Sut I Wong, Elizabeth Solberg, Paulina Junni, and Steffen Robert Giessner

Introduction

Mergers and acquisitions (M&As) have been increasingly used in the past decade as a strategic means for companies to gain competitive advantages (Lakshman 2011), such as knowledge capital management and international market penetration. Economic synergies obtained through domestic or international M&As are considered particularly important in the current global business environment (Lupina- Wegener 2013; Weber and Fried 2011). Notwithstanding this, M&As also come with challenges. It is well recognized that M&As are one of the most extreme forms of organizational change (Hogan and Overmyer-Day 1994). Research shows that approximately half of all M&As fail to achieve their anticipated outcomes and that the consequences of M&A failure are detrimental (Cartwright and Schoenberg 2006; Rees and Edwards 2009; Thanos and Papadakis 2012). The dysfunctional impact of M&A failure is not only evident in organizational outcomes, such as reduced productivity and market reputation (Paruchuri et al. 2006), but also in the reduced well-being of organizational members, as reflected in increased job insecurity and stress (Schweiger and Denisi 1991; Terry et al. 1996).

For decades, scholars and practitioners have been investigating the factors that contribute to the success of M&As (e.g., King et al. 2004; Lupina-Wegener 2013; Faulkner et al. 2012; Gomes et al. 2013; Haleblian et al. 2009). It has long been recognized that the success or failure of M&As depends crucially on the post-acquisition integration process (Weber and Tarba 2010, 2011), for which human resource management (HRM) practices are considered an important means to manage the human side of integration (Bramson 2000). In fact, there is evidence of a direct correlation between HR involvement and M&A success (Lin et al. 2006). In particular, the role of HRM in maintaining workforce stability (Bryson 2003) and reducing employee distress (Marks and Mirvis 2001) during post-acquisition integration are identified as key contributors to M&A effectiveness (Bryson 2003). Yet the role of HRM has been largely neglected in the M&A integration literature, and only recently has its importance received increasing attention (Marks and Mirvis 2011; Nikandrou and Papalexandris 2007; Sarala et al. Forthcoming; Weber and Fried 2011; Weber and Tarba 2010). While recent studies have highlighted the importance of HRM in acquisitions (e.g., the Human Resource Management journal dedicated two special issues to this topic in 2011), there has been no systematic review to synthesize the existing studies on the role of HRM in M&A. Therefore, a more comprehensive picture of the role that HRM plays in M&A integration is needed to help future research in this area. Accordingly, in this chapter we review studies in four theoretical streams (resource-based view; social identity view; cultural view; and organizational sensemaking view) that have received much attention in the M&A integration literature, but have never been systematically linked to the role of HRM in M&A. By doing so, we aim to contribute to the field by providing an overview of the multifaceted role of HRM in M&A integration, and to identify important areas for future research.

The chapter is organized as follows. First, we review the literature of post- acquisition integration. After this, we discuss four relevant theoretical landscapes from which M&As are typically assessed—including the resource-based view, social identity theory, acculturation theory, and organizational sensemaking theory—to identify various ways in which HRM may help the M&A process and contribute to M&A success. Finally, we discuss three important HRM contingencies factors (HRM centrality, HRM power, and HRM ambiguity) that impact the effectiveness of HRM practices in facilitating the M&A integration process. We conclude by providing theoretical and practical implications for how HRM may be implemented in M&As and suggest areas for future research.

Post-acquisition integration

Post-acquisition integration refers to changes that are made to the merging firms’ structures, practices, systems, and cultures in order to create acquisition synergies (Pablo 1994). Previous research has tended to view changes relating to firm structures, practices, and systems as broadly relating to operational or ‘task’ integration, whereas socio-cultural or ‘human’ integration concerns changes in the cultures and identities of the merging firms (e.g., Birkinshaw et al. 2000). Both task and human integration aim to create value post-acquisition. However, task integration is more formal and concerns strategic choices related to the extent and speed of integration between the merging firms (Haspeslagh and Jemison 1991), whereas human integration is considered the softer side of M&A integration, as it generally relates to managing employee experiences and attitudes toward the M&A.

Studies focusing on the task-related side of M&A integration have tended to draw on the resource-based view, arguing that the combination of the merging firms’ resources post-acquisition is critical for value creation. The underlying assumption is that there is a ‘strategic fit’ between the acquiring and acquired firm, which allows them to create synergies from combining similar or complementary resources (e.g., Almor et al. 2009). The prevailing theme in these studies has related to the amount of integration versus autonomy needed in order to create synergies, and studies have shown that there is a trade-off between the two. While integration facilitates the transfer of knowledge and resources between the firms, the removal of autonomy accompanied by integration can disrupt the acquired firm, for example through higher employee turnover, which reduces the value of the expected synergies (Haspeslagh and Jemison 1991). For instance, autonomy removal can reduce the acquired firm’s innovative capabilities (Puranam et al. 2006; Puranam and Srikanth 2007), impede the transfer of tacit knowledge from the acquired firm to the parent firm (Ranft 2006), and weaken the acquired firms’ external ties (Spedale et al. 2007). Recent studies have shown that the degree of autonomy granted to the acquired firm can change over the course of integration. For instance, Almor et al. (2009) and Schweizer (2005) show that acquirers of biotech companies tend to grant more autonomy to the acquired firms at first, but then increase the degree of integration in selected areas as they get to know the acquired firm’s operations. Furthermore, researchers have begun to explore the role of the acquired firm in M&A value creation (e.g., Graebner 2004; Graebner and Eisenhardt 2004). Graebner (2004) shows that the effect of autonomy on acquisition success depends on the acquired firm’s management: autonomy enhances acquisition success when the acquired firm’s managers take an active role during the integration process, whereas it impedes value creation if managers remain passive. While previous studies have mentioned the importance of considering HRM aspects in M&A task integration—such as staffing needs and turnover concerns (Chaudhuri and Tabrizi 1999), learning efforts needed to create synergies from knowledge transfer (Chaudhuri 2005; Ranft and Lord 2002), and target firm involvement (e.g., Graebner 2004)—we lack a systematic understanding of the strategic role that HRM plays in this aspect of M&A integration.

In contrast to task integration, socio-cultural or human aspects are more difficult to manage, as these relate to employee experiences and attitudes (e.g., Marks and Mirvis 2011). Studies on M&A’s socio-cultural integration have tended to focus on how social identity (e.g., Colman and Lunnan 2011; Hogg and Terry 2000; Giessner et al. Forthcoming), culture (e.g., Stahl and Voigt 2008; Weber et al. 2009, 2011), and organizational sensemaking (e.g., Vaara 2002; Riad and Vaara 2011; Riad et al. 2012) impact employee experiences and reactions during M&A integration.

Studies focusing on social identity issues in M&A integration build on the notion that employees are more positively inclined to their own social group or ‘in-group’, while the acquisition partner is seen as a less attractive ‘out-group’ (e.g., Hogg and Terry 2000). This can lead to ‘us versus them’ thinking, which can impede M&A integration by causing resistance to collaboration and antipathy towards the members of the partner firm, particularly when organizational members perceive that their current identity is threatened (e.g., Giessner et al. Forthcoming; Ullrich et al. 2005; Van Knippenberg et al. 2002). However, recent studies have shown that identity threats can also lead to unexpected value creation by pushing acquired firm members to contribute their knowledge and skills to the acquiring firm in order to preserve and legitimize the acquired firm’s existing identity (Colman and Lunnan 2011). While studies taking a social identity perspective have highlighted important employee reactions caused by identity changes, the M&A literature lacks studies that discuss how these employee reactions can be managed using concrete HRM practices.

Concerning cultural issues, several studies indicate that cultural differences can impede M&A integration effectiveness by causing social conflict (e.g., Stahl and Voigt 2008) and cultural clashes (Weber and Tarba 2011). Furthermore, Weber et al. (2009, 2011) develop propositions about how the acquiring firm’s national culture impacts the appropriateness of task integration approaches described by Haspeslagh and Jemison (1991). They argue that acquiring firms need to modify the ‘ideal’ strategic integration approach to suit their own cultural style in order to bring about successful integration. While these propositions remain untested, a number of empirical studies show that the acquiring firm’s integration approaches do indeed vary based on the acquiring firm’s nationality (e.g., Calori et al. 1994; Child et al. 2000; Lubatkin et al. 1998). While a few studies have discussed the HRM practices that can mitigate problems caused by cultural differences—such as cultural due diligence (Harding and Rouse 2007) and deep-level cultural integration (Schweiger and Goulet 2005)—we lack a systematic understanding of the role of HRM in managing cultural issues.

