CHAPTER TEN

SUPPRESSION

SILENCING THE RADICAL PRESS DURING WORLD WAR I

The spirit of heresy hunting and witch burning had come back to America.

Late on the afternoon of June 16, 1917, Emma Goldman was working in a room inside 20 East 125th Street in New York that doubled as the office of Mother Earth and the newly established No Conscription League. She had retrained her focus from championing birth control to combatting a new law requiring that by June 5 all men between ages twenty-one and thirty years register for the military draft. Alexander Berkman was upstairs working on the Blast, as fiercely pacifist as it was before the United States declaration of war on April 6. A number of volunteers also bustled about the building when eight men stormed inside.

Late on the afternoon of June 16, 1917, Emma Goldman was working in a room inside 20 East 125th Street in New York that doubled as the office of Mother Earth and the newly established No Conscription League. She had retrained her focus from championing birth control to combatting a new law requiring that by June 5 all men between ages twenty-one and thirty years register for the military draft. Alexander Berkman was upstairs working on the Blast, as fiercely pacifist as it was before the United States declaration of war on April 6. A number of volunteers also bustled about the building when eight men stormed inside.

“I have a warrant for your arrest,” a U.S. marshal told Goldman.

“I am not surprised,” she replied. “Yet I would like to know what the warrant is based on.” He produced a copy of Mother Earth’s June number. The cover cartoon condemned the draft. Ben Reitman’s anticonscription essay inside informed readers the average soldier lasted eight weeks in the trenches. The marshal flipped the pages to another article that described rallies conducted by Goldman and Berkman’s No Conscription League. On May 18, the pair rallied some eight thousand people who demanded the draft’s repeal; on June 4, another fifteen thousand protesters spilled from a jammed hall in which they spoke and onto a Bronx street singing “The Marseillaise” before hundreds of soldiers disbursed them.1 The Mother Earth article boasted the league had distributed one hundred thousand copies of the No-Conscription manifesto: “We will resist conscription by every means in our power, and we will sustain those who, for similar reasons, refuse to be conscripted.”2 Goldman readily acknowledged she was the author. She volunteered that she stood for everything in the magazine, which she had called her child since its birth twelve years earlier. Police arrested her. They climbed upstairs a few minutes later and arrested Berkman. Both were charged with obstructing the draft, in violation of the federal Espionage Act that had gone into effect less than twenty-four hours earlier.

Meanwhile, two police detectives and four deputy marshals rummaging through the offices found books by George Bernard Shaw, William Morris, August Strindberg, Maxim Gorky, and Frank Harris, among others. They seized everything, including a card index, bank- and checkbooks, and thousands of copies of Mother Earth and the Blast. When the police finished, they whisked the prisoners to the federal building. It was too late to arraign them that evening, so they locked them up in the Tombs.3

So began the most oppressive chapter of censorship in American history. The idea of workers manufacturing objects to kill fellow workers appalled the uniformly pacifist radical press. Its allegiance was to other workers, not the nation state. Labor radicals equated militarism with the state militia and private guards that pointed bayoneted rifles at them outside the factories and mines where they worked. American radicals decried rising militarism long before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of the Austria-Hungarian Empire, on June 28, 1914, triggered a lethal game of dominoes that would claim some 15 million lives. This chapter will trace how the radical press record of protesting war in general swelled into a desperate bid to keep the United States out of Europe’s Great War, triggering a brutal backlash from the federal government.

Pacifism in the Radical Press

Progressive Woman had proposed women create a “vast anti-war league” as early as 1909.4 The journal was among many radical periodicals that declared the Boy Scouts of America a ruse for militarists.5 Appeal to Reason branded the organization “the most sinister and diabolical attempt ever made, akin to the white slave traffic to debauch youth.”6 That same year the Call scoffed at “bourgeois peace societies” that failed to connect capitalism and war.7 Industrial Worker, inspired by general strikes tearing through France, reprinted a Walter Crane illustration of a French worker confronting a soldier with a question: Would You Kill Your Fathers, Brothers and Fellow Workers?8 H. Gaylord Wilshire theorized capitalists brew war to stem unemployment by harnessing factories to produce such “useless and unnecessary things” as weaponry.9 In 1913, from his vantage point in London, Wilshire presciently predicted in his fading journal that calls to patriotism would trump working-class self-interest. “If it were a case of sitting down and listening to the voice of reason, there would never be a German working man in favour of military expenditure,” he observed. “It is a question of the war lords talking about the glory of the Fatherland and arousing his tribal instinct.”10 Wilshire sided with his adopted homeland once war erupted.

Mother Earth pleaded vainly in August 1914 for European workers to stop the war by walking off the job.11 The magazine’s damning September cover illustration by Man Ray, future creator of Dadaism, combined iconic imagery of the crucifixion, the American flag, and prison into crude but powerful visual rhetoric against the carnage. The Masses made the point that war in the European citadel of culture obliterated Progressive Era claims about social evolution: in the Art Young cover, two apes read a newspaper headline that screams, “WAR!” The caption has one saying to the other, “Mother, never let me hear you tell the children that these humans are descendants of ours.”12 The anarchist Alarm also referenced Darwinism in a cartoon of two monkeys surveying the battlefield beneath their tree. One says, “I’m glad I haven’t degenerated into ‘MAN’!”13 Christian nations at war provided more fertile satirical fodder.14 ISR amplified the ominous portent of photographs that depicted deadly new machines in Europe by tacking onto them titles such as Latest Type Krupp Gun—This Murdering Machine Was Made by Workingmen.15 Young found his art inadequate to express his horror. He added text to a September cartoon that displayed a heavy hand instead of his usual light touch: “Since the declaration of war, there have been about five thousand cartoons picturing death on the battlefield…. I hope cartoonists will go on drawing pictures of the horrors of war. But war is only one big evil—and merely the result of a greater—the struggle for profits. Death lurks in every move made by the profit system.”16

