CHAPTER ONE

SOCIALISTS

NATIONAL PERIODICALS IN THE HEARTLAND

Like feeding melting butter on the end of a hot awl to an infuriated wildcat.

The moment Mother Jones stepped off the train and onto the station platform at Mt. Carbon, West Virginia, as she recalled, the “corporate dogs set up a howl.” The company town represented a new, industrial form of feudalism, erected by Tianawha Coal and Coke Company to house workers. Housing usually was substandard and company store goods overpriced. Officials kept a close eye on residents. Mt. Carbon was one stop among hundreds for the indomitable white-haired, bespectacled sexagenarian during decades of stumping and loudly supporting strikers in mining towns. Tianawha authorities warned Jones she courted arrest if she spoke publicly. She recalled, “I told him that the soil of Virginia had been stained with the blood of the men who marched with Washington and Lafayette to found a government where the right of free speech should always exist.”1

The moment Mother Jones stepped off the train and onto the station platform at Mt. Carbon, West Virginia, as she recalled, the “corporate dogs set up a howl.” The company town represented a new, industrial form of feudalism, erected by Tianawha Coal and Coke Company to house workers. Housing usually was substandard and company store goods overpriced. Officials kept a close eye on residents. Mt. Carbon was one stop among hundreds for the indomitable white-haired, bespectacled sexagenarian during decades of stumping and loudly supporting strikers in mining towns. Tianawha authorities warned Jones she courted arrest if she spoke publicly. She recalled, “I told him that the soil of Virginia had been stained with the blood of the men who marched with Washington and Lafayette to found a government where the right of free speech should always exist.”1

The company ordered the local hotel not to feed or house Jones. It evicted the mining family that offered her a night’s lodging and fired the husband. “Every rain storm pours through the roof of the corporation shacks and wets the miner and his family,” Jones reported. “They must enter the mine early every morning and work from ten to twelve hours a day amid the poisonous gases. As I look around and see the condition of these miners who produce the wealth of the nation, and the injustice practiced on these helpless people, I tremble for the future of a nation whose legislation legalizes such infamy.”2

Mother Jones’ vivid testimony in the International Socialist Review (ISR) departed from the intellectual debates that dominated the early years of the dense monthly launched in Chicago in 1900 by Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, but by the end of the decade readers came to expect such tough reporting from the journal. By then the Review and the Appeal to Reason had emerged as the most significant nationally circulated socialist periodicals. By 1913, the Kansas-based weekly Appeal’s circulation rocketed to a stratospheric 760,000, making Julius A. Wayland’s newspaper Gulliver to the Lilliputian ISR’s 60,000 subscribers.3 But no socialist publishing venture made as much of an impact on American public discourse by publishing so much radical literature as did Kerr’s. This chapter will examine Kerr and Wayland’s considerable contributions to radical print culture. It will compare how the ISR and the Appeal adapted business and journalism strategies to perform social-movement media functions. Beyond those leading journals, the chapter surveys some of the hundreds of other socialist periodicals that ranged from a children’s magazine to union bulletins. Labor and politics emerge as predictably persistent topics, but more surprising themes such as religion, machines, and poetry thread through pages of the socialist press. First, a look at the similarities between ISR and the Appeal helps explain their leading role in nurturing socialist culture.

Commonalities between the International Socialist Review and the Appeal to Reason

Although ISR initially was as cerebral as the Appeal was folksy, the two periodicals had much in common. Their publishers did more than anyone to educate Americans about socialism.4 Wayland’s weekly claimed five thousand Appeal study clubs in 1906 that instructed readers in the social movement.5 Biographer Allen Ruff asserts Kerr’s successful business plan and commitment to making radical literature affordable and accessible made Kerr’s company “the foremost socialist publisher of the era.”6 Both the Appeal and ISR exerted much influence in Socialist Party politics, so much so that party leaders and socialist publishers eventually challenged their dominance of radical print culture.7 Crucially, both were independent periodicals with strong publishers and editors who did not have to answer to a party local or meddling press committee, as did many of their peers. Both publishers were products of the agrarian heartland yet succeeded in engaging readers in the urban East and mountainous West. Wayland and Kerr both experimented creatively with alternative business models to finance their anticapitalist ventures but resorted nonetheless to advertising. Their investigative reporting on labor issues and their activist journalism influenced radical politics in intended and unintended ways.

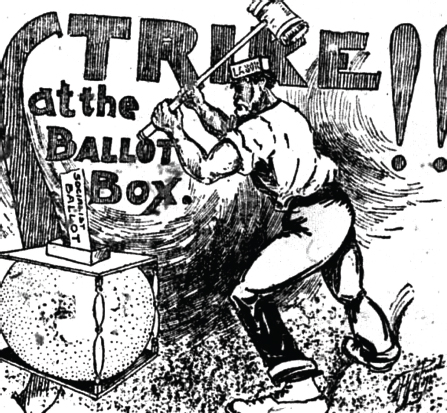

Untitled, Appeal to Reason, October 31, 1903.

The stature of the two journals also was partially the result of adding labor’s two most celebrated leaders to their mastheads. Eugene Debs penned editorials for the Appeal and mining organizer William “Big Bill” Haywood for the ISR. Another key to the two journals’ success was their prairie-bred publishers’ embrace of farmers as part of the proletariat, a departure from the European Marxists. Both publishers viewed advocacy journalism as the most effective way to promote socialism and counter hegemonic media. ISR, for example, once claimed the capitalist press “has held the workers in mental servitude for years, it has blinded us to our own interests.”8 Conversely, in 1911 prominent radical writer Joseph Cohen pronounced that the socialist press’s “opportunities for doing greater good are almost endless.”9 Kerr and Wayland both emphasized education as a prime function of the socialist press.

Kerr cast a broader and more intellectual net than the provincial Wayland. In its early years, ISR was a text-heavy sixty-four pages, plump with intellectually challenging essays and book reviews that kept its promise to report on international socialism, explain socialist theory, and relate socialism to American life.10 Ruff asserts the Review “conveys more information about the particular social and political cause for which it spoke than any other contemporary record.”11 It functioned as the voice of the movement’s theorists rather than of its rank and file, however, especially before 1908.

Kerr, yet another radical publisher inspired by Looking Backward, was the son of Scottish-born abolitionists who worked with African Americans in Georgia. Kerr discovered Marxism during studies with radical economist Richard Ely at the University of Wisconsin. He parlayed knowledge gained while working at a Unitarian publishing house after college into launching his own company in 1886.12 Months after marrying May Walden in 1892, the thirty-two-year-old publisher incorporated the Kerr company as a cooperative venture.13 When the Kerrs embraced socialism in the late 1890s, their lakeside Chicago suburban home became the nucleus of a circle of idealistic young socialists that included ISR cofounder and editor Algernon “Algie” Simons and his wife, May Wood Simons, who lived with the Kerrs for several months. May Kerr recalled how their enthusiasm for socialism “nearly set the house afire.”14

She also recalled her husband as a “shrewd bargainer.”15 The company translated and published innumerable European Marxist works, including the first English versions of the second and third volumes of Marx’s Das Capital. Its ambitious publishing program to make radical literature affordable and accessible introduced tens of thousands of Americans to a wide range of European radical thinkers, including the Brits William Morris and Robert Blatchford, Marx’s fellow Germans Friedrich Engels and Karl Kautsky, and Frenchman Paul Lafargue. Publication of these works made Kerr the main conduit of the transnationalism that colored American radical print culture.16

Kerr also Americanized socialism with its five-cent Pocket Library of Socialism series. Authors of the sixty pamphlets published in the company’s first decade-included Jack London, Clarence Darrow, and Debs.17 While the Appeal to Reason also published classic European Marxist works as well as those by Americans stretching back to Tom Paine, Wayland lacked Kerr’s enthusiasm for theory. In 1909, Kerr bought all plates and copyrights of the Appeal to Reason Publishing Company’s books.18 He also acquired copyrights from Debs and the Wilshire Book Company, the publishing arm of H. Gaylord Wilshire’s popular eponymous socialist magazine. Kerr’s expansive publishing ventures not only served as a repository and stimulus of socialist culture but also gave the ISR leverage against the circulation-colossus Appeal. The ISR’s debut in July 1900 further enhanced Chicago’s reputation as the hub of American radicalism.19 Because of its publisher’s broad swathe, no radical periodical performed the education function better than ISR.

