Perspective of UK firms

Mohammad F. Ahammad, Shlomo Y. Tarba, Keith W. Glaister, Ian P. L. Kwan, Riikka M. Sarala, and Luiz Montanheiro

Introduction

Cross-border mergers and acquisitions (CBM&As) have become the dominant means of internationalisation, accounting for approximately 60 pre cent of all foreign direct investment inflows (Hopkins, 1999). Consistent with this, cross-border acquisitions now represent over 25 per cent of all global M&A transactions, a considerable rise from the 15 per cent of ten years ago (Schoenberg and Seow, 2005). According to Thomson Reuters, firms invested almost $3,500 billion in M&As in 2014 – a significant increase since 2008 (Forbes, 2015). Cross-border M&A activity by UK firms was volatile between 2008 and 2013. During 2008 and 2009 the number of acquisitions made abroad by UK companies fell by 60 per cent, from 298 acquisitions reported during 2008 down to 118 transactions reported at the end of 2009. At the end of 2013, the number of outward acquisitions decreased by 59 per cent, falling from 112 acquisitions reported during 2012 to 50 acquisitions at the end of 2013 (ONS, 2014).

Yet, in parallel with this rise in activity, there has been increasing recognition of the poor performance of many cross-border M&As (Gomes et al., 2011). For example, Rostand (1994) reports that 45 per cent of such acquisitions fail to meet their initial strategic objectives, while Datta and Puia (1995) find that on average cross-border acquisitions destroy value for acquiring firm shareholders. A study by KPMG found that only 17 per cent of cross-border acquisitions created shareholder value, while 53 per cent destroyed it (The Economist, 1999). Moreover, cross-border M&As are widely perceived as higher risk compared to their domestic counterparts. Aw and Chatterjee’s (2004) data on two-year post-acquisition shareholder returns confirm this, reporting that cumulative abnormal returns for acquiring firms were significantly more negative for European cross-border targets than in the case of domestic UK targets. Other researchers remain pessimistic over the success potential of cross-border acquisitions (e.g. Moeller and Schlingemann, 2005). Furthermore, there is no corroborative evidence that M&A strategy has a significant positive impact on the financial performance of the acquiring company since the findings of the research studies are often inconsistent, mixed, and even contradictory (Gomes et al., 2013; Haleblian et al., 2009; Papadakis and Thanos, 2010; Weber et al., 2014).

An examination of CBM&As performance studies (see Eun et al., 1996; Danbolt, 2004) reveals that target firms are clear winners. This may justify the reasons for target firms to engage in cross-border deals. But as the empirical literature suggests the bidding firms in cross-border deals do not always win, it is difficult to conclude that the huge growth of cross-border M&A activity has been for financial benefit only. Therefore, it has become an empirical necessity to discover what motivates the bidding firms to acquire foreign targets.

This study examines the reasons why firms engage in cross-border acquisitions or international acquisitions (the two terms will be used interchangeably). Specifically, the objectives of this study are:

- To identify the relative importance of factors motivating the decision to acquire foreign target firms by UK acquiring firms.

- To provide a parsimonious set of factors influencing CBM&As for the sample.

- To test hypotheses on the way in which the relative importance of factors motivating CBM&As may vary with the sample characteristics.

The rest of the chapter is set out as follows. The next section reviews the literature relating to motives for CBM&As. The third section develops the hypothesis of the study. The findings and discussion are in the fourth section. A summary and conclusions are provided in the final section.

Literature review

Most of the prior literature describes M&As as ways predominantly to achieve additional market share or synergies (Walter and Barney, 1990; Schmitz and Sliwka, 2001). Such motives indicate that M&As are means to realise the strategies of the acquiring or merging parties. Discussing M&A motives from other perspectives adds additional dimensions to the picture: agency theory (Kesner et al., 1994), hubris (Weston and Weaver, 2001; Berkovitch and Narayanan, 1993; Roll, 1986; Seth et al., 2000) and empire building (Trautwein, 1990) indicate the existence of more than one motive for M&As. Hitt et al. (2001), Calipha et al. (2010) and Gomes et al. (2011) also suggest multiple motives for firms to complete CBM&As.

Several of the same motives are identified by various authors, while some of them overlap. The main motives discussed in the literature include the following.

Facilitate faster entry into foreign market

As compared to internally generated product developments and new business, acquisitions allow the firm to enter a new market more rapidly. It is argued that in general it is expensive, difficult and time-consuming to build up a global organisation and a competitive presence due to issues such as differences in culture, liability of foreignness, different business practices and institutional constraints. Cross-border M&As offer significant time saving in this respect. For example, cross-border M&As allow immediate access to a local network of suppliers, marketing channels, clients and other skills.

Martin et al. (1998) have suggested that CBM&As can be used to access new markets as well as expand the market for a firm’s current goods. Similar conclusions have been drawn by Datta and Puia (1995) who state that CBM&A activity provides the opportunity for instant access to a market with established sales volume. UNCTAD (2000) also indicates that cross-border mergers provide the fastest means for international expansion compared to greenfield investment or joint ventures.

Research on entry mode choice also suggests that acquisition is more appropriate for a faster entry into a new market compared to greenfield investment (Shimizu et al., 2004). If the investor has a short amount of time to penetrate the foreign market, the only available choice will be acquiring an existing firm. In fact, greenfield entries require a much slower and more moderated approach. Hennart and Park (1993) found that the timing of the investment influenced the mode of entry choice. Specifically, if the target market has a high growth rate, the choice of an acquisition allows the investor to penetrate it more quickly.

Uddin and Boateng (2011) examined the growth of CBM&As over recent decades and highlighted that prior studies referring to cross-border M&A activities as an entry mode of FDI have focused on industry and firm level-related factors. Therefore, Uddin and Boateng investigated the role of macroeconomic influences on CBM&A activities in the UK over the 1987–2006 period and found that GDP, exchange rate, interest rate and share price have all had significant impact on the level of outward UK CBM&As, thus contributing to our understanding of the effects of macroeconomic variables.

Increase market power

Market power exists when the firm can sell its products above the existing competitive market prices or when its manufacturing, distribution and service costs are lower than those of competitors. Market power is a product of the firm’s size, the degree of sustainability of its current competitive advantage, and its ability to make decisions today that will yield new competitive advantages tomorrow (Hitt et al., 2001).

Cross-border acquisitions are used to increase market power when the firm acquires: (a) a company competing in the same industry and often in the same segments of the primary industry; (b) a supplier or distributor; or (c) a business in a highly related industry (Hitt et al., 2001). If a company operates within a concentrated market where there are fewer competitors, merging via horizontal integration could provide the company with even more market power. Having more market power also means having the ability to impact and/or control prices. Through vertical acquisitions, firms seek to control additional parts of the value-added chain. Acquiring either a supplier or a distributor or an organisation that already controls more parts of the value chain than the acquiring firm can result in additional market power. Market power can also be gained when the firm acquires a company competing in an industry that is highly related.

Cui et al. (2014), using a sample of 154 Chinese firms, found that firms’ strategic assets seeking managerial intent to catch up with world-leading economies by acquiring strategic assets abroad has been influenced by their exposure to foreign competition, their governance structure and relevant financial and managerial capabilities. Nicholson and Salaber (2013), for their part, explored the value creation of cross-border acquisitions in emerging markets and its impact on shareholder wealth creation, and concluded that Chinese investors gain from the cross-border expansion of manufacturing companies, and that location also affects the performance of cross-border acquisitions, with acquisitions into developed countries generating higher returns for shareholders.

Access to and acquisition of new resources and technology

A number of studies have examined the motivation for cross-border M&As from the resource-based and organisational learning perspectives (Barkema and Vermeulen, 1998; Madhok, 1997; Vermeulen and Barkema, 2001). These studies suggest that cross-border M&As are motivated by an opportunity to acquire new capabilities and learn new knowledge. Today’s products rely on so many different critical technologies that most companies can no longer maintain cutting-edge sophistication in all of them (Ohmae, 1989).

