, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31 (2), 352–375.

Aguinis, H., Pierce, C. A. and Quigley, B. M. (1993). Conditions under which a Bogus Pipeline procedure enhances the validity of self-reported cigarette smoking: a meta-analytic review, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 352–373.

Aw, M. and Chatterjee, R. (2004). The performance of UK firms acquiring large cross-border and domestic takeover targets, Applied Financial Economics, 14, 337–349.

Barrick, M. R. and Mount, M. K. (1996). Effects of impression management and self deception on the predictive validity of personality constructs, Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 261–272.

Boateng, A. and Bjortuft, V. (2003). An analysis of motives for mergers and acquisitions: evidence from Norway, paper deliver at the BAM Conference, Harrogate, UK.

Brouthers, K., Hastenburg P. V. and Van den Van, J. (1998). If most mergers fail why are they so popular?, Long Range Planning, 31(3), 347–358.

Bruner, R. F. (2002). Does M&Amp;A pay? A survey of evidence for the decision- maker, Journal of Applied Finance, Spring/Summer, 48–68.

Carleton, R. J. (1997). Cultural due diligence, Training, 34, 67–80.

Cote, J. A. and Buckley, M. R. (1987). Estimating trait, method, and error variance: generalizing across 70 construct validation studies. Journal of Marketing Research, 24, 315–318.

Datta, D. K. and Puia, G. (1995). Cross-border acquisitions: an examination of the influence of relatedness and cultural fit on shareholder value creation in US acquiring firms, Management International Review, 35 (4), 337–359.

De Jong, M. J., Pieters, R. and Fox, J.-P. (2010). Reducing social desirability bias through item randomized response: an application to measure underreported desires, Journal of Marketing Research, 47, 14–27.

Erez-Rein, N., Erez, M. and Maital, S. (2004). Mind the gap: key success factors in cross-border acquisitions, in A. L. Pablo and M. Javidan (eds.), Mergers and Acquisitions: Creating Integrative Knowledge, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Eun, C. S., Kolodny, R. and Scheraga, C. (1996). Cross-border acquisitions and shareholder wealth: tests of the synergy and internalization hypotheses, Journal of Banking and Finance, 20, 1559–1582.

Fisher, R. J. (1993). Social desirability bias and validity of indirect questioning, Journal of Consumer Research, 20, 303–315.

Fisher, R. J. (2000). The future of social desirability bias, Psychology and Marketing, 17 (2), 73–77.

Ganster, D. C., Hennessey, H. W. and Luthans, F. (1983). Social desirability response effects: three alternative models, Academy of Management Journal, 26, 321–331.

Glaister, K.W and Buckley, P. J. (1996). Strategic motives for international alliance formation, Journal of Management Studies, 33 (3), 301–332.

Goldberg, W. H. (1983). Mergers: Motives, Modes, Methods, Aldershot: Gower.

Hill, P. C., Dill, C. A. and Davenport, E. C. (1988). A reexamination of the Bogus Pipeline, Educational and Psychological Measurement, 48 (3), 587–601.

Hudson, J. and Barnfield, E. (2001). Mergers and acquisitions requires social dialogue, Strategic Communications Management, 5, 207–239.

Hunt, J. (1990). Changing pattern of acquisition behaviour in takeovers and consequencies for acquisition process, Strategic Management Journal, 11, 66–71.

Ingham H., Kran I. and Lovestam, A. (1992). Mergers and profitability: a managerial success story, Journal of Management Studies, 29 (2), 195–209.

Jarrell, G. A. and Poulsen, A. B. (1994). The returns to acquiring firms in tender offers: evidence from three decades, in P. Gaughan (ed.), Readings in mergers and acquisitions, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Jensen, M. C. and Ruback, R. S. (1983). The market for corporate control: the scientific evidence, Journal of Financial Economics, 11, 5–50.

Jones, E. E. and Sigall, H. (1971). The Bogus Pipeline: a new paradigm for measuring affect and attitude, Psychological Bulletin, 76, 349–364.

Kang, J. K. (1993). The international market for corporate control: mergers and acquisitions of US firms by Japanese firms, Journal of Financial Economics, 34, 345–371.

