Research design, case presentation and analysis

Research design

Following the argumentation of the previous section, specific post-acquisition integration activities – especially in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries – are still under-researched (Patzelt et al. 2012; Schweizer 2012). Miles and Huberman (1994) suggest that researchers should use a qualitative research design when there is a clear need for an in-depth understanding, for local contextualization, and for the points of view of the people under study. Thus, the present study is based on a detailed analysis of a single, exploratory case study. This is in line with Yin (1994), who states that case studies can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes. This is also supported by the argumentation of Eisenhardt (1989, 1991).

In the context of M&A, Larsson (1990) argued that case studies are particularly appropriate for the study of M&A integration processes, given the need for detailed, contextual descriptions of very sensitive data. Moreover, the use of case studies in the context of M&As is in line with Bower’s (2001, 2004) recommendations as well as those of Hunt (1990), Javidan et al. (2004), and Napier (1989). During the last decade, using a qualitative approach in M&A research has become increasingly popular. Graebner (2004, 2009) and Graebner and Eisenhardt (2004) have used a qualitative approach for their analysis of M&A in the entrepreneurial high-technology sector. Melkonian et al. (2011) and Monin et al. (2013) have used a qualitative case-study in their analysis of the post-merger integration process between Air France and KLM. Riad and Vaara (2011), Vaara and Tienari (2011), and Riad et al. (2012) have also employed a qualitative approach in the context of international M&A activities.

We conducted preliminary unstructured interviews with industry experts to obtain an appropriate degree of relevance and structure. We applied semi-structured interviews to gain comparative qualitative data for the present case study. In addition to that, we analyzed archival documents and detailed write-ups, all included in a case-study database, and collected additional documents, such as annual reports, press releases, internal memos, procedures, and documents. To insure internal validity, we used multiple iterations and follow-ups during the analysis. Looking at multiple companies and analyzing comparative findings established external validity.

As noted before, our principal research question is: how do pharmaceutical firms successfully integrate acquired biotechnology firms during the post-acquisition process? The framework selected for the within-case analysis is based on the semi-structured questionnaire used for the interviews. The within-case analysis utilized a matrix technique for comparative analysis across interviews within one case (Miles and Huberman 1994). The resulting matrices allow visual identification of patterns in the post-acquisition integration process. The topics chosen for the questionnaire have been developed by making a first review of the post-merger/post-acquisition and M&A literature and studies as well as preliminary discussions with industry experts and has also been continuously updated based on useful remarks which came up during the different interviews.

All interviews were fully taped and transcribed into a protocol. Each interview was then structured and coded to facilitate within-case analysis. Based on the within-case analysis – using the above-mentioned matrix technique (Miles and Huberman 1994) – we developed a comprehensive case description based on identified patterns and summarized our findings in a practical post-acquisition integration framework.

Corporate profiles

The roots of Merck KGaA reach back into the seventeenth century, when, in 1668, Friedrich Jacob Merck purchased the Engel-Apotheke in Darmstadt. In 1827, Heinrich Emanuel Merck began the large-scale production of alkaloids, followed by plant extracts and many other chemicals. By the end of the nineteenth century, Merck offered about 10,000 products, which were exported to many countries, and had founded subsidiaries throughout the world. In 1889, Georg Merck took over the office in New York and established Merck and Co., which started the local production of chemicals in the U.S. ten years later. After World War I, Merck lost many of its foreign affiliates, among them its U.S. affiliate Merck and Co., which became an independent American company. Since then, the latter has become one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world. Both companies agreed that the name “Merck” is exclusively used in the U.S. and Canada by Merck and Co. and in Europe and the rest of the world by Merck KGaA. In 1999, EMD Pharmaceuticals Inc. was founded by Merck KGaA in order to manage the North American pharmaceutical operations. In 1995, the legal form of Merck – until then managed as an OHG (open partnership) – was transformed into a KGaA (partnership limited by shares). The Merck Group’s operating activities are grouped under Merck KGaA, in which E. Merck, holding the Merck family’s equity interest, is a general partner with a 74 percent stake, while the shareholders have a 26 percent stake.