Socialist journals’ initial faith in the German Social Democratic Party’s pacifism swiftly dissipated.17 A special Socialist congress in Switzerland also declined to declare a continent-wide general strike to stop the war. Each of the European Socialist parties supported its national government, shredding any vestige of international brotherhood. American workers likewise ignored New York socialist Meyer London’s suggestion that Americans launch a general strike in the munitions and food industries to disrupt the killing.18 Max Eastman tried to rationalize that war would hasten the social revolution.19 The Call scurried to absolve European socialists’ responsibility for their failure to stem the bloodshed. “There is no disgrace in failure when all power has been exhausted,” it editorialized.20 Mother Earth was tougher on Europe’s reform socialists. “We have no sympathy for these political cattle,” Berkman snorted.21 European anarchism also disappointed him, particularly Peter Kropotkin’s endorsement of Russia’s entrance into the war. “Its boasted internationalism, like that of the Socialists, has broken down,” he wrote.22 War discourse pushed the radical agenda off radical press pages. National Rip-Saw printed one hundred thousand copies of a special September 1914 “War Edition,” and the Industrial Workers of the World’s Solidarity mustered a special six-page antiwar issue on October 31, 1914.23 New Review devoted its October 1914 issue to the war in Europe, which practically consumed all future issues. Appeal military stories jumped from a miniscule less than a half percent through 1912 to 11.8 percent after.24

Radical Press Frames of the European War

Radical editors wrestled with how to frame the war. Instead of glorifying the fighting, the Call’s editorial page vowed to “provoke and stimulate serious thinking.” It optimistically claimed that events “portend the general breakdown of the capitalist system” and war “leads straight to the social revolution.25 Editors explained that war news dominated Call pages because its socialist perspective would win converts. The newspaper pointed out it printed news missing from the mainstream press. It made good on its promise to focus on war’s human toll instead of its glory. Call “staff correspondent” M. J. Phillips reported on thousands of Belgian babies lost during the flight from the German invasion.26 Jane Addams’s plan for women of the world to unite against the war won a page-one banner headline in 1915.27 Another byline of interest belonged to Dorothy Day, who worked as a Call reporter before she created the Catholic Worker.28 A 1917 letter offered a horrific first-person account of battle, purportedly from a Brooklyn youth, which began: “Jim, I’m writing this letter in a TRENCHFUL OF DEAD! And I’ve been here, digging and fighting, nearly a week.”29

John Reed sailed to France in 1914 to see the war for himself, followed by Eastman in 1915 and cartoonist Robert Minor in 1916. The philosophical Eastman found wartime Paris dull. The exception was when German zeppelins floated above the darkened City of Light, accompanied by the screech of fire trucks as searchlights and shrapnel lit up the sky. “It is their one great taste of adventurous war, and the Parisians love it,” Eastman reported drolly.30 A letter from Minor showed him as apt a reporter as an artist. Describing a train of wounded arriving in Paris by night, he wrote: “My luck was unusual, as they don’t want the public to see such things…. It looked as though the only part of the human body sure to be found on the stretcher was the head…. Here was a man with his eyes and nose shot off, there, one with his lower jaw gone, another with both legs and one arm off, asking me for a light, having become tired of waiting for his neighbor (a fortunate fellow with two arms and a leg) to solve the interesting problem of a patent cigar lighter.”31

Fresh from the Mexican Revolution, Reed traversed the front lines but also found war’s aftermath most compelling. He described the “quiet, dark, saddened streets of Paris, where every ten feet you are confronted with some miserable wreck of a human being, or a madman who lost his reason in the trenches, being led around by his wife.”32 Accompanying Reed was his married lover, the noted Greenwich Village salon hostess Mabel Dodge, whose dispatches from Paris to the Masses are among the earliest examples of women’s war reportage. Dodge pondered war through a feminist-pacifist lens. “Men like fighting,” she concluded. “There is no deeper meaning than that to be found in it, and there never has been any other.”33

Protesting “Preparedness” in Words and Imagery

Back in the United States, a “preparedness movement” touted by Theodore Roosevelt, bankers, and industrialists gained momentum throughout 1915. The May 7 sinking of the British passenger liner Lusitania by a German U-boat fueled the movement. The Call published a collage of alarmist headlines published by what it called, “The Hysterians,” led by the “Wearst” newspapers.34 Mother Earth coldly reasoned the passengers’ deaths were no worse atrocities than those perpetrated against Native Americans.35 The Appeal’s thousandth number, published January 30, 1915, featured a petition blank for readers to sign, urging President Wilson to disarm. By the end of the year, the Masses contained an anti-enlistment pledge form.36 Congress nonetheless vastly expanded the military by passing the National Defense Act of 1916. The ostentatious display of patriotism and militarism in New York’s Preparedness Parade that July reviled radicals, but they found themselves increasingly isolated as such spectacles stoked war fever.37 One casualty was the antiwar Rip-Saw, whose circulation shrank as war hysteria spiraled. When an exhausted Frank O’Hare resigned at the end of 1916, the Rip-Saw was renamed Social Revolution.38 The preparedness bandwagon grew louder. Besides producing arms and weapons, boosters clamored for compulsory conscription for all males.

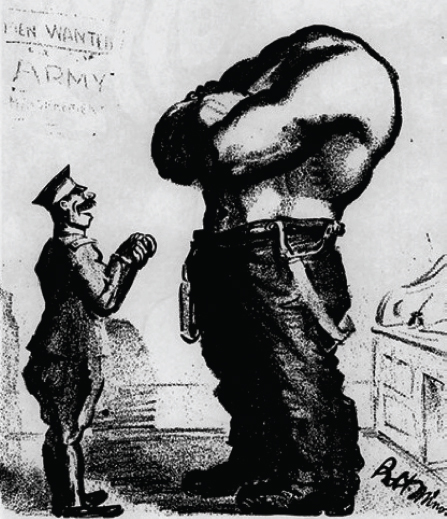

Wilson’s preparedness policy inspired a ream of antimilitary cartoons. Minor’s July 1916 Masses back cover, for example, has been hailed as one of history’s most powerful denunciations of militarism.39 Applying his trademark grease pencil, Minor sketched a behemoth, headless army recruit. All muscle and obviously no brain, the recruit is beheld by an army medical examiner, who exclaims, “At Last! A Perfect Soldier!” The radicals’ antiwar cartoons over the next several years perhaps are their most compelling, in part because they helped spell their publishers’ demises. Cartoons often sat at the center of government prosecutions of the radical press during World War I. The persuasive power of visual rhetoric so impressed the federal government it created a Cartoon Bureau under the umbrella of the Committee of Public Information, a public-relations bureau for the war headed by former muckraker James Creelman. Its most enduring product is the Uncle Sam “I Want You” recruiting poster painted by James Montgomery Flagg.

