CHAPTER EIGHT

“THE BLACK MAN’S BURDEN”

RACE AND THE RADICAL PRESS

“If you are saving dying babies, whose babies are you going to let die?”

Soon after moving north from Atlanta in 1910 to edit the Crisis, the monthly magazine of the newly created National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, W. E. B. Du Bois joined Socialist Party Club Number 1 of New York City. The sociologist had been moving cautiously toward socialism for more than a decade. He grew up in a Berkshire Mountains village with all odds stacked against him as a mixed-race child of a poor, single African American mother. A keen intelligence and Yankee drive to excel helped him become in 1895 the first African American to earn a Harvard University doctoral degree. While studying from 1892 to 1894 at the University of Berlin, he attended meetings of the German Social Democratic Party.1 The thoroughly bourgeois young scholar, however, believed too many German socialists were part of the “anarchistic, semi-criminal proletariat.”2 A decade of researching pervasive racism back in the United States would pass before Du Bois voted for Eugene Debs in 1904.

Soon after moving north from Atlanta in 1910 to edit the Crisis, the monthly magazine of the newly created National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, W. E. B. Du Bois joined Socialist Party Club Number 1 of New York City. The sociologist had been moving cautiously toward socialism for more than a decade. He grew up in a Berkshire Mountains village with all odds stacked against him as a mixed-race child of a poor, single African American mother. A keen intelligence and Yankee drive to excel helped him become in 1895 the first African American to earn a Harvard University doctoral degree. While studying from 1892 to 1894 at the University of Berlin, he attended meetings of the German Social Democratic Party.1 The thoroughly bourgeois young scholar, however, believed too many German socialists were part of the “anarchistic, semi-criminal proletariat.”2 A decade of researching pervasive racism back in the United States would pass before Du Bois voted for Eugene Debs in 1904.

The newly minted professor’s groundbreaking 1899 study, The Philadelphia Negro—the first of ninety-four works he produced in his ninety-five years—enveloped modern surveys in historical context but lacked a sophisticated class analysis. During a dozen years as an Atlanta University professor, Du Bois’s views on racism changed dramatically as he delved into the Deep South’s oppressive social conditions. His observations led him to a class analysis that connected racism to capitalism. That analysis grew more critical as he moved from advocating black capitalism as the solution to racial inequality to condemning capitalism as the source of all human oppression. He steeped himself in American socialist works such as Robert Hunter’s Poverty, Jack London’s People of the Abyss, and Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle before declaring himself a “socialist of the path.” He called for nationalization of the railroads and many industries. In 1907, as editor of the new magazine, Horizon: A Journal of the Color Line, he encouraged African American readers to leave the Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln for the Socialist Party Debs. Socialism, Du Bois asserted in Horizon, was “the one great hope of the Negro American.”3 His 1911 novel The Quest of the Silver Fleece outlined a broad socialist vision centered on an alternative cooperative economic model based on southern black culture as a solution to American class, race, and gender inequity.4 Less than two years after joining the Socialist Party, however, he resigned from Local No. 1, in part because he wanted to endorse Woodrow Wilson for president, but Du Bois also had tired of the Socialists’ failure to incorporate blacks and its silence on labor racism. “The Negro problem,” Du Bois declared in the socialist New Review, on whose editorial board he sat, “is the great test of the American Socialist.”5

No aspect of the fractious radical movement was more contradictory than the radicals’ attitudes toward “the Negro problem,” the question of how to incorporate into American society 10 million African Americans who even most sympathetic whites believed incapable of full citizenship. This chapter will detail how radical press contents dramatically demonstrate the ambivalence and confusion endemic in the topic of race among radicals in the early 1900s. Eugene Debs offered heartfelt paeans to workers of all colors in the Appeal to Reason while publisher Julius Wayland supported segregation. The Industrial Workers of the World united black and white lumber workers in Louisiana, but Industrial Worker published cartoons that depicted black men as buffoons. The Masses lashed lynching while Wilshire’s published racist rants. One contributor told International Socialist Review readers in 1903, “As a race the negro worker of the South lacks the brain and the backbone necessary to make a Socialist,” while the next year the journal declared, “The historic mission of the working class is to destroy in its supremacy all classes, and to blend humanity into one homogeneous, fraternal whole.”6 The incoherence regarding race was the inevitable result of the fact that the radicals’ worker remained a white, male construct. The casual confidence in white supremacy exuded by radical journals supposedly committed to egalitarianism also reflected the insidiousness of American racism. Marxian economic determinism as the root of all evil further blinded radicals by reducing racism to merely a symptom of class.

The term “Progressive Era” seemed a cruel taunt to African Americans as Reconstruction gave way to legal and extralegal racial oppression. The U.S. Supreme Court sanctioned segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, and blacks comprised most of more than sixteen hundred lynching victims from 1900 through 1918 counted in a NAACP study.7 Some frustrated blacks answered white radicals’ ambivalent invitation to join them in the class war. On the cusp of World War I, a black socialist periodical even appeared. Of course, no idea was more radical in the twentieth century than equal rights for African Americans, who had employed journalism to advance their cause since 1827, when free black Samuel Cornish founded Freedom’s Journal in New York. In the 1890s, African American journalist Ida Wells-Barnett used muckraking techniques to contest the legitimacy of the New York Times’s disturbingly “objective” reports on southern lynchings with her investigations into what she rightly termed white terrorism.8 The black press expanded by 1916 to some 450 periodicals, whose calls for voting rights, outrage against lynching, and campaigns against job discrimination filled the void in mainstream media. While its demand for racial equality was radical, save for few exceptions the black press did not contest American capitalism.

The Radicalism of the Crisis and Other Black Periodicals

Scholar Richard Digby-Junger argues the Crisis is one of four black periodicals that should be considered part of the early radical press. The others are William Monroe Trotter’s Guardian (1901–13), Marcus Garvey’s Negro World (1918–33), and the Messenger magazine (1918–128).9 The Crisis endorsed 1916 Socialist presidential candidate Allan Benson, for example, and in 1917 it published a radical “oath” for black voters, envisioning a cooperative commonwealth: “I will make the second object of my voting the division of the Social Income on the principle that he who does not work, be he rich or poor, may not eat; and that Land and Capital ought to belong to the Many and not to the Few.”10 The Crisis purveyed radical critiques of American capitalism through the prism of a distinctly black cooperative commonwealth.

