Chapter 3

Modernism

By the time of the 1899 meeting in New York which formalized the landscape architecture profession, a rejection of tradition was sweeping through the entire world of the arts. ‘Modernism’ meant different things to different disciplines, though a pervasive concern was the search for forms of expression relevant to the new social conditions ushered in by industrialization and technological advancement. Modernist thinking in fine art (particularly painting) and in architecture had very different trajectories, but both had a powerful influence upon the nascent discipline of landscape architecture.

The influence of Modern Art

Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe (1900–96), doyen of 20th-century British landscape architects, theorized that landscape design bore a specific relation to the visual arts, particularly painting. A landscape design, he argued, takes a long time to create, for even if the design phase can be done quickly, the construction, which might involve moving great quantities of earth, puddling the clay linings of large lakes, or planting hundreds of trees, is likely to be time-consuming and generally far beyond the powers of any individual working alone. Even when the landform has been created and the planting has gone in, it can take many seasons of growth before the landscape begins to resemble its intended form. These constraints make experimentation difficult. The painter, on the other hand, is in a relatively enviable situation. The material requirements are fewer: a studio, an easel, some canvasses, and some paint. Painters, Jellicoe argued, are thus able to serve as aesthetic pathfinders, while the best a landscape architect can do is to keep up with them. In the 18th century the designers of landscapes had paid close attention to works of art, drawing their ideas from paintings by such luminaries as Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), Claude Lorrain (c.1604–82), and Salvator Rosa (1615–73). However, in the 19th century, he claimed, things had gone seriously wrong. The connection with painting had been severed by an excess of enthusiasm for horticulture, boosted by the stream of new species and varieties sent back to Britain by adventurous plant-hunters, and by technological advances like the steam-heated glass-house, which encouraged a competitive attitude towards horticultural display. In the 20th century, however, landscape design rediscovered its association with art—but art, in the meantime, had moved on.

Even in the days when landscape was still a fashionable genre of painting, the art world did not generally set great store by the accurate depiction of topography. As the geographer and art historian Peter Howard has observed, if you are looking for an accurate record of a landscape, you are more likely to find it in the work of a less celebrated artist than a famous one. Indifference to verisimilitude was such that Henry Fuseli in his role as secretary of the Royal Academy would exclude works which were committed to the ‘tame depiction of a given spot’. In any case, the role of recording landscape passed on to photographers who could do it more accurately and quickly. Artists of serious purpose reacted to the arrival of photography by turning to abstraction. As Howard has noted, there are Cubist landscapes, Surrealist landscapes, and Expressionist landscapes, but the places depicted (if this word can even be used) are of much less consequence than the theory and the method being explored. Nevertheless, this was the art—abstract art—which Jellicoe believed could show landscape designers the way forward.

There were indeed landscape designs which drew direct inspiration from abstract painting. The architect Gabriel Guévrékian (c.1900–70) designed a Garden of Water and Light for the Exposition internationale des Arts Décoratifs et industriels modernes, in 1925, now remembered as a showcase for Art Deco, and this persuaded Charles de Noailles to commission a triangular abstract garden for his villa at Hyères. Art Deco was influenced by Cubism and by a fascination with technology, but its lack of concern for function set it apart from other currents in architectural Modernism. Guévrékian’s, angular gardens with their use of concrete, geometrical patterns and sparse planting must have perplexed many gardeners, but designers saw them as a categorical break with both horticultural and naturalistic traditions. These were, however, gardens to be principally admired for their style, not ‘rooms outside’ to be used. Nevertheless, Fletcher Steele (1885–1971), an American landscape architect, was sufficiently impressed by Guévrékian’s work to write an article with the title ‘New Pioneering in Garden Design’, a Modernist call to arms which initially went unheeded by his peers. Steele began to experiment with Modern ideas in his own design practice, hitherto based upon Italianate formality or the English Landscape style. At Naumkeag, Stockbridge, Massachusetts (1925–38) he took a Renaissance idea, a series of flights of steps rising through woodland, and produced a simplified and much photographed Modernist version, the Blue Stairs, with elegantly sweeping white metal handrails.