Tapping external sources of know-how becomes imperative. Acquisition of an existing foreign business allows the acquirer to obtain resources such as patent-protected technology, superior managerial and marketing skills, and special government regulation that creates barriers to entry for other firms. Shimizu et al. (2004) endorse this by suggesting that firms may engage in M&As to exploit intangible assets. This line of reasoning is consistent with Caves (1990), who argues that acquisition of a foreign competitor enables the acquirer to bring under its control a more diverse stock of specific assets, which enables it to seize more opportunities.

Deng (2009), drawing on a multiple-case study of three leading Chinese firms – TCL, BOE and Lenovo – stressed the strategic assets resource-driven motivation behind Chinese cross-border M&A in order to retain their competitive advantages. In the same vein Rui and Yip (2008) utilised a strategic intent perspective (SIP) in order to analyse the foreign acquisitions pursued by Chinese firms, and suggested that acquiring firms from China strategically use cross-border acquisitions to obtain strategic capabilities that help them to to offset their competitive disadvantages and leverage their unique ownership advantages, while making use of institutional incentives and minimising institutional constraints. Extending this logic, Buckley et al. (2014) developed and tested a framework of the resource- and context-specificity of prior experience in acquisitions conducted by multinational companies from emerging countries (EMNCs) that acquire companies in developed countries. They found that acquisitions made by EMNCs often enhance the performance of target firms in the developed economies, and the role of EMNCs’ idiosyncratic resources (such as access to new markets and cheap production facilities) and investment experience in enhancing the performance of target firms differs across acquisition contexts. Specifically, they indicated that while certain types of resources and investment experience might be beneficial, due to facilitating resource redeployment and the exploitation of complementarities, some other types of experience may have a detrimental impact on the performance of the incumbent target companies.

Kohli and Mann (2012) assessed the acquiring company announcement gains, and determinants thereof, in both domestic and cross-border acquisitions pursued in India. Specifically, their sample consisted of 268 acquisitions comprising of 202 cross-border and 66 domestic deals. Interestingly, this study found that cross-border acquisitions have created significantly higher wealth gains than the domestic deals. Furthermore, Kohli and Mann concluded that cross-border acquisitions involving both an acquiring company and a target company in the technology intensive sector provide opportunities for the acquiring company to combine and judiciously utilise intangible resources of both companies on a broader scale across new geographies and as a result create superior wealth gains.

Zheng et al. (2016), drawing on multiple cases of cross-border mergers and acquisitions by Chinese multinational enterprises (CMNEs), investigate their search for strategic assets in developed economies. Their study reveals that CMNEs possess firm-specific assets that give them competitive advantages at home and seek complementary strategic assets in similar domains, but at a more advanced level. Moreover, the focal CMNEs utilised the partnering approach that facilitated the securing of the aforementioned strategic assets through no or limited integration, namely granting autonomy to the target firm’s management team and retaining talents.

Park and Ghauri (2011) investigated whether foreign acquiring firms contribute towards enhancing technological capabilities of local firms in foreign markets, and found that mere exposure to favourable learning environments is insufficient to develop an effective absorptive capacity, and that intensity of effort is a critical component functioning as a facilitator towards the extent of learning. In addition, their findings indicate that existing knowledge can be improved when the combining entities share similar business backgrounds, and finally that collaborative support from knowledge transferers serves as a significant catalyst leveraging a specific learning capability.

Almor et al. (2014), based on an empirical study of Israeli knowledge-intensive companies between 2000 and 2009, found that maturing, technology-based, born-global companies can increase their chances of survival by acquiring other firms. Although such acquisitions do not increase profits, they allow born-global firms to continue increasing their sales and to expand and upgrade their product lines, which in turn increases their chances of remaining independent. It is worth highlighting that although the majority of aforementioned born-global companies can continue operations if they survive the first decade, they are not highly successful in terms of growth or enhancing shareholder wealth. Therefore, Almor et al. recommend that maturing, technology-based, born-global companies should be more aggressive in pursuing their M&A strategies if they wish to be successful.

Diversification

Diversification is a well-documented strategy for firm expansion and has been suggested as one of the dominant reasons for cross-border M&As. Sudarsanam (1995) notes that diversification is generally defined as enabling the company to sell new products in new markets. This implies that the target company in an acquisition operates in a business that is unrelated to that of the buyer firm.

It is argued that international acquisitions not only provide access to important resources but also allow firms an opportunity to reduce the costs and risks of entering into new foreign markets. Seth (1990) reported that geographical market diversification is a source of value in cross-border acquisitions. This is because the sources of value, such as those associated with exchange rate differences, market power conferred by international scope and ability to arbitrage tax regimes, are unique to international mergers. Moreover, as economic activities in different countries are less than perfectly correlated, portfolio diversification across boundaries should reduce earnings volatility and improve investors’ risk–return opportunities.

Improved management

Sirower (1997) notes that managers try to maximise shareholder value either by replacing inefficient management in the target firm or by seeking synergies through the combination of the two firms. Gaughan (1991) claims that some M&As are motivated by a belief that the acquiring firm’s management can better manage the target’s resources. The acquirer may feel that its management skills are such that the value of the target would rise under its control.

The improved management argument may have particular validity in the case of large companies making offers for smaller companies. The smaller companies, often led by entrepreneurs, may offer a unique product or service that has sold well and facilitated the rapid growth of the target. As the target grows, however, it requires a very different set of management skills than were necessary when it was a smaller business. The growing enterprise may find that it needs to oversee a much larger distribution network and may have to adopt a very different marketing philosophy. Many of the decisions that a larger firm has to make require a vastly different set of managerial skills than those that resulted in the dramatic growth of the smaller company. The lack of managerial expertise may be a stumbling block in the growing company and may limit its ability to compete in the broader market place. These managerial resources are an asset which the larger firm can offer the target (Gaughan, 1991).

Synergy

Bradley et al. (1988) and Trautwein (1990) argue that firms engage in M&As in order to achieve synergies. Synergies stem from combining operations and activities such as marketing, research and development, procurement and other cost components, which were hitherto performed by the separate firms. It is argued that by combining operations and activities, M&As can increase a firm’s capacity and opportunity to reduce costs through economies of large-scale production, pooling resources to produce a superior product and generate long-run profitability. Interestingly, in the particular context of declining industries, Anand and Singh (1997) found that assets in the aforementioned industries are redeployed more effectively through market mechanisms than within the firm through the acquisition of complementary assets, and consolidation-oriented acquisitions outperform diversification-oriented acquisitions in the decline phase of their industries in terms of both ex ante (stock-market- based) and ex post (operating) performance measures.

In the specific context of cross-border M&As, the literature on corporate foreign investment describes various means by which cross-border M&As may create value. Acquiring an existing foreign facility provides a means for the rapid exploitation of the potential for synergistic gain compared with de novo entry. Porter (1987) suggests that one source of operating synergy comes from the potential to transfer valuable intangible assets, such as skills, between the combining firms. If a firm has know-how that can be used in markets where the sale or lease of such knowledge is inherently “inefficient,” then the firm will tend to exploit it through its own organisation. Although different versions are developed by various scholars (e.g. Williamson, 1975; Rugman, 1982), all assume that transacting in the international market entails substantial costs which will reduce the value of proprietary information. Faced with this cost, a firm will be likely to internalise the transaction and use the proprietary information within its expanded organisation. Gains may also be realised form “reverse internalisation”: firms acquire skills and resources from cross-border M&As that are expected to be valuable in their home markets. A related source of synergistic gains in cross-border acquisitions focuses on market development opportunities. In order to utilise their “excess” resources for long-run profitability efficiently, firms will invest abroad when growth at home is limited or restricted and in the presence of trade barriers which restrict exports. In addition, devising and implementing the tailor-made post-acquisition integration approach was found to be critical for potential synergy realisation in cross-border M&As (Almor et al., 2009; Weber and Tarba, 2011; Weber, Tarba and Reichel, 2009, 2011; Weber, Tarba and Rozen Bachar, 2011, 2012).