The Launch of International Socialist Review under Editor Algie Simons

Kerr’s financing of the new monthly shows how socialist publishers adapted capitalist methods to fund their anticapitalist journals. Kerr initially sold two hundred $10 shares in ISR; Shareholders received no dividends but could buy books at cost.20 Kerr began to limit individuals to single shares and to allow them to buy these in $1 installments, a unique approach that dispersed control of the stock and enabled low-income workers to participate.21 By April 1901, some thirty-five hundred people subscribed to ISR at $1 a year, and an equal number bought it at newsstands for a dime. In a burst of corporate synergy, the magazine advertised Kerr books and pamphlets on its back cover and on inside pages. ISR also advertised other radical journals, which reciprocated.22 The company wobbled into the black by the end of 1903, although it continued to rely on personal loans and donations.

ISR followed the company model by publishing essays by every notable European socialist intellectual. Kerr and editor Simons also infused the publication with a distinctive American flavor. A Wisconsin farm boy who preferred reading, Simons escaped to the University of Wisconsin when a local lawyer gave him $100 to enroll. A product of the agrarian “hotbed of Populism,” whose family lost its farm in the Panic of 1893, Simons was receptive to socialism.23 Like Kerr, he read Marx in Ely’s class, and assisted him in the writing of Socialism and Social Reform. Simons also acquired some journalism chops by working as a stringer for the Madison Democrat and Chicago Record. His social conscience steered him to social work in Chicago in 1895, but fact-finding missions in the squalid stockyards’ “Packingtown” neighborhood convinced him only of charity’s futility. He joined the Socialist Labor Party and in spring 1899 began editing the SLP local’s Worker’s Call—which Kerr printed. Simons also stood among Socialist Party of America founders in Indianapolis. After the tragic death of the Simonses’ eighteen-month-old son, friends pooled funds to give the couple a respite in Europe, where visits with numerous socialist thinkers strengthened the Kerr firm’s transnational bonds. Once back in Chicago, Simons immersed himself in editing ISR.

Simons shared an ISR column with German-born socialist writer Ernest Untermann, titled “Socialism Abroad.” Readers found countless more international articles covering socialists from France to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, usually culled from European socialist magazines.24 Max Hayes compiled briefs in his “The World of Labor.” Essays scrutinized democracy and parsed socialism.25 ISR’s political contributors exploded any notion that radicalism spoke with a single voice. Simons raked anarchists, for example, in the wake of President William McKinley’s assassination by a self-described anarchist. Socialists use the ballot to end capitalism, he wrote, while useless anarchist violence enflames the public against all who advocate change. “Thus it comes about that over and over again the violent deeds of anarchists have been used as an excuse for attacking the only real enemy of anarchy—socialism.”26

Simons Provides Farmers a Socialist Voice

Editor Simons was most passionate when arguing for the inclusion of American farmers in the proletariat. He understood far better than urban, eastern socialists that the Marxist dichotomy of industrial workers versus capitalists ignored the United States’ agrarian heritage. In 1905, he reprinted in ISR a groundbreaking essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” influenced by another of his professors, Frederick Jackson Turner, whose seminal argument was that western agriculture made American society unique.27 Simons’s 1902 The American Farmer was the first book to analyze agriculture through a Marxist lens, and his was the preeminent radical voice on the issue. In ISR, Simons challenged the Marxist categorization of farm smallholders as petty bourgeoisie. Farmers not only worked with their hands but also were at the mercy of market vicissitudes and bank lenders, Simons explained, making them perfect recruits to rise against capitalism.28 The prolific Simons published in both socialist journals such as Wilshire’s and non-socialist magazines such as the Independent. He also cofounded Comrade magazine, wrote books, and served on the SP’s national executive committee from 1906 to 1910.

The Appeal, which also claimed farmers as comrades, serialized Simons’s “American History for the Workers” as a text for its study clubs.29 The Appeal painted a rosy picture of farming under socialism, in which the state would own farms worked by a “public agricultural service” that earned equal pay according to hours clocked—never more than four hours a day. “Those who would not work could not eat,” it explained. “To-day those who work least, enjoy all the advantages of progress.”30 Popular socialist journalist Kate Richards O’Hare, who grew up on a farm, also wrote of large collectives as farmers’ salvation, for the urban-oriented socialist monthly Wilshire’s.31 Meanwhile, ISR advised farmers to voluntarily share tractors and other machines—“Unless they want to lose their land to corporations and see their kids become wage slaves.”32

Ambivalence toward the Machine Age

Socialist journals offer insights into American workers’ ambivalence toward machines that were easing human toil but stealing jobs. A major incitement of the 1892 Homestead strikes stemmed from the stream of skilled jobs lost to machines. State-of-the-art improvements helped Carnegie Steel president Henry Clay Frick demolish the union even as he eliminated an entire shift by cutting wages and stretching the remaining two shifts’ workdays to twelve hours.33 “The World of Labor” frequently discussed new inventions displacing workers, such as portrait artists reduced to retouching machine-made portraits.34 Another article rued the toll that technology exacted on the machinists union: “Its craft life is flickering like a wind-blown candle.”35 A 1915 article ticked off astounding numbers about Henry Ford’s revolutionary automobile assembly line: The multiple spindle drill blasted seventy-two holes at once, enabling its two operators to drill six times faster—a 3,600 percent time gain.36

Yet many correspondents welcomed machines they believed could lift workers out of serfdom—if owned by workers. “Machinery is the servant of all,” Scott Nearing declared in ISR.37 The journal’s Mary Marcy expressed no nostalgia for the backbreaking labor of the romanticized “oldtime Woman’s Sphere.” She wrote in 1913, “No intelligent human being wants to return to candles or home dyeing and weaving; to the splitting and sawing of wood for the daily breakfast; to home butchering, lard rendering, candle-making that made the old ‘free days’ continuous arduous toil from three or four in the morning till late at night three hundred and sixty-five days in a year.”38 O’Hare weighed in that machines—under socialism—could end child labor.39 Wilshire’s enthused that street-sweeping machines exemplified how labor-saving machinery could eliminate the dirty work of manual labor. Its publisher deduced from such inventions that under socialism “there will be little or no unpleasant work to be done by the individual, and certainly no menial work.”40 Indiana ditch diggers who sent ISR a photo of a steam shovel that cut a third of their work force brightly predicted that in the cooperative commonwealth, “Nobody will have to work more than two or three hours a day and all the good things of life will be ours to enjoy.”41 The Appeal’s Wayland shared the belief that machines, large-scale farming, and even trusts were integral to the social revolution. He wrote, “The hurt is not because of the great aggregations of capital—but the private ownership of it.”42

