CHAPTER TWO

DAILIES

SOCIALISTS TAKE ON THE MAINSTREAM PRESS

“There was something akin to a holy joy in working for the Daily.”

At 11:02 A.M. on May 30, 1908, city editor Gordon Wood and his handful of bleary-eyed staff members put to bed the first issue of their new daily newspaper in a shabby loft at 6 Park Place in Manhattan, soon to be razed for the fifty-seven-story Woolworth Building. When the young, red-headed “printer’s devil,” or apprentice, raced up the stairs with the first papers a couple of hours later, the journalists perked up to examine their product. “We read everything in sight—advertisements as well as the regular stuff,” Louis Kopelin recalled. They grimaced at typographical errors forced by the deadline rush that littered its pages like pesky flies but overall approved of their “kid.” A few hours later, newsboys paced the Brooklyn Bridge crying out, “Wuxtry—new pa-a-a-per! Buy the Call!”

At 11:02 A.M. on May 30, 1908, city editor Gordon Wood and his handful of bleary-eyed staff members put to bed the first issue of their new daily newspaper in a shabby loft at 6 Park Place in Manhattan, soon to be razed for the fifty-seven-story Woolworth Building. When the young, red-headed “printer’s devil,” or apprentice, raced up the stairs with the first papers a couple of hours later, the journalists perked up to examine their product. “We read everything in sight—advertisements as well as the regular stuff,” Louis Kopelin recalled. They grimaced at typographical errors forced by the deadline rush that littered its pages like pesky flies but overall approved of their “kid.” A few hours later, newsboys paced the Brooklyn Bridge crying out, “Wuxtry—new pa-a-a-per! Buy the Call!”

That night, nearly every one of four thousand people packed into the midtown Grand Central Palace clutched a penny issue of the New York Evening Call. Nearly all had played a small role in its six-year gestation, some donating pennies to get the press rolling. They cheered wildly when New York Socialist Party chair and emcee, Morris Hillquit, held up the first copy amid the flock of flags and pennants signifying various unions, Socialist Party locals, and the Jewish Daily Forward. Edwin Markham of “The Man with the Hoe” fame read his latest overwrought poem, “A Free Press,” written especially for the occasion. Two lines read, “Flash down the sky-born lightnings of the Pen; Let loose the cramped-up thunders of the Types.”

Finally, the man whom the workers had braved a torrential rain to hear stepped onstage. They roared when Eugene Debs hoisted the Call and shouted, “Here it is, every line throbbing with the life of the working class!” Then came the closer, the reason the impoverished publishers invited the charismatic socialist leader east, where he proved as popular among urban factory workers as he had with Rocky Mountains miners. “This paper, The Call, this voice of the revolution,” Debs boomed, ”ought to have a hundred thousand subscribers from the day of the first issue.”1

Call circulation never came close to Debs’s goal, but by the eve of U.S. entrance into the war in 1917, its publishers claimed it was “widely quoted as the ablest expressions for the thoughts of forward looking Socialists.”2 The six-to-eight-page daily was the East’s most important socialist periodical in English. Together with the Socialist Labor Party’s (SLP) doctrinaire Daily People; the politically powerful Milwaukee Leader; debt-ridden Chicago Daily Socialist; and Oklahoma Daily Leader, created in 1917 to oppose the war, the Call comprised an exclusive if destitute club of English-language socialist periodicals that took on the dizzying demands of daily journalism. Not the least of their challenges was financing a publication officially opposed to capitalism. Socialist dailies in foreign languages fared better, an indication of the working class’s preponderance of immigrants. In 1912, New York’s profitable Jewish Daily Forward, or Forverts, published in Yiddish, claimed an enviable national circulation of 120,000, for example, and Chicago radicals in 1910 published daily newspapers in Czech, German, and Polish. These dailies could rely on their ethnic communities for support, according to labor press historian Jon Bekken. “They not only did not compete directly with the capitalist press, they could draw upon their communities’ institutional networks and resources for news, readers, and support.”3 Cash-strapped socialist dailies in English struggled to devise alternative economic models to sustain them in the capitalist economy. This chapter will focus on the Call in its analysis of the role daily newspapers played in socialist culture and political discourse. The newspaper’s management by a publishing committee, its advocacy journalism, and its role as voice of the New York Socialist Party offer useful examples of how social-movement media functioned differently than the mainstream dailies they reviled but whose news template they often followed.

The Call and the Milwaukee Leader made the biggest marks of the dailies; the former mainly by providing a voice for eastern workers, the latter by electing Wisconsin Socialists to office. Both spoke for the Socialist Party’s right wing, which championed politics as the soundest route to the cooperative commonwealth. Their most glaring difference was in management. Unbending Victor Berger served as editor in chief of the Leader throughout the 1910s, in contrast to the parade of editors who needed to please the committee that oversaw the Call. The Milwaukee daily epitomized the decade’s synergy between politics and journalism, as it was instrumental not only in Berger’s 1910 election as the nation’s first Socialist congressman but also in the election of Milwaukee’s entire Socialist slate that year, including its mayor and seven aldermen. By decade’s end, however, no radical journalist would pay a higher price than Berger for flexing that power.

New York’s Workingman’s Co-operative Publishing Association

New Yorkers planted the seed for an English-language daily in 1882 by creating the Workingman’s Co-operative Publishing Association (WCPA). It remained inert until a coalition of socialists, other radicals, and unions engaged it to publish a daily Leader to boost their mayoral candidate during the 1886 election campaign. He lost and the paper vanished. Six years later, lawyer and real estate developer Leon Malkiel of the SLP’s National Executive Committee resurrected the idea. A key financial backer of what became the Call, he bought a $10 ad in the party’s weekly People, which solicited funds to turn it into a daily. By 1899, the fund reached $13,000, but the battle between the SLP’s Daniel De Leon and the Social Democratic Party (SDP) derailed the daily. A court ruled the newspaper belonged to the SLP, which converted the newspaper into the Daily People, edited by De Leon from 1900 through 1914. In 1900, the rival SDP, which included Malkiel and Hillquit, launched the Worker, a weekly edited by Algernon Lee. The Worker carried the flag for Debs’s 1900 presidential bid, and his ninety-one thousand votes convinced supporters the time was ripe for a new socialist newspaper that addressed Americans in English. They began raising the requisite $50,000 by passing a hat in an old hall on East 13th Street, then revived the WCPA in 1902. Along with a president, treasurer, and three auditors, a board of management comprising a seven-member board of trustees and six advisory board members oversaw the association.4 The editor reported to the board. The Call’s unconventional organization was as radical as its content.