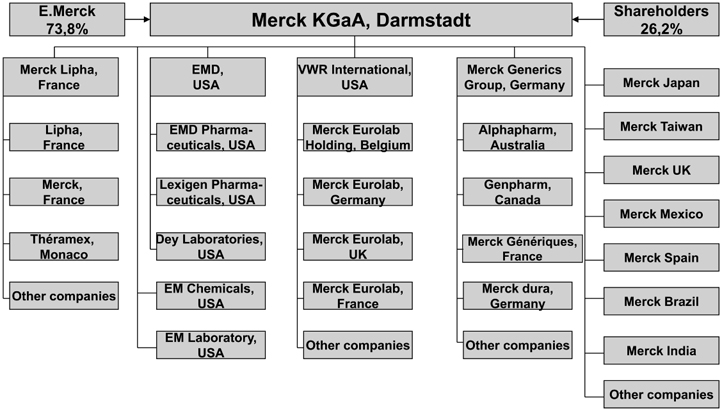

At the time of the acquisition, the Merck Group, still headquartered in Darmstadt, conducted its international business in four business sectors – pharmaceuticals, laboratory products, laboratory distribution, and specialty chemicals – with sales of €6.7 billion in 2000. Merck is represented by 209 operating activities in 52 countries and employs 33,000 people worldwide. Fifty-two percent of its employees work in Europe, 30 percent in North and Latin America, and 18 percent in Asia, Australia, and Africa. In fiscal 2000, Merck reported an operating profit of €0.7 billion on sales of €6.7 billion. Europe accounted for 38 percent of sales, North and Latin America 45 percent, and Asia, Australia, and Africa the remaining 17 percent. Figure 6.1 provides a simplified overview of Merck’s organizational structure.

Merck’s pharmaceutical sector consists of three main business segments: ethicals, generics, and consumer healthcare. In the ethicals segment the different therapeutic areas are: cardiovascular, metabolism/diabetes, women’s health, central nervous system, and (notably) cancer/oncology. Following a strategic review of its pipeline, the group’s strategic focus in the pharmaceuticals business sector lays in cardiovascular diseases and metabolism/diabetes. Moreover, Merck aims to gain a leadership position in the field of oncology and strengthen its position in the growth market of women’s health. The pharmaceuticals business sector invested €453 million in the research and development of new drugs in 2000, which represents 16 percent of the total sales in this segment, and around 83 percent of the total R&D expenditure of the Merck Group. Sales in the pharmaceuticals business sector rose by 2 percent in 2000 to €2.914 million (previous year: €2.8 billion), representing 43 percent of the Merck Group’s total sales.

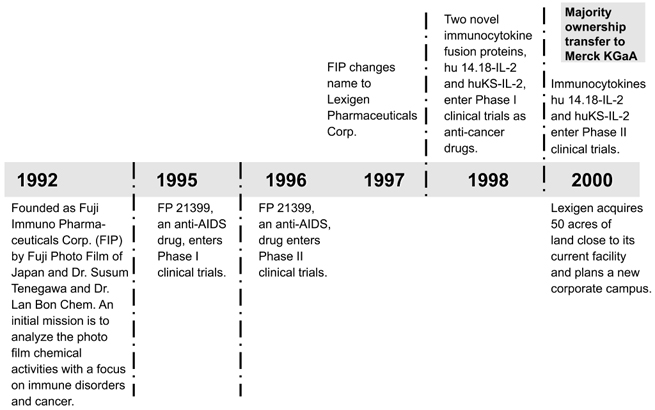

Lexigen Pharmaceuticals Corp. (formerly Fuji Immuno Pharmaceuticals Corp.) was founded in 1992 by Professor Susumu Tonegawa, winner of the 1987 Nobel Prize for Medicine, and Harvard Professor Lan Bo Chen. The company is engaged in the development of drugs and genetically engineered products to treat cancer, immune system disorders, and other diseases. Apart from that, Lexigen has developed a broad technology platform with the aim of generating new therapies. The company develops certain immunocytokines as cancer treatments, and simultaneously works on the immunocytokine concept as a broad, proprietary technology base. Lexigen is developing two particular immunocytokines for the treatment of cancer, both of which are in clinical trials. One is for the treatment of gastrointestinal, pancreatic, and prostate cancers, and a second is for the treatment of small lung cancers and melanoma. Lexigen has also developed an active substance, FP-21399, for use in the treatment of AIDS. This anti-AIDS compound inhibits fusion of the virus with its target cell. Moreover, Lexigen is developing a new diagnostic procedure that is capable of identifying cancer cells in the bloodstream with the help of computer-analysis methods. Besides some academic relationships with universities in the Boston area, Lexigen had no industrial collaborations prior to the takeover. Figure 6.2 summarizes the most important phases of Lexigen’s history.