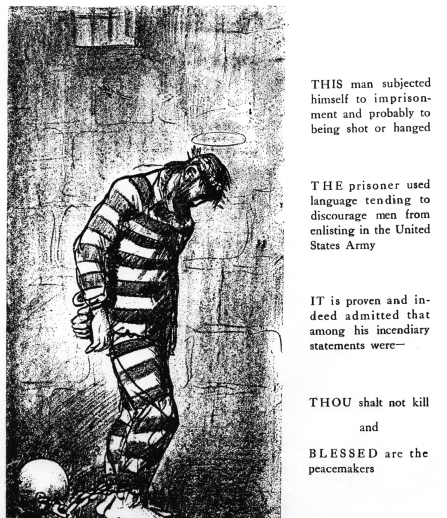

Another iconic image from these years is Boardman Robinson’s two-page Masses spread in which a firing squad comprising the warring nations’ soldiers executes Jesus.40 Radical opposition to the war often had a distinctly religious cast. The IWW’s satirical streak skewered the hypocrisy it perceived among the church, mass media, and members of the dominant class that framed the war as a Christian crusade. A forceful 1917 Blast cartoon portrayed Jesus in prison stripes, hobbled in a cell by a ball and chain. Accompanying text states he has been imprisoned for discouraging men from enlisting by stating: “THOU shalt not kill and BLESSED are the peacemakers.”41 Potent visual rhetoric portraying Christ as a pacifist versus ministers as warmongers sorely tested the nation’s commitment to free speech as it edged closer to war. Ironically, Christian Socialist editor Edward Ellis Carr was pro-war, a stand that forced the fifteen-year-old newspaper out of business in 1918 as socialists took sides.42

Robert Minor’s grease pencil cartoon for the Masses has been called one of history’s most powerful antimilitary images. At Last! A Perfect Soldier! July 1916.

In an eleventh-hour attempt to keep America out of war, on March 31, 1917, the Call produced a large antiwar edition, full of letters that supported or opposed U.S. entrance into the European chaos, indicative of how the war split the socialist movement. By the time the Socialist Party’s emergency convention opened in St. Louis on April 7, the United States already was at war.43 The Call’s endorsement of the convention’s 140 to 31 to 5 vote to oppose the war unwittingly mimicked crippling party divisions by quibbling at length over much of its phraseology.44 Many socialist journalists, including Robert Hunter, Allan Benson, John Spargo, William Ghent, Upton Sinclair, Graham Phelps Stokes, A. M. Simons, William English Walling, and Charles Edward Russell eventually broke from the party because of its antiwar policy. At the other end of the spectrum stood the estranged Wilshire, back in California after fleeing London in 1914. The former publisher led the “super patriots” in their denunciations of pacifists, even endorsing vigilante violence against war opponents.45

Like the familiar-looking figure above, radicals risked prison by opposing U.S. entrance into World War I. Untitled, Blast 2 (March 15, 1917): cover.

Freedom of Expression Is the First Casualty

The Appeal correctly foresaw that wartime’s “gravest danger” was the loss of free speech.46 Radicals’ rapture over the Russian Revolution, which deposed the czar in March 1917, further inclined hegemonic forces to silence radicals. Eastman rejoiced in the Masses and ISR that the equivalent of the IWW was running Russian affairs, an image sure to give politicians and capitalists nightmares.47 Berkman declared in the Blast, “The Russian Revolution is unquestionably the greatest event of modern times.”48 American authorities quashed antiwar meetings, confiscated newspapers, jailed radicals, and beat conscientious objectors. Police raided and temporarily shuttered the anarchist Alarm and Revolt in Chicago; Regeneración in Los Angeles; and the Spanish-language Voluntad and Bohemian Volné Listy, both in New York. The October–December 1915 and February and March 1916 issues of the Alarm were ruled unmailable under the Comstock law’s incitement clause.49 The periodical charged that the government intended to wipe out the radical press. “Every uncompromising voice is being silenced,” stated the caption below a cartoon depicting the Post Office’s fist slamming down on the newspaper.50

Postmaster General Albert Sidney Burleson wired the San Francisco office a special order to hold every issue of the Blast and submit copies to Washington, D.C.51 Postal inspectors held three consecutive issues, beginning in April 1916, ostensibly because they discussed birth control. In a perverse catch-22, the Post Office then proclaimed the newspaper ineligible for reduced second-class mail rates because it did not regularly appear at stated intervals. Berkman remained defiant. “Have we come to this, that any stupid Post Office clerk may decide what is or is not fit for the people to read?” he asked.52 The blatant suppression brought out the noblest side of the unbending Berkman. He called the Post Office’s suppression of a free press “one of the greatest crimes against the people.”53 Police had raided Berkman’s San Francisco office after a bomb killed ten people and injured forty more during a July 22, 1916, preparedness parade. Police found nothing incriminating but filed dubious charges against labor activists Thomas Mooney and Warren Billings. Berkman devoted the Blast to defending them. Although Mooney was sentenced to hang, Berkman’s campaign succeeded in pressuring the California governor to commute his sentence to life imprisonment.54 Berkman’s other obsession was the looming war.55 In January 1917, while Berkman was visiting New York, private detectives overseen by an assistant attorney general raided the Blast office. They took manuscripts, subscription lists, cartoons, files, and Berkman’s letters.56 Again, no charges were filed. That spring he moved the magazine back to offices above Mother Earth in New York, while the Wilson White House mulled new strategies to silence such raucous critics.

