Chapter 6. Text Properties

Sure, a lot of web design involves picking the right colors and getting the coolest look for your pages, but when it comes right down to it, you probably spend more of your time worrying about where text will go and how it will look. Such concerns gave rise to HTML tags such as <FONT> and <CENTER> in the web’s early days, which allowed you some measure of control over the appearance and placement of text.

Because text is so important, there are many CSS properties that affect it in one way or another. What is the difference between text and fonts? At the simplest level, text is the content, and fonts are used to display that content. Using text properties, you can affect the position of text in relation to the rest of the line, superscript it, underline it, and change the capitalization. You can even simulate, to a limited degree, the use of a typewriter’s Tab key.

Indentation and Inline Alignment

Let’s start with a discussion of how you can affect the inline positioning of text within a line. Think of these basic actions as the same types of steps you might take to create a newsletter or write a report.

First, however, let’s take a moment to talk about the terms inline and block as they’ll be used in this chapter. In fact, let’s take them in reverse. If your primary language is Western-derived, then you’re used to a block direction of top to bottom, and an inline direction of left to right. Let’s examine those terms more closely.

The block direction is the direction in which block elements are placed by default in the current writing mode. In English, for example, the block direction is top to bottom, or vertical, as one paragraph (or other text element) is placed beneath the one before.

The inline direction is the direction in which inline elements are written within a block. To again take English as an example, the inline direction is left to right, or horizontal. In languages like Arabic and Hebrew, the inline direction is right to left instead.

Let’s reconsider English for a moment. A plain page of English text, displayed on a screen, has a vertical block direction and a horizontal inline direction. But if the page is rotated 90 degrees anticlockwise using CSS Transforms, then suddenly the block direction is horizontal and the inline direction is vertical. (And bottom to top, at that.)

This approach to content and layout is relatively new as of 2017, and a conversion from the old layout language, which was highly dependent on concepts of “horizontal” and “vertical,” is still underway. While the rest of the chapter will try to use the terms “block direction” and “inline direction,” please forgive any lapses into “vertical” and “horizontal.”

Indenting Text

Most books we read in Western languages format paragraphs of text with the first line indented, and no blank line between paragraphs. Some sites used to create the illusion of indented text by placing a small transparent image before the first letter in a paragraph, which shoved the text over. Thanks to CSS, there’s a much better way to indent text: text-indent.

Using text-indent, the first line of any element can be indented by a given length, even if that length is negative. A common use for this property is to indent the first line of a paragraph:

p{text-indent:3em;}

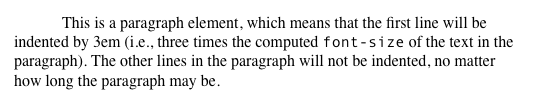

This rule will cause the first line of any paragraph to be indented three ems, as shown in Figure 6-1.

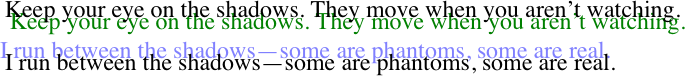

Figure 6-1. Text indenting

In general, you can apply text-indent to any element that generates a block box, and the indentation will occur along the inline direction. You can’t apply it to inline elements or on replaced elements such as images. However, if you have an image within the first line of a block-level element, it will be shifted over with the rest of the text in the line.

Note

If you want to “indent” the first line of an inline element, you can create the effect with left padding or margin.

You can also set negative values for text-indent, a technique that leads to a number of interesting effects. The most common use is a hanging indent, where the first line hangs out to one side of the rest of the element:

p{text-indent:−4em;}

Be careful when setting a negative value for text-indent; the first few words may be chopped off by the edge of the browser window if you aren’t careful. To avoid display problems, I recommend you use a margin or some padding to accommodate the negative indentation:

p{text-indent:−4em;padding-left:4em;}

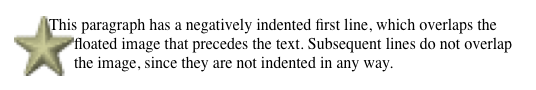

Negative indents can, however, be used to your advantage. Consider the following example, demonstrated in Figure 6-2, which adds a floated image to the mix:

p.hang{text-indent:−25px;}

<imgsrc="star.gif"style="width: 60px; height: 60px;float: left;"alt="An image of a five-pointed star."/><pclass="hang">This paragraph has a negatively indented first line, which overlaps the floated image that precedes the text. Subsequent lines do not overlap the image, since they are not indented in any way.</p>

Figure 6-2. A floated image and negative text indenting

A variety of interesting designs can be achieved using this simple technique.

Note

This specific effect, of trying to make text wrap along the edge of a floated image, is more robustly managed with CSS Float Shapes. See Chapter 10 for details.

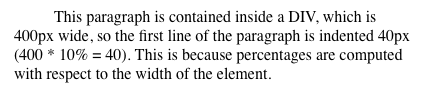

Any unit of length, including percentage values, may be used with text-indent. In the following case, the percentage refers to the width of the parent element of the element being indented. In other words, if you set the indent value to 10%, the first line of an affected element will be indented by 10 percent of its parent element’s width, as shown in Figure 6-3:

div{width:400px;}p{text-indent:10%;}

<div><p>This paragraph is contained inside a DIV, which is 400px wide, so the first line of the paragraph is indented 40px (400 * 10% = 40). This is because percentages are computed with respect to the width of the element.</p></div>

Figure 6-3. Text indenting with percentages

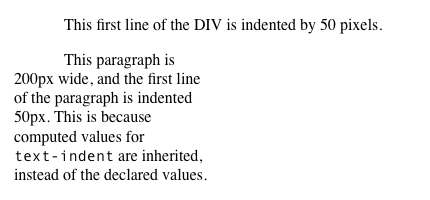

Note that this indentation only applies to the first line of an element, even if you insert line breaks. The interesting part about text-indent is that because it’s inherited, it can have unexpected effects. For example, consider the following markup, which is illustrated in Figure 6-4:

div#outer{width:500px;}div#inner{text-indent:10%;}p{width:200px;}

<divid="outer"><divid="inner">This first line of the DIV is indented by 50 pixels.<p>This paragraph is 200px wide, and the first line of the paragraph is indented 50px. This is because computed values for 'text-indent' are inherited, instead of the declared values.</p></div></div>

Figure 6-4. Inherited text indenting

Text Alignment

Even more basic than text-indent is the property text-align, which affects how the lines of text in an element are aligned with respect to one another.

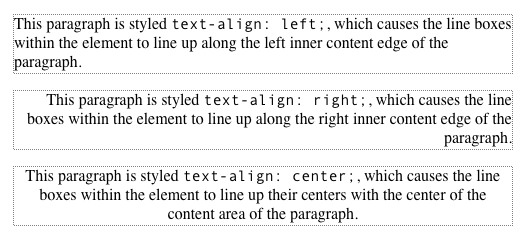

The quickest way to understand how these values work is to examine Figure 6-5, which sticks with three most widely supported values for the moment.

Figure 6-5. Selected behaviors of the text-align property

The values left, right, and center cause the text within elements to be aligned exactly as described. Because text-align applies only to block-level elements, such as paragraphs, there’s no way to center an anchor within its line without aligning the rest of the line (nor would you want to, since that would likely cause text overlap).

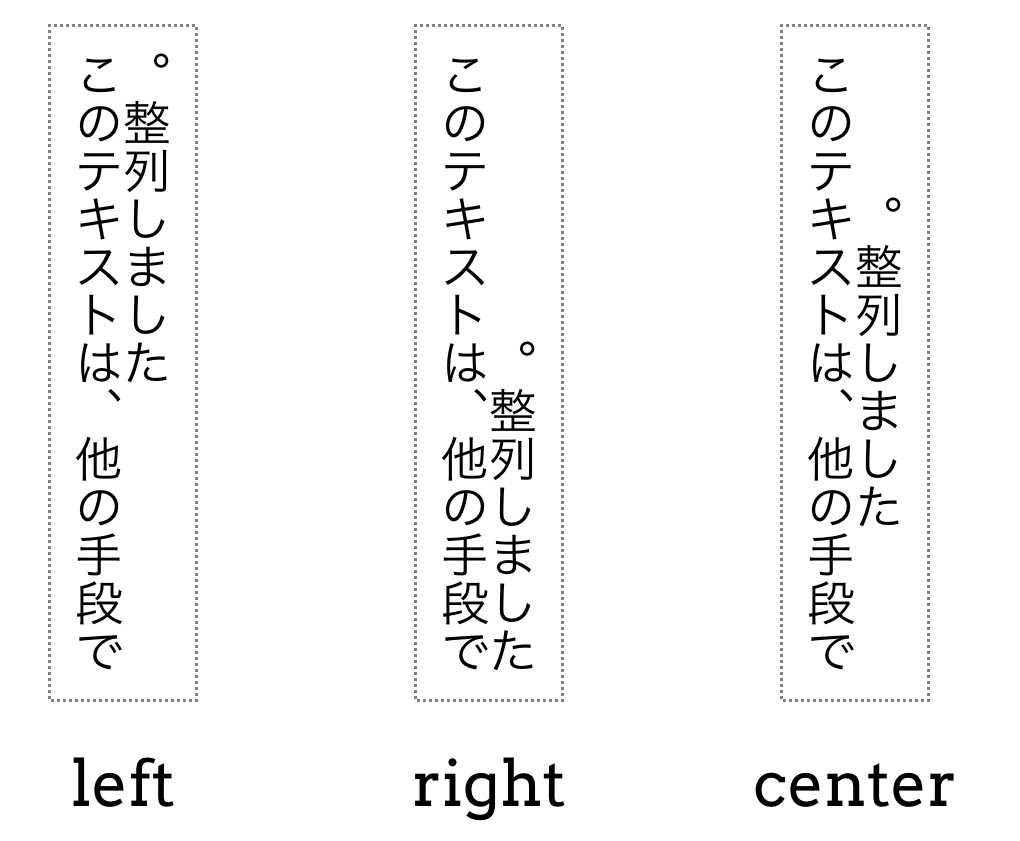

Historically, which is to say under CSS 2.1 rules, the default value of text-align is left in left-to-right languages, and right in right-to-left languages. (CSS 2.1 had no notion of vertical writing modes.) In CSS3, left and right are mapped to the start or end edge, respectively, of a vertical language. This is illustrated in Figure 6-6.