The organizational sensemaking stream represents the most recent perspective on human integration. It represents a more critical perspective that is concerned with how individuals make sense of M&As. Many researchers have used discourse analysis in order to understand how individuals make sense of acquisition events (e.g., Riad 2005; Vaara 2002). This stream of research has aimed to provide a richer picture of the M&A integration process by showing how individuals socially construct meanings about M&A events. For instance, Riad (2007) examined how individuals constructed notions of ‘organizational culture’ to make sense of a merger and to provide (de)legitimacy for different integration issues. However, while the studies in this stream help us understand how individuals make sense of M&A processes, we lack studies that analyze how HRM practices can influence employee sensemaking.

Taken together, individual studies in each of the research streams discussed above (resource-based view; social identity view; cultural view; and organizational sensemaking view) have touched upon the topic of HRM. However, as a whole, these studies have tended to be fragmented, focusing either on the more strategic task side of M&A integration or on softer human aspects related to culture, social identity, or sensemaking. In order to provide a systematic and comprehensive view of the role HRM plays in M&A integration, we proceed to review HRM-related studies in each of these four research streams.

The roles of HRM in M&As

In this section, we review research that explains the role HRM practices can and do play in M&A integration processes, based on the four major theoretical frameworks outlined above. These theoretical frameworks are directed to distinct mechanisms in which HRM may be used as a strategic means to manage M&A integration. By looking at different theoretical frameworks, we encourage a pluralistic view on the function of HRM in M&As.

Resource-based view—enabling human capital to contribute to M&A success

The resource-based view (RBV) asserts that an organization’s competitive advantage lies within the valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable resources at its disposal (Barney 1991). These resources can reside in ‘physical capital’, such as technology and locations, or ‘organizational capital’, including internal structures, processes, and procedures. The organization’s most precious resource, however, is arguably its ability to acquire and apply knowledge in order to get the best out of its physical and organizational capital, a capability that is inherent to the organization’s ‘human capital’, or the knowledge, skills, and abilities possessed by its employees (Nordhaug and Gronhaug 1994; Penrose 1959; Prahalad and Hamel 1990).

The use of M&As to gain a competitive advantage through organizational resources appears in the earliest conceptions of the RBV (see Wernerfelt 1984). In line with this perspective, M&As are now widely viewed as a way for organizations to gain new markets, master new technologies, and gain operational efficiencies, both within and across borders. M&A is also increasingly used as a means to enhance the organization’s human resource capabilities, particularly in knowledge-based organizations (Lin et al. 2006). Achieving a competitive advantage though M&As is a challenge, however, as many M&A initiatives fail to produce the intended results (Cartwright and Schoenberg 2006; Rees and Edwards 2009). On the other hand, empirical research indicates that combined organizations with high levels of human capital perform better than other merged organizations, which is likely due to their superior capability for inter-organizational learning and knowledge integration (Lin et al. 2006). Research also indicates that M&As are most successful when human capital issues resulting from the merger activity are managed effectively (Nikandrou and Papalexandris 2007; Schuler and Jackson 2001). As such, the role of HRM in facilitating M&A success by enabling human capital advantage is a topic about which there has been considerable discourse.

According to strategic HRM scholars, the primary role of HRM is to ‘deliver “added-value” through the strategic development of the organization’s rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable internal resources embodied—literally—in its staff’ (Boselie et al. 2005: 71). Thus, building the organization’s human capital and influencing the kind of employee behavior that constitutes a competitive advantage is a primary goal of HRM (Boxall and Steeneveld, 1999: 445). In M&As, in particular, HRM is shown to play a critical role in developing human capital and motivating the employee behaviors that are needed for M&A success. For example, training and development practices that prepare employees to respond effectively to job and technology changes imposed by M&A activity are indicated to differentiate top-performing merged organizations from their less effective counterparts (Nikandrou and Papalexandris 2007). Training can also be used to foster the self-awareness and cultural sensitivity that are necessary for successful integration of cross-national M&As (Harper and Cormeraie 1995).

HRM practices that are used to acquire and retain human capital resources, especially those ‘exceptional human talent[s], latent with productive possibilities’ (Boxall 1996: 81), are also necessary in M&As. High turnover rates plague many M&As, requiring sufficient selection procedures to be in place to fill important gaps (Nikandrou and Papalexandris 2007). Financial incentives and other transactional benefits could also be necessary to retain key employees, especially in the acquired organization (Schuler and Jackson 2001), although empirical findings of a positive relationship between the use of financial incentives and M&A success are inconsistent (see Nikandrou and Papalexandris 2007). Further, how selection and retention incentives are used will differ depending on the M&A strategy (Aguilera and Dencker 2004). While some M&As seek to create human capital synergies, others are aimed at reducing human capital overcapacity. In overcapacity M&As, HRM initiatives such as outplacement programs become more critical (Aguilera and Dencker 2004). In particular, programs that help individuals become more employable in the external job market could enable voluntary resignations and reduce negative feelings toward organizational change and dismissal (Baruch 2001; De Cuyper et al. 2008). However, even when human capital reduction is not the primary M&A strategy, layoffs in M&As are common, and the threat of redundancy and job insecurity can be very disruptive if these career concerns are not adequately addressed (Lupina-Wegener 2013; Nikandrou and Papalexandris 2007). Thus, the existence of career opportunities in the internal labor market and career management initiatives are necessary to improve employees’ support for M&A initiatives as well as their retention (Appelbaum et al. 2002; Bourantas and Nikandrou 1998). Indeed, research indicates that providing internal career opportunities is a mark of top-performing M&As (Nikandrou and Papalexandris 2007).

Finally, HRM processes that facilitate knowledge sharing and transfer are necessary in order to realize the synergies sought in merging human capital (Aguilera and Dencker 2004; Ranft 2006; Schuler and Jackson 2001) while minimizing conflict between the combining groups (Weber and Fried 2011). Designing integration work around teams can encourage knowledge sharing by giving employees from each of the combining organizations the opportunity to work together (Cabrera and Cabrera 2007). Empirical research supports the proposition that the creation of integration teams across key areas of business, and the selection of an integration manager to oversee this activity, is often found in organizations that enjoy M&A success (Schuler and Jackson 2001). Formalized socialization programs also provide fora in which knowledge can be shared, while also facilitating the creation of shared norms that are important for successful M&A integration (Aguilera et al. 2006; Cabrera and Cabrera 2007). On the other hand, HRM practices aimed at appraising and rewarding knowledge sharing, while often found in successful mergers (Schuler and Jackson 2001), should be used with caution. Financial rewards in particular could be perceived as controlling, decreasing employees’ intrinsic motivation for engaging in knowledge-sharing behavior (Gagné and Deci 2005). Offering rewards that are low in salience could signal to employees that knowledge sharing is valued, without appearing to be controlling (Cabrera and Cabrera 2007). Still, research extending beyond the M&A domain indicates that incentives that are provided based on group or organizational results, when coupled with internal labor markets, team building, and developmental performance appraisals (i.e., ‘commitment-based HRM practices’), are better suited to facilitate knowledge exchange and application, as they create a social climate that emphasizes trust and cooperation (Collins and Smith 2006).

To summarize, the RBV provides a strategic perspective in explaining why organizations engage in M&A activity and utilize HRM practices to enable M&A success. However, while the above discussion indicates that there are some universal ‘best practices’ that can be applied to manage M&A integration effectively, the relationships between these practices and M&A success are not always consistent. Much of the extant research investigating the link between human capital-enhancing HRM practices and M&A success has been conducted in a single country or has made certain assumptions about the merger strategy. Research suggests, however, that both merger strategy and national culture could impact the effectiveness of certain HRM practices in generating human capital synergies and M&A performance (Aguilera and Dencker 2004; Weber and Fried 2011; Weber and Tarba 2010). Future empirical research that accounts for the interactions between HRM initiatives, M&A strategy, and national culture is therefore needed to improve our understanding of these contingencies.