“If we American Negroes are keen and intelligent we can evolve a new and efficient industrial co-operation quicker than any other group of people,” Du Bois wrote in 1917, “for the simple reason that our inequalities of wealth are small, our group loyalty is growing stronger and stronger, and the necessity for a change in our industrial life is becoming imperative.”11 Founders of the Crisis’s publisher, the interracial NAACP, included socialists William English Walling, Mary White Ovington, and Charles Edward Russell. Socialist Mary Dunlop Maclean, a former Times feature reporter, signed on as managing editor in 1911, which enhanced the magazine’s socialist outlook. Du Bois’s prewar positioning of race at the nexus of socioeconomic analysis placed him nearly a century ahead of scholars who addressed the issue toward the end of the twentieth century. Late in life, he parsed global oppression in a word: “Empire.” “The domination of white Europe over black Africa and yellow Asia, through political power built on the economic control of labor, income and ideas,” he explained. “The echo of this industrial imperialism in America was the expulsion of black men from American democracy, their subjection to caste control and wage slavery.”12 Du Bois made important contributions to radical discourse through his critiques of the lackluster Socialist record on race and trade unions’ exclusion of blacks.13

Trotter’s Guardian is notable among Digby-Junger’s journalistic quartet for breaking with Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T. Washington’s accommodating approach toward racism, a critical step toward formation of the twentieth-century civil rights movement. Garvey’s Negro World exerted most of its influence beginning in the early 1920s, when it sold more than two hundred thousand copies weekly. Garvey was a master printer in Jamaica who brought his Universal Negro Improvement Association to the United States in 1916. He called for black Americans to return to Africa to create a new society. Negro World and the Messenger were part of a vibrant black press revival that followed Washington’s death in 1915, grew more assertive during World War I and, according to historian Theodore Kornweibel Jr., flowered in the 1920s into the “New Negro Journalism.”14 Their editors and readers were “New Crowd Negroes” whose postwar demands for racial equality branded them militant. Digby-Junger judges Negro World “the most consistently radical Black newspaper in early-20th-century America” and likens Garvey to socialist-editor predecessors: “Like German-American radical journalist Daniel De Leon, Garvey was a fanatic, an ideologue, and a teacher who used his newspaper not just to communicate ideas but to transform readers into adherents. His contention that Black nationalism was the only salvation against race genocide was as serious an ideological weapon as the 1886 Haymarket bomb. Like J. A. Wayland, Garvey also knew how to promote his publications, how to make them appeal to a mass readership.”15

The Messenger’s Call for Social Revolution

Yet only the socialist Messenger called for revolution against the United States’ basic political and economic organization; it billed itself as “the only magazine of scientific radicalism in the world published by Negroes.”16 The appearance of what Kornweibel terms the “self-consciously ultra-militant” Messenger in November 1917 inaugurated the New Negro Journalism.17 The magazine had originated eight months earlier as the Hotel Messenger, official journal of the Headwaiters and Sidewaiters Society of Greater New York. It became independent by the fall, when its pair of young, college-educated African Americans editors endorsed the Socialist city ticket.18 Despite Chandler Owen’s name on its masthead, copublisher A. Philip Randolph “was its soul and driving force,” according to Digby-Junger.19 Both belonged to the New York Socialist Party, soapboxing from Harlem to Wall Street and opening a party branch in Harlem.20 The Messenger’s second issue pronounced Du Bois and other Negro leaders old-fashioned “mental manikins and intellectual Lilliputians” too old to be reformed. The hope of race rested with new, more radical leaders, Owen concluded.21 The Messenger was a moderate socialist journal that supported political action, however, and by the 1920s embraced black capitalist enterprise. But in its early years during World War I, the Messenger supported bolshevism, direct action, and the IWW. Randolph penned at least one editorial blaming capitalism for lynching.22 The Messenger also campaigned for the release of Ben Fletcher, the only African American defendant in the mass IWW sedition trials in 1918, who was sentenced to ten years in prison.23

The Call called the Messenger one of the nation’s “most valuable and unique Socialist publications.”24 It noted the editors’ grasp of African Americans’ economic status, “complicated, as it is, by racial antagonism,” an editorial comment that veered from the Call’s usual insistence that the “Negro problem” would magically disappear when the cooperative commonwealth replaced capitalism. White socialists’ denial of race as a serious obstacle to universal brotherhood—and their blindness to their own deeply inscribed racism—goes a long way toward explaining the indifference of America’s most oppressed class toward socialism.25

The Socialist Party’s Stance on Race

The Socialist Party of America’s first official radical act in the white supremacist United States had been to welcome African Americans. One of its founding resolutions in 1901 invited blacks to join Socialists and promised them “equal liberty and opportunity.” Debs endorsed the resolution as “a vital part of the national platform.” The following year, the party forbade segregated locals. Socialism enlightened the racial views of many of its converts. “I had been indoctrinated with the notion that the whites were superior to the blacks; it was not long after I had studied the principles of Socialism that my attitude toward Negroes was reversed,” recalled native Texan George Shoaf. “When I became a full-fledged Socialist, every vestige of race prejudice was driven from my system.”26 Radical journalists certainly considered themselves unstained by race prejudice and uniformly condemned overtly cruel acts of racism. The Call, for example, published anthropologist Franz Boas’s paper arguing that no scientific evidence found Negroes biologically inferior to whites.27

No subject spilled more outraged ink than the terroristic wave of lynching largely condoned or ignored by the mainstream press. An appalled Call quoted the Anderson (South Carolina) Intelligencer’s editor’s jocular firstperson account: “The lynching took place at midnight and two hours later the big press was grinding out papers telling of the happy event.”28 Linking lynching to socioeconomics made it a natural target for anticapitalists. Wherever large numbers of blacks began to demand economic rights, the IWW’s IW stated, stories circulated that some negro “considered dangerous to the material interests of the industrial masters” had attempted to rape a white woman. When “sufficiently terrorized,” it observed, the blacks returned to work.29 The Masses printed this deadpan brief under the mordant headline, “Southern Humor”: “A seventeen-year-old Negro girl was raped by drunken whites, who entered her home and found her alone. Her screams brought her brother from the barn. He kicked in the door, fought the two whites, killed one of them, and fled. The aroused white community, being unable to find him, then lynched the girl.”30

In 1913, lynching provoked the Masses to call for Negroes to declare “race war.” From their vantage point in Greenwich Village cafés, the intellectuals viewed “the possibility of some concentrated horrors in the South with calmness, because we believe there will be less innocent blood and less misery spread over the history of the next century, if the black citizens arise and demand respect in the name of power, than there will be if they continue to be niggers, and accept the counsels of those of their own race who advise them to be niggers.”31 The radical press casually tossed about the “n-word,” but Max Eastman’s usage shows he recognized its derogatory meaning.

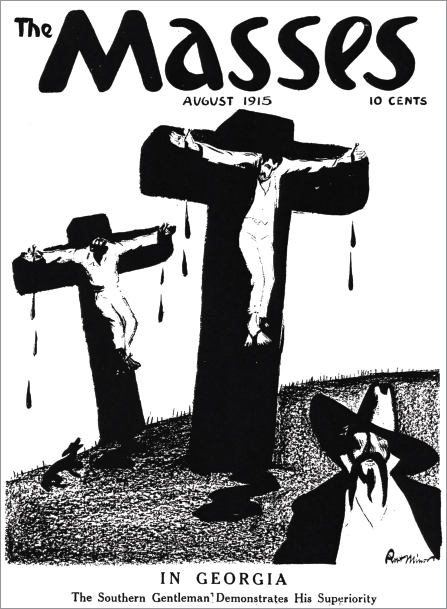

The Crisis initiated the use of shocking lynching imagery to “convert a shameful secret into a catalyst,” according to art historian Amy Helene Kirschke.32 Robert Minor drew a mob chasing a victim with a noose for a 1917 Blast cover, and he invoked the crucifixion in an even more damning illustration of lynching victims nailed to crosses for a 1915 Masses cover.33 Graphic photographs provided more potent visual rhetoric. In 1911, the Call published a photograph showing two dead men hanging from a tree in Florida, which later appeared in ISR. The victims were Tampa cigar makers on strike, possibly Cuban immigrants. Their description as “Working Men Lynched by Capitalists” epitomizes radical journals’ efforts to create a social movement identity by collapsing all social issues, including race, into a dichotomized class war.34

