Chapter 1

Origins

The earliest use of the term ‘landscape architecture’ in print appears to have been in the title of Gilbert Laing Meason’s On The Landscape Architecture of the Great Painters of Italy in 1828. Meason was a well-connected gentleman-scholar, numbering the best-selling Scottish novelist Sir Walter Scott among his friends, but he had no great following of his own. He used ‘landscape architecture’ to refer to the setting of buildings in the landscape, rather than to the design of the landscape itself. We might have heard no more about it, had not a fellow Scot, John Claudius Loudon (1783–1843), adopted the expression. Loudon was a prolific designer, writer, and editor, and the founder in 1826 of the influential Gardener’s Magazine. Many people read Loudon, including his American counterpart Andrew Jackson Downing, whose A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening went through four editions and sold some 9,000 copies—it included a section headed ‘Landscape or rural architecture’. It seems that this was the route by which the term ‘landscape architecture’ reached the United States and was taken up by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux.

If the expression ‘landscape architecture’ had not even been coined until 1828, where does that leave my assertion in the Preface that the discipline’s origins are as ancient as those of architecture or engineering? Geoffrey and Susan Jellicoe opened their sweeping historical survey of designed landscapes The Landscape of Man (first published in 1975) with illustrations showing the alignment of over a thousand menhirs and dolmens at Carnac in Brittany and the arrangement of 50-ton sarsen stones at Stonehenge in Wiltshire, making it clear that mankind has been purposefully reshaping the land since prehistoric times. Books on garden history, similarly, often begin by imagining that the earliest people put up protective barriers around patches of ground, creating the very first yards or gardens. Landscape architecture, as we shall see, is often concerned with the design of functional and productive landscapes, such as farms, forests, and reservoirs, but it shares an interest in aesthetics, pleasure, and amenity with gardening, which links it, not only to the earliest settlements and cultivations, but also to ancient dreams of paradise.

What constitutes paradise has always depended upon the prevailing conditions. For the ancient Persians, enduring harsh conditions on a dusty and riverless plateau, water was manifestly the source of life. They developed underground canals called quanats to feed their irrigation ditches, and centred their gardens on intersecting canals, producing the classic quartered design—the chanar bagh. The gardens were walled and inward-looking, excluding the desert, and they were filled with all of the things which a desert-living people would enjoy: trees such as date-palms, pomegranates, cherries, and almonds for fruit and shade, cool kiosks, sweet scented shrubs, roses and herbs, pools and bubbling fountains. We derive our word ‘paradise’ from the Old Iranian (Avestan) word for such exceptional gardens, pairi-daeza, which was later shortened to paridiz. It is useful to make a distinction between wilderness or ‘first nature’ and the ‘second nature’ of human settlement and cultivation. The garden historian John Dixon Hunt has suggested the term ‘third nature’ for places such as parks and gardens which have been designed with specific aesthetic intent. Landscape architecture, as we shall see, is involved in second nature as well as third nature. Whether there is anything remaining which can be called ‘first nature’ is a contentious point. Some geologists are already calling our current age the Anthropocene in recognition of the extent of human influence upon the atmosphere and lithosphere. Awareness of the extent of human impact upon the planet should make us all uneasily aware of our collective responsibilities, but it also lends credence to Geoffrey Jellicoe’s assertion in The Landscape of Man that one day ‘landscape design may well be recognised as the most comprehensive of the arts’.

The straight and the curved: formal and informal

Some overview of garden history is needed here because landscape architects are the heirs to centuries of spatial investigation and experimentation conducted by gardeners, and when seeking solutions to new design challenges they often draw upon, or react against, these longstanding traditions. Gardens may be variously classified in terms of their style, but it is useful, from the perspective of design, to locate them on a continuum which has, at one end, formal gardens, which are characterized by geometrical shapes, straight lines, and regularity in plan, and at the other extremity, informal or naturalistic gardens, which are characterized by irregular shapes, curving lines, and much variety. In between these poles are numerous variations and hybrids. The Arts and Crafts style of Edwardian England, for example, was characterized by straight lines, regular geometry, and formality in the plan, but a naturalistic softness in the planting, together with the use of vernacular detailing—employing local materials and traditional construction techniques—in any paving, walls, or other built elements.