On the eve of the country’s entrance into World War I, the U.S. Army War College proposed an elaborate system to censor all printed matter. The American Union against Militarism labeled the system “exceedingly dangerous,” especially for the “really independent press.” It would not only ban criticism of the war effort but also require the censor’s permission for any discussion of the war. “It is aimed, not at the enemy, but at the complete control of public opinion in this country in time of war,” ISR charged.57 The bill was defeated. Mainstream publishers won another fight against strict censorship when CPI director Creelman issued voluntary censorship guidelines.58 The Wilson White House discovered a less incendiary way to silence press critics, one that avoided the odious term “censorship” that so incensed the powerful press barons. “Sedition,” the Call stated. “A new word for those in this generation.”59

The 1917 Espionage Act

Section 3 of the Espionage Act that Congress enacted on June 15, 1917, prohibited conveying any matter that hindered the U.S. war effort or encouraged the nation’s enemies. It granted the Post Office virtually absolute power to determine whether printed matter obstructed the draft or could “cause or attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, refusal of duty, in the military or naval forces of the United States.”60 The Sedition Act enacted May 16, 1918, extended its reach by criminalizing any criticism of the government, military, or flag in wartime. The acts carried a potential twenty-year prison sentence and $10,000 fine.61

The Post Office interpreted the Espionage Act broadly—and vaguely. The postmaster general could and did exclude periodicals without offering any explanation. The burden of proof lay with the few publishers in a position to challenge a ruling. As Gilbert E. Roe, attorney for the American Union Against Militarism, pointed out, “Any Post Office official may, under this provision, forbid the use of the mails to any matter that he deems non-mailable. Before the question of the mailability of the matter can be determined by the courts the work desired will be done and [the] publisher ruined.”62 The act intentionally bypassed Congress. Legislators launched hearings, and Senator William Borah sought an amendment that would transfer the power to remove periodicals from the postmaster general to the courts, but their efforts were in vain.

Burleson later boasted that thanks to the Espionage Act “hundreds of thousands of tons and millions of pieces of such matter were excluded from the mails and destroyed, during the war.”63 The Call labeled him “His Majesty, Czar Burleson.”64 Oscar Ameringer, who joined the Milwaukee Leader in 1912, in his memoirs blamed Wilson for Postmaster General Burleson’s repression and termed the president the “godfather of Mussolini, Stalin and Hitler.”65 Burleson maintained he enforced the act neutrally:

Nothing will be excluded from the mails because of being politically or personally offensive to the Administration. Nothing will be considered except the welfare of the Nation, and only assaults upon this will bring about action.

But there is a limit, and this limit is reached when a newspaper begins to say that this Government got into the war wrong, that it is there for a wrong purpose, or anything else that impugns the motives of the Government, thereby encouraging insubordination. Newspapers cannot say that this Government is the tool of Wall Street, or of munitions makers, or the tool of anybody.66

Despite his protestations, the postmaster general did use the Espionage Act to censor the radical press. After the war, he wrote a colleague: “No one knows better than you that the timidity of the average congressman is such that we never would have been able to get a law enacted that would in express terms protect the country against the dangers of such publications as ‘The Liberator,’ ‘The Call,’ ‘The Appeal to Reason,’ and those offensive negro papers which constantly appeal to class and race prejudice.”67

On the same day federal agents arrested Goldman and Berkman, Burleson issued a confidential memo to all postmasters to “keep a close watch on unsealed matter” and submit samples to Washington. His memo went beyond the Espionage Act by criminalizing material he believed could embarrass the government in its conduct of the war. The Post Office instructed local postmasters to offer no explanation for rulings. Soon, requests seeking advice on mailing every kind of print matter in practically all languages deluged Washington. Overseeing the massive mail surveillance was the previously nearly invisible Post Office solicitor, Alabaman-born Judge William Lamar. “We have always known that the Post Office delivers our letters, newspapers, packages, etc., and has nothing to do with lawyers, laws, censorships, and other such modern affairs,” wrote Washington correspondent Reuben Fink for the Jewish newspaper the Day. “And, suddenly, as if out of the ground, the word ‘Solicitor’ has appeared in the press.”68 The patrician Lamar maintained a pleasant demeanor as he instituted proceedings to revoke repeat offenders’ second-class privileges and helped federal district attorneys defend highly publicized suits against the act brought by the Call, Milwaukee Leader, and Masses.69

The Masses Challenges the Espionage Act

When the Masses delivered its August issue for mailing on July 3, 1917, Henry J. Glintenkamp’s macabre cover cartoon, Conscription, in which nude corpses slump over a cannon, caught postal inspectors’ attention. Two days later, they informed Eastman the issue was nonmailable. The magazine’s business manager rushed to Washington to confer with Lamar. The solicitor refused to tell him which provisions of the act the magazine violated or what editorial matter violated the act. Masses attorney Roe filed an injunction to stop the postmaster from banning the August issue. The Civil Liberties Bureau called an emergency meeting on July 13. Eastman spoke at its press conference five days later: “The suppression of the Socialist press has actually been more rapid and efficient in this republic than it was in the German Empire after the declaration of war. And as for our celebrated Anglo-Saxon tradition of free speech—it is the memory of a myth. You can’t even collect your thoughts without getting arrested for unlawful assemblage.”70

Only in court did Eastman and his colleagues learn the Post Office claimed the issue violated the Espionage Act provision that forbade obstruction of the draft. Besides Conscription, which the Post Office declared “the worst thing in the magazine,” violations included other antiwar cartoons; two editorials; Josephine Bell’s poem, “A Tribute,” in honor of Goldman and Berkman; and Floyd Dell’s article, “Conscientious Objectors,” which concluded revolution in America no longer was merely a “Utopian fantasy.”71 Roe argued the Espionage Act did not prohibit political criticism or discussion and that the Post Office lacked authority to censor. District Court Judge Learned Hand agreed. He made a novel legal argument that focused on words instead of their effect: he argued that suspect material should be judged solely on what he called an “incitement test”: only if its language directly urged readers to violate the law was it seditious.72 The Post Office then obtained a stay of the injunction and appealed in distant Windsor, Vermont, in a blatant bid to plead its case before one of the nation’s most conservative judges, who promptly reversed Hand’s decision. The court empowered the government to exclude material whose “probable effect” would hamper the war effort, which swelled Post Office powers to those of a mindreader.73 On August 14, the Post Office called the publishers to Washington to show why the Masses’s second-class mail privileges should not be revoked on the grounds that it appeared irregularly due to the missing August issue. The magazine lost.

Henry J. Glintenkamp’s Physically Fit was a response to a government mass order for coffins. The government introduced it as supplementary evidence in the Masses’s 1918 sedition trial. Masses, October 1917.