Another practitioner influenced by the trend towards abstraction was the Brazilian polymath Roberto Burle Marx (1909–94), a painter, sculptor, jewellery designer, and creator of theatrical sets as well as a botanist, plantsman, and landscape architect. He thought of himself primarily as a painter and his colourful canvasses resemble those of Arp and Miró. Their biomorphic shapes and brilliant colours are also found in his planting plans. By using single-variety blocks he could metaphorically paint landscapes with foliage, as he demonstrated in his celebrated garden for the Monteiro family on their estate near Petrópolis (1946). Some of his work is highly patterned, such as the pavement he designed for the three-mile long promenade of Copacabana Beach in his native Rio de Janeiro (1970). In addition to an impressive catalogue of private commissions, he worked on several notable public projects, including a roof garden for Oscar Niemeyer’s Ministry of Education (1937–45) in Rio de Janeiro, and the planning of Brasilia (1956–60) with the architect Lucio Costa.

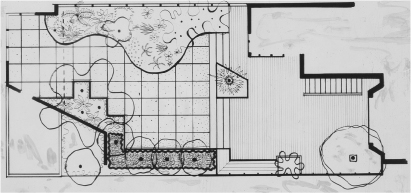

Another important transitional figure was Thomas Church (1902–78) who trained at Berkeley and Harvard, then travelled on a scholarship to Spain and Italy where he realized how similar the climate in California was to that of the Mediterranean and how conducive it could be for outdoor living (Figure 4). During the Depression he opened a small office in San Francisco and gradually built a career designing gardens for affluent middle-class clients rather than the ostentatiously rich. Fletcher Steele’s embrace of Modernism made it easier for Church to throw off the yoke of symmetry. His relaxing gardens with their timber decking and free-form pools became a recognizable component of the West Coast lifestyle, and his way of designing soon became known, inevitably, as the Californian Style. He promoted it through articles in lifestyle magazines, the most influential of which was Sunset, a publication aimed at those settling in California from the East. Church was influenced by abstract art: like Burle Marx, he seems to borrow shapes from Arp and a characteristic ploy was to play off piano curves against grids of paving or zigzagging timber benches. Though Church was influenced by Cubism and Surrealism, it was his meeting with the Modernist architect Alvar Aalto in Finland in 1937 which drove the development of his mature style. Respecting the climate, his gardens made little use of lawn which in the West Coast climate would need constant irrigation. Instead Church used paving, gravel, sand, redwood decking, and drought-tolerant groundcover planting (Figure 5). He designed some 2,000 gardens but his masterpiece is generally thought to be the garden of the Donnell Residence, Sonoma County, California (designed with Lawrence Halprin, 1954) where many of these elements were brought together in harmonious perfection. Church’s decision to build the extensive decking around the existing live oaks on the site is also celebrated, while Adeline Kent’s lissom sculpture for the pool became emblematic of the sybaritic Pacific Coast way of life.

4. Plan of Thomas Church’s Kirkham Garden (1948): the garden as an outdoor room for living

5. Thomas Church’s Donnell Garden, Sonoma County, California (designed with Lawrence Halprin, 1954) became emblematic of the West Coast lifestyle

