CHAPTER 1

Stand Up for Yourself—Posture and Personality

“The way you walk through a room is the way you walk through life.”

—Ida Rolf, founder of Rolfing Structural Integration

Your movement is literally an expression of the way in which you think and feel. Have you ever noticed a random guy approach a beautiful girl (or vice versa) in a coffee shop and curiously observed the dynamic? You can tell from across the room if he feels confident in his approach and simultaneously see if she believes he’s a viable mate worthy of sharing her coveted digits with based purely on the dynamics of their movement. Is this because you’ve been endowed with telepathic superpowers, or could it be that you’re reading their body language? A fascinating study conducted by researchers at Ohio State University showed how posture during communication not only informs the way others perceive you, but may even shape your own self-belief.1 They asked study participants to list three positive and three negative traits they possess that would impact their professional performance at a future job. Half of the participants were asked to write these traits while they were in a hunched-over position, while the other half were asked to assume an upright posture during the process.

The results were striking. Their posture not only impacted whether or not they identified with the positive things they were asked to write about themselves, but also affected a participant’s belief in the statements, positive or negative. That’s right: A person’s belief of their own words is associated with their postural position while thinking them. When you’re in a hunched-over position, you may begin to distrust yourself, in the same way others would distrust the level of confidence in your statements.

Along with affecting the way you think about yourself, your postural patterns even impact the filter in which you access memories. A study conducted at San Francisco State University by professor of health education Erik Peper showed that more than 85 percent of the time, students found it easier to access uplifting memories in an upright (aligned) position and, reciprocally, easier to access depressive memories in a slumped posture.2 Peper suggested, “You can take charge of yourself. Put yourself in an empowering, upright position. Remember that our thoughts and emotions are represented in our bodies. And vice versa: Our bodies can change our thoughts.”

Throughout the book, I use “mind” and “body” as two separate words regularly: this is a limitation in language, not the reality of the human experience. In my career, I’ve yet to meet a person whose physical patterns did not relate to their history and personality or whose overall muscular tone did not match their temperament. If you’re feeling tense or anxious, your muscles are tense and anxious. If you feel calm and relaxed, you can imagine the effect on your soft tissues. Here’s a nice insight on trauma expressing itself in the body from one of the seminal books on this mind-body relationship, The Body Keeps the Score, by Bessel van der Kolk, MD:

Trauma victims cannot recover until they become familiar with and befriend the sensations in their bodies. Being frightened means you live in a body that is always on guard. Angry people live in angry bodies. The bodies of childhood victims are tense and offensive until they find a way to relax and feel safe. In order to change, people need to become aware of their sensations and the way that their bodies interact with the world around them. Physical self-awareness is the first step in releasing the tyranny of the past.3

Let’s repeat that: “Physical self-awareness is the first step in releasing the tyranny of the past.” Upon gaining a relationship with your physical experience, you are simultaneously taking steps to gain control of your mental and emotional self.

Your body has an immediate physical reaction to thoughts and experiences. This is a good thing: The problem arises when a traumatic experience causes the body to contract and the afflicted individual lacks the space, resources, or know-how to naturally reset their nervous system back to a baseline of homeostasis.

In the book Waking the Tiger, master somatic therapist Peter Levine discusses the natural responses various animals display after being immobilized by stress: They literally shake it off in a self-soothing process before getting back to their daily grind. Imagine a zebra just barely making it out of the clutches of a hungry lion: The stress of the situation needs to go somewhere after the escape. The tremors following the close call for the zebra are part of the process of discharging stress, a reboot for the nervous system bringing the frightened animal back to a healthy baseline. If the process is interrupted, Levine goes on to write, the stress is not released from the body, health problems will ensue, and the symptoms will not go away until the responses are discharged and the process of releasing the stress is completed.4

Humans, on the other hand, experience stressful “micro-traumas” each day in the form of rejection, noise pollution, minor accidents, the mechanical stress of moving with imbalanced postures, or anything that induces a sense of anxiety or fear in the organism. The short-term solution for many people is to keep pushing on instead of allowing a moment to fully shake off the newfound stress formed in the body, leaving their physiology assuming a lion is still hanging off their backs as they forge forward into the tasks of the day.

Most folks can make it through their lives with a few small lions (imbalanced postural patterns, financial, relationship, or environmental stressors, etc.) continually hanging on and slowly draining energy, but thankfully we have Starbucks (sarcasm) to keep us moving across the savanna (no wonder Americans spent $74.2 billion in 2015 on coffee alone).5 If we don’t pay attention to shaking these hungry carnivores off, they’ll add up, and before we know it our precious bodies begin succumbing to postural collapse, sleep disruption, joint pain, unhealthy food cravings, dis-ease, and a mind partial to negative self-talk.

There’s a solution to this: Shake these daily metaphoric lion attacks from your back as they happen instead of allowing them to add up and compromise your ability to maintain control of your own body. The principles outlined in the coming chapters will offer you the necessary tools to unravel the day’s stressors via simple adjustments to your environment and subtle shifts in your physical inhabitance to shake any clinging lions (stressors) and prevent future attacks.