For the next six years, socialists struggled to raise funds. Like the Charles H. Kerr Company, the WCPA sold bonds at $5 each, payable in fifteen years at 4 percent interest.5 “No Party meeting was complete without a collection for the [daily],” William Feigenbaum recalled. The association sponsored fairs, bazaars, and picnics. A preview edition published during a sixteen-day fair generated several thousand dollars. Feigenbaum’s likening of fund-raising to a religious experience indicates the exalted role newspapers played in the radical experience: “It was for the Daily, and there was something akin to a holy joy in working for the Daily that made the limbs less tired, that soothed aching heads, that eased burning feet, that made up for the great expenditures of money of the thousands of Comrades who attended.”6

The 1906 city elections made clear the pressing need for a Socialist daily when newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst’s upstart Municipal Ownership League halved the Socialist vote. Hearst’s new party, under whose banner he almost won the mayor’s office, appropriated much of the Socialist platform. It called for public control and ownership of gas, water, ice, electric, and transportation services. Hearst newspapers combated trusts in every city in which they were published, and in the early 1900s, Hearst papers routinely sided with workers in big strikes. Biographer David Nasaw asserts that early in his career no other politician “had a record of support for labor as straightforward and consistent as Hearst’s.”7 These stands helped Hearst win two terms as a Democratic congressman from New York but undercut his bid to be the 1904 Democratic candidate for president. “Hearstism” worried ISR editor A. M. Simons because the league’s call for municipal utilities and nationalization of some industries diverted attention from the socialist mission to organize workers to take control.8

A Voice for Workers

Finally, the new daily appeared, its front-page banner quoting Karl Marx: “WORKERS UNITE! YOU HAVE NOTHING TO LOSE BUT YOUR CHAINS. YOU HAVE A WORLD TO GAIN!” Otherwise, little distinguished the inaugural front page from other urban dailies’. Editors hoped to compete in New York’s jostling newspaper market by offering something for everyone, including a red-tinged woman’s department, theater reviews, sports, and children’s page. Competitors included Joseph Pulitzer’s World, which in 1910 boasted a combined morning and evening circulation of 762,671. Hearst’s Evening Journal followed at 600,000, trailed by the staid morning New York Times at 175,000.9 The early Call’s news menu leaned more toward the yellow journals’ sensationalism. “Police Boost Dope in Baltimore,” “After Contractors on Blackwell’s,” and “Boy Deserted in Swamp: Tied to Tree by Tramp” were among front-page fare, alongside stories of strikes and socialists such as “Chester Is Quiet; No Cars Running” and “Trenton Socialists Active.” The broad editorial content, however, reflected one challenge facing a social movement periodical seeking a mass audience: it risked diluting its socialist group identity.

One feature that distinguished the Call from the mainstream press was the abundant information it provided readers about socialist and labor union activities. More than two columns that listed meetings on October 10, 1909, attest to the scope of the city’s radical activity. Letters to the Call editor showcase a lively discourse among proponents of various “isms” and the spectrum of radical hues.10 The Call opened its pages to party criticism, an endless source of correspondence, based on the editors’ republican faith in “free discussion.” They reminded contributors to stay civil. “Because one thinks another comrade is jeopardizing the movement, it is not necessary to call him a horse-thief or to reflect upon his ancestry,” a statement explained.11 The newspaper swiftly began emphasizing labor news. Top stories for the January 19, 1910, front page were “Miners’ Convention Now in Full Swing,” “5,000 Pants Workers Go Out on Strike,” “Milk Strikers Sue Boss for Security,” and “Phila. Traction Strike Probable.” Call essays stressed practical applications of socialism over theory by addressing questions such as “Why Not Own the Roads?”12 Human-interest stories emphasized poverty’s cruel toll.13 The Call also published briefs about socialist news deciphered from foreign exchange newspapers received from around the world, but its global reach fell far short of Kerr’s ISR.14 The Call focused on New York. It emphasized its role as the people’s press by attempting a short-lived alternative “newsgathering machine” of correspondents in 1914 it called an “Associated Press of Labor.” Editors told readers: “The Evening Call is the people’s paper, your paper. It isn’t muzzled by any trust.”15

A Sunday edition and magazine added on October 10, 1910, initially relied on heavy translations of socialist thinkers typified by a serialized version of Gustavus Myers’s History of the Supreme Court of the United States in mind-numbing blocks of miniscule type. But under editor Frank McDonald and his successor, former Wilshire’s magazine associate editor Joshua Wanhope, the Sunday magazine began to feature lively exposés and pungent political cartoons. Like the popular press, the Call treated cartoons as an important part of the editorial mix, although its were uniformly political. Ryan Walker of the Appeal to Reason contributed, along with mainstream cartoonists like John F. Hart. Call publishers boasted, “Its cartoons are as purposeful as they are trenchant with wit and humor.”16

The Call’s best-known byline belonged to celebrated journalist Charles Edward Russell, who began donating his trademark exposés soon after he joined the Socialist Party in 1908. Editors deemed Russell’s association with the Call as newsworthy as his exposé of the so-called traction trust. The all-cap subhead read, “Charles Edward Russell Begins Fight on Metropolitan Fare Grabbing System.” The following bullet boasted: “Famous Writer and Authority on Traction Problems Selects Evening Call to Expose Methods.” A two-column photo of the square-jawed Russell completed the package.17 A box asked readers to send tips about the trust.18 Despite frenzied publicity, however, a citizen Strap Hangers League the Call claimed was inspired by Russell’s stories never gained traction.19 The paper gained more currency when socialist writer Robert Hunter, author of the well-received Poverty, signed on as associate editor in spring 1909.

Exposés of poor labor conditions and incompetent city government became a Call staple. A 1909 exposé revealed the city was collecting rent from Bowery brothels, a 1910 series examined the city’s “slovenly” foster care system, and a 1912 investigation described filthy kitchens in the city’s top hotels.20 The stream of Call exposés followed the yellow-journalism formula of shameless self-promotion.21 “The Call Wins Fight on Rotten Buildings,” “Forced to Act by Call’s Exposé,” and “The Call Helps Union to Get Rid of Spy” typified headlines.22 Its hubris should not obscure the important service the Call performed by reporting on the slew of inequities facing the city’s working class and connecting them to the broader economic landscape. While its collapse of all social evil into a symptom of capitalism was simplistic and its tone didactic, the Call was the only English-language newspaper in New York that explored the direct relationship between the nation’s basic economic system and poverty, disease, and unsafe housing.

A 1909 account of rampant unemployment demonstrates how Call headlines and text framed subjects as victims of industrial capitalism. It described a Bowery employment office as dismal and dark, its clients’ opportunities as bleak: “Their haggard faces and famishing looks tell the same mad tale of a social condition in which men are thrown out because, like old useless rags, they are needed no more by those who cannot exploit them.”23 In 1915, a reporter used similar imagery to describe a bread line of women: “Lean, gaunt-eyed creatures they were, with wispy hair that stuck out grotesquely from under hats…. [M]y feet still ache from standing on one spot too long merely to watch them!”24 The Call blamed the sinking of the Titanic on capitalism because the ship was undermanned. It claimed the mainstream press followed the Call investigation into the shortage of trained seamen aboard passenger ships.25 In 1915, its comment on the city’s slow response to its exposure of firetrap schools dripped with sarcasm: “Perhaps it will need the burning of a hundred children or so to start something.”26

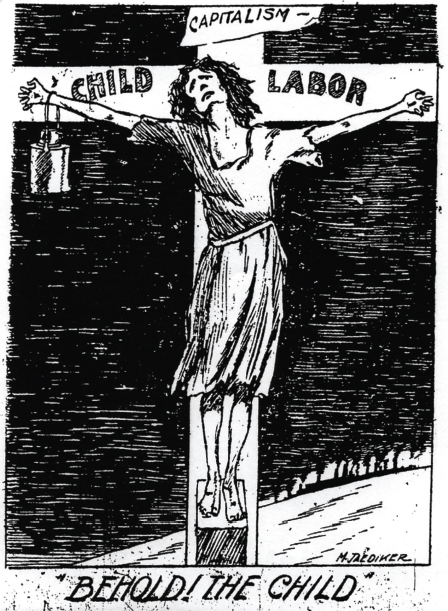

Abolishing child labor was one of the Call’s causes. Behold! The Child! Call, October 27, 1908.