Social identity theory—facilitating post-acquisition identification

M&As viewed through the lens of social identity theory draw attention to the fact that M&A success requires employees to accept a new ‘post-acquisition identity’ and that certain features of social context facilitate the internalization of the newly combined organization’s values and goals into employees’ self-concept. Social identity theory describes individuals as social beings whose self-concepts are influenced by the social groups to which they belong (Tajfel and Turner 1986), such as a work organization (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Hogg and Terry 2000). Identification with a favorable group can enhance an individual’s sense of self-worth (Brown 2000). When a threat to a group’s social identity is perceived, however, individuals are likely to try to protect their group identity in order to maintain their positive self-concept (Tajfel et al. 1971).

Perceived changes in organizational identity due to a merger (i.e., a low sense of continuity; see Rousseau 1989) are known to elicit feelings of a threatened social identity among employees (Bartels et al. 2006; Giessner 2011; Ullrich et al. 2005). This threat has been shown to trigger anxiety and stress in individuals (Buono and Bowditch 1989; Cartwright and Cooper 1993), change resistance (Jemison and Sitkin 1986), and generate organizational conflict (Marks and Mirvis 1985; Olie 2005), all of which can negatively impact post-acquisition identification. Given that the two combining entities are usually unequal in terms of their status, it is often the case that the employees from at least one merger partner experience a discontinuity of their identity (Giessner et al. 2006). It is recognized that employees from organizations with higher statuses are prone to adopt an attitude of superiority and treat employees from the lower-status organization as inferior (see Hambrick and Cannella 1993; Jemison and Sitkin 1986), because they might feel threatened that the low-status organization’s reputation will drag down their status (Hornsey et al. 2003). In contrast, employees of the low-status organization are most often dominated and feel that their position within the organization is less legitimate (Giessner et al. 2012). Feelings of social identity threat and distrust may be amplified by national cultural stereotyping and xenophobia in international M&As (Krug and Nigh 2001; van Knippenberg et al. 2002).

However, organizations that manage to have employees with stronger post-acquisition identification have been shown to increase job satisfaction (Terry et al. 2001; Van Dick et al. 2004), organizational citizenship behavior (Lipponen et al. 2004; Van Dick et al. 2004), and organizational commitment (Terry et al. 2001), as well as reduce turnover intentions (Van Dick et al. 2004). Pre-acquisition identification (Bartels et al. 2006; van Knippenberg et al. 2002), high group status, and inter-group permeability (Terry et al. 2001) have been shown to impact post-acquisition identification positively. As mentioned above, a sense of continuity can increase post-acquisition identification. However, as some employees are likely to experience a discontinuity of their identity (Giessner et al. 2006), researchers have also focused on further antecedents. A qualitative study by Ullrich et al. (2005) on mid-level managers during a large industrial merger found that some of the managers seemed to identify with the merged organization even when they perceived an observable change in social identity. What motivated them was a clear direction for the future and an outline of how to get there. Ullrich et al. termed this ‘projected continuity’. Further research seemed to confirm this by showing that perceived utility or necessity of the merger can increase post-acquisition identification (Bartels et al. 2006; Lupina-Wegener et al. 2014). This provides a potential way for HRM communication efforts to increase post-acquisition identification for those employees experiencing a discontinuity of their observable identity (Giessner 2011). Thus, these findings indicate that communication efforts aimed at influencing employees’ perceptions of the continuity of their identity, and the necessity and utility of the merger for the future of the organization, are important for eliciting post-acquisition identification.

In addition, perceptions that the distribution of resources and outcomes during the M&A process (i.e., distributive justice) are fair, as well as the practices used to facilitate the integration (i.e., procedural justice), represent central HRM efforts that are needed to increase and maintain post-acquisition identification during the M&A integration process (Lipponen et al., 2004; Monin et al. 2013; see Giessner et al. Forthcoming for a review). Such indications resonate with the research of Bowen and Ostroff (2004), who argue that the perceived relevance and fairness of HRM initiatives are critical for creating a work climate that influences desired employee attitudes and behavior. Bowen and Ostroff’s assertion builds on the assumption that perceived relevance promotes the internalization of externally sanctioned behavior into one’s self-concept. Perceived relevance is said to be fostered by the prestige and ability of an influencing agent (e.g., the M&A integration manager) to provide expert knowledge, allocate resources, or apply sanctions (Bowen and Ostroff 2004). The fairness element of Bowen and Ostroff’s model builds on the principles of organizational justice and research that links various justice perceptions to positive employee outcomes (see Colquitt et al. 2001 for a meta-analytic review of various justice perceptions and their correlates). This research generally indicates that being transparent about the rules of reward distributions and involving employees in decision-making processes can foster fairness perceptions (see also Citera and Rentsch 1993). A recent meta-analysis indicates that justice perceptions induce positive employee outcomes by fostering affective organizational commitment and other characteristic features of trust-based social exchange relationships (Colquitt et al. 2013). Organizational commitment is strongly related to the construct of organizational identification (Riketta 2005). Thus, there is considerable support for the suggestion that fairness perceptions could relate directly to identification with the merged organization and, in turn, provide positive post-acquisition outcomes (Lipponen et al. 2004; Edwards and Edwards 2012).

Acculturation—managing post-acquisition organizational culture

Organizational culture refers to a symbolic set of values, beliefs, and assumptions that are held by organizational members and guide the way in which they, and in aggregate the organization, operates (Denison 1996). While efforts to manage the organizational culture during the M&A process may concern the softer, human side of M&A integration, organizational culture can also be a strategic resource for deriving value and competitive advantage from the post-acquisition organization (Barney 1986). Indeed, research indicates that efforts that are aimed at managing post-acquisition organizational culture are critical to achieving desired M&A outcomes (Schweiger and Goulet 2005; Nahavandi and Malekzadeh 1988). Efforts aimed at hindering culture clashes between the combining entities are particularly important, as clashes are shown to negatively impact the realization of strategic M&A objectives (Cartwright and Price 2003; Very et al. 1996), effectiveness of system integration (Weber and Pliskin 1996), and post-acquisition stock price performance (Chatterjee et al. 1992). Despite its importance, however, companies do not often set a high priority on post-acquisition organizational culture management (Marks and Mirvis 2011).

Managing a post-acquisition organizational culture is not necessarily about creating a new, cohesive organizational culture (Seo and Hill 2005). In fact, four approaches to acculturation, referring to the cultural changes induced by one group or both, resulting in interactions between the two combining organizational cultures, have been identified (Marks and Mirvis 2011). ‘Cultural transformation’ involves the abandonment of previously held cultures and the adoption of new values and norms (Marks and Mirvis 2011). On the other hand, ‘cultural pluralism’ is concerned with the coexistence of cultures in the combining organizations and requires no or minimal culture changes (Marks and Mirvis 2011), ‘cultural integration’ involves blending together the current organizational cultures (Berry 1983), and ‘cultural assimilation’ refers to a unilateral process by which one culture absorbs the other (Nahavandi and Malekzadeh 1988).

There are two perspectives in the current literature concerning M&A culture management. On the one hand, scholars who value cultural differences believe that a variety of people and practices may facilitate innovative idea generation and implementation in organizations (Cox 1993). Further, the unique capabilities embedded in different organizational cultures create the positive conflicts needed for synergies and learning (Vermeulen and Barkema 2001), which, in turn, break down rigidities in the combining entities to enrich market and management knowledge (Schreyögg 2005; Olie and Verwaal 2004). Indeed, evidence from M&A research indicates that differences in style and practices can be positively related to post-M&A performance (Vermeulen 2005), sales growth (Morosini et al. 1998), reduced employee resistance (Larsson and Finkelstein 1999), creative problem solving, innovation (Mirvis and Marks 2003), and increased synergies (Weber et al. 1996). Another line of M&A research, however, looks at the ‘dark side’ of organizational culture differences. Scholars in this area suggest that the differences between two combining entities can lead to ethnocentrism, stereotyping, and domination of the higher-status group over the lower-status group (Sales and Mirvis 1984).

It is recognized that HRM has a role in facilitating the different approaches towards M&A acculturation (Lakshman 2011). The HR function can, for instance, help to map out potential cultural gaps between the two combining organizations (Marks and Mirvis 2011), design activities for social integration (Ranft and Lord 2002), manage the expectations of the two combining organizations to reduce acculturative stress (Marks 2003), create a safe environment for venting stress (Marks 2003), and coach leaders to align their model behaviors with the desired culture (Chatman and Cha 2003). The involvement of HRM in regards to culture management is vital to M&A success, not only in the implementation stage but also in the planning stage, when integration strategies are to be decided (Marks and Mirvis 2011).