Managerial motive

The managerialism hypothesis suggests that managers embark on M&As in order to maximise their own utility at the expense of their firm’s shareholders (Seth et al., 2000). Managers can have private or personal reasons for their behaviour and make investments which from an economic point of view may seem irrational, but for the individual can be of high value. The empire-building theory maintains that management want firm growth for personal reasons, and acquisitions provide this growth. An important aspect of this is the wage explanation, whereby the salary paid to managers is a function of the size of the company (Mueller, 1969). Motives like power and prestige are also stressed (Ravenscraft and Scherer, 1987): for instance, managers in large companies have an easier route to senior positions in committees and on boards of directors (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978).

While managerialism has been proposed as a motive for domestic M&As, it may also be relevant for cross-border M&As if managers have the incentive and the discretion to engage in M&As aimed at empire building (Seth et al., 2000). In an integrated capital market, firm-level diversification activities to reduce risk are generally considered non-value maximising as individual shareholders may duplicate the benefit from such activities at lower cost. However, managers may still seek to stabilise the firm’s earnings stream by acquiring foreign (rather than domestic) firms, given low correlations between earnings in different countries. Foreign acquisitions may be more satisfactory vehicles for risk reduction than domestic acquisitions; and, in the absence of strong governance mechanisms to control managerial discretion, managers may overpay for these acquisitions.

Hypotheses

The literature gives little indication of what to expect in terms of the relative importance of a set of motivating factors for international acquisition. It may be conjectured, however, that the relative importance of the motives would vary with the underlying key characteristics of the sample. For the purposes of this study, these characteristics are identified as regional origin of the target firm, sector of operation and pre-acquisition performance of the target firm.

Regional origin of the target firm

There is no prior literature that provides an extensive examination of the strategic motives of international acquisition according to the choice of nationality of the foreign firm. Foreign firm choice will presumably hinge on the tasks to be accomplished by the acquisition and the particular characteristics required from a target. To the extent that UK firms believe that targets in particular foreign nations can provide certain requirements of the acquisition – for example, access to specific markets or types of technology – these targets will be chosen in preference to potential targets in different places when the acquisition is made. The fundamental motive for the acquisition may then be expected to vary according to the nationality of the foreign target. This leads to Hypothesis 1:

The relative importance of strategic motives for CBM&As will vary with the regional origin of the target firm.

Industry of operation

The motives for carrying out M&As from the acquiring firm’s perspective tend to be different across various industries (see Walter and Barney, 1990; Brouthers et al., 1998). Kreitl and Oberndorfer (2004) argued that motives vary across industry and time, and found that more emphasis was placed on certain motives in engineering consulting firms than in other manufacturing sectors. Several of the strategic motives appear to lend themselves more readily to acquisitions in the manufacturing sector – for example, product rationalisation and economies of scale, and transfer of complementary technology/exchange of patents – than they do to acquisitions in the service sector, where risk sharing, shaping competition and the use of acquisition to facilitate international expansion appear to be more relevant. To the extent that this is the case, it would be expected that strategic motivation would vary with the industry sector of the acquisition, which is reflected in Hypothesis 2:

The relative importance of strategic motives for CBM&As will vary with the industry of the target firm.

Pre-acquisition performance of the target firm

An acquiring company can correct an efficiency problem in the target firm, which will increase the target’s value and create synergistic gains. To detect a situation in which the target’s inefficiencies can be improved, the target’s performance prior to the acquisition is examined for inefficient management. According to Servaes (1991) the largest synergistic gains are possible when an efficient firm acquires an inefficient firm. Therefore, an acquirer may be motivated to acquire a poorly performing foreign firm with a view to turning it around, for example by replacing inefficient management. On the other hand, an acquirer may be motivated to acquire a profitable foreign firm in order to realise synergic benefits, such as economies of scale or cost reduction. The fundamental motive for the international acquisition may then be expected to vary according to the pre-acquisition performance of the target firm, which leads to Hypothesis 3:

The relative importance of the strategic motives for CBM&As will vary according to the pre-acquisition performance of the target firm.

Methodology

The data were gathered via a cross-sectional survey using a questionnaire on a sample of UK firms acquiring North American and European firms during the five-year period from 2000 to 2004, inclusive. The development of the questionnaire was guided by a review of previous mergers and acquisitions research (e.g. Seth et al., 2000; Walter and Barney, 1990).

A list of potential sample firms was generated from the Mergers and Acquisitions Database of the Thomson One Banker. This database provides comprehensive secondary information about mergers and acquisitions, including cross-border deals. The sample includes those deals in which the acquirer bought a 100 per cent equity stake in the acquired company. Based on the results of the website search and telephone conversations, a list of key informants and potential survey participants was assembled. This procedure produced a sample of 798 firms. After an initial attempt to contact executives all 798 UK firms, 207 were deleted because they had a policy of not participating in survey research, or the executives indicated that they did not have the time or the capacity to take part in the study. Accordingly, the final sampling frame of international acquirers was 591.

In April 2007, 591 questionnaires with covering letters and return envelopes were posted to the executives of the potential survey participants. To provide motivation for accurate responses, the respondents were guaranteed anonymity and promised a summary report of the research findings, if requested. After three reminders (by means of telephone, email or follow-up letter), 69 questionnaires were returned, of which 65 were fully completed and usable; effectively a response rate of 11 per cent. Given the well-documented difficulties of obtaining questionnaire responses from executives (Harzing, 1997) and decreasing response rates from executives (Cycyota and Harrison, 2002), a response rate of 11 per cent can be considered satisfactory. It is similar to that reported in other academic studies of executives. For instance, Graham and Harvey (2001) achieved a response rate of nearly 9 per cent from CFOs, and Mukherjee et al. (2004) obtained an 11.8 per cent response rate in a survey mailed to 636 CFOs who were involved in acquisitions management.

All of the respondents had been directly involved in managing the CBA process. An examination of their job titles revealed that 12 chief executive officers, 16 finance directors or chief financial officers, 23 business development directors, 8 managing directors and 6 executive directors. The sample represents acquisition activity in two continents: North America and Europe. In North America, the acquired firms are from the USA and Canada (21 and 9, respectively). Europe is represented by 35 acquisitions.

In order to assess potential retrospective bias, responses concerning acquisitions made in 2004 were compared to acquisitions made in 2000. A number of variables were included in this test, such as prior performance, acquisition experience and relative size. The t-tests for mean differences were calculated and evinced no statistically significant differences. These findings suggest that retrospective bias does not influence the study.

The possibility of non-response bias was checked by means of two procedures. The first of these was a test to compare early and late respondents along a number of key description variables. Differences between the two groups were not statistically significant, suggesting that non-response bias was not a major problem. Second, respondent and non-respondent firms were compared with respect to their relative size and primary sector of operation. The t-tests of mean difference were insignificant, confirming no systematic bias between the responding firms and the non-responding firms.

Findings and discussion

Relative importance of the strategic motives

The rank order of the twenty strategic motives for international acquisition by UK companies, based on the mean measure of importance, is shown in Table 3.1. The median measure is exceeded by nine acquisition motives, of which “to enable presence in new market” (3.55), “to enable faster entry to market” (3.54), “to facilitate international expansion” (3.52), “gain new capabilities” (3.42), “gain strategic assets” (3.26) and “increase market power” (3.09) constitute the six with the highest degrees of importance. It is clear from the table that the managers perceived their motives for international expansion to be strongly influenced by growth-oriented factors. The highest-ranked strategic motives are concerned with relative competitive positions in new markets.