Call Coverage of the “Uprising of the Twenty Thousand”

The Call’s reference to firetraps harkened one of the twentieth-century’s worst industrial disasters. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company fire was the tragic epilogue to a landmark strike. Call coverage of both events sheds light on how it viewed advocacy as part of its journalistic mission. The Uprising of the Twenty Thousand sparked in fall 1909, when Triangle locked out workers who had been trying to organize a union at its factory in the top three floors of the ten-story Asch Building, a half block from Washington Square. The workers, mostly Italian or Jewish immigrant girls and women aged sixteen to twenty-four years, earned about $5 for working seven days a week from 7:30 A.M. to 6:30 P.M. sewing popular blouses, known as shirtwaists.27 The number of women picketing Triangle snowballed from a dozen on October 4, 1909, to an unprecedented twenty thousand striking garment workers by November, about two-thirds of the work force. They shut down the entire Lower East Side garment district.28

The strike disproved the notion the young immigrant women were too emotional to organize. The fledgling International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union’s first fight opened the door to its future success. Part of the strike’s significance also lay in its alliance between working- and upper-class women. The Women’s Trade Union League, a partnership between middle-class reformers and working-class women to raise wages and improve working conditions, mobilized to provide funds and protect pickets from police assaults. As the Call reported, “The police as usual freely used their clubs on strikers.”29 Socialist women pitched in with the league, helping strikers conduct shop meetings, canvassing neighborhoods, and bringing in the peripatetic Mother Jones to rally them.30 Middle-class suffragists also lent support. Cross-class alliances frayed, however, as the Call revealed.

While the conflict between the factory owners and scrappy seamstresses captured mainstream media attention, none covered the strike in such depth as the Call. Two foreign-language socialist dailies, the venerable New Yorker Volkszeitung and Forverts, also provided blanket coverage in German and Yiddish. The strike inspired improved coverage of women throughout the socialist press. “Across the nation Socialist newspapers increased their coverage of women’s news and conveyed an image of women workers at the center of the struggle,” according to radical historian Mary Jo Buhle.31 The Call was a font of information. Bertha Poole Wehyl described the low pay, long hours, and poor conditions behind the strike.32 Sensational headlines topped stories about thirty-seven pickets arrested and fined November 30.33 The paper published stories listing names and fines of all arrested and printed charts tallying arrests, fines, and jail terms.34 It related accounts of harassment, name-calling, and sexual advances by police.35 Suffrage leader Anna Howard Shaw held up a copy of a Call story at a rally as evidence of police misconduct.36 Poems such as “The Ballad of the Shirt Waist Worker” romanticized the young strikers.37 Editorials scored police and courts, while cartoons lampooned them.38

The Call also became actively involved in the strike, a signature function of the radical press.39 Editorial appeals for donations provided the union’s address, and the paper printed rules for pickets in three languages.40 On December 29, 1909, it published a special fund-raising strike edition, one of many such numbers it produced during various strikes.41 It is indicative of the radical press mission that all proceeds went to the strike fund, despite the newspaper’s financial woes. Recent Vassar College graduates edited the special, which included articles in Italian, Yiddish, and English. A thousand shirtwaist workers hawked the four-page issue in the streets for a nickel. The lead story framed the strike’s significance as serving socialist interests by raising class consciousness among working women: “For its deeper meaning lies in that the working class woman is feeling her identity of interests with the working class man, that she is not only feeling, but THINKING, and thinking she is becoming conscious of her power as a member of the working class.”42

Besides proselytizing, the special reported many useful facts: lists of shops that settled, dates and fines of 653 arrests, a reprint of the Survey’s “The History of the Strike” (another example of radical and mainstream media crossover), and it published portraits of key players. It editorialized for women to only wear shirtwaists bearing the union label. Contributor Theresa Malkiel’s trademark pity seeped from her description of “The Jobless Girls,” which contradicted the empowering image the gutsy young pickets projected: “These timid, poor girls, some of them mere children, had to meet life’s problems almost from the very cradle.” The special number itself became news when photos of the female newsies filled the next day’s paper, which congratulated itself for creating “something of a sensation in local journalistic circles.”43 The underdog Call happily reported that the World, Wall Street Journal, and Telegram published positive comments—indicating the editors’ need for validation by mainstream newspapers that for once were following the Call on a story. All forty-five thousand copies sold out in two hours. One customer paid $5 for one.44

The Call relished its role as the strikers’ voice. On Christmas Day, the lead story was “Waist Makers’ Union through The Call Denies That the Strike Is about to Be Called Off.” One explanation for the Call’s zeal may be the concentration of social feminists affiliated with the newspaper, including Rose Pastor Stokes and Theresa Malkiel, a member of the national party’s National Woman’s Committee executive board and a prolific critic of party sexism (see chapter 9). Former Call editor Algernon Lee could have been speaking for Malkiel when he declared at the Mother Jones rally, “The labor movement must organize women, treat them as sisters, as comrades and equals!”45 Hillquit, who represented jailed pickets in court, addressed the rally where garment workers first declared their general strike. He raked the mainstream press for trivializing the women’s strike: “Your work is no fun and your strike is no joke, and shame on the newspapers who make light of it because you happen to be girls.”46

Hillquit exaggerated, as the big dailies did give the strikers sympathetic and generous coverage. It was true, however, that mainstream newspapers emphasized the novelty of upending class and gender roles. The colorful spectacle of the teenage girl pickets and their upper-class female guardians in the streets enthralled reporters. Strikers and socialists resented the publicity their wealthy supporters attracted. Millionaire suffragist Alva Vanderbilt Belmont made headlines when she bailed out striking pickets in night court, as did glamorous suffragist Inez Milholland when police arrested her for protesting their treatment of strikers. An irked Call pointedly observed, “The great bulk of the material aid given to the strikers came from poor men and women.”47 Malkiel and two fellow national woman’s committee members complained in a letter to the editor about reports that upper-class women did more for strikers than did socialist women. The socialist women’s claim that the slight placed them in the most “humiliating position” in the history of the labor movement may have been hyperbolic, but it revealed the party’s burgeoning gender gap.48 The February 27, 1910, Call Sunday magazine challenged the appropriation of the workers’ drama in Malkiel’s “The Story of a Shirtwaist Striker.” Her fictional jailed striker offers an acidic portrait of Milholland, whom she blames for provoking their arrest: “She didn’t lose anything by it—had all the excitement she was looking for, posed as a martyr, had a dozen or more pictures taken free of charge and was then taken home by her rich pa. It’s on account of her that we’ll have to stay here over night, for she had the trial postponed until tomorrow.”49

Malkiel’s story led a Woman’s Day edition that contemplated the strike’s historic significance in the wake of a February 10, 1910, agreement ending the walkout. It awarded many shirtwaist workers increased wages, shorter hours, and better working conditions. An editorial asserted that the strike demonstrated women’s capacity “for organization and heroic resistance.”50 Another argued that women’s move into the working world was developing “what we have been wont to regard as the masculine traits of courage, self-reliance and capacity for disciplined effort.”51 Notably absent from the contract, however, was union recognition. Several companies refused even to sign. Among them was Triangle.

Fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory

The March 26, 1911, edition of the Call came out dressed in traditional newspaper mourning, a heavy black rule bordering the front-page text. Its contents described how, on the previous afternoon, fire ignited on the Triangle factory’s eighth floor. Employees there and on the tenth floor quickly escaped, but those on the ninth floor were trapped. One of two stairwells filled with smoke; a locked door blocked access to the other. The flimsy iron fire escape collapsed under the weight of fleeing workers, the elevator broke, and none of the fire trucks’ ladders could reach beyond the sixth floor. As flames engulfed the ninth floor, trapped workers began breaking windows and jumping to their deaths. The final death toll stood at 146.52

WCPA board member William Feigenbaum later claimed only the Call fought “the fight that naturally arose out of the fire,” by which he meant holding its capitalist owners responsible for murder. The “bitter tears” and condolences of the mainstream press and its push for stricter fire laws, he stated, missed the point.53 A March 27 Call editorial called the tragedy “Murder and nothing else but murder.” Socialist artist John Sloan’s iconic five-column skeleton cartoon dominated the front page. It depicts a smoldering female corpse trapped inside a triangle labeled “Rent,” “Profits,” and “Interest.”54 The second page displayed photographs of twenty victims. Feigenbaum’s claim was incorrect, however, as Hearst’s Evening Journal also linked the deaths to the exploitation of women factory workers in an editorial bluntly entitled, “The Murder of Those Unhappy Girls on Saturday.” The editorial illustrates historian Elizabeth Burt’s point that the tragedy generated considerable mainstream media discourse on women’s poor working conditions missing from their strike coverage.55

The Call displayed deadline-driven journalistic skills in blanket coverage choreographed by city editor Phillips Russell.56 Unlike most dailies, its investigation emphasized the factory owner’s culpability instead of the city’s lax fire code.57 It differentiated itself from mainstream papers, which seemed satisfied by the Triangle owners’ indictment. The Call campaigned for investigations in other factories. “Any punishment meted out to the Triangle partners should be only the beginning,” it editorialized. “Capitalist justice is usually satisfied if an individual is punished, but it seeks to let the class continue its former inhuman actions.”58 When Triangle tried to buy a $250 ad, the Call called it a bribe, then returned the check, after publishing a copy of it.59

The Call tried to mobilize workers’ anger and grief. An editorial about the massive funeral demonstration—which it helped organize—observed many more workers were “slaughtered by capitalism.” The demonstration was “going to be an exhibition of growing working class solidarity.”60 The Call mustered verbal rhetoric to rouse the proletariat.61 “Yesterday a great, black scar of quivering grief and indignation disfigured the face of New York,” began the front-page account of the somber funeral procession. Huge photographs attested to the more than 150,000 mourners who marched and the million more who watched. City editor Russell optimistically framed the event as a show of empowered labor: “The working class of New York for once has gathered itself together and realizes its strength. It will not forget.”62 The Triangle owners’ acquittal, however, showed how difficult it was to change the status quo. A juror described the fire simply as “an act of God.”63

Bayonne Strike Coverage Counters Mainstream Press Frames

Mainstream media’s enamored coverage of the shirtwaist workers proved an exception to its usual hostility toward strikes. Call coverage of a 1916 oil-workers strike in Bayonne, New Jersey, offers a more typical example of the role it played in countering popular press frames of strikers as violent mobs. In 1914, the five thousand workers at Standard Oil’s mammoth refinery earned an average of $2.50 a day for a seventy-six-hour workweek, although rates varied widely according to skills. Most were foreign-born, mostly Poles but also Italians, Russians, Irish, and Czechs. Polish immigrants dominated one of the lowest paid groups, still cleaners, who descended into emptied stills to scrape off tar and other debris while wrapped in heavy clothes to protect them from near-boiling temperatures. Still cleaners complained foremen called them names and sometimes locked them in the stills until they passed out. They first struck in summer 1915, demanding the dismissal of the most disliked foreman and a 15 percent wage increase.

The company refused to consider their demands, following the usual script dictated by Standard Oil owners, John D. Rockefellers senior and junior. Bayonne’s mayor, who doubled as Standard’s lawyer, urged the plant manager to hire “private security guards,” basically five hundred toughs recruited off the street and handed guns, as a Call exposé explained.64 Over the next few days, they shot and killed five unarmed workers. A guard also died, and police and deputies rampaged worker neighborhoods. Robert Minor, a leading newspaper cartoonist and avowed socialist, not only sketched but also wrote about the scene for the Call. “I had never seen men fired on before, and it seemed strange that they did not run as the bullets whistled around their ears,” he wrote.65 Police arrested 129 workers, as well as 100 guards. The latter arrests pleased workers, who heeded the sheriff’s appeal to their patriotism to return to work. Standard Oil fired the most active strikers, although remaining workers received raises up to 10 percent. No one ever was charged with the killings.66

That incident was prelude to the October 4, 1916, walkout of six hundred paraffin workers who demanded a 20 percent raise. It mushroomed to eight thousand workers. Privileged English-speaking craftsmen refused to join the call for a general strike by several other departments, comprising mainly Polish, Hungarian, and Italian workers. The snub brought into high relief the nativism that fueled ugly anger against the waves of foreigners flooding the nation. Americans targeted the strange-sounding, oddly dressed eastern Europeans as the source of multitudinous problems arising from industrialism like so much factory smoke. Standard Oil excelled at exploiting this prejudice. On October 10, management shut down the entire plant when twelve hundred strikers blocked the entrance, putting forty-six hundred men out of work. The mayor approved any police action his client, Standard Oil, deemed necessary. The partnership exemplified the complicity between the state and corporations as they invariably joined forces against workers. Police bullets killed nine people, including a bride sitting by her upstairs parlor window, and twenty-five others were seriously injured in the ensuing violence.

The contrast between popular press and Call coverage illustrates the role the radical newspapers played in reporting on labor. Historian Philip Foner observes that “the New York commercial press reported the strike in Bayonne as if it were the act of an insurrectionary mob rather than a prime example of police mob rule.”67 The liberal magazine New Republic blamed the New York dailies for inciting violence. It asserted, “From the very beginning of the battle, the authorities of Bayonne resorted to violence and mob law to break the strike.” It charged the big city dailies with falsifying headlines to make it appear police were “heroically upholding the law against a criminal mob.” Examples of this misleading framing included “Bayonne Rioters Held in Check” (New York Times); “Bayonne Rioters Loot Stores (New York Journal); “New Bayonne Mob Clubbed Out of Captured R.R. Station” (New York Mail); and “Strike Mobs Rout Police, Loot and Burn in Bayonne” (Evening World). “The reporting of the Bayonne strike has breathed the spirit of lynch law and the pogrom,” New Republic concluded. “It has done enormous injury to the prestige of the press among thinking workingmen.”68

The Call had correctly predicted strikers would die and the mainstream press would blame strikers.69 It editorialized, “Never yet has there been a labor dispute with Rockefeller that the laborers did not furnish some corpses to grace the occasion.”70 Police stormed the workers’ neighborhood, shooting at people, tearing up saloons that defied an order to close, and raiding homes.71 “I felt last night that I just got back from the trenches,” wrote Call reporter A. M. Howland. “The police were merciless. Again and again the shots rang out. Again and again the ambulances passed and returned.”72 Call photographs showed police with Gatling guns and rapid-firing rifles, as did mainstream newspapers. Once past the headlines and lead paragraphs, in fact, the big dailies’ reportage was similar to the Call’s; the difference lay with where they placed blame for the violence. The final line of Howland’s Call account made no pretense of objectivity: “WHAT SHALL BE DONE WITH THESE MURDERS?”