Fans—including subscribers—had to go to newstands to obtain the Masses’s defiant, nonmailable September issue. “Each month we have something vitally important to say on the war,” the back cover stated. “We are going to fight any attempt to prevent us from saying it.” Charles W. Wood’s essay dripped sarcasm: “I, for one, have renounced the devil and all work. I’ve quit thinking. I ask forgiveness for every thought I ever had and will, hereafter, until further notice, rattle along with the emptiness and ease of a New York Times editoral.”74 Reed called August 1917 the “blackest month for freemen our generation has known.”75 September grew darker when, under the Espionage Act, the Justice Department filed criminal charges that accused Eastman, Dell, Glintenkamp, Reed, Young, business manager Merrill Rogers, and poet Bell of conspiring to obstruct the draft. In a rare interview, Burleson said, “I regard Max Eastman as no better than a traitor, and the stuff he has been printing as rank treason.”76

After the Masses lost its second-class status, four lawyers—Clarence Darrow, Morris Hillquit, Seymour Stedman, and Frank Walsh—visited Burleson to request a clearer and more reasonable policy. He refused, and President Wilson refused to meet them.77 The imperious Burleson also refused a request by Congressman John Moon, chair of the House Committee of Post Office and Post Roads, for names of banned publications, locations of post offices that mailed them, instructions to postmasters, and explanations of why they were banned.78 Newly elected New York socialist congressman London, not surprisingly, got the same brush-off.79 Burleson haughtily informed another senator seeking the same info, “In view of the treasonable utterances of many newspapers and others seeking to embarrass the government in the enforcement of the war measures, it can be readily seen that it would be unwise for the department to enter into a full discussion of all of its plans and conduct to suppress opposition to the enforcement of law.” Anyone who questioned a ruling could seek redress in court.80 When Eastman complained about the ruling to Wilson, the latter took the matter up with Burleson, who refused to characterize it as suppression. Wilson told Eastman, “I can only say that a line must be drawn and that we are trying, it may be clumsily but genuinely, to draw it without fear or favor or prejudice.”81

Espionage Act responsibilities already overwhelmed postal workers when Congress enacted the Trading with the Enemies Act on October 6, 1917. It commanded the Post Office to monitor the contents of all foreign-language periodicals, calculated at 1,293 newspapers and magazines in forty languages with a combined circulation of 8.8 million. Postal workers waded through “tons” of “millions of pieces of mail matter,” most of which officials claimed was “calculated to interfere with the prosecution of the war.”82 Congress authorized $35,000 (increased to $50,000 in 1918) to hire a half-dozen lawyers, five translators, and a small staff. Nationwide, 435 translators volunteered for $1 a year each to read the foreign-language press, mainly at universities and colleges.83 The act allowed the Post Office to issue permits to foreign-language newspapers to publish without submitting translations if they passed a laborious review of multiple issues. Hundreds did, such as the monthly Sioux Iape Oaye of Santee, Nebraska.84 The remainder lacking permits had to submit “a true and complete translation” of every article that discussed the “Government of the United States, or of any nation engaged in the present war, its policies, international relations, the state or conduct of the war, or any matter pertaining thereto,” along with affidavits declaring the translations’ accuracy. Any publication that failed to provide translation was ruled nonmailable, and the act further made it a crime to publish or distribute the offending periodical in any manner.

Berkman and Goldman’s Trial Sets an Oppressive Tone

Berkman and Goldman’s eight-day trial in July 1917 for violating the Espionage Act set the tone for the suppression to come.85 Little Review publisher Margaret Anderson, among the literati who attended, left the “farce” shaking in anger.86 Goldman and Berkman received two-year sentences and $5,000 fines. Goldman wrote that the loss of her magazine hurt more than the prospect of two years in prison. “No offspring of flesh and blood could absorb its mother as this child of mine had drained me,” she reminisced, “and now with one blow its life had been snuffed out!”87 Leonard Abbott of the Free Speech League commented on the sudden reversals of venerable America civil liberties, “Black has become white, and white is now black.”88 Pearson’s editor Allen Ricker professed, “I am now convinced that the radical press of America has been sentenced to death.”89 Goldman’s persecution continued after she left prison. She was among five thousand foreign-born radicals the Department of Justice netted in the Palmer Raids in thirty-three cities in twenty-three states between November 1919 and February 1920, part of the hysterical “Red Scare” that seeped into the 1920s.90 On December 21, 1919, Goldman and Berkowitz were among 249 deported radicals jammed aboard a boat to Russia.91

Mother Earth was just one of some fifteen periodicals the Post Office charged with sedition in summer 1917.92 Social Revolution lost its second-class mail status in July.93 The July ISR was deemed unmailable, and the August issue was released only after editors removed an offending article. Postal authorities then held all issues from September 1917 through February 1918. Federal agents also intercepted bundles of the magazine shipped by express train. Official word in February that he no longer could use the mails or express forced Charles Kerr to cease publication, though his publishing house staggered on.94 Four Lights, the antiwar journal of the radical Woman’s Peace Party of New York, also was quashed, the only women’s periodical suppressed by the government during World War I.95 So were the journals of publisher Tom Watson, the Georgia Populist turned white supremacist whose antipathy toward the draft drove him back toward socialism.96 Some publishers got creative about distributing their nonmailable journals. When American Socialist lost its second-class privilege because it advertised an antiwar pamphlet, editor J. Louis Engdahl inaugurated the Red Express, which he shipped weekly via rail from Chicago. Each party local was to designate a station agent to receive the shipments. The post office, however, revised the law to make it illegal to transport or sell any periodical excluded from the mail. Engdahl eventually was sentenced to twenty years for violating the Espionage Act. By the end of 1917, the Post Office had revoked the second-class mailing privileges of thirty-six periodicals in fifteen states, half of them in foreign languages.97

Mainstream media mustered little opposition to offenses against civil rights. Few journals defended the constitution.98 The New York Times editorialized in support of the radical journals’ suppression.99 In Wisconsin, Appleton and Stevens Point newspapers applauded a ruling against the Milwaukee Leader, while the Green Bay newspaper called for placing all socialists in concentration camps.100 Some citizens did protest the postal censorship, as did an irate Blast subscriber who wrote Burleson after missing two issues. “I think that I am in much better position than yourself to judge what for me would be forbidden literature,” he wrote. “But perhaps since you have set yourself up as my literary censor, you will reimburse me my one dollar.”101