Table 3.1 Relative importance of strategic motives for international acquisition by UK companies

| Rank |

Motivation |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

|

| 1 |

To enable presence in new markets |

3.55 |

1.392 |

| 2 |

To enable faster entry to market |

3.54 |

1.668 |

| 3 |

To facilitate international expansion |

3.52 |

1.511 |

| 4 |

Gain new capabilities |

3.42 |

1.223 |

| 5 |

Gain strategic assets |

3.26 |

1.350 |

| 6= |

Increase market power |

3.09 |

1.444 |

| 6= |

Gain efficiency through synergies |

3.09 |

1.400 |

| 8= |

Acquire complementary resources |

3.08 |

1.315 |

| 8= |

Increase market share |

3.08 |

1.461 |

| 10 |

Enable product diversification |

2.86 |

1.488 |

| 11 |

Obtain non-manufacturing scale economies |

2.31 |

1.198 |

| 12 |

Obtain economies of large-scale production |

2.17 |

1.269 |

| 13 |

To reduce risk of the business |

1.95 |

1.067 |

| 14 |

Cost reduction |

1.92 |

1.136 |

| 15 |

Elimination or reduction of competition |

1.66 |

1.020 |

| 16 |

Enable the overcoming of regulatory restrictions |

1.63 |

1.098 |

| 17 |

Turn around failing acquired firm |

1.62 |

1.041 |

| 18= |

Redeploy assets to the acquisition |

1.54 |

0.772 |

| 18= |

Replace inefficient management of acquired firm |

1.54 |

0.867 |

| 20 |

Tax reasons (savings) |

1.32 |

0.773 |

Considering the motives in terms of their underlying theoretical explanations, it is apparent that, for this sample, the main strategic motives are underpinned by the theories of strategic positioning and the resource-based view (RBV). The first three ranked motives are concerned with improving the firm’s competitive position through the use of acquisitions that may be characterised as most importantly allowing the UK firms to enter new foreign markets at speed and/or consolidating existing market positions.

The leading set of motives also lends support to the RBV of acquisitions, particularly when it is recognised that the acquisition takes place because the acquirer lacks the necessary capabilities or assets required for remaining competitive in the foreign market. Where one firm wishes to acquire a capability that it does not have but is possessed by a target firm (such as tangible resources – for example, capital, machinery and land – and intangible resources – for example, capabilities, organisational culture and know-how), then an acquisition may facilitate obtaining these capabilities.

The most important acquisition motive for the surveyed firms was to enable presence in new markets. Thus, expanding the acquiring firm’s market portfolio to reach new markets was obviously a top priority for the surveyed firms. The importance of presence in new markets supports Ingham et al.’s (1992) study of British firms where the penetration of new geographic markets ranked second.

Enabling faster entry to market was highly ranked. International mergers and acquisitions are the fastest means for firms to expand their production and markets internationally (Chen and Findlay, 2003). When time is crucial, acquiring an existing firm in a new market with an established distribution system is far preferable to developing a new local distribution and marketing network. For a latecomer to a market or a new field of technology, international M&As can provide a way to catch up rapidly. With the acceleration of globalisation, and enhanced competition, there are increasing pressures for UK firms to respond quickly to opportunities in the fast-changing global economic environment. Thus, for UK companies seeking to compete in nations outside their home base, acquiring a firm is a much faster way to reach this objective when compared with the time required to establish a new facility and new relationships with stakeholders in a different country.

The third-ranked motive was to facilitate international expansion. The desire to expand from the national domestic market is not surprising as the search for new markets and market power is a constant concern for firms in an increasingly competitive environment. In conditions of rapid change and high innovation costs, expansion through external means has become an absolute necessity (Child et al., 2001). A company can expand through greenfield or through mergers and acquisitions. When expanding abroad via direct investment, firms face greater risks than local firms due to their lack of familiarity with the host market. Thus, the firm often prefers the lower risk of acquisition once a foreign firm is thought suitable for the purpose of international expansion (Caves, 1996).

Another important motive for cross-border M&As for UK acquiring firms is to acquire strategic assets and capabilities, which encompass technology, R&D and management know-how. This finding is consistent with Granstrand and Sjolander (1990), who suggest that firms with low skills may enter foreign markets via M&As that allow the firms to obtain new technological resources and other strategic assets. Caves (1990) endorses this by suggesting that foreign acquisitions may be motivated by the quest to bring a more diverse collection of specific assets under the acquirer’s control and to enable more opportunities to be seized. This explanation is also in line with the views of Hill et al. (1990), who point out that foreign acquisition by MNCs may be motivated by strategic objectives. Bresman et al. (1999) also suggest that cross-border M&A is an effective way to expand the knowledge base of a firm.

The ranking of the motives revealed that British CBM&As are not driven by diversification motives (rank 10 and 13) or by the desire to reduce costs (rank 11 and 14). Firms usually pursue diversification in order reduce earnings volatility and improve investors’ risk–return opportunities. However, one of the disadvantages of acquisitions that are motivated by diversification is the tendency to stretch the acquiring company’s management (Gaughan, 1991). The ability to manage a firm successfully in one industry does not necessarily translate to other businesses. Moreover, the acquiring company is providing a service (i.e. diversification) to stockholders that they can accomplish better themselves (Levy and Sarnat, 1970). For instance, a steel company that has a typical pattern of cyclical sales may consider acquiring a pharmaceutical company that exhibits a recession-resistant sales pattern. Financial theory states that the managers of the steel company are doing their stockholders a disservice through acquisition of the pharmaceutical company. If stockholders in the steel company wanted to be stockholders in a pharmaceutical firm, they could easily adjust their portfolios to add shares of such a firm. Stockholders can accomplish such a transaction in a far less costly manner than through a corporate acquisition.

The lowest-ranked international acquisition motives (rank 15 to 20) include “enable overcoming of regulatory restrictions” (1.63), “turn around failing acquired firm” (1.62), “redeploy assets to the acquisition” (1.54), “replace inefficient management” (1.54) and “tax reasons” (1.32). Overcoming regulatory restrictions appears not to be an important motivation for British international acquisitions. This is not surprising as most of the regulatory restrictions were removed before 2000 (all of the acquisitions in the sample were completed in the 2000 to 2004 period). Regulatory reform and deregulation in the 1990s in industries such as telecommunications (the WTO agreement on basic telecommunications services came into effect in 1998), electricity and finance played a significant role in the remarkable increases in M&As in both developed and developing countries (UNCTAD, 2000). The promotion of regional integration in the 1990s, as in Europe and North America, provided opportunities for expansion through cross-border M&As. Thus, regulatory restrictions are now less important factors for making an acquisition overseas. “Tax reasons (savings)” is ranked lowest, indicating that British CBM&As are rarely driven by this motive. Weston et al. (2001) suggest that the synergies resulting from tax savings are insufficient to motivate an acquisition, which seems to be supported by this study.

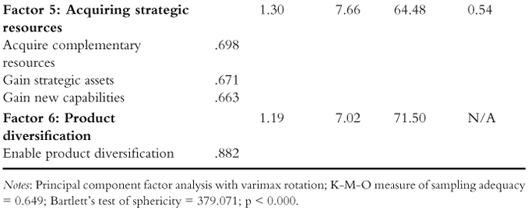

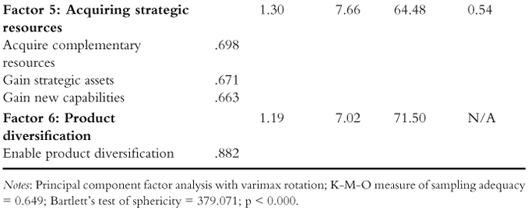

Factor analysis of strategic motives

Due to potential conceptual and statistical overlap, an attempt was made to identify a parsimonious set of variables to determine the underlying dimensions governing the full set of twenty strategic motives. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using varimax rotation was used to extract the underlying factors. The EFA initially produced seven factors for the twenty strategic motives. A content analysis (Cavusgil and Zou, 1994; Deshpande, 1982) was conducted to remove items that had inconsistent substantive meanings with the factor or that had low factor loadings from further analysis. This purification process resulted in the elimination of three motives: “enable the overcoming of regulatory restrictions,” “tax reasons (savings)” and “to reduce risk of the business.” The remaining seventeen motives were again factor analysed and produced six non-overlapping factors, as shown in Table 3.2. Six factors explained a total of 71.50 per cent of the observed variance (with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.54 to 078). The remainder of this section discusses the interpretation of each of these factors.