International Socialist Review Becomes More Militant under New Editors

As corporations unleashed more violence against workers, Kerr grew more militant, which widened a philosophical rift with ISR editor Simons. He leaned toward the party’s yellow socialists, moderate gradualists that advocated using the ballot to effect a gradual move to socialism. Kerr increasingly veered toward the militant red socialists. Leftists like him championed the militant Industrial Workers of the World’s call for “direct action”—a troublesome phrase that could be interpreted as anything from a strike to dynamite—instead of the vote. 1908 election results lent some credence to their lack of faith in politics, as the 420,852 votes cast for Debs for president actually dropped a smidgen from the 3 percent of the popular vote he received in 1904. Kerr also desired an edgier editorial product. “The Review was too often stolid and leaden” under Simons, claims his biographer Robert Huston.43 Kerr also was irked that Simons’s other work distracted him from his ISR editorial duties. When Kerr fired Simons and took over as ISR editor in 1908, Kerr determined to enliven the journal and lure subscribers from the fire-breathing Appeal.44

He handed many of ISR’s editorial responsibilities over to Leslie and Mary Marcy. Short and square-jawed Mary was the company “spark plug,” according to Ralph Chaplin, future IWW cartoonist, poet, songsmith, and newspaper editor, who began contributing articles to ISR while barely out of his teens.45 ISR’s 1907 circulation had sunk below its 1901 level, but the Marcys’ lively journalism doubled ISR circulation three times in 1909 to nearly ten thousand. An editor’s note conceded the old ISR had mistakenly assumed that only a “select few of superior brain power” could write on socialism. “We have seen a new light,” it went on. “Working people know what’s best for them and are better than any theory.”46

Kerr’s new approach was based on the belief that grassroots, worker-produced media messages could best counter corporate-sponsored media hegemony. ISR recruited citizen labor journalists to provide eyewitness accounts of labor conflicts. Kerr’s 1910 invitation illuminated how instrumental he believed his monthly to be in the class struggle; it also underscores his conviction that ISR readers were not passive consumers but active partners:

Each month we propose to take a hand in each new battle. If a big strike is on in your city, send us a concise story of what the men have done and what they are trying to do. Never mind about the flowery language; the Review readers want the facts. Above all, send photographs with action in them. What we did for the free speech fight at Spokane and later at New Castle, for the shirt waist workers, the Philadelphia car men and the steel workers at McKees Rocks we can do for you when your fight is on, if you keep us in touch with the situation.47

The new policy provided far-flung readers with information as well as community. Oregon strawberry pickers responded by sending ISR photos of fifteen-year-old Susie Payne addressing a large crowd during a violent strike in which authorities roughed up girls and women.48 Reader contributions followed the radical press model of unabashed partisanship. An account of a Columbus, Ohio, streetcar strike apparently submitted by a reader not only informed readers that Ohio’s governor called out troops and police made sixty-one arrests but also proselytized. “It is deplorable that we have given over our streets to a few Philadelphia millionaires with which to grind and browbeat their employees who have asserted their manhood to the extent of demanding a slightly greater portion of what they produce.”49 The author’s use of “we” versus “they” epitomized the sense of group identity that social movement media must foster to mobilize members.

Riveting accounts of labor strife replaced theoretical tracts under the Marcys. The August 1911 cover boasted a new slogan, “The Fighting Magazine of the Working Class” that invariably framed labor heroically. Chaplin’s 1913 account of violent West Virginia coalmine strikes typified the gripping new reportorial style:

“They [mine guards] got my gun when they run me out of the creek, but I done borried my buddy’s, and I’m goin’ back.” This is what a slender, grimy lad of sixteen told me one night in the freight yards of a town not far from the martial law zone. He was picking coal for his mothers and sisters at “home” in the tent. His father was in the bullpen at Paterson [N.J.]. The boy had a bullet wound on his shoulder and numerous bayonet holes in the seat of his ragged breeches. “Took seven of them to run me out,” he boasted with a grin.50

Kerr began leavening text with more photographs and illustrations to dramatize labor’s battles. Nina McBride put a human face on labor when she contrasted the Library of Congress’s golden dome to the miserable lot of its “small army of poorly clad, shivering women” who on their hands and knees scrubbed the building’s 326,195 square feet of marble floors.51 The description shows ISR’s penchant for marshaling facts, like Louis Fraina’s report on steel mills that fired off these Bureau of Labor statistics: “Of the total 172,706 employees, 13,868, or 8.03 per cent, received less than 14 cents per hour; 20,527, or 11.89 per cent, received over 14 and under 16 cents; and 51,417, or 29.77 per cent, received over 16 and under 18 cents. Thus 85,812, or 49.69 per cent of all employees, received less than 18 cents per hour.”52 ISR also reprinted other socialist newspapers’ stories on labor, such as a Cleveland Press undercover reporter’s account of riding a steamship nine hundred miles to expose poor conditions faced by teenaged strikebreakers during a seamen’s strike.53

In 1910, a contributor sanctioned antimilitary sabotage in Europe, a view that reflected Kerr’s conversion to IWW-style direct action. “The motive is everything,” rationalized contributor Austin Lewis.54 Kerr also reprinted a Forum article that argued sabotage could be nonviolent, as when workers slow down or do inferior work.55 The journal waxed enthusiastically for the IWW’s 1909 “passive resistance” strike at the McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania, steel works. To enforce their demand for weekends off, workers quit work at noon Saturday and stayed out until Monday morning. They also threatened to kill a police officer for every striker killed, a threat to which the ISR attributed the strike’s peaceful end. The ISR proclaimed, “A concrete ‘lesson’ in ‘direct action’ was taught—and many learned.”56 That statement was a far cry from its 1901 contention that a steel strike defeat proved the trade unions needed to vote to tackle the trusts.57

An important part of the revamped ISR’s mission was to counter the mainstream press’s hostility toward strikers.58 An account of a 1913 Michigan copper mine strike stated: “The papers here, under the control of the companies, have, as usual, lied about the strike, slandered the strikers, burned the ‘locations’ up in their columns.”59 A report on the ransacking and burning of the Socialist blamed local newspapers for inciting the violence in a reversal of mainstream media’s usual framing of labor as a mob: “They are the properties of stock corporations and must do as they are told by their certified owners, in order to ‘make good’ on the job.”60

Fostering a Radical Workers’ Culture through Literature

Kerr also published poetry and short fiction to help counter negative mainstream representations of labor. The socialists’ worker alternated between hero and victim, which helps account for why movement literature bounced between buoyant and apocalyptic.61 Socialist journals romanticized workers in poetry that historian Aileen Kraditor ridicules as the “Hail to Thee O Proletariat genre.”62 ISR poems became grittier, however, in the publication’s second decade, when realist poetry by IWW organizer Arturo Giovannitti and others began to supplant Victorian sentimentalism. Jack London, arguably the era’s most influential American socialist, was another contributor.63 The January 1917 issue, containing his exclusive “The Dream of Debs,” published weeks after London died at forty, sold out in ten days.64 ISR occasionally reviewed art from the Marxist perspective that it should be a tool to convert the masses. Phillips Russell, for example, disliked a Belgian sculptor’s idealization of longshoremen with Adonis-like physiques. Russell would sculpt labor as “an east side sweatshop worker, shuffling toward his child-crowded tenement at 6:15 P.M., pausing occasionally to discharge his tubercular sputum into the gutter, his skin pale and corpselike, blue from lack of red-blooded food.”65