Another significant difference in coverage was that only the Call addressed the xenophobic nature of the assault. The Bayonne Evening Review blamed the alleged riots on the immigrant workers’ “hereditary impulse to wreck and ruin when the restraints of their native environment was [sic] changed to the wide freedom in their new homes in America.”73 A New York Times story, headlined “Threaten Race War in Bayonne Strike,” valorized three hundred English-speaking workers who planned to march through the strike zone to return to work.74 Radical journalist John Reed noted in a New York Tribune magazine piece later summarized by the Call that Bayonne typified the Rockefeller strategy to exploit “racial and religious antipathies.”75 Call city editor Chester Wright likewise observed the racial divide between “whites” and the “others,” Bayonne’s many eastern European immigrants. “For the ‘others’ yesterday was a day of terror,” he wrote.76 He reported seeing police bash strikers’ skulls with clubs. Howland’s first-person account of a police march upon the workers’ neighborhood reported: “The strikers are utterly unorganized. Practically all of them are unarmed. I saw no evidence of either attack or even of resistance, only a desire to get out of the way of the murderous bullets.”77

Anarchy reigned in Bayonne, exclaimed a Call editorial—visual rhetoric that demonstrated the reach of anarchist stereotypes.78 Another charged that Standard Oil ran New Jersey.79 The Call also interviewed workers to put the strike in context. It quoted an anonymous striker, “And, let me tell you, a man can’t raise a family on $1.50 a day or $2 a day. That’s what this strike is all about it.”80 This sympathetic coverage spurred Bayonne police to confiscate copies of the Call, whose publishers continued to smuggle it across the bay.81 The violence subsided October 14, American-born workers reentered the plant under police guard October 18, and the remaining strikers returned to work two days later on the promise that federal mediators would negotiate for their demands. The Call headline framed it differently: “Bayonne Strikers Cowed by Guns of Standard Oil Controlled Police, Vote to Resume Work.”82 Although the Call termed the strike a failure because no union resulted, historian George Dorsey argues the lethal encounters marked a turning point in labor history because they forced the Rockefellers to finally revamp their medieval labor policy. Standard Oil created an annuity and benefit plan for retirees and introduced death, accident, and sickness benefits. Personnel and training departments established hiring and firing guidelines, and a 1918 employment department set procedures for discipline, wage adjustments, and appeals.83 Ironically, the corporation’s pragmatic workplace improvements worked against the social revolution.

A Counter to Hegemonic Media

As demonstrated during the Bayonne and shirtwaist strikes, a major Call function was to counter hegemonic news accounts of the labor movement. Hostile strike coverage helps explain why the Call considered the mainstream press labor’s enemy.84 The newspaper also was forthright about the socialist press mission to create a social revolution. “That is the party’s means of publicity, and on publicity depends its chances of doing really effective work,” a 1912 editorial explained.85 As a social movement medium, Call publishers rejected the purported objectivity of journalism’s so-called information model adopted by the New York Times in the 1890s that came to dominate twentieth-century journalism.86 While it may be easier to spot bias in the Call’s passionate pro-labor coverage, however, scholars have since pointed out that hegemonic media are as biased toward dominant powers despite their claims of objectivity.87

One drawback of the Call’s binary view of its place in the media landscape—socialist versus capitalist press—was that it frequently reduced the newspaper to a reactive role. It could not shed its need to legitimate itself through the prism of hegemonic media. Call scoops invariably pointed out that other dailies ignored news it broke, while other stories simply reacted to the big dailies’ perceived lies or omissions. The Call bragged it drove the big dailies to publicize exposures by the U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations “by day after day of the hardest kind of fighting.”88 It also implored readers not to patronize commercial newspapers because “as long as the workers read and support them they can be trusted to suppress the truth and print the lies.”89

The Call’s rationale that “the working class cannot permit the capitalist class to determine for it what is news and what is not news” presaged what by the end of the twentieth century had mushroomed into a full-blown social movement determined to limit media conglomeration.90 Although lacking a vocabulary to critique media hegemony, the Call understood the media’s central role in maintaining the status quo by ignoring challenges to the social order. An editorial referred to that point when the Call congratulated itself on a 1910 series detailing the lynching of striking Florida cigar makers: “The daily newspapers, metropolitan and other, their columns filled with all sorts of worthless information, were silent about the civil war in Tampa.”91 Its antipress rhetoric sometimes approached parody, however, as in this 1916 Call description of the capitalist press as “a slimy, venomous, treacherous, lying reptile; a thing to hate and avoid; a thing worthy of no credence whatever in a life and death struggle between labor and capital.”92

Browsing Call pages, however, reveals the divide between New York’s radical and mainstream press was less a dichotomy than the Call acknowledged. While editors trolled the commercial press to counter their omissions, exaggerations, and takes on the news,93 they also reprinted excerpts and views from them.94 Hearst’s newspapers, for example, touted forms of moderate socialism. Popular journalists sympathetic to socialism frequently donated their services to radical journals. Lincoln Steffens, for example, sent dispatches to the Call from the 1908 Republican convention, which the newspaper covered at length from its Socialist perspective. “Republicans Have Not Fooled the Workers,” read a typical headline.95 Conversely, star Call muckraker Russell continued to publish in mainstream journals.

Showcase for Socialist Culture

Another key Call function was nurturing a rich socialist culture that produced books, plays, songs, and art. Articles and reviews reflected the Marxist belief that art should be political; no frilly odes to spring sullied Call pages. It reviewed provocative books such as Franz Boas’s The Mind of Primitive Man or Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Man-Made World; or, Our Andocentric Culture. A review praised young Carl Sandburg as “Chicago’s Socialist Poet.”96 A 1915 profile of barefoot dancer Isadora Duncan explained how her philosophy claimed beauty “not just for artists but the heritage of free men and women.”97 Art was propagandistic, as evident in a photo of Bruno Zimm’s sculpture The Figure of Labor. The shirtless man holding a pick, the sculptor told the Call, symbolizes “the growing consciousness among the working class of the power and destiny of labor, as set forth in the Socialist philosophy.”98 Playwright Percy MacKaye argued that to fulfill its civic potential the theater must be publicly owned.99 A 1916 full-page tribute to the late, lapsed socialist Jack London demonstrated the novelist’s stature among radicals.100 Poems sentimentalized the downtrodden, but much content indicates the Call envisioned a middle-class audience.101 Lines from Irish socialist playwright George Bernard Shaw’s Arms and the Man made their way into antiwar editorials.102 Reviews of classical concerts appeared amid politically colored works.103 The mélange demonstrated the under-capitalized Call’s efforts to offer socialist readers the rich stew of news available in the advertising-fat commercial dailies.