Organization sensemaking—setting expectations via communication

Organizational sensemaking refers to a process of social construction in which organizational members interpret and explain what occurs in the environment in and through discursive interactions with others (Maitlis 2005). Sensemaking is a critical organizational activity (Weick 2005), particularly in ambiguous work contexts where people are thrust into unfamiliar roles and task settings (Weick 1993). Thus, it is understandable that sensemaking is an important activity to foster in the context of M&A integration.

The process of comparing M&A integration practices versus expectations could trigger sensemaking processes. Expectations are believed to be a directive element for sensemaking (Weick 2005). Employees constantly scan their environment, seeking information to help them form comparative judgments (Vidyarthi et al. 2010). The subsequent process of confirming one’s expectations, which are grounded in one’s own beliefs, versus what is interpreted from cues in the environment, is considered to be important for driving individual judgments of the situation and, in turn, behavior with regards to dealing with these situations (Weick 2005). Thus, the perception of M&A integration practices should elicit a comparison of perceived M&A experiences versus expectations (Oliver et al. 1994). The extent to which these expectations are met determines the perceived disconfirmation experience (Oliver 1977) in that a gap arises when the expectations are ‘better than’ or ‘worse than’ perceived experiences. Experiences that fall short of expectation (negative disconfirmation) foster disappointment and reduce satisfaction (Irving and Montes 2009).

Based on the above theory, setting expectations should be a crucial element in influencing employees’ positive judgments of M&A integration. To this end, communication efforts aimed at conveying the strategic direction of the M&A to employees, and correcting any misconceptions, are particularly valuable. It is well recognized that effective internal organizational communication is important to achieve M&A success (Ager 2011; Armenakis and Bedeian 1999; Schweiger and Denisi 1991). Communication regarding the evolving stages and changes associated with M&As not only helps employees to form expectations of the M&A process (Hubbard and Purcell 2001), but also provides them with assurance and the ability to make informed choices on how to deal with this challenging situation (Schweiger and Denisi 1991; Seo and Hill 2005)

The involvement of the HR function in disseminating relevant communication regarding the M&A is vital not only in the implementation stage, but throughout the M&A process. Prior to the M&A, HR could inform employees about the practical plan of the M&A, future direction, and potential cultural changes associated with the new combined entity (Schweiger and Denisi 1991). Post-acquisition, HR can inform employees about the integration status and strategic direction (Jimmieson and White 2011). Various communication media can be used to share up-to-date information about what is happening with the M&A, including face-to-face communication, company newsletters, and video displays. A study by Schweiger and Denisi (1991) demonstrates that firms that provide a realistic M&A review program, in which employees are informed using different means of communication, enjoy greater employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment and reduced job uncertainty. Other evidence shows that using communication mechanisms enables employees to raise their concerns and leads to successful post-acquisition integration (Nikandrou and Papalexandris 2007; Papadakis 2005). In addition, employees are more likely to perceive a positive atmosphere about the handling of differences in organizational culture (Appelbaum et al. 2002) and the successful management of the integration process (Hubbard 2001).

Critical contingency factors in M&A HRM implementation

In the previous section, we reviewed how different HRM practices may facilitate integration processes in M&As using four major theoretical frameworks. Clearly, HRM plays an important role in managing M&A integration, yet the relationship between HRM and M&A performance is not straightforward (Lin et al. 2006). It is thus important to look at the conditions under which HRM practices are likely to be more or less helpful. In this section, therefore, we review studies that have investigated the conditions under which the use of HRM in M&As has yielded more or less successful results.

HR centrality

The extent to which the HR function is involved in M&A strategy formation, referred to as HR centrality, is considered to be a primary condition that is necessary for HR to act as an intrinsic part of the integration team (Bramson 2000). There are two dimensions that define HR centrality: the degree of involvement in the firm’s strategy; and the existence of an HR strategy (Becker and Gerhart 1996). HR centrality is high when HR managers take part in the firm’s strategy formulation as members of top management teams (Nikandrou and Papalexandris 2007). This enables HR managers to have the most up-to-date information about the firm’s business situation and to evaluate whether and how the firm’s current human capital may serve strategic goals (Bramson 2000), both of which are necessary for HR strategy formation.

HR centrality is particularly important in M&As as HR managers can serve as strategic partners in the search for and evaluation of potential M&A partners (Galpin and Herndon 2000; Schuler and Jackson 2001). In this strategic role, HR managers also help the organization to align their human resource capabilities with business needs and trends (Brooks and Dawes 1999). Later in the M&A process, HR managers can help firms to evaluate the compatibility of corporate cultures and, more importantly, to analyze alternative integration options (Bramson 2000).

HR power

Previous studies have demonstrated that HR strategy formulization is positively related to firm (Tregaskis 1997) and individual performance (Weber and Drori 2011; Marmenout 2011). Nevertheless, its effectiveness is contingent. A study by Lupina-Wegner (2013) revealed that the strength of HR power, which refers to the quality of HR strategy development and its execution effectiveness, may moderate the way in which employees of the combining organizations respond to M&A integration. HR power tends to be lower in international M&As, when there is a less clear understanding of the local context. Detrimental consequences of HR integration, such as perceived uncertainty and reduced autonomy, may emerge where there is low HR power. Supporting this, Smith et al. (2013) argue that the intended objective of an HR integration strategy of bringing people together may not necessarily lead to positive employee responses from the two combining firms when they see themselves as different from each other.

Ambiguity

In addition, HR initiatives set by management during M&As might not be evaluated as intended by employees (Khilji and Wang 2006; Risberg 1997). Previous studies provide evidence of discrepancies between the HR practices perceived by managers versus employees (Edgar and Geare 2005; Khilji and Wang 2006). Communication is considered an important means to spell out the meaning of HR practices and minimize potential misconceptions (Den Hartog et al. 2013). For instance, if organizations can get employees to see how the intended HR practices address their concerns, it is more likely that they may respond positively to M&A activity (Lupina-Wegener 2013; Giessner 2011; Ullrich et al. 2005).

Further, giving employees a meaningful rationale and acknowledging conflicting feelings regarding the M&A could foster employee acceptance of organizational change (Gagné et al. 2000). Self-determination theory and research support the proposal that the internalization of externally sanctioned activities, such as those required by M&As, occurs when individuals are placed in an ‘autonomy-supportive’ social context where they are provided with a meaningful rationale for engaging in the activity, they perceive that their feelings concerning the activity are acknowledged, and they have discretion with regards to when or how to carry it out (Deci et al. 1994).