ISR editor Simons’s contemplations on the relationship between work and art pushed the magazine into new areas of Marxist thought, according to his biographer.66 Simons believed in the “instinct of workmanship,” a psychological need to create and take pride in one’s work, another reflection of the cultural shift from Victorianism.67 Simons followed the Anglo-American Arts and Crafts movement guided by William Morris, which sprang up in reaction to Victorian excess and the sterility of industrial mass production. Unlike Morris, however, Simons believed handicrafts amounted to dilettantism that failed to resolve the need to harmonize work and creativity.68 May Wood Simons, his wife and frequent ISR contributor, contributed to the ISR’s intellectual inquiry when she wrote that capitalism forced the working class to live surrounded by ugliness. Socialism, she asserted, would grant workers time to create beautiful and useful things.69 Her husband struggled to reconcile work and art throughout his career.

Of all its diverse intellectual perambulations, ISR’s hallmark internationalism educated its American audience about the global implications of corporate capitalism better than any other radical periodical. International coverage became more timely and dramatic under the Marcys. Illustrated accounts of capitalist exploitation of poor nations presaged the antiglobalization movement by nearly a century; the Review exposed diamond mining exploitation in South Africa, slums in the U.S.-controlled Philippines, and devious Standard Oil operations in China.70 Marion Wright reported from Hawaii that the newly introduced pineapple crop could revitalize small farms as long as laws limited corporations to farming fewer than a thousand acres.71 Headlines adopted a more rebellious tone, as in “The Class War in South Africa,” and “The Coming Economic Revolution in Abyssinia.”72 ISR support of colonial independence movements was a half century ahead of its times.

J. A. Wayland’s Appeal to American Individualism

Meanwhile, smack in the middle of the American Heartland, the Appeal to Reason prospered by focusing on domestic issues. The widowed Wayland had set up shop and settled on a gentleman’s farm with his five children in the southeastern corner of Kansas. By 1907, he had erected in downtown Girard a twenty-thousand-square-foot Temple of the Revolution that housed a state-of-the-art, three-deck color Goss cylinder press capable of running off up to forty-five thousand newspapers an hour in a union shop that also published Wayland’s other periodicals and hundreds of pamphlets.73 Official Appeal historian George Allan England loved to watch the press in motion. “In fancy I could see the papers flying like brands of living flame to light the darkness of the world,” he recalled.74 Wayland prided himself on the operation’s strict forty-seven-hour workweek for more than one hundred employees amid the brightest lighting and highest safety standards in the state.

Columns of epigrams, axioms, and socialistic fables showed off Wayland’s unparalleled talent as a pithy “paragrapher.”75 They accounted for much of the four-to-eight-page weekly’s allure. “President Roosevelt is gifted with wonderful musical accomplishments,” one began slyly in 1907. “His favorite instrument is the lyre, and he frequently entertains the nation with it.” Satire inflicted deeper cuts. The self-described “One Hoss Philosophy” Wayland pounded out on his battered typewriter, usually as he chomped the stump of a half-smoked cigar, was plain spoken and confrontational: “The capitalists deny that there are classes here as in Europe and yet they denounce Socialists for trying to array class against class! If there are not classes how can they be arrayed against each other? They know there are classes, they lie when they say there are none, and they fear the results when the people become conscious of their class interests.”76

Wayland insisted no conflict existed between socialism and American individualism. He connected socialism to such American icons as Tom Paine, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and John Brown.77 The persuasive power of Wayland’s American vernacular and epic tone is apparent in his explanation of why “We Want Socialism”: “Because it means the freedom of the workers and the leveling upward to a higher plane of all humanity. Because it means the end of poverty and misery and want; the end of the brute struggle for existence, and the beginning of real civilization.”78

As the century progressed, the Appeal’s meat and potatoes became its passionate if not histrionic crusades targeting enemies of the common man. Historian David Paul Nord’s 1975 study of the Appeal’s contents found that attacks on business (12.4 percent) and attacks on government (16.7 percent) accounted for nearly 30 percent of five themes that dominated its pages between 1901 and 1920.79 Politics was another important ingredient in the Appeal formula. One series outlined socialist successes in Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Columbus. Elections coverage was expansive, a reflection of Wayland’s moderate pro-politics stance. The Appeal’s daily edition published during the Socialist Party’s 1908 national convention highlighted the importance of social movement media when the Associated Press dropped coverage after the first day.80 The Appeal printed Debs’s acceptance speech and the party platform in a May 23 mega-issue mailed to a million readers. During the 1912 presidential campaign, the Appeal published several special editions that totaled nearly 11 million copies.81

Nord included election coverage among “socialist activities” that comprised another 12.6 percent of editorial content. The category also included matter such as a 1908 briefs column, which reported on socialist branches from Arkansas to Minnesota that gave readers a sense of the movement’s scope. “Social problems”—including poverty, crime, child labor, prostitution, suicide, unsafe working conditions, and alcoholism—filled another 5.9 percent of the news hole.82 The newspaper also jumped to the defense of various radicals’ rights to a free press and free speech. Essays scrutinized democracy and parsed socialism. Socialist theory, ranging from reprints of socialist classics to a column of epigrams on “What Socialism Will Do,” filled slightly more of the news hole, 7.4 percent. Essays by Marx, Engels, and George Bernard Shaw made the newspaper a “school for Socialists,” according to historian James Green.83 The Appeal also promoted Wayland’s Library of the World’s Workers, a dozen books by socialist writers delivered monthly that followed the Kerr marketing model. The ad advised, “Socialist books must be read and discussed around the firesides these long winter nights.”84

Innovations in Financing Socialist Periodicals

The Appeal also invited readers to leave their firesides to hear lectures by editor Debs, an innovative technique for gaining subscriptions. The Indiana native was socialism’s most beloved hero, adored for his midwestern integrity, admired for his stirring oratory, and esteemed for his courage ever since the 1894 Pullman strike. Between 1909 and 1913, the Appeal paid him $100 weekly to write editorials. Locals paid for Debs’s visit by buying hundreds of Appeal subscriptions. As Appeal historian Elliott Shore observes, “the association with Debs assured its remaining the most important paper in the field.”85

Kerr adopted a similar strategy using Haywood, another labor hero. After 1908, the IWW organizer and former Western Federation of Miners leader contributed frequently to ISR, whose support helped elect him representative to the 1910 International Socialist Congress in Copenhagen. Upon his return, Haywood undertook a speaking tour across North America under the auspices of the ISR Lecture Bureau.86 Every ticket entitled the bearer to a three-month subscription. Perhaps more significantly, the arrangement helped build a national base of red socialists. “ISR tours brought Haywood and other ‘revolutionists’ into contact with rank-and-file activists, the so-called Jimmy and Jenny Higginses of the movement, in unprecedented fashion,” Ruff wrote.87 In exchange, both Haywood and Debs gained national platforms for disseminating their views in the last decade in which print reigned unchallenged in the media universe. Their press tours provided a physical locus for radical culture nurtured in the journals the pair represented.