The influence of architectural theory

Some influential landscape architects have also been qualified architects or have worked closely with them. The two disciplines have a long affinity, so developments in architectural theory inevitably impact upon landscape architecture. Modernism in architecture, according to the historian Nikolaus Pevsner, emerged from Art Nouveau’s refusal to be hamstrung by the past, and the English Arts and Crafts Movement’s demand for excellence and integrity in design. When these trends were united with the enormous potential of industrial technology and with new materials like steel and glass, the way was open for a break with all traditions. More radical than its antecedents, architectural Modernism turned against both individual craftsmanship and extraneous decoration in favour of a pure doctrine of functionalism. A few quotations from its prophets and high priests will indicate its tenor. Adolf Loos (1870–1933), for instance, declared that ‘all ornament is excrement’, while Le Corbusier (1887–1966) believed that the house should be ‘a machine for living in’. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969), director of the Bauhaus design school from 1930–3, left us the pithy minimalist dictum that ‘less is more’, as well as the maxim that ‘God is in the details’. Modern architecture, true to the spirit of its age, was to be a stripped-down, functional creation, whose aesthetic interest came not from applied ornament but from its apparent fitness for purpose and honesty in its use of materials. Industrial mass production and prefabrication would make excellent design available to large swathes of humanity, thus Modernism was often coupled to a progressive social vision. Le Corbusier’s career is instructive. There is no doubt that he was one of the century’s creative geniuses, and his smaller projects, such as the Villa Savoye (1928–31) or the chapel at Ronchamp (1950–4), are rightly recognized as 20th-century masterpieces. However, like many self-confident architects who have turned to city planning, his prescriptions for new urban form could have disastrous consequences. He suggested tearing down large portions of central Paris in order to implement the Plan Voisin (1925), replacing the higgledy-piggledy richness of diverse old quarters with an unlovely grid of tower blocks, each identically cruciform in plan, and unrelentingly imposed across the face of the city. Mercifully this was never implemented, but lesser architects and planners picked up on such sanitizing ideas of grand reconstruction with consequences now recognized as dire. The demolition in 1972 of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St Louis, Missouri, built only 16 years earlier on rational Modernist precepts but notorious for its mounting catalogue of social ills, is often said to have been a turning point. It was, claims the architect and critic Charles Jencks, the end of the Modernist dream.

It is not surprising that landscape architects were swept up in the momentum of Modern architecture’s heady charge, even though they struggled to apply the doctrine of functionalism or find uses for concrete, steel, and glass. One of the first to write enthusiastically about Modernism was Christopher Tunnard (1910–79), a Canadian-born designer who settled in England in 1928. His book, Gardens in the Modern Landscape, was the first manifesto for a Modern landscape architecture. Tunnard not only ridiculed Victorian designers for their fussy ornaments and elaborate herbaceous borders, but even turned on the great Corbusier for illustrating so many of his buildings in a pastoral setting. For Tunnard, the landscape had to be designed on the same rational, purposeful principles as the buildings. In addition to admiring Modernist architecture, he was also enthusiastic about traditional Japanese architecture and garden design, which, he thought, came to the beautiful by way of the functional. He designed two notable Modern gardens in England, one for his own house, St Ann’s Hill, Chertsey, Surrey, designed by Raymond McGrath, the other for the home designed by the Russian émigré Serge Chermayeff at Bently Wood, Halland, Sussex (both 1936–7), but he found Britain resistant to the new thinking and so, when invited to teach at Harvard Graduate School of Design by Walter Gropius (1883–1969), founder of the Bauhaus but by this time an émigré, Tunnard left for America. Eventually he taught at Yale University, where his interest shifted from design towards urban planning and historic preservation. Indeed, as early as 1946, he began to repudiate the dogmas of Modernism, warning that ‘There is a dangerous fallacy in thinking that a certain kind of architecture or planning is intrinsically “better” than another.’

The Harvard Rebels

Harvard, where Tunnard initially went to teach, has a close connection with landscape architecture and with the 20th-century shift toward Modernism. The subject had been taught there since 1900 when a course had been established in memory of Charles Eliot, the son of the president of the university. In 1893, Eliot had become a partner in the practice of Olmsted, Olmsted and Eliot. His partners were Frederick Law Olmsted and his nephew and stepson John Charles Olmsted (1852–1920), but the elder Olmsted’s health was soon failing and Eliot found himself leading the firm, which was the officially appointed landscape architect to Boston’s Metropolitan Park Commission. He had a difficult time trying to persuade the commissioners to produce a comprehensive plan for the city’s park system and his mounting frustration might have contributed to his untimely death from meningitis in 1897 at the young age of 37. The programme set up by his father was headed by another Olmsted, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr, son of the designer of Central Park. The links between the university and the emerging discipline could hardly have been stronger, but by mid-century landscape architecture teaching had got into a rut. The emphasis remained upon Olmstedian visions of pastoral landscape, with a general assumption that naturalistic design was inherently superior to anything formal or obviously man-made. However, when Gropius arrived in 1937 and the decision was taken to merge the three departments of Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and City and Regional Planning as the Graduate School of Design, all this was set to change. Landscape architecture and architecture students would collaborate on studio projects and in this way Bauhaus thinking began to infiltrate the landscape architecture curriculum. Tunnard had been brought in expressly for his avant garde ideas and was to be a catalyst for change. Three mature students also took up the Modernist cause. Their names were Garrett Eckbo (1910–2000), Dan Kiley (1912–2004), and James Rose (1913–91). Collectively they are often referred to as the Harvard Rebels.