Kim, S. H. and Kim, S. (2016). National culture and social desirability bias in measuring public service motivation, Administration and Society, 48 (4), 444–476.

Kitching, J. (1967). Why do mergers miscarry?, Harvard Business Review, November–December, 84–101.

Kiymaz, H. (2003). Wealth effect for US acquirers from foreign direct investments, Journal of Business Strategies, 20 (1), 7–21.

Lalwani, A. K., Shavitt, S. and Johnson, T. (2006). What is the relation between cultural orientation and socially desirable responding?, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 165–178.

Lalwani, A. K., Shrum, L. J. and Chiu, C.-Y. (2009). Motivated response styles: the role of cultural values, regulatory focus, and self-consciousness in socially desirable responding, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 870–882.

Markides, C. and Ittner, C. D. (1994). Shareholders benefit from corporate international diversification: evidence from US international acquisitions, Journal of International Business Studies, 25 (2), 343–366.

Mick, D. G. (1996). Are studies of dark side variables confounded by socially desirable responding? The case of materialism, Journal of Consumer Research, 23, 106–119.

Miles, M. and Huberman, A. (1994). A Qualitative Data Analysis, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Mukherjee T. K., Kiymaz H. and Baker K. H. (2004). Merger motives and target valuation: a survey of evidence from CFOs, Journal of Applied Finance, 14 (2), 7–24.

Neeley, S. M. and Cronley, M. L. (2004). When research participants don’t tell it like it is: pinpointing the effects of social desirability bias using self vs. indirect-questioning, Advances in Consumer Research, 31, 432–433.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric Theory, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Nyaw, M.-K. and Ng, I. (1994). A comparative analysis of ethical beliefs: a four country study, Journal of Business Ethics, 13, 543–555.

Paulhus, D. L. (1984). Two-component models of socially desirable responding, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 598–609.

Paulhus, D. L. (1986). Self-deception and impression management in test responses, in A. Angleitner and J. S. Wiggins (eds.), Personality Assessment via Questionnaire, New York: Springer.

Paulhus, D. L. (1991). Measurement and control of response bias, in J. P. Robinson, P. Shaver and L. S. Wrightsman (eds.), Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes, San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Paulhus, D. L. (2002). Social desirability responding: the evolution of a construct, in H. I. Braun, D. N. Jackson and D. E. Wiley (eds.), The Role of Constructs in Psychological and Educational Measurement, London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies, Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Ravenscraft, D. J. and Scherer, F. M. (1987). Mergers, Sell-offs and Economic Efficiency, Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Roese, N. J. and Jamieson, D. W. (1993). Twenty years of Bogus Pipeline research: a critical review and meta-analysis, Psychological Bulletin, 114 (2), 363–375.

Smith, D. B. and Ellingson, J. E. (2002). Substance versus style: a new look at social desirability in motivating contexts, Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 211–219.

Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M., de Jong, M. G. and Baumgartner, H. (2010). Socially desirable response tendencies in survey research, Journal of Marketing Research, 47 (2), 199–214.

Sudman, S. and Bradburn, N. M. (1974). Response Effects in Surveys: A Review and Synthesis, Chicago: Aldine.

Tetenbaum, T. J. (1999). Beating the odds of mergers and acquisition failure: seven key practices that improve the chance for expected integration and synergies, Organizational Dynamics, Autumn, 22–35.

Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J. and Rasinski, K. (2000). The Psychology of Survey Response, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tourangeau, R. and Smith, T. W. (1996). Asking sensitive questions: the impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context, Public Opinion Quarterly, 60 (2), 275–304.

UNCTAD (2006). World Investment Report: FDI from Developing and Transitional Economies: Implications for Development, New York and Geneva: United Nations.

Walter, G. A. and Barney, J. B. (1990). Management objectives in mergers and acquisitions, Strategic Management Journal, 11, 79–86.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case Study Research: Design and Methods, London: Sage.

Zerbe, W. J. and Paulhus, D. L. (1987). Socially desirable responding in organizational behavior: a reconception, Journal of Management Review, 12, 250–264.