Description of the M&A and integration process

Acquisition process and motives

On 16 December 1998, Merck announced that it had acquired 57 percent of Lexigen Pharmaceuticals Corp., located in Lexington, MA. The purchase comprised the exclusive rights to new technologies and important fundamental patents for pharmaceutical research, including a new diagnostic process to identify cancer cells in the blood with the help of computer analysis. At that moment, Lexigen had a total of twenty-seven employees on its payroll. Merck did not disclose the purchase price for the shareholding.

The acquisition of Lexigen was carried out for several reasons. In a first step, this acquisition must be regarded from a broader strategic perspective, which can best be expressed in the words of Hans Joachim Langmann, a member of Merck’s executive board (Merck KGaA 2000: 4):

The 23% increase in our research expenditure … was used to boost the development of new drugs for treating cancer in particular. The same strategy was also behind the acquisition of the U.S. research company Lexigen and the conclusion of key license agreements. We aim to become one of the leading companies in the oncology sector.

Thus, Merck is striving to become a leader in the area of cancer research in the future. It attacks cancer with four diverse therapeutic approaches: angiogenesis inhibitors; monoclonal antibodies; immunotherapeutics; and immunocytokines.

Besides this general motive, the second major motive behind the acquisition was that Lexigen had an interesting technology platform in the field of immunocytokines, to which Merck wanted to gain access. At that point in time, Lexigen had two oncology products undergoing Phase I clinical trials, and Merck hoped to launch them by 2005 as potential blockbusters. One of the products is designed for the treatment of gastrointestinal, pancreatic, and prostate cancer, and the other is for the treatment of small cell lung cancer and melanoma. Apart from that, Lexigen has developed a new diagnostic procedure that is able to identify cancer cells in the bloodstream with the help of computer-analysis methods.

The third major reason was that Merck wanted to strengthen its pharmaceutical position in the U.S., which it considered one of the most important markets. It was expected that Lexigen’s presence in the Boston research community and its links to renowned research centers would lead to an increase in creativity and innovative capacity.

Lexigen had a patent issued on a certain technology, the technology of immunocytokines. This was a technology Merck wanted to get a license for, because Merck needed it for its own oncology research. Then it turned out that Lexigen itself had some financial problems and was up for sale. At Merck, it was decided to acquire the company with the aim of establishing a pharmaceutical pillar in the U.S.; more precisely, in the Boston area.

(Integration manager)

For Lexigen, this acquisition provided access to the vast resources that can be provided only by a large pharmaceutical company. Lexigen needed these resources due to the fact that it was in the middle of clinical Phases I/II, which required a lot of money that Lexigen did not have. Therefore, the company was searching for a potential buyer or investor. Helped by the fact that there had already been some preliminary negotiations between Merck and Lexigen concerning a specific patent in the field of immunocytokines, Merck finally acquired Lexigen.

Organizational integration

As far as the organizational integration is concerned, a distinction between the original intended plan and the final structure must be made, as the structure of Merck’s pharmaceutical business itself changed only a few months after the acquisition. Thus, the description of the organizational integration and the different organizational elements mainly focuses on the structure that was finally established, rather than the original integration plans, which were never implemented. A Lexigen executive described this rather troublesome process as follows:

In reality, there is not a very good definition of what the responsibilities and structure are, or how the interaction should be. It is about two years since the acquisition of Lexigen by Merck and more than one and a half since the creation of EMD. And yet, there is still a lot of time and effort being spent on defining what the roles are, and what the responsibilities will be.

(Anonymous interviewee)

According to the original plan, Lexigen was to cover nearly the whole pharmaceutical value chain, including basic R&D as well as clinical development and marketing. In addition, the company was meant to retain a lot of autonomy, as the following quotation indicates:

When the small company was first acquired there was a very clear statement from the CEO of Merck that the small company should retain some of the attributes that make it small, dynamic and very fast; that these, by themselves, are assets to Merck and that they should not become the same operating procedures as Merck. The same day that this comment was made, we began to receive instructions from other divisions within Merck about how we should operate to be like Merck … So, there continues to be an expectation within Merck that we will do things in conformity, as they are done in Merck, but also an expectation that we should operate with a high level of independence and some level of separateness.