ALIGN YOURSELF

After something stressful takes place in your day (lion attack of any shape or size), take a beat to reset before entering into your next appointment, conversation, or event of the day. Call a time-out and observe yourself by slowly using this modification of a box-style breathing pattern: Breathe in for four seconds, hold for four seconds, breathe out for six seconds, hold for four seconds. Repeat this pattern six times. I’ve found the extra time breathing out assists in down-regulating the nervous system into a calmer state than the traditional four-by-four-by-four-by-four-style box breathing. Compound the stress-reducing variables by taking a walk outside as you follow the breath practice. For bonus destressing points, feel free to jump, wiggle, vibrate, twist, and turn your body while you’re on your walk.

MOVING YOUR PHYSIOLOGY

“It’s easier to act your way into a new way of thinking than to think your way into a new way of acting.”

—Millard Fuller, founder of Habitat for Humanity

Now, where the conversation gets intriguing is when we realize our postural patterns appear to have deep physiological ramifications. It’s as though our endocrine system is deciphering our postural positions like a person reading braille and actually changing our mood based on the signaling of our movement.

It appears your hormones may act like messengers between your postural patterns and the state you experience. A trio of social psychology professors—Amy Cuddy from Harvard, Andy Nap from Yale, and Dana Carney from the University of California, Berkeley—explored this idea in 2010 when they popularized the idea of “high-power poses,” which were shown to boost levels of testosterone by around 20 percent and reduce cortisol (a stress hormone) levels by 25 percent after spending just two minutes in them. Inversely, the researchers found that “low-power poses” (e.g., hunching over to scroll on your phone) increased cortisol levels and decreased testosterone.6 This study was a testament to the speed at which the body is continually processing postural information into chemical stimuli: Your cells are always listening.

In Cuddy’s TED Talk (at the date of writing, the second most viewed one of all time), she describes the power of “faking it until you make it,” suggesting that you can literally change the way you feel and behave based upon the way you organize your physical body.7 This particular study has gone through an immense amount of scrutiny, in large part due to its popularity. A paper came out in 2017 refuting Cuddy’s findings,8 and then another in 2018 reaffirmed the concept referred to as “postural feedback.”9 At this point, it’s fairly indisputable that the way you move (or don’t) affects the way you feel, and the way you feel is inseparably tied to the expression of your internal chemistry. Envision a weight lifter hyping themselves up before stepping onto a platform or a UFC fighter strutting into an octagon as a display of dominance. Research on these miraculous moments can be challenging because life doesn’t happen in a controlled, double-blind, static, sterile laboratory setting, and thus these debates will likely continue.

An issue with faking a powerful pose does arise when the focus is solely on the upper body—the trick is to find alignment (power) from feet to head. When people pull their shoulders back to pretend a power pose, they typically end up jamming their low back into an unstable hyperlordotic (or overly arched) position that is unfortunately not very powerful at all. It can create the appearance of confident readiness but will not be stable or sustainable without a strong foundation of regular full-body integration—as the body neutralizes back to its habituated posture, the confidence boost you wanted recedes, too. Throughout this book, you will learn the fundamental movement and lifestyle practices to create long-term structural change in your body so there’s nothing to fake, and you can feel strong and confident from the ground up.

ALIGN YOURSELF

If you’re anything like me, you’ll find it a bit funny to stand like Wonder Woman for a couple of minutes contemplating how awesome you are. Instead, try hanging from a pull-up bar, jungle gym, or even a strong tree branch to lengthen your body into the same position. This will give you the gratification of restoring optimal shoulder function (more on this in Chapter 7), while also creating an emotional pick-me-up. Remember, hanging can be playful; if you’re physically able, make a point to climb a tree or jungle gym every now and again. Allow yourself to enjoy a little childlike movement and remember to smile, because that too profoundly improves your physiological state!

DO YOU SPEAK MOVEMENT?

“Our bodies are apt to be our autobiographies.”

—Frank Gillette Burgess

You’ve almost certainly heard the term “body language,” but have you ever really thought its meaning through? Turns out, we communicate with each other nonverbally all the time. UCLA professor Albert Mehrabian coined the famous 7/38/55 ratio of our communication back in the seventies, showing that most of what we say to each other is actually conveyed via our body language and the tonality of our voice rather than the words themselves.10 Mehrabian found about 55 percent of our communication is body language, 38 percent is voice tonality, and only 7 percent is conveyed through the literal words spoken.11

This is obviously difficult to quantify exactly, and Mehrabian himself cautioned that his experiments were limited to feelings and attitudes, particularly when there were incongruences: If the body language and words disagree, one will tend to trust the body. Thus, closely observing what your body is saying is wise if you care about clearly expressing yourself.

Learning to speak more effectively with your movement will not only make you a better orator, it may very well save your life (or at least your wallet) someday.

In a study from 1981, researchers Betty Grayson and Morris I. Stein asked criminals convicted of violent offenses to watch a video of pedestrians walking down a busy city sidewalk and point out who would be a likely target. It only took seconds to point the potential victims out, and the results were consistent among all the convicts. What were the patterns these clueless pedestrians were exhibiting, you ask?

It wasn’t their race, gender, age, or even size—it was the way in which they moved! Researchers determined it was nonverbal cues such as their pace of walking, length of stride, posture, body language, and awareness of the environment. One of the primary precipitators of attracting unwanted attention from a predator is a walking style lacking what researchers called “wholeness”—what we refer to in this book as integration.12 If your body appears disorganized in the way you move, it’s perceived as weakness and makes you more likely to be exploited. That’s why realigning your movement is so important: Balancing your body parts allows you to exude strength and confidence, attracting the right people into your life and dispelling the wrong ones, even when you don’t realize it’s happening.