Figure 6-6. Left, right, and center in vertical writing modes

As you no doubt expect, center causes each line of text to be centered within the element. Although you may be tempted to believe that text-align: center is the same as the <CENTER> element, it’s actually quite different. <CENTER> affected not only text, but also centered whole elements, such as tables. text-align does not control the alignment of elements, only their inline content. Figures 6-5 and 6-6 illustrate this clearly in various writing directions.

Start and end alignment

CSS3 (which is to say, the CSS Text Module Level 3 specification) added a number of new values to text-align, and even changed the default property value as compared to CSS 2.1.

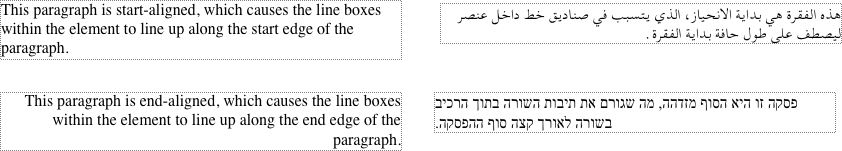

The new default value of start means that the text is aligned to the start edge of its line box. In left-to-right languages like English, that’s the left edge; in right-to-left languages such as Arabic, it’s the right edge. In vertical languages, for that matter, it will be the top or bottom, depending on the writing direction. The upshot is that the default value is much more aware of the document’s language direction while leaving the default behavior the same in the vast majority of existing cases.

In a like manner, end aligns text with the end edge of each line box—the right edge in LTR languages, the left edge in RTL languages, and so forth. The effects of these values are shown in Figure 6-7.

Figure 6-7. Start and end alignment

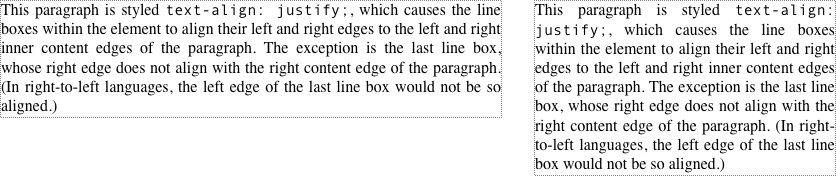

Justified text

An often-overlooked alignment value is justify, which raises some issues of its own. In justified text, both ends of a line of text are placed at the inner edges of the parent element, as Figure 6-8 shows. Then, the spacing between words and letters is adjusted so that each line is precisely the same length. Justified text is common in the print world (for example, in this book), but under CSS, a few extra considerations come into play.

Figure 6-8. Justified text

The user agent—and not CSS, at least as of late 2017—determines how justified text should be stretched to fill the space between the left and right edges of the parent. Some browsers, for example, might add extra space only between words, while others might distribute the extra space between letters (although the CSS specification states that “user agents may not further increase or decrease the inter-character space” if the property letter-spacing has been assigned a length value). Other user agents may reduce space on some lines, thus mashing the text together a bit more than usual. All of these possibilities will affect the appearance of an element, and may even change its height, depending on how many lines of text result from the user agent’s justification choices.

Parent matching

There’s one more value to be covered, which is match-parent. This isn’t supported by browsers, but its intent is mostly covered by inherit anyway. The idea is, if you declare text-align: match-parent, the alignment of the element will match the alignment of its parent.

So far, that sounds exactly like inherit, but there’s a difference: if the parent’s alignment value is start or end, the result of match-parent is to assign a computed value of left or right to the element. That wouldn’t happen with inherit, which would apply start or end to the element with no changes.

Aligning the Last Line

There may be times when you want to align the text in the very last line of an element differently than you did the rest of the content. For example, you might left-align the last line of an otherwise fully justified block of text, or choose to swap from left to center alignment. For those situations, there is text-align-last.

As with text-align, the quickest way to understand how these values work is to examine Figure 6-9.

Figure 6-9. Differently aligned last lines

As the figure shows, the last lines of the elements are aligned independently of the rest of the elements, according to the elements’ text-align-last values.

A close study of Figure 6-9 will reveal that there’s more at play than just the last lines of block-level elements. In fact, text-align-last applies to any line of text that immediately precedes a forced line break, whether or not said line break is triggered by the end of an element. Thus, a line break occasioned by a <br> tag will make the line of text immediately before that break use the value of text-align-last. So too will it affect the last line of text in a block-level element, since a line break is generated by the element’s closure.

There’s an interesting wrinkle in text-align-last: if the first line of text in an element is also the last line of text in the element, then the value of text-align-last takes precedence over the value of text-align. Thus, the following styles will result in a centered paragraph, not a start-aligned paragraph:

p{text-align:start;text-align-last:center;}

<p>A paragraph.</p>

Inline Alignment

Now that we’ve covered alignment along the inline direction, let’s move on to the vertical alignment of inline elements along the block direction—things like superscripting and “vertical alignment,” as it’s called. (Vertical with respect to the line of text, if the text is laid out horizontally.) Since the construction of lines is a very complex topic that merits its own small book, I’ll just stick to a quick overview here.

The Height of Lines

The distance between lines can be affected by changing the “height” of a line. note that “height” here is with respect to the line of text itself, assuming that the longer axis of a line is “width” even if it’s written vertically. The property names we cover from here will reveal a strong bias toward Western languages and their writing directions; this is an artifact of the early days of CSS, when Western languages were the only ones that could be easily represented.

The line-height property refers to the distance between the baselines of lines of text rather than the size of the font, and it determines the amount by which the height of each element’s box is increased or decreased. In the most basic cases, specifying line-height is a way to increase (or decrease) the vertical space between lines of text, but this is a misleadingly simple way of looking at how line-height works. line-height controls the leading, which is the extra space between lines of text above and beyond the font’s size. In other words, the difference between the value of line-height and the size of the font is the leading.

When applied to a block-level element, line-height defines the minimum distance between text baselines within that element. Note that it defines a minimum, not an absolute value, and baselines of text can wind up being pushed further apart than the value of line-height. line-height does not affect layout for replaced elements, but it still applies to them.

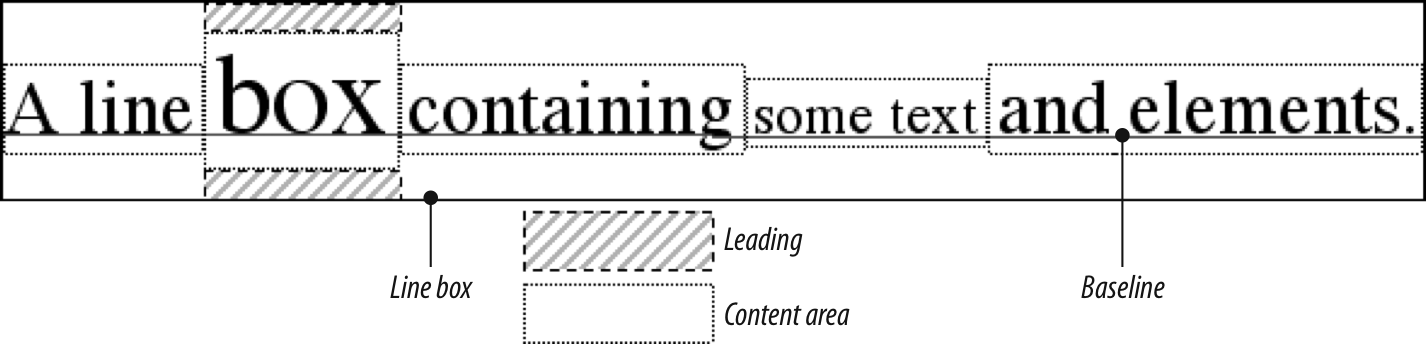

Constructing a line

Every element in a line of text generates a content area, which is determined by the size of the font. This content area in turn generates an inline box that is, in the absence of any other factors, exactly equal to the content area. The leading generated by line-height is one of the factors that increases or decreases the height of each inline box.

To determine the leading for a given element, subtract the computed value of font-size from the computed value of line-height. That value is the total amount of leading. And remember, it can be a negative number. The leading is then divided in half, and each half-leading is applied to the top and bottom of the content area. The result is the inline box for that element.

As an example, let’s say the font-size (and therefore the content area) is 14 pixels tall, and the line-height is computed to 18 pixels. The difference (4 pixels) is divided in half, and each half is applied to the top and bottom of the content area. This creates an inline box that is 18 pixels tall, with 2 extra pixels above and below the content area. This sounds like a roundabout way to describe how line-height works, but there are excellent reasons for the description.

Once all of the inline boxes have been generated for a given line of content, they are then considered in the construction of the line box. A line box is exactly as tall as needed to enclose the top of the tallest inline box and the bottom of the lowest inline box. Figure 6-10 shows a diagram of this process.

Figure 6-10. Line box diagram

Assigning values to line-height

Let’s now consider the possible values of line-height. If you use the default value of normal, the user agent must calculate the space between lines. Values can vary by user agent, but they’re generally around 1.2 times the size of the font, which makes line boxes taller than the value of font-size for a given element.

Many values are simple length measures (e.g., 18px or 2em), but raw <number> values are preferable in many situations. Be aware that even if you use a valid length measurement, such as 4cm, the browser (or the operating system) may be using an incorrect metric for real-world measurements, so the line height may not show up as exactly four centimeters on your monitor.