Many more citizens supported the Espionage Act, however, including hundreds who reported suspect disloyal periodicals. The League for National Unity issued a three-page statement that supported the infringement upon the First Amendment on the grounds that Congress “can forbid seditious publications just as it can forbid the transport of nitro-glycerine when public safety requires it.”102 Some officials believed the act did not go far enough. Inspector Maxwell complained that banning an issue of the Call suppressed only 40 percent of its circulation; newsies hawked the remaining 60 percent on New York street corners. “Nothing would impress some of these publications quite so much as to have the worst offenders suppressed with a heavy physical hand,” Maxwell wrote solicitor Lamar, “and I mean by this—one where the blow is not lightened by some legal camouflage.”103 Maxwell wished he could force libraries to destroy “all copies” of books and pamphlets deemed nonmailable.104

Persecution of the Milwaukee Leader’s Victor Berger

Of all persecuted radicals, only Victor Berger faced triple jeopardy as a socialist, publisher, and politician. From the start of the war, the Milwaukee Leader found itself in an impossible position because it could satisfy neither its antiwar socialist readers nor its German-born audience. Berger’s first comment on the war, in 1914, deemed both Russian czarism and German imperialism unacceptable. “Here in America we must make the fight for industrial democracy—for the rule of the people—lest civilization itself may perish,” he wrote.105 A month later Berger lamented socialists’ failure to stop it: “This war is the disgrace of the twentieth century.”106 Circulation dropped when Milwaukee’s German-language press labeled the Leader pro-English. Managing editor Algie Simons resigned soon after Berger hired German-born Ernest Untermann to neutralize Simons’s pro-British bias. The Class Struggle newspaper said of Berger: “A born jingo he has been a German jingo and an American jingo by turns—contriving a synthesis of the two which has become familiar under the name of Hearstianism, an attempt to put American jingoism at the service of German imperialism.”107 When the Leader renounced pacifism in early 1916, some Socialists called for Berger’s recall from the party. “War may be hell, but there are some things in this world worse than ‘hell,’” the Leader editorialized. “Real socialists are willing to fight these things.”108 But the daily remained strongly anti-interventionist until U.S. entry into the war. An April 3, 1917, editorial proposed a wartime program that would nationalize industry, food, and utilities and guarantee an eight-hour day at a just wage and a 100 percent tax on incomes over $10,000. Letters to American Socialist called for shutting down the Leader for its support for the U.S. war effort.

Nonetheless, the Milwaukee Leader became another casualty of the Espionage Act when on September 22 its second-class status was revoked. Only one in six readers outside Milwaukee resubscribed as mail rates doubled. Ameringer and Berger called an October 13 mass meeting, at which more than five thousand people stood up and cheered Berger for fifteen minutes. At the meeting’s end, Ameringer stepped onstage hoisting a washtub, which the crowd filled with more than $4,000. Some donated jewelry. Ameringer recalled, “Democracy had given its mandate. We carried on.” He carried on even though he also faced charges under the Espionage Act, including one count for a satirical poem, “Dumdum Bullets.” The daily dropped from twelve to six pages as advertisers withdrew under pressure. It next lost the right to send or receive any mail. “Even a box of strawberries sent to the editor by parcel post was returned ‘undeliverable under the Espionage Act,’” Berger recalled.109 As the months rolled by, Ameringer invited the Leader’s most prosperous supporters to his office, where he pitched for funds with the plea that unless the daily paid its debts, “the last hope of America’s free press was lost forever.”110 Eventually, even its staunchest supporters dodged Ameringer.

The Leader became one of a handful of publications to challenge the postal censorship in court. When a postal hearing upheld its revocation, its publishers sought a writ of mandamus compelling Burleson to restore the newspaper’s second-class rates. The Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia rejected the plea. Judge Charles H. Robb declared that no one could read the Leader’s editorials “without becoming convinced that they were printed in a spirit of disloyalty to our government and in a spirit of sympathy for the Central Powers.”111 Berger appealed to the Supreme Court.

Berger’s woes worsened in February 1918, when the government indicted him and four other party leaders with conspiracy to hinder the war effort. Milwaukeeans nonetheless elected him to Congress. The quintet’s dramatic four-week trial in Chicago the following winter ended with their January 8, 1919, conviction of violating the Espionage Act. They were each sentenced to twenty years in prison. Supporters quickly raised bail to keep them free pending appeal. Under his bail terms, Berger could neither write for nor participate in editorial decisions at the Leader. His humiliation heightened when Congress refused to seat him. On November 10, 1919, the House voted to formally exclude him from office for disloyalty by 311 votes to 1. Mainstream media applauded the vote. Milwaukee Socialists responded by nominating him for the hastily called special election for the empty seat. He won by 24,350 to 19,566, 40 percent more votes than in 1918’s three-way race, but Congress again refused to seat him.112

Nationwide Raids on the IWW and Its Newspapers

On September 5, 1917, the Justice Department raided IWW offices in Chicago, Fresno, Seattle, Spokane, and other cities. They seized everything, in what IW called U.S. governmental “terrorism.”113 Before the nation entered the war, federal officials had barred some of the prolific organization’s dozen publications under the Comstock law’s incitement provision. The Post Office had declared the IWW’s Italian- and Hungarian-language newspapers unmailable in August 1917, and from September 1917 on, Cultura Obrera, New York dockworkers’ Spanish organ, routinely was banned, even though officials acknowledged they found no specific violations. “Though not violating the law openly every one of these lines contain that subtle poison which is the last hope of the Kaiser,” the inspector wrote.114 IW believed itself immune from the Espionage Act, as it professed the IWW an industrial rather than political organization.115 The IWW had taken no antiwar actions but refused to sanction Wilson’s crusade. The closest Solidarity editor Ralph Chaplin came to direct action against the war was his instruction to readers to claim draft exemptions with the explanation, “I.W.W., opposed to war.”116 Although the organization took no formal position on conscription, a poem in IW captured the Wobblies’ pacifist insouciance:

I love my flag, I do, I do,

Which floats upon the breeze,

And neck, and nose, and knees.

One little shell might spoil them all

Or give them such a twist,

They would be of no use to me;

I guess I won’t enlist.117

Solidarity editor Chaplin naïvely believed IWW records would clear the organization. “We have nothing to hide,” he assured readers, even though, as historian Melvyn Dubofsky observes, “for thirteen years the Wobblies had been publishing and distributing radical, sometimes revolutionary, literature … anti-war and anti-government tirades filled the organization’s newspapers, pamphlets, and correspondence.”118 The IWW’s pugnacious journals sealed its fate. Denied its second-class mailing status, Solidarity published its last issue October 30, 1917. A Defense News Bulletin replaced it in November and continued until July 1918. IW somehow stumbled on until May 25, 1918, with Kate MacDonald filling in as editor for her imprisoned husband until her own arrest December 20. J. A. MacDonald and Chaplin were among dozens of IWW leaders indicted on charges of conspiracy to obstruct the war.