(Anonymous interviewee)

This original plan was short lived. In fact, it was never really implemented, because half a year later Merck announced a substantial reorganization of its pharmaceutical business, with a special focus on its presence in the U.S. Thus, this reorganization must be kept in mind when discussing the further organizational integration. This reorganization changed the role that was to be attributed to Lexigen in a fundamental way. Merck had set up a separate company to focus on growth in its pharmaceutical business in the U.S.: EMD Pharmaceuticals, Inc., located in Durham, N.C., now serves as the North American headquarters for the Merck Pharma Division. On 1 June 1999, Matthew Emmens was named president and CEO of the newly created company. The new headquarters, located near Research Triangle Park, has the task of creating relationships with researchers at important research centers and of coordinating Merck’s North American drug development, marketing, and sales activities, including those of Lexigen. To enhance the organizational effectiveness, the management structure of the Pharma Division was streamlined and the number of board members was reduced. An integration manager commented on this reorganization:

It was decided that most of the biologic research is to be with Lexigen. Their main responsibility lies in biological research, especially everything that has to do with proteins. It can be seen as a center of excellence. From that point of view it was not a bad decision to separate research from clinical development. I don’t know if a local separation was really necessary. However, the separation and to say that Lexigen should do this, what it does best, was an appropriate decision. But it wasn’t the original intention at the beginning. And this reorganization caused quite a stir.

Thus, at this specific moment – with the creation of EMD as the new North American headquarters for the Merck Pharma Division – the role of Lexigen was redefined. Ever since, Lexigen has been considered one of Merck’s key research facilities as well as an entry point into the U.S. pharmaceutical market and the Boston scientific community. Henceforth, Lexigen is considered Merck’s worldwide center of excellence for biological entities. It is to generate drug candidates through its research, while EMD is providing the development and commercialization expertise and Merck supplies its global presence and management capabilities. Lexigen’s role centers on basic research and on acting as a “kind of supplier”:

At the beginning, everything was supposed to be in the hands of Lexigen, including clinical development. Now, one can rather call it a “disintegration.” Lexigen is an important research facility for Merck, one of the most important suppliers for the biotech platforms. The research unit Lexigen will play only a supportive role for the clinical development of the projects, which will be done at Durham.

(Integration manager)

From a strategic point of view, only the president of Lexigen, Stephen Gillies, is involved in the process of clinical development, because he is at the same time vice-president for research at EMD, and therefore participates in the respective strategy meetings. Lexigen itself is “only” a research unit and, thus, not really involved in overall strategy-making. However, as far as its research activities are concerned, Lexigen has a high degree of autonomy and its own research budget. The company has to undergo a general review process and has to fulfill certain objectives, but it carries out its research completely on its own.

People at Lexigen are part of the worldwide research team at Merck. Lexigen itself – besides Stephen Gillies – is not part of the strategy-making process. A decision has been made that EMD will take over that part and coordinate the further development.

(Integration manager)

In terms of reporting and controlling systems, Lexigen has no responsibility at all, because everything is centrally managed by EMD. Lexigen only controls the research budget, which is granted by EMD.

As far as reporting and controlling is concerned, everything is managed by EMD. Lexigen receives its money from EMD via a specific allocation mechanism. Lexigen is now part of EMD and doesn’t belong directly to Merck any more. At Lexigen, there are no controlling or reporting structures in place. A company like Lexigen which started with fifteen people does not have the necessary departments to handle eighty people. Lexigen has its own research budget and its own president, and that’s it.

(Integration manager)

As far as the general collaboration between Lexigen and Merck is concerned, there is a wide gap between the two sides’ expectations. Lexigen wants to continue to work efficiently, as it has done in the past. This means very little expenditure but high risk. In contrast, Merck wants to make everything as secure as possible, which has led to some delays in terms of decision-making. Although Merck provides the necessary know-how and resources for the next steps of the development process, this obvious contradiction has created some problems from the point of view of Lexigen, as the following quotation reveals:

Biotech does not operate by being conservative. Biotech operates by taking risks, by being dynamic, by moving very quickly, by trying different ideas on a trial basis. If it works, you continue. If it doesn’t work, you try something else. It moves very, very quickly. The expectations for the development of ideas and the development of products both go faster than the operational tempo of a large corporation or the operational tempo of a large conservative corporation.

(Anonymous interviewee)

This quotation shows that the day-to-day business of the biotech company changed completely. On the one hand, this has one important advantage because the company has more resources than before. On the other hand, however, there is a severe drawback for the future management of such a company because there is a clear change in the way of doing business:

If a small biotech company fails to achieve a goal for two years, that means the death of the company. In the structure of a big company, that is not true. It is acceptable to continue to fail to meet a goal, because it is not just a small biotech company any more; it is also part of a large corporation. There is money to support it. So, having the structure behind it allows failure happen that could not take place if we were on our own … This is good and bad. On the one hand, it allows time, which is necessary to develop ideas; on the other hand, it allows us to adopt a slower operational tempo and not accomplish goals that we would have achieved otherwise. That is not necessarily a benefit.