Table 3.2 Factor analysis of strategic motives for CBM&As

- Factor 1: Synergies. The first factor had high positive loadings on the following four strategic motives: obtain economies of large-scale production; obtain non-manufacturing scale economies; gain efficiency through synergies; and cost reduction. This first factor was, therefore, interpreted to be a motive related to synergies.

- Factor 2: Market development. This factor had high positive loading on three strategic motives: to facilitate international expansion; to enable presence in new markets; and to enable faster entry to market. It was interpreted that this second factor reflects market development.

- Factor 3: Target improvement. This factor had high positive loading on three strategic motives: turn around failing acquired firm; replace inefficient management of acquired firm; and redeploy assets to the acquisition. This factor was interpreted as a motive to improve the target.

- Factor 4: Market power. The fourth factor had high positive loading on three strategic motives: increase market power; increase market share; and elimination or reduction of competition. Therefore, this factor was interpreted as a motive related to market power.

- Factor 5: Acquiring strategic resources. This factor had high factor loading on three strategic motives: acquiring complementary resources; gain strategic assets; and gain new capabilities. This factor was interpreted as a motive to acquire strategic resources.

- Factor 6: Product diversification. This factor had high factor loading on one strategic motive: enable product diversification. This factor was interpreted as a motive for product diversification.

Strategic motivation and sample characteristics

To investigate the underlying nature and pattern of the strategic motivation for this sample of international acquisitions further, the analysis was developed by considering the strategic motives in terms of the characteristics of the sample. For each of the relevant characteristics of the sample under consideration, Tables 3.3 to 3.5 report the means and standard deviations of the five factors and the individual strategic motives comprising each factor, the rank order of the individual strategic motives, and the appropriate test statistic for comparing differences in mean scores.

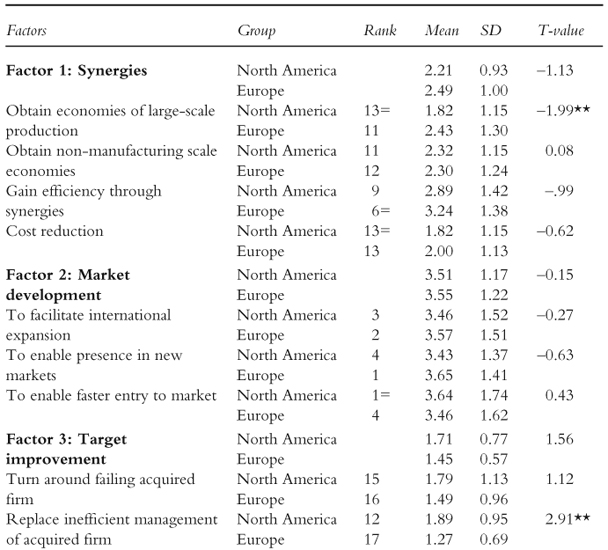

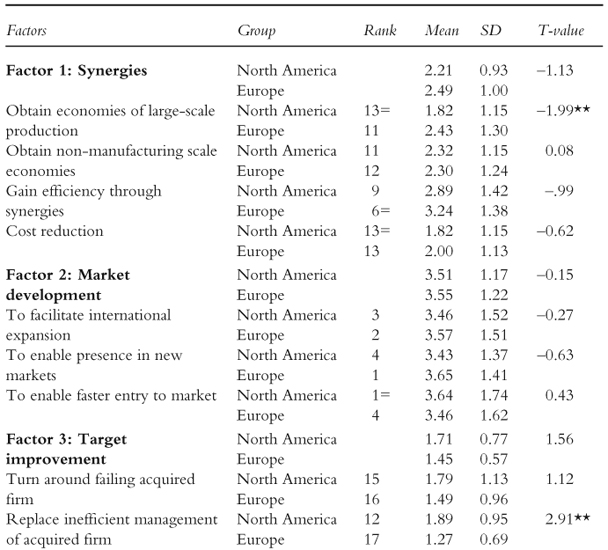

Strategic motives and origin of the target firm

The rank order of strategic motivation according to the geographical region of the acquisition, North America or Europe, is shown in Table 3.3. Some of the motives have a similar rank; however, there are several differences in rank order according to the location of the acquisition. The joint highest-ranked motive for North American acquisitions is to gain new capabilities, while for European acquisitions this motive is ranked only sixth. UK firms appear to believe that North American firms provide access to specific capabilities more readily than do European firms. Acquisition of new capabilities appears to be an essential step, because today’s products rely on so many different critical technologies that most companies can no longer maintain cutting-edge sophistication in all of them (Ohmae, 1989). In this respect it appears that North American firms have developed these capabilities more than European firms.

Table 3.3 Strategic motives for international acquisitions: origin of the target firm

The highest-ranked motive for European acquisitions is to enable presence in new markets, whereas for North American acquisitions this motive is ranked only fourth. It appears that it is more of a priority for UK firms to gain a presence in Europe than in North America. The desire to access the European market tends to support the survey findings of Jansson et al. (1994), in which “nearness and potential of the single market” was identified as the main reason for cross-border M&As in Europe by UK manufacturing firms.

Similar variations exist in the case of other motives, such as increase market share, enable product diversification, and replace inefficient management of acquired firm. For acquisitions in Europe, the motive to increase market share is ranked fifth; in contrast, the same motive is ranked tenth for North American acquisitions. It appears that for UK firms it is relatively more important to increase market share in the European market than in North America. This finding supports a survey reported by KPMG Management Consulting (1998), where increasing market share was identified as one of the most important motives for M&As in Europe by UK firms.

For North American acquisition, the motive to enable product diversification is ranked fifth, whereas this motive is ranked tenth for European acquisition. It appears that it is more of a priority for UK firms to enable product diversification in North America than in Europe. To remain competitive in the North American market, UK firms may have acquired firms that enable product diversification.

The motive to replace inefficient management of the acquired firm is ranked twelveth for North American acquisitions and seventeenth for European acquisitions. It appears that for UK firms it is relatively more important to replace inefficient management in North American acquired firms than in European acquired firms. The management of UK firms may believe that they can better manage the North American firms’ resources.

Despite the variations in ranking, Table 3.3 indicates a lack of support for Hypothesis 1, in that the relative importance of the strategic motives does not vary significantly between the origins of the target firm. None of the factors has mean scores that are statistically different. With regard to individual motives, only the relative importance of two – obtain economies of large-scale production (p < 0.05) and replace inefficient management of acquired firm (p < 0.05) – are found to vary significantly between region of target firm. The mean score for the obtain economies of large-scale production motive is higher for acquisitions in Europe than those in North America. In the case of replace inefficient management of the acquired firm, the mean score is higher for North American than European Union acquisitions.

In general, then, similar motives are driving CBM&As in the EU and North America, with little significant variation in terms of the relative importance of the motives.

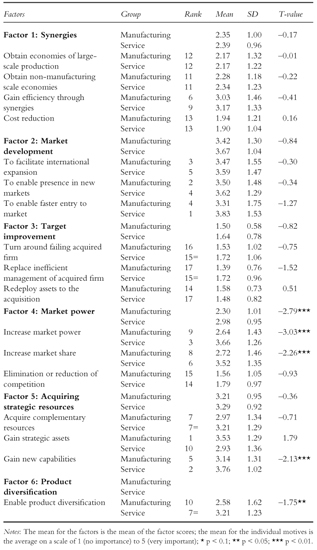

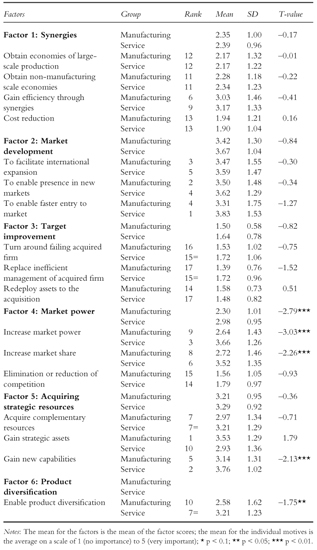

Strategic motives and sector of acquisition

To facilitate the statistical testing of the strategic motives, the industry of the acquisition was categorised in the conventional way by distinguishing between manufacturing and service sectors. The strategic motivation for international acquisitions by sector of operation is shown in Table 3.4.