Journalism remained the IWW’s lifeline. IW printed names of imprisoned Wobblies and lists of indicted men who, according to IWW lawyers, should surrender.119 The rakish rebels retained their Pollyannaish optimism, with such headlines as “Trial to Advertise IWW World Over.”120 The prosecution relied heavily on numerous quotations opposing the American military and espousing direct action from Solidarity and the IW, however, during the Chicago trial of 166 Wobblies, which began April 1, 1918.121 A Trial Bulletin that kept the faithful apprised of courtroom proceedings blamed the government for taking the IWW’s revolutionary rhetoric out of context. “Many and ludicrous are the errors the union-crushing pettifoggers of the prosecution have made in attempting to display their familiarity with the vernacular of the working class,” one account observed.122 The Post Office ruled this mild Trial Bulletin number unmailable after granting search warrants to open subscribers’ mail. Of the 101 members convicted in Chicago, 13 were editors of IWW journals.123 Inside the Chicago jail, some Wobbly inmates kept busy by starting a newspaper, the Can-Opener.124

Misuse of the Espionage Act against the Black Press

Federal monitoring of six black journals during World War I is more evidence the goverment used the Espionage Act to stymie discussion of social issues. These included the Challenge, Crisis, Crusader, Messenger, New York Age, and Negro World.125 Letters had poured in from citizens objecting to contents of the NAACP’s Crisis as well as from local postmasters who refused to deliver it. For example, a Texas lawyer complained the magazine was “filled with poison” and ordered a black barber to stop distributing it; an Idaho woman reported she found “treason in every line.”126 Arkansas’s governor demanded in 1919 that Burleson keep the Crisis out of his state.127 Offending articles in the January 1918 Crisis ruled unmailable under the Espionage Act included an editorial claiming Negroes were valued as soldiers but considered “worse than worthless” when they tried to exercise their civil rights.128 The Post Office deemed the April 1918 issue unmailable due to an Alice Dunbar-Nelson skit depicting African American siblings debating the war when their brother is drafted. It ruled “Mine Eyes Have Seen” seditious even though the draftee ends up eager to enlist. In July 1918, the beleaguered Crisis urged African Americans to support and join the war effort.129

In contrast to W. E. B. Du Bois, Messenger editor A. Philip Randolph continued to oppose World War I. The magazine was an adamant defender of free speech. When suffragists, led by Alice Paul’s National Woman’s Party, were jailed for picketing the White House, the Messenger praised their civil disobedience—a strategy that became the linchpin of Martin Luther King’s civil rights campaign some forty years later. Randolph observed of the arrests: “This of itself is of tremendous value, because it starts discussion; the fires through which the fundamental weapons of liberty—free speech, free press and free assemblage—have been formed.”130

Randolph also protested postal censorship. “We admit that a line must be drawn somewhere,” he wrote. “We believe that the line must be drawn too, more scrupulously against government suppression than against unbridled free speech.”131 The Messenger became the only black periodical to lose its second-class mail privileges in World War I. The Post Office held up the July 1919 issue because it contained the taboo IWW preamble advocating direct action and an article, “Why the Negroes Should Join the I.W.W.”132 Racist assumptions riddled inspector Robert Bowen’s analysis of the Messenger: “It impresses me as an exceedingly mischievous publication,” he told Lamar, “not to be sneezed at because it is merely a negro publication or because some of its arguments are as immature as practically every one of them is dangerous.” He worried, “This is the first time I have seen a negro publication come out openly as advocating or demanding social equality.”133

Bowen’s blue pencil marks reveal governmental indifference to issues that compelled African American dissent. An August 1919 article, “How to Stop Lynching,” bothered Bowen because of its “frank advocacy of a resort to armed violence and organized force.” The postal authorities’ answer to terrorism against black citizens was to silence discussion about lynching. The newspaper refused to be cowed, and in its next issue it printed a cartoon depicting a rifle-bearing “New Crowd Negro” mowing down members of a white mob. “Since the Government won’t stop mob violence I’ll take a hand,” he says.134

Offending articles in other black periodicals were harbingers of the amorphous civil rights movement that fomented through a second world war before gelling in the 1950s, just in time to benefit from the new mass medium of television. The Guardian became suspect because of publisher William Monroe Trotter’s aggressive civil rights campaigns.135 Negro World alarmed officials with its militant rhetoric that encouraged returning black veterans to fight for racial justice. Historian Robert Hill cites Negro World headlines, such as “Revolt Threat Is Voiced by Negroes: Bishop Hurst Declares 400,000 Colored Men Who Fought for U.S. Are Ready to ‘Free’ Race,” among reasons federal officials designated it the most radical Negro publication at the end of the war.136 Bowen warned of dangerous influences at work “to arouse in the negro a well-defined class-consciousness, sympathetic only with the most malign radical movements.”137

Subjectivity: The Case of Two Radical Arizona Newspapers

The experience of two Arizona labor newspapers demonstrates how subjective was interpretation of the espionage and sedition acts. Arizona Labor Journal was the organ of the Arizona State Federation of Labor, whose president served as editor. In February 1918, as a “public service,” the state chapter of the American Mining Congress of mine owners sent postal solicitor Lamar several issues of the Journal and the Phoenix-based labor paper, Dunbar’s Weekly. Chapter headquarters were in Bisbee, site of the infamous 1917 deportation of striking miners. Owners remained locked in bitter battle with miners across the state. Congress state secretary Joseph Curry warned Lamar: “The two publications are insidiously doing their utmost in aid of plans which are developing for another year of misunderstanding and industrial strife and disturbance in the State.”138 Lamar ruled that the March 29, 1918, issue violated the Espionage Act. Inspectors underlined three articles: “Mooney Must Be Freed,” “Conscription of Wealth,” and “Billy Waldrop Victim Vigilantes,” which recounted the kidnapping, tarring, and feathering of the Jerome miners’ union leader.139 The newspaper also was running its eleventh installment of a sympathetic New York Evening Post series, “On the Trail of the I.W.W.”140 The Post article was reprinted in Spanish on page three, which served as “El Jornal de Trabajo de Arizona,” the Spanish section of the newspaper edited by Canuto A. Vargas. Curry, of course, was no disinterested observer, and the Post Office served the owners’ interests by silencing the miners’ organ. Curry claimed, “Outside influences have caused all the complaint.” He even charged the radicals committed the tar-and-feathering “for the convenience of the Journal.” “Good Americanism,” Curry argued, demanded the Post Office suppress the Journal and Dunbar’s for the war’s duration.141