ALIGN YOURSELF

Move the way you want to feel. This is a three-step process that will take some thinking outside of the traditional box for some.

Step one: Think about how you would like to feel. It could be strong, confident, humble, graceful, powerful, flexible, aggressive, humorous, light, or anything of the sort.

Step two: Visualize the way your body moves when you feel this way, and be specific. Notice how your arms and legs swing when you walk, how you sit, stand, breathe, communicate, and even the tone and pace of your voice.

Step three: Take a walk and explore moving in the way you just visualized. How does it feel? Start actively thinking about moving more this way as often as is reasonable, choose sports or activities that promote this style of movement, and begin to notice how your postural patterns affect the way you think and feel.

FACIAL FLEXIBILITY

If your overall posture affects how you feel, what do all of those face muscles do? Have you ever thought about why you have such a complex facial structure continually contorting into all those strange positions? It has something to do with that 55 percent of our communication coming from body language: As most would agree, a single facial expression really can tell a thousand words. Paul Ekman, emeritus professor of psychology at the University of California, San Francisco, has spent more than forty years exploring this topic all across the globe. In a past podcast episode, he and I discussed how he found humans to utilize more than 10,000 facial expressions in conversation, all with subtle and specific meanings.13 The forty-three muscles of the face have an exponential capacity to convey distinct messages—more honestly than the actual words coming out of your mouth.

Take, for example, the vast difference in meaning between a diabolical, expressionless smile involving only the muscles around the mouth (zygomatic major muscles) compared to a person gleaming with their eye muscles as well (orbicularis oculi). This more honest-appearing smile is referred to as the Duchenne smile, named after the French anatomist Guillaume Duchenne, and is sometimes referred to as “smizing,” as in smiling with your eyes. It sends the signal you are safe and honest; a smile without the eyes tells people you may be faking it and up to something suspicious.

So what does this mean for plastic surgery? you may be thinking. In one study using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans, researchers discovered less activation in areas of the brain used to interpret and modulate emotional states in people who had had Botox injections. This means your facial expressions are like emotional conductors, and your ability to play your own internal orchestra of sensation is associated to your facial (and postural) mobility.14 This phenomenon is referred to as the “facial feedback hypothesis” and suggests the control of facial expression produces parallel effects on subjective feelings. This suggests that in order to empathize with another human being, it’s helpful to literally form yourself to the shape of their present state to truly feel for them.

That’s right, even empathy could be likened to a form of fitness—greater movement competence through a wider range of postural and facial expressions allows a person to connect more deeply to a broader population, because each person moves a little bit differently. If you can match your movement expression to another’s like a key in a lock, they will feel seen and felt by you. This gives new meaning to Louis Armstrong’s iconic song lyric “When you’re smiling, the whole world smiles with you,” although perhaps “when you’re smizing, the whole world smizes with you” may lead to a more joyous outcome.

Are these facial expressions universally consistent, indicating the way you move your muscles to express emotion is not learned, but rather is integrated deep into human psychobiology? Charles Darwin was convinced our facial expressions were distinct to each culture, but Paul Ekman was not. He traveled to Papua New Guinea in the late sixties to visit the Fore people, a tribe without any exposure to outside influence. Just as Ekman anticipated, their expressions were interpreted the same way as they would be by any Westerner. This is yet another example of our postural expression underlying the superficial accoutrements of spoken language. Your movement is the mainframe of effective communication and largely defines your own inner self-talk.

POSTURAL ARCHETYPES

“A purely disembodied human emotion is a nonentity.”

—William James

You can usually assess a person’s mood by looking at their posture, and you can even alter your own state by simply changing the shape of the way you stand. William James, often referred to as the father of American psychology, famously proposed that emotional experiences are perceptions of bodily processes. What the heck does that mean? He described it this way: “Common sense says, we lose our fortune, are sorry and weep; we meet a bear, are frightened and run; we are insulted by a rival, are angry and strike. The hypothesis here to be defended says that this order of sequence is incorrect, that the one mental state is not immediately induced by the other, that the bodily manifestations must first be interposed between, and that the more rational statement is that we feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble, and not that we cry, strike, or tremble because we are sorry, angry, or fearful, as the case may be. Without the bodily states following on the perception, the latter would be purely cognitive in form, pale, colourless, destitute of emotional warmth. We might then see the bear, and judge it best to run, receive the insult and deem it right to strike, but we could not actually feel afraid or angry.”

James hypothesized this idea before seeing the present-day research that shows how simply holding a pencil in a person’s teeth to induce a mechanical smile engenders a sensation of happiness15 and furrowing someone’s brow into the shape of a frown with a golf tee gives rise to sadness.16 That’s not to mention the effect temporary facial paralysis (e.g., Botox), as discussed previously, may have on a person’s ability to fully interpret and feel emotions. (Side note: This chapter is clearly biased toward physical movement being a primary catalyst for one’s internal experience. Evidence and logic suggests it’s a two-way relationship—in Chapter 18, on mindfulness, we will dive deeper into how one’s internal state shapes their physical structure.)