The most successful marketing technique was Wayland’s formidable “Appeal Army” of “Salesmen-Soldiers.” Top salespeople could win a trip to Girard, a motorcycle, or even a yacht.88 Each week an Appeal column recognized members. “Comrade Kiehl of Ashland, Pa., prescribes fifty-two doses of the Appeal for ten neighbors,” read one; another punned, “It may be good to be rich but it’s better to be a Goodrich if one can stir up such clubs as that of Comrade Goodrich of Omaha.”89 Besides lavishing individual praise on his sales force, Wayland shrewdly always attributed members’ motives to the larger goal of spreading the socialist gospel. “The Appeal army always moves in a body, always moves against the enemy and wastes not time with bickerings among its members,” a 1902 brief claimed.90 By 1917, top salespeople could win forty acres of Minnesota farmland.91

Business-savvy Wayland also turned to advertising. An entrepreneur at heart, he had no intention of eking out a living like his Populist publisher predecessors. Wayland once said making money under capitalism was like riding a bicycle: “Once you learn to ride it’s easier to keep your balance than to fall off.”92 To finance the Appeal’s growth, the paper included ads for middle-class gadgets such as stereopticons, Edison phonographs, and sewing machines, as well as for suspect morphine-addiction cures and “Crani-tonic” hair food. “Don’t Be a Wage Slave!” blared an ad that promoted a correspondence course on “How to Become a Mechano-Therapist.” (The ad explained, “The Mechano-Therapist is a drugless physician and a bloodless surgeon.”)93 Wayland also advertised products of the Girard Cereal Company and Girard Manufacturing Company, fruits of business ventures that made the village hum with socialist enterprise. Ads for Appeal to Reason cigars boasted the stogies, the boxes that held them, and their labels all were union-made.94 Yet other ads encouraged capitalist excess by dangling watches and furniture available on credit. The inevitable collision between Wayland’s business methods and idealism “created tensions at the core of the American socialist movement,” as Shore has amply documented.95 The idealistic yet indigent ISR also published dubious ads.

The Appeal collided with capitalism again when its crew went on strike. In October 1903, all forty-one Appeal employees, from the janitor to associate editor Untermann, formed a union and demanded raises and improvements in working conditions. The major sticking point was the demand by several Appeal Publishing Company officers that they receive dividends, a capitulation to the profits system that appalled staffers. Wayland immediately agreed to all demands except firing the secretary-treasurer and two other officers, including a Wayland relative, all of whom opposed the union. The entire staff walked out. The direct action sucker-punched Comrade Wayland. “I felt like a mariner in a stout ship tossed at the mercy of a storm,” he confessed to Appeal readers.96 Two days later, at a public meeting at the courthouse, the strike ended when Wayland offered to hand over the newspaper’s profits and business management to the Socialist Party National Executive Committee. The party refused because of its constitutional ban against having an official party paper.97 Appeal employees returned to work.

“Fighting Editor” Fred Warren and Muckraking in the Appeal

Not long after the strike, the Appeal’s most exciting decade commenced with Fred Warren’s appointment to the new position of managing editor. The accomplished printer and failed rural publisher liked to say he entered journalism at “the bottom of the ladder”—as an eleven-year-old printer’s apprentice—and studied the business until he learned it.98 Warren began his Appeal career working on the press but left in 1901 to publish Coming Nation, the periodical Wayland had surrendered to the Ruskin colonists in the 1890s. When the Ruskinites ceased publishing it, Warren and fellow Appeal staffer E. N. Richardson reinvented Coming Nation as a scrappy muckraking weekly. Unable to crack one hundred thousand in circulation, they closed shop in 1904 and merged Coming Nation into the Appeal. Warren’s slight build and spectacles gave little hint that he was a journalistic wolverine. The adventuresome editor, “electric with mental energy and fire,” initiated aggressive investigations into labor issues.99 His pit-bull hold on sensational stories made the Appeal a must-read for socialists and fellow radicals across the country.

“Fred Warren sensed that Americans, despite their protestations for peace, love a fight; and fights are what he gave them,” a staffer observed. “By sensationalizing these fights he kept his readers constantly on their toes with suspense.”100 Warren immediately dispatched reporter Allen Ricker to Colorado to cover an explosive standoff between miners and mine owners. He published a damning letter Ricker obtained from a Cleveland union-busting firm using what became an Appeal journalistic staple: deceit. The reporter had posed as a business owner soliciting union spies.101 Special correspondent J. L. Fitts even went undercover as a convict in a Florida work camp that he exposed as “the cruelest form of slavery.”102 The reporters’ central roles as protagonists in these stories demonstrates another characteristic of Appeal journalism, which frequently inserted itself into the news. Correspondent John Murray was sentenced to one hundred days in a Trinidad, Colorado, jail in 1914, for example, after he was convicted of contempt of court in connection with the newspaper’s petition campaign to recall the region’s federal district judge. The Appeal asked readers to donate $1 to pay for four subscriptions to rally Coloradans. “Our weapon is publicity,” it boasted, “and we wield it mercilessly.”103 Warren once claimed the secret to winning results in his journalistic campaigns was to “secure some central figure around which to make the fight.”104 A 1910s series on industrial accidents, for example, championed a Girard miner who had been crushed in an accident. He won $11,000 in the lawsuit Wayland sponsored.105 Warren also added visual punch to Appeal pages by cajoling “clever artists on the big papers with propositions to take off their hands any of their radical stuff which their own paper will not print.”106

Warren set off an Appeal avalanche of sensational muckraking, a pioneering form of investigative journalism characterized by a battery of empirical evidence wrapped in moral indignation. The classic example is Ida Tarbell’s 1902 “History of Standard Oil” series in McClure’s Magazine, which exposed how John D. Rockefeller Sr. schemed to acquire his oil monopoly.107 One of Warren’s earliest and most profound editorial decisions, however, resulted in a series that rivals Tarbell’s opus. He sent twenty-two-year-old socialist writer Upton Sinclair into the belly of Packingtown, Chicago’s meatpacking district and metaphor for cannibalistic capitalism. Warren had enjoyed Sinclair’s new novel about slavery, Manassas, so he suggested the writer retrain his focus onto twentieth-century “wage slavery.” For seven weeks, Sinclair lived and toiled undercover among Packingtown’s impoverished Lithuanian immigrants. He collected tales of wool pluckers whose fingers had been eaten off by acid and of sausage concocted from moldy meat dosed with borax and glycerin. He shaped the semifictional story to sound a socialist call to arms as his oppressed protagonist, Jurgis Rudkus, becomes enlightened. The first chapter of Sinclair’s series “The Jungle” appeared in the Appeal in February 1905.108

The next year, millions of readers devoured the melodramatic The Jungle published by Doubleday, Page & Company, which ignored its radical politics and promoted its grotesque revelations about food processing in what the New York Times hailed on its centennial as the first modern book-marketing campaign. When Sinclair met with President Roosevelt, a champion of meat-packaging reform, the Appeal milked the story.109 Within months, Congress passed the landmark Meat Inspection Act and Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. Sinclair nonetheless deemed his book a failure because readers ignored the workers’ plight. “I aimed at the public’s heart,” he later wrote, “and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”110 ISR editor Simons, whose 1899 pamphlet Packingtown actually first revealed many of The Jungle’s allegations, was indignant that so many critics fixated on the three pages describing meat production.111 More than a century later, however, the novel’s force endures. Doubleday’s blockbuster underscored the conundrum facing radical publishers, since neither the Appeal nor Sinclair had the capital to print the book. The capitalist press made millions by its depoliticized mass marketing. Sinclair used his profits to buy a farm near Princeton, New Jersey, which he turned into a socialist colony, Helicon Hall.