Reducing Racism to a Symptom of Capitalism

The exclusive focus on class, however, caused socialist leaders to deny the existence of racism. Three years after endorsing the “negro resolution,” in fact, Debs called for revoking it, stating, “We have nothing special to offer the negro, and we cannot make separate appeals to all the races.”35 An indication of his contradictory attitudes toward race, however, is that two months later he cited the resolution to decry racism.36 Yet, in 1908 Debs wrote in the Call: “There is no negro question outside of the class question…. [G]ive negroes economic freedom so that they may have the right to work and to receive and enjoy all they produce and the race question … will be known no more.”37 Such views meant that the radical press failed to fill for black readers most of its prime functions, including providing black socialists with a sense of group identity and community, voice, and a culture. Socialists were unable to conceive the consequences of skin color because they were so fixated on class. Even before the founding of the Socialist Party, ISR editor Algie Simons in 1900 believed “the ‘negro question’ has completed its evolution into the ‘labor problem.’”38 The Call followed the same reductionist line well into the twentieth century, arguing that the “Negro problem” was “much more a class question.”39 It stated, “We Socialists feel that the most important truth for negroes to grasp is the fact that their problem is the problem of all the exploited and disinherited.”40 This commentary contradicted ample evidence in its news columns of rampant racial violence. Hunter reported on Texas race riots; other reports described lynchings, blacks driven out of a Tennessee mining camp, a cabin torched, and more racial violence in Illinois.41

Radicals could be racist, but all agreed lynching was a heinous crime. This Robert Minor cover likens the death of Leo Frank, a Jewish man lynched in Georgia, to the crucifixion of Jesus. In Georgia: The Southern Gentleman Demonstrates His Superiority, Masses, August 1915.

A 1908 editorial boasted of the newspaper’s passive racial stance. The Call emphatically pledged it was “doing NOTHING to secure the negro vote.” Its message was a less-than-tantalizing inducement to potential black recruits: “Socialism is frank with the negro. It tells him that in the Socialist movement human nature is not different from what it is elsewhere.”42 Radical journals rarely challenged their white audience to consider its own tacit racism. In the Call, Debs categorized as class discrimination the 1906 Brownsville Affair, in which an entire platoon of black soldiers was dishonorably discharged. He equated the discharge with the kidnapping of William Haywood, a blatant example of socialist blinders, and refused to concede the soldiers were victims of racial discrimination.43 The Call’s lack of a black voice was striking.

Socialists placed on African Americans the burden of integration into the socialist landscape. An example is a 1901 Clarence Darrow speech before a Negro Men’s Forum published in ISR. Darrow (who was not officially Socialist) deplored racism and decried lynching, encroaching Jim Crow laws, and job exploitation. Yet he urged blacks to practically beg at the doors of the trade unions that banned them: “Now, trades’ unions have refused to admit you, but you ought to knock at their doors; you ought to join with them wherever you can; you ought to make it clear to them that their cause is your cause, and that they cannot afford to fight you because they cannot rise unless they take you with them, and when they are willing to take you, you are willing to go and to help fight the common battle of the poor against the strong.”44 An opponent of the party’s Negro resolution writing in ISR in 1904 was worse than condescending. “The negro, when he is intelligent enough to catch a glimmer of what Socialists are driving at, will come to us without a sentimental appeal,” he wrote.45 The Call’s northern, urban editorial writers, who relished denouncing southern industrialists for dividing white and black workers, breezily prescribed the remedy: “To cultivate among white workers and black a mutual feeling of comradeship in the struggle for political and industrial liberty.”46 Yet the socialist press’s racial condescension sabotaged its left-footed efforts to make comrades of African American workers. Debs’s vow to “awaken” Negroes was no less insulting to them than it was to white workers. His 1908 pitch in the Call for blacks to vote Socialist reeked of paternalism: “The Socialist party knows that the great mass of negroes are ignorant and it is the only party that refuses to traffic in that ignorance.”47

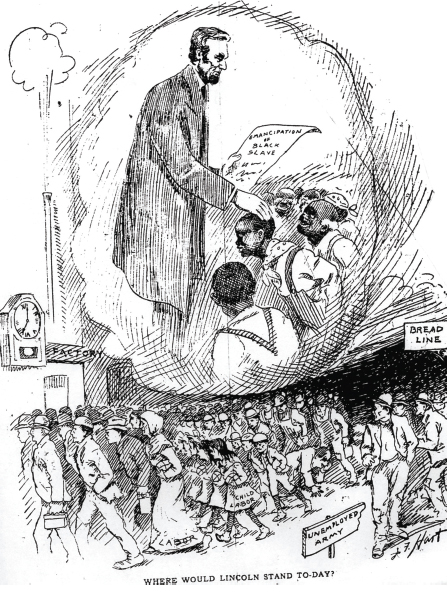

Radicals frequently likened factory workers to slaves, as shown in this cartoon of President Lincoln reading the Emancipation Proclamation. Where Would Lincoln Stand To-Day? Call, February 11, 1909.

Radicals were more eager to enlist the iconography of slavery for modern workers than they were to enlist black workers. The radical press equated “wage slaves” with the antebellum South’s chattel slaves. An example is a Call cartoon of factory workers, Where Would Lincoln Stand Today? Another is a Wilshire’s poem, “The White Slave.”48 In the ISR, Simons claimed northern textile mills thrived because cheap wage slaves were more docile than chattel slaves.49 The Call linked antebellum slaveholders to postwar southern capitalists who continued to exploit blacks.50 An IW editorial on the impossibility of family life for poor working men made this dubious comparison: “The negro slaves on the average plantation had their cabins and their homes, such as they were, and they changed wives no oftener than the modern divorce maniacs. On the whole the negro slave had the best of it.”51 H. Gaylord Wilshire sanguinely wrote that slaves “were like well-cared for animals on the farm.”52

Racism in the Radical Press

A major sticking point for numerous socialists who advocated economic equality was their distaste for “social equality” between races. A “Southern Socialist” wrote the Call: “Social equality means that whites would invite negroes to their homes, and that of course would result in marriage between whites and blacks…. Any man who knows the negro knows that is the all-absorbing, overpowering desire of every negro to possess a white woman … because Socialism is founded on the brotherhood of man, must it solve the negro problem in America by breeding a nation of mongrels?” An editorial on the same page refuted the author at length, however, and called upon Socialists to champion African Americans’ civil rights.53

Although historian Aileen Kraditor exaggerates when she claims radicals envisioned a uniform society with minimal cultural diversity, she correctly observes most socialists viewed the public and private spheres as distinctly separate—as did virtually all Americans, save anarchists. Socialists saw no contradiction between their calls for brotherhood and racial segregation. Socialist journalist Ernest Untermann told the 1908 Socialist Party convention: “I believe in the brotherhood of man, regardless of races, but … I am determined that my race shall be supreme in this country and the world.” His characterization of forced mingling as “emasculating” indicates the gendered undercurrent of radicals’ racial fears.54 An ISR correspondent from Montgomery, Alabama, stated that socialism is primarily an economic and industrial movement that should have “no direct concerns with questions of social equality.” Socialism’s sole duty to the Negro was economic justice. “If he proves as efficient a laborer as the white man,” this correspondent blithely explained, “he will get under Socialism, the same reward.”55