History’s earliest gardens were mostly formal. Surveying, measuring, and setting-out are, of course, much easier using straight lines and rectilinear shapes. Ancient cities such as Miletus in what is now Turkey or Alexandra in Egypt were built on the same sort of gridiron plan utilized centuries later in a multitude of American cities. Buildings are easier to build from regularly shaped bricks and stones, while the shortest route between two places is in a straight line. It is easier and more efficient to plough a straight furrow than a curving one, and the same can be said for digging canals and drainage ditches. Though human beings tend to describe a slightly curved course when strolling, ceremonial processions are likely to follow a straight line. The landscape historian Norman Newton attributed the origins of the axis, the most potent of spatial ordering devices, to the route of processions through temple grounds. The principal axis of a formal plan is the imagined line which bisects the front elevation of the building at a right angle, be it a temple, a church, or a great house. The axis connects two points and creates the possibility of bilateral symmetry, where one half of the plan mirrors the other. This was characteristic of Renaissance gardens throughout Europe, such as those of the Villa Lante near Bagnaia in Italy or the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris. This way of organizing garden space reached its zenith in the 17th century in the work of André Le Nôtre, master-gardener to Louis XIV of France. At Versailles, 12 miles outside Paris, Le Nôtre created gardens covering an area twice the size of New York City’s Central Park. The formality of the plan also extended to the treatment of the plants, which were pruned and clipped until they seemed like green masonry. At gargantuan effort and cost, nature was kept under tight control, though even Louis did not get everything his own way: no matter how many engineers he employed or how many soldiers he ordered to build canals and aqueducts, he never succeeded in getting his fountains to run all day. Versailles became the model for many royal gardens throughout Europe, notably at the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, the Peterhof, Peter the Great’s Summer Palace outside St. Petersburg, and Hampton Court near London.

In 18th-century England, garden designers and their patrons turned against French formality in favour of designs that became increasingly irregular and naturalistic as the century progressed. There have been various explanations for this change, including the influence of Dutch design on one hand or reports of Chinese traditions on the other. English landowners certainly wished to distance themselves from French formality, which they associated with an abhorrent absolute monarchy. English patrons were often admirers of the landscape paintings of Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, both of whom had been based in Rome for much of their lives and liked to evoke scenes of Classical Arcadia, taking the landscape of the Roman Campagna as their inspiration. More abstractly, the rise of informality in garden design coincides with a growing interest in empiricism. A devotion to rational geometry gave way to careful observation of the apparent irregularities of the natural world. The serpentine ‘line of beauty’ identified in William Hogarth’s The Analysis of Beauty much resembles the serpentine curves of a Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown lake. In the middle of the century, Brown (1716–83) was ascendant and he remains the best-remembered of his peers, in part because he was so prolific, but also because of his memorable moniker which derives from his habit of telling his patrons, having toured their estates, that he thought he saw ‘capabilities’ in them, his own word for ‘possibilities’ or ‘potential’. Brown’s design formula included the elimination of terraces, balustrades, and all traces of formality; a belt of trees thrown around the park; a river dammed to create a winding lake; and handsome trees dotted through the parkland, either individually or in clumps. Interestingly, Brown did not call himself a landscape gardener. He preferred the terms ‘placemaker’ and ‘improver’, which in many ways are conceptually closer to the role of the modern-day landscape architect than ‘landscape gardener’. Good examples of Brown’s style can be found at Longleat House, Wiltshire, Petworth House in West Sussex, and Temple Newsam park, outside Leeds.

Criticism of Brown began in his own day and intensified after his death. He was criticized in his own time, not for destroying many formal gardens (which he certainly did), but for not going far enough towards nature. Among his detractors were two Hereford squires, Uvedale Price and Richard Payne Knight, both advocates of the new Picturesque style. To count as Picturesque, a view or a design had to be a suitable subject for a painting, but enthusiasts for the new fashion were of the opinion that Brown’s landscapes were too boring to qualify. Knight’s didactic poem The Landscape was directed against Brown, whose interventions, he said, could only create a ‘dull, vapid, smooth, and tranquil scene’. What was required was some roughness, shagginess, and variety. This is an argument mirrored in today’s opposition between manicured lawns and wildflower meadows. In the United States, where smooth trimmed lawns have been the orthodox treatment for the front yard, often regulated by city ordinances, growing anything other than a well-tended monoculture of grass in front of the house can be controversial.

Humphry Repton (1752–1818), Brown’s self-declared successor, argued with the Picturesque enthusiasts, but the public, largely under the influence of the schoolmaster-artist William Gilpin (1724–1804), who published a series of tours to places such as the Wye Valley and the English Lake District, acquired a seemingly unquenchable appetite for Picturesque scenery, and this taste still predominates today. The word ‘picturesque’, however, has lost much of its original meaning and would seldom be given a capital letter nowadays. For many people it now means little more than ‘pretty’ or ‘attractive’; it has lost its connection with painting.