The rank order of the strategic motives has a degree of similarity for the two sectors; however, there are some differences. For instance, the highest-ranked motive for acquisitions in the manufacturing sector is to gain strategic assets, while this motive is ranked only tenth in the service sector. It appears that it is more of a priority for UK firms to gain strategic assets in the manufacturing sector than in service sector. This suggests that UK firms lack the necessary strategic assets to

Table 3.4 Strategic motives for international acquisitions: sector of acquisition

operate and compete effectively in the foreign manufacturing sector. Thus, acquisition allows UK firms to obtain necessary and/or new technological resources and other strategic assets in order to seize opportunities in foreign markets (Caves, 1990).

The highest-ranked motive in the service sector is to enable faster entry into the market, while this motive is ranked only fourth in the manufacturing sector. It appears that it is more of a priority for UK firms to enable faster entry into the service sector than in the manufacturing sector. The importance of faster entry into the service sector supports Kang and Johansson’s (2000) study, where the growth of cross-border M&As in the service sector – that is, telecommunications, media and financial services – was seen in terms of the efforts of firms to capture new markets quickly and to offer more integrated global service.

The increase market power motive is ranked third for acquisitions in the service sector, whereas it is ranked ninth in the manufacturing sector. It appears that it is relatively more important for UK firms to increase market power in the service sector than in the manufacturing sector. If industry competition is higher in the service sector than in the manufacturing sector, a UK firm may choose to acquire an existing company in the service sector in order to increase industry concentration.

There is moderate support for Hypothesis 2, in that two of the six factors have mean scores that are significantly different – market power (p < 0.01) and product diversification (p <. 05) – with both mean higher in the service sector. Two of the three individual motives constituting the market power factor – increase market power (p < 0.01) and increase market share (p < 0.01) – show means that are significantly higher for international acquisition in the service sector compared to those in the manufacturing sector. The market power factor and the individual motives to increase market power, to increase market share and to eliminate or reduce competition may be viewed as a set of largely defensive motives designed to consolidate and protect the UK firms’ positions in foreign markets. Given that this set of motives is relatively more important for international acquisitions in the service sector than it is for motives in the manufacturing sector, it may be argued that international acquisitions in the service sector are more of a pro-reactive response to competitive pressure than is the case for international acquisitions in the manufacturing sector.

The finding that market power as a strategic motive is relatively more important for international acquisitions in the service sector than those in the manufacturing sector is consistent with McCann (1996) and Kreitl and Oberndorfer (2004). McCann found that the M&A motive of increasing the firm’s market share is very highly ranked in service sectors such as transportation and travel, financial services, professional service sectors and so on. Kreitl and Oberndorfer found market share was the third-highest-ranked motive in the consulting service sector. They argued that market share provides a consulting firm with name recognition and reputation for its expertise, a factor which reduces cost in marketing and sales.

The individual motive constituting the product diversification factor – enable product diversification (p < 0.05) – shows a mean significantly higher for international acquisition in the service sector compared to that in manufacturing sector. It appears that it is more of a priority for UK firms to enable product diversification in the service sector than in the manufacturing sector.

On the whole, there is moderate support for Hypothesis 2, indicating that motives for international acquisitions do vary according to the sector of acquisition, at least to some extent.

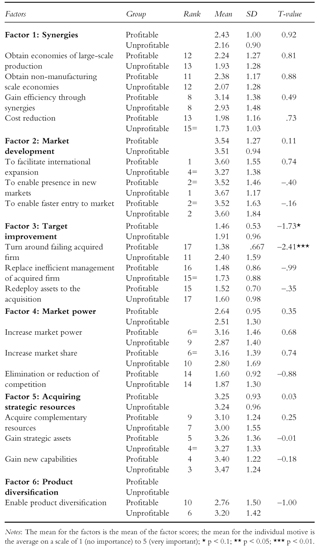

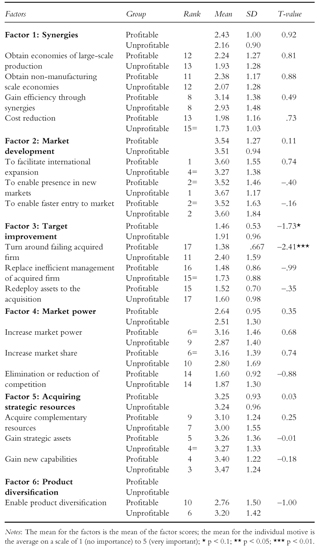

Strategic motives and pre-acquisition performance of foreign firms

The rank order of strategic motivation according to the pre-acquisition performance of target firms is shown in Table 3.5. Some of the motives have similar ranks between profitable target firm and not-profitable firm, although there are some differences in rank order according to the pre-acquisition performance of the target firm. The highest-ranked motive when acquiring a profitable firm is to facilitate international expansion, whereas this motive is ranked fourth in the case of an unprofitable firm. It appears that it is more of a priority for UK firms to acquire a profitable firm than to acquire an unprofitable firm for facilitating international expansion. This is not surprising, as acquiring a profitable firm can facilitate international expansion more easily than acquiring an unprofitable firm.

Similar variation exists in the rank order of other motives. The motive to increase market share is ranked sixth for acquiring a profitable firm. The same motive is ranked tenth for acquiring an unprofitable firm. It appears that it is relatively more important for UK firms to acquire a profitable firm than to acquire an unprofitable firm in order to increase market share. The market share of a profitable firm is expected to be higher than that of an unprofitable firm. Thus, acquiring a profitable firm can result in a relatively higher market share for the acquiring firm.

Despite some variation in ranking, Table 3.5 indicates weak support for Hypothesis 3, in that only one of the six factors – target improvement (p < 0.1) – has mean scores that are significantly different, with the mean unsurprisingly higher for acquisition of unprofitable firms. One of the three individual motives constituting the target improvement factor – turn around failing acquired firm (p < 0.01) – shows a mean significantly higher for international acquisitions of unprofitable firms compared with those of profitable firms. This is to be expected as an acquirer may be motivated to acquire a poorly performing foreign firm with a view to turning it around, for example by replacing inefficient management. This result is consistent with the improved management hypothesis, which holds that poorly managed firms have a greater likelihood of becoming takeover targets (Manne, 1965). Gaughan (1991) argues that some takeovers are motivated by a belief that the acquiring firm’s management can better manage the target’s resources. Thus, a UK acquirer may feel that its management skills are such that the value of the target will rise under its control.

Brealey and Myers (2003) suggest that cash is not the only asset that can be wasted by poor management. Firms with unexploited opportunities to cut costs and increase sales and earnings are natural candidates for acquisition by other firms with better managements. The authors also suggest that sometimes an acquisition is the

Table 3.5 Strategic motives for international acquisitions: performance of target firms

only simple and practical way to improve management, because the incumbent managers are naturally reluctant to fire or demote themselves, and stockholders of large public firms do not usually have much direct influence on how the firm is run or who runs it.

Overall, there is weak support for Hypothesis 3, suggesting that most of the motives for international acquisitions vary little according to pre-acquisition performance of the target firm. However, there are significant differences with respect to the motive of target improvement, as expected.

Summary and conclusions

This study identifies the main strategic motives driving CBM&As by UK firms. International acquisitions are seen primarily as a means to enable presence in new markets, to enable faster entry to market, to facilitate international expansion, to gain new capabilities, to gain strategic assets, to increase market power, to gain efficiency through synergies, to acquire complementary resources and to increase market share. In terms of underlying theoretical explanations, the main strategic motives are underpinned by the theories of strategic positioning and the resource-based view of the firm. The first three ranked motives are concerned with improving the firm’s competitive position through the use of acquisition that may be characterised as most importantly allowing the UK firms to enter new foreign markets at speed and/or consolidating existing market positions. The leading set of motives also lends support to the RBV of acquisition, particularly when it is recognised that the acquisition takes place because the acquirer lacks the necessary capabilities or assets required to remain competitive in the foreign market. Where one firm wishes to acquire a capability that it does not have but is possessed by a target firm, the acquisition may facilitate obtaining these capabilities.