As part of their commitment to free speech and robust debate, socialist periodicals allowed southern racists to express their views. A 1901 ISR contribution was so noxious that Simons prefaced it with a disclaimer. In it, William Noyes explained socialism would solve the “Negro problem” because the black man “will cease to be a parasite” when he receives his share of what all produce together. Leisure and wealth will refine his coarseness and intemperance, “and he will cease to be a sexual menace.” Noyes grew exponentially offensive: “Physically the negroes are as a race repulsive to us…. His servility, obtuseness, showiness, superficiality, improvidence, laziness, excessive individuality, grossness, sensuality are everywhere obtrusive, while the opposite virtues of defiance, cleverness, taste, foresight, energy temperateness are rare enough to cause comment.”56

Simons offered no disclaimer, however, when a Memphis doctor reasoned in 1903 that Socialists must admit blacks, to stop their degeneration under capitalism because “it is our experience that it is the white man who is the father of the mulatto, while the black man largely fills the roll [sic] of the rapist.”57 A Texan socialist informed Call readers in 1911: “We don’t propose to have any one who knows practically nothing of the conditions here to bring discredit upon our movement by sending negroes and sentimentalists here to inflame the colored population with a desire for social equality in the name of Socialism.”58 In contrast, Theresa Malkiel, who lectured in the South on socialism, observed, “To the everlasting shame of our Southern comrades, they treat the negroes like dogs.”59 And the Call’s “Woman’s Sphere,” to which Malkiel contributed, bucked middle-class suffrage journals by opposing a move to restrict woman suffrage to appease Southerners. Bertha Howe reminded readers that socialism opposed race prejudice and championed human equality.60

Still, a number of socialist journalists were outright racist. Milwaukee publisher and editor Victor Berger was the most virulent. He wrote in 1902, “There can be no doubt that the negroes and mulattoes constitute a lower race.” He subscribed to the stereotype of the black rapist, and he argued capitalism had exacerbated Negro degeneration as the “savage instincts of his forefathers in Africa come to the surface.”61 Berger, who also favored excluding Asian immigrants, did not relent once elected to Congress, according to biographer Sally Miller. She wrote, “Those most unrepresented and oppressed of Americans were invisible to the only congressional representative of the workers of the world.”62

Racism infused Wilshire’s opposition to a Senate bill to award pensions to former slaves. “Growing racial insanity” and the rise in rape of white women by black men resulted from forcing African Americans “to compete against a superior race,” he claimed.63 Wilshire’s also asserted white child workers in southern textile mills led harder lives than those of black slave children.64 Straight-faced, Wilshire wrote that to avoid Negro domination the South must retain a property restriction on voting. Blacks were unfit to vote and incapable of governance, he asserted, pointing to Haiti. Despite his own observation that the rare Haitian Negros removed from poverty and educated went on to succeed in many fields, he failed to make the connection between environment and achievement. He also seemed blind to the class implications. Only the glimmer of socialism, he concluded, without his usual sense of irony, was staving off race war. “The Negro Problem is one of the many Problems of Capitalism that will automatically disappear with Socialism.”65

Kate Richards O’Hare also opposed social equality for African Americans. Her long-range plan for solving the Negro problem involved assigning them a section of the nation. Editors of her Rip-Saw article describing an outbreak of spinal meningitis in Georgia as “the negro’s revenge” attempted irony in its headline, “Only a Nigger,” but O’Hare was sincere when she described the black man as “vicious, depraved, ignorant and diseased, the product of our system, but his blood is red, he is a human being and he is bound with ties that cannot be severed to every other human being on earth, black and white.”66 The Rip-Saw distributed thirty-thousand copies of her 1912 essay, “‘Nigger’ Equality,” which assured segregationists “SOCIALISTS WANT TO PUT THE NEGRO WHERE HE CAN’T COMPETE WITH THE WHITE MAN.”67

In the eyes of the nation’s most influential socialist publisher, segregation was “natural.” Wayland not only opposed social equality but also supported segregation at on the job. In the cooperative commonwealth, he argued, social democracy followed majority rule. “If in a given workshop the majority prefer to have all white labor, how could the majority be said to govern if there were any power that could prevent them from doing it?” he reasoned. Racial segregation “being the natural tendency of publicly owned and operated industries, it will result, sooner or later, in the separation of the races and thus solve the race question.” He remained as confident blacks would not choose to work where they were not wanted: “This does not mean that the negroes be deported out of the country. It means they will naturally drift to places where they can find employment to live, among and with themselves. This will be the fittest way for them to survive and those who refuse to do it will naturally lose in the struggle for existence, which they would bring upon themselves. There need be no statute law making segregation imperative.”68

At the same time, Wayland, incongruously, was an outspoken supporter of black rights in the workplace. He approved of the New Orleans trades council’s threat to strike unless “colored bands” were allowed to participate in a big reunion of Confederate veterans. Wayland believed “this shows that the labor unions are getting at a great truth—that the colored man is an industrial factor, and as such must be taken into consideration in the effort to obtain the rights of the white working class.”69 As that rationale indicates, Wayland framed racial economic equality as a pragmatic benefit for whites, a view that informed his opposition to property qualifications aimed at keeping black men out of southern voting booths. “The poor whites vainly imagine that this is to keep the ‘nigger’ in subjection, … but they have yet to learn that it is to keep the poor trash, no matter what their color, in subjection to those who have property.”70 A key point here is that even though Wayland recognized southern politicians’ manipulation of “race hatred” to maintain power, he failed to grasp how segregation played into their hands.

The national party did reject segregation. Its refusal to grant Louisiana a charter because the state required separate black locals enraged many southern Socialists. In ISR, a New Orleans Socialist called for “optional locals” or “sublocals” for blacks, similar to those formed by some Polish, Italian, and Jewish comrades.71 One anonymous Socialist told Debs he would campaign against the party if it treated blacks equally. Debs, who defied southern social conventions by refusing to speak before segregated audiences, rebutted him at length in ISR. “Foolish and vain indeed is the workingman who makes the color of his skin the stepping-stone to his imaginary superiority,” he wrote.72 Although Du Bois had his differences with the fluctuating Debs, the Crisis editor praised his “manly stand on human rights irrespective of color.”73

ISR toughened its stance against racism after publisher Charles Kerr replaced Simons as editor in 1908. He launched an ambitious series by Jewish Socialist Isaac M. Rubinow, writing under the pseudonym I. M. Robbins.74 “The Economic Aspects of the Negro Problem” called race the fundamental divide of the twentieth century, a significant break from doctrinaire party declarations on the primacy of class. Rubinow’s thoughtful history of slavery, abolition, Civil War, Reconstruction, Jim Crow laws, and what he termed the reinstatement of white supremacy, filled hundreds of pages from February 1908 through 1910. The author exhibited an unusually keen understanding of the legal and extralegal conditions that kept southern blacks in bondage. “Not a single day passes in the life of the negro, that he should not be reminded in a more or less cruel way that he cannot enjoy all the civil rights of an American citizen,” he wrote in September 1908. African Americans are forced to live in restricted legal and social conditions, he asserted. Since most are proletarian, it behooved socialists to pay attention to them. He noted the paucity of discussion of black issues in the socialist press, and he labeled as usually prejudiced or simplistically sentimental the few articles on race that did appear. Rubinow argued strongly for increasing active party opposition to racism. Instead of issuing rhetorical promises about equality, he recommended the party call for removal of all legal restrictions upon African Americans and push trade unions to welcome them. And it should call publicly for social equality. The party, he stated, three years before Du Bois did, had a “sacred duty” to reach out to Negroes.75 Yet his June 1909 article, “The Negro’s Point of View,” included not a single interview with an African American.76