Appeal Muckraker George Shoaf

The Appeal’s star muckraker was George Shoaf, a tee-totaling former pastor, labor organizer, and brothel piano player who never traveled without his .38 caliber revolver and a Bowie knife. The twenty-nine-year-old Texan raconteur described himself as “politically and economically a rampant-revolutionist” who despised objectivity.112 In 1906, Warren sent the veteran yellow journalist to Colorado, where for a while he doubled as correspondent for both William Randolph Hearst’s Chicago American and the Appeal.113 A “gonzo journalist” decades before Hunter S. Thompson rode with the Hell’s Angels, Shoaf often placed himself at the center of his vivid accounts of violence in the coalfields. He disguised himself to investigate the lethal dynamiting of the Independence, Colorado, rail depot and named more than ten men as the culprits.114 Shoaf routinely stretched the ethical bounds of journalism by embellishing or fabricating stories. He saw no conflict in covering a Philadelphia strike and doing publicity for its leader. To obtain interviews for the Appeal, he pretended to work for commercial newspapers.115 Shoaf once wrote that a lack of facts should not impede a good story. He advised: “Use the names of the parties involved in the plot, give dates, places and such other incidents as will lend a semblance of truth to the proposition, crowd the story with fictitious names and character, throw ginger and insinuative suggestion into the article, write it up ‘red hot,’ and send it in.”116

He also served the very serious purpose of telling labor’s side in its impossible battles against the new corporate giants. Shoaf zigzagged the nation in search of capitalist outrages. The Appeal’s influence was such that when a federal district attorney refused to allow the “red sheet” Appeal reporter to interview Mexican revolutionaries imprisoned in Los Angeles, Shoaf only had to threaten to publish their conversation to get his interview. He included the exchange.117 In Mexico, he covered riots at a Sonoran mine.118 His 1910 investigation of a federal judge in Chicago forced his resignation after members of the loyal Appeal army fed Shoaf with evidence against the judge.119 Tips from his former city editor at the American also frequently bolstered Shoaf’s reportage. Mainstream journalists were some of the socialist muckraker’s best sources, he claimed, because they often possessed “valuable inside information” their corporate publishers refused to print.120

Shoaf’s investigation of Kentucky “nightriders” illustrates how social-movement media departed from the mainstream media model. In 1907, Shoaf investigated the torching of American Tobacco Company warehouses after denunciations of the deed in the mainstream press sparked Warren’s interest. “For experience had taught him that when capitalist newspapers praised a man or movement, working people had better watch out,” Shoaf recalled. “Contrariwise, when the capitalist press condemned a man or movement, it was up to the champions of labor to become alert.”121 He discovered the nightriders were small tobacco farmers who felt cheated by the company’s monopoly. During their 1910 trials, he produced a series on the “Revolutionary Farmers” illustrated by Ryan Walker, a popular cartoonist whose work had appeared sporadically in the Appeal since its 1895 debut. Warren linked the nightriders to iconic American patriotic motifs by prefacing Shoaf’s piece with Ralph Waldo Emerson’s famous lines, “The embattled farmers stood / And fired the shot heard round the world.”122 Shoaf’s sympathetic stories so pleased the farmers they named the Appeal official organ of their newly formed organization.123 Neither he nor Warren considered the affiliation a conflict of interest, because they saw their mission as advocating for the farmers. Shoaf’s dubious ethics, however, would eventually catch up to him and the Appeal.

The Appeal Faces Charges of Monopoly

As Appeal circulation peaked at 760,000 in 1913, rival socialist publishers raised other questions about its business methods. At its peak, the Appeal to Reason published several state and regional editions, such as a Southwest edition for Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas that occasionally added two extra pages of regional news.124 Missouri notes for September 4, 1909, for example, listed socialist Labor Day speakers slated for its larger cities. The Appeal paid state party secretaries $520 a year to act as editors and supply copy for the state editions.125 Competitors, however, charged Wayland with engineering a monopoly. Simons, as ISR editor in 1904, probably had the Appeal in mind when he charged socialist papers were more interested in marketing their product than in serving socialism. “The idea is abroad that if you only shout loud enough and use plenty of printer’s ink and smooth phrases, you are preaching socialism,” he wrote.126 Smaller publications could not compete with the Appeal’s low price—fifty cents a year for individuals and only a quarter for groups. Montana News editor Ida Crouch-Hazlett grumbled, “It is printed to sell, not to help the party.”127

The national party’s 1911 attempt to appropriate its subscription lecture series reveals more tensions with the influential but independent Appeal. The executive committee announced a national lyceum bureau would handle speakers for all socialist periodicals. Locals that paid headquarters $400 could keep a 40 percent commission on subscriptions. “This plan makes use of our whole party machinery to support the socialist Press,” announced Secretary J. Mahlon Barnes. “On the other hand, it uses the combined power of ALL the Socialist publications to build up the party organization.”128 An incensed Debs seethed that party leaders like Milwaukee newspaper publisher Victor Berger had ridiculed the Appeal lecture series, “as they have always ridiculed and denounced the Appeal and everybody connected with it, even though the Appeal’s policy has been to almost lick their boots and slop over them and appeal for funds for them to start a daily with which they may show their contempt for the Appeal seven times a week.”129 The lyceum never materialized, and Warren offered no apologies for the Appeal’s entrepreneurship. “This is a business institution, selling Socialist literature,” he stated. “Under capitalism it can be nothing else.”130 That reality proved a conundrum for hundreds of smaller socialist journals launched to sell the movement’s ideas, not to make profits.

A Broad Swathe of American Socialist Periodicals

Most of these socialist journals were local, like the four-page Commonwealth (1911–14) in Everett, Washington, or regional, like the California Social Democrat, the state party’s official organ launched in 1911.131 Fourteen appeared in Arkansas alone between 1901 and 1916. Only a handful attempted national circulation: the big Sunday edition of the daily New York Call; Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s one-woman social-feminist magazine, the Forerunner; the mild Christian Socialist; and The Young Socialists’ Magazine for working-class children.132 Dozens more socialist periodicals appeared in foreign languages. The ethnic socialist press remained vital to immigrant communities although their numbers gradually fell as the century progressed and the newcomers assimilated. One of the most durable was Työmies (“The Worker”), produced in Wisconsin by the Finnish socialist Työmies Society, whose chief function was to publish radical periodicals, pamphlets, and books for immigrants. The society served as a political, social, and cultural center for Finnish American working-class culture, promulgated in part by the newspaper’s chorus and drama clubs.133

Several union newspapers that endorsed socialism, such as Miner’s Magazine, relied on union dues to sustain them but also served several social movement media functions for socialists.134 Arkansas’s Union Labor Bulletin, official organ of the Central Trades and Labor Council, which unofficially backed socialism, was a font of information for dispersed party members. It announced local meetings, challenges to debate offered by various Socialists, letters from leading state Socialists, and statewide meeting news; supported Socialist campaigns to enact child labor laws and antitrust bills; endorsed government ownership of public utilities; and distributed Debs campaign buttons in 1904. “The Bulletin was a valuable tool for the Socialist party,” according to historian G. Gregory Kiser, “and contributed to the growing number of Socialists within the state.”135