The study also finds that “enable overcoming of regulatory restrictions” and “tax reasons (savings)” appear to be relatively unimportant motives for international acquisitions by UK firms. This is not surprising as most of the regulatory restrictions were removed before 2000 (the acquisitions were completed in the 2000 to 2004 period). Regulatory reform and deregulation in the 1990s in industries such as telecommunications, electricity and finance played a significant role in the remarkable increases in M&As in both developed and developing countries (UNCTAD, 2000). Thus, the regulatory restrictions are now less important factors to be considered for making an acquisition overseas.

The study found little support for Hypothesis 1, indicating that the relative importance of the strategic motives does not vary significantly between the regional origin of the target firm. However, the rank order of the strategic motives suggests that there is some variation between the motives for acquisition in North America and Europe.

The findings indicate that the relative importance of the strategic motives varies to a moderate extent with the sector of acquisition activity, providing some support for Hypothesis 2. This is further supported in that there is some variation in ranking between the motives in the manufacturing sector and the motives in the service sector.

There is limited support for Hypothesis 3, in that there is little variance in the relative importance of the strategic motives with pre-acquisition performance of the target firm. However, in the key motive of target improvement there is a significant difference in means, with a significantly higher mean for acquisition of unprofitable firms. Also, the rank order of the strategic motives indicates that there are some variations in strategic motives between the acquisition of profitable firms and the acquisition of unprofitable firms.

In general, there is little variation in the relative importance of the motivating factors across the characteristics of the sample. Where there is variation, while this is sometimes readily explainable, it is not always obvious. Further investigation of the relative importance of the strategic motives between industries would help in providing a deeper understanding of the way in which strategic motives vary across these characteristics. Moreover, this study investigated the strategic motives for international acquisition by UK firms in the developed countries of North America and Europe. Future study could investigate the relative importance of the strategic motives in the context of developed and developing country acquisitions.

References

Almor, T., Tarba, S. Y. and Benjamini, H. 2009. Unmasking integration challenges: The case of Biogal’s acquisition by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries. International Studies of Management and Organization, Vol. 39 (3): 33–53.

Almor, T., Tarba, S.Y. and Margalit, A. 2014. Maturing, technology-based, born global companies: Surviving through mergers and acquisitions. Management International Review, Vol. 54 (4): 421–444.

Anand, J., and Singh, H. 1997. Asset redeployment, acquisitions, and corporate strategy in declining industries. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 18 (S1): 99–118.

Armitstead, L. 2006. British firms go on £62bn global spending spree. Business Section, Sunday Times, 1 January, p. 3.

Aw, M. and Chatterjee, R. 2004. The performance of UK firms acquiring large cross-border and domestic takeover targets. Applied Financial Economics, Vol. 14: 337–349.

Barkema, H. G. and Vermeulen, F. 1998. International expansion through start-up or acquisition: A learning perspective. Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 41 (1): 7–27.

Berkovitch, E., and Narayanan, M. P. 1993. Motives for takeovers: An empirical investigation. Journal of Financial and Quantative Analysis, Vol. 28 (3): 347–362.

Bradley, M., Desai, A. and Kim E. H. 1988. Synergistic gains from corporate acquisitions and their division between the stockholders of target and acquiring firms. Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 21(1): 3–40.

Brealey, R. A. and Myers, S. C. 2003. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bresman, H., Birkinshaw, J. and Nobel, R. 1999. Knowledge transfer in international acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 3: 439–462.

Brouthers, K. D., van Hastenburg, P. and Van den Ven, J. 1998. If most mergers fail why are they so popular? Long Range Planning, Vol. 31 (3): 347–353.

Buckley, P. J., Elia, S. and Kafouros, M. 2014. Acquisitions by emerging market multinationals: Implications for firm performance. Journal of World Business, Vol. 49: 611–632.

Calipha, R., Tarba, S. Y. and Brock, D. M. 2010. Mergers and acquisitions: A review of phases, motives, and success factors. Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions, Vol. 9: 1–24.

Caves, R. E. 1990. Corporate mergers in international economic integration. Working paper, Centre for Economic Policy Research, Harvard University.

Caves, R. E. 1996. Multinational Enterprise and Economic Analysis. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cavusgil, T. S. and Zou, S. M. 1994. Marketing strategy–performance relationship: An investigation of the empirical link in export market ventures. Journal of Marketing, Vol. 58(1): 1–21.

Chen, C. and Findlay, C. 2003. A review of cross-border mergers and acquisitions in APEC. Asian-Pacific Economic Literature, Vol. 17 (2): 14–38.

Child, J., Falkner, D. and Pitkethly, R. 2001. The Management of International Acquisitions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cycyota, C. S. and Harrison, D. A. 2002. Enhancing survey response rates at the executive level: Are employee- or consumer-level techniques effective? Journal of Management, Vol. 28 (2): 151–176.

Cui, L., Meyer, K. E. and Hu, H. W. 2014. What drives firms’ intent to seek strategic assets by foreign direct investment? A study of emerging economy firms. Journal of World Business, Vol. 49: 488–501.

Danbolt, J. 2004. Target company cross-border effects in acquisitions into the UK. European Financial Management, Vol. 10 (1): 83–108.

Datta, D. and Puia, G. 1995. Cross-border acquisitions: An examination of the influence of relatedness and cultural fit on shareholder value creation in US acquiring firms. Management International Review, Vol. 35: 337–359.

Deng, P. 2009. Why do Chinese firms tend to acquire strategic assets in international expansion? Journal of World Business, Vol. 44: 74–84.

Deshpande, R. 1982. The organizational context of market research use. Journal of Marketing, Vol. 46 (3): 91–101.

Economist, The. 1999. Business: faites vos jeux. The Economist, 353(8148): 63.

Eun, C. S., Kolodny, R. and Scheraga, C. 1996. Cross-border acquisitions and shareholder wealth: Tests of the synergy and internalization hypotheses. Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 20: 1559–1582.

Forbes (2015) Strong Q4 Activity Makes 2014 the Best Year for M&Amp;A since Downturn. Forbes Online. Accessed on 15 February 2015. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2015/01/07/strong-q4-activity-makes-2014-the-best-year-for-ma-since-downturn/.

Gaughan, P. A. 1991. Mergers and Acquisitions. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Gomes, E., Angwin, D., Weber, Y. and Tarba, S. Y. 2013. Critical success factors through the mergers and acquisitions process: Revealing pre- and post-M&Amp;A connections for improved performance. Thunderbird International Business Review, Vol. 55: 13–36.

Gomes, E., Weber, Y., Brown, C., and Tarba, S.Y. (2011). Mergers, Acquisitions and Strategic Alliances: Understanding the Process. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Graham, J. R. and Harvey, C. R. 2001. The theory and practice of corporate finance: Evidence from the field. Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 60 (2): 187–243.

Granstrand, O. and Sjolander, S. E. 1990. Managing innovation in multi-technology corporations. Research Policy, Vol. 19: 35–60.

Haleblian, J., Devers, C. E., McNamara, G., Carpenter, M. E. and Davison, R. B. 2009. Taking stock of what we know about mergers and acquisitions: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, Vol. 35: 469–502.

Harzing, A. 1997. Response rates in international mail surveys: Results of a 22 country study. International Business Review, Vol. 6 (6): 641–665.

Hennart, J. F. and Park, Y. R. 1993. Greenfield versus acquisition: The strategy of Japanese investors in the United States. Management Science, Vol. 39: 1054–1070.

Hill, C. W. L., Hwang, P. and Kim, W. C. 1990. An eclectic theory of the choice of international entry mode. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 11: 117–128.