Let’s now take a look at the five most common postural archetypes. We will detail them from an anatomical perspective and describe the personality type most commonly associated with each postural pattern. The majority of people will identify with a combination of the archetypes, with one or two standing out most prominently. Every person has the opportunity to find greater alignment in themselves by following the steps outlined in the coming chapters.

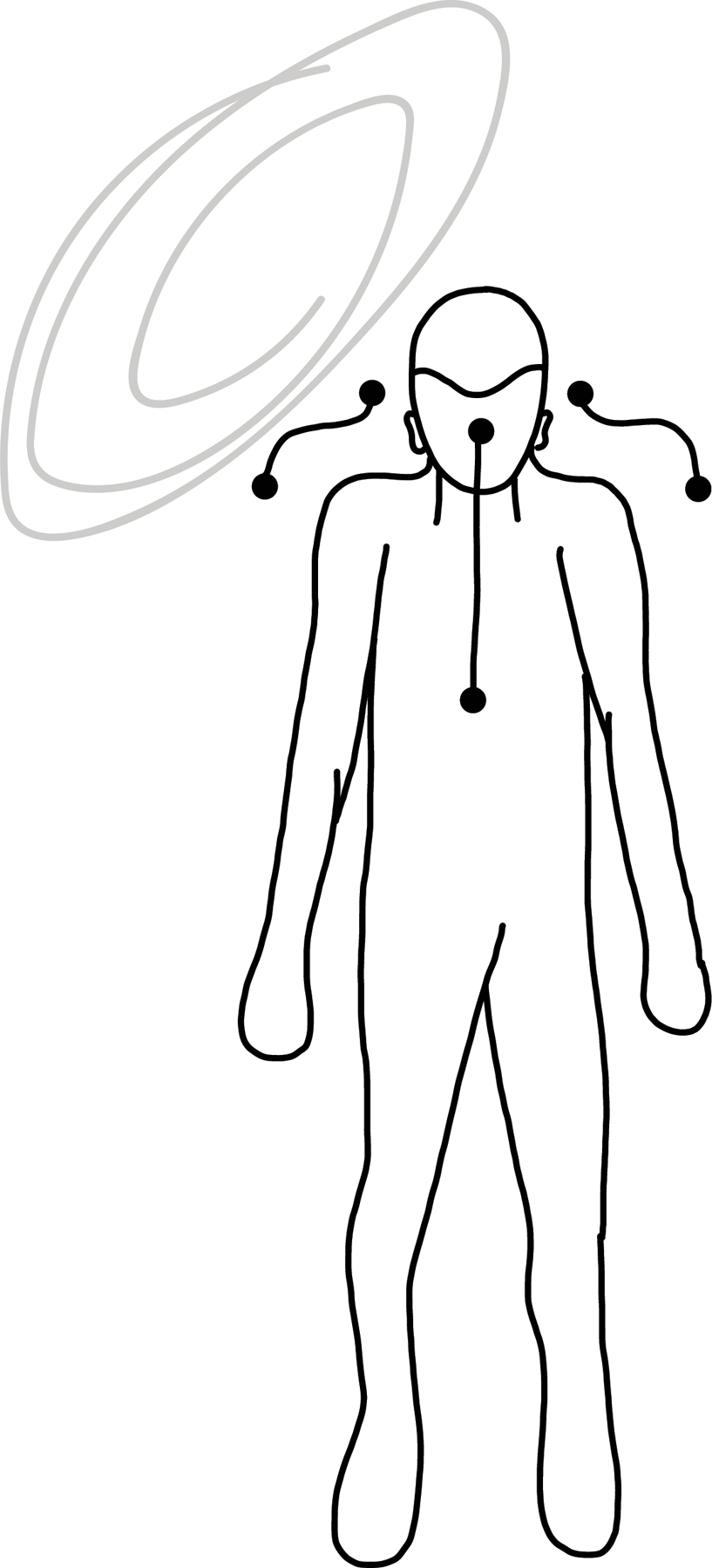

Archetype 1: Mopey

The Mopey person typically moves with low energy and appears structurally as though their body is being pulled to the ground. This position is typically associated with feeling sad, disconnected, tired, or dare I say depressed. Depression has proliferated to become the number one leading cause of disability worldwide. This frightening trend is happening in tandem with our collapsed postural tendencies, as we become more and more pulled-down to stare at devices and spend hours sitting in the same chronically collapsed positions.

Is there a postural connection to this mental health epidemic? I’m personally not attached to either a bottom-up (body affects the mind) or top-down (mind affects the body) perspective on the topic, as it seems apparent each side reciprocally interacts with the other. Movement and postural patterns are keys to mental and emotional well-being (and vice versa)—it’s wise to pay attention to all the factors at play for optimal development.

Structurally speaking, this state can be broken down anatomically to medial rotation of the shoulders, hyperkyphosis of the thoracic spine (where the spine curves forward, leading to a rounding of the upper back), forward head posture manifesting as a “righting reflex” to counter the hunched-over spine, pelvis tucking under like a dog who knows he did something wrong, knees buckling inward (valgus), feet collapsing inward (pronation), and the facial muscles lowering the corners of the mouth while raising the inner portion of the eyebrows. As a result, the Mopey person looks and feels a bit flat, as though the world is literally pulling them down.