Hubert Harrison Exposes “The Black Man’s Burden”

The absence of a black socialist voice was filled by Hubert Harrison (1883–1927), “America’s leading Black Socialist” from 1911 to 1914, when the Danish West Indies native worked as a full-time organizer for the New York Socialist Party, served as an assistant editor of the Masses, campaigned for Debs, and initiated the Colored Socialist Club. Harrison addressed head-on the relationship between race and class that the Socialist Party ducked. He made major theoretical contributions by calling upon the party to support and recruit African Americans in both the right-wing Call and the left-wing ISR, which he persuaded to capitalize the word “Negro” as part of his campaign against white supremacy. (The Call would not.) “More than any other political leader of his era, Harrison combined class conscious and (anti-white-supremacist) race consciousness in a coherent political radicalism,” states his biographer, Jeffrey Perry. “Among African American leaders of his era Harrison was the most class conscious of the race radicals, and the most race conscious of the class radicals.”77 Harrison made the first Marxist analysis of race by a black radical. Perry points out that Harrison’s five-part series on Negroes and socialism in the Call at the end of 1911 anticipated by more than a year Du Bois’s New Review column that labeled “the Negro problem” the great test of American socialism.78 Harrison, in turn, was influenced by Rubinow.

Harrison’s spring 1912 two-part ISR article, “The Black Man’s Burden,” inverted the notion of Rudyard Kipling’s 1899 imperialist poem. His analysis of the political, economic, educational, and social burdens that white men placed on American blacks detailed untenable injustice. Negro tenant farmers were but one example. “The accounts are cooked so that the Negro is always in debt to the modern slave-holder,” Harrison wrote.79 The accompanying photograph of the business-suited, round-faced, intense young author reinforced the image of a self-possessed member of the New Negro Crowd. In his seminal “Socialism and the Negro,” in ISR’s July number, Harrison elaborated on his analysis of the Socialist Party’s duty to champion the Negro quest for racial equality “on grounds of common sense and enlightened self-interest.”80 His stillborn plans to start a Colored Socialist Club of Harlem at the end of 1911, however, demonstrated that African American radicals were not a monolithic block. When Du Bois objected to a separate black socialist organization, calling the voluntary segregation “absurd,” it quickly died.81 Like Du Bois, however, Harrison also grew disillusioned with the party. He criticized it in a letter the New Review declined to publish, and he opposed its expulsion of Haywood. The party suspended him, and he quit in 1914.82

New York’s new weekly New Review continued the racial discussion Harrison initiated with essays by Du Bois among others. Robert Lowie persistently challenged the ethnocentric concept of social evolution that ranked white, male society at the top of the social pyramid, and the NAACP’s Ovington expounded on racial inequality.83 She was among New Review contributors to a spirited exchange on racial prejudice.84 After Du Bois quit the party, he turned to the newly launched journal to address “Socialism and the Negro Problem.” Du Bois’s byline appeared again on February 1, 1913, above his challenge to socialists’ truncated explanation of racism. “I have come to believe that the test of any great movement toward social reform is the Excluded Class,” he wrote. “If you are saving dying babies, whose babies are you going to let die?” He asked: “Can the problem of any group of 10,000,000 be properly considered as ‘aside’ from any program of Socialism? Can the objects of Socialism be achieved so long as the Negro is neglected? Can any great human problem ‘wait’? … The essence of Social Democracy is that there shall be no excluded or exploited classes in the Socialistic state; that there shall be no man or woman so poor, ignorant or black as not to count one. Is this simply a far-off ideal, or is it a possible program?”85

Du Bois remained truer to socialist principles than many of the party’s card-carrying members, according to scholars Mark Van Weinen and Julie Kraft. “Time and again, Du Bois tested the genuineness of socialist parties and programs by whether they regarded proletarian blacks and other people of color as equals.”86 In another New Review essay, he chided the party’s failure to recruit African Americans or challenge trade-union segregation. “The net result of all this has been to convince the American Negro that his greatest enemy is not the employer who robs him but his white fellow workingman,” Du Bois wrote, producing an unenlightened Negro labor force that was “distinctly capitalistic.”87

The IWW Press Promotes Interracial Solidarity

Of all radical organizations, the IWW most consistently practiced the racial equality it preached. When the Socialist Party rejected Harrison, he turned toward the IWW, as did thousands of other ordinary black workers.88 As the champion of unskilled labor, the IWW was the only radical group that actively sought to attract African Americans, who comprised some 20 percent of common laborers. While the AFL discriminated against them, the IWW employed a full-time “colored organizer” in the South.89 IWW literature addressing “Colored Workers of America” highlighted the shared interests of white and black workers in abolishing the wage system that made every man “a slave who sells himself to the master on the installment plan.”90

Solidarity and IW published scathing denunciations of racism. “The fight of the negro wage slave is the fight of the white wage slave; the two must rise or fall together,” a 1917 editorial stated.91 They asked readers to stop using the word “nigger.” “‘Fellow worker’ is the only salutation a rebel should use,” wrote Phineas Eastman, who organized black and white southern timber workers.92 Another organizer reiterated, “There are white men, Negro men and Mexican men in this union, but no niggers, greasers or white trash.”93 The southern timber workers’ newspaper, the Lumberjack, reserved racist epithets like “niggerscab” and “white trash” for nonunion members of both races.

Unlike socialist journals, the IWW acknowledged blacks faced more exploitation than whites because they were denied education, terrorized by lynching and rape, and routinely denied justice. Solidarity appealed to blacks to ignore owners’ attempts to divide workers. “For a generation … [t]hey have kept us fighting each other—us to secure the ‘white supremacy’ of a tramp and YOU the ‘social equality’ of a vagrant.’”94 Justice for the Negro—How He Can Get It was the title of one Wobbly leaflet. As the NAACP’s Ovington stated, “The I.W.W. has stood with the Negro.”95 Du Bois, while a critic of industrial unionism, respected the IWW “because it draws no color line.”96 According to Philip Foner, the IWW “is the only labor organization in American history never to establish a single segregated local.97 Nonetheless, one Solidarity contributor assured readers that integrating locals did not mean blacks and whites had to meet in the same hall.98 Although he probably reflected many members’ views, his statement was contrary to IWW policy.