A number of Socialist locals boasted their own newspapers through the Socialist Co-operative Publishing Company of Findlay, Ohio, which published papers in ninety-five cities in six states. Co-op general editor W. Harry Spears explained their utility: “If a Socialist writes up a local strike, and brings the revolutionary message printed in a home paper, every striker will read it aloud and think about it and his Socialist education will thereby begin.” The local named its newspaper and its local editor. Some content was local, but most comprised generic socialist literature shared by all, although each publication gave the impression it was published locally. The firm followed the Kerr model by requiring locals to buy stock shares at $10 each.136 Yet even the Findlay operation failed to prosper. Warren turned down Spears’s late-1910 proposal to make the Appeal printing plant Findlay’s central distribution point. Spears spun a grand scheme in which papers printed at Girard could be shipped to twenty nationwide distribution points, each of which would spin off twenty-five local newspapers.137 Urban radicals enjoyed a wide choice of reading; in 1912, a Seattle man peddled nearly five thousand copies a month of some dozen socialist newspapers from his hand-propelled news cart.138

Many socialist journals were the product of a strong-willed individual proprietor. Red socialist Hermon Titus, a physician and former Baptist minister, launched Seattle’s first socialist weekly, the lushly illustrated Socialist, weeks before the 1900 election, in which he unsuccessfully ran as a Socialist candidate for the U.S. Congress. Titus harbored national ambitions for his fiery journal, which prompted his move to Toledo four years later.139 Most socialist publishers, however, eyed smaller markets. “Scores of small-town Socialist weeklies appeared in Oklahoma, from the Okemah Sledge Hammer to the Sentinel Sword of Truth,” recalled publisher Oscar Ameringer, which helped account for the rural state hosting one of the nation’s strongest socialist movements. Oklahoma Pioneer, the official state party organ, was one of several newspapers he struggled to keep alive during his career. Ameringer once wrote, “Running a labor paper is like feeding melting butter on the end of a hot awl to an infuriated wildcat.”140 His financial plan involved soliciting enough subscriptions to knock out a couple of issues. When money ran out, he scrounged for more. Soon he could no longer pay the printing bills, and the periodical ceased. He would launch another shortly.

Hermon Titus’s weekly was the most influential socialist newspaper in the Pacific Northwest from 1900 through 1910. May 24, 1903.

The Third Incarnation of Coming Nation

Wayland was similarly resolute. In 1910, he reincarnated Coming Nation a third time, as an artistic, large-format monthly magazine on high-quality paper that aimed for a more optimistic and constructive tone than the Appeal.141 Simons’s biographers assert that the third Coming Nation pioneered many of the graphics innovations later credited to the Masses. The latter publication’s famous artists John Sloan and Art Young, in fact, illustrated Coming Nation covers, and Coming Nation published early work by Walter Lippmann and Sinclair Lewis.142 Wayland appointed Simons editor; ISR’s founding editor had just been fired again, this time by the Chicago Daily Socialist in a factional feud. Simons’s peripatetic career at six periodicals was not unusual among radical editors, for whom job security was a rarity. He and May Wood Simons produced excellent investigations on land ownership for Coming Nation and created the most attractively designed periodical yet produced by the radical press.

Nonfiction features formed the meat of a typical sixteen-page issue, buttressed by fiction, an editorial page, photographs and cartoons, a women’s page, a children’s activities page, and a back-cover cartoon. Despite the Coming Nation’s professed optimism, however, the Simonses’ penchant for enervating articles about “the wretchedness of the present” cast a gray tone that even Charles Edward Russell’s colorful political commentaries from Washington, D.C., failed to enliven.143 The magazine hit a circulation of sixty-thousand by 1912 but bled $6000 in each of its first two years of operation, a trend that accelerated when the cultured Simonses moved editorial operations from sleepy Girard back to pricey Chicago in February 1913. Warren suspended Coming Nation four months later, embittering his relations with the couple. Josephine Conger-Kaneko took it over to replace her socialist weekly, Progressive Woman, but it failed to make a third comeback.144

Simons, Conger-Kaneko, Kerr, and even Wayland devoted editorial space and energy to cajoling if not begging readers for their support. As Simons’s biographers observe, “Socialist journalists were accustomed to the ways of the deathbed rescue: hardly a year went by, even among the old standbys of the party press, without at least one front-page prediction of imminent demise unless loyal readers came to the rescue with new subscriptions, donations, or advertisements.”145 A prime example is the Christian Socialist’s last-gasp plea on its July 1918 front page: “Death or Deliverance? Shall the Christian Socialist Perish Now as a Martyr to World Democracy, or Shall It Live to Help Reconstruct the World?” After fifteen years of publishing the nationally circulated monthly outside of Chicago, the Rev. Edward Ellis Carr pondered whether it had been worth traveling up to eleven months a year while his seven children grew up poor and neglected. “Thus in the strength of middle manhood,” he summed up his journalistic career, “I surrendered home life and gave my body and soul, a ‘living sacrifice’ for the cause of Socialism.”146

Originally a Methodist, Carr became pastor of the liberal People’s Church of Kalamazoo, Michigan, in the late 1890s, joined the Social Democratic Party in 1900, and served as a delegate to the 1907 International Socialist Congress in Stuttgart. His newspaper spawned the Christian Socialist Fellowship, a small group of ministers and lay people who tried to build a bridge between the Socialist Party and American churches. Carr’s socially conservative journal published essays by religious and secular authors, reported on party news, sold classic Marxist works, chronicled labor struggles, printed sentimental fiction and poetry, and reprinted material from other socialist periodicals. Carr argued in his 1911 series “Socialism in the Bible” that the book condemned the profits system. Between 1904 and 1914, Christian Socialist reached twenty thousand subscribers from its Danville, Illinois, headquarters and published special editions for various Protestant denominations as well as one for Roman Catholics, whose run of 120,000 copies dwarfed all previous numbers.147

Religion in the Radical Press

Carr numbered among radicals who blended religion and radicalism by following the Protestant-inspired Social Gospel that gelled in the Gilded Age. The gospel preached that true Christianity required followers to actively work to improve social conditions that caused poverty. “A pure social democracy is the political fulfillment of Christianity,” wrote George Herron, onetime ISR religion columnist and founder of the Social Crusaders, which published the Social Crusader.148 Socialists, Wobblies, and even anarchists who rejected organized religion embraced Jesus Christ as a fellow worker and purveyor of brotherly love—and a social activist. Ameringer was among many radicals to who professed kinship with the “Carpenter of Nazareth.”149 The Masses’s December 1913 Christmas cover, for example, depicted a poster that read, “Jesus Christ the Workingman of Nazareth Will Speak at Brotherhood Hall—Subject—The Rights of Labor.”150 Debs often invoked Jesus as a workingman and biblical passages to justify workers’ campaigns against industrial capitalism.151 In turn, Debs also represented a Christ figure to many socialists, who viewed him as a worker who sacrificed himself for the masses’ salvation. Sinclair considered Jesus an agitator whose radical teachings had been corrupted by the institution of Christianity. National Rip-Saw editor Henry Tichenor, one of religion’s most vociferous critics, preferred another kindred biblical soul: “I always liked old Moses, the rebel of the Jews.”152 Tichenor was among socialists who reviled preacher Billy Sunday, the prototype televangelist, as the antithesis of Christ-like virtue. Up-and-coming socialist poet Carl Sandburg once accosted Sunday in the Masses:

You come along … tearing your shirt

Yelling about Jesus

I want to know … what the hell …

You know about Jesus.153

Deviations in socialist thought about religion expressed in their journals indicate diversity among socialists. ISR published numerous articles and essays both assaying and encouraging the relationship between socialism and religion. Kerr’s Pocket Library of Socialism contained several such works. Letters to the Call as well as editorial columns debated religion. Wilshire’s frequently contemplated the relationships among socialism, religion, and spirituality.154 Wilshire proclaimed socialism a religion in the sense that its promised end to poverty would birth spirituality.155 Muckraker Russell compared his socialist conversion to joining a church. “One must have the experience in grace, one must show that one has come out from the tents of the wicked and capitalism,” he explained.156 The Socialist Party officially deemed religion a private matter in 1908, however, after editor Carr charged ISR with promoting atheism.157 The move reflected a basic fundamental difference between American sensibilities and strict Marxism, which rejected religion as the opiate of the people.