Conclusions

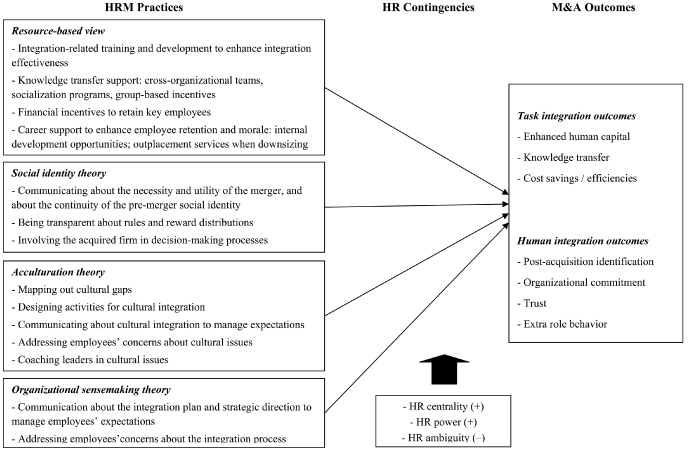

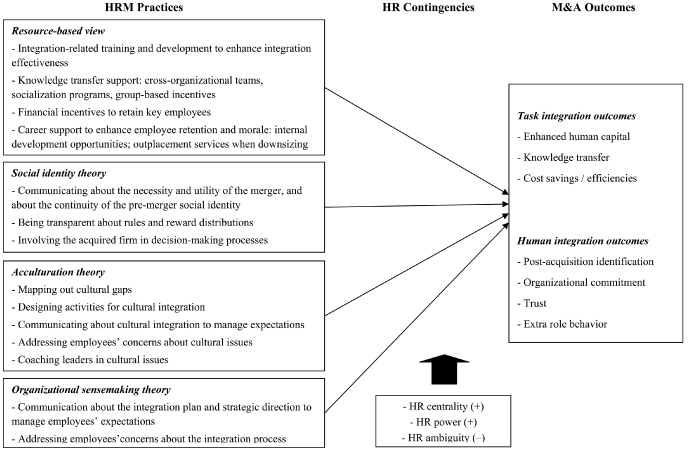

While previous studies have touched upon HRM in M&As, research on this topic has been scarce, and we have lacked a systematic overview of what role HRM plays in M&A integration. We have reviewed four theoretical streams (resource-based view; social identity view; cultural view; organizational sensemaking view) in order to provide a more comprehensive overview of the role of HRM practices in M&A integration. We have also identified important contingency factors that are likely to impact the success of HRM practices in M&As. Overall, previous research provides clear evidence that the involvement of HRM in M&As at both the operational and strategic levels helps organizations to integrate and allocate resources to achieve better organizational and employee outcomes. Furthermore, our review shows that HRM plays a multifaceted role in facilitating M&A integration, and that the centrality and power of HR managers and the ambiguity of intended HRM efforts constitute critical contingencies that impact the extent to which HRM practices are likely to contribute to successful M&A integration. Based on the review, we outline managerial recommendations concerning the role of HRM in M&As. These recommendations, as well as the conceptual model, are depicted in Figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1 The role of HRM practices in M&A integration

Strategic human capital management is increasingly important to gain competitive advantage in today’s knowledge-based economy. A growing number of companies are using M&A as a strategic means to acquire unique human capital (e.g., Lin et al. 2006). Thus, organizations are advised to involve HR during both strategic M&A planning and implementation. In practice, HR managers should consider providing integration-related training and development (Nikandrou and Papalexandris 2007) to enhance integration effectiveness and make the most of the acquired human capital. Furthermore, cross-organizational teams (Cabrera and Cabrera 2007), socialization (e.g., Aguilera et al. 2006), and group-based knowledge transfer incentives (Collins and Smith 2006) can be effective means for enhancing knowledge transfer between the combined firms. HR managers can also address staffing needs and retention issues by providing compelling incentives to key employees. While findings on the impact of financial incentives have been mixed, our review suggests that enhancing employees’ perceived career opportunities may also be effective for motivating them to stay with the merged firm (e.g., Nikandrou and Papalexandris 2007).

Organizations should also pay attention to softer, human-related factors that may influence the success of post-acquisition integration. Underestimating the potential effect of social identification may jeopardize the intended outcomes of the M&A. In the integration process, HR should function as the anchor that mitigates potential identity threats between the two combining organizations, and design action plans to tackle these threats to minimize potential negative impacts of ‘us versus them’ thinking. Communicating about the necessity and the benefits of the acquisition can increase the attractiveness of the merger and, hence, employee integration (Giessner 2011). Furthermore, communicating about plans to let the pre-acquisition firms’ identities continue may dampen fears related to identity loss (e.g., Ullrich et al. 2005). Because distributive and procedural justice can influence employee identification and commitment (e.g., Lipponen et al. 2004), it is important that the acquiring firm is transparent concerning the distribution of key positions and rewards, and that the acquired firm is included in the decision-making process.

In addition, HR should provide strategic guidance to organizations and managers on how they can reach a desirable cultural end state. More specifically, HR managers should help to identify and map out cultural gaps (Marks and Mirvis 2011). Based on this, HR managers can design integration activities that facilitate cultural integration, such as seminars where the partner firms’ cultures are discussed, including which parts of their cultures should be preserved and which should be changed (e.g., Marks and Mirvis 2011; Schweiger and Goulet 2005). Informal socialization events and opportunities to get together outside of the work environment can also help employees understand the partner firm’s unwritten norms and beliefs (e.g., Schweiger and Goulet 2005). It is also important that HR managers communicate the meaning of the M&A and desired post-acquisition organizational culture to employees, in order to manage expectations and reduce anxiety related to cultural change (Marks 2003). Communication should run both ways, though, as employees’ concerns need to be heeded and addressed (Marks 2003). The HR function can play an important role in facilitating both types of communication and in involving employees in the cultural change process. However, employees often turn to their direct supervisors for information and support. Therefore, it is critical that leaders receive training and coaching in how to deal with potential cross-cultural issues (Chatman and Cha 2003).

During integration, organizational members create their own meanings of the acquisition, its aims, and potential outcomes. It can be difficult to impact how employees make sense of the acquisition, as organizational sensemaking is influenced by personal political motives (Vaara 2002), and information presented by the merging firms’ managers (Riad 2005, 2007; Vaara 2002), the media (Riad and Vaara 2011; Riad et al. 2012), and peers (Marmenout 2011). Nevertheless, the HR function can try to help employees make sense of the acquisition by engaging in frequent two-way communication concerning the acquisition goals, plans, and processes, as well as changes along the way (e.g., Hubbard and Purcell 2001).

HR has the potential to play an important and multifaceted role in M&A integration. However, in practice, this is easier said than done, as the implementation of HR practices in M&As is complex and contingent upon the overall role of HR in the merging firms. In order to add strategic value, it is crucial that the HR function occupies a central position in the acquiring firm prior to the acquisition (e.g., Bramson 2000). HR is likely to have a stronger impact on M&A outcomes when HR’s power is high (Weber and Drori 2011)—that is, when HR practices and processes are well developed, formalized, and clearly communicated. In contrast, ambiguity and different interpretations (Risberg 1997) of HR practices can make their implementation harder and the outcomes less predictable. HR managers should therefore pay attention to communicating to employees about the intended HR strategy for integrating the merging firms.

In addition to the managerial recommendations discussed above, this study has important theoretical implications. Depending on the chosen theoretical perspective, it is possible to identify distinct, critical HRM practices that are likely to aid M&A integration. Taken together, the four theoretical perspectives applied in this review show that HRM plays a multifaceted role in M&As. The HR function plays an important role in achieving greater strategic task integration by optimizing the use of human capital. In addition, the HR function can act as a bridge between managers and employees and between the merging organizations, to help manage the softer human side of integration by providing information and support. This highlights the strategic and socio-cultural role of HRM, and points to the need for combining several theoretical perspectives in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study. In this review, we also identified critical contingencies that are likely to impact the role of HRM in M&As. How much value HRM can add to M&As is likely to depend on how central, powerful, and clear (or ambiguous) the HR function and its activities are from the outset. We therefore call for future research to examine the impact of these contingencies on the role of HRM in M&As.

While this study has provided a systematic and comprehensive review of the role of HRM in M&A integration based on four theoretical research streams, it has not elaborated on the inter-linkages between these streams. Such links should be explored in future research. For instance, social identities (Zaheer et al. 1998) and employee sensemaking (Riad 2005; Vaara 2002) are often influenced by national and organizational cultures. Therefore, cultural changes brought about by the acquisition are likely to trigger identity and sensemaking processes among organizational members. It would therefore be interesting to examine how and when HR managers should get involved in order to help organizational members navigate through these softer integration issues. In addition, there may be a balance between HR managers having a strategic task-oriented role in M&A integration versus accounting for more human aspects. In order to be seen as strategically relevant, HR managers must understand the needs of the business and the interests of top-level managers. However, this strategic focus may steer HR away from softer employee needs ‘on the ground’. Future studies could examine whether such trade-offs exist, and how the degree of HR specialization (versus having a broader role) impacts M&A integration success in different types of acquisitions. Finally, many empirical studies reviewed in this chapter are based on qualitative case studies that have taken a specific and narrow focus on certain HR aspects. Future studies should draw on larger empirical samples in order to test the impact of the outlined HRM practices on M&A outcomes. It is also important to examine under which contingencies different HRM practices are likely to be more or less useful. Finally, while we have suggested three critical contingencies (HR centrality, HR power, HRM practice ambiguity), future studies could consider other moderators, such as acquisition characteristics (e.g., acquisition aims, acquisition experience, previous relationship between the merging firms) and industry characteristics (e.g., market turbulence).