“The IWW freely admits the negro, barring neither race, color nor creed,” IWW leader Haywood told ISR readers in 1916.99 An IW contributor wrote, “The Chinese, Japanese, or Negro worker has the same right to life, liberty (whatever that means) and the pursuit of happiness as any other worker.”100 A Wobbly told ISR, “We want every person engaged in industry, whether male or female, white or black, to have a voice in making the rules under which they must work.”101 Haywood contrasted the IWW’s welcoming attitude toward minorities to AFL discrimination against blacks, Asians, and other immigrants. Further, AFL apprenticeships revealed despotism, and its dues were prohibitive.102 IW stated, “This so-called labor movement has the nerve to call the negro a scab when he takes the only opportunity for employment that is offered to him.”103 The IWW walked the talk by organizing black and white dockworkers in interracial locals in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New Orleans.104

The IWW also actively encouraged solidarity among ethnic groups. Foreign-language periodicals were an important part of its print culture. In 1910, the IWW published journals in French, Japanese, Polish, and Spanish.105 As part of its mission to recruit workers of all nationalities to its international union, IW occasionally published non-English articles. The April 29, 1909, issue, for example, included the IWW preamble in Chinese. Another article was in German, and another in Italian. Chicago headquarters literature included “Why Strikes Are Lost” in Lithuanian and the report to the International Congress in Italian. La Union Industrial, “the only Spanish paper in the United States teaching Revolutionary Industrial Unionism,” operated in Phoenix in 1910.106 By 1913, it was joined by a second Spanish newspaper in Los Angeles, La Huelga General.107 In the East, Cultura Obrera served the IWW’s New York marine transport workers union beginning in 1913. El Rebelde, edited by revoltoso Aurelio Azuara, soon followed.108

The IWW’s Interracial Organizing in Louisiana

The most dramatic alliance between white and black workers was the IWW-organized strike of western Louisiana timber workers against the industry’s “backwoods totalitarianism” between 1910 and 1913.109 Timber, the state’s only industry, and its company towns, which mushroomed at the turn of the century, disrupted rural residents’ social and economic life and relationship with the forest.110 Wages were as low as $1.25 for a ten- or twelve-hour day. One state study found the lumber camps violated every labor law on Louisiana’s books.111 By 1910, sixty-three thousand men worked in the mills and piney woods, more than 60 percent of them African American. The many black workers who migrated from Gulf Coast sugar plantations had an unusually militant heritage, which included a Knights of Labor strike during the 1886 harvest. White timber workers, mainly local farmers, also resisted the assembly-line culture of industrial capitalism and the destructive nature of logging. “Mechanized logging was agriculture in reverse,” as historian James Green observes.112 Workers especially rankled at being paid in scrip, forcing them to trade at the overpriced company store.113

Populists first tilled the piney uplands’ fertile radical grounds. Socialists inherited their followers, and more than a third of the region’s residents voted for Debs in 1912. These rural southerners also received an education in the evils of capitalism from several socialist newspapers that enjoyed a large circulation in the region: the Appeal to Reason, National Rip-Saw, and Texas’s Rebel. “The radicals couched their revolutionary appeals in a Southern agrarian idiom which drew effectively on the discontent of a poor, uneducated rural people without resorting to racism,” according to Green.114 IWW organizer Eastman noted African Americans already possessed race consciousness because of their shared oppression. “It is not a hard matter to make the negro class-conscious,” he told ISR readers. “He is bound to be rebellious.”115 The unskilled, unorganized timber workers also were attracted to the IWW’s direct-action approach. Although Foner argues the IWW ban on politics hindered black recruitment, it would seem that since southern blacks were virtually disfranchised they would welcome an alternative to the ballot to effect social change. As one Wobbly pamphlet claimed, “The only power of the Negro is his power as a worker; his one weapon is the strike.”116

In 1910, lumbermen organized the Brotherhood of Timber Workers (BTW) to challenge the northern lumber barons they so despised. Haywood apprised ISR readers of the bitter strike that followed. Mill owners cut operations to four days a week to squeeze out the union; three thousand men lost jobs in eleven mills, which the owners closed immediately.117 Barely alive, the BTW affiliated with the IWW in May 1912, in part because the latter promised to finance a union newspaper. At the organizational meeting, radical New Orleans organizer and editor Covington Hall and Haywood found white and black members meeting in separate buildings, per police orders. Hall and Haywood persuaded them to move into the same building, where the pair declared that all or none would go to jail if police arrived. None did.118 The union’s mass meeting at the Alexandria Opera House later that month marked the first racially integrated public meeting in the city’s history.119 Union demands included $2 pay for a ten-hour day. In the ISR, Haywood praised the brotherhood’s interracial solidarity.120 Hall later recalled the timber industry’s failure to divide black and white workers. “We farmers and workers will have to stick together,” he quoted a black farmer. “So long as I have a pound of meat or a peck of corn, no man, white or colored, who goes out in this strike will starve, nor will his children.”121

Wobbly Journalist Covington Hall

Hall was another of the romantic poet-journalists drawn to the IWW like bees to honey. His unlikely résumé included a term as adjutant general of the United Sons of Confederate Veterans and a stint as assistant editor at Oscar Ameringer’s socialist Labor World. Ameringer recalled him as the best-dressed, handsomest man in New Orleans at the start of the twentieth century.122 The scion of the southern elite began his turn toward radicalism by age ten, when the sheriff auctioned his family’s heavily mortgaged sugar plantation in 1891. Historian David Roediger argues that Hall’s southern heritage shaped his rebel sensibilities. His Marxist take on the Civil War was that that northern industrialists invaded the South to capture an untapped market; to justify his radical call for racial unity, Hall summoned the southern myth of benevolent slavery.123 A southern gentleman’s manners surfaced in Hall’s call for issuing warnings of sabotage as the “manly and honorable way” to use the tactic, according to Roediger.124

Hall learned more about class struggle while tramping for jobs and reading socialist literature. He briefly belonged to the Socialist Labor Party before joining the IWW soon after its 1905 creation. These encounters led him to blame capitalism for fanning race hatred.125 By 1907, Hall had earned a reputation as an ardent advocate of racial integration and industrial unionism, partly by working with timber workers and an interracial group of New Orleans dockworkers during a 1907 strike. Ameringer’s experience working with Hall in New Orleans convinced him that blacks were intelligent and good strikers. It inspired him to argue for “a class-conscious politics that would unite black and white working people.”126 The black dockworkers published the Republican Liberator, whose motto was “Justice for All Irrespective of Race or Condition.”

Wobblies recited Hall’s verse in the hobo jungles, and it appeared throughout the radical press.127 Ameringer called him the “poet of forgotten men.”128 Many of his verses describe Jesus as a hunted radical.129 “The common thread throughout all Hall’s Miltonesque and devilish tributes is an emphasis on rebellion,” according to Roediger. Racial paternalism laced his dialect-laden poems about African Americans. Yet, as Roediger points out, his respect for primitivism aligned his best poetry to the racially self-conscious writing of such black civil rights pioneers as Du Bois and Paul Robeson.130 He also imbued his primitivism with a socialist flare, as in these lines:

I’d like to be a savage fer a little while agen,

En go out in the forest where there ain’t no businessmen;

Where I’d never hear the clatter of their factories and things,

But just the low, soft buzzin’ uv the hummin’s crimson wings.131

Hall’s journalistic talents came to the fore when three union men and a guard were shot dead at a Grabow sawmill rally on July 7, 1912, in what the strikers called a company ambush. Fifty-eight union members were confined to the Lake Charles jail on charges of conspiracy to murder the guard. Hall’s first task was to issue a defense bulletin condemning the horrific jail conditions, which he sent to four newspapers. To his surprise, the Houston Chronicle put it on its front page. “A roar of anger went up in Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas and Oklahoma,” Hall recalled. “Never before or since have I seen such solidarity of labor.”132 Every Louisiana union supported the defendants. Throughout the trial, Hall distributed the weekly defense bulletin, mailing bundles to trusted men who handed it out across western Louisiana and eastern Texas. The judge threatened but did not follow through on charging Hall with contempt of court over one of the bulletin’s many satirical bromides. Hall and union secretary Jay Smith also filed reports for Solidarity.133 In ISR, Hall took the trial as an opportunity to urge northern blacks to join the One Big Union.134 IWW publicity played no small role in the October 31, 1912, acquittal of all defendants.