MOVEMENT TIP: Doorway Stretch

Start by standing in a tall, proud, and upright position beside a doorway. Guide your breath into the side of your lower ribs and belly to feel the diaphragm engaging to move your breath and calm your nervous system. Imagine you’re attempting to grow your arms down to the ground so your shoulders lengthen away from your ears, and then begin raising one arm up toward the edge of the doorway, while maintaining the length you just created in your neck and shoulders. Grab the edge of the doorway with your raised hand and slowly rotate your body and head away from the outstretched hand, creating a stretch through the shoulder and neck. (Visit TheAlignBook.com for a detailed video guide to this and other movements.)

If you’re feeling down, start looking for movements that will focus on opening, straightening, and awakening your body. Consider some sweaty dance classes with upbeat music, aerobic exercise, hot yoga to loosen up tight muscles, or resetting the system with a plunge in an icy lake (or cold shower), summiting a mountain (or a local hill), or restructuring and strengthening your body with some weight lifting (kettlebell swings, squats, and dead lifts, etc.) Think about taking up more space with your body instead of shrinking inward, as this, too, has been shown to induce a greater sense of confidence.

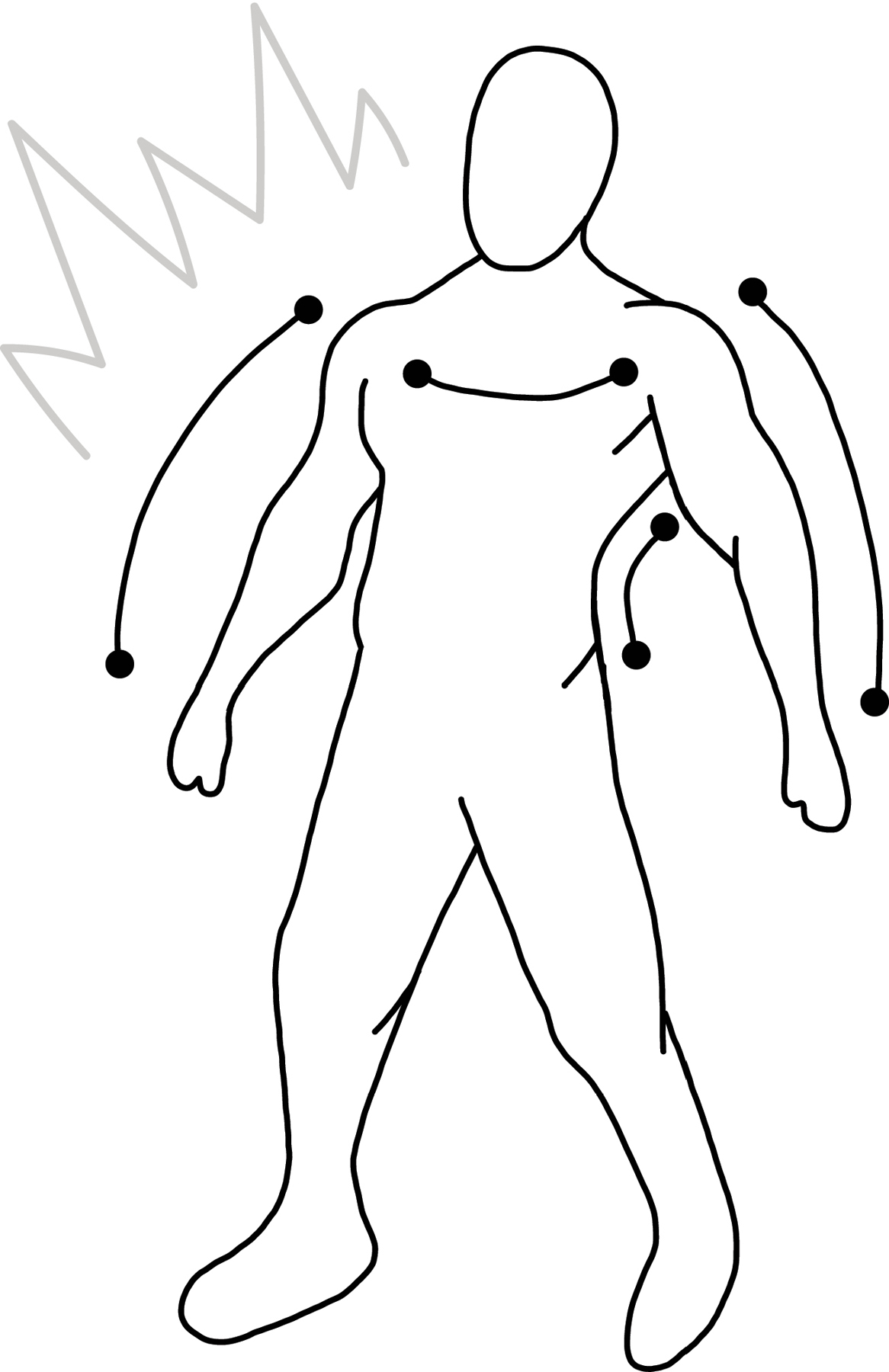

Archetype 2: Anxious

This person can be spotted with their shoulders up, as if attempting to have an affair with their ears. Their eyes are peeled wide open anticipating impact, their mouth may be dry, and the breath is short and predominantly in the upper chest as a response to their nervous system bracing to fight, flight, or freeze to protect against a potential predator (modern “predators” include bills, deadlines at work, stressful relationships, etc.). Issues they might deal with include high anxiety driving their blood pressure up, chronically elevated cortisol, and digestive issues.