The Catholic Church took an official stance against socialism in the 1890s because of its opposition to private property and secular tone. Many socialists reciprocated their distaste toward the hierarchical, authoritarian institution they often parodied as greedy and hypocritical. Wayland took sacrilege a step further when he lent $1000 to former Appeal staffers to found the rabidly anti-Catholic Menace in Missouri in 1911, although editor Warren denied any connection between the periodicals. Warren claimed he rejected Wayland’s calls for an anti-Catholic campaign in the Appeal. “Nothing would suit our capitalist masters more than a division of the working class on religious lines,” the usually combative editor explained.158 In contrast, the Rip-Saw’s June 1913 “Pulpit Edition” ripped into both Catholic and Protestant churches as evil institutions that cared only for the wealthy. Its colorful irreverence was one reason the combative Rip-Saw became the nation’s second-largest socialist periodical.159

The Sacrilegious National Rip-Saw

Founded in St. Louis in 1904 as a low-brow monthly, the Rip-Saw found new life in the 1910s when new publisher Phil Wagner assembled “arguably the finest socialist editorial staff in the world,” according to historian Sally Miller.160 They included editor Tichenor, Scott Nearing, Ameringer, former Appeal reporter Herlee Glessner (H. G.) Creel, and Frank and Kate Richards O’Hare—the latter remembered as “la passionara of the Corn Belt” among other accolades.161 Debs signed on after leaving the Appeal on bad terms in 1914. Although Kate O’Hare was a salaried associate editor who also earned book royalties, Frank O’Hare’s circulation manager title failed to convey the power he wielded at the newspaper and as manager of his wife’s celebrated career. According to his biographer, Frank believed Kate the better writer and bigger draw of the pair but often gave her story ideas and assignments that he edited when she was on the road.162

Based on the Appeal model, O’Hare dispatched his wife, Debs, and Ameringer on grueling cross-country tours to build Rip-Saw circulation, which reached 180,000 in 1912. They spoke at large socialist encampments resembling religious revivals set up at the edges of small towns. The gatherings drew up to twenty thousand of the Southwest’s “debt-ridden dirt farmers, migratory share tenants, railroad workers, lumberjacks, and their hard-working spouses” to socialist classes and lectures interspersed with socialist songs and music.163 Debs recalled his surprise when eight thousand people showed up at his first encampment outside of remote Golden, Texas, in 1914. “Far as the eye could reach along all the roads there was the stream of farmers’ wagons, filled with their families, and all of them waving red flags,” he marveled.164

The Rip-Saw followed the Appeal formula of muckraking, capitalist-bashing, and down-home discourse, subsidized by ads for assorted quack medicines.165 Like the Appeal’s Shoaf, Creel traversed the nation in search of capitalist wrongdoing. He spent about a year covering timber workers’ perilous campaign to unionize in Louisiana, where he claimed lumber owners tried to murder him.166 Tichenor once assigned Creel to work undercover as a Salvation Army Santa Claus to expose the organization’s “graft.”167 Creel authored a well-researched five-part series on the cotton industry that drew parallels between “King Cotton’s” wage slavery of both blacks and whites and antebellum chattel slavery. “He verifies his facts and marshals them like an army before putting them on paper,” Tichenor told readers. Even as the editor bragged about the Rip-Saw’s accuracy, however, he inaccurately claimed, “No other paper is so carefully edited to exclude everything but rock-bottom facts.”168 As in other radical periodicals, opinion rippled through sensational Rip-Saw reportage as well as its anti-religious rants. Despite its hefty circulation, the Rip-Saw’s influence remained largely regional, due to its focus on western land and labor issues combined with its aversion to party politics.

Conclusion

The Rip-Saw and hundreds of other socialist organs comprised a lively print culture of resistance to the rising corporate state. Perhaps they best performed the social movement media’s education function. Thousands of essays and articles explaining socialism and deconstructing capitalism gave readers a new way to comprehend social inequity. The socialist press also provided abundant information on movement developments. Just one example is the Oklahoma Pioneer, which notified socialists of party meetings, encampments, and campaigns across the state. The journals’ editorials and news provided voice for labor in the string of battles for basic rights to organize and share a more equitable slice of the nation’s booming wealth. The Appeal’s citizen journalism, for example, lent voice to strawberry pickers in Oregon and streetcar strikers in Ohio who could not receive a fair hearing in the mainstream press. The widespread geographic distribution of socialist periodicals—including sections of the United States today labeled solidly conservative “red states”—speaks to the breadth of discontent with the new economic order in the early 1900s. A century later, their print culture would be supplanted by online resistance to the global corporate order.

Hundreds of thousands of Americans identified with socialism’s call for reclaiming power from the capitalist behemoths they considered un-American. In the early 1900s, not only the journals’ contents but also their organization created a group identity, as in the case of the Appeal army. Simply selling the Appeal constituted an act against capitalism. Articles, cartoons, and campaigns sustained a broader imagined community of socialists whose only engagement in the social movement may have been reading the journal that appeared in their mailboxes. The knowledge that they were not alone enabled readers to perhaps take the next step—voting for a Socialist Party candidate. The poems, jokes, and literature this imagined community shared in its periodicals helped create a distinctive socialist culture that privileged working-class values and sensibilities.

Wayland’s behemoth Appeal and Kerr’s cerebral but scrappy ISR stand out in part because they were products of personal journalism, stamped by the character of their long-term, strong-minded publishers. The success of the ISR and Appeal to Reason can also be partly credited to their publishers’ innovations in funding and marketing their journals in a capitalist economy. The socialist journals’ numbers attest to radicals’ infinite faith in newspapers to educate and hence convert readers. Their diversity also reveals divisions in American socialist thought exemplified by Kerr’s split with editor Simons. As will be seen, divisions over policy—compounded by personality conflicts among influential socialist journalists/ politicians—handicapped the socialist press’s unlikely campaign to breach the dominant hegemony that sanctified capitalism as the engine of American democracy.

Some socialists believed their movement’s biggest handicap was a lack of daily newspapers to counter negative mainstream press frames of their creed. While almost all socialist journals appeared only weekly or monthly, many socialists dreamed of launching a daily newspaper. They believed that by delivering their news through a socialist lens in a timely and comprehensive manner they could compete in the rough-and-tumble world of daily urban journalism. In New York, city socialists saved and scrimped for six years to make their daily newspaper a reality.