Repton, however, has a particular place in the genesis of landscape architecture. He was the first practitioner to describe himself as a ‘landscape gardener’. He had tried his hand at many occupations—journalist, dramatist, artist, and political agent—before he decided to emulate Brown. He had no deep horticultural knowledge, but he hit upon an ingenious way of presenting his proposals to clients in the form of before-and-after watercolour sketches bound between red covers (Figures 2a and b). By folding out flaps clients could see exactly what changes Repton was suggesting for their estates. These inventive Red Books were the precursors of current methods of visualization—which are more likely to use computer models and fly-through graphics than watercolour drawings. In their own ways, both Brown and the advocates of the Picturesque had imposed their visions upon their clients. Repton was more like a modern-day landscape architect. He understood his clients’ needs and listened to what they told him. As a result, he departed from Brown’s formula and reintroduced the terrace, close to the house, as a useful garden feature. ‘I have discovered that utility must often take the lead of beauty’, he wrote, ‘and convenience be preferred to picturesque effect, in the neighbourhood of man’s habitation.’

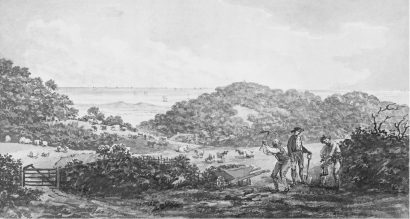

2a. Panoramic ‘before’ view, from Humphry Repton’s Red Book for Antony House, c.1812

2b. Panoramic ‘after’ view, from Humphry Repton’s Red Book for Antony House, c.1812

‘Landscape gardening’ becomes ‘landscape architecture’

Both Loudon and Downing wrote books with the words ‘landscape gardening’ in their titles. In the Anglo-American tradition, landscape gardening is regarded as the precursor of landscape architecture. Where the former was a service to a private client, the latter often aspired to be a public service. This change was facilitated by the campaign for the laying out of public parks, particularly in London’s East End and the cities of Britain’s industrial north. This got going in the 1830s and was part of a movement for social reform which shared the Utilitarian ethos of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham. Loudon was a friend of the philosopher, as were Edward Chadwick, who campaigned for sanitary reform, and Robert Slaney MP, who argued the case for public parks in Parliament. Utilitarian arguments based on the greatest happiness of the greatest number still underpin many plans and policy decisions in the built environment. 19th-century legislation opened the way in Britain for local authorities to make provision for municipal parks and very soon these became matters of civic pride. The Arboretum in Derby in the English Midlands was one of the first, and Loudon was its designer. It was a gift to the city by a philanthropic textile manufacturer and former mayor, and, as its name suggests, it featured a collection of trees and shrubs, labelled for educational purposes. Parks were supposed to improve people, both physically and morally, while the mixing of different classes in public was thought to promote public order in an age when there was a real fear of imminent revolution. Loudon abandoned his Picturesque enthusiasm in favour of a deliberately artificial approach to layout and planting which he named the ‘Gardenesque School of Landscape’. It featured geometric planting beds and exotic plants raised in glasshouses and then planted out. The Gardenesque would soon become the approved style for Victorian parks, offering copious opportunities for the display of horticultural excellence. Loudon’s great contemporary was Joseph Paxton (1803–65), a polymath who rose from being a lowly gardener at the Royal Horticultural Society’s gardens at Chiswick House, London, to becoming the celebrated designer of the Crystal Palace at the Great Exhibition of 1851. He undertook the design of many public parks, but one in particular, Birkenhead Park on Merseyside, was pivotal because Olmsted saw it on his visit to Britain in 1850 and it inspired his design for Central Park. If it were not anachronistic, there would be no great difficulty in calling designers such as Loudon and Paxton ‘landscape architects’, but the term had not been coined in their time.

Meanwhile the job title ‘landscape gardener’ has not faded away, though it is probably more fashionable and lucrative nowadays to describe oneself as a ‘garden designer’. Landscape architecture, as I will show, is by far the broader field, though garden designers, like celebrity chefs, may be better known to the public. The garden now stands in relation to the landscape architect as the private house does to the architect. Just as architects sometimes design private houses, so do landscape architects at times design private gardens—and exhibits at the Chelsea Garden Show—but their bread-and-butter work, particularly in larger offices, is in bigger projects and, as we shall see, many of these are tied, in one way or another, to development. As a profession, landscape architecture only became officially constituted in 1899 when the American Society of Landscape Architects was formed at a meeting in New York. Interestingly they excluded contractors, builders, and nursery-men from their ranks; they did allow in Beatrix Farrand, who designed the celebrated gardens at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC, but she persevered in calling herself a ‘landscape gardener’ to the end of her distinguished career. In Britain, the Institute of Landscape Architects (now the Landscape Institute) was not formed until 1929, 71 years after Olmsted and Vaux’s competition entry had introduced the title.