(Anonymous interviewee)

At first, responsibility for Lexigen came under the auspices of the oncology business team at Merck’s headquarters in Darmstadt, especially its head Klaus Hoenneknoewel. In addition, the decision to acquire Lexigen was advocated by this team. The reorganization of the Phama Division had been decided at the top of the company and not by the oncology team. Aside from that, this reorganization resulted in a change of responsibility for Lexigen, because the company was put under the auspices of EMD in Durham, N.C. Hence, the president of Lexigen, Stephen Gillies, reports directly to the president and CEO of EMD, Matthew Emmens, who in turn reports directly to the chairman of Merck’s Executive Board in Darmstadt, Bernhard Scheuble. This reporting structure provoked some discontent at Lexigen, because “you have three different visions of how one area – the oncology area – should work and within the space of one and a half years there are three different major structural changes” (anonymous interviewee).

With regard to a possible transfer of knowledge or a specific technology from Lexigen to Merck, it can be said that there was no real transfer, because the biotech expertise is within Lexigen. Instead, some of the projects in the field of biologics at Merck were stopped and transferred to Lexigen.

From a cultural point of view, different levels must be distinguished. In a first step, there is a difference in terms of country culture between the U.S. and Germany which is reflected in different ways of working:

In the U.S. – irrespective of the industry – you think much more in a matrix structure and work together as a team … more than you do in Germany. In Germany, the matrix structure is well known, but it is the line function which gives the directives and defines roles and responsibilities … Interactive communication and collaboration as a team are very difficult in a context where the line function is dominant. It took me a lot of time and effort to get the team members – who were really top people in their respective fields – to work effectively together. But in the end, it worked out quite well.

(Integration manager)

Apart from this general difference, people expected problems resulting from the fact that big pharma needs to collaborate with “small biotech.” This is reflected in various employees’ statements, such as “Now we have to cope with the Germans and big pharma” (from a Lexigen employee) and “Those people at Lexigen have no clue about what it really means to develop a drug” (from a Merck employee). Obviously, the two sides had different opinions on how to do business. If Lexigen had remained independent, it would have continued to pursue the strategy of developing a medicine and then building up the corresponding organization. In contrast to this traditional biotech strategy, Merck takes a big pharma approach, which consists of building the structure and organization first and then developing the product. In consequence, one of the executives at Lexigen concluded that “because of the corporate structure and culture within Merck, there is an inability to make decisions” (anonymous interviewee).

At the moment of the acquisition, Lexigen had twenty-seven employees, none of whom left after the deal was done. There were several reasons for this. Lexigen itself was mainly dominated by one person, its president and owner of all its major patents, Stephen Gillies. The whole organization was more or less tailor-made for him and he had everything under his control. Nothing really changed too much after the acquisition for Lexigen’s employees, because the company was granted autonomy in the field of research, with Gillies remaining in charge of everything. So he remained the employees’ boss and only contact. Apart from the fact that a few other important employees were contractually bound, the overall situation for the company improved as they now had access to resources they had never enjoyed before. Thus, they continued to do what they had always done – research.

Stephen Gillies continued to be their boss. They did not care about the integration, because they were not affected. Only those involved in the development project, about four or five people, were affected. But they were bound by contract.

(Integration manager)

Organization of the integration process

The organization of the integration process was not as easy and straightforward as expected. There was some kind of integration process immediately after the acquisition. However, because of the reorganization decision of Merck’s Pharma Division, this integration never became effective. Thus, the following description tries to combine both approaches by comparing some of the immediate actions with later decisions.

The original integration was a relatively short process because only twenty-seven people at Lexigen were involved. A merger team was created under the direction of Klaus Hoenneknoewel, head of the oncology business team in Darmstadt, consisting of four people from his team and four from Lexigen. This merger team carried out the integration by bringing together people from the different groups and preparing the collaboration. Most of the integration was to be done on a day-to-day working relationship. In this context, one integration manager took a leading role and served as an interface manager between Lexigen and Merck, and then between Lexigen and EMD. This integration manager was a German scientist who had worked in the U.S. and he was employed by Lexigen on the recommendation of Merck’s headquarters in Darmstadt. His main task was to get people to work together in teams and ensure the exchange of relevant skills and knowledge.