Rose’s career, principally as a garden designer, has been somewhat overshadowed by those of his illustrious contemporaries, although there is now a study centre located in his former home in Ridgewood, New Jersey. In the 1930s, his articles for the magazine Pencil Points attacking both axial and picturesque approaches to design were provocative and influential. Dan Kiley was so disenchanted with Harvard’s conservative outlook that he left without graduating, but after the War, through his friendship with the architect Eero Saarinen, he was taken on to work on the Palace of Justice at Nuremburg and while in Europe was able to visit many historic formal gardens where he acquired the design vocabulary of the alleé, bosquet, and boulevard. Later he worked with Saarinen on the J. Irwin Miller House in Columbus, Indiana (1957), where he was able to use some of these elements in a Modern idiom. Kiley recognized (as too did Jellicoe) that the Modernist garden and the Classical garden were not, after all, so far apart in spirit and could be successfully fused. Kiley took from Modernism its stripped-down aesthetic with its clean lines and crisp geometries, but he was happy enough to combine it with a Classical symmetry where it seemed appropriate. Thus his design for the Henry Moore Sculpture Garden at the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City (1987–9), with its gentle terraces and clipped hedges pays homage to Le Nôtre as, in its individual way, does his design for the plaza surrounding I. M. Pei’s Allied Bank Tower, Dallas, Texas (1986), which incorporates 263 bubbler fountains and a grid of cypress trees in circular granite planters.

Of the three Rebels, it was Eckbo who pursued the social vision of Modernism with the most vigour. In 1939, he returned to California where he worked initially for the Farm Security Administration, helping to design settlements for migrant workers, refugees from the Dust Bowl of Oklahoma and Arkansas. He was able to bring some of his Bauhaus training to bear on the design of housing that would not only meet basic needs, but also foster a cheerful sense of community. It was a philosophy that would serve him well after the Second World War when there was a great demand for new homes. His desire to create good environments for the working classes is often contrasted with Church’s work for more prosperous clients. Forming a partnership with Robert Royston and Edward Williams in 1945, the firm initially competed for garden work against Church, but Eckbo had a broader vision of what landscape architecture might do and what it could become. The office took on bigger projects, for campuses, parkways, urban squares, and the surroundings of industrial buildings and power stations. Notable projects included Downtown Mall, Fresno (1965), Union Bank Square, Los Angeles (1964–8), and the open spaces at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque (1962–78). Eckbo became chair of the Berkeley Department of Landscape Architecture in 1963 and in 1964 the practice known as EDAW (Eckbo Dean Austin and Williams) was formed, which went on to become one of the most influential landscape and urban design firms the world has ever known. Eckbo was surrounded by good designers who shared his ethos, but he was the one who could best articulate their mission, which he did most effectively in his Design for Living, a book published in 1950 which now has the status of a classic. It was an attempt to meld the highest theory with the most down-to-earth practicalities and to show that aesthetic and social objectives could be combined. He was dismayed by the fragmentation and dysfunctionality he found in the urban environment, but thought it was the role of the planner or designer to work with people’s best cooperative instincts. Lawrence Halprin (1916–2009), who trained at Cornell Agricultural School before going to Harvard in 1940, just missed being a classmate of Rose, Kiley, and Eckbo, but he was much influenced by Gropius, Tunnard, and also Marcel Breuer (1902–81), another former teacher from the Bauhaus who had fled to the United States. After wartime service, Halprin went to San Francisco where he worked for Church. Though he got on well with his employer, he found private garden work restrictive. In his own words, he wanted to break out of the ‘garden box’ and work on ‘broader scale community work’, so after four years he left to set up his own practice. Among his many contributions to the development of the discipline, he is probably best known for his striking urban parks, particularly Lovejoy Plaza (1966) and Ira Keller Park, both in Portland, Oregon, and both abstracting in concrete the sort of mountain scenery in which Halprin loved to walk. Freeway Park, in Seattle, Washington (1970), which bridged the chasm of a freeway cutting, is also celebrated, as is his pioneering work in urban regeneration at Ghirardelli Square, San Francisco. In the 1960s, he helped to plan a new community on the Californian coast known as Sea Ranch which was driven by an ethos of environmental respect and ‘living lightly on the land’. Halprin was an innovator who sought new collaborations and invented new creative methods. With his wife Anna, a dancer and choreographer, he developed a ‘motation’ to record movements through an environment, and made connections between creating a design and writing a score. He sought, in the spirit of the Bauhaus, to bring together collaborative teams combining insights from different disciplines and was an early advocate of involving citizens in the design process.