Inspectors interpreted articles literally, such as a February 22, 1918, editorial opposing conscription of labor. “It is not necessary—it is not safe; and, if the masters of industry were as wise as they pretend, they would drop the subject—it is a loaded stick of dynamite. The harder you press it, the harder it kicks back.” An analysis of Dunbar’s likewise construed the most negative meaning from a March 30, 1918, passage that read: “The battlefield of Europe today is covered with hundreds of thousands of dead men; men who sacrificed to prolong and promote such inhumanity to man. Millions of gallant lives have been sacrificed the past three years to satisfy that damnable lust for power and greed.” The inspector reported, “This is an underhanded way of saying that the European war is a captilistic [sic] war and it is also a call to the readers under the guise of prophecy to resort to violence in overthrowing the present system of government.”142 In New York, postal inspector Louis How’s 1918 campaign to ban the bimonthly Intercollegiate Socialist is another illustration of how the Post Office could silence discussion of important public issues. Lamar declined How’s recommendation the April-May issue be held because of an article on “the negro situation” by Debs—“whose name alone is enough to make us suspicious.” The Post Office, however, held up the October–November issue (among others) because it contained an article criticizing British colonialism in India.143

More Radical Journals Suppressed

Sometimes just the threat of prosecution was enough to kill radical journals. Inspectors marked several items suspect in the August 1917 Seven Arts: Reed’s “This Unpopular War,” Randolph Bourne’s “The Collapse of American Strategy,” and a poem and editorial that lamented the war.144 “‘Enemies Within,’ shrieked the old New York Tribune and spat snake’s venom at Bourne and the rest of us,” recalled editor James Oppenheim.145 Bourne’s series of essays opposing the war have endured as masterpieces. Frightened by the Espionage Act, the Seven Arts’s wealthy backer withdrew her funding. It shut down in October, before merging into the Dial. The censorship even affected art journals such as Camera Work, which ceased publication in 1917.

The post office’s long campaign against the Appeal to Reason ground on during the war. In 1915, as editor of the Appeal to Reason, Allan Benson, a former Detroit Times editor, campaigned for peace in his column, “A Way to Prevent War.”146 When he left in 1916 to run as the Socialist presidential candidate, his successor, Louis Kopelin, formerly of the Call, continued to oppose U.S. entrance into the war but limited commentary.147 The Appeal never advised readers not to register with the Selective Service, although it suggested they register as conscientious objectors.148 Once the United States entered the fray, it limited criticism to demand only that the war end with neither side annexing nations.149 As it had in previous battles, the weekly conflated achieving world peace with boosting circulation.150 The post office refused to mail the June 30, 1917, issue, even though its frontpage editorial, which called upon Wilson to specify his postwar plans for Germany, also lauded American press freedom that protected such comments.151 New owner Emanuel Julius lacked Julius Wayland’s stomach for fighting the government. By the end of the year, the feisty weekly was supplanted by the New Appeal, which pledged to support the war as part of the social revolution.152

In 1918, the postal inspectors’ green pencils declared nonmailable the venerable Weekly People, the vitriolic Socialist Labor Party paper the late Daniel De Leon had edited for more than a decade.153 By that fall, the government had interfered with some seventy-five papers, forty-five of them socialist.154 Individuals also were targeted. Hillquit stated that by spring 1918, the law resulted in about one thousand indictments and more than two hundred convictions.155 They included Debs, sentenced to ten years in prison for urging draft resistance in a Canton, Ohio, speech. He received 913,664 write-in votes (3.4 percent of the total) for president in the 1920 election without leaving his Atlanta federal prison cell.156

“No person suspected of radical or pacifist opinions was safe,” stated Hillquit, who defended many journalists and others charged under the act, including journalists at the Masses, Milwaukee Leader, Pearson’s, Forverts, and American Socialist, as well the newspaper he helped found, the Call. When the daily lost its second-class privileges because of an October 3, 1918, article headlined “Bankers Hope to Sue Soldiers Back from War to Cut Wages,” Hillquit sought a writ of mandamus from the Supreme Court. The justices rejected it. Then, when the Post Office continued its ban even after the war ended, he filed a half-million-dollar suit against Postmaster General Albert Sidney Burleson. Call journalists soldiered on despite the blow to circulation and finances. So did Hillquit, arguing inside various courtrooms that the socialist press was truly American and that socialists believed patriotism included the freedoms of press and speech and the right to criticize government. He recalled, “The spirit of heresy hunting and witch burning had come back to America in the year of our Lord 1918.”157

A sliver of light pierced this gloom when a single juror’s refusal to convict the Masses journalists at their April 1918 trial forced a mistrial, and a second conspiracy trial that autumn won acquittals for the codefendants, including Reed, who trekked back for the event from covering the Russian Revolution.158 Most defendants tried under the Espionage Act, however, were less fortunate. Among the Masses trial observers sat Kate Richards O’Hare, awaiting an appeal of her own conviction under the Sedition Act for describing American women as brood animals for the military. Her case jeopardized more than free speech. As Kathleen Kennedy observed, “At stake in O’Hare’s case was how women’s violation of patriotic motherhood endangered the state’s production of loyal citizens in general and soldiers in particular.”159 The only mother imprisoned under the act entered the Missouri State Penitentiary at age forty-three on April 15, 1919, to begin her five-year sentence.160

Conclusion

The Masses won the battle but lost the war. It was gone by the time of its editors’ acquittal. So were almost all of the periodicals described here, some forever.161 After the war, the Supreme Court upheld the Espionage Act in several landmark cases.162 The years surrounding World War I remain the most oppressive in twentieth-century American history.

The radical periodicals’ demise marked the end of a vibrant, eclectic radical print culture unmatched in the United States until the heretical underground press surfaced in the 1960s.163 “The real tragedy,” according to historians H. C. Peterson and Gilbert C. Fite, “was the suppression of debate and inquiry so important to the democratic process.”164