Apart from that, there was no real transfer of employees to or from either side during the integration process. For instance, no executive from Darmstadt was sent to Lexigen in order to make them familiar with the company’s systems and structure, because a new structure was created through the formation of EMD, changing roles and expectations with regard to Lexigen. This decision was not made (and not really supported) by the oncology business team; rather, it was made by Merck’s Executive Board. An executive at Lexigen described the situation as follows:

I do know that there has been a series of indecisive events … [and] some decisions that were made were short-lived. So, a particular vision is defined, discussed. The vision is made, we pursue that vision, and then a few months later it changes. And a few months after that it changes again. And a few months later it changes again, which of course prevents effective integration … I think that within the different companies people are finding it difficult, because they don’t know what their sphere of operations is and how it is related to the others. So, at the individual level, at the group level within the company here, within the company EMD, the goals for those personnel may change all of a sudden.

(Anonymous interviewee)

This reveals that people at Lexigen were not content with the decisions that were being made at the top of the group. Moreover, it highlights one of the major lessons Merck learned concerning the acquisition and especially the subsequent integration process: decisions must be made as quickly and as clearly as possible in order to prevent insecurity at the individual level. Furthermore, there was no clear communication about these issues, which exacerbated the sense of insecurity. Another problem was the difference in opinion over how to run the business. While big pharmaceutical companies prefer to establish the necessary organization first and then develop the product, small biotech companies tend to do the opposite. Hence, it is necessary to ensure a smooth transition from the early phases of the development process, which had already been carried out at Lexigen, to the later ones, which were subsequently under the control of Merck.

The first integration process was carried out quickly … OK, a few experts were missing – [they] were at neither Merck nor Lexigen and the responsibility for them was also not well defined. That was a mistake, but the integration process itself was initiated as quickly as possible and could also have been run that way, if there had not been the creation of EMD. But that is another story, which of course clearly affects the integration of Lexigen and needs to be taken into account. Hence, it is difficult to say whether the original plan would have been successful or not.

(Integration manager)

Analysis of the M&A and integration process

This section analyzes the M&A deal between Merck and Lexigen. It should be remembered that the original integration plans were never really implemented (which happens quite often in M&As), but rather were replaced by a major reorganization within Merck a few months after the acquisition.

First, the motives for the M&A transaction will be analyzed. As we saw above, Merck wanted to cement its position in the oncology sector and strengthen its presence in the U.S. pharmaceutical market by gaining access to the Boston research community. From this, the first major motive can be derived by concluding that the acquisition of Lexigen contributed to the long-run strategic objectives of Merck. In addition, Lexigen had a very interesting technology platform and two oncology products undergoing clinical trials with very promising sales potential (perhaps even the chance of becoming blockbusters) and therefore a substantial positive impact on operational results. Furthermore, Merck needed the immunocytokines patent in order to continue with its own research. Thus, the second major motive was more short term. Lexigen accepted the takeover offer because it needed money in order to proceed with its clinical trials. In addition, it gained access to a large pharmaceutical company’s resources.

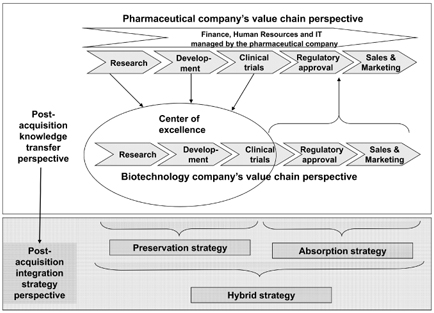

While analyzing the organizational integration and the different elements of organizational/structural integration, knowledge/competence integration and transfer as well as cultural and personnel integration, it is necessary to keep in mind the two identified major motives because they explain an important aspect of the integration and the subsequent reorganization. It is very difficult to determine whether there were two basic organizational integration strategies or whether there was one organizational integration strategy at two different levels. In the oncology business team’s original plan, the intention was that Lexigen should retain a high degree of autonomy in nearly every stage of the pharmaceutical value chain. This meant that Lexigen was to assume responsibility for R&D, clinical development, and sales and marketing in the U.S.

In this context, two points should be noted: Lexigen’s focus was solely on oncology; and Lexigen was a small biotechnology company with only twenty- seven employees at the time of the takeover, and it had no experience in clinical development or in running a larger pharmaceutical business. Therefore, it is quite easy to understand the rationale for the reorganization decision. The crucial question for Merck’s Executive Board was whether Lexigen – given its specific situation – would be able to ensure the long-run objective of strengthening Merck’s position in the whole U.S. pharmaceutical business sector, not merely oncology. The Executive Board decided that it would not, so they set up a separate company, EMD Pharmaceuticals. After that decision was made, Lexigen was free to play the role of a center of excellence for biological entities with the aim of conducting basic research and generating promising new drugs. These drugs would then be developed and commercialized by EMD in the U.S., with Merck supplying a global presence, management capabilities, and support. By establishing this structure, the Executive Board at Darmstadt hoped to meet the long-term objective of increasing Merck’s presence in the U.S.