To conclude, we set out to provide a systematic and comprehensive review of the role of HRM in M&A integration. We reviewed four theoretical research streams (resource-based view; social identity view; cultural view; organizational sensemaking view), and identified critical contingency factors that may impact the success of implementing HRM practices in M&As. We hope that this review has provided inspiration for future research that aims to uncover how HR can add value in M&As.

References

Ager, D., ‘The emotional impact and behavioral consequences of post-M&Amp;A integration: an ethnographic case study in the software industry’. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 40, 2011, 199–230.

Aguilera, R.V. and J.C. Dencker, ‘The role of human resource management in cross-border mergers and acquisitions’. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 15, 2004, 1355–1370.

Aguilera, R.V., J.C. Dencker and Z.Y. Yalabik, ‘Institutions and organizational socialization: connectivity in the human side of post-merger and acquisition integration’. In A.Y. Lewin, S.T. Cavusgil, T.M. Holt and D.A. Griffith (Eds.), Thought leadership in advancing international business research, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, pp. 153–189.

Almor, T., S.Y. Tarba and H. Benjamini, ‘Unmasking integration challenges: the case of Biogal’s acquisition by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries’. International Studies of Management and Organization, 39, 2009, 33–53.

Appelbaum, S.H., A. Heather and B.T. Sharipo, ‘Career management in information technology: a case study’. Career Development International, 7, 2002, 142–158.

Armenakis, A.A. and A.G. Bedeian, ‘Organizational change: a review of theory and research in the 1990s’. Journal of Management, 25, 1999, 293–315.

Ashforth, B.E. and F. Mael, ‘Social identity theory and the organization’. Academy of Management Review, 14, 1989, 20–39.

Barney, J.B., ‘Organizational culture: can it be a source of competitive advantage?’ Academy of Management Review, 11, 1986, 656–665.

Barney, J.B., ‘Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage’. Journal of Management, 17, 1991, 99.

Bartels, J.D., R. Jong, M. Jong and A. Pruyn, ‘Organizational identification during a merger: determinants of employees’ expected identification with the new organization’. British Journal of Management, 17, 2006, 49–67.

Baruch, Y., ‘Employability: a substitute for loyalty’. Human Resource Development International, 4, 2001, 543–566.

Becker, B. and B. Gerhart, ‘The impact of human resource management on organizational performance: progress and prospects’. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 1996, 779–801.

Berry, J.W., ‘Acculturation: a comparative analysis of alternative forms’. Perspectives in Immigrant and Minority Education, 5, 1983, 66–77.

Birkinshaw, J., H. Bresman and L. Håkanson, ‘Managing the post-acquisition integration process: how the human integration and task integration processes interact to foster value creation’. Journal of Management Studies, 37, 2000, 395–425.

Boselie, P., G. Dietz and C. Boon, ‘Commonalities and contradictions in HRM and performance research’. Human Resource Management Journal, 15, 2005, 67–94.

Bourantas, D. and I. Nikandrou, ‘Modelling post-acquisition employee behavior: typology and determining factors’. Employee Relations, 20, 1998, 73–91.

Bowen, D.E. and C. Ostroff, ‘Understanding HRM–firm performance linkages: the role of the “strength” of the HRM system’. Academy of Management Review, 29, 2004, 203–221.

Boxall, P., ‘The strategic HRM Debate and the resource-based view of the firm’. Human Resource Management Journal, 6, 1996, 59–75.

Boxall, P. and M. Steeneveld, ‘Human resource strategy and competitive advantage: a longitudinal study of engineering consultancies’. Journal of Management Studies, 36, 1999, 443–463.

Bramson, R.N., ‘HR’s role in mergers and acquisitions’. Training and Development, 54, 2000, 59.

Brooks, I. and J. Dawes, ‘Merger as a trigger for cultural change in the retail financial services sector’. Services Industries Journal, 19, 1999, 194–206.

Brown, R., ‘Social identity theory: past achievements, current problems and future challenges’. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30, 2000, 745–778.

Bryson, J., ‘Managing HRM risk in a merger’. Employee Relations, 25, 2003, 14–30.

Buono, A.F., and J.L. Bowditch, The human side of mergers and acquisitions, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1989.

Cabrera, E.F. and A. Cabrera, ‘ Fostering knowledge sharing thorugh people management practices’. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16, 2007, 720–735.

Calori, R., M. Lubatkin and P. Very, ‘Control mechanisms in cross-border acquisitions: an international comparison’. Organization Studies, 15, 1994, 361–379.

Cartwright, S. and C.D. Cooper, ‘The psychological impact of mergers and acquisitions on the individual: a study of building society managers’. Human Relations, 46, 1993, 327–347.

Cartwright, S. and F. Price, ‘Managerial preferences in international merger and acquisition partners revisited: how are they influenced?’ Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions, 2, 2003, 81–95.

Cartwright, S. and R. Schoenberg, ‘Thirty years of mergers and acquisitions research: research advances and future opportunities’. British Journal of Management, 17, 2006, 1–5.

Chatman, J. and S. Cha, ‘Leading by leveraging culture’. California Management Review, 45, 2003, 14.

Chatterjee, S., M. Lubatkin, H. Schweiger, M. David and Y. Weber, ‘Cultural differences and shareholder value: explaining the variability in the performance of related mergers’. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 1992, 319–334.

Chaudhuri, S., ‘Managing human resources to capture capabilities: case studies in high-technology acquisitions’. In G.K. Stahl and M.E. Mendenhall (Eds.), Mergers and acquisitions: managing culture and human resources, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005, pp. 277–301.

Chaudhuri, S. and B. Tabrizi, ‘Capturing the real value in high-tech acquisitions’. Harvard Business Review, 77, 1999, 123–130.

Child, J., D. Faulkner and R. Pitkethly, ‘Foreign direct investment in the UK 1985–1994: the impact on domestic management practice’. Journal of Management Studies, 37, 2000, 141–166.

Citera, M. and J.R. Rentsch, ‘Is there justice in organizational acquisitions? The role of distributive and procedural fairness in corporate acquisitions’. In R. Cropanzano (Ed.), Justice in the workplace: approaching fairness in human resource management, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1993, pp. 211–230.

Collins, C.J. and K.G. Smith, ‘Knowledge exchange and combination: the role of human resource practices in the performance of high-technology firms’. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 2006, 544–560.

Colman, H.L. and R. Lunnan, ‘Organizational identification and serendipitous value creation in post-acquisition integration’. Journal of Management, 37, 2011, 839–860.

Colquitt, J.A., D.E. Conlon, M.J. Wesson, C.O. Porter and K.Y. Ng, ‘Justice at the millennium: a meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research’. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 2001, 425–445.

Colquitt, J.A., B.A. Scott, J.B. Rodell, D.M. Long, C.P. Zapata, D.E. Conlon and M.J. Wesson, ‘Justice at the millennium, a decade later: a meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives’. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98, 2013, 199–236.

Cox, T., Cultural diversity in organizations: theory, research and practice, San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 1993.

Deci, E.L., H. Eghrari, B.C. Patrick and D.R. Leone, ‘Facilitating internalization: the self-determination theory perspective’. Journal of Personality, 62, 1994, 119–142.

Deci, E.L. and R.M. Ryan, ‘The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior’. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 2000, 227–268.

De Cuyper, N., C. Bernhard-Oettel, E. Berntson, H.D. Witte and B. Alarco, ‘Employability and employees’ well-being: mediation by job insecurity’. Applied Psychology, 57, 2008, 488–509.

Den Hartog, D.N., C. Boon, R.M. Verburg and M.A. Croon, ‘HRM, communication, satisfaction, and perceived performance: a cross-level test’. Journal of Management, 39, 2013, 1637–1665.

Denison, D.R., ‘What is the difference between organizational culture and organizational climate? A native’s point of view on a decade of paradigm wars’. Academy of Management Review, 21, 1996, 619–654.

Edgar, F. and A. Geare, ‘HRM practice and employee attitudes: different measures – different results’. Personnel Review, 34, 2005, 534–549.

Edwards, M.R. and T. Edwards, ‘Procedural justice and identification with the acquirer: the moderating effects of job continuity, organisational identity strength and organisational similarity’. Human Resource Management Journal, 22, 2012, 109–128.

Faulkner, D., S. Teerikangas and R.J. Joseph, The handbook of mergers and acquisitions, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Gagné, M. and E.L. Deci, ‘Self-determination theory and work motivation’. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 2005, 331–362.