The Anxious archetype tends to be more high-strung, preferring to keep moving at all times, and will have tightly wound muscles to match. Their neck and shoulders are chronically carrying excess tension and their breath is short, mostly coming from the chest and neck muscles. The pace of walking and talking is fast and tends to make other people feel a bit on edge because of it.

MOVEMENT TIP: Gut Massage

Your guts are considered to be your “second brain”: If they’re tense, that sensation will ripple through your whole nervous system, leaving you feeling the same. You can use a resistance band (I recommend the Align Band because it includes a door anchor to adjust the height of the hanging band) to lightly massage your abdomen while intentionally breathing into the areas of tension by placing the door anchor at chest height and wrapping it around your abdomen. Step forward to create tension in the band and roll your spine downward so the band creates a subtle “flossing” effect on your guts. Try breathing out a few seconds longer than you breathe in, and explore making an auditory uhhh sound as you exhale to help relax the tense tissues. (You can jump ahead to Chapter 16 for more on the therapeutic effects of sound.)

Keys for unwinding the tension may include massage therapy, organic essential oils (especially lavender, which has been shown to have a calming effect), time in nature, and taking fun movement classes of any kind. Steer clear of overly caffeinated beverages and high amounts of sugar. Instead drink warm, calming teas and pop a magnesium supplement to relax before bed.

Archetype 3: Swole

This pattern is near and dear to my heart because it’s exactly where I came from, as you read in the introduction. These people (usually male) feel the need to present themselves as being strong and dominant so other people know they’re in control. Think of a gorilla pounding its chest to let the other beta males know he’s the top sexual prospect. The interesting part about going out of your way to signal to other people how strong you are is that it usually stems from a place of insecurity. If you truly feel strong, powerful, and in control of your life, there’s not much reason to search for validation by beating your chest about it.

Anatomically, this pattern appears to be pretty balanced from chest to head, with the shoulders rolled back, neck long for the head to raise higher, and palms slightly front facing (supinated) to signal to the world to bring it on. The imbalances in this position are stuffed down into the lower back (where people can’t see the instability the person is experiencing—oh, the metaphors). This causes the ribs to flare open, reducing abdominal integrity, and encourages chest breathing that puts the person in a continual fight-or-flight state. The legs of the Swole person will tend to point a bit outward (externally rotated) and the gait pattern is a combination of a waddle and strut with the chest puffed out—stiff as if a stick has been carefully shoved up their butt (with love, of course).

MOVEMENT TIP: Dynamic Spinal Twists and Hand Slaps

This is a fabulous way to warm up your body and circulate lymphatic fluid that can build up throughout the day. Here’s what you do: Stand up tall and rotate your spine left and right, allowing your hands to swing and slap the opposite shoulders. Work your hands down your body giving each side a healthy splash of slap therapy. This is a powerful tool to loosen yourself up before any athletic event or to just start the day.

I would also recommend spending more time floating and swimming to help loosen up the body and mind. Complement more water time with some partner dance to soften enough to connect with another person in rhythm, and the Swole person will begin feeling even more comfortable in their own skin.