What did this mean for the overall organizational integration strategy? The organizational integration strategy needs to be considered in close connection with the degree of autonomy that was granted. Research was clearly separated from development and commercialization. As far as basic research and the generation of new drugs were concerned, Lexigen was granted maximum autonomy and remained in full control of those aspects of the business. This was reflected in the fact that the president of Lexigen was also made vice-president of EMD, with responsibility for U.S.-wide research. Once Lexigen has identified a promising new drug, EMD takes over and assumes full responsibility for the further development and commercialization of the product; Lexigen has no role to play in this. Therefore, it is possible to draw the conclusion that the level of responsibility varies due to position along the pharmaceutical value chain. During the early stages of research, Lexigen has overall responsibility as well as a high degree of autonomy. Thus, it can be considered a “strategic leader” in that context (Bartlett and Ghoshal 1989). However, as soon as a promising drug has been identified – which represents a degree of progression along the pharmaceutical value chain – EMD assumes full responsibility for the product’s further development. Lexigen merely offers some support, if requested and needed. From this, it follows that the current clinical trials are managed by EMD at Durham, N.C., so the second major motive of the acquisition has been realized in accordance with the overall strategic direction.

In terms of strategy-making as well as reporting and budgeting, the decisions are made at EMD after consultation with Merck. Lexigen does not even have designated departments to perform these functions. It is involved only to the extent that Stephen Gillies is vice-president for research at EMD, in addition to being president of Lexigen. Furthermore, everything relating to reporting, controlling and human resources is managed by EMD on Lexigen’s behalf.

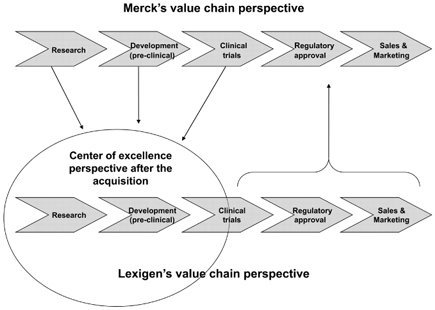

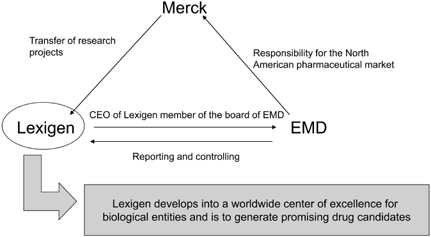

With regard to a possible knowledge transfer, it must be stressed that there was no transfer of knowledge from Lexigen to Merck. Instead, projects at Merck with a clear link to biologics and proteins were wound down and transferred to Lexigen because the latter is now the center of excellence within Merck for everything that has to do with biologics. “They [Lexigen] had people who had much more experience and knowledge in the field of proteins than the people at Merck” (integration manager). Thus, when asking who was the best in this field and who had the necessary knowledge, know-how and competence within the company, the clear answer was “Lexigen.” This made perfect sense, because it reflected one of the principal motives for the acquisition – the know-how and technology that Lexigen had at its disposal. Figure 6.3 summarizes Lexigen’s new role and how it developed.

Another question is how the clinical development of promising drugs will be carried out in the future. The answer to that question relates to the reorganization process and has nothing to do with the original integration plans. It is now the task of the dedicated “interface manager,” whose role has changed over time. At first he was more of an integration manager, whereas after the reorganization he became an interface manager, as he was responsible for the transfer of knowledge needed at Durham. In addition, Stephen Gillies, the holder of Lexigen’s major patents, will support future development activities at EMD. Moreover, so-called “translation research teams” will be introduced in order to support development activities at Durham. This new relationship is presented from a value chain perspective in Figure 6.4.

Figure 6.3 Relationship between Lexigen, Merck, and EMD

The cultural analysis can be subdivided into two different dimensions. First, there is the obvious cultural gap on a country level between U.S.-based Lexigen and the German company Merck. In this context, some problems arose due to different thinking with respect to command and control structures. In the U.S., the matrix structure and teamwork across different line functions is the dominant system. By contrast, in Germany, although the matrix structure exists, the line function is preeminent. This resulted in a few coordination and communication problems, but these were quickly resolved by the integration team.