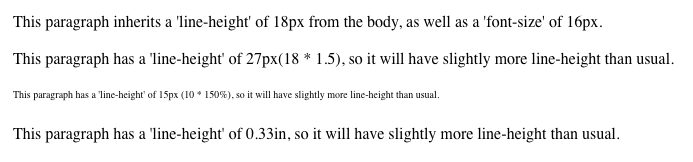

em, ex, and percentage values are calculated with respect to the font-size of the element. The results of the following CSS and HTML are shown in Figure 6-11:

body{line-height:18px;font-size:16px;}p.cl1{line-height:1.5em;}p.cl2{font-size:10px;line-height:150%;}p.cl3{line-height:0.33in;}

<p>This paragraph inherits a 'line-height' of 14px from the body, as well as a 'font-size' of 13px.</p><pclass="cl1">This paragraph has a 'line-height' of 27px(18 * 1.5), so it will have slightly more line-height than usual.</p><pclass="cl2">This paragraph has a 'line-height' of 15px (10 * 150%), so it will have slightly more line-height than usual.</p><pclass="cl3">This paragraph has a 'line-height' of 0.33in, so it will have slightly more line-height than usual.</p>

Figure 6-11. Simple calculations with the line-height property

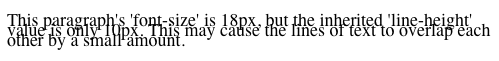

Line-height and inheritance

When the line-height is inherited by one block-level element from another, things get a bit trickier. line-height values inherit from the parent element as computed from the parent, not the child. The results of the following markup are shown in Figure 6-12. It probably wasn’t what the author had in mind:

body{font-size:10px;}div{line-height:1em;}/* computes to '10px' */p{font-size:18px;}

<div><p>This paragraph's 'font-size' is 18px, but the inherited 'line-height' value is only 10px. This may cause the lines of text to overlap each other by a small amount.</p></div>

Figure 6-12. Small line-height, large font-size, slight problem

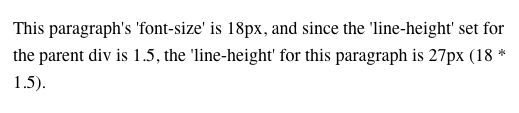

Why are the lines so close together? Because the computed line-height value of 10px was inherited by the paragraph from its parent div. One solution to the small line-height problem depicted in Figure 6-12 is to set an explicit line-height for every element, but that’s not very practical. A better alternative is to specify a number, which actually sets a scaling factor:

body{font-size:10px;}div{line-height:1;}p{font-size:18px;}

When you specify a number, you cause the scaling factor to be an inherited value instead of a computed value. The number will be applied to the element and all of its child elements so that each element has a line-height calculated with respect to its own font-size (see Figure 6-13):

div{line-height:1.5;}p{font-size:18px;}

<div><p>This paragraph's 'font-size' is 18px, and since the 'line-height' set for the parent div is 1.5, the 'line-height' for this paragraph is 27px (18 * 1.5).</p></div>

Figure 6-13. Using line-height factors to overcome inheritance problems

Though it seems like line-height distributes extra space both above and below each line of text, it actually adds (or subtracts) a certain amount from the top and bottom of an inline element’s content area to create an inline box. Assume that the default font-size of a paragraph is 12pt and consider the following:

p{line-height:16pt;}

Since the “inherent” line height of 12-point text is 12 points, the preceding rule will place an extra 4 points of space around each line of text in the paragraph. This extra amount is divided in two, with half going above each line and the other half below. You now have 16 points between the baselines, which is an indirect result of how the extra space is apportioned.

If you specify the value inherit, then the element will use the computed value for its parent element. This isn’t really any different than allowing the value to inherit naturally, except in terms of specificity and cascade resolution.

Now that you have a basic grasp of how lines are constructed, let’s talk about “vertically” aligning elements relative to the line box—that is, displacing them along the block direction.

Vertically Aligning Text

If you’ve ever used the elements sup and sub (the superscript and subscript elements), or used an image with markup such as <img src="foo.gif" align="middle">, then you’ve done some rudimentary vertical alignment. In CSS, the vertical-align property applies only to inline elements and replaced elements such as images and form inputs. vertical-align is not an inherited property.

Note

Because of the property name vertical-align, this section will use the terms “vertical” and “horizontal” to refer to the block and inline directions of the text.

vertical-align accepts any one of eight keywords, a percentage value, or a length value. The keywords are a mix of the familiar and unfamiliar: baseline (the default value), sub, super, bottom, text-bottom, middle, top, and text-top. We’ll examine how each keyword works in relation to inline elements.

Warning

Remember: vertical-align does not affect the alignment of content within a block-level element. You can, however, use it to affect the vertical alignment of elements within table cells.

Baseline alignment

vertical-align: baseline forces the baseline of an element to align with the baseline of its parent. Browsers, for the most part, do this anyway, since you’d probably expect the bottoms of all text elements in a line to be aligned.

If a vertically aligned element doesn’t have a baseline—that is, if it’s an image, a form input, or another replaced element—then the bottom of the element is aligned with the baseline of its parent, as Figure 6-14 shows:

img{vertical-align:baseline;}

<p>The image found in this paragraph<imgsrc="dot.gif"alt="A dot"/>has its bottom edge aligned with the baseline of the text in the paragraph.</p>

Figure 6-14. Baseline alignment of an image

This alignment rule is important because it causes some web browsers to always put a replaced element’s bottom edge on the baseline, even if there is no other text in the line. For example, let’s say you have an image in a table cell all by itself. The image may actually be on a baseline, but in some browsers, the space below the baseline causes a gap to appear beneath the image. Other browsers will “shrink-wrap” the image with the table cell, and no gap will appear. The gap behavior is correct, despite its lack of appeal to most authors.

Note

See the aged and yet still relevant article “Images, Tables, and Mysterious Gaps” for a more detailed explanation of gap behavior and ways to work around it.

Superscripting and subscripting

The declaration vertical-align: sub causes an element to be subscripted, meaning that its baseline (or bottom, if it’s a replaced element) is lowered with respect to its parent’s baseline. The specification doesn’t define the distance the element is lowered, so it may vary depending on the user agent.

super is the opposite of sub; it raises the element’s baseline (or bottom of a replaced element) with respect to the parent’s baseline. Again, the distance the text is raised depends on the user agent.

Note that the values sub and super do not change the element’s font size, so subscripted or superscripted text will not become smaller (or larger). Instead, any text in the sub- or superscripted element should be, by default, the same size as text in the parent element, as illustrated by Figure 6-15:

span.raise{vertical-align:super;}span.lower{vertical-align:sub;}

<p>This paragraph contains<spanclass="raise">superscripted</span>and<spanclass="lower">subscripted</span>text.</P>

Figure 6-15. Superscript and subscript alignment

Note

If you wish to make super- or subscripted text smaller than the text of its parent element, you can do so using the property font-size.

Bottom feeding

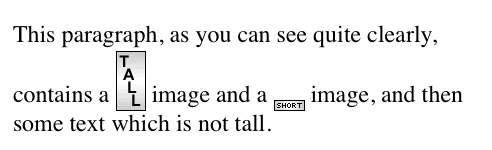

vertical-align: bottom aligns the bottom of the element’s inline box with the bottom of the line box. For example, the following markup results in Figure 6-16:

.feeder{vertical-align:bottom;}

<p>This paragraph, as you can see quite clearly, contains a<imgsrc="tall.gif"alt="tall"class="feeder"/>image and a<imgsrc="short.gif"alt="short"class="feeder"/>image, and then some text that is not tall.</p>

Figure 6-16. Bottom alignment

The second line of the paragraph in Figure 6-16 contains two inline elements, whose bottom edges are aligned with each other. They’re also below the baseline of the text.

vertical-align: text-bottom refers to the bottom of the text in the line. For the purposes of this value, replaced elements, or any other kinds of non-text elements, are ignored. Instead, a “default” text box is considered. This default box is derived from the font-size of the parent element. The bottom of the aligned element’s inline box is then aligned with the bottom of the default text box. Thus, given the following markup, you get a result like the one shown in Figure 6-17:

img.tbot{vertical-align:text-bottom;}

<p>Here: a<imgsrc="tall.gif"style="vertical-align: middle;"alt="tall"/>image, and then a<imgsrc="short.gif"class="tbot"alt="short"/>image.</p>

Figure 6-17. Text-bottom alignment

Getting on top

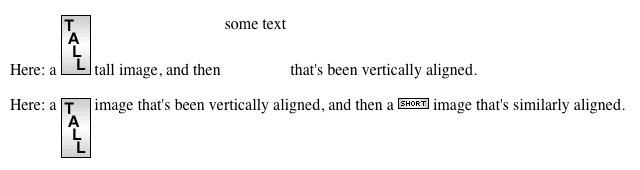

Employing vertical-align: top has the opposite effect of bottom. Likewise, vertical-align: text-top is the reverse of text-bottom. Figure 6-18 shows how the following markup would be rendered:

.up{vertical-align:top;}.textup{vertical-align:text-top;}

<p>Here: a<imgsrc="tall.gif"alt="tall image">tall image, and then<spanclass="up">some text</span>that's been vertically aligned.</p><p>Here: a<imgsrc="tall.gif"class="textup"alt="tall">image that's been vertically aligned, and then a<imgsrc="short.gif"class="textup"alt="short"/>image that's similarly aligned.</p>

Figure 6-18. Aligning with the top and text-top of a line

The exact position of this alignment will depend on which elements are in the line, how tall they are, and the size of the parent element’s font.

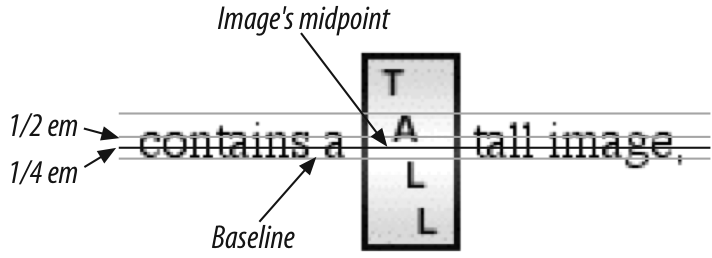

In the middle

There’s the value middle, which is usually (but not always) applied to images. It does not have the exact effect you might assume given its name. middle aligns the middle of an inline element’s box with a point that is 0.5ex above the baseline of the parent element, where 1ex is defined relative to the font-size for the parent element. Figure 6-19 shows this in more detail.

Figure 6-19. Precise detail of middle alignment

Since most user agents treat 1ex as one-half em, middle usually aligns the vertical midpoint of an element with a point one-quarter em above the parent’s baseline, though this is not a defined distance and so can vary from one user agent to another.