In later years, the Call attempted humor with “The Silver Lining,” a column of one-liners, such as “The wine press is not the only press that uses ‘grape vine’ service.”104 The all-American pastime of baseball dominated the sports columns, although they began to diversify when 1912 Olympics reports showcased photographs of track racers, cyclists, marathon runners, and pole-vaulters. Broader sports coverage on new American leisure pursuits such as golf and tennis soon followed.105 Notices and ads for socialist picnics, lectures, and dances indicate the social aspects of radical culture, including the Call’s annual fair and ball.106 The Socialist Press Club publicized its speakers and an annual costume ball.107 The Call always put out a special edition for radicals’ most important holiday, May Day, the International Worker’s Day, which commemorated the four Haymarket martyrs and their fight for an eight-hour day. May 1 had been the intended launch date for the Call, which unfailingly covered the holiday’s annual big parades in special editions.108 Unlike IWW and anarchist periodicals, the milder Call also recognized the federal Labor Day in September.109

Voice of the New York Socialist Party

The gradualist Call’s attention to labor derived from its prime political function of recruiting members to the Socialist Party and electing its political candidates. “Congress is the boss,” asserted a 1914 editorial that sounded less than revolutionary. A group of “good, active, aggressive, militant, class-conscious” socialists elected to Congress, it argued, could “do more in a year for Socialism and the working class than in ten years of steady agitation.”110 The newspaper engaged in politics beyond editorializing. On the eve of the 1913 election, it mobilized readers to distribute a hundred thousand copies of the Socialist Municipal Platform.111 Every election inspired ebullient front-page headlines, no matter how tepid the Socialist turnout.112 A 1913 banner announcing “New York Socialists Roll Up Big Vote,” for example, obscured that the count was no higher than the anemic pre-Call election of 1905. The static tally contradicted its backers’ belief that a newspaper could dramatically boost the Socialist vote. Circulation temporarily slumped, as it invariably followed party fortunes. The following year, however, the paper and New York party enjoyed their biggest political success when the Call supported Meyer London (1871–1926), a Lithuanian-born labor lawyer who in 1914 became the nation’s second socialist congressman, representing the city’s Lower East Side. The Call also helped elect several socialist state legislators, and in 1917 Hillquit’s antiwar platform took 21.7 percent of the vote (he finished last) in the city’s three-way mayoral race. In 1916, it printed London’s pioneering address in full from the Congressional Record on the need for “social insurance”: unemployment, sickness and disability coverage, old-age insurance, and benefits for widows and orphans.113

The Call’s preference for politics over direct action put it at odds with more militant socialists such as ISR’s Charles Kerr. Disgruntled former staffer J. Louis Engdahl was among critics who derided the relatively conservative Call as “Hillquit’s paper.”114 The socialist lawyer wielded tremendous influence as a member of both the WCPA and the Socialist Party’s National Executive Committee.115 When a 1911 Call editorial called the committee “incompetent” and “dishonest,” Hillquit complained to the WCPA Board of Management.116 The newspaper published a board resolution that the statement was “out of place.”117

Challenges Facing a Newspaper Run by Committee

That incident reveals the dilemma facing editors of a newspaper run by committee. Rankled editors tended to leave. Within weeks of the launch, city editor Gordon replaced William Mailly as managing editor.118 In 1909, Lee left to head the newly established Rand School of Social Science, the same year the office moved to a ramshackle loft at 442 Pearl Street. Herman Simpson, a City College instructor, briefly succeeded Lee as editor in chief before Sunday magazine editor McDonald assumed the title in 1912. Russell served as city editor for two years around that time, followed by Harry Smith. The board lured Wright as managing editor in May 1914. The former Milwaukee Leader city editor had moved to Chicago’s Morning World and had last worked for the California Social-Democrat. He brought western ideas about journalistic “punch” to New York.119 Fred Warren lured several Call writers in the other direction, to the Appeal to Reason, including his eventual successor, Kopelin.120

“The Call has had many editors,” Hillquit acknowledged in 1914. “Not one of them has been able to stand the terrific pace for a long time—some have been forced to quit in time, some have broken down under the strain.”121 Opportunities to offend readers appeared infinite: A Brooklyn socialist complained the Call ignored his borough, an electrical workers union threatened a libel lawsuit, and a reader objected to serving wine at Call picnics.122 “The active workers on the paper are forever harshly criticized, almost reproved for what they do, and don’t do,” a WCPA member observed.123 The board considered publishing a leaflet in 1911 to document all the Call had done for organized labor, including “reporting their strikes, giving publicity to their troubles and wishes, refusing to accept advertisements from scab concerns.”124

Neither did working conditions enhance employee loyalty. Reporters clambered up a set of rickety stairs to desks lined up in a dimly lit sixth-floor loft littered with old newspapers. Linotype machines rattled and banged louder than the reporters’ clacking typewriters amid a foul odor wafting from the stereotyping machine. Everyone worked at least twelve hours a day, some seven days a week. “We are dubbing along the best way we can trying to cover New York in metropolitan newspaper style with a shoestring,” Gordon wrote the board.125 Lee not only wrote editorials but also laid out several pages, penned a “Questions and Answers” column, answered letters to the editor, read all his competitors, and recruited volunteer contributors. One was Mailly’s wife, Bertha, who edited the children’s department and covered school boards, suffrage, and public meetings, when not fundraising. Although circulation approached twenty thousand within weeks of its 1908 debut, the Call was in debt from its first number, and the $36.73 collected at a July 4 picnic was insufficient to solve the cash-flow problem. Not even salaried employees could count on receiving a paycheck.126 More than once business manager Anna Maley announced at the end of the week she lacked cash to pay staffers. “I have one hundred dollars left to be divided among us eight, or ten, as the case may be,” she would tell the reporters. “How shall we divide it? Who needs the money most?”

“THE LIFE OF THE CALL IS IN DANGER!” screamed a letter to association members in September, inaugurating what became a perpetual fund-raising tactic.127 The situation was so dire that at an October gathering, Stokes, a former factory worker who wed a socialist millionaire, unhooked her pearl pin and tossed it into a hat passed for the Call.128 The WCPA rejected a suggestion to shutter the Call after the election.129 In December, the Socialist Party of Greater New York instructed locals to prioritize helping the Call.130 Someone in 1909 suggested a self-denial week in a full-page Call “symposium” on its needs. The newspaper switched to a morning edition at the end of its first month to lower delivery costs and doubled its price to two cents. Debs’s former running mate Benjamin Hanford made maudlin appeals to workers to donate a day’s wages: “Do you love your dollar better than your Call?” Readers responded with almost $6,000.131 Even in 1912, when the Call hit its peak thirty-two thousand circulation, the association suffered a net loss of nearly $10,000.132 WCPA president William Passage threatened to resign in 1914 unless the newspaper stopped making “morally unjustifiable” false claims it ever would be self-sustaining.133 “The limit of running the paper on faith and forced loans has been reached,” he wrote.134

Office politics also rocked the Call. In February 1909, seventeen staffers demanded the removal of Otto Wegener, the paper’s third business manager. Wegener stayed, however, and the board officiously denied their request that an office staffer attend meetings.135 When the assistant business manager quit, she portrayed Wegener as oppressive as any capitalist boss: “The manager has harped so much upon the laziness and lack of discipline among our workers that he has convinced the Board as it seems that the one thing necessary for our success is a set of automatons who never greet each other, who never smile, who bend to their work as he does with the stolidity and immovability of The Man with the Hoe.”136

Advertising created another minefield. Although editors likened mainstream media ads to the “most brazen bribery,” they acknowledged the Call needed them, since it charged only a penny per copy.137 H. Gaylord Wilshire worried whether the Call could succeed without the big department store ads that were the popular dailies’ financial mainstay. He suggested it consider appealing more to women.138 Ads actually were abundant enough to allow the Call to expand to eight pages on Saturdays in January 1909.139 While never a huge revenue source, display ads from 1910 indicate businesses believed the Call audience possessed some disposable income. These included real estate, homebuilders, Ex-Lax, unionlabel clothing, shoe stores, Long Island lakeside bungalow sites, optometrists, furniture, gas ranges, and pianos. The piano ads caused a stir when the board refused a union demand to ban them because it claimed the company treated labor unfairly. The Call offered the union space to air its grievances but would not drop the ad.140 Other ads offended other constituencies. The Finnish branch of the New York socialists protested an ad for “capitalistic” Pearson’s magazine.141 A shareholder objected to one for the “crooked” Workingmen’s Sick and Death Benefit Fund.142 In 1911, complaints from two people instigated an investigation that resulted in a seven-page report clearing editors on charges that advertisers controlled Call editorial policy.143 The socialist daily never fully resolved the contradiction between its charge that big advertisers controlled the mainstream press and its practice of accepting ads.144