Second, there is a very wide gap between the structure and thinking of big pharma – like Merck – and the way business is conducted at a small biotechnology company, such as Lexigen. Big pharmaceutical companies try to avoid risk, or at least reduce it as far as possible. This thinking underpins Merck’s approach to tackling a project or developing a drug: it first builds up the necessary structure and organization for the whole value chain and only then focuses on the development of the product. By contrast, small biotech companies, in this case Lexigen, develop the product first and then establish the necessary organization. One of the important reasons why they adopt this approach is that they do not have the necessary resources to build up elaborate structures before identifying a potential revenue generator. Now that Lexigen is part of Merck it is no longer the fast-acting, highly dynamic and high-risk-taking small biotechnology company it once was. It has become part of a much larger entity that acts according to different rules. Bearing this in mind, Lexigen employees’ complaints that “it is the expectation of a large corporation that the small company operates like them” (anonymous interviewee) are understandable because their company is no longer a small, independent firm. Its role within Merck therefore needs to be newly defined, and it takes more time to reach decisions than it did when Lexigen was an independent, small biotechnology company.

Notwithstanding these problems that were due to the cultural gap, both sides also gained from their liaison. On the one hand, Lexigen now has access to the money it needs to continue its research and push its products through clinical trials. This is done with the help of Merck, as Lexigen itself never went through the process of gaining regulatory approval when it was an independent company. On the other hand, Merck now has access to new technologies and some promising new drugs. The question is how the two organizations get along with each other in order to get the best out of the deal. All of the decisions relating to the realization of these advantages are made at Merck, not at Lexigen. The reorganization of Merck’s pharma business segment resulted in the definition of Lexigen’s role as a center of excellence for research within Merck (see Figure 6.4). Thus, Lexigen was tasked with undertaking basic research and generating promising drugs which would then be developed by EMD.

This reorganization has had an impact on the way Lexigen sees itself, although it always takes some time before such a change is fully accepted. One can draw the conclusion that Lexigen is no longer supposed to act in the same entrepreneurial way as it did before its acquisition. If Merck had not acquired Lexigen, the latter would have had to develop a product, push it through clinical trials, bring it to the market, and generate revenue from it. Since the acquisition, Lexigen can focus exclusively on undertaking basic research and generating promising new drugs. Therefore, its employees need to cultivate a spirit of discovery rather than a spirit of entrepreneurialism. Accepting this argumentation and the likelihood that the cultural gap between Merck and Lexigen will diminish, it is possible to go one step further and conclude that Lexigen – because its activities are now confined to the research field and it no longer has any role to play in the rest of the pharmaceutical value chain – has lost some of its former identity. This brings it closer to Merck, and, in turn, brings Merck closer to the fulfillment of the goals it had in mind when deciding to acquire Lexigen and subsequently reorganize its pharma business segment.

Given that Lexigen had only twenty-seven employees at the time of the deal and that it was not listed on any stock exchange (implying that stock option programs did not exist), any analysis of personnel integration issues is sure to be relatively short and straightforward. As mentioned earlier, no Lexigen employees left the company after the acquisition, probably because nothing changed for them. They kept their boss, Stephen Gillies, and they were assured that they could continue to undertake their research. Moreover, they had access to unprecedented resources, provided by Merck; and the top four or five Lexigen scientists were bound by specific contracts.

At this point, analysis of the organization of the integration process needs to be taken into account. It is again necessary to point out that the integration process cannot be separated from the subsequent reorganization process. Thus, both dimensions are covered in this analysis. The case description reveals one major problem in terms of responsibility. The acquisition and the early integration efforts were initiated and carried out by Merck’s oncology business team. At first, this team was put in charge of Lexigen. However, the subsequent reorganization decision of the Pharma Division was made at the very top of the company, not at the level of the oncology business team. As a result of this reorganization, responsibility for Lexigen was transferred from the oncology business team to EMD. This reveals that the original integration plans of the oncology business team did not enjoy the full support of Merck’s Executive Board.

The change in responsibility was one of the major reasons why the final integration of Lexigen following the reorganization decision took so long to complete and generated such uncertainty among Lexigen’s employees. This uncertainty is reflected in the following statement: “The problem can only be solved if someone is willing to realize a vision with the support of top management within Merck, and is willing to implement decisions and the vision from the top down” (anonymous interviewee). This comment not only reveals Lexigen employees’ frustration over the sluggishness of decision-making after the acquisition, but indicates that they held top management responsible for the problem. For example, the original integration efforts of the first merger team under the direction of Klaus Hoenneknoewel, head of the oncology business team, were never really effective. The first integration process itself was carried out quite quickly, but the subsequent reorganization – which implied some kind of “reintegration” – took much longer and was not communicated clearly to the employees.