Hall became editor of the long-promised Lumberjack on January 9, 1913, to support the beleaguered strikers. It scrambled to provide the IWW version of more violence in Merryville.135 When the American Lumber Company blacklisted fifteen white men who testified in the Grabow trial, twelve hundred white and black members of the weakened union went on strike. They sang Wobbly rebel songs when jailed on frivolous charges and stuck with the strike when released. Merryville officials, lumber company guards, and police, however, combined to quash the strike and kick the strikers out of town. Their strategy included importing African American scabs, whom Eastman was sure only needed a little “union propaganda” to turn them.136 IW addressed Louisiana blacks in page-one appeals that explained industrialists encouraged white supremacy to divide and conquer black and white workers.

Historian Merl Reed’s comparison of three newspaper accounts of events in Merryville offers a case study of how radical media can counter dominant media. The Alexandria Town Talk reported from ninety miles away that the timber workers’ headquarters “were very quietly visited” on February 19, 1913. The unnamed visitors neatly packed up their belongings and their soup kitchen and shipped them to an IWW office. Town Talk reported, “There was no violence.” The American Press in Lake Charles, forty miles away, described citizens tearing down and burning the union soup shack. More than two thirds of the town’s three hundred union men, their wives, and children followed an order to leave town.137 The IWW Lumberjack’s account bore the headline “Class War in Merryville.”

“Men, born and raised in Louisiana, have been beaten, shot and hunted down as though they were wild beasts,” Hall wrote.138 The Lumberjack’s February 27 account described beatings and shootings by some three hundred drunken, gun-toting “scabs” that roamed the streets. “Some one asked about the law in Louisiana. Dr. Knight [leader of the Good Citizens League and company physician] pounded his chest and said: ‘This is all the law we want.’”139 Affidavits by two BTW members corroborated beatings. Besides harnessing local political and police power against the workers, the lumber companies used their financial clout to silence the IWW. At the end of March, the Alexandria print shop refused to print the Lumberjack, under orders from lumber owners who threatened to withdraw their patronage.140

Although the IWW’s Eastman believed the episode marked a big step toward the One Big Union, the Merryville story did not end happily. The strike collapsed in June, spelling the end of industrial unionism in the piney woods. Prosperity and suppression during World War I destroyed any remnants of Louisiana radicalism. Historian Grady McWhiney believes the IWW made a critical mistake by refusing to admit sharecroppers because they “owned” property.141 The short-lived Lumberjack was succeeded by the Voice of the People, which began July 17, 1913, in New Orleans, also edited by Hall, who moved it to Portland, Oregon, in July 1914, where it soon disappeared. Hall later published Rebellion (1915–16), a monthly radical magazine subtitled Made Up of Dreams and Dynamite.142

The IWW’s Spanish-Language Press

The IWW also organized Mexican and Anglo miners. Its Spanish-language newspapers, La Union Industrial in Phoenix and El Rebelde in Los Angeles, “exercised a key role” in educating Mexican miners about industrial unionism on both sides of the border, from Arizona’s Black Hills snaking south through the Sonoran Desert.143 Those distant periodicals were no match for southeastern Arizona’s Bisbee Daily Review, instrumental in the largest single incident of vigilantism in U.S. history. The July 12, 1917, front page carried the Cochise County sheriff’s warning to women and children to stay off the copper boomtown’s streets that day.144 Since late June, about half of some four thousand miners had gone on strike, ten times more than belonged to the IWW, against Phelps Dodge Corporation, owner of both the town’s lucrative Copper Queen mine and the Daily Review. Mine companies commonly published or held financial interests in Arizona newspapers, and events in Bisbee proved their worth. From July 1 through July 11, 1917, the Daily Review produced twenty anti-IWW editorials. A July 7 page-one cartoon branded the IWW part of a German plot to incite rebellion, and the Review appealed to patriotism to stop the IWW menace to the war effort. Rumors about stockpiled dynamite flew, although the strike was peaceful.

Race was a key factor in the strike. Historian Phil Mellinger argues the Bisbee deportation was one result of “concerted counterattacks by corporate and political powers against the potent, ethnically unified work force” of Anglo and Mexican miners that had been growing in Arizona since 1915.145 By 1917, more than five thousand Mexicans belonged to American IWW locals, lured by its commitment against the mine industry’s discrimination against Hispanic workers.146 Of Copper Queen miners, 13 percent were of Mexican descent; one strike demand called for abolishing company policy that restricted them to the lowest-paying jobs.147 With rifle bursts from the Mexican Revolution practically echoing in the border town, Bisbee officials and mine owners eyed striking Mexicans as dangerous revolutionaries. The many Austrians, Croats, and Slavs workers also were suspect. Mellinger faults IWW headquarters for failing to send requested literature in foreign languages to help unite Bisbee’s diverse immigrants during the strike. The Los Angeles Mexican IWW local refused a request to move El Rebelde to Phoenix, further hampering communication.148 These shortcomings indicate the IWW lacked the infrastructure to turn its interracial rhetoric into meaningful direct action. The Phelps Dodge deportation, however, highlights the near omnipotence of corporate powers over workers.

While newsboys slipped the Review under doors on July 12, Phelps Dodge ordered the local Western Union to shut down its telegraph wires. By mid-morning, an armed posse of two thousand men had rousted from their beds more than two thousand strikers and sympathizers and a few women and children. One man who refused to go was shot dead in his bed, but not before he shot and killed one of the posse. The posse marched prisoners at gunpoint several miles to a baseball park, where 1,186 men who refused to sign a pledge to return to work were loaded into railroad cattle cars that dumped them at a New Mexican desert hamlet.149 The roundup netted a disproportionate number of Mexicans—268, followed by 167 Americans, 82 Finns, 67 Irish, 40 Austrians, 35 Croatians, and men from some twenty other nations. The Bisbee Daily Review enthused, “It was a blow at traitors, spies and anarchists that will make this clique tremble everywhere west of the Rocky Mountains.”150

Mainstream media nationwide were equally indifferent at best to the flagrant violation of civil rights.151 Only the radical press and a few reform magazines such as the Nation seemed concerned by the unprecedented assault on civil rights.152 “The present administration is completely ignoring the crimes of Bisbee,” Solidarity stated.153 The newspaper, by then edited by Chaplin in Chicago, published several lengthy accounts. The IWW local’s press committee filed a lengthy report for the July 21 issue, followed by another datelined from the New Mexico deportation camp the next week, which emphasized the deportees’ solidarity.154 Solidarity published a front-page cartoon that likened the deportation to German atrocities in Belgium, which Boardman Robinson replicated in the Masses in September.155 A Solidarity editorial revealed the IWW’s grandiose view of itself when it categorized the deportees with some of history’s most famous martyrs. “Did the burning of martyrs successfully inhibit the rise of primitive Christianity?” it asked. “Did the Boston massacre thwart the aims of the American Revolution or the killing of John Brown and his sons stop the liberation of the chattel slaves of the South?”156 Appeal to Reason decried the “industrial despotism” that controlled the town “in utter defiance of American laws and the rights of American citizens.”157 Although a presidential commission concurred several months later, the Bisbee deportation made it clear that wartime had created conditions for legitimizing the IWW’s extermination.158 When mainstream media did protest, instead of the vigilantes they blamed the federal government for failing to offer a legal method for ridding communities of the IWW. The Chicago Tribune concurred, “It is obvious that we must strengthen our laws and stiffen our prosecution of this kind of treachery.”159 The contrast between mainstream and radical press commentary illustrates the important role of an alternative media in challenging dominant hegemony. A century later, few Americans would defend authorities’ flagrant abuse of power at Bisbee.