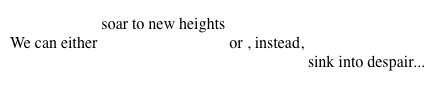

Percentages

Percentages don’t let you simulate align="middle" for images. Instead, setting a percentage value for vertical-align raises or lowers the baseline of the element (or the bottom edge of a replaced element) by the amount declared, with respect to the parent’s baseline. (The percentage you specify is calculated as a percentage of line-height for the element, not its parent.) Positive percentage values raise the element, and negative values lower it. Depending on how the text is raised or lowered, it can appear to be placed in adjacent lines, as shown in Figure 6-20, so take care when using percentage values:

sub{vertical-align:−100%;}sup{vertical-align:100%;}

<p>We can either<sup>soar to new heights</sup>or, instead,<sub>sink into despair...</sub></p>

Figure 6-20. Percentages and fun effects

Let’s consider percentage values in more detail. Assume the following:

<divstyle="font-size: 14px; line-height: 18px;">I felt that, if nothing else, I deserved a<spanstyle="vertical-align: 50%;">raise</span>for my efforts.</div>

The 50%-aligned span element has its baseline raised nine pixels, which is half of the element’s inherited line-height value of 18px, not the seven pixels that would be half the font-size.

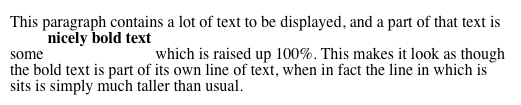

Length alignment

Finally, let’s consider vertical alignment with a specific length. vertical-align is very basic: it shifts an element up or down by the declared distance. Thus, vertical-align: 5px; will shift an element upward five pixels from its unaligned placement. Negative length values shift the element downward. This simple form of alignment did not exist in CSS1, but it was added in CSS2.

It’s important to realize that vertically aligned text does not become part of another line, nor does it overlap text in other lines. Consider Figure 6-21, in which some vertically aligned text appears in the middle of a paragraph.

Figure 6-21. Vertical alignments can cause lines to get taller

As you can see, any vertically aligned element can affect the height of the line. Recall the description of a line box, which is exactly as tall as necessary to enclose the top of the tallest inline box and the bottom of the lowest inline box. This includes inline boxes that have been shifted up or down by vertical alignment.

Word Spacing and Letter Spacing

Now that we’ve dealt with vertical alignment of inline elements, let’s return to the inline direction for a look at manipulating word and letter spacing. As usual, these properties have some nonintuitive issues.

Word Spacing

The word-spacing property accepts a positive or negative length. This length is added to the standard space between words. In effect, word-spacing is used to modify inter-word spacing. Therefore, the default value of normal is the same as setting a value of zero (0).

If you supply a positive length value, then the space between words will increase. Setting a negative value for word-spacing brings words closer together:

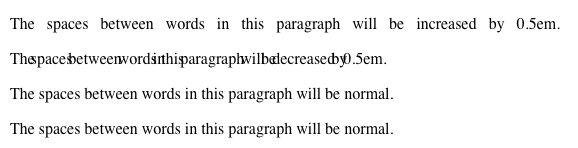

p.spread{word-spacing:0.5em;}p.tight{word-spacing:−0.5em;}p.base{word-spacing:normal;}p.norm{word-spacing:0;}

<pclass="spread">The spaces between words in this paragraph will be increased by 0.5em.</p><pclass="tight">The spaces between words in this paragraph will be decreased by 0.5em.</p><pclass="base">The spaces between words in this paragraph will be normal.</p><pclass="norm">The spaces between words in this paragraph will be normal.</p>

Manipulating these settings has the effect shown in Figure 6-22.

Figure 6-22. Changing the space between words

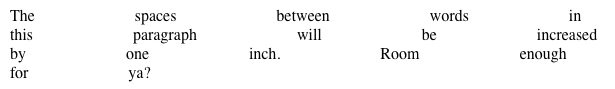

So far, I haven’t actually given you a precise definition of “word.” In the simplest CSS terms, a “word” is any string of non-whitespace characters that is surrounded by whitespace of some kind. This definition has no real semantic meaning; it simply assumes that a document contains words, each of which is surrounded by one or more whitespace characters. A CSS-aware user agent cannot be expected to decide what is a valid word in a given language and what isn’t. This definition, such as it is, means word-spacing is unlikely to work in any languages that employ pictographs, or non-Roman writing styles. The property allows you to create very unreadable documents, as Figure 6-23 makes clear. Use word-spacing with care.

Figure 6-23. Really wide word spacing

Letter Spacing

Many of the issues you encounter with word-spacing also occur with letter-spacing. The only real difference between the two is that letter-spacing modifies the space between characters or letters.

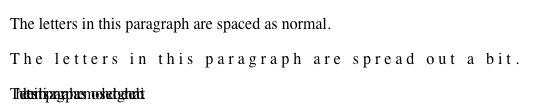

As with the word-spacing property, the permitted values of letter-spacing include any length. The default keyword is normal (making it the same as letter-spacing: 0). Any length value you enter will increase or decrease the space between letters by that amount. Figure 6-24 shows the results of the following markup:

p{letter-spacing:0;}/* identical to 'normal' */p.spacious{letter-spacing:0.25em;}p.tight{letter-spacing:−0.25em;}

<p>The letters in this paragraph are spaced as normal.</p><pclass="spacious">The letters in this paragraph are spread out a bit.</p><pclass="tight">The letters in this paragraph are a bit smashed together.</p>

Figure 6-24. Various kinds of letter spacing

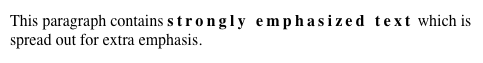

Using letter-spacing to increase emphasis is a time-honored technique. You might write the following declaration and get an effect like the one shown in Figure 6-25:

strong{letter-spacing:0.2em;}

<p>This paragraph contains<strong>strongly emphasized text</strong>which is spread out for extra emphasis.</p>

Figure 6-25. Using letter-spacing to increase emphasis

Spacing and Alignment

The value of word-spacing may be influenced by the value of the property text-align. If an element is justified, the spaces between letters and words may be altered to fit the text along the full width of the line. This may in turn alter the spacing declared by the author with word-spacing. If a length value is assigned to letter-spacing, then it cannot be changed by text-align; but if the value of letter-spacing is normal, then inter-character spacing may be changed to justify the text. CSS does not specify how the spacing should be calculated, so user agents fill it in with their own algorithms.

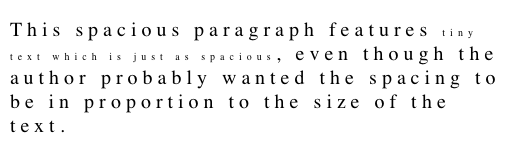

Note that the computed value is inherited, so child elements with larger or smaller text will have the same letter spacing as their parent element. You cannot define a scaling factor for word-spacing or letter-spacing to be inherited in place of the computed value (as is the case with line-height). As a result, you may run into problems such as those shown in Figure 6-26:

p{letter-spacing:0.25em;font-size:20px;}small{font-size:50%;}

<p>This spacious paragraph features<small>tiny text that is just as spacious</small>, even though the author probably wanted the spacing to be in proportion to the size of the text.</p>

Figure 6-26. Inherited letter spacing

The only way to achieve letter spacing that’s in proportion to the size of the text is to set it explicitly, as follows:

p{letter-spacing:0.25em;}small{font-size:50%;letter-spacing:0.25em;}

Text Transformation

With the alignment properties covered, let’s look at ways to manipulate the capitalization of text using the property text-transform.

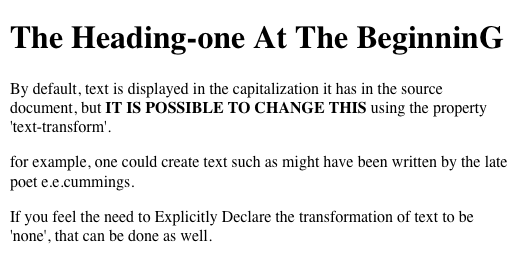

The default value none leaves the text alone and uses whatever capitalization exists in the source document. As their names imply, uppercase and lowercase convert text into all upper- or lowercase characters. Finally, capitalize capitalizes only the first letter of each word. Figure 6-27 illustrates each of these settings in a variety of ways:

h1{text-transform:capitalize;}strong{text-transform:uppercase;}p.cummings{text-transform:lowercase;}p.raw{text-transform:none;}

<h1>The heading-one at the beginninG</h1><p>By default, text is displayed in the capitalization it has in the source document, but<strong>it is possible to change this</strong>using the property 'text-transform'.</p><pclass="cummings">For example, one could Create TEXT such as might have been Written by the late Poet e.e.cummings.</p><pclass="raw">If you feel the need to Explicitly Declare the transformation of text to be 'none', that can be done as well.</p>

Figure 6-27. Various kinds of text transformation

Different user agents may have different ways of deciding where words begin and, as a result, which letters are capitalized. For example, the text “heading-one” in the h1 element, shown in Figure 6-27, could be rendered in one of two ways: “Heading-one” or “Heading-One.” CSS does not say which is correct, so either is possible.

You probably also noticed that the last letter in the h1 element in Figure 6-27 is still uppercase. This is correct: when applying a text-transform of capitalize, CSS only requires user agents to make sure the first letter of each word is capitalized. They can ignore the rest of the word.

As a property, text-transform may seem minor, but it’s very useful if you suddenly decide to capitalize all your h1 elements. Instead of individually changing the content of all your h1 elements, you can just use text-transform to make the change for you:

h1{text-transform:uppercase;}

<h1>This is an H1 element</h1>

The advantages of using text-transform are twofold. First, you only need to write a single rule to make this change, rather than changing the h1 itself. Second, if you decide later to switch from all capitals back to initial capitals, the change is even easier, as Figure 6-28 shows:

h1{text-transform:capitalize;}

<h1>This is an H1 element</h1>

Figure 6-28. Transforming an h1 element

Remember that capitalize is a simple letter substitution at the beginning of each “word.” It does not mean that common headline-capitalization conventions, such as leaving articles (“a,” “an,” “the”) all lowercase, will be enforced.

Text Decoration

Next we come to text-decoration, which is a fascinating property that offers a truckload of interesting behaviors.

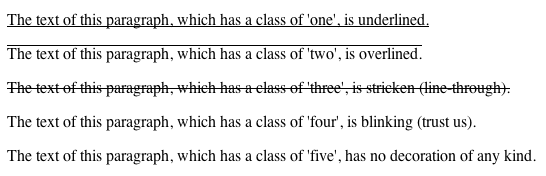

As you might expect, underline causes an element to be underlined, just like the U element in ancient HTML. overline causes the opposite effect—drawing a line across the top of the text. The value line-through draws a line straight through the middle of the text, which is also known as strikethrough text and is equivalent to the S and strike elements in HTML. blink causes the text to blink on and off, just like the much-maligned blink tag supported by Netscape. Figure 6-29 shows examples of each of these values:

p.emph{text-decoration:underline;}p.topper{text-decoration:overline;}p.old{text-decoration:line-through;}p.annoy{text-decoration:blink;}p.plain{text-decoration:none;}

Figure 6-29. Various kinds of text decoration

Note

It’s impossible to show the effect of blink in print, but it’s easy enough to imagine (perhaps all too easy). Incidentally, user agents are not required to actually blink blink text; and as of this writing, all known user agents were dropping or had dropped support for the blinking effect. (Internet Explorer never had it.)

The value none turns off any decoration that might otherwise have been applied to an element. Usually, undecorated text is the default appearance, but not always. For example, links are usually underlined by default. If you want to suppress the underlining of hyperlinks, you can use the following CSS rule to do so:

a{text-decoration:none;}

If you explicitly turn off link underlining with this sort of rule, the only visual difference between the anchors and normal text will be their color (at least by default, though there’s no ironclad guarantee that there will be a difference in their colors).

Note

Bear in mind that many users are annoyed when they realize you’ve turned off link underlining. It’s a matter of opinion, so let your own tastes be your guide, but remember: if your link colors aren’t sufficiently different from normal text, users may have a hard time finding hyperlinks in your documents, particularly users with one form or another of color blindness.

You can also combine decorations in a single rule. If you want all hyperlinks to be both underlined and overlined, the rule is:

a:link,a:visited{text-decoration:underlineoverline;}

Be careful, though: if you have two different decorations matched to the same element, the value of the rule that wins out will completely replace the value of the loser. Consider:

h2.stricken{text-decoration:line-through;}h2{text-decoration:underlineoverline;}

Given these rules, any h2 element with a class of stricken will have only a line-through decoration. The underline and overline decorations are lost, since shorthand values replace one another instead of accumulating.

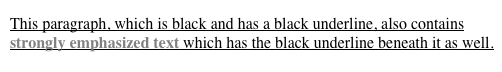

Weird Decorations

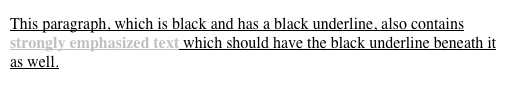

Now, let’s look into the unusual side of text-decoration. The first oddity is that text-decoration is not inherited. No inheritance implies that any decoration lines drawn with the text—under, over, or through it—will be the same color as the parent element. This is true even if the descendant elements are a different color, as depicted in Figure 6-30:

p{text-decoration:underline;color:black;}strong{color:gray;}

<p>This paragraph, which is black and has a black underline, also contains<strong>strongly emphasized text</strong>which has the black underline beneath it as well.</p>

Figure 6-30. Color consistency in underlines

Why is this so? Because the value of text-decoration is not inherited, the strong element assumes a default value of none. Therefore, the strong element has no underline. Now, there is very clearly a line under the strong element, so it seems silly to say that it has none. Nevertheless, it doesn’t. What you see under the strong element is the paragraph’s underline, which is effectively “spanning” the strong element. You can see it more clearly if you alter the styles for the boldface element, like this:

p{text-decoration:underline;color:black;}strong{color:gray;text-decoration:none;}

<p>This paragraph, which is black and has a black underline, also contains<strong>strongly emphasized text</strong>which has the black underline beneath it as well.</p>

The result is identical to the one shown in Figure 6-30, since all you’ve done is to explicitly declare what was already the case. In other words, there is no way to turn off underlining (or overlining or a line-through) generated by a parent element.

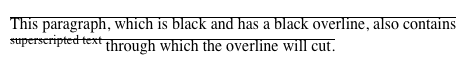

When text-decoration is combined with vertical-align, even stranger things can happen. Figure 6-31 shows one of these oddities. Since the sup element has no decoration of its own, but it is elevated within an overlined element, the overline cuts through the middle of the sup element:

p{text-decoration:overline;font-size:12pt;}sup{vertical-align:50%;font-size:12pt;}

Figure 6-31. Correct, although strange, decorative behavior

By now you may be vowing never to use text decorations because of all the problems they could create. In fact, I’ve given you the simplest possible outcomes since we’ve explored only the way things should work according to the specification. In reality, some web browsers do turn off underlining in child elements, even though they aren’t supposed to. The reason browsers violate the specification is author expectations. Consider this markup:

p{text-decoration:underline;color:black;}strong{color:silver;text-decoration:none;}

<p>This paragraph, which is black and has a black underline, also contains<strong>boldfaced text</strong>which does not have black underline beneath it.</p>

Figure 6-32 shows the display in a web browser that has switched off the underlining for the strong element.

Figure 6-32. How some browsers really behave

The caveat here is that many browsers do follow the specification, and future versions of existing browsers (or any other user agents) might one day follow the specification precisely. If you depend on using none to suppress decorations, it’s important to realize that it may come back to haunt you in the future, or even cause you problems in the present. Then again, future versions of CSS may include the means to turn off decorations without using none incorrectly, so maybe there’s hope.

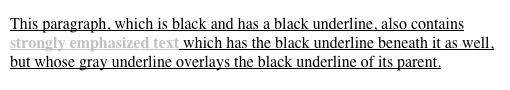

There is a way to change the color of a decoration without violating the specification. As you’ll recall, setting a text decoration on an element means that the entire element has the same color decoration, even if there are child elements of different colors. To match the decoration color with an element, you must explicitly declare its decoration, as follows:

p{text-decoration:underline;color:black;}strong{color:silver;text-decoration:underline;}

<p>This paragraph, which is black and has a black underline, also contains<strong>strongly emphasized text</strong>which has the black underline beneath it as well, but whose gray underline overlays the black underline of its parent.</p>

In Figure 6-33, the strong element is set to be gray and to have an underline. The gray underline visually “overwrites” the parent’s black underline, so the decoration’s color matches the color of the strong element.

Figure 6-33. Overcoming the default behavior of underlines

Text Rendering

A recent addition to CSS is text-rendering, which is actually an SVG property that is nevertheless treated as CSS by supporting user agents. It lets authors indicate what the user agent should prioritize when displaying text.

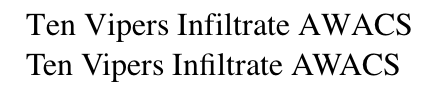

The values optimizeSpeed and optimizeLegibility are relatively self-explanatory, indicating that drawing speed should be favored over legibility features like kerning and ligatures (for optimizeSpeed) or vice versa (for optimizeLegibility).

The precise legibility features that are used with optimizeLegibility are not explicitly defined, and the text rendering often depends on the operating system on which the user agent is running, so the exact results may vary. Figure 6-34 shows text optimized for speed, and then optimized for legibility.

Figure 6-34. Different optimizations

As you can see in Figure 6-34, the differences between the two optimizations are objectively rather small, but they can have a noticeable impact on readability.

Note

Some user agents will always optimize for legibility, even when optimizing for speed. This is likely an effect of rendering speeds having gotten so fast in the past few years.

The value geometricPrecision, on the other hand, directs the user agent to draw the text as precisely as possible, such that it could be scaled up or down with no loss of fidelity. You might think that this is always the case, but not so. Some fonts change kerning or ligature effects at different text sizes, for example, providing more kerning space at smaller sizes and tightening up the kerning space as the size is increased. With geometricPrecision, those hints are ignored as the text size changes. If it helps, think of it as the user agent drawing the text as though all the text is a series of SVG paths, not font glyphs.

Even by the usual standard of web standards, the value auto is pretty vaguely defined in SVG:

the user agent shall make appropriate tradeoffs to balance speed, legibility and geometric precision, but with legibility given more importance than speed and geometric precision.

That’s it: user agents get to do what they think is appropriate, leaning towards legibility.

Text Shadows

Sometimes, you just really need your text to cast a shadow. That’s where text-shadow comes in. The syntax might look a little wacky at first, but it should become clear enough with just a little practice.

The default is to not have a drop shadow for text. Otherwise, it’s possible to define one or more shadows. Each shadow is defined by an optional color and three length values, the last of which is also optional.

The color sets the shadow’s color so it’s possible to define green, purple, or even white shadows. If the color is omitted, the shadow will be the same color as the text.

The first two length values determine the offset distance of the shadow from the text; the first is the horizontal offset and the second is the vertical offset. To define a solid, un-blurred green shadow offset five pixels to the right and half an em down from the text, as shown in Figure 6-35, you would write:

text-shadow:green5px0.5em;

Negative lengths cause the shadow to be offset to the left and upward from the original text. The following, also shown in Figure 6-35, places a light blue shadow five pixels to the left and half an em above the text:

text-shadow:rgb(128,128,255)−5px−0.5em;

Figure 6-35. Simple shadows

The optional third length value defines a blur radius for the shadow. The blur radius is defined as the distance from the shadow’s outline to the edge of the blurring effect. A radius of two pixels would result in blurring that fills the space between the shadow’s outline and the edge of the blurring. The exact blurring method is not defined, so different user agents might employ different effects. As an example, the following styles are rendered as shown in Figure 6-36:

p.cl1{color:black;text-shadow:gray2px2px4px;}p.cl2{color:white;text-shadow:004pxblack;}p.cl3{color:black;text-shadow:1em0.5em5pxred,−0.5em−1emhsla(100,75%,25%,0.33);}

Figure 6-36. Dropping shadows all over

Handling Whitespace

Now that we’ve covered a variety of ways to style the text, let’s talk about the property white-space, which affects the user agent’s handling of space, newline, and tab characters within the document source.

Using this property, you can affect how a browser treats the whitespace between words and lines of text. To a certain extent, default XHTML handling already does this: it collapses any whitespace down to a single space. So given the following markup, the rendering in a web browser would show only one space between each word and ignore the line-feed in the elements:

<p>This paragraph has many spaces in it.</p>

You can explicitly set this default behavior with the following declaration:

p{white-space:normal;}

This rule tells the browser to do as browsers have always done: discard extra whitespace. Given this value, line-feed characters (carriage returns) are converted into spaces, and any sequence of more than one space in a row is converted to a single space.

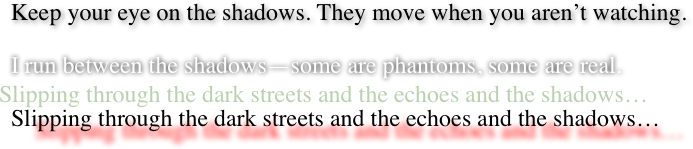

Should you set white-space to pre, however, the whitespace in an affected element is treated as though the elements were XHTML pre elements; whitespace is not ignored, as shown in Figure 6-37:

p{white-space:pre;}

<p>This paragraph has many spaces in it.</p>

Figure 6-37. Honoring the spaces in markup

With a white-space value of pre, the browser will pay attention to extra spaces and even carriage returns. In this respect, and in this respect alone, any element can be made to act like a pre element.

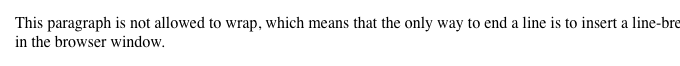

The opposite value is nowrap, which prevents text from wrapping within an element, except wherever you use a br element. Using nowrap in CSS is much like setting a table cell not to wrap in HTML 4 with <td nowrap>, except the white-space value can be applied to any element. The effects of the following markup are shown in Figure 6-38:

<pstyle="white-space: nowrap;">This paragraph is not allowed to wrap, which means that the only way to end a line is to insert a line-break element. If no such element is inserted, then the line will go forever, forcing the user to scroll horizontally to read whatever can't be initially displayed<br/>in the browser window.</p>

Figure 6-38. Suppressing line wrapping with the white-space property

You can actually use white-space to replace the nowrap attribute on table cells:

td{white-space:nowrap;}

<table><tr><td>The contents of this cell are not wrapped.</td><td>Neither are the contents of this cell.</td><td>Nor this one, or any after it, or any other cell in this table.</td><td>CSS prevents any wrapping from happening.</td></tr></table>

CSS 2.1 introduced the values pre-wrap and pre-line, which were absent in earlier versions of CSS. The effect of these values is to allow authors to better control whitespace handling.

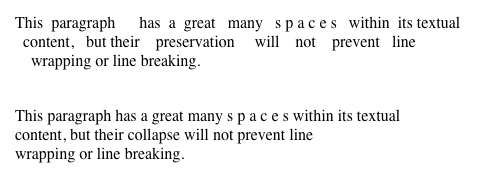

If an element is set to pre-wrap, then text within that element has whitespace sequences preserved, but text lines are wrapped normally. With this value, line-breaks in the source and those that are generated are also honored. pre-line is the opposite of pre-wrap and causes whitespace sequences to collapse as in normal text but honors new lines. For example, consider the following markup, which is illustrated in Figure 6-39:

<pstyle="white-space: pre-wrap;">This paragraph has a great many s p a c e s within its textual content, but their preservation will not prevent line wrapping or line breaking.</p><pstyle="white-space: pre-line;">This paragraph has a great many s p a c e s within its textual content, but their collapse will not prevent line wrapping or line breaking.</p>

Figure 6-39. Two different ways to handle whitespace

Table 6-1 summarizes the behaviors of white-space properties.

| Value | Whitespace | Line feeds | Auto line wrapping |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Collapsed |

Honored |

Allowed |

|

Collapsed |

Ignored |

Allowed |

|

Collapsed |

Ignored |

Prevented |

|

Preserved |

Honored |

Prevented |

|

Preserved |

Honored |

Allowed |

Setting Tab Sizes

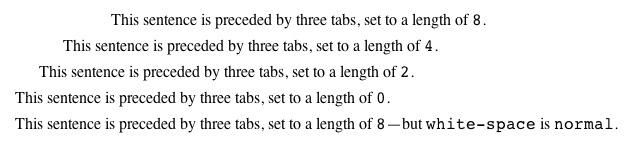

Since whitespace is preserved in some values of white-space, it stands to reason that tabs (i.e., Unicode code point 0009) will be displayed as, well, tabs. But how many spaces should each tab equal? That’s where tab-size comes in.

By default, any tab character will be treated the same as eight spaces in a row, but you can alter that by using a different integer value. Thus, tab-size: 4 will cause each tab to be rendered the same as if it were four spaces in a row.

If a length value is supplied, then each tab is rendered using that length. For example, tab-size: 10px will cause a sequence of three tabs to be rendered as 30 pixels of whitespace. The effects of the following rules is illustrated in Figure 6-40.

Figure 6-40. Differing tab lengths

Note that tab-size is effectively ignored when the value of white-space causes whitespace to be collapsed (see Table 6-1). The value will still be computed in such cases, but there will be no visible effect no matter how many tabs appear in the source.

Wrapping and Hyphenation

Hyphens can be very useful in situations where there are long words and short line lengths, such as blog posts on mobile devices and portions of The Economist. Authors can always insert their own hyphenation hints using the Unicode character U+00AD SOFT HYPHEN (or, in HTML, ­), but CSS also offers a way to enable hyphenation without littering up the document with hints.

With the default value of manual, hyphens are only inserted where there are manually-inserted hyphenation markers in the document, such as U+00AD or ­. Otherwise, no hyphenation occurs. The value none, on the other hand, suppresses any hyphenation, even if manual break markers are present; thus, U+00AD and ­ are ignored.

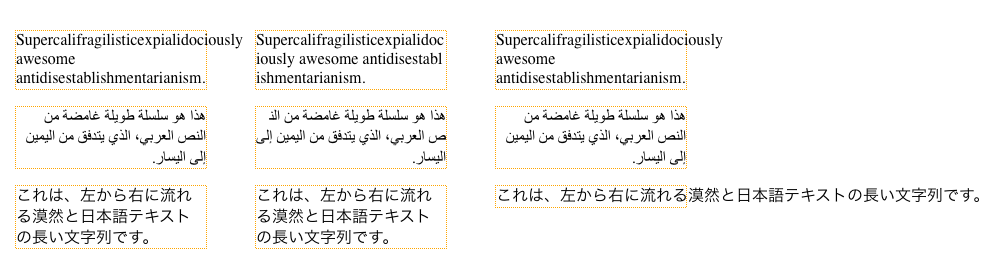

The far more interesting (and potentially inconsistent) value is auto, which permits the browser to insert hyphens and break words at “appropriate” places inside words, even where no manually inserted hyphenation breaks exist. This leads to interesting questions like what constitutes a “word” and under what circumstances it is appropriate to hyphenate a word, both of which are highly language-dependent. User agents are supposed to prefer manually inserted hyphen breaks to automatically determined breaks, but there are no guarantees. An illustration of hyphenation, or the suppression thereof, in the following example is shown in Figure 6-41:

.cl01{hyphens:auto;}.cl02{hyphens:manual;}.cl03{hyphens:none;}

<pclass="cl01">Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious antidisestablishmentarian ism.</p><pclass="cl02">Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious antidisestablishmentarian ism.</p><pclass="cl02">Super­cali­fragi­listic­expi­ali­docious anti­dis­establish­ment­arian­ism.</p><pclass="cl03">Super­cali­fragi­listic­expi­ali­docious anti­dis­establish­ment­arian­ism.</p>

Figure 6-41. Hyphenation results

Because hyphenation is so language-dependent, and because the CSS specification does not define precise (or even vague) rules regarding how user agents should carry out hyphenation, there is every chance that hyphenation will be different from one browser to the next.

Furthermore, if you do choose to hyphenate, be careful about the elements to which you apply the hyphenation. hyphens is an inherited property, so declaring body {hyphens: auto;} will apply hyphenation to everything in your document—including textareas, code samples, block quotes, and so on. Blocking automatic hyphenation at the level of those elements is probably a good idea, using rules something like this:

body{hyphens:auto;}code,var,kbd,samp,tt,dir,listing,plaintext,xmp,abbr,acronym,blockquote,q,textarea,input,option{hyphens:manual;}

It’s probably obvious why suppressing hyphenation in code samples and code blocks is desirable, especially in languages that use hyphens in things like property and value names. (Ahem.) Similar logic holds for keyboard input text—you definitely don’t want a stray dash getting into your Unix command-line examples! And so on down the line. If you decide that you want to hyphenate some of these elements, just remove them from the selector. (It can be kind of fun to watch the text you’re typing into a textarea get auto-hyphenated as you type it.)

Warning

As of late 2017, hyphens was supported by all major desktop browsers except Chrome/Blink, and required vendor prefixes in Safari and Edge. As noted, such support is always language-dependent.

Hyphens can be suppressed by the effects of other properties, such as word-break, which affects how soft wrapping of text is calculated in various languages.

When a run of text is too long to fit into a single line, it is soft wrapped. This is in contrast to hard wraps, which are things like line-feed characters and <br> elements. Where the text is soft wrapped is determined by the user agent (or the OS it uses), but word-break lets authors influence its decision-making.

The default value of normal means that text should be wrapped like it always has been. In practical terms, this means that text is broken between words, though the definition of a word varies by language. In Latin-derived languages like English, this is almost always a space between letter sequences (e.g., words). In ideographic languages like Japanese, each symbol is a word, so breaks can occur between any two symbols. In other CJK languages, though, the soft-wrap points may be limited to appear between sequences of symbols that are not space-separated.

Again, that’s all by default, and is the way browsers have handled text for years. If you apply the value break-all, then soft wrapping can (and will) occur between any two characters, even if they are in the middle of a word. With this value, no hyphens are shown, even if the soft wrapping occurs at a hyphenation point (see hyphens, earlier). Note that values of the line-break property (described next) can affect the behavior of break-all in CJK text.

keep-all, on the other hand, suppresses soft wrapping between characters, even in CJK languages where each symbol is a word. Thus, in Japanese, a sequence of symbols with no whitespace will not be soft wrapped, even if this means the text line will exceed the length of its element. (This behavior is similar to white-space: pre.)

Figure 6-42 shows a few examples of word-break values, and Table 6-2 summarizes the effects of each value.

Figure 6-42. Altering word-breaking behavior

| Value | Non-CJK | CJK | Hyphenation permitted |

|---|---|---|---|

|

As usual |

As usual |

Yes |

|

After any character |

After any character |

No |

|

As usual |

Around sequences |

Yes |

If your interests run to CJK text, then in addition to word-break you will also want to get to know line-break.

As we just saw, word-break can affect how lines of text are soft wrapped in CJK text. The line-break property also affects such soft wrapping, specifically how wrapping is handled around CJK-specific symbols and around non-CJK punctuation (such as exclamation points, hyphens, and ellipses) that appears in text declared to be CJK.

In other words, line-break applies to certain CJK characters all the time, regardless of the content’s declared language. If you throw some CJK characters into a paragraph of English text, line-break will still apply to them, but not to anything else in the text. Conversely, if you declare content to be in a CJK language, line-break will continue to apply to those CJK characters plus a number of non-CJK characters within the CJK text. These include punctuation marks, currency symbols, and a few other symbols.

There is no authoritative list of which characters are affected and which are not, but the specification provides a list of recommended symbols and behaviors around those symbols.

The default value auto allows user agents to soft wrap text as they like, and more importantly lets UAs vary the line breaking they do based on the situation. For example, the UA can use looser line-breaking rules for short lines of text and stricter rules for long lines. In effect, auto allows the user agent to switch between the loose, normal, and strict values as needed, possibly even on a line-by-line basis within a single element.

Doubtless you can infer that those other values have the following general meanings:

loose-

This value imposes the “least restrictive” rules for wrapping text, and is meant for use when line lengths are short, such as in newspapers.

normal-

This value imposes the “most common” rules for wrapping text. What exactly “most common” means is not precisely defined, though there is the aforementioned list of recommended behaviors.

strict-

This value imposes the “most stringent” rules for wrapping text. Again, this is not precisely defined.

Wrapping Text

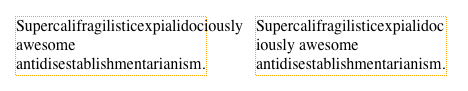

After all that information about hyphenation and soft wrapping, what happens when text overflows its container anyway? That’s what overflow-wrap addresses.

This property couldn’t be more straightforward. If the default value of normal is in effect, then wrapping happens as normal; which is to say, between words or as directed by the language. If break-word is in effect, then wrapping can happen in the middle of words. Figure 6-43 illustrates the difference.

Figure 6-43. Overflow wrapping

Note

Note that overflow-wrap can only operate if the value of white-space allows line wrapping. If it does not (e.g., with the value pre), then overflow-wrap has no effect.

Where overflow-wrap gets complicated is in its history and implementation. Once upon a time there was a property called word-wrap that did exactly what overflow-wrap does. The two are so identical that the specification specifically states that user agents “must treat word-wrap as an alternate name for the overflow-wrap property, as if it were a shorthand of overflow-wrap.”

Sadly, browsers didn’t always do this, and word-wrap was better supported. For this reason, it’s common to use both for backward compatibility:

pre{word-wrap:break-word;overflow-wrap:break-word;}

As of late 2017, overflow-wrap enjoys very widespread supports, so it’s pretty safe to use.

While overflow-wrap: break-word may appear very similar to word-break: break-all, they are not the same thing. To see why, compare the second box in Figure 6-43 to the top middle box in Figure 6-42. As it shows, overflow-wrap only kicks in if content actually overflows; thus, when there is an opportunity to use whitespace in the source to wrap lines, overflow-wrap will take it. By contrast, word-break: break-all will cause wrapping when content reaches the wrapping edge, regardless of any whitespace that comes earlier in the line.

Writing Modes

If you’re reading this book in English or any number of other mainly Western languages, then you’re reading the text left to right and top to bottom, which is the flow direction of English. Not every language runs this way. There are many right-to-left and top-to-bottom languages such as Hebrew and Arabic, and many languages that can be written primarily top-to-bottom. Some of the latter are secondarily left to right, such as Chinese and Japanese, whereas others are right to left, like Mongolian.

Setting Writing Modes

The property used for specifying one of the three available writing mode is, of all things, writing-mode.

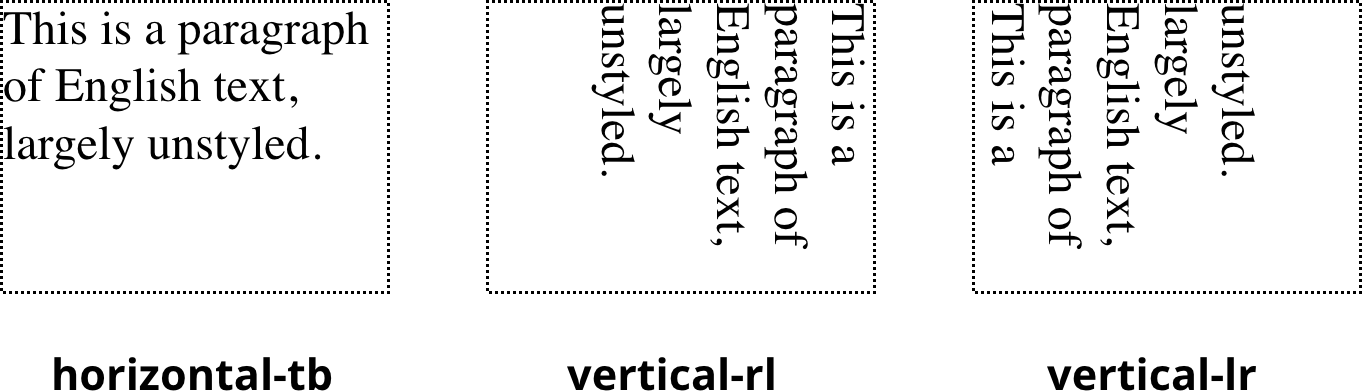

The default value, horizontal-tb, means “a horizontal inline direction, and a top-to-bottom block direction.” This covers all Western and some Middle Eastern languages, which may differ in the direction of their horizontal writing. The other two values offer a vertical inline direction, and either a right-to-left or left-to-right block direction. All three are illustrated in Figure 6-44.

Figure 6-44. Writing modes

Notice how the lines are strung together in the two vertical examples. If you tilt your head to the right, the text in vertical-rl is at least readable. The text in vertical-lr, on the other hand, is difficult to read because it appears to flow from bottom to top, at least when arranging English text. This is not a problem in languages which actually use vertical-lr flow, such as form of Japanese. As of late 2017, vertical flows can only have the inline direction go from top to bottom.

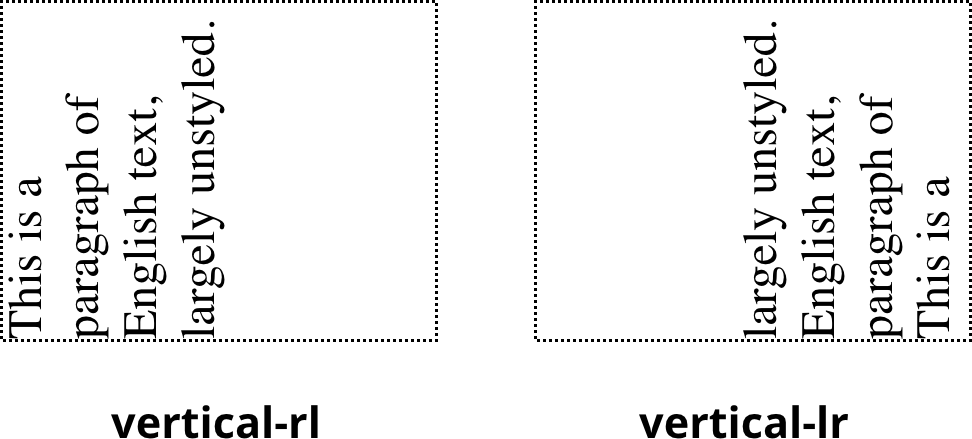

It is possible to create bottom-to-top vertical flows of Western-language text by applying vertical-rl to an element and then rotating the element 180 degrees with CSS Transforms (see Chapter 16). This presents a bottom-to-top, left-to-right visual flow. Using vertical-lr and rotating it creates a bottom-to-top, right-to-left flow. Both are illustrated in Figure 6-45:

.flip{transform:rotate(180deg);}#one{writing-mode:vertical-rl;}#two{writing-mode:vertical-lr;}

Figure 6-45. Flipping vertical writing modes

The challenge of working with text like that is that everything is flipped, which means what we see is at odds with what’s actually happening. The text of vertical-rl (vertical-right-to-left) is visually progressing left to right, for example.

The same problem arises when applying inline block-alignment properties such as vertical-align. In vertical writing modes, the block direction is horizontal, which means vertical alignment of inline elements actually causes them to move horizontally. This is illustrated in Figure 6-46.

Figure 6-46. Writing modes and “vertical” alignment

All the super- and subscript elements cause horizontal shifts, both of themselves and the placement of the lines they occupy, even through the property used to move them is vertical-align. As described earlier, the vertical displacement is with respect to the line box, where the box’s baseline is defined as horizontal—even when it’s being drawn vertically.

Confused? It’s OK. Writing modes are likely to confuse you, because it’s such a different way of thinking and because old assumptions in the CSS specification clash with the new capabilities. If there had been vertical writing modes from the outset, vertical-align would likely have a different name—inline-align or something like that. (Maybe one day that will happen.)

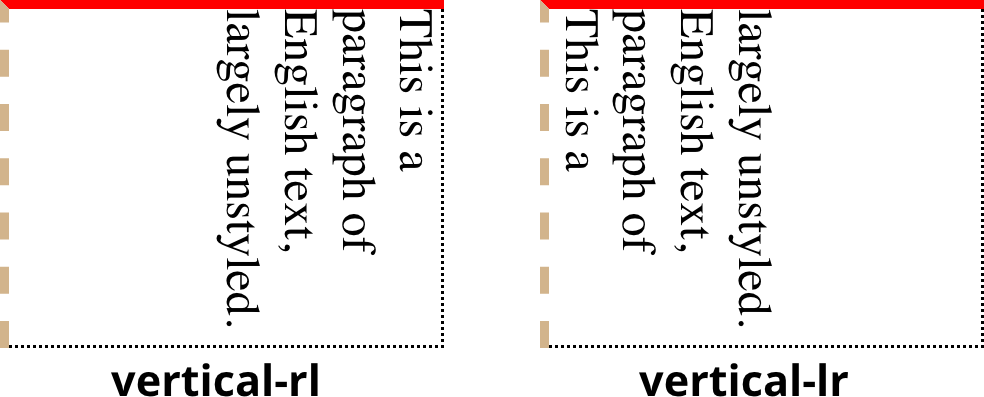

One last note: if you’re already used to CSS Transforms, you might be tempted to think of these vertical writing modes as equivalent to rotating the text 90 degrees. They are not the same, for two reasons. One, this only appears to be the case for vertical-rl; vertical-lr has the look of text that flows “bottom to top.” Two, the cardinal points don’t change when flowing text vertically. The top is still the top, in other words. This is illustrated by the following styles, whose results are depicted in Figure 6-47:

.boxed{border-top:3pxsolidred;border-left:3pxdashedtan;}#one{writing-mode:vertical-rl;}#two{writing-mode:vertical-lr;}

Figure 6-47. Writing modes and the “cardinal” directions of CSS

In both cases, the top border is solid red, and the left border is dashed tan. The cardinal points don’t rotate with the text—because the text isn’t rotated. It’s being flowed in a different way.

Now here’s where it gets unusual. While the borders don’t migrate around the element box, margins can, but not due to anything in the CSS specification.

This happens because user agents (at least as of late 2017) maintain internal styles that relate to the start and end of the element in the block direction. In languages that flow top to bottom, then the start and end of the element’s block direction are its top and bottom sides. But in vertical writing, the block direction is right to left or left to right. Thus, you can set up a bunch of paragraphs to flow vertically, and if you leave the margins alone, what would normally be top and bottom margins will become left and right margins. You can see this effect in Figure 6-48, which illustrated the result of the following styles:

p{margin-top:1em;}#one{writing-mode:vertical-rl;}#two{writing-mode:vertical-lr;}

Figure 6-48. The placement of UA default margins

There are the top margins, as declared, right along the tops of the two paragraphs. The empty space to the side of each paragraph is created by the block-start and block-end margins. If we explicitly set the right and left margins to zero, then the space between the paragraphs would be removed.

Remember: this happens because user agents, by default, represent the margins of text elements using properties like block-start-margin (which is not an actual property in CSS, at least not yet). If you explicitly set top, bottom, or side margins using properties like margin-top, then they will be applied to the element box just as borders were: top margin on top, right margin to the right, and so on.

Changing Text Orientation

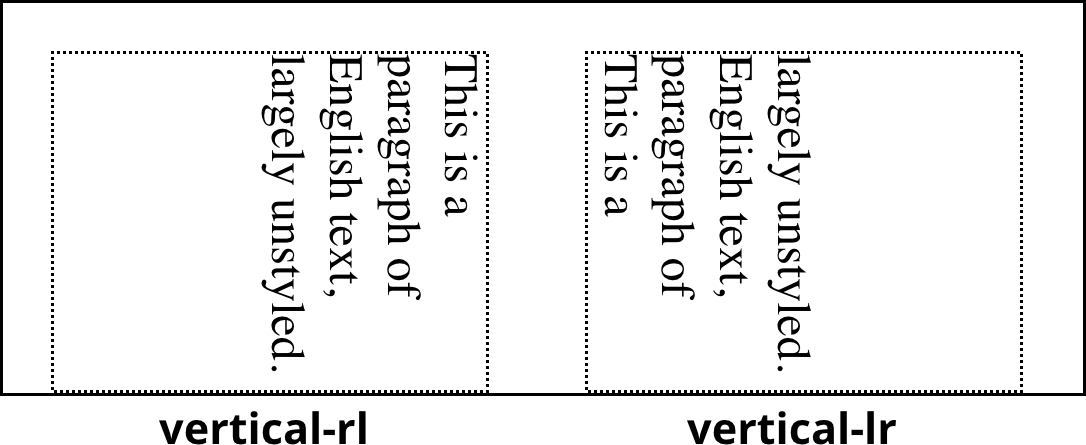

Once you’ve settled on a writing mode, you may decide you want to change the orientation of characters within those lines of text. There are many reasons you might want to do this, not least of which are situations where different writing systems are commingled, such as Japanese text with English words or numbers mixed in. In these cases, text-orientation is the answer.

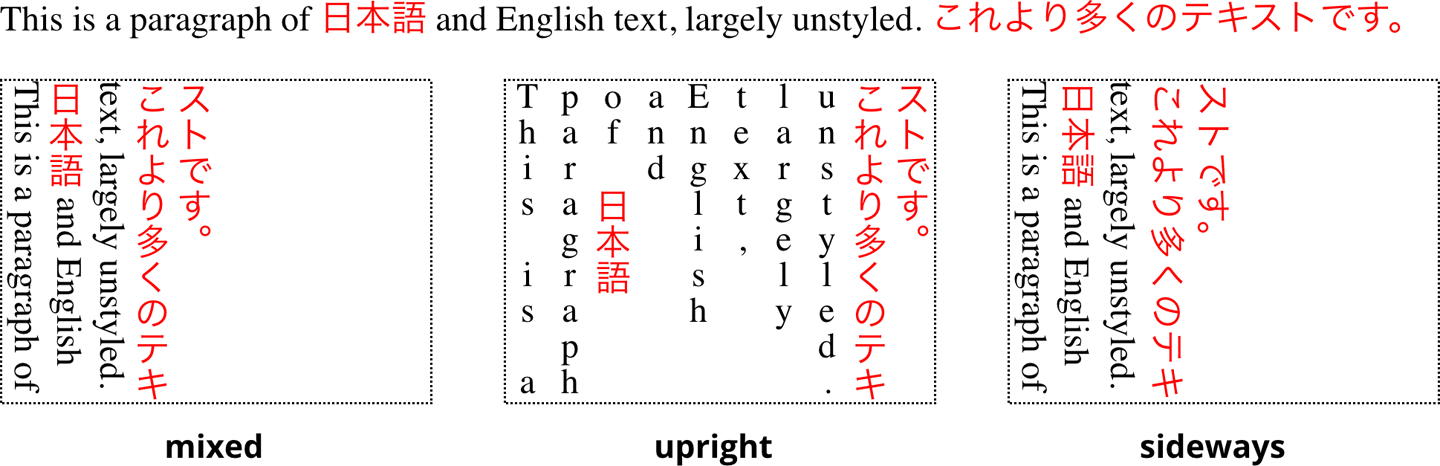

The effect of text-orientation is to affect how characters are oriented. What that means is best illustrated by the following styles, rendered in Figure 6-49:

.verts{writing-mode:vertical-lr;}#one{text-orientation:mixed;}#two{text-orientation:upright;}#thr{text-orientation:sideways;}

Figure 6-49. Text orientation

Across the top of Figure 6-49 is a basically unstyled paragraph of mixed Japanese and English text. Below that, three copies of that paragraph, using the writing mode vertical-lr. In the first of the three, text-orientation: mixed, writes the horizontal-script characters (the English) sideways, and the vertical-script characters (the Japanese) upright. In the second, all characters are upright, including the English characters. In the third, all characters are sideways, including the Japanese characters.

Declaring Direction

Harking back to the days of CSS2, there are a pair of properties that can be used to affect the direction of text by changing the inline baseline direction: direction and unicode-bidi.

Warning

The CSS specification explicitly warns against using direction and unicode-bidi in CSS when applied to HTML documents. To quote: “Because HTML [user agents] can turn off CSS styling, we recommend…the HTML dir attribute and <bdo> element to ensure correct bidirectional layout in the absence of a style sheet.” The properties are covered here because they may appear in legacy stylesheets.

The direction property affects the writing direction of text in a block-level element, the direction of table column layout, the direction in which content horizontally overflows its element box, and the position of the last line of a fully justified element. For inline elements, direction applies only if the property unicode-bidi is set to either embed or bidi-override (See the following description of unicode-bidi).

Although ltr is the default, it is expected that if a browser is displaying right-to-left text, the value will be changed to rtl. Thus, a browser might carry an internal rule stating something like the following:

*:lang(ar),*:lang(he){direction:rtl;}

The real rule would be longer and encompass all right-to-left languages, not just Arabic and Hebrew, but it illustrates the point.

While CSS attempts to address writing direction, Unicode has a much more robust method for handling directionality. With the property unicode-bidi, CSS authors can take advantage of some of Unicode’s capabilities.

Here we’ll simply quote the value descriptions from the CSS 2.1 specification, which do a good job of capturing the essence of each value:

normal-

The element does not open an additional level of embedding with respect to the bidirectional algorithm. For inline-level elements, implicit reordering works across element boundaries.

embed-

If the element is inline-level, this value opens an additional level of embedding with respect to the bidirectional algorithm. The direction of this embedding level is given by the

directionproperty. Inside the element, reordering is done implicitly. This corresponds to adding an LRE (U+202A; fordirection: ltr) or an RLE (U+202B; fordirection: rtl) at the start of the element and a PDF (U+202C) at the end of the element. bidi-override-

This creates an override for inline-level elements. For block-level elements, this creates an override for inline-level descendants not within another block. This means that, inside the element, reordering is strictly in sequence according to the

directionproperty; the implicit part of the bidirectional algorithm is ignored. This corresponds to adding an LRO (U+202D; fordirection: ltr) or RLO (U+202E; fordirection: rtl) at the start of the element and a PDF (U+202C) at the end of the element.

Summary

Even without altering the font face, there are many ways to change the appearance of text. There are classic effects such as underlining, but CSS also enables you to draw lines over text or through it, change the amount of space between words and letters, indent the first line of a paragraph (or other block-level element), align text in various ways, exert influence over the hyphenation and line breaking of text, and much more. You can even alter the amount of space between lines of text. There is also support in CSS for languages other than those that are written left-to-right, top-to-bottom. Given that so much of the web is text, the strength of these properties makes a great deal of sense. Recent developments in improving text legibility and placement are likely only the beginnings of what we will eventually be able to do with text styling.