Criticism came from other corners. Letters offer insights into why the Call had a difficult time forging a strong identity. Hanford complained, “I wish they’d put a little more definite and concrete socialism in it,” while a reader grumbled “longwinded” editorials parsed politics and unionism too much.145 WCPA secretary J. Chant Lipes offered this assessment on the Call’s first anniversary: “Too little news (compared with Journal and World), too much socialism, too gloomy, pessimistic a tone.” He recommended more local news, “bright, snappy humorous reportorial work,” and shorter, simpler editorials.146 Backer Leon Malkiel in 1913 called a conference with editors to revamp the paper. “The news section of the Call to-day presents the appearance more of a Trade Union Bulletin than a newspaper,” he complained.147 A 1912 gathering at the Socialist Press Club in New York gave journalists a chance to gripe about their critics. “The Socialists dictate continually what should be the policy of their papers, regardless as to whether they are carpenters or skilled in newspaper work,” stated Allan Benson, future Appeal editor and presidential candidate.148 The WCPA board interfered, for example, after two party locals condemned articles they charged offended the Catholic Church.149

In July 1913, the board instructed then-editor MacDonald: Condense the AFL newsletter to one page. Contain sports to two columns. Ignore boxing matches because pugilism is barbaric.150 Passage threatened to resign a second time when MacDonald ignored his instructions. “We have not tried to dictate how you should write every line of the paper, but there are certain rules that we have laid down, that we consider entirely reasonable,” he wrote him. “To put it perfectly plain, ‘Obey orders.’”151 MacDonald left in 1914. Three board members helped city editor Harry Smith put out the paper until Warren, the Kansas tornado propelling the Appeal to Reason, accepted the board’s invitation to edit the Call in spring 1915. He toyed with investing $100,000 in it but followed the Call’s long line of editors out the door within a year.152

Victor Berger’s Influential Milwaukee Leader

The challenges of publishing a newspaper by committee provide a key to understanding why the Call never exerted as much political influence as did Berger’s Milwaukee Leader.153 Even though the Social Democratic Publishing Company produced the daily newspaper, Berger controlled a majority share of stock shared by several unions, branches of the Socialist Party, and individuals. Berger also was editor in chief of the Leader from its inaugural issue on December 7, 1911, until 1919. The Leader also benefitted from “guardian angel” Elizabeth H. Thomas, a wealthy Milwaukee Quaker with radical views, who besides fund-raising routinely gave the Leader crucial cash infusions.154 Like other socialist publishing ventures, the Leader was owned mainly by working-class shareholders, including more than 100 branches of the Socialist Party and 140 trade unions.155 And also like its peers, it never turned a profit.

The Leader espoused Berger’s “Milwaukee Idea” of bridging revolutionary change with labor struggles. Detractors sneeringly dubbed his mild brand of Democratic socialism “sewer socialism” because of its focus on improving municipal works. Milwaukee socialists under Berger campaigned on basic issues such as honest government, cleaning up neighborhoods, creating community parks, installing sewers, improving schools, and publically owning utilities. The Leader also provided a voice for socialists by countering the virulent anti-socialist views of the city’s mainstream Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Sentinel. Berger’s cooperation with trade unions and attendance at AFL conventions as a member of the Typographical Union, however, rankled more militant socialists.

Berger’s independence and strength as an editor contrasted with the cooks crowding the Call’s kitchen. “Victor was a powerful editorial writer and a most skilful editor,” recalled editor Oscar Ameringer, who left the Rip-Saw for the Leader in 1912. “He would appeal to the reason, intelligence, heart and obvious self-interest of the many, but never to the passions and prejudices of the mob.”156 Berger’s bellicosity, stubbornness, and vitriol also earned him enemies, especially after he led Socialist Party right-wingers in the bitter battle of words that would split the party at the 1912 national convention.

Another reason the Leader succeeded was that Milwaukee was home to an unusually robust socialist base, due to its many German immigrants. Most trade union members were socialists. The Leader’s audience was extremely loyal, in part because of its high quality and breadth of coverage, including sports, women’s news, health, drama, international news, and, of course, labor news. A “punchy” editorial page mixed political commentary with lighter fare. Editor John Work, who oversaw the paper’s editorial page from 1917 to its 1942 demise, attributed its popularity to its commitment to serving readers’ diverse interests. “It must not merely see the serious problems,” he said, “but also the lighter side of life.”157 Radical writer Joseph Cohen hit upon another reason for the Leader’s influence when he observed that a great newspaper is the product of a strong individual. “It is the expression of one man behind the pen,” he wrote in 1911. “To speak of a committee or a board of managers editing a paper is a contradiction in terms, even where the paper is the organ of a party.”158 Berger oversaw a strong stable of socialist journalists, including at times editors Algie Simons, Ernest Untermann, Ameringer, and Frederick Heath, and contributor Carl Sandburg. Berger’s wife, Meta Schlichting Berger, also was deeply involved behind the scenes and in the local Party.

The Leader was instrumental in city Socialists’ political success. The Social Democratic Party could blanket the city with a hundred thousand circulars in twenty-four hours. Its “bundle brigade” of men and boys canvassed the final four Sunday mornings before every election, distributing literature in English, Polish, and German. When socialists elected their entire ticket in 1910, including Berger as the nation’s first Socialist congressman, the national press flocked to Milwaukee. The positive coverage attributed the party’s success to Berger’s leadership and organization. He personified the adage that power of the press belongs to he who owns one.159 The Leader championed its editor in chief, whom a headline called “The Dynamo of the Socialists.” One of Berger’s first bills sought an old-age pension, precursor of social security.160 Although he lost in 1912, through the Leader, Berger remained a conservative force—some would say a negative one—in socialist politics.

The declaration of war in Europe in summer 1914 put the Leader in a conundrum. A native of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Berger tried to appear neutral. Nonetheless, the Leader could not resist blaming the British for the deaths of 1,198 passengers aboard the RMS Lusitania, which a German submarine torpedoed off the Irish coast in May 1915 on the grounds that the ship’s cargo contained munitions. German readers still faulted the Leader as pro-British, while disapproving socialist readers considered it pro-war. Advertising and circulation dropped to just above forty thousand by 1917. As the United States drew closer to joining in, the Leader’s antiwar stance threatened to torpedo the socialists’ most successful English-language daily newspaper.