Elsewhere

The foundational narrative of landscape architecture is certainly a transatlantic affair, and Olmsted’s trip to Birkenhead is often celebrated as the moment of inception. But similar histories can be traced in other countries: a few examples from Europe will reveal the way in which landscape architecture has emerged from earlier traditions of garden and park design, though they will also demonstrate the way that different histories and cultural characteristics have shaped the developing character of the discipline in each nation. In France, where the English style of gardening had been widely adopted in the 18th and 19th centuries, the engineer Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand (1817–91), supported by the horticulturist Jean-Pierre Barillet-Deschamps, constructed a number of public parks in connection with Baron Haussman’s remodelling of Paris. The most striking of these was the Parc Buttes-Chaumont in the north-east of the city, which includes the site of a former limestone quarry whose towering ivy-clad cliffs are topped by a replica of the Roman Temple of Vesta. The French word for ‘landscape architect’ is paysagiste (a very approximate translation would be, ‘countryside-ist’), but the profession was only officially recognized after the Second World War, when the first training courses were established at the horticultural school at Versailles. In the latter decades of the 20th century, re-emergent French traditions of formality, given new life by a chaotic post-modern collaging of ideas, became very influential, as they offered a bracing alternative to tired picturesque scene-making.

In Germany, the most significant figure in the transition from landscape gardening to landscape architecture was Peter Joseph Lenné (1789–1866), gardener to the king of Prussia. In addition to his royal commissions, he laid out some of Germany’s earliest public parks, including the Friedrich-Wilhelm Park in Magdeburg, the Lennépark in Frankfurt (Oder), and the Tiergarten and Volkspark Friedrichshain in Berlin. It was not until 1913 that the Bund Deutscher Gartenarchitekten (Association of German Garden Architects) was founded in Frankfurt am Main, only changing its name to the Bund Deutscher Landschaftsarchitekten (Association of German Landscape Architects) in 1972. The design of communal green open space received attention during the Weimar Republic, but the development of landscape architecture was compromised by the involvement of prominent practitioners with National Socialism. During this period, landscape architects not only worked on planting alongside the newly built motorways, but also, notoriously, on the ‘Germanization’ of rural landscapes in the conquered east. After the Second World War, landscape architecture was quickly re-organized, at least in the west, and practitioners played a significant role in the reconstruction of the war-damaged country. A series of biennial Bundesgartenschauen (Federal Garden Shows), the first of which was held in Hanover in 1951, demonstrated the way in which landscape architecture could transform derelict and war-damaged sites into permanent parkland.

The Dutch park designer Jan David Zocher Jr (1791–1870) was influenced by Brown and Repton, and his Vondelpark in Amsterdam, first opened in 1865, is a romantic, naturalistic park in the English manner. However, the Netherlands also has a history of winning land from the sea and, in the 20th century, comprehensive landscape planning was required to create completely new settlements and landscapes on the polders. The botanist Jacobus Pieter Thijsse (1865–1945), often regarded as the father of the Dutch ecological movement, contributed an internationally influential idea: he suggested that every town or district should have an ‘instructive garden’, where people could learn about the nature on their doorsteps. Thijsse was concerned about the loss of species in the countryside, through such practices as the draining of swamps and the forestation of heathland. The Netherlands is highly urbanized and the countryside is very obviously a human creation, yet there is a yearning for contact with nature. Perhaps as a result, the country produces some of the most interesting new ideas in landscape architecture and urbanism. The title of ‘landscape architect’ has been legally protected there since 1987.

Landscape architecture is now a global discipline, but in many countries it is still in its infancy. Over 70 national associations are affiliated to the International Federation of Landscape Architects, a list that begins alphabetically with Argentina and Australia and ends with Uruguay and Venezuela. The list includes countries as populous as the United States, China, and India and as small as Latvia and Luxembourg. The number of practitioners varies widely too. The Canadian Society of Landscape Architects has over 1,800 members, the Fédération Française du Paysage has over 500 members (but only represents one-third of practitioners), and the Bund Deutscher Landschaftsarchitekten has about 800 members. The Landscape Institute (UK) has over 6,200 members, while the Irish Landscape Institute, only founded in 1992, has 160. By far the largest association is the American Society of Landscape Architects with around 15,500 members. Although there are efforts to standardize education, qualifications, and the requirements for registration, these still vary significantly from country to country, depending upon local institutional structures and laws. Even in the matter of education there is considerable diversity. In some countries, landscape architecture is taught in association with horticulture, agriculture, or gardening. In others, it is the bedfellow of architecture, planning, and urban design. Elsewhere, it may be found in a school of forestry or environmental sciences. While the similarities between the landscape architecture programmes in these different sorts of institution will greatly outweigh the differences, there is no doubt that each will have its distinctive emphasis or flavour.

After reading this potted history, I hope you will have gained some sense of the scope of landscape architecture, but you might now be wondering if the discipline has any definable core. The next chapter will consider the range of activities that come under the general umbrella of landscape architecture and look at various attempts to define the essence of the discipline.