Hitt, M. A., Harrison, J. S. and Ireland, R. D. 2001. Mergers and Acquisitions: A Guide to Creating Value for Stakeholders. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hopkins, H. D. 1999. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions: Global and regional perspectives. Journal of International Management, Vol. 5: 207–239.

Ingham, H., Kran, I. and Lovestam, A. 1992. Mergers and profitability: A managerial success story? Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 29 (2): 195–208.

Jansson, K., Kirk-Smith, M. and Wightman, S. 1994. The impact of the single European market on cross-border mergers in the UK manufacturing industry. European Business Review, Vol. 94 (2): 8–13.

Kang, N. and Johansson, S. 2000. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions: Their role in industrial globalisation. Working paper, Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry, OECD.

Kesner, I. F., Shapiro, D. L. and Sharma, A. 1994. Brokering mergers: An agency theory perspective on the role of representatives. Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 37 (3): 703–721.

Kohli, R. and Mann, B. J. S. 2012. Analyzing determinants of value creation in domestic and cross-border acquisitions in India. International Business Review, Vol. 21: 998–1016.

KPMG Management Consulting 1998. Mergers and Acquisitions in Europe. Research report.

Kreitl, G. and Oberndorfer, W. 2004. Motives for acquisitions among engineering consulting firms. Construction Management and Economics, Vol. 22: 691–700.

Levy, H. and Sarnat, M. 1970. Diversification, portfolio analysis and the uneasy case for conglomerate merger. Journal of Finance, Vol. 25: 795–802.

Madhok, A. 1997. Cost, value and foreign market entry: The transaction and the firm. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 18 (1): 39–63.

Manne, H. 1965. Mergers and the market for corporate control. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 73 (2): 110–120.

Martin, X., Swaminathan, A. and Mitchell, W. 1998. Organizational evolution in the interorganizational environment: Incentives and constraints on international expansion strategy. Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 43: 566–601.

McCann, J. E. 1996. The growth of acquisitions in services. Long Range Planning, Vol. 29 (6): 835–841.

Moeller, S. B. and Schlingemann, F. P. 2005. Global diversification and bidder gains: A comparison between cross-border and domestic acquisitions. Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 29 (3): 533–564.

Mueller, D. C. 1969. A theory of conglomerate mergers. Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 83: 643–659.

Mukherjee, T. K., Kiymaz, H. and Baker, H. K. 2004. Merger motives and target valuation: A survey of evidence from CFOs. Journal of Applied Finance, Fall/Winter: 7–24.

Nicholson, R. R. and Salaber, J. 2013. The motives and performance of cross-border acquirers from emerging economies: Comparison between Chinese and Indian firms. International Business Review, Vol. 22: 963–980.

Ohmae, K. 1989. The global logic of strategic alliances. Harvard Business Review, March–April: 143–154.

ONS. 2014. Mergers and acquisitions involving UK companies, Q4 2013. Office for National Statistics UK. Accessed on 15 February 2015. Available at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/international-transactions/mergers-and-acquisitions-involving-uk-companies/q4-2013/stb-m-a-q4-2013.html#tab-Transactions-Abroad-by-UK-Companies.

Papadakis, V. M. and Thanos, I. C. 2010. Measuring the performance of acquisitions: An empirical investigation using multiple criteria. British Journal of Management, Vol. 21: 859–873.

Park, B. and Ghauri, P. N. 2011. Key factors affecting acquisition of technological capabilities from foreign acquiring firms by small and medium sized local firms. Journal of World Business, Vol. 46: 116–125.

Pfeffer, J. and Salancik, G. R. 1978. The External Controls Of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. New York: Harper and Row.

Porter, M. E. 1987. From competitive advantage to corporate strategy. Harvard Business Review, Vol. 65 (3): 43–59.

Ravenscraft, D. J. and Scherer, F. M. 1987. Mergers, Sell-offs, and Economic Efficiency. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Roll, R. 1986. The hubris hypothesis of corporate takeovers. Journal of Business, Vol. 59 (2): 197–216.

Rostand, A. 1994. Optimizing managerial decisions during the acquisition integration process. Paper presented at the 14th Annual Strategic Management Society International Conference, Paris.

Rugman, A. M. 1982. New Theories of multinational Enterprise. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Rui, H. and Yip, G. S. 2008. Foreign acquisitions by Chinese firms: A strategic intent perspective. Journal of World Business, Vol. 43: 213–226.

Schmitz, P. W. and Sliwka, D. 2001. On synergies and vertical integration. International Journal of Industrial Organization, Vol. 19: 1281–1295.

Schoenberg, R. and Seow, L. M. 2005. Cross-border acquisitions: A comparative analysis. Paper presented at the 47th Annual Conference of the Academy of International Business, Quebec.

Servaes, H. 1991. Tobin’s Q and the gains from takeovers. Journal of Finance, Vol. 46: 409–419.

Seth, A. 1990. Value creation in acquisition: A re-examination of performance issues. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 11: 99–111.

Seth, A., Song, K. P. and Pettit, R. 2000. Synergy, managerialism or hubris? An empirical examination of motives for foreign acquisitions of US firms. Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 31 (3): 387–405.

Shimizu, K., Hitt, M., Vaidyanath, D. and Pisano, V. 2004. Theoretical foundations of cross-border mergers and acquisitions: A review of current research and recommendations for the future. Journal of International Management, Vol. 10: 307–353.

Sirower, M. 1997. The Synergy Trap. New York: The Free Press.

Sudarsanam, P. S. 1995. The Essence of Mergers and Acquisitions. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Trautwein, F. 1990. Merger motives and merger prescriptions. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 11 (4): 283–295.

Uddin, M. and Boateng, A. 2011. Explaining the trends in the UK cross-border mergers and acquisitions: An analysis of macro-economic factors. International Business Review, Vol. 20: 547–556.

UNCTAD. 2000. World Investment Report 2000: Cross-border Mergers and Acquisitions and Development. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

Vasconcellos, G. M. and Kish, R. J. 1998. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions: The European–US experience. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, Vol. 8: 431–450.

Vermeulen, F., and Barkema, H. 2001. Learning through acquisitions. Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 44 (3): 457–476.

Walter, G. A. and Barney, J. B. 1990. Research notes and communications: Management objectives in mergers and acquisitions. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 11 (1): 79–86.

Weber, Y. and Tarba, S. Y. 2011. Exploring culture clash in related mergers: Post-merger integration in the high-tech industry. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, Vol. 19 (3): 202–221.

Weber, Y., Tarba, S. Y. and Öberg, C. 2014. A Comprehensive Guide to Mergers and Acquisitions: Managing the Critical Success Factors across Every Stage of the M&Amp;A Process. New York and London: Pearson and Financial Times Press.

Weber, Y., Tarba, S. Y. and Reichel, A. 2009. International mergers and acquisitions performance revisited: The role of cultural distance and post-acquisition integration approach implementation. Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions, Vol. 8: 1–18.

Weber, Y., Tarba, S. Y. and Reichel, A. 2011. International mergers and acquisitions performance: Acquirer nationality and integration approaches. International Studies of Management and Organization, Vol. 41 (3): 9–24.

Weber, Y., Tarba, S. Y. and Rozen-Bachar, Z. 2011. Mergers and acquisitions performance paradox: The mediating role of integration approach. European Journal of International Management, Vol. 5 (4): 373–393.

Weber, Y., Tarba, S. Y. and Rozen-Bachar, Z. 2012. The effects of culture clash on international mergers in the high-tech industry. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, Vol. 8 (1): 103–118.

Weston, J. and Weaver, S. 2001. Mergers and Acquisitions. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Weston, J., Siu, J. A. and Johnson, B. 2001. Takeovers, Restructuring and Corporate Governance. New York: Prentice-Hall.

Williamson, O. E. 1975. Market and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications. New York: The Free Press.

Zheng, N., Wei, Y., Zhang, Y. and Yang, J. 2016. In search of strategic assets through cross-border merger and acquisitions: Evidence from Chinese multinational enterprises in developed economies. International Business Review, Vol. 25 (1): 177–186.