The Chicago Daily Socialist’s Experiment in Collectivity

Only one English-language socialist daily newspaper’s circulation ever topped six figures, and that bubble burst in less than seven months. The Chicago Daily Socialist is a case study of the overwhelming odds against a radical periodical succeeding in a capitalist market—even when its commercial competition is eliminated, as historian Bekken has discussed.161 The newspaper’s difficulties reflected larger questions about the relationship between the Socialist Party and its press. It emerged from a daily campaign sheet published by the Chicago Socialist Party’s moderate weekly Chicago Socialist during the last two weeks of the 1906 election and edited by rebellious Chicago newspaper scion Joseph Medill Patterson, a recent convert to socialism. The weekly had changed its name in 1902 from the Workers’ Call, which Algie Simons and SLP members had created in 1899. ISR editor Simons and May Wood Simons signed on to assist Patterson. After the election, the weekly reinvented itself as the four-page Chicago Daily Socialist. Simons succeeded Patterson as editor, which he juggled with his ISR duties over the next two years until Kerr fired him. The Simonses produced early issues by candlelight on the third floor of the only print shop in the city that would publish their radical newspaper.162 The daily hired several reporters and contracted with the United Press wire service but counted on readers to literally make it their newspaper.163

The Daily Socialist’s experiment in collectivity demonstrated radical journalists’ axiom that the press belonged to the people. Editors stated in its first issue that they expected the local party’s thirty thousand members to contribute editorially. The idea of thirty thousand editors amused the mainstream press, but the newspaper claimed, “Every day a large number of letters come to the editorial office from every section of the country giving suggestions, news items, clippings, etc.” Volunteers included well-known journalists like Russell, who donated articles “merely for the sake of speaking what they wished.”164 Labor stories dominated editorial columns, which also featured politics, sports, women’s news, human-interest stories, cartoons, and socialist news that ranged from local party meeting notices to developments on the other side of the world. Simons scholar Robert Huston notes, however, that relatively little Chicago news appeared, indicating the reader-reporter experiment was less than a success. “The basic criterion for selection of news items seemed to be their contribution to the ridicule of the capitalist system,” Huston writes.165 The gradualist newspaper’s contemporary critics included Debs, who scorned its alleged catering to AFL craft unions. The Chicago Socialist supported labor materially as well as editorially. In 1910, for example, when Chicago garment workers followed their New York sisters onto the picket line, the newspaper imitated the Call by publishing a strike edition that raised $4,000 for them.166

As at the Call, a committee managed the Chicago daily. The Workingmen’s Publishing Society and its five-person board of directors was an even more fractious venture in collectivity than the WCPA. After the Socialist Party of Chicago local had donated its weekly to the cooperative venture, it realized, aghast, it also had lost editorial control of the daily published in its name. The local waged a protracted but unsuccessful battle to regain control, which drained resources and energy. In a familiar scenario, the society juggled stocks, bonds, subscriptions, donations, and a smattering of advertisements to keep the daily financially afloat, according to Bekken.167 Millionaire party member William Bross Lloyd bailed it out more than once, and Julius Wayland donated funds.168 Engdahl, who replaced Simons as the daily’s editor in 1910, recalled, “It was always kicking death through financial starvation.”169

The Chicago newspaper strike of spring 1912 looked like the struggling socialist newspaper’s financial salvation. When Chicago Examiner publishers locked out striking union pressmen, all other newspaper unions, save the printers, joined in a sympathy strike. Even newsboys refused to sell the struck newspapers. “They were the real soldiers of the labor war,” Engdahl recalled.170 Police arrested striking teenage newsies on disorderly conduct charges and beat them, according to ISR. Many unions imposed severe fines on anyone reading a scab paper. Although “finks” sold capitalist papers protected by police, their circulation plummeted.171

The Daily Socialist leaped in to fill the void. Renamed the Chicago Daily World, it ballooned to three hundred staffers and increased to twelve pages, while pumping up circulation from some thirty thousand to more than three hundred thousand combined daily in morning and evening editions through May and June.172 Engdahl stated it “expanded in a night from a crippled, four-page, one edition sheet with hardly a dozen thousand circulation, into both morning and afternoon publications, each with several editions.”173 Simons took a half dozen of the Milwaukee Leader’s best staff, including editor Chester Wright and cartoonist Gordon Nye.

Unfortunately, newsprint, ink, and payroll costs skyrocketed along with circulation. Big advertisers, such as department stores, didn’t follow readers to the Daily Socialist. The small, overworked printing press had to be replaced, so the society borrowed $60,000 from the Pressmen’s Union. Circulation settled at around one hundred thousand when the strike ended, but debts piled up. The directors borrowed another $45,000 from a partnership of lawyers and bankers, placing their socialist daily at the mercy of capitalists. By the end of 1912, its debt exceeded $120,000, forcing the society to declare bankruptcy.174 The sheriff nailed a notice to the building, and the linotypes stopped. Squabbling did not stop with the Daily’s demise on December 4, 1912; an embittered Engdahl charged it “was choked to death in a local factional struggle,” while the ISR said, in effect, good riddance: “For years the Daily has paralyzed the Socialist party of Chicago.”175 The Wobblies’ Industrial Worker commented the daily left “only bad odor and a train of unpaid bills.”176

Conclusion

Urban socialist dailies had a tough time competing with the diverse contents of commercial dailies thick with ads from department stores and other businesses that did not patronize the anticapitalist press. The Call nonetheless found a niche in the New York media market by championing workers and their causes. Publishing daily did improve its ability to provide a voice for labor and the Socialist Party. The Call provided a robust challenge to political and economic hegemony and remains an important record of workers’ hard-won fight for decent pay and working conditions in the 1910s. One striking common feature of the socialist dailies is that so many social issues they addressed remain contested on a global scale today: child labor, gender inequity, reproductive rights, poverty, war, corporate greed, sweatshops, workplace safety, and media conglomeration. The Lower East Side sweatshops that the Call criticized are now replicated in Asia and Africa, one focus of the antiglobalization movement that is the online progeny of the radical press.

The Call and other dailies performed several social movement media functions. Reporters’ eyewitness accounts countered hegemonic media reports of labor actions as mob attacks. Beyond reporting, the Call was actively involved in strikes, a characteristic of social movement media. It undisputedly served as city socialists’ main source of information about socialist meetings, labor actions, lectures, party politics, and social events. Such timely events were more suited to daily journalism than the long theoretical tracts that appeared in magazines such as the monthly ISR. Call editors were content to largely cede to them the function of Marxist education. As the voice of the city’s Socialist Party, the Call helped elect a Socialist congressional representative and local office holders. Art and literature reviews supported socialist culture, which found a locus in popular events such as the Call’s annual picnic. Similarly, the spirit that infused the newspaper’s 1908 debut captured the sense of community a radical newspaper could create.

Sustaining community proved difficult, however, as indicated by lagging Call circulation. Perhaps the diverse New York media market offered too much competition for a socialist daily newspaper in English. While foreign-language socialist dailies offered immigrant communities strong senses of identity based on cultural and ethnic bonds, and trade union newsletters better targeted members’ interests, the Call’s broader and more diffuse audience proved more elusive. Further limiting its appeal was that the Call represented the city’s gradualist socialists, whose conservative brand of socialism could be easily appropriated by reformist journals. Discussions among its board and editors show not even they agreed on what exactly a socialist newspaper should look like.

The greater success of the Milwaukee Leader indicated a place for a socialist daily existed on the media menu. Perhaps the key was the iron leadership embodied in Berger. The Call’s struggles to publish a newspaper by committee and the collapse of the collective experiment in Chicago lend weight to that thesis. The Chicago Daily Socialist debacle is telling, because it was a microcosm of the radical press, which also struggled to define the proper relationship between the party and its press. Perennial conflicts between the Workers’ Publishing Society and the party local mirrored the national party’s exasperation with hundreds of independent socialist periodicals published coast to coast. The Socialist Party constitution had forbidden a national party-owned periodical to thwart an editorial dictatorship, but the ban created a void filled by the Babel of competing socialist periodicals.

None flexed more muscle than the Appeal to Reason. Urbanites Berger and Hillquit despised the swaggering homespun weekly. Their differences, along with the fate of Americanism radicalism, came to a head in 1912, but not before the Kansan colossus played a key role in a milestone labor trial that symbolized the struggle for the soul of America.