The Anarchist Analysis of Racial Oppression

Anarchist journalists offered a more sophisticated analysis of the “Negro problem” than the socialists’ reductivist collapse of racism into a symptom of class conflict. “It will be solved like other social problems: through a clearer conception of underlying causes, better understanding of necessary racial difference, mutual appreciation, and solidaric feeling,” a 1908 Mother Earth essay stated. The magazine cited racial oppression as evidence of the futility of government and law. “The Civil War, though it abolished black chattel slavery, completely failed to emancipate the negro,” wrote editor Alexander Berkman, and laws codified black inferiority. “To-day we realize the crying need of a new proclamation of independence, of economic emancipation.160 In 1909, Mother Earth ran the ISR series by Rubinow on economics and the “Negro problem.” The magazine’s solution to racial discrimination remained as vague, however, as other amorphous anarchist pronouncements on the ideal society and offered no practical guidelines for achieving racial unity.

The magazine did frequently assert its opposition to racism in its acerbic “Observations and Comments.” Mother Earth’s Russian Jewish publisher and editor effortlessly drew a parallel between St. Louis’s 1910 race riots and Russian pogroms against Jews.161 They observed that racism was not limited to the South. “Few white people in this enlightened land have risen to the level of recognizing in the negro a fellow man, a social equal,” the section noted in 1909. “Even some radicals are not entirely free from this most stupid of prejudices.”162 The Blast celebrated black resistance, which publisher Berkman found more interesting than racial prejudice.163 Other anarchist journals frequently attacked racism, including the Home colony’s Demonstrator. Few African Americans identified as anarchists, but an exception was publisher Lucy Parsons, who has been called the “most prominent black woman radical of the late nineteenth century.”164 The widow of executed Haymarket scapegoat Albert Parsons was partly African American and Hispanic, although she did not advertise her racial heritage. But as publisher of the Liberator (1905–06), she denounced violence against African Americans.165

Racist Stereotypes in Radical Visual Rhetoric

Although most radical periodicals denounced racism, most (except the sober anarchists) also published jokes and cartoons that traded on deeply inscribed notions of white supremacy.166 Art historian Donald Dewey suggests that cartooning’s greatest historical impact in the late nineteenth century was its dissemination of racial and ethnic stereotypes that spilled into the twentieth century.167 “White artists, even in journals sympathetic to issues in the black community, did not treat African Americans with respect,” observes Kirschke.168 The disrespect extended to the radical press. Blacks usually were absent from radical visual rhetoric, but illustrations that did appear usually categorized African Americans as “other” and often were derogatory. They associated blacks with none of the empowering qualities that social identity theory posits are requisite for building a social movement’s group identity. IW even occasionally succumbed to the era’s ubiquitous racist humor.169 As Kraditor observes, a gap existed between IWW “members’ attitudes and official theory” regarding race.170

And in the Masses, Kirschke states, “African Americans were shown with respect one month and as grotesque caricature the next, sometimes in quite vicious images.”171 Insults sometimes seemed unconscious. Sloan, for example, intended only to comment on the dire lives of southern mill workers in a sketch of wraith-like whites trudging to a factory under the eyes of a black boy who eats a watermelon—the stereotypical symbol of black indolence. Titled Race Superiority, its social satire relies on an inversion of the idea that blacks are inferior to whites.172 Masses artist Stuart Davis’s sketches of everyday African American life, however, won praise from black poet Claude McKay as “the most superbly sympathetic drawings of Negroes done by an American.”173 Yet a Call correspondent accused Davis of deliberately ridiculing African Americans.174 When a reader complained in 1915 that the Masses’s cartoons “depress the negroes themselves and confirm the whites in their contemptuous and scornful attitude,” a defensive Max Eastman replied the images reflected the magazine’s commitment to “realism.” He acknowledged the cartoons represented “this conflict between the aims of propaganda and the aims of art which is ever present to our editorial board.”175

Cartoonists’ affinity for paradox often relied on unconscious racist assumptions. A 1914 cartoon in the ISR, for example, depicted an African in tribal dress scanning newspaper headlines about the European war. He says, “Ugh! The dirty heathen!” The joke, of course, is the black man is supposed to be the dirty heathen.176 Leslie Fishbein observes that Masses artists often emphasized the comic aspects instead of political realities of their black subjects. A 1914 cartoon by George Bellows, for example, features an encounter between a wealthy white woman and a black woman she interviews for a job. When the potential employer asks her to elaborate on her “professional” experience, she replies in dialect, “Well, Mam—Ah takes yo’ for a broad-minded lady—Ah don’t mind tellin’ you Ah been of them white slaves.” Fishbein comments, “The sexual and economic victimization of the black woman are irrelevant to the humor of the sketch, which is more verbal and aesthetic than political.”177

Wilshire’s turn-of-the-century Challenge featured the blatantly racist cartoons of Frederick Opper, a popular syndicated Hearst cartoonist.178 The Call in its early years frequently depicted blacks as buffoons or savages.179 A 1908 cartoon shows a black boy after a rain contemplating a yard full of watermelons. The caption in dialect compounds the demeaning stereotype: “Weal, I declare! Ef dem watarmelungs mus’n a’ bus’ in de night a’ flood de patch!”180 Meanwhile, radical editors professed frustration with their failure to recruit blacks even as Debs made eloquent pleas for interracial brotherhood.181 It is difficult to imagine an African American warming to the Socialist Party, however, after reading this Progressive Woman joke about an African American after his first socialist meeting:

Old Darkey: Say brudder Samo, do yo’know w’at de ‘Mysterial Deception ob History’ am?

Brudder Sambo: No sah, I sho don’t.

Old Darkey: De ‘Mysterial Deception ob History’ am, when de capitalist hab extracted all ob de supper value from de poletarat wot dey hab left wont’ buy dere brekfas an dinnah, an why de poletarat will toe to go wid out eating am de “Mysterial Deception of History.”182

Conclusion

Such misguided attempts at humor offer a compressed explanation of black Americans’ indifference—if not hostility—to socialism. The radical press largely failed to provide people of color with the group identity and community a social movement needs to succeed. Radical press imagery often excluded or offended important constituencies. Some of the radical press’s visual rhetoric unwittingly contained disempowering messages that surely repelled possible converts. These characteristics reflected rather than created shortcomings in radical thought, which was inconsistent at best regarding race. The unprecedented efforts of the IWW to forge an interracial industrial union appear even more exceptional against the cultural backdrop of pervasive racism. The theoretical contributions of Du Bois, Harrison, and the unsung Rubinow in tying race consciousness and class consciousness make them vital links to the civil rights and Black Power movements. The contents of white radical journals, however, reveal that most radicals remained blind to the burdens of race, an inseparable part of black identity. The radical utopian vision remained a white man’s land.