Gagné, M., R. Koestner and M. Zuckerman ‘Facilitating acceptance of organizational change: the importance of self-determination’. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 2000, 1843–1852.

Galpin, T.J. and M. Herndon, The complete guide to mergers and acquisitions: process tools to support M&Amp;A integration at every level, San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, 2000.

Giessner, S.R., ‘Is the merger necessary? The interactive effect of perceived necessity and sense of continuity on post-merger identification’. Human Relations, 64, 2011, 1079–1098.

Giessner, S.R., K.E. Horton and S.I.W. Humborstad, ‘Identity management during organizational mergers: empirical insights and practical advice’. Social Issues and Policy Review Forthcoming.

Giessner, S.R., T. Viki, S. Otten, D.J. Terry and S. Tauber, ‘The challenge of merging: merger patterns, premerger status, and merger support’. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 2006, 339–352.

Giessner, S.R., J. Ullrich and R. Van Dick, A social identity analysis of mergers and acquisitions, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Gomes, E., D. Angwin, Y. Weber and S.Y. Tarba, ‘Critical success factors through the mergers and acquisitions process: revealing pre- and post-M&Amp;A connections for improved performance’. Thunderbird International Business Review, 55, 2013, 13–36.

Graebner, M.E., ‘Momentum and serendipidity: how acquired firm leaders create value in the integration of technology firms’. Strategic Management Journal, 25, 2004, 751–777.

Graebner, M.E. and K.M. Eisenhardt, ‘The other side of the story: acquisition as courtship and governance as syndicate in entrepreneurial firms’. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49, 2004, 366–403.

Haleblian, J., C.E. Devers, G. McNamara, M.E. Carpenter and R.B. Davison, ‘Taking stock of what we know about mergers and acquisitions: a review and research agenda’. Journal of Management, 35, 2009, 469–502.

Hambrick, D.C. and A.A. Cannella, ‘Relative standing: a framework for understanding departures of acquired executives’. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 1993, 733–762.

Harding, D. and T. Rouse, ‘Human due diligence’. Harvard Business Review, 85, 2007, 124–131.

Harper, J. and S Cormeraie, ‘Mergers, marriages and after: how can training help?’ Journal of European Industrial Training, 19, 1995, 24–29.

Haspeslagh, P. and D.B. Jemison, Managing acquisitions: creating value through corporate renewal, New York: The Free Press, 1991.

Hogan, E.A. and L. Overmyer-Day, ‘The psychology of mergers and acquisitions’. International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 9, 1994, 247–247.

Hogg, M.A. and D.I. Terry, ‘Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts’. Academy of Management Review, 25, 2000, 121–140.

Hornsey, M.J., E. van Leeuwen and W. Van Santen, ‘Dragging down and dragging up: how relative group status affects responses to common fate’. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 7, 2003, 275.

Hubbard, N., Acquisition strategy and implementation, West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2001.

Hubbard, N. and J. Purcell, J. ‘Managing employee expectations during acquisitions’. Human Resource Management Journal, 11, 2001, 17–33.

Irving, P.G. and S.D. Montes, ‘Met expectations: the effects of expected and delivered inducements on employee satisfaction’. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82, 2009, 431–451.

Jemison, D.B. and S.B. Sitkin, ‘Corporate acquisitions: a process perspective’. Academy of Management Review, 11, 1986, 145–163.

Jimmieson, N.L. and K.M White, ‘Predicting employee intentions to support organizational change: an examination of identification processes during a re-brand’. British Journal of Social Psychology, 50, 2011, 331–341.

Khilji, S.E. and X. Wang, ‘“Intended” and “implemented” HRM: the missing linchpin in strategic human resource management research’. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17, 2006, 1171–1189.

King, D.R., D.R. Dalton, C.M. Daily and J.G. Covin, ‘Meta-analyses of post-acquisition performance: indications of unidentified moderators’. Strategic Management Journal, 25, 2004, 187–200.

Krug, J.A. and D. Nigh, ‘Executive perceptions in foreign and domestic acquisitions: an analysis of foreign ownership and its effect on executive fate’. Journal of World Business, 36, 2001, 85–105.

Lakshman, C., ‘Postacquisition cultural integration in mergers & acquisitions: a knowledge-based approach’. Human Resource Management, 50, 2011, 605–623.

Larsson, R. and S. Finkelstein, ‘Integrating strategic, organizational, and human resource perspectives on mergers and acquisitions: a case survey of synergy realization’. Organization Science, 10, 1999, 1–26.

Lin, W., S.C. Hung and P.C. Li, ‘Mergers and acquisitions as a human resource strategy – evidence from US banking firms’. International Journal of Manpower, 27, 2006, 126–142.

Lipponen, J., M.E. Olkkonen and M. Moilanen, ‘Perceived procedural justice and employee responses to an organizational merger’. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 13, 2004, 391–413.

Lubatkin, M., R. Calori, P. Very and J.F. Veiga, ‘Managing mergers across borders: a two-nation exploration of a nationally bound administrative heritage’. Organization Science, 9, 1998, 670–684.

Lupina-Wegener, A.A., ‘Human resource integration in subsidiary mergers and acquisitions: evidence from Poland’. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 26, 2013, 286–304.

Lupina-Wegener, A., F. Drzensky, J. Ullrich and R. Van Dick, ‘Focusing on the bright tomorrow? A longitudinal study of organizational identification and projected continuity in a corporate merger’. British Journal of Social Psychology, 53, 2014, 752–772.

Maitlis, S., ‘The social processes of organizational sensemaking’. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 2005, 21–49.

Marks, M.L., Charging back up the hill: workplace recovery after mergers, acquistions, and downsizing. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003.

Marks, M.L. and P. Mirvis, ‘Merger syndrome: stress and uncertainty’, Mergers and Acquisitions, 1985, 50–55.

Marks, M.L. and P.H. Mirvis, ‘Making mergers and acquisitions work: strategic and psychological preparation’. Academy of Management Executive, 15, 2001, 80–92.

Marks, M.L. and P. H. Mirvis, ‘A framework for the human resources role in managing culture in mergers and acquistions’. Human Resource Management, 50, 2011, 859–877.

Marmenout, K., ‘Peer interaction in mergers: evidence of collective rumination’. Human Resource Management, 50, 2011, 783–808.

Mirvis, P.H. and M.L. Marks, Managing the merger: making it work, Washington, DC: Beard Books, 2003.

Monin, P., N. Noorderhaven, E. Vaara and D. Kroon, ‘Giving sense to and making sense of justice in postmerger integration’. Academy of Management Journal, 56, 2013, 256–284.

Morosini, P., S. Shane and H. Singh, ‘National cultural distance and cross-border acquisition performance’. Journal of International Business Studies, 29, 1998, 137–158.

Nahavandi, A. and A.R. Malekzadeh, ‘Acculturation in mergers and acquisitions’. Academy of Management Review, 13, 1988, 79–90.

Nikandrou, I. and N. Papalexandris, ‘The impact of M&Amp;A experience on strategic HRM practices and organisational effectiveness: evidence from Greek firms’. Human Resource Management Journal, 17, 2007, 155–177.

Nordhaug, O. and K. Gronhaug, ‘Competences as resources in firms’. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 5, 1994, 89–106.

Olie, R., ‘Integration processes in cross-border mergers: lessons learned from Dutch– German mergers’. Mergers and Acquisitions: Managing Culture and Human Resources, 2005, 323–350.

Olie, R. and E. Verwaal, ‘The effects of cultural distance and host country experience on the performance of cross-border acquisitions’. Paper presented at Academy of Management Conference, New Orleans, LA, 2004.

Oliver, R.L., ‘Effect of expectation and disconfirmation on postexposure product evaluations: an alternative interpretation’. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62, 1977, 480.

Oliver, R.L., P.V. Balakrishnan and B. Barry. ‘Outcome satisfaction in negotiation: a test of expectancy disconfirmation’. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 60, 1994, 252–275.

Pablo, A., ‘Determinants of acquisition integration level: a decision-making perspective’. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 1994, 803–836.

Papadakis, V.M., ‘The role of broader context and the communication program in merger and acquisition implementation success’. Management Decision, 43, 2005, 236–255.

Paruchuri, S., A. Nerkar and D.C. Hambrick, ‘Acquisition integration and productivity losses in the technical core: disruption of inventors in acquired companies’. Organization Science, 17, 2006, 545–562.