Modernism elsewhere

The United States was not the only country to produce a group of Modernist rebels. In Denmark, G. N. Brandt (1878–1945) turned against Beaux Art historicism, but was influenced by spatial clarity of English Arts and Crafts gardens. He is particularly remembered for the geometrically ordered Mariebjerg Cemetery he designed at Gentofte (1925–36). Many landscape architects served an apprenticeship in Brandt’s studio, the most illustrious of whom was C. Th. Sørensen (1893–1979), whose most significant contribution to design was to bring elements of the Danish cultural landscape into his architectonic practice, as he did with the use of hedges to form elliptical enclosures, first in his allotment gardens at Naerum (1948) and then in the sculpture garden associated with the Angli IV factory in Herning (1956). As in America, a typical attitude among Danish Modernists was to regard gardens and landscapes as adjuncts to architecture, outdoor rooms which formed part of the overall composition. Modernism was strong in Sweden too, where it was coupled with progressive social ideals. Holger Blom (1906–96) was an urban planner not a landscape architect, but in 1938–71 he was Director of Parks in Stockholm and promoted the enlightened policy that parks should be seen as social necessities—as significant for civilized life as houses with hot and cold running water. They needed to be planned for active use and they needed to permeate the whole of the city. The landscape architect who helped Blom realize this goal was Erik Glemme (1905–59). While America had produced the California School with an emphasis on private gardens, socially democratic Sweden produced the Stockholm School of Park Design, dedicated to public service. The Stockholm School avoided formal and picturesque idioms, but found inspiration in the regional landscape. Though naturalistic in its visual style, it embraced rational planning, functional goals, and modern materials.

Modernism in architecture was iconoclastic, but in seeking to overthrow historical styles and rigid formulas, it ultimately created straightjacket rules of its own. The International Style was promoted in the 1930s as the only style appropriate for the age, and it was one which, as its name implied, could be applied anywhere in the world, regardless of history, culture, or climate. The steel-framed skyscraper with curtain glass walls became the favoured style of international finance, and the business districts of cities as far flung as Bangkok, Toronto, Melbourne, and Singapore came to look like clones of Manhattan. Landscape architecture was saved from this homogeneous fate in part by the 18th-century injunction to ‘consult the genius of the place’, but also by intractable regional variations in climate, soils, and vegetation. Modernism had never truly replaced such staple landscape materials as earth, water, and plants. Many of the best ideas from the Modern period have survived. Care about materials, an emphasis upon space, a rational approach to site planning, an aesthetic delight in efficient and elegant detailing—these are all part of the positive legacy of Modernism. Above all, there remains the notion that landscapes should be functional, something which will be explored further in the next chapter.