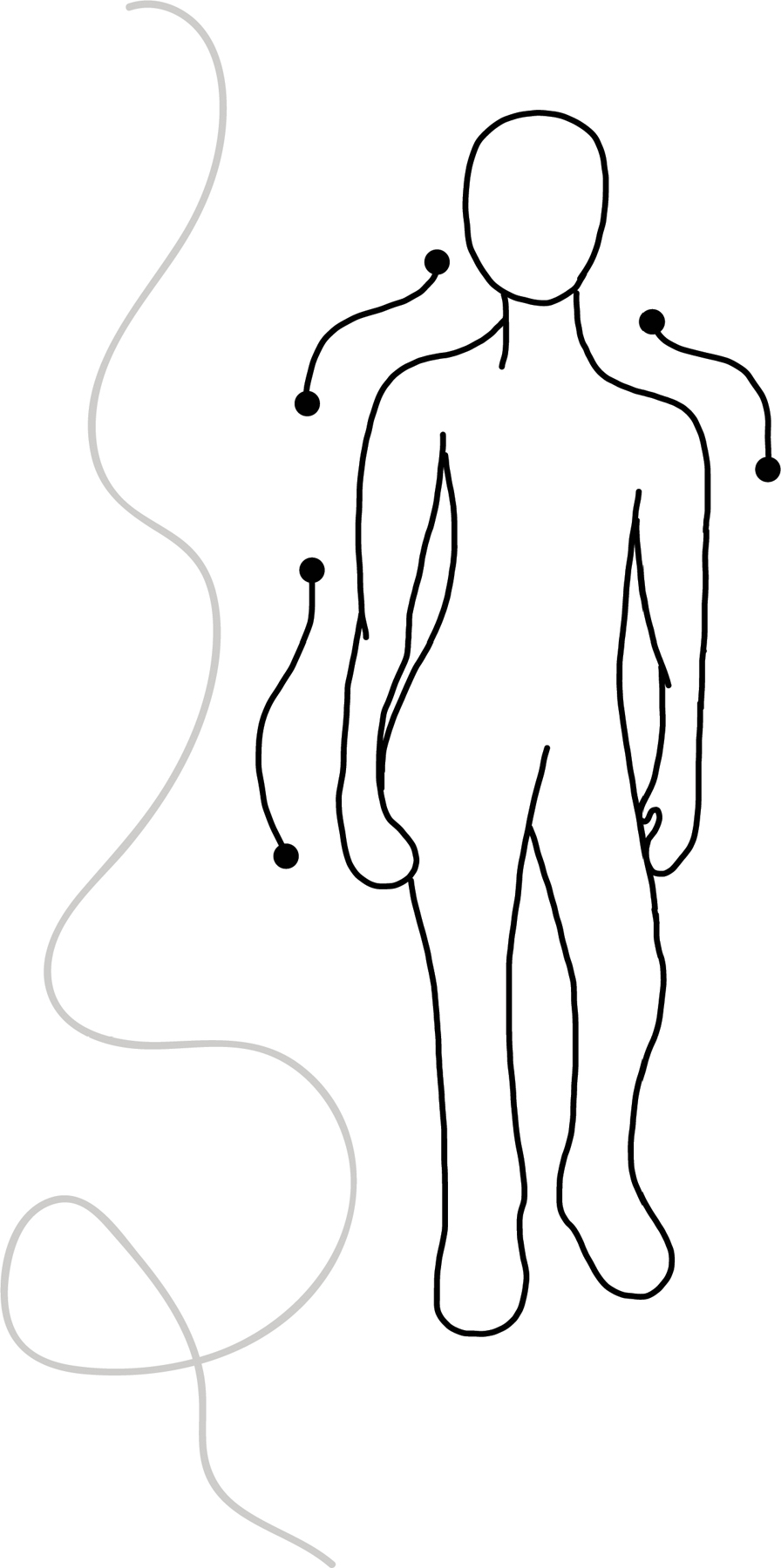

Archetype 4: Bendy

The Bendy person loves all things about mobility but tends to avoid strength development because it’s not as much fun. This type is typically very kind but can sometimes be a bit of a pushover. They will generally go with the flow of things and try not to ruffle too many feathers. Sometimes the Bendy person runs behind on time because they tend to become lost in the moment with what’s in front of them. This person may be a bit spacey but is very creative; they could use a more stable and grounded friend to help organize and actualize their ideas.

Anatomically, the Bendy archetype is, well, bendy. This sounds good, and it can be; the issue comes when a person lacks stability. They tend to lean toward activities that lend themselves to even greater flexibility, such as yoga, and they may also be seen at a local ecstatic dance. Their connective tissue feels very loose to the touch, with a few areas chronically tight to help balance out the excessive mobility elsewhere. They can greatly benefit from weight lifting, manual labor, greater core stability, and a focus on active mobility instead of passive (discussed in Chapter 3).

MOVEMENT TIP: Slowly and Safely Add Weight Lifting to Your Movement Practice

Begin introducing dead lifts and/or back squats to your workout one to two times per week. (Follow the principles outlined in Chapter 6 and/or get a knowledgeable coach to guide you through the lifts; it’s worth it.) Try five sets of five reps to start: The first sets can be light just to practice the motion, and you can gradually move up to about 90 percent of maximum (or to the weight under which you can still maintain perfect form) by the fifth set. Take a three-to-five-minute break between sets in which you work on something else or just take a walk.

If weight lifting isn’t your thing, I recommend manual labor such as carpentry, landscaping, or anything that gets your hands dirty while moving weight. The gratification of stepping back and looking at something you built with your own hands will be helpful.