Penrose, E., The theory of the growth of the firm, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959.

Prahalad, C.K. and G. Hamel, ‘The core competence of the corporation’. Harvard Business Review, 68, 1990, 79–91.

Puranam, P., H. Singh and M. Zollo, ‘Organizing for innovation: managing the coordination–autonomy dilemma in technology acquisitions’. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 2006, 263–280.

Puranam, P. and K. Srikanth, ‘What they know vs. what they do: how acquirers leverage technology acquisitions’. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 2007, 805–825.

Ranft, A.L., ‘Knowledge preservation and transfer during post-acquisition integration’. Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions, 5, 2006, 51–67.

Ranft, A.L. and M.D. Lord, ‘Acquiring new technologies and capabilities: a grounded model of acquisition implementation’. Organization Science, 13, 2002, 420–441.

Rees, C. and T. Edwards, ‘Management strategy and HR in international mergers: choice, constraint and pragmatism’. Human Resource Management Journal, 19, 2009, 24–39.

Riad, S., ‘The power of “organizational culture” as a discursive formation in merger integration’. Organization Studies, 26, 2005, 1529–1554.

Riad, S., ‘Of mergers and cultures: what happened to “shared values and joint assumptions”?’ Journal of Organizational Change Management, 20, 2007, 26–43.

Riad, S. and E. Vaara, ‘Varieties of national metonymy in media accounts of international mergers and acquisitions’. Journal of Management Studies, 48, 2011, 737–771.

Riad, S., E. Vaara and N. Zhang, ‘The intertextual production of international relations in mergers and acquisitions’. Organization Studies, 33, 2012, 121–148.

Riketta, M., ‘Organizational identification: a meta-analysis’. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66, 2005, 358–384.

Risberg, A., ‘Ambiguity and communication in cross-cultural acquisitions’. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 18, 1997, 257–266.

Rousseau, D.M., ‘Psychological and implied contracts in organizations’. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 2, 1989, 121–139.

Sales, A.L. and P.H. Mirvis, ‘When cultures collide: issues in acquisition’. In J.R. Kimberly and R. Quinn (Eds.), Managing Organizational Transitions, Homewood, IL: Irwin, 1984, pp. 107–133.

Sarala, R.M., P. Junni, C.L. Cooper and S.Y. Tarba, ‘A socio-cultural perspective on knowledge transfer in mergers and acquisitions’. Journal of Management Forthcoming.

Schreyögg, G., ‘The role of corporate culture diversity in integrating mergers and acquisitions’. In G. Stahl and M.E. Mendenhall (Eds.), Mergers and acquisitions: managing culture and human resources. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005, pp. 108–126.

Schuler, R.S. and S.E. Jackson, ‘HR issues and activities in mergers and acquisitions’. European Management Journal, 19, 2001, 239–253.

Schweiger, D.M. and A.S. Denisi, ‘Communication with employees following a merger: a longitudinal field experiment’. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 1991, 110–135.

Schweiger, D.M. and P.K. Goulet, ‘Facilitating acquisition integration through deep-level cultural learning interventions: a longitudinal field experiment’. Organization Studies, 26, 2005, 1477–1499.

Schweizer, L., ‘Organizational integration of acquired biotech companies into pharmaceutical companies: the need for a hybrid approach’. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 2005, 1051–1074.

Seo, M.G. and N.H. Hill, ‘Understanding the human side of merger and acquisition: an integrative framework’. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41, 2005, 422–443.

Smith, P., J.V. Da Cunha, A. Giangreco, A. Vasilaki and A. Carugati, ‘The threat of dis-identification for HR practices: an ethnographic study of a merger’. European Management Journal, 31, 2013, 308–321.

Spedale, S., F.A.J. van den Bosch and H.W. Volberda, ‘Preservation and dissolution of the target firm’s embedded ties in acquisitions’. Organization Studies, 28, 2007, 1169–1196.

Stahl, G.K. and A. Voigt, ‘Do cultural differences matter in mergers and acquisitions? A tentative model for examination’. Organization Science, 19, 2008, 160–176.

Tajfel, H., M.G. Billig, R.P. Bundy and C. Flament, ‘Social categorization and intergroup behaviour’. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1, 1971, 149–178.

Tajfel, H. and J.C. Turner, ‘The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour’. In W. G. Austin and S. Worchel (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations, 2nd edn. Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1986, pp. 7–24.

Terry, D.D.J., V.J. Callan and G. Sartori, ‘Employee adjustment to an organizational merger: stress, coping and intergroup differences’. Stress Medicine, 12, 1996, 105–122.

Terry, D.J., C.J. Carey and V.J. Callan, ‘Employee adjustment to an organizational merger: an intergroup perspective’. Personality and Social Psychological Bulletin, 27, 2001, 67–280.

Thanos, I. and V. Papadakis, Unbundling acquisition performance: how do they perform and how can this be measured?, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Tregaskis, O., ‘The role of national context and HR strategy in shaping training and development practice in French and UK organizations’. Organization Studies, 18, 1997, 839–857.

Ullrich, J., J. Wieseke and R.V. Dick, ‘Continuity and change in mergers and acquisitions: a social identity case study of a German industrial merger’. Journal of Management Studies, 42, 2005, 1549–1569.

Vaara, E., ‘On the discursive construction of success–failure in narratives of post-merger integration’. Organization Studies, 23, 2002, 211–243.

Van Dick, R., O. Christ, J. Stellmacher et al., ‘Should I stay or should I go? Explaining turnover intentions with orgainzational identification and job satisfaction’. British Journal of Management, 15, 2004, 351–360.

van Knippenberg, D., B. van Knippenberg, L. Monden and F. de Lima, ‘Organizational identification after a merger: a social identity perspective’. British Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 2002, 233–252.

Vermeulen, F., ‘How acquisitions can revitalize companies’. Sloan Management Review, 46, 2005, 44–51.

Vermeulen, F. and H. Barkema, ‘Learning through acquisitions’. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 2001, 457–476.

Very, P., M. Lubatkin and R. Calori, ‘A cross-national assessment of acculturative stress in recent European mergers’. International Studies of Management and Organization, 26, 1996, 59–86.

Vidyarthi, P.R., R.C. Liden, S. Anand, B. Erdogan and S. Ghosh, ‘ Where do I stand? Examining the effects of leader–member exchange social comparison on employee work behaviors’. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 2010, 849.

Weber, Y. and I. Drori, ‘Integrating organizational and human behavior perspectives on mergers and acquisitions’. International Studies of Management and Organization, 41, 2011, 76–95.

Weber, Y. and Y. Fried, ‘The role of HR practices in managing culture clash during the postmerger integration process’. Human Resource Management, 50, 2011, 565–570.

Weber, Y. and N. Pliskin, ‘The effects of information systems integration and organizational culture on a firm’s effectiveness’. Information and Management, 30, 1996, 81–90.

Weber, Y., O. Shenkar and A. Raveh, ‘National and corporate cultural fit in mergers/acquisitions: an exploratory study’. Management Science, 42, 1996, 1215–1227.

Weber, Y. and S.Y. Tarba, ‘Human resource practices and performance of mergers and acquisitions in Israel’. Human Resource Management Review, 20, 2010, 203–211.

Weber, Y. and S.Y. Tarba, ‘Exploring integration approach in related mergers’. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 19, 2011, 202–221.

Weber, Y., S.Y. Tarba and A. Reichel‚ ‘International mergers and acquisitions performance revisited: the role of cultural distance and post-acquisition integration approach implementation’. Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions, 8, 2009, 1–18.

Weber, Y., S.Y. Tarba and A. Reichel, ‘A model of the influence of culture on integration approaches and international mergers and acquisitions performance’. International Studies of Management and Organization, 41, 2011, 9–24.

Weick, K.E., ‘The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: the Mann Gulch disaster’. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38, 1993, 628–652.

Weick, K.E., K.M. Sutcliffe and D. Obstfeld, ‘Organizing and the process of sensemaking’. Organization Science, 16, 2005, 409–421.

Wernerfelt, B., ‘A resource-based view of the firm’. Strategic Management Journal, 5, 1984, 171–180.

Zaheer, A., B. McEvily and V. Perrone, ‘Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of interorganizational and interpersonal trust on performance’. Organization Science, 9, 1998, 141–159.