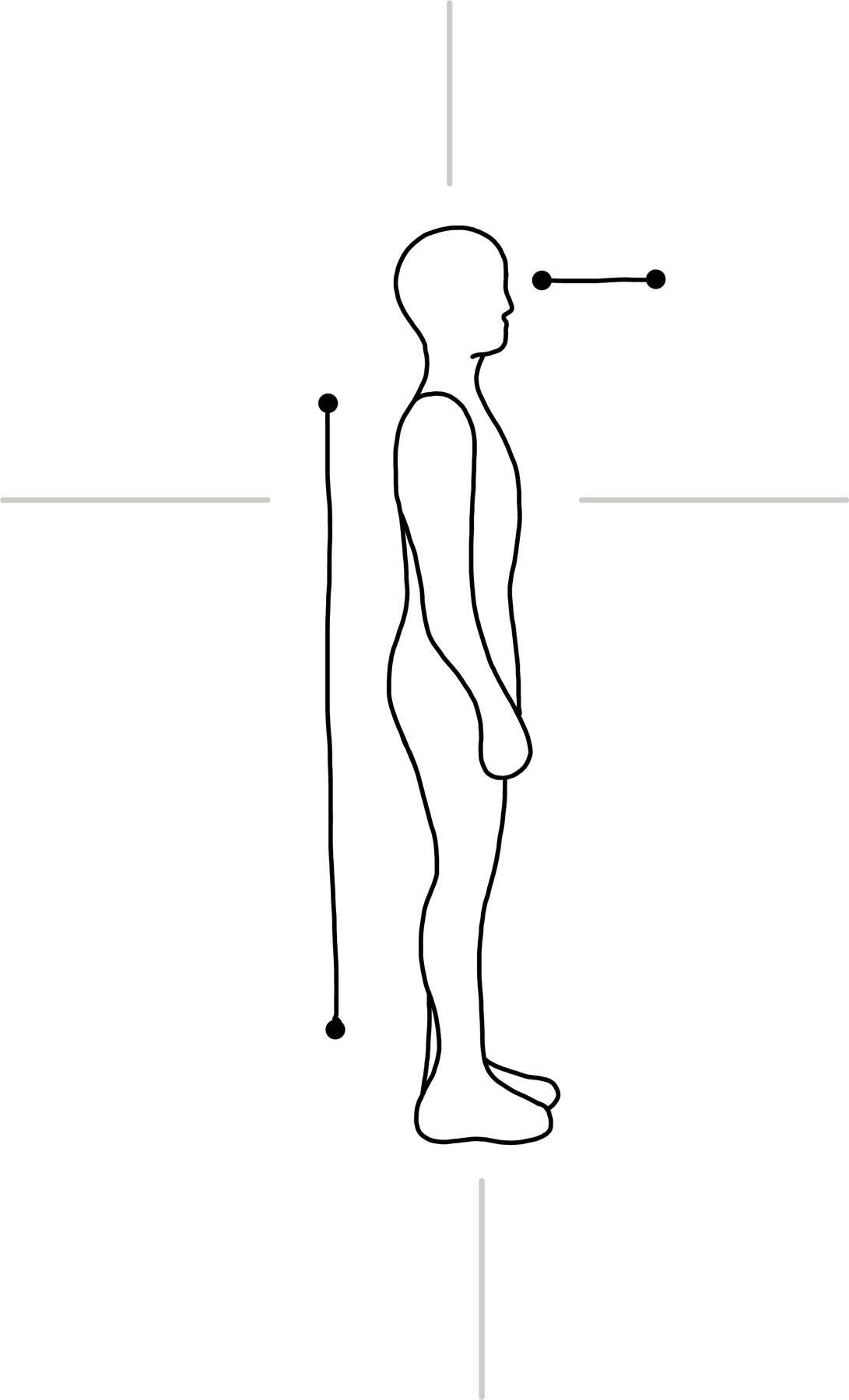

Archetype 5: Aligned

Some say depression is focusing too much on the past and anxiety is focusing too much on the future. There is a middle ground between these two points, and it’s where the Aligned person spends most of their time. You won’t see them jutting their heads forward looking into what’s to come or drooping back wishing the good ol’ days were here again. Instead, they’re thriving in the present moment with exactly what life has dealt them, be it hard or easy. They embody Shakespeare’s idea of there being no such thing as good or bad, and our thoughts making it so, and thus feel a sense of balance no matter what the circumstance.

The Aligned person appears tall and strong no matter their height; you could draw a plumb line down from their ears to their shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles. They’re light on their feet and seem to gain energy as they move instead of wearing down and becoming more tired with every step in a slow journey of attrition. The tonicity of the Aligned person’s muscles is supple at rest, and they can snap into activation at a moment’s notice. They naturally tire as it gets dark and wake up full of energy as the sun rises. They do well in social situations, and people tend be magnetized toward them because they exude a healthy glow. German-American poet Charles Bukowski once said, “The free soul is rare but you know it when you see it—basically you feel good, very good when you are near or with them.” By free soul, I think he was referring to the Aligned person.

Once the mind and body have transitioned into an aligned state and the environment has been formed to match it, the person will naturally become healthier simply by living their lives. This is what Ida Rolf, the founder of Rolfing Structural Integration, meant when she wrote, “This is the gospel of Rolfing: when the body gets working appropriately, the force of gravity can flow through. Then, spontaneously the body heals itself.”

The Aligned person will remain humble and lead others into better alignment via their own positive example. They don’t feel the need to shame or criticize others for living different lifestyles. They monitor and cultivate their thoughts because they realize perception is of greater value than circumstances, and thus this person typically feels balanced and equanimous.

MOVEMENT TIP: Activate Your Senses

The Aligned person likely already naturally does the 5 Daily Movements (floor sitting, nasal breathing, hip hinging, hanging, and walking) with regularity, so I recommend focusing on Part IV: Moving Your Senses to bringing more healthy movement into your life via the power of sight, sound, touch, and mindfulness.

ALIGN YOURSELF

Grab a piece of paper (or feel free to write in the book; I won’t be offended) and label the sensation and characteristics of your major joints and appendages. Write out a couple adjectives for each, starting with your feet, then ankles, knees, hips, spine, shoulders, head, neck, elbows, and hands. This list will contain around twenty words ranging from strong, stable, rough, quiet, clear, rigid, dependable to loose, flexible, open, expansive, loud, unstable, bright, or whatever comes to mind. Now that you have your list, notice whether it’s an accurate description of your personality and sense of the way you feel. See if you align with one postural archetype more than others, and after following along with the 5 Daily Movements for one month, come back and make the list again to see how it changes!

Alignment Assignment

Identify which postural archetype you relate to most, and begin incorporating the Movement Tip associated with the archetype into your life this week. If the movement feels good, keep doing it!

Also, start noticing the way people move and the how it relates to their personalities. For example, a great way to make your airport time more interesting is to actively observe people’s postural patterns and play with creating a story of what they do, hobbies they enjoy, and see if you can relate a postural archetype to them as well. (The story you create may be way